Abstract

Objective:

To characterize patterns of weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) among US undergraduate and graduate students and examine associations between identified patterns of WRSM and eating disorder symptomology.

Methods:

Undergraduate and graduate students from 12 US colleges and universities (N=10,010) reported the frequency with which they use WRSM, including self-weighing and dietary self-monitoring. Eating disorder symptomology was assessed using the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire. Gender-specific patterns of WRSM were identified using latent class analysis, and logistic regressions were used to identify differences in the odds of eating disorder symptomology across patterns of WRSM.

Results:

Among this sample, 32.7% weighed themselves regularly; 44.1% reported knowing the nutrition facts of the foods they ate; 33.6% reported knowing the caloric content of the foods they ate; and 12.8% counted the calories they ate. Among women, four patterns of WRSM were identified: “no WRSM,” “all forms of WRSM,” “knowing nutrition/calorie facts,” and “self-weigh only.” Compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, women in all other patterns experienced increased eating disorder symptomology. Among men, three patterns were identified: “no WRSM,” “all forms of WRSM,” and “knowing nutrition/calorie facts.” Only men in the “all forms WRSM” pattern had increased eating disorder symptomatology compared to those in the “no WRSM” pattern.

Discussion:

In a large sample of undergraduate and graduate students, engaging in any WRSM was associated with increased eating disorder symptomology among women, particularly for those who engaged in all forms. Among men, engaging in all forms of WRSM was the only pattern associated with higher eating disorder symptomology.

Keywords: eating disorders, disordered eating, public health, nutritional sciences, college health, prevention, self-weighing, self-monitoring

Introduction

The reported prevalence of eating disorders has increased over time (Galmiche, Déchelotte, Lambert, & Tavolacci, 2019). The college years are a particularly vulnerable period, as they typically coincide with the mean age of onset for eating disorders (Hudson, Hiripi, Pope, & Kessler, 2007; Swanson, Crow, Le Grange, Swendsen, & Merikangas, 2011). An estimated 8–23% of college students struggle with a full-syndrome eating disorder (Eisenberg, Nicklett, Roeder, & Kirz, 2011; Hoerr, Bokram, Lugo, Bivins, & Keast, 2002; Phillips et al., 2015; Tavolacci et al., 2015), making the prevention and treatment of eating disorders on college campuses an important public health issue.

Weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) has been suggested as a modifiable risk factor for eating disorders. WRSM involves tracking one’s weight (i.e., self-weighing) or behaviors that affect weight, such as dietary intake. WRSM can involve physically tracking (e.g., recording in a journal or entering information into a smartphone application) or cognitively tracking (e.g., keeping count or remembering in one’s head). Approximately 30–35% of college students engage in self-weighing at least once per week (Gunnare, Silliman, & Morris, 2013; Klos, Esser, & Kessler, 2012) and 14% report using a calorie counting device or smart phone application (Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017). Among populations vulnerable to eating disorders, increased attention to food and weight may lead to a pathological obsession with these behaviors (Neumark-Sztainer, van den Berg, Hannan, & Story, 2006). It has been shown that more self-weighing in adolescence is longitudinally associated with an increased likelihood of disordered eating in young adulthood, even when adjusting for baseline disordered eating (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006). Further, college-age individuals who engage in self-weighing are more likely to experience heightened eating disorder symptomology (Walsh & Charlton, 2014), weight preoccupation (Klos et al., 2012), and body dissatisfaction compared to those who do not weigh themselves (Mercurio & Rima, 2011; V. Quick, Larson, Eisenberg, Hannan, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2012). Calorie counting is also cross-sectionally associated with eating concern, dietary restraint (Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017), and increased eating disorder symptomology (Romano, Swanbrow Becker, Colgary, & Magnuson, 2018) among college students.

Despite this evidence, it is unknown whether more passive forms of WRSM, such as knowing the nutrient or caloric content of foods, are similarly indicative of eating disorder cognitions or behaviors. Further, WRSM behaviors have been studied exclusive to one another despite the fact that they commonly co-occur (Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017). Specific forms of WRSM may interact with one other and associate with higher eating disorder symptomology relative to single behaviors.

Given these gaps in our understanding of WRSM among college students, the objectives of the present study were to 1) characterize the patterns of undergraduate and graduate students’ use of dietary self-monitoring and self-weighing using latent class analysis (LCA), and 2) to examine the associations between identified patterns of WRSM and eating disorder symptomology among this population. Study findings could help inform targeted and universal eating disorders prevention or treatment activities on college campuses.

Methods

Participants

Data were collected as part of the Healthy Bodies Study (HBS). HBS surveyed students from 12 two- and four-year colleges and universities in the US during the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 school years with the goal of identifying the prevalence and correlates of eating disorder symptomology among undergraduate and graduate students. Institutions were recruited to participate by email, contact at academic conferences, and by institutions contacting the study team themselves. The study survey was electronically distributed to a randomly selected sample of up to 4,000 undergraduate and/or graduate students at each participating institution. The random sample was selected using the registrars at participating institutions, allowing all students who were at least 18 years of age to be eligible for random selection. In total, across the twelve participating schools, 10,209 students completed the HBS survey corresponding to response rates of 19% and 27% for the respective academic years. No students were sent the survey both years if institutions participated more than one year. Students were asked to self-report their height and weight, from which body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Students with biologically implausible weight, height, BMI, or age (n=73) were excluded from the analytic sample (Li et al., 2009; Noel et al., 2010; Noel et al., 2012). Students who identified as a gender minority (transgender, genderqueer/gender non-conforming, or other) or did not specify their gender were also excluded from analyses as there were too few students to make gender specific inferences (n=123), resulting in a final analytic sample of 10,010 students. Research approval was obtained by the Institutional Review Boards at participating institutions.

