Abstract

Local interstellar spectra (LIS) for protons, helium, and antiprotons are built using the most recent experimental results combined with state-of-the-art models for propagation in the Galaxy and heliosphere. Two propagation packages, GALPROP and HelMod, are combined to provide a single framework that is run to reproduce direct measurements of cosmic-ray (CR) species at different modulation levels and at both polarities of the solar magnetic field. To do so in a self-consistent way, an iterative procedure was developed, where the GALPROP LIS output is fed into HelMod, providing modulated spectra for specific time periods of selected experiments to compare with the data; the HelMod parameter optimization is performed at this stage and looped back to adjust the LIS using the new GALPROP run. The parameters were tuned with the maximum likelihood procedure using an extensive data set of proton spectra from 1997 to 2015. The proposed LIS accommodate both the low-energy interstellar CR spectra measured by Voyager 1 and the high-energy observations by BESS, Pamela, AMS-01, and AMS-02 made from the balloons and near-Earth payloads; it also accounts for Ulysses counting rate features measured out of the ecliptic plane. The found solution is in a good agreement with proton, helium, and antiproton data by AMS-02, BESS, and PAMELA in the whole energy range.

Keywords: cosmic rays, diffusion, elementary particles, interplanetary medium, ISM: general, Sun: heliosphere

1. Introduction

Considerable advances in the astrophysics of cosmic rays (CRs) in recent years have become possible owing to superior instrumentation launched into space and to the top of the atmosphere. The launch of the Payload for Antimatter Matter Exploration and Light-nuclei Astrophysics (PAMELA; Picozza et al. 2007) in 2006, followed by the Fermi Large Area Telescope (Fermi-LAT; Atwood et al. 2009) in 2008 and the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer-02 (AMS-02; Aguilar et al. 2013) in 2011, signify the beginning of a new era in astrophysics. New materials and technologies employed by these space missions have enabled measurements with unmatched precision, which allows for searches of subtle signatures of new phenomena in CR and γ-ray data.

These advances are built on solid results of earlier missions. Understanding the origin of CRs, their acceleration mechanisms, main features of the interstellar propagation, and CR source composition would be impossible without extraordinary efforts of the teams built around the Cosmic Ray Isotope Spectrometer (CRIS) on board NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE; Stone et al. 1998), the Super Trans-iron Galactic Element Recorder (SuperTIGER, Binns et al. 2014), and other (earlier) experiments such as ATIC, BESS, CAPRICE, CREAM, HEAO-3, HEAT, ISOMAX, TIGER, TRACER, Ulysses, and others. Launched in 1977 at the dawn of the space era, the Voyager 1, 2 spacecraft (Stone et al. 1977) demonstrate unbelievable scientific longevity, providing unique data on the elemental spectra and composition at the interstellar reaches of the solar system, currently at 138 au and 114 au from the Sun, correspondingly. Other high-expectation missions have recently been launched (like the CALorimetric Electron Telescope—CALET; Adriani et al. 2015; and the Dark Matter Particle Explorer—DAMPE; Azzarello et al. 2016) or are awaiting launch (Cosmic-ray Energetics and Mass investigation—ISS-CREAM; Seo et al. 2014).

Indirect CR measurements are made by multiwavelength observatories. Fermi-LAT is mapping the all-sky diffuse γ-ray emission, produced by CR interactions in the interstellar medium (ISM), and near CR accelerators. The International Gamma-ray Astrophysics Laboratory (INTEGRAL; Winkler et al. 2003), the High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory ((HAWC; Abeysekara et al. 2013), the High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.; Hinton & Hofmann 2009), the Major Atmospheric Gamma-ray Imaging Cherenkov Telescopes (MAGIC; Aleksić et al. 2016), and the Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS; Holder et al. 2006) observe keV–TeV emissions produced by CR particles in various environments. Construction of the first pre-production telescopes of the next-generation Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA; Acharya et al. 2013) will begin in 2018. High-resolution data in the microwave domain are provided by the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP; Bennett et al. 2003) and Planck (Tauber et al. 2010).

