Abstract

Background

With limited vaccine supplies, an informed position on the status of SARS-CoV-2 infection in people can assist the prioritization of vaccine deployment.

Objectives

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the global and regional SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences around the world.

Data sources

We systematically searched peer-reviewed databases (PubMed, Embase and Scopus), and preprint servers (medRxiv, bioRxiv and SSRN) for articles published between 1 January 2020 and 30 March 2021.

Study eligibility criteria

Population-based studies reporting the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the general population were included.

Participants

People of different age groups, occupations, educational levels, ethnic backgrounds and socio-economic status from the general population.

Interventions

There were no interventions.

Methods

We used the random-effects meta-analyses and empirical Bayesian method to estimate the pooled seroprevalence and conducted subgroup and meta-regression analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity as well as the relationship between seroprevalence and socio-demographics.

Results

We identified 241 eligible studies involving 6.3 million individuals from 60 countries. The global pooled seroprevalence was 9.47% (95% CI 8.99–9.95%), although the heterogeneity among studies was significant (I2 = 99.9%). We estimated that ∼738 million people had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (as of December 2020). Highest and lowest seroprevalences were recorded in Central and Southern Asia (22.91%, 19.11–26.72%) and Eastern and South-eastern Asia (1.62%, 1.31–1.95%), respectively. Seroprevalence estimates were higher in males, persons aged 20–50 years, in minority ethnic groups living in countries or regions with low income and human development indices.

Conclusions

The present study indicates that the majority of the world's human population was still highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection in mid-2021, emphasizing the need for vaccine deployment to vulnerable groups of people, particularly in developing countries, and for the implementation of enhanced preventive measures until ‘herd immunity’ to SARS-CoV-2 has developed.

Keywords: General population, Meta-analysis, SARS-CoV-2, Seroprevalence, Serum antibodies, Subgroup analyses

Introduction

Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a major health challenge, devastating many communities and economies around the world [1,2]. From the start of the pandemic to mid-August 2021, ∼211 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 4.5 million deaths were recorded worldwide [3]. However, the number of reported cases is likely substantially underestimated [4], mainly due to a large number of asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic individuals and/or a limited availability of diagnostic testing, particularly in low-income countries [[5], [6], [7]]. According to a new analysis by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), COVID-19 has caused ∼12.2 million deaths—more than twice the official numbers reported [4].

Serological tests can be used to detect individuals with current or past infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Such tests can be used to estimate the cumulative prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease transmission over time [8]. Previous studies have shown that specific serum antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 can increase within 2–3 weeks following primary infection and remain detectable for 3–6 months after exposure [[9], [10], [11]]. Measuring the prevalence and levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 serum antibodies in people can be helpful in prioritizing the vaccination of susceptible/unexposed (i.e. seronegative) individuals [12]. Therefore, population-based serological screening at the national and regional levels can significantly assist health authorities to understand the toll of the epidemic, predict future spread and prioritize which people to vaccinate if/when vaccine supply is limited [12].

In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, some studies estimated the seroprevalences in different countries; however, only a few investigated seroprevalence across the globe (from early to mid-2020) [5,13,14]. More than 1 year on, it is now critical to re-assess the situation to be in an informed position about the global and regional seroprevalences, so that there is some understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 immune status at a time when people are being vaccinated. An informed position should enable the prioritization of vaccine deployment to communities and age/risk groups [13]. Here, we extend our previous study [5] to provide a detailed update on global and regional SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences around the world.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis under the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15]. Our protocol is registered (CRD42021238432) in PROSPERO. We searched three peer-reviewed databases (i.e. PubMed, Embase and Scopus) and preprint servers (i.e. medRxiv, bioRxiv and SSRN) using predefined search terms for SARS-CoV-2 and seroprevalence (Fig. S1). We also sourced studies from Google Scholar and the bibliographies in published works. Studies published between 1 January 2020 and 30 March 2021, without language or geographical restriction, were included. We only included population-based studies of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the general population. In addition to the exclusion criteria (Table S1), we did not consider studies of groups of people at a high risk of acquiring infection, including the ‘homeless’, those with household exposure to family members with confirmed COVID-19 and healthcare and migrant workers. We also excluded studies reporting the kinetics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Extraction of data and evaluation of risk of bias

Two independent experts extracted data on study and sample characteristics and seroprevalence data from all of the eligible studies using a predefined form (cf. [5]). The primary focus was the seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in the ‘general population’—which we defined as randomly selected people of different age groups, occupations, educational levels, ethnic backgrounds and socio-economic status. The samples originated from people from households, communities, blood donors, living in defined geographical regions, whose COVID-19 status was unknown [5,13]. Seroprevalence was defined as the number of people with specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (IgG, IgM and/or IgA) at, or above, a designated threshold value divided by the total number of people screened for serum antibodies. We employed the cut-off point and seropositivity values defined by authors in peer-reviewed publications. We recorded the numbers of people who tested seropositive for IgG and/or IgM (as these were the antibody classes tested for in most eligible studies). If seropositivity for distinct antibody isotypes was reported, we extracted the numbers of people seropositive for specific IgG antibody only, as anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG serum antibody persists for a longer period in serum than IgM or IgA [14,16,17]. To avoid repeated inclusion of sequential cross-sectional studies, data for the total number of participants and seropositive people tested during the whole study period were extracted. For longitudinal studies, data were extracted only for the first blood collection. If a study used multiple serological assays, we extracted results for the assay with the highest diagnostic specificity and sensitivity.

When available, seroprevalence data, stratified according to age group, gender and ethnicity, were extracted from each individual study. Most studies categorized participants into groups of ≤19, 20–49, 50–64 and ≥65 years of age (model 1) or groups of 0–9, 10–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49,50–59, 60–69,70–79 and ≥80 years of age (model 2). Therefore, we extracted data for each of these categories for two distinct subgroup analyses. Countries and territories for which seroprevalence data were available were classified according to ‘Sustainable Development Goal’ (SDG) regions or sub-regions [18], gross national income [19] and human development index (HDI) [20].

To determine whether there was an association between seroprevalence rate and confirmed COVID-19 cases or deaths in a country, we extracted data on the total numbers of confirmed cases and deaths on the last date of the sampling period reported in each study [21]. We estimated the total numbers of people (i.e. females and males) exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in 2020 in particular geographical regions, as defined by the United Nations Population Division (UNPD) [22], and worldwide. The risk of bias of studies included in the meta-analysis was assessed using the modified Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tool [23].

