Abstract

Purpose:

While there is concern about degenerative tissue effects of exposure to space radiation during deep-space missions, there are no pharmacological countermeasures against these adverse effects. γ-Tocotrienol (GT3) is a natural form of vitamin E that has anti-oxidant properties, modifies cholesterol metabolism, and has anti-inflammatory and endothelial cell protective properties. The purpose of this study was to test whether GT3 could mitigate cardiovascular effects of oxygen ion (16O) irradiation in a mouse model.

Materials and methods:

Male C57BL/6J mice were exposed to whole-body 16O (600 MeV/n) irradiation (0.26–0.33 Gy/min) at doses of 0 or 0.25 Gy at 6 months of age and were followed up to 9 months after irradiation. Animals were administered GT3 (50 mg/kg/day s.c.) or vehicle, on Monday – Friday starting on day 3 after irradiation for a total of 16 administrations. Ultrasonography was used to measure in vivo cardiac function and blood flow parameters. Cardiac tissue remodeling and inflammatory infiltration were assessed with histology and immunoblot analysis at 2 weeks, 3 and 9 months after radiation.

Results:

GT3 mitigated the effects of 16O radiation on cardiac function, the expression of a collagen type III peptide, and markers of mast cells, T-cells and monocytes/macrophages in the left ventricle.

Conclusions:

GT3 may be a potential countermeasure against late degenerative tissue effects of high-linear energy transfer radiation in the heart.

Keywords: high-LET radiation, cardiovascular system, degenerative tissue effects, γ-tocotrienol, radiation countermeasure

1. Introduction

Studies of Japanese atomic bomb survivors [1, 2] and other human populations exposed to low doses of ionizing radiation to a large part of the body [3–5] have shown an increased rate in cardiovascular disease. This has raised the concern about potential degenerative tissue effects in the cardiovascular system due to low-dose exposure to ionizing radiation during deep space travel [6–8]. Since the biological properties of the high-Z high-energy (HZE) particle radiation in deep space are different from those of the low-linear energy transfer (LET) radiation exposures of human populations described above, research is needed to identify the risk of cardiovascular disease from exposure to space radiation.

Currently, there is minimal opportunity to obtain data on biological effects of HZE particles from human subjects, which makes the determination of the biological response almost exclusively dependent on animal models [9–14]. Studies in rodent models of HZE radiation exposure have shown alterations in cardiac function and cardiac tissue remodeling [15, 16], indicators of inflammation in the heart [17] and vascular stiffness and endothelial dysfunction [18].

Since astronauts in deep space will spend most of their time inside a space craft, it is important that research models for the assessment of health effects of deep space travel mimic the radiation environment that may be found inside the space craft as opposed to free space. Fragmentation of heavy ions in the wall of a space craft will lead to a radiation environment inside the craft that, for a large part, consists of ions of Z ≤10 [19]. Therefore, we previously performed a study in which adult male C57BL/6J mice were exposed to protons (150 MeV) or oxygen ions (16O, 600 MeV/n) [20]. We found that 16O at doses from 0.05 to 1 Gy caused small changes in cardiac function and induced the expression of left ventricular collagen type III and left ventricular protein levels of mast cell tryptase, CD2 (marker of T-cells) and CD68 (monocytes/macrophages). In the current project, we used the same mouse model to test whether a radiation countermeasure may mitigate these effects of 16O exposure.

γ-Tocotrienol (GT3) is a natural form of vitamin E that has long been known for its properties as protector against the acute radiation syndrome from exposure to low-LET radiation [21–23]. While GT3 has anti-oxidant properties similar to those of the most common form of vitamin E, α-tocopherol [24, 25], GT3 has additional benefits. It is a potent inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis [26, 27]. Moreover, GT3 accumulates in endothelial cells to at least 30-fold higher levels than α-tocopherol and modulates larger numbers of genes in these cells [28, 29]. We have previously shown that GT3 exerts its radiation protection at least in part by inhibiting the cholesterol synthesis pathway [21] and by reducing endothelial dysfunction [30]. Altogether, we hypothesize that GT3 has beneficial effects in the cardiovascular response to ionizing radiation and tested whether administration of GT3 would alter the effects of a single dose of 16O (600 MeV/n, 0.25 Gy) on cardiac function and structure in male C57BL/6J mice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal housing and radiation

All animal procedures within this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL). Male C57BL/6J mice (n=140 total; Jackson Laboratory; Bar Harbor, ME) were housed at UAMS, 5 per cage on a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle and were administered standard rodent chow low in soy (2020X, Harlan Laboratories) and water ad libitum. The cages were randomly divided into 4 experimental groups: 16O or sham-irradiation, each with vehicle or GT3 administration after irradiation (n=35 mice per group).