Our understanding of CR propagation in the Milky Way comes from a combination of observational data and a strong theoretical effort (see Strong et al. 2007). Interpretation of many different kinds of data with a self-consistent model requires a state-of-the-art numerical tool that combines the latest information on the Galactic structure (distributions of gas, dust, radiation, and magnetic fields) with the latest formalisms describing particle and nuclear cross sections and theoretical description of the processes in the ISM. This was realized about 20 years ago, when some of us started to develop the most advanced fully numerical CR propagation code, called GALPROP13 (Moskalenko & Strong 1998; Strong & Moskalenko 1998). Over these years the project was widely recognized as a standard model for Galactic CR propagation and associated diffuse emissions (radio, X-rays, γ-rays). GALPROP uses information from astronomy, particle physics, and nuclear physics to predict, in a self-consistent manner, CR fluxes, γ-rays, synchrotron emission, and its polarization (see Strong et al. 2007), like a puzzle being assembled from the results of individual measurements in physics and astronomy spanning in energy coverage, types of instrumentation, and the nature of detected species and emissions. The project stimulated studies of the interstellar gas (H2, Hi, Hii), interstellar radiation and magnetic fields, and isotopic and particle production cross sections. These studies provide unique input data sets for the GALPROP model.

An accurate description of propagation of CR particles through the heliosphere in the last ~130 au, which is a minuscule distance by the Galactic scale, was a considerable challenge until now. These last 0.0006 pc are so important because they provide a link between the predictions of the interstellar propagation models and the location where 99.9% of all direct CR measurements are made. Even though the heliospheric modulation affects only particles with small to medium energies below 30–50 GeV, this range includes the sub-GeV energies where the most precise measurements of CR isotopic composition are made. These low-energy data are used to derive the parameters of interstellar propagation that are then extrapolated onto the whole Galaxy and all energies up to the multi-TeV region. Therefore, an improvement in the description of the heliospheric propagation will have a global impact on our understanding of CR phenomena in the whole Galaxy, i.e., it is where many “ends” meet.

The transport of Galactic protons inside the heliosphere was initially treated by Parker (1965), who demonstrated that—in the framework of statistical physics—the random walk of the CR particles is a Markov process that can be described by a Fokker–Planck equation (e.g., see also Axford 1965; Fisk 1976; Potgieter et al. 1993; see also Sections 8.2.4–8.2.4.3 of Leroy & Rancoita 2016, and references therein). However, in most applications the effect of solar modulation was treated using the simplest force-field approximation (Gleeson & Axford 1967, 1968), in which the diffusion tensor is approximated by a scalar and the resulting modulation effects are expressed with a spherically symmetric modulated differential number density. This was “matched” by the uniform Leaky-Box model for Galactic propagation—a combination that dominated the CR interpretation landscape in the second part of the twentieth century and in the beginning of the twenty-first. With the development of sophisticated Galactic propagation models, the force-field approximation became the Achilles’ heel of CR astrophysics. More advanced models did exist—including those accounting for the so-called “charge drift effect” (e.g., Jokipii et al. 1977; Burger 2012), whose experimental evidence was provided, for instance, by Garcia-Munoz et al. (1986) and Boella et al. (2001)—but they were not as “user friendly” and their wide practical application was suppressed by the high “threshold” demand of expertise in heliospheric physics.

The first ever CR measurements made by Voyager 1 outside of the heliosphere, representing the figurative 0.1% of all direct CR measurements, have an impact of many orders of magnitude larger than their “nominal value.” Combined with the measurements of spectra of Galactic CR species over the past two decades at various levels of solar activity, they provide a synergetic effect that enables us finally to get a grip on CR propagation in those most important 10−9 pc3, which represent the heliospheric volume.