Meta-analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata (v.16 Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). To stabilize the variances, we first transformed the raw seroprevalence estimates using the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation [24]. Due to the intrinsic heterogeneity between epidemiological studies, we used the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model (REM) to conservatively estimate the pooled seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in the general population [25]. We calculated the pooled seroprevalences at 95% CIs using the ‘metaprop’ command in Stata. The heterogeneity between studies was assessed using Cochran's Q test and quantified using the I 2 statistic. An I 2 of >75% indicates substantial heterogeneity [26]. We also conducted a proportion meta-analysis with the empirical Bayes method, as it deals more adequately with heterogeneity than the classical random-effects model in situations with zero-event studies [27,28]. We presented the pooled seroprevalence estimates with 95% credibility intervals.

Subgroup analyses, according to SDG regions and sub-regions, sex, age, ethnicity, place of residence, national income level, HDI, serological method (e.g. ELISA, lateral flow immunoassay (LFIA), chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay (CLIA), etc.), type of assay (commercial kit or in-house assay) used and risk of bias, were conducted to explore the possible reasons for the observed heterogeneity between eligible studies. Corresponding prevalence ratios (PRs) were estimated for variables subjected to subgroup analysis. We also performed some subgroup analyses to assess the trend of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence over time (at intervals of 20–30 days) and at the start date of a COVID-19 epidemic within a country. To assess the effect of these variables on seroprevalence, we carried out random-effects meta-regression analyses using the ‘metareg’ command in STATA [29]. Further, we performed meta-regression analyses to assess whether seroprevalence was associated with the total number of confirmed cases or deaths in particular countries. The numbers of SARS-CoV-2-infected people (worldwide and in particular regions) were inferred by multiplying the pooled seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 by corresponding population size (in 2020)—available via UNPD. Publication bias was assessed by logit transformation of effect size and sample size, instead of the inverse of the standard error, because the conventional funnel plot and publication bias tests for meta-analyses of proportion studies with low proportion outcomes are inaccurate [30].

Results

Study characteristics

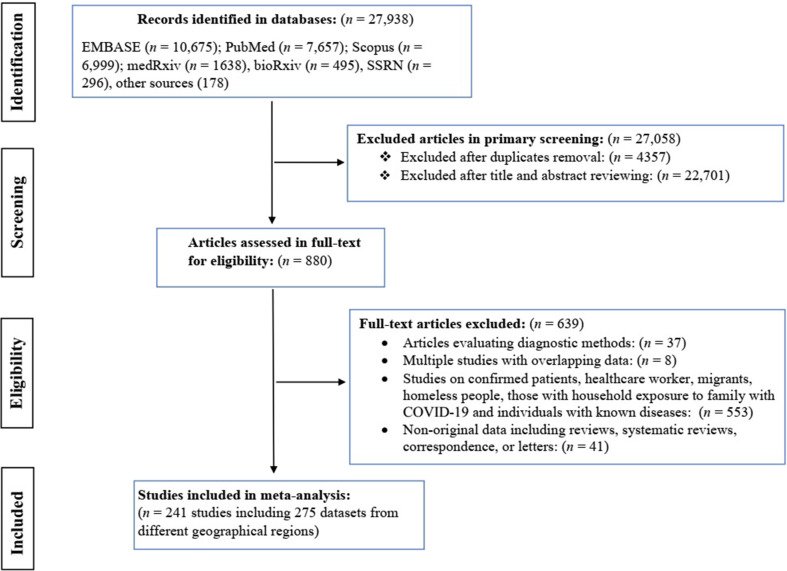

From January 2020 to March 2021, we identified 27 938 records from bibliographic databases, with 25 331 from peer-reviewed databases, 2429 from preprint servers and 178 from Google Scholar or article references. After removing duplicate records (n = 4357) and irrelevant articles (n = 22 701), 880 articles reporting SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence were assessed for eligibility (Fig. 1 ). A total of 241 articles containing 275 datasets met the inclusion criteria for quantitative synthesis; these studies involved 6 367 734 people from 60 countries in seven SDG regions. Regions with the highest numbers of datasets were Europe and Northern America (n = 163), Eastern and South-eastern Asia (n = 32), and Latin America and the Caribbean (n = 31). Detailed information on individual studies included is presented in Table S2.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy and study selection process of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence studies from 1 January 2020 to 30 March 2021.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence

Of 6 367 734 people (represented in 275 datasets), 519 407 had specific serum antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. As the results of the Bayesian and REM analyses were similar (Table S3), we focused on the REM analysis. The global SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence (for 60 countries) was 9.47% (95% CI 8.99–9.95%), although heterogeneity among studies was substantial (I 2 = 99.9%, p < 0.001). The extrapolation to the global population (in 2020) indicated that ∼738 million individuals (range: 700 752 407–775 582 474) were SARS-CoV-2 infected (up to December 2020; see Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Global and regional SARC-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimates, and estimated numbers of SARC-CoV-2-infected people (results from 241 studies containing 275 datasets performed in 60 countries)

| SDG regionsa (number of datasets available, for a particular region) | Number of people screened (total) | Number of sero-positive people | REM pooled seroprevalence % (95% CI) | Estimated global or regional population (2020) | Estimated number of SARS-CoV-2-infected people (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 6 367 734 | 519 407 | 9.47 (8.99–9.95) | 7 794 798 739 | 738 148 440 (700 752 407–775 582 474) |

| Europe and Northern America (163) | 5 510 532 | 439 586 | 7.29 (6.58–8.01) | 1 116 505 673 | 81 393 263 (73 466 073–89 432 104) |

| Northern America (56) | 4 246 529 | 339 133 | 5.92 (4.63–7.21) | 368 869 647 | 21 837 083 (17 078 664–26 595 501) |

| Western Europe (41) | 609 901 | 60 542 | 6.16 (4.42–7.91) | 196 146 316 | 12 082 613 (8 669 667–15 515 173) |

| Southern Europe (35) | 194 953 | 15 796 | 9.71 (8.09–11.32) | 152 215 230 | 14 780 098 (12 314 212–17 230 764) |

| Eastern Europe (9) | 31 572 | 4525 | 17.71 (10.58–24.83) | 293 013 231 | 51 892 643 (31 000 799–72 755 185) |

| Northern Europe (22) | 427 577 | 19 590 | 4.66 (3.84–5.47) | 106 261 249 | 4 951 774 (4 080 431–5 812 490) |

| Eastern & South-eastern Asia (32) | 347 895 | 7225 | 1.62 (1.31–1.95) | 2 346 709 459 | 38 016 693 (30 741 893–45 760 834) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean (31) | 166 224 | 11 963 | 18.29 (16.59–19.99) | 653 962 331 | 119 609 710 (108 492 350- 130 727 069) |

| South America (25) | 131 522 | 8710 | 19.41 (17.61–21.22) | 430 759 766 | 83 610 470 (75 856 794- 91 407 222) |

