Abstract

The inhabitants of Tunants and Yahuahua face water supply problems in terms of quantity and quality, leading to socio-environmental and health impacts in the areas. The objective of this research, therefore, is to determine the technical and economic feasibility of a proposal for a rainwater harvesting and treatment system for human consumption in the native communities. For the technical feasibility, monthly water demand per family was compared with the amount of water collected in the rainy and dry seasons. In addition, 16 physical, chemical, and microbiological parameters were evaluated at the inlet and outlet of the water system. The economic feasibility was determined by the initial investment and maintenance of the systems; with the benefits, we obtained the net present social value (NPSV), social internal rate of return (SIRR), and cost-effectiveness (CE). Technically, oxygenation and chlorination in the storage tanks allowed for water quality in physical, chemical, and microbiological aspects, according to the D.S. N° 031-2010-SA standard, in all cases. Finally, with an initial investment of S/2,600 and S/70.00 for annual maintenance of the system, it is possible to supply up to six people per family with an average daily consumption of 32.5 L per person. It is suggested that the system be used at scale in the context of native communities in north-eastern Peru.

1. Introduction

Safe drinking water and basic sanitation must be available, accessible, safe, acceptable, and affordable for the entire population [1]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends at least 50 L per person per day of water to ensure basic hygiene and nutrition [2]. However, around the world, people die from lack of quality water, especially in rural areas (native and peasant communities) [3]. For instance, Urakusa native community in the Amazonas region (NW Peru) has no basic sanitation services (water supply for drinking and domestic use) and relies on communal silos and latrines for disposal of human waste [4]. In Amazonas, unfortunately, the province of Condorcanqui has the highest percentage of lack of both services (92.3%) [5].

The lack of basic services in rural areas (such as water), together with economic and climatic factors, directly influence chronic child malnutrition and anaemia [6]. The provision of safe drinking water for rural communities must, therefore, be a public priority. However, public projects are unsustainable due to dispersed housing, requiring costly distribution networks [7]. In this situation, rainwater harvesting, storage, and utilisation systems are of paramount importance for those populations that still do not have access to water or have shortages [8].

Thus, rainwater harvesting and rainwater harvesting systems have become an economical and ecological alternative [9]; yet their use has not become widespread due to their long financial return periods [10]. However, there are studies that demonstrate the feasibility of these systems. For example, in Ireland, they focused on treating rainwater to address water depletion due to massive population growth [11, 12]. In Spain, a feasible predictive model was developed for rainwater harvesting in rural communities [13]. In Sydney, average annual water savings are related to annual rainfall and a positive cost/benefit ratio of rainwater storage tanks [14]. In Latin America, because of conditions from northern Chile, Peru, and parts of Ecuador, rainwater harvesting is also feasible [15]. Rainwater storage depends on the size of the tanks and the area, for which technical and economic considerations must be taken into account when choosing the type of storage system [8].

The quality of rainwater must be analysed based on urban areas, physical, chemical, and microbiological factors, which depend on various components suspended in the air [16]. Population growth, forest burning, and industrial expansion cause chemical modification of rainwater [17]. In that sense, rainwater harvesting and treatment is what determines its use, depending on its ability to eliminate enterobacteria, viruses, protozoan cysts, and bacterial spores that can cause disease [18]. Global health depends not only on the quantity of water supplied but also on the water quality; a quarter of the world's population suffers from water-related illnesses [19]. In Urakusa, rainwater quality is poorly prioritised because of the lack of sanitation services [4]. In this sense, rainwater may be used to avoid the use of water from springs and streams, in order to preserve them as they are threatened and highly polluted by human activities [19, 20]. Rainwater treatment has only sense if it is done properly; therefore, the most widely used disinfection method (as part of the treatment) is chlorination due to its easy accessibility and application, as well as its high oxidant capacity expressed in the reduction of organic matter [21].

The cost-effectiveness of rainwater harvesting systems needs to be assessed in order to determine the systems' effectiveness at the user level. The economic analysis allows determining the feasibility of production from rainwater [22, 23]. Water is one of the most important and scarce commodities available to people worldwide, and Peru is no exception in this respect. Many populations are forced to drink from sources whose quality is outside the regulations (D.S. N° 031-2010-SA) leading to health risks for children and adults [24]. In rural Peru, people lack access to safe drinking water; in fact, only 20.0% of the population have access to this service through the public water network [25]. One of the goals of the development objectives (SDGs) is to achieve universal access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene [26], and Peru is a party to these agreements.

Little have rainwater harvesting projects in native communities been studied, as well as socialisation and prior training for maintenance of the systems implemented [27]. Therefore, it is necessary to implement rainwater harvesting systems in rural areas where access to drinking water is a neglected asset [19]. Based on the above, this research aims, for the first time, to technically and economically validate the rainwater harvesting and treatment system designed for mass use in two native communities (Tunants and Yahuahua) in the Amazonas region (NW Peru).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Characterisation of Target Beneficiaries

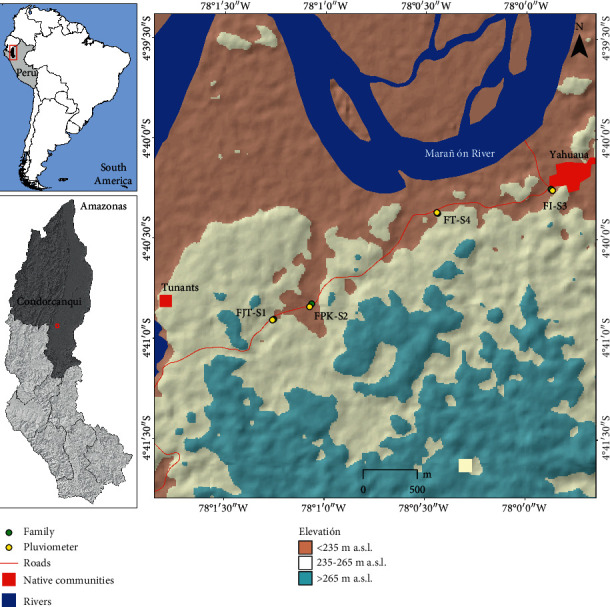

The study is located in two native communities, inhabited by Awajún and Wampis peoples (Tunants and Yahuahua), district of Nieva, province of Condorcanqui in the jungle of NW Peru (Figure 1). They are located at an altitude of 196 meters above sea level and an average temperature of 26°C and has an average annual rainfall of 3,121 mm [28]. The communities were created 22 years ago and have a reported population of 217 people in the 2017 census [29].

Figure 1.

Location map.

The province of Condorcanqui faces transportation barriers due to demographic dispersion, as well as it lacks access to basic needs, which include, among others, food, drinking water, and drainage [30]. Their economy is subsistence-based, with land (between 0.5 and 1 ha) dedicated to the cultivation of cassava, bananas, and maize [31]. The characterisation of beneficiaries, on which the systems were designed, was based on interviews aimed at obtaining general data on the population, dwellings, water consumption habits, and evaluating the acceptance level of rainwater harvesting and treatment systems installed in these two native communities.

2.2. System Design and Installation

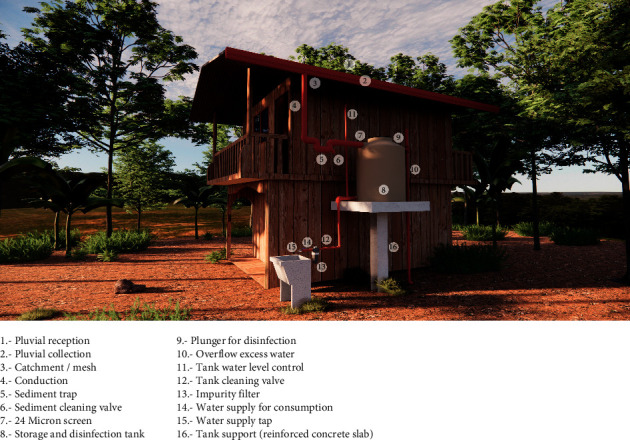

Four stratus rain gauge model 6330 were installed, one in each system (two in each native community). The construction area to set up the systems was determined, ensuring it meets the minimum conditions for the area (place and area of the systems) and the number of users. For the tank construction, three main materials were used: iron, cement, and pipes (PVC). The supporting structure of the tank was built with a mixture of concrete and cement, reinforced with corrugated steel. The design consists of 16 parts indicated in Figure 2, which include a footing of 1 m × 1 m, a central column of section 25 cm × 30 cm and support slab of 1.40 m × 1.40 m, and PVC pipes of 6 and a polypropylene storage tank of 1,100 L with protection against ultraviolet rays (Figure 2). The characteristics of the systems were the same in all four dwellings, except for the size of the column, which was subject to the height of the dwelling. Roof coverings of all dwellings were of galvanised calamine.

