Abstract

Bariatric surgery (BS) is an effective treatment for morbid obesity. However, a simple and easy-to-use tool for the prediction of BS unsuccess is still lacking. Baseline and follow-up data from 300 consecutive patients who underwent BS were retrospectively collected. Supervised regression and machine-learning techniques were used for model development, in which BS unsuccess at 2 years was defined as a percentage of excess-weight-loss (%EWL) < 50%. Model performances were also assessed considering the percentage of total-weight-loss (%TWL) as the reference parameter. Two scoring systems (NAG-score and ENAG-score) were developed. NAG-score, comprising only pre-surgical data, was structured on a 4.5-point-scale (2 points for neck circumference ≥ 44 cm, 1.5 for age ≥ 50 years, and 1 for fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL). ENAG-score, including also early post-operative data, was structured on a 7-point-scale (3 points for %EWL at 6 months ≤ 45%, 1.5 for neck circumference ≥ 44 cm, 1 for age ≥ 50 years, and 1.5 for fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL). A 3-class-clustering was proposed for clinical application. In conclusion, our study proposed two scoring systems for pre-surgical and early post-surgical prediction of 2-year BS weight-loss, which may be useful to guide the pre-operative assessment, the appropriate balance of patients’ expectations, and the post-operative care.

Subject terms: Obesity, Obesity

Introduction

Bariatric surgery (BS) is a recognized and effective treatment for patients with morbid obesity, i.e., for those individuals with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m2 or a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities, who are refractory to lifestyle change and drug therapy1. Several surgical techniques are currently available, but the two most commonly performed are sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB)1–4.

Determining the predictors of BS weight outcomes is an area of active debate1,5,6. A reliable prediction of long-term BS results would facilitate the pre-operative assessment, the appropriate balance of patients’ expectations, and the post-operative care1,4. Several baseline characteristics have been associated with poor weight loss, such as increased fasting glucose levels7,8 and increased waist circumference values9. Other predictors, such as sex, age, and psychiatric comorbidities (psychiatric diseases, personality disorders, eating disorders) were associated with weight loss in some studies10,11 but not in others12,13. An interesting focus should be reserved to pre-surgical BMI, as its association with weight loss following BS has variably been reported to be direct10,14, inverse15–17 or absent18–20. Moreover, post-operative weight loss trajectories, usually measured up to 6 months, have been proved to be a useful tool for early prediction of weight outcomes in the longer term21–28. However, post-surgical weight changes are remarkably variable in their trends, with significant differences among individuals29,30; therefore, long-term BS success may still be achieved in patients showing a poor early weight loss, and vice versa21–28.

In clinical practice, it is often difficult to take into account all these factors comprehensively during patient assessment. Furthermore, collinearities between explanatory variables are possible, and factors significantly associated with the outcome at univariate analyses may lose their statistical significance when included in multivariate models. Another important issue in predictive models is to establish the relative strength of each considered variable in terms of outcome prediction; model calibration with proper tuning of predictors’ relative weights is a crucial step for any subsequent practical application.

Several equations for post-operative weight loss prediction have been proposed in recent years21,31–36; however, the retrieved evidence was often limited by a short follow-up time (up to 1 year after BS in most cases)21,31–33,35 or by a relatively small sample size21,33,35. Moreover, post-operative weight loss and model predictors were considered as continuous measures in most cases31–36; this represents a further limitation for a comfortable use of these models in the clinical practice, in which dichotomous evaluations, conclusions, or choices are most often needed.

To the best of our knowledge, a simple and easy-to-use estimation tool for pre-surgical and early post-surgical prediction of long-term BS weight loss is still lacking. The aim of the present study was to propose two scoring systems, the NAG-score and the ENAG-score, respectively for pre-BS and early post-BS prediction of weight loss after a 2-year follow-up.

Methods

Study design and patient management

In this retrospective observational study, we collected data from the clinical records of the first 300 patients who underwent BS at the General Surgery Department of the “Città della Salute e della Scienza” Hospital of Turin, University of Turin, from the 1st January 2016 and met the below-reported criteria.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) age from 18 to 65 years old; (2) BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 with comorbidities or BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2, with numerous unsuccessful attempts to lose weight; (3) a minimum 2-year follow-up at our Obesity Unit. Exclusion criteria were: (1) secondary causes of obesity (e.g., hypothalamic diseases, endocrine diseases); (2) associated comorbidities or diseases impacting on weight loss (for example, patients who performed BS in prevision of transplantation).

Patients gave their informed consent to the processing of their data. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Comitato Etico Interaziendale A.O.U. Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino—A.O. Ordine Mauriziano—A.S.L. Città di Torino) and was in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient management and data collection

Pre-operatively, data relative to eating behaviours, previous attempts of weight loss, and presence of comorbidities were collected28. Weight, height, waist circumference, and neck circumference were assessed in all patients as anthropometric measures. A fasting blood sample was drawn from all patients, and glucose and lipid values were centrally measured.

The surgical approach consisted of either SG or RYGB. The type of surgery was based on the following patient features: BMI, age, gender, body fat distribution, presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, patient’s expectations/realistic goals, long-term treatment for a coexisting disease or condition for which absorption and pharmacokinetics of drugs are of major concern. Follow-up visits at our obesity unit took place at 1, 2, 6, 12, and 24 months after BS. Details about patient management and surgical techniques have been previously described28.