Measures

Weight-Related Self-Monitoring (WRSM).

Dietary self-monitoring was assessed using three survey items: “How often do you typically know the nutrition facts (for example, fat, fiber, carbohydrates, protein) about the foods and drinks you consume before you consume them?”, “How often do you typically know the number of calories in the foods and drinks that you consume before you consume them?”, and “How often do you count the calories that you consume?”. Response options for all three questions were: “always”, “usually”, “sometimes”, “rarely” and “never.” Each form of dietary self-monitoring was dichotomized with those answering “always” or “usually” considered positive for the respective type of dietary self-monitoring. This dichotomy was selected based on the standard in assessing the use of nutrition label use, with similar prevalences to our own independent constructs (Christoph & Ellison, 2017; Christoph, Larson, Laska, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2018; Cooke & Papadaki, 2014; Graham & Laska, 2012). Self-weighing was assessed using a single item, “About how often do you weigh yourself?” with response options of: “Never”, “Less than once per month”, “2 to 3 times per month”, “once per week”, “2 to 3 times per week”, “4 to 6 times per week”, “once per day” and, “more than once per day.” Because of the variability in the relationship between self-weighing frequency, recommendations, and eating disorder symptomology, we used a data driven approach to select a dichotomy for weighing frequency by conducting latent class analyses with various empirically derived cut-points (Jensen et al., 2014; Pacanowski, Crosby, & Grilo, 2019; Pacanowski, Linde, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2015). Ultimately, the best models included a cut-off of more than once per week.

Eating Disorder Symptomology.

Eating disorder symptomology was assessed using the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) 6.0 (C.G. Fairburn & Beglin, 2008) with an EDE-Q global score ≥ 4 considered clinically significant eating disorder symptomology. A cut-off of 4 is considered clinically significant in the literature, is approximately the average of treatment seeking samples, and corresponds to over the 90th percentile of the general college population (Aardoom, Dingemans, Slof Op’t Landt, & Van Furth, 2012; C. G. Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; V. M. Quick & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2013; Ro, Reas, & Stedal, 2015). Specific eating disorder behaviors for weight or shape control were assessed by the EDE-Q including fasting (8 or more waking hours without eating), vomiting to compensate, taking diet pills or diuretics, abusing laxatives, and compulsively exercising, with any use of the behavior categorized as a positive response. Vomiting, diet pills/diuretics, laxatives, and compulsive exercise were combined into a single compulsive behavior variable. Binge eating was assessed using two items, “Over the past 28 days, how many times have you eaten what other people would regard as an unusually large amount of food (given the circumstances)?” and “. …On how many of these times did you have a sense of having lost control over your eating (at the time that you were eating)?” Those who reported at least one time for both questions were characterized as having engaged in binge eating.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Body Mass Index.

Participants self-reported their sociodemographic characteristics, height, and weight. Gender was assed via the question, “What is your gender identity”, with the response options: “female”, “male”, “transgender female-to-male”, “transgender male-to-female”, “genderqueer/gender non-conforming”, and “other.” Gender was then dichotomized to women and men based on the response options and gender minorities were excluded. BMI was calculated using self-reported height and weight and was operationalized as a categorical variable (weight status) as guidelines related to the use of WRSM differ by BMI category (Jensen et al., 2014) and was utilized as a continuous variable to increase precision in models.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate statistics were computed for WRSM and gender. Gender-stratified LCA using all four forms of WRSM was then used to identify gender-specific WRSM patterns. Because the seed in PROC LCA (Lanza, Collins, Lemmon, & Schafer, 2007) can alter results, ten seeds were ran with two through six classes for both genders using randomly generated seed numbers that remained consistent for both genders. For each analysis, the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC), Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and interpretability were used to select the best fitting models (Lanza et al., 2007).

After identifying the patterns of WRSM, chi-square, Fisher’s exact tests, and ANOVA were used to determine if there were differences in sociodemographic variables across identified patterns of WRSM. If overall tests of differences were statistically significant at p<.05, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted between identified patterns of WRSM using logistic regression for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. To reduce likelihood of Type 1 error due to multiple comparisons, post-hoc results were considered significant if p<.01,

Gender-specific logistic regression models were then used to examine associations between the identified WRSM patterns, global eating disorder symptomology as measured by the EDE-Q, and individual eating disorder behaviors. Adjusted models included age, race/ethnicity, parental education and BMI because they are all known to be associated with eating disorder symptomology (Eisenberg et al., 2011; Goodman, Heshmati, & Koupil, 2014; Hoerr et al., 2002; Lavender, De Young, & Anderson, 2010; Lipson & Sonneville, 2017). The odds ratios (OR) with 99% confidence intervals (CI) of eating disorder symptomology was calculated for members of each identified pattern of WRSM. Pairwise comparisons were also conducted from the adjusted models and differences between classes other than the reference were considered statistically significant if p<.01. Analyses corrected for non-response to the original survey using response probability weights which allows for generalizability of the findings to the sample the survey was sent to, and thus the entire university, versus only the sample that responded to the survey. Response probability weights were calculated using gender, race/ethnicity, and academic level and grade point average obtained from school records. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Description of the Study Sample

