Abstract

Background

Vaccines are critical cost-effective tools to control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. However, the emergence of variants of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) may threaten the global impact of mass vaccination campaigns.

Aims

The objective of this study was to provide an up-to-date comparative analysis of the characteristics, adverse events, efficacy, effectiveness and impact of the variants of concern for 19 COVID-19 vaccines.

Sources

References for this review were identified through searches of PubMed, Google Scholar, BioRxiv, MedRxiv, regulatory drug agencies and pharmaceutical companies' websites up to 22nd September 2021.

Content

Overall, all COVID-19 vaccines had a high efficacy against the original strain and the variants of concern, and were well tolerated. BNT162b2, mRNA-1273 and Sputnik V after two doses had the highest efficacy (>90%) in preventing symptomatic cases in phase III trials. mRNA vaccines, AZD1222, and CoronaVac were effective in preventing symptomatic COVID-19 and severe infections against Alpha, Beta, Gamma or Delta variants. Regarding observational real-life data, full immunization with mRNA vaccines and AZD1222 seems to effectively prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection against the original strain and Alpha and Beta variants but with reduced effectiveness against the Delta strain. A decline in infection protection was observed at 6 months for BNT162b2 and AZD1222. Serious adverse event rates were rare for mRNA vaccines—anaphylaxis 2.5–4.7 cases per million doses, myocarditis 3.5 cases per million doses—and were similarly rare for all other vaccines. Prices for the different vaccines varied from $2.15 to $29.75 per dose.

Implications

All vaccines appear to be safe and effective tools to prevent severe COVID-19, hospitalization, and death against all variants of concern, but the quality of evidence greatly varies depending on the vaccines considered. Questions remain regarding a booster dose and waning immunity, the duration of immunity, and heterologous vaccination. The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination outweigh the risks, despite rare serious adverse effects.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Delta, Efficacy, Review, SARS-CoV-2, Seroneutralization, Vaccines, Variants

Background

The implementation of vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a major asset in slowing down the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. At the time of writing, more than 100 vaccines have been developed, and 26 vaccines have been evaluated in phase III clinical trials, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1].

Recently, several variants of concern (VOCs) have emerged, including Alpha (known as 501Y.V1 with GISAID nomenclature or B.1.1.7 variant with PANGO nomenclature), Beta (501Y.V2 or B.1.351), Gamma (501Y.V3 or P1) and Delta (G/478K.V1 or B.1.617.2). These variants have been associated with an increase in the transmission or mortality of COVID-19 [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]] or may escape immunity when compared to the original strain or D614G variant [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]].

While phase III trials assess the efficacy under controlled conditions, phase IV studies evaluate the real-world effectiveness of the vaccines in an observational design among a larger general population. These studies bring crucial information about rare or long-term effects, the prevention of asymptomatic infection, and the severity of COVID-19.

The administration of COVID-19 vaccines is a major priority for many countries around the world. Due to the speed of production of scientific data in the context of this pandemic, it can be difficult for healthcare professionals to update themselves on the latest data concerning COVID-19 vaccines.

The objective of this review is to provide an up-to-date comparative analysis of the characteristics, adverse events, efficacy, effectiveness, and impact of the variants of concern on the following 19 COVID-19 vaccines: mRNA vaccines (BNT16b2, mRNA-1273, CVnCoV), viral vector vaccines (AZD1222, Sputnik V, Sputnik V Light, Ad5-nCoV (Convidecia), Ad26.COV2.S), inactivated vaccines (NVX-COV2373, CoronaVac, BBIBP-CorV, Wuhan Sinopharm inactivated vaccine, Covaxin, QazVac, KoviVac, COVIran Barekat), and protein-based vaccines (EpiVacCorona, ZF2001, Abdala).

Methods

Electronic searches for studies were conducted using Pubmed and Google scholar until 22nd September 2021 using the search terms “SARS-CoV-2”, “COVID-19”, “efficacy”, “effectiveness”, “neutralization assays”, and “neutralization antibodies” in addition to the scientific or commercial names of the vaccines reported by WHO in phase III/IV. The ClinicalTrials.gov database was consulted using the terms “COVID-19” and “vaccine”. BioRxiv and MedRxiv, regulatory drug agencies and pharmaceutical companies' websites were also consulted for unpublished results and additional information. Vaccines included in this review were approved in at least one country. CVnCoV and NVX-CoV2373 were in rolling review by the European Medicine Agency (EMA) and were included in this review.

Efficacy refers to the degree to which a vaccine prevents symptomatic or asymptomatic infection under controlled circumstances such as clinical trials. Effectiveness refers to how well the vaccine performs in the real world. In clinical trials, the main endpoint was the prevention of symptomatic COVID-19, whereas in observational studies endpoints were various and included asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19, hospitalization or mortality.

Regarding seroneutralization assays, we extracted the age of the study population, dosage, and fold decrease in geometric mean titre for 50% neutralization compared to the SARS-CoV-2 reference strain for each vaccine and each SARS-CoV-2 variant when it was available.

Evidence on vaccine efficacy and effectiveness

At the time of this review, 17 vaccines have been authorized in at least one country (Supplementary Material Table S1) and two vaccines (CVnCoV and NVX-CoV2373) are under evaluation.

