Abstract

Objective

To determine progress and gaps in global precision health research, examining whether precision health studies integrate multiple types of information for health promotion or restoration.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

Searches in Medline (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and grey literature (Google Scholar) were carried out in June 2020.

Eligibility criteria

Studies should describe original precision health research; involve human participants, datasets or samples; and collect health-related information. Reviews, editorial articles, conference abstracts or posters, dissertations and articles not published in English were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

The following data were extracted in independent duplicate: author details, study objectives, technology developed, study design, health conditions addressed, precision health focus, data collected for personalisation, participant characteristics and sentence defining ‘precision health’. Quantitative and qualitative data were summarised narratively in text and presented in tables and graphs.

Results

After screening 8053 articles, 225 studies were reviewed. Almost half (105/225, 46.7%) of the studies focused on developing an intervention, primarily digital health promotion tools (80/225, 35.6%). Only 28.9% (65/225) of the studies used at least four types of participant data for tailoring, with personalisation usually based on behavioural (108/225, 48%), sociodemographic (100/225, 44.4%) and/or clinical (98/225, 43.6%) information. Participant median age was 48 years old (IQR 28–61), and the top three health conditions addressed were metabolic disorders (35/225, 15.6%), cardiovascular disease (29/225, 12.9%) and cancer (26/225, 11.6%). Only 68% of the studies (153/225) reported participants’ gender, 38.7% (87/225) provided participants’ race/ethnicity, and 20.4% (46/225) included people from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. More than 57% of the articles (130/225) have authors from only one discipline.

Conclusions

Although there is a growing number of precision health studies that test or develop interventions, there is a significant gap in the integration of multiple data types, systematic intervention assessment using randomised controlled trials and reporting of participant gender and ethnicity. Greater interdisciplinary collaboration is needed to gather multiple data types; collectively analyse big and complex data; and provide interventions that restore, maintain and/or promote good health for all, from birth to old age.

Keywords: public health, general medicine (see internal medicine), nutrition & dietetics, occupational & industrial medicine, preventive medicine, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First comprehensive overview of precision health research, employing a broad search strategy to capture relevant precision health studies and systematically determining the extent to which the included studies fulfil aspirations for the field.

Each step in the scoping review was conducted in independent duplicate, facilitating rigorous screening and data extraction.

Dissertations, unpublished clinical trials, patents and articles not written in English were excluded, potentially missing preliminary findings and emerging advances.

The search strategy might not have fully captured research in subdisciplines such as precision public health and precision mental health.

Stakeholder evaluation of the review’s findings was not conducted, which could have provided insights on precision health researchers’ perceptions on the reported progress and research gaps.

Introduction

Precision health is a nascent field that seeks to maximise population health and well-being while minimising premature disability and death through the continuous monitoring of key health data, generation of actionable health discoveries1 and recommendation of personalised interventions.1 2 It is derived from precision medicine, which similarly considers individual variation in biological, environmental and behavioural data to inform the diagnosis and treatment of disease.3 Distinct from precision medicine, precision health takes a lifespan perspective in health monitoring, identifying actionable risks and intervening early. Interventions may include continuous health screening, early diagnostic testing and support to improve behaviour and lifestyle. Interventions are also personalised, with each piece of information considered in context, different to the typical ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach of modern medicine.

While precision health is in its infancy, early work has produced promising findings. In the Integrated Personal Omics Profiling (iPOP) study,4 longitudinal health monitoring was undertaken using a comprehensive array of multiomic (eg, genome, transcriptome and microbiome), lifestyle and clinical measures to identify actionable health discoveries for people with type 2 diabetes. Integration of these measures led to accurate disease diagnosis, which can enable personalised treatment plans. Majority of participants took action as a result of study participation, modifying their lifestyle and discussing findings with medical practitioners. The iPoP study highlights the potential value of precision health, using comprehensive, highly specific and integrated data for health management. Other promising signs for precision health include establishment of substantive research groups and collaborative efforts, formative work to develop technologies and algorithms, and proof-of-concept studies with limited populations.1 5–7 However, there is still limited knowledge on the characteristics of studies categorised as precision health, and the extent to which they fulfil the vision of a precision healthcare future.

The early stages of precision health offer a unique opportunity to determine key research agendas, identify promising research trajectories, and highlight knowledge gaps, which can then help shape future directions for research and implementation. As a first step towards achieving these goals, this scoping review maps precision health research in the past 10 years and provides an overview of research progress, trends and gaps.

Methods

This scoping review is based on a published protocol,8 developed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-Scoping Review Extension9 (online supplemental appendix 1) and Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines.10

bmjopen-2021-056938supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Information sources

Searches were undertaken in five electronic bibliographic databases including Medline, PsycINFO (through OVID), Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and grey literature databases including Google Scholar on 30 June 2020. Grey literature searches were considered important in the context of this review due to the likelihood of innovations published outside conventional academic databases. Hand searching of the reference lists of reviews or discussion papers and the publication lists of precision health research groups on their websites was also undertaken.

Search strategy

Preliminary searches established the final search terms and eligibility criteria, which were designed to capture a range of precision health research. Search terms included ‘precision’ or its synonyms ‘personalised’, ‘individualised’, ‘stratified’ or ‘tailored’, as identified by Ali-Khan et al.11 and with ‘health’ immediately adjacent (eg, ‘precision health’). The search strings used for Medline (OVID), PsycINFO (OVID), Embase, Scopus, Web of Science and grey literature (Google Scholar) are presented in online supplemental appendix 2.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible articles included those published between 1 January 2010 and 30 June 2020, with the term ‘precision health’ being established as independent from ‘precision medicine’ after 2010. Articles were included if they described original research or the protocol for original research, involved human participants or samples including historical datasets and collected health-related data. Articles were required to make a reference to ‘precision health’ or its derivatives in the title and/or abstract and the introduction, methods and/or results. Reviews, editorial articles, conference abstracts or posters and dissertations were excluded, along with articles not published in English and those where the full-text article could not be retrieved using resources from three different institutions. No limitations were placed on the study population, context or setting.