The weighted sample was 55.1% women and 44.9% men (Table 1). Approximately two thirds (66.9%) of participants identified as non-Hispanic White, 4.4% as African American, 9.3% as Hispanic or Latinx, 11.4% as Asian, and 7.9% as another racial/ethnic identity. Ten percent (10.1%) of students had parents with a high school diploma or less, 17.2% had some college or an associate’s degree, 30.3% had a bachelor’s degree, and 42.5% had a graduate degree. The average BMI was 24.0 (standard error (SE)=0.1), with 4.4% having a BMI less than 18.5, 64.1% having a BMI of at least 18.5 but less than 25, 22.1% had a BMI of at least 25 but less than 30, and 9.3% having a BMI of 30 or higher. The average age of the sample was 23.9 years old (SE=0.1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample overall and by gender

| Overall (n=10,010) | Women (n=6,961) | Men (n=3,049) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Weighted Prevalence (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White | 66.9 | 67.5 | 66.2 |

| Black or African American | 4.4 | 4.6 | 4.3 |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.0 |

| Asian | 11.4 | 10.2 | 12.8 |

| Other | 7.9 | 8.1 | 7.7 |

| Parent Education | |||

| High school or less | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.0 |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 17.2 | 19.1 | 14.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.3 | 30.0 | 30.6 |

| Graduate degree | 42.5 | 40.8 | 44.5 |

| BMI Category | |||

| <18.5 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 2.4 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 64.1 | 67.1 | 60.4 |

| 25–29.9 | 22.1 | 18.0 | 27.1 |

| ≥30.0 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 10.1 |

|

| |||

| Mean (Standard Error) | |||

|

| |||

| BMI | 24.0 (0.1) | 23.6 (0.1) | 24.6 (0.1) |

| Age (years) | 23.9 (0.1) | 23.7 (0.1) | 24.4 (0.1) |

A similar proportion of women and men in this sample of students reported knowing the nutrition facts of the foods they ate (44.8% of women and 43.3% of men). More women (35.7%) than men (31.1%) knew the calories in the food they consumed (p <.0001); women were also more likely to count calories than men (14.8% versus 10.4%, p<.0001). However, there were no differences in self-weighing prevalence among men and women (21.4% vs 20.0%, p=.15).

Latent Class Analysis and Sociodemographic Characteristics by Latent Class

Women.

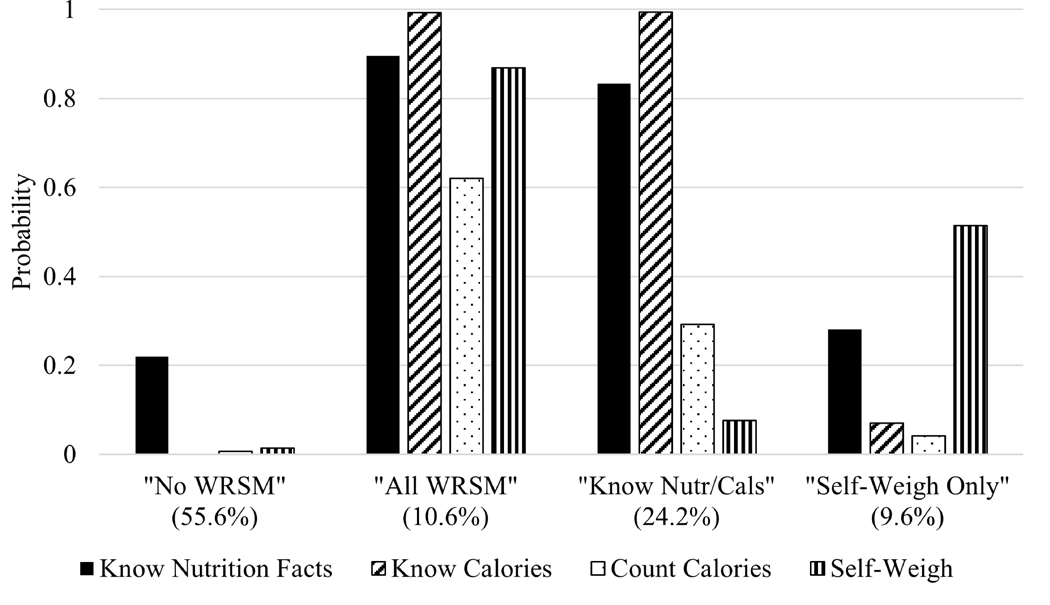

A model with four latent classes was deemed to be the superior model. For women, Latent Class 1 was characterized by low likelihood of engaging in any form of WRSM (identified as “no WRSM”) and comprised 55.6% of the sample (Figure 1). Latent Class 2 was characterized by high likelihood of all forms of included WRSM (identified as “all WRSM”) and comprised 10.6% of the sample. Latent Class 3 was characterized by high likelihood of knowing nutrition facts and knowing calories (identified as “knowing nutrition/calorie facts”) and comprised 24.2% of the sample. Latent Class 4 was characterized by high likelihood of self-weighing but low likelihood of all forms of dietary self-monitoring (identified as “self-weighing only”) and comprised 9.6% of the sample. There were no differences in membership in the patterns by parental education but there were differences in race/ethnicity (p=.0009), BMI (ps<.0001) and age (p<.0001) (Table 2). Differences by race/ethnicity appeared to be driven by participants identified as Asian, who were more likely to be in the “self-weighing only” pattern compared to the “no WRSM” and “knowing nutrition/calorie facts” classes. Individuals in the “no WRSM” pattern had lower BMI and were younger compared to the individuals who did self-monitor.

Figure 1.

Probability estimates of each type of weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) for each latent class/identified pattern of WRSM for women

Table 2.