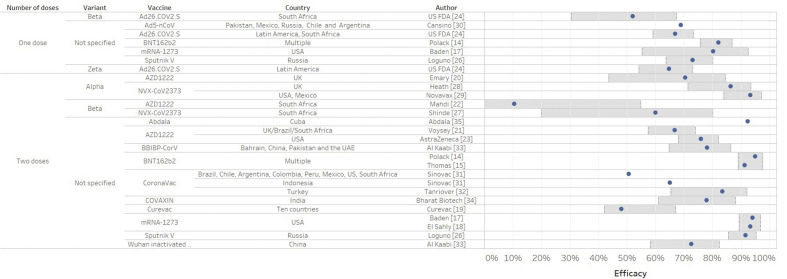

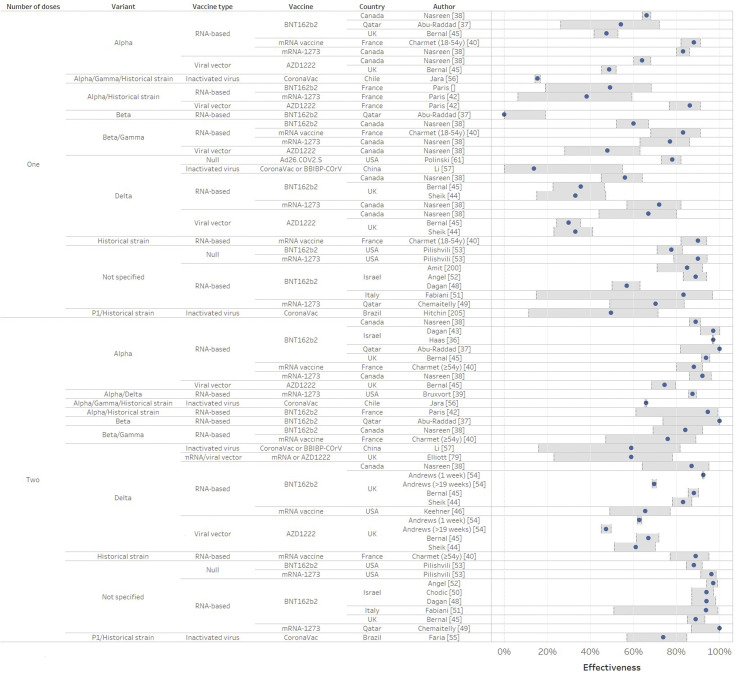

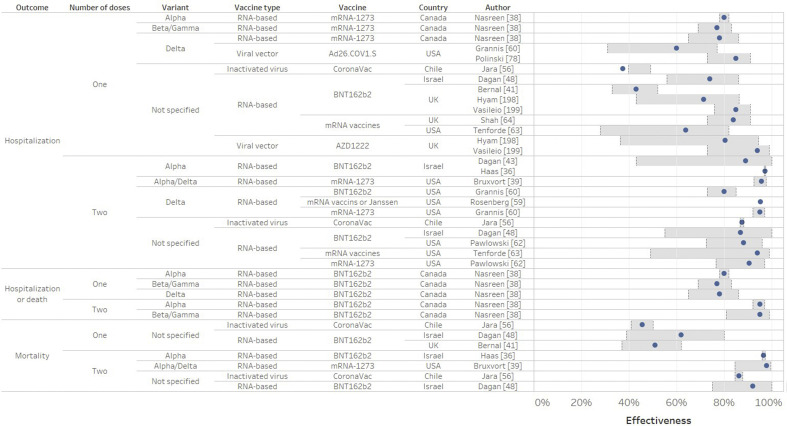

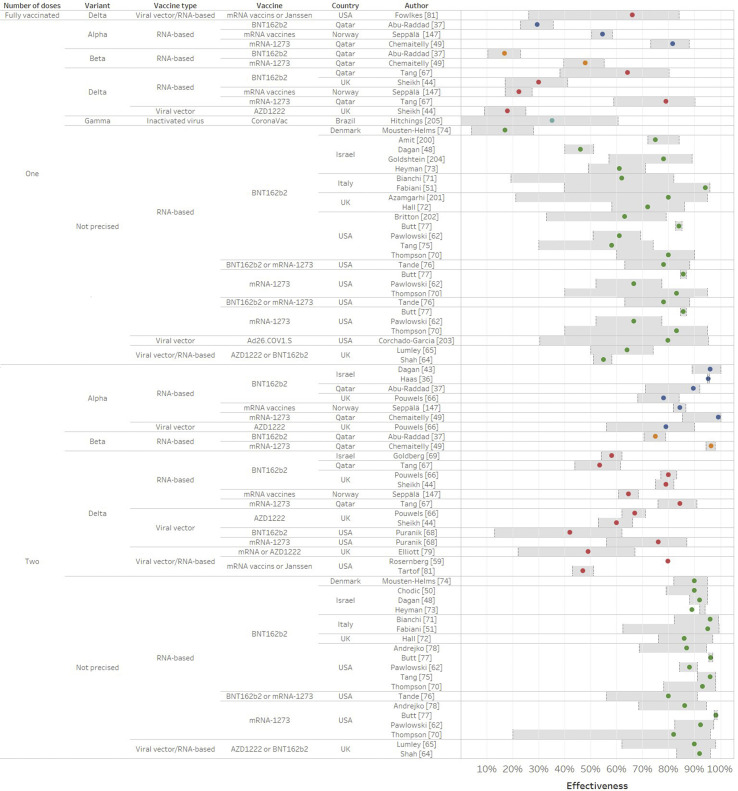

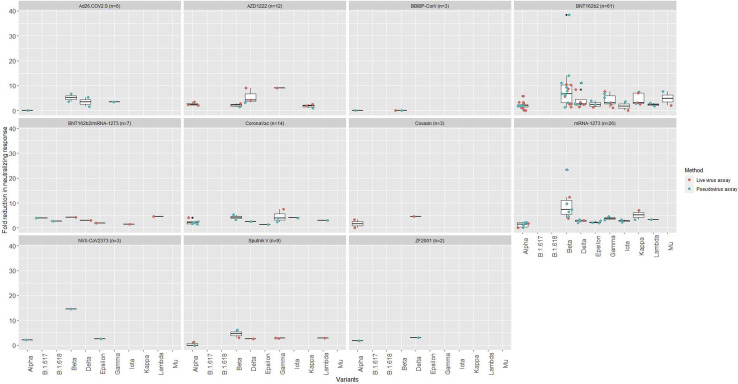

We briefly compared the COVID-19 vaccines schedule, type of vaccine, manufacturer, dosage, conditions of use/storage/transport, composition and price (Table 1 ). The main results of phase III clinical trials for each vaccine are described in Table 2 and in Fig. 1 ). Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 variants (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Epsilon, Eta, Zeta, Iota, Kappa and Delta) are described in Table 3 . The results of observational real-world studies are specified in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 and in the Supplementary Material Table S2. Seroneutralization assay results are summarized in Fig. 5 using boxplots per vaccine and per variant, and Supplementary Material Table S3 describes the 54 studies in detail.

Table 1.

Characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines

| Vaccine | Manufacturer | Type of vaccine | Dose | Injection dose interval in the phase III trial | Condition of use/storage | Composition | Cost for one dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT16b2 | Pfizer/BioNtech | RNA-based | 30 μg 5–7-dose vial 0.3 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 21 days apart |

Supplied as a frozen vial The withdrawal of 6–7 doses from a single vial is dependent, in part, on the type of syringes and needles used to withdraw doses from the vials The vaccine must be diluted Frozen vials prior to use can be stored before dilution: –80°C to –60°C up to the end of its expiry date or at –25°C to –15°C for up to 2 weeks Vials prior to dilution may be stored at +2°C to +8°C for up to 31 days or may be at room temperature up to +25°C for no more than 2 hours prior to use, or can be thawed in the refrigerator for 2–3 hours or at room temperature (up to +25°C) for 30 minutes After dilution: +2°C to +25°C Has to be used within 6 hours from the time of dilution |

A synthetic messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) encoding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, lipids ((4-hydroxybutyl)azanediyl)bis(hexane-6,1-diyl)bis(2-hexyldecanoate), 2-[(polyethylene glycol)-2000]-N,N-ditetradecylacetamide, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, and cholesterol), potassium chloride, monobasic potassium phosphate, sodium chloride, dibasic sodium phosphate dihydrate, and sucrose | EU and USA: $19.50 African Union: $6.75 Brazil: $10 Colombia: $12 |

| mRNA-1273 | Moderna | RNA-based | 100 μg 11 or 15-dose vial 0.5 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 28 days apart |

Supplied as a frozen suspension stored between –50°C to –15°C Unopened vial: +2°C to +8°C for up to 30 days +8°C to +25°C for up to 24 hours After opening: +2°C to +25°C and discarded after 12 hours |

A synthetic messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) encoding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. The vaccine also contains the following ingredients: lipids (SM-102, 1,2-dimyristoyl-rac-glycero-3-methoxypolyethylene glycol-2000 (PEG2000-DMG), cholesterol, and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC)), tromethamine, tromethamine hydrochloride, acetic acid, sodium acetate, and sucrose | EU: $25.5 USA: $15 Argentina: $21.5 Botswana: $28.8 |

| CVnCoV | CureVac | RNA-based | 12 μg | Intramuscularly 2 doses 28 days apart |

Concentrated CVnCoV will be stored frozen at –60°C (in clinical trial) CVnCoV must be diluted Unopened vial: 3 months at +2°C to +8°C Room temperature for 24 hours |

NA | NA |

| AZD1222 ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine |

AstraZeneca/University of Oxford | Non-replicating viral vector | 5 × 1010 viral particles (standard dose) 8 doses or 10 doses of 0.5 mL per vial |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 4–12 weeks apart |

Do not freeze Unopened vial: 6 months (+2°C to +8°C) After opening: no more than 48 hours in a refrigerator (+2°C to +8°C) Used at temperature up to +30°C for a single period of up to 6 hours |

Chimpanzee Adenovirus encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein (ChAdOx1-S)a, not less than 2.5 × 108 infectious units (Inf.U)a Produced in genetically modified human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and by recombinant DNA technology L-Histidine L-Histidine hydrochloride monohydrate Magnesium chloride hexahydrate Polysorbate 80 (E 433) Ethanol Sucrose Sodium chloride Disodium edetate (dihydrate) Water for injection |

$2.15 in the EU $4–6 elsewhere |

| Ad26.COV2.S | Johnson & Johnson | Non-replicating viral vector | 5 × 1010 viral particles 10 doses of 0.5 mL per vial |

Intramuscularly A single dose |

Should be protected from light Supplied as a liquid suspension Unopened vial can be stored at +2°C to +8°C until the expiration date or at +9°C to +25°C for up to 12 hours After the first dose has been withdrawn, the vial is held between +2°C and +8°C for up to 6 hours or at room temperature for up to 2 hours |

Replication-incompetent recombinant adenovirus type 26 vector expressing the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in a stabilized conformation. (5 × 1010 vp) Citric acid monohydrate, trisodium citrate dihydrate, ethanol, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HBCD), polysorbate 80, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide, and hydrochloric acid |

EU: $8.5 USA: $10 African Union: $10 |

| Gam-COVID-Vax Sputnik V |

Gamaleya Research Institute | Non-replicating viral vector | 1011 viral particles per dose for each recombinant adenovirus 0.5 mL/dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 21 days apart |

Transport: two forms: lyophilized or frozen Storage: +2°C to +8°C |

Two vector components, rAd26-S and rAd5-S Tris (hydroxymethyl) aminomethane, sodium chloride, sucrose, magnesium chloride hexahydrate, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) disodium salt dihydrate, polysorbate-80, ethanol 95%, and water for injection |

<$10 |

| NVX-CoV2373 | Novavax | Protein-based | 5 μg protein and 50 μg Matrix-M adjuvant | Intramuscularly 2 doses 21 days apart |

Shipped in a ready-to-use liquid formulation Storage: +2°C to +8°C |

SARS-CoV-2 rS with matrix-M1 adjuvant (5 μg antigen and 50 μg adjuvant) | $20.9 for Denmark COVAX: $3 |

| EpiVacCorona | VECTOR | Protein-based | 225 μg protein 0.5 mL/dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 21 days apart |

Storage between +2°C and +8°C | NA | NA |

| ZF2001 | Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Anhui Zhifei Longcom Biopharmaceutical | Protein-based | 25 μg protein 0.5 mL/dose |

Intramuscular | Storage between +2°C and +8°C | NA | NA |

| Convidecia™ Ad5-nCoV |

CanSino | Non-replicating viral vector | 1010 viral particles per 0.5 mL in a vial | Intramuscularly Single dose |

Supplied as a vial of 0.5 mL Storage between +2°C and +8°C Do not freeze |

The recombinant novel coronavirus vaccine (Adenovirus type 5 vector) Mannitol, sucrose, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, polysorbate 80, glycerin, N-(2-hydroxyethyl), piperazine-N- (2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), sterile water for injection as solvent |

Pakistan private market: $27.2 |

| CoronaVac | Sinovac Biotech | Inactivated virus | 3 μg 0.5 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 28 days apart |

Supplied as a vial or syringe of 0.5 mL Do not freeze Protect from light Storage and transport between +2°C and +8°C Shake well before use Shelf-life: 12 months |

Inactivated CN02 strain of SARS-CoV-2 created with Vero cells Aluminium hydroxide, disodium hydrogen phosphate dodecahydrate, sodium dihydrogen phosphate monohydrate, sodium chloride |

