Abstract

Objective

Calculations of disease burden of COVID-19, used to allocate scarce resources, have historically considered only mortality. However, survivors often develop postinfectious ‘long-COVID’ similar to chronic fatigue syndrome; physical sequelae such as heart damage, or both. This paper quantifies relative contributions of acute case fatality, delayed case fatality, and disability to total morbidity per COVID-19 case.

Study Design and Setting

Healthy life years lost per COVID-19 case were computed as the sum of (incidence*disability weight*duration) for death and long-COVID by sex and 10-year age category in three plausible scenarios.

Results

In all models, acute mortality was only a small share of total morbidity. For lifelong moderate symptoms, healthy years lost per COVID-19 case ranged from 0.92 (male in his 30s) to 5.71 (girl under 10) and were 3.5 and 3.6 for the oldest females and males. At higher symptom severities, young people and females bore larger shares of morbidity; if survivors’ later mortality increased, morbidity increased most in young people of both sexes.

Conclusions

Under most conditions most COVID-19 morbidity was in survivors. Future research should investigate incidence, risk factors, and clinical course of long-COVID to elucidate total disease burden, and decisionmakers should allocate scarce resources to minimize total morbidity.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-COV-2, Disability, Disability-adjusted life year, DALY, QALY, Gender, Equity

Graphical Abstract

What is new?

Key findings

-

•

Key Findings: Under most plausible model scenarios, most COVID-19 morbidity (death + disability) is likely to be due to disability (“long-COVID”) or delayed death due to organ damage, rather than immediate death. Only if long-COVID resolves (atypical of postinfectious syndromes) is morbidity higher in old than young.

What this adds to what was known?

-

•

While COVID-19 deaths are numerous, they likely cause less morbidity overall than does disability or organ damage in survivors. Morbidity is highest in females, especially those infected young.

What is the implication and what should change now?

-

•

Scarce resources such as vaccines should be allocated to minimize morbidity rather than focusing solely on mortality. Data on long-COVID, especially its sex bias, should be collected and publicized.

1. Introduction

Calculations of disease burden of COVID-19 are used to allocate scarce resources, and generally focus on death and acute illness which are more common in the elderly [1]; thus older patients are prioritized for interventions such as vaccination. Less attention is paid to ‘long-COVID’ or long-term morbidity which follows COVID-19 infection in 10% of cases, of which 80% are female2: this translates to 16% of females and 4% of males.

Parallels have been drawn between long-COVID and chronic fatigue syndrome, CFS [2]. Post-COVID and CFS are both postinfectious syndromes [3] whose most common symptoms are fatigue, muscle and body aches, and difficulty concentrating [2,4]; they also both tend to strike women. Significantly, although CFS has been known for decades it remains poorly understood and medically neglected [2,5]. Diagnosis, treatment and services are not easily accessible even to severe cases; little specific treatment is available; and research is sparsely funded relative to the disease burden [5]. Much of this also is true for long-COVID, whose prevention should thus be a public health priority.

In addition to CFS-type symptoms, many or most COVID-19 cases have clinical sequelae such as damage to the heart [6] and lungs [][7], even in those whose symptoms were otherwise mild. This damage may increase mortality risk years or decades later, but has not yet been included in calculations of disease burden or even of mortality.

In this paper I establish a plausible range for total morbidity burden per COVID-19 case that is attributable to CFS-type symptoms; to immediate death; and to delayed death. By doing so I inform allocators of scarce resources and suggest avenues for future research.

2. Methods

Disability-adjusted life years (DALY) lost per COVID-19 case were computed in 2021 for the combination of death and long-COVID by sex and age using sex- and age-specific case fatality rates (CFR)1from 2020 and estimated remaining lifespan from the US Social Security Administration [8]. All computations here show DALY lost rather than DALY remaining.

DALY for post-infection sequelae such as long-COVID are computed only among survivors of the initial infection.

Three models were run:

-

•

Model 1 treated long-COVID as CFS, with increased disability but no increase in mortality. DALY were computed for mild, moderate, and severe CFS (disability weights of 0.14, 0.45, and 0.76) [9] and presented in a single chart along with those for death.

-

•

Model 2 also treated long-COVID as CFS, but assumed that symptoms resolved ten years after the initial infection.

