Abstract

Background

Biosimilar therapies and their naming conventions are both relatively new to the drug development market and in clinical practice. We studied the use of the four-letter naming convention in practice and the knowledge, perceptions, and preferences of US health care providers.

Methods

A survey was distributed among health care professionals with a history of utilizing biosimilars in clinical practice to measure key knowledge and the presence of discernable naming trends. Differences in responses across pre-hypothesized subgroups were tested for statistical significance.

Results

Of the 506 surveys emailed, 83 (16%) people responded. Overall, there was poor knowledge about the key concepts surrounding biosimilars. For example, only 52% of respondents correctly identified that biosimilars were not the same as the generic drug; however, frequent use correlated with superior knowledge across all groups. In reference to naming preferences, 67% of all respondents indicated that they commonly use the brand name to distinguish biosimilars in clinical practice and a majority of them (85%) indicated that the brand name was easier to remember than the nonproprietary name with the four-letter suffix. An unexpected number of neutral responses was documented. Notably, more than half of respondents (68%) indicated a neutral response when asked if the four-letter suffix promoted medical errors.

Conclusions

There remains a knowledge gap with regard to biosimilars, and lack of consensus on how the naming convention is and should be utilized in clinical practice. The data also suggest that effective biosimilar education could aid in promoting familiarity with the naming convention among health care providers.

Introduction

The Public Health Service Act (PHS Act) and the US FDA define a biosimilar as a biologic product with no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, and potency from the existing FDA reference product [1, 2]. Since 2015, 28 biosimilar products have been approved by the FDA, with 10 biosimilars approved in 2019 alone [3]. In alignment with the goals of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 (BPCI Act), the abbreviated licensure pathway for biosimilars is expected to increase production, popularize use, and cut costs associated with US spending on biologics [1, 2, 4]. The FDA focuses on a safe, reliable, and effective approval pathway, and in January 2017 provided guidance on the nonproprietary naming of biological products [1, 5].

Guidance from the FDA on the naming of biologic products and biosimilars designates “a proper name that is a combination of the core name and a distinguishing suffix that is devoid of meaning and composed of four lowercase letters” such as, core name ‘replicamab’ could be ‘replicamab-cznm’ [1, 5]. This naming convention was deemed necessary for pharmacovigilance and safe use. The naming convention supports the overall aim to prioritize patient safety by improving tracking of dispensed products, minimizing substitution of non-interchangeable products, and aiding in accurate biosimilar identification by health care practitioners and patients [1, 5]. While the US requires different International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for each biosimilar, Europe does not. Some have suggested that suffixes are obsolete and the lack of differentiation on INN level in Europe has not adversely affected pharmacovigilance [6].

Since its institution, there has been ambiguity in how this naming convention has been adopted in clinical practice and how it has impacted the prescription of biosimilar therapies by health care professionals. Given their relative novelty, there has been the potential for a lack of knowledge among health care workers about biosimilars and how they differ from generic drugs [7, 8]. A systematic review of 20 US and European studies on the use and understanding of biosimilars among health care providers reported a limited understanding of the efficacy and safety of biosimilars. Other studies identified comparable findings regarding knowledge gaps, lack of familiarity, and unfavorable perceptions of biosimilars by health care providers [8–14]. This lack of knowledge may potentially contribute to low comfort levels in prescribing biosimilars among health care providers [7] and underlines the need for continued evidence-based information and education about biosimilars [8]. Moreover, this unfamiliarity with biosimilars might be hypothesized to lead to challenges in the incorporation of accurate approaches to pharmacovigilance and use of appropriate naming conventions. It may be worth noting that heath care providers might simply view the brand name as convenient or sufficient, further contributing to challenges in incorporating the four-letter suffix.

Our study aimed to understand how health care professionals use the FDA naming guidance, and the impact of knowledge and experience with biosimilars on the attitude towards this naming convention. We surveyed practitioners and other health care providers to determine their proficiency with biosimilar therapies.