The Voyager 1 data, combined with recent AMS-02, PAMELA, and earlier BESS-Polar measurements, triggered a series of papers (Cholis et al. 2016; Corti et al. 2016; Ghelfi et al. 2016) aiming at the derivation of the LIS for protons and He, and producing a generalization of the modulation potential that depends on time, charge sign, and rigidity, using the force-field approximation (Gleeson & Axford 1968) as a baseline. The parameterizations proposed in these papers and the correlations with the neutron monitor rate, the tilt angle of the heliospheric current sheet, and the polarity and strength of the heliospheric magnetic field (HMF) they found are certainly a large step forward compared to the use of the simple force-field approximation in the not-so-distant past. Meanwhile, these results remain semipheno-menological as they search for correlations rather than solving a proper equation for particle transport in the heliosphere. Another study (Bisschoff & Potgieter 2016) combines Voyager 1 and PAMELA data together with the GALPROP calculations for interstellar propagation to derive the proton, He, and carbon LIS, but lacks a proper study of the propagation parameter space for both interstellar and heliospheric propagation.

In this paper, we use a recently developed version of a 2D Monte Carlo code for heliospheric propagation (the HelMod14 model; Bobik et al. 2012, 2013a, 2016) combined with GALPROP to take advantage of significant progress in CR measurements to derive the LIS for protons, helium, and antiprotons. The HelMod model includes all relevant effects and, thus, a full description of the diffusion tensor. HelMod allows an accurate calculation of the heliospheric modulation for an arbitrary epoch and is fully compatible with GALPROP. It provides an accurate calculation of heliospheric propagation for particles with rigidities above 1 GV.

2. GALPROP Model for CR Production and Propagation in the Galaxy

The GALPROP model for CR propagation is being continuously developed in order to provide a framework for theoretical studies of CR propagation in the Galaxy and interpretation of relevant observations (for more details see Moskalenko & Strong 1998, 2000; Strong & Moskalenko 1998; Strong et al. 2000, 2004, 2007; Moskalenko et al. 2002, 2003; Ptuskin et al. 2006; Trotta et al. 2011; Vladimirov et al. 2011, 2012; Jóhannesson et al. 2016). GALPROP numerically solves the system of time-dependent partial differential equations describing the particle transport with a given source distribution and boundary conditions for all CR species.

Despite its relative simplicity, the diffusion equation is remarkably successful at modeling transport processes in the ISM. The processes involved include diffusive reacceleration and convection (Galactic wind), and for nuclei, nuclear spallation, production of secondary particles and isotopes, radioactive decay, electron K-capture, and stripping, in addition to energy losses due to ionization and Coulomb scattering. For CR electrons and positrons, important processes are the electron knock-on at low energies and the energy losses due to ionization, Coulomb scattering, bremsstrahlung (with the neutral and ionized gas), inverse Compton (IC) scattering, and synchrotron emission. Secondary antiproton production in pp-, pA- and AA-interactions is calculated using the results of QGSJET-IIm (Kachelriess et al. 2015), a dedicated version of the QGSJET-II hadronic interaction model, while inelastically scattered protons and antiprotons are treated as “secondary” protons and “tertiary” antiprotons, respectively.

Galactic properties on large scales, including the diffusion coefficient, halo size, Alfvén velocity, and/or convection velocity, as well as the mechanisms and sites of CR acceleration, can be probed by measuring isotopic abundances and spectra of primary and secondary CR species. The ratio of the halo size to the diffusion coefficient can be constrained by measuring the abundance of stable secondaries, such as, e.g., 5B. The measured abundances of radioactive isotopes (, , , ) then allow the remaining degeneracy to be lifted, resulting in the independent determination of the halo size and the diffusion coefficient (e.g., Ptuskin & Soutoul 1998; Strong & Moskalenko 1998; Webber & Soutoul 1998; Moskalenko et al. 2001). The interpretation of the peaks observed in the secondary-to-primary ratios (e.g., 5B/6C, [21Sc+22Ti+23V]/26Fe) around energies of a few GeV/nucleon was debated in the literature, but the reacceleration model (Berezinskii et al. 1990; Seo & Ptuskin 1994) with a Kolmogorov (1941) spectrum of interstellar turbulence received strong support from new data on the B/C ratio by PAMELA (Adriani et al. 2014) and AMS-02 (Aguilar et al. 2016b).

