Abstract

Background

Patients with cancer are considered a priority group for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccination given their high risk of contracting severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, limited data exist regarding the efficacy of immunisation in this population. In this study, we assess the immunologic response after COVID-19 vaccination of cancer versus non-cancer population.

Methods

PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science databases were searched from 01st March 2020 through 12th August 12 2021. Primary end-points were anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S) immunoglobulin G (IgG) seroconversion rates, T-cell response, and documented SARS-CoV-2 infection after COVID-19 immunisation. Data were extracted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Overall effects were pooled using random-effects models.

Results

This systematic review and meta-analysis included 35 original studies. Overall, 51% (95% confidence interval [CI], 41–62) and 73% (95% CI, 64–81) of patients with cancer developed anti-S IgG above the threshold level after partial and complete immunisation, respectively. Patients with haematologic malignancies had a significantly lower seroconversion rate than those with solid tumours after complete immunisation (65% vs 94%; P < 0.0001). Compared with non-cancer controls, oncological patients were less likely to attain seroconversion after incomplete (risk ratio [RR] 0.45 [95% CI 0.35–0.58]) and complete (RR 0.69 [95% CI 0.56–0.84]) COVID-19 immunisation schemes. Patients with cancer had a higher likelihood of having a documented SARS-CoV-2 infection after partial (RR 3.21; 95% CI 0.35–29.04) and complete (RR 2.04; 95% CI 0.38–11.10) immunisation.

Conclusions

Patients with cancer have an impaired immune response to COVID-19 vaccination compared with controls. Strategies that endorse the completion of vaccination schemes are warranted. Future studies should aim to evaluate different approaches that enhance oncological patients’ immune response.

Keywords: Neoplasms, Haematologic neoplasms, COVID-19 vaccines, SARS-CoV-2, Immunogenicity, Vaccines, COVID-19 breakthrough infections

1. Introduction

Since the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first declared pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11th March 2020, the world has faced an unprecedented socioeconomic and health crisis. By 24th September 24, 2021, confirmed COVID-19 cases surpassed 230 million, and more than 4.7 million deaths have been reported worldwide [1]. Patients with cancer are a vulnerable group at increased risk of infection and COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality compared with the non-cancer population [2,3]. A 30-day mortality rate of 20–25% has been documented in this group [4], which is substantially higher than the estimated 3–4% among the general population [5].

Although several therapies in the general population such as dexamethasone, azithromycin, convalescent plasma, antivirals, Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor and monoclonal antibodies have been explored in the ‘Randomised Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy’ “RECOVERY”and 'COV-BARRIER' studies, the vast majority did not show a decrease in mortality rate or length of hospitalisation [6,7]. A substantial proportion of patients who were hospitalised died even when receiving one of the few treatments that have shown an improvement in the overall survival rate (i.e. dexamethasone, tocilizumab and baricitinib) [6,8,9]. Thus, the development and widespread application of COVID-19 vaccines represent the most effective strategy for overcoming the current crisis [10]. Because cancer itself is an independent risk factor for poor COVID-19 prognosis [11], international organisations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), the Asian Oncology Society and the European Society for Medical Oncology have urged the prioritisation of oncological patients for COVID-19 immunisation [[12], [13], [14]].

Even though robust data confirm the safety and efficacy of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines' in preventing COVID-19 among the general population [15,16], data about their performance in oncological patients remain scarce. Recent studies reporting on COVID-19 immunogenicity using anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (S) immunoglobulin G (IgG) titres, a surrogate of humoural response that has been correlated with neutralising antibodies [3,17], have shown a suboptimal response after immunisation in patients with cancer [[18], [19], [20]]. However, owing to the exclusion and underrepresentation of patients with cancer in most COVID-19 vaccines' clinical trials [21], several gaps in knowledge persist regarding vaccines’ effectiveness, best timing for administration, extent and durability of the attained immune response and safety profile in this high-risk population [21]. To refine the existing evidence, a systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to assess seroconversion rates based on anti-S IgG titres after partial and complete COVID-19 immunisation among oncological patients compared with non-cancer participants.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [22]. The complete protocol is available at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) website (ID CRD42021261974) [23].

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

A comprehensive literature search was performed for abstracts and full-text articles published from 01st March 2020 through 12th August 2021 in PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Web of Science databases, using the following search strategy: (neoplasm∗ OR oncolog∗ OR cancer OR malign∗) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR coronavirus) AND (vaccin∗) AND (immun∗ OR sero∗ OR humoral). Retrieved articles were cross-referenced to confirm that all eligible records were identified.

Studies needed to satisfy the following inclusion criteria: (1) assess the immune humoural response rate in patients with cancer based on anti-S SARS-CoV-2 IgG; (2) report original findings (3) be in English, Spanish or French language.

The following variables were recorded: first author; year of publication; study design and methodology; participants' median/mean age; number of controls and patients with cancer; type of malignancy (i.e. solid vs haematological); proportion of patients with cancer undergoing active treatment; type and number of COVID-19 vaccine doses administered; type of anti-S IgG immunoassay and threshold value used to define ‘vaccine responders’; proportion of cancer and non-cancer participants classified as ‘vaccine responders’ and ‘vaccine non-responders’ and their mean/median IgG titres; participants’ T-cell response and number of documented COVID-19 cases after vaccination. Two reviewers extracted the data in duplicate, and disagreements were solved by a third author. For studies with ≥1 publication or having a superimposable population, only the largest study was included in the quantitative analysis.

To assess the risk of bias, two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of each study using the Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies – of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool. Disagreements among reviewers were solved by consensus.

