Abstract

Varicella zoster and herpes zoster (HZ) are infections caused by the highly contagious varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Despite widespread availability of vaccines against VZV, as well as varicella vaccination rates >95%, VZV remains a public health concern due to several common myths and misconceptions. Because of the success of routine varicella vaccination programs, some people mistakenly believe that varicella and HZ are now no longer a threat to public health. Another common misconception is that shingles is less infectious than varicella; however, clinical evidence demonstrates otherwise. Several knowledge gaps exist around VZV transmission and the availability and use of VARIZIG (varicella zoster immune globulin [human]) for postexposure prophylaxis against VZV. To help reduce the incidence of severe disease in high-risk individuals (eg, elderly, pregnant women, unvaccinated persons, infants, and immunocompromised children and adults), this article addresses misbeliefs and broadens awareness of VZV exposure, infection risks, complications, and treatments.

Keywords: Varicella, herpes zoster, Public health, Postexposure prophylaxis

INTRODUCTION

Varicella zoster (ie, chickenpox) is an acute infection caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV). VZV is a member of the alphaherpesviruses, a group of double-stranded DNA viruses that lead to human infection and latency in dorsal root ganglia.1 Primary varicella infection (PV) is thought to occur through contact with respiratory secretions from a person with active varicella or from direct contact with varicella vesicular lesions.2 Despite an observed 10- to 21-day incubation period from infection to clinical symptoms, the host is contagious and can spread VZV through the respiratory route 24 to 48 hours preceding initial skin eruption.3

Those infected with PV may experience prodromal symptoms prior to the classic varicella vesicular rash.4 While the primary eruption is uncomfortable, PV can lead to major complications that cause morbidity and mortality, including bacterial superinfections progressing to necrotizing fasciitis, central nervous system diseases (eg, cerebellar ataxia, meningoencephalitis, and Guillain-Barre syndrome), pneumonitis, and death.2 PV is more severe among high-risk populations, such as older adolescents and adults, pregnant women, neonates, unvaccinated and previously unexposed persons, and individuals with impaired cellular immunity (eg, those with leukemia). Prior to the implementation of VZV vaccination programs, 100 VZV-related deaths were reported annually in the United States, mostly in previously healthy children.5

As the host ages and innate immunity wanes, VZV can reactivate from latency, causing herpes zoster (HZ; ie, shingles). HZ differs from PV in that it is often a localized infection, and preceded by pain, hyperesthesia, or pruritus in the location where vesicles will soon erupt.5 New lesions occur on average for up to 7 days, and the infection can be spread through multiple routes (detailed below).5 The risk of developing HZ after PV infection increases after age 50.3 More than 95% of immunocompetent individuals aged 50 years and older are seropositive for VZV and, therefore, are at risk for developing HZ (if not vaccinated). Reactivation can also occur in those with impaired cellular immunity, including those with leukemia, and those who have undergone solid organ transplant and stem cell transplant.1 These populations are at increased risk for disseminated HZ and further morbidity and mortality from the disease.5

There are safe and effective vaccines to prevent varicella and HZ. The United States first licensed the varicella vaccine (Varivax®; Merck & Co, Inc., North Wales, PA, USA) for all healthy children aged 1 year and older in 1995, and initial studies showed that one dose provided children with 85% protection from contracting primary disease.6 In 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended a second dose to children older than 4 years of age, which increased protection up to 95% in postvaccine studies.5 Currently, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends a two-dose vaccination series to all immunocompetent children, starting at 1 year of age.7 Unfortunately, immunization does not prevent disease in individuals already exposed to VZV. There are also 2 vaccines approved for adults aged 50 years and older to reduce the risk of HZ (Zostavax®, Merck & Co, Inc., North Wales, PA, USA; and Shingrix®, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rockville, MD, USA). Fortunately, there are viable treatment options for those that develop PV/HZ, those ineligible to receive vaccines, and individuals at high-risk for complications after exposure to VZV. Passive immunization, with anti-VZV immunoglobulin medications like VARIZIG® (varicella zoster immune globulin [human]; Saol Therapeutics, Roswell, GA, USA) can prevent PV or reduce the severity of disease if given in a timely manner.8 The decision to use medications like VARIZIG depends on multiple factors, including the type of exposure, the risk of severe disease, and the exposed person’s own immunity to VZV.3 In individuals with decreased T-cell immunity, passive immunization is recommended to prevent either primary disease or to decrease severity of disease.3 VARIZIG is most efficacious if given within 96 hours after exposure, but it can be administered up to 10 days postexposure.9 Acyclovir therapy has become a mainstay in high-risk populations to prevent disease progression and more severe complications after disease onset.5 While acyclovir is not recommended for postexposure prophylaxis in otherwise healthy children, acyclovir does reduce the risk of reactivation in previously exposed people with depressed T-cell function.3 Prevention of PV can also be achieved through isolation of infected individuals.7

Despite the availability of varicella vaccines and the fact that varicella vaccination rates are >95%, infection with VZV varicella and HZ remains a public health concern. There are several common myths and misconceptions that serve to undermine the most effective VZV prevention measures from being used.