China: $29.75 Ukraine: $18 Philippines: $14.5 Brazil: $10.3 Cambodia: $10 |

| BBIBP-COrV | Sinopharm/Beijing Institute of Biological Products | Inactivated virus | 4 μg 0.5 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 21–28 days apart |

Supplied as pre-filled syringe or vial Cannot be frozen Protect from light Store and transport refrigerated (+2°C to +8°C) |

Inactivated virus 19nCoV-CDC-Tan-HB02 Excipients: disodium hydrogen phosphate, sodium chloride, sodium dihydrogen phosphate, aluminium hydroxide adjuvant |

Argentina, Mongolia: $15 Senegal: $18.6 China: $30 Hungary: $36 |

| Wuhan | Sinopharm/Chinese Academy of Science | Inactivated virus | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Covaxin | Bharat Biotech | Inactivated virus | 6 μg Single dose: 0.5 mL 10-dose or 20-dose vial |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 28 days apart |

Supplied as a single dose or multidose vial Do not freeze Stored at +2°C to +8°C |

6 μg whole-virion inactivated SARS-CoV-2 antigen (strain: NIV-2020-770), and other inactive ingredients such as aluminium hydroxide gel (250 μg), TLR 7/8 agonist (imidazoquinolinone) 15 μg, 2-phenoxyethanol 2.5 mg, and phosphate buffer saline® up to 0.5 m | India: $3-5 Brazil: $15 Botswana: $16 |

| CIGB-66 Abdala |

Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB) | Protein-based | 0.05 mg recombinant protein 0.5 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 3 doses at 0, 14, 28 days |

Supplied as a multidose vial Do not freeze Stored at +2°C to +8°C |

Recombinant protein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus receptor-binding domain (RBD) 0.05 mg Thiomersal 0.025 mg Aluminium hydroxide gel (Al³ +) Disodium hydrogen phosphate Sodium dihydrogen phosphate dihydrate Sodium chloride |

NA |

| QazVac QazCovid-In |

Kazakh Research Institute for Biological Safety Problems | Inactivated virus | — | Intramuscularly 2 doses 21 days apart |

Stored at +2°C to +8°C | NA | NA |

| Coviran Barkat | Shifa Pharmed Industrial Group | Inactivated virus | 5 μg inactivated purified virus 0.5 mL per dose |

Intramuscularly 2 doses 28 days apart |

Stored at +2°C to +8°C | Inactivated viral particles and a mixture 2% adjuvant® Alhydrogel (aluminium hydroxide) |

NA |

| KoviVac | Chumakov Center | Inactivated virus | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Composition and conditions of use references are in the Supplementary Material Table S1.

NA, not available information; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; EU, European Union.

Table 2.

Phase III trials for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines

| Vaccine | Author | Study population | Cut-off date | Main endpoint | Symptomatic COVID-19 |

Severe COVID-19 |

Hospitalization | Any unsolicited serious adverse event |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Placebo | Efficacy (%, 95%CI) | Cases among vaccine group | Cases among placebo group | Efficacy (%, 95%CI) | Vaccine | Placebo | ||||||

| BNT162b2 (RNA-based) | Polack et al. [14] | USA, Argentina, Brazil, Germany, S. Africa, Turkey ≥16 years |

27th July 2020 to 14th November 2020 Median follow-up: 2 months |

After dose 1 | 50/21 314 | 275/21 258 | 82% (75.6 to 86.9) | 0 | 4 | 88.9% (20.1 to 99.7) | NA | 0.6% | 0.5% |

| After dose 2 COVID-19 with onset at least 7 days after the second dose without prior infection |

8/18 198 | 162/18 325 | 95% (90.3 to 97.6) | 1 | 4 | 75% (–152.6% to 99.5%) | NA | 0.6% | 0.5% | ||||

| Thomas et al. [15] | 27th July 2020 to 13th March 2021 6 months follow-up |

After dose 2 COVID-19 with onset at least 7 days after the second dose without prior infection |

77/20 998 | 850/20 713 | 91.3% (89.0 to 93.2) | 1 | 23 | 95.7% (73.9 to 99.9) | NA | 1.2% | 0.7% | ||

| Frenck et al. [16] | USA 12–15 years |

15th October 2020 to 12th January 2021 2 months follow-up |

After dose 2 COVID-19 with onset at least 7 days after the second dose without prior infection |

0/1005 | 16/978 | 100% (75.3 to 100) | 0 | 0 | No cases of severe COVID-19 were observed | NA | 0.4% | 0.1% | |

| mRNA-1273 (RNA-based) | Baden et al. [17] | USA ≥18 years |

27th July 2020 to 21st November 2020 Median follow-up of 64 days |

After dose 1 | 7/996 | 39/1079 | 80.2% (55.2 to 92.5) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| After dose COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection |

11/14 134 | 185/14 075 | 94.1% (89.3 to 96.8) | 0 | 30 | 100% (no CI estimated) | 3 in the placebo group and 1 in the vaccine group | 0.6% | 0.6% | ||||

| El Sahly et al. [18] | US ≥18 years |

26th March 202 Median follow-up of 5.3 months post dose 2 |

COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection | 55/14 287 | 744/14 164 | 93.2% (91 to 94.8) | 2 | 106 | 98.2% | NA | 0.7% | 0.6% | |

| CVnCoV (RNA-based) | CureVac press communication [19] | Argentina, Belgium, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, Panama, Peru, Spain | Estimated completion date: 15th May 2022 | COVID-19 of any severity | 40 000 adults 83 cases among the vaccine group 145 cases among the placebo group |

48% | 9 | 36 | 77% against moderate and severe disease | 0 hospitalizations among the vaccine group 6 hospitalizations among the placebo group |

Ongoing | Ongoing | |

| AZD1222 (Non-replicating viral vector ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine |

Emary et al. [20] | UK | 1st October 2020 to 14th January 202 Median follow-up: not provided |

Symptomatic COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection | 59/4244 | 210/4290 | Alpha: 70.4% (43.6 to 84.5) Non-VOC lineages: 81.5% (67.9 to 89.4) |

NA | NA | NA | There were no cases of hospitalization or death | NA | NA |

| Voysey et al. [21] | UK/Brazil/South Africa ≥18 years |

23rd April 2020 to 7th December 2020 Median follow-up post dose 2: 53–90 days according to the dose gap |

Symptomatic COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection | 84/8597 | 248/8581 | 66.7% (57.4% to 74%) | 0 | 15 | Efficacy against hospitalization from 22 days after vaccination: 100% | 2 hospitalizations among the vaccine group 22 hospitalizations among the placebo group |

0.7% | 0.8% | |

| Madhi et al. [22] | South Africa ≥18 years |

24th June 2020 to 9th November 2020 Median follow-up post dose 2: 156–121 days (vaccinated – placebo) |

Mild to moderate COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection | 19/750 | 23/717 | 21.9 (–49.9 to 59.8) | 0 | 0 | No participant had severe COVID-19 | Zero hospitalizations | 14 events | 13 events | |

| Against Beta variant at least 14 days after the second dose without prior infection | 19/750 | 20/714 | 10.4% (–76.4 to 54.8) | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Press communication [23] | USA ≥18 years |

25th March 2021 | Preventing symptomatic COVID-19 | 141 symptomatic cases among 32 449 participants | 76% (68 to 82) | NA | NA | 100% | Zero hospitalizations among the vaccine group Not specified for the placebo group |

NA | NA | ||

| Ad26.COV2.S (Non-replicating viral vector) | US FDA and EMA [24,25] | Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Peru, Mexico, US, South Africa ≥18 years Variant D614G 96.4% in the US Beta (94.5% in South Africa) Variant P2 (69.4% in Brazil) |

22nd January 2021 Median follow-up of 2 months |

Prevent confirmed, moderate to severe/critical COVID-19 at least 14 days after vaccination without prior infection | 116/19 514 | 348/19 544 | All: 66.9% (59.1 to 73.4) USA: 74.4% (65 to 81.6) South Africa: 52% (30.3 to 67.4) Latin America: 64.7% (54.1 to 73) |

14 | 60 | All: 76.7% (54.6 to 89.1) | 2 hospitalizations among the vaccine group 29 hospitalizations among the placebo group |

0.4% | 0.4% |

| Prevent confirmed, moderate to severe/critical COVID-19 at least 28 days after vaccination without prior infection | 66/19 306 | 193/19 178 | All: 66.1% (55.0 to 74.8) USA: 72% (58.2 to 81.7) South Africa: 64% (41.2 to 78.7) Latin America: 61% (46.9 to 71.8) |

5 | 34 | All: 85.4% (54.2 to 96.9) | 0 hospitalizations among the vaccine group 16 hospitalizations among the placebo group |

||||||

| Gam-COVID-Vax Sputnik V (Non-replicating viral vector) |

Logunov et al. [26] | Russia ≥18 years |

7th September 2020 to 24th November 2020 Median follow-up post dose 1: 48 days |

First confirmed COVID-19 after the first dose | 79/16 427 | 96/5435 | 73.1% (63.7 to 80.1) | NA | NA | 0.3% | 0.4% | ||

| First confirmed COVID-19 after the second dose | 16/14 964 | 62/4902 | 91.6% (85.6 to 95.2) | 0 | 20 | 100% (94.4 to 100) Moderate or severe |

NA | ||||||

| NVX-CoV2373 (Protein-based) | Shinde et al. [27] | South Africa ≥18 years Beta: 90% of cases in South Africa |

