Abstract

The COPII component SEC24 mediates the recruitment of transmembrane cargos or cargo adaptors into newly forming COPII vesicles on the ER membrane. Mammalian genomes encode four Sec24 paralogs (Sec24a-d), with two subfamilies based on sequence homology (SEC24A/B and C/D), though little is known about their comparative functions and cargo-specificities. Complete deficiency for Sec24d results in very early embryonic lethality in mice (before the 8 cell stage), with later embryonic lethality (E7.5) observed in Sec24c null mice. To test the potential overlap in function between SEC24C/D, we employed dual recombinase mediated cassette exchange to generate a Sec24cc-d allele, in which the C-terminal 90% of SEC24C has been replaced by SEC24D coding sequence. In contrast to the embryonic lethality at E7.5 of SEC24C-deficiency, Sec24cc-d/c-d pups survive to term, though dying shortly after birth. Sec24cc-d/c-d pups are smaller in size, but exhibit no other obvious developmental abnormality by pathologic evaluation. These results suggest that tissue-specific and/or stage-specific expression of the Sec24c/d genes rather than differences in cargo export function explain the early embryonic requirements for SEC24C and SEC24D.

Subject terms: Coat complexes, Endoplasmic reticulum

Introduction

In eukaryotes, most proteins destined for export out of the cell, to various intracellular storage compartments, or to the cell surface, must traverse the secretory pathway before reaching their final intracellular or extracellular destinations1,2. The first step of this fundamental process is the concentration and packaging of newly synthesized proteins into vesicles on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) at specific ER exit sites3. At these sites, cytosolic components assemble to form the coat protein complex II (COPII)4,5, a protein coat that generates membrane curvature and promotes the recruitment of cargo proteins into a nascent COPII bud6,7. Central to this process is SEC24, the COPII protein component primarily responsible for interaction between transmembrane cargoes (or cargo-bound receptors) and the coat8. SEC24 forms a complex with SEC23 in the cytosol, and the SEC23/SEC24 heterodimer is drawn to ER exit sites upon activation of the GTPase SAR19 by its cognate ER membrane bound guanine exchange factor, SEC1210. Once recruited to the ER membrane, SEC24 interacts with ER exit signals on the cytoplasmic tail of protein cargoes via cargo recognition sites and facilitates vesicle formation.

Mammalian genomes encode four SEC24 paralogs (Sec24a-d), with each containing several highly conserved C-terminal domains and a hypervariable N-terminal segment comprising approximately one-third of the protein sequence. Based on sequence identity, the four mammalian SEC24s can be further sub-divided into two subgroups, SEC24A/B and SEC24C/D11. Murine SEC24A and SEC24B share 58% amino acid identity and murine SEC24C and SEC24D share 60% identity, with only 25% amino acid sequence identity between the two subgroups12, suggesting both ancient and more recent gene duplications. Mice with deficiency in the individual SEC24 paralogs exhibit a wide range of phenotypes. SEC24A-deficient mice present with markedly reduced plasma cholesterol as a result of impaired secretion of PCSK9, a regulatory protein that mediates LDL receptor degradation13. SEC24B-deficient mice exhibit late embryonic lethality at ~ E18.5 due to neural tube closure defects resulting from reduced trafficking of the planar-cell-polarity protein VANGL214. Loss of SEC24C in the mouse results in embryonic lethality at ~ E7.512, with E7.5 Sec24c null embryos exhibiting abnormal gastrulation and thinning of the embryonic ectoderm, suggesting that SEC24C is required in the embryonic ectoderm just prior to gastrulation12. In contrast, SEC24D deficiency in mice results in embryonic death at or before the 8-cell stage15. Abnormalities in SEC24C function have not been described in humans, whereas bi-allelic point mutations in human SEC24D (the truncating mutation p.Gln205*, p.Ser1015Phe located in a cargo-binding pocket, and p.Gln978Pro located in the gelsolin-like domain) have been reported in patients with a developmental skeletal disorder16.

The expansion of the number of COPII paralogs over evolutionary time suggests a divergence in cargo recognition function, with the disparate deficient mouse phenotypes resulting from paralog-specific protein interactions with a subset of cargo molecules, or other functions beyond cargo recognition. Consistent with this model, all four mammalian Sec24s are broadly and ubiquitously expressed in all tissues examined15,17,18. Nonetheless, subtle differences in the developmental timing and/or tissue-specific patterns of expression as the explanation for the unique phenotypes associated with deficiency for each SEC24 paralog cannot be excluded.

The SEC24C and SEC24D proteins appear to have similar structural domains. To test if the duplicated SEC24C/D genes are fixed in the genome because one of the genes acquired a new function (neofunctionalization) or if the copies of the duplicated gene split the function of the ancestral gene (subfunctionalization) in vivo, we employed dual recombinase mediated cassette exchange (dRMCE)19 to knock-in the C-terminal 90% of the coding sequence for SEC24D in place of the corresponding SEC24C coding sequence, at the Sec24c locus. Surprisingly, these SEC24D sequences can largely substitute for SEC24C during embryonic development, rescuing the early embryonic lethality previously observed in SEC24C-deficient mice. In contrast, the same SEC24D sequences expressed in the context of the Sec24c gene fail to rescue SEC24D-deficiency. Taken together, these results demonstrate a high degree of functional overlap between the SEC24C/D proteins and suggest that the deficiency phenotypes for each paralog are determined largely by tissue or developmental timing-specific differences in their gene expression programs.

Results

Identification of a dRMCE targeted ES cell clone

Direct microinjection of 102 zygotes generated from a Sec24c+/− X Sec24c+/+ cross with pDIRE and the Sec24c-d replacement construct (Fig. 1) failed to generate any progeny mice with the correctly targeted event; 65 were heterozygous for the Sec24c− allele containing the FRT and loxP sites required for dRMCE19 and 47 were wild type. While no targeted insertions were observed, 20/102 (20%) pups carried random insertions of the dRMCE replacement vector. A screen of 288 Sec24cGT ES cell clones co-electroporated with pDIRE and the Sec24c-d targeting construct also failed to yield any properly targeted colonies, though 18 random insertions of the Sec24c-d construct (6.25%, Table S1) were observed. However, analysis of a second set of 288 ES cell clones transfected with alternative Cre and FLP expression vectors identified a single clone carrying a potential targeted insertion of the dRMCE replacement construct into the Sec24c locus. A single round of subcloning generated pure clonal ES cell populations carrying the Sec24cc-d allele.

