Abstract

The activation of Nef-associated kinase (NAK) by Nef from human and simian immunodeficiency viruses is critical for efficient viral replication and pathogenesis. This induction occurs via the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav and the small GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42. In this study, we identified NAK as p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1). PAK1 bound to Nef in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, the induction of cytoskeletal rearrangements such as the formation of trichopodia, the activation of Jun N-terminal kinase, and the increase of viral production were blocked by an inhibitory peptide that targets the kinase activity of PAK1 (PAK1 83-149). These results identify NAK as PAK1 and emphasize the central role its kinase activity plays in cytoskeletal rearrangements and cellular signaling by Nef.

Nef is a 27- to 35-kDa myristylated accessory protein which is unique to primate lentiviruses human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). Although dispensable for viral replication in cell lines, Nef is critical for maintaining high levels of viremia and for the progression to AIDS in the infected host. Infections of rhesus macaques with SIV containing large deletions in the nef gene did not lead to disease. In contrast, rapid reversions of deleterious point mutations and small deletions in the nef gene restored the full pathogenic potential of the virus (19, 20, 40). The importance of Nef was also demonstrated for HIV-1 in the SCID/hu mouse (17) and in humans who were infected with viral strains carrying deletions in the nef gene (10, 22).

Whereas the importance of Nef for the pathogenesis of HIV and SIV is undisputed, its exact mechanism of action remains elusive. At least three different functions have been attributed to Nef. First, Nef directs CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I determinants to endosomal compartments and their degradation (14, 25, 27, 31, 42). Second, Nef increases viral infectivity at a postentry step in the viral replicative cycle (2, 7, 41). Third, depending on its intracellular localization, Nef activates or inhibits cellular signaling pathways (4). For these latter effects, Nef interacts with a number of cellular tyrosine and serine-threonine kinases. Members of the Src kinase family can bind to the N terminus or the proline-rich motif in Nef (5, 24, 37). Additionally, the guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) Vav binds to this motif in Nef (12). This interaction leads to the activation of the GEF activity of Vav, which induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions. Vav recruits the small GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42, which are required for the activity of Nef-associated kinase (NAK) (8, 16, 26). The association with and activation of NAK by Nef requires the conserved proline-rich motif and diarginine residues in the core domain of Nef (28, 39, 45). When rhesus macaques were infected with SIV bearing mutations in either motif, monkeys failed to develop AIDS until reversions of prolines or arginines were observed (20, 40).

NAK was first described as two phosphoproteins with apparent molecular masses of 62 (p62) and 72 kDa (p72) (38). p62 is a cellular serine-threonine kinase that is recognized by antibodies against N- and C-terminal epitopes of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1), and p72 is most likely the substrate of NAK (26, 30, 40). To date, four different members of the PAK family (PAK1 to PAK4) have been identified. They contain similar N-terminal regulatory domains composed of three proline-rich motifs, a GTPase binding site (Cdc42-Rac1 interactive binding [CRIB] domain) and a stretch of acidic amino acids (aa) (see Fig. 2A). Their C termini contain large catalytic domains (for reviews, see references 23 and 43). Whereas PAK1 and PAK2 play identical roles in cytoskeletal rearrangements and cellular signaling such as the activation of Raf-1, PAK2 is also involved in apoptotic cell death (13, 21, 35). PAK3 is expressed exclusively in the brain, and PAK4 is localized to the Golgi apparatus (1, 21). Although previous studies documented the immunological relationship between NAK and the PAK family (26, 30, 40), they could not demonstrate a direct physical and functional interaction between Nef and a specific PAK isoform and thus failed to identify NAK.

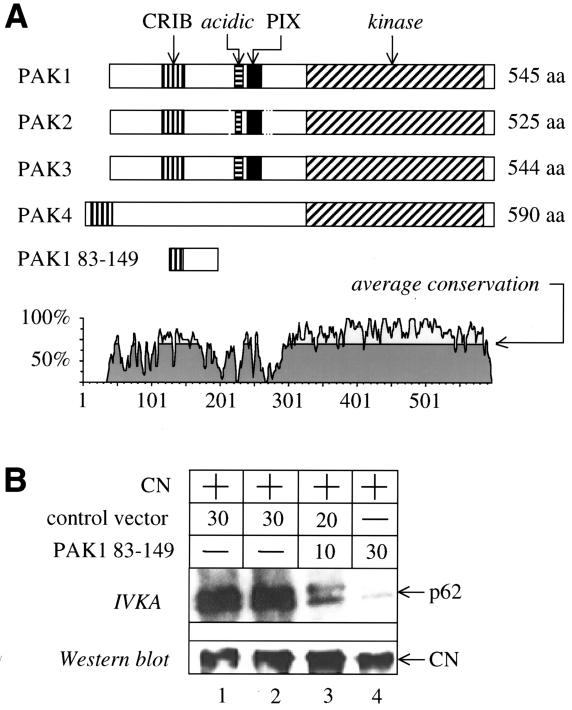

FIG. 2.

Blocking PAK1 kinase activity inhibits NAK activity. (A) Schematic representation of PAK1 to PAK4 and the inhibitory PAK1 83-149 peptide. Each of the PAK isoforms contains a GTPase binding site (CRIB domain) and a kinase domain. Only PAK4 lacks an acidic domain and a proline-rich binding site for the GEF PIX. The lower panel depicts sequence homologies of all members of the PAK family. Numbers refer to residues in PAK4. (B) The PAK1 83-149 peptide inhibits NAK in Jurkat cells. The hybrid CN was coexpressed with an empty plasmid vector (control vector) or the PAK1 83-149 peptide. Cellular lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-CD8 antibody followed by an in vitro kinase assay (IVKA). The kinase activity of NAK was revealed by radioautography of gels transferred to membranes. Note that in Jurkat cells, two proteins (p62 and p72) are phosphorylated by NAK. The same blot was also subjected to Western blotting with the anti-Nef antibody to demonstrate that comparable amounts of the hybrid CN were present in these immunoprecipitations (Western blot).