Methods

Survey development

The overall goal of our survey was to explore the knowledge of health care providers about biosimilars, describe their use of biosimilars, and better understand how and if providers utilize the FDA naming convention. Questions were developed and refined through multiple iterations informed by discussion within the team of investigators. A survey was sent by email to the study population, all of whom had been identified as having previously ordered or processed at least one prescription for a biosimilar. One of the survey’s aims was to test the knowledge of key concepts surrounding biosimilar therapies, such as interchangeability and lot-to-lot variability. We also asked providers about the specific factors that might affect their prescription of biosimilars. The full survey can be found in Online Resource 1.

Study population

We queried medical record data from the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP) and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center (CMCVAMC) to identify all infusion orders and prescriptions for originator and biosimilar infliximab, filgrastim, or pegfilgrastim products since the approval of the first biosimilar in 2015 by the FDA. Health care providers who had prescribed at least one of these biosimilars in any class over the 2015–2019 time period were emailed the survey. In addition to using prescription logs to identify our target population, we spoke with individuals from the pharmacy, nursing departments, and apheresis centers to ensure we were able to extend the survey invitation to other important stakeholders. In addition to the initial survey invitation, four reminders were sent at 2-week intervals to encourage providers to respond. The survey was also sent to other health care professionals who were identified by their peers as being involved in the processing, administration, and coding of these therapies through a process investigation. We allowed respondents to categorize themselves into one of two groups: prescribers (physicians and nurse practitioners) and administrators (other clinical staff such as nurses, pharmacists, and medical coders). We also grouped respondents according to whether they reported experience working with biosimilars in their practice. In total, we had four pre-hypothesized subgroups into which respondents self-selected: prescribers, administrators, those who use biosimilars, and those who do not. Each respondent fell into two categories, either a prescriber or an administrator, and someone who used biosimilars or someone who did not. Despite being identified by prescription logs, some providers reported not having worked with biosimilars in the past.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to illustrate responses to survey questions across groups. Differences in responses across pre-hypothesized subgroups were tested for statistical significance with t-tests, rank-sum tests, Chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact tests. Subgroups that were considered likely to affect knowledge or preference were facility, type of respondent (prescriber vs. administrator), and those that reported using biosimilars regularly versus those that did not report regular use.

Results

Description of survey population

In total, 83 individuals (contact rate of 16%) responded to and completed the survey, most of whom were health care providers practicing at the HUP. The highest number of responses were received from members of the Division of Hematology/Oncology, followed by the Division of Rheumatology and Pharmacy Departments (Table 1). Of all respondents, 60% reported prescribing or interacting with biosimilars on a regular basis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Category | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Total respondents | 83 |

| Site | |

| HUP | 50 (60) |

| CMCVAMC | 11 (13) |

| Both | 16 (19) |

| Neither | 6 (7) |

| Departmenta | |

| Rheumatology | 25 (30) |

| Dermatology | 5 (6) |

| Gastroenterology | 17 (20) |

| Hematology/Oncology | 44 (53) |

| Pharmacy | 26 (31) |

| Infusion Center | 16 (12) |

| Medical Coding | 1 (1) |

| Other | 21 (25) |

| Years in practiceb | |

| < 2 | 6 (19) |

| 2–5 | 6 (19) |

| 5–10 | 5 (16) |

| > 10 | 14 (45) |

| Prescribers vs. administrators | |

| Prescribers | 66 (80) |

| Pharmacists | 11 (13) |

| Other (nurses/coders) | 6 (7) |

| Reported working with biosimilars | |

| Yes | 50 (60) |

| No | 33 (40) |

CMCVAMC Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, HUP Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

Respondents were allowed to select multiple department affiliations, if applicable

Percentages in this section represent the total number in each respective category, and not overall

In addition to collecting data about where individuals work, we also asked about factors that influenced individuals’ decisions to prescribe or not prescribe biosimilar therapies compared with their originator products. Among prescribers who did not prescribe biosimilars, the most common reason as to why not was because they were not familiar with them, followed by not using any biologics in practice. The foremost reasons in favor of prescribing biosimilars were requirements set by hospital formulary mandates and patient insurance mandates (Online Resource 1).