To the scope of model creation, BS success was defined as the percentage of excess-weight-loss (%EWL), which was calculated as:

Weight corresponding to the BMI = 25 kg/m2 was considered as the ideal body weight. An unsuccessful weight loss after BS was defined as %EWL < 50%, according to guidelines1.

The use of %EWL for the evaluation of BS weight-outcome has been recently questioned, mostly due to its dependency on pre-BS weight excess37,38, with the percentage of total-weight-loss (%TWL), calculated as:

being proposed as an alternative parameter37,38. However, there is still no consensus in literature about which threshold to adopt for the definition of BS unsuccess, since %TWL < 20% was proposed by some authors37–39, while %TWL < 25% was suggested by others40. Therefore, to the scope of this study, we opted to use %EWL as the reference parameter for model development, due to the availability of an unanimously recognized cut-off for the definition of BS unsuccess; nevertheless, in order to further strengthen the consistency of our results, final model performances were also assessed considering %TWL as the outcome of choice.

Measurements

Weight was measured with the patient wearing light clothes and no shoes to the nearest 0.1 kg by a digital scale with a capacity of 300 kg (Wunder Sa.Bi.srl). Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm with a Stadiometer SECA 220 measuring rod (Hamburg, Germany). Waist and neck circumferences were assessed by a plastic tape meter at the umbilicus level and under the cricoid cartilage, respectively. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension were diagnosed in accordance with international guidelines. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was hypothesized in the presence of excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and choking or gasping during sleep, enlarged neck circumference, and an intermediate to high-risk score at the STOP-Bang questionnaire41. The diagnosis was confirmed by a sleep-expert neurologist by means of further exams, according to international guidelines42,43.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were summarized using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percent values for categorical data.

Relevant predictors of BS outcomes were found through univariate and multivariate logistic regressions, using a stepwise backward selection. Optimal cut-points for continuous variables were found through a supervised machine-learning algorithmic approach; cut-offs for class distinction were automatedly derived by Class-Attribute Contingency Coefficient (CACC) discretization algorithm as those maximizing separation between classes44. Multivariate logistic regression was re-applied on discretized variables; integer and half-integer point scores were assigned upon normalization and rounding of regression beta-coefficients. Model calibration was evaluated by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. A ten-fold cross-validation algorithm was adopted for internal validation, in order to provide an estimate of model performance on unseen data45,46: after a random split of the original sample into ten groups, the modelling process was repeated starting from stepwise variable selection in nine of them, and its performance was evaluated in the tenth; the process was then repeated ten times, rotating the validation group at each round; final model performance was obtained as the average performance over the ten iterations46. According to the TRIPOD statement46, this internal validation approach was preferred to the more classical sample-split approach due to its better reliability in reducing the bias and the variability of performance estimates. Iterative Dichotomiser 3 (ID3) algorithm47,48 was applied to cluster risk classes of clinical relevance.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 17 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For the supervised machine-learning approach used for score creation, ‘arulesCBA’, ‘partykit’ and ‘rpart’ packages were used.

Results

Univariate analysis and variable discretization

The study comprised 32 males (10.7%) and 268 females (89.3%). The mean age at the moment of BS was 44.6 ± 10.3 years. Two hundred and thirty-three patients (77.7%) underwent SG, while the remaining 67 (22.3%) underwent RYGB.

At 24 months, 56 patients (18.7%) showed a %EWL < 50%, while 46 (15.3%) showed a %TWL < 20%. The association between relevant predictors and %EWL < 50%, which was adopted as the reference parameter for model development, was first explored through univariate logistic regression analysis. Neck circumference, age, frequency of OSA, and frequency of male sex were higher, while %EWL at 6-months lower, in patients with %EWL < 50% at 24 months (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of pre-surgical and early post-surgical data with BS failure (defined as %EWL < 50% at 2 years), analyzed through univariate logistic regressions.

| Variable | Successful weight loss (n = 244) | Unsuccessful weight loss (n = 56) | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.4 ± 10.1 | 49.9 ± 9.7 | 1.07 | 1.04–1.11 | < 0.001 |

| Age category (%) § | |||||

| < 50 years | 71.7 | 41.1 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 50 years | 28.3 | 58.9 | 3.64 | 2.00–6.64 | < 0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 8.2 | 21.4 | 3.05 | 1.56–5.86 | 0.005 |

| Smoking habits (%) | |||||

| Current smoker | 57.4 | 55.4 | 1.00 | ||

| Past smoker | 20.1 | 21.4 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 0.79 |

| Never smoker | 22.5 | 23.2 | 1.01 | 0.91–1.13 | 0.86 |

| Job (%) | |||||

| Unemployed/housewife/retired | 38.1 | 39.3 | 1.00 | ||

| Employee | 40.6 | 39.3 | 0.99 | 0.90–1.09 | 0.85 |

| Manual worker | 19.7 | 16.1 | 0.97 | 0.85–1.09 | 0.59 |

| Other | 1.6 | 5.4 | 1.27 | 0.94–1.71 | 0.12 |

| Type of surgery (%) | |||||

| Gastric bypass | 22.1 | 23.2 | 1.00 | ||

| Sleeve gastrectomy | 77.9 | 76.8 | 0.94 | 0.54–1.71 | 0.86 |

| Pre-surgical weight (kg) | 118.3 ± 22.4 | 117.8 ± 25.4 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.89 |