Screening

All stages of the screening process were conducted in Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation), an online tool for systematic reviews. Duplicates were removed by Covidence, with the authors manually checking for missed duplicates. Title, abstract and full-text screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria were performed independently in duplicate by JNV, JCR, SE, CM, HS and SG. Discrepancies at each screening stage were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

The Covidence extraction form was modified by all team members using an iterative process. Data extraction was conducted independently in duplicate using Covidence. A third, independent reviewer undertook consensus on the extracted data. Data extracted included funding sources, number of authors, conflicts of interest, the country of author affiliations, author disciplinary association, study purpose, technology being developed or application of the findings, study design and setting, sample size, focal health condition being addressed, precision health focus,1 the type of data collected for the purpose of personalisation/tailoring, and participant characteristics (ie, age, sex, health status, ethnicity and socioeconomic status). The sentence in the body of the paper defining the term ‘precision health’ or its derivatives was also extracted.

Data synthesis and analysis

Data were analysed and summarised narratively in text and presented in tables and graphs where appropriate.

Content analysis on free-text data defining precision health and describing the objectives of each study was performed using Leximancer.12 Data were imported into Leximancer, and standard parameters were used to process and clean the data. Specifically, text was analysed in maximum two-sentence segments. Data were processed with standard stop words removed from text automatically. In addition, the search concepts (precision, health, personalised, stratified, tailored and individualised) were included as additional stop words, while analysis of the study aims included ‘aim’ and ‘aims’ as additional stop words. Similar concepts were also merged (eg, intervention and interventions, method and methods).

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in this scoping review.

Results

Article screening

Searches retrieved 8053 articles, with 225 included after removal of duplicates and title, abstract and full-text screening (figure 1; online supplemental appendices 3 and 4A, B). The reference lists of 30 relevant reviews or discussion papers were also searched; however, no additional primary studies were retrieved. Almost half of the articles (104/225, 46.2%) were published between 2017 and 2020, and only three articles (1.3%) in 2010.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram illustrating the steps undertaken for this scoping review. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Context and characteristics of included studies

A summary of study characteristics is presented in table 1. Majority of the studies were in North America (97/225, 43.1%), led by the USA. There were few studies conducted in African (12/225, 5.3%) and South American countries (2/225, 0.9%). Authors were mostly based in health and medical research departments and in universities/academic institutions. Over half of the articles had authors from just one discipline (130/225, 57.8%) and one type of institution (132/225, 58.7%). More than half of the studies (120/225, 53.3%) were directly funded by governments, including national research funding agencies and initiatives.

Table 1.

Funding sources and characteristics of included studies (n=225)

| Articles | % | |

| Funding | ||

| Government | 120 | 53.3 |

| Institutional | 51 | 22.7 |

| Non-governmental | 36 | 16.0 |

| Industry/corporation | 15 | 6.7 |

| International | 9 | 4.0 |

| None | 8 | 3.6 |

| Not listed | 50 | 22.2 |

| Number of authors | ||

| 1–3 | 59 | 26.2 |

| 4–6 | 81 | 36.0 |

| 7–9 | 44 | 19.6 |

| 10–15 | 29 | 12.9 |

| 16–21 | 10 | 4.4 |

| >21 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Ten most common countries (study setting) | ||

| USA | 85 | 37.8 |

| The Netherlands | 20 | 8.9 |

| China | 13 | 5.8 |

| Australia | 12 | 5.3 |

| Korea | 12 | 5.3 |

| Canada | 11 | 4.9 |

| UK | 9 | 4.0 |

| Finland | 5 | 2.2 |

| Taiwan | 5 | 2.2 |

| Germany | 4 | 1.8 |

| Ten most common disciplines involved (based on FoR, ANZSRC)* | ||

| Medical and Health Sciences | 160 | 71.1 |

| Information, Computing and Communication Sciences | 66 | 29.3 |

| Engineering and Technology | 33 | 14.7 |

| Behavioural and Cognitive Sciences | 14 | 6.2 |

| Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts—General | 10 | 4.4 |

| Studies in Human Society | 10 | 4.4 |

| Mathematical Sciences | 7 | 3.1 |

| Biological Sciences | 6 | 2.7 |

| Commerce, Management, Tourism and Services | 6 | 2.7 |

| Science (general) | 4 | 1.8 |

| Institutions | ||

| Academia/university | 212 | 94.2 |

| Hospital/health facility | 63 | 28.0 |

| Industry | 30 | 13.3 |

| Government | 18 | 8.0 |

| Not-for-profit/charity/community centre | 18 | 8.0 |

| Defence | 2 | 0.9 |

| Intended outcome of the study† | ||

| Individual digital health promotion tool (app, website, wearable) | 80 | 35.6 |

| Community/public health programme and system (in-person) | 72 | 32.0 |

| Algorithm | 52 | 23.1 |

| Diagnostic test (omics, microbiome) | 15 | 6.7 |

| Non-diagnostic implanted medical device (for monitoring, prevention, treatment) | 8 | 3.6 |

| Other (questionnaire, exploratory study (1), or survey instrument (2)) | 6 | 2.7 |

| Study design‡ | ||

| Cross-sectional study | 55 | 24.4 |

| Technology/tool testing | 42 | 18.7 |

| Qualitative research | 37 | 16.4 |

| Randomised controlled trial | 36 | 16.0 |

| Non-randomised experimental study | 22 | 9.8 |

| Cohort study | 14 | 6.2 |

| Clinical prediction rule | 12 | 5.3 |

| Diagnostic test accuracy study | 10 | 4.4 |

| Case series | 5 | 2.2 |

| Case–control study | 2 | 0.9 |

| Text and opinion | 2 | 0.9 |

| Protocol | 17 | 7.6 |

The disciplines and institutions involved are based on author affiliation/s.

*FoR (Field of Research) classifies research according to methodology and is one of the three ANZSRC classifications. The ANZSR includes a set of three related classifications for measurement and analysis of research in Australia and New Zealand (https://www.arc.gov.au/grants/grant-application/classification-codes-rfcd-seo-and-anzsic-codes).

†One article can have multiple intended outcomes.

‡One article can include multiple study components with different study designs. We have also identified protocols, and the intended study design of these protocols were also identified.

ANZSRC, Australian and New Zealand Standard Research Classification.