Figure 2.

Design of the rainwater harvesting system.

2.3. Technical Feasibility Determination

To determine the technical feasibility, physical, chemical, and microbiological factors were determined by sampling water, at the inlet and outlet of the systems during three months of the rainy season (December 2019 and January and February 2020) and two months of the dry season (September and October 2020). Sample collection, storage, and transfer, as well as laboratory analysis, were performed according to APHA, AWWA, and WEF [32]. In the rainy season, 264 physicochemical and 72 microbiological samples were analysed, and in the dry season, 64 physicochemical and 32 microbiological samples were analysed. The microbiological parameters were reduced in the dry season, due to the scarce economic resources allocated and the difficult access to the native communities, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this was not a limitation to continue with the study, given that efforts were made to analyse the TC and CF; the only parameter not taken in the dry season was Escherichia coli.

Data collection for pH was in situ, with a Hanna multiparametric water meter model HI 98194, while samples were collected in transparent plastic containers to determine the physicochemical parameters of electrical conductivity (EC), turbidity, total dissolved solids (TDS), total suspended solids (TSS), alkalinity, hardness, nitrates, nitrites, phosphates, sulphates, aluminium, copper, and zinc. Samples were collected for microbiological analysis of total coliforms, faecal coliforms, and E. coli in properly sterilised glass bottles with a capacity of 500 ml. They were transported in a cooler with dry ice at a temperature of 5°C. Parameters were analysed at the Water and Soil Laboratory of the Research Institute for Sustainable Development of Ceja de Selva (INDES-CES) of the National University Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza (UNTRM). Water quality calibration was carried out through chlorination for disinfection at the outlet of the system [33], with commercial bleach in a mechanical way, through the application of a graduated syringe; residual chlorine measurements were carried out with a Hanna HI729 model colorimeter. Likewise, before each sampling, the pH was measured, and the application of potassium hydroxide (KOH) tablets was determined accordingly.

2.4. Harvested Water and Projected Catchment Area of the Roof for Water Supply

The volume of rainwater captured in the systems (Vr) was determined by the catchment area of the roof (CR, variable according to the dwelling), the type of roof material (galvanised metal sheet), and its runoff coefficient (Rc, 0.9) [34]. Based on the water harvested, a projection was made of the ideal area to supply water.

| (1) |

2.5. Monthly Water Demand

The monthly water demand per household (Wdh) was assessed. For this, the average amount of water consumption per person (Wcp, 30 L/day [35]), the number of individuals or beneficiaries of the system (Nu), and the period of consumption analysed (Nd, 29, 30, or 31 depending on the month) were identified. The number of individuals per household was obtained through the application of socio-economic surveys [36]. The priorities or activities taken into account were the demand for water at the individual level, including food preparation, personal hygiene, and cleaning of personal items and objects [37].

| (2) |

2.6. Economic Feasibility Determination

Economic feasibility was determined based on cost-effectiveness, according to geographical aspects (the location of the dwellings and roof area) and costs of water system installation and maintenance. For this, the amount of water supply to dwellings was assessed. The volume of rainwater captured by the roofs (supply) was calculated and then weighed against the members' water needs (demand) [38]. The costs and expenses of the inputs per unit and on average, including the design plans, were taken into account. Inputs and services of the households were also valued.

2.7. Economic Viability

To determine the economic viability, a socio-economic evaluation of rainwater harvesting projects was conducted to assess the current situation, current supply, current demand, and problem description [39]. Benefit-cost analysis of the systems installed in the native communities by evaluating the total cost of the system divided into three phases as follows.

2.8. Preinvestment and Investment Phase

In the preinvestment phase, the conditioning of the systems and labour costs were taken into account. In the investment phase, the construction of the systems was evaluated, taking into account the components of the catchment area, conduction, storage, filtration, potabilisation, and distribution of rainwater. The opportunity cost of terrain was also considered, as the tank installation requires a large area.

2.9. Postinvestment Phase

In this phase, the costs of operation and maintenance were determined, estimating the timescale it should be done.

Cost-benefit: cost-benefit analysis is based on Jianbing's formula [40]:

| (3) |

where AVB is the present value of rainwater benefits, Inv is the investment, and PVC is the present value of costs. The net present social value (NPSV) was carried out to indicate the profitability of the systems, and the projected project horizon was 5 years.

| (4) |

where CFt is the year t cash flow, t is the number of time periods (number of years), r means 10% social discount rate, and n is the number of years in assessment horizon minus one. NPSV > 0 indicates that the investment will generate returns. NPSV = 0 indicates that investment project will neither generate profits nor losses. NPSV < 0 indicates that the investment project should be postponed.

2.10. Social Internal Rate of Return (SIRR)

It was calculated using the following formula:

| (5) |

where Ct: period t cash flow, I0: initial investment (t = 0), n: number of time periods, and t: time period.

2.11. Cost-Effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness analysis of a social-economic analysis and nonproject evaluation costs were measured as economic costs, and the results were valued as units of effectiveness [41], assuming that families do not have water, based on the question “How much would a litre of water cost?” and the number of times they carry water, as well as the demand for water per family. A comparison was made between the costs incurred by not having water versus the situation of the satisfaction of having water in the training and treatment systems. The costs were identified in terms of the number of water hauls and the loss of productivity from hauling water (the daily labour cost was taken into account in the internal regulations of the native community of Urakusa). formulas (6) and (7) were used to calculate the daily and annual costs.

2.12. Cost-Effectiveness Calculation of Carrying Water from the Stream (Daily)

| (6) |

where CE = cost-effectiveness, Ta = water carrying time in hours per day, Jl = working hours per day, and Cj = cost of working time per day.

2.13. Cost-Effectiveness Calculation of Carrying Water from the Stream (Annual)

| (7) |

where Can = annual cost of water without catchment system, Cad = daily water carrying cost, and Da = number of days per year.

2.14. Comparing Projected Costs

We made a comparison for projected costs between the proposed tank water harvesting system (situation with project) versus the tankless water harvesting system, as this is the way the community currently uses the water (situation without project). A 5-year evaluation was carried out, based on the calculation of the annual for each case, including the increase in the number of families (85 families by 2021–2026). The projection (2021–2026) was also calculated using stormwater treatment information and comparing these costs. Additionally, the costs of installing the system with the proposed tank water harvesting system (concrete-based materials) and an installation alternative for families using local materials (materials using native wood) were also described.

We applied a nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test to identify if there are significant differences between the dry and rainy seasons, using the Minitab 17.1 software (Spanish version).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Beneficiaries

In the selected households of a native community in Amazonas, there are a maximum of 6 family members using water. While for Biswas and Mandal [42], in a remote and rural area of Khulna (Bangladesh), there were a maximum of 4 members, meeting their domestic use throughout the year. Of the selected families, 50% are engaged in agriculture (maize, banana, and cassava cultivation) with an average size of 1 ha per family. They are also engaged in other casual work (day labour) at a daily rate of 40 soles, an amount established by internal rules (apu) within the community.

In Tunants and Yahuahua, the inhabitants draw their water from nearby streams or ponds (at an average distance of 75 minutes round journey). Nevertheless, these direct water sources are contaminated by anthropogenic and natural sources [20]. Here, water is commonly carried in gallons and 10 L buckets for daytime supply (Figure 3(a)). However, for their personal hygiene, they usually go directly to the stream (Figure 3(b)). The families also store the water in large containers (between 100 and 1,000 L capacity) to ensure the particles can settle during storage. The water is always boiled before drinking, as the water is contaminated by different types of pollutants, for example, washing powder and faecal dropping from domestic animals. The main reason for nonconstruction of a rainwater harvesting system is the economic factor.

Figure 3.

(a) Common water supply features and (b) villagers having their personal hygiene in the stream.

3.2. Rainwater Harvesting and Treatment System

3.2.1. Monthly Rainfall

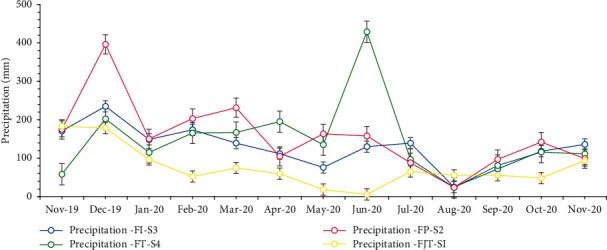

Studies indicate that the annual rainfall in the province of Condorcanqui is between 1,200 and 1,800 mm [27]. The data collected from the rain gauges installed in the study area showed rainfall of up to 396.2 mm in November (Pluviometer-FP-S2) and 429 mm in June (Pluviometer-FT-S4) corresponding to Tunants and Yahuahua, respectively (Figure 4). The lowest rainfall occurred in August (24 mm), corresponding to the Yahuhua area, and 5.76 mm for Tunants. Consequently, rainfall in both communities was consistent and was sufficient capacity for the water catchment systems.