Closely related to the CR propagation is the production of the Galactic diffuse γ-rays (Strong et al. 2000, 2004) and synchrotron emission (Strong et al. 2011; Orlando & Strong 2013). Proper modeling of the diffuse γ-ray emission, including the disentanglement of the different components, is impossible without well-developed models for distributions of the interstellar gas and radiation field (see, e.g., Strong et al. 2007; Porter et al. 2008; Ackermann et al. 2012). Global CR-related properties of the Milky Way galaxy are discussed in Strong et al. (2010).

The GALPROP project now has nearly 20 years of development behind it. The key idea behind GALPROP is that all CR-related data, including direct measurements, γ-rays, synchrotron radiation, etc., are subject to the same Galactic physics and must therefore be modeled simultaneously. The original FORTRAN90 code has been public since 1998, and a rewritten C++ version was produced in 2001. The latest major public release is v54 (Vladimirov et al. 2011). The latest released version and supplementary data sets are available through a WebRun interface at the dedicated website. The website also contains links to all GALPROP publications and has detailed information on CR propagation and the GALPROP code.

In this work we use the newly developed version 55 of the GALPROP code, which is described in Moskalenko et al. (2015) and references therein. The current version has the possibility to vary the injection spectrum independently for each isotope. It also includes the progenitor/end-nucleus dependency tree prebuilt from the nuclear reaction network and made for each species to ensure that its dependencies are propagated before the source term is generated. This way, special cases of β−-decay (e.g., 10Be → 10B) are treated properly in one pass of the reaction network, instead of the two passes required before, thus providing a significant gain in speed.

2.1. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

MCMC methods are a class of algorithms for sampling from a probability distribution, based on a Markov chain that has the desired distribution as its equilibrium distribution. The link between the target distribution of the parameters and the experimental data is given by the likelihood function. These techniques are widely applied to give posterior multidimensional parameter constraints from observational data and have a low computational cost, because they scale about linearly with the number of parameters. The MCMC interface to the development version of GALPROP was adapted from CosRayMC (Liu et al. 2012) and, in general, from the COSMOMC package (Lewis & Bridle 2002), embedding a GALPROP framework into the MCMC scheme. An iterative procedure was developed to feed the GALPROP output into HelMod, which provides modulated spectra for specific time periods to compare with AMS-02 data as observational constraints.

The basic features of CR propagation in the Galaxy are well known, but the exact values of propagation parameters depend on the assumed propagation model and accuracy of selected CR data. Therefore, we use the MCMC procedure to determine the propagation parameters using the best available CR measurements. Six main propagation parameters that affect the overall shape of CR spectra were left free in the scan using the 2D GALPROP model: the Galactic halo half-width z, the normalization of the diffusion coefficient D0 at the reference rigidity RD = 4.5 GV and the index of its rigidity dependence δ, the Alfvén velocity VAlf, and the convection velocity and its gradient (Vconv, dVconv/dz). It is commonly accepted that the spatial distribution of CRs only weakly depends on the chosen radial size of the Galaxy, which is set to 20 kpc. Besides, to correctly fit the AMS-02 proton data at low energies and to maintain a good agreement above 200 MV with Voyager 1 data (see Section 5.1), we introduced a factor βη in the diffusion coefficient, where β = ν/c and η was left free: the best-fit value of η is 0.91 (see Table 1), very close to 1, so it has no effect on the LIS of the nuclei.

Table 1.