| Height (cm) | 162.9 ± 8.7 | 163.9 ± 9.5 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.44 |

| Pre-surgical BMI (kg/m2) | 44.6 ± 8.1 | 43.6 ± 7.7 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.41 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 123.0 ± 14.6 | 125.3 ± 18.6 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.33 |

| Waist circumference category (%) § | |||||

| < 142 cm | 90.6 | 80.4 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 142 cm | 9.4 | 19.6 | 2.35 | 1.07–5.16 | 0.033 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 38.5 ± 3.3 | 40.4 ± 4.4 | 1.15 | 1.07–1-23 | < 0.001 |

| Neck circumference category (%) § | |||||

| < 44 cm | 93.4 | 73.2 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 44 cm | 6.6 | 26.8 | 5.21 | 2.39–11.36 | < 0.001 |

| OSA (%) | 18.9 | 33.9 | 2.21 | 1.28–3.76 | 0.015 |

| Arterial hypertension (%) | 34.4 | 35.7 | 1.06 | 0.63–1.75 | 0.85 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 106.7 ± 28.8 | 112.2 ± 31.2 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.20 |

| Fasting glucose category § | |||||

| < 118 mg/dL | 84.4 | 67.9 | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 118 mg/dL | 15.6 | 32.1 | 2.57 | 1.33–4.96 | 0.005 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (%) | 22.1 | 25.0 | 1.17 | 0.65–2.04 | 0.64 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 198.3 ± 37.7 | 188.3 ± 37.4 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.00 | 0.07 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 47.4 ± 13.1 | 46.5 ± 12.3 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.63 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 146.4 ± 65.8 | 145.9 ± 50.3 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.96 |

| %EWL at 6 months | 59.9 ± 25.9 | 32.5 ± 48.2 | 0.94 | 0.93–0.96 | < 0.001 |

| Category of %EWL at 6 months (%) § | |||||

| %EWL > 45% | 78.7 | 23.2 | 1.00 | ||

| %EWL ≤ 45% | 21.3 | 76.8 | 12.21 | 6.11–24.40 | < 0.001 |

§Cut-off derived through CACC discretization algorithm.

BMI body mass index, BS bariatric surgery, CACC Class-Attribute Contingency Coefficient, CI confidence interval, EWL excess weight loss, HDL high-density lipoprotein, OR odds-ratio, OSA obstructive sleep apnea.

For continuous variables, the possible presence of significant threshold values was explored through the application of CACC discretization algorithm; if present, meaningful cut-offs for class distinction were automatedly derived as those maximizing separation between classes. Not surprisingly, a meaningful categorization could be found for neck circumference, age, and %EWL at 6 months, i.e., those variables who were already significant when considered as continuous. The optimal cut-points retrieved were ≥ 44 cm for neck circumference (OR = 5.21, 95% CI 2.39–11.36), ≥ 50 years for age (OR = 3.64, 95% CI 2.00–6.64), and ≤ 45% for %EWL at 6 months (OR = 12.21, 95% CI 6.11–24.40). Moreover, a significant dichotomization emerged for two other predictors, i.e., fasting glucose and waist circumference. The optimal cut-points retrieved were ≥ 118 mg/dL for fasting glucose (OR = 2.57, 95% CI 1.33–4.96) and ≥ 142 cm for waist circumference (OR = 2.35, 95% CI 1.07–5.16) (Table 1). The clinical significance of the algorithmically retrieved threshold values was qualitatively substantiated by descriptive analyses, in which the non-linear dependence between the predictors and the outcome was readily evident (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Development and internal validation of pre-surgical score

All pre-surgical variables showing a significant correlation with the outcome at univariate analysis were included in a multivariate regression model. Given the intention of developing a predictive score, continuous variables were included in the model according to their retrieved dichotomizations. After a stepwise backward selection, the variables retaining statistical significance were neck circumference ≥ 44 cm (OR = 4.21, 95% CI 1.85–9.55), age ≥ 50 years (OR = 3.03, 95% CI 1.62–5.67), and fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL (OR = 2.06, 95% CI 1.01–4.18) (Table 2). All other variables (i.e., male sex, OSA, waist circumference ≥ 142 cm) were excluded as non-significant at multivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Prediction of BS failure, defined as %EWL < 50% at 2 years, by multivariate logistic regression after stepwise backward selection of pre-surgical data; NAG-score point assignment according to multivariate regression coefficients.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | β-coefficient | Normalized coefficient | Points for NAG-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck circumference ≥ 44 cm | 4.21 | 1.85–9.55 | 0.001 | + 1.437 | 1.990 | + 2 |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 3.03 | 1.62–5.67 | 0.001 | + 1.109 | 1.536 | + 1.5 |

| Fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL | 2.06 | 1.01–4.18 | 0.046 | + 0.722 | 1.000 | + 1 |

BS bariatric surgery, CI confidence interval, EWL excess weight loss, OR odds-ratio.