17th August 2020 to 25th November, 2020 Median follow-up post dose 2: 45 days |

Preventing symptomatic COVID-19 at least 7 days after the 2nd dose without prior infection | 44/1357 | 29/1327 | All: 49.4% (6.1 to 72.8%) HIV-negative participants: 60% (19.9 to 80.1) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Heath et al. [28] | UK ≥18 years |

Median follow-up post dose 2: 3 months | Symptomatic COVID-19 at least 7 days after the 2nd dose without prior infection | 10 cases | 96 cases | 89.7% (80.2 to 94.6) 86.3% (71.3 to 93.5) against Alpha |

0 | 1 | 1 severe COVID-19 in placebo group | — | 0.5% | 0.5% | |

| Novavax press release [29] | USA and Mexico | 25th January 2021 to 30th April 2021 (Alpha predominant) Follow-up: not available |

Symptomatic COVID-19 with onset at least 7 days after the second dose without prior infection | 14 | 63 | 90.4% (82.9 to 94.6) 93.2% (83.9 to 97.1) against variants (mainly Alpha) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Convidecia™ Ad5-nCoV (Non-replicating viral vector) |

CanSino Biologics Inc document [30] | Pakistan, Mexico, Russia, Chile and Argentina ≥18 years |

8th February 2021 Follow-up: not available |

Symptomatic COVID-19 disease 14 days after single dose | NA | NA | 68.83% | NA | NA | 95.47% | NA | NA | NA |

| Symptomatic COVID-19 disease 28 days after single dose | NA | NA | 65.28% | NA | NA | 90.07% | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| CoronaVac (Inactivated virus) | Sinovac document [31] | Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia ≥18 years |

16th December 2020 Follow-up: not available |

Symptomatic COVID-19 at least 14 days after two doses | Brazil: 253 cases/12 396 health workers Turkey: 29 cases/1322 |

Brazil all: 50,65% Turkey: 83.5% Indonesia: 65% |

NA | NA | Brazil: 100% | NA | NA | NA | |

| Tanriover et al. [32] | Turkey ≥18 years |

15th September 2020 to 6th January 2021 Median follow-up (after randomization): 43 days |

Symptomatic COVID-19 at least 14 days after two doses | 9/6559 | 32/3470 | 83.5% (65.4 to 92.1) | NA | NA | NA | 1 hospitalization in the placebo group 0 hospitalizations in the vaccine group |

0.1% | 0.1% | |

| BBIBP-CorV (inactivated virus) | Al Kaabi et al. [33] | Bahrain, China, Pakistan, and the UAE ≥18 years |

16th July 2020 to 20th December 2020 Median follow-up (14 days after the 2nd dose): 77 days |

Symptomatic COVID-19, 14 days after the second dose without prior infection at baseline | 21/12 726 | 95/12 737 | 78.1 (64.8 to 86.3) | 0 | 2 | 100% (NA) | NA | 0.4% | 0.6% |

| Wuhan inactivated vaccine | Al Kaabi et al. [33] | Bahrain, China, Pakistan, and the UAE ≥18 years |

16th July 2020 to 20th December 2020 Median follow-up (14 days after the 2nd dose): 77 days |

Symptomatic COVID-19, 14 days after the second dose without prior infection at baseline | 26/12 743 | 95/12 737 | 72.8% (58.1 to 82.4) | 0 | 2 | 100% (NA) | NA | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| COVAXIN (inactivated virus) | Bharat Biotech [34] | India ≥18 years |

Median follow-up: not available | Symptomatic COVID-19, 14 days after the second dose without prior infection at baseline | 127 symptomatic cases among 25 800 participants | 78% (61 to 88) | NA | NA | 100% (60 to 100) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Abdala (Protein-based) | Press release [35] | Cuba | Median follow-up: not available | COVID-19 (not specified) | NA | NA | 92.3% | NA | — | NA | NA | NA | — |

At the time of the review, we did not find any phase III trial results published or available for QazVax (inactivated virus), KoviVac, COVIran Barekat, EpiVacCorona, ZF2001 and Sputnik V Light.

NA, no information available.

Fig. 1.

Vaccine efficacy against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection from clinical trials (in % and 95%CI) according to the number of doses. Confidence intervals are delimited by the grey rectangular area.

Table 3.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines and variants

| SARS-CoV-2 variants |

B.1.1.7 501Y.V1 |

B.1.551 501Y.V2 |

B.1.1.28.1.P1 501Y.V3 |

B.1.617.2 (and AY sublineages) |

B.1.617.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO nomenclature | Alpha | Beta | Gamma | Delta | Kappa |

| Key spike mutations | 69/70del, 144del, N501Y, A570D, D614G, P681H, T716I, S982A, D1118H | D80A, D215G, 241/243del, K417N, E484K, N501Y, D614G, A701V | L18F, T20N, P26S, D138Y, R190S, K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G H655Y, T1027I, V1176F | T19R, T95I, G142D, E156-, F157-, R158G, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, D950N ± (V70F, A222V, W258L, K417N) | G142D, E154K, L452R, E484Q, D614G, P681R, Q1071H ± (T95I) |

| First detection | UK September 2020 |

South Africa September 2020 |

Brazil and Japan December 2020 |

India December 2020 |

India December 2020 |

| Transmission compared to non-VOC/VOI | +56% in the UK [2] +56–74% in Denmark, Switzerland, US [102] 43-100% higher reproductive number [104] |

+50% in South Africa [108] | +160% in Brazil [3,6] | +40 to 60% in the UK (compared to Alpha) +97% higher reproductive number [104] |

NA |

| Risk of mortality | Increased 61–64%mortality in the UK [4] | NA | NA | May cause more severe cases than Alpha [109] | NA |

| Impact on post-vaccination sera (reduction in neutralization activity compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 or D614G) | No/minimal 0–3.3-fold reduction for BNT162b2 [9,[110], [111], [112], [113], [114], [115], [116], [117], [118], [119], [120], [121], [122]], mRNA-1273 [8,9,115,123] No reduction for Sputnik V, Covaxin, BBIBP-CorV [118,124,125] 1.5–4.1-fold reduction for CoronaVac [124,126,127] 2.1-fold reduction for AZD1222 [117] and NVX- CoV2373 [128] |

Minimal to substantial No reduction for BBIBP-CorV [124,129] 1.3–38.45-fold reduction for BNT162b2 [7,9,[110], [111], [112], [113],115,116,119,120,130] 3.3–23.45-fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [9,115,123,131,132], AZD1222 [133] 3.3–5.3-fold reduction CoronaVac [124,126] 6.1-fold reduction for Sputnik V [118] 14.5-fold reduction for NVX-CoV2373 [132] |

Minimal to moderate 1.2–7.6-fold reduction for BNT162b2 3.2–4.5-fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [110,112,115] 9-fold reduction for AZD1222 [120] 7.5-fold reduction for CoronaVac [126,127] 3.4-fold reduction for Ad26.COV2.S [134] 2.8-fold reduction for Sputnik V [135] |

3–3.9-fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [[136], [137], [138]] 1.4–11.1-fold reduction for BN162b2 [133,136,137,[139], [140], [141]] 3.1–9 for AZD1222 [133,140,142] 1.6–5.4-fold reduction for Ad26.COV2.S [134,137] 2.5-fold for CoronaVac [143] 3-fold for ZF2001 [143] 2.5-fold for Sputnik V [144] 4.6-fold for Covaxin [145]. |

2.6–7.5-fold reduction for BNT162b2 [133,136,139,146] 3.4–7-fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [138] 1–2.6-fold reduction for AZD1222 [133,139,145] |

| Effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection (fully vaccinated) | BNT162b2: 78–95% [37,48,58,66] mRNA-1273: 84–99% [49,147] AZD1222: 79% [66] |

BNT162b2: 75% [37] mRNA-1273: 96% [49] | NA | BNT162b2: 42–79% [44,[66], [67], [68], [69]] mRBA-1273: 76–84% [67,68] mRNA-vaccines: 64% [147] mRNA-vaccines/Janssen: 47–79% [59,81] AZD1222: 60–67% [44,66] mRNA/AZD-1222: 49% [79] |

NA |

| Effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalization/death (fully vaccinated) | BNT162b2n mRNA-1273: >89% [36,38,39] | BNT162b2: 95% [38] | BNT162b2: 95% [38] | BNT162b2: 80% [60] mRNA-1273: 95% [60] Ad26.COV1.S: 60–85% [60,61] mRNA-vaccines: 95% [39,59] |

NA |

| SARS-CoV-2 variants | B.1.525 |

P2 |

P3 |

B.1.526 |

B.1.427 |

B.1.429 CAL.20C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eta | Former Zeta | Former Theta | Iota | Former Epsilon | Former Epsilon | |

| Key spike mutations | Q52R, A67V, 69/70del, 144del, E484K, D614G, Q677H, F888L | E484K, D614G, V1176F | 141/143del, E484K, N501Y, D614G, P681H, E1092K, H1101Y, V1176F | L5F, T95I, D253G, D614G, A701V+(E484K or S477N) | S13I, W152C, L452R, D614G | S13I, W152C, L452R, D614G |

| First detection | Multiple countries December 2020 |

Brazil | Philippines January 2021 |

USA December 2020 |

USA September 2020 |

USA September |

| Transmission | NA | NA | NA | NA | +18.6 to 24% in California [148] | +18.6 to 24% in California [148] |

| Risk of mortality | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Impact on post-vaccination sera (reduction in neutralization activity) | NA | NA | NA | 0 to 3.6 fold reduction for BNT162b2 [149,150] 1.4 to 3.3 fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [138,149] 4 fold reduction for CoronaVac [126] |