Figure 4.

Rainfall evolution: FI-S3 = rain gauge (system three), FT-S4 = rain gauge (system four), FP-S2 = rain gauge (system two), and FJT-SI = rain gauge (system one).

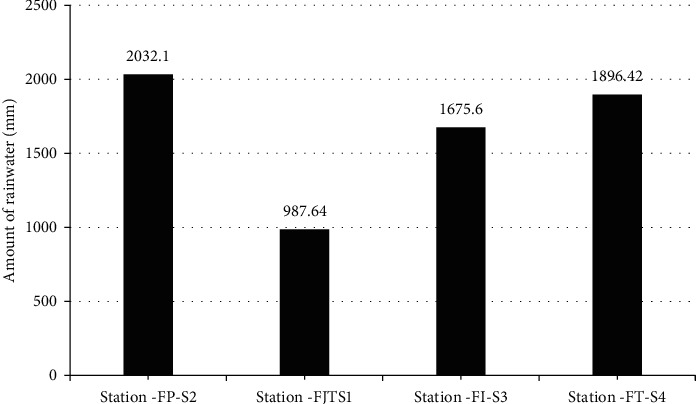

Annual rainfall variations at the stations showed a maximum of 2,032.1 mm and a minimum of 987.64 mm (Figure 5). The National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology of Peru (SENAMHI) shows rainfall values between 1,376.4 and 2,227.8 mm per year at the level of the Nieva district. The values of the installed rain gauges demonstrated the tendencies with respect to the values given by SENAMHI, given the distance of the station from the installed systems.

Figure 5.

Total annual rainfall reported from rain gauges.

3.3. Technical Feasibility

3.3.1. Amount of Rainwater Collected

The amount of rainwater collected in the systems was not homogeneous (Table 1). In the FPK-S2 family system, there was the highest amount of water collected, with a maximum of 14,263.2 L (December) and a minimum of 311.04 L (June). Rainfall shortage was pronounced in the summer season, during the months of June, July, and August. The amount of rainwater collected is proportional to the area of the roofs. And rainfall is linked to the seasons of the year [15].

Table 1.

Monthly quantity of water offered.

| Month | Monthly water catchment (L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPK-S2 (RA = 40 m2) | FJT-S1 (RA = 60 m2) | FT-S4 (RA = 40 m2) | FI-S3 (RA = 50 m2) | |

| November 2019 | 6,296.4 | 9,877.68 | 4,834.8 | 7,672.5 |

| December 2019 | 14,263.2 | 9,637.92 | 7,290 | 10,575 |

| January 2020 | 5,414.4 | 5,214.24 | 4,140 | 6,705 |

| February 2020 | 7,315.2 | 5,522.58 | 5,962.32 | 7,830 |

| March 2020 | 8,330.4 | 4,028.4 | 6,012 | 6,255 |

| April 2020 | 3,772.8 | 3,218.94 | 7,020 | 5,031 |

| May 2020 | 5,882.4 | 988.2 | 4,860 | 3,420 |

| June 2020 | 5,684.4 | 311.04 | 9,612 | 5,850 |

| July 2020 | 3,168 | 3,528.9 | 3,492 | 6,255 |

| August 2020 | 864 | 2,995.38 | 864 | 1,125 |

| September 2020 | 3,481.2 | 3,008.88 | 2,916 | 3,240 |

| October 2020 | 5,119.2 | 2,613.6 | 4,176 | 5,323.5 |

| November 2020 | 3,564 | 5,076 | 3,996 | 6,120 |

| Total | 73,155.6 | 56,021.76 | 65,175.12 | 75,402 |

RA = roof area.

3.4. Monthly Household Water Demand

Water distribution is unequal; in fact, the poorest areas use about 15 L of water per day and is, of course, influenced by the economic factor [43]. In Mexico, every person has the right to access disposal and sanitation of water equivalent to 30 L per person per day; however, it is still lower than recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO), suggesting at least 50 L of water per person per day to ensure basic hygiene and nutrition [2]. Household water consumption in the native communities in this research was 71,280 L/year (Table 2) and consumption per person was 32.55 L/day, for an average number of 6 users.

Table 2.

Monthly water demand per household.

| Month | d/m | De L/F | System (FI-S3) | System (FJT-SI) | System (FPK-S2) | System (FT-S4) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L (L) | Vol. maximum tank/day (L) | Rez (L) | Vol. maximum tank/day (L) | L (L) | Vol. maximum tank/day (L) | L (L) | Vol. maximum tank/day (L) | |||

| November 2019 | 30 | 5,400 | 2,273 | 76 | 4,478 | 149 | 896 | 30 | −565 | −19 |

| December 2019 | 31 | 5,580 | 4,995 | 161 | 4,058 | 275 | −4,684 | 309 | −6,145 | 37 |

| January 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | 1,125 | 36 | −366 | 264 | 4,000 | 304 | −4,435 | −10 |

| February 2020 | 29 | 5,220 | 2,610 | 90 | 303 | 292 | 4,194 | 397 | −5,515 | 15 |

| March 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | 675 | 22 | −1,552 | 223 | 5,929 | 460 | −5,133 | 28 |

| April 2020 | 30 | 5,400 | −369 | −12 | −2,181 | 158 | 8,860 | 421 | −4,521 | 83 |

| May 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | −2,160 | −70 | −4,592 | 5 | 7,052 | 417 | −3,081 | 57 |

| June 2020 | 30 | 5,400 | 450 | 15 | −5,089 | −165 | 7,535 | 441 | −3,621 | 200 |

| July 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | 675 | 22 | −2,051 | −226 | 7,639 | 349 | 411 | 126 |

| August 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | −4,455 | −144 | −2,585 | −309 | 5,227 | 196 | −1,677 | −26 |

| September 2020 | 30 | 5,400 | −2,160 | −72 | −2,391 | −399 | 691 | 139 | −6,213 | −110 |

| October 2020 | 31 | 5,580 | −257 | −8 | −2,966 | −482 | −1,408 | 120 | −8,877 | −152 |

| November 2020 | 30 | 5,400 | 720 | 24 | −324 | −509 | −1,688 | 63 | −10,101 | −203 |

| Total | 396 | 71,280 | 4,122 | 140 | −15,258 | −722 | 44,244 | 3,645 | −59,473 | 27 |

d/m = Day of month, L = lag, De L/F = water demand litres/family, and (L) = litres.

The annual backlog for the FPK-S2 system was 44,244 L. Therefore, it is clear that the water backlog is higher than the demand. The implementation of water recycling systems is proposed, as the water demand is higher than the normative allocation of 30 L per person per day [24]. The backlog in the FI-S3 system was 4,122 L; although the annual backlog is positive, August, September, and October were the most critical period with negative values (−4,455, −2,160, and −257 L, respectively), months in which food preparation is the exclusive priority. In the FJT-SI and FT-S4 systems, the annual lag was −15,258 and −59,473 L. Water deficit was observed in almost all months (Table 2); generally, these negative values are associated with water use in laundry and showering (in months where the lag is negative, water use should be prioritised). For water supply, each month water use should be prioritised, and larger sheds should be installed to capture more water. The 1,100 L storage systems tank was sufficient to supply all of the families' needs for a week, assuming no rain. However, if they only prioritise water for food consumption, it can supply up to 15 days. It was determined that during the rainy months, storage tanks with a maximum capacity of 460 L are needed; therefore, the chosen tanks are the 1,100 L tanks; this is justified because the rains are constant, and there are days when even for the FI-S3 system; only a 15.00 L container is needed to supply water to the family.

3.5. Projections of Areas for Rainwater Catchment

The amount of water collected is dependent on the catchment area of the sheds, so roof area measurements have been projected based on water deficit for seasonal low rainfall. Therefore, the average area for installing future investment projects is 89 m2 (Table 3). With 89 m2 modules, an annual collection of up to 165,884.4 L can be achieved. Unfortunately, the investment in rainwater harvesting may be very costly, making it impossible to install due to economic reasons, thus declining the system's affordability [44]. As such, governments have an obligation to guarantee access to a sufficient quantity of safe drinking water for personal and domestic use [45].

Table 3.

Rainwater harvesting projections of suitable catchment areas.

| Dwellings | Dwellings (NP) | Dwellings (P) | Investment/future | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area of dwellings (m2) | Rainwater harvesting (L/year) | Projected area (m2) | Rainwater harvesting (L/year) | Recommended area (m2) | |

| FPK-S2 | 40 | 73,156 | 70 | 128,022 | 89 |

| FJT-S1 | 60 | 56,022 | 85 | 79,364 | |

| FT-S4 | 40 | 65,175 | 91 | 148,273 | |

| FI-S3 | 50 | 75,402 | 110 | 165,884.4 | |

Nonprojected dwellings (NP) and projected dwelling (P).