Overall weighted prevalence and bivariate analyses between demographics and identified patterns of weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) among women†

| Demographic | Overall | “No WRSM” | “All WRSM” | “Know Nutrition/Calorie Facts” | “Self-weighing only” | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Weighted Prevalence (%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall prevalence | . | 55.6 | 10.6 | 24.2 | 9.6 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | .0009 | |||||

| White | 67.5 | 66.3a | 69.1a | 70.2a | 66.1a | |

| Black or African American | 4.6 | 5.4a | 3.9a | 3.6a | 3.1a | |

| Hispanic/Latina | 9.6 | 10.1a | 8.1a | 9.8a | 8.3a | |

| Asian | 10.2 | 10.1a | 10.4a,b | 8.4a | 15.5b | |

| Other | 8.1 | 8.1a | 8.6a | 8.1a | 7.0a | |

| Parent Education | .46 | |||||

| High school or less | 10.1 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 10.1 | |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 19.1 | 19.3 | 17.4 | 20.3 | 16.2 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.0 | 30.7 | 28.8 | 28.8 | 30.4 | |

| Graduate degree | 40.8 | 39.9 | 43.3 | 41.0 | 43.3 | |

| BMI Category | <.0001 | |||||

| <18.5 | 6.1 | 7.6a | 4.9a,b | 3.7b | 4.5b | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 67.1 | 67.9a | 63.6a | 66.6a | 67.6a | |

| 25–29.9 | 18.0 | 16.4a | 20.9b | 20.9b | 17.4a,b | |

| ≥30.0 | 8.8 | 8.1a | 10.6a | 8.8a | 10.5a | |

|

| ||||||

| Mean (Standard Error) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| BMI, mean (SE) | 23.6 (0.1) | 23.3 (0.1)a | 24.1 (0.2)b | 23.9 (0.1)b | 23.9 (0.2)b | <.0001 |

| Age, mean (SE) | 23.1 (0.1) | 22.7 (0.1)a | 24.1 (0.2)b | 23.2 (0.2)c | 24.2 (0.3)b | <.0001 |

Superscripts are the result of pairwise comparisons of proportions across latent classes within row with p<.01; the same letter indicates lack of statistical difference between prevalences.

Men.

A model with three latent classes was deemed superior. In the patterns identified using LCA, Latent Class 1 was characterized by low probability of all WRSM behaviors (identified as “no WRSM”) and constituted 52.2% of the sample (Figure 2); Latent Class 2 was characterized by high probability of all included forms of WRSM (identified as “all WRSM”) and constituted 9.9% of the sample, and Latent Class 3 was characterized by high probability of knowing nutrition facts and knowing calories, but low probability of frequent self-weighing and calorie counting (identified as “know nutrition/calorie facts”), and constituted 37.9% of the sample. Results from the bivariate analyses among men are shown in Table 3. There were no differences in pattern membership by parental education (p=.16). However, there was an overall difference by race/ethnicity (p=.0497) and pairwise comparisons indicated that differences appeared to be driven by Asian participants who were more likely to belong to the “all WRSM” pattern compared to the “know nutrition/calorie facts” pattern. Those in the “no WRSM” pattern had a lower BMI than the “all WRSM” and “know nutrition/calorie facts” patterns (p=.0005). Mean age also differed across the identified patterns (p=.0001) with individuals who engaged in WRSM having a higher age on average than those in the “no WRSM” pattern.

Figure 2.

Probability estimates of each type of weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) for each latent class/identified pattern of WRSM for men

Table 3.

Overall weighted prevalence and bivariate analyses between demographics and identified patterns of weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) among men†

| Demographic | Overall | “No WRSM” | “All WRSM” | “Know Nutrition/ Calorie Facts” | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Weighted Prevalence (%) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Overall prevalence | 52.2 | 9.9 | 37.9 | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 66.2 | 65.5a | 61.5a | 68.4a | .0497 |

| Black or African American | 4.3 | 5.2a | 3.4a | 3.4a | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9.0 | 9.3a | 6.7a | 9.2a | |

| Asian | 12.8 | 12.9a,b | 18.9b | 11.1a | |

| Other | 7.7 | 7.2a | 9.6a | 8.0a | |

| Parent Education | .16 | ||||

| High school or less | 10.0 | 9.0 | 13.7 | 10.4 | |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 14.9 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 16.0 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 30.6 | 32.1 | 32.0 | 28.2 | |

| Graduate degree | 44.5 | 44.6 | 40.3 | 45.4 | |

| BMI Category | <.0001 | ||||

| <18.5 | 2.4 | 3.2a | 0.3b | 1.8a,b | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 60.4 | 65.0a | 45.9b | 58.0c | |

| 25–29.9 | 27.1 | 22.2a | 39.3b | 30.7b | |

| ≥30.0 | 10.1 | 9.6a | 14.5a | 9.6a | |

|

| |||||

| Mean (Standard Error) | |||||

|

| |||||

| BMI, mean (SE) | 24.0 (0.1) | 24.2 (0.1)a | 25.7 (0.3)b | 24.8 (0.1)c | .0005 |

| Age, mean (SE) | 23.4 (0.1) | 23.3 (0.1)a | 23.6 (0.3)a,b | 24.2 (0.2)b | .0001 |

Superscripts are the result of pairwise comparisons of proportions across latent classes within row with p<.01; the same letter indicates lack of statistical difference between prevalences.

Logistic Regression Results between Identified WRSM Patterns and Eating Disorder Symptomology

Women.

Compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, the odds of having an EDE-Q ≥ 4 was 13.64 times higher for those in the “all WRSM” pattern (99% CI: 8.53, 21.83), 5.40 times higher (99% CI: 3.45, 8.44) for those in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” pattern, and 4.36 times higher for those in the “self-weigh only” pattern (Table 4). Compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, the odds of fasting was highest in the “all WRSM” pattern (OR=4.19, 99% CI: 3.20, 5.48), followed by the “know nutrition/calorie facts” (OR=1.91, 99% CI: 1.52, 2.41) and “self-weigh only” (OR=2.32, 99% CI: 1.71, 3.14) patterns. The odds of using a compensatory behavior was 5.00 times higher (99% CI: 3.90, 6.42) for those in the “all WRSM” pattern compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, and 2.39 times higher (99% CI: 1.96, 2.90) and 2.05 times higher (99% CI: 1.56, 2.69) for the “know nutrition/calorie facts” and “self-weigh only” patterns, respectively. Finally, compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, the odds of binge eating was highest among the “all WRSM” class (OR=2.99, 99% CI: 2.34, 8.38), and also elevated in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” pattern (OR=1.83, 99% CI: 1.52, 2.22) and “self-weigh only” pattern (OR=1.80, 99% CI: 1.38, 2.34). For all outcomes, there was no statistical difference between those in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” and “self-weigh only” patterns, though the odds of each outcome was significantly lower in these patterns than the “all WRSM” pattern, and higher than the “no WRSM” pattern.