Propagation Parameters, Obtained with the MCMC Posterior Distributions and the GALPROP-HelMod Calibration

| N | Parameter | Best Value | Units | 1σ Mean Error | % Error | Scan Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | z | 4.0 | kpc | 0.7 | 18 | [1–10] |

| 2 | D0/1028 | 4.3 | cm2 s−1 | 0.5 | 12 | [1–10] |

| 3 | δ | 0.395 | … | 0.025 | 6 | [0.3–0.9] |

| 4 | V Alf | 28.6 | km s−1 | 3.0 | 10 | [0–40] |

| 5 | V conv | 12.4 | km s−1 | 0.8 | 6 | [0–20] |

| 6 | dVconv/dz | 10.2 | km s−1 kpc−1 | 0.7 | 7 | [0–20] |

| 7 | η | 0.91 | … | 0.05 | 5 | [0.8–1.2] |

Parameters of the injection spectra, such as spectral indices and the break rigidities, were also left free, but their exact values depend on the solar modulation, so the low-energy parts of the spectra are tuned together with the solar modulation parameters as detailed below. To refine the LIS description, we added smoothing features for the breaks in the injection spectrum. The numerical values of the CR source distribution parameters (Trotta et al. 2011), zscale = 0.2 kpc, α = 1.5, and β = 3.5, remain unchanged for all scans.

The solar modulation is calculated using numerical functions based on HelMod (see Section 3.1); it is implemented within the MCMC sampling procedure, after the GALPROP run and before a comparison with the AMS-02 data is made. At this stage, only nuclei up to Z = 14 are included and their fragmentation and production of secondary isotopes are calculated automatically. Elemental abundances were derived from propagated isotopic abundances, e.g., He = 3He + 4He, with each isotope LIS independently propagated with HelMod. Relative abundances of protons and heavier nuclei at the sources were considered in preliminary scans and revealed only a few percent variation with respect to GALPROP previously derived values (Moskalenko et al. 2008), thus allowing us to exclude them from the main scans. Note that Jóhannesson et al. (2016) came to a similar conclusion.

The high-energy break, or a change of slope, for protons and helium highlighted by CREAM (Ahn et al. 2010; Yoon et al. 2011), PAMELA (Adriani et al. 2011), and AMS-02 (Aguilar et al. 2015a, 2015b) is computed introducing an ad hoc spectral break in the injection spectrum. The position of this high-energy break is tuned to be in agreement with CREAM-I data above the AMS-02 range. A more physical approach is to assume a change in the slope of the diffusion coefficient around 350 GV (Vladimirov et al. 2012). The flattening (hardening) of the proton and helium spectra is then reproduced if the index of the rigidity dependence of the diffusion coefficient δ is reduced above the break rigidity by Δδ ≈ 0.15–0.25, dependently on the propagation model. If this is indeed the case, it can be tested once more accurate spectra for other CR species become available.

The experimental observables used in the MCMC scan include all published AMS-02 data on protons (Aguilar et al. 2015b), helium (Aguilar et al. 2015a), B/C ratio (Aguilar et al. 2016b), and electrons (Aguilar et al. 2014), while positrons and antiprotons are excluded. One of our current goals is to make a prediction of the antiproton spectrum based on other CR data, while inclusion of antiprotons (AMS-02; Aguilar et al. 2016a) into the scan would result in the MCMC procedure attempting to reproduce them and thus biasing our conclusions. In the case of positrons, a significant contribution comes from sources or processes of unknown nature; therefore, their inclusion would only add free parameters that cannot be reliably constrained. The origin of the positron excess will be discussed in a follow-up paper.

Simultaneous inclusion of both reacceleration and convection is needed to describe protons, particularly in the range below 20 GV, where their effects on CR spectra are significant. The chosen ranges for the parameter scan, reported in Table 1, are quite wide and allow the reacceleration and convection to be set to zero if required by the fitting algorithm. The goodness estimator of the parameter scan is the natural logarithm—for computational convenience—of the previously mentioned likelihood function, which is built with the χ2 from all observables: hundreds of thousands of samples were generated, and the log-likelihood was used to accept or reject each sample. The scan is terminated when a good agreement is reached.