MYTH 1: THE RISK OF EXPOSURE TO VARICELLA OR HZ IS LOW BECAUSE OF VACCINATION

Because of the success of widespread routine VZV vaccination programs, some people believe that varicella and HZ are now no longer public health issues.

Facts:

Since the implementation of the two-dose varicella vaccination program, the average annual incidence of varicella has decreased by 85%, from 25.4 per 100,000 during 2005–2006 to 3.9 per 100,000 during 2013–2014 (p<0.001).6 However, in the United States alone, approximately 100,000 cases of varicella and nearly 1 million new cases of HZ still occur each year.6, 10 Further, the incidence of HZ increased by 98% over 13 years, from 1.7 per 1000 individuals in 1993 to 4.4 per 1000 in 2006 (p<0.001).11 Nearly one in three people in the United States will develop HZ in their lifetime10, and the risk of getting HZ increases with age.12 Unfortunately, 2017 data from the CDC indicate that only 40% of adults aged 60 years and older have received one of the HZ vaccines.13

Despite a high rate of >95% two-dose varicella vaccination uptake, breakthrough varicella disease, defined as VZV infection occurring >42 days after varicella vaccination14, still occurs.15–18 Among children who receive one- or two-dose vaccine regimens, breakthrough varicella rates range from 2.2%–7.3%, respectively.7 Rates of breakthrough varicella are significantly higher in North America compared with Asia and Europe (p=0.005).16 Typically, breakthrough varicella disease is relatively mild (ie, shorter duration and fewer lesions), though still contagious to susceptible individuals.14 However, 25%–30% of breakthrough varicella has resulted in severe disease with complications similar to those in unvaccinated individuals.19,7

Medical and nonmedical vaccination exemption rates are increasing nationwide. According to the CDC, the number of kindergartners with medical and nonmedical exemptions (NMEs) from ≥1 required vaccine (including varicella vaccines) increased from 2.0% during the 2016–2017 school year to 2.2% in 2017–2018.20 An overall increase in exemptions has been observed for the last 3 consecutive years.20, 21 In a birth cohort of approximately 3 million, this increase translates to 6000 children per year, or an increase of almost 20,000 exemptions over the 3 years. From 2009–2017, the number of NMEs from vaccination significantly increased in 12 of the 18 states that grant NMEs (p< 0.05). NMEs were also heterogeneously distributed within individual states, leading to concentrated areas of high NME rates in select counties and metropolitan areas across the country, resulting in hotspots of unvaccinated individuals susceptible to preventable infection.22 Similarly, results from a retrospective cohort analysis of children born between 2000 and 2009 within Kaiser Permanente of Northern California primary care indicated that underimmunization with varicella vaccines and vaccine refusal clustered in geographically similar areas.23 Data from a case-controlled study of children aged 12 months to 8 years showed varicella vaccine refusal significantly increased risk of varicella infection that required medical care (p=0.004).24

Using data from the 2013 National Health Interview Survey, researchers estimated that in the United States, 2.7% of the population was immunosuppressed, and the prevalence of immunosuppression may be increasing due to new immunosuppressive treatment indications and increased life-expectancy.25 Old age and immunosuppression are risk factors for complications due to varicella; therefore, as more immunosuppressive medications become available, the number of susceptible individuals at risk for severe complications from infection with VZV will likely increase.26

MYTH 2: TRANSMISSION OF VZV VIA HZ ONLY OCCURS THROUGH DIRECT CONTACT AND TRANSMISSION VIA HZ EXPOSURE IS LESS LIKELY THAN THROUGH VARICELLA EXPOSURE

People commonly misbelieve one cannot contract VZV from a person with active HZ if their rash is covered. However, VZV is transmitted from person to person via multiple routes.

Facts:

VZV is highly infectious. According to the CDC, a person infected with PV is contagious beginning 1–2 days prior to rash onset (typically 14 days post-VZV exposure) and continuing until all lesions are scabbed (typically 5 days post rash onset). In 2012, compelling epidemiological data demonstrated that breakthrough varicella in vaccinated children is just as likely to occur after exposure to those with HZ as those with PV: nearly 10% of HZ cases (n=27 of 290 cases) versus 15% of varicella cases (n=205 of 1358) caused exposed individuals to develop breakthrough varicella infection.27, 28 Additional long-term studies are needed to further analyze VZV transmission rates between individuals with varicella and individuals with zoster.