Knowledge of biosimilars

Table 2 describes the responses of practitioners and other health care professionals to questions assessing their knowledge of biosimilars. Overall, knowledge about the definition of a biosimilar was poor, with only 52% of respondents having responded correctly that biosimilars were not the same as generic drugs. Moreover, only 31% correctly acknowledged that the amino acid sequence should be identical for a biosimilar therapy and 35% acknowledged correctly that biosimilars are not automatically pharmacy-substitutable with the originator product. Most prescribers and other clinical staff correctly noted that biosimilars are approved by the FDA according to a highly regulated pathway (Table 2). For some questions, the proportion of correct responses by administrators was greater than that by prescribers, including the aforementioned questions about substitutability and whether biosimilars are generics. For both prescribers and administrators, those who reported having worked with biosimilars more often responded correctly to questions. Those who reported having used biosimilars in the past were more likely to correctly identify the regulatory pathway (96% vs. 58%, p < 0.001) and components of molecular structure for biosimilar therapies (44% vs. 12%, p = 0.003).

Table 2.

Biosimilar knowledge in four pre-hypothesized subgroups: prescribers, administrators, those who reported regular use of biosimilars, and those who do not use biosimilars in practice

| Answered correctly [n (%)] | Answered incorrectly | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| K1. A biosimilar that has been approved by a regulatory body through a highly regulated pathway has a similar efficacy and comparable safety and immunogenicity compared with the originator product (True) | |||

| Overall | 67 (81) | 16 | |

| Prescribers | 51 (77) | 15 | 0.17 |

| Administrators | 16 (94) | 1 | |

| Those who use biosimilars | 48 (96) | 2 | <0.001 |

| Those who do not use biosimilars | 19 (58) | 14 | |

| K2. Biosimilars are generics of originator biologic drugs (False) | |||

| Overall | 43 (52) | 40 | |

| Prescribers | 28 (42) | 38 | <0.001 |

| Administrators | 15 (88) | 2 | |

| Those who use biosimilars | 31 (52) | 29 | 0.04 |

| Those who do not use biosimilars | 12 (36) | 21 | |

| K3. A biologic must have the exact amino acid sequence as the originator product (True) | |||

| Overall | 26 (31) | 57 | |

| Prescribers | 21 (32) | 45 | 1 |

| Administrators | 5 (29) | 12 | |

| Those who use biosimilars | 22 (44) | 28 | 0.003 |

| Those who do not use biosimilars | 4 (12) | 29 | |

| K4. Biosimilars are ‘interchangeable’ with the originator product (False) | |||

| Overall | 29 (35) | 54 | |

| Prescribers | 20 (30) | 46 | 0.14 |

| Administrators | 9 (53) | 8 | |

| Those who use biosimilars | 19 (38) | 31 | 0.63 |

| Those who do not use biosimilars | 10 (30) | 23 | |

| K5. There is similar variability between originator product lots as there is a variability between biosimilars and originator products (True) | |||

| Overall | 43 (52) | 40 | |

| Prescribers | 34 (52) | 32 | 1 |

| Administrators | 9 (53) | 8 | |

| Those who use biosimilars | 33 (66) | 17 | 0.003 |

| Those who do not use biosimilars | 10 (30) | 23 | |

Differences in responses between prescribers versus administrators, and those who reported regular use of biosimilars versus those who do not use biosimilars in practice were tested for statistical significance. For the purposes of these questions, ‘Those who use biosimilars’ include both prescribers and administrators. The correct answer is included at the end of the question in parentheses. The total number of correct answers is shown alongside the percentages. Incorrect totals include any marked ‘Unsure’ responses

Use and preference in naming conventions

This section details survey responses pertaining to naming conventions, both in general and in clinical contexts among all respondents and those self-categorized as prescribers or administrators. In clinical practice, more respondents (67%) used the brand name than the nonproprietary name with the four-letter suffix (31%) to identify biosimilars. Most respondents (85%) indicated that the brand name was easier to remember (Fig. 1). Responses were similar between prescribers and administrators (Online Resource 1).

Fig. 1.

