Abstract

Background:

Behavioral economics predicts that recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder involves shifts in resource allocation away from drinking, toward valuable nondrinking rewards that reinforce and stabilize recovery behavior patterns. Further, these shifts should distinguish nonproblem drinking (moderation) outcomes from outcomes involving abstinence or relapse. To evaluate these hypotheses, 5 prospective studies of recent natural recovery attempts were integrated to examine changes in monetary spending during the year following the initial cessation of heavy drinking as a function of 1-year drinking outcomes.

Methods:

Problem drinkers from Southeastern U.S. communities (N = 493, 67% male, 65% white, mean age = 46.5 years) were enrolled soon after stopping heavy drinking without treatment and followed prospectively for a year. An expanded Timeline Followback interview assessed daily drinking and monetary spending on alcohol and nondrinking commodities during the year before and after recovery initiation.

Results:

Longitudinal associations between postresolution drinking and spending were evaluated using MPlus v.8. Initial models evaluated whether changes in spending at 4-month intervals predicted drinking outcomes at 1 year and showed significant associations in 6 commodity categories (alcohol, consumable goods, gifts, entertainment, financial/legal affairs, housing/durable goods/insurance; ps < 0.05). Cross-lagged models showed that the moderation outcome group shifted spending mid-year to obtain large rewards with enduring benefits (e.g., housing), whereas the abstinent and relapsed groups spent less overall and purchased smaller rewards (e.g., consumable goods, entertainment, and gifts) throughout the year.

Conclusions:

Dynamic changes in monetary allocation occurred during the postresolution year. As hypothesized, compared to the groups who abstained or relapsed, the moderation group shifted spending in ways that, overall, yielded higher value alcohol-free reinforcement that should reinforce recovery while they enjoyed some limited nonproblem drinking below heavy drinking thresholds. These findings add to evidence that moderation entails different behavioral regulation processes than abstinent and relapse outcomes, which were more similar to one another.

Keywords: alcohol use disorder, behavioral economics, moderation, monetary allocation, natural recovery

INTRODUCTION

Most individuals who develop an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) or have subclinical problems eventually reduce or resolve their problem, and some achieve stable “recovery” (Tucker, Chandler et al., 2020; Witkiewitz, Montes et al., 2020). Over 70% of problem resolutions occur outside the context of treatment or mutual-help participation, and stable limited drinking without problems (moderation) is a more common outcome in untreated than treated samples (Fan et al., 2019; Sobell et al., 1996), in part because many treatment programs emphasize abstinence, and treatment-seeking is associated with higher problem severity. Studying “natural recovery” offers an opportunity to investigate moderation drinking processes and outcomes, which many people with drinking problems prefer, and can inform intervention development across the problem severity spectrum, thereby helping close the gap between population need and alcohol service utilization (Tucker & Simpson, 2011).

Behavioral economics offers a conceptual framework and body of research with utility for investigating recovery processes and outcomes. Behavioral economics builds on operant animal experiments of behavioral allocation under different concurrent schedules of reinforcement, which led to the well-established matching law (Herrnstein, 1974; Rachlin & Laibson, 1997); that is, over temporally extended intervals involving many choices, humans and animals distribute or “match” their relative rates of responding in proportion to the relative rates of reinforcement available from each activity. Thus, preference for a given activity or commodity (e.g., alcohol consumption) depends on other available activities and commodities in the choice context and on the relative constraints on access to them (e.g., cost to obtain, delay to receipt). The context of choice is the sum of commodities available under variable constraints, and relative commodity preferences are inferred from how behavior and resources (e.g., time, money, and effort) are distributed among them (Rachlin et al., 1981).

The framework is well suited to studying harmful substance use because the primary problem is excessive demand for substances in relation to other activities available under variable constraints over lengthy time frames. Harmful use is viewed as a reinforcer pathology (Bickel et al., 2014) that involves persistent preference for drug rewards that provide immediate reinforcement (e.g., stimulant, anxiolytic, or analgesic effects) but have delayed costs in important life-health domains (e.g., health, relationships, and employment), as compared to drug-free alternatives that typically have lower short-term but higher long-term value. Behavioral economic research has shown that substance use is more likely when (1) the immediate cost of substance use is low and few constraints exist on substance access, (2) the choice environment has limited rewarding substance-free alternatives, and (3) individuals have a greater tendency to prefer immediate over delayed rewards (Ahmed, 2018; Vuchinich & Heather, 2003). Conversely, enriching the environment and increasing engagement in drug-free alternatives decrease substance use (Acuff et al., 2019; Carroll, 1993; Vuchinich & Tucker, 1988).

Behavioral economics conceptualizes recovery as forgoing the immediate rewarding act of drinking— and its longer term negative consequences—in favor of behavior patterns that offer delayed substance-free rewards of higher value that in turn reinforce sobriety behaviors. Several efficacious interventions guided by behavioral economic principles explicitly aim to reduce substance use by increasing engagement in rewarding alternatives to use (Daughters et al., 2018; Hunt & Azrin, 1973; Murphy et al., 2019). Similarly, long-term prospective studies of treatment and community samples of heavy drinkers have shown that positive outcomes were accompanied by improvements in health, life satisfaction, and functioning that likely serve to motivate and reinforce recovery behaviors and outcomes (Moos & Moos, 2007; Witkiewitz et al., 2019). Access to rewarding social opportunities can also help explain the appeal and effectiveness of mutual-help groups such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA; Kelly et al., 2012).

The present research extended these findings by investigating how behavioral allocation patterns change during the year after a natural recovery attempt. Behavioral economics predicts that successful recovery entails shifts in resource allocation away from drinking toward valuable, often delayed nondrinking rewards that motivate and maintain positive change. Building on our prior natural recovery research guided by behavioral economics (Tucker et al., 2002, 2006, 2008, 2012, 2016; Tucker, Cheong et al., 2020), these shifts in resource allocation after initial cessation of heavy drinking should distinguish among outcomes involving stable moderation, stable abstinence, or unstable resolution involving relapse. Resource allocation was assessed based on monetary expenditures during the year before initial cessation of heavy drinking. More balanced discretionary expenditures on alcohol vs. saving for the future predicted stable nonabstinent resolutions over 1- to 2-year follow-ups compared to stable abstinent resolutions or unstable resolutions involving relapse, which were associated with similar expenditure patterns favoring greater proportionate alcohol spending. Thus, even when drinking heavily, problem drinkers with more balanced allocation patterns indicative of greater sensitivity to longer term contingencies were more successful in maintaining moderation than those with less-balanced indices (Tucker et al., 2009, 2016; Tucker, Cheong et al., 2020). The similarities between abstinent and relapse outcomes as distinct from moderation outcomes are consistent with early theorizing (Marlatt, 1985) that viewed abstinence and relapse as opposite ends of the same dynamic behavioral regulation process, reflecting over- and undercontrol of the daily act of drinking, respectively. Moderation was considered a qualitatively different process involving lifestyle balance and repetitive choices to drink well within the boundaries of extreme restraint or loss-of-control drinking.

These preresolution findings were extended by investigating how expenditure patterns shifted during the year after recovery initiation and were associated with different drinking outcomes, with emphasis on moderation. We integrated our natural recovery studies to obtain sufficiently large groups of drinkers who achieved stable moderation and other outcomes to address the research questions. The main hypothesis was that stable moderation would be associated with distinctive postresolution expenditure patterns. Although all outcome groups were expected to show reduced alcohol spending and some spending shifts in favor of nondrinking rewards, the postresolution spending shifts among the moderation outcome group were predicted to involve greater variability and to result in relatively higher value overall alcohol-free reinforcement that should reinforce recovery while they enjoyed some limited drinking without problems. Thus, the “consumption bundles” or aggregated collection of all goods and services consumed (Krugman & Wells, 2012) were predicted to be higher in the moderation outcome group relative to the other outcome groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample selection and characteristics

Research volunteers who had recently overcome a drinking problem on their own were recruited using media advertisements in cities in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee for 5 prospective studies of recovery attempts conducted from 1993 to 2015 (Tucker et al., 2002, 2006, 2008, 2012, 2016). Ad respondents were screened using the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS; Skinner & Horn, 1984), Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST; Selzer, 1971), and Drinking Problems Scale (DPS; Cahalan, 1970). Each study received university Institutional Review Board approval and a U.S. federal Certificate of Confidentiality. Procedures conformed to STROBE guidelines for observational studies (von Elm et al., 2007).

