Abstract

Introduction

Implementation of care bundles was shown to reduce the incidence of device-associated infections (DAIs). Substantial improvements in the rate of infection have been achieved by applying educational programs for infection control. Objectives: To demonstrate the impact of a comprehensive care bundle educational program (CCBEP) on DAIs, mortality rates in an emergency Intensive Care Unit (ICU), and improving healthcare workers (HCWs’) knowledge, compliance to care bundle, and infection control practice.

Methods

A quasi-experimental study was carried out in an 15-beds emergency ICU, from May 2017 to October 2018. A comprehensive care bundle educational program was implemented. It covers items regarding device care bundle and infection control.

Results

Device care bundle compliance was variable between different bundle items. There was a significant improvement in HCWs’ knowledge after the educational program intervention especially in hand hygiene, catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) bundle, and total knowledge. There was a higher risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), and CAUTI in the pre-intervention phase compared to post-intervention (RR: 1.4, 1.4, and 1.9 respectively). The total mortality rate decreased from 24.2/100 to 16.7/100 patients after intervention.

Conclusions

There was a statistically significant improvement in compliance with device care bundles with a decrease in the incidence of DAIs.

Keywords: Educational program, care bundles, DAIs, compliance, HCWs’, emergency ICU

Introduction

Device-associated infections (DAIs) include ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI), and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI). DAIs represent a serious threat to patient safety and are in resource-limited countries one of the most serious causes of morbidity and mortality. It has been reported that DAIs are an important cause of healthcare costs, but it is possible to reduce the incidence of DAIs by as much as 30%, resulting in a correlative reduction in healthcare costs.1 The implementation of care bundles has been shown to reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired and DAIs and limit the emergence of multidrug resistant organisms in the intensive care unit (ICU).2 Significant reductions in the rate of infection have been obtained by applying a basic educational infection control program, conducting device-associated infection surveillance, and providing continuous performance feedback in the ICU.3 Given the importance of comprehensive efforts to combat the DAI problem in the ICU, we hypothesized a comprehensive care bundle educational program (CCBEP), an educational program concerned with many aspects of patient care, will improve the outcome of DAIs. The program includes DAI prevention care bundles and infection control policies in ICUs. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has researched the effect of the implementation of such a CCBEP on DAIs in an emergency ICU.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the impact of the implementation of a CCBEP on reducing device-associated infections and mortality rates in an emergency ICU and improve healthcare workers’ (HCWs) knowledge and compliance with care bundles.

Methods

Study design and setting

A quasi-experimental 18-month long study was conducted in the emergency ICU in Zagazig University Hospitals, Sharkeia Governorate, Egypt. The investigated ICU received approximately 900 cases per year, for more than 18 years. The study was divided into two phases. Phase 1 (pre-intervention period: May 2017 – October 2017), during which HCWs’ knowledge and compliance with device care bundle components, the incidences of DAIs, and mortality rates were evaluated. Phase 2 (intervention period: November 2017 – May 2018) included the implementation of a CCBEP. Phase 3 (post-intervention period: May 2018 – October 2018) included a program evaluation process.

Study population

In phase 1, all admitted cases in the investigated ICU that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were enrolled. An equal number of cases with matched age and sex were investigated in the post-intervention phase. On-duty HCWs were assessed for their knowledge and observed, on duty, for their compliance with care bundles.

Inclusion criteria included patients who had invasive devices (endotracheal tube, central vascular catheter, and urinary catheter), admitted in the investigated ICU, and who had the device inserted for more than 48 hours. Intubated patients, patients with an inserted central venous catheter or urinary catheter before ICU admission, previously hospitalized patients in the preceding three months, immune-compromised patients or patients on immunosuppressive drugs, and patients with chronic diseases were excluded.

Case definition

Diagnosis of VAP, CLABSI, and CAUTI was based on standardized CDC/NHSN definitions.4

Outcome measures

Incidence and mortality rates for DAIs in the ICU, as well as the rate of compliance with device care bundle components and HCWs’ knowledge regarding infection control policies and procedures.