3.6. Physicochemical Parameters

The physicochemical parameters (Table 4) for the FPK-S2 and FJT-S1 systems were within the drinking water quality regulations [24] in both periods. In contrast, in the FT-S4 and FI-S3 systems, the parameter aluminium (Al) was the only one that exceeded water quality regulations. The high presence of aluminium may have been influenced by calamine roofs, as well as the combustion of fossil fuels, crude oil, and sources of vehicular traffic close to the installation of the systems [46, 47]. Different pollutants can reach water by wind speed, wind direction, temperature, and the degree of atmospheric stability [48, 49]. In this respect, the quality of rainwater is also influenced by the type of system design [50]. Zinc levels were below the maximum permissible limits (3.0 mg Zn/L) during the rainy season. However, Chubaka et al. [51] found zinc concentrations above 3.0 ppm and copper concentrations above 2.69 ppm. It is possible that this metal is associated with the corrosive action of calamine, such as ultraviolet solar radiation that can damage calamine sheets or structures, causing tiny metal microparticles and paint on the surfaces.

Table 4.

Rainwater quality (mean ± standard deviation) based on monthly evaluation during three months of the rainy season (December 2019 and January and February 2020).

| Systems samples (inlet/outlet) | pH (units) | Turbidity (NTU) | TDS (mg/L) | TSS (mg/L) | Alkalinity (mg/L; CaCO3) | Hardness (mg/L; CaCO3) | Nitrate (mg/L; NO3) | Nitrite (mg/L; NO3) | Aluminium (mg/L) | Copper mg/L | Zinc mg/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPK-S2 (inlet) | 6.77 ± 0.08 | 0.87 ± 0.76 | 22.20 ± 32.31 | 43.91 ± 58.10 | 36.57 ± 24.13 | 12.81 ± 1.43 | 1.01 ± 1.12 | 0.27 ± 0.46 | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 1.70 ± 2.45 |

| FPK-S2 (outlet) | 6.84 ± 0.16 | 0.53 ± 0.55 | 12.56 ± 16.41 | 52.83 ± 68.14 | 11.13 ± 0.68 | 13.09 ± 2.76 | 0.27 ± 0.46 | 0.17 ± 0.29 | 0.07 ± 0.11 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.65 ± 0.69 |

| FJT-S1 (inlet) | 6.80 ± 0.16 | 1.27 ± 1.78 | 6.47 ± 4.10 | 28.83 ± 22.23 | 14.71 ± 5.89 | 14.05 ± 4.69 | 2.25 ± 2.73 | 0.13 ± 0.23 | 0.07 ± 0.12 | 0.02 ± 0.03 | 2.09 ± 1.99 |

| FJT-S1 (outlet) | 6.78 ± 0.15 | 0.70 ± 0.75 | 4.20 ± 0.96 | 17.70 ± 20.36 | 14.71 ± 5.89 | 11.16 ± 1.24 | 3.31 ± 5.73 | 0 | 0.08 ± 0.12 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.48 ± 0.78 |

| FT-S4 (inlet) | 6.63 ± 0.24 | 0.80 ± 0.72 | 4.87 ± 1.01 | 26.60 ± 24.00 | 22.27 ± 1.36 | 11.99 ± 1.89 | 1.75 ± 1.59 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.12∗ ± 0.14 | 0.01 ± 00 | 0.84 ± 0.74 |

| FT-S4 (outlet) | 6.77 ± 0.16 | 3.33 ± 4.69 | 4.40 ± 1.26 | 21.33 ± 10.07 | 18.69 ± 6.98 | 12.81 ± 1.43 | 0.77 ± 0.75 | 0 | 0.07 ± 0.13 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.66 |

| FI-S3 (inlet) | 7.09 ± 0.68 | 0.76 ± 0.80 | 9.30 ± 5.72 | 27.67 ± 20.03 | 18.69 ± 6.98 | 14.47 ± 5.8 | 3.60 ± 4.71 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.13 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 2.18 ± 2.55 |

| FI-S3 (outlet) | 6.97 ± 0.27 | 0.65 ± 0.71 | 4.70 ± 1.73 | 22.85 ± 18.78 | 14.71 ± 5.89 | 10.75 ± 4.35 | 1.00 ± 0.94 | 0.00 ± 0.01 | 0.11∗ ± 0.20 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 1.03 ± 0.89 |

| D.S. N° 031-2010-SA | 6.5–8.5 | 5 NTU | 1,000 mg/L | nc | nc | 500 mg CaCO3/L | 5,000 mg NO3/L | 3,00 mg NO2/L short exposure | 0.2 mg Al/L | 2 mg Cu/L | 3.0 mg Zn/L |

∗ Noncompliant; nc = not contemplated in the Peruvian standard.

The maximum amount of nitrate (NO3) was 3.60 ppm in the FI-S3 system. Nitrate concentration above 50 ppm in water is detrimental to health, and infants may be most affected due to the formation of methemoglobinemia [52].

Rainwater quality varies according to the type of roof and directly influences the parameters of hardness, alkalinity, and turbidity [53]. The maximum turbidity was 1.27 NTU, which is within the Peruvian standard, but it could be due to the number of dry days preceding a rainy event [54]. With respect to total solids, González [54] found parameters between 79 ppm and 94 ppm; for this reason, continuous maintenance of the systems is recommended to reduce the TDS 22.20 mg/L, in the FPK-S2 system. These high and discontinuous values are observed due to the lack of cleanliness of the roof. This dynamic is typical of indigenous communities. TSS varies between 17.60 and 52.83 mg/L. Other studies showed results for total suspended solids ranging from 3 to 304 mg/L. Alkalinity values ranged from 11.13 to 36.57 mg/L CaCO3, and all values were very low and acceptable. According to the literature [55, 56], alkalinity is a very important parameter for drinking water, as it buffers rapid pH changes.

The physicochemical results for the low-water season are shown in Table 5, where zinc problems are evident for the FI-S3 and FT-S4 family system, not meeting the standard (D.S. N° 031-2010-SA). However, these heavy metal values in rainwater are lower than values in river water, obtained by the regional government of Amazonas in the community of Kusu Kubaim, in the Nieva district, with high heavy metal values (0.45 and 0.442, respectively) [57]. In the community of Kigkis, in the Nieva district, water from the distribution network showed aluminium (0.527) and iron (0.482) above acceptable limits [57]. Moreover, in the Chiangos community, in the Nieva district, high values of aluminium (0.2062) were found. Aluminium in all systems ranged from minimum and maximum values of 0.2–0.67 mg Al/L, respectively. The problems of heavy metals persist for both periods; technical and economical measures such as oxygenation of the storage tanks should be taken to achieve precipitation of both aluminium and zinc. This is left as a proposal:

Precipitate aluminium from water. Water is oxygenated in an artisanal way to react with O−2 and precipitate as aluminium hydroxide (Al (OH)3↓)

Al+3 + O−2 ⟶ Al O3 + H2O ⟶ Al (OH)3↓

Precipitate zinc. It is recommended to oxygenate the water in an artesian way so that it reacts with O2 precipitates in the form of zinc hydroxide (Zn (OH)2↓)

Zn2 + O−2 ⟶ Zn O + H2O ⟶ Zn (OH)2↓

Constant cleaning of water storage tanks is also recommended, with at least maintenance every two months. It is an easy method of operation for the users and will bring benefits such as the removal of inorganic (including aluminium that could be present as a precipitate) and organic particles and reduction of turbidity [58].

Table 5.

Water quality (mean ± standard deviation) based on monthly evaluation during two months of the low water season (September and October 2020).

| Systems samples (inlet/outlet) | pH (units) | Turbidity (NTU) | Aluminium (mg/L) | Zinc (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPK-S2 (inlet) | 6.95 ± 0.12 | 1.75 ± 0.21 | 0.67∗ ± 0.69 | 2.51 ± 0.84 |

| FPK-S2 (outlet) | 6.99 ± 0.05 | 1.10 ± 0.42 | 1.26∗ ± 1.44 | 1.82 ± 0.24 |

| FJT-S1 (inlet) | 6.80 ± 0.27 | 1.20 ± 0.28 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 2.06 ± 0.44 |

| FJT-S1 (outlet) | 6.81 ± 0.18 | 1.55 ± 0.21 | 0.29∗ ± 0.20 | 2.59 ± 0.86 |

| FT-S4 (inlet) | 7.07 ± 0.13 | 1.35 ± 0.21 | 0.21∗ ± 09 | 3.12∗ ± 2.12 |

| FT-S4 (outlet) | 7.03 ± 0.12 | 1.85 ± 0.07 | 0.24∗ ± 0.13 | 3.30∗ ± 2.31 |

| FI-S3 (inlet) | 7.30 ± 0.08 | 1.90 ± 0.14 | 0.46∗ ± 0.28 | 4.93∗ ± 3.89 |

| FI-S3 (outlet) | 7.29 ± 0.08 | 2.20 ± 0.28 | 0.22∗ ± 0.01 | 4.92∗ ± 3.90 |

| D.S. N° 031-2010-SA | 6.5–8.5 | 5 UNT | 0.2 mg Al/L | 3.0 mg Zn/L |

∗ Noncompliant; nc = not contemplated in the standard.