In this study, we sought to identify the specific PAK that provides the kinase activity of NAK. In vivo and in vitro studies revealed that NAK can be PAK1. Furthermore, an inhibitory fragment that was reported to be specific for PAK1 blocked the activation of NAK, the formation of trichopodia, and the induction of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and increased viral production in a manner that depended on Nef. After submission of this work, another group using a different allele of Nef suggested that NAK could also be PAK2 (34). Taken together, these studies identify NAK as two members of the PAK family that have interchangeable effects on the actin cytoskeleton and cellular signaling cascades.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

Plasmids encoding Vav, CD8-Nef fusion proteins, and Nef.GFP and NefPP-AA.GFP were described earlier (12, 26). NefRR-LL.GFP was generated by subcloning the HIV-1SF2nef with the RR-LL mutation into the green fluorescent protein (GFP) vector pEGFP-N1 (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.). Nucleotide sequences of novel constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Proviral constructs of HIV-1SF2 and HIV-1SF2ΔNef were gifts from Cecilia Cheng-Mayer (Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, New York, N.Y.). The expression plasmid for glutathione S-transferase (GST)–PAK1 was generated by subcloning a fragment encoding aa 1 to 436 of PAK1 into the pGEX-2TK vector. The eukaryotic expression plasmid for PAK1 83-149 was described earlier (13). The expression plasmid for myc-tagged PAK1 was a generous gift from Art Weiss (University of California, San Francisco).

Cell lines, transfection, and microinjection.

Jurkat and COS cells were cultivated as described earlier (26). Transfections were performed by electroporation for Jurkat cells and by lipofection using Lipofectamine (GIBCO, Grand Island, N.Y.) for COS cells following standard protocols. For microinjection experiments, NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and were plated onto glass coverslips as previously described (3). Following incubation in low-serum media containing 0.1% FCS for 36 h prior to injection, cells were microinjected with an Eppendorf 5171/5246 microinjection apparatus by using pulled borosilicate glass capillaries. Plasmids (10 μg/ml unless indicated otherwise) were diluted 1:1 in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline with deionized water.

Immunoprecipitation.

Transfected COS cells were washed with phosphate-buffer saline (PBS) twice and were lysed in 1 ml of kinase extraction buffer (KEB) containing 1% NP-40, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors at 4°C for 20 min. The cell lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were incubated with 1 μl of anti-N20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) or anti-CD8 antibody, respectively, at 4°C for 1 h. The samples were then mixed with 40 μl of protein A-conjugated agarose beads for 2 h, and the immunoprecipitations were washed four times and resuspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer. Western blot analysis of the samples was performed following standard procedures by using the ECL kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.).

Purification of the Nef-NAK complex.

Nef-NAK complexes were isolated from Jurkat cells transiently expressing the hybrid CD8-Nef protein. Cells (107 per ml) were lysed in KEB and were loaded onto a MonoQ column (Pharmacia, Pisacataway, N.J.) previously equilibrated with KEB lacking salt. Proteins were eluted from the column in 1-ml fractions by washing with 30 ml of KEB with increasing salt concentrations (0 to 0.5 M NaCl). Individual fractions were then assayed for protein content by Western blotting and were subjected to in vitro kinase analysis following immunoprecipitation with the anti-CD8 antibody.

Immunofluorescence and digital imaging.

Three hours after the microinjection with expression plasmids coding for hybrid Nef.GFP proteins or GFP alone, cells were fixed with 3.7% (vol/vol) formaldehyde-PBS for 10 min, were permeabilized with 0.3% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, and were incubated with tetramethylrhodamine isocyanate (TRITC)-phalloidin in PBS for 1 h in a humidified atmosphere at ambient room temperature. c-Jun serine-63 phosphorylation (expressed from EF-NLex.Jun [33]) was monitored by indirect immunofluorescence by using phosphospecific antisera (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) and Texas red donkey anti-rabbit antisera (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) as previously described (3). Fluorescence was monitored with a Leica DMXRA microscope using 100× or 40× magnification oil-immersion objectives (numerical aperture, 1.7). Images were captured with fixed exposure times with a Diagnostics CCD camera and were processed identically with Adobe Photoshop as PICT files, and figures were assembled with ClarisDraw.

Antibodies.

The polyclonal rabbit sera against PAK1, hemagglutinin (HA), and Myc were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The monoclonal antibody (MAb) against Nef from HIV was a generous gift from Earl Sawai, University of California, Davis. The MAb against human CD8 was from Art Weiss, University of California, San Francisco.

In vitro kinase assay.

In vitro kinase reactions were performed as described earlier (26). Briefly, 5 × 106 transfected cells were lysed in 1 ml of KEB, and cleared supernatants were immunoprecipitated with 1 μl of anti-CD8 MAb. After extensive washing, the immunoprecipitated complex was resuspended in 100 μl of kinase assay buffer containing 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP per ml. The kinase reaction was conducted at room temperature for 5 min, and the samples were washed and subjected to autoradiography.

GST fusions and in vitro binding studies.

The GST-PAK1 fusion protein was expressed in Escherichia coli and was purified on glutathione-Sepharose beads. Equal amounts of GST and GST fusion protein immobilized on the beads were incubated with purified HIV-1SF2 Nef or mutant HIV-1SF2NefRR-LL protein expressed from baculovirus in insect cells. No contaminating proteins were detected in these preparations of Nef. The binding reaction was performed at 4°C for 2 h in KEB. The beads were then washed three times with KEB containing 1 M NaCl, and bound proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were analyzed by Western blotting.

Virus production assay.