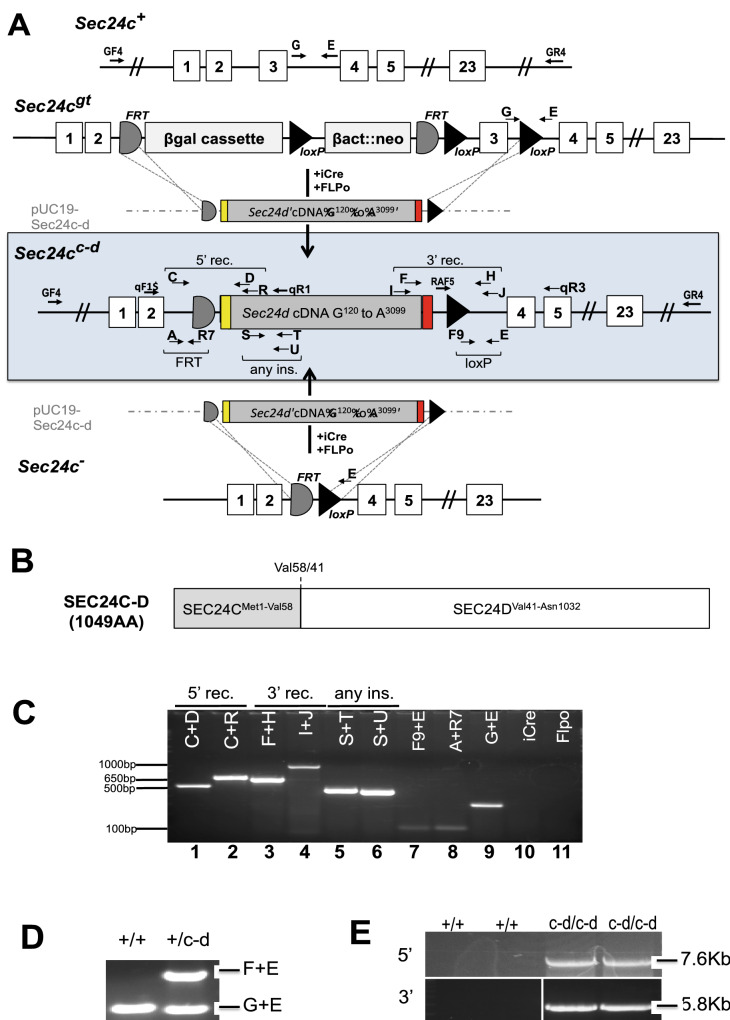

Figure 1.

Generation of the chimeric Sec24cc-d allele. (A) Schematic representation of dRMCE to generate the Sec24cc-d allele. The replacement vector pUC19-Sec24c-d contains the Sec24c intron 2 splice acceptor (yellow), the Sec24d coding sequence beginning with G120 (gray), and a stop codon followed by a poly A signal sequence (red). Arrows represent primers used for genotyping, long-range PCR, and RT-PCR (for sequences, see Table S2). (B) The SEC24C-D fusion protein encoded by the dRMCE generated Sec24cc-d allele, which contains the first 57 amino acids of SEC24C followed by the SEC24D sequence corresponding to the remaining ~ 95% of the SEC24C protein. Val58/41 (Val58 in SEC24C, Val41 in SEC24D) indicates the junction point for this chimeric protein. SEC24CMet1-Val58 and SEC24DMet1-Val41 have 34% protein sequence identity. (C) PCR results for dRMCE subclone 12275. Primer combinations are indicated at the top of each lane. Correct targeting was observed for the 5′ recombination (5′ rec) site (lanes 1 and 2) and the 3′ recombination (3′ rec) site (lanes 3 and 4). Additionally, the presence of the Sec24d cDNA (“any ins.”) (lanes 5,6), and the loxP and FRT sites (103 bp and 106 bp products in lanes 7,8, respectively) was confirmed. The signal in lane 9 is due to the Sec24c+ allele, confirming that ESC clone 12275 is heterozygous for the Sec24cc-d allele. Clone 12275 does not carry any random insertions of pCAGGS-iCre (lane 10) or pCAGGS-Flpo (lane 11). (D) A genotyping PCR assay on mouse genomic DNA from tail clip to distinguish between the wild type and Sec24cc-d allele using primers E, F, and G. (E) Long range PCR confirms correct targeting. Primers GF4 + U were used to amplify the 5′ arm resulting in a 7.6 kb product, and primers F and GR4 were used to amplify the 3′ arm to yield a 5.8 kb product. Primers were located outside the homology arms (GF4 and GR4) and within the Sec24d cDNA (F and U). Neither set of primers yields a band from the Sec24cwt allele.

Heterozygosity of the Sec24c-d allele does not affect embryonic development or gross morphology

One out of the three microinjected ES cell subclones achieved germline transmission, and mice carrying the Sec24cc-d allele were generated. The expected Mendelian ratio of Sec24c+/c-d mice was observed in N2 progeny of backcrosses to C57BL/6J mice (p > 0.38, Table 1A). Sec24c+/c-d mice were indistinguishable from their wild type littermates, exhibiting normal fertility and no gross abnormalities on standard autopsy examination (data not shown). There were also no differences in body weight at 4 and 6 weeks of age (Fig. 2B). While only a small number of wild type offspring were maintained beyond 100 days of age, there was no significant difference in lifespan between Sec24c+/c-d mice (n = 93) compared to controls (data not shown).

Table 1.

Results of Sec24c+/c-d backcrosses and intercrosses.

| Cross | Genotypes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Sec24c+/c-d X C57BL/6J | Sec24c+/+ | Sec24c+/c-d | p-value | ||

| Expected | 50% | 50% | |||

| Observed | |||||

| Chimera F1 (n = 38) | 58% (22) | 42% (16) | p > 0.33 | ||

| C57BL/6J N2 (n = 84) | 45% (38) | 55% (46) | p > 0.38 | ||

| Total (n = 122) | 49% (60) | 51% (62) | p > 0.85 | ||

| (B) Sec24c+/c-d X Sec24d+/GT |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/GT |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | |

| Observed | |||||

| F1 (n = 99): | 28.3% (28) | 27.2% (27) | 23.2% (23) | 21.2% (21) | > 0.72 |

| (C) Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT X C57BL/6J |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/GT |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | 25% | 25% | 25% | 25% | |

| Observed | |||||

| N2 (n = 19): | 36.8% (7) | 15.8% (3) | 21.1% (4) | 26.3% (5) | > 0.60 |

| (D) Sec24c+/c-d intercross | Sec24c+/+ | Sec24c+/c-d | Sec24cc-d/c-d | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected | 25% | 50% | 25% | ||

| Observed | |||||

| 2 weeks of age (n = 163) | 30% (49) | 70% (114) | 0 | < 1.70 × 10–13 | |

| P0 (n = 97, from 13 litters) | 23% (22) | 50% (49) | 27% (26*) | > 0.68 | |

| All embryonic time points (n = 109) | 28% (31) | 48% (52) | 24% (26) | > 0.78 | |

| E17.5 to E18.5 (n = 80, from 11 litters) | 29% (23) | 41% (41) | 20% (16) | > 0.30 | |

| E15.5 (n = 23, from 3 litters) | 26% (6) | 35% (8) | 39% (9) | > 0.11 | |

| E12.5 to E13.5 (n = 6, from 1 litter) | 33% (2) | 50% (3) | 17% (1) | > 0.63 | |

Distribution of progeny from (A) Sec24c+/c-d backcrosses (B) Sec24c+/c-d x Sec24d+/GT intercrosses, (C) Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT backcrosses and (D) Sec24c+/c-d intercrosses. Genotypes shown for chimera F1 only include those of chimera/ B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J F1 progeny with black coat color. All Sec24d+/GT mice used in this study were ≥ N18 on C57BL/6J background. For intercross data, p-values are calculated based on “others vs. rescue” genotypes (0.75:0.25). *all Sec24cc-d/c-d mice were dead at P0. The E15.5 time point in (D) contains genotypes for a single Sec24c+/c-d resorbed embryo and two Sec24cc-d/c-d resorbed embryos. All observed numbers are listed in parentheses.