At 6 months of age, all mice were transported to Brookhaven National Laboratory (BNL; Upton, NY) by overnight air and housed on a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle, 2020X diet and water ad libitum. After 1 week acclimatization to BNL, mice were exposed to whole-body 16O irradiation at the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory (NSRL). Since in a previous study we had tested the effects of 16O in a dose range of 0.05 – 1 Gy [20], we selected 0.25 Gy as an intermediate dose for the current study. For this purpose, mice were individually positioned in a clear Lucite cube, placed within the NSRL beam line and were exposed to 16O (600 MeV/n) at a dose rate of 0.26−0.33 Gy/min. Radiation dosimetry was performed by the NSRL physics team. Sham-irradiated mice were also transported to NSRL and placed in the clear Lucite cubes for about 1 minute (the same time as the irradiated mice), but were not exposed to 16O. Two days after irradiation or sham-treatment, mice were returned to UAMS. Within each experimental group, 10 mice were scheduled for sacrifice at 2 weeks after radiation, 10 mice at the 3 months-time point, and 15 mice at 9 months.

2.2. GT3 administration and plasma measurement

GT3 was separated from DeltaGold® using flash column with silica gel (230–400 mesh) as the stationary phase. Gradient elution was performed with ethyl acetate and hexanes (20/1 to 10/1). Purity of GT3 (> 95%) was determined with gas chromatography- and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry.

Subcutaneous administration of GT3 (50 mg/kg bodyweight once a day) or vehicle (saline, with 5% Tween 80) started on day 3 after irradiation (a Friday) and continued on Monday – Friday for a total of 16 administrations. Plasma samples of mice sacrificed 2 weeks after irradiation, as described under the heading Blood and tissue collection, were used to assess plasma concentration of GT3 using high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC).

2.3. High-resolution ultrasonography

Ultrasonography was performed at 3, 5, 7 and 9 months after irradiation (n=15 mice per group) by one investigator who was blinded to the treatment groups. The day before ultrasonography, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and hair was removed from the thorax and abdomen using a depilatory cream. On the day of ultrasonography, mice were anesthetized with 1.5–2% isoflurane and placed supine on a heated platform that monitors respiration rate and ECG. The mice were scanned with a Vevo® 2100 imaging system (VisualSonics, Inc.) with a MS400 (18–38 MHz) transducer. Echocardiographs were obtained in the short axis M-mode at the mid-left ventricular level.

Pulsed-wave Doppler was used to determine abdominal aorta blood flow as an indicator of both cardiac and vascular function. For this purpose, the probe was placed in the transverse axis, immediately anterior of the renal artery branch point.

The Vevo® LAB cardiac software package was used to obtain ultrasonography parameters from three M-mode scans per animal, and the vascular package was used to assess blood flow parameters from three consecutive beats per abdominal aorta Pulsed-wave Doppler scan, in up to three scans per animal. A description of all parameters obtained from ultrasonography is provided in Supplemental Materials, Table S1.

2.4. Blood and tissue collection

Two weeks, 3 months, and 9 months after irradiation, mice were weighed in preparation for blood and tissue collection. Calipers were used to measure tibia length as an additional indicator of body size. Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane, and a modified infusion set (27G with shortened tubing) was used to inject a single dose of heparin (30−40 U/kg) into the abdominal vena cava. Without changing the position of the infusion set, a blood sample was drawn and transferred into an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) coated tube. Immediately after blood collection, the heart was collected, rinsed, weighed and cut longitudinally. One half of the heart was fixed in 5% formalin for 24 hours and embedded in paraffin. For the other half, a specimen of left ventricle was processed as described under the heading Electron microscopy. The remainder of the heart was divided into atria, right ventricle, and 4 samples of left ventricle and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

2.5. Blood chemistry values

Blood samples collected at 9 months were used to measure blood chemistry values with an i-STAT blood analyzer and CHEM8+ cartridges (Abbott Labs, Lake Bluff, IL), and blood glucose levels were determined by using FreeStyle Precision Neo blood glucose monitoring system and test strips (Abbott Laboratories, Lake Bluff, IL). Values were determined for blood anion gap (ANGAP), blood concentration of urea nitrogen (BUN), Cl, blood concentration of creatine (CREA), glucose, hemoglobin (HB), hematocrit (HCT), K, Na, concentration of free ionized calcium (ICA), and blood concentration of carbon dioxide (TCO2).

2.6. Histology

For the assessment of cardiac collagen deposition, 5 μm longitudinal sections of heart were rehydrated and incubated with Sirius Red supplemented with Fast Green. Sections were scanned with a ScanScope CS2 slide scanner and analyzed with ImageScope 12 software (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). The relative tissue area of collagens was calculated as the red-stained area expressed as a percentage of the total tissue area of each section.

2.7. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was used to identify cluster of differentiation (CD)45-positive cells. Left ventricle sections were rehydrated and antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections in Target Retrieval buffer (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) at 120°C in a decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA) for 20 minutes, cooling for 45 minutes in the retrieval buffer, and then were rinsed in distilled water. Immediately after, sections were then incubated in 1% H2O2 in methanol to block endogenous peroxidase, followed by 10% normal serum in 3% dry milk powder and 0.2% bovine serum albumin. Sections were incubated overnight with rat anti-CD45 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Crus, CA), followed by biotinylated goat anti-rat IgG (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and an avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 45 minutes. Antibodies were visualized with 0.5 mg/mL 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (Sigma-Aldrich) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Stained sections were examined with an Axioskop transmitted-light microscope (Carl Zeiss), and CD45-positive cells were counted in 10 optical areas per section. Cells were counted by an individual who was aware of the animal identification numbers but not the treatment groups. The number of CD-positive cells were divided by the total area of the 10 views.