Table 6 shows the results for microbiological parameters in the rainy season, which were above the water quality regulation (>1,600 NMP/100 mL). In many parts of the world, rainwater does not meet quality standards, and this is attributed to the frequent presence of faecal contamination, mainly from animal origin [59, 60]. High contamination densities are likely to have been caused by the abrupt temperature change during rainfall [61]. Particulates and total coliforms are likely to affect the functioning of the rainwater utilisation system, making ongoing studies a necessity [62].

Table 6.

Microbiological parameter results.

| Systems samples (inlet/outlet) | Total coliforms (NMP/100 mL) | Faecal coliforms (NMP/100 mL) | E. coli (NMP/100 mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological parameter (rainy season) | |||

| FPK-S2 (inlet) | 1,600∗ | 180∗ | 2∗ |

| FPK-S2 (outlet) | 350∗ | 130∗ | 0 |

| FJT-S1 (inlet) | >1,600∗ | >1,600∗ | 17∗ |

| FJT-S1 (outlet) | 13∗ | 13∗ | 5∗ |

| FT-S4 (inlet) | 920∗ | 1,600∗ | 4∗ |

| FT-S4 (outlet) | 1,600∗ | <1.8 | 1,600∗ |

| FI-S3 (inlet) | 1.568∗ | 81∗ | >1,600∗ |

| FI-S3 (outlet) | 1.524∗ | 23∗ | 13∗ |

|

| |||

| Microbiological parameter (low water season) | |||

| FPK-S2 (inlet) | 234∗ | 99∗ | SN |

| FPK-S2 (outlet) | <1.8 | <1.8 | SN |

| FJT-S1 (inlet) | 8.5∗ | 7 | SN |

| FJT-S1 (outlet) | <1.8 | <1.8 | SN |

| FT-S4 (inlet) | 239.5∗ | 20.5∗ | SN |

| FT-S4 (outlet) | <1.8 | <1.8 | SN |

| FI-S3 (inlet) | 280∗ | 84∗ | SN |

| FI-S3 (outlet) | <1.8 | <1.8 | SN |

| D.S. N° 031-2010-SA | <1.8 | <1.8 | <1.8 |

∗ Does not comply with the standard (D.S. N° 031-2010-SA); SN = samples not taken.

In low water season, all the results met the standard at the outlet of the system, given that the water samples were taken after treatment (chlorination). The importance of chlorinating the water lies in eliminating microorganisms [63, 64], so disinfection was carried out with commercial bleach at a rate of 5 drops per gallon (of 5 L) and left to stand for 30 minutes before use. When water is not chlorinated, microorganisms may be present in the water [65], as evidenced during the rainy season. With the operation and maintenance of rainwater harvesting systems, the quality of water for human consumption is guaranteed [66]. However, it is recommended that rainwater be chlorinated [67]. Chlorination of stored water reduces the risk of diarrhoea [68]. Therefore, rainwater harvesting systems can improve the quality of life of the inhabitants. In Australia, samples collected from 10 tanks contained E. coli in concentrations that exceeded the limit of 150 MPN/100 mL for recreational water quality [69]. Bacteria may be associated with rainfall events and be in connecting pipes, and they can survive and even grow in an open environment, subject to the environmental level of nutrients and conditions such as temperature and pH [70].

pH showed no significant difference (Table 7) and falls within the water quality standards. pH value allows the determination of the degree of contamination caused by sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides [71]. The pH values obtained are related to the type of storage tank [72], for example, asbestos sheet roofs have pH values of 6.75 [73]. Rainwater pH can vary from weakly acidic (pH 3.1) to weakly alkaline (pH 11.4). In previous studies, the pH of rainwater ranged from 6.6 to 8.26 [74]. In this study, the pH ranged between 6.82 and 7.02.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis between study periods.

| Study periods | pHns (units) | Turbidityns (mg/L) | Aluminium∗ (mg/L) | Znns (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainy season | 6.82 + 0.35 | 1.24 + 0.70 | 0.13 + 0.10 | 2.55 + 1.58 |

| Low water season | 7.02 + 0.22 | 1.58 + 0.41 | 0.37 + 0.34 | 3.15 + 1.94 |

ns = no significant difference; ∗significant difference.

Rainwater turbidity was below the standard (5 NTU), with average values of 1.24 for the rainy season and 1.58 NTU for the dry season. There were no significant differences between seasons. Turbidity is important to analyse because it influences water clarity, and its presence may be associated with extreme rainfall allowing the presence of suspended solids [16].

Aluminium in rainwater, 0.16 and 0.67 mg/L, exceeded the Peruvian water quality standard for human consumption (0.2 mg Al/L). The statistical analysis shows significant differences between seasons, with higher amounts of aluminium and zinc found during the dry season. The presence of aluminium in water is detrimental to life [16]. The presence of zinc ranged between 2.55 and 3.15, zinc is associated with the type of shed. Acuña [75] found that rainwater collected on galvanised steel roofs is distinguished by higher zinc content (69 to 102 mg/L).

3.7. Economic Feasibility

The initial investment of the systems installed is S/2,600 at full cost, and their maintenance is S/70 per year, built of concrete. An alternative rainwater harvesting system is also proposed at a lower cost (S/2,000), with a base constructed of wood, which is abundant in the area, known as Huacapu (Minquartia guianensis Aubl). Huacapu is a suitable wood, as it is strong and durable, widely used in construction [76]. The details of the costs in each case (reinforced concrete support and local alternative) are described in Table 8.

Table 8.

Installation costs of concrete-based rainwater harvesting systems versus a cheaper wood-based alternative in native areas.

| Aspects | Quantity | Unit | Unitary price | Tank support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforced concrete support (S/) estimated in total prices | Local alternative (wooden board) estimated in total prices | ||||

| Cost of land | 1 | Global | 84.00 | 84.00 | |

| Cost of transport | 1 | Global | 1,200.00 | 600.00 | |

|

| |||||

| Cost of installation local labour | |||||

| 1 operator from outside the locality∗ | 10 | day | 110 | 1,100.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 officer from outside the locality∗ | 10 | day | 80 | 800.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 community labourer∗ | 10 | day | 40 | 400.00 | 0.00 |

| 1 carpenter from outside the community | 13 | day | 110 | 0.00 | 1,430.00 |

| 2 community labourers | 13 | day | 80 | 0.00 | 1,040.00 |

|

| |||||

| Cost of hardware materials (for concrete base vs. common wood alternative in native areas) | |||||

| 1/8-inch thick galvanised metal platen supports | 38 | Unit | 6.8 | 258.40 | 258.40 |

| Self-drilling fastening bolts for gutters, hexagonal head | 76 | Unit | 0.6 | 45.60 | 45.60 |

| PVC catchment funnel | 4 | Unit | 25 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| PVC pipe, 4 inches | 4 | Unit | 20 | 80.00 | 80.00 |

| 4 inch × 90 degree PVC elbows | 16 | Unit | 6 | 96.00 | 96.00 |

| Codos de PVC 4 × 2 pulgadas, con ventilación | 4 | Unit | 6 | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| 2-inch PVC plug | 4 | Unit | 2 | 8.00 | 8.00 |

| Reduction from 4- to 3-inch PVC | 4 | Unit | 6 | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| 2 inch × 90 degree PVC elbows | 8 | Unit | 4 | 32.00 | 32.00 |

| PVC pipe, 2 inches | 8 | Unit | 13 | 104.00 | 104.00 |

| PVC tee, 2 inches | 4 | Unit | 5 | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| PVC ventilation cap, 2 inches | 4 | Unit | 5 | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| 3/4-inch PVC ball valve | 4 | Unit | 15 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| PVC union with 3/4 inch thread | 4 | Unit | 3 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| PVC reduction, 3/4 to 1/2 inch | 4 | Unit | 1.5 | 6.00 | 6.00 |

| PVC adapters, 3/4 inch | 16 | Unit | 1.5 | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| PVC pipe, 1/2 inch | 4 | Unit | 10 | 40.00 | 40.00 |