Eligibility criteria in all studies were as follows: (a) legal drinking age (≥21 years); (b) problem drinking history ≥2 years based on screening reports when participants first experienced alcohol-related problems (e.g., marriage, job, or health problems) (M = 16.6 years, SD = 11.1) and detailed assessment at enrollment of preresolution drinking practices, alcohol-related problems, and alcohol dependence levels; (c) other than nicotine, no current other drug misuse, assessed during screening by asking if participants had “used non-prescribed or prescribed drugs except for reasons related to health problems or health maintenance as directed by a physician” and, if yes, the drug(s), dates of use, usual amount and pattern of use, and current use status; and (d) recent cessation of heavy drinking while residing in the community (M = 14.5 weeks resolved, SD = 8.91). Depending on the study, eligible participants had abstained or consumed alcohol in a nonproblem manner for a minimum of 3 weeks and a maximum of 6 months, with nonproblem drinking defined as (a) alcohol consumption established as having minimal health risks (Sobell et al., 1992) and aligned with the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism (NIAAA, 2005) guidelines for drinking practices below quantity thresholds associated with increased risk of alcohol problems (≤ 4 drinks/day for men, ≤3 drinks/day for women) and below thresholds for heavy drinking (NIAAA, 2020); (b) no alcohol-related negative consequences (DPS), and (c) no dependence symptoms (ADS). Almost everyone (99.4%) met alcohol dependence diagnostic criteria before resolution (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; American Psychiatric Association, 2004). Most participants were intervention naïve (69.0%); 17.6% had attended AA only, and 13.5% had attended alcohol treatment plus AA at some point before their recent quit attempt on their own. Drinking outcomes did not differ as a function of help-seeking status.

Participants’ resolution date was the first day they stopped heavy drinking and became abstinent or engaged in moderation drinking without problems. All studies had at least a 1-year follow-up assessment, the basis for categorizing drinking outcomes as either resolved abstinent (RA), resolved nonabstinent (RNA), or unstable resolution (UR) involving at least 1 relapse (Sobell et al., 1996). Characteristics of the integrated “Alcohol Recovery in Community” (ARC) sample comprising all five studies are presented in Table 1 for participants with 1-year drinking outcomes (N = 493). Typical of natural recovery samples (Klingemann & Sobell, 2007), participants were generally middle-aged, middle-income, and educated beyond high school. Gender composition approximated the U.S. problem drinker population (67% male). Race/ethnicity composition approximated the southeastern U.S. region where the research was conducted (65% White; 32% African American; <1.2% each Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, Native American, or other race/ethnicity). An additional 123 enrolled participants had unknown 1-year outcomes because they either withdrew early (n = 20), died (5), or did not keep follow-up appointments (98). Those lost to follow-up were similar to the UR and RA groups on problem severity indicators. Their higher risk levels are in line with clinical research suggesting that treatment drop-outs fare relatively poorly (Haug & Schaub, 2016), and the present attrition rate was not markedly different from treatment outcome studies with similar follow-up periods.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics as a function of drinking status at 1-year after initial resolution

| Variable | Drinking Status at 1-year after Initial Resolution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolved Abstinent (n = 273) |

Unstable Resolution (n = 140) |

Resolved Nonabstinent (n = 80) |

Test statistic | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 181 (66.79) | 93 (66.91) | 57 (71.25) | χ2 (2) = 0.60 |

| Female, n (%) | 90 (33.21) | 46 (33.09) | 23 (28.75) | |

| White, n (%) | 178 (65.93) | 86 (62.32) | 57 (71.25) | χ2 (2) = 11.28*** |

| Other race/ethnicity, n (%) | 92 (34.07) | 52 (37.68) | 23 (28.75) | |

| Married, n (%) | 107 (40.07) | 47 (34.56) | 41 (51.25) | χ2 (2) = 5.85 |

| Not Married, n (%) | 160 (59.93) | 89 (65.44) | 39 (48.75) | |

| Employed full/part time, n (%) | 121 (45.32) | 63 (46.32) | 42 (52.50) | χ2 (2) = 1.29 |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 146 (54.68) | 73 (53.68) | 38 (47.50) | |

| Age (years) | 46.49 (10.75)a | 47.19 (11.87)a | 51.18 (14.09)b | F(2, 487) = 5.03*** |

| Education (years) | 13.82 (2.75)a | 14.37 (2.96)ab | 14.76 (2.31)b | F(2, 479) = 4.29** |

| Drinking problem history | ||||

| Help-seeking history (AA or treatment), n (%) | 49 (40.83) | 22 (40.74) | 4 (13.79) | χ2(2) = 7.79** |

| Drinking problem duration (years) | 17.09 (10.88) | 17.64 (11.45) | 16.11 (12.21) | F(2, 473) = 0.46 |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale (47) | 21.64 (9.58)a | 18.52 (8.62)b | 16.49 (8.50)b | F(2, 479) = 11.91*** |

| Drinking Problems Scale (40) | 18.25 (8.90)a | 16.44 (8.66)ab | 13.79 (8.30)b | F(2, 486) = 8.49*** |

| Preresolution year drinking practices (TLFB) | ||||

| Number of heavy drinking days (0– 365) | 246.67 (124.63)a | 197.76 (120.27)b | 210.94 (144.99)a | F(2, 486) = 7.55*** |

| Mean quantity per drinking day (ml ethanol) | 229.34 (196.93)a | 172.49 (120.71)b | 137.36 (90.37)b | F(2, 487) = 12.07*** |

| Preresolution year monetary allocation ($) | ||||

| Total income | 53,559 (70,612) | 62,657 (87,736) | 66,535 (66,810) | F(2, 485) = 1.24 |

| Total expenditures | 52,628 (56,683) | 55,970 (61,677) | 68,326 (52,228) | F(2, 484) = 2.28 |

| Discretionary expenditures (DE) | 15,953 (15,229) | 16,468 (14,959) | 17,023 (12,447) | F(2, 484) = 0.18 |

| Expenditures on alcohol | 3758 (3812)a | 3055 (2763)a | 2690 (3026)b | F(2, 485) = 3.90* |

| Money saved | 1664 (5466) | 1225 (4400) | 1784 (4670) | F(2, 485) = 0.44 |

| Alcohol/Savings DE index | 0.24 (0.28)a | 0.21 (0.29)a | 0.14 (0.31)b | F(2, 484) = 3.59* |

| Postresolution year drinking practices (TLFB) | ||||

| Number of heavy drinking days (0– 365) | 0.01 (0.10)a | 35.66 (56.70)b | 3.41 (25.61)a | F(2, 487) = 59.86*** |

| Mean quantity per drinking day (ml ethanol) | 4.14 (33.67)a | 113.87 (90.62)b | 38.49 (23.81)c | F(2, 487) = 181.59*** |

| Postresolution year monetary allocation ($) | ||||

| Total income | 51,829 (75,832) | 58,168 (98,713) | 70,737 (93,842) | F(2, 486) = 1.53 |

| Total expenditures | 49,594 (67,242) | 51,274 (67,553) | 63,093 (69,828) | F(2, 486) = 1.25 |

| Discretionary expenditures | 11,591 (11,820)a | 14,799 (22,142)a | 14,363 (18,647)a | F(2, 486) = 2.08 |

| Expenditures on alcohol | 72 (247)a | 561 (858)b | 299 (644)c | F(2, 487) = 35.84*** |

| Money saved | 1854 (5287) | 2390 (12,710) | 2655 (10,965) | F(2, 486) = 0.35 |

| Alcohol/Savings DE index | −0.09 (0.18)a | 0.02 (0.19)b | −0.05 (0.16)a | F(2, 486) = 16.11*** |

Note: Table shows means (standard deviations) for continuous variables and frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables for participants with 1-year outcome data (N = 493). Percentages reflect nonmissing cases in each categorical variable. Possible score ranges for scaled questionnaires are given in parentheses after the variable name. Higher Drinking Problems Scale scores indicate greater alcohol-related problems; higher Alcohol Dependence Scale scores indicate greater alcohol dependence levels. ASDE values could range from 1.0 to – 1.0 [1.0 = all discretionary expenditures (DE) for alcoholic beverages; – 1.0 = all DE were for saving money; 0 = equal proportions of DE for alcohol and savings). TLFB =Timeline Followback interview. Heavy drinking days: >4 drinks for women and >5 drinks for men. Monetary variables were inflation-adjusted based on national data on personal consumption expenditures provided by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=underlying). Means and frequencies with different superscripts were significantly different in pairwise comparisons.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.00.