Note that the current MCMC setup has several distinct differences from those usually employed in the literature. (i) In the current scan we use p, He, B/C, and e− data from the AMS-02 experiment only, i.e., only data >2 GV are used. For the case of the B/C ratio this means that we use the data above its peak rigidity. (ii) Both reacceleration and convection processes are included simultaneously. (iii) We do not use the force-field approximation. Instead, for the modulation calculations we use the HelMod routine with fixed approximate parameter values as described in detail in Section 3. (iv) The MCMC procedure is used to find the best values and confidence limits for the interstellar propagation parameters and the injection spectra. The interstellar propagation parameters were fixed after this step. (v) A grid of GALPROP models is built using small (within a few percent) variations of the best-fit parameter values found in the previous step. This model grid is used for a fine-tuning of the heliospheric propagation; more details are given in Section 3.

Therefore, the MCMC procedure is used only in the first step to define a consistent parameter space (Figure 1), and then a methodical calibration of the model employing the HelMod Module was performed. Consequently, the best values in Table 1 are not necessarily the most probable values obtained with the MCMC procedure, but the final values that come from the GALPROP-HelMod combined fine-tuning, which involved an exploration of the parameter space around the best values defined in the first step. The associated symmetrical mean errors are derived from the mean of a number of MCMC scans.

Figure 1.

MCMC matrix of 2D constraints for the main propagation parameters. In off-diagonal panels, the inner contours denote 1σ (blue) and 2σ (light blue). The diagonal plots are the 1D probability distributions of the corresponding parameters.

The MCMC scan gives a nonzero value for Vconv = 12.4 km s−1. Strictly speaking, this may look like a discontinuity at z = 0 because the wind direction is outward for both positive and negative z. However, in reality this wind speed is very small compared to the speed of even low-energy CR particles. Taking into account the coarse size of the spatial grid dz = 0.1 kpc, this does not pose any problem for the solution.

The injection spectrum parameters for each species, such as the indices γi below and above the rigidity breaks Ri, have been moved together with solar modulation parameters within physical ranges in order to find best-fit solutions for all the observables (see Section 3). Several MCMC scans in γi and Ri were performed at this step. The resulting best parameters for protons and helium are shown in Table 2. Due to the intercalibration between HelMod and GALPROP parameters, the errors coming from the MCMC scans and shown in Table 2 could somewhat underestimate the total combined errors. The stability of the calculated LIS is tested through variations of five GALPROP converging algorithm parameters (Table 3).

Table 2.

Spectral Parameters for Protons, Helium, and Electrons

| Parameters | p | He | e − | Mean Error | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R 1 | 7 GV | 7 GV | 6 GV | 1 GV | [4–10] |

| R 2 | 360 GV | 330 GV | 100 GV | 10 GV | [300–400] |

| γ 1 | 1.69 | 1.71 | 1.45 | 0.06 | [1.5–2.1] |

| γ 2 | 2.44 | 2.38 | 2.75 | 0.04 | [2.1–2.7] |

| γ 3 | 2.28 | 2.21 | 2.49 | 0.05 | [2–2.4] |

Note. The estimate of the errors is to be considered qualitative, because of correlations between GALPROP and HelMod, uncertainties in the shape of the injection spectra, and lack of definitive data at few TV.

Table 3.

Parameters of the Numerical Scheme

| N | Algorithm Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | dz | 0.1 kpc |

| 2 | Time step factor | 0.75 |

| 3 | Time step repetitions | 30 |

| 4 | Ekin factor | 1.07 |

| 5 | Time propagation interval | 70–109 yr |

Note. See GALPROP Explanatory Supplement for details.

