Abstract

Introduction:

Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines recommend that clinicians empirically treat the sex partners of persons with Neisseria gonorrhoeae (GC) or Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) infection before confirming that they are infected. It is possible that this practice, known as epidemiologic treatment, results in overtreatment for uninfected persons and may contribute to development of antimicrobial resistance. We sought to quantify the number of patients who received epidemiologic treatment and the proportion of those who were overtreated.

Methods:

We reviewed records from a municipal sexually transmitted disease clinic in Seattle, WA, from 1994 to 2018 to identify visits by asymptomatic patients seeking care because of sexual contact to a partner with GC and/or CT. We defined overtreatment as receipt of antibiotic(s) in the absence of a positive GC/CT test result and calculated the proportions of contacts epidemiologically treated and tested positive for GC/CT and overtreated in five 5-year periods stratified by sex and gender of sex partner. We used the Cochran-Armitage test to assess for temporal trends.

Results:

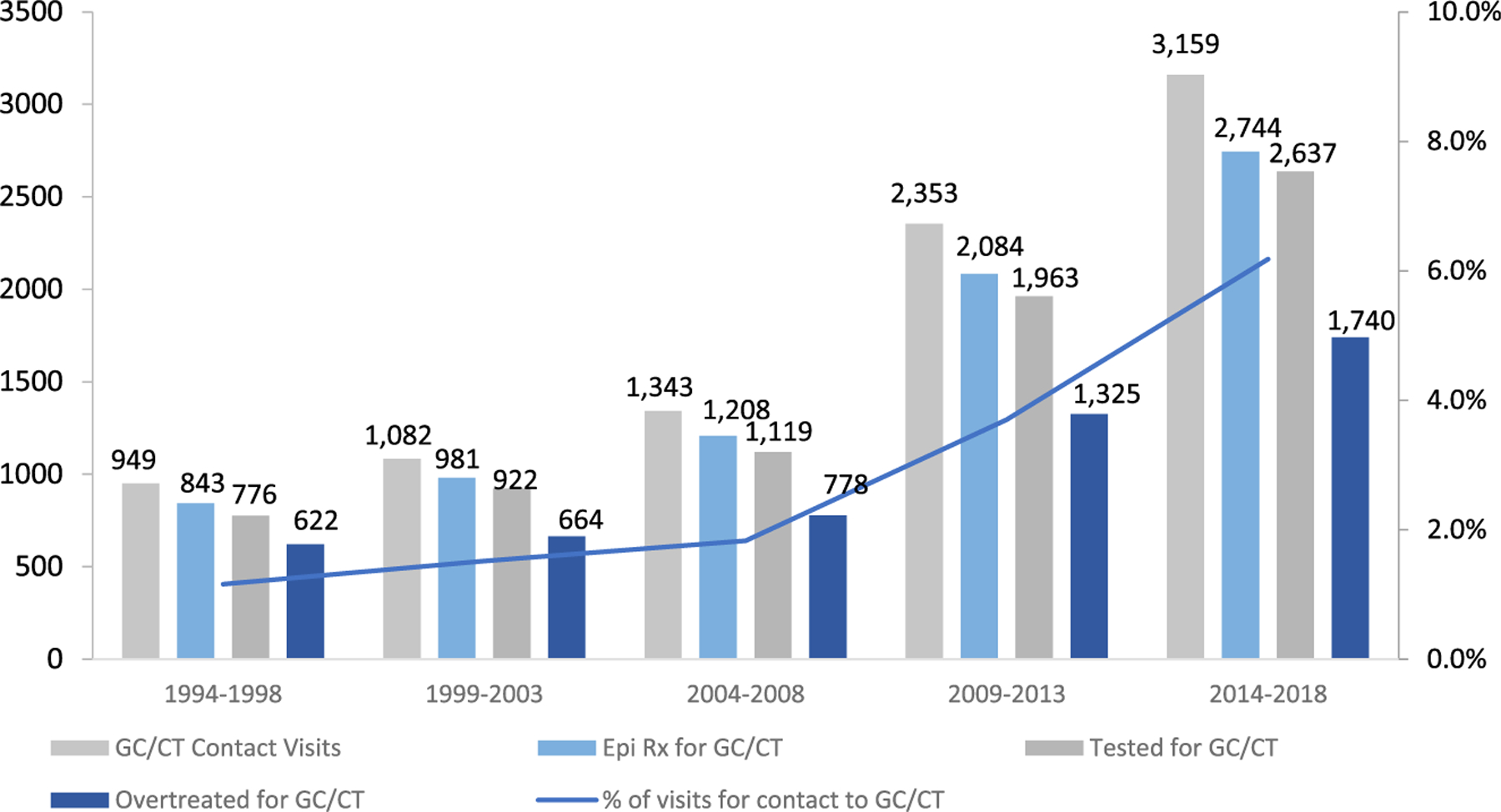

The number of asymptomatic contacts epidemiologically treated for GC/CT increased from 949 to 3159 between the 1994–1998 and 2014–2018 periods. In 2014–2018, 55% of persons were overtreated, most (82.1%) of these were men who have sex with men (MSM). The proportion of MSM overtreated decreased from 74% to 65% (P < 0.01), but the total number of overtreated MSM increased from 172 to 1428.