Questions related to the general use of biosimilar identifiers in clinical practice. All questions included: ‘To what degree do you agree with the following?’ Questions Q1–Q5 are detailed below: Q1. I regularly distinguish biosimilar therapies on the basis of their four-character suffix in the nonproprietary name. Q2. I rely on the use of the nonproprietary name and four-character suffix to distinguish biosimilars. Q3. I rely on the use of the brand name to distinguish biosimilars. Q4. In practice, I find that the brand name is easier to remember compared with the nonproprietary name with the four-character suffix

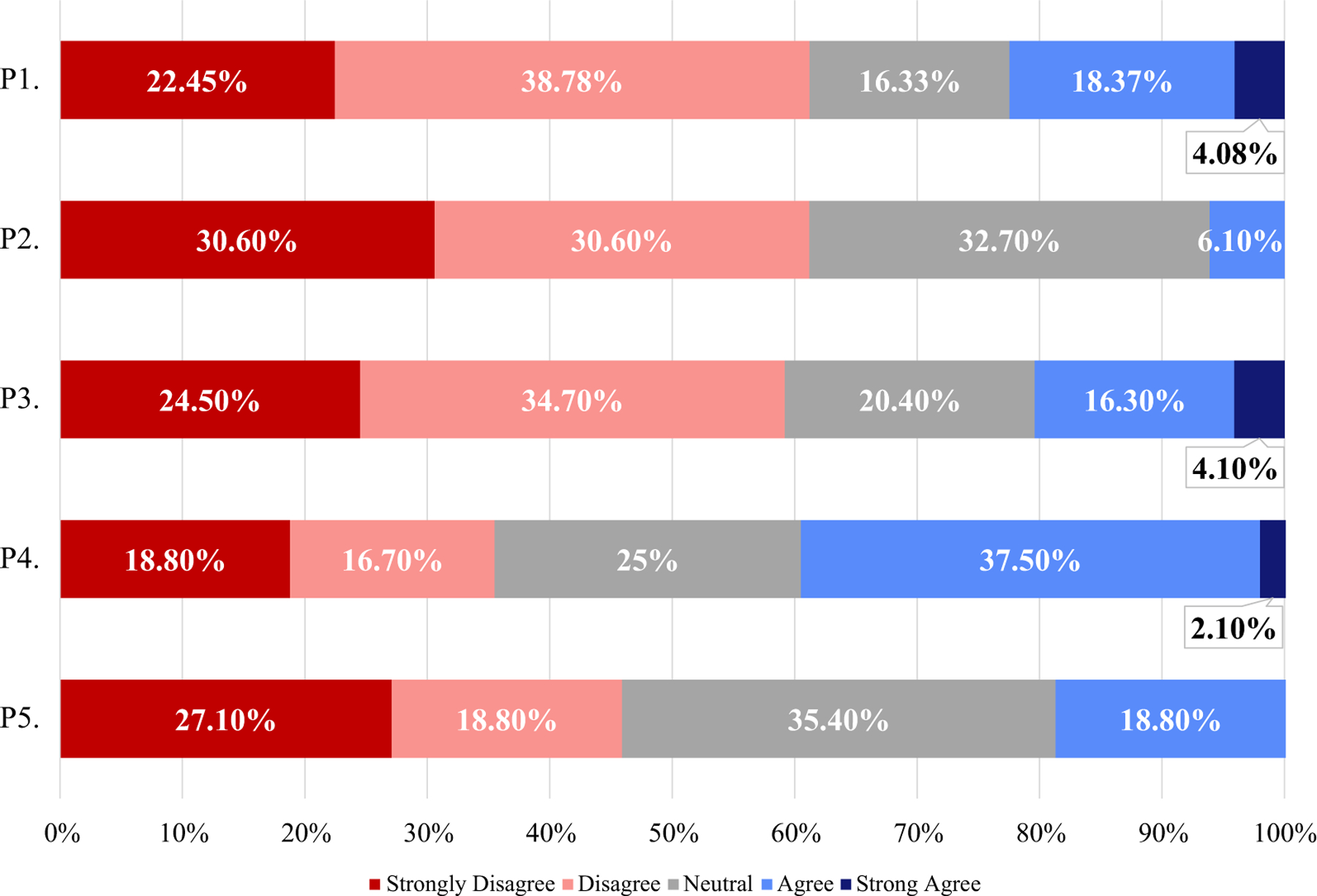

A minority of respondents (6–22%) reported using the four-letter suffix in clinical practice or for more specific activities such as reporting medication errors, searching for biosimilars in large databases, and reporting of adverse events (Fig. 2). A larger proportion (40%) reported using the four-letter suffix to learn about biosimilars in medical literature (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Questions relating to specific circumstances where the four-character suffix is used. All questions included: ‘To what degree do you agree with the following?’ Questions P1–P5 are detailed below: P1. I rely on the four-character suffix in the nonproprietary name to identify the biosimilar product in clinical practice. P2. I rely on the four-character suffix in the nonproprietary name to facilitate the tracing of biosimilars in large databases. P3. I rely on the four-character suffix in the nonproprietary name to ensure the safety of biologic use in practice (e.g. reporting of adverse events). P4. I have used the non-proprietary name with four-character suffixes to learn about biosimilars in the medical literature. P5. The use of the four-character suffix in the nonproprietary name to distinguish biosimilar therapies in practice reduces medication errors in the ordering of biologics

Responses to some questions about naming differed between prescribers and administrators. Administrators were more likely to report using the four-letter suffix to trace biosimilars in large databases (p = 0.03). There were no other differences between prescribers and administrators for the questions in Fig. 2; however, administrators were also less likely to believe (p = 0.03) that the four-letter suffix would influence patients to perceive that there are important differences between biosimilars and their originator products (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Questions regarding naming preferences. All questions included: ‘To what degree do you agree with the following?’ Not all responses add to 100 due to a single instance where a respondent skipped a question. Questions N1–N5 are detailed below: N1. I am less likely to use biosimilars compared with the originator product because the nonproprietary names of biosimilars are different from the originator product. N2. I have experienced that the use of brand names to distinguish biosimilars introduces commercial bias in clinical practice. N3. The four-letter suffix in the non-proprietary name influences patients to think there are important differences between biosimilars and the originator products. N4. The four-letter suffix in the nonproprietary name causes inefficiencies due to inconsistencies with other naming systems in practice. N5. The use of the four-letter suffix in the nonproprietary name to distinguish biosimilar therapies in practice promotes medication errors in the ordering of biologics