Table 4.

Odds ratio and 99% confidence interval of eating disorder risk by weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) pattern among women†

| EDE-Q ≥ 4‡ | Fasted | Compensatory Behavior | Binge Eating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| “No WRSM” | Refa | Refa | Refa | Refa |

| “All WRSM” | 13.64 (8.53, 21.83)b | 4.19 (3.20, 5.48)b | 5.00 (3.90, 6.42)b | 2.99 (2.34, 3.83)b |

| “Know Nutrition/Calorie Facts” | 5.40 (3.45, 8.44)c | 1.91 (1.52, 2.41)c | 2.39 (1.96, 2.90)c | 1.83 (1.52, 2.22)c |

| “Self-Weigh Only” | 4.36 (2.43, 7.81)c | 2.32 (1.71, 3.14)c | 2.05 (1.56, 2.69)c | 1.80 (1.38, 2.34)c |

Superscripts are the result of pairwise comparisons of within column; differing superscript letters represent statistically significant differences between the probability estimates at p<.01. Models included age, BMI, parent education, and race/ethnicity as covariates.

EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (C.G. Fairburn & Beglin, 2008).

Men.

Compared to the “no WRSM” class, those in the “all WRSM” pattern had increased odds of all measures of eating disorder symptomology (Table 5). Meanwhile, for those in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” pattern, there was no increased odds of having an EDE-Q ≥ 4, fasting, or binge eating. However, those in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” had increased odds (OR=1.61. 99% CI: 1.22, 2.12) of using a compensatory behavior compared to the “no WRSM” pattern, though the likelihood of using a compensatory behavior was lower in the “know nutrition/calorie facts” pattern compared to the “all WRSM” pattern.

Table 5.

Odds ratio and 99% confidence interval of eating disorder risk by weight-related self-monitoring (WRSM) pattern among men†

| EDE-Q ≥ 4‡ | Fasted | Compensatory Behavior | Binge Eating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| “No WRSM” | Refa | Refa | Refa | Refa |

| “All WRSM” | 4.08 (1.33, 12.54)b | 2.21 (1.35, 3.63)b | 3.15 (2.09, 4.76)b | 2.13 (1.37, 3.31)b |

| “Know Nutrition/Calorie Facts” | 0.71 (0.21, 2.37)a | 1.32 (0.92, 1.89)a | 1.61 (1.22, 2.12)c | 1.19 (0.88, 1.62)a |

Superscripts are the result of pairwise comparisons of within column; differing superscript letters represent statistically significant differences between the probability estimates at p<.01. Models included age, BMI, parent education, and race/ethnicity as covariates.

EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (C.G. Fairburn & Beglin, 2008).

Discussion

In this large study of undergraduate and graduate students from across the US, WRSM was common, many students used a combination of WRSM behaviors, and patterns of use of WRSM differed by gender. Further, those who engaged in WRSM had a higher average BMI and were older compared to those who did not use WRSM. Among women, engaging in any WRSM was cross-sectionally associated with increased eating disorder symptomology. Among men, engaging in all forms of WRSM was also associated with increased eating disorder symptomology compared to other patterns of WRSM.

Our findings align with previous research documenting that WRSM is common among college students, emphasizing the importance of understanding potential consequences and correlates of WRSM (Graham & Laska, 2012; Gunnare et al., 2013; Klos et al., 2012; Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017). Similar to previous studies, we found self-weighing (Ogden & Whyman, 1997; Pacanowski, Loth, Hannan, Linde, & Neumark-Sztainer, 2015) and calorie counting (Romano et al., 2018; Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017) were associated with increased eating disorder symptomology among our sample of college students. In addition to calorie counting, we also found increased symptomology for more passive forms of dietary self-monitoring. Knowing nutrition facts and knowing calorie facts were more common than calorie counting, but to our knowledge these measures have not been previously studied in this population. Building off work done by Simpson and Mazzeo, we also found that students often used more than one form of WRSM. We were able to identify unique patterns of use (e.g. knowing nutrition facts/calories), providing insight into how these behaviors are used in this population and how diverse patterns of use are associated with eating disorder symptomology (Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017). Additionally, we identified differences in use of WRSM by BMI, as has been shown for singular behaviors like calorie counting (Plateau, Bone, Lanning, & Meyer, 2018; Romano et al., 2018). Observed differences in WRSM by BMI was not unexpected as individuals with higher BMIs are more likely to be trying to lose weight (Malinauskas, Raedeke, Aeby, Smith, & Dallas, 2006) and WRSM is considered an integral part of behavioral weight management interventions (Jensen et al., 2014). Though WRSM is more common in women than men, a significant portion of men were engaging in WRSM and those that were engaging in all forms had substantially increased eating disorder symptomology. Interestingly, more passive forms of WRSM among men, may not be harmful or signify harm unless used in conjunction with more active forms. These findings provide valuable insight into eating disorder symptomology for men, who are understudied in eating disorders research (Murray, Griffiths, & Mond, 2016).