Discussion:

A high proportion of persons receiving epidemiologic treatment of GC/CTare uninfected. The current practice of routinely treating all sex partners of persons with GC/CT merits reconsideration in light of growing antimicrobial resistance.

Current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sexually transmitted disease (STD) treatment guidelines recommend that clinicians treat the sex partners of persons with gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or GC), chlamydia (Chlamydia trachomatis, or CT), or syphilis at the time they present for care and before laboratory confirmation of infection, a strategy called epidemiologic treatment.1,2 Public health authorities and clinicians have typically justified epidemiologic treatment based on the high prevalence of infection observed in sex partners and concerns that waiting for laboratory confirmation of infection will lead to delayed or missed treatment opportunities3,4 with resultant morbidity and increased STD transmission. Studies on expedited partner therapy for contacts to persons diagnosed with GC or CT, a partner-delivered form of epidemiologic treatment, suggest that treating exposed partners can reduce reinfection rates5–7 and may decrease population-level morbidity among heterosexual populations.8

Epidemiologic treatment has not been systematically evaluated within the current context of sexually transmitted infection epidemiology in the United States. When the strategy was first implemented, diagnostic tests for gonorrhea and syphilis had poor sensitivity and effective antibiotics seemed to be in abundance. In the current era, highly sensitive molecular diagnostics make it possible to diagnose virtually all infected partners if all exposed anatomic sites are tested, whereas antimicrobial resistance—particularly antimicrobial resistant GC—has become a major public health concern.9 Exposure to antibiotics is known to promote antimicrobial resistance,10,11 and the widespread use of antibiotics for CT and GC treatment, including antimicrobial use as part of epidemiologic treatment, may be contributing to the rapid rise in antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea. Epidemiologic treatment warrants reexamination considering the potential risks and benefits within this context.

We sought to quantify the extent to which epidemiologic treatment is provided and the proportion of cases of epidemiologic treatment that occur in the absence of an STD infection using 25 years of visits to the Public Health—Seattle & King County Sexual Health Clinic (PHSKC-SHC).

METHODS

Study Population

All patients who presented to the PHSKC-SHC between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2018, were included in this analysis. Data used for this analysis were collected as part of routine clinical care and recorded into the clinic’s electronic database system. All data were deidentified before analysis. As a public health program evaluation, institutional review board approval was not required.

Clinical Procedures

Patients presenting to the clinic answered questions detailing demographic information, sexual history, and reason(s) for clinical visit. Before 2010, this information was collected through an in-person interview with a clinician. Beginning in 2010, patients reported the same information using a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI). During the examination, clinicians used standardized forms to record sexual histories, examination findings, and treatment.

Clinicians performed anatomic site-specific STD testing based on the patient’s reported sexual risks. Patients were determined to be tested at a specific anatomic site if there was a record of a diagnostic test performed during the visit at which they were determined to have exposure to GC and/or CT. Before 2002, all gonorrhea and chlamydia testing was performed using culture.12 In 2002, the clinic began using a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) for urogenital gonorrhea and chlamydia testing and Aptima Combo 2 (Hologic, Bedford, MA). Until 2011, the clinic used culture to diagnose rectal and pharyngeal gonorrhea and rectal chlamydia; thereafter, extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia were diagnosed by NAAT with the Aptima Combo 2.

Women were tested through self-collected vaginal NAATs, provider-collected endocervical NAATand/or culture, or urine NAAT. Men primarily provided urine specimens for NAAT; alternatively, a provider collected a urethral swab for culture. In addition, men who have sex with men (MSM) were also tested at the throat and/or rectum according to sexual exposure at those sites.

Clinic policy throughout the study period was to treat patients reporting contact to GC/CT on the day of presentation and test concurrently. For patients reporting contact to GC only, treatment consisted of both an antigonococcal and antichlamydial active antimicrobial agent(s). For patients reporting contact only to CT, only an antichlamydial agent was prescribed.