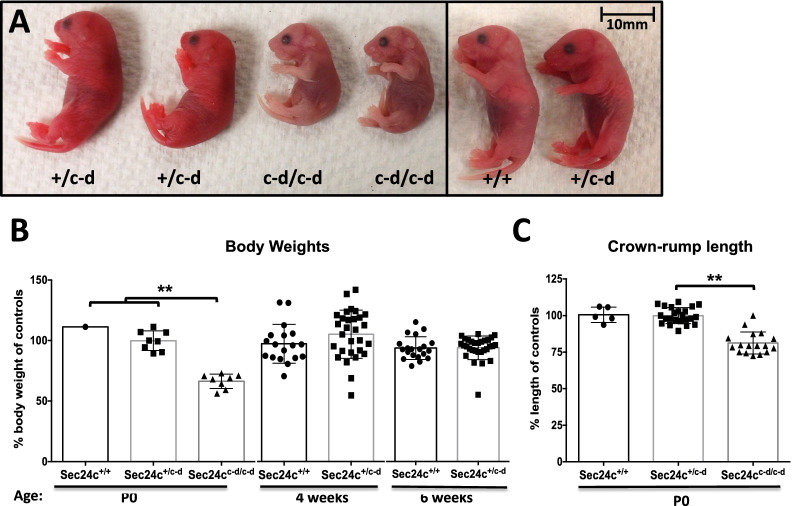

Figure 2.

Phenotypic analysis of Sec24c+/c-d intercross progeny at P0. (A) Side views of P0 pups from Sec24c+/c-d intercross taken shortly after birth. Sec24cc-d/c-d pups are much paler and smaller than their littermate controls, exhibited little spontaneous movement, and died within minutes of birth. (B) Body weight measurements at P0, 4 weeks, and 6 weeks of age. P0 normalized to average weight of controls (Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d) within the same litter set at 100%. Four week and 6 week data normalized to the average weight of wild type mice for each sex; data for males and females are pooled; no significant differences in weight were observed between Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d mice when broken down by sex. (C) Crown to rump length measurements at P0, normalized to average length of controls (Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d) within the same litter. ** indicates p < 0.0001; all other comparisons not significant, with p > 0.05. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

The Sec24cc-d allele rescues Sec24c−/− mice from embryonic lethality.

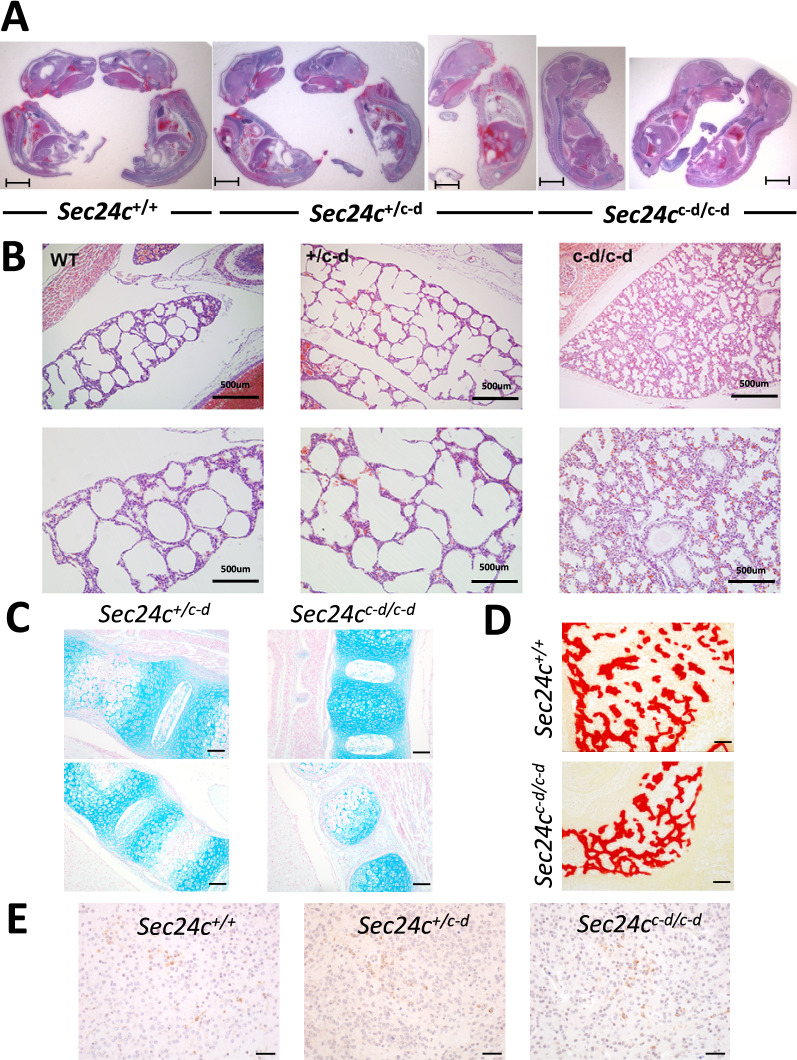

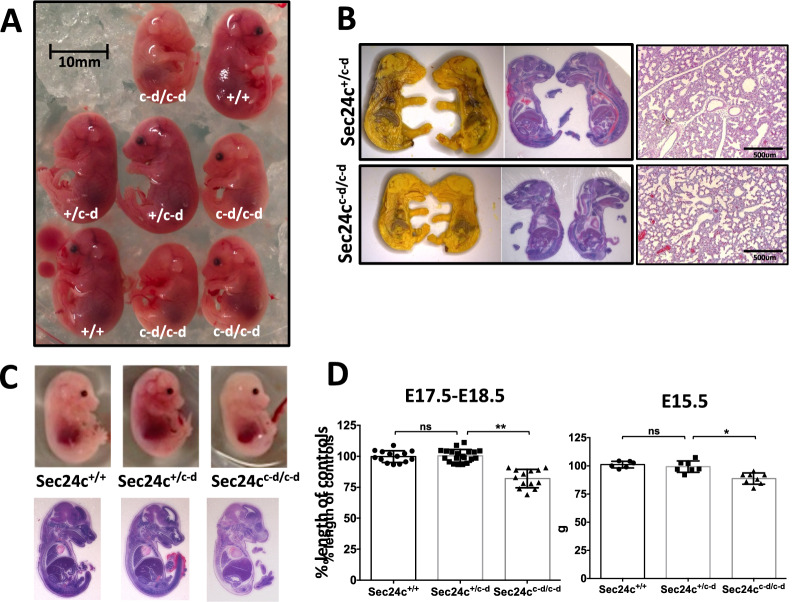

Table 1D shows the distribution of offspring from Sec24c+/c-d intercrosses. No Sec24cc-d/c-d mice were observed at weaning (0/163, p < 1.7 × 10–13, Table 1D). Genotyping of 31 P0 progeny observed to die shortly after birth, all notably smaller and paler than their surviving littermates (Fig. 2A), identified 26 as Sec24cc-d/c-d (p < 3.8 × 10–14). The remaining 5 pups were either wildtype (n = 3) or Sec24c+/c-d (n = 3). Taken together with the full set of progeny genotypes at P0 (n = 97), the observed number of Sec24cc-d/c-d offspring is consistent with the expected Mendelian ratios. Sec24cc-d/c-d pups were 20–30% smaller by weight than their littermate controls at P0 (Fig. 2B), were significantly shorter in crown-rump length (Fig. 2C), and often exhibited a hunched appearance involving the shoulder girdle and trunk. Gross autopsy and histologic analyses (performed blinded to genotype) failed to identify any obvious abnormality to account for the neonatal lethality in Sec24cc-d/c-d mice (Fig. 3A). Lungs of both heterozygous and wild type pups exhibited open alveoli lined by flattened alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 3B), while the alveoli of Sec24cc-d/c-d neonates were open but had thickened walls (5 out of 9) or were uninflated (4 out of 9), and lined by columnar epithelia (Fig. 3B). However, this lung pathology is unlikely to account for the neonatal death, as 7/9 neonates exhibited no breathing movements at delivery. Similarly, Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos did not exhibit a skeletal defect detectable by alcian blue or alizarin red stains (Fig. 3C,D). Furthermore, mice expressing SEC24D from the SEC24C locus demonstrate indistinguishable distribution of the serotonin transporter SERT in the brain by immunohistochemistry compared to wild type littermate controls (Fig. 3E), demonstrating that the SEC24C-D protein is capable of secreting a cargo previously shown to depend on SEC24C (but not on SEC24D) for secretion 20. At earlier embryonic time points (E12.5 to E17.5), viable Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos were observed at the expected ratios (p > 0.78, Table 1D), and although clearly smaller than their littermate controls, no other significant histopathologic differences were identified at E15.5 or E17.5 upon observation by an independent reviewer blinded to sample genotypes (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos were pink, alive, and moving at E18.5. Thus, expression of SEC24C-D in place of SEC24C is sufficient to support development to term, but not survival past birth.