This model showed a moderate accuracy in the prediction of the outcome (AUC = 0.713). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test did not reveal any significant miscalibration (p = 0.58). Internal validation of the model was performed through ten-fold cross-validation; the final estimation of the model performance on unseen data, obtained as the average AUC over the ten iterations, was equal to 0.695, thus reassuring about a substantially null overfitting effect.

In order to simplify its clinical application, the three variables selected by the model were used to develop a discrete-point prediction score; integer and half-integer point scores were assigned upon normalization and rounding of regression beta-coefficients (Table 2). Due to the considered variable, this score was named “NAG-score” (Neck circumference, Age, Glucose), and was defined by the sum of all three components, on a 4.5-point-scale. Notably, this mild simplification did not lead to a significant reduction in the predictive power of the model since the AUC remained equal to 0.713.

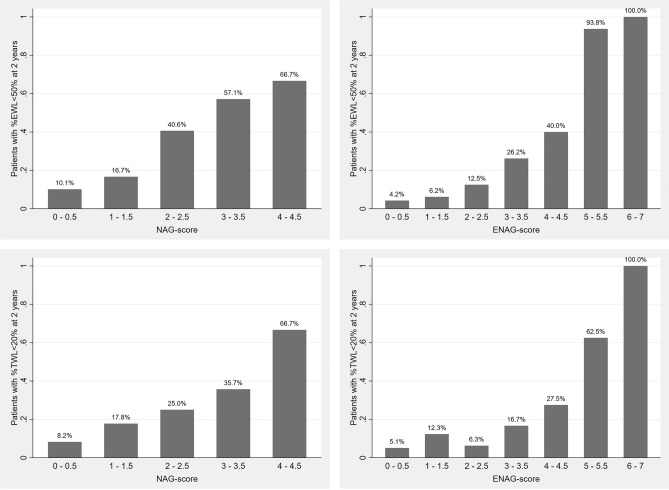

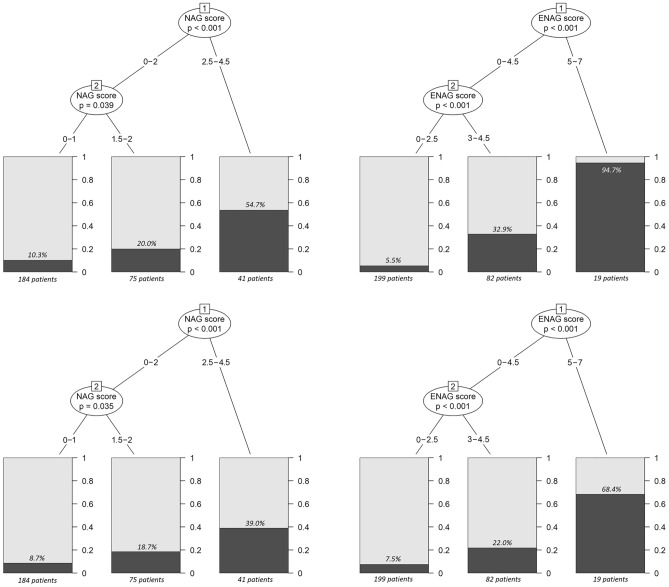

A descriptive graph of the risk of unsuccessful weight loss after BS according to NAG-score is presented in Fig. 1; the performance of the model in predicting BS unsuccess was evaluated both in terms of %EWL and %TWL, with similar results. In addition, in order to simplify the interpretation of NAG-score and to identify the most clinically relevant risk classes, an algorithmic classification clustering was proposed. ID3 algorithm clustered the patients in three distinct risk classes (0–1 points, 1.5–2 points, 2.5–4.5 points), with no differences whether considering %EWL < 50% or %TWL < 20% as the reference outcome (Fig. 2); given their clinical correlates, we referred to them as “low-risk”, “intermediate-risk”, and “high-risk” classes, respectively. As reported in Table 3, when considering %EWL, the low-risk class comprised 184 patients, with a 10.3% risk of unsuccessful weight loss at 2-years from BS. The intermediate-risk class comprised 75 patients, with a 20.0% risk of unsuccessful post-surgical weight loss. The high-risk class comprised 41 patients, with a 54.7% risk of unsuccessful post-surgical weight loss. The stratification performance of the model across different risk classes was overall preserved when adopting %TWL as the reference parameter; in this case, the risk of BS unsuccess was equal to 8.7%, 18.7%, and 39.0% in the low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk class, respectively.

Figure 1.

Descriptive graphs of BS unsuccess risk, defined either as %EWL < 50% (upper row) or %TWL < 20% (lower row) at 2 years, according to NAG-score (left column) and ENAG-score (right column). BS bariatric surgery, EWL excess weight loss, TWL total weight loss.

Figure 2.

Stratification of BS unsuccess risk, defined either as %EWL < 50% (upper row) or %TWL < 20% (lower row) at 2 years, based on NAG-score (left column) and ENAG-score (right column). Relevant cut-offs for class distinction and patients’ clustering were automatedly retrieved though ID3 algorithm. BS bariatric surgery, EWL excess weight loss, ID3 Iterative Dichotomiser 3, TWL total weight loss.

Table 3.