For many questions, there was no consensus and neutral responses were very common; for some questions, a neutral response was the most common response (Fig. 3). For example, the majority of responses (68%) were neutral regarding whether use of the four-letter suffix promoted medical errors. High rates of neutral responses can also be observed in Fig. 2.

Discussion

Biosimilar naming conventions are a relatively new concept, developed in response to the introduction of this new type of biopharmaceutical. We found that many health care providers in this largely academic setting remain unfamiliar with specific concepts regarding biosimilars. They reported greater comfort using brand names, rather than the nonproprietary names with the four-letter suffixes, to identify biological products in clinical practice. In addition, a main barrier to prescribing biosimilars was a lack of familiarity with them, indicating that a knowledge gap is still present and partially responsible for the inconsistent use. The abundance of neutral responses, as well as the lack of overall agreement regarding the benefit or disadvantage of using the four-letter suffix in clinical practice, indicates a general ambivalence towards naming conventions for biosimilars that has been proposed by the FDA. These observations are important and should inform future development of naming conventions to facilitate pharmacovigilance and ensure the safe use of biosimilars. Our study is among the first to evaluate how the naming convention is being used in clinical practice.

We found that health care professionals who had prescribed biosimilars used the brand name preferentially to the nonproprietary name with the four-letter suffix. Administrators, in particular, did not rely on the four-letter suffix in clinical care. In addition, most respondents reported that the brand name was easier to remember. Few respondents acknowledged using the four-letter suffix for other areas of practice, including tracing biosimilars in databases and identifying biosimilars in the medical literature, although there were many neutral responses. It is notable that the US differs from many countries in its distinction of biosimilars from the reference product. It has been suggested that distinction of biologics by brand name may make use of the four-letter suffixes obsolete [6]. These data obtained from our study further suggest that there is not a high utilization of the four-letter suffixes, but rather that brand names are frequently used to distinguish biologics in the US. However, the implications of removing the four-letter suffix are not entirely clear given the uncertainty of the availability of brand names in different data sources that may not reliably distinguish the therapies on the basis of brand name. In short, our study did not directly assess whether pharmacovigilance has been enhanced by the naming convention; however, our data do not suggest that prescribers and administrators place a high level of value on it. Should future studies suggest a lack of benefit to pharmacovigilance, a re-evaluation of the benefit of the naming convention may be indicated.