Definitions: Contacts, Epidemiologic Treatment, and Overtreatment

We considered the reason for a patient’s visit as evaluation for contact to GC/CT if the patient reported contact to either of these infections during their intake interview/CASI or if the clinician recorded that the patient had contact to either of these infections. In some cases, patients did not report GC/CT contact but were deemed a contact by clinicians as a result of communication from PHSKC disease intervention specialists who are colocated within the STD clinic. Patients who reported STI symptoms (urethral discharge, urethral pruritis, dysuria, testicular pain, anal pain, vaginal discharge, vaginal odor, vaginal pruritis, urinary urgency, female abdominal pain) on their intake interview/CASI or for whom clinicians recorded signs or symptoms (urethral or vaginal discharge, or cervical exudate) were excluded as these patients were likely to have received syndromic treatment. We considered patients as receiving epidemiologic treatment of GC if the reason for their visit was evaluation for exposure to GC plus indication of any of the following treatments: (1) cefixime 400 mg or cefpodoxime 400 mg or ceftriaxone at either 125 or 250 mg as well as azithromycin 1 g or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 7 days, (2) azithromycin 2 g, or (3) ciprofloxacin 500 mg. Patients were considered to have received epidemiologic treatment of CT if the reason for their visit was evaluation for CTand the medical record indicated treatment with either azithromycin (1 or 2 g), Erythromycin, levofloxacin 500 mg, ofloxacin 400 mg, or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 7 days. Treatment was abstracted from the clinical record. Patients testing positive for GC/CT at any of the tested anatomic sites were classified as GC/CT positive. We considered persons who reported or were deemed a contact to GC/CT, received treatment, were tested at ≥1 anatomic site, and were negative on same-day GC/CT testing to have been overtreated.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the percentage of persons overtreated for gonorrhea as the number of asymptomatic persons epidemiologically treated as a contact to GC, CT, or GC and CTwho were negative for both GC/CT at all tested anatomic sites, divided by the total number of persons evaluated as a contact to GC, CT, or GC and CT who received epidemiologic treatment and were tested at ≥1 anatomic site, stratified by sex and gender of sex partners. We calculated the proportion of contacts epidemiologically treated (including the proportion of patients receiving specific categories of antimicrobial drugs), the proportion tested, the proportion of MSM tested at specific anatomic sites, the proportion positive for CT and/or GC infection, the proportion of MSM positive for CT and/or GC at specific anatomic sites, and proportions of persons overtreated for CT and/or GC in each of five 5-year periods (1994–1998, 1999–2003, 2004–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2018). Because one of the major impetuses for using epidemiologic treatment is the fear that patientswill not receive appropriate treatment if they have to await test results, we also calculated the proportion of persons screened (i.e., tested in the absence of symptoms and not as a contact) for GC who were positive at any anatomic site and the proportion who received treatment. For this analysis, we included treatment received at either the PHSKC-STD Clinic or at another location as documented in PHSKC surveillance records; because of surveillance record limitations, we only examined the treatment completion rate for 2014–2018. We examined temporal changes in the proportion of clinic visits for contact to CT and/or GC, contacts epidemiologically treated, contacts tested, and the proportion of persons overtreated for CTand/or GC using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. All analyses were conducted using Stata software v15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). An α of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinic Visits for Contact to GC/CT

Between January 1, 1994, and December 31, 2018, there were 341,687 total visits to the PHSKC STD clinic, of which 8886 (3.0%) visits were for contact to GC/CT by persons without STD signs or symptoms (Table 1). Approximately 50% of contacts to GC/CT were White and 93% were male, with a median age of 30 years. The proportion of contacts to GC/CT that were MSM increased from 27% in 1994–1998 to 80% in 2014–2018. The proportion of clinic visits for contact to GC/CT increased from 1.2% in 1994–1998 to 6.2% in 2014–2018 (P < 0.0001). The proportion of clinic visits for contact to GC/CT increased for all populations, with the largest increases occurring in MSM; the proportion of clinic visits for contact to GC/CT increased from 3.8% in 1994–1998 to 9.9% in 2014–2018 for MSM (P < 0.0001), from 1.4% to 2.7% in men who have sex with women (MSW; P < 0.0001), and from 0.2% to 1.8% in women (P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Study Population

| 1994–1998 | 1999–2003 | 2004–2008 | 2009–2013 | 2014–2018 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||||

| Contact to CT/GC visits | 949 (1) | 1082 (2) | 1343 (2) | 2353 (4) | 3159 (6) | 8886 (3) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 75 (8) | 369 (34) | 837 (62) | 1559 (66) | 2123 (67) | 4963 (56) |

| Black | 73 (8) | 196 (18) | 283 (21) | 318 (21) | 285 (9) | 1155 (13) |

| Asian | 4 (<1) | 35 (3) | 63 (5) | 163 (7) | 248 (8) | 513 (6) |

| Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 1 (<1) | 12 (1) | 21 (2) | 37 (2) | 39 (1) | 110 (1) |

| Alaska Native/Native American | 2 (<1) | 15 (1) | 22 (2) | 18 (1) | 34 (1) | 91 (1) |

| Other | 3 (<1) | 32 (3) | 47 (4) | 69 (3) | 97 (3) | 248 (3) |

| Missing/unknown/declined | 791 (83) | 423 (39) | 70 (5) | 189 (8) | 333 (11) | 1806 (20) |

| Age (median), y | 26 | 27 | 29 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

| 12–24 | 388 (41) | 412 (38) | 380 (28) | 568 (24) | 562 (18) | 2310 (26) |

| 25–34 | 389 (41) | 387 (36) | 502 (37) | 900 (38) | 1362 (43) | 3540 (40) |

| 35–44 | 120 (13) | 193 (18) | 288 (21) | 503 (21) | 626 (20) | 1730 (19) |

| 45+ | 52 (5) | 90 (8) | 172 (13) | 382 (16) | 609 (19) | 1305 (15) |

| Male | 879 (93) | 972 (90) | 1196 (89) | 2200 (94) | 3013 (95) | 8260 (93) |

| MSM | 256 (27) | 374 (35) | 670 (50) | 1685 (72) | 2538 (80) | 5523 (62) |

| Self-reported HIV positive | 37 (4) | 53 (5) | 128 (10) | 302 (13) | 378 (12) | 898 (10) |