2.3 fold reduction for BNT162b2 [122] | 1.3 to 4 fold reduction for BNT162b2 [148,151,152] 2 to 2.8 for mRNA-1273 [132,138,151] 2.5 fold reduction for NVX-CoV2373 [132] 1.3 fold reduction for CoronaVac [126] |

| Effectiveness against infection (full vaccinated) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Effectiveness against hospitalization/death (full vaccinated) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| SARS-CoV-2 variants | B.1.621 |

C.37 |

|---|---|---|

| Mu | Lambda | |

| Key spike mutations | R346K, E484K, N501Y, D614G, P681H | L452Q, F490S, D614G |

| First detection | Colombia January 2021 |

Peru December 2020 |

| Transmission | NA | NA |

| Risk of mortality | NA | NA |

| Impact on post-vaccination sera (reduction in neutralization activity) | 2–7.6-fold reduction for BNT162b2 [122,153] | 3.1-fold reduction for CoronaVac [127] 1.7–4.6-fold reduction for BNT162b2 [122,150,154] 3.3–4.6-fold reduction for mRNA-1273 [154] 2.9-fold reduction for Sputnik V [135] |

| Effectiveness against infection (full vaccinated) | NA | NA |

| Effectiveness against hospitalization/death (full vaccinated) | NA | NA |

NA, not available.

Fig. 2.

Vaccine effectiveness against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) asymptomatic or symptomatic infection from real-world studies (in % and 95%CI) according to the number of doses. Confidence intervals are delimited by the grey rectangular area.

Fig. 3.

Vaccine effectiveness against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) hospitalization or death from real-world studies (in % and 95%CI) according to the number of doses. Confidence intervals are delimited by the grey rectangular area.

Fig. 4.

Vaccine effectiveness against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection from real-world studies (in % and 95%CI) according to the number of doses. Confidence intervals are delimited by the grey rectangular area. Blue, orange, red, pale blue, green refer to Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma and unsequenced strains, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Average fold reduction in neutralizing response against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variant versus wild type/D614G SARS-CoV-2 for each coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine in 54 seroneutralization assays. The line in the middle of the box is the median. The box edges are the 25th and 75th percentiles. These boxplots included different methods assessing neutralizing antibody titres. Methods are detailed in the Supplementary Material Table S2.

Randomized clinical trials on vaccine efficacy

In phase III trials (Table 2 and Fig. 1), all the main outcomes were efficacy against symptomatic infection after the second dose. In most trials, the strain was not sequenced.

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines

mRNA-based drugs are new but not unknown. In 1990, the direct injection of mRNA in mouse muscle cells proved the feasibility of mRNA vaccines [12]. mRNA instability, high innate immunogenicity and delivery issues were the main obstacles. BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were the first authorized mRNA-based vaccines. They contain the mRNA of the antigen of interest which enters cells and is translated into the spike protein to induce an immune response. Against the historical strain, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines had an efficacy of >90% at 5–6 months' follow-up post second dose, whereas CVnCoV had a lower efficacy of 48%.

Viral vector vaccines

Viral vectors are delivery systems containing nucleic acid encoding an antigen. AZD1222, Ad5-nCoV and Sputnik V had an efficacy of 65–91.6% against the historical strain. AZD1222 had an efficacy of 70.4 against Alpha. Ad26.COV2.S had an efficacy of 69.4% in Brazil (mainly P2). AZD1222 and Ad26.COV2.S had efficacies of 10.4% and 64.7%, respectively, against Beta in South Africa.

Inactivated and protein subunit vaccines

Inactivated vaccines are whole viruses that cannot infect cells and replicate [13]. Subunit vaccines are made of fragments of proteins or polysaccharides. NVX-COV2373 had an efficacy of 89–91.6% against the historical strain, 86.3–93.2% against Alpha and 60% against Beta. CoronaVac, BBIBP-CorV, Wuhan inactivated vaccine, Covaxin and Abdala had an efficacy of 50.6–92.3% but the SARS-CoV-2 strains were not specified. KoviVac, Barekatn QazVac, RBD-Dimer, EpiVacCorona had no phase III trial data published at the time of this review.Real world studies.

Post-marketing surveillance studies results are summarized in Table 3 and detailed in Supplementary Material Table S2. Most studies have a follow-up of 90 days post-vaccination.

Effectiveness against COVID-19 (symptomatic infection)

After full immunization, mRNA vaccine effectiveness against disease was 88–100% against Alpha [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43]], 76–100% against Beta/Gamma [37,38,40], 47.3–88% against Delta [38,[44], [45], [46], [47]], and 89–100% when SRAS-CoV-2 strain was not sequenced [40,41,[48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53]] (Fig. 2). AZD1222 effectiveness against disease was 74.5% against Alpha [45] and 67% against Delta [44,54] in the UK. CoronaVac effectiveness was 36.8–73.8% against Alpha/Gamma/D614G strain in Chile and Brazil [[55], [56], [205]]. CoronaVac or BBIBP-COrV administration was associated with an effectiveness of 59% in China [57].

Effectiveness against COVID-19-related hospitalization and death

After full immunization (Fig. 3), mRNA vaccine or AZD1222 effectiveness against hospitalization or death was over 87–94% [48,58] when the strain was not sequenced, 89–95% against Alpha [36,38,39], 95% against Beta/Gamma [38], 96% against Alpha/Delta [39], and 80–95% against Delta [59,60]. CoronaVac was very effective against hospitalization (87.5%) and mortality (86.3%) after full immunization [56]. Ad26.COV1.S had an effectiveness of 60–85% against Delta [60,61].

Overall, the effectiveness of mRNA-vaccine and CoronaVac was reduced for Delta infection, but they still offered a high level of protection against severe COVID-19 and hospitalization for all variants after full immunization [36,38,39,43,48,56,59,62,63].

Effectiveness against asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection

After full immunization, effectiveness was 90–92% for AZD1222 and BNT162b2 against unspecified strains [64,65] (Fig. 4). For mRNA vaccines, effectiveness against infection was 89.5–99.2% against Alpha [36,37,48,49,49,66], 75–96.4% against Beta [37,49], 42–84.4% against Delta [44,[66], [67], [68], [69]] and 80–98.2% against unspecified strains [48,50,51,62,[70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78]]. AZD1222 had an effectiveness of 49–67% in the UK [44,66,79]. mRNA vaccines and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines in the USA had an effectiveness of 47–80% against Delta [59,80,81]. Among pregnant women, a single dose or two doses led to an effectiveness of 78% against the original strain and 96% against Alpha, respectively. These previous studies focused on ≤6 years in people, but a retrospective cohort of teenagers aged 12–15 years in Israel also reported a high effectiveness of 91.5% against Delta infections [82].

Impact on viral load, infectivity, transmission and long COVID

Before Delta propagation, mRNA vaccines were associated with a lower viral load and a reduced duration of illness [83,84]. Against Delta, surveillance studies in the US found both vaccinated and unvaccinated people had similarly low cycle threshold (Ct) values, indicating high viral load [85,86]. However, the large UK REACT-1 study—using random sampling and including participants who tested positive without showing symptoms—showed that vaccinated people had a lower viral load on average [79]. A preprint in Singapore found that BNT162b2 vaccination was associated with a faster decline in viral loads among vaccinated people [87]. Ad26.COV2.S and BNT162b2 vaccines were associated with a lower probability of viral culture positivity, suggesting less shedding of infectious Delta virus in vaccinated people [88]. Before the spread of Delta, a study in England reported a reduced transmission associated with BNT162b2 or AZD1222 vaccines in a household setting [89], and two other preliminary analyses confirmed these results [90,91]. A Chinese preprint analysed infections among 5153 participants with 73 close-contact COVID-19 cases and observed a higher infection risk among unvaccinated or partially vaccinated participants (versus two doses of inactivated vaccines) [92]. In a large nested case–control study from the UK, participants with one or two vaccine doses reported having fewer symptoms and lower odds of having long COVID (symptoms over 28 days, OR =0.51 (95%CI: 0.32 to 0.82, after two doses) [93].

Waning immunity

Several studies have suggested that the levels of antibodies after BNT162b2, mRNA-1273 and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines could last for at least 6 months but decrease over time thereafter [[94], [95], [96], [97]]. For mRNA-1273, at 6 months neutralizing activity was maintained against Alpha, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, whereas neutralizing activity was considerably decreased against Beta for half the participants [97].

Observational studies stratified by time since vaccination identified a decreasing effectiveness at 4–6 months (42–57%) for mRNA vaccines and 47.3% for AZD1222 against Delta infection [54,68,69,81]. In the USA, effectiveness of mRNA vaccines against symptomatic infection fell from 94.3% in June to 65.5% in July 2021. The effectiveness against hospitalization remained high (>85%) for mRNA-1273 (92%), BNT162b2 (77–93%) and AZD-1222 (70.3%) at 4–6 months after full vaccination [54,69,81,98] and 68% at >28 days after full immunization for Ad26.COV2.S [98]. It is difficult to know whether the reduction in effectiveness against Delta infection is due to waning immunity over time or/and variants escaping immunity and/or increasing in collective immunity.