Most articles were leading to the development of an individual digital health promotion tool or community/public health programme, while there were few studies on implanted medical devices. Digital tools for health management included web-based programmes,13–25 mobile phone apps or text messages20 25–34 and wearables.35–38 Community or face-to-face health programmes have been developed for or implemented in churches,39 rural communities,40 41 youth healthcare centres,42 adult day-care centres,43 paediatric practices,44 assisted living facilities,45 hospitals,46–48 mobile health counselling units,49 schools50 and workplaces.51–53

We used the model of Gambhir et al.1 to determine the stage in the precision health ecosystem that our reviewed articles focus on. Their cyclical model involves four key components, (1) risk assessment at all life stages, (2) customised personal and environmental monitoring, and an integrated health portal where (3) data is analysed and (4) personalised interventions are provided. In our review, 105 articles (46.7%) developed or tested an intervention, 53 (23.6%) focused on risk assessment, 42 (18.7%) primarily involved data analytics, and only 25 (11.1%) were dedicated to customised monitoring. Risk assessment articles include studies that determined risk for hospital readmission for people with cardiovascular disease,54 human papillomavirus infection,55 10-year survival of people with myotonic dystrophy56 and diabetes based on lifestyle information.57 Data analytics studies developed algorithms or analysed big datasets to monitor air pollution,58 forecasted wellness from ECG signals59 or categorised diseases.60 Finally, studies on customised monitoring have continuously obtained data on home environments61; metabolites,62 vital signs35 63 or neural activation64 during physical activity; blood glucose and uric acid65; or bioimpedance for respiratory assessment.66

In terms of study design, only 36 articles conducted or planned to conduct a randomised clinical trial, whereas cross-sectional studies made up around a quarter of the articles.

Conditions targeted or addressed

The diseases, behaviours and/or conditions targeted by each study, based on their aims, are presented in the top panel of table 2. Chronic diseases (103/225 articles, 45.8%), including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, are among the 10 most common conditions targeted. There were also studies focused on modifying behaviours, such as physical activity and substance use (28/225, 12.4%). Several studies addressed sexual health issues, including HIV and HPV. In terms of actual participants recruited, 87 articles (38.7%) did not mention the health condition of their participants, and 81 articles (36%) indicated that they recruited participants who have a chronic illness. There were 43 articles (19.1%) that recruited participants at-risk for certain conditions or in a predisease stage, 11 articles (4.89%) that recruited participants with an acute illness and 22 articles (9.78%) that explicitly mentioned the recruitment of ‘healthy’ or non-diseased populations. The 10 most common conditions of participants in articles that involved individuals at-risk or have acute or chronic diseases are presented in the bottom panel of table 2.

Table 2.

Ten most common conditions and/or behaviours targeted (n=225 articles) and ten most common health issues of participants in 126 articles that recruited people who have preclinical, acute or chronic conditions

| Articles | % | |

| Ten most common target diseases/behaviours (225 articles)* | ||

| Metabolic disorder | 35 | 15.6 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 29 | 12.9 |

| General/preventive health, chronic diseases, wellness | 26 | 11.6 |

| Cancer | 26 | 11.6 |

| Physical activity and weight loss | 16 | 7.1 |

| Neurological disorders | 13 | 5.8 |

| Smoking, alcohol and substance use | 12 | 5.3 |

| Sexually transmitted infections and sexual health | 12 | 5.3 |

| Mental health and psychiatric disorders | 11 | 4.9 |

| Overweight, obesity | 11 | 4.9 |

| Ten most common conditions of recruited participants (126 articles)* | ||

| Metabolic disorder | 30 | 23.8 |

| Cancer | 27 | 21.4 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 25 | 19.8 |

| Neurological disorders | 13 | 10.3 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 12 | 9.5 |

| Sexually transmitted infections | 12 | 9.5 |

| Hypertension | 11 | 8.7 |

| Other infectious diseases | 8 | 6.3 |

| Mental health and psychiatric disorders | 6 | 4.8 |

| Obesity/overweight | 6 | 4.8 |

*Articles can target more than one condition and also recruit participants with multiple conditions.

Types of data for personalisation

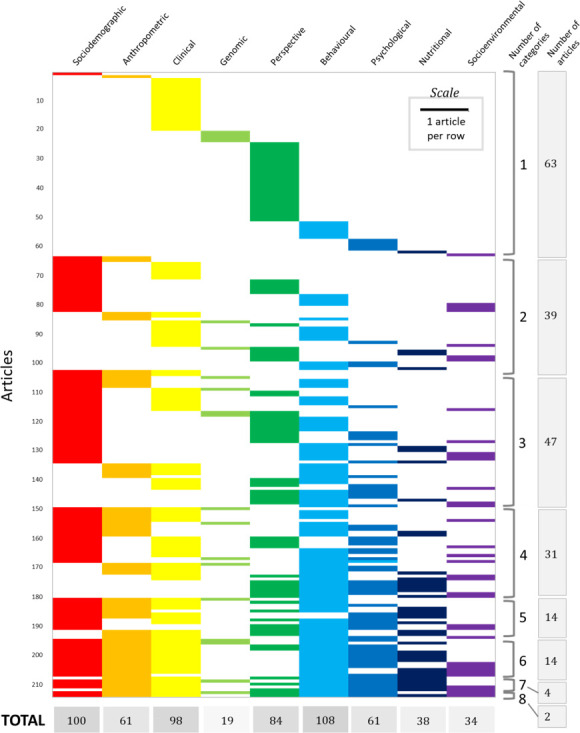

In terms of data gathered for or that had implications for health personalisation (figure 2), 102 studies (45.3%) collected one or two types of data, whereas only 6 studies (2.7%) used seven or more types of data for personalising. Almost half of the studies used behavioural or lifestyle information (108/225, 48%) and more than 40% used sociodemographic (100/225, 44.4%) or clinical (98/225, 43.6%) information; however, genetic data were rarely gathered (19/225, 8.4%). Among the behavioural information that studies have used for personalising health interventions are cigarette or alcohol consumption,25 28 67–72 physical activity,20 22 25 34 42 51 68–73 sleep,23 24 28 sexual behaviour,74 television viewing and computer use42 and/or drug use.68 Sociodemographic and clinical data frequently used for intervention tailoring encompassed age,15 71 75 gender,15 71 75 blood glucose,21 71 76 blood pressure,15 72 77 cholesterol,15 71 body fat,77 78 medical history,15 71 79 comorbidities24 45 and/or disease severity.43 80

Figure 2.