| Sexual partners in the past 2 mo | ||||||

| Median (range) | 1 (0–50) | 1 (0–202) | 2 (0–150) | 2 (0–302) | 3 (0–300) | 2 (0–302) |

| 0 | 34 (4) | 37 (3) | 39 (3) | 55 (2) | 37 (1) | 202 (2) |

| 1 | 540 (57) | 567 (52) | 542 (40) | 578 (24) | 582 (18) | 2798 (31) |

| 2 | 220 (23) | 229 (21) | 289 (22) | 553 (24) | 584 (18) | 1875 (21) |

| 3–5 | 108 (11) | 157 (21) | 264 (20) | 630 (27) | 1009 (32) | 2168 (24) |

| 6+ | 47 (5) | 92 (9) | 220 (16) | 537 (23) | 947 (30) | 1843 (21) |

| Drug use ever* | 67 (7) | 92 (9) | 195 (15) | 524 (23) | 787 (25) | 1665 (19) |

| Uninsured | 721 (76) | 828 (77) | 785 (58) | 1248 (53) | 1503 (48) | 5085 (57) |

| History of GC | 220 (23) | 210 (19) | 277 (21) | 608 (26) | 856 (27) | 2171 (24) |

| History of CT | 24 (3) | 150 (14) | 288 (21) | 520 (22) | 778 (25) | 1760 (20) |

Includes methamphetamine, crack cocaine, cocaine, and heroin.

Epidemiologic Treatment for Contacts to GC and/or CT

Most asymptomatic patients with a clinic visit for contact to GC/CT were epidemiologically treated in all periods examined (Fig. 1) and decreased from a high of 90.7% of contacts treated in 1999–2003 to a low of 86.9% of contacts treated in 2014–2018 (P = 0.002). A higher proportion of MSM were epidemiologically treated compared with MSW and women in all periods examined.

Figure 1.

Clinic visits, epidemiologic treatment, and overtreatment for contact to gonorrhea and/or chlamydia among asymptomatic patients, Public Health Seattle/King County STD Clinic, 1994 to 2018.

Testing in Epidemiologically Treated Contacts to GC and/or CT

Nearly all asymptomatic patients who were epidemiologically treated for GC and/or CT were tested at ≥1 anatomic site (Fig. 1). More than 95% of MSM were tested in all periods examined (Table 2; P = 0.08). The proportion of MSM tested for urethral GC/CT infection increased from 87% in 1994–1998 to 97% in 2004–2008 before decreasing to 82% in 2014–2018 (P < 0.001), whereas the proportion tested for rectal and pharyngeal infections increased from 54% to 75% (P < 0.001) and 81% to 94% (P < 0.001), respectively. Among MSW, the proportion tested for urogenital GC/CT decreased from a high of 97% in 1999–2003 to 87% in 2009–2013 and 2014–2018 (P < 0.001); among women, the proportion tested for urogenital GC/CT increased from 56% in 1994–1998 to 86% in 2014–2018 (P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Clinic Visits*, Epidemiologic Treatment†, Tested‡, and Overtreatment§ for Contact Visits for Gonorrhea and/or Chlamydia, Public Health Seattle/King County STD Clinic, 1994 to 2018

| 1994–1998 | 1999–2003 | 2004–2008 | 2009–2013 | 2014–2018 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||||

| Total | ||||||

| Contact to GC and/or CT visits¶ | 949 (1) | 1082 (2) | 1343 (2) | 2353 (4) | 3159 (6) | 8886 (3) |

| Epidemiologically treated¶ | 843 (89) | 981 (91) | 1208 (90) | 2084 (89) | 2744 (87) | 7860 (89) |

| Tested for GC and/or CT¶ | 776 (92) | 922 (94) | 1119 (93) | 1963 (94) | 2637 (96) | 7417 (94) |

| GC and/or CT positive¶ | 154 (20) | 258 (28) | 341 (31) | 638 (33) | 897 (34) | 2288 (31) |

| Overtreated for GC and/or CT¶ | 622 (74) | 664 (72) | 778 (58) | 1325 (67) | 1740 (66) | 5129 (65) |

| MSM | ||||||

| Contact to GC and/or CT visits¶ | 256 (4) | 374 (4) | 670 (4) | 1685 (8) | 2538 (10) | 5523 (7) |

| Epidemiologically treated¶ | 236 (92) | 349 (93) | 609 (91) | 1523 (90) | 2234 (88) | 4951 (90) |

| Tested for GC and/or CT | 232 (98) | 335 (96) | 583 (96) | 1463 (96) | 2185 (98) | 4789 (97) |

| Urethral¶ | 202 (87) | 319 (95) | 568 (97) | 1370 (94) | 1792 (82) | 4251 (89) |