| 3/4-inch PVC pipe | 2 | Unit | 12 | 24.00 | 24.00 |

| Mixed PVC joint (thread and spigot), 1/2 inch | 4 | Unit | 2.5 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| 1/2-inch PVC spigot union | 8 | Unit | 1.5 | 12.00 | 12.00 |

| 1/2 inch × 90 degree PVC elbows | 10 | Unit | 2 | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| 1/2-inch PVC tap | 4 | Unit | 15 | 60.00 | 60.00 |

| PVC glue × 1/8 gallon | 1 | Unit | 20 | 20.00 | 20.00 |

| Polyethylene tanks with ultraviolet protection, 1,100 L capacity | 4 | Unit | 475 | 1,900.00 | 1,900.00 |

| Black annealed wire, 16 gauge | 20 | kg | 5 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Black annealed wire, 8 gauge | 20 | kg | 5 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Portland cement type I | 32 | Bags | 26 | 832.00 | 0.00 |

| 3-inch wood nails | 15 | kg | 8 | 120.00 | 0.00 |

| 3/8-inch corrugated steel | 10 | Rod | 16 | 160.00 | 0.00 |

| 1/2-inch corrugated steel | 42 | Rod | 27.5 | 1,155.00 | 0.00 |

| 1/4-inch corrugated steel | 11 | Rod | 7 | 77.00 | 0.00 |

|

| |||||

| Cost of materials in the area | |||||

| River concrete | 4.5 | m3 | 120 | 540.00 | 0.00 |

| Ordinary timber for shuttering | 183 | p2 | 4 | 732.00 | 0.00 |

| Wood for tank supports | 461.5 | p2 | 4 | 0.00 | 1,846.00 |

| Total cost (4 systems) | 10,400.00 | 8,000.00 | |||

| Total cost (1 system) | 2,600.00 | 2,000.00 | |||

∗ Category of labour force, existing in civil construction (worker, journeyman, and labourer); p2 = square feet; and Bl = bag of cement weighs 42.5 kilograms.

The economic evaluation, at a discount rate of 10%, shows an NPSV of S/1,911. The SIRR was above the discount rate, which indicates that future investment in the systems is profitable. The annual benefits to the families are S/1,260, valued at the time spent bringing water to their homes and the cost of consuming clean water (Table 9). In the native community, Juum in the Amazon region, Jiménez [77] evaluated technically and economically a rainwater harvesting system for domestic use and determined that the design of the system is viable and sustainable. The cost of harvested rainwater can be up to nine times lower than desalinated or treated water, and policies are needed to promote the construction and installation of rainwater harvesting systems [78]. Rainwater harvesting is a viable alternative for domestic use and even for irrigation [79]. To reduce costs in treatment systems, it is advisable to place co-layers (grids) that serve as a trap for large particles and leaves from trees that fall on the roof and clog the system [80]. Thus, treated rainwater costs 60% less than drinking water provided by the supplier [79]. The B/C is 1.73 soles, which is cost-effective, but this depends on the project area as it does not agree with the study by Domínguez et al. [79], who found that the cost benefit was $1.34.

Table 9.

Economic analysis of catchment systems.

| Benefits and costs | |

|---|---|

| Initial investment | S/2,600 |

| Systems maintenance (year) | S/70 |

| Benefits (annual) | S/1,260 |

| NPSV | S/1,911 |

| SIRR | 36% |

| B/C | S/1.73 |

NPSV = net present social value, SIRR = social internal rate of return, and B/C = benefit cost.

3.8. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

The valuation of the cost of water was based on the assumption that how much would the family save to stop carrying water. In this sense, we took into account that the average time spent carrying water is 30 minutes one way and 40 minutes return; the difference is due to the weight of water carried. The average time per family is 2.34 hours/day to carry water just for food preparation and washing dishes (Table 10).

Table 10.

Costs from the social assessment.

| Description | Units | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Water carrying time | Hours/day | 2.34 |

| Daily working day | Hours/day | 8 |

| Labour cost | Soles/day | 40 |

| Cost per 10 L bucket haulage | Soles/day | 11.68 |

| Total haulage cost | Soles/month | 350.25 |

| Total haulage cost | Soles/year | 4,203.00 |

The annual cost of the water supply for food preparation was 4,203 soles, without taking into account the time it takes them in the evenings to go to the streams to have their personal hygiene. Compared to the cost of carrying water in a year, with less than half, they can install a proposed water harvesting and reuse system (S/2,600). As such, access to water has become a management problem to improve the quality of life in rural areas, due to high costs [19]. The lack of water has caused great famines and has led to the mobilisation of entire villages in search of solutions [81]. Native communities are no exception to these social conflicts (access to basic services such as water) [5].

3.9. Horizon Assessment for Both without Project and with Project

The 5-year evaluation was carried out on the basis of the total haulage cost per family year (Table 11). The cost of hauling during the evaluation horizon (2021–2026) is shown to be S/2,181.35, which corresponds to the sum of the annual hauling costs in years 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 (estimated situation without project). It is important to mention that, currently, these costs are covered by the population in the time spent carrying the water. Consequently, they are unable to perform their normal activities (social, family, economic, educational, etc.). Water access, like money, is a fundamental need of any population and is an essential condition for many people to have a better life [82].

Table 11.

Carrying costs that the locality incurs during the assessment horizon (situation without project).

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2021–2026 | |

| Number of families | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 89 |

| Annual cost (S/)∗ | 35,305 | 35,725 | 36,145 | 36,566 | 36,986 | 37,406 | 218,135 |

∗ Carrying cost without project (S/4,203.00 per family).

Table 12 shows the investment costs over the 5-year evaluation horizon. For the implementation of the rainwater harvesting and treatment system, 89 families were estimated with an annual investment cost of S/2,600.00 per family. The investment in the fifth year would be S/231,400. This evaluation horizon will allow competent bodies to determine the amount of investment in rainwater in order to satisfy the human right to water, without necessarily achieving an economic benefit [82]. In this sense, a cost-effectiveness analysis was useful to value costs that could not be presented in terms of monetary values [83].

Table 12.

Investment costs over the evaluation horizon (situation with project).

| Year | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2021–2026 | |

| Number of families | 84 | 85 | 86 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 89 |

| Investment cost (S/)∗ | 218,400 | 221,000 | 223,600 | 226,200 | 228,800 | 231,400 | 231,400 |

∗ The investment cost of the systems is S/2,600.00 per family.

Table 13 shows the cost flow over the evaluation horizon, both with and without project. With 10% of the total haulage costs incurred by the inhabitants of the locality (Tunants and Yahuhua), the water supply problem could be solved. This would allow them to cover their needs for human consumption and domestic use water. Socio-economic factors of the population would have positive readjustments, such as human health improvements [83]. Another benefit of rainwater harvesting systems is the reduction of vulnerability to floods and river overflows, which are strategies for the implementation of disaster risk management [39]. Therefore, it is shown that the implementation of rainwater treatment systems projected over 5 years is 262,550 soles. The costs are less than the costs of carrying water from the stream (2,181,357). Future research in the native communities of the Amazon region related to the use of well water is important, as it has shown high potential in other places since it is cheap and quickly accessible in times of drought [84]. Taking into consideration that a limiting factor is microbial contamination of groundwater, which has become a global problem and remains a management challenge as an integrated groundwater model [85, 86].

Table 13.

Comparison of costs without project and with project.

| Description | Situation without project | Situation with project |

|---|---|---|

| Water haulage | 2,181,357 | 0 |

| Investment | 0 | 231,400 |

| OM | 0 | 31,150 |

| Total | 2,181,357 | 262,550 |

OM: operational and maintenance.

4. Conclusions

Rainwater harvesting for domestic use and human consumption in native communities in Amazonas (NW Peru) is feasible according to technical and economical validation. Rainwater harvesting can supply six family members with daily consumption of 32.5 L per person. Regarding water quality, no significant differences in physicochemical parameters are shown. However, for heavy metals, aluminium showed the most significant difference. A mechanical oxygenation system should be implemented to sediment heavy metals, as it is economical and easy to use. The implementation of rainwater harvesting systems can be an alternative water supply in native communities as it is cheap and accessible. However, water management systems must be implemented for its use, after treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the support of the Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo Sustentable de Ceja de Selva (INDES-CES) of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas (UNTRM). This research was funded by Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico, Tecnológico y de Innova-ción Tecnológica—FONDECYT, contract no. 185-2018-FONDECYT-MB-IADT-SE (PROLLUVIA project).