| Caribbean & Central America (6) | 34 702 | 3253 | 13.31 (8.59–18.04) | 223 202 565 | 29 708 261 (19 173 100- 40 265 742) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (15) | 32 514 | 5093 | 18.76 (13.09–24.42) | 1 094 365 629 | 205 302 992 (143 252 460- 267 244 086) |

| Western Africa (4) | 7 366 | 536 | 22.73 (4.83–40.63) | 401 861 254 | 91 343 063 (19 409 898- 163 276 227) |

| Eastern Africa (8) | 19 128 | 1815 | 11.39 (7.48–15.31) | 445 405 606 | 50 731 698 (33 316 339–68 191 598) |

| Middle and Southern Africa (3) | 6017 | 2742 | 31.66 (8.18–55.14) | 247 098 769 | 78 231 470 (20 212 679–136 250 261) |

| Central and Southern Asia (20) | 171 519 | 34 841 | 22.91 (19.11–26.72) | 1 940 369 612 | 444 538 678 (370 804 632–518 466 760) |

| Northern Africa and Western Asia (13) | 133 711 | 20 661 | 9.21 (3.72–14.68) | 525 869 272 | 48 432 559 (19 562 336–77 197 609) |

| Australia and New Zealand (1) | 5339 | 38 | 0.71 (0.51–0.98) | 30 322 117 | 215 287 (154 642–297 156) |

Sustainable Development Goal regions as defined by the United Nations.

According to SDG regions (Table 1), the highest seroprevalence estimates were in Central and Southern Asia (22.91%, 19.11–26.72%), sub-Saharan Africa (18.76%, 13.09–24.42%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (18.29%, 16.59–19.99%); the lowest seroprevalence was in the Eastern and South-eastern Asia (1.62%, 1.31–1.95%). Seroprevalence estimates in Northern Africa and Western Asia and Europe and North America were 9.21% (3.72–14.68%) and 7.29% (6.58–8.01%), respectively. Only one study was available for Australia, suggesting a seroprevalence of 0.71% (0.51–0.98%).

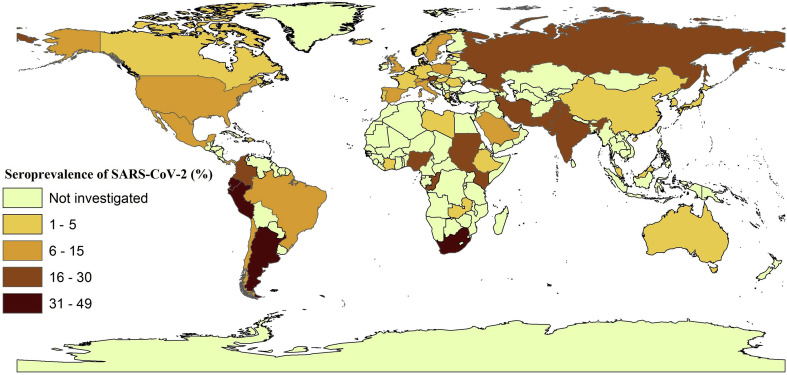

In countries with three or more available studies, the highest seroprevalences were recorded in Pakistan (28.8%), Russia (27.4%), India (23.3%), Colombia (19.5%), Iran (16.9%), Kenya (16.8%), Austria (15.5%), Mexico (15.4%), Sweden (15.02), Saudi Arabia (11.2%), Chile (10.7%), Switzerland (10.4%), Brazil (10.4%), Italy (10.0%) and Spain (9.7%). SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the United States was estimated at 6.45% (5.01–7.88%). Fig. 2 shows the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimates for individual countries, and Table 2 ranks countries according to estimated total numbers of seropositive individuals. The funnel plot for pooled seroprevalence is shown in Fig. S2; this plot was symmetrical, indicating there was no publication bias in the studies included.

Fig. 2.

Estimated SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences in the general human population in different countries using the geographic information system (GIS).

Table 2.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimates, and estimated numbers of SARS-CoV-2-infected people in 60 countries for which multiple datasets were available

| Country (number of datasets available for a particular country) | Number of people screened (total) | Number of sero-positive people | Pooled seroprevalence, % (95% CI) | Estimated population size (2020) | Estimated number of SARS-CoV-2-infected people (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India (13) | 151 235 | 31 800 | 23.38 (18.55–28.22) | 1 380 004 385 | 322 645 025 (255 990 813–389 437 237) |

| Pakistan (3) | 3595 | 836 | 28.88 (2.24–55.52) | 220 892 340 | 63 793 708 (4 947 988–122 639 427) |

| Nigeria (2) | 298 | 93 | 30.05 (24.93–35.16) | 206 139 589 | 61 944 946 (51 390 600–72 478 679) |

| Russia (5) | 12 734 | 3841 | 27.44 (15.11–39.76) | 145 934 462 | 40 044 416 (22 050 697–58 023 542) |

| South Africa (2) | 5263 | 2593 | 48.54 (47.21–49.87) | 59 308 690 | 28 788 438 (27 999 633–29 577 244) |

| China (20) | 329 900 | 7026 | 1.73 (1.33–2.14) | 1 439 323 776 | 24 900 301 (19 143 006–30 801 529) |

| Brazil (15) | 119 676 | 5716 | 10.47 (8.84–12.11) | 212 559 417 | 22 254 971 (18 790 252–25 740 945) |

| Mexico (4) | 21 550 | 2516 | 15.41 (7.64–23.17) | 128 932 753 | 19 868 537 (9 850 462–29 873 719) |

| USA (51) | 4 139 485 | 338 082 | 6.45 (5.01–7.88) | 331 002 651 | 21 349 670 (16 583 233–26 083 008) |

| Republic of the Congo (1) | 754 | 149 | 19.76 (16.98–22.79) | 89 561 403 | 17 697 333 (15 207 526–20 411 044) |

| Argentina (2) | 1157 | 509 | 38.36 (35.78–40.94) | 45 195 774 | 17 337 099 (16 171 048–18 503 150) |

| Peru (2) | 2640 | 1138 | 43.49 (41.71–45.28) | 32 971 854 | 14 339 459 (13 752 560–14 929 655) |

| Iran (4) | 16 689 | 2205 | 16.95 (12.91–21.01) | 83 992 949 | 14 236 805 (10 843 490–17 646 919) |

| Colombia (3) | 5814 | 764 | 19.51 (0.01–45.63) | 50 882 891 | 9 927 252 (5 088–23 217 863) |

| Kenya (3) | 13 216 | 1193 | 16.81 (11.23–22.38) | 53 771 296 | 9 038 955 (6 038 517–12 034 016) |

| Ecuador (2) | 992 | 444 | 44.76 (41.66–47.85) | 17 643 054 | 7 897 031 (7 350 096–8 442 201) |