In the current study, individuals who engaged in multiple forms of WRSM, particularly those that engaged in all assessed forms of WRSM, had higher eating disorder symptomology. Although the present study cannot determine causality, it is plausible that WRSM does in fact cause increased eating disorder symptomology. One mechanism in which WRSM may lead to increased eating disorder symptomology is through negative emotion. Prior research on self-weighing has shown that for some self-weighing leads to negative changes in mood (Mintz et al., 2013), and negative affect is known to immediately proceed eating disorder behaviors (Johnson & Larson, 1982; Smyth et al., 2007; Stice, 2002). It is therefore plausible that WRSM may cause negative changes in mood, leading to eating disorder symptomology. If there is indeed a causal relationship, this could have profound impacts on public health interventions aimed at WRSM. For example, there is a push to make nutrition information available on college campuses. Many campuses have begun labeling pre-packaged food, as well as providing labels in dining halls, or making nutritional information available online. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that introducing nutrition and calorie information may lead to better nutritional choices, though effects related to eating disorder symptomology remain unclear (Christoph & An, 2018). Beyond the limited utility of nutrition labeling on college campuses, our finding that knowing nutrition and calorie information is cross-sectionally associated with all measures of increased eating disorder symptomology among women and use of compensatory behaviors among men, suggests that nutrition labeling on college campuses could in fact be harmful. A previous study found that those who utilize these nutrition labels have higher perceived stress (Christoph, Ellison, & Meador, 2016); it is possible that the higher perceived stress may be due in part to shame, guilt, or mood changes surrounding food choices, which could thereby increase eating disorder symptomology. Therefore, our results suggest that colleges and universities should exhibit caution before implementing nutrition labels on college campuses. Future prospective research is needed to further elucidate the temporality of the relationships between WRSM and eating disorder symptomology.

Alternatively, it is possible that WRSM may be a byproduct of eating disorder symptomology in that individuals who are already concerned about eating and weight are using WRSM to gain further control over their eating or weight. However, if this is the case, the study findings still have important implications, particularly for eating disorder screening and treatment on college campuses. Prior research shows that online campus-wide screening is effective to treat and prevent eating disorders (Beintner, Jacobi, & Taylor, 2012; Wilfley, Agras, & Taylor, 2013). By including measures of WRSM in these screenings, college campuses could identify those who are engaging in multiple WRSM behaviors and thus may have higher eating disorder symptomology. Targeted online resources could then be shared with these students to assist in treating eating disorders or preventing full-syndrome eating disorders from developing. Additionally, individuals may underreport the use of eating disorder behaviors due to secrecy, shame, or stigma, but may not have the same shame or stigma associated with WRSM. Thus, using WRSM questions instead of eating disorder behaviors alone may identify more individuals who are struggling, particularly among men (Reba-Harrelson et al., 2009; Strother, Lemberg, Stanford, & Turberville, 2012). Further, the present paper adds novel insight into how individuals with elevated eating disorder symptomology are using WRSM, which could allow for clinicians to better identify, target, and address problematic eating disorder behaviors in the context of eating disorder treatment in this vulnerable population.

The present study has several strengths including the large sample of students from multiple institutions. This large sample allowed us to identify patterns of WRSM use by gender and explore gender-specific relationships between WRSM and eating disorder symptomology. Having a sample from multiple institutions also ensures that our findings are not specific to a single institution, and thus increases the study’s external validity. Further, we examined multiple forms of dietary self-monitoring, including forms of dietary self-monitoring that are prevalent among college students but to our knowledge have never been explored. Our examination of how different forms of WRSM are used in conjunction with one another and how those unique patterns of use are associated with eating disorder symptomology was also a key strength. By examining individual behaviors (such as knowing calories) previous studies may have inaccurately described effect estimates, since there are no associations among men when passive forms of WRSM when not combined with more active forms of WRSM. Our measure of eating disorder symptomology was another strength of the study, as the EDE-Q is a widely used and well validated measure (C.G. Fairburn & Beglin, 2008; Lavender et al., 2010; Luce, Crowther, & Pole, 2008; Nakai et al., 2014; V. M. Quick & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2013).

Despite the numerous strengths, the study is not without limitations. Single item measures were used to assess WRSM, though this is currently the standard in the literature (Christoph et al., 2018; Pacanowski, Loth, et al., 2015; Romano et al., 2018; Simpson & Mazzeo, 2017). We also did not assess the methods individuals were using to WRSM, and it is possible that cognitive versus behavioral tracking may be associated with differential symptomology and warrants further research. Additionally, while we used a data-driven approach to select the cut-off for frequent self-weighing, there may be a subset of participants not weighing themselves as a form of body avoidance, and there may therefore be heterogeneity of symptomology among those who do not self-weigh (Shafran, Fairburn, Robinson, & Lask, 2004). The study was also cross-sectional, and therefore, we cannot establish causality. It may be that WRSM is a symptom or indicator of an eating disorder rather than causing increased symptomology for eating disorders. However, if even in the case of reverse causality, there would still be value in the present findings as individuals who engage in WRSM could still be flagged as a population to target in interventions. There may have also been unmeasured confounding factors such as perceiving one’s self as overweight, perfectionism, internalization of the thin ideal, and preoccupation with weight and/or shape and food explaining these cross-sectional relationships. Additionally, response rates for HBS were low (19% and 27%), though comparable to other online survey response rates among college students (Bemel, Brower, Chischillie, & Shepherd, 2016; Chen, Szalacha, & Menon, 2014; Giles, Champion, Sutfin, McCoy, & Wagoner, 2009). In an attempt to correct for the low response rate, we employed probability sampling weights during analysis. We also excluded individuals who identified as a gender minority, as we were not powered to conduct gender stratified analyses. Because certain gender minorities are at increased risk for eating disorders among college students (Diemer, Grant, Munn-Chernoff, Patterson, & Duncan, 2015), future research should prioritize examining the relationships between WRSM and eating disorder symptomology in this population. Finally, our results cannot be generalized to young adults who are not enrolled in undergraduate or graduate studies.