2.8. Electron microscopy

Tissue specimens of left ventricle were fixed and processed for electron microscopy using a method described by Cocchiaro et al. [31]. Sections were analyzed with a Tecnai F20 200 keV electron microscope (FEI Company, Hillsboro OR).

2.9. Immunoblot analysis

To determine protein expression indicative of cardiac remodeling and inflammatory infiltration, immunoblot analysis was performed. A Potter-Elvehjem mechanical compact stirrer (BDC2002, Caframo Lab Solutions, Georgian Bluffs, Ontario) was used to homogenize left ventricular samples in a 1% Triton-X100 RIPA buffer containing protease (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) and phosphatase inhibitors (1:100, Sigma-Aldrich). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and 30 μg protein was added to a 2x Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol (5%). Gel electrophoresis was performed, and proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane.

The following antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and used to determine protein content: Collagen type III (1:1,000), mast cell tryptase (1:20,000), CD2 (T-lymphocytes; 1:3,000), and CD-68 (monocytes/macrophages; 1:1,000). Immunoblots were imaged with an AlphaImager® gel documentation system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA), protein bands quantified by densitometry through use of publically available ImageJ software and expressed relative to GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:20,000).

2.10. Statistical analyses

Ultrasonography measured 18 heart function parameters from M-mode and Pulsed-wave Doppler recordings of the heart and 4 parameters from pulsed-wave Doppler of the abdominal aorta, as listed in Supplementary Materials, Table S1. The measures of each these parameter at a given time point were fitted with an analysis of covariance comprised of radiation (0 or 0.25 Gy), GT3 (GT3 or vehicle), and their interaction as factors. Bodyweight at euthanasia and heart rate during ultrasonography recording were included as covariates. Others have previously seen that measures of ultrasonography parameters may depend on heart rate [32] and bodyweight [33]. For each parameter, we evaluated whether the assumptions of normal errors and equal variances among independent groups were reasonable. Normal assumptions were reasonable for all parameters. However, Levene’s test for homogeneous variance indicated that for several parameters, variances were not equal among the groups. We thus allowed the variances among independent groups to differ for those parameters having heterogeneous variances. Error degrees of freedom were estimated with Kenward-Roger’s method [34]. Comparisons of groups were conducted with t-tests within the analysis of covariance framework; the group means were computed at the mean values of heart rate and bodyweight. Analyses of all other parameters were the same as for the analysis of covariance described above, except the covariates of heart rate and bodyweight were not included. All tests were conducted at a 0.05 significance level. Regarding multiple comparisons, rather than adjusting the significance level, the positive False Discovery Rate (pFDR) was computed for all significant results found [35]. The ANCOVAs and ANOVAs were conducted with the MIXED procedure in SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (SAS System for Windows, SAS Institute, Inc.). The pFDR was computed in R version 3.6.2 with custom code. Statistical code and data for analyses reported herein is available on request.

When reporting summary statistics (i.e., means ± standard deviation (SD)), the reported means and SDs were estimated from the statistical models since these are the values on which inferences are based. Parameters for which the assumption of homogeneous variance across groups was reasonable, the pooled SD is reported; otherwise the SDs were estimated (within the model) for each group.

Sample size considerations.

In general, the planned sample sizes for each of the four groups defined by the combinations of radiation dose and GT3 administration at a specific post-irradiation time point were n = 6, 10, and 15, depending on the parameter under investigation. With these sample sizes, main effects of size 1.20 SD (n=6), 0.92 SD (n=10), and 0.74 SD (n=15) were detectable with 0.80 power on a 0.05 significance level test. With the same assumptions, simple effects of size 1.71 SD (n=6), 1.29 SD (n=10), and 1.05 SD (n=15) were detectable, and interaction effects of size 2.41 SD (n=6), 1.84 SD (n=10), and 1.48 SD (n=15) were detectable.

3. Results

3.1. Animal characteristics

Plasma GT3 concentrations were measured in mice sacrificed at 2 weeks after irradiation, when GT3 administrations were still ongoing. Plasma GT3 concentrations were 0.47 ± 0.15 μM (n=5 mice) in the sham-irradiated animals and 0.69 ± 0.16 μM (n=5 mice) in the irradiated animals. These plasma levels were not significantly different.

Across all time points examined, there was no evidence of differences in bodyweight among the four groups (Supplemental Materials, Table S2).

In blood chemistry values measured 9 months after total body 16O exposure increased Cl and decreased ICA, Na, TCO2, Glucose, and BUN compared to sham animals. GT3 mitigated these 16O induced changes in Cl, ICA, Na, and TCO2. For BUN, levels in GT3-treated mice exposed to 16O radiation were also decreased from their sham irradiated peers. GT3 also demonstrated a significant increase in HB and HCT in irradiated mice (Supplemental Materials, Table S3).