| Côte d'Ivoire (1) | 1687 | 422 | 25.01 (22.96–27.15) | 26 378 274 | 6 597 206 (6 056 452–7 161 701) |

| Italy (19) | 39 712 | 3653 | 10.09 (7.62–12.55) | 60 461 826 | 6 100 598 (4 607 191–7 587 959) |

| Ethiopia (3) | 1 084 | 48 | 4.50 (1.73–7.27) | 114 963 588 | 5 173 361 (1 988 870–8 357 853) |

| England (8) | 369 582 | 18 045 | 6.77 (6.06–7.48) | 67 886 011 | 4 595 883 (4 113 892–5 077 874) |

| Spain (6) | 63 803 | 3385 | 9.79 (5.71–13.88) | 46 754 778 | 4 577 293 (2 669 698–6 489 563) |

| Japan (6) | 11 162 | 176 | 3.47 (1.94–4.99) | 126 476 461 | 4 388 733 (2 453 643–6 311 175) |

| Saudi Arabia (7) | 13 443 | 1611 | 11.24 (6.15–16.33) | 34 813 871 | 3 913 079 (2 141 053–5 685 105) |

| Poland (2) | 6249 | 583 | 9.25 (8.53–9.97) | 37 846 611 | 3 500 812 (3 228 316–3 773 307) |

| South Sudan (1) | 2214 | 494 | 22.31 (20.59–24.11) | 11 193 725 | 2 497 320 (2 304 788–2 698 807) |

| France (14) | 33 114 | 1832 | 5.35 (3.41–7.29) | 65 273 511 | 3 492 132 (2 225 826–4 758 439) |

| Germany (13) | 30 580 | 871 | 3.29 (2.41–4.18) | 83 783 942 | 2 756 491 (2 019 193–3 502 168) |

| Chile (1) | 1244 | 139 | 11.17 (9.48–13.06) | 19 116 201 | 2 135 280 (1 812 216–2 496 576) |

| Austria (4) | 5892 | 879 | 15.59 (2.11–29.08) | 9 006 398 | 1 404 097 (190 034–2 619 060) |

| Switzerland (5) | 520 617 | 56 310 | 10.49 (7.29–13.69) | 8 654 622 | 907 870 (630 921–1 184 817) |

| Sweden (3) | 5191 | 181 | 8.68 (0.76–16.61) | 10 099 265 | 876 616 (76 754–1 677 488) |

| Albania (2) | 1081 | 413 | 26.26 (23.93–28.59) | 2 877 797 | 755 709 (688 657–822 762) |

| Dominican Republic (1) | 12 897 | 703 | 5.45 (5.07–5.86) | 10 847 910 | 591 211 (549 989–635 688) |

| Panama (1) | 255 | 34 | 13.33 (9.41–18.13) | 4 314 767 | 575 158 (406 020–782 267) |

| Zambia (1) | 2614 | 80 | 3.06 (2.43–3.79) | 18 383 955 | 562 549 (446 730–696 752) |

| Netherland (2) | 10 535 | 322 | 2.97 (2.65–3.31) | 17 134 872 | 508 906 (454 074–567 164) |

| Qatar (2) | 115 032 | 19 031 | 16.45 (16.24–16.67) | 2 881 053 | 473 933 (467 883–480 272) |

| Canada (5) | 107 044 | 1051 | 1.14 (0.63–1.64) | 37 742 154 | 430 260 (237 775–618 971) |

| Belgium (2) | 7 301 | 293 | 3.46 (3.04–3.88) | 11 589 623 | 401 001 (352 325–449 677) |

| Libya (1) | 130 | 6 | 4.62 (1.71–9.78) | 6 871 292 | 317 454 (117 499–672 012) |

| Romania (1) | 2115 | 32 | 1.51 (1.04–2.13) | 19 237 691 | 290 489 (200 072–409 763) |

| Scotland (2) | 7635 | 525 | 3.48 (3.07–3.88) | 5 463 300 | 190 123 (167 723–211 976) |

| Portugal (3) | 6508 | 184 | 2.82 (2.42–3.22) | 10 196 709 | 287 547 (246 760–328 334) |

| Australia (1) | 5339 | 38 | 0.71 (0.51–0.98) | 25 499 884 | 181 049 (130 049–249 899) |

| Malaysia (1) | 816 | 3 | 0.37 (0.08–1.07) | 32 365 999 | 119 754 (25 893–346 316) |

| Denmark (5) | 28 751 | 578 | 1.81 (1.16–2.44) | 5 792 202 | 104 839 (67 190–141 330) |

| South Korea (5) | 6017 | 20 | 0.15 (0.01–0.41) | 51 269 185 | 76 904 (5 127–210 204) |

| Croatia (2) | 1799 | 80 | 1.57 (1.01–2.13) | 4 105 267 | 64 453 (41 463–87 442) |

| Hungary (1) | 10 474 | 69 | 0.66 (0.51–0.83) | 9 660 351 | 63 758 (49 238–80 181) |

| Lithuania (1) | 3087 | 58 | 1.88 (1.43–2.42) | 2 722 289 | 51 179 (38 929–65 879) |

| Estonia (1) | 1960 | 75 | 3.83 (3.02–4.77) | 1 326 535 | 50 806 (40 061–63 276) |

| Greece (2) | 9086 | 49 | 0.44 (0.31–0.58) | 10 423 054 | 45 861 (32 311–60 454) |

| Georgia (1) | 1068 | 9 | 0.84 (0.39–1.59) | 3 989 167 | 33 509 (15 558–63 428) |

| Norway (1) | 1173 | 7 | 0.61 (0.24–1.23) | 5 421 241 | 33 070 (13 011–66 681) |

| Luxembourg (1) | 1862 | 35 | 1.88 (1.31–2.61) | 625 978 | 11 768 (8 200–16 338) |

| Andorra (1) | 72 964 | 8 032 | 11.01 (10.78–11.24) | 77 265 | 8507 (8 329–8 658) |

| Palestine (1) | 2455 | 4 | 0.16 (0.04–0.42) | 5 101 414 | 8162 (2 041–21 426) |

| Iceland (1) | 10 198 | 121 | 1.19 (0.99–1.42) | 341 243 | 4061 (3 378–4 846) |

| Jordan (1) | 746 | 0 | 0.02 (0.01–0.11) | 10 203 134 | 2401 (1 020–11 223) |

| Cape Verde (1) | 5381 | 21 | 0.39 (0.24–0.61) | 555 987 | 2168 (1 334–3 392) |

Seroprevalence according to sex, age and population

Of the 275 datasets selected, 114 datasets allowed pooled seroprevalences to be estimated for male and female individuals. Of the 1 142 427 males and 1 260 994 females, 52 831 males (7.73%, 7.19–8.26%) and 46 972 females (7.43%, 6.99–7.88), respectively, had specific serum antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. A higher seroprevalence was observed in males than in females (PR, 1.24; 95% CI 1.22–1.25) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence estimates for the general human population, according to a priori-defined subgroups and socio-demographic geographic parameters