2.2. Study objectives

The primary aim was to assess the proportion of oncological patients classified as vaccine responders, defined as the number of patients with anti-S SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels above each individual study's threshold value versus controls. We hypothesised that patients with haematological malignancies and those with partial immunisation regimens would achieve inferior immunogenicity after COVID-19 immunisation; thus, subgroup analyses assessing seroconversion rates between patients with solid versus haematologic malignancies, as well as partial and complete COVID-19 vaccination regimens, were conducted. As secondary outcomes, the proportion of documented SARS-CoV-2 infection and T-cell response after COVID-19 immunisation in oncological and control subjects was assessed.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The proportion of oncological patients who achieved seroconversion and detectable T-cell response as well as the percentage of patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection after receiving at least one COVID-19 vaccine were assessed using generalised linear mixed-effects models of the logit-transformed proportions of individual studies. Confidence intervals (CIs) of individual studies were calculated with the Clopper-Pearson method, whereas the Hartung-Knapp adjustment was used to calculate the CI around the pooled effect. Between-study variability (τ2) was estimated by the restricted maximum likelihood.

The effect size for binary outcomes is presented as risk ratios (RRs) calculated with the Mantel-Haenszel method, with a corresponding 95% CI as forest plots. The method by Hartung-Knapp was used to adjust test statistics and 95% CI. The corresponding prediction intervals are also reported. Between-study variance was estimated using the Paule-Mandel estimator for τ2, and heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Higgins's I2 and Cochran's Q tests. The relationship between effect estimates and study precision was assessed visually using funnel plots and the Harbord score test. In case asymmetry was detected, a limit meta-analysis was conducted to adjust for small-study effects.

Bivariate metaregressions were used to assess type of COVID-19 vaccine (messenger ribonucleic acid [mRNA] vs mRNA/viral vector), immunisation scheme (incomplete vs complete) and time from the last vaccine dose to the serologic test (<3 vs ≥ 3 weeks from the last dose) as explanatory variables, in terms of the studies’ effect size (outcome variable) when determining the pooled RR of seroconversion rates. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess studies evaluating only mRNA vaccines and for studies with low-to-moderate risk of bias. All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software (version 4.1.0, R Project for Statistical Computing) and RStudio software (version 1.4.1717, R Foundation for Statistical Computing). A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic review and characteristics of the studies

The systematic literature search yielded 1821 records, of which 1287 remained after duplicates were excluded. After title and abstract review, 1233 records were excluded given that they reported non-original findings, did not include patients with cancer or did not assess COVID-19 vaccines’ immunogenicity. Of the 54 articles that underwent full-text review, 35 articles [[17], [18], [19], [20],[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46]] were considered eligible and were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The PRISMA flowchart summarising the process for the identification of eligible studies. Abbreviations: COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Overall, 23 studies evaluated patients with haematological malignancies, five with solid tumours, and seven included both cancer types. Twenty-six studies assessed the effectiveness of mRNA, eight mRNA and viral vector and one inactivated COVID-19 vaccines. Regarding the COVID-19 immunisation regimen, nine studies evaluated patients with incomplete vaccination schemes, 15 assessed fully vaccinated patients, and 11 included both regimens. Only 18 studies had a control group (non-cancer patients). Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis. Most studies had a moderate risk of bias (Supplemental eTable 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies and patient population.

| Author | Country | Design | No. of cancer patients | No. of controls | Patients' age (years) | Type of cancer | Vaccine type | Vaccine scheme | Reported outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addeo et al. [17] | Switzerland/USA | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 244 | NA | 63 (IQR 55–69) | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Agha et al. [41] | USA | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 67 | NA | 71 (IQR 65–77) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Barrière et al. [42] | France | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 122 | 29 | 69.5 (range 44–90) | Solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects |

| Benda et al. [37] | Austria | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 259 | NA | 65.1 (SD 12.2) | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Benjamini et al. [53] | Israel | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 373 | NA | 70 (range 40–89) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab, adverse effects |

| Bird et al. [43] | UK | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 93 | NA | 67 (IQR 59–73) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) and viral vector (AZD1222) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Chowdhury et al. [44] | UK | Multi-centre, prospective, cohort | 59 | 232 | 62 (IQR 52–73) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) and viral vector (AZD1222) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab |

| Cohen et al. [45] | Israel | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 54 | NA | 68.8 (IQR 61.2–76.8) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects |

| Ehmsen et al. [54] | Denmark | Single-centre, prospective | 524 | NA | 70 (IQR 63–75) | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, T-cell response |

| Ghandili et al. [47] | Germany | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 74 | NA | 67.5 (range 40–85) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA and viral vector | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Ghione et al. [46] | USA | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 86 | 201 | NA | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) and viral vector (AD26.COV2.S) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Goshen-Lago et al. [24] | Israel | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 86 | 261 | 66 (SD 12.09) | Solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Greenberger et al. [36] | USA | Prospective, cohort | 1445 | NA | 68 (range 16–110) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Guglielmelli et al. [51] | Italy | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 30 | 14 | 60.8 (range 36.9–80.3) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Harrington, Lavallade et al. [25] | UK | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 21 | NA | 55 (SD 10.71) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab, NAb, T-cell response, adverse effects |

| Harrington, Doores et al. [26] | UK | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 16 | NA | 45.6 (SD 14.8) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab, NAb, T-cell response, adverse effects |

| Herishanuet al [19] | Israel | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 167 | 52 | 71 (IQR 63–76) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab, adverse effects |

| Heudel et al. [52] | France | Prospective, cohort | 1503 | NA | NA | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) and viral vector (ChAdOx1) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Karacin et al. [35] | Turkey | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 47 | NA | 73 (range 64–80) | Solid tumour | Inactivated (CoronaVac) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Lim et al. [27] | UK | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 129 | 150 | 69 (IQR 57–74) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) and viral vector (ChAdOx1) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab |

| Malard et al. [40] | France | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 195 | 30 | 68.8 (range 21.5–91.7) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, T-cell response |