Neutralization assays with variants of concern and variants of interest

Mutations and variations occur in the SARS-CoV-2 virus due to evolution and adaptation processes [99]. Some SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern with mutations in the spike protein have an increased transmissibility [[100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105]], which may be explained by an enhanced spike-protein-binding affinity for the ACE2 receptor. For example, Alpha and Beta have been shown to have a 1.98x and 4.62x greater binding affinity than original strain [106]. These variants may cause more severe disease [4] and/or have a potential ability to escape the host or vaccine-induced immune response [7,10]. Results from several seroneutralization assays assessing the neutralizing response of vaccine-induced antibodies are described in Fig. 5 and in Supplementary Material Table S3. In general, Alpha had a minimal impact on neutralization activity of antibodies by post-vaccination sera (Table 3). Neutralization was further reduced for variants with mutation E484K and Gamma. Beta had the highest reduction in neutralizing titres. Data were lacking for C.1.2 identified in South Africa in May 2021, but C.1.2 had a 1.7-fold higher substitution rate than the current global substitution rate [107].

Limitations of neutralizing assays

Limitations concerning neutralizing assays should be emphasised. First, most studies were preprints. Second, results are not necessarily linked to clinical consequences. However, one study based on seven vaccines reported a high correlation between neutralization titres and protection estimated in phase III trials [155]. A 50% protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection corresponded to a neutralization level of 20.2% of the mean convalescent level. Third, the methods of the studies varied (pseudovirus assay, plaque reduction neutralization testing, microneutralization assay, focus reduction neutralization test). We included 28 pseudovirus assays and 26 live virus assays. Pseudovirus assays approximate authentic SARS-CoV-2 neutralization and only evaluate neutralizing antibodies on pseudoviruses with mutations in the spike protein. Additionally, the choice of cell lines and virus models (vesicular stomatitis virus or human immunodeficiency virus-1 for example) can impact the neutralizing activity. Pseudoviruses are surrogates and cannot complete the same life cycle as the live virus, thus it is not possible to assess the inhibitory effect on viral replication, but they are used to study virus entry into cells. Live virus neutralization assay remains the reference standard, but it needs a higher safety level (a biosafety level 3 laboratory). Fourth, the time post-vaccination and study populations were not always comparable regarding age or COVID-19 history. Fifth, T-cell responses were not assessed. Most studies on in vitro vaccine efficacy focused on the ability of the vaccine antibodies to bind to the virus, which partially reflect vaccine effectiveness, but cell-mediated immunity should also be considered. Studies have shown that BNT162b2 and Ad26.COV2.S induce CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses [94,156]. Preliminary reports have identified vaccine-induced CD4+ T cells 6 months after the second dose of RNA-1273 [157] and memory B cells at 6 months after two doses of BNT162b2 [158]. SARS-CoV-2-specific memory T cells and B cells are important for long-term protection. A main limitation of these studies on cell-mediated immunity is small sample size.

Vaccine regimens

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination

Changing recommendations for young people regarding use of AZD1222 and the need to accelerate the vaccination campaign has led some countries to advise heterologous prime-boost vaccination with a second dose of mRNA vaccines. An RCT conducted in the UK indicated an increase in systemic reactogenicity in a heterologous vaccination context versus homologous vaccination [159], but efficacy data have not yet been published. A press communication from El Instituto de Salud Carlos III from a phase II trial in Spain showed that the combination of AZD1222 and BNT162b2 induced a strong humoral response when compared to no second dose [160]. The Com-Cov randomized trial also supported flexibility in the use of AZD1222 and BNT162b2 with a 28-day interval inducing similar levels of SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike IgG [161]. A preliminary study in Thailand observed an increase in neutralizing antibodies against Delta after a third dose of BNT162b2 or AZD1222 among participants who received two doses of CoronaVac [162].

Extension of the dose interval

More generally, evidence on the extension of the interval between doses is scarce. Trials for AZD1222 showed that a longer delay was better, but for mRNA and other vaccines trials did not test different dose gaps [163]. A preprint reported that extending the interval to 6 weeks for BNT162b2 vaccine led to higher titres in neutralizing antibodies and a sustained T-cell response against the variants of concern [164]. Another analysis found that a second dose at 12 weeks induced a stronger humoral response than at a 3-week interval among older people [165].

A booster dose for specific populations

Immunogenicity studies amongst transplant patients and patients with cancer showed a poor antibody response after a single dose or two doses of Pfizer vaccine [[166], [167], [168]]. Facing this issue, French, German, British and US health authorities have recommended a third dose for immunocompromised people and transplant recipients. A randomized trial in transplant recipients showed that a third dose of mRNA-1273 was safe, and 26 out of 59 participants who had negative antibody responses prior to the booster developed antibody responses after the third dose [169]. However, this study did not look at the cellular immune response. Another study found that an additional dose of mRNA-1273 induced a serological response among 50% of kidney transplant recipients who hadn't responded after two doses [170]. A case–control study in preprint found an effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection 14–20 days after the third dose increased by 79% (versus the second dose) [171]. Another observational study in Israel found that a booster dose reduced the rate of confirmed infections and severe disease by a factor of 11.3 and 19.5, respectively, among elderly participants [172]. Two studies also showed that Moderna boosters (at least 6 months after the second dose) and Pfizer booster (8–11 months after the second dose) induced a strong humoral response against Beta [173] and other variants of concern [174]. The expected local and systemic adverse events were mild and moderate and similar to those after the second dose.

Vaccination of previously infected individuals

Several neutralization assays have suggested that a single dose of BNT16b or mRNA-1273 among previously infected subjects could boost the cross-neutralization response against emerging variants such as Alpha, Beta or Gamma [121,175]. These studies have demonstrated the potential benefits of vaccinating both non-infected and previously infected people. Finally, several studies have suggested that a single dose of mRNA vaccine may be sufficient to boost the antibody response in previously infected subjects and that the benefit of the second dose may be small [[176], [177], [178], [179], [180]].

Severe adverse events

The main severe adverse events reported in pharmacovigilance systems and post-authorization studies are summarized in Table 4 . Among adults, the main severe adverse events reported were very rare: anaphylaxis (2.5–4.8 cases per million doses among adults) and myocarditis (6–27 cases per million) for mRNA vaccines; thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome for the Janssen vaccine (three cases per million) and AstraZeneca vaccine (two cases per million), and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) (7.8 cases per million) for the Janssen vaccine. For AZD1222, capillary leak syndrome was also identified as a possible adverse effect, and multisystem inflammatory syndrome is under investigation. The EMA excluded an association between AZD1222 and menstrual disorders [181].

Table 4.

Main severe adverse events following coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination in observational studies and pharmacovigilance systems

| Vaccine | Serious adverse events | Cases per million doses administered | Country | Age | Follow-up | Number of participants or doses studied | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | Anaphylaxis | 4.8/million | USA | ≥12 years | 14th December 2020 to 26th June 2021 | 11.8 million doses administered (57% BNT162b2) to 6.2 million individuals | Klein et al. [186] |

| Anaphylaxis + anaphylactoid reactions | 476 cases among 40 million doses | UK | ≥16 years | 9th December 2020 to 1st September 2021 | 40 million doses (1 and 2) | MHRA (Yellow Card Scheme) [187] | |

| Myocarditis Lymphadenopathy Appendicitis Herpes zoster infection |

2.7/100 000 78.4/100 000 5/100 000 15.8/100 000 |

Israel | ≥16 years | 20th December 2020 to 24th May 2021 | 1 736 832 participants (884 828 vaccinated) | Barda et al. [188] | |

| Bell's palsy Myocarditis/Pericarditis Transverse myelitis |

2.6/100 000 0.86/100 000 0.01/100 000 |

Hongkong | ≥12 years | Up to 31st August | 4 776 700 doses | Hongkong Drug Office [189] | |

| Myocarditis Pericarditis |

6/million 4.9/million |

UK | ≥16 years | 9th December 2020 to 1st September 2021 | 40 million doses (1 and 2) | MHRA (Yellow Card Scheme) [187] | |

| mRNA-1273 | Anaphylaxis | 5.1/million | USA | ≥12 years | 14th December 2020, to 26th June 2021 | 11.8 million doses administered (43% mRNA-1273) to 6.2 million individuals | Klein et al. [186] |

| 2.5/million | USA | ≥16 years | 21st December 2020 to 10th January 2021 | 4 041 396 doses | US CDC [190] | ||

| Myocarditis Pericarditis |

20.4/million 14.8/million |

UK | ≥18 years | 9th December 2020 to 1st September 2021 | 2.3 million doses (1 and 2) | MHRA (Yellow Card Scheme) [187] | |

| Curevac | Not authorized | ||||||

| AZD1222 | Thromboembolic events | 0.61/million | India | ≥18 years | Date not specified | Retrospective survey of 75 random subjects | Rajpurohit et al. [191] |

| Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome Capillary Leak Syndrome Myocarditis Pericarditis Anaphylaxis or anaphylactoid reactions |

14.9/million 20.5/million 12 cases among 48,9 million doses 2.1/million 3.3/million 816 cases among 48.9 million doses |