-

•

Model 3 ignored CFS-type symptoms entirely but assumed that 10% of COVID-19 survivors sustained damage to heart, lungs, or other vital systems which caused death an average of ten years later

We did not consider long-COVID symptoms which are not also CFS symptoms, such as anosmia, since no published DALY estimates exist for these. However, once these weights become available this issue can be resolved by multiplying together the disability weights

For example, if the disability weight for anosmia was 0.20, and all long-COVID cases had it, the disability weight for mild long-COVID would increase from 0.14 to 0.244.

No ethical approval was needed because this is not human-subjects research.

3. Results

These figures show the breakdown of total DALY lost per COVID-19 case under different scenarios for each sex. In models showing symptoms of varying severity, total DALY lost can be read from the top of the colored bar corresponding to the chosen symptom severity.

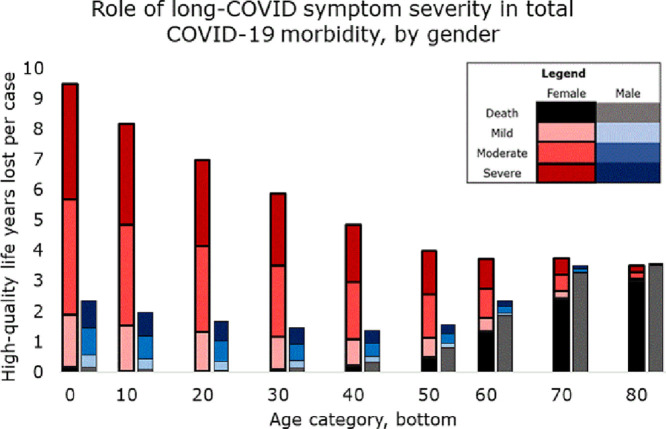

3.1. Model 1: persistent symptoms

If symptoms persisted for life but survivors’ later mortality was not affected (Fig. 1 ), then most morbidity was in female survivors. Female morbidity had a U-shaped association with age, being higher in the young and old (dominated by long-COVID and death, respectively); while male morbidity was J-shaped: dominated by mortality, mostly in the old.

Fig. 1.

The top of each colored bar segment represents average healthy years lost per COVID-19 case in that group for that severity of long-COVID symptoms (mild, moderate, or severe.)

3.1.1. Moderate symptoms

If long-COVID was of moderate severity, each female COVID-19 case under age 10 lost 5.7 DALY, while those over 80 lost 3.3. These can be read from the top of the dark pink bar corresponding to “moderate symptoms, female.” Three percent and 91% of these lost DALY were death, while the remainder was disability. Female morbidity was lowest at 2.56 DALY per case (19% death), at age 50–60. Male morbidity in the youngest was 1.5 DALY per case (12% death) it was 0.92 (15% death) at age 20–30, and 3.6 in the oldest (99% death.)

3.1.2. Mild symptoms

Only if symptoms were mild did the oldest females had higher morbidity than the youngest. Girls under 10 lost 1.9 DALY per case (9% death); this declined to 1.08 (21%) in those between 40 and 50, and rose to 3.1 (97%) in the oldest. Male morbidity did not exceed 1 DALY per case until age 60, and then surpassed female to reach a maximum of 3.5. (99%)

3.1.3. Severe symptoms

If long-COVID was severe, females had higher morbidity than males in every age group; and female morbidity dropped near-linearly with age, from 9.5 (2% death) in the youngest to 3.5 (85%) in the oldest. Male morbidity remained dominated by mortality and showed only a slight U-shaped association with age, from 2.4 DALY in the youngest (7% death) to 1–3 in middle age (increasing from 4% death to 79%) and 3.6 (98% death) in the oldest.