Jurkat cells (5 × 106) were electroporated under standard conditions with 5 μg of proviral DNA and 15 μg of VavΔDH, Sek-AL, PAK1 83-149, or empty plasmid vector, and were subsequently cultured in 5 ml of medium. At 48 h posttransfection, cell culture supernatants were harvested and filtered through a 45-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) and were stored at −70°C. Virus production was quantified by p24Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.). To distinguish between intracellular and extracellular p24Gag, pellets from 1 ml of cell suspension were washed in PBS and lysed in 1 ml of KEB, and p24 concentrations in cell supernatant and cell lysate were determined by p24Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

RESULTS

PAK1 is present in the 1-mDa complex that contains Nef and NAK.

To identify NAK, we purified Nef complexes from Jurkat cells expressing the hybrid CD8-Nef protein (CN) using MonoQ gel chromatography followed by immunoprecipitation with the anti-CD8 antibody. In vitro kinase assays (IVKA) revealed the presence of NAK in fractions 8 to 14 (Fig. 1A). The molecular mass of this complex was estimated to be 1 mDa by size exclusion chromatography (data not shown). In control experiments, no kinase activity could be detected in fractions from Jurkat cells expressing the truncated CD8 or the mutant hybrid CD8-NefRR-LL proteins that do not associate with NAK (data not shown; 39). Western blotting revealed the presence of Nef in the same fractions (Fig. 1A, Western blot and CN). When the membrane was probed with the N20 antibody, only one specific band was detected in the fractions that contained Nef and NAK (Fig. 1A, Western blot and PAK1). Since the anti-N20 antibody recognizes PAK1 preferentially, the detected protein could be PAK1. Reprobing this membrane with other specific antibodies also revealed the presence of Vav in these fractions (data not shown). Thus, PAK1 is most likely present in large complexes containing Nef and NAK in cells.

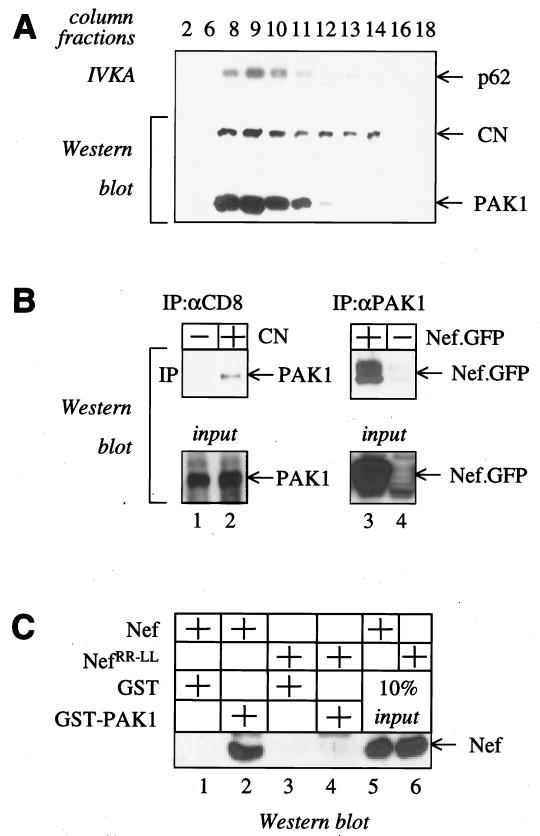

FIG. 1.

Nef interacts with PAK1 in vivo and in vitro. (A) Purification of the NAK complex by MonoQ ion exchange chromatography. Nef complexes were isolated from Jurkat cells expressing the hybrid CN using the MonoQ column. Anti-CD8 immunoprecipitations from different fractions were examined for NAK activity (IVKA) and for the presence of Nef and PAK1 (Western blot). (B) Nef from HIV interacts with PAK1 in COS cells. The hybrid CN (left panel), hybrid Nef.GFP (right panel, + in table), CD8 truncated proteins or GFP alone (− in table) were coexpressed with PAK1 in COS cells. Cellular lysates were incubated with the anti-N20 (right panel, IP:αPAK1) or the anti-CD8 antibody (left panel, IP:αCD8), and immunoprecipitations were analyzed by Western blotting by using anti-Nef (lanes 3 and 4) or anti-N20 (lanes 1 and 2) antibodies, respectively (upper panel, IP). Western blotting of input Nef and PAK1 proteins prior to the immunoprecipitation are presented in the bottom panel (input). (C) Nef binds to PAK1 in vitro. Nef and the mutant NefRR-LL protein were purified from insect cells by using baculovirus, were incubated with the hybrid GST-PAK1 protein or GST alone, and were passed over glutathione beads. The bound Nef was analyzed by Western blotting by using the anti-Nef antibody (Western blot). Nef proteins (10% of that used in the binding reaction) were loaded on the gel as input control (10% input).

Nef interacts with PAK1 in cells.

Since NAK was identified initially as a kinase activity which coimmunoprecipitates with Nef, we wanted to confirm that Nef and PAK1 can interact in cells. The hybrid CN and PAK1 were coexpressed in COS cells. Nef was immunoprecipitated with the anti-CD8 antibody, and these immunoprecipitations were assayed for the presence of PAK1 by Western blotting with the N20 antibody (Fig. 1B, left panel). In these experiments, PAK1 could be detected readily in anti-CD8 immunoprecipitations from cells expressing the hybrid CN (Fig. 1B, lane 2) but not from cells expressing the truncated CD8 protein (Fig. 1B, lane 1). To demonstrate that artificial membrane targeting of Nef via CD8 is not a prerequisite for this association between Nef and PAK1, we performed reciprocal immunoprecipitations from cells expressing the hybrid Nef.GFP protein or GFP alone with the anti-N20 antibody. Similar to our previous results with the hybrid CN, the hybrid Nef.GFP protein but not GFP alone associated with PAK1 in cells (Fig. 1B, right panel, lanes 3 and 4). We conclude that Nef interacts with PAK1 in vivo.

Nef binds to PAK1 in vitro.