Data collection tools

Phases 1 and 3: compliance with care bundle implementation was measured using checklists.5 Detailed measures are listed in Supplements 1-4. The “all or none” rule was used for considering the overall compliance for each device. The incidences of DAI and mortality rates were calculated.6 For HCWs’ knowledge assessment, a semi-structured questionnaire adapted from a similar study was used.5 For each question, the right answer was scored as “1” and the wrong answer or “I do not know” was scored as “0”. More than 75% was “good,” from 50% to 75% was “fair,” and less than 50% was “poor/unsatisfactory” knowledge. A panel of three professionals reviewed the questionnaire to confirm its validity. The reliability of the questionnaire was confirmed by a Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of 0.79, for most of the questions.

The intervention - comprehensive care bundles educational program

Given that well-conducted needs assessments lead to good changes in learner behavior,7 the educational needs assessment was collected in the pre-intervention phase from the records, by interviewing the ICU staff, from clinical rounds discussion, with the help of expert opinion.

The educational program included educational sessions in the form of lectures, 30 minutes each (to small groups), on-the-job training (daily during clinical rounds), weekly seminars (90 minutes each) about device care bundles, and infection control measures, namely hand hygiene, disinfection and sterilization, and personal protective equipment.

The following tools were used: PowerPoint presentations, colored posters with motivational messages, hand hygiene posters, workplace reminders about device care bundle components, leaflets, flowcharts, and didactic videos.

Data analysis

The collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science version 21.0 (IBM Corp., USA). Qualitative data were presented as frequencies and relative percentages. Relative risk (RR) and relative risk reduction (RRR) were determined. The Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate the difference between the qualitative variables. The McNemar test was used to calculate the difference between the paired qualitative variables. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Zagazig University Institutional Review Board (ZU-IRB #2710-9-3-2017). Participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Privacy and confidentiality were ensured.

Results

This study investigated 240 patients (120 in each phase). The median age was 45 years in the first phase (before the intervention) and 44 years in the third phase (after the intervention). Males represented 61.7% and 63.3% of the groups before and after the intervention, respectively. The average duration of ICU stay was 8.5 days in the first phase and 7 days in the third phase. A total of 62.5% of patients died and 37.5% of them were transferred before the intervention, while 61.7% died after the intervention and 38.3% were transferred.

The mean intubation and CVC insertion duration consisted of 9 days for phase 1, while the mean intubation and CVC insertion duration for phase 2 was 7 days. The mean urinary catheter days in phase 1 was equal to 8.5, while in phase 2 it was 7 days, and there was no significant change in device days before and after the intervention. The frequencies of patients with VAP in phase 1 and phase 2 were 59.6% and 40.4%, respectively. The frequencies of patients with CLABSI in phase 1 and phase 2 were 59.5% and 40.5%, respectively. The frequency of patients with CAUTI in phase 1 was 64.6%, and in phase 2 it was 35.4%. There was a significant decrease in the percentage of patients with VAP and CAUTI in phase 2 (after the intervention). The frequency of total DAI before the intervention was 60.8%, and after the intervention, it was 43.3%, with a significant decrease in total DAIs in phase 3 after the intervention; the incidence of DAIs in phase 1 (before the intervention) was 35.3/1000 device days, and in phase 3, it was 22.9/1000 device days (after the intervention). The incidence of VAP in phase 1 (before the intervention) was 68.2/1000 ventilator-days, and in phase 3, it was 47.4/1000 ventilator-days. The incidence of CLABSI in phase 1 (before the intervention) was 18.5/1000 catheter-days, and in phase 3, it was 12.9/1000 catheter-days. The incidence of CAUTI in phase 1 (before the intervention) was 24.9/1000 catheter-days, and in phase 3, it was 13.4/1000 catheter-days, with a decrease in DAI incidences after the intervention.