| Maneikis et al. [28] | Lithuania | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 857 | 68 | 65 (IQR 54–72) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Massarweh et al. [18] | Israel | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 102 | 78 | 66 (IQR 56–72) | Solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Monin et al. [20] | UK | Multicentre, prospective, cohort | 151 | 54 | 73 (IQR 64.5–79.5) | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, T-cell response, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Palich et al. [29] | France | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 110 | 25 | 66 (IQR 54–74) | Solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab |

| Parry et al. [48] | UK | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 286 | 93 | 69 (IQR 63–74) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) and viral vector (ChAdOx1) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Pimpinelli et al. [30] | Italy | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 92 | 36 | 74 (range 47–78) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Pimpinelli, Marchesi et al. [50] | Italy | Single-centre, prospective | 42 | NA | 72 (range 52–82) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Re et al. [39] | France | Prospective, cohort | 45 | NA | 77 (range 37–92) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, anti-N IgG Ab, T-cell response |

| Revon-Riviere et al. [31] | France | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 13 | NA | 17 (IQR 16–18) | Haematological malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Re, Barrière et al. [38] | France | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 102 | NA | 75.5 (range 33–93) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab |

| Stampfer et al. [49] | USA | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 103 | 31 | 68 (range 35–88) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Incomplete and complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Thakkar et al. [32] | USA | Multicentre, retrospective, cohort | 200 | 26 | 67 (range 27–90) | Haematologic malignancy and solid tumour | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) and viral vector (AD26.COV2.S) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, adverse effects |

| Tzarfati et al. [33] | Israel | Single-centre, prospective, cohort | 315 | 108 | 71 (IQR 61–78) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

| Van Oekelen et al. [34] | USA | Single-centre, retrospective, cohort | 320 | 67 | 68 (range 38–93) | Haematological malignancy | mRNA (BNT162b2/mRNA1273) | Complete | Anti-S IgG Ab, SARS-CoV-2 infection |

Data are expressed as no. (%) unless otherwise noted.

Abbreviations: USA, United States of America; UK, United Kingdom; NA, not available; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation; Anti-S Ab, anti-spike antibody; Anti-N Ab, anti-nucleocapsid antibody; NAb, neutralising antibody; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

3.2. Anti-S Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 immunoglobin G seroconversion rates

Of the included 35 studies, 20 reported the seroconversion rate in patients with cancer after partial COVID-19 immunisation (2574 patients) [17,20,[24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31],37,[42], [43], [44],[47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]] and 24 after complete vaccination schemes (4708 patients) [[17], [18], [19], [20],27,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42],45,46,48,49,53,54]. A lower seroconversion rate was achieved by those with incomplete vaccination regimens (51%; 95% CI 41–62) compared with those with patients who were fully immunised (73%; 95% CI 64–81) (P = 0.0009) (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Rates of seroconversion in patients with cancer as per the vaccination regimen. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer.

A total of 17 studies that compared seroconversion rates among oncological patients and non-cancer controls (nine with incomplete and 13 with complete immunisation schemes) were analysed. Compared with controls, patients with cancer with an incomplete vaccination scheme had a 55% reduced likelihood of achieving anti-S IgG titres above the threshold level (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.35–0.58), whereas a 31% reduced likelihood of seroconversion was documented among those with a complete vaccination scheme (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.56–0.84) (test for subgroup differences P = 0.0026) (Fig. 3 ). After adjusting for small-study effects, the overall RR was 0.72 (95% CI 0.70–0.75) for seroconversion in oncological patients receiving at least one COVID-19 vaccine compared with controls (Supplemental eFig. 1). Sensitivity analysis of 14 studies evaluating mRNA vaccines (seven with incomplete and 10 with complete schemes) (Supplemental eFig. 2) and studies with low-to-moderate risk of bias showed similar results (Supplemental eFig. 3).

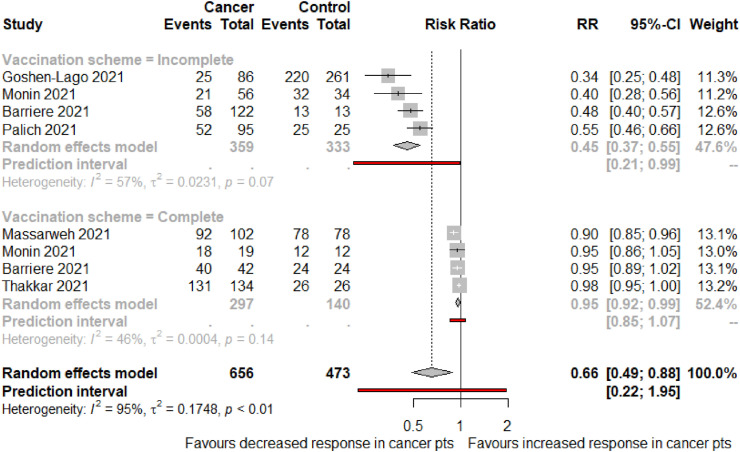

Fig. 3.

Rates of seroconversion in oncological patients versus non-cancer controls as per vaccination scheme. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer.

Meta-regression analyses revealed that incomplete immunisation scheme was a risk factor for lower seroconversion among patients with cancer (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.50–0.86; P = 0.003). No significant association was found for vaccine type and time from the last vaccine dose to the serologic test (Supplemental eTable 2).

A subgroup analysis was performed including six studies that assessed seroconversion rates among patients with solid malignancies compared with non-cancer controls. Four studies assessed patients with incomplete vaccination schemes [20,24,29,42], with a total of 359 oncological patients and 333 controls. Compared with non-cancer controls, patients with solid cancer had a 55% reduced likelihood of achieving threshold humoural response after the first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (RR 0.45; 95% CI 0.37–0.55). Moreover, in studies evaluating 297 patients with cancer who had completed their vaccination regimen [18,20,32,42], a lower seroconversion rate was documented when compared with 140 controls (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.92–0.99) (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Rates of seroconversion in patients with solid malignancies versus non-cancer controls as per vaccination scheme. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer.