VZV is primarily transmitted via direct contact with varicella or HZ lesions but may also be transmitted via respiratory exposure of aerosolized virus. There are limited data suggesting that VZV aerosolization from HZ occurs, as demonstrated by studies using air samples from rooms of patients with active varicella and patients with active HZ infection.29, 30 Multiple case reports from acute and long-term healthcare facilities have demonstrated VZV transmission from isolated patients with HZ to healthcare workers or other patients/residents without direct contact, suggesting the possibility of aerosolized viral transmission.14, 31, 32 Scratching the lesions may aerosolize the VZV virus and consequently facilitate airborne transmission.14 This suggests VZV can be transmitted from a person with HZ, even if their rash is covered. Further, it has been reported that individuals with covered HZ rashes (eg, on the trunk) have the same probability of transmission as those with uncovered rashes (eg, on the arms or legs): the relative risk of transmission was 1.0 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.8–1.3) and 1.1 (95% CI, 0.8–1.3) when comparing trunk rash with rash on the arms and legs, respectively.27

Nosocomial transmission of VZV between patients, healthcare providers, and visitors can be life threatening, necessitating that isolation protocols exist for prevention.33, 34 Since the widespread implementation of the two-dose varicella vaccination program, reports of nosocomial VZV transmission have become less common in the United States.2 In addition to transmission originating in a hospital, long-term care settings, or other healthcare facilities, household transmission of VZV is also a problem.35 Close indoor contact (ie, in the same room or sharing airspace) by one person with an individual with varicella or HZ increases the risk of the other person contracting VZV, especially in high-risk populations (ie, pregnant women, infants, and immunocompromised people). Typically, contagiousness of breakthrough varicella correlates with lesion number. Vaccinated individuals with fewer than 50 lesions were found to be one-third as contagious as unvaccinated individuals, and vaccinated individuals with more than 50 lesions were found to be just as contagious as unvaccinated individuals.35

MYTH 3: VARICELLA ZOSTER IMMUNE GLOBULIN (VARIZIG) IS DIFFICULT TO OBTAIN SO ANTIVIRALS AND INTRAVENOUS IMMUNOGLOBULIN SHOULD BE USED FOR POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS

According to recent survey data, there are several knowledge gaps among physicians around the availability and use of VARIZIG for postexposure prophylaxis against VZV.

Facts:

For more than 50 years, a previous formulation of varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG) was used to prevent or attenuate clinical varicella and its complications. However, in 2006, VZIG was discontinued and replaced by a new varicella zoster immune globulin (human) formulation, VARIZIG. In 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved VARIZIG for postexposure prophylaxis of VZV in high-risk populations, including immunocompromised persons, newborns of mothers with perinatal and postnatal varicella, premature infants, infants aged 1 year and older, adults without proven seroprotection, and pregnant women.8 Specifically, VARIZIG is for individuals who are exposed to PV or HZ and are unable to be vaccinated against varicella; who lack evidence of seroprotection against VZV; who have a high likelihood of VZV exposure leading to infection; and who are at high-risk for severe disease.2, 9 The CDC and American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend the use of VARIZIG ideally within 96 hours, but VARIZIG can be administered up to 10 days post-VZV exposure.9, 36