Next, we investigated if PAK1 binds to Nef in vitro. Nef was purified from insect cells infected with baculovirus and incubated with GST or hybrid GST-PAK1 proteins. As judged by Coomassie blue and silver staining, no contaminating proteins were copurified with Nef from insect cells (data not shown). The presence of Nef in these GST pull down assays was analyzed by Western blotting. As presented in Fig. 1C, no interaction with Nef was observed with GST alone (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 3). In contrast, the hybrid GST-PAK1 protein bound to Nef but not to the mutant NefRR-LL protein (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 4) and captured about 10% of the input Nef (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 2 and 5). We conclude that Nef binds to PAK1 and that the RR-LL mutation at positions 109 to 110 in Nef abolishes this interaction.

NAK is blocked by an inhibitory fragment from PAK1.

To demonstrate functionally that NAK is PAK1, we examined the ability of an inhibitory fragment of PAK1 to block NAK in cells. To this end, we assayed NAK in the presence of a peptide containing residues 83 to 149 of PAK1 (PAK1 83-149). PAK1 83-149 has been demonstrated to inhibit the autophosphorylation of PAK1 by blocking a critical phosphoacceptor site that is required for its kinase activity and does not bind to Cdc42 nor interfere with the binding of small GTPases to PAK1 (13, 47, 48). Moreover, these sequences C terminal to the CRIB domain in PAK1 are not highly conserved among PAK family members (Fig. 2A).

Increasing amounts of the plasmid vector or PAK1 83-149 were coexpressed with the hybrid CD8-Nef protein in Jurkat cells, and anti-CD8 immunoprecipitations were then tested for NAK activity. Similar experiments had previously demonstrated that NAK activity depends on the presence of Rac1, Cdc42, and Vav (12, 26). When compared to the activity of NAK from cells transfected with the control plasmid vector (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2), PAK1 83-149 blocked the activity of NAK in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2B, IVKA, lanes 3 and 4). Since similar amounts of Nef were present in all immunoprecipitations (Fig. 2B, Western blot), this result confirms the identity of NAK as PAK1.

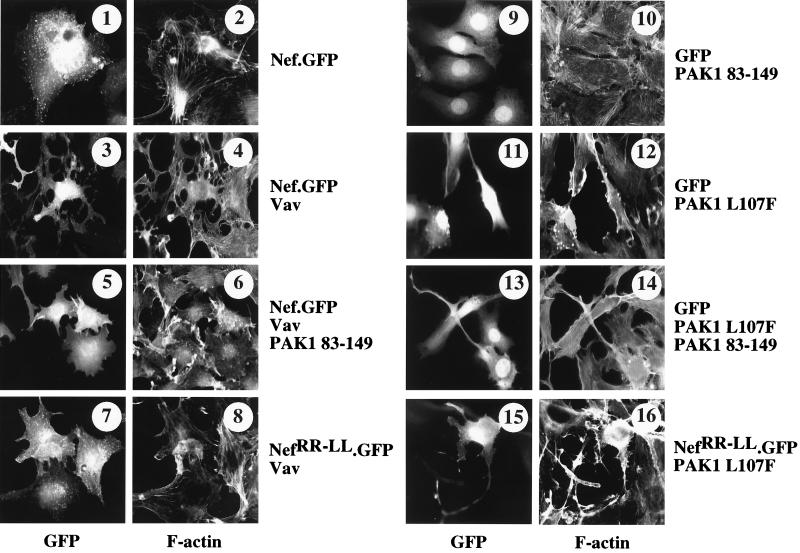

Cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by Nef require the kinase activity of PAK1.

Previously, we demonstrated that the activation of Vav by Nef results in cytoskeletal rearrangements and the activation of the JNK–stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) cascade (12). Since a mutant Vav protein lacking the GEF activity blocked NAK, we speculated that the downstream effector functions induced by Nef and Vav are a direct consequence of the subsequent activation of PAK1. To prove this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of PAK1 83-149 on cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by Nef.

NIH 3T3 cells were injected with plasmid effectors and were stained with TRITC-phalloidin for polymerized actin. Changes in the actin cytoskeleton were observed to be stable for up to 14 h. Injected cells were localized via the GFP linked to Nef or expressed from a coinjected plasmid (12). Whereas the expression of the hybrid Nef.GFP protein alone had no significant effect on the actin cytoskeleton, the coexpression of Nef and Vav led to a dramatic loss of actin stress fibers and the generation of long extentions called trichopodia (Fig. 3, compare panels 1 and 2 with panels 3 and 4). In sharp contrast, when the kinase activity of PAK1 was inhibited by the coexpression of PAK1 83-149, Nef and Vav no longer disrupted actin stress fibers and could not form trichopodia. Only the formation of membrane ruffles and small lamellipodia was observed (Fig. 3, compare panels 3 and 4 with panels 5 and 6). The coexpression of Vav with the mutant hybrid NefRR-LL.GFP protein, which cannot bind and activate PAK1, resulted in the same phenotype (Fig. 3, panels 7 and 8). Importantly, the microinjection of PAK1 83-149 alone had no effect (Fig. 3, panels 9 and 10). These results demonstrate that the induction of the kinase activity of PAK1 by Nef is critical for the disruption of actin stress fibers and for the formation of trichopodia and that residual morphological changes occur independently of the kinase activity of PAK1. These latter effects most likely represent direct effects of activated Rac1 (18, 44). Moreover, cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by Nef, Vav, and PAK1 were more pronounced then the loss of actin stress fibers and the cytoplasmatic retractions induced by the constitutively active PAK1 (PAK1 L107F) (Fig. 3, compare panels 3 and 4 with panels 11 and 12) (13, 48)). As described previously (12), the formation of trichopodia represents a different process from cytoplasmic retractions induced by the constitutively active PAK1. Highlighting these differences, effects of PAK1 L107F were also not sensitive to the coexpression of PAK1 83-149 (Fig. 3, panels 13 and 14). Additionally, since the mutant hybrid NefRR-LL.GFP protein had no effect on PAK1 L107F (Fig. 3, panels 15 and 16), PAK1 must function downstream of Vav in this pathway. This conclusion was confirmed by identical results observed with the mutant hybrid NefPP-AA.GFP protein, which cannot activate Vav (data not shown). We conclude that the activation of PAK1 by Nef is critical for the disruption of actin stress fibers and the formation of trichopodia induced by Nef and Vav and that membrane ruffles and lamellipodia induced by Nef independently of the kinase activity of PAK1 synergize with this effect.