| Rectal¶ | 126 (54) | 226 (67) | 402 (69) | 1081 (74) | 1630 (75) | 3465 (72) |

| Pharyngeal¶ | 187 (81) | 296 (88) | 541 (93) | 1389 (95) | 2059 (94) | 4472 (93) |

| Urethral, rectal, and pharyngeal | 159 (69) | 281 (84) | 527 (90) | 1300 (89) | 1689 (77) | 4798 (82) |

| GC and/or CT positive | 60 (26) | 104 (31) | 193 (33) | 522 (36) | 757 (35) | 1636 (34) |

| Urethral | 11 (5) | 20 (6) | 26 (5) | 80 (6) | 119 (7) | 256 (6) |

| Rectal | 38 (30) | 73 (32) | 128 (32) | 358 (33) | 491 (30) | 1088 (31) |

| Pharyngeal¶ | 23 (12) | 31 (10) | 66 (12) | 239 (17) | 355 (17) | 714 (16) |

| Overtreated for GC and/or CT¶ | 172 (74) | 231 (69) | 390 (67) | 941 (64) | 1428 (65) | 3162 (66) |

| MSW | ||||||

| Contact to GC and/or CT visits¶ | 623 (1) | 598 (2) | 526 (2) | 515 (2) | 475 (3) | 2737 (2) |

| Epidemiologically treated¶ | 550 (88) | 530 (89) | 467 (89) | 439 (85) | 399 (84) | 2385 (87) |

| Tested for urogenital GC and/or CT¶ | 511 (93) | 515 (97) | 426 (91) | 381 (87) | 346 (87) | 2179 (92) |

| GC and/or CT positive¶ | 79 (15) | 122 (24) | 102 (24) | 70 (18) | 92 (26) | 465 (21) |

| Overtreated for GC and/or CT¶ | 432 (85) | 392 (76) | 321 (75) | 318 (82) | 257 (73) | 1720 (78) |

| Women | ||||||

| Contact to GC and/or CT visits¶ | 70 (<1) | 110 (<1) | 147 (1) | 153 (1) | 146 (2) | 626 (1) |

| Epidemiologically treated¶ | 57 (81) | 102 (93) | 132 (90) | 122 (80) | 111 (76) | 524 (84) |

| Tested for urogenital GC and/or CT¶ | 32 (56) | 72 (71) | 110 (83) | 109 (89) | 96 (86) | 419 (80) |

| GC and/or CT positive | 14 (44) | 31 (43) | 43 (39) | 43 (39) | 41 (43) | 172 (41) |

| Overtreated for GC and/or CT | 18 (56) | 41 (57) | 67 (61) | 66 (61) | 55 (57) | 247 (59) |

Of all clinic visits.

Of asymptomatic patients deemed a contact to GC and/or CT.

Of those receiving epidemiologic treatment.

Of those tested.

Test for trend significant at the P < 0.05 level.

GC/CT Infection and Overtreatment in Contacts to GC/CT Who Were Epidemiologically Treated

The proportion of tested contacts to GC/CTwho were positive for one or both infections increased from 20% in 1994–1998 to 34% in 2014–2018 (Table 2); the corresponding proportion of contacts who were overtreated ranged from 74% in 1994–1998 to 63% in 2014–2018 (P < 0.0001). Test positivity increased the most for MSM contacts, from 26% to 35% between 1994–1998 and 2014–2018 (P = 0.01). Although the corresponding proportion overtreated declined, a total of 3162 MSM were overtreated between 1994 and 2018, and almost half of overtreatments (45%) occurred in the 2014–2018 period. The proportion of MSW contacts who were positive for either or both infections also increased from 15% in 1994–1998 to 26% in 2014–2018 (P = 0.003), and the proportion overtreated declined from 85% to 73% in the same period; however, the absolute number of MSWovertreated was half that of the number of MSM overtreated (Table 2). In contrast, the proportion of female contacts who were positive for either or both infections was not statistically different over all periods examined, 43% to 61% of female contacts overtreated (P = 0.97).

Drugs Used for Epidemiologic Treatment

The proportion of asymptomatic patients having a clinic visit for contact to GC alone, CT alone, or GC and CT who were epidemiologically treated with different antimicrobial regimens is shown in Table 3. Among contacts to GC alone, the use of oral cephalosporins for epidemiologic treatment decreased from 95% of patients in 1994–1998 to 0 in 2014–2018; the use of intramuscular cephalosporin was 94% in 2014–2018. Use of doxycycline decreased over this period from 63% of contacts epidemiologically treated to 3%, whereas azithromycin use increased from 13% to 97%. Treatment with quinolones was not common and mainly limited to years 1994–2008. Azithromycin used increased over the study period for all types of epidemiologic treatment; in 2014–2018, it was used in >90% of contact treatments.

TABLE 3.