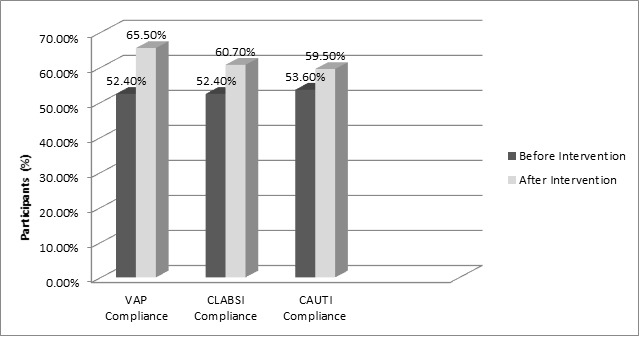

A higher risk of VAP, CLABSI, and CAUTI (RR: 1.4, 1.4, and 1.9, respectively) was reported before the intervention program compared with that reported after the intervention program (Table 1). The total mortality rate decreased from 24.2% to 16.7% of patients (Table 2). This study involved 70 HCWs before and after the intervention. The mean physician age was 28.5±3.1 years; most of them had less than 12 months of experience in the ICU. The mean age of the nurses was 29±4.2; most of them had less than 5 years of experience in the ICU. The compliance of HCWs for device care bundles varied between different items (Tables 3-5). The total compliance rates were as follows: 52.4% and 65.5% for the ventilator care bundle, 52.4% and 60.7% for the central catheter care bundle, and 53.6% and 59.5% for the urinary catheter insertion care bundle, with a significant increase in most items before and after the intervention, respectively (Figure 1).

Table 1. Incidence rate of device-associated infections in the intensive care unit before and after the intervention.

| Type of infection | Number of cases | Number of device-days | Incidence rate | RR* | RRR** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAP | |||||

| Before intervention | 68 | 997 | 68.2/1000 ventilator-days | 1.4 | 30.5 |

| After intervention | 46 | 970 | 47.4 1000 ventilator-days | ||

| CLABSI | |||||

| Before intervention | 22 | 1190 | 18.5/1000 catheter-days | 1.4 | 30.3 |

| After intervention | 15 | 1165 | 12.9/1000 catheter-days | ||

| CAUTI | |||||

| Before intervention | 31 | 1243 | 24.9/1000 catheter-days | 1.9 | 46.2 |

| After intervention | 17 | 1267 | 13.4/1000 catheter-days | ||

| Total DAIs | |||||

| Before intervention | 121 | 3430 | 35.3/1000 device days | 1.5 | 35.1 |

| After intervention | 78 | 3402 | 22.9/1000 device days | ||

CAUTI - catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI - central catheter-associated bloodstream infection; DAI - device-associated infection; VAP - ventilator-associated pneumonia.

a Rate per 1000 device-days: rates were calculated by dividing the number of specific DAIs by the number of device-days and multiplying the result by 1000.

Relative risk of device-associated infection = incidence of infection among those with no intervention \ incidence of infection among those with intervention.

Risk reduction ratio = incidence of infection among those with no intervention - incidence of infection among those with intervention / incidence of infection among those with no intervention *100

Table 2. Mortality rates for device-associated infections in the ICU before and after the intervention.

| Type of infection | Number of deaths | Number of patients | Mortality rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAP | |||

| Before intervention | 48 | 101 | 47.5/100 patients |

| After intervention | 36 | 100 | 36/100 patients |

| CLABSI | |||

| Before intervention | 13 | 114 | 11.4/100 patients |

| After intervention | 8 | 115 | 6.9/100 patients |

| CAUTI | |||

| Before intervention | 20 | 120 | 16.7/100 patients |

| After intervention | 12 | 120 | 10/100 patients |

| Total DAIs | |||

| Before intervention | 81 | 335 | 24.2/100 patients |

| After intervention | 56 | 335 | 16.7/100 patients |

CAUTI - catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI - central catheter-associated bloodstream infection; DAI - device-associated infection; VAP - ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Table 3. Level of healthcare workers’ adherence to VAP bundle.

| Necessity of ventilator insertion | Group A (101) | Group B (100) | Test | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | χ2 test | ||

| 74 | 73.3 | 88 | 88 | 6.974 | 0.008* | |

| Raise the cephalothorax 30 to 45 degrees | 74 | 73.3 | 86 | 86 | 5.017 | 0.025* |

| Use disinfectant solution for oral hygiene | 68 | 67.3 | 93 | 93 | 20.77 | 0.000* |

| Sterile water for humidification | 40 | 39.6 | 77 | 77 | 28.88 | 0.000* |

| Evaluate the necessity of sedative use | 55 | 54.5 | 70 | 70 | 5.164 | 0.023* |

| Administration of anti-stress ulcer | 58 | 57.4 | 73 | 73 | 5.37 | 0.02* |

| Administration of anti-deep vein thrombosis | 21 | 20.8 | 65 | 65 | 40.116 | 0.000* |

| Subglottic suction | 0 | 0 | 80 | 80 | Fisher exact | 0.000* |

| Keep the tracheostomy site clean and dry | 9 | 50 | 12 | 92.3 | Fisher exact | 0.019* |

| Total score X ± SD (max score 9) | 4 ± 1.3 | 6.4 ± 1.2 | T test 14.2 | 0.000* | ||