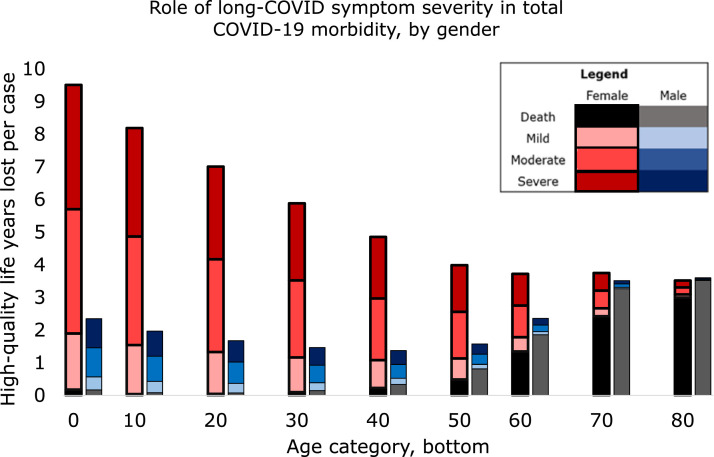

3.2. Model 2: symptoms resolve

If long-COVID symptoms resolved after 10 years ( Fig. 2), total DALY lost to disability were virtually age-invariant (0.22, 0.72, and 1.21 for mild, moderate and severe symptoms in females, and 0.056, 0.18, and 0.30 for males) until around age 60. As a result, morbidity was almost constant until age 40, when CFR began to increase.

Fig. 2.

The top of each colored bar segment represents average healthy years lost per COVID-19 case in that group for that severity of long-COVID symptoms (mild, moderate, or severe), under the assumption that long-COVID resolves in 10 years.

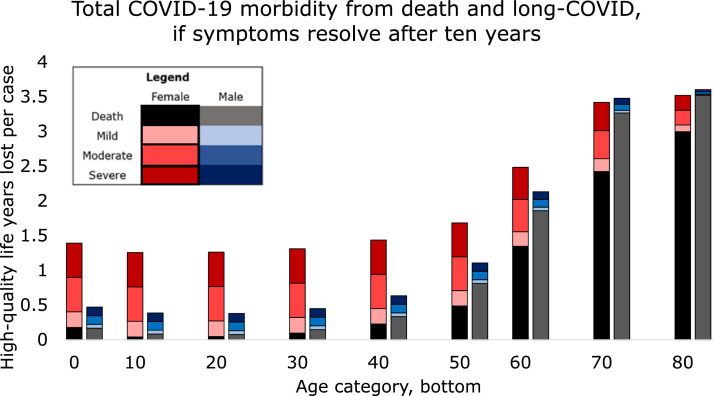

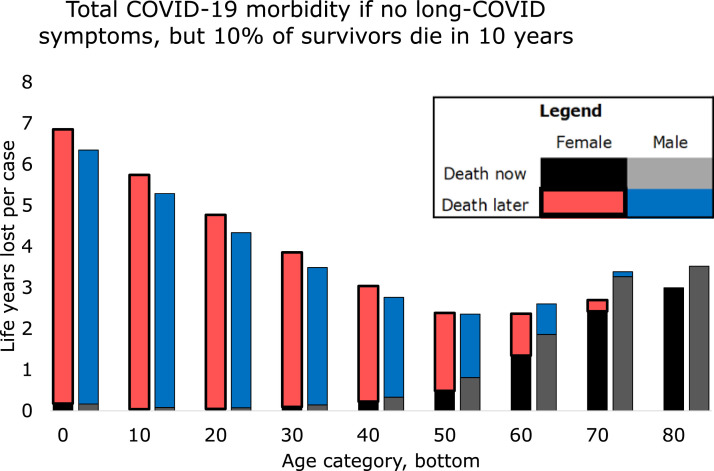

3.3. Model 3: increased mortality

If 10% of long-COVID cases had symptoms that caused mortality an average of 10 years later ( Fig. 3) then even if CFS-type symptoms were absent the situation for both sexes was similar to that for females when CFS-type symptoms were severe. Average female cases under 10 in this scenario lost 6.9 DALY, of which 3% were immediate death and 97% were delayed death. Males in this age group lost 6.3 DALY, (3% immediate death). DALY loss for females after age 50 was nearly constant, between 2.4 and 3.1 per case of which immediate death increased from 7 to 100% as age increased. For males this plateau lasted from age 50-80 (12-71% immediate death) and then DALY increased to 3.6 in the oldest.

Fig. 3.

The top of each bar segment represents average life-years lost per COVID-19 case in that group from immediate death (published case fatality) and delayed death an average of 10 years later, such as might be caused by damaged heart or lungs.