Types of information used or obtained that have implications for personalisation in 214 articles. The type of information gathered is unclear or does not have direct relevance to personalisation in 11 studies.

Participant demographics

Sample sizes varied between one and 7 995 048, with the median being 120 (IQR 28–600). There were 20 studies (8.9%) that included 10 or fewer participants, whereas 12 studies (5.3%) included more than 10 000 participants. The median age of participants was 48 years (IQR 28.4–60.8), with the youngest participant being <1 year old and the oldest, 119 years. Based on the mean or median age of participants recruited in 123 studies providing these information, 100 studies (44.4%) focused on recruiting people from 20 to 69 years old, whereas only 11 studies (4.9%) primarily recruited people below 20 years old and 12 studies (5.3%) primarily recruited people older than 69 years old.

For articles that mentioned participant sex (153/225, 68.0%), the median percentage of female participants is 53.5% (IQR 40%–72%). Of the articles that clearly reported participant race/ethnicity (87/225, 38.7%), the median percentage of non-Caucasian participants recruited per study is 45.5% (IQR 12.02%–100%). Several studies included participants from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds (46/225, 20.4%), including people who have low income or are unemployed, low literacy, limited education, limited internet or technology access and/or no insurance; live in a rural area; and/or are migrants.

Conceptualising precision health

Results of the Leximancer text analysis are presented in figure 3. Mapping the conceptualisation of precision health in the body of the paper (figure 3A, B) reveals that the primary themes relate to patient care, intervention, information or data, monitoring and behaviour. For the study objectives (figure 3C,D), which reflect how precision health is operationalised, primary themes relate to patients, programmes and systems, monitoring, development and effects.

Figure 3.

Thematic maps and charts displaying how precision health and synonyms were conceptualised in the body of the text (n=223 articles; A, B) and the aim of the study (n=224 articles; C, D). The Venn diagrams in (A, C) depict the size, proximity and connectedness of themes (groups of related words and concepts) whereby the colour (red, most prevalent—purple, least prevalent) of the bubble depicts the prevalence of the theme. The bar graphs in (B, D) illustrate the frequency of prevalent themes.

Discussion

This scoping review systematically and rigorously mapped progress, trends and gaps in precision health over the past decade. Various reviews and perspective articles have introduced precision health as an emerging area of research,1 6 7 81 yet it is unknown whether aspirations align with research being conducted and identified as precision health. Although precision health aspires to combine multiple types of information,2 our review demonstrates that most studies only used one or two categories of information for the personalisation of interventions, with behavioural data the most common data type gathered. Most precision health studies also aim to deliver or test an intervention, and individual digital health promotion tools are the most common study outcome.

The vision for precision health, as proposed by Hickey et al.,2 is the integration of phenotype, lifestyle and environmental factors, and genotype and other biomarkers to discover, design and deliver interventions for the prevention or management of disease symptoms. This review demonstrated limited integration of multiple types of data, with 45.3% of the reviewed articles collecting or using only one or two types of data for personalisation applications. Only two studies gathered eight different categories of data, using them to develop a child functional profile82 or community interventions for diabetes and hypertension.83 Our review also showed that behavioural, sociodemographic and clinical data were commonly gathered for personalising interventions or other precision health applications, and limited studies used genomic or socioenvironmental factors. Although this deviates from the focus of precision medicine on genomics,6 the increasing use of behavioural and environmental information suggests increasing acknowledgement of the importance of social and environmental determinants of health.84 Reviewing authors’ disciplinary and institutional affiliations also revealed 34 articles with authors from the behavioural and social sciences, further supporting the important role that these disciplines may play in developing precision health interventions that are attuned to personal needs, relationships and environments and that account for ethical and equity issues.85 Overall, our findings on data used for personalisation indicate that the vision for precision health is yet to be fulfilled, with the need to integrate a broader and more diverse array of measures for health maintenance, disease prevention and disease management or treatment.

Determining the stage in the precision healthcare ecosystem using the model of Gambhir et al.1 revealed that most studies focused on the development of interventions. Examining the outcomes of each study showed that majority developed digital health tools and community programmes. The prevalence of studies that focused on developing digital health tools underscores the key role of computer science in precision health, not just in developing web platforms and mobile health applications, but also in creating algorithms for the analysis of large datasets containing multiple types of information.86 The high percentage of studies developing community programmes illustrates that precision health also encompasses public health and face-to-face interventions, rather than simply using digital technologies and genetic data to assess and/or promote health. This finding also addresses concerns on the dehumanisation87 or depersonalisation88 of healthcare brought about by precision medicine and health information technologies. Reviewing study designs, there were only 36 randomised controlled trials conducted or planned, suggesting that most technologies or programmes are still in the early stages of development and that their efficacy and safety still need to be properly tested in comparison to a control group and outside the laboratory. Taken together, these results demonstrate promising progress in digital technologies and community programmes for precision health and set the challenge for translating technologies to the market or implementing programmes at a much larger scale, in addition to ensuring that they are effective, safe, and applicable to multiple populations and contexts.

Our review has uncovered gaps in recruited participants of certain ages, reporting of participant gender and race/ethnicity, inclusion of people from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds, and countries where precision health research is conducted. Few studies recruited children and adolescents or older adults. Although there are ethical and practical challenges in recruiting children,89 adolescents90 and the elderly,91 there is a need to obtain more data on and test monitoring systems, diagnostics and interventions for health issues experienced by these populations, following precision health’s goal of health maintenance across the lifespan.8 Second, more than one-third of the studies did not report their participants’ gender, less than half reported the race/ethnicity of their participants, and only 21% included individuals from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. These highlight significant gaps in ensuring equitable precision health research and application. Given gender92 93 and racial disparities94–96 in health and medical research, it is crucial to ensure representation of women and racial/ethnic minorities in precision health research, in addition to adequate reporting of outcomes for various participant subpopulations. Third, there are only limited studies conducted in African49 97–103 or South American104 105 countries, underscoring persistent global disparities in health technology innovation106 and medical research.107

The strength of this scoping review lies in the breadth of the search, using synonyms of ‘precision health’11 to capture relevant studies; and the review’s rigour, where each step was conducted in independent duplicate. This review can serve as basis for future synthesis of precision health advances, which can expand the current review’s scope and fill in its limitations. Our review excluded dissertations and unpublished clinical trials, which could highlight preliminary findings and emerging advances in the field.108 We no longer included patents since their structure does not align with our data extraction sheet, limiting the information that can be extracted and compared with academic publications. Future reviews should include non-English publications and should expand the search strategy to better capture emerging subdisciplines such as ‘precision public health’5 and ‘precision mental health’.109 Although including stakeholder voices to re-examine findings110 is not required for scoping reviews,9 this step could be vital in understanding how precision health researchers perceive progress in the field and how they can address research gaps.