Table 4. Level of healthcare workers’ adherence to CLABSI bundle.

| Group A (114) | Group B (115) | Test | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | |||

| Evaluate the necessity of central catheter insertion | 26 | 22.8 | 72 | 62.6 | 37.046 | 0.000* |

| Adhere to hand hygiene standards | 69 | 60.5 | 86 | 74.8 | 5.32 | 0.021* |

| Clean and disinfect the skin before venipuncture | 58 | 50.9 | 76 | 66.1 | 5.456 | 0.02* |

| Use proper disinfectant | 76 | 66.7 | 99 | 86.1 | 11.982 | 0.001* |

| Record the maintenance date of long-term catheters | 64 | 56.1 | 80 | 69.6 | 4.421 | 0.036* |

| Replace gauze dressings every 48 h and change the transparent semipermeable membrane at least every seven days | 75 | 65.8 | 108 | 93.9 | 28.208 | 0.000* |

| Record the times of puncture for a catheter on the transparent dressing and sign it | 43 | 37.7 | 91 | 79.1 | 40.443 | 0.000* |

| Replace the dressing immediately when loosened, soiled, wet or damaged | 22 | 52.4 | 44 | 88 | 14.284 | 0.0002* |

| Total score X ± SD (max score 8) | 4.3±1.4 | 6.2±1.1 | 11.69 | 0.000* | ||

Table 5. Level of healthcare workers’ adherence to CAUTI bundle.

| Group A (120) | Group B (120) | Test | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | |||

| Assess the necessity of indwelling urethral catheter | 28 | 23.3 | 95 | 79.2 | 74.863 | 0.000* |

| Check the sterile urethral catheterization bag | 52 | 43.3 | 77 | 64.2 | 10.476 | 0.001* |

| Choose a urethral catheter of the right size and right material | 71 | 59.2 | 89 | 74.2 | 6.075 | 0.014* |

| Wear sterile gloves to implement urethral catheterization | 67 | 55.8 | 86 | 71.7 | 6.509 | 0.011* |

| Follow the principle of aseptic technique for an indwelling urethral catheter | 76 | 63.3 | 98 | 81.7 | 10.115 | 0.001* |

| Spread sterile towels to avoid contamination of the urethra | 61 | 50.8 | 79 | 65.8 | 5.554 | 0.018* |

| Use a disinfectant-wetted cotton ball to disinfect the urethral orifice and the surrounding skin | 87 | 72.5 | 100 | 83.3 | 4.092 | 0.043* |

| Fix the urine tube to avoid bending and secure the height of the urine collection bag below the bladder | 79 | 65.8 | 103 | 85.8 | 13.096 | 0.000* |

| Keep the urine drainage device airtight, unobstructed and complete and close the drainage tube during movement | 46 | 38.3 | 97 | 80.8 | 45.003 | 0.000* |

| Empty the urine collection bag in a timely manner | 51 | 42.5 | 67 | 55.8 | 4.268 | 0.039* |

| Follow the principle of aseptic operation when emptying the urine collection bag | 76 | 63.3 | 104 | 86.7 | 17.422 | 0.000* |

| No bladder irrigation or perfusion to prevent urinary tract infection | 67 | 55.8 | 84 | 70 | 5.161 | 0.023* |

| Clean and wash the urethral orifice daily | 88 | 73.3 | 112 | 93.3 | 17.28 | 0.000* |

| No replace a long-term indwelling urinary catheter | 65 | 54.2 | 89 | 74.2 | 10.438 | 0.001* |

| Replace the urinary catheter when it is obstructed or has prolapsed accidentally | 20 | 54 | 34 | 85 | 8.787 | 0.003* |

| Total score X ± SD (max score 15) | 8.3±2 | 11.5±1.5 | 13.96 | 0.000* | ||

Figure 1.

Compliance rate to VAP, CLABSI, and CAUTI bundle components in the emergency intensive care unit before and after the intervention

Intervention CAUTI - catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI - central line-associated bloodstream infection; VAP - ventilator-associated pneumonia.