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ruiz-cuello T., Pescador-piedra J. C., Raymundo-Núñez L. M., Pineda-Camacho G. Dimensionamiento de un sistema hidráulico en casa-habitación para el uso de agua residual. Revista Cubana de Química . 2015;27:315–324. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ISBN WHO/SDE/WSH/03.02. WHO Domestic Water Quantity, Service Level and Health . 2nd. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Agua y Saneamiento: Evidencias para Políticas Públicas con Enfoque en Derechos Humanos y Resultados En Salud Pública . Washington, DC, USA: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carmona Clavijo G., Daza Arevalo J., Osorio Pretel V. L. Percepciones sobre la vacunación de la rabia silvestre en población Awajún de la provincia. Saúde Coletiva . 2015;1:p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina-Ibañez A., Mayca Pérez J., Velásquez-Hurtado J. E., Llanos-Zavalaga L. F. Conocimientos, percepciones y prácticas sobre el consumo de micronutrientes en niños Awajún y Wampis (Condorcanqui, Amazonas-Perú) Acta Médica Peruana . 2019;36(3):185–194. doi: 10.35663/amp.2019.363.829. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortiz-Guzmán M., Morales-Domínguez V., Aragón-Sulik M. Cosecha de agua de lluvia con tanques de mampostería. Caso: san Miguel Piedras, Nochixtlán, Oaxaca. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing . 2009;30:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durán Juárez J., Torres A. Los problemas del abastecimiento de agua potable en una ciudad media. Espiral . 2006;17:129–162. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hugues R. T. La captación del agua de lluvia como solución en el pasado y el presente. Ingenieria Hidraulica y Ambiental . 2019;40:125–139. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De La Cruz U., Gleason J., Gleason J. Beneficios económicos de implementar un sistema de captación de agua de lluvia en La Universidad de guadalajara. Vivienda y Comunidades Sustentables . 2018;4:11–20. doi: 10.32870/rvcs.v0i4.63. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva C. M., Sousa V., Carvalho N. V. Evaluation of rainwater harvesting in Portugal: application to single-family residences. Resources, Conservation and Recycling . 2015;94:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez Hernández A., Palacios Vélez O. L., Anaya Garduño M., Tovar Salinas J. L. Agua de lluvia para consumo humano y uso doméstico en san miguel tulancingo, oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas . 2017;8(6):1427–1432. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v8i6.313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agatón, León A., Juan Carlos Córdoba RuizUriel F. C. S. Revisión del estado de arte en captación y aprovechamientode aguas lluvias en zonas urbanas y aeropuertos. Tecnura . 2016;20:141–153. doi: 10.14483/udistrital.jour.tecnura.2016.4.a10. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ornetti P., Fortunet C., Morisset C., et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of a distraction-rotation knee brace for medial knee osteoarthritis. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine . 2015;58(3):126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman A., Keane J., Imteaz M. A. Rainwater harvesting in greater Sydney: water savings, reliability and economic benefits. Resources, Conservation and Recycling . 2012;61:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2011.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chino-Calli M., Velarde-Coaquira E., Espinoza Calsín J. J. Captación de agua de lluvia en cobertura de viviendas rurales para consumo humano en la Comunidad de Vilca Maquera, Puno-Perú. Revista de Investigaciones Altoandinas - Journal of High Andean Research . 2016;18(3):365–373. doi: 10.18271/ria.2016.226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ospina Zuñiga O., García Cobas G., Gordillo Rivera J., Tovar Hernández K. Evaluación de la turbiedad y la conductividad ocurrida en temporada seca y de lluvia en el río Combeima (Ibagué, Colombia) Ingeniería Solidaria . 2016;12(19):19–36. doi: 10.16925/in.v12i19.1191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romero Orué M., Gaiero D., Paris M., et al. Wet precipitation in northern Argentina: chemical characterization of soluble components in the Lerma valley, Salta. Andean Geology . 2017;44(1):59–78. doi: 10.5027/andgeoV44n1-a04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas P. R., Greene G. R. Rainwater quality from different roof catchments. Water Science and Technology . 1993;28(3–5):291–299. doi: 10.2166/wst.1993.0430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domínguez Serrano J. El acceso al agua y saneamiento: un problema de capacidad institucional local. Análisis en el estado de Veracruz, Gestión y política pública . 2010;19(2):311–350. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rojas E. M., Díaz Ortiz E. A., García L., Veneros Guevara J., Segundo Chavez Quintana C. A. M. T. Calidad físicoquímica y microbiológica del agua en los lagos de tunants y yahuahua, en la región Amazonas, Perú. Revista Latinoamericana de Difusión Científica . 2021;3:89–92. doi: 10.38186/difcie.34.07. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marín L. Desinfección del agua: sistemas utilizados en aya. Hidrogénesis . 2007;5:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stec A., Zeleňáková M. An analysis of the effectiveness of two rainwater harvesting systems located in central eastern Europe. Water . 2019;11(3):p. 458. doi: 10.3390/w11030458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofman-Caris R., Bertelkamp C., de Waal L., et al. Rainwater harvesting for drinking water production: a sustainable and cost-effective solution in the Netherlands? Water . 2019;11(3):p. 511. doi: 10.3390/w11030511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster. Bibliography and Index of Paleozoic Crinoids and Coronate Echinoderms 1981—1985 . Boulder, CO, USA: Geological Society of America; [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Publicc M. Bibliography and Index of Paleozoic Crinoids and Coronate EchinodenTIS 1981-1985 . Pullman, WA, USA: Washington State University; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabezas C. Enfermedades infecciosas relacionadas con el agua en el Perú. Rev Peru. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública . 2002;35:309–316. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2018.352.3761.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hidalgo C. H., Reßtegui M. G., Rada L. A. Prevalencia de hepatitis viral A y B y factores de riesgo asociados a su infección en la población escolar de un distrito de Huánuco-Perú. Revista Peruana de Medicina Experimental y Salud Pública . 2002;19:5–9. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2002.191.777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.García J. M. Hidrografía - zonificación Ecológica Económica del departamento de Amazonas. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling . 2010;53:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 29.INEI. III Censo de Comunidades Nativas 2017: Resultados Definitivos . Sydney, Australia: INEI; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hocquenghem A. M., Durt É. Integración y desarrollo de la región fronteriza peruano ecuatoriana: entre el discurso y la realidad, una visión local. Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines . 2002;31(1):39–99. doi: 10.4000/bifea.6926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burneo Mendoza R. Territorio integral indígena, una propuesta awajún. Iztapalapa. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades . 2018;85:33–57. doi: 10.28928/revistaiztapalapa/852018/atc2/burneomendozar. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilcreas F. W. Future of standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Health Laboratory Science . 1967;4(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarmiento A., Rojas M., Medina E., Olivet C., Casanova J. Investigación de trihalometanos en agua potable del estado carabobo, venezuela. Gaceta Sanitaria . 2003;17(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0213-9111(03)71711-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ministerio de Educación Normas Legales Normas Legales. D. Of. 2019, 10–15.