| Variable: subgroup | Number of datasets | Number of people screened (total) | Number of sero-positive people | Pooled seroprevalence, % (95% CI) | Prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 114 | 1 142 427 | 52 831 | 7.73 (7.19 8.26) | 1.24 (1.22–1.25) |

| Female | 114 | 1 260 994 | 46 972 | 7.43 (6.99 7.88) | 1 |

| Age (Model 1) | |||||

| ≤19 | 32 | 123 523 | 10 022 | 9.01 (7.22–10.79) | 3.24 (3.16–3.32) |

| 20–49 | 45 | 1 070 244 | 56 251 | 6.49 (5.51–7.49) | 2.09 (2.06–2.13) |

| 50–64 | 42 | 337 646 | 22 034 | 8.58 (7.31–9.86) | 2.60 (2.55–2.65) |

| ≥65 | 36 | 647 331 | 16 205 | 4.49 (3.68–5.31) | 1 |

| Age (Model 2) | |||||

| 0–9 | 24 | 15 851 | 1257 | 11.53 (9.27–13.79) | 1.75 (1.58–1.93) |

| 10–19 | 29 | 29 587 | 2122 | 9.26 (7.55–10.96) | 1.58 (1.44–1.74) |

| 20–29 | 38 | 92 047 | 7347 | 11.14 (9.54–12.73) | 1.76 (1.62–1.92) |

| 30–39 | 38 | 125 251 | 10 681 | 11.94 (10.18–13.71) | 1.88 (1.73–2.05) |

| 40–49 | 37 | 115 637 | 10 268 | 11.77 (9.91–13.65) | 1.96 (1.80–2.14) |

| 50–59 | 36 | 135 861 | 8466 | 11.05 (9.43–12.66) | 1.37 (1.26–1.50) |

| 60–69 | 35 | 76 390 | 4490 | 10.48 (9.03–11.93) | 1.30 (1.19–1.42) |

| 70–79 | 29 | 30 413 | 1987 | 8.61 (7.13–10.06) | 1.44 (1.31–1.58) |

| +80 | 19 | 11 448 | 517 | 3.46 (2.22–4.71) | 1 |

| Serological method used | |||||

| LFIA | 62 | 941 105 | 44 101 | 8.42 (7.71–9.12) | 3.33 (3.09–3.58) |

| ELISA | 104 | 372 088 | 48 820 | 12.12 (10.78–13.46) | 9.33 (8.67–10.03) |

| CLIA | 86 | 4 959 287 | 421 866 | 8.45 (7.39–9.51) | 6.05 (5.62–6.50) |

| Virus neutralization assay | 12 | 51 849 | 729 | 0.94 (0.63–1.26) | 1 |

| Others (IFA, MIA, MIA, FC, SERA, CAM) | 11 | 43 405 | 3 891 | 8.15 (5.24–11.07) | 6.37 (5.89, 6.89) |

| Type of procedure | |||||

| Commercial kit | 231 | 6 241 162 | 513 265 | 10.01 (9.47–10.54) | 1.69 (1.65–1.73) |

| In-house | 44 | 126 572 | 6142 | 6.36 (5.56–7.17) | 1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 29 | 1 408 614 | 34 505 | 1.92 (1.91–1.94) | 1 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 29 | 42 245 | 2896 | 4.05 (3.86–4.23) | 2.79 (2.69–2.90) |

| Brown/Hispanic | 24 | 88 283 | 4612 | 3.32 (3.21–3.44) | 2.13 (2.06–2.19) |

| Multiple race/Asian/Other/Unknown | 27 | 78 539 | 3220 | 2.69 (2.57–2.81) | 1.67 (1.63–1.73) |

| Income | |||||

| Low | 5 | 4052 | 691 | 11.21 (1.97–20.45) | 3.26 (3.04–3.49) |

| Lower middle | 25 | 180 484 | 34 449 | 21.61 (17.57–25.65) | 3.64 (3.59–3.70) |

| Upper middle | 66 | 533 152 | 27 886 | 11.93 (11.42–12.45) | 1.54 (1.52–1.56) |

| High | 179 | 5 650 046 | 456 381 | 6.54 (5.87–7.22) | 1 |

| Human development index (HDI) | |||||

| Low | 8 | 6 037 | 1 206 | 18.03 (10.04–26.02) | 4.41 (4.19–4.64) |

| Medium | 20 | 170 660 | 33 909 | 22.56 (18.39–26.73) | 4.38 (4.32–4.45) |

| High | 58 | 519 832 | 23 528 | 9.88 (9.38–10.37) | 1.79 (1.77–1.81) |

| Very high | 189 | 5 671 205 | 460 764 | 7.27 (6.61–7.93) | 1 |

| Risk of bias | |||||

| Low | 84 | 1 035 414 | 63 713 | 6.56 (5.78–7.34) | 1 |

| Moderate | 113 | 2 467 099 | 150 880 | 10.31 (9.59–11.02) | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

| High | 78 | 2 865 221 | 304 814 | 10.39 (9.17–11.62) | 1.72 (1.71–1.74) |

LFIA, lateral flow immunoassay; CLIA, chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay; IFA, immunofluorescence assay; VN, virus neutralization; MIA, microsphere immunoassay; FC, flow cytometry assay; SERA, serum epitope repertoire analysis; CAM, coronavirus antigen microarray.

Seroprevalence data were available for 45 and 38 datasets for subgroup analysis of age groups using models 1 and 2, respectively. Using model 1, subgroup analyses revealed pooled seroprevalences of 9.01% (7.22–10.79%), 6.49% (5.51–7.49%), 8.58% (7.31–9.86%) and 4.49% (3.68–5.31%) for people of ≤19, 20–49, 50–64 and ≥65 years of age, respectively (Table 2). Using model 2, the highest and lowest seroprevalence estimates were estimated for people of 30–39 (11.94%, 10.18–13.71%) and >80 (3.46%, 2.22–4.71%) years of age, respectively (Table 3).