FIG. 3.

Blocking PAK1 activity prevents cytoskeletal rearrangements induced by Nef and Vav. NIH 3T3 cells were maintained in a low concentration of serum (0.1% FCS-Dulbecco modified Eagle medium) and were microinjected with indicated plasmids (10 μg of each per ml). Cells were fixed for 3 h and were stained with TRITC-phalloidin (right-hand panels) to visualize polymerized actin (see Materials and Methods). Trichopodia refer to extensions bearing minute filopodia (panels 3 and 4). Microinjected cells were identified by the expression of GFP (left-hand panels). Proteins expressed from injected plasmids are indicated to the right of panels 1 to 16.

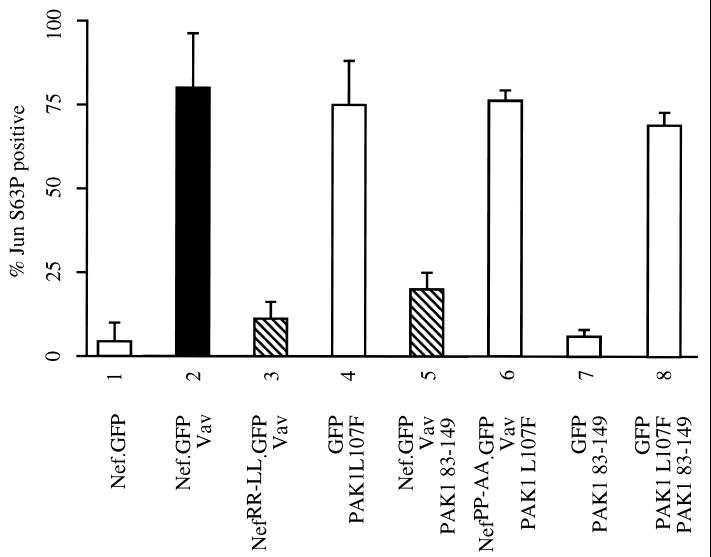

The kinase activity of PAK1 is required for the activation of the JNK-SAPK cascade by Nef.

Next, we investigated whether the activation of the JNK-SAPK cascade by Vav and Nef is also mediated by PAK1. To this end, we monitored the phosphorylation of the serine at position 63 in Jun in microinjected NIH 3T3 cells (3). Vav, the hybrid Nef.GFP or mutant hybrid NefRR-LL.GFP proteins, and PAK1 L107F or PAK1 83-149 were coexpressed with the N terminus of c-Jun (NLex.JunN [33]). Injected cells were stained with the antibody that recognizes only the phosphorylated JunS63. The coexpression of the hybrid Nef.GFP protein and Vav but not the expression of the hybrid Nef.GFP protein alone resulted in the phosphorylation of JunS63 in injected cells (Fig. 4, compare columns 1 and 2). This activation of JNK was similar to that observed with the activated PAK1 (Fig. 4, column 4). However, no activation of JNK was observed when the mutant NefRR-LL.GFP protein was coexpressed with Vav or when PAK1 83-149 was coexpressed with Vav and the hybrid Nef.GFP protein (Fig. 4, columns 3 and 5). Moreover, the expression of the PAK1 83-149 peptide alone did not affect the activity of JNK (Fig. 4, column 7). Similar to its inability to change the actin cytoskeleton, the expression of the mutant NefPP-AA.GFP protein that does not activate Vav and PAK1 also did not block the activation of JNK by PAK1 L107F (Fig. 4, column 6). Likewise, the PAK1 83-149 peptide did not inhibit the activation of JNK by PAK1 L107F (Fig. 4, column 8). These data suggest that the activation of PAK1 by Nef induces JNK. We conclude that the kinase activity of PAK1 is required for the formation of trichopodia and the induction of the JNK-SAPK cascade by Nef.

FIG. 4.

Blocking PAK1 activity prevents the activation of the JNK-SAPK cascade by Nef and Vav. NIH 3T3 cells were maintained in a low concentration of serum and were microinjected as described in the legend to Fig. 3 except for the addition of a plasmid coding for the hybrid LexJun protein. Cells were stained with the anti-JunS63P antibody, and stained cells were counted. Expressed proteins are denoted on the bottom of the figure. Whereas the effects of Nef without activation of Pak1 are represented by striped bars, controls for the activity of Nef and Vav as well as Pak1 are shown in black and white, respectively. Standard errors of the means are presented with error bars. Experiments are representative of three independent injections where more than 50 cells were counted.

The inhibition of viral replication by PAK1 83-149 depends on Nef.