UK | ≥18 years 18–49 ≥18 years |

9th December 2020 to 1st September 2021 | 48.9 million doses (1 and 2) | MHRA (Yellow Card Scheme) [187] | |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 833 cases among 592 million doses | Worldwide | ≥18 years | By 25th July 2021 | 592 million doses | EMA [181] | |

| Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome | 1503 cases among 592 million doses | Worldwide | ≥18 years | By 25th July 2021 | 592 million doses | EMA [181] | |

| Janssen | Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome Guillain–Barré syndrome |

45 cases for 14.3 million doses (3/million) 185 cases for 14.3 millions |

USA | ≥18 years | As of 1st September2021 | 14.3 million doses | US CDC [192] |

| Sputnik V | Expected local and systemic reactions The most frequent symptoms were local pain, asthenia, headache, and joint pain |

2.1% participants suffered severe reactions in San Marino's population | Republic of San Marino | 18–89 years | 4th March to 8th April 202 | Cohort of 2558 participants | Montalti et al. [193] |

| 5% of serious adverse events (n = 34) | Argentina | 18–80 years | 5th January to 20, 2021 | 707 participants | Pagotto et al. [194] | ||

| NVX-CoV2373 | Not authorized | ||||||

| EpiVacCorona | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

| ZF2001 | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

| Convidecia | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

| CoronaVac | Bell's palsy Encephalopathy |

3.8/100 000 0.01/100 000 |

Hong Kong | ≥12 years | Up to 31st August | n = 2 811 500 doses | Hongkong Drug Office [189] |

| Anaphylaxis Thromboembolic events Bell's palsy Guillain–Barré syndrome |

2/million 1.15/million 8.73/million 0.29/million |

Chile | ≥16 years | 24th December 2020 to 14th May 2021 | n = 13 862 155 doses | Instituto de Salu Publica de Chile (ISP) [195] | |

| BBIBP-COrV | No serious side effects were reported | — | Jordan | Mean age: 35–40 years | No date specified | Retrospective survey of 409 participants | Abu-Hammad et al. [196] |

| No severe side effects were reported. | — | Iraq | ≥18 years | April 2021 | Retrospective cross-sectional study of 1012 participants | Almufty et al. [197] | |

| Covaxin | Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and a retrospective cohort reported no serious adverse effects associated to Covaxin | — | India | ≥18 years | No date specified | — Retrospective survey of 75 random subjects |

Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Rajpurohit et al. [191] |

| CIGB-66 | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

| QaeVac | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

| COVIran Barkat | We did not find any comparative studies addressing post-authorization safety | ||||||

Occurrence of adverse events changes with age. Myocarditis associated with mRNA vaccination was identified mainly among males aged <30 years with 39–47 cases per million vaccine doses in the USA (versus three to four myocarditis cases expected among male aged ≥30 years) [182]. On 23rd April, the EMA estimated two cases of thrombosis with thrombocytopenia (TTS) associated with AZD1222 per 100 000 doses for people aged 20–49 years, one case/100 000 doses for those aged 50–69 years, and even lower case rates (<1/100 000 doses) for older people. Similarly, the case rate of TTS was higher for the Janssen vaccine among young women. Surveillance studies found rare cases of Bell's palsy (3.8 cases per 100 000), anaphylaxis (two cases per million), thromboembolic event (1.2 cases per million), GBS (0.29 cases per million) associated with CoronaVac. Several observational and survey studies with low sample sizes did not find specific severe adverse events for Sputnik V, BBIBP-COrV, or Covaxin. Studies on adverse events were lacking for CIGB-66, QazVac, COVIran, Barkat, ZF2001, and EpiVacCorona. Pregnant women were excluded from clinical trials, but surveillance systems did not report an excess of adverse pregnancy and neonatal events after mRNA vaccination [183,184], while an increased risk of severe COVID-19 in pregnancy and babies' admission in the neonatal unit was consistently observed [185].

Limitations of this review

This review has several limitations. Several analyses were not peer-reviewed, and only press communications or regulatory market authorization files were available for CoronaVac, BBIBP-CorV, Wuhan inactivated vaccine, Covaxin and NVX-CoV2373. Clinical trials used different definitions for COVID-19 and different primary endpoints, which make direct comparisons difficult. Janssen's primary endpoint is moderate/severe/critical COVID-19 whereas Pfizer and Moderna included mild COVID-19. The endpoint time was also heterogeneous across trials, but most trials used 14 days after the full immunization.

Observational studies, unlike randomized studies, cannot guarantee comparability in the exposition of different populations to SARS-CoV-2 and to the variants of concern. Indeed, real-world studies present large variations in time post-vaccination, exposition to SARS-CoV-2 strain, susceptibility to infection (previously infected or not), study population (healthcare workers, older adults, immunocompromised patients, those with chronical medical conditions, etc.). Moreover, due to a lack of randomization, observational studies are subject to bias when assessing effectiveness, such as misclassification from diagnostic errors, imbalances in socioeconomic status, exposure risk, healthcare-seeking behaviours, or immunity status between vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. Not all the observational studies used adjustments to take into account confounding biases. For example, healthcare workers treating COVID-19 patients may be more frequently exposed to SARS-CoV-2, leading to decreased estimates of effectiveness. Various designs—cohort, case–control study, test-negative design (TND)—were used in observational studies, each of them having limitations. Cohorts require large sample sizes for uncommon outcomes (i.e. severe COVID-19), but vaccination status may be more difficult to determine in retrospective cohorts. In case–control studies, vaccinated people may be more likely to seek health care and SARS-CoV-2 testing, biasing toward a reduction in the estimation of effectiveness.

Conclusion

To date, the availability of data varies greatly depending on the vaccine considered. mRNA vaccines, AZD1222, Ad26.COV2.S, Sputnik V, NVX-CoV2373, Ad5-nCoV, BBIBP-COrV, CoronaVac, COVAXIN and Wuhan inactivated vaccine showed an efficacy against COVID-19 in >50% in phase III studies. Most observational studies assessed the mRNA vaccines, CoronaVac and AZD1222 which appear to be safe and highly effective tools to prevent severe disease, hospitalization and death against all variants of concern (Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta). Large observational studies were lacking for several authorized vaccines: Sputnik V, Sputnik V Light, BBIBP-CorV, COVAXIN, EpiVacCorona, ZF2001, Abdala, QazCovid-In, Wuhan Sinopharm inactivated vaccine, KoviVac and COVIran Barekat. The protection against symptomatic and asymptomatic infection was high for Alpha, Beta and Gamma for mRNA vaccines and AZD1222. mRNA vaccines and Ad26.COV2.S were associated with a faster decline in viral load against several variants, including Delta, and a lower probability of viral culture positivity. Effectiveness against infection and COVID-19 declined following infection with the Delta variant and over time, possibly due to a waning of immunity.

Heterologous prime-boost vaccination and a third dose of vaccine both induced a strong humoral response. Vaccinating previously infected people with a single dose provided an equivalent neutralizing response compared to people vaccinated with two doses against all the variants.

According to safety monitoring, reported serious adverse events were very rare and the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination far outweighed the potential risks.

More research is needed to consider booster doses, heterologous vaccination, dosing intervals, vaccine breakthrough infections, and duration of vaccine immunity against variants of concern.

Author contributions

TF and NPS designed and conducted the research. TF wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors (TF, YK, CJM, JG, NPS) contributed to the data interpretation, revised each draft for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Transparency declaration

All authors declare no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. Thibault Fiolet received a PhD grant from the Fondation Pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) n°ECO201906009060. This funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Editor: L. Kaiser

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.World Health Organization Draft landscape and tracker of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/draft-landscape-of-covid-19-candidate-vaccines [Internet]. [cité 30 mai 2021]