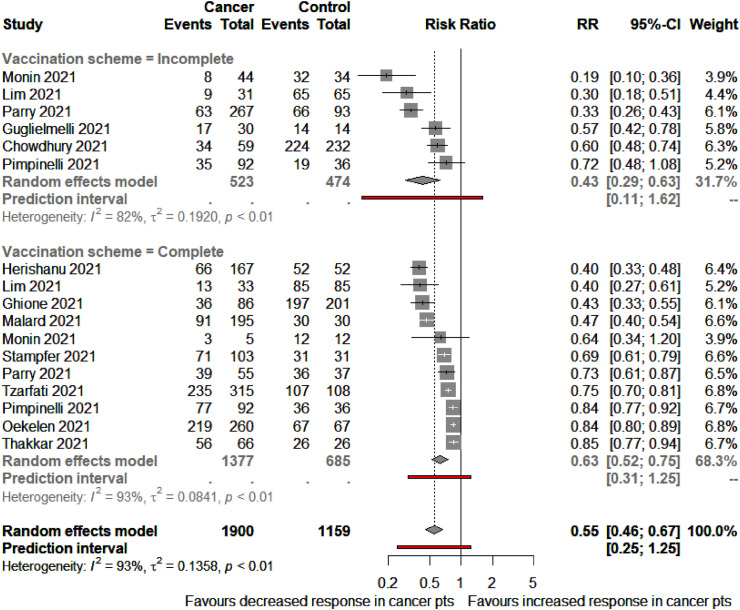

In a subgroup analysis of 13 records evaluating humoural seroconversion rates in patients with haematological malignancies compared with non-cancer controls, six included patients with a partial immunisation regimen [20,27,30,44,48,51], seven with a complete scheme [19,[32], [33], [34],40,46,49] and four with both partial and complete vaccination [20,27,30,48]. In the incomplete immunisation scheme analysis, of the 997 included participants (523 oncological patients and 474 controls), patients with cancer had a 57% reduced likelihood of achieving an adequate humoural response compared with non-cancer controls (RR 0.43; 95% CI 0.29–0.63). Similarly, in the fully vaccinated analysis, patients with haematological malignancies had lower seroconversion rates than non-cancer controls (RR 0.63; 95% CI 0.52–0.75) (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Rates of seroconversion in patients with haematological malignancies versus non-cancer controls as per vaccination scheme. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer.

When comparing serological response between types of malignancies after partial immunisation, patients with haematological cancer achieved a numerically lower response (49%; 95% CI 35–63) than those with solid tumours (53%; 95% CI 33–72) (P = 0.183) (Fig. 6 ). When analysing serological response after complete immunisation regimens, patients with haematologic malignancies had a significantly reduced humoural response (65%; 95% CI 57–72) than those with solid cancer (94%; 95% CI 86–97) (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 6.

Rates of seroconversion in patients with haematological versus solid malignancies and incomplete COVID-19 vaccination regimen. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019.

Fig. 7.

Rates of seroconversion in patients with haematologic versus solid malignancies and complete COVID-19 vaccination regimen. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019.

3.3. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 infection after vaccination

In a pooled analysis of 14 studies including patients with haematological or solid malignancies [17,20,24,[28], [29], [30], [31],33,34,37,42,47,49,52], a subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection was documented in 0.78% (95% CI 0.18–3.26; I2 = 33%) of the 1444 patients with a partial COVID-19 vaccination regimen and in 0.41% (95% CI 0.09–1.89; I2 = 51.5%) of the 3000 patients with a complete vaccination regimen (P = 0.4976). Overall, patients with cancer had a 0.55% (95% CI 0.20–1.5; I2 = 59.5%) likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection after being immunised with at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccines. Moreover, when compared with non-cancer controls, oncological patients had a tendency towards increased documented SARS-CoV-2 infection after partial (RR 3.21; 95% CI 0.35–29.04) and complete COVID-19 immunisation (RR 2.04; 95% CI 0.38–11.10) (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in oncological patients after vaccination compared with controls. Squares represent indirect effect size (Risk ratio [RR]). Horizontal lines indicate 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Diamonds indicate the meta-analytic pooled RR, calculated separately by vaccination scheme (i.e., partial or complete), and the overall pooled RR (95%CI) in patients with cancer. SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2.

3.4. Anti-S Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 immunoglobin G antibody titres

No meta-analysis was conducted regarding anti-S IgG titres owing to the wide heterogenicity in serological immunoassays used in the eight studies reporting data on this outcome for both patients and controls (Supplemental eTable 3) [18,19,28,29,33,34,42,44]. Overall, lower anti-S IgG titres were documented in patients with cancer after partial and complete immunisation among individual studies.

3.5. T-cell response among oncological patients

A pooled analysis of six studies [20,25,26,39,40,54] including 84 patients with incomplete and 634 with complete vaccination regimens showed that 78% (95% CI 30–97) and 60% (95% CI 30–84) developed an adequate T-cell response, respectively (Supplemental eFig. 4).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in the oncological population. Results of this meta-analysis demonstrate that patients with cancer have a lower likelihood of attaining acceptable immune response after COVID-19 immunisation when compared with non-cancer patients. However, despite the suboptimal seroconversion rates observed in this group, a notable increase in humoural response was documented among patients with cancer who completed a COVID-19 vaccination regimen.

The low humoural immune response mounted by oncological patients after being vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 is of utmost importance owing to their higher risk of developing severe disease with consequent poor prognosis if infected [4,11,55,56]. Immunisation against COVID-19 has been widely recommended among patients with cancer, regardless of the site of disease, setting and type of treatment, as its benefits outweigh the potential risks [55,57]. Oncological patients should be encouraged to adhere to COVID-19 prevention guidelines and complete their vaccination schemes after the recommended intervals between doses (i.e. three or four weeks for mRNA vaccines). As shown by this meta-analysis, a substantial proportion of patients with cancer do not mount an appropriate immunological response after partial vaccination and could be at a relatively high risk of infection and severe COVID-19 when delaying the second dose.