Precision health is a rapidly growing field driven by a vision of integrating biological, psychological, lifestyle, social and environmental information to assess health status and provide interventions for maintaining or restoring health. To fulfil this aspiration and to address existing gaps, additional interdisciplinary work is needed in integrating different types of information and in determining the safety and efficacy of interventions using randomised controlled trials. Precision health studies can take advantage of ongoing precision medicine programs111 112 to include genomic information in health monitoring and management. Precision health teams also need to include computer scientists and social scientists to better understand social and environmental determinants of health and integrate them with individual biological and behavioural data. Finally, future studies should include data from children and the elderly, report participant gender and race/ethnicity, and be conducted in South America and Africa. Fostering diversity and inclusion will allow analyses of larger and more diverse datasets, which can then facilitate more accurate assessment of the disease risk and health status of individuals from a wide range of populations and contexts. For precision health to truly fulfil its promise, crucial steps must be taken to facilitate interdisciplinary, ethical, responsible and inclusive research, paving the way for quality healthcare regardless of age, gender, class, ethnicity and nationality.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @John_Noel_Viana, @smartineedney, @svgondalia, @Sellak_Hamza, @jillianclairer1

Contributors: JNV conceptualised and managed the project; collected, curated, analysed and visualised the data; and wrote the original and revised draft. JNV is also the guarantor; who accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. JCR conceptualised and managed the project; collected, curated, analysed and visualised the data; and wrote and reviewed the draft. SE and CM collected, curated, analysed and visualised the data; and wrote and reviewed the draft, SG and HS collected and curated the data and reviewed the draft. NO’C conceptualised the project, reviewed the draft and provided funding for the publication of the scoping review protocol.

Funding: The researchers involved in this study are funded by the Australian National University, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, and/or the National University of Singapore. JNV acknowledges the ANU-CSIRO (Australian National University-Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation) Responsible Innovation collaboration for funding and support. There are no relevant grant numbers to mention.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systemic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines. Since no human participants or animals were involved in this study, an ethics committee approval was not necessary.