A primary aim pursued by the FDA in developing the naming convention was to ensure safe use of biologics and promote pharmacovigilance. Notably, many in this sample of health care providers did not use the four-letter suffix to ensure safe biologic use (i.e. reducing the incidence of adverse events) or to reduce medication errors. The majority of respondents indicated that the brand name was easier to remember than the nonproprietary name with a four-letter suffix and used it to identify biosimilars. Our study indicates that the four-letter suffix has not yet been widely adapted for use in clinical practice.

Previous studies have shown gaps in biosimilar knowledge and biosimilar prescribing practices [7–11]. A 2016 study collected 1201 survey responses from US physicians across all specialties regarding different aspects of biosimilar knowledge [10]. Notably, when asked to identify a biosimilar as a drug with the same efficacy as the originator or that biosimilars would be “at least as safe as their brand-named counterpart”, only a slight majority of physicians correctly responded (62% and 57%, respectively) [10]. In 2017, knowledge gaps were found even among physicians in the same dermatology specialty, with only a 25% likelihood of prescribing biosimilars to their patients [9]. In particular, one 2019 study highlighted that even physicians who currently prescribe biosimilars anticipated a negative impact on treatment efficacy (57%) and patient safety (53%) [14].

Our study further advances the field by evaluating the influence of knowledge on professionals’ use of the FDA naming convention. Greater knowledge has been correlated with increased use of biosimilars, since time and experience generally lead to a better understanding of them and a higher level of confidence in prescribing them [7, 8, 12, 15, 16]. In our study, prescriber knowledge was generally worse than that of other staff. Our survey results add to prior studies in showing that a lack of knowledge among prescribers remains a barrier that is yet to be overcome, and we propose that this gap may have influenced familiarity with the naming conventions. We continue to see that this lack of knowledge is present even among those who have worked with biosimilars, suggesting that more work is necessary in familiarizing physicians with biosimilars. Our study may support the hypothesis that greater knowledge among health care providers would affect their preference for the use of the four-letter suffix in practice. However, even with greater knowledge of and comfort with the naming convention, health care providers may simply not find the four-letter suffix provides much value. While we specifically hypothesized that some providers might devalue the four-letter suffix because it might introduce doubts to patients about biosimilars, it is reassuring that few respondents agreed that the use of the four-letter suffix influenced patients to believe that there were important differences between biosimilar and originator products. Finally, it may be important to note that knowledge of biosimilars and comfort with the naming convention might also help to increase biosimilar use without requiring institutional or payer-based mandates.

There are several notable limitations of our survey-based study. As with any survey, there is a risk of respondent bias. The low response rate may also influence the generalizability of the data. Those who had prior knowledge and held strong opinions about the naming convention may have been more likely to respond. Thus, we may have overrepresented the prevalence of knowledge about biosimilars and the naming convention in the community. Regardless, familiarity with most specifics about biosimilars was relatively low among respondents. Despite the large size of the hospital settings from which the survey respondents were identified, it is possible that the respondents to this survey are not representative of the region or the nation. Although it is difficult to predict, we would anticipate that a more representative sample would have an even lower level of knowledge about biosimilars. Additionally, the relative novelty of the FDA naming guidance may have contributed to a lack of familiarity and lack of utilization among the respondents. We would anticipate different responses as health care professionals become more familiar with biosimilars and the use of FDA naming conventions increases over time. Although all of our survey respondents had used biosimilars at least once, it is worthwhile to note that 40% of respondents did not indicate that they used them with any consistency.

Conclusions

In summary, our survey found that health care providers have not yet widely incorporated the naming convention for biosimilars, using the nonproprietary name with a four-letter suffix, into their practice. Our study also confirmed that a lack of knowledge about biosimilars persists, which likely contributed to relatively low familiarity of health care professionals with the FDA naming conventions. Future studies might evaluate the effect of educational or policy efforts to influence acceptance of the naming convention and of biosimilars [7, 8, 12, 15, 16]. Additionally, the integration of support structures embedded in clinical systems may facilitate adoption of the FDA naming convention by prescribers with the aim of reducing medication errors and promoting pharmacovigilance.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Knowledge gaps and unfavorable perceptions of biosimilar therapies can lead to lower prescribing efforts by health care professionals.