Figure 3.

Histological assessment of Sec24c+/c-d intercross progeny at P0. (A) H&E stained longitudinal sections of P0 pups from Sec24c+/c-d intercross taken shortly after birth. A total of 16 animals were analyzed by H&E at this time point. Scale bars = 5 mm. (B) Low and higher magnification views of H&E stained sections through the lung of P0 mice collected shortly after birth. Analysis did not identify gross alterations in the morphology of the respiratory tree, although alveoli from Sec24cc-d/c-d pups were often uninflated and lined by columnar epithelium compared to the flattened epithelial lining wild type and Sec24c+/c-d alveoli. Lungs were fixed and sectioned in the context of the whole pup. Scale bars = 500 or 250 microns, as indicated. (C) Longitudinal sections through the vertebral column of Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos and wild type or Sec24c+/c-d controls illustrating regions of developing cartilage in forming vertebral bodies by Alcian blue (n = 3 for each genotype, Scale bars = 50 μm) and (D) alizarin red stains (n = 2 for each genotype). (E) Immunohistochemistry for SERT in Sec24cc-d/c-d and wild type control brain tissues (n = 3 per genotype). Scale bars = 20 μm.

Figure 4.

Phenotypic assessment of Sec24c+/c-d intercross embryos. (A) Side views of embryos from Sec24c+/c-d intercross at E17.5 (N = 8). Eye pigment variation is normal in inbred mice and did not track with the mouse genotypes. (B) Bouin’s solution fixed E18.5 embryos sectioned at the midline (left) and stained with H&E (center). H&E of 4% PFA fixed lungs from E18.5 embryos are shown at right. A total of 13 embryos were analyzed. (C) Whole mount and H&E images of E15.5 embryos from Sec24c+/c-d intercross (N = 15 analyzed). (D) Crown to rump length measurements at E17.5–18.5 and E15.5, normalized to average length of controls (Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d) within the same litter. ** indicates p < 0.0001; * indicates p < 0.002; ns indicates p > 0.05. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

The Sec24cc-d allele fails to complement disruption of Sec24d.

Table 2 shows the results of intercrosses between Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT and Sec24d+/GT15 mice. No Sec24c+/c-d Sec24dGT/GT progeny were observed at 2 weeks of age (n = 113, p < 1.43 × 10–5, Table 2) or at embryonic time points from the blastocyst stage to birth (n = 94, p < 7.56 × 10–5, Table 2), although a single Sec24c+/c-d Sec24dGT/GT embryo was detected at the 8-cell early morula stage. These results are indistinguishable from the pattern previously reported for Sec24dGT/GT mice15. These results indicate that the Sec24cc-d allele fails to complement disruption of Sec24d, a finding that is not surprising given that expression of Sec24d from the Sec24c locus is unlikely to recapitulate the exact expression of Sec24d from its own genomic locus. Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT mice were viable and healthy and observed in the expected numbers (p > 0.72, Table 1B,C), and like the Sec24c+/c-d mice, there was no significant difference in lifespan between Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT mice (n = 24) compared to controls.

Table 2.

Results of Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT x Sec24d+/GT intercrosses.

| Possible progeny of test cross |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24d+/GT |

Sec24c+/+ Sec24dGT/GT |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/+ |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24d+/GT |

Sec24c+/c-d Sec24dGT/GT |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected ratio with rescue | 14.3% (1/7) | 28.6% (2/7) | 0 (early lethal*) | 14.3% (1/7) | 28.6% (2/7) | 14.3% (1/7) | |

| Observed ratio | |||||||

| 2-weeks of age (n = 113) | 14% (16) | 38% (43) | 0% | 12% (13) | 36% (41) | 0% | 1.43 × 10–5 |

| Blastocyst to E18.5 (n = 94) | 11% (10) | 37% (35) | 1% (1) | 11% (10) | 40% (38) | 0% | 7.55 × 10–5 |

| E15.5 to E18.5 (n = 25) | 12% (3) | 40% (10) | 0% | 8% (2) | 40% (10) | 0% | 0.041 |

| E12.5 (n = 29) | 14% (4) | 24% (7) | 0% | 21% (6) | 41% (12) | 0% | 0.0279 |

| Blastocyst (n = 40) | 10% (4) | 43% (17) | 3% (1) | 5% (2) | 40% (16) | 0% | 0.009 |

| 8 cell morula (n = 9) | 0% | 33% (3) | 0% | 22% (2) | 33% (3) | 11% (1*) | 0.875 |

| Total (n = 216) | 12.0% (26) | 37.5% (81) | 0.5% (1) | 11.6% (25) | 38.0% (82) | 0.5% (1*) | 7.89 × 10–7 |

For intercross data, p-values are calculated based on “others versus rescue” genotypes (6/7: 1/7). *Not considered a “rescue” because Sec24dGT/GT morulas have been reported previously15.

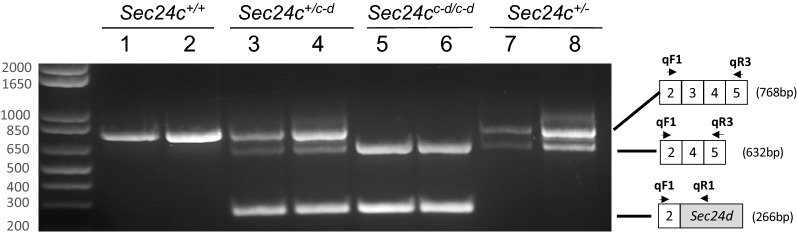

Low level of splicing around the Sec24cc-d allele.

RT-PCR analysis of RNA from both Sec24c+/c-d and Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos detected the expected mRNA resulting from splicing of Sec24c exon 2 to the Sec24cc-d fusion (Fig. 5, lanes 3–6). However, a low level of splicing around the dRMCE insertion (directly from Sec24c exon 2 to exon 4) was also observed in both Sec24c+/c-d and Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos, which may account for the incomplete rescue of the Sec24c deleted mice by the Sec24c-d allele. DNA sequencing analysis confirmed that this product contained the sequence of exons 2-4-5, consistent with a splicing event around the dRMCE insertion. The absence of exon 3 in this transcript (also seen in the Sec24c+/− samples) results in a frame-shift and early termination codon, as previously described12.

Figure 5.

Analysis of Sec24cc-d allele splicing. A three-primer RT-PCR reaction using qF1, qR1 and qR3 demonstrates the presence of Sec24cc-d allele splice variants. Primers qF1 and qR3 (see schematic at the right) detected mRNA transcripts from both the wild type allele (exons 2–3-4–5) and the transcript skipping exon 3 (2-4-5) present in mice carrying the Sec24cc-d allele, resulting from splicing around the dRMCE insertion (lanes 3–6), as well as mice carrying the Sec24c- allele, in which exon 3 was also excised (lanes 7–8). Primers qF1 and qR1 detect the mRNA transcript of the Sec24d cDNA insert in Sec24c+/c-d and Sec24cc-d/c-d mice (lanes 3–6), and this transcript is absent in wild type littermates (lanes 1–2), or Sec24c+/− mice (lanes 7–8).