There was a significant improvement in HCWs’ knowledge after the intervention, especially in hand hygiene, CAUTI bundle, and total knowledge, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Effect of health education on the total knowledge of preventive bundles among healthcare workers.

| Variables | Before intervention (n=70) | After intervention (n=70) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | ||

| VAP bundle | |||||

| Satisfactory | 43 | 61.4 | 59 | 84.3 | 0.002* |

| Not satisfactory | 27 | 38.6 | 11 | 15.7 | |

| CLABSI bundle | |||||

| Satisfactory | 30 | 42.9 | 47 | 67.1 | 0.003* |

| Not satisfactory | 40 | 57.1 | 23 | 32.9 | |

| CAUTI bundle | |||||

| Satisfactory | 37 | 52.9 | 55 | 78.6 | 0.002* |

| Not satisfactory | 33 | 47.1 | 15 | 21.4 | |

| Hand hygiene | |||||

| Satisfactory | 51 | 72.9 | 68 | 97.1 | <0.001* |

| Not satisfactory | 19 | 27.1 | 2 | 2.9 | |

| MDRO bundle | |||||

| Satisfactory | 35 | 50 | 48 | 68.6 | 0.04* |

| Not satisfactory | 35 | 50 | 22 | 31.4 | |

| Total knowledge | |||||

| Satisfactory | 16 | 22.9 | 52 | 74.3 | <0.001* |

| Not satisfactory | 54 | 77.1 | 18 | 25.7 | |

CAUTI - catheter-associated urinary tract infection; CLABSI - central catheter-associated bloodstream infection; DAI - device-associated infection; MDRO - multidrug resistant organism; VAP - ventilator-associated pneumonia. McNemar test was used in statistical analysis.

Significant difference at p<0.05

Discussion

The concept of the care bundle was originated by clinicians many years ago. The bundles work together as a consistent unit to ensure that all stages of care are consistently applied and properly documented. Failure of adherence to any single component makes the bundle compliance equal to zero. This approach inhibits preventable patient morbidity, resulting in a shorter length of hospital stay and better patient outcomes.8 A bundle compliance of 95% is the recommended best practice.9 In the current study, the results demonstrated an increased level of compliance among the three investigated bundles. The compliance rate increased from 52.4% to 65.5%, 52.4% to 60.7%, and from 53.6% to 59.5% in the ventilator, central line catheter, and urinary catheter care bundles, respectively. Different rates have been reported in earlier studies.10,11 Differences in the proper implementation of infection control programs are a major cause of such variations.12

In a previous European study, deficient materials (31%) and increased cost concerns (16.9%) in the ICU were considered as the main reasons for non-compliance with the VAP care bundle.13 In the current study, the items “using sterile water for humidification” and “problem of administration of anti-DVT” showed the lowest incompatibilities before the intervention. Regarding the first item, we emphasized the use of sterile water for humidification under infection control policies. We attributed the second item to the illnesses of the admitted cases. Many patients presented with multiple traumas, as well as internal and external bleeding. Other patients were admitted due to sepsis with coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia. Thereafter, the use of elastic compression stockings and intermittent pneumatic compression devices to prevent DVT were strictly instructed during the intervention phase in the educational sessions. A significant increase in compliance for these two items was observed in the third phase. Sustained compliance of over 90% with all elements of the CVC bundle can lead to the elimination of CLABSI in the ICU.14 Although the rates reported in this study were much lower, a statistically significant improvement was observed. With regard to single-item compliance, the items “Evaluate the necessity of central catheter insertion” and “Record the times of puncture for a catheter on the transparent dressing and sign it” showed the highest incompatibilities. This low compliance rate may be due to limited resources and infrastructure (non-working air conditioning with hot weather and skin infection), low nurse-to-patient ratio to apply the compliance item on time, increased workload, and the severity of cases. Exerted efforts to elevate compliance included the administrative director providing the necessary support to overcome these obstacles and problems.

Although it has been recommended not to use indwelling catheters unless necessary, and to consider alternatives to indwelling catheterization instead,15 the findings of single-item compliance in urinary catheter care bundle were not consistent with this recommendation. “Assess the necessity of indwelling urethral catheter” and “Keep the urine drainage device airtight, unobstructed and complete, and close the drainage tube during movement,” showed the highest incompatibility rate before the intervention. With education and the provision of resources, the compliance rate gradually increased. A significant 50% decrease in the CAUTI rate was reported earlier after the implementation of a closed system and daily cleansing of the perineal area as a part of basic elements for catheter care.16 In contrast, a study conducted in a rural Egyptian hospital showed a failure to improve CAUTI rates in the post-intervention phases of implementation owing to the reluctance of the working staff to implement and follow elements of the catheter care bundle.17