Procedures and measures

In-person 1.5- to 3.0-hour assessments were conducted at enrollment and 12 months later. Sobriety was verified by breathalyzer. With participants’ consent, a collateral (e.g., spouse) was interviewed by phone for 69.7% of participants to verify eligibility and/ or postresolution drinking reports. When collaterals were unavailable, participant screening reports were compared with initial interview reports of eligibility criteria, and multiple follow-up reports of drinking during the same time periods were compared for consistency. Participants with unreliable reports were excluded (<1%). Participants received from $30 to $75 for each in-person assessment, with the amounts increasing over the 23-year period spanned by the 5 studies.

As described next, an expanded Timeline Followback (TLFB) interview (Sobell & Sobell, 1992; Vuchinich et al., 1988) conducted at enrollment and the 1-year follow-up assessed drinking practices, income, and expenditures covering the preceding year and produced detailed behavioral records covering the 2 years surrounding sobriety onset. The assessment aimed to identify regularities between drinking patterns and environmental contexts measured in terms of other available commodities and activities and required 2 measurement features: (1) Environment–behavior relationships were assessed over sufficiently long intervals to capture many choices so that behavioral patterning could be discerned. (2) Because different activities and commodities vary considerably in their topography, a common metric, money in this case, was needed that reflected relative resource allocation to— and thus the relative reinforcement value of—drinking compared to other choice alternatives.

Drinking practices

Participants reported daily drinking as ounces of beer, wine, and liquor intake using standard TLFB procedures (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) that included recall aids covering the assessment interval (e.g., calendars, lists of news and entertainment events, photographs of different kinds and sizes of alcoholic beverages), and participants also were asked to use personal recall aids (e.g., financial records and appointment books). Reports were converted to ml of 190-proof ethanol for analysis. The TLFB interview is considered the “gold standard” for collecting reliable and accurate daily reports of abstinence or quantities consumed on days involving drinking (Falk et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2002, 2007, 2008; Witkiewitz et al., 2015), and each study integrated in the Project ARC data set included checks on the quality of participant TLFB reports. For example, Tucker et al., (2007) conducted reliability checks between participants’ time-matched reports of drinking during natural recovery attempts on the TLFB and a daily interactive voice response (IVR) self-monitoring system and found correlations >0.90 for aggregated measures of heavy, moderate, and total drinking days.

Monetary expenditures

Using an expanded TLFB format and the recall aids described above (Vuchinich et al., 1988), participants were asked to report how much money they spent each day on alcoholic beverages, regardless of whether the beverages were consumed. This was not excessively difficult because alcoholic beverages are sold in standard quantities, and problem drinkers typically consume large quantities of a few preferred beverages. Then, using an interviewing strategy similar to the TLFB drinking assessment, participants reported their spending in dollars on other commodities for each day that a purchase occurred during the preceding year. Commodity classes were adapted from the Consumer Expenditure Surveys for the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Vuchinich & Tucker, 1996; see https://www.bls.gov/cex/). Expenditures were reported in three general categories, each with subcategories: housing (e.g., mortgage, rent, and utilities), consumable goods (e.g., food, tobacco, and alcohol), and other (e.g., entertainment, transportation, loan payments, and money saved). Reports in each category were summed over different intervals for analysis. In addition to direct verification using financial records (Tucker et al., 2002, 2006; Vuchinich & Tucker, 1996), data quality was variously assessed by reliability and internal consistency checks. High correlations were found between TLFB and screening questionnaire reports of total income (r = 0.85, p < 0.0001; Tucker et al., 2006) and between participants’ time-matched TLFB-IVR reports of the percentage of days involving expenditures on alcohol (r = 0.90, p < 0.005; Tucker et al., 2007).

Drinking status

To examine longitudinal relationships between postresolution drinking and spending patterns among participants with 1-year follow-up data, drinking status codes were assigned based on the entire year (i.e., terminal 1-year status) and based on shorter intervals (e.g., 4-month quadrimesters). Outcome status codes at 1-year were based on participants’ drinking practices and problems during the entire year: (1) RA—continuous abstinence (n = 273), (2) RNA—moderation drinking only, no relapses or alcohol-related problems (n = 80), and (3) UR—1 or more relapses defined as daily drinking above heavy or binge drinking thresholds (4+/5+ drinks for women/men; n = 140). The same criteria were used for drinking status codes for shorter postresolution intervals. As Table 1 shows, postresolution drinking among the RNA and UR groups had good separation within or above quantity thresholds associated with increased risk of alcohol problems (NIAAA, 2005, 2020), respectively.

Data analyses

Multiple sample checks were performed prior to the analyses. Demographic and drinking history variables were examined to identify sources of heterogeneity across studies and control for their potential influence as nuisance factors in the integrated data set (Curran & Hussong, 2009). Measurement harmonization was unnecessary because the same research team conducted all studies using identical measures, selection criteria, and follow-up procedures in the same geographic region. Next, 2 features of the postresolution expenditure data were assessed prior to the longitudinal analyses: (1) seasonality of longitudinal data patterns based on monthly spending in each commodity category using 1-way ANOVAs; and (2) expenditure graphs for each category at 3-, 4-, and 6-month intervals to select a data aggregation interval for the longitudinal models and to determine whether specific commodity classes should be combined for analysis because of similar longitudinal patterning. Monetary variables were inflation-adjusted based on national data for personal consumption expenditures provided by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=19&step=2#reqid=19&step=2&isuri=1&1921=underlying) to be comparable to the most recent data collection year (i.e., 2015).

No significant seasonality was found except for spending on gifts (highest in November, likely due to holiday shopping), and no differential seasonality was found across terminal drinking status or time of resolution onset (the month resolution started). Thus, seasonality adjustments were not required. Graphs of drinking-expenditure associations were clearest using 4-month data aggregation intervals (quadrimesters), which were confirmed in preliminary longitudinal analyses using 3-, 4-, and 6-month intervals. Therefore, 4-month intervals were used in the primary longitudinal analyses. As Table S1 shows, 8 final commodity classes effectively captured participants’ pre- and postresolution expenditure patterns. The classes included obligatory expenditures on essential commodities that varied in terms of whether they were typically purchased frequently (e.g., consumable goods and transportation) or entailed longer term financial choices and commitments (e.g., housing, durable goods, and financial management), as well as discretionary expenditures on commodities such as alcohol, gifts, and entertainment. As an overall test of changes in alcohol spending before and after resolution onset, a 2-way (3 × 2) mixed ANOVA was conducted on the proportion of dollars spent on alcohol relative to total expenditures. Drinking status at 1-year was the between-subject factor (RA, UR, or RNA), and time (pre- and postresolution years) was the within-subject factor.