3.2. In vivo cardiac function

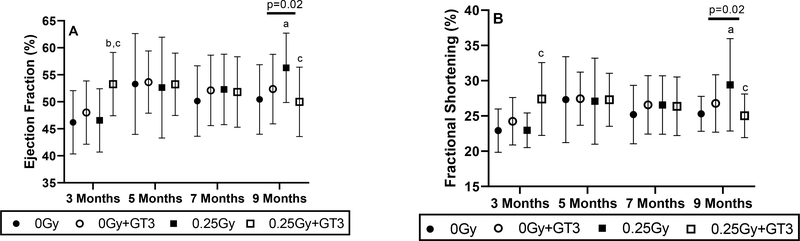

Ultrasonography provided 18 measures related to cardiac size and function (described in Supplementary Materials, Table S4). At the 3 months’ time point (9 weeks after the completion of GT3 treatment), GT3 treated animals exposed to 16O showed an increase in ejection fraction and fractional shortening, but these increases seemed to normalize over time (Figure 1). Exposure to 16O caused small but significant increases in ejection fraction and fractional shortening as measured 9 months in vehicle-treated animals. These increases may be an indication that the irradiated heart needs to compensate to maintain cardiac output or may be an indication of left ventricular tissue remodeling. Treatment with GT3 normalized the effects of radiation on ejection fraction and fractional shortening in irradiated animals. No major changes were seen in any of the other cardiac ultrasonography parameters (Supplementary Materials, Table S4).

Figure 1. Ejection fraction and fractional shortening after 16O and GT3.

Cardiac ejection fraction (A) and fractional shortening (B) were determined by ultrasonography at 3, 5, 7, and 9 months after 16O radiation exposure. n=11–14/group. a indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy, b indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy+GT3, and c indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0.25 Gy. Error bars are model-estimated SDs. Horizontal lines indicate there was a significant interaction between GT3 and radiation.

Exposure to 16O and administration of GT3 did not change blood flow parameters in the abdominal aorta (Supplementary Materials, Table S5), suggesting that larger vessel function was not altered.

3.3. Cardiac remodeling

No differences were found in heart weight relative to tibia length to correct for body size at any of the post-radiation time points (Supplementary Materials, Table S2). If radiation fibrosis develops in the heart, it is expected to appear late after radiation exposure. Therefore, assessment of collagen levels in the heart was performed at 9 months after irradiation. There was no significant difference in percentage area of cardiac tissue occupied by collagens 9 months after radiation exposure (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cardiac collagen levels after 16O and GT3.

Histological analysis of cardiac collagen deposition at 9 months after irradiation (A), representative immunoblot of left ventricular contents of collagen type III and GAPDH at 3 months (B), and collagen type III normalized to GAPDH at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 9 months after radiation (C). Error bars are model-estimated SDs. Total n=131 animals; time points 2 weeks and 3 months had n=10/group; and month 9 had n=11–14/group. a indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy, b indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy+GT3, and c indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0.25 Gy. Horizontal lines indicate there was a significant interaction between GT3 and radiation.

Immunoblot analysis of collagen type III revealed a band of approximately 75 kDa, as we previously observed in the mouse heart [20, 36] that appears to be a truncated peptide of collagen type III. As seen in our prior study [20], even though histological staining did not show an increase in total collagen deposition in the heart, the left ventricular content of the 75 kDa collagen type III peptide in vehicle-treated animals was significantly increased in the 16O exposed mice over sham at 2 weeks and 3 months. The change in left ventricular content of this peptide may be an indication of ongoing remodeling of collagen type III. A significant interaction between radiation and GT3 at 2 weeks and 3 months indicates that GT3 mitigated the effects of radiation on the 75 kDa collagen type III peptide content (Figure 2).

3.4. Cardiac immune cell infiltration

In previous studies with high-dose local X-ray exposure of the heart in rodent models, we found a correlation between cardiac mast cell numbers and collagen deposition [37]. Therefore, we assessed cardiac mast cell numbers as potential indicators of radiation-induced tissue remodeling at 9 months after irradiation. There was a significant decrease in mast cell numbers in the radiation group compared to sham (Figure 3). On the other hand, left ventricular mast cell tryptase content was significantly elevated in irradiated vehicle-treated animals over sham at 3 and 9 months. A significant interaction was seen between GT3 and radiation at all 3 time points, indicating that GT3 mitigated the effects of radiation on left ventricular mast cell tryptase levels (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cardiac mast cells after 16O and GT3.

Cardiac mast cell numbers per tissue area at 9 months after radiation (A), representative immunoblot of mast cell tryptase (MCT) and GAPDH at 3 months after radiation (B), and MCT density normalized to GAPDH at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 9 months (C). Error bars are model-estimated SDs. Total n=71 animals, with n=5–6/group at each time point. a indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy, b indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy+GT3, and c indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0.25 Gy. Horizontal lines indicate there was a significant interaction between GT3 and radiation.

We examined CD45 positive cells as a general marker of leukocytes (Supplementary Materials, Figure S1). In our prior study of male C57BL/6J mice exposed to 0.25 Gy 16O (600 MeV/n), we found consistent increases in markers of immune cells at 3 months after irradiation [20], therefore, in the current study we immunostained tissue sections for CD45, as a general marker of leukocytes, and counted the number of CD45 positive cells per mm2 tissue at the 3 months’ time point. While t-tests within the analysis of covariance showed no significant differences between the four experimental groups, there was a significant interaction between radiation and GT3 on the number of CD45 positive cells that pointed to a potential mitigative effect of GT3 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Left ventricular protein levels of immune cell markers after 16O and GT3.