3. HelMod Model for Heliospheric Transport

The observed Galactic CR spectra at Earth vary with time accordingly to solar activity. Their propagation in the heliosphere is affected by the outward flowing solar wind (SW) with its embedded magnetic field and magnetic field irregularities. The so-generated and transported HMF is characterized by both the large-scale structure (SW expansion from a rotating source) and small-scale irregularities that vary with time according to the solar activity (e.g., by modification of SW velocity or local perturbations related to coronal mass ejection [CME]). The SW expansion causes CRs to propagate in a moving medium, which is accounted for in the transport equation by the diffusion and adiabatic energy loss terms. In addition, according to the original formulation by Parker (1958), the HMF follows an Archimedean spiral that causes charged particles (i.e., CRs) to experience a combination of gradient, curvature, and current sheet drifts (see, e.g., Jokipii et al. 1977), whose experimental evidence was provided, for instance, by Garcia-Munoz et al. (1986) and Boella et al. (2001). The overall effect of heliospheric propagation on the spectra of Galactic CRs is called solar modulation.

CR propagation in the heliosphere was first studied by Parker (1965), who formulated the transport equation, also referred to as the Parker equation (see, e.g., discussion in Bobik et al. 2012, and references therein):

| (1) |

where U is the number density of Galactic CR particles per unit of kinetic energy T, t is time, VSW, i is the SW velocity along the axis xi, is the symmetric part of the diffusion tensor, νd,i is the particle magnetic drift velocity (related to the antisymmetric part of the diffusion tensor), and finally αrel = T + 2mrc2/T + mrc2, with mr the particle rest mass in units of GeV/nucleon. The processes included in Equation (1) are extensively discussed in the literature (see, e.g., Potgieter 2016, and references therein). Over the decades of its development (Gervasi et al. 1999a, 1999b; Bobik et al. 2003, 2004, 2006, 2009a, 2009b, 2011, 2012, 2013a, 2016), the HelMod model was built to include all details of the treatment of individual processes, and therefore provides a realistic and unique description of the solar modulation. Here we provide a short description of the HelMod model14 (version 3.0); more details can be found in Bobik et al. (2012, 2013a).

It is widely accepted that components of KS parallel to the magnetic field are larger than its perpendicular components and should be described using nonlinear theories (for a review see, e.g., Shalchi 2009), while at high rigidities (i.e., ≫1 GV) the diffusion tensor should have a linear (or quasi-linear) rigidity dependence (see, e.g., Gloeckler & Jokipii 1966; Jokipii 1966, 1971; Gleeson & Axford 1968; Perko 1987; Potgieter & Le Roux 1994; Strauss et al. 2011). The transition between the nonlinear and quasi-linear regimes results in a “flattening” of rigidities dependence as observed, for instance, by Palmer (1982) and Bieber et al. (1994). In the present work, for rigidities greater than 1 GV, we use a functional form with a rigidity dependence following the one presented in Burger & Hattingh (1998):

| (2) |

where K0 is the diffusion parameter, which depends on the solar activity and magnetic polarity, β is the particle speed in units of the speed of light, P = qc/∣Z∣e is the particle rigidity expressed in GV, r is the heliocentric distance from the Sun in au, and, finally, glow is a parameter that depends on the level of solar activity and allows the description of the flattening with rigidity below a few GV.

As discussed in Section 2.1 of Bobik et al. (2012), the diffusion parameter, K0, is a scaling factor for the overall modulation intensity. It defines the global behavior of the modulation of the particle flux in the heliosphere, and its dependence on time reflects the variations of properties of the interplanetary medium (like the actual solar magnetic field transported by SW and its turbulence) during the different phases of solar cycles (e.g., see Equation (4) in Manuel et al. 2014). K0 is expressed in terms of the monthly smoothed sunspot numbers (SSN); such a relationship was demonstrated to be adequate for the description of how the diffusion parameter depends on solar activity and polarity15 (see also discussion in Section 2.3 of Boschini et al. 2017). Therefore, the effective modulation experienced by CRs is related to the solar activity and polarity of the magnetic field. This approximation is valid as long as disturbances coming from the Sun (like, CME) are short, are not very frequent, and do not significantly affect the average behavior of the heliospheric medium.