- 2.Volz E., Mishra S., Chand M., Barrett J.C., Johnson R., Geidelberg L., et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coutinho R.M., Marquitti F.M.D., Ferreira L.S., Borges M.E., Silva RLP da, Canton O., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Model-based estimation of transmissibility and reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 P.1 variant. 23rd March. 2021.03.03.21252706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies N.G., Jarvis C.I., Edmunds W.J., Jewell N.P., Diaz-Ordaz K., Keogh R.H. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021:1–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challen R., Brooks-Pollock E., Read J.M., Dyson L., Tsaneva-Atanasova K., Danon L. Risk of mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/1: matched cohort study. BMJ. 2021;372:n579. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faria N.R., Mellan T.A., Whittaker C., Claro I.M., Candido D. da S., Mishra S., et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science. 2021;372:815–821. doi: 10.1126/science.abh2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Planas D., Bruel T., Grzelak L., Guivel-Benhassine F., Staropoli I., Porrot F., et al. Sensitivity of infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants to neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2021;27:917–924. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edara V.V., Hudson W.H., Xie X., Ahmed R., Suthar M.S. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants after infection and vaccination. JAMA. 2021;325:1896–1898. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.4388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang P., Nair M.S., Liu L., Iketani S., Luo Y., Guo Y., et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593:130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cele S., Gazy I., Jackson L., Hwa S.-H., Tegally H., Lustig G., et al. Escape of SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 from neutralization by convalescent plasma. Nature. 2021;593:142–146. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03471-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wibmer C.K., Ayres F., Hermanus T., Madzivhandila M., Kgagudi P., Oosthuysen B., et al. SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 escapes neutralization by South African COVID-19 donor plasma. Nat Med. 2021;27:622–625. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01285-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff J.A., Malone R.W., Williams P., Chong W., Acsadi G., Jani A., et al. Direct gene transfer into mouse muscle in vivo. Science. 1990;247:1465–1468. doi: 10.1126/science.1690918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plotkin S. History of vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:12283–12287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400472111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polack F.P., Thomas S.J., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas S.J., Moreira E.D., Kitchin N., Absalon J., Gurtman A., Lockhart S., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine through 6 months. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frenck R.W., Klein N.P., Kitchin N., Gurtman A., Absalon J., Lockhart S., et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine in adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:239–250. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baden L.R., Sahly H.M.E., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Sahly H.M., Baden L.R., Essink B., Doblecki-Lewis S., Martin J.M., Anderson E.J., et al. Efficacy of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at completion of blinded phase. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2113017. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CureVac . 2021. Press release. CureVac Final Data from Phase 2b/3 Trial of First-Generation COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate, CVnCoV, Demonstrates Protection in Age Group of 18 to 60 [Internet]https://www.curevac.com/en/2021/06/30/curevac-final-data-from-phase-2b-3-trial-of-first-generation-covid-19-vaccine-candidate-cvncov-demonstrates-protection-in-age-group-of-18-to-60/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emary K.R.W., Golubchik T., Aley P.K., Ariani C.V., Angus B., Bibi S., et al. Efficacy of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern 202012/01 (B.1.1.7): an exploratory analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:1351–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voysey M., Clemens S.A.C., Madhi S.A., Weckx L.Y., Folegatti P.M., Aley P.K., et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet. 2021;397:99–111. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madhi S.A., Baillie V., Cutland C.L., Voysey M., Koen A.L., Fairlie L., et al. Efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.351 variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1885–1898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2102214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AstraZeneca . 2021. AZD1222 US Phase III trial met primary efficacy endpoint in preventing COVID-19 at interim analysis [Internet]https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2021/astrazeneca-us-vaccine-trial-met-primary-endpoint.html [cité 11 sept 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US FDA . 2020. Janssen Ad26.COV2.S (COVID-19. Vaccine VRBPAC briefing document.https://www.fda.gov/media/146217/download 26 févr [cité 29 mars 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Medicines Agency . 2021. Assessment report. COVID-19 vaccine Janssen. 11 mars.https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/covid-19-vaccine-janssen-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf [cité 29 mars 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Logunov D.Y., Dolzhikova I.V., Shcheblyakov D.V., Tukhvatulin A.I., Zubkova O.V., Dzharullaeva A.S., et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397:671–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shinde V., Bhikha S., Hoosain Z., Archary M., Bhorat Q., Fairlie L., et al. Efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.351 variant. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1899–1909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heath P.T., Galiza E.P., Baxter D.N., Boffito M., Browne D., Burns F., et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1172–1183. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Novavax . 2021. Novavax COVID-19 vaccine demonstrates 89.3% efficacy in UK phase 3 trial | Novavax Inc. - IR Site [Internet]https://ir.novavax.com/news-releases/news-release-details/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-demonstrates-893-efficacy-uk-phase-3 [cité 29 mars 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CanSino Biologics Inc . 2021. Inside information NMPA’s acceptence of application for conditional marketing authorization of recombinant novel coronavirus vaccine (Adenovirus Type 5 Vector)http://www.cansinotech.com/upload/1/editor/1614144655221.pdf 24 févr. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinovac Biotech Ltd . 2021. Sinovac announces phase III results of Its COVID-19 vaccine-SINOVAC - supply vaccines to eliminate human diseases [Internet]http://www.sinovac.com/?optionid=754&auto_id=922 [cité 28 mars 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanriover M.D., Doğanay H.L., Akova M., Güner H.R., Azap A., Akhan S., et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01429-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al Kaabi N., Zhang Y., Xia S., Yang Y., Al Qahtani M.M., Abdulrazzaq N., et al. Effect of 2 inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines on symptomatic COVID-19 infection in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326:35–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.8565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bharat Biotech . 2021. Bharat biotech announces phase 3 results of COVAXIN®: India’s first COVID-19 vaccine demonstrates interim clinical efficacy of 81% [Internet]https://www.bharatbiotech.com/images/press/covaxin-phase3-efficacy-results.pdf [cité 29 mars 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Centro de Ingeniería Genética y Biotecnología. Vacuna Abdala . CIGB; 2021. 100% de eficacia ante la enfermedad severa y la muerte en su ensayo fase III [Internet]https://www.cigb.edu.cu/product/abdala-cigb-66/ [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haas E.J., Angulo F.J., McLaughlin J.M., Anis E., Singer S.R., Khan F., et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abu-Raddad L.J., Chemaitelly H., Butt A.A. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:187–189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nasreen S., He S., Chung H., Brown K.A., Gubbay J.B., Buchan S.A., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against variants of concern. 2021.6.28.21259420. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruxvoort K., Sy L.S., Qian L., Ackerson B.K., Luo Y., Lee G.S., et al. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2021. Real-world effectiveness of the mRNA-1273 vaccine against COVID-19: interim results from a prospective observational cohort study [Internet]https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3916094 Report No. ID 3916094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charmet T., Schaeffer L., Grant R., Galmiche S., Chény O., Von Platen C., et al. Impact of original, B.1.1.7, and B.1.351/P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineages on vaccine effectiveness of two doses of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: results from a nationwide case-control study in France. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;8:100171. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernal J.L., Andrews N., Gower C., Robertson C., Stowe J., Tessier E., et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case–control study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paris C., Perrin S., Hamonic S., Bourget B., Roué C., Brassard O., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA-BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccines against COVID-19 in health care workers: an observational study using surveillance data. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;S1198–743X:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dagan N., Barda N., Biron-Shental T., Makov-Assif M., Key C., Kohane I.S., et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Nat Med. 2021;27:1693–1695. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheikh A., McMenamin J., Taylor B., Robertson C. SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 2021;397:2461–2462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01358-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernal J.L., Andrews N., Gower C., Gallagher E., Simmons R., Thelwall S., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 variant [Internet] Epidemiology. 2021 http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2021.05.22.21257658 mai [cité 30 mai 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keehner J., Horton L.E., Binkin N.J., Laurent L.C., Pride D., Longhurst C.A., et al. Resurgence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a highly vaccinated health system workforce. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1330–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2112981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrews N., Tessier E., Stowe J., Gower C., Kirsebom F., Simmons R., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Vaccine effectiveness and duration of protection of Comirnaty, Vaxzevria and Spikevax against mild and severe COVID-19 in the UK. 09.15.21263583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dagan N., Barda N., Kepten E., Miron O., Perchik S., Katz M.A., et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a Nationwide mass vaccination setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1412–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2101765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chemaitelly H., Yassine H.M., Benslimane F.M., Al Khatib H.A., Tang P., Hasan M.R., et al. mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 variants and severe COVID-19 disease in Qatar. Nat Med. 2021;27:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01446-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chodick G., Tene L., Rotem R.S., Patalon T., Gazit S., Ben-Tov A., et al. The effectiveness of the TWO-DOSE BNT162b2 vaccine: analysis of real-world data. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab438. ciab438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fabiani M., Ramigni M., Gobbetto V., Mateo-Urdiales A., Pezzotti P., Piovesan C. Effectiveness of the Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccine in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers, Treviso province, Veneto region, Italy, 27 December 2020 to 24 March 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26:2100420. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.17.2100420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Angel Y., Spitzer A., Henig O., Saiag E., Sprecher E., Padova H., et al. Association between vaccination with BNT162b2 and incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections among health care workers. JAMA. 2021;325:2457–2465. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pilishvili T., Gierke R., Fleming-Dutra K.E., Farrar J.L., Mohr N.M., Talan D.A., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine among U.S. health care personnel. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2106599. NEJMoa2106599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andrews N., Tessier E., Stowe J., Gower C., Kirsebom F., Simmons R., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Vaccine effectiveness and duration of protection of Comirnaty, Vaxzevria and Spikevax against mild and severe COVID-19 in the UK. 09.15.21263583. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faria E de, Guedes A.R., Oliveira M.S., Moreira MV. de G., Maia F.L., Barboza A. dos S., et al. medRxiv; 2021. Performance of vaccination with CoronaVac in a cohort of healthcare workers (HCW) - preliminary report. 04.12.21255308. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jara A., Undurraga E.A., González C., Paredes F., Fontecilla T., Jara G., et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chile. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:875–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li X.-N., Huang Y., Wang W., Jing Q.-L., Zhang C.-H., Qin P.-Z., et al. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant infection in Guangzhou: a test-negative case–control real-world study. Emerg Microbe. Infect. 2021;10:1751–1759. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1969291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haas E.J., Angulo F.J., McLaughlin J.M., Anis E., Singer S.R., Khan F., et al. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2021. Nationwide vaccination campaign with BNT162b2 in Israel demonstrates high vaccine effectiveness and marked declines in incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths [Internet]https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3811387 mars [cité 17 avr 2021]. Report No.: ID 3811387. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenberg E.S. New COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations among adults, by vaccination status — New York, may 3–July 25, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1150–1155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grannis S.J. Interim estimates of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19–associated emergency department or urgent care clinic encounters and hospitalizations among adults during SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617.2 (delta) variant predominance — nine states, June–August 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1291–1293. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Polinski J.M., Weckstein A.R., Batech M., Kabelac C., Kamath T., Harvey R., et al. Effectiveness of the single-dose Ad26. COV2.S COVID Vaccine medRxiv. 2021 09.10.21263385. [Google Scholar]