4. Discussion

This paper shows that under all but the most optimistic conditions, acute case fatality is likely to contribute only a small share of total COVID-19 morbidity. In most models total burden fell heavily on females and the young. Rather than focusing solely on mortality, allocators of scarce resources should consider all sources of morbidity.

Rather than give a single estimate of the contribution of acute case fatality to total COVID-19 morbidity, this paper provides a plausible range. It is likely that the truth will contain elements of all three models: chronic CFS-type symptoms of varying severity which may resolve, plus elevated mortality in those survivors or others. In determining which scenario is closest to the truth, researchers should establish long-COVID incidence, both overall and in specific populations; its sex ratio; and its clinical course, which may include remission, death, or some mix.

Our model is limited by variation in the estimated incidence and severity of long-COVID and case fatality, as well as their association with population characteristics. Many of these associations, such as that between long-COVID and female gender, are poorly studied; and all have necessarily short followup. However, our model can be easily updated as new data become available.

Since for each age and sex category DALY due to a given cause are computed by multiplying incidence, duration and disability weight, multiplicative changes in each of these are interchangeable. That is, reducing the incidence of long-COVID by half in a given group would have the same effects as halving its disability weight in that group: reducing the total burden of disease, with the largest reduction being found in young people. For example, based on Rubin's data [2] our models assume that 80% of long-COVID patients are female: if the difference is smaller (for example, due to the predominance of males among COVID-19 myocarditis patients) [10] the population-level burden for a given symptom severity and incidence will move towards the models of ‘mild symptoms’ for females and ‘severe symptoms’ for males.

Significant variation exists in estimates of long-COVID incidence, with surveys in the UK estimating its incidence to be as high as 35% of adults and 12% of schoolchildren [11], or as low as 1.5% of the general population [12]. Children, in particular, are not well studied: and because this group has many healthy years to lose, small differences in estimated incidence, severity and duration of long-COVID translate to large differences in estimated outcomes. More generally, estimated long-COVID incidence depends on study setting (population age and comorbidities, reporting of symptoms by self or others, time and type of followup) as well as artifact (incomplete response.) The 10% estimate used here is near the middle of the estimated range, but likely hides significant between-group variation.

However, it does appear that long-COVID risk increases with patient age and/or with severity of the initial infection. Persistent symptoms have been reported in about a third [11,13] of adults, including some whose initial infection was asymptomatic; and in half, or more than half, of adults who had been hospitalized [7,14]. Risk was lower in children, regardless of infection severity: 24% of children formerly hospitalized for COVID-19 had parent-reported persistent symptoms [15], and between 2% and 5% [16] and 12% [11] of all pediatric cases did. Risk was higher in older children, consistent with an age effect. If the risk and/or severity of long-COVID does in fact increase with age, burden of morbidity is likely to shift away from children and towards middle-aged adults, who would then combine a relatively high incidence of long-COVID with many healthy years to lose. The shape of the morbidity curve is likely to depend on precise age-specific incidence rates, as well as age-related variations in long-COVID symptom severity.

A related issue is that estimates of COVID-19 case fatality have steadily dropped [17] since the beginning of the pandemic, for reasons which may include changes in patient demographics, improvements in treatment [17], or artifact of improved ascertainment [18].Thus the current models likely overestimate morbidity due to death and thus share of morbidity borne by the old; and since case fatality is higher in males [1], of share of morbidity borne by males.

Secondly, our models used disability weights for CFS since none exist for long-COVID. However long-COVID has symptoms that CFS does not, leading to systematic underestimation of the true disability weight of long-COVID. For each additional symptom, the number of DALY lost per case at a given symptom severity increases such that the situation becomes similar to that for a higher symptom severity.

Thirdly, the shape of the long-COVID morbidity curve with age is sensitive to the clinical course of the disease. Under most situations the curve was U-shaped (morbidity high in young and old, lower in middle age) or L-shaped (morbidity highest in the young.) These were the situations if long-COVID caused lifelong disability that was other than mild; increased mortality; or both.