Based on the findings revealed in the first phase, the implementation of the educational program ran in two parallel directions: device care bundle compliance and knowledge of preventive bundles, and infection prevention among HCWs. This was reflected in the statistically significant decline in the DAI rates and mortality. Moreover, there was an improvement in the implementation of infection control measures, as retrieved from audit reports, after the application of the CCBEP. A comparable decrease in the VAP rate was documented in earlier studies. A previous study reported a drop in the VAP rate from 32.0 to 12.0 cases per 1000 ventilator-days after implementation of the bundle.18 According to a multicenter survey conducted by Pogorzelska et al.,19 an observed decrease in VAP was linked to only the ICUs that continually checked compliance and achieved higher compliance rates. They also observed that lower VAP rates were associated with having a full-time hospital epidemiologist.20

Although the decrease in the CLABSI rate was not statistically significant, it was clinically imperative. Several researches found the similar finding of decreasing CLABSI rate following bundle implementation (9.3-5.1 per 1000 central line days,21 and 9.4-5.5 per 1000 central line days).22 Another study demonstrated that after the post-implementation period, the CLABSI rate fell for the first three months, but increased thereafter, highlighting the importance of a regular continuous educational program to ensure the long-term impact of the bundle.23

We observed a significant decrease in the CAUTI rate. A quasi-experimental study reported concordance findings of reduction in the CAUTI rate by 50%.24 A similar finding of a 50% reduction in the mean monthly CAUTI rate in Philadelphia was revealed in a previous study.25 They further stressed the essential need of monitoring bundle compliance to achieve a higher reduction in CAUTI.

Regarding the mortality rate, there was no significant difference before and after the intervention. There might be no relationship or direct impact between device infection and death. Complications of surgeries or trauma may be the main factors that explain the high mortality in the investigated unit. Lower rates were reported in a Colombian study,26 which revealed that the crude unadjusted mortality attributable to DAIs was 16.9% for patients with VAP, 18.5% for patients with CLABSI, and 10.5% for patients with CAUTI. This can be explained by the difference in the type of investigated ICU and the severity of the enrolled cases. In the current study, the emergency ICU was considered the only referral ICU in our locality. It received the most severe and complicated cases in the entire governorate.

It is a challenge for most hospitals to enhance staff compliance with care bundles and hand hygiene; therefore, several interventions have been implemented, but none have been used for a long time to achieve the best reduction in morbidity and mortality and improve the quality of care. While the compliance of the HCWs was increased in the present study after the intervention (educational program), many studies have shown that just one intervention is not enough and does not effect the desired compliance.7,23 On the other hand, repeating the interventions on a regular basis may increase the compliance to grant basic infection control measures against DAIs.

Assessment of the knowledge of the HCWs after the program implementation in the current study showed a significant improvement, especially in hand hygiene, CAUTI bundle, and total knowledge. They were highly receptive and interested in acquiring knowledge when engaged in the guidelines. Incentives were offered to those who complied with the program.

Limitations of the study: The administrative system in our hospital implemented regular rotation of staff members, which made it difficult to select consistent study participants throughout the study period. However, they all nearly had the same educational background and expertise.

Conclusions

A significant improvement in the compliance of the ICU staff with device care bundles was reported. A decrease in the incidence of DAIs was described. CCBEP is recommended as a part of the ICU protocols. To achieve a better reduction in DAIs, stakeholders must be regularly educated and bundle compliance must be evaluated with regular audits.

Acknowledgments:

The authors dedicate their sincere appreciation to the participating HCWs for their cooperation and help in facilitating data collection.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions statement: EMN, HAO, MMT, and RHE conceived and designed the study. EMN, RHE, and MMZ contributed to the literature search. EMN, and KMA contributed to data collection. MMZ contributed to data analysis. MMZ, EMN, and RHE contributed to data interpretation. MMZ, EMN, and RHE contributed to writing the report. All authors contributed to revising the report. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: All authors – none to declare.

Funding: None to declare.