References

- 1.Gambhir SS, Ge TJ, Vermesh O, et al. Toward achieving precision health. Sci Transl Med 2018;10:5. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickey KT, Bakken S, Byrne MW, et al. Corrigendum to precision health: advancing symptom and self-management science. Nurs Outlook 2020;68:139–40. 10.1016/j.outlook.2019.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGowan ML, Settersten RA, Juengst ET, et al. Integrating genomics into clinical oncology: ethical and social challenges from proponents of personalized medicine. Urol Oncol 2014;32:187–92. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Contrepois K, Moneghetti KJ, et al. A longitudinal big data approach for precision health. Nat Med 2019;25:792–804. 10.1038/s41591-019-0414-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury MJ, Iademarco MF, Riley WT. Precision public health for the era of precision medicine. Am J Prev Med 2016;50:398–401. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juengst ET, McGowan ML. Why Does the Shift from "Personalized Medicine" to "Precision Health" and "Wellness Genomics" Matter? AMA J Ethics 2018;20:E881–90. 10.1001/amajethics.2018.881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Payne PRO, Detmer DE. Language matters: precision health as a cross-cutting care, research and policy agenda. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020;27:658–61. 10.1093/jamia/ocaa009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan JC, Viana JN, Sellak H, et al. Defining precision health: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2021;11:e044663. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, et al. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc 2015;13:141–6. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali-Khan S, Kowal S, Luth W. Terminology for personalized medicine: a systematic collection. PACEOMICS 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith AE, Humphreys MS. Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behav Res Methods 2006;38:262–79. 10.3758/bf03192778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arens JH, Hauth W, Weissmann J. Novel App- and Web-Supported diabetes prevention program to promote weight reduction, physical activity, and a healthier lifestyle: observation of the clinical application. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2018;12:831–8. 10.1177/1932296818768621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazdarevic SH, Cristea AI. How emotions stimulate people affected by cancer to use personalised health websites. Knowl Manage E-Learn 2015;7:658–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colkesen EB, Ferket BS, Tijssen JGP, et al. Effects on cardiovascular disease risk of a web-based health risk assessment with tailored health advice: a follow-up study. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2011;7:67. 10.2147/VHRM.S16340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortese J, Lustria MLA. Can tailoring increase elaboration of health messages delivered via an adaptive educational site on adolescent sexual health and decision making? J Am Soc Inf Sci Tec 2012;63:1567–80. 10.1002/asi.22700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Côté J, Cossette S, Ramirez-Garcia P, et al. Evaluation of a web-based tailored intervention (TAVIE en santé) to support people living with HIV in the adoption of health promoting behaviours: an online randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1042. 10.1186/s12889-015-2310-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faro JM, Orvek EA, Blok AC, et al. Dissemination and effectiveness of the peer marketing and messaging of a Web-Assisted tobacco intervention: protocol for a hybrid effectiveness trial. JMIR Res Protoc 2019;8:13. 10.2196/14814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray KM, Clarke K, Alzougool B, et al. Internet protocol television for personalized home-based health information: design-based research on a diabetes education system. JMIR Res Protoc 2014;3:e13. 10.2196/resprot.3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KM, Park KS, Lee HJ, et al. Efficacy of a new medical information system, ubiquitous healthcare service with voice inception technique in elderly diabetic patients. Sci Rep 2015;5:10. 10.1038/srep18214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KJ, Shin D-H, Yoon H. Information tailoring and framing in wearable health communication. Inf Process Manag 2017;53:351–8. 10.1016/j.ipm.2016.11.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leinonen A-M, Pyky R, Ahola R, et al. Feasibility of Gamified mobile service aimed at physical activation in young men: population-based randomized controlled study (MOPO). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e146. 10.2196/mhealth.6675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marthick M, Janssen A, Cheema BS, et al. Feasibility of an interactive patient portal for monitoring physical activity, remote symptom reporting, and patient education in oncology: qualitative study. JMIR Cancer 2019;5:e15539. 10.2196/15539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McHugh J, Suggs LS. Online tailored weight management in the worksite: does it make a difference in biennial health risk assessment data? J Health Commun 2012;17:278–93. 10.1080/10810730.2011.626496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samaan Z, Schulze KM, Middleton C, et al. South Asian heart risk assessment (Sahara): randomized controlled trial design and pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc 2013;2:e33. 10.2196/resprot.2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elbert SP, Dijkstra A, Oenema A. A mobile phone APP intervention targeting fruit and vegetable consumption: the efficacy of Textual and auditory tailored health information tested in a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:18. 10.2196/jmir.5056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore LA, Klempel MC, Martin CK, et al. Personalized mobile health intervention for health and weight loss in postpartum women receiving women, infants, and children benefit: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Womens Health 2017;26:719–27. 10.1089/jwh.2016.5947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kizakevich PN, Eckhoff R, Brown J, et al. PHIT for duty, a mobile application for stress reduction, sleep improvement, and alcohol moderation. Mil Med 2018;183:353–63. 10.1093/milmed/usx157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fadhil A, Wang Y, Reiterer H. Assistive Conversational agent for health coaching: a validation study. Methods Inf Med 2019;58:9–23. 10.1055/s-0039-1688757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatwood J, Shuvo S, Ross A, et al. The management of diabetes in everyday life (model) program: development of a tailored text message intervention to improve diabetes self-care activities among underserved African-American adults. Transl Behav Med 2020;10:204–12. 10.1093/tbm/ibz024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hors-Fraile S, Schneider F, Fernandez-Luque L, et al. Tailoring motivational health messages for smoking cessation using an mHealth recommender system integrated with an electronic health record: a study protocol. BMC Public Health 2018;18:10. 10.1186/s12889-018-5612-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lim S, Kang SM, Shin H, et al. Improved glycemic control without hypoglycemia in elderly diabetic patients using the ubiquitous healthcare service, a new medical information system. Diabetes Care 2011;34:308–13. 10.2337/dc10-1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman-Casey PA, Niziol LM, Mackenzie CK, et al. Personalized behavior change program for glaucoma patients with poor adherence: a pilot interventional cohort study with a pre-post design. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2018;4:128. 10.1186/s40814-018-0320-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rabbi M, Aung MH, Zhang M. MyBehavior: automatic personalized health feedback from user behaviors and preferences using smartphones. UbiComp - Proc ACM Int Jt Conf Pervasive Ubiquitous Comput 2015:707–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong YJ, Lee H, Kim J, et al. Multifunctional wearable system that integrates Sweat-Based sensing and Vital-Sign monitoring to estimate Pre-/Post-Exercise glucose levels. Adv Funct Mater 2018;28:12. 10.1002/adfm.201805754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim WK, Davila S, Teo JX, et al. Beyond fitness tracking: the use of consumer-grade wearable data from normal volunteers in cardiovascular and lipidomics research. PLoS Biol 2018;16:18. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nedungadi P, Jayakumar A, Raman R. Personalized Health Monitoring System for Managing Well-Being in Rural Areas. J Med Syst 2018;42:11. 10.1007/s10916-017-0854-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rykov Y, Thach T-Q, Dunleavy G, et al. Activity Tracker-Based metrics as digital markers of cardiometabolic health in working adults: cross-sectional study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8:e16409. 10.2196/16409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abbott L, Gordon Schluck G, Graven L, et al. Exploring the intervention effect moderators of a cardiovascular health promotion study among rural African-Americans. Public Health Nurs 2018;35:126–34. 