Serological assays and seroprevalences

A range of serological assays were used in studies linked to the 275 datasets. ELISA was linked to 104 datasets, whereas CLIA, rapid LFIA, virus neutralization assay and other serological methods (e.g. immunofluorescence assay, microsphere immunoassay, flow cytometry assay, serum epitope repertoire analysis and coronavirus antigen microarray) were linked to 86, 62, 12 and 11 datasets, respectively. Commercial kits and in-house serological methods were associated with 231 and 44 datasets, respectively (Table S2 and Table 3). Subgroup analysis showed that the highest and lowest seroprevalences were estimated using ELISA (12.12%, 10.78–13.46%) and virus neutralization (0.94%, 0.63–1.26%), respectively. Seroprevalences estimated using LFIA (8.42%, 7.71–9.12%), CLIA (8.45%, 7.39–9.51%) and other serological methods (8.15%, 5.24–11.07%) were almost similar. Moreover, subgroup analysis indicated pooled seroprevalences of 10.01% (9.47–10.54%) using commercial kits and 6.36% (5.56–7.17%) for in-house assays (Table 3).

Seroprevalence in relation to ethnicity

Seroprevalence data associated with ethnicity were available from 29 datasets. Subgroup analysis of these ethnicity data revealed pooled seroprevalences of 4.05% (3.86–4.23%), 3.32% (3.21–3.44%), 2.69% (2.57–2.81%) and 1.92% (1.91–1.94%) in people of Black, Hispanic, Asian/other and White ethnic backgrounds, respectively (Table 2). People of Black (PR 2.78, 2.68–2.88), Hispanic (PR 2.05, 1.99–2.11) and Asian/other minority ethnicities (PR 1.64, 1.58–1.69) showed a significantly higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection than White people (Table 3).

Relationship between seroprevalence and socio-demographic variables

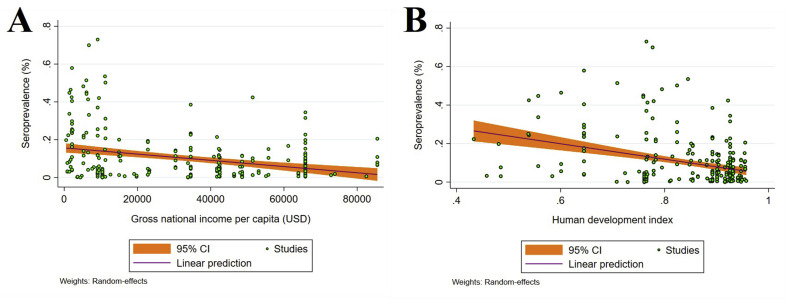

Subgroup analysis according to income level showed that the highest and lowest seroprevalences were in countries with lower middle (21.61%, 17.57–25.65%) and high 6.54% (5.87–7.22%) income levels, respectively (Table 3). Subgroup analysis (Table 2) according to HDI level indicated that countries with medium (22.56%, 18.39–26.73%) and low (18.03%, 10.04–26.02%) HDI had higher seroprevalences than countries with high (9.88%, 9.38–10.37%) and very high (7.27%, 6.61–7.93%) HDI. Random-effects meta-regression analyses showed a decreasing trend in seroprevalence with higher income levels (coefficient (C) = –1.65 × 10−6; p < 0.001), and HDI (C = –0.4001; p < 0.001) (Figs. 3 A,B).

Fig. 3.

Ecological random effects meta-regression analyses of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the general population in relation to: (A) a country's income level (a statistically significant downward trend in seroprevalence in countries with higher income levels). (B) Human development index (HDI) (a statistically significant downward trend in seroprevalence in higher HDI countries).

Seroprevalence in relation to risk of bias

Critical appraisal using the JBI showed that 86 datasets had a low risk of bias (score 7–9/9), 113 datasets had a moderate (4–6/9) and 78 studies had a high risk of bias (≤3/9). Moreover, the seroprevalences for studies with a low, moderate, and high risk of biases were 6.56% (5.78–7.34%), 10.31% (9.59–11.02%) and 10.39% (9.17–11.62%), respectively (Table 3).

Relationship between seroprevalence and time

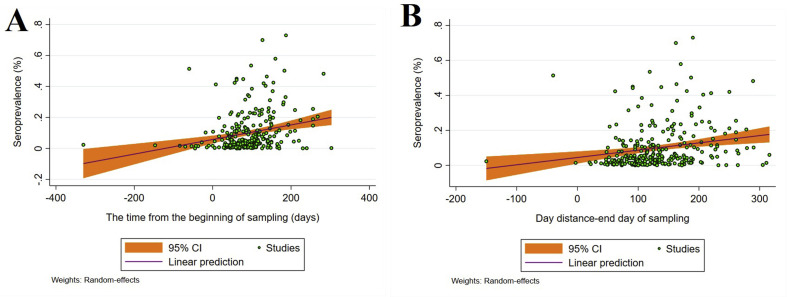

With reference to the start date of a COVID-19 epidemic in a country (in months), subgroup analysis (Table S4) showed seroprevalences of 1.73% (1.33–2.14%), 8.65% (7.79–9.51%), 11.04% (10.02–12.06%) and 14.15% (12.36–15.93%) in December 2019, January 2020, February 2020 and March 2020, respectively. Subgroup analysis of data at the beginning date of sampling showed an increasing trend of seroprevalence estimates on a monthly basis (Table S4). Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were also conducted to explore SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence over time—from the beginning of the pandemic to the first and last times of sampling/testing in individual studies. The results indicated increasing seroprevalence estimates over time, as the highest seroprevalences were recorded 7–10 months after the epidemic commenced in a particular country (Table S4). Random-effects meta-regression analysis showed a significant, increasing trend in seroprevalence in a country from the beginning of a COVID-19 epidemic to the first (C = 0.0013; p < 0.001) and to the last (C = 0.0004; p < 0.001) day of sampling (i.e. serum collection) (Figs. 4 A,B).

Fig. 4.

Random effects meta-regression analysis of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in the general human population in relation to time, showing the significant, upward trend in seroprevalence from the beginning of a COVID-19 epidemic to the first (A) and to the last (B) day of sampling (i.e. serum collection).

Association between seroprevalence and confirmed COVID-19 cases and deaths

We counted the numbers of confirmed cases and deaths in individual countries in WHO situation reports [31]. Subgroup analyses of the data showed that the lowest seroprevalences were observed when the confirmed cases (4.66%, 3.59–5.73%) and total deaths (6.38%, 5.36–7.41%) were lower than 10 000 and 1000 cases, respectively (Table S5). Moreover, the highest seroprevalences were observed when the confirmed cases (19.11%, 15.77–22.44%) and total deaths (14.17%, 12.28–16.06%) were between 500 000–1 000 000 and 20 000–40 000 cases, respectively (Table S5). Meta-regression analyses indicated a non-significant, increasing trend in the number of confirmed cases (C = 7.09 × 10−9; p 0.08) with increasing seroprevalence. Similarly, a non-significant, increasing trend was found in relation to the total number of deaths (C = 1.33 × 10−7; p = 0.36) (Fig. S2A,B).