This study aimed to understand how the US FDA-issued guidance for the four-letter naming convention is being used in clinical practice and to understand the preferences of prescribers and other healthcare providers in the USA.

Health care providers in this study demonstrated a persistent lack of familiarity and knowledge with biosimilars and little consensus on how the four-letter naming convention of biologic products has and should be utilized in clinical care.

Education leading to greater knowledge and experience with biosimilars might impact perceptions and increase use of the naming convention in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

Joshua Baker would like to acknowledge the support of a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development Merit Award (I01 CX001703). The contents of this work do not represent the views of the Department of the Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Funding

Dr. Leonard is partly supported by grants from the United States National Institutes of Health (R01AG060975) and the American Diabetes Association (1-18-ICTS-097). Dr. Baker is supported by a Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development VA Merit Award (I01 CX001703).

Conflicts of interest

Criswell Lavery, Marianna Olave, Vincent Lo Re, and Judy A. Shea declare they have no conflicts of interest. Charles Leonard reports grants from the FDA, during the conduct of this study; grants from the National Institutes of Health and the American Diabetes Association; personal fees from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Research Institute and the University of Florida College of Pharmacy; other fees from Sanofi and Pfizer; and nonfinancial support from John Wiley & Sons, outside the submitted work. Jonathan Kay reports personal fees from AbbVie Inc., Alvotech Swiss AG, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Celltrion, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Mylan Pharma GmbH, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp., Samsung Bioepis Co., Ltd, Sandoz, Inc., and Roche Pharmaceuticals, as well as grants and personal fees from Pfizer, Inc. and UCB, Inc., outside the submitted work. Joshua Baker reports personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s40267-021-00844-z.

Availability of data and material

All data and materials can be requested from the corresponding author upon request (bakerjo@uphs.upenn.edu).

References

- 1.Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) & Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). 2017. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/nonproprietary-naming-biological-products-guidance-industry. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

- 2.H.R. 3590 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Enrolled Bill [Final as Passed Both House and Senate]-ENR) Sec. 7002 approval pathway for biosimilar biological products. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/78946/download. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

- 3.Biosimilar Drug Information. US Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-product-information. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

- 4.Interpretation of the “Deemed to be a License” Provision of the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) & Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). 2021. https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information-biologics/biologics-guidances. Accessed 9 Jul 2020.

- 5.Nonproprietary Naming of Biological Products: Update Guidance for Industry. US Food and Drug Administration Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) & Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). 2019. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/nonproprietary-naming-biological-products-update-guidance-industry. Accessed 19 Oct 2020.

- 6.Kurki P, van Aerts L, Wolff-Holz E, et al. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a European perspective. BioDrugs. 2017;31(2):83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leonard E, Wascovich M, Oskouei S, et al. Factors affecting health care provider knowledge and acceptance of biosimilar medicines: a systematic review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):102–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbier L, Simoens S, Vulto AG, et al. European stakeholder learnings regarding biosimilars: Part I-Improving biosimilar understanding and adoption. BioDrugs. 2020;34(6):783–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsell A, Rengifo-Pardo M, Ehrlich A. A survey assessment of US dermatologists’ perception of biosimilars. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(6):612–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33(12):2160–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manalo IF, Gilbert KE, Wu JJ. The current state of dermatologists’ familiarity and perspectives of biosimilars for the treatment of psoriasis: a global cross-sectional survey. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(4):336–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayanan S, Nag S. Likelihood of use and perception towards biosimilars in rheumatoid arthritis: a global survey of rheumatologists. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(1 Suppl 95):S9–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Overbeeke E, De Beleyr B, de Hoon J, et al. Perception of originator biologics and biosimilars: a survey among belgian rheumatoid arthritis patients and rheumatologists. BioDrugs. 2017;31(5):447–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teeple A, Ellis LA, Huff L, et al. Physician attitudes about non-medical switching to biosimilars: results from an online physician survey in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(4):611–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AMCP Partnership Forum. Biosimilars – ready, set. Launch J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(4):434–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene L, Singh RM, Carden MJ, et al. Strategies for overcoming barriers to adopting biosimilars and achieving goals of the biologics price competition and innovation act: a survey of managed care and specialty pharmacy professionals. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(8):904–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials can be requested from the corresponding author upon request (bakerjo@uphs.upenn.edu).