Pre-surgical estimation of unsuccessful weight loss at 2-years from BS according to NAG-score risk classes.

| Risk class as identified by ID3 algorithm | NAG-score | N° of patients | 2-year BS unsuccess risk (defined as %EWL < 50%) |

2-year BS unsuccess risk (defined as %TWL < 20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | 0–1 | 184 | 10.3% | 8.7% |

| Intermediate risk | 1.5–2 | 75 | 20.0% | 18.7% |

| High risk | 2.5–4.5 | 41 | 54.7% | 39.0% |

BS bariatric surgery, EWL excess weight loss, ID3 Iterative Dichotomiser 3, TWL total weight loss.

Development and internal validation of early post-surgical score

In order to develop an early post-surgical predictive score, %EWL at 6 months was added to pre-surgical variables in a further multivariate regression model. Again, given the intention of developing a predictive score, continuous variables were included in the model according to their retrieved dichotomizations. After a stepwise backward selection, the variables retaining statistical significance were %EWL at 6 months ≤ 45% (OR = 13.34, 95%CI 6.14–28.98), neck circumference ≥ 44 cm (OR = 3.81, 95% CI 1.52–9.57), age ≥ 50 years (OR = 2.40, 95% CI 1.18–4.88), and fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL (OR = 3.40, 95% CI 1.43–8.07) (Table 4). All other variables (i.e., male sex, OSA, waist circumference ≥ 142 cm) were excluded as non-significant at multivariate analysis.

Table 4.

Prediction of BS failure, defined as %EWL < 50% at 2 years, by multivariate logistic regression after stepwise backward selection of pre-surgical and early post-surgical data; ENAG-score point assignment according to multivariate regression coefficients.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value | β-coefficient | Normalized coefficient | Points for ENAG-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neck circumference ≥ 44 cm | 3.81 | 1.52–9.57 | 0.004 | + 1.338 | 1.531 | + 1.5 |

| Age ≥ 50 years | 2.40 | 1.18–4.88 | 0.016 | + 0.874 | 1.000 | + 1 |

| Fasting glucose ≥ 118 mg/dL | 3.40 | 1.43–8.07 | 0.006 | + 1.223 | 1.399 | + 1.5 |

| EWL at 6 months ≤ 45% | 13.34 | 6.14–28.98 | < 0.001 | + 2.591 | 2.965 | + 3 |

BS bariatric surgery, CI confidence interval, EWL excess weight loss, OR odds-ratio.

A significant increase in model accuracy could be noted (AUC = 0.846). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test did not reveal any significant miscalibration (p = 0.68). Internal validation of the model was performed through ten-fold cross-validation; the final estimation of the model performance on unseen data, obtained as the average AUC over the ten iterations, was equal to 0.817, thus reassuring about a modest overfitting effect.

The four variables selected by the model were used to develop a discrete-point prediction score (Table 4), which was named “ENAG-score” (Early loss, Neck circumference, Age, Glucose), and was defined by the sum of all four components, on a 7-point-scale. This mild simplification did not lead to a significant reduction in the predictive power of the model, since the AUC only slightly declined from 0.846 to 0.845.

A descriptive graph of the risk of unsuccessful weight loss after BS according to ENAG-score is presented in Fig. 1; the performance of the model in predicting BS unsuccess was evaluated both in terms of %EWL and %TWL, with similar results. ID3 algorithm clustered the observations in three distinct and clinically relevant risk classes (0–2.5 points, 3–4.5 points, 5–7 points), with no differences whether considering %EWL < 50% or %TWL < 20% as the reference outcome (Fig. 2); given their clinical correlates, these classes were labelled again as “low-risk”, “intermediate-risk”, and “high-risk”, respectively. As reported in Table 5, when considering %EWL, the low-risk class comprised 199 patients, with a 5.5% risk of unsuccessful weight loss at 2-years from BS. The intermediate-risk class comprised 82 patients, with a 32.9% risk of unsuccessful post-surgical weight loss. The high-risk class comprised 19 patients, with a 94.7% risk of unsuccessful post-surgical weight loss. The stratification performance of the model across different risk classes was overall preserved when adopting %TWL as the reference parameter; in this case, the risk of BS unsuccess was equal to 7.5%, 22.0%, and 68.4% in the low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk class, respectively.

Table 5.

Early post-surgical estimation of unsuccessful weight loss at 2-years from BS according to ENAG-score risk classes.

| Risk class as identified by ID3 algorithm | ENAG-score | N° of patients | 2-year BS unsuccess risk (defined as %EWL < 50%) |

2-year BS unsuccess risk (defined as %TWL < 20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | 0–2.5 | 199 | 5.5% | 7.5% |

| Intermediate risk | 3–4.5 | 82 | 32.9% | 22.0% |

| High risk | 5–7 | 19 | 94.7% | 68.4% |

BS bariatric surgery, EWL excess weight loss, ID3 Iterative Dichotomiser 3, TWL total weight loss.

Discussion

Two multivariate models for pre-surgical and for early post-surgical prediction of BS weight loss after a 2-year follow-up were developed and internally validated. To facilitate their clinical use, two simplified scoring systems (NAG-score and ENAG-score) were derived by assigning integer or half-integer points to each of the included predictors.