Discussion

This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive update on the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence regionally and internationally. The pooled global seroprevalence was estimated at 9.47% (95% CI 8.99–9.95%), equating to ∼738 million (700–775 million) people worldwide, which is relatively consistent with previous seroprevalence studies [13,14], bearing in mind that the true prevalence of infection appears to be 6–11 times greater than the number of confirmed cases reported officially by countries [[32], [33], [34]]. The seroprevalence estimates here varied considerably between SDG regions and sub-regions, with the highest SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences in southern Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa. Living in overcrowded conditions, higher rates of co-morbidities and an inadequate or lack of access to medical care likely increase the vulnerability of people in developing countries to SARS-CoV-2 and other respiratory infections [35]. In addition, poor infrastructure and poverty render preventive measures (including detection of people with active infection, quarantine and reducing public transport during the daytime) more difficult [35,36].

In accord with other studies [5,13,14], the present results showed a higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in males than in females, which could be attributed to more outdoor activities in remote areas and community exposure for males, particularly in developing countries [37]. Our findings also indicate significant differences in SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence between age groups, with seroprevalence decreasing with age for people older than 65 years. In accordance with a previous study [5], people of <19 years (children and adolescents) had similar seroprevalences to individuals aged 20–64 years, in contrast to other meta-analyses of global SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence [13,14], indicating lower seroprevalence estimates for people of <19 years of age. A possible reason for this difference could be the exclusion of high-risk populations in the present study. Children are socially active and have more physical contact with others, especially when playing with other children or families. Thus, mandating social distancing is more difficult for them. Our results suggest that children might have the same level of exposure to infection as adults, but are less likely to develop symptoms and to be admitted to hospital [21,38,39]. A higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence rate in adults of 20–64 years of age than in older people could be explained by a greater involvement in community activities [14], [40], [41], [42].

Consistent with some previous studies [5,13,[43], [44], [45]], minority ethnic groups are at a high risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection, which is supported by findings from the REACT-2 and OpenSAFELY studies in the UK, showing higher levels of SARS-CoV-2 serum antibodies and hospitalization in minority groups than people of White ethnicity [43,46]. Possible explanations might include discrimination or difficulties in accessing healthcare, housing, education and financial status; communication and language barriers; cultural practices; lack of health insurance; more ethnic minority groups employed in essential work settings, such as healthcare facilities, farms, factories, grocery stores and public transport; and living in large families and/or overcrowded conditions [5].

The SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalences estimated herein may not be entirely accurate because of limitations or characteristics of the studies included in this investigation. First, a notable number of studies did not apply rigorous (e.g. multistage cluster or stratified) sampling strategies and did not always include a representative population. Second, several serological assays with differing test performances (specificities and sensitivities) and cut-off values were used to test samples. However, few studies have independently validated the specificity and sensitivity of the used diagnostic kits prior to the serological testing of large numbers of serum samples. Despite WHO recommendations, the seroprevalence estimates reported in many studies included did not adjust for the demographic structure of the target population. Finally, as it is impractical, we did not perform inverse probability weighting using population weights to adjust for unequal probability of sampling [47,48]. These limitations can make comparisons between/among studies challenging, and might explain heterogeneity among studies. Other limitations (including different and time-varying sensitivities and specificities of serological methods; missing studies published in un-indexed, local journals; a lack of data for two-thirds of countries of the world) may also have an effect and has been discussed elsewhere [5,13,14].

Although not accounted for here, sero-reversion can lead to a classification challenge (infected vs. non-infected), a distortion of epidemiological estimates and/or possible shifts in susceptibility of people to infection in subsequent ‘waves’ of COVID-19. It has been shown that infection-blocking immunity wanes rapidly, but that disease-reducing immunity is long-lived [49]. A real-time assessment of community transmission (REACT-2) study involving 365 104 people in the UK, and conducted over three phases of testing, showed that anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunity waned over time; serum antibody prevalence declined from 6% to 4.4% between 20 June and 28 September 2020 [50]. Another point is that the present study was conducted before the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants/lineages, such as B.1.352, P.1, B.1.17 and B.1.617; infections with new variants are likely to have spread in recent months and require rigorous monitoring, as some (e.g. B.1.617) are markedly more transmissible (60%) than the ‘original virus’ [51]. Moreover, recent analysis by IHME [4] estimated that 32% of people globally were infected since 23 August 2021. If we consider that there are ten undetected people per confirmed case, ∼2140 million individuals (∼27.5%) of the world's population have been infected since this date. Our lower estimate (27.5% vs. 32%) might be explained by a higher community transmission of new variants (delta and lambda) from December 2020 to August 2021, particularly in countries such as Brazil, India, Iran and Peru [51].

The present, updated meta-analysis reveals a higher SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in countries with low- and lower middle-income levels, emphasizing the need to accelerate vaccination ‘roll-out’ in developing countries. The high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Black, Hispanic, Asian and minority ethnicities emphasizes that vaccine allocation to these groups of people needs to be a priority. For future seroprevalence investigations, we recommend improved study designs, consistent with WHO protocols [8], which would reduce heterogeneity among investigations, and allow for enhanced seroprevalence estimates, meta-analyses, interpretations and policy decisions. Given the pace of work on COVID-19 and the rapid emergence and spread of the delta, kappa and lambda variants of SARS-CoV-2, we refer to recent seroprevalence surveys (see Table S6), published while this paper was under review (i.e. 30 March 2021 to 26 August 2021). Clearly, seroprevalence rates have increased markedly in countries including India (54.2%), Kenya (44.2%), Poland (35.5%), Jordan (34.2%), Greece (26.3%), Brazil (14.8%), United States (14.5%), Portugal (13.1%), Croatia (11.1%) and England (9.8%).

Transparency declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study was supported by the Health Research Institute at the Babol University of Medical Sciences, Babol, Iran (IR.MUBABOL.REC.1399.304).

Author contributions

A.R., R.B.G and P.J.H conceived the study. A.R., A.F., A.S., M.B and S.E. conducted the searches and collected data. A.R., M.S., S.M.R. and M.A.M analysed the data sets and interpreted the results. A.R., A.H.M, M.N, M.R.E., P.J.H and R.B.G drafted and edited the manuscript. All authors commented on, or edited, drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Malihe Nourollahpour Shiadeh for critically reviewing the earlier version of the manuscript.