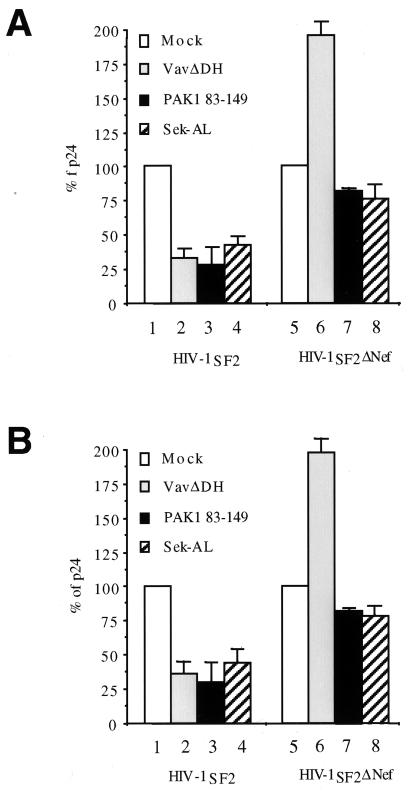

Previously, we reported that the inhibition of NAK by a dominant negative PAK protein (PAK-R) (26) or a mutant Vav protein lacking the GEF activity (VavΔDH) (12) blocked the production of HIV-1. Since the coexpression of the PAK1 83-149 peptide prevented the activation of PAK1 by Nef, we examined its effects on viral replication. A plasmid containing the HIV-1SF2 provirus was coexpressed with the empty plasmid vector (Fig. 5, white bars) or with the PAK1 83-149 peptide (Fig. 5, black bars) in Jurkat cells. The production of viral particles was monitored by measuring levels of p24Gag in the supernatant of transfected cells (Fig. 5A). As observed with the mutant VavΔDH protein (Fig. 5, grey bars), the expression of the PAK1 83-149 peptide resulted in 80% decreased production of new virions (Fig. 5A, compare columns 1, 2, and 3). However, neither the mutant VavΔDH protein nor the PAK1 83-149 peptide had a significant effect on the production of HIV-1SF2 from the provirus that lacked the nef gene (Fig. 5A, compare columns 5, 6, and 7). Since the dominant negative Sek-AL protein (striped bars) had a similar negative effect on viral production (Fig. 5, columns 4 and 8), these effects were mediated by the activation of JNK by Nef. These results demonstrate that the inhibition of PAK1 is sufficient to block the effect of Nef on viral production.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of PAK1 activity interferes with viral production. The PAK1 83-149 peptide as well as mutant VavΔDH and Sek-AL proteins inhibit viral production only from proviruses that contain the nef gene. HIV-1SF2 provirus or its counterpart, which lacked the nef gene (HIV-1SF2ΔNef), was coexpressed in Jurkat cells with the empty plasmid vector (Mock), the mutant VavΔDH protein, the dominant negative Sek-AL protein, or the PAK1 83-149 peptide. The production of HIV-1 particles was measured after 48 h by quantifying levels of p24Gag in the supernatant (A). The overall synthesis of viral proteins was quantified by combining intra- and extracellular levels of p24Gag (B). Mock transfections were arbitrarily set to 100%. Averages of triplicate experiments with indicated standard errors of the means are shown.

To determine if these effects of Nef reflected increased transcription from the viral long terminal repeats, the overall synthesis of viral proteins (intracellular p24Gag and p24Gag in the supernatant) was determined (Fig. 5B). Results mirrored the data for p24Gag in the supernatant of transfected cells. The PAK1 83-149 peptide, mutant VavΔDH, and Sek-AL proteins all significantly reduced the overall synthesis of viral proteins from the wild-type HIV-1 but not from the provirus that lacked the nef gene. We conclude that the major effect of Nef on viral production is mediated by increased viral gene expression in Jurkat cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to identify NAK as a specific PAK family member, which is activated by Nef to increase the pathogenicity of primate lentiviruses. PAK1 was found in Nef complexes and was coimmunoprecipitated with Nef in cells. Furthermore, Nef bound to PAK1 in vitro. The inhibitory PAK1 83-149 peptide that prevents the autophosphorylation of PAK1 blocked not only NAK but also the disruption of actin stress fibers, the formation of trichopodia, the induction of the JNK-SAPK cascade, and the production of viruses. We conclude that PAK1 can provide the kinase activity of NAK, which is required for the downstream effector functions of Nef.

The identification of NAK as PAK1 is based on structural and functional criteria. In our immunoprecipitations and Western blots, the anti-N20 antibody was able to recognize PAK1 with a 100-fold-higher affinity than PAK2. This specificity was confirmed by microsequencing of proteins in complexes from Jurkat cells, which were immunoprecipitated with the anti-N20 antibody, and by the inability of this antibody to recognize overexpressed PAK2, PAK3, or PAK4 in COS cells. Furthermore, we could not detect the association of the hybrid CN with any PAK isoform other than PAK1 in cells (data not shown). Additionally, PAK1 bound to Nef in GST pull down assays. Our functional studies also argue for PAK1. Nevertheless, although the PAK1 83-149 peptide contains sequences that are not highly conserved among PAK isoforms, its specificity was examined only with PAK1 and PAK3, where it most efficiently inhibited PAK1 (13, 48).

Thus, it is possible that PAK1 83-149 also inhibits PAK2. To this end, it is of interest that after the submission of our report, another group using a different allele of Nef identified NAK as PAK2 (34). This study was based exclusively on an epitope-specific antibody against PAK2 and presented no functional data. However, taken together, these two reports might resolve the dilemma of NAK. Previous conflicting tryptic peptide maps of NAK could not differentiate between these two PAK isoforms. For example, peptide patterns resembling those of PAK1 and PAK2 were presented for NAK associated with Nef from SIVmac239 (40) and HIV-1NL4-3, respectively (34). However, for Nef from HIV-1SF2, the peptide pattern of NAK did not resemble that of PAK2 (26). Since both PAK1 and PAK2 have now been identified as NAK by improved binding assays and the use of epitope-specific antibodies, it is possible that different alleles of Nef bind preferentially to one or the other PAK isoform. Alternatively, this specificity could be influenced by levels of expression, subcellular distribution, and context of these PAK family members in different cells. However, since PAK1 and PAK2 are 78% identical, share 91% amino acid homology, and have interchangeable effects on the actin cytoskeleton and signaling cascades (23), the choice of either partner serves the need of the virus. Thus, the search for the precise PAK isoform has instead discovered its pathway and phenotype.