The first model, based only on pre-surgical data, showed a moderate overall accuracy for the prediction of the outcome of interest, with an AUC of 0.713. The retrieved score, i.e., the NAG-score, can be a simple and useful tool to stratify different pre-surgical risks for BS failure and may be helpful, during pre-operative assessment, for an appropriate balance of patient’s expectations and for a personalization of the intensity of the follow-up. In particular, a higher-intensity follow-up might be considered in patients with intermediate-to-high risk of unsuccessful post-surgical weight-loss, since, possibly, these patients are those who may benefit the most from a closer dietary and medical counselling1,4,49,50.

The second model, which included also early post-operative weight-loss data at 6 months, showed good overall accuracy for the prediction of the outcome of interest, with an AUC of 0.846. The retrieved score, i.e., the ENAG-score, can be of value for early prediction of long-term outcomes of the surgical procedure. This can be useful as a further guide for the refinement of the follow-up continuation and for the personalization of the therapeutic approach; in particular, it may be helpful as a guide for the avoidance of therapeutic inertia in patients with an intermediate-to-high probability of unsuccessful post-surgical weight loss. In fact, these patients are those who may benefit the most from stricter counselling and more intensive lifestyle management, and that may be potential candidates for an early start of adjunctive pharmacological treatments1,4,49,50.

It is interesting to note that the algorithm of stepwise backward selection led to the inclusion of exactly the same set of pre-surgical factors in both models; in particular, the parameters that were retained as statistically significant were larger neck circumference (≥ 44 cm), older age (≥ 50 years), and higher fasting glucose levels (≥ 118 mg/dL). These results were coherent with previous findings by other authors7,8,10,11,28. Even more interestingly, their predictive capacity remained significant after adding to the model a very robust parameter such as early post-operative weight loss; this further supported their relevance as independent predictors of BS outcomes in the longer term. On the other hand, male sex, OSA, and larger waist circumference (≥ 142 cm), though significant at univariate analysis, lost their significance in the multivariate model. This is not surprising, and it is likely a consequence of the multiple collinearities between these variables and those retained in the scores. Nevertheless, the fact that neck circumference performed better than waist circumference in the prediction of BS outcomes is noteworthy. Neck circumference, indeed, relates to oropharyngeal fat infiltration, which narrows the upper respiratory tract and is a more stable index because it is not affected by eating or body position or respiratory rates as the waist circumference measurement does51. Furthermore, the neck fat depot has been reported to be strongly associated with cardiometabolic and atherosclerotic diseases independent of visceral and whole-body obesity51–55. Ectopic fat deposition is dysfunctional and associated with chronic sub-clinic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, and upper-body subcutaneous fat delivers more free acids than visceral fat in the systemic circulation, thus contributing to increased insulin resistance and other dysmetabolic disorders53,55,56. In particular, neck circumference appears to be a unique pathologic fat depot with a unique genetic basis, independent of BMI57. Finally, increased neck circumference is also a risk factor for OSA, which, in turn, is associated with increased cardiometabolic risk53.

The main strength of our study was the simplicity of the proposed scoring systems, which was achieved upon the categorization of predictive variables through a robust supervised algorithmic approach. Moreover, the internal validation of our model, together with the assessment of its good calibration, conferred higher consistency to the obtained results, which were further strengthened by the reproducibility of risk-class stratification over two different BS-success defining parameters (%EWL and %TWL).

Our study had also some limitations. First, its retrospective design limited the possibility to take into account some other potential predictors, such as psychosocial data and physical activity levels; their inclusion might have led to a more complete and better-performing scoring system and could have allowed the assessment of causal effects through Mendelian randomization analysis procedures based on genomic background and environmental exposure data58–62, which might be the subject for future research. Second, stronger evidence would have been achieved by considering a longer follow-up time; however, the time-point which has been examined (i.e., 2 years after BS) was longer than in other studies proposing equations or scoring systems for the prediction of BS outcomes21,31–36, and was considered as a time-point of weight stabilization in most patients29,30,63,64. Third, the sample size was not sufficient to develop different scoring systems for SG and RYGB; however, the type of intervention was taken into account during model development, and no significant differences emerged between the two procedures in terms of outcomes. Fourth, our study comprised only Caucasian patients; as there is extensive evidence of weight loss variability among ethnical groups65–68, the generalizability of our data to other populations is uncertain.

In conclusion, our study proposed two simple scoring systems (the NAG-score and the ENAG-score) for pre-surgical and early post-surgical prediction of 2-year BS weight loss. The presented data supported their consistency as easy-to-use estimation tools. Further studies are needed to confirm their external validity on different patient cohorts; if so, their application in clinical practice might provide a simple and objective instrument for the evaluation of BS failure risk, which may be useful to guide pre-operative patient’s assessment, to appropriately balance patient’s expectations, and to manage more effectively the post-operative care.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

F.B. conceptualized the work, performed the data analysis and contributed to the manuscript writing. M.P., C.D.E., S.Bos. and F.R. contributed to the data collection and manuscript revision. S.A., M.T. and M.M. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript writing. A.D.F. and E.G. supervised the manuscript drafting. S.B. contributed to work conceptualization, data analysis, manuscript writing and final draft supervision. All authors approved the manuscript in its final form.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-00475-4.