10.1111/phn.12377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oh EG, Yoo JY, Lee JE, et al. Effects of a three-month therapeutic lifestyle modification program to improve bone health in postmenopausal Korean women in a rural community: a randomized controlled trial. Res Nurs Health 2014;37:292–301. 10.1002/nur.21608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou B, Chen K, Yu Y, et al. Individualized health intervention: behavioral change and quality of life in an older rural Chinese population. Educ Gerontol 2010;36:919–39. 10.1080/03601271003689514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raat H, Struijk MK, Remmers T, et al. Primary prevention of overweight in preschool children, the BeeBOFT study (breastfeeding, breakfast daily, outside playing, few sweet drinks, less TV viewing): design of a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013;13:11. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang AK, Park Y-H, Fritschi C, et al. A family involvement and patient-tailored health management program in elderly Korean stroke patients' day care centers. Rehabil Nurs 2015;40:179–87. 10.1002/rnj.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simione M, Sharifi M, Gerber MW, et al. Family-centeredness of childhood obesity interventions: psychometrics & outcomes of the family-centered care assessment tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2020;18:179. 10.1186/s12955-020-01431-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kemp CL, Ball MM, Perkins MM. Individualization and the health care mosaic in assisted living. Gerontologist 2019;59:644–54. 10.1093/geront/gny065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berks D, Hoedjes M, Raat H, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention after complicated pregnancies to improve risk factors for future cardiometabolic disease. Pregnancy Hypertens 2019;15:98–107. 10.1016/j.preghy.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu CC, Liu XM, Jiang Q. Impact of individualized health management on self-perceived burden, fatigue and negative emotions in angina patients. Int J Clin Exp Med 2019;12:2612–7. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun J, Zhang Z-W, Ma Y-X, et al. Application of self-care based on full-course individualized health education in patients with chronic heart failure and its influencing factors. World J Clin Cases 2019;7:2165–75. 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i16.2165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mabuto T, Charalambous S, Hoffmann CJ. Effective interpersonal health communication for linkage to care after HIV diagnosis in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74 Suppl 1:S23–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Dongen BM, Ridder MAM, Steenhuis IHM, et al. Background and evaluation design of a community-based health-promoting school intervention: fit lifestyle at school and at home (flash). BMC Public Health 2019;19:11. 10.1186/s12889-019-7088-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tucker S, Farrington M, Lanningham-Foster LM, et al. Worksite physical activity intervention for ambulatory clinic nursing staff. Workplace Health Saf 2016;64:313–25. 10.1177/2165079916633225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blake H, Hussain B, Hand J, et al. Employee perceptions of a workplace HIV testing intervention. Int J Workplace Health Manag 2018;11:333–48. 10.1108/IJWHM-03-2018-0030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haslam C, Kazi A, Duncan M. Walking Works Wonders: A Workplace Health Intervention Evaluated Over 24 Months. In: Bagnara S, Tartaglia R, Albolino S, eds. Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International ergonomics association. Cham: Springer International Publishing Ag, 2019: 1571–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu CY, Chi SQ, RZ L. Design and development of a readmission risk assessment system for patients with cardiovascular disease. Proc - Int Conf Inf Technol Med Educ, ITME 2017:121–4. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson EL, Vamos CA, Straub DM, et al. "We've Been Together. We Don't Have It. We're Fine." How Relationship Status Impacts Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Behavior among Young Adult Women. Womens Health Issues 2017;27:228–36. 10.1016/j.whi.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wahbi K, Porcher R, Laforêt P, et al. Development and validation of a new scoring system to predict survival in patients with myotonic dystrophy type 1. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:573–81. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lan GC, Lee CH, Lee YY. Disease risk prediction by mining personalized health trend patterns: a case study on diabetes. Proc - Conf Technol Appl Artif Intell, TAAI 2012:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen LL, Xu J, Zhang L. Big data analytic based personalized air quality health Advisory model. 2017 13th IEEE Conference on Automation Science and Engineering. New York: Ieee, 2017:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fan X, Zhao Y, Wang H, et al. Forecasting one-day-forward wellness conditions for community-dwelling elderly with single lead short electrocardiogram signals. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019;19:14. 10.1186/s12911-019-1012-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khalilia M, Chakraborty S, Popescu M. Predicting disease risks from highly imbalanced data using random forest. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011;11:13. 10.1186/1472-6947-11-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmed MU. A Personalized Health-Monitoring System for Elderly by Combining Rules and Case-Based Reasoning. In: Blobel B, Linden M, Ahmed MU, eds. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on wearable micro and nano technologies for personalized health. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2015: 249–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bariya M, Shahpar Z, Park H, et al. Roll-to-Roll Gravure printed electrochemical sensors for wearable and medical devices. ACS Nano 2018;12:6978–87. 10.1021/acsnano.8b02505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pozaic T, Varga M, Dzaja D. Closed-Loop system for assisted strength exercising. Rijeka: Croatian Soc Inf & Commun Technol, Electronics & Microelectronics-Mipro, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bosak KA, Papa VB, Brucks MG, et al. Novel biomarkers of physical activity maintenance in midlife women: preliminary investigation. Biores Open Access 2018;7:39–46. 10.1089/biores.2018.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Guo J. Smartphone-Powered electrochemical biosensing Dongle for emerging medical IoTs application. IEEE Trans Industr Inform 2018;14:2592–7. 10.1109/TII.2017.2777145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vela LM, Kwon H, Rutkove SB, et al. Standalone IoT bioimpedance device supporting real-time online data access. IEEE Internet Things J 2019;6:9545–54. 10.1109/JIOT.2019.2929459 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.An LC, Demers MRS, Kirch MA, et al. A randomized trial of an avatar-hosted multiple behavior change intervention for young adult smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2013;2013:209–15. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgt021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Noble N, Paul C, Carey M, et al. A randomised trial assessing the acceptability and effectiveness of providing generic versus tailored feedback about health risks for a high need primary care sample. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:8. 10.1186/s12875-015-0309-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Prichard I, Lee A, Hutchinson AD, et al. Familial risk for lifestyle-related chronic diseases: can family health history be used as a motivational tool to promote health behaviour in young adults? Health Promot J Austr 2015;26:122–8. 10.1071/HE14104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu T. The effects of a health partner program on alleviating depressive symptoms among healthy overweight/obese individuals. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2018;32:400–12. 10.1891/1541-6577.32.4.400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van den Brekel-Dijkstra K, Rengers AH, Niessen MAJ, et al. Personalized prevention approach with use of a web-based cardiovascular risk assessment with tailored lifestyle follow-up in primary care practice--a pilot study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:544–51. 10.1177/2047487315591441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Limpt PM, Harting J, van Assema P, et al. Effects of a brief cardiovascular prevention program by a health advisor in primary care; the 'Hartslag Limburg' project, a cluster randomized trial. Prev Med 2011;53:395–401. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Youm S, Liu S. Development healthcare PC and multimedia software for improvement of health status and exercise habits. Multimed Tools Appl 2017;76:17751–63. 10.1007/s11042-015-2998-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rikard RV, Thompson MS, Head R, et al. Problem posing and cultural tailoring: developing an HIV/AIDS health literacy toolkit with the African American community. Health Promot Pract 2012;13:626–36. 