Furthermore, despite patients with cancer having a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination compared with controls, only 0.55% of patients developed COVID-19 after being immunised. These findings are encouraging as they highlight that even though this population has a lower likelihood of mounting an adequate immune response after vaccination, their risk of infection may drop significantly after being vaccinated. However, conclusions should be cautiously drawn as the low rate of infection documented in each study may be influenced by the epidemic burden of COVID-19 across countries and specific time points, as well as the underestimation of SARS-CoV-2 cases owing to the lack of testing in asymptomatic participants, which could be as high as 20% [58], and to an inadequate follow-up.

Growing evidence suggests that among patients with cancer, those with haematological malignancies are less likely to develop robust anti-S IgG after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination owing to immunosuppression induced by disease-related lineage defects and its treatments [3,17,35,36]. Consistently, when stratifying by type of cancer, we observed that patients with haematological malignancies had the highest risk of being non-responders after complete COVID-19 vaccination. Furthermore, oncologic regimens based on monoclonal antibodies (anti-CD20, anti-CD38), Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor, Bcl-2 inhibitor, Janus Kinase 1/2 inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy have been associated with lower seroconversion rates [17,19,[27], [28], [29],33,34,[38], [39], [40],42,[44], [45], [46], [47], [48],51,53,54]. Of note, monoclonal antibodies (i.e. anti-CD20) might not only blunt B-cell response by decreasing the neutralising antibodies titres but may also affect patients’ T-cell immunity [3,17,36,58]. Thus, a markedly reduced response to COVID-19 immunisation could be expected in patients receiving therapeutic agents that interfere with humoural and cellular response.

Recent data suggest that among patients with suboptimal humoural immunogenicity to COVID-19 vaccines a substantial proportion developed T-cell response, most likely owing to cross-reactivity to other human coronaviruses [58]. Although new evidence from the Vaccination Against COVID in Cancer (VOICE) and Coronavirus Disease 2019 Antiviral Response in a Pan-tumor Immune Monitoring (CAPTURE) trials have shown that chemotherapy was not a significant predictor for suboptimal immunogenicity in patients with solid tumours [58,59], numerous studies have documented the potential detrimental impact that chemotherapy could have in seroconversion rates after COVID-19 immunisation in patients with cancer [17,18,20,25,30,33,35,38,41,46,54]. Further studies with sufficient statistical power to evaluate the influence of different oncological treatments on COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity among patients with solid and haematological malignancies are warranted.

The optimal approach for administering COVID-19 vaccines among patients with higher risk of non-responsiveness remains unclear. As per NCCN guidelines, only patients with stem cell transplant and those receiving cellular therapy should wait for at least three months after finishing the therapy to get vaccinated against COVID-19, otherwise, patients with cancer should get vaccinated as soon as they can [57]. However, the administration of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies within 12 months and chemotherapy within four weeks before vaccination could diminish patients’ immune response [17,19,27,28,[38], [39], [40],58,59]. Thus, oncologists should warn patients, particularly those with haematological malignancies such as leukaemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma and those who received COVID-19 vaccines while being under these treatments that they might not have an appropriate protection against SARS-CoV-2 wild-variant and variants of concern [58].

Several studies have already demonstrated the benefits of a booster COVID-19 vaccine dose after completion of the standard immunisation scheme among immunocompromised and patients with cancer [39,[60], [61], [62], [63], [64]]. Therefore, health authorities in France, Israel, Germany and the United Kingdom have issued statements advocating for a booster vaccine dose in immunocompromised patients [17]. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recently authorised the administration of a homologous booster dose for solid organ transplant recipients and those with an equivalent level of immunosuppression [65,66]. The implementation of this strategy has demonstrated a significant increase in patients’ humoural response [39,61,62,64]. Nonetheless, a substantial proportion of the evaluated patients did not attain seroconversion even after receiving a third dose, which could limit the benefits of homologous booster vaccination for immunocompromised patients [39,[60], [61], [62],64].

Another promising strategy that has gained interest for enhancing patients’ immune response after COVID-19 vaccination is the use of heterologous vaccine regimens. Recent studies assessing this approach among the general population have yielded encouraging results, reporting higher anti-S IgG titres and neutralising antibodies against certain SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern, as well as an increased CD4 T-cell response compared with homologous COVID-19 vaccine regimens [[67], [68], [69], [70]]. Clinical investigators, industry and regulatory stakeholders should encourage the development of clinical and observational studies such as the COVID-19 Vaccine Cohort in Specific Populations (COV-POPART) study [71] that aims to evaluate different immunisation approaches in the oncological population, including the use of booster doses and heterologous vaccination schemes.

As the most effective strategy for tackling the burden imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, immunisation should be particularly encouraged among the oncological population. Efforts should also be focused on increasing the available information regarding the effectiveness, safety profile and benefits of COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Moreover, the promotion of vaccine literacy and the active participation of oncologists and other health-care workers should be emphasised, as these remain key to increase patients’ acceptance and adherence to the recommended vaccination schemes [[72], [73], [74], [75]]. Despite several countries having removed restrictions such as the use of face masks and social distancing for those that have completed their COVID-19 vaccination scheme, these measures should be taken cautiously and should not be extended automatically to all patients with cancer in whom vaccine effectiveness is not comparable to that of the general population.