Two sets of longitudinal analyses were conducted using MPlus v.8 (Muthén & Muthen, 1998–2017). First, to evaluate whether postresolution spending patterns predicted 1-year drinking outcomes, drinking status at 1 year (RA, UR, or RNA) was predicted by spending in inflation-adjusted dollar amounts during the 4-month quadrimesters. Dollar amounts spent during the 3 quadrimesters were simultaneously included in the models as predictors of 1-year drinking outcome group membership, estimating time-specific predictability of spending patterns controlling for those in other intervals. Second, if significant results were obtained for a given commodity class, cross-lagged models were estimated to examine whether spending during the previous quadrimester was related drinking status in the next quadrimester and vice versa. For these models, money spent on each category and drinking status at an earlier interval (time t−1) was modeled to predict drinking status and spending during the next interval (time t), respectively, across the 3 quadrimesters during the postresolution year. Because drinking status was a categorical variable with 3 levels (RA, RNA, and UR), it could not be treated simultaneously as the predictor and the outcome in cross-lagged models in the current version of Mplus (Muthén & Muthen, 1998–2017). Thus, cross-lagged models were examined between 2 time points 1 at a time (i.e., quadrimester 1 and quadrimester 2, quadrimester 2 and quadrimester 3), and the results were put together. For drinking status, either as the predictor or the outcome, the RNA group was the referent in comparisons with the RA or UR group. Covariates were demographic variables (gender, age, white/nonwhite race, married/ unmarried status, education, income) and preresolution drinking-related characteristics predicting 1-year drinking outcomes in our earlier research (ADS scores, drinking problem duration, gender-adjusted days “well functioning” [abstinent +gender-adjusted low-risk drinking days]), and the Alcohol-Savings Discretionary Expenditure [ASDE index], computed as the proportion of discretionary expenditures on drinking minus the proportion of discretionary expenditures put into savings). Note that the preresolution year ASDE index, which reliably predicts drinking outcomes (e.g., Tucker et al., 2009, 2016; Tucker, Cheong et al., 2020) was used as a covariate. The index was not useful for tracking dynamic changes in postresolution spending over shorter periods after heavy drinking stopped or was greatly reduced, and little money was spent buying alcoholic beverages. Participants lost to follow-up were excluded to eliminate potential prediction inaccuracy. As the monetary variables were skewed, they were log-transformed to reduce nonnormality; MLR, an estimator robust to the violation of normality assumption, was used in the analyses.

RESULTS

Pre/postresolution shifts in alcohol and nonalcohol expenditures

For each terminal drinking status outcome group, Table 2 presents the inflation-adjusted mean dollar expenditures for each commodity category in units of $100 for each quadrimester during the pre- and postresolution years, along with the 95% confidence intervals. These descriptive data are displayed graphically in Figure S1. As summarized in Table S1, spending on alcoholic beverages decreased pre/post from 6% to <1% of all expenditures, as expected given that participants had initiated a serious quit attempt. Among the other categories, the largest ones that together accounted for >80% of expenditures during both years were housing, durable goods, and associated insurance (excluding health insurance); financial/legal affairs (including retirement/other savings, investments, taxes, loans, legal, alimony, child support); and consumable goods other than alcohol (groceries, eating out, clothing, tobacco products). Transportation costs, gifts given to another, entertainment, and health care each accounted for <5% of spending during both years.

TABLE 2.

Dollar amounts spent on expenditure categories for the year before and after initial resolution onset as a function of 1-year drinking status

| Preresolution Year |

Preresolution Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditure category | Drinking status |

Mean $ (Unit: $100)a (95% CI) |

Mean $ (Unit: $100)a (95% CI) |

||||

| Q1b | Q2b | Q3b | Q1b | Q2b | Q3b | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | RA | 12.97 (11.22, 14.72) |