Editor: J. Rodriguez-Baño

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Lee W.S., Wheatley A.K., Kent S.J., DeKosky B.J. Antibody-dependent enhancement and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapies. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1185–1191. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00789-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartley D.M., Perencevich E.N. Public health interventions for COVID-19: emerging evidence and implications for an evolving public health crisis. JAMA. 2020;323:1908–1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update-24 August 202. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19-24-august-2021 Available from:

- 4.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) IHME, University of Washington; Seattle, USA: 2021. COVID-19 results briefing:[global]https://www.healthdata.org/covid/updates Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rostami A., Sepidarkish M., Leeflang M., Riahi S.M., Shiadeh M.N., Esfandyari S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pollán M., Pérez-Gómez B., Pastor-Barriuso R., Oteo J., Hernán M.A., Pérez-Olmeda M., et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Spain (ENE-COVID): a nationwide, population-based seroepidemiological study. Lancet. 2020;396:535–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31483-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buitrago-Garcia D., Egli-Gany D., Counotte M.J., Hossmann S., Imeri H., Ipekci A.M., et al. Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) 17 March 2020. Population-based age-stratified seroepidemiological investigation protocol for COVID-19 virus infection.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331656 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 9.Figueiredo-Campos P., Blankenhaus B., Mota C., Gomes A., Serrano M., Ariotti S., et al. Seroprevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in COVID-19 patients and healthy volunteers up to 6 months post disease onset. Eur J Immunol. 2020;50:2025–2040. doi: 10.1002/eji.202048970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer A.S., Jones F.K., Nodoushani A., Kelly M., Becker M., Slater D., et al. Persistence and decay of human antibody responses to the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isho B., Abe K.T., Zuo M., Jamal A.J., Rathod B., Wang J.H., et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abe5511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimoto A.B., Yildirim I., Keskinocak P. Significance of SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody testing during COVID-19 vaccine allocation. Vaccine. 2021;39:5055–5063. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.06.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobrovitz N., Arora R.K., Cao C., Boucher E., Liu M., Rahim H., et al. Global seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X., Chen Z., Azman A.S., Deng X., Chen X., Lu W., et al. Serological evidence of human infection with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e598–e609. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00026-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D., Shamseer L., Clarke M., Ghersi D., Liberati A., Petticrew M., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee Y.-L., Liao C.-H., Liu P.-Y., Cheng C.-Y., Chung M.-Y., Liu C.-E., et al. Dynamics of anti-SARS-Cov-2 IgM and IgG antibodies among COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.019. e55–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lumley S.F., Wei J., O'Donnell D., Stoesser N., Matthews P., Howarth A., et al. The duration, dynamics and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in individual healthcare workers. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e699–709. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The sustainable development goals (SDGs) report 2019. Regional groupings. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/regional-groups/ Available from:

- 19.World Bank Group database . 2019. Gross national income per capita.https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GNIPC.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 20.United Nations Development Program Human development index. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/HDI Available from:

- 21.World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update -29 December 2020) https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-29-december-2020 Available at:

- 22.United Nations Total population (both sexes combined) by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950–2100 (thousands) https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population/ Available from:

- 23.Munn Z., Moola S., Lisy K., Riitano D., Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman M.F., Tukey J.W. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 25.DerSimonian R., Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trial. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turner R.M., Davey J., Clarke M.J., Thompson S.G., Higgins J.P. Predicting the extent of heterogeneity in meta-analysis, using empirical data from the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:818–827. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellison A.M. Bayesian inference in ecology. Ecol Lett. 2004;7:509–520. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harbord R.M., Higgins J.P. Meta-regression in Stata. Stata J. 2008;8:493–519. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hunter J.P., Saratzis A., Sutton A.J., Boucher R.H., Sayers R.D., Bown M.J. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization (WHO) COVID-19 situation reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports Available from:

- 32.Menachemi N., Yiannoutsos C.T., Dixon B.E., Duszynski T.J., Fadel W.F., Wools-Kaloustian K.K., et al. Population point prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection based on a statewide random sample—Indiana, April 25–29, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:960–964. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6929e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phipps S.J., Grafton R.Q., Kompas T. Robust estimates of the true (population) infection rate for COVID-19: a backcasting approach. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7:200909. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Byambasuren O., Dobler C.C., Bell K., Rojas D.P., Clark J., McLaws M.-L., et al. Comparison of seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections with cumulative and imputed COVID-19 cases: systematic review. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdel-Moneim A.S. Community mitigation during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: mission impossible in developing countries. Popul Health Manag. 2021;24:6–7. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray C.J., Lopez A.D., Chin B., Feehan D., Hill K.H. Estimation of potential global pandemic influenza mortality on the basis of vital registry data from the 1918–20 pandemic: a quantitative analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:2211–2218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muurlink O.T., Taylor-Robinson A.W. COVID-19: cultural predictors of gender differences in global prevalence patterns. Front Public Health. 2020;8:174. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee B., Raszka W.V. COVID-19 transmission and children: the child is not to blame. Pediatr. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-004879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mustafa N.M., Selim L.A. Characterisation of COVID-19 pandemic in paediatric age group: a systematic review. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104395. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ludvigsson J.F. Children are unlikely to be the main drivers of the COVID-19 pandemic – a systematic review. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109:1525–1530. doi: 10.1111/apa.15371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cortis D. On determining the age distribution of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:202. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies N.G., Klepac P., Liu Y., Prem K., Jit M., Eggo R.M. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat Med. 2020;26:1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathur R., Rentsch C.T., Morton C.E., Hulme W.J., Schultze A., MacKenna B., et al. Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and death in 17 million adults in England: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet. 2021;397:1711–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00634-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goyal M.K., Simpson J.N., Boyle M.D., Badolato G.M., Delaney M., McCarter R., et al. Racial and/or ethnic and socioeconomic disparities of SARS-CoV-2 infection among children. Pediatr. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-009951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vahidy F.S., Nicolas J.C., Meeks J.R., Khan O., Pan A., Jones S.L., et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: analysis of a COVID-19 observational registry for a diverse US metropolitan population. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward H., Atchison C., Whitaker M., Ainslie K.E., Elliott J., Okell L., et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in England following the first peak of the pandemic. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21237-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mansournia M.A., Altman D.G. Inverse probability weighting. BMJ. 2016;352:i189. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mansournia M.A., Nazemipour M., Naimi A.I., Collins G.S., Campbell M.J. Reflection on modern methods: demystifying robust standard errors for epidemiologists. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50:346–351. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lavine J.S., Bjornstad O.N., Antia R. Immunological characteristics govern the transition of COVID-19 to endemicity. Science. 2021;371:741–745. doi: 10.1126/science.abe6522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ward H., Cooke G., Atchison C.J., Whitaker M., Elliott J., Moshe M., et al. Prevalence of antibody positivity to SARS-CoV-2 following the first peakof infection in England: Serial cross-sectional studies of 365,000 adults. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2020;4:100098. doi: 10.1101/2020.10.26.20219725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) IHME, University of Washington; Seattle, USA: May 5, 2021. COVID-19 results briefing: global.http://www.healthdata.org/special-analysis/estimation-excess-mortality-due-covid-19-and-scalars-reported-covid-19-deaths Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.