- 35.Pique del pozo J. Resolucion Ministerial N°-192-2018-Vivienda 2018 . San Isidro, Peru: Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento; [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alfonso R. Procedimiento Para El Diagnóstico Del Sistema De Gestión Tecnológica E Innovación En Entidades De Transporte Turístico . Santa Clara, Cuba: Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.UNESCO. Informe Mundial de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Desarrollo de los Recursos Hídricos 2019. No dejar a nadie atrás . Paris, France: UNESCO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suárez J. A. B., García M. Á. G., Mosquera R. O. O. Sistemas de aprovechamiento de Agua Lluvia para Vivienda Urbana. Proceedings of the 22th Latin American Congress on Hydraulics and International Symposium on Hydraulic Structures; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arroyave Rojas J., Díaz Vélez J., Vergara D., Macías N. Evaluación económica de la captación de agua lluvia como fuente alternativa de recurso hídrico en la Institución Universitaria Colegio Mayor de Antioquia. Produccion y Limpia . 2011;6:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jianbing Z., Changming L., Hongxing Z. Cost-benefit analysis for urban rainwater harvesting in Beijing. Water International . 2010;35(2):195–209. doi: 10.1080/02508061003667271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mariño R. Evaluación económica del programa de fluoración del agua de beber en Chile. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública . 2013;17(2):p. 124. doi: 10.5354/0719-5281.2013.27092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biswas B. K., Mandal B. H. Construction and evaluation of rainwater harvesting system for domestic use in a remote and rural area of Khulna, Bangladesh. International Scholarly Research Notices . 2014;2014:6. doi: 10.1155/2014/751952.751952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.UNHCR, “EC/54/SC/C/CRP.14. Protracted refugee situations. Proceedings of the 30th meeting of Executive Committee of the High Commissioner’s Programme; June 2004; Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palacio N. Rainwater system proposal as an alternative to save drinking water in the educational institution María Auxiliadora from Caldas, Antioquia. Gestión y Ambient . 2010;13(2):25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aguiar Ribeiro Do Nascimiento, El Derecho al G. Agua y su Protección en el Contexto de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. Estudios Constitucionales . 2018;16(1):245–280. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eruola A. O., Ufoegbune G. C., Awomeso J. A., Adeofun C. O., Idowu O. A. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of rainwater harvesting from rooftop catchments: case study of Oke-Lantoro community in Abeokuta, Southwest Nigeria. European Water . 2010;32:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doria Argumedo C. J. Metales pesados (Cd, Cu, V, Pb) en agua lluvia de la zona de mayor influencia de la mina de carbón en La Guajira, Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Química . 2017;46(2):37–44. doi: 10.15446/rev.colomb.quim.v46n2.60533. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zafra Mejía C. A., Rodríguez Chitiva L. G., Torres Cabrera Y. A. Metales pesados asociados con las partículas atmosféricas y sedimentadas de superficies viales: soacha (Colombia) Revista Científica . 2013;1(17):p. 113. doi: 10.14483/23448350.4571. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Momani I. Trace elements in atmospheric precipitation at Northern Jordan measured by ICP-MS: acidity and possible sources. Atmospheric Environment . 2003;37(32):4507–4515. doi: 10.1016/S1352-2310(03)00562-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gould J. Rainwater safe to drink? A review of recent findings. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling . 1999;53:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chubaka C., Whiley H., Edwards J., Ross K. Lead, zinc, copper, and cadmium content of water from South Australian rainwater tanks. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2018;15(7):1551–1612. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bolaños-Alfaro J. D., Cordero-Castro G., Segura-Araya G. Determinación de nitritos, nitratos, sulfatos y fosfatos en agua potable como indicadores de contaminación ocasionada por el hombre, en dos cantones de Alajuela (Costa Rica) Revista Tecnología en Marcha . 2017;30(4):15–27. doi: 10.18845/tm.v30i4.3408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maroneze M. M., Zepka L. Q., Vieira J. G., Queiroz M. I., Jacob-Lopes E. A tecnologia de remoção de fósforo: gerenciamento do elemento em resíduos industriais. Revista Ambiente e Agua . 2014;9:445–458. doi: 10.4136/1980-993X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.González M. Madrid, Spain: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid; 2014. Estudio de la calidad del agua en cisternas de captación de agua de lluvia en escuelas rurales de Alagoas (Brasil) Master thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pérez-López E. Control de calidad en aguas para consumo humano en la región Occidental de Costa Rica. Revista Tecnología en Marcha . 2016;29(3):p. 3. doi: 10.18845/tm.v29i3.2884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Al-Khatib I., Arafeh G., Al-Qutob M., et al. Health risk associated with some trace and some heavy metals content of harvested rainwater in yatta area, Palestine. Water . 2019;11(2):p. 238. doi: 10.3390/w11020238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Municipalidad provincial de Condorcanqui, CEPLAN y Fundación Ayuda en Acción. Plan Binacional de Desarrollo de la Región Fronteriza Perú - Ecuador: Diagnóstico de las brechas sociales y de infraestructura de la provincia de Condorcanqui, departamento de Amazonas, CEPLAN, 2006.

- 58.Nzewi E. U., Sarikonda S., Lee E. J. Analysis and treatment of harvested rainwater. Proceedings of the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2010; May 2010; Providence, RI, USA. pp. 495–503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yaziz M. I., Gunting H., Sapari N., Ghazali A. W. Variations in rainwater quality from roof catchments. Water Research . 1989;23(6):761–765. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(89)90211-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinfold J. V., Horan N. J., Wirojanagud W., Mara D. The bacteriological quality of rainjar water in rural northeast Thailand. Water Research . 1993;27(2):297–302. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(93)90089-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xavier R. P., Siqueira L. P., Vital F. A. C., Rocha F. J. S., Irmão J. I., Calazans G. M. T. Microbiological quality of drinking rainwater in the inland region of Pajeú, Pernambuco, Northeast Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo . 2011;53(3):121–124. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652011000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim D. Physico-chemical conversion of lignocellulose: inhibitor effects and detoxification strategies: a mini review. Molecules . 2018;23(2):p. 309. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Licea-Jimenez I., González-Marañón A., Sam-Pérez R., Gómez-Luna L., Ortega-Díaz Y. Reformulación de la solución de hipoclorito de sodio al 1 % para su producción en tiempos de contingencia. Revista Cubana de Química . 2018;30:379–399. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zúñiga Carrasco I. R., Samperio Morales H. Importance of water chlorination: pathogenic bacteria in supply sites. Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología . 2019;39:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodriguez-Alvarez M. S., Moraña L. B., Salusso M. M., Seghezzo L. Caracterización espacial y estacional del agua de consumo proveniente de diversas fuentes en una localidad periurbana de Salta. Revista Argentina de Microbiología . 2017;49(4):366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ram.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nickisch B., MarioSánchez L. T., Díaz R. T., FabiánJordan P. Sistemas de captación de agua de lluvia para consumo humano, sinónimo de agua segura. Journal of Materials Processing Technology . 2018;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karpenko N. A., Merkurjev A. S. Conceptos básicos de control de infecciones . International Federation of Infection Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garrett V., Ogutu P., Mabonga P., et al. Diarrhoea prevention in a high-risk rural Kenyan population through point-of-use chlorination, safe water storage, sanitation, and rainwater harvesting. Epidemiology and Infection . 2008;136(11):1463–1471. doi: 10.1017/S095026880700026X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chubaka C., Whiley H., Edwards J., Ross K. Microbiological values of rainwater harvested in adelaide. Pathogens . 2018;7(1):p. 21. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Van Elsas J. D., Semenov A. V., Costa R., Trevors J. T. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. The ISME Journal . 2011;5(2):173–183. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bluhm-Gutiérrez J. Aspectos de la medición del pH del agua de lluvia. Proceedings of the Coloquio de Investigación de la UAZ 2009; October 2009; Zacatecas, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Simmons G., Hope V., Lewis G., Whitmore J., Gao W. Contamination of potable roof-collected rainwater in Auckland, New Zealand. Water Research . 2001;35(6):1518–1524. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Olaoye R., Olaniyan O. Quality of rainwater from different roof material. International Journal of Engineering & Technology . 2012;2:1413–1421. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Struk-Sokołowska J., Gwoździej-Mazur J., Jadwiszczak P., et al. The quality of stored rainwater for washing purposes. Water . 2020;12(1):252–317. doi: 10.3390/w12010252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Universidad Nacional de Trujillo (UNT) Leocadio Malca Acuña Niveles de Absorción del Zinc Proveniente de Calaminas de Viviendas por Medicago sativa y su Metabolismo en Cavia porcellus . Trujillo, Peru: Universidad Nacional de Trujillo (UNT); 2009. pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nebel G. Minquartia guianensis Aubl.: use, ecology and management in forestry and agroforestry. Forest Ecology and Management . 2001;150(1-2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00685-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geidy Yecenia J. Y. Diseño De Sistema De Aprovechamiento De Lluvia Para Uso Doméstico En La Comunidad Awajun De Juum Del Distrito De Imaza, Provincia De Bagua . Leticia, CO, USA: Departamento De Amazonas; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peters E. J. Rainwater potential for domestic water supply in Grenada. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Water Management . 2006;159(3):147–153. doi: 10.1680/wama.2006.159.3.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Domínguez I., Ward S., Mendoza J., Rincón C., Oviedo-Ocaña E. End-user cost-benefit prioritization for selecting rainwater harvesting and greywater reuse in social housing. Water . 2017;9(7):p. 516. doi: 10.3390/w9070516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abdulla F. A., Al-Shareef A. W. Roof rainwater harvesting systems for household water supply in Jordan. Desalination . 2009;243(1-3):195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.desal.2008.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gutiérrez C., Ochoa L., Velasco I. Sequía, un problema de perspectiva y gestión. Región y Sociedad . 2005;17:35–71. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Goff M., Crow B. What is water equity? The unfortunate consequences of a global focus on ’drinking water’. Water International . 2014;39(2):159–171. doi: 10.1080/02508060.2014.886355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Delpla I., Jung A.-V., Baures E., Clement M., Thomas O. Impacts of climate change on surface water quality in relation to drinking water production. Environment International . 2009;35(8):1225–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Llamas M. R., Martínez-Santos P. Intensive groundwater use: silent revolution and potential source of social conflicts. Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management . 2005;131(5):337–341. doi: 10.1061/(asce)0733-9496(2005)131:5(337). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chique C., Hynds P. D., Andrade L., et al. Cryptosporidium spp. in groundwater supplies intended for human consumption - a descriptive review of global prevalence, risk factors and knowledge gaps. Water Research . 2020;176 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115726.115726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Okotto L., Okotto-Okotto J., Price H., Pedley S., Wright J. Socio-economic aspects of domestic groundwater consumption, vending and use in Kisumu, Kenya. Applied Geography . 2015;58:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2015.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.