12.83 (11.02, 14.65) |

12.55 (10.91, 14.18) |

0.26 (0.14, 0.38) |

0.28 (0.15, 0.41) |

0.30 (0.16, 0.44) |

| UR | 10.52 (8.46, 12.57) |

10.15 (8.28, 12.02) |

9.50 (7.66, 11.35) |

1.33 (0.89, 1.78) |

2.03 (1.41, 2.65) |

2.92 (2.03, 3.82) |

|

| RNA | 8.35 (5.57, 11.13) |

9.07 (6.08, 12.05) |

7.90 (5.48, 10.33) |

0.91 (0.40, 1.42) |

1.25 (0.59, 1.91) |

1.35 (0.69, 2.01) |

|

| Housing/durable goods/insurance | RA | 77.89 (61.90, 93.88) |

65.78 (52.53, 79.02) |

57.53 (47.31, 67.74) |

80.27 (66.28, 94.25) |

101.12 (28.86, 173.38) |

78.66 (48.31, 109.01) |

| UR | 69.97 (56.21, 83.72) |

59.93 (48.02, 71.83) |

60.46 (47.86, 73.07) |

96.35 (47.45, 145.25) |

67.76 (47.55, 87.97) |

61.37 (47.35, 75.39) |

|

| RNA | 98.68 (73.42, 123.94) |

98.67 (60.07, 137.27) |

73.49 (50.73, 96.25) |

83.71 (61.17, 106.24) |

158.47 (−3.51, 320.45) |

107.60 (34.90, 180.29) |

|

| Financial/legal management | RA | 60.79 (39.37, 82.22) |

51.42 (35.66, 67.17) |

48.96 (32.67, 65.26) |

53.52 (40.72, 66.31) |

51.35 (34.87, 67.83) |

46.03 (33.99, 58.07) |

| UR | 58.81 (35.84, 81.79) |

60.00 (33.14, 86.86) |

61.60 (34.73, 88.48) |

73.91 (40.13, 107.69) |

56.46 (23.93, 88.99) |

53.23 (34.25, 72.22) |

|

| RNA | 82.35 (43.00, 121.69) |

69.12 (39.24, 99.01) |

69.20 (36.38, 102.02) |

73.57 (35.70, 111.44) |

41.68 (23.51, 59.86) |

76.00 (36.15, 115.86) |

|

| Other consumable goods | RA | 25.58 (22.86, 28.29) |

23.58 (21.26, 25.90) |

22.92 (20.47, 25.38) |

24.63 (22.07, 27.18) |

22.73 (20.37, 25.10) |

22.54 (20.54, 24.54) |

| UR | 29.67 (24.88, 34.47) |

28.22 (23.01, 33.42) |

27.47 (21.45, 33.50) |

31.74 (25.03, 38.45) |

27.90 (22.64, 33.16) |

27.93 (23.30, 32.56) |

|

| RNA | 26.86 (22.20, 31.53) |

24.98 (20.67, 29.29) |

24.19 (20.25, 28.14) |

25.00 (20.74, 29.25) |

23.74 (19.55, 27.93) |

23.81 (19.54, 28.09) |

|

| Transportation costs | RA | 7.42 (6.27, 8.57) |

8.42 (5.87, 10.97) |

7.97 (6.10, 9.85) |

7.83 (6.44, 9.22) |

6.74 (5.78, 7.70) |

7.36 (6.31, 8.40) |

| UR | 7.42 (5.88, 8.95) |

6.71 (5.25, 8.18) |

6.78 (5.26, 8.30) |

6.75 (5.41, 8.09) |

5.94 (4.71, 7.17) |

8.19 (3.85, 12.53) |

|

| RNA | 8.89 (5.47, 12.32) |

7.89 (4.98, 10.80) |

8.11 (4.91, 11.32) |

7.74 (5.13, 10.34) |

6.10 (4.64, 7.56) |

6.75 (4.47, 9.02) |

|

| Gifts given to another | RA | 10.23 (5.81, 14.65) |

6.83 (4.79, 8.86) |

6.84 (4.19, 9.48) |

10.23 (7.17, 13.29) |

6.53 (4.28, 8.77) |

8.01 (5.41, 10.62) |

| UR | 12.05 (7.26, 16.84) |

7.01 (3.31, 10.72) |

7.00 (4.33, 9.68) |

14.27 (8.10, 20.43) |

8.55 (2.18, 14.92) |

6.75 (3.52, 9.97) |

|

| RNA | 13.54 (6.22, 20.86) |

8.69 (3.14, 14.23) |

7.32 (3.67, 10.96) |

15.56 (4.79, 26.33) |

4.88 (2.21, 7.54) |

9.08 (4.92, 13.25) |

|

| Health care | RA | 6.48 (1.57, 11.39) |

5.45 (1.56, 9.34) |

5.69 (2.42, 8.95) |

6.86 (3.41, 10.32) |

4.45 (2.54, 6.35) |

4.55 (2.67, 6.44) |

| UR | 5.34 (3.67, 7.01) |

4.64 (3.04, 6.24) |

4.93 (2.86, 7.01) |

4.17 (2.74, 5.61) |

4.00 (2.18, 5.81) |

3.87 (2.48, 5.25) |

|

| RNA | 11.26 (4.98, 17.53) |

4.77 (2.50, 7.04) |

7.46 (2.51, 12.41) |

6.97 (3.23, 10.72) |

6.01 (0.75, 11.27) |

8.40 (2.70, 14.11) |

|

| Entertainment | RA | 4.85 (−0.37, 10.08) |

1.74 (1.22, 2.25) |

1.65 (1.12, 2.19) |

1.99 (1.36, 2.62) |

1.53 (0.90, 2.15) |

2.04 (1.29, 2.80) |

| UR | 2.78 (1.43, 4.13) |

2.15 (1.00, 3.30) |

2.14 (1.11, 3.17) |

2.14 (1.23, 3.05) |

1.21 (0.84, 1.59) |

1.87 (1.35, 2.38) |

|

| RNA | 5.22 (0.37, 10.07) |

1.75 (1.24, 2.26) |

1.91 (1.24, 2.57) |

2.69 (0.48, 4.90) |

1.76 (0.94, 2.58) |

1.60 (0.88, 2.32) |

|

Note: Drinking status at 1-year follow-up: RA, resolved abstinent; UR, unresolved; RNA, resolved nonabstinent.

Mean dollar amounts spent on each expenditure category and 95% confidence intervals (Unit: $100).

Q1, Q2, and Q3 indicate first, second, and third quadrimester of pre- and postresolution year, respectively.

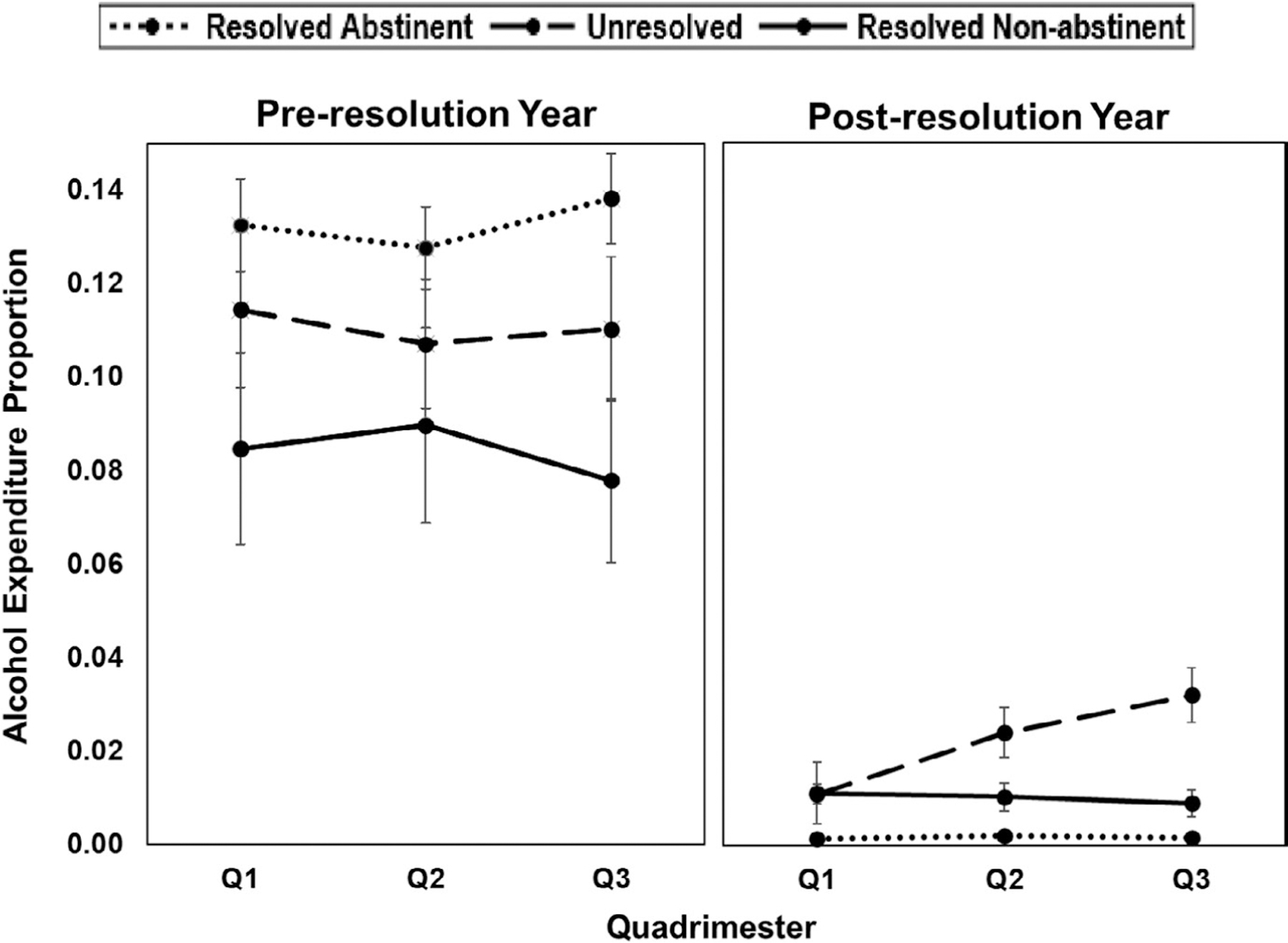

Figure 1 presents the proportion of dollars spent on alcohol relative to total expenditures during each quadrimester in the pre- and postresolution years as a function of 1-year drinking status. In the ANOVA that examined changes in proportional alcohol allocations, the group by time interaction effect was significant, F (2, 487) = 4.22, p < 0.05. As expected, all three groups showed significant decreases (p < 0.001) between the pre- and postresolution years, with the largest changes observed in the RA group. The UR and RNA groups showed similar changes from the pre- to postresolution year on average; however, the UR group showed an increasing trend in proportional alcohol spending during postresolution year, while the RNA group did not. These results indicate overall shifts in postresolution spending away from alcohol and suggest that the relative increase in expenditures for commodity categories other than alcohol may be differentially allocated to categories by different drinking groups.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of dollar amounts spent on alcohol relative to total expenditures during each quadrimester in the pre- and postresolution years as a function of 1-year drinking status. Quadrimesters (Q) are 4-month intervals during the pre- and postresolution year, and error bars show the standard error of the mean. Error bars for the RA group during the postresolution year are not visible due to the small standard errors of the means (0.004–0.005)