5. Limitations

Among the limitations of this meta-analysis, it should be considered that the number of included studies, as well as the heterogeneity across them regarding patient and control characteristics, patients’ type of malignancy and treatment, immunogenicity assessment and type of vaccine, may limit the generalisation of the results. It is particularly important to highlight that the included studies are observational and subject to potential sources of bias, such as selection bias or confounding, that cannot be adjusted through meta-analytical techniques. All included studies evaluated anti-S IgG as a surrogate for COVID-19 immunogenicity, and just a few assessed cellular response or SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination. However, owing to the high sensitivity and specificity of most immunoassays and the minimal likelihood of infection in immunised patients, it is reasonable to expect that anti-S IgG levels correlate with neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 [17], thus allowing for an adequate COVID-19 effectiveness evaluation. Owing to the substantial heterogeneity in immunoassays and threshold values for anti-S IgG measurements, differences in mean titres between patients with cancer and controls could not be compared. The present results have limited generalisability to COVID-19 vaccines different from mRNA Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2), as only a few studies included patients who received other types of vaccines. Although the type of treatment administered in parallel with a COVID-19 vaccine could play an important role in the degree of humoural and cellular responses attained by oncological patients, the lack of sufficient data did not allow to perform subgroup analyses in this regard. Finally, an important amount of funnel plot asymmetry was detected, particularly towards the null hypothesis. However, the difference in seroconversion rates between patients with cancer and controls remained significant after adjusting the pooled effect by limit meta-analysis. As the number of studies in oncological patients increases, robust methodologies to explore the sources of heterogeneity should be implemented, such as meta-regression, which could help refine our current estimates.

6. Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that oncological patients attain a lower immunological response when compared with non-cancer controls. Even after completing the immunisation scheme, patients with haematological and solid malignancies showed inferior seroconversion rates than those without cancer. Despite this suboptimal immunologic response, SARS-CoV-2 infection was documented only in a small percentage of immunised cancer patients. Studies focussing on strategies to enhance the immune response among oncological patients are urgently warranted, as well as those evaluating the effectiveness, feasibility and optimal timing for this population to receive a booster dose after completing the COVID-19 immunisation regimen.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Cynthia Villarreal-Garza declares grants from AstraZeneca and Roche; speaking honoraria from Roche, Myriad Genetics, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly; travel fees from Roche, MSD Oncology and Pfizer; and advisory roles at Roche, Novartis, Pfizer and Eli Lilly. Matteo Lambertini declares advisory role for Roche, Lilly, Novartis, Exact Sciences and AstraZeneca; speaker honoraria from Roche, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz and Takeda outside the submitted work. Marco Tagliamento declares travel grants from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca and Takeda: honoraria as medical writer from Novartis and Amgen outside the submitted work. No other disclosures to report.

Author contributions

Andrea Becerril-Gaitan, Bryan F. Vaca-Cartagena, Ana S. Ferrigno and Fernanda Mesa-Chavez contributed to the study conceptualisation and methodology. Cynthia Villarreal-Garza should be recognised for the project administration and supervision. Andrea Becerril-Gaitan, Bryan F. Vaca-Cartagena, Ana S. Ferrigno and Fernanda Mesa-Chavez performed the data collection. Ana S. Ferrigno and Tonatiuh Barrientos-Gutiérrez conducted the formal data analyses. Andrea Becerril-Gaitan and Bryan F. Vaca-Cartagena performed the writing of the original draft and visualisation. Andrea Becerril-Gaitan, Bryan F. Vaca-Cartagena, Ana S. Ferrigno, Fernanda Mesa-Chavez, Tonatiuh Barrientos-Gutiérrez, Matteo Lambertini, Marco Tagliamento and Cynthia Villarreal-Garza reviewed and edited the article. All authors read and approved the final article.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2021.10.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center COVID-19 map - johns hopkins coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- 2.Liang W., Guan W., Chen R., Wang W., Li J., Xu K., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffiths E.A., Segal B.H. Immune responses to COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer: promising results and a note of caution. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1045–1047. doi: 10.1016/J.CCELL.2021.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tagliamento M., Agostinetto E., Bruzzone M., Ceppi M., Saini K.S., de Azambuja E., et al. Mortality in adult patients with solid or hematological malignancies and SARS-CoV-2 infection with a specific focus on lung and breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021:163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . 2021. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 3 March 2020.https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---3-march-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marconi V.C., Ramanan A.V., de Bono S., Kartman C.E., Krishnan V., Liao R., et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib for the treatment of hospitalised adults with COVID-19 (COV-BARRIER): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00331-3. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RECOVERY Collaborative Group . 2021. Randomised evaluation of COVID-19 therapy.https://www.recoverytrial.net/results [Google Scholar]