PAK1 and PAK2 (henceforth PAK1) exert profound effects on the actin cytoskeleton and downstream signaling cascades. The extensive disruption of actin stress fibers, cytoplasmic retraction, and JNK activation require the kinase activity of PAK1. In sharp contrast, the induction of membrane ruffles and small lamellipodia depends on Rac1 but is kinase independent (18, 44). The same picture was observed with Nef. The loss of stress fibers and the formation of trichopodia depended on Nef, Vav, and PAK1. However, the formation of membrane ruffles and small lamellipodia was still observed in the presence of the PAK1 83-149 peptide or with the mutant NefRR-LL protein, which does not bind to PAK1. In both cases, Nef could still activate Rac1. As discussed previously, trichopodia differ from cytoplasmic retractions and most likely represent the local activation of actin reorganization by Nef complexes, which are localized in tiny vesicles in these extensions (9, 12). These 1-mDa complexes most likely form in lipid rafts (6, 11, 29, 46) and contain additional signaling intermediates, e.g., Src family kinases that bind to the N terminus of Nef. Indeed, this NAK-C complex, which contains Lck and additional unknown proteins, is required for the activation of NAK (5).

On the molecular level, both the proline-rich motif and diarginine residues in Nef are required for the activation of PAK1 in vitro and for the pathogenesis of SIV in vivo (20, 28, 39, 40). Their location allows for the simultaneous binding of Vav and PAK1 to two distinct surfaces on Nef (28). This organization of the Nef complex is in agreement with a study on the activation of the PAK homologue Ste20 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where Nef bound to Bem1 and Ste20 via the proline-rich motif and the diarginine residues, respectively (32). However, whereas Bem1 stabilized and activated the Nef-Ste20 complex in yeast, Vav does not contribute to the binding of Nef to PAK1 in mammalian cells (data not shown). Rather, Nef, Rac1, and Cdc42 are localized at the plasma membrane by their N-terminal myristyl and C-terminal geranyl moieties, respectively. This localization enables the interaction of Nef with the C-terminal SH3 domain of Vav which induces its GEF activity for Cdc42 and Rac1. PAK1 is recruited into this complex by the diarginine residues in Nef. The activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 leads to their subsequent dissociation from Vav and strongly increases their affinity for PAK1 (13, 36). They bind to the CRIB domain of PAK1 and activate the kinase. The subsequent induction of cytoskeletal rearrangements and activation of the JNK-SAPK cascade then results in increased production and infectivity of HIV. With the identification of key players in this process, future studies will focus on antiviral strategies specifically directed against these signaling events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Armanini for expert secretarial assistance and Pierre Chardin, Melanie Cobb, Cecilia Cheng-Mayer, Paul Luciw, Frank McCormick, Pablo Rodriguez-Viciana, Ran Taube, and Art Weiss for reagents and comments on experiments.