10.1177/1524839911416649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ayres K, Conner M, Prestwich A, et al. Exploring the question-behaviour effect: randomized controlled trial of motivational and question-behaviour interventions. Br J Health Psychol 2013;18:31–44. 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bassett RL, Ginis KAM. Risky business: the effects of an individualized health information intervention on health risk perceptions and leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury. Disabil Health J 2011;4:165–76. 10.1016/j.dhjo.2010.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee H-J, Kang K-J, Park S-H, et al. Effect of integrated personalized health care system on middle-aged and elderly women's health. Healthc Inform Res 2012;18:199–207. 10.4258/hir.2012.18.3.199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hollands GJ, Marteau TM. The impact of using visual images of the body within a personalized health risk assessment: an experimental study. Br J Health Psychol 2013;18:263–78. 10.1111/bjhp.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Drake C, Meade C, Hull SK, et al. Integration of personalized health planning and shared medical appointments for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. South Med J 2018;111:674–82. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stienen JJ, Ottevanger PB, Wennekes L, et al. Development and evaluation of an educational E-Tool to help patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma manage their personal care pathway. JMIR Res Protoc 2015;4:e6. 10.2196/resprot.3407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dickson C, Hyppönen E. Precision health: a primer for physiotherapists. Physiotherapy 2020;107:66–70. 10.1016/j.physio.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weijers M, Feron FJM, Bastiaenen CHG. The 360CHILD-profile, a reliable and valid tool to visualize integral child-information. Prev Med Rep 2018;9:29–36. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mohan S, Jarhyan P, Ghosh S, et al. UDAY: a comprehensive diabetes and hypertension prevention and management program in India. BMJ Open 2018;8:15. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams JR, Lorenzo D, Salerno J, et al. Current applications of precision medicine: a bibliometric analysis. Per Med 2019;16:351–9. 10.2217/pme-2018-0089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hekler E, Tiro JA, Hunter CM, et al. Precision health: the role of the social and behavioral sciences in advancing the vision. Ann Behav Med 2020;54:805–26. 10.1093/abm/kaaa018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ho D, Quake SR, McCabe ERB, et al. Enabling technologies for personalized and precision medicine. Trends Biotechnol 2020;38:497–518. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bailey JE. Does health information technology dehumanize health care? Virtual Mentor 2011;13:181–5. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.3.msoc1-1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Horwitz RI, Cullen MR, Abell J, et al. (De)Personalized Medicine. Science 2013;339:1155–6. 10.1126/science.1234106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Canadian Paediatric Society . Ethical issues in health research in children. Paediatr Child Health 2008;13:707–20. 10.1093/pch/13.8.707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crane S, Broome ME. Understanding ethical issues of research participation from the perspective of participating children and adolescents: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2017;14:200–9. 10.1111/wvn.12209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ridda I, MacIntyre CR, Lindley RI, et al. Difficulties in recruiting older people in clinical trials: an examination of barriers and solutions. Vaccine 2010;28:901–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nowogrodzki A. Inequality in medicine. Nature 2017;550:S18–19. 10.1038/550S18a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hayes SN, Redberg RF. Dispelling the myths: calling for sex-specific reporting of trial results. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:523–5. 10.4065/83.5.523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Loree JM, Anand S, Dasari A, et al. Disparity of race reporting and representation in clinical trials leading to cancer drug approvals from 2008 to 2018. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:e191870–e70. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Parvanova I, Finkelstein J. Disparities in racial and ethnic representation in stem cell clinical trials. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020;272:358–61. 10.3233/SHTI200569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Flores LE, Frontera WR, Andrasik MP, et al. Assessment of the inclusion of racial/ethnic minority, female, and older individuals in vaccine clinical trials. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2037640. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Badawi H, Eid M, El Saddik A. A real-time biofeedback health Advisory system for children care. Proc IEEE Int Conf Multimedia Expo Workshops, ICMEW 2012:429–34. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Fayorsey RN, Wang C, Chege D, et al. Effectiveness of a lay Counselor-Led combination intervention for retention of mothers and infants in HIV care: a randomized trial in Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019;80:56–63. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ferrão JL, Mendes JM, Painho M. Modelling the influence of climate on malaria occurrence in Chimoio Municipality, Mozambique. Parasit Vectors 2017;10:12. 10.1186/s13071-017-2205-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kerrigan D, Sanchez Karver T, Muraleetharan O, et al. "A dream come true": Perspectives on long-acting injectable antiretroviral therapy among female sex workers living with HIV from the Dominican Republic and Tanzania. PLoS One 2020;15:e0234666. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Magadzire BP, Joao G, Shendale S, et al. Reducing missed opportunities for vaccination in selected provinces of Mozambique: a study protocol. Gates Open Res 2017;1:5. 10.12688/gatesopenres.12761.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pak GD, Haselbeck AH, Seo HW, et al. The HPAfrica protocol: Assessment of health behaviour and population-based socioeconomic, hygiene behavioural factors - a standardised repeated cross-sectional study in multiple cohorts in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021438. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Reid M, Walsh C, Raubenheimer J, et al. Development of a health dialogue model for patients with diabetes: a complex intervention in a low-/middle income country. Int J Afr Nurs Sci 2018;8:122–31. 10.1016/j.ijans.2018.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Borbolla D, Del Fiol G, Taliercio V. Integrating Personalized Health Information from MedlinePlus in a Patient Portal. In: Lovis C, Seroussi B, Hasman A, eds. E-Health - for Continuity of Care. Amsterdam: IOS Press, 2014: 348–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Guiñazú MarÃa Flavia, Cortés VÃctor, Ibáñez CF. Employing online social networks in precision-medicine approach using information fusion predictive model to improve substance use surveillance: a lesson from Twitter and marijuana consumption. Information Fusion 2020;55:150–63. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Loncar-Turukalo T, Zdravevski E, Machado da Silva J, et al. Literature on wearable technology for connected health: Scoping review of research trends, advances, and barriers. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e14017. 10.2196/14017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Evans JA, Shim J-M, Ioannidis JPA. Attention to local health burden and the global disparity of health research. PLoS One 2014;9:e90147. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Baudard M, Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, et al. Impact of searching clinical trial registries in systematic reviews of pharmaceutical treatments: methodological systematic review and reanalysis of meta-analyses. BMJ 2017;356:j448. 10.1136/bmj.j448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bickman L, Lyon AR, Wolpert M. Achieving Precision Mental Health through Effective Assessment, Monitoring, and Feedback Processes : Introduction to the Special Issue. Adm Policy Ment Health 2016;43:271–6. 10.1007/s10488-016-0718-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cooper S, Cant R, Kelly M, et al. An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality. Clin Nurs Res 2021;30:230–40. 10.1177/1054773819846024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Turnbull C, Scott RH, Thomas E, et al. The 100 000 Genomes Project: bringing whole genome sequencing to the NHS. BMJ 2018;361:k1687. 10.1136/bmj.k1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.All of Us Research Program Investigators, Denny JC, Rutter JL, et al. The "All of Us" Research Program. N Engl J Med 2019;381:668–76. 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056938supp001.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.