Immunohistochemistry results for CD45 positive cells at 3 months after radiation exposure (A), representative immunoblots for left ventricular CD2 and CD68 at 3 months after radiation (B), Immunoblot analysis of CD2 (C) and CD68 (D) normalized to GAPDH at 2 weeks, 3 months, and 9 months after radiation. Error bars are model-estimated SDs. Total n=71 animals, with n=5–6/group at each time point. a indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy, b indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0 Gy+GT3, and c indicates p < 0.05 compared to time matched 0.25 Gy. Horizontal lines indicate there was a significant interaction between GT3 and radiation.

Even though the total number of leukocytes did not differ significantly between groups, we examined individual immune cell types by examining left ventricular CD2 and CD68 protein levels (Figure 4B). Consistent with our prior study [20], CD2 and CD68 were significantly increased in the 16O group compared to sham at 2 weeks and 3 months after irradiation. GT3 alone also significantly increased CD2 and CD68 at 2 weeks (when GT3 administration was ongoing) compared to sham-irradiated animals. On the other hand, GT3 treatment significantly reduced CD2 and CD68 content compared to radiation alone at 3 months and reduced CD68 at 9 months (Figure 4C–D).

3.5. Cardiac subcellular structure

Electron microscopy of hearts at 9 months after irradiation showed damaged mitochondria with disrupted cristae. This damage was not observed in mice treated with radiation and GT3 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Electron microscopy analysis of cardiac tissue after 16O and GT3.

Tissue specimens were examined at 9 months after radiation. Mitochondria in irradiated vehicle treated mice showed disrupted cristae. Magnification: 9,600×; scale bar = 1,000 nm.

3.6. False discovery rate

For each time point at which an outcome was measured, we made three comparisons: (i) 0 Gy vs 0.25 Gy, (ii) 0 Gy vs 0 Gy+GT3, (iii) (0 Gy – 0.25 Gy) vs (0 Gy+GT3 – 0.25 Gy+GT3). Altogether, we made 336 tests; 52 were significant at the 0.05 level. The positive False Discovery Rate was 0.285, meaning that about 15 of these 52 significant results may be false discoveries.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to provide the first evidence to indicate whether GT3 may be considered as a safe countermeasure against the degenerative tissue effects of space radiation in the heart. GT3 has long been known as a potent protector against the acute radiation syndrome when administered before exposure to low-LET radiation [21–23]. However, GT3 also has several properties that are beneficial to the cardiovascular system. GT3 is a potent inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. Interestingly, in contrast to statins, which are direct inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, GT3 reduces the levels of the enzyme by stimulating its intracellular degradation [26, 27]. Intermediates of the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway are used for post-translational modification of Rho proteins that are involved in endothelial cell functions such as stress fiber formation, expression of nitric oxide synthase, and production of cytokines and growth factors [38]. Therefore, inhibition of cholesterol biosynthesis has indirect benefits to endothelial function. While some studies have shown a relation between vitamin E intake and increased cancer rate [39], the majority of studies in humans and animal subjects show that several forms of vitamin E, including GT3 actually have cancer preventative properties [40, 41]. On the basis of these combined properties of GT3 and its apparent safety, we decided to test its effects on cardiovascular function and structure when administered after exposure to 16O as a model of space radiation.

Ultrasonography demonstrated small but significant increases in ejection fraction and fractional shortening in vehicle-treated animals at 9 months after 16O exposure. Yan et al. have also reported a small increase in ejection fraction in male C57BL/6NT mice from 1 to 10 months after a single dose of 0.15 Gy 56Fe (1 GeV/n) [15]. We hypothesize that this may be an indication that the irradiated heart needs to compensate to maintain cardiac output or a consequence of cardiac remodeling that is not yet fully understood. Treatment with GT3 mitigated the effects of radiation on ejection fraction and fractional shortening at 9 months.

The normal heart contains low numbers of mast cells [42, 43]. Mast cells produce a large variety of pro- and anti-fibrogenic mediators that regulate tissue remodeling. In our previous studies of localized cardiac x-ray exposure, radiation-induced pathological changes such as degeneration and fibrosis are closely correlated with increased mast cell numbers [37]. In the current study, mast cell numbers as determined from histological staining were significantly decreased after radiation exposure in vehicle-treated animals. It is possible that whole body irradiation has an effect on overall mast cell numbers or their ability to migrate into peripheral tissues. Nonetheless, an increase in left ventricular protein content of mast cell tryptase was seen in irradiated animals at the 3 and 9 month time points. These results may suggest that existing mast cells in the heart show increased activity in response to 16O irradiation as part of a subclinical event, rather than an actual accumulation of mast cells in the heart. In addition to normalizing the radiation-induced increases in ejection fraction and fractional shortening, GT3 administration mitigated the radiation-induced increases in left ventricular mast cell tryptase, suggesting its potential to alter adverse tissue remodeling.