However, there was one model in which the mortality curve was J-shaped and burden of morbidity was borne by the elderly (the situation assumed by current public-health guidelines.) For this to occur, non-mild symptoms must be time-limited, resolving either spontaneously or due to medical advances. For either of these to occur, long-COVID would have to be atypical of postinfectious conditions such as CFS. Full recovery from these conditions is rare:[5] most patients experience fluctuating symptoms, with periods of low and high functioning [9,19], and some deteriorate further. Furthermore ‘recovery’ is often defined relative to the disease state rather than relative to fully restored health: even those reported as recovered often have persistent disability [19]. Thus, while long-COVID patients may experience improvements in symptoms, it seems likely that some disability will remain.

It is also possible that medical advances will improve the long-COVID prognosis. This would require a significant change in current priorities: relative to its disease burden CFS is deprioritized for research funding [5] and although it has been documented for almost a century, many patients have difficulty accessing diagnosis, treatment or services. The same is true for long-COVID [4]. Thus, while it is not impossible that long-COVID will become treatable, this scenario is unlikely under current priorities.

To conclude, these findings establish plausible outer bounds for the sex and age bias of total disease burden of COVID-19. In most situations, most morbidity is in female survivors and in young people. However, these estimates are imprecise and based on incomplete data. Future research should collect and publish better data to allow fair distribution of resources for prevention of COVID-19 infection; and decisionmakers should allocate those resources to minimize total morbidity, according to the best available knowledge.

Author statement

MPS did everything for this single-author paper.

Consent to participate

n/a

Consent for publication

Sole author consents.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Publicly available at cited links.

Code availability

On request.

Ethics approval

Not human-subjects research.

References

- 1.Undurraga E.A., Chowell G., Mizumoto K. COVID-19 case fatality risk by age and gender in a high testing setting in Latin America: Chile, March–August 2020. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10(11):2021. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00785-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rubin R. As their numbers grow, COVID-19 “Long Haulers” stump experts. JAMA. 2020;324(14):1381–1383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bansal AS, Bradley AS, Bishop KN, Kiani-Alikhan S, Ford B. Chronic fatigue syndrome, the immune system and viral infection. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert NJ. COVID-19 “Long Hauler” Symptoms Survey Report; 2020. Survivor corps. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimmock ME Mirin AA, Jason LA. Estimating the disease burden of ME/CFS in the United States and its relation to research funding. J Med Therap. 2016;1(1):1–7. doi: 10.15761/JMT.1000102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, Fahim M, Arendt C, Hoffmann J, et al. Outcomes of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in patients recently recovered from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(11):1265–1273. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557. Published online July 27, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Writing Committee for the COMEBAC Study Group Four-month clinical status of a cohort of patients after hospitalization for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(15):1525–1534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3331. Published online March 17, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Social security period life table, 2017. In: Administration SS, editor.; 2017 https://www.ssa.gov/oact/HistEst/PerLifeTables/2017/PerLifeTables2017.

- 9.CDC US. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: what is ME/CFS? In: Services HaH, editor.; 2018.

- 10.Sawalha K, Abozenah M, Kadado AJ, Battisha A, Al-Akchar M, Salerno C, et al. Systematic review of COVID-19 related myocarditis: insights on management and outcome. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;2021(23):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judd A. UK Office for National Statistics; 2021. COVID-19 schools infection survey, England: prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in school pupils and staff: July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayoubkhani D;, Pawelek P;, Bosworth M. UK Office for National Statistics; 2021. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: Estimates of the prevalence of self-reported "long COVID" and associated activity limitation, using UK Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey data. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logue JK, Franko NM, McCulloch DJ, McDonald D, Magedson A, Wolf CR, et al. Sequelae in adults at 6 months after COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F. For the gemelli against COVID-19 post-acute care study group. persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osmanov IM, Spiridonova E, Bobkova P, Gamirova A, Shikhaleva A, Andreeva M, et al. Risk factors for long covid in previously hospitalised children using the ISARIC Global follow-up protocol: A prospective cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2021 doi: 10.1183/13993003.01341-2021. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Israeli Ministry of Health; 2021. Results of the long-COVID survey among children in Israel. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ledford H. Why do COVID death rates seem to be falling? Nature. 2020;587(2020):190–192. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03132-4. 11 November 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MP. Role of ascertainment bias in determining case fatality rate of COVID-19. J Epidemiol Global Health. 2021;11(2):143–145. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.210401.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adamowicz JL, Caikauskaite I, Friedberg F. Defining recovery in chronic fatigue syndrome: a critical review. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:2407–2416. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]