Drugs Used for Epidemiologic Treatment, Public Health Seattle/King County STD Clinic, 2014 to 2018

| 1994–1998 | 1999–2003 | 2004–2008 | 2009–2013 | 2014–2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||||

| Contact to GC only | |||||

| Epidemiologically treated* | 267 | 242 | 451 | 844 | 1145 |

| Oral cephalosporins | 253 (95) | 242 (84) | 451 (94) | 97 (10) | 0 (0) |

| IM cephalosporins | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) | 812 (86) | 1073 (94) |

| Doxycycline | 169 (63) | 48 (17) | 21 (4) | 14 (1) | 31 (3) |

| Azithromycin | 34 (13) | 150 (52) | 275 (57) | 799 (85) | 1106 (97) |

| Quinolones | 7 (3) | 47 (16) | 23 (5) | 3 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Other† | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 15 (1) |

| Contact to CT only | |||||

| Epidemiologically treated* | 541 | 635 | 642 | 983 | 1234 |

| Oral cephalosporins | 9 (2) | 13 (2) | 9 (1) | 3 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| IM cephalosporins | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 17 (1) |

| Doxycycline | 233 (43) | 43 (7) | 24 (4) | 31 (3) | 162 (13) |

| Azithromycin | 306 (57) | 591 (93) | 616 (96) | 951 (97) | 1081 (88) |

| Quinolones | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other† | 3 (1) | 1 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) |

| Contact to CT and GC | |||||

| Epidemiologically treated* | 28 | 44 | 63 | 133 | 335 |

| Oral cephalosporins | 28 (100) | 37 (84) | 61 (97) | 15 (11) | 0 (0) |

| IM cephalosporins | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 108 (81) | 320 (96) |

| Doxycycline | 14 (50) | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 45 (13) |

| Azithromycin | 14 (50) | 41 (93) | 63 (100) | 128 (96) | 296 (88) |

| Quinolones | 0 (0) | 7 (16) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Other† | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Drug categories are not mutually exclusive; categories may not sum to 100%.

Spectinomycin 2 g, erythromycin (varying dosages), study drug(s).

Anatomic Site of GC/CT Infection in MSM

More than 95% of MSM evaluated for contact to GC/CT were tested at ≥1 anatomic site in all periods examined (Table 2). Urethral and rectal GC/CT positivity was stable across all periods examined; however, pharyngeal CT/GC positivity increased from 12% in 1994–1998 to 17% in 2014–2018.

Among MSM contacts to CT only, CT positivity ranged from 19% in 1994–1998 to 25% in 2014–2018 (data not shown), and GC positivity increased from 4% in 1994–1998 to 8% in 2014–2018. Among MSM contacts to GC, GC positivity increased from 27% in 1994–1998 to 32% in 2004–2009 and subsequently declined to 29% in 2014–2018, and CT positivity increased from 3% in 1994–1998 to 16% in 2009–2013.

Gonorrhea Treatment Completion for Screen-Positive Persons

Between 2014 and 2018, 1354 patients tested positive for GC through screening at PHSKC STD clinic, most of whom were MSM (92%). Overall, we confirmed receipt of antigonococcal therapy for 91%, which varied by population: 92% of 1246 MSM, 75% of 32 MSW, and 80% of 76 women (χ2, P < 0.001) who screened GC positive received treatment.

DISCUSSION

In Seattle, both the number and proportion of STD clinic visits for contact to GC/CT have increased significantly over the past 25 years. Most of this increase occurred among MSM and is consistent with changing demographics of the clinic’s main patient population. At the same time, the proportion of contacts to GC/CT who received epidemiologic treatment and tested positive for GC/CT has remained less than 35%. Together, these trends demonstrate that a substantial number of STD clinic patients received antimicrobial therapy in the absence of GC/CT infection: nearly 1800 (63%) contacts received antibiotics in the absence of infection between 2014 and 2018 alone.

Epidemiologic treatment was developed in a historical context very different from the current epidemiologic landscape and was intended primarily to interrupt transmission of syphilis. Syphilis testing is imprecise and subject to a significant window period between infection and development of antibodies necessary for a positive serologic test result, during which infected persons will be negative on treponemal antibody tests. Epidemiologic treatment for contacts served to abort these occult infections before detection and was extremely effective; in a 1961 study on epidemiologic treatment of syphilis, none of the contacts to syphilis who were treated with a single dose of benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units developed syphilis compared with 9% of those who received a placebo treatment.2 The 1972 National Gonorrhea Control Strategy introduced the concept of epidemiologic treatment for sexual partners known to be infected with gonorrhea. Epidemiologic treatment of gonorrhea was primarily used in women, who are more likely to harbor asymptomatic infections than their male partners. For both syphilis and GC, targeting women of reproductive age conferred an exceptionally high benefit by preventing congenital syphilis and upper reproductive tract disease. Over the ensuing 25 years, the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease decreased more than 80% and congenital syphilis rates plummeted.13 However, quantifying epidemiologic treatment’s effects on GC/CT reinfection rates is more tenuous. A study of partner delivered epidemiologic treatment (known as expedited partner therapy) for heterosexual contacts to GC/CT demonstrated a 25% reduction in reinfection in the index case,5 whereas a community-randomized trial of expedited partner therapy suggested a decrease in the incidence of chlamydia and gonorrhea at the population level, but this was not statistically significant.8