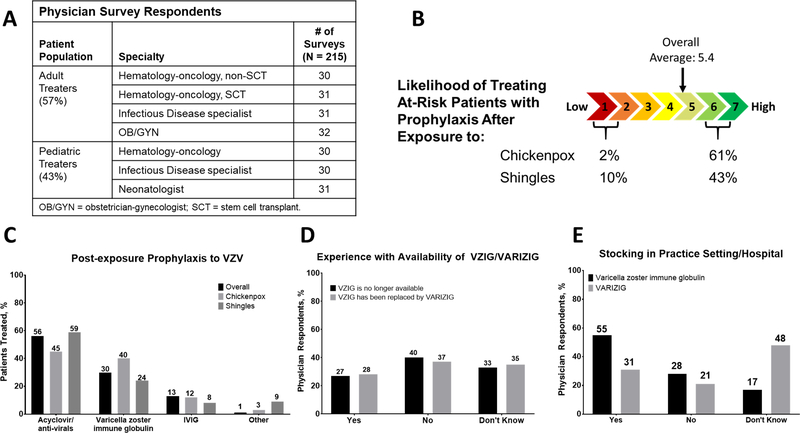

According to a recent survey, most patients are prophylactically treated post-VZV (varicella or HZ) exposure with antivirals (eg, acyclovir) (Fig. 1C). However, there is limited clinical evidence to support the use of antivirals for varicella prophylaxis.37 In some patients, intravenous immunoglobulin was reportedly used as post-exposure prophylaxis to VZV; however, intravenous immunoglobulin titer levels are variable and unreliable for prophylaxis.38 There was confusion regarding VZIG, the first commercial varicella zoster immune globulin preparation available in the United States and VARIZIG. Most physicians surveyed were not aware that VZIG was discontinued and replaced by VARIZIG, and many did not know that VARIZIG was in fact widely distributed and available or stocked in their practice setting (Fig. 1). The CDC website now indicates VARIZIG is widely available from a broad network of specialty distributors in the United States, and can be easily obtained within 24 hours for high-risk patients post-VZV exposure.2

Fig. 1.

Self-administered Internet survey of physicians in full-time clinical practice that see/manage patients at high risk for complications after exposure to VZV. A Physician survey respondent stratification. B Likelihood of treating at-risk patients with prophylaxis after exposure to chickenpox (primary varicella) or shingles (HZ) on a scale of 1 (low likelihood) to 7 (high likelihood). C Prophylaxis post-VZV (varicella/chickenpox or HZ/shingles) exposure. D Physician experience with VZIG/VARIZIG availability. E Physician understanding of varicella zoster immune globulin or VARIZIG stocking in their practice setting or hospital. HZ = herpes zoster; VZV = varicella zoster virus.

DISCUSSION

Varicella and HZ remain global public health issues due in large part to several common myths and misconceptions about VZV exposure risk, transmission, and current treatment options. Addressing these myths and misconceptions is challenging, but important, especially for high-risk populations.

Though national varicella vaccinations rates are high, exposure to varicella or HZ is more common than most people realize. Increased incidence of HZ heightens the risk of exposure for susceptible individuals. VZV transmission occurs through direct contact with varicella or HZ lesions and respiratory exposure to aerosolized virus. Survey data from the CDC has shown that medical and nonmedical vaccination exemption rates are increasing nationwide. Overall, nonmedical exemptions weaken herd or community immunity, placing those who are unable to get vaccinated due to medical reasons (eg, immunocompromised persons due to disease or immunosuppressive therapy) at increased risk for exposure and infection. Additionally, vaccinated individuals still face breakthrough disease due to waning immunity. HZ exposure represents a significant risk, especially in high-risk individuals, and HZ vaccine uptake is low. With increased prevalence of immune-related disorders and new immunosuppressive treatment indications, the incidence of PV following VZV exposure may rise concomitantly.

VARIZIG is the only passive immunization product approved for postexposure prophylaxis of VZV in high-risk individuals without immunity. Administration of VARIZIG is intended to reduce varicella severity. VARIZIG is widely available and easily obtained for high-risk patients post-VZV exposure.2

Increased awareness of the common misconceptions and facts of VZV transmission and the appropriate form of postexposure prophylaxis may help reduce the incidence of severe disease in susceptible individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Saol Therapeutics for support of this manuscript. Medical writing support, funded by Saol Therapeutics, was provided by Caroline Walsh Cazares, PhD, of JB Ashtin, who developed the first draft based on an author-approved outline and assisted in implementing author revisions throughout the editorial process.

Financial Support:

Provided by Saol Therapeutics

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Newman has received funding/grant support from Merck. Dr. Jhaveri has received funding/grant support from AbbVie, Gilead, and Merck, and honorarium for consultancy from MedImmune. He is also an unpaid consultant for Saol. The authors have indicated that they have no other conflicts of interest regarding the content of this article.

Abbreviations:

- ACIP

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- HZ

Herpes zoster

- NMEs

Nonmedical exemptions

- PV

Primary varicella infection

- VZV

Varicella-zoster virus

REFERENCES

- 1.Gershon AA, Breuer J, Cohen JI, et al. Varicella zoster virus infection. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2015;1:15016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chickenpox (Varicella) for Healthcare Professionals. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long SS, Prober CG, Fischer M. Principles and practice of pediatric infectious diseases. Fifth edition. ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller NH, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurologic clinics. 2008;26:675–697, viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherry JD, Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, Hotez PJ, Steinbach WJ. Feigin and Cherry’s textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Eighth edition. ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez AS, Zhang J, Marin M. Epidemiology of Varicella During the 2-Dose Varicella Vaccination Program - United States, 2005–2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2016;65:902–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marin M, Guris D, Chaves SS, et al. Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2007;56:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.VARIZIG Prescribing Information 2018.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated recommendations for use of VariZIG--United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013; 62: 574–576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yawn BP, Saddier P, Wollan PC, St Sauver JL, Kurland MJ, Sy LS. A population-based study of the incidence and complication rates of herpes zoster before zoster vaccine introduction. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2007;82:1341–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung J, Harpaz R, Molinari NA, Jumaan A, Zhou F. Herpes zoster incidence among insured persons in the United States, 1993–2006: evaluation of impact of varicella vaccination. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;52:332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shingles Surveillance: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. adult vaccination coverage general population dashboard. Vol 20192017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopez AS, Marin M. Strategies for the control and investigation of varicella outbreaks manual, 2008. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papaloukas O, Giannouli G, Papaevangelou V. Successes and challenges in varicella vaccine. Therapeutic advances in vaccines. 2014;2:39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu S, Zeng F, Xia L, He H, Zhang J. Incidence rate of breakthrough varicella observed in healthy children after 1 or 2 doses of varicella vaccine: Results from a meta-analysis. American journal of infection control. 2018;46:e1–e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Outbreak of varicella among vaccinated children--Michigan, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004; 53: 389–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tugwell BD, Lee LE, Gillette H, Lorber EM, Hedberg K, Cieslak PR. Chickenpox outbreak in a highly vaccinated school population. Pediatrics. 2004;113:455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung J, Broder KR, Marin M. Severe varicella in persons vaccinated with varicella vaccine (breakthrough varicella): a systematic literature review. Expert review of vaccines. 2017;16:391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellerson JL, Maxwell CB, Knighton CL, Kriss JL, Seither R, Black CL. Vaccination Coverage for Selected Vaccines and Exemption Rates Among Children in Kindergarten - United States, 2017–18 School Year. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018;67:1115–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease SchoolVaxView Interactive!. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, Atlanta, GA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olive JK, Hotez PJ, Damania A, Nolan MS. The state of the antivaccine movement in the United States: A focused examination of nonmedical exemptions in states and counties. PLoS medicine. 2018;15:e1002578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lieu TA, Ray GT, Klein NP, Chung C, Kulldorff M. Geographic clusters in underimmunization and vaccine refusal. Pediatrics. 2015;135:280–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glanz JM, McClure DL, Magid DJ, Daley MF, France EK, Hambidge SJ. Parental refusal of varicella vaccination and the associated risk of varicella infection in children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2010;164:66–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harpaz R, Dahl RM, Dooling KL. Prevalence of Immunosuppression Among US Adults, 2013. Jama. 2016;316:2547–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malaiya R, Patel S, Snowden N, Leventis P. Varicella vaccination in the immunocompromised. Rheumatology. 2015;54:567–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viner K, Perella D, Lopez A, et al. Transmission of varicella zoster virus from individuals with herpes zoster or varicella in school and day care settings. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205:1336–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bloch KC, Johnson JG. Varicella zoster virus transmission in the vaccine era: unmasking the role of herpes zoster. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205:1331–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawyer MH, Chamberlin CJ, Wu YN, Aintablian N, Wallace MR. Detection of varicella-zoster virus DNA in air samples from hospital rooms. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1994;169:91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki K, Yoshikawa T, Tomitaka A, Matsunaga K, Asano Y. Detection of aerosolized varicella-zoster virus DNA in patients with localized herpes zoster. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2004;189:1009–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Josephson A, Gombert ME. Airborne transmission of nosocomial varicella from localized zoster. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1988;158:238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depledge DP, Brown J, Macanovic J, Underhill G, Breuer J. Viral Genome Sequencing Proves Nosocomial Transmission of Fatal Varicella. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;214:1399–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weber DJ, Rutala WA, Hamilton H. Prevention and control of varicella-zoster infections in healthcare facilities. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 1996;17:694–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Advisory Committee on Immunization P, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Immunization of health-care personnel: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011; 60: 1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seward JF, Zhang JX, Maupin TJ, Mascola L, Jumaan AO. Contagiousness of varicella in vaccinated cases: a household contact study. Jama. 2004;292:704–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Academy of Pediatrics. Varicella-zoster infections. in: Pickering LKBC, Kimberlin DW, Long SS Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, IL: 2012: 774–789. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansen JS, Westergren T, Lingaas E. [Post-exposure varicella prophylaxis]. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke. 2011;131:1645–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paryani SG, Arvin AM, Koropchak CM, et al. Comparison of varicella zoster antibody titers in patients given intravenous immune serum globulin or varicella zoster immune globulin. The Journal of pediatrics. 1984;105:200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]