To further assess tissue remodeling, we examined collagens in the heart. In vehicle-treated animals exposed to 0.25 Gy 16O, at 2 weeks and 3 months we found an increase in left ventricular content of a 75 kDa cleavage product of collagen type III, one of the most abundant collagens in the heart. On the other hand, there was no change in total collagen deposition as measured with histology. These results are in accordance with our prior findings of collagen type III at 2 weeks and 3 months and total collagens at 9 months in male C57BL/6J mice exposed to 0.25 Gy of 16O (600 MeV/n) [20]. Together, these results may indicate that while radiation fibrosis does not occur, there is active remodeling of extracellular matrix in the heart after exposure to 16O (600 MeV/n). In contrast, in a prior study, Yan et al reported an increase in cardiac collagen deposition at 10 months after exposure to protons (1 GeV, 0.5 Gy) or iron ions (1 GeV/n, 0.15 Gy) in adult male C57BL/6N mice [15]. Differences may be due to the use of a different mouse strain or different ions. Nonetheless, in the current study, the effects of 16O on left ventricular contents of 75 kDa collagen type III in GT3-treated animals was significantly lower than those in vehicle-treated animals at 2 weeks and 3 months, again suggesting the potential of GT3 to mitigate cardiac tissue remodeling from space radiation.

In addition to mast cell tryptase, we examined left ventricular protein content of CD2, and CD68, markers of T-lymphocytes and monocytes/macrophages, respectively. CD45 (leukocytes) cell numbers were also assessed but there was no change seen in this marker. CD2 and CD68 immune cell markers were increased at 2 weeks and 3 months after radiation in vehicle-treated animals, but were normalized by GT3 treatment. Previous studies have shown an increase in the number of CD68 positive cells at 2 and 4 weeks after 56Fe (0.15 Gy, 1 GeV/n) in mouse models [15, 44]. Moreover, Tungjai et al [17] showed an increase in inflammatory cytokines in the mouse heart in response to 28Si (300 MeV/n). These results suggest HZE exposure may only affect specific immune cells and not the immune system has a whole. Within irradiated animals, GT3 lowered CD2 levels at 2 weeks and 3 months and CD68 levels at 3 months and 9 months. Studies have previously shown tocopherols and tocotrienols can directly regulate signaling pathways in macrophages [45] and gene expression in T-lymphocytes [46]. However, the effects seen in the current study may also be due to an indirect regulation of immune cell function by GT3.

Since GT3 is known to protect mitochondria from radiation exposure, cardiac mitochondria were imaged using electron microscopy. Previous studies have demonstrated beneficial effects of tocotrienols on the mitochondria where a single dose of tocotrienols prevented mPTP opening alterations in mitochondrial respiration, and mitochondrial membrane potential [47, 48]. GT3 has also been shown to inhibit apoptosis by preventing cytochrome c release from the mitochondria resulting in suppressed caspase −3 and −9 activation [49]. In the current study, 16O irradiation disrupted mitochondrial cristae but this damage was not seen in the groups treated with GT3. This result suggests GT3 can also prevent cardiac mitochondrial damage when exposed to HZE radiation which has not been shown before.

Blood chemistry values were obtained at 9 months after 16O exposure to put in context with cardiovascular function and structure. A small increase in blood concentrations of Cl and decreases in ICA, Na and TCO2 may be an indication of reduced kidney function in 16O exposed mice. However, kidney dysfunction was not severe enough to elevate BUN levels. In a prior study, exposure of male Long Evans rats to 0.5 Gy 16O (600 MeV/n) did not alter any of these blood chemistry values at 12 months after irradiation [9], suggesting a species or strain dependent effect. Tocotrienol administration cause long-term improvements in kidney function in patients with diabetes [50]. In the current study, GT3 mitigated the effects of 16O on blood concentrations of Cl, ICA, Na and TCO2, suggesting that GT3 may indirectly affect the cardiovascular system by preserving kidney function. In addition, GT3 caused a small increase in HB and HCT only in irradiated animals. In prior animal studies, a single administration of tocotrienols caused an early decrease in HB and HCT that stabilized at day 7 [51] or had no effects on HB or HCT levels [52]. The biological mechanisms behind the apparent interaction between GT3 and radiation on HB and HCT in the current study are unknown.

The high charge and ionization density of 16O are representative of the relative biological effectiveness of the radiation environment inside a space craft, therefore we selected 16O as the model charged particle in this and our prior study [20]. Although the radiation dose of 0.25 Gy in this study is within the range of total doses experienced in deep space missions, practical considerations have limited this study to administering this dose within minutes, while the dose rates of HZE particles during space travel are many fold lower [53]. Therefore, if GT3 is further developed as radiation countermeasure for space travel, it should be tested in animal models of chronic or protracted exposures to HZE radiation. Also, while the current study focused on male C57BL/6 mice, a widely used animal model for radiation studies in the cardiovascular system [36, 54, 55], there may be sex differences in the risk for cardiovascular disease, and therefore future studies will be required in female animals.