Although epidemiologic treatment of GC/CT seems to be beneficial for women and heterosexual men, there are very few analyses evaluating the extent of use or effectiveness of GC/CTepidemiologic treatment in MSM. A microscopy audit from an STD clinic in the United Kingdom found that only 50% of MSM reporting contact to GC were positive on examination in 2013, a figure that was comparable to their positivity rate in women (45%),14,15 whereas recently published data from Australia found that only 29% of MSM contacts to GC/CT in the Sydney sexual health clinic were positive for either infection.16 Gonococcal and chlamydial infections in MSM, particularly in MSM contacts as our data show, are primarily isolated to pharyngeal and rectal sites. Infection at the pharynx and rectum are mostly asymptomatic, and it remains unclear whether these infections result in significant morbidity,17 although they are likely the primary source of community transmission.18,19 Thus, there may be an as-yet unquantified population-level benefit to epidemiologically treating MSM contacts to GC/CT.

Any benefits of epidemiologic treatment may be outweighed by the potential for development of antibiotic resistance. At present, the CDC recommends only one regimen (ceftriaxone plus azithromycin) to treat gonorrhea. However, 5% of urethral gonococcal isolates tested through CDC’s Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Program had decreased susceptibility to azithromycin in 2018,13 a statistic that fails to reveal the discrepancies between heterosexual men and MSM. Azithromycin-reduced susceptibility among MSM is more than 8% nationally but only 2% among heterosexual men.13 This may be due to the recent increase in overuse of azithromycin as part of epidemiologic treatment for MSM, as prior azithromycin use has been associated with a 2-fold increase in minimal inhibitory concentration.10 At the same time, rates of STDs continue to increase13 concurrently with increased used of HIV preexposure prophylaxis, which has been associated with a reduction in condom use20,21 and more sexual partners.22,23 Exposure to more sexual partners with a lower condom usage rate in sexual networks with higher prevalence of GC/CT will result in more frequent exposure to GC/CT and thus antibiotic exposure through epidemiologic treatment, which may further drive antimicrobial-resistant gonorrhea.

Owing to these factors, some STD clinics outside the United States have recently abandoned the practice of routinely treating all sex partners of persons with gonorrhea or chlamydial infection in the absence of confirmed infection.24 A common concern of this approach is that infected patients will not return to the clinic for treatment and will transmit the bacterium in the interim.25 However, a study from the United Kingdom demonstrated a nearly 100% recall rate for contacts to GC who deferred treatment until confirmation of infection and returned for treatment within a median of 6 days.14,15 In our clinic, 91% of those who screened positive for GC 2014–2018 returned for treatment in a median of 7 days. Although we acknowledge that other jurisdictions may have a lower recall rate than in Seattle or the United Kingdom, these extremely high treatment completion rates should alleviate some fears of the missed opportunity for treatment. Others have proposed use of a rapid, point-of-care test to diagnose infections at the time of the clinic visit26 in lieu of epidemiologic treatment.14,15 However, existing point-of-care tests are prohibitively expensive and do not provide results quickly enough for implementation in most clinical settings.27

As one of the first longitudinal analyses of epidemiologic treatment in the United States, this analysis was strengthened by the availability and completeness of clinical and laboratory data for nearly all STD clinic patients seen at PHSKC within a 25-year period, which allowed us to examine temporal trends in epidemiologic treatment, GC/CT positivity among contacts, and overtreatment. In addition, PHSKC is unique in having the capacity to perform extragenital testing for MSM throughout the entire study period, which increased our ability to detect the full anatomic spectrum of STD infections among contacts. A limitation of this analysis is the fact that MSW and female patients were less frequently screened for extragenital GC/CT infections, which may have incorrectly classified patients with extragenital GC/CT in the absence of urethral or cervicovaginal infections as negative28–31 and potentially underestimated GC/CT positivity in these populations. In addition, we considered all patients who self-reported contact to CT and/or GC as contacts to these infections; it is possible that patients may not have accurately reported their sexual exposures, leading to an underestimate or overestimate of GC/CT contact visits; however, patients were explicitly asked whether this is the reason for their visit each time they presented to the clinic via standardized CASI or clinician-led interview. The temporal trend of increased GC/CT positivity among epidemiologically treated contacts may be due to the adoption of more highly sensitive NAAT testing over the periods examined. Finally, given that the majority of our patient population is White MSM, it is possible that our results may not be generalizable to clinics serving a higher proportion of racial minorities and heterosexuals.13

In summary, we found that the number of uninfected persons empirically treated for GC/CT at the PHSKC-SHC clinic has increased significantly over the past 25 years. This increase has been most pronounced in MSM, a population at high risk for both STDs and antimicrobial-resistant GC. Of epidemiologically treated MSM diagnosed with GC/CT infection, rectal and pharyngeal infections are more common than urethral, yet the clinical implications of these infections are uncertain. The current era requires enhanced antimicrobial stewardship; further research to quantify the benefits and risk of epidemiologic treatment, particularly among MSM, is needed.