References

- 1.Fried M, et al. Interdisciplinary European guidelines on metabolic and bariatric surgery. Obes. Facts. 2013;6:449–468. doi: 10.1159/000355480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pucci A, Batterham RL. Mechanisms underlying the weight loss effects of RYGB and SG: Similar, yet different. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2019;42:117–128. doi: 10.1007/s40618-018-0892-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osland E, Yunus RM, Khan S, Memon B, Memon MA. Weight loss outcomes in Laparoscopic Vertical Sleeve Gastrectomy (LVSG) versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (LRYGB) procedures: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2017;27:8–18. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Lorenzo N, et al. Clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) on bariatric surgery: Update 2020 endorsed by IFSO-EC EASO and ESPCOP. Surg. Endosc. 2020;34:2332–2358. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-07555-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karpińska IA, et al. Is it possible to predict weight loss after bariatric surgery?—external validation of predictive models. Obes. Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05341-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Khyatt W, Ryall R, Leeder P, Ahmed J, Awad S. Predictors of inadequate weight loss after laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes. Surg. 2017;27:1446–1452. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2500-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sans A, et al. Baseline anthropometric and metabolic parameters correlate with weight loss in women 1-year after laparoscopic Roux-En-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2017;27:2940–2949. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2720-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faria G, et al. Fasting glycemia: A good predictor of weight loss after RYGB. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2014;10:419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barhouch AS, et al. Predictors of excess weight loss in obese patients after gastric bypass: A 60-month follow-up. Obes. Surg. 2016;26:1178–1185. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masrur M, et al. Factors associated with weight loss after metabolic surgery in a multiethnic sample of 1012 patients. Obes. Surg. 2020;30:975–981. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04338-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Hunger control and regular physical activity facilitate weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes. Surg. 2008;18:833–840. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ansar H, Zamaninour N, Pazouki A, Kabir A. Weight loss after one anastomosis gastric bypass-mini gastric bypass (OAGB-MGB): Patient-related perioperative predictive factors. Obes. Surg. 2020;30:1316–1323. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04270-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black DW, Goldstein RB, Mason EE. Psychiatric diagnosis and weight loss following gastric surgery for obesity. Obes. Surg. 2003;13:746–751. doi: 10.1381/096089203322509327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alvarado R, et al. The impact of preoperative weight loss in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2005;15:1282–1286. doi: 10.1381/096089205774512429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diab A, Rahman F, Abdurasul EM, Diab FH. The effect of age, gender, and baseline BMI on weight loss outcomes in obese patients undergoing intragastric balloon therapy. Obes. Surg. 2019;29:3542–3546. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen EY, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of 1-year outcome in gastric bypass surgery. Obes. Surg. 2009;19:1240–1242. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9724-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riess KP, Baker MT, Lambert PJ, Mathiason MA, Kothari SN. Effect of preoperative weight loss on laparoscopic gastric bypass outcomes. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2008;4:704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlin AM, O’Connor EA, Genaw JA, Kawar S. Preoperative weight loss is not a predictor of postoperative weight loss after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2008;4:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarela AI, Dexter SPL, O’Kane M, Menon A, McMahon MJ. Long-term follow-up after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: 8–9-year results. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2012;8:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krimpuri RD, et al. Qualifying for bariatric surgery: Is preoperative weight loss a reliable predictor of postoperative weight loss? Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2018;14:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen CY, et al. Check point to get adequate weight loss within 6-months after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity in Asian population. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:2. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55492-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hindle A, de la Piedad Garcia X, Brennan L. Early post-operative psychosocial and weight predictors of later outcome in bariatric surgery: A systematic literature review. Obes. Rev. 2017;18:317–334. doi: 10.1111/obr.12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mor A, Sharp L, Portenier D, Sudan R, Torquati A. Weight loss at first postoperative visit predicts long-term outcome of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using Duke weight loss surgery chart. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2012;8:556–560. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puzziferri N, et al. Variations of weight loss following gastric bypass and gastric band. Ann. Surg. 2008;248:233–242. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181820cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritz P, et al. Early prediction of failure to lose weight after obesity surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2013;9:118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Obeidat F, Shanti H. Early weight loss as a predictor of 2-year weight loss and resolution of comorbidities after sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2016;26:1173–1177. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1903-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vuolo G, et al. Is sleeve gastrectomy a therapeutic procedure for all obese patients? Int. J. Surg. 2016;30:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Eusebio C, et al. What predicts the unsuccess of bariatric surgery? An observational retrospective study. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01398-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maciejewski ML, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1046–1055. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kindel T, Lomelin D, McBride C, Kothari V, Thompson J. The time to weight-loss steady state after gastric bypass predicts weight-loss success. Obes. Surg. 2016;26:327–331. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1754-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cottam S, et al. The use of predictive markers for the development of a model to predict weight loss following vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2018;28:3769–3774. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wise ES, Hocking KM, Kavic SM. Prediction of excess weight loss after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Data from an artificial neural network. Surg. Endosc. 2016;30:480–488. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4225-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goulart A, et al. Doctor, how much weight will i lose?—a new individualized predictive model for weight loss. Obes. Surg. 2016;26:1357–1359. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seyssel K, et al. A predictive model of weight loss after roux-en-y gastric bypass up to 5 years after surgery: A useful tool to select and manage candidates to bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018;28:3393–3399. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janik MR, et al. Setting realistic expectations for weight loss after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Wideochirurgia I Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne. 2019;14:415–419. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2019.81661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Velázquez-Fernández D, et al. Development of an interactive outcome estimation tool for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in mexico based on a cohort of 1002 patients. Obes. Surg. 2019;29:2878–2885. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03929-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grover BT, et al. Defining weight loss after bariatric surgery: A call for standardization. Obes. Surg. 2019;29:3493–3499. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Rijswijk AS, van Olst N, Schats W, van der Peet DL, van de Laar AW. What is weight loss after bariatric surgery expressed in percentage total weight loss (%TWL)? A systematic review. Obes. Surg. 2021;31:3833–3847. doi: 10.1007/s11695-021-05394-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brissman M, Beamish AJ, Olbers T, Marcus C. Prevalence of insufficient weight loss 5 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Metabolic consequences and prediction estimates: A prospective registry study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tu Y, et al. A total weight loss of 25% shows better predictivity in evaluating the efficiency of bariatric surgery. Int. J. Obes. 2021;45:396–403. doi: 10.1038/s41366-020-00690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung F, Yang Y, Liao P. Predictive performance of the stop-bang score for identifying obstructive sleep apnea in obese patients. Obes. Surg. 2013;23:2050–2057. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qaseem A, et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adults: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014;161:210–220. doi: 10.7326/M12-3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapur VK, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: An American academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017;13:479–504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai C-J, Lee C-I, Yang W-P. A discretization algorithm based on class-attribute contingency coefficient. Inf. Sci. (Ny) 2008;178:714–731. doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2007.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steyerberg EW, et al. Internal validation of predictive models: Efficiency of some procedures for logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54:774–781. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moons KGM, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015;162:W1–W73. doi: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinlan JR. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986;1:81–106. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogheneovo EE, Nlerum PA. Iterative dichotomizer 3 (ID3) decision tree: A machine learning algorithm for data classification and predictive analysis. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020;7:514–521. doi: 10.22161/ijaers.74.60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rudolph A, Hilbert A. Post-operative behavioural management in bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2013;14:292–302. doi: 10.1111/obr.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart F, Avenell A. Behavioural interventions for severe obesity before and/or after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2016;26:1203–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1873-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Namazi N, Larijani B, Surkan P, Azadbakht L. The association of neck circumference with risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018;28:657–674. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aoi S, et al. Association of changes in neck circumference with cardiometabolic risk in postmenopausal healthy women. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2016;23:728–736. doi: 10.5551/jat.31963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silva A, et al. Neck circumference and 10-year cardiovascular risk at the baseline of the ELSA-Brasil study: Difference by sex. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2020;115:840–848. doi: 10.36660/abc.20190289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shokri-Mashhadi N, Moradi S, Mohammadi H, Ghavami A, Rouhani M. Association between neck circumference and lipid profile: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2021 doi: 10.1093/EURJCN/ZVAA018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shi J, et al. Neck circumference as an independent predictor for NAFLD among postmenopausal women with normal body mass index. Nutr. Metab. 2021;18:2. doi: 10.1186/s12986-021-00562-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nielsen S, Guo Z, Johnson C, Hensrud D, Jensen M. Splanchnic lipolysis in human obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1582–1588. doi: 10.1172/JCI21047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, et al. Genome-wide association study of neck circumference identifies sex-specific loci independent of generalized adiposity. Int. J. Obes. 2021;45:1532–1541. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-00817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang X, et al. Genetic support of a causal relationship between iron status and type 2 diabetes: A Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021 doi: 10.1210/CLINEM/DGAB454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang F, et al. Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Hum. Genet. 2021;140:1267–1281. doi: 10.1007/s00439-021-02288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang F, et al. Genetic evidence suggests posttraumatic stress disorder as a subtype of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Invest. 2021 doi: 10.1172/JCI145942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hou L, et al. Exploring the causal pathway from ischemic stroke to atrial fibrillation: a network Mendelian randomization study. Mol. Med. 2020;26:2. doi: 10.1186/s10020-019-0133-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu Y, et al. Multi-trait analysis for genome-wide association study of five psychiatric disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 2020;10:2. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0681-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buchwald H, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004;292:1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ballantyne GH. Measuring outcomes following bariatric surgery: Weight loss parameters, improvement in co-morbid conditions, change in quality of life and patient satisfaction. Obes. Surg. 2003;13:954–964. doi: 10.1381/096089203322618867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Anderson WA, Greene GW, Forse RA, Apovian CM, Istfan NW. Weight loss and health outcomes in African Americans and whites after gastric bypass surgery. Obesity. 2007;15:1455–1463. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harvin G, Delegge M, Garrow DA. The impact of race on weight loss after roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obes. Surg. 2008;18:39–42. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buffington CK, Marema RT. Ethnic differences in obesity and surgical weight loss between African-American and Caucasian females. Obes. Surg. 2006;16:159–165. doi: 10.1381/096089206775565258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guajardo-Salinas GE, Hilmy A, Martinez-Ugarte ML. Predictors of weight loss and effectiveness of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the morbidly obese Hispano-American population. Obes. Surg. 2008;18:1369–1375. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.