In conclusion, results of this study provide some evidence of mild changes in cardiac function and remodeling after whole body exposure to a low dose of 16O (600 MeV/n) in male C57BL/6J mice, and some indication that administration of GT3 for 3 weeks after radiation mitigates these effects. If GT3 is considered as one of the radiation countermeasures to be developed further for space travel, its effects should be tested in female animals and in animals chronically exposed to simulated GCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work supported by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute under grant RE03701 through NCC 9-58, NASA grants 80NSSC17K0425 and 80NSSC19K0437, and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under grant P20 GM109005. The authors wish to thank the BNL support group, the NSRL physicists, the UAMS Experimental Pathology Core, and the animal care staff at UAMS and BNL for their excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Preston DL, et al. , Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: Solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950–1997. Radiat. Res, 2003. 160(4): p. 381–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozasa K, Takahashi I, and Grant EJ, Radiation-related risks of non-cancer outcomes in the atomic bomb survivors. Ann ICRP, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little MP, et al. , Systematic review and meta-analysis of circulatory disease from exposure to low-level ionizing radiation and estimates of potential population mortality risks. Environ Health Perspect, 2012. 120(11): p. 1503–1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonetto C, et al. , Ischemic heart disease in workers at Mayak PA: latency of incidence risk after radiation exposure. PLoS One, 2014. 9(5): p. e96309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr ZA, et al. , Coronary heart disease after radiotherapy for peptic ulcer disease. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys, 2005. 61(3): p. 842–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chancellor JC, Scott GBI, and Sutton JP, Space Radiation: The Number One Risk to Astronaut Health beyond Low Earth Orbit. Life, 2014. 4: p. 491–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hellweg CE and Baumstark-Khan C, Getting ready for the manned mission to Mars: the astronauts’ risk from space radiation. Naturwissenschaften, 2007. 94(7): p. 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCRP Report No. 153, Information Needed to Make Radiation Protection Recommendations for Space Missions Beyond Low-Earth Orbit. 2006: National Council on Radiation Protection & Measurements. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sridharan V, et al. , Effects of single-dose protons or oxygen ions on function and structure of the cardiovascular system in male Long Evans rats. Life Sci Space Res, 2020. 26: p. 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garikipati VNS, et al. , Long-Term Effects of Very Low Dose Particle Radiation on Gene Expression in the Heart: Degenerative Disease Risks. LID. Cells, 2021. 10(2): p. 387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sasi SP, et al. , Different Sequences of Fractionated Low-Dose Proton and Single Iron-Radiation-Induced Divergent Biological Responses in the Heart. Radiation research, 2017. 188(2): p. 191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramadan SS, et al. , A priming dose of protons alters the early cardiac cellular and molecular response to (56)Fe irradiation. Life Sci Space Res, 2016. 8: p. 8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koturbash I, et al. , Radiation-induced changes in DNA methylation of repetitive elements in the mouse heart. Mutation Research, 2016. 787: p. 43–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miousse IR, et al. , Changes in one-carbon metabolism and DNA methylation in the hearts of mice exposed to space environment-relevant doses of oxygen ions (16O). Life sciences in space research, 2019. 22: p. 8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan X, et al. , Cardiovascular risks associated with low dose ionizing particle radiation. PLoS One, 2014. 9(10): p. e110269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan X, et al. , Radiation-associated cardiovascular risks for future deep-space missions. J Radiat Res, 2014. 55 Suppl 1: p. i37–i39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tungjai M, Whorton EB, and Rithidech KN, Persistence of apoptosis and inflammatory responses in the heart and bone marrow of mice following whole-body exposure to (2)(8)Silicon ((2)(8)Si) ions. Radiat Environ Biophys, 2013. 52(3): p. 339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soucy KG, et al. , HZE (5)(6)Fe-ion irradiation induces endothelial dysfunction in rat aorta: role of xanthine oxidase. Radiat Res, 2011. 176(4): p. 474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker SA, Townsend LW, and Norbury JW, Heavy ion contributions to organ dose equivalent for the 1977 galactic cosmic ray spectrum. Adv Space Res, 2013. 51: p. 1792–1799. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seawright JW, et al. , Effects of low-dose oxygen ions and protons on cardiac function and structure in male C57BL/6J mice. Life Sci Space Res (Amst), 2019. 20(2214–5532 (Electronic)): p. 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berbee M, et al. , gamma-Tocotrienol ameliorates intestinal radiation injury and reduces vascular oxidative stress after total-body irradiation by an HMG-CoA reductase-dependent mechanism. Radiat. Res, 2009. 171(5): p. 596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh PK, et al. , Radioprotective efficacy of tocopherol succinate is mediated through granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. Cytokine, 2011. 56(2): p. 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosh SP, et al. , Gamma-tocotrienol, a tocol antioxidant as a potent radioprotector. Int J Radiat Biol, 2009. 85(7): p. 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida Y, Niki E, and Noguchi N, Comparative study on the action of tocopherols and tocotrienols as antioxidant: chemical and physical effects. Chem. Phys Lipids, 2003. 123(1): p. 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suarna C, et al. , Comparative antioxidant activity of tocotrienols and other natural lipid-soluble antioxidants in a homogeneous system, and in rat and human lipoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1993. 1166(2–3): p. 163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker RA, et al. , Tocotrienols regulate cholesterol production in mammalian cells by post-transcriptional suppression of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem, 1993. 