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding:

This research was supported by the University of Washington/Fred Hutch Center for AIDS Research, a National Institutes of Healthâ funded program under award number AI027757, which is supported by the following institutes and centers of the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.Johnson RE. Epidemiologic and prophylactic treatment of gonorrhea: a decision analysis review. Sex Transm Dis 1979; 6:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore MB, Price EV, Knox JM, Elgin LW. Epidemiologic treatment of contacts to infectious syphilis Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1915394/pdf/pubhealthreporig00083-0052.pdf. Accessed August 12, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Schwebke JR, Sadler R, Sutton JM, et al. Positive screening tests for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection fail to lead consistently to treatment of patients attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis 1997; 24:181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong D, Berman SM, Furness BW, et al. Time to treatment for women with chlamydial or gonococcal infections: A comparative evaluation of sexually transmitted disease clinics in 3 US cities. Sex Transm Dis 2005; 32:194–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schillinger JA, Kissinger P, Calvet H, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment with azithromycin to prevent repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection among women: A randomized, controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissinger P, Brown R, Reed K, et al. Effectiveness of patient delivered partner medication for preventing recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect 1998; 74:331–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golden MR, Kerani RP, Stenger M, et al. Uptake and population-level impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) on Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: The Washington State community-level randomized trial of EPT. PLoS Med 2015; 12:e1001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States: Stepping back from the brink—Editorials—American Family Physician. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/0615/p938.html. Accessed January 21, 2020. [PubMed]

- 10.Wind CM, De Vries E, Schim Van Der Loeff MF, et al. Decreased azithromycin susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in patients recently treated with azithromycin. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malhotra-Kumar S, Lammens C, Coenen S, et al. Effect of azithromycin and clarithromycin therapy on pharyngeal carriage of macrolide-resistant streptococci in healthy volunteers: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2007; 369:482–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamm WE, Tam M, Koester M, et al. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis inclusions in Mccoy cell cultures with fluorescein-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. J Clin Microbiol 1983; 17:666–668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2018. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mensforth S, Thorley N, Radcliffe K. Auditing the use and assessing the clinical utility of microscopy as a point-of-care test for Neisseria gonorrhoeae in a sexual health clinic. Int J STD AIDS 2018; 29:157–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mensforth S, Radcliffe K. Is it time to reconsider epidemiological treatment for gonorrhoea? Int J STD AIDS 2018; 29:1043–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qian S, Foster R, Bourne C, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae positivity in clients presenting as asymptomatic contacts of gonorrhoea at a sexual health centre. Sex Health 2020; 17:187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan PA, Robinette A, Montgomery M, et al. Extragenital infections caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A review of the literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016; 2016:5758387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traeger MW, Cornelisse VJ, Asselin J, et al. Association of HIV preexposure prophylaxis with incidence of sexually transmitted infections among individuals at high risk of HIV infection. JAMA 2019; 321:1380–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui B, Fairley CK, Chen M, et al. Oral and anal sex are key to sustaining gonorrhoea at endemic levels in MSM populations: A mathematical model. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91:365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grov C, Jonathan Rendina H, Patel VV, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with the use of HIV serosorting and other biomedical prevention strategies among men who have sex with men in a US nationwide survey. AIDS Behav 2018; 22:2743–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth EA, Cui Z, Rich A, et al. Seroadaptive strategies of Vancouver gay and bisexual men in a treatment as prevention environment. J Homosex 2018; 65:524–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prestage G, Maher L, Grulich A, et al. Brief report. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2019; 81:52–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaño MA, Dombrowski JC, Dasgupta S, et al. Changes in sexual behavior and STI diagnoses among MSM initiating PrEP in a clinic setting. AIDS Behav 2019; 23:548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce E, Chan DJ, Smith DE. Empiric antimicrobial treatment for asymptomatic sexual contacts of sexually transmitted infection in the era of antimicrobial resistance: Time to rethink? Int J STD AIDS 2019; 30:137–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low S, Varma R, McIver R, et al. Provider attitudes to the empiric treatment of asymptomatic contacts of gonorrhoea. Sex Health 2020; 17:155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaydos CA, Ako M-C, Lewis M, et al. Use of a rapid diagnostic for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae for women in the emergency department can improve clinical management: Report of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med 2019; 74:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S, Kohn R, Bacon O, et al. O14.4 implementation of point of care gonorrhea and chlamydia testing in an STD clinic PrEP program, San Francisco, 2017–2018. Sex Transm Infect 2019; 95:A71–A72. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazan JA, Carr Reese P, Esber A, et al. High prevalence of rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia infection in women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015; 24:182–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barry PM, Kent CK, Philip SS, et al. Results of a program to test women for rectal chlamydia and gonorrhea. Obstet Gynecol 2010; 115:753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garner AL, Schembri G, Cullen T, et al. Should we screen heterosexuals for extra-genital chlamydial and gonococcal infections? Int J STD AIDS 2015; 26:462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bamberger DM, Graham G, Dennis L, et al. Extragenital gonorrhea and chlamydia among men and women according to type of sexual exposure. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46:329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]