Discussion

We show that SEC24D coding sequences inserted into the Sec24c locus (Sec24cc-d) largely rescue the early embryonic lethality observed in Sec24c−/− mice12. In contrast, and as expected, Sec24cc-d is unable to substitute for SEC24D in Sec24c+/c-d Sec24dGT/GT mice. Our findings suggest that SEC24D can largely or completely substitute functionally for SEC24C during embryonic development, when expressed from the Sec24c locus. The incomplete rescue of SEC24C deficiency by the substituted SEC24D sequences could be due to imperfect interaction between the residual 57 amino acids of SEC24C retained at the N-terminus with the remaining 992 C-terminal amino acids of SEC24D. Alternatively, the targeting of Sec24d cDNA sequences into the Sec24c locus could have potentially disrupted regulatory sequences important for the control of Sec24c gene expression. We also cannot exclude a “passenger” gene effect21 of another, incidental mutation in or near the Sec24cc-d locus, since only a single targeted allele was characterized. Finally, it should be noted that there are two alternative splice forms of Sec24c with one form containing an additional 23 amino acid insertion, with the paralogous sequences absent from SEC24D12. Thus, loss of a unique function conferred by this alternatively spliced form of SEC24C could also explain the perinatal lethality observed in Sec24cc-d/c-d mice. Although our data are consistent with complete functional equivalence between the SEC24C and SEC24D proteins, we cannot exclude the possibility that subtle paralog-specific differences between the SEC24C and SEC24D proteins could account for the Sec24cc-d/c-d phenotype. Consistent with our findings, zebrafish double morphant for sec24c and sec24d were previously reported to exhibit a more pronounced craniofacial defect compared to single sec24c/sec24d morphants22, consistent with at least partial functional overlap between sec24c and sec24d in zebrafish.

Other examples of complementation by gene replacement include Axin and Axin2/Conductin23, transcription factors Pax2 and Pax524, CCND1 and CCNE125, En-1 and En-226, N-myc and c-myc27, Oxt2 and Oxt128, and members of the Hox gene family, including Hoxa3 and Hoxd329, all of which were carried out by traditional knock-in approaches with cDNA targeting constructs and homologous recombination. The proteins encoded by these genes are involved in key tissue-specific transcriptional and regulatory pathways, where such complementarity at the level of protein function might be expected. Our finding of a similar complementarity between paralogs of a key cytoplasmic structural component present in all eukaryotic cells, has fewer precedents, aside from our recent demonstration of overlapping function for SEC23A and SEC23B30. Though we cannot exclude subtle differences in protein function, the remarkable extension of survival from E7.5 to E18.5 and generally normal pattern of embryonic development in Sec24cc-d/c-d mice demonstrate a high degree of functional overlap between SEC24C and SEC24D as well as the critical importance of spatial, temporal, and quantitative gene expression programs in determining the phenotypes of SEC24C and SEC24D deficiency.

Several secretory protein cargos have been shown to exhibit specificity for an individual SEC24 paralog, including the dependence of VANGL2 on SEC24B14, SERT, SLC6A14, and autotaxin on SEC24C20,31,32, the GABA1 transporter on SEC24D33, and others34. However, there is also evidence for significant overlap among the cargo repertoires of the mammalian Sec24 paralogs, particularly within the subfamilies34. Several cargo exit motifs are recognized by multiple SEC24 paralogs, including the DxE signal on VSV-G, and the IxM motif on syntaxin 5, both of which confer specificity for human SEC24A/B35. The human transmembrane protein p24-p23 exhibits a preference for SEC24C or SEC24D and is thought to be a cargo receptor for GPI-anchored CD59, explaining the specificity of the latter for SEC24C/D36. Similarly, PCSK9, which is dependent on SEC24A for ER export shows some overlap with SEC24B, both in vivo and in vitro, but none with SEC24C or D13.

Taken together with our results, these previous reports suggest significant functional overlap within but not between the SEC24A/B and SEC24C/D subfamilies. This model is also consistent with the ~ 58–60% sequence identity between SEC24A and B and between SEC24C and D, but only ~ 25% between the A/B and C/D subfamilies. This high degree of functional overlap within SEC24 subfamilies also suggests that the deficiency phenotypes observed for loss of function for any of the SEC24 paralogs may be due in large part to subtle differences in their finely tuned expression patterns, despite reports of generally ubiquitous expression for all 4 paralogs12. Consistent with these findings, the same Sec24cc-d allele reported here was recently shown to rescue the neuronal phenotype observed in mice with deletion of Sec24c in neuronal progenitor cells37.

Humans with compound heterozygous point mutations in SEC24D present with skeletal disorders such as Cole-Carpenter syndrome and severe osteogenesis imperfecta16, with the medaka vbi38 and the zebrafish bulldog22 mutants exhibiting similar skeletal defects. These results have been interpreted as indicating a specific critical role for SEC24D in the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins16,22,38. However, SEC24D-deficient mice exhibit very early embryonic lethality15, at a time in development well before the establishment of the skeletal system.

A similar discrepancy in phenotypes between mice and humans has been observed for SEC23B deficiency, which manifests as congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II in humans39–41, and perinatal lethality due to profound pancreatic degeneration in mice42–45. In contrast, mice with SEC23A deficiency exhibit a phenotype reminiscent of the human disease (cranio-lenticulo-sutural-dysplasia) resulting from loss of function mutations in SEC23A46–48. A recent report demonstrated that SEC23A can functionally replace SEC23B when expressed from the endogenous regulatory elements of Sec23b in mice30 and that the expression of the SEC23 paralogs has shifted during the course of evolution. Consistent with this model, SEC23B is the predominantly expressed paralog in the mouse pancreas with comparable expression of SEC23A/B in mouse bone marrow, while in humans, SEC23B is predominantly expressed in the bone marrow, with comparable expression of SEC23A/B in the pancreas. These results likely explain the disparate phenotypes of SEC23A and SEC23B deficiencies within and across species30.

Our data suggest that evolutionary shifts in the expression programs for the Sec24c and Sec24d genes may explain the disparate phenotypes resulting from SEC24C/D deficiencies between/across vertebrate species, despite considerable overlap at the level of SEC24C/D protein function. Such changes in relative levels of gene expression could result in major differences in dependence on one or the other paralog across tissue types, even among closely related species.

Methods

Cloning of Sec24c-d dRMCE construct pUC19-Sec24c-d

pUC19-Sec24c-d (Fig. 1) was generated by assembling the Sec24c-d cassette (GenBank accession KP896524) which contains a FRT sequence, the endogenous Sec24c intron 2 splice acceptor sequence, a partial Sec24d coding sequence (from G120 to A3099 in the cDNA sequence, encoding the SEC24D sequence starting at Val41 and the SV40 polyA sequence present in the Sec24cGT allele12. The entire cassette was inserted into pUC19 at the HindIII and EcoRI restriction sites, and the integrity of the sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmid purification and microinjections: pDIRE, the plasmid directing dual expression of both iCre and FLPo19 was obtained from Addgene (Plasmid 26745). Plasmid pCAGGS-FLPo was prepared by subcloning the FLPo-bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal sequences from the pFLPo plasmid49 into a pCAAGS promoter plasmid50. Plasmid pCAAGS-iCre was prepared by adding the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal to iCre (kind gift of Rolf Sprengel)51 and subcloning into a pCAGGS promoter plasmid. Plasmids pCAGGS-iCre and pCAGGS-FLPo contain the CAG promoter/enhancer, which drives recombinase expression of iCre or FLPo in fertilized mouse eggs52, and were used as an alternative source of iCre and FLPo for some experiments, as noted. All plasmids, including the Sec24c-d replacement construct described below, were purified using the Machery-Nagel NucleoBond® Xtra Maxi EF kit, per manufacturer’s instructions. All microinjections were carried out at the University of Michigan Transgenic Animal Model Core. Co-injections of pUC19-Sec24c-d with pDIRE were performed on zygotes generated from the in vitro fertilization of C57BL/6J oocytes with sperm from Sec24+/− male mice12. For each microinjection, 5 ng/μl of circular recombinase plasmid mixed with 5 ng/μl of circular donor plasmid was administered30,53,54 and microinjected zygotes were then transferred to pseudopregnant foster mothers. Tail clips for genomic DNA isolation were obtained from pups at 2 weeks of age. Notably, the FRT and LoxP sites are located in introns 2 and 3 of the Sec24cgt allele, respectively; therefore, we were limited to swapping the C-terminal 90% coding sequence of Sec24c with that of Sec24d.