268(15): p. 11230–11238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song BL and Bose-Boyd RA, Insig-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase stimulated by delta- and gamma-tocotrienols. J. Biol. Chem, 2006. 281(35): p. 25054–25061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berbee M, et al. , Mechanisms underlying the radioprotective properties of gamma-tocotrienol: comparative gene expression profiling in tocol-treated endothelial cells. Genes Nutr, 2012. 7: p. 75–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naito Y, et al. , Tocotrienols reduce 25-hydroxycholesterol-induced monocyte-endothelial cell interaction by inhibiting the surface expression of adhesion molecules. Atherosclerosis, 2005. 180(1): p. 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pathak R, et al. , Thrombomodulin contributes to gamma tocotrienol-mediated lethality protection and hematopoietic cell recovery in irradiated mice. PLoS One, 2015. 10(4): p. e0122511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cocchiaro JL, et al. , Cytoplasmic lipid droplets are translocated into the lumen of the Chlamydia trachomatis parasitophorous vacuole. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2008. 105(27): p. 9379–9384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J, et al. , Effects of heart rate and anesthetic timing on high-resolution echocardiographic assessment under isoflurane anesthesia in mice. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, 2010. 29(12): p. 1771–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelosi A, et al. , Cardiac effect of short-term experimental weight gain and loss in dogs. Vet Rec, 2013. 172(6): p. 153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kenward MG and Roger JH, An improved approximation to the precision of fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 2009. 53(7): p. 2583–2595. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storey JD, A Direct Approach to False Discovery Rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Statistical Methodology), 2002. 64(3): p. 479–498. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramadan SS, et al. , A priming dose of protons alters the early cardiac cellular and molecular response to (56)Fe irradiation. Life Sci Space Res (Amst), 2016. 8: p. 8–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boerma M, et al. , Histopathology of ventricles, coronary arteries and mast cell accumulation in transverse and longitudinal sections of the rat heart after irradiation. Oncology Reports, 2004. 12: p. 213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaffe AB and Hall A, RHO GTPASES: Biochemistry and Biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol, 2005. 21: p. 247–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein EA, et al. , Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). Jama, 2011. 306(14): p. 1549–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang Q, Natural Forms of Vitamin E as Effective Agents for Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Adv Nutr, 2017. 8(6): p. 850–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang CS, et al. , Vitamin E and cancer prevention: Studies with different forms of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Mol Carcinog, 2020. 59(4): p. 365–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellstrom B and Holmgren H, Numerical distribution of mast cells in the human skin and heart. Acta Anat. (Basel), 1950. 10(1–2): p. 81–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Constantinides P and Rutherdale J, Effects of age and endocrines on the mast cell counts of the rat myocardium. J Gerontol, 1957. 12(3): p. 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coleman M, et al. Delayed Cardiomyocyte Response to Total Body Heavy Ion Particle Radiation Exposure - Identification of Regulatory Gene Networks. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen J, et al. , δ-Tocotrienol, Isolated from Rice Bran, Exerts an Anti-Inflammatory Effect via MAPKs and PPARs Signaling Pathways in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Macrophages. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zingg JM, et al. , In vivo regulation of gene transcription by alpha- and gamma-tocopherol in murine T lymphocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2013. 538(2): p. 111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nowak G, et al. , γ-Tocotrienol protects against mitochondrial dysfunction and renal cell death. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 2012. 340(2): p. 330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sridharan V, et al. , A tocotrienol-enriched formulation protects against radiation-induced changes in cardiac mitochondria without modifying late cardiac function or structure. Radiation Research, 2015. 183(3): p. 357–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Makpol S, et al. , Inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and suppression of caspases by gamma-tocotrienol prevent apoptosis and delay aging in stress-induced premature senescence of skin fibroblasts. Oxid Med Cell longev, 2012. 2012(785743). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koay YY, et al. , A Phase IIb Randomized Controlled Trial Investigating the Effects of Tocotrienol-Rich Vitamin E on Diabetic Kidney Disease. Nutrients, 2021. 13(1): p. 258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satyamitra M, et al. , Mechanism of radioprotection by δ-tocotrienol: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and modulation of signalling pathways. Br J Radiol, 2012. 85(1019): p. e1093–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qureshi AA, et al. , Tocotrienols-induced inhibition of platelet thrombus formation and platelet aggregation in stenosed canine coronary arteries. Lipids Health Dis, 2011. 10: p. 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cucinotta FA, et al. , Radiation dosimetry and biophysical models of space radiation effects. Gravit. Space Biol Bull, 2003. 16(2): p. 11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patties I, et al. , Late inflammatory and thrombotic changes in irradiated hearts of C57BL/6 wild-type and atherosclerosis-prone ApoE-deficient mice. Strahlenther. Onkol, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghosh P, et al. , Effects of High-LET Radiation Exposure and Hindlimb Unloading on Skeletal Muscle Resistance Artery Vasomotor Properties and Cancellous Bone Microarchitecture in Mice. Radiat Res, 2016. 185(3): p. 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.