- 8.RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RECOVERY Collaborative Group Tocilizumab in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): a randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1637–1645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00676-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mallapaty S. Can COVID vaccines stop transmission? Scientists race to find answers. Nature. 20212021 doi: 10.1038/D41586-021-00450-Z. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00450-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Azambuja E., Brandão M., Wildiers H., Laenen A., Aspeslagh S., Fontaine C., et al. Impact of solid cancer on in-hospital mortality overall and among different subgroups of patients with COVID-19: a nationwide, population-based analysis. ESMO Open. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ribas A., Sengupta R., Locke T., Zaidi S., Campbell K., Carethers J., et al. Priority COVID-19 vaccination for patients with cancer while vaccine supply is limited. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:233–236. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ong M.B.H. 2021. Cancer groups urge CDC to prioritize cancer patients for COVID-19 vaccination - the Cancer Letter.https://cancerletter.com/covid-19-cancer/20210108_2/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.MC G., JG W., LC H., A T., V T., F A., et al. COVID-19 in patients with thoracic malignancies (TERAVOLT): first results of an international, registry-based, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:914–922. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30314-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Addeo A., Shah P.K., Bordry N., Hudson R.D., Albracht B., Marco M Di, et al. Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA vaccines in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1091–1098.e2. doi: 10.1016/J.CCELL.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarweh A., Eliakim-Raz N., Stemmer A., Levy-Barda A., Yust-Katz S., Zer A., et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(8):1133–1140. doi: 10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2021.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herishanu Y., Avivi I., Aharon A., Shefer G., Levi S., Bronstein Y., et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137:3165–3173. doi: 10.1182/BLOOD.2021011568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monin L., Laing A.G., Muñoz-Ruiz M., McKenzie D.R., del M del Barrio I., Alaguthurai T., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of one versus two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b2 for patients with cancer: interim analysis of a prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:765–778. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai A., Gainor J.F., Hegde A., Schram A.M., Curigliano G., Pal S., et al. COVID-19 vaccine guidance for patients with cancer participating in oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:313–319. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00487-z. 185 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:332–336. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.B2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villarreal-Garza C., Becerril-Gaitan A., Vaca-Cartagena B., Ferrigno A., Mesa-Chavez F. Immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines among patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Natl Inst Heal Res. 2021 https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=261974 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goshen-Lago T., Waldhorn I., Holland R., Szwarcwort-Cohen M., Reiner-Benaim A., Shachor-Meyouhas Y., et al. Serologic status and toxic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):1507–1513. doi: 10.1001/JAMAONCOL.2021.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrington P., de Lavallade H., Doores K.J., O'Reilly A., Seow J., Graham C., et al. Single dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 induces high frequency of neutralising antibody and polyfunctional T-cell responses in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leuk. 2021;2021:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01300-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrington P., Doores K.J., Radia D., O’Reilly A., Lam H.P.J., Seow J., et al. Single dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) induces neutralising antibody and polyfunctional T-cell responses in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(6):999–1006. doi: 10.1111/BJH.17568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim S.H., Campbell N., Johnson M., Joseph-Pietras D., Collins G.P., Fox C.P., et al. Antibody responses after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with lymphoma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e542–e544. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00199-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maneikis K., Šablauskas K., Ringelevičiūtė U., Vaitekėnaitė V., Čekauskienė R., Kryžauskaitė L., et al. Immunogenicity of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine and early clinical outcomes in patients with haematological malignancies in Lithuania: a national prospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e583–e592. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palich R., Veyri M., Marot S., Vozy A., Gligorov J., Maingon P., et al. Weak immunogenicity after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in treated cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1051–1053. doi: 10.1016/J.ANNONC.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pimpinelli F., Marchesi F., Piaggio G., Giannarelli D., Papa E., Falcucci P., et al. Fifth-week immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with multiple myeloma and myeloproliferative malignancies on active treatment: preliminary data from a single institution. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:1–12. doi: 10.1186/S13045-021-01090-6. 141 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revon-Riviere G., Ninove L., Min V., Rome A., Coze C., Verschuur A., et al. The BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a monocentric experience. Eur J Cancer. 2021;154:30–34. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCA.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thakkar A., Gonzalez-Lugo J.D., Goradia N., Gali R., Shapiro L.C., Pradhan K., et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1081–1090.e2. doi: 10.1016/J.CCELL.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herzog Tzarfati K., Gutwein O., Apel A., Rahimi-Levene N., Sadovnik M., Harel L., et al. BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine is significantly less effective in patients with hematologic malignancies. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(10):1195–1203. doi: 10.1002/AJH.26284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oekelen O Van, Gleason C.R., Agte S., Srivastava K., Beach K.F., Aleman A., et al. Highly variable SARS-CoV-2 spike antibody responses to two doses of COVID-19 RNA vaccination in patients with multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39 doi: 10.1016/J.CCELL.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karacin C., Eren T., Zeynelgil E., Imamoglu G.I., Altinbas M., Karadag I., et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the CoronaVac vaccine in patients with cancer receiving active systemic therapy. Future Oncol. 2021;17(33):4447–4456. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenberger L.M., Saltzman L.A., Senefeld J.W., Johnson P.W., DeGennaro L.J., Nichols G.L. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1031–1033. doi: 10.1016/J.CCELL.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benda M., Mutschlechner B., Ulmer H., Grabher C., Severgnini L., Volgger A., et al. Serological SARS-CoV-2 antibody response, potential predictive markers and safety of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in haematological and oncological patients. Br J Haematol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/bjh.17743. bjh.17743. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Re D., Barrière J., Chamorey E., Delforge M., Gastaud L., Petit E., et al. Low rate of seroconversion after mRNA anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;26:1–3. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2021.1957877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Re D., Seitz-Polski B., Carles M., Brglez V., Graça D., Benzaken S., et al. Humoral and cellular responses after a third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine in patients treated for lymphoid malignancies. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.18.21260669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malard F., Gaugler B., Gozlan J., Bouquet L., Fofana D., Siblany L., et al. Weak immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:142. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agha M., Blake M., Chilleo C., Wells A., Haidar G. Suboptimal response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in hematologic malignancies patients. MedRxiv Prepr Serv Heal Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.04.06.21254949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barrière J., Chamorey E., Adjtoutah Z., Castelnau O., Mahamat A., Marco S., et al. Impaired immunogenicity of BNT162b2 anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in patients treated for solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1053–1055. doi: 10.1016/J.ANNONC.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bird S., Panopoulou A., Shea R.L., Tsui M., Saso R., Sud A., et al. Response to first vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet Haematol. 2021;8:e389–e392. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(21)00110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chowdhury O., Bruguier H., Mallett G., Sousos N., Crozier K., Allman C., et al. Impaired antibody response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with chronic myeloid neoplasms. Br J Haematol. 2021;194(6):1010–1015. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen D., Hazut Krauthammer S., Cohen Y.C., Perry C., Avivi I., Herishanu Y., et al. Correlation between BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine-associated hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy and humoral immunity in patients with hematologic malignancy. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2021;2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/S00259-021-05389-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghione P., Gu J., Attwood K., Torka P., Goel S., Sundaram S., et al. Impaired humoral responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with lymphoma receiving B-cell directed therapies. Blood. 2021;138(9):811–814. doi: 10.1182/BLOOD.2021012443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghandili S., Schönlein M., Lütgehetmann M., Schulze zur Wiesch J., Becher H., Bokemeyer C., et al. Post-vaccination anti-SARS-CoV-2-antibody response in patients with multiple myeloma correlates with low CD19+ B-lymphocyte count and anti-CD38 treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:3800. doi: 10.3390/cancers13153800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parry H., McIlroy G., Bruton R., Ali M., Stephens C., Damery S., et al. Antibody responses after first and second Covid-19 vaccination in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11(7):136. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00528-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stampfer S.D., Goldwater M.-S., Jew S., Bujarski S., Regidor B., Daniely D., et al. Response to mRNA vaccination for COVID-19 among patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41375-021-01354-7. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pimpinelli F., Marchesi F., Piaggio G., Giannarelli D., Papa E., Falcucci P., et al. Lower response to BNT162b2 vaccine in patients with myelofibrosis compared to polycythemia vera and essential thrombocythemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14 doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01130-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guglielmelli P., Mazzoni A., Maggi L., Kiros S.T., Zammarchi L., Pilerci S., et al. Impaired response to first SARS-CoV-2 dose vaccination in myeloproliferative neoplasm patients receiving ruxolitinib. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(11):E408–E410. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26305. ajh.26305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heudel P., Favier B., Assaad S., Zrounba P., Blay J.-Y. Reduced SARS-CoV-2 infection and death after two doses of COVID-19 vaccines in a series of 1503 cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(11):1443–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benjamini O., Rokach L., Itchaki G., Braester A., Shvidel L., Goldschmidt N., et al. Safety and efficacy of BNT162b mRNA Covid19 Vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2021 doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279196. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ehmsen S., Asmussen A., Jeppesen S.S., Nilsson A.C., Østerlev S., Vestergaard H., et al. Antibody and T cell immune responses following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saini K.S., Martins-Branco D., Tagliamento M., Vidal L., Singh N., Punie K., et al. Emerging issues related to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Oncol Ther. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40487-021-00157-1. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Siempos . 2020. Effect of cancer on clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis of patient data; pp. 799–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.NCCN COVID-19 vaccination guide for people with cancer 2021. https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/covid-vaccine-and-cancer-05.pdf?sfvrsn=45cc3047_2