Genotyping assays

Genotypes of potential transgenic mice and ES cell clones were determined using a series of PCR reactions at the Sec24c locus. All genotyping primers used in this study are listed in Table S2 and those for the Sec24c locus are depicted in Fig. 1, and expected band sizes are given in Table S3. Primers S, T, and U were used to amplify fragments of DNA unique to pUC19-Sec24c-d, which should detect targeted insertion at the Sec24c locus or random insertion elsewhere in the genome. Targeted insertion was detected using primer pairs flanking the FRT 5′ recombination site (primers C + primer D or R) and the loxP 3′ recombination site (primers I or F + primers H or J). Integration of pCAGGS-iCre, pCAGGS-FLPo, or pDIRE was detected with primer sets iCre10F + iCre10R or FLPo8F + FLPo8R. Mice carrying the Sec24dGT allele were genotyped as described previously15.

Transient electroporation of ES cells

ES cell clone EPD0241-2-A11 for Sec24ctm1a(EUCOMM)Wtsi (Sec24cGT allele12) was expanded and co-electroporated with pUC19-Sec24c-d and either pDIRE or pCAGGS-iCre and pCAGGS-FLPo. ES culture conditions for JM8.N4 ES cells were as recommended at http://www.KOMP.org. Electroporation was carried out as previously described (240 kV, 475 μF)19 with the exception that pUC19-Sec24c-d lacks a drug selection cassette that can be used to enrich for correct homologous recombination in mouse ES cells. After 1 week, individual ES cell colonies were plated in 96 well plates, 288 from cells transfected with pUC19-Sec24c-d and pDIRE, and 284 from cells transfected with pUC19-Sec24c-d, pCAGGS-iCre, and pCAGGS-FLPo. Cells were expanded and plated in triplicate for frozen stocks, DNA analysis, and G418 screening. To test for G418 sensitivity, cells were grown in selection media containing G418 for 1 week, and then fixed, stained, and evaluated for growth. Genomic DNA was prepared from each ES cell clone as previously described55 and resuspended in TE.

Subcloning of ES cells

PCR analysis demonstrated that clone 6-H9 contained a mixed population of cells, some of which were properly targeted with recombinations occurring at the outermost FRT and loxP sites, and others that still contained the parental Sec24cGT allele, consistent with the observed mixed resistance to G418 (Table S1). One round of subcloning produced six different subclones consisting of a pure population of properly targeted ES cells, each with one wild type Sec24c allele and one correctly targeted Sec24cc-d allele (Fig. 1C) and none carrying random insertions of either pCAGGS-iCre or pCAGGS-FLPo. The Sec24cc-d allele is registered with the MGI database as Sec24ctm1Dgi (MGI 5501092), but will be referred to as Sec24cc-d within this text.

Generation of Sec24c+/c-d mice

Three correctly targeted subclones of 6-H9 were used to generate mice carrying the Sec24cc-d allele (Fig. 1D). ES cell clones were cultured as described previously56 and expanded for microinjection. ES cell mouse chimeras were generated by microinjecting C57BL/6 N ES cells into albino C57BL/6J blastocysts as described57 and then bred to B6(Cg)-Tyrc-2J/J (JAX stock #000058) to achieve germ-line transmission. ES-cell-derived F1 black progeny were genotyped using primers G, E, and F (Fig. 1D). The Sec24cc-d allele was maintained on the C57BL/6J background by continuous backcrosses to C57BL/6J mice. Initial generations were also genotyped to remove any potential iCre and FLPo insertions.

Long-Range PCR

The integrity of the Sec24c locus with the newly inserted SEC24D sequence was confirmed by long-range PCR (Fig. 1E). Genomic DNA from Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d mice were used as templates for a long-range PCR spanning the original arms of homology used for construction of the Sec24cGT allele12. Primers used for long range-PCR are depicted in Fig. 1 and listed in Table S2. PCR was carried out using Phusion Hot Start II DNA Polymerase (Thermo Scientific), and products were separated on a 0.8% agarose gel.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from a tail clip of Sec24c+/+, Sec24c+/c-d, and Sec24cc-d/c-d embryos and liver biopsies from Sec24c+/− mice using the RNAeasy kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer’s instructions, with the optional DNaseI digest step included. cDNA synthesis and PCR were carried out in one reaction using SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum®Taq (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used for RT-PCR are depicted in Fig. 5 and listed in Table S2.

Timed matings

Timed matings were carried out for intercrosses of Sec24c+/c-d mice. Embryos were harvested at designated time point for genotyping and histological analysis. The embryo age was estimated from the time of coitus and embryonic appearance to within a 1-day range. Since normal numbers of null embryos were observed at each of these embryonic time points, finer resolution of embryonic stage would be unlikely to add significant additional insight. Genotyping was performed on genomic DNA isolated from tail clip from mice > E12.5 or from yolk sacs and embryonic tissue from embryos < E12.5 days of age.

Animal care

All animal care and use complied with the Principles of Laboratory and Animal Care established by the National Society for Medical Research. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Michigan approved all animal protocols in this study (protocol number PRO00009304). The study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines. Embryos and newly born pups were euthanized by decapitation.

Histology

Tissues, embryos and pups were fixed in Bouin’s solution (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature overnight, then transferred to 70% EtOH. Prior to embedding, fixed P0 pups and E17.5-E18.5 embryos were sectioned longitudinally at the midline. Processing, embedding, sectioning and H&E staining were performed at the University of Michigan Microscopy and Image Analysis Laboratory. Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described44,45 using SERT antibody (AB9726 Millipore) at a 1:2500 dilution (1 h incubation). Briefly, primary antibodies were applied following antigen retrieval and quenching of endogenous peroxidases. Subsequently, primary antibody was washed and polymer HRP secondary antibody was applied (Biocare, Concord CA). Negative controls were obtained by substitution of the primary antibody with universal negative reagent (Biocare, Concord CA). 3,3-diaminobenzidine was applied to visualize the reactions.

Alcian blue staining

Following deparaffinization and hydration with xylene and graded alcohols, formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded slides were mordanted in 3% Acetic Acid (Rowley Biochemical Inc., E-323-3) for three minutes then stained with Alcian Blue Solution (Rowley Biochemical Inc., E-323-1) for 30 min (pH 2.5). Slides were then washed for 10 min in running tap water, followed by a deionized Water rinse. Slides were counterstained in Nuclear Fast Red Solution (Rowley Biochemical Inc., E-323-2) then dehydrated and cleared through graded alcohols and xylene and coverslipped with Micromount (Leica cat# 3801731, Buffalo Grove, IL) using a Leica CV5030 automatic coverslipper.