Longitudinal associations between postresolution spending and drinking outcomes

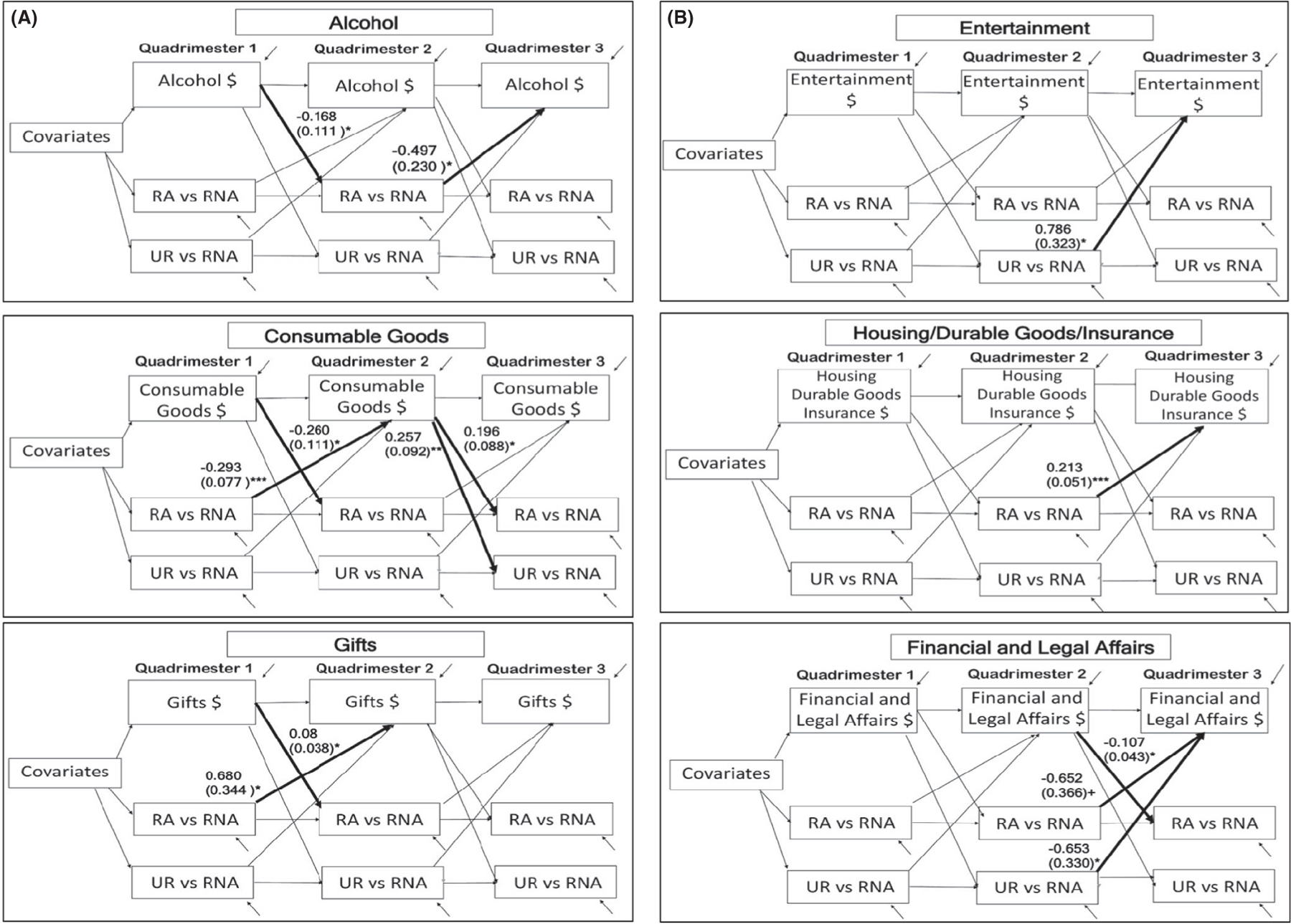

The first set of longitudinal analyses examined whether spending in any given quadrimester predicted terminal 1-year drinking status (Table 3). The second set of analyses with cross-lagged models examined relationships between time-specific drinking status and spending across quadrimesters intervals in the postresolution year. The main findings from the cross-lagged models are shown in Figure 2. Figure S2 displays the covariate-adjusted marginal means with error bars obtained in the cross-lagged models for each drinking status at each quadrimester.

TABLE 3.

Associations between quadrimester spending during the postresolution year and drinking outcomes at 1 year

| Postresolution year time period |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending categories | Comparisons among 1-year drinking outcome groups |

Quadrimester 1 B (SE) |

Quadrimester 2 B (SE) |

Quadrimester 3 B (SE) |

| Alcoholic beverages | RA vs. RNA | −0.111 (0.075) | 0.015 (0.166) | −0.406 (0.153)** |

| UR vs. RNA | −0.179 (0.143) | 0.265 (0.193) | 0.238 (0.127)+ | |

| Consumable goods | RA vs. RNA | 0.175 (0.121) | 0.226 (0.241) | −0.230 (0.142) |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.375 (0.113)** | −0.432 (0.338) | 0.390 (0.520) | |

| Gifts | RA vs. RNA | 0.073 (0.041)+ | 0.146 (0.030)*** | −0.033 (0.037) |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.120 (0.039)** | 0.043 (0.035) | −0.036 (0.025) | |

| Entertainment | RA vs. RNA | −0.095 (0.091) | −0.067 (0.095) | 0.178 (0.071)* |

| UR vs. RNA | −0.029 (0.072) | −0.271 (0.060)*** | 0.306 (0.067)*** | |

| Housing/durable goods/ insurance | RA vs. RNA | 0.426 (0.009)*** | −0.296 (0.094)** | −0.014 (0.090) |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.240 (0.097)* | −0.006 (0.128) | −0.316 (0.365) | |

| Financial/legal affairs | RA vs. RNA | 0.098 (0.047)* | 0.163 (0.064)* | −0.263 (0.090)** |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.077 (0.037)* | 0.099 (0.046)* | −0.232 (0.066)*** | |

| Health care | RA vs. RNA | 0.026 (0.079) | 0.052 (0.086) | −0.008 (0.087) |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.025 (0.074) | 0.092 (0.127) | −0.006 (0.118) | |

| Transportation | RA vs. RNA | 0.075 (0.029)* | −0.135 (0.213) | 0.205 (0.205) |

| UR vs. RNA | 0.124 (0.135) | −0.213 (0.135) | 0.148 (0.092) | |

Note: In the comparisons among 1-year drinking outcome groups, RNA (coded as 0) was the referent. Quadrimesters are 4-month intervals during the postresolution year (Q1 = months 1–4; Q2 = months 5–8 ; Q3 = months 9–12). The associations between 1-year drinking outcome groups and dollar amounts spent during quadrimesters were obtained adjusting for covariates listed in the Data Analysis section.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

FIGURE 2.

Cross-lagged models to examine time-specific relations between category expenditures and drinking status using lag-one relations from an earlier quadrimester (time t-1) to the next quadrimester (time t) across the postresolution year for commodity categories that showed significant change. Significant paths are shown in bold (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, +p < 0.10)

As shown in Table 3, significant associations that distinguished the outcome groups were found for alcoholic beverages, consumable goods, gifts, entertainment, housing/durable goods, and financial/legal affairs, which were further examined using cross-lagged models. No significant associations were observed for health care, and the one association observed for transportation disappeared in the cross-lagged model. Note that Table 3 shows the associations between spending patterns across the 3 quadrimesters and drinking outcomes at 1 year after resolution onset; they do not reflect associations between quadrimester-to-quadrimester changes in spending and drinking status, which were the focus of the cross-lagged models shown in Figure 2. The cross-lagged models helped identify when the postresolution patterns of association changed by examining relationships between spending during the previous quadrimester and drinking status in the next quadrimester and vice versa.

The 2 sets of models for alcohol spending provided a validity check on the 1-year drinking status classifications, with lower spending characteristic of the RA group. Among the other 5 commodity classes with significant postresolution associations, 4 classes (consumable goods, entertainment, financial/legal affairs, housing/durable goods/insurance) showed changes in the directionality of associations from earlier to later quadrimesters that distinguished the RNA group from the UR and/or RA groups. One class (gifts) showed differential associations earlier in the postresolution year only.

For consumable goods, the terminal UR group at 1 year spent more during the first quadrimester compared to the terminal RNA group. The cross-lagged models further showed that greater spending during the first and second quadrimesters was observed among the RNA than RA status group during the same periods. Then, greater spending during the second quadrimester predicted RA and UR status compared to RNA status during the final quadrimester. Thus, consumable goods spending was associated with RNA status early in the postresolution year, but the direction changed, with greater spending being more characteristic of RA and UR status later in the year.

For gifts, greater spending during the first quadrimester was observed in the terminal UR group compared to the terminal RNA group, and greater spending during the second quadrimester was observed for the terminal RA compared to terminal RNA group. The cross-lagged models showed that greater spending on gifts among the RA than RNA status group occurred during the first to the second quadrimesters. Thus, gift-giving during the early to mid-postresolution year was more characteristic of UR and especially RA drinking status compared to RNA status. For entertainment, greater spending during the second quadrimester was observed in the terminal RNA than UR group, whereas greater spending during the third quadrimester was observed in the terminal UR and RA groups than the terminal RNA group. The cross-lagged models showed a significant UR-RNA difference only between the second and third quadrimesters. Compared to the UR group during the second quadrimester, the RNA group spent less on entertainment during the final quadrimester.