References

- 1.Kübler A, Duszynska W, Rosenthal VD, et al. Device-associated infection rates and extra length of stay in an intensive care unit of a university hospital in Wroclaw, Poland: International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium’s (INICC) findings. J Crit Care. 2012;27(105):e5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao F, Wu YY, Zou JN, et al. Impact of a bundle on prevention and control of healthcare associated infections in intensive care unit. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2015;35:283–90. doi: 10.1007/s11596-015-1425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dilek A, Ülger F, Esen Ş,Acar M, Leblebicioğlu H, Rosenthal VD. Impact of education and process surveillance on device-associated health care-associated infection rates in a Turkish ICU: findings of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) Balkan Med J. 2012;29:88–92. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2011.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Overview. Jan, 2016. [Accessed on: 30 March 2020]. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/validation/2016/pcsmanual_2016.pdf.

- 5.Sodhi K, Shrivastava A, Arya M, Kumar M. Knowledge of infection control practices among intensive care nurses in a tertiary care hospital. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:269–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rasslan O, Seliem ZS, Ghazi IA, et al. Device-associated infection rates in adult and pediatric intensive care units of hospitals in Egypt. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) findings. J Infect Public Health. 2012;5:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Sokkary RH, Negm EM, Othman HA, Tawfeek MM, Metwally WS. Stewardship actions for device associated infections: an intervention study in the emergency intensive care unit. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1927–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke FJ, Holmes AH. The missing care bundle: antibiotic prescribing in hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;30:25–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prakash SS, Rajshekar D, Cherian A, Sastry AS. Care bundle approach to reduce device-associated infections in a tertiary care teaching hospital, South India. J Lab Physicians. 2017;9:273–8. doi: 10.4103/JLP.JLP_162_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris AC, Hay AW, Swann DG, et al. Reducing ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care: impact of implementing a care bundle. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:2218–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227d52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuya EY, Dick AW, Herzig CT, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M, Larson EL, Stone PW. Central line-associated bloodstream infection reduction and bundle compliance in intensive care units: a national study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:805–10. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azzab MM, El-Sokkary RH, Tawfeek MM, Gebriel MG. Multidrug-resistant bacteria among patients with ventilator associated pneumonia in an emergency intensive care unit, Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;22:894–903. doi: 10.26719/2016.22.12.894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caserta RA, Marra AR, Durão MS, et al. A program for sustained improvement in preventing ventilator associated pneumonia in an intensive care setting. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meddings J, Rogers MA, Krein SL, Fakih MG, Olmsted RN, Saint S. Reducing unnecessary urinary catheter use and other strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infection: an integrative review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:277–89. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchida T, Makimoto K, Ohsako S, et al. Relationship between catheter care and catheter-associated urinary tract infection at Japanese general hospitals: a prospective observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008;45:352–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amine AE, Helal MO, Bakr WM. Evaluation of an intervention program to prevent hospital-acquired catheter-associated urinary tract infections in an ICU in a rural Egypt hospital. GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2014;9:Doc15. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pogorzelska M, Stone PW, Furuya EY, et al. Impact of the ventilator bundle on ventilator-associated pneumonia in Intensive Care Unit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23:538–44. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzr049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menegueti MG, Ardison KM, Bellissimo-Rodrigues F, et al. The impact of implementation of bundle to reduce catheter-related bloodstream infection rates. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:857–61. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2314w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren DK, Zack JE, Mayfield JL, et al. The effect of an education program on the incidence of central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection in a medical ICU. Chest. 2004;126:1612–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.5.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longmate AG, Ellis KS, Boyle L, et al. Elimination of central-venous-catheter-related bloodstream infections from the intensive care unit. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:174–80. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yilmaz G, Caylan R, Aydin K, Topbas M, Koksal I. Effect of education on the rate of and the understanding of risk factors for intravascular catheter-related infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:689–94. doi: 10.1086/517976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furuya EY, Dick A, Perencevich EN, Pogorzelska M, Goldmann D, Stone PW. Central line bundle implementation in US intensive care units and impact on bloodstream infections. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis KF, Colebaugh AM, Eithun BL, et al. Reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: a quality-improvement initiative. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e857–64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bird D, Zambuto A, O’Donnell C, et al. Adherence to ventilator-associated pneumonia bundle and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia in the surgical intensive care unit. Arch Surg. 2010;145:465–70. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raskind CH, Worley S, Vinski J, Goldfarb J. Hand hygiene compliance rates after an educational intervention in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:1096–8. doi: 10.1086/519933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittet D, Simon A, Hugonnet S, Pessoa-Silva CL, Sauvan V, Perneger TV. Hand hygiene among physicians: performance, beliefs, and perceptions. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:1–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]