The findings from the present study provide detailed information regarding how college students are using WRSM methods, alone and in combination, and insight into how unique patterns of WRSM are associated with eating disorder symptomology. WRSM is common among this population, particularly dietary self-monitoring, and WRSM strategies are frequently used in conjunction with one another. Among women, use of more WRSM methods is associated with higher eating disorder symptomology, with the greater likelihood of eating disorder behaviors and cognitions among those that engaged in all measured forms of WRSM. Among men, engaging in more active forms of WRSM is associated with increased eating disorder symptomology compared to those that engage in more passive forms of WRSM or who do not WRSM. Finally, longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to understand temporality and causality of the observed relationships between WRSM and eating disorder symptomology among college students.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the Healthy Bodies Study.

Funding: There are no specific funding sources to disclose for the Healthy Bodies Study. However, the University of Michigan Rackham Predoctoral Fellowship assisted in the funding for the dissertation of Samantha Hahn, of which this research was a part of. Additionally, the time to write this manuscript by Samantha Hahn was partially funded by Grant Number T32MH082761 from the National Institute of Mental Health (PI: Scott Crow).

Footnotes

Data Availability: Data from the Healthy Bodies Study is not available to the public.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Slof Op’t Landt MC, & Van Furth EF (2012). Norms and discriminative validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). Eat Behav, 13(4), 305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beintner I, Jacobi C, & Taylor CB (2012). Effects of an Internet-based prevention programme for eating disorders in the USA and Germany--a meta-analytic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 20(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1002/erv.1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemel JE, Brower C, Chischillie A, & Shepherd J. (2016). The Impact of College Student Financial Health on Other Dimensions of Health. Am J Health Promot, 30(4), 224–230. doi: 10.1177/0890117116639562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Szalacha LA, & Menon U. (2014). Perceived discrimination and its associations with mental health and substance use among Asian American and Pacific Islander undergraduate and graduate students. J Am Coll Health, 62(6), 390–398. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.917648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph MJ, & An R. (2018). Effect of nutrition labels on dietary quality among college students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev, 76(3), 187–203. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nux069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph MJ, & Ellison B. (2017). A Cross-Sectional Study of the Relationship between Nutrition Label Use and Food Selection, Servings, and Consumption in a University Dining Setting. J Acad Nutr Diet, 117(10), 1528–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph MJ, Ellison BD, & Meador EN (2016). The Influence of Nutrition Label Placement on Awareness and Use among College Students in a Dining Hall Setting. J Acad Nutr Diet, 116(9), 1395–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoph MJ, Larson N, Laska MN, & Neumark-Sztainer D. (2018). Nutrition Facts Panels: Who Uses Them, What Do They Use, and How Does Use Relate to Dietary Intake? J Acad Nutr Diet, 118(2), 217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R, & Papadaki A. (2014). Nutrition label use mediates the positive relationship between nutrition knowledge and attitudes towards healthy eating with dietary quality among university students in the UK. Appetite, 83, 297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.08.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA, Patterson DA, & Duncan AE (2015). Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students. J Adolesc Health, 57(2), 144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Nicklett EJ, Roeder K, & Kirz NE (2011). Eating disorder symptoms among college students: prevalence, persistence, correlates, and treatment-seeking. J Am Coll Health, 59(8), 700–707. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.546461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord, 16(4), 363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Beglin SJ (2008). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (6.0). In Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. New York: Guilford Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, & Tavolacci MP (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles SM, Champion H, Sutfin EL, McCoy TP, & Wagoner K. (2009). Calorie restriction on drinking days: an examination of drinking consequences among college students. J Am Coll Health, 57(6), 603–609. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.6.603-610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A, Heshmati A, & Koupil I. (2014). Family history of education predicts eating disorders across multiple generations among 2 million Swedish males and females. PLoS One, 9(8), e106475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DJ, & Laska MN (2012). Nutrition label use partially mediates the relationship between attitude toward healthy eating and overall dietary quality among college students. J Acad Nutr Diet, 112(3), 414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnare NA, Silliman K, & Morris MN (2013). Accuracy of self-reported weight and role of gender, body mass index, weight satisfaction, weighing behavior, and physical activity among rural college students. Body Image, 10(3), 406–410. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerr SL, Bokram R, Lugo B, Bivins T, & Keast DR (2002). Risk for disordered eating relates to both gender and ethnicity for college students. J Am Coll Nutr, 21(4), 307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr., & Kessler RC (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry, 61(3), 348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, Ard JD, Comuzzie AG, Donato KA, . . . Obesity S. (2014). 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation, 129(25 Suppl 2), S102–138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson C, & Larson R. (1982). Bulimia: an analysis of moods and behavior. Psychosom Med, 44(4), 341–351. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198209000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klos LA, Esser VE, & Kessler MM (2012). To weigh or not to weigh: the relationship between self-weighing behavior and body image among adults. Body Image, 9(4), 551–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Collins LM, Lemmon DR, & Schafer JL (2007). PROC LCA: A SAS Procedure for Latent Class Analysis. Struct Equ Modeling, 14(4), 671–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, & Anderson DA (2010). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate men. Eat Behav, 11(2), 119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Kelsey JL, Zhang Z, Lemon SC, Mezgebu S, Boddie-Willis C, & Reed GW (2009). Small-area estimation and prioritizing communities for obesity control in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health, 99(3), 511–519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson SK, & Sonneville KR (2017). Eating disorder symptoms among undergraduate and graduate students at 12 U.S. colleges and universities. Eat Behav, 24, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH, Crowther JH, & Pole M. (2008). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate women. Int J Eat Disord, 41(3), 273–276. doi: 10.1002/eat.20504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinauskas BM, Raedeke TD, Aeby VG, Smith JL, & Dallas MB (2006). Dieting practices, weight perceptions, and body composition: a comparison of normal weight, overweight, and obese college females. Nutr J, 5, 11. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-5-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio A, & Rima B. (2011). Watching My Weight: Self-Weighing, Body Surveillance, and Body Dissatisfaction. Sex Roles, 65(1), 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz LB, Awad GH, Stinson RD, Bledman RA, Coker AD, Kashubeck-West S, & Connelly K. (2013). Weighing and Body Monitoring Among College Women: The Scale Number as an Emotional Barometer. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 27(1), 78–91. doi: 10.1080/87568225.2013.739039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SB, Griffiths S, & Mond JM (2016). Evolving eating disorder psychopathology: conceptualising muscularity-oriented disordered eating. Br J Psychiatry, 208(5), 414–415. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.168427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai Y, Nin K, Fukushima M, Nakamura K, Noma S, Teramukai S, . . . Wonderlich S. (2014). Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for undergraduate Japanese women. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 22(6), 439–442. doi: 10.1002/erv.2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, van den Berg P, Hannan PJ, & Story M. (2006). Self-weighing in adolescents: helpful or harmful? Longitudinal associations with body weight changes and disordered eating. J Adolesc Health, 39(6), 811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel PH, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ, Kahwati L, Tsevat J, Nelson K, . . . Hazuda HP (2010). Obesity diagnosis and care practices in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med, 25(6), 510–516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1279-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel PH, Wang CP, Bollinger MJ, Pugh MJ, Copeland LA, Tsevat J, . . . Hazuda HP (2012). Intensity and duration of obesity-related counseling: association with 5-Year BMI trends among obese primary care patients. Obesity (Silver Spring), 20(4), 773–782. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J, & Whyman C. (1997). The effect of repeated weighing on psychological state. European Eating Disorders Review, 5(2), 121–130. doi:Doi [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacanowski CR, Crosby RD, & Grilo CM (2019). Self-weighing behavior in individuals with binge-eating disorder. Eat Disord, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2019.1656467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacanowski CR, Linde JA, & Neumark-Sztainer D. (2015). Self-Weighing: Helpful or Harmful for Psychological Well-Being? A Review of the Literature. Curr Obes Rep, 4(1), 65–72. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0142-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacanowski CR, Loth KA, Hannan PJ, Linde JA, & Neumark-Sztainer DR (2015). Self-Weighing Throughout Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Implications for Well-Being. J Nutr Educ Behav, 47(6), 506–515 e501. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L, Kemppainen JK, Mechling BM, MacKain S, Kim-Godwin Y, & Leopard L. (2015). Eating disorders and spirituality in college students. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv, 53(1), 30–37. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20141201-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plateau CR, Bone S, Lanning E, & Meyer C. (2018). Monitoring eating and activity: Links with disordered eating, compulsive exercise, and general wellbeing among young adults. Int J Eat Disord, 51(11), 1270–1276. doi: 10.1002/eat.22966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick V, Larson N, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ, & Neumark-Sztainer D. (2012). Self-weighing behaviors in young adults: tipping the scale toward unhealthy eating behaviors? J Adolesc Health, 51(5), 468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick VM, & Byrd-Bredbenner C. (2013). Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): norms for US college students. Eat Weight Disord, 18(1), 29–35. doi: 10.1007/s40519-013-0015-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reba-Harrelson L, Von Holle A, Hamer RM, Swann R, Reyes ML, & Bulik CM (2009). Patterns and prevalence of disordered eating and weight control behaviors in women ages 25–45. Eat Weight Disord, 14(4), e190–198. doi: 10.1007/BF03325116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ro O, Reas DL, & Stedal K. (2015). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in Norwegian Adults: Discrimination between Female Controls and Eating Disorder Patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev, 23(5), 408–412. doi: 10.1002/erv.2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano KA, Swanbrow Becker MA, Colgary CD, & Magnuson A. (2018). Helpful or harmful? The comparative value of self-weighing and calorie counting versus intuitive eating on the eating disorder symptomology of college students. Eat Weight Disord, 23(6), 841–848. doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0562-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran R, Fairburn CG, Robinson P, & Lask B. (2004). Body checking and its avoidance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord, 35(1), 93–101. doi: 10.1002/eat.10228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CC, & Mazzeo SE (2017). Calorie counting and fitness tracking technology: Associations with eating disorder symptomatology. Eat Behav, 26, 89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, & Engel SG (2007). Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Consult Clin Psychol, 75(4), 629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull, 128(5), 825–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strother E, Lemberg R, Stanford SC, & Turberville D. (2012). Eating disorders in men: underdiagnosed, undertreated, and misunderstood. Eat Disord, 20(5), 346–355. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.715512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, & Merikangas KR (2011). Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 68(7), 714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavolacci MP, Grigioni S, Richard L, Meyrignac G, Dechelotte P, & Ladner J. (2015). Eating Disorders and Associated Health Risks Among University Students. J Nutr Educ Behav, 47(5), 412–420 e411. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DJ, & Charlton BG (2014). The association between the development of weighing technology, possession and use of weighing scales, and self-reported severity of disordered eating. Ir J Med Sci, 183(3), 471–475. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-1047-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Agras WS, & Taylor CB (2013). Reducing the burden of eating disorders: a model for population-based prevention and treatment for university and college campuses. Int J Eat Disord, 46(5), 529–532. doi: 10.1002/eat.22117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]