The 2 largest expenditure categories for the sample as whole showed significant postresolution shifts that distinguished the terminal RNA outcome group. Spending on big ticket items (housing, durable goods, related insurance) showed directional changes during the postresolution year. Greater spending early in the year was more characteristic of the terminal RA and UR groups compared to the terminal RNA group. But greater spending mid-year was observed in the terminal RNA than RA group. The cross-lagged models further revealed that this mid-year association disappeared in the final quadrimester. Thus, participants with RNA outcomes spent relatively more mid-year on large, heretofore delayed rewards.

For financial/legal affairs, greater spending during the first and second quadrimesters was characteristic of the terminal RA and UR groups compared to the terminal RNA group. But the opposite association was found for the third quadrimester, with higher spending among the terminal RNA than terminal RA or UR groups. The cross-lagged models showed related dynamic changes during the second to third quadrimester, but not earlier in the year. Compared to spending by the UR status group during the second quadrimester, the RNA status group spent relatively more on financial/legal affairs during the third quadrimester. Greater spending during the second quadrimester also was observed among the RNA than RA status group during the third quadrimester. Thus, spending patterns of the RA and UR groups were similar and distinct from the RNA group both quadrimester-to-quadrimester and in relation to 1-year outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Dynamic changes in monetary allocation occurred during the postresolution year in multiple commodity classes. The overall expenditure patterns were consistent with study hypotheses that recovery from alcohol problems entails shifts in resource allocation away from drinking toward valuable delayed nondrinking rewards and that the shifts would distinguish among participants who maintained stable moderation compared to those who abstained or relapsed. The longitudinal analyses further indicated that, in general, the spending patterns of RNA participants differed both interval-to-interval and over the entire postresolution year from those of RA and UR participants, who were more similar to one another.

When considered with our earlier findings concerning drinking outcomes and preresolution expenditure patterns (e.g., Cheong et al., 2020; Tucker et al., 2009, 2016; Tucker, Cheong et al., 2020), the results indicated that the RNA group showed greater variability in spending patterns compared to other outcome groups during the 2 years surrounding initial resolution. Prior to resolution, their discretionary spending favored proportionately higher savings for the future than spending on alcohol compared to the RA and UR groups. By mid-year after initial resolution, however, their total spending was higher than the other outcome groups and had shifted in ways that entailed receipt of heretofore delayed large rewards (e.g., housing) that yield continued lifestyle benefits and involved some longer term financial commitments. Throughout the postresolution year, the RNA outcome group drank within a relatively tight band of limited drinking (Cheong et al., 2020), and their shifts in spending that were most distinguishing occurred after they had successfully limited their drinking for at least several months. Therefore, in line with the hypotheses, compared to the RA and UR outcome groups, the RNA group experienced higher value postresolution consumption bundles that should have served to reinforce and stabilize the shifted recovery behavior patterns while they engaged in some limited nonproblem drinking.

In contrast, the RA and UR outcome groups had similar and less valuable postresolution consumption bundles compared to the RNA group. They spent relatively less overall postresolution and had less variability in their spending patterns. They tended to spend on smaller rewards (e.g., consumable goods, entertainment, and gifts) throughout the postresolution year, appearing to substitute alcohol with small, frequent substance-free rewards, whereas the RNA group shifted spending mid-year to obtain large rewards with enduring benefits. There was one notable exception. Very high spending on consumable goods early in the postresolution year was a negative prognostic indictor associated with UR status at 1 year. Also, greater spending on financial and legal affairs was characteristic of UR and RA status earlier in the postresolution year, which is consistent with their relatively higher preresolution problem severity (see Table 1). But by mid-year and beyond, this expenditure pattern reversed, and greater financial and legal spending was associated with RNA status, which coincided with their relatively larger expenditures on housing, durable goods, and related insurance during that part of the year.

Study findings are consistent with Marlatt’s (1985) differential regulation hypothesis, framed here in behavioral economic terms, that the behavioral pathway to stable moderation is qualitatively different from the pathway to stable abstinence or relapse. In addition to the defining drinking practice differences among outcome groups, the moderation drinkers showed relatively more regulation of preresolution discretionary spending on alcohol and savings, but changed this pattern postresolution after some initial success with moderation in ways that provided receipt of large, delayed rewards. Thus, greater behavioral variability (flexibility) and its effective management appear to distinguish persons with AUD who can achieve stable moderation during a natural recovery attempt.

These results generally concur with long-term prospective studies of treatment and community samples of heavy drinkers that found positive drinking outcomes were accompanied by improved health, life satisfaction, and functioning (e.g., Moos & Moos, 2007; Witkiewitz, Pearson et al., 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2019), and they have potential implications for assessment and treatment. First, assessing how persons with substance use disorders spend their money on substances and other commodities has utility for predicting behavior change outcomes and thus may inform treatment goals. In addition to the present TLFB-based scheme, other brief measures of monetary allocation to alcohol or drugs found to predict treatment outcomes are available (Murphy et al., 2015; Worley et al., 2015). Second, monitoring spending patterns after initial resolution may be useful as part of expanding the variable domains considered important in broadened definitions of recovery that encompass life-health functioning in addition to drinking practices (Witkiewitz, Montes et al., 2020). Third, the present results provided support for interventions that seek to lengthen the time horizons for behavioral allocation (e.g., Snider et al., 2016; Tucker et al., 2012). Preliminary evidence suggests that such interventions promote drinking reductions generally (e.g., Murphy et al., 2019) and moderate drinking specifically (e.g., Tucker et al., 2012). Fourth, contrary to behavioral self-control programming, spending on small frequent rewards was not uniquely associated with stable resolution.

Several issues qualify the findings. First, the Project ARC data set consisted of 5 naturalistic observational studies. Although the prospective designs allowed evaluation of concurrent and sequential associations between drinking and expenditures and supported inferences about change mechanisms, the direction of causality cannot be firmly established. Second, conservative criteria were used to categorize participants who drank during the postresolution year that were in line with views about recovery and relapse when this research program was started. Thus, the unstable resolution group is likely heterogeneous in ways that merit investigation given newer findings showing that some heavy drinkers previously considered treatment failures were improved and functioning well (e.g., Witkiewitz, Pearson et al., 2020; Witkiewitz et al., 2019). Third, although meaningful regularities in drinking-expenditure associations were observed in line with the hypotheses after controlling for multiple covariates that influenced the associations, the possibility remains that expenditure patterns may have been influenced by variables not measured or controlled for in this research. Fourth, research is needed to investigate whether the present findings generalize to samples with more heterogeneous problem severity, help-seeking histories, and personal economies. Fifth, the 5 studies comprising the integrated data set were conducted over a 23-year period. Although expenditure reports were inflation-adjusted, there almost certainly were unmeasured economic and other contextual changes during this time span that could have affected individuals’ expenditure patterns. Nevertheless, earlier analyses conducted soon after data collection ended in each of the five studies yielded results that are generally in line with the integrated data set findings, which suggests that cohort or time trend effects are not a significant concern. Finally, although different levels of drinking, including any drinking, are associated with some longer term health risks, the substantial drinking reductions achieved by the RNA group fell well within the lower end of the continuum of relative health risk established in a large systematic analysis of the global burden of disease associated with alcohol (GBD, 2016 Alcohol Collaborators, 2018; see figure 5). The drinking reductions coupled with the absence of alcohol-related functional problems among the RNA group should not be trivialized because of longstanding debate about the role of abstinence in recovery.