Alizarin red staining

Following deparaffinization and hydration with xylene and graded alcohols, formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded sections were stained with 2% Alizarin Red, pH 4.2 (Rowley Biochemical Inc., C-206-1) for 30 s then blotted well prior to quick dehydration in Acetone and Acetone-Xylene (50–50) for 15 s each, then cleared in 3 changes of xylene. Slides were coverslipped as described above.

Embryonic phenotyping

Crown to rump length measurements were obtained using a caliper on fresh specimens or by measuring the length of the embryo in a longitudinal section. Body weights were obtained immediately after birth. To account for normal variations in embryonic length and weight between litters, all measurements were normalized to the average length of Sec24c+/+ and Sec24c+/c-d animals within a given litter (mean of controls = 100%). Values for each individual were then calculated based on that average for controls within the same litter.

Statistical analysis

To determine if there is a statistical deviation from the expected Mendelian ratios of genotypes from a given cross, the p-value reported is the χ2 value calculated using the observed ratio of genotypes compared to the expected ratio. All other p-values were calculated using Student’s unpaired t-test.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Elizabeth Hughes, Corey Ziebell, Galina Gavrilina, Wanda Filipiak, Keith Childs, and Debora VanHeyningen for microinjections and preparation of ES cell-mouse chimeras from dRMCE ES clone 12275 and the Transgenic Animal Model Core of the University of Michigan Biomedical Research Core Facilities. Core support was provided by the University of Michigan Multipurpose Arthritis Center, NIH grant number AR20557 and the University of Michigan Cancer Center, NIH grant number CA46592. All histology work was performed in the Microscopy and Image-analysis Laboratory (MIL) at the University of Michigan, Biomedical Research Core Facilities (BRCF) with the assistance of Judy Poore. The MIL is a multi-user imaging facility supported by NIH-NCI, O'Brien Renal Center, UM Medical School, Endowment for the Basic Sciences (EBS), Department of Cell & Developmental Biology (CDB), and the University of Michigan. E.J.A was partially supported by the Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant (T32-GM007315). This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (PO1HL057346, RO1HL039693 and R35HL135793 to DG and RO1HL148333 to RK). This work was also supported by The University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center P30CA046592 grant (providing support for R.K.), D.G. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The funders has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

E.J.A., R.K., and D.G. conceived the study and designed the experiments. E.J.A. and R.K. performed the majority of the experiments and A.K., A.C., K.T., M.E., P.G., V.T., G.Z., M.H., and S.O. performed additional experiments. T.S. generated the transgenic mice. E.J.A., R.K., and D.G. analyzed most of the experimental data. E.J.A., R.K., and D.G. wrote the manuscript with help from all authors. All the authors contributed to the integration and discussion of the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Elizabeth J. Adams and Rami Khoriaty.

Contributor Information

Rami Khoriaty, Email: ramikhor@umich.edu.

David Ginsburg, Email: ginsburg@umich.edu.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-00579-x.