O.T.F. and M.G. kindly acknowledge fellowships from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the European Molecular Biology Organisation, respectively. This work was funded by grants from the NIH (1RO1AI38532-01 and GM53032) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abo A, Qu J, Cammarano M S, Dan C, Fritsch A, Baud V, Belisle B, Minden A. PAK4, a novel effector for Cdc42Hs, is implicated in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and in the formation of filopodia. EMBO J. 1998;17:6527–6540. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C, Trono D. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J Virol. 1995;69:5048–5056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5048-5056.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberts A S, Treisman R. Activation of RhoA and SAPK/JNK signaling pathways by the RhoA-specific exchange factor mNET1. EMBO J. 1998;17:4075–4085. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.14.4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur A S, Sawai E T, Dazin P, Fantl W J, Cheng-Mayer C, Peterlin B M. HIV-1 Nef leads to inhibition or activation of T cells depending on its intracellular localization. Immunity. 1994;1:373–384. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baur A S, Sass G, Laffert B, Willbold D, Cheng-Mayer C, Peterlin B M. The N-terminus of Nef from HIV-1/SIV associates with a protein complex containing Lck and a serine kinase. Immunity. 1997;6:283–291. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown D A, London E. Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:111–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowers M Y, Pandori M W, Spina C A, Richman D D, Guatelli J C. The growth advantage conferred by HIV-1 nef is determined at the level of viral DNA formation and is independent of CD4 downregulation. Virology. 1995;212:451–457. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespo P, Schuebel K E, Ostrom A A, Gutkind J S, Bustelo X R. Phosphotyrosine-dependent activation of Rac-1 GDP/GTP exchange by the vav proto-oncogene product. Nature. 1997;385:169–172. doi: 10.1038/385169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels R H, Hall P S, Bokoch G M. Membrane targeting of p21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) induces neurite outgrowth from PC12 cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:754–764. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.3.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C, Lawson V A, Crowe S, Maerz A, Sonza S, Learmont J, Sullivan J S, Cunningham A D D, Dowton D, Mills J. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fackler O T, Kienzle N, Kremmer E, Boese A, Schramm B, Klimkait T, Kucherer C, Mueller-Lantzsch N. Association of human immunodeficiency virus Nef protein with actin is myristoylation dependent and influences its subcellular localization. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:843–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fackler O T, Luo W, Geyer M, Alberts A S, Peterlin B M. Activation of Vav by Nef induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions. Mol Cell. 1999;3:729–739. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frost J A, Khokhlatchev A, Stippec S, White M A, Cobb M H. Differential effects of PAK1-activating mutations reveal activity-dependent and -independent effects on cytoskeletal regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28191–28198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia J V, Miller A D. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature. 1991;350:508–511. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Sutcliffe M J, Cerione R A, Oswald R E. Identification of the binding surface on Cdc42Hs for p21-activated kinase. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14030–14037. doi: 10.1021/bi981352+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J, Das B, Wei W, Van Aelst L, Mosteller R D, Khosravi-Far R, Westwick J K, Der C J, Broek D. Lck regulates Vav activation of members of the Rho family of GTPases. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1346–1353. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jamieson B D, Aldrovandi G M, Planelles V, Jowett J B, Gao L, Bloch L M, Chen I S, Zack J A. Requirement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef for in vivo replication and pathogenicity. J Virol. 1994;68:3478–3485. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3478-3485.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joneson T, McDonough M, Bar-Sagi D, Van Aelst L. RAC regulation of actin polymerization and proliferation by a pathway distinct from Jun kinase. Science. 1996;274:1374–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kestler H W, III, Ringler D J, Mori K, Panicali D L, Sehgal P K, Daniel M D, Desrosiers R C. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for development of AIDS. Cell. 1991;65:651–662. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90097-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan I H, Sawai E T, Antonio E, Weber C J, Mandell C P, Montbriand P, Luciw P A. Role of the putative SH3-ligand domain of simian immunodeficiency virus Nef in interaction with Nef-associated kinase and simain AIDS in rhesus macaques. J Virol. 1998;72:5820–5830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5820-5830.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King A J, Sun H, Diaz B, Barnard D, Miao W, Bagrodia S, Marshall M S. The protein kinase PAK3 positively regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine 338. Nature. 1998;396:180–183. doi: 10.1038/24184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhoff F, Greenough T C, Brettler D B, Sullivan J L, Desrosiers R C. Brief report: absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knaus U G, Bokoch G M. The p21Rac/Cdc42-activated kinases (PAKs) Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:857–862. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee C H, Saksela K, Mirza U A, Chait B T, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the conserved core of HIV-1 Nef complexed with a Src family SH3 domain. Cell. 1996;85:931–942. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Gall S, Erdtmann L, Benichou S, Berlioz-Torrent C, Liu L, Benarous R, Heard J M, Schwartz O. Nef interacts with the mu subunit of clathrin adaptor complexes and reveals a cryptic sorting signal in MHC I molecules. Immunity. 1998;8:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu X, Wu X, Plemenitas A, Yu H, Sawai E T, Abo A, Peterlin B M. CDC42 and Rac1 are implicated in the activation of the Nef-associated kinase and replication of HIV-1. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1677–1684. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70792-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu X, Yu H, Liu S H, Brodsky F M, Peterlin B M. Interactions between HIV-1 Nef and vacuolar ATPase facilitate the internalization of CD4. Immunity. 1998;8:647–656. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80569-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manninen A, Hiipakka M, Vihinen M, Lu W, Mayer B J, Saksela K. SH3-domain binding function of HIV-1 Nef is required for association with a PAK-related kinase. Virology. 1998;250:273–282. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederman T M, Hastings W R, Ratner L. Myristoylation-enhanced binding of the HIV-1 Nef protein to T cell skeletal matrix. Virology. 1993;197:420–425. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunn M F, Marsh J W. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a member of the p21-activated kinase family. J Virol. 1996;70:6157–6161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6157-6161.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piguet V, Chen Y L, Mangasarian A, Foti M, Carpentier J L, Trono D. Mechanism of Nef-induced CD4 endocytosis: Nef connects CD4 with the mu chain of adaptor complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2472–2481. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plemenitas A, Lu X, Geyer M, Veranic P, Simon M-N, Peterlin B M. Activation of Ste20 by Nef from human immunodeficiency virus induces cytoskeletal rearrangements and downstream effector functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Virology. 1999;258:271–281. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Price M A, Cruzalegui F H, Treisman R. The p38 and ERK MAP kinase pathways cooperate to activate ternary complex factors and c-fos transcription in response to UV light. EMBO J. 1996;15:6552–6563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renkema G H, Manninen A, Mann D A, Harris M, Saksela K. Identification of the Nef-associated kinase as p21-activated kinase 2. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1407–1410. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)80086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudel T, Bokoch G M. Membrane and morphological changes in apoptotic cells regulated by caspase-mediated activation of PAK2. Science. 1997;276:1571–1574. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5318.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rudolph M G, Bayer P, Abo A, Kuhlmann J, Vetter I R, Wittinghofer A. The Cdc42/Rac interactive binding region motif of the Wiskott Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP) is necessary but not sufficient for tight binding to Cdc42 and structure formation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18067–18076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saksela K, Cheng G, Baltimore D. Proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in HIV-1 Nef bind to SH3 domains of a subset of Src kinases and are required for the enhanced growth of Nef+ viruses but not for down-regulation of CD4. EMBO J. 1995;14:484–491. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawai E T, Baur A, Struble H, Peterlin B M, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1539–1543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawai E T, Baur A S, Peterlin B M, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. A conserved domain and membrane targeting of Nef from HIV and SIV are required for association with a cellular serine kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15307–15314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawai E T, Khan I H, Montbriand P M, Peterlin B M, Cheng-Mayer C, Luciw P A. Activation of PAK by HIV and SIV Nef: importance for AIDS in rhesus macaques. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(96)00757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Danos O, Heard J M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef increases the efficiency of reverse transcription in the infected cell. J Virol. 1995;69:4053–4059. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4053-4059.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard J M. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med. 1996;2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sells M A, Chernoff J. Emerging from the PAK: the p12-activated protein kinase family. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:162–167. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)01003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westwick J K, Lambert Q T, Clark G J, Symons M, van Aelst L, Pestell R G, Der C J. Rac regulation of transformation, gene expression, and actin organization by multiple, PAK-independent pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1324–1335. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiskerchen M, Cheng-Mayer C. HIV-1 Nef association with cellular serine kinase correlates with enhanced virion infectivity and efficient proviral DNA synthesis. Virology. 1996;224:292–301. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Membrane compartmentation is required for efficient T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;8:723–732. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zenke F T, King C C, Bohl B P, Bokoch G M. Identification of a central phosphorylation site in p21-activated kinase regulating autoinhibition and kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32565–32573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Z S, Manser E, Chen X Q, Chong C, Leung T, Lim L. A conserved negative regulatory region in αPAK: inhibition of PAK kinases reveals their morphological roles downstream of Cdc42 and Rac1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2153–2163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]