- 58.Fendler A., Shepherd S., Au L., Wilkinson K., Wu M., Byrne F., et al. Adaptive immunity and neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern following vaccination in patients with cancer: the CAPTURE study. Nat Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s43018-021-00274-w. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oosting S., van der Veldt A., GeurtsvanKessel C., Fehrmann R., van Binnendijk R., Dingemans A.M., et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccination in patients receiving chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or chemoimmunotherapy for solid tumours: a prospective, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00574-X. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamar N., Abravanel F., Marion O., Couat C., Izopet J., Del Bello A. Three doses of an mRNA covid-19 vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):661–662. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2108861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Werbel W.A., Boyarsky B.J., Ou M.T., Massie A.B., Tobian A.A.R., Garonzik-Wang J.M., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a third dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in solid organ transplant recipients: a case series. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174(9):1330–1332. doi: 10.7326/L21-0282. L21-0282 https://10.7326/L21-0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benotmane I., Gautier G., Perrin P., Olagne J., Cognard N., Fafi-Kremer S., et al. Antibody response after a third dose of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in kidney transplant recipients with minimal serologic response to 2 doses. JAMA. 2021;326(11):1063–1065. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.12339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill J.A., Ujjani C.S., Greninger A.L., Shadman M., Gopal A.K. Immunogenicity of a heterologous COVID-19 vaccine after failed vaccination in a lymphoma patient. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:1037–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hall V.G., Ferreira V.H., Ku T., Ierullo M., Majchrzak-Kita B., Chaparro C., et al. Randomized trial of a third dose of mRNA-1273 vaccine in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1244–1246. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2111462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.FDA . 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes additional vaccine dose for certain immunocompromised individuals.https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-vaccine-dose-certain-immunocompromised [Google Scholar]

- 66.CDC . 2021. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently authorized in the United States.https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/covid-19-vaccines-us.html [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barros-Martins J., Hammerschmidt S.I., Cossmann A., Odak I., Stankov M.V., Morillas Ramos G., et al. Immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants after heterologous and homologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/BNT162b2 vaccination. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1525–1529. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Normark J., Vikström L., Gwon Y.-D., Persson I.-L., Edin A., Björsell T., et al. Heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 and mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(11):1049–1051. doi: 10.1056/nejmc2110716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schmidt T., Klemis V., Schub D., Mihm J., Hielscher F., Marx S., et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of heterologous ChAdOx1 nCoV-19/mRNA vaccination. Nat Med. 2021;27(9):1530–1535. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01464-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu X., Shaw R.H., Stuart A.S.V., Greenland M., Aley P.K., Andrews N.J., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of heterologous versus homologous prime-boost schedules with an adenoviral vectored and mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (Com-COV): a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10303):856–869. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Loubet P., Wittkop L., Tartour E., Parfait B., Barrou B., Blay J., et al. A French cohort for assessing COVID-19 vaccine responses in specific populations. Nat Med. 2021;27 doi: 10.1038/S41591-021-01435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Villarreal-Garza C., Vaca-Cartagena B.F., Becerril-Gaitan A., Ferrigno A.S., Mesa-Chavez F., Platas A., et al. Attitudes and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(8):1242–1244. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barrière J., Gal J., Hoch B., Cassuto O., Leysalle A., Chamorey E., et al. Acceptance of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among French patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:673–674. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Noronha V., Abraham G., Kumar Bondili S., Rajpurohit A., Menon R.P., Gattani S., et al. COVID-19 vaccine uptake and vaccine hesitancy in Indian patients with cancer: a questionnaire-based survey. Cancer Res Stat Treat. 2021;4:211–218. doi: 10.4103/crst.crst_138_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Villarreal-Garza C., Vaca-Cartagena B., Becerril-Gaitan A., Ferrigno A. Strategies aimed at overcoming COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among oncologic patients. Cancer Res Stat Treat. 2021;4(3):561–562. doi: 10.4103/crst.crst_173_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.