References

- 1.Bonifacino JS, Glick BS. The mechanisms of vesicle budding and fusion. Cell. 2004;116:153–166. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palade G. Intracellular aspects of the process of protein synthesis. Science. 1975;189:347–358. doi: 10.1126/science.1096303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budnik A, Stephens DJ. ER exit sites—Localization and control of COPII vesicle formation. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:3796–3803. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee MCS, Miller EA, Goldberg J, Orci L, Schekman R. Bi-directional protein transport between the ER and golgi. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:87–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.105307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee MCS, Miller EA. Molecular mechanisms of COPII vesicle formation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007;18:424–434. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bickford LC, Mossessova E, Goldberg J. A structural view of the COPII vesicle coat. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MCS, Orci L, Hamamoto S, Futai E, Ravazzola M, Schekman R. Sar1p N-terminal helix initiates membrane curvature and completes the fission of a COPII vesicle. Cell. 2005;122:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller E, Antonny B, Hamamoto S, Schekman R. Cargo selection into COPII vesicles is driven by the Sec24p subunit. EMBO J. 2002;21:6105–6113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aridor M, Weissman J, Bannykh S, Nuoffer C, Balch WE. Cargo selection by the copii budding machinery during export from the ER. J. Cell Biol. 1998;141:61–70. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barlowe C, Schekman R. SEC12 encodes a guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor essential for transport vesicle budding from the ER. Nature. 1993;365:347–349. doi: 10.1038/365347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagano A, Letourneur F, Garcia-Estefania D, Carpentier JL, Orci L, Paccaud JP. Sec24 proteins and sorting at the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:7833–7840. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.7833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams EJ, Chen X-W, O'Shea KS, Ginsburg D. Mammalian COPII component SEC24C is required for embryonic development in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289(30):20858–20870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.566687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen X-W, Wang H, Bajaj K, Zhang P, Meng Z-X, Ma D, Bai Y, Liu H-H, Adams E, Baines A, Yu G, Sartor MA, Zhang B, Zhengping Y, Lin J, Young SG, Schekman R, Ginsburg D. SEC24A deficiency lowers plasma cholesterol through reduced PCSK9 secretion. Elife. 2013;2:e00444. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merte J, Jensen D, Wright K, Sarsfield S, Wang Y, Schekman R, Ginty DD. Sec24b selectively sorts Vangl2 to regulate planar cell polarity during neural tube closure. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010;12:41–46. doi: 10.1038/ncb2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baines AC, Adams EJ, Zhang B, Ginsburg D. Disruption of the Sec24d gene results in early embryonic lethality in the mouse. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garbes L, Kim K, Rieß A, Hoyer-Kuhn H, Beleggia F, Bevot A, Kim MJ, Huh YH, Kweon H-S, Savarirayan R, Amor D, Kakadia PM, Lindig T, Kagan KO, Becker J, Boyadjiev SA, Wollnik B, Semler O, Bohlander SK, Kim J, Netzer C. Mutations in SEC24D, encoding a component of the COPII machinery, cause a syndromic form of osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson L, Venkataraman S, Stevenson P, Yang Y, Burton N, Rao J, Fisher M, Baldock RA, Davidson DR, Christiansen JH. EMAGE mouse embryo spatial gene expression database: 2010 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D703–D709. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupp M, Marquardt JU, Sahin U, Galle PR, Castle J, Teufel A. RNA-Seq Atlas, a reference database for gene expression profiling in normal tissue by next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1184–1185. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osterwalder M, Galli A, Rosen B, Skarnes WC, Zeller R, Lopez-Rios J. Dual RMCE for efficient re-engineering of mouse mutant alleles. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:893–895. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sucic S, El-Kasaby A, Kudlacek O, Sarker S, Sitte HH, Marin P, Freissmuth M. The serotonin transporter is an exclusive client of the coat protein complex II (COPII) component SEC24C. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:16482–16490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.230037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Westrick RJ, Mohlke KL, Korepta LM, Yang AY, Zhu G, Manning SL, Winn ME, Dougherty KM, Ginsburg D. Spontaneous Irs1 passenger mutation linked to a gene-targeted SerpinB2 allele. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16904–16909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012050107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarmah S, Barrallo-Gimeno A, Melville DB, Topczewski J, Solnica-Krezel L, Knapik EW. Sec24D-dependent transport of extracellular matrix proteins is required for zebrafish skeletal morphogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chia IV, Costantini F. Mouse Axin and Axin2/conductin proteins are functionally equivalent in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:4371–4376. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.11.4371-4376.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouchard M, Pfeffer P, Busslinger M. Functional equivalence of the transcription factors Pax2 and Pax5 in mouse development. Development. 2000;127:3703–3713. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geng Y, Whoriskey W, Park MY, Bronson RT, Medema RH, Li T, Weinberg RA, Sicinski P. Rescue of cyclin D1 deficiency by knockin cyclin E. Cell. 1999;97:767–777. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanks M, Wurst W, Anson-Cartwright L, Auerbach A, Joyner A. Rescue of the En-1 mutant phenotype by replacemnt of En-1 with En-2. Science. 1995;269:679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.7624797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malynn BA, de Alboran IM, O'Hagan RC, Bronson R, Davidson L, DePinho RA, Alt FW. N-myc can functionally replace c-myc in murine development, cellular growth, and differentiation. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1390–1399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suda Y, Nakabayashi J, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Functional equivalency between Otx2 and Otx1 in development of the rostral head. Development. 1999;126:743–757. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greer JM, Puetz J, Thomas KR, Capecchi MR. Maintenance of functional equivalence during paralogous Hox gene evolution. Nature. 2000;403:661–665. doi: 10.1038/35001077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khoriaty R, Hesketh GG, Bernard A, Weyand AC, Mellacheruvu D, Zhu G, Hoenerhoff MJ, McGee B, Everett L, Adams EJ, Zhang B, Saunders TL, Nesvizhskii AI, Klionsky DJ, Shavit JA, Gingras AC, Ginsburg D. Functions of the COPII gene paralogs SEC23A and SEC23B are interchangeable in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E7748–E7757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805784115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovalchuk V, Samluk L, Juraszek B, Jurkiewicz-Trzaska D, Sucic S, Freissmuth M, Nalecz KA. Trafficking of the amino acid transporter B(0,+) (SLC6A14) to the plasma membrane involves an exclusive interaction with SEC24C for its exit from the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2019;1866:252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyu L, Wang B, Xiong C, Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhang J. Selective export of autotaxin from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:7011–7022. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.774356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farhan H, Reiterer V, Korkhov VM, Schmid JA, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH. Concentrative export from the endoplasmic reticulum of the Y-aminobutyric acid transporter 1 requires binding to SEC24D. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:7679–7689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adolf F, Rhiel M, Hessling B, Gao Q, Hellwig A, Bethune J, Wieland FT. Proteomic profiling of mammalian COPII and COPI vesicles. Cell Rep. 2019;26:250–265.e255. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mancias JD, Goldberg J. Structural basis of cargo membrane protein discrimination by the human COPII coat machinery. EMBO J. 2008;27:2918–2928. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonnon C, Wendeler MW, Paccaud J-P, Hauri H-P. Selective export of human GPI-anchored proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 2010;123:1705–1715. doi: 10.1242/jcs.062950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang B, Joo JH, Mount R, Teubner BJW, Krenzer A, Ward AL, Ichhaporia VP, Adams EJ, Khoriaty R, Peters ST, Pruett-Miller SM, Zakharenko SS, Ginsburg D, Kundu M. The COPII cargo adapter SEC24C is essential for neuronal homeostasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2018;128:3319–3332. doi: 10.1172/JCI98194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohisa S, Inohaya K, Takano Y, Kudo A. sec24d encoding a component of COPII is essential for vertebra formation, revealed by the analysis of the medaka mutant, vbi. Dev. Biol. 2010;342:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwarz K, Iolascon A, Verissimo F, Trede NS, Horsley W, Chen W, Paw BH, Hopfner K-P, Holzmann K, Russo R, Esposito MR, Spano D, De Falco L, Heinrich K, Joggerst B, Rojewski MT, Perrotta S, Denecke J, Pannicke U, Delaunay J, Pepperkok R, Heimpel H. Mutations affecting the secretory COPII coat component SEC23B cause congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II. Nat. Genet. 2009;41:936–940. doi: 10.1038/ng.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bianchi P, Fermo E, Vercellati C, Boschetti C, Barcellini W, Iurlo A, Marcello AP, Righetti PG, Zanella A. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II (CDAII) is caused by mutations in the SEC23B gene. Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:1292–1298. doi: 10.1002/humu.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khoriaty R, Vasievich MP, Ginsburg D. The COPII pathway and hematologic disease. Blood. 2012;120:31–38. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-292086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao J, Zhu M, Wang H, Afelik S, Vasievich MP, Chen X-W, Zhu G, Jensen J, Ginsburg D, Zhang B. SEC23B is required for the maintenance of murine professional secretory tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109:E2001–2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209207109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khoriaty R, Vasievich MP, Jones M, Everett L, Chase J, Tao J, Siemieniak D, Zhang B, Maillard I, Ginsburg D. Absence of a red blood cell phenotype in mice with hematopoietic deficiency of SEC23B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014;34(19):3721–3734. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00287-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khoriaty R, Everett L, Chase J, Zhu G, Hoenerhoff M, McKnight B, Vasievich MP, Zhang B, Tomberg K, Williams J, Maillard I, Ginsburg D. Pancreatic SEC23B deficiency is sufficient to explain the perinatal lethality of germline SEC23B deficiency in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:27802. doi: 10.1038/srep27802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khoriaty R, Vogel N, Hoenerhoff MJ, Sans MD, Zhu G, Everett L, Nelson B, Durairaj H, McKnight B, Zhang B, Ernst SA, Ginsburg D, Williams JA. SEC23B is required for pancreatic acinar cell function in adult mice. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2017;28(15):2146–2154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e17-01-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyadjiev SA, Fromme JC, Ben J, Chong SS, Nauta C, Hur DJ, Zhang G, Hamamoto S, Schekman R, Ravazzola M, Orci L, Eyaid W. Cranio-lenticulo-sutural dysplasia is caused by a SEC23A mutation leading to abnormal endoplasmic-reticulum-to-Golgi trafficking. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/ng1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang MR, Lapierre LA, Frotscher M, Goldenring JR, Knapik EW. Secretory COPII coat component Sec23a is essential for craniofacial chondrocyte maturation. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1198–1203. doi: 10.1038/ng1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu M, Tao J, Vasievich MP, Wei W, Zhu G, Khoriaty RN, Zhang B. Neural tube opening and abnormal extraembryonic membrane development in SEC23A deficient mice. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15471. doi: 10.1038/srep15471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raymond CS, Soriano P. High-efficiency FLP and ΦC31 site-specific recombination in mammalian cells. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene. 1991;108:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90434-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimshek DR, Kim J, Hübner MR, Spergel DJ, Buchholz F, Casanova E, Stewart AF, Seeburg PH, Sprengel R. Codon-improved Cre recombinase (iCre) expression in the mouse. Genesis. 2002;32:19–26. doi: 10.1002/gene.10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Araki K, Araki M, Miyazaki J, Vassalli P. Site-specific recombination of a transgene in fertilized eggs by transient expression of Cre recombinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995;92:160–164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ohtsuka M, Ogiwara S, Miura H, Mizutani A, Warita T, Sato M, Imai K, Hozumi K, Sato T, Tanaka M, Kimura M, Inoko H. Pronuclear injection-based mouse targeted transgenesis for reproducible and highly efficient transgene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e198–e198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohtsuka M, Miura H, Nakaoka H, Kimura M, Sato M, Inoko H. Targeted transgenesis through pronuclear injection of improved vectors into in vitro fertilized eggs. Transgenic Res. 2012;21:225–226. doi: 10.1007/s11248-011-9505-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramirez-Solis R, Rivera-Perez J, Wallace JD, Wims M, Zheng H, Bradley A. Genomic DNA microextraction: A method to screen numerous samples. Anal. Biochem. 1992;201:331–335. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90347-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hughes E, Saunders T. Gene Targeting in Embryonic Stem Cells. Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seong E, Saunders TL, Stewart CL, Burmeister M. To knockout in 129 or in C57BL/6: That is the question. Trends Genet. 2004;20:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.