In conclusion, study findings using a large natural recovery sample replicated and extended Marlatt’s (1985) differential regulation hypothesis framed in behavioral economic terms and revealed multidimensional contextual and monetary allocation patterns favorable and unfavorable to recovery, with emphasis on stable moderation. Focusing on molar financial changes in participants’ personal economies showed the embeddedness of heavy drinking and recovery processes and outcomes in multiple areas of functioning using a common metric (money) and added to evidence that monetary allocation to substances predicts outcomes of recovery attempts. The research highlights the usefulness of the behavioral economic focus on behavioral patterning and context dependence of choices over lengthy time intervals in understanding AUD recovery and added new knowledge about the multidimensional contexts that promote and sustain it.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Portions of this research were presented at the August 2019 annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA, and the September 2020 Recovery from Alcohol Use Disorder: A Virtual Roundtable Discussion of a New NIAAA Research Definition held by the National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism. The authors thank Eun-Young Mun for her expert consultation on integrating the data sets used in this research, Akshay A. Sawant for performing inflation adjustments of monetary variables, and Joseph P. Bacon, Brice H. Lambert, and Soyeon Jung for assistance with data management and analysis. The research was supported in part by NIH/NIAAA grants R01 AA08972, R01 AA017880, and R01 AA023657.

Funding information

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant/Award Number: R01 AA017880, R01 AA023657 and R01 AA08972

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- Acuff SF, Dennhardt AA, Correia CJ & Murphy JG (2019) Measurement of substance-free reinforcement in addiction: a systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH (2018) Individual decision-making in the causal pathway to addiction: contributions and limitations of rodent models. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 164, 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2004) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J & Murphy JG (2014) The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 641–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahalan D. (1970) Problem drinkers: A national survey. San Francisco: Josey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME (1993) The economic context of drug and nondrug reinforcers affects acquisition and maintenance of drug-reinforced behavior and withdrawal. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 33, 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong J, Lindstrom K, Chandler SD & Tucker JA (2020) Utility of different dimensional properties of drinking practices to predict stable low-risk drinking outcomes of natural recovery attempts. Addictive Behaviors, 106, 106837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ & Hussong AM (2009) Integrative data analysis: the simultaneous analysis of multiple data sets. Psychological Methods, 14, 81–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daughters SB, Magidson JF, Anand D, Seitz-Brown CJ, Chen Y & Baker S. (2018) The effect of a behavioral activation treatment for substance use on post-treatment abstinence: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 113, 535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D, Wang XQ, Liu L, Fertig J, Mattson M, Ryan M. et al. (2010) Percentage of subjects with no heavy drinking days: evaluation as an efficacy endpoint for alcohol clinical trials. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 2022–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AZ, Chou P, Zhang H, Jung J & Grant BF (2019) Prevalence and correlates of past year recovery from DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions - III. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43, 2406–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. (2018) Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet, 392, 1015–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S & Schaub MP (2016) Treatment outcome, treatment retention, and their predictors among clients of five outpatient alcohol treatment centres in Switzerland. BMC Public Health, 16, 581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrnstein RJ (1974) Formal properties of the matching law. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 21, 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt GM & Azrin NH (1973) A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 11, 91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner B, Sout RL & Pagano M. (2012) Determining the relative importance of the mechanisms of behavior change within Alcoholics Anonymous: A multiple mediator analysis. Addiction, 107, 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingemann H & Sobell LC (Eds.) (2007) Promoting self-change from addictive behaviors: Practical implications for policy, prevention, and treatment. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman P & Wells R. (2012) Economics and microeconomics, 3rd edition. New York: Worth Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA (1985) Lifestyle modification. In: Marlatt GA & Gordon JR (Eds.) Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford, pp. 280–318. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH & Moos BS (2007) Protective resources and long-term recovery from alcohol use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 86, 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Yurasek AM, Skidmore JR, MacKillop J. et al. (2015) Behavioral economic predictors of brief alcohol intervention outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 1033–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Martens MP, Borsari BE, Witkiewitz K & Meshasha LZ (2019) Randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a brief alcohol intervention supplemented with a substance-free activity session or relaxation training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87, 657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO (1998–2017) MPlus users guide, 8th edition. Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2005) Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. NIAAA, Rockville, MD. Available at: https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2020) Drinking levels defined. NIAAA, Rockville, MD. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking. Accessed January 5, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Battalio R, Kagel J & Green L. (1981) Maximization theory in behavioral psychology. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 4, 371–388. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H & Laibson D (Eds.) (1997) The Matching Law: Papers on Psychology and Economics by Richard Herrnstein. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML (1971) The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test: The quest for a new diagnostic instrument. American Journal of Psychiatry, 127, 1653–1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA & Horn JL (1984) Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) Users’ Guide. Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, LaConte SM & Bickel WK (2016) Episodic future thinking: Expansion of the temporal window in individuals with alcohol dependence. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40, 1558–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LA, Cunningham JA & Sobell MB (1996) Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: Prevalence in two population surveys. American Journal of Public Health, 86, 966–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC & Sobell MB (1992) Timeline follow-back: a technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R & Allen JR (Eds.) Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. Towata, NJ: Humana Press, pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB & Toneatto T. (1992) Recovery from alcohol problems without treatment. In: Heather N, Miller WR & Greeley J (Eds.) Self-control and addictive behaviors. New York: Macmillan, pp. 198–242. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Chandler SD & Witkiewitz K. (2020) Epidemiology of recovery from alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Cheong J, Chandler SD, Lambert BH, Pietrzak B, Kwok H & Davies S. (2016) Prospective analysis of behavioral economic predictors of stable moderation drinking among problem drinkers attempting natural recovery. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40, 2676–2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Cheong J, James TG, Hung S & Chandler SD (2020) Pre-resolution drinking problem severity profiles associated with stable moderation outcomes of natural recovery attempts. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44, 738–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Foushee HR, Black BC & Roth DL (2007) Agreement between prospective IVR self-monitoring and structured retrospective reports of drinking and contextual variables during natural resolution attempts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Foushee HR & Black B. (2008) Behavioral economic analysis of natural resolution of drinking problems using IVR self-monitoring. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 16, 332–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Roth DL, Vignolo M & Westfall AO (2009) A behavioral economic reward index predicts drinking resolutions: moderation re-visited and compared with other outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Roth DL, Huang J, Crawford MS & Simpson CA (2012) Effects of interactive voice response self-monitoring on natural resolution of drinking problems: Utilization and behavioral economic factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73, 686–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA & Simpson CA (2011) The recovery spectrum: From self-change to seeking treatment. Alcohol Research & Health, 33, 371–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE & Rippens PD (2002) Predicting natural resolution of alcohol-related problems: a prospective behavioral economic analysis. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 10, 248–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Black BC & Rippens PD (2006) Significance of a behavioral economic index of reward value in predicting problem drinking resolutions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC & Vandenbroucke JP (2007) STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology, 18, 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE & Heather N. (2003) Choice, behavioural economics and addiction. In: Vuchinich RE & Heather N (Eds.) Choice, behavioural economics and addiction. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Ltd, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE & Tucker JA (1988) Contributions from behavioral theories of choice to an analysis of alcohol abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 97, 181–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA & Harllee L. (1988) Behavioral assessment. In: Donovan DM & Marlatt GA (Eds.) Assessment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford, pp. 51–93. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE & Tucker JA (1996) Life events, alcoholic relapse, and behavioral theories of choice: a prospective analysis. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 4, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Finney JW, Harris AHS, Kivlahan DR & Kranzler HR (2015) Guidelines for the reporting of treatment trials for alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 39, 1571–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Montes KS, Schwebel FJ & Tucker JA (2020) What is recovery? Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 40, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Pearson MR, Wilson AD, Stein ER, Votaw VR, Hallgren KA et al. (2020) Can alcohol use disorder recovery include some heavy drinking? A replication and extension up to nine years following treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44, 1862–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Wilson AD, Pearson MR, Montes KS, Kirouac M, Roos C. et al. (2019) Profiles of recovery from alcohol use disorder at three years following treatment: Can the definition of recovery be extended to include high functioning heavy drinkers? Addiction, 114, 69–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley MJ, Shoptaw SJ, Bickel WK & Ling W. (2015) Using behavioral economics to predict opioid use during prescription opioid dependence treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 148, 62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.