During periods of high solar activity, the rate of CMEs increases, leading to a more chaotic structure of magnetic field and stronger turbulence; thus, the HMF cannot be properly described by a dipole configuration. To improve the practical relationship between K0 and solar activity, we use the neutron monitor counting rate (NMCR). In the current work, we exploit the NMCR recorded by the McMurdo station and available through the Neutron Monitor Database (Klein et al. 2009) following the same fitting procedure used in Section 2.1 of Bobik et al. (2012). The NMCR allows us to account for short-time and large-scale variations occurring during the high solar activity periods, and thus to rescale the diffusion parameter accordingly. However, the usage of NMCR during the low solar activity periods does not result in an appreciable difference; thus, we keep using SSN (Boschini et al. 2017) as the activity indicator for such periods.

Furthermore, it has to be remarked that there is no commonly accepted theory describing the diffusion in strong turbulence that could be successfully applied to the heliosphere. For the sake of simplicity, at solar maximum, we adopt a linear dependence of K∥ on rigidity, i.e., glow = 0 in Equation (2), that is in qualitative agreement with simulations performed for strong turbulence conditions as shown in Figures 3.5 and 6.5 of Shalchi (2009). Due to the lack of data, the transition periods between low and high activity are estimated using a smooth function that is assigned glow = 0 during the high activity and becomes glow = 0.3 during the low-activity periods. Such intermediate periods are discussed in Section 5.3.3.

In this model, the spatial dependence shows a radial dependence ∝r and is consistent with the one used in Bobik et al. (2013a), but has no latitudinal dependence (see also discussions in Jokipii & Kota 1989; McDonald et al. 1997; Strauss et al. 2011). The perpendicular diffusion coefficient is taken to be proportional to K∥ with a ratio K⊥,i/K∥ = ρi for both r and θ i-coordinates (see, e.g., Burger & Hattingh 1998; Potgieter 2000, and references therein). At high rigidities, this description is consistent with quasi-linear theories. Palmer (1982) constrains the value of ρi between 0.02 and 0.08 at Earth. We found best agreement at ρi ≈ 0.06. As remarked in Bobik et al. (2013a), in this description K∥ has no latitudinal dependence and a radial dependence ∝r; nevertheless, the reference frame transformation from the field-aligned to the spherical heliocentric frame (see, e.g., Burger et al. 2008) introduces a dependence on the polar angle. As was shown in Bobik et al. (2013a), this is sufficient to explain the latitudinal gradient observed by Ulysses during the latitudinal fast scan in 1995 (see, e.g., Heber et al. 1996; Simpson et al. 1996).

In the present work, we use the drift model originally developed by Potgieter & Moraal (1985) and refined using definitions of Parker’s magnetic field with polar correction as reported in Bobik et al. (2013a) (see also Raath et al. 2016, for a discussion about modified Parker’s magnetic field):

| (3) |

where θ is the solar colatitude, νdr is related to the large-scale structure of HMF, f(θ) accounts for the effects of a wavy neutral sheet on transport properties in the large-scale structure of HMF, and, finally, νHCS describes the drift velocity along the neutral sheet (see Section 4 of Bobik et al. 2012). Since during the high-activity period the HMF is far from being considered regular, in this work we introduced a correction factor that suppresses any drift velocity at solar maximum. For the sake of completeness we should note that the presence of turbulence in the interplanetary medium should reduce the global effect of CR drift in the heliosphere (see, e.g., discussion in Minnie et al. 2007), and this is usually incorporated by introducing a drift suppression factor (see, e.g., Strauss et al. 2011) that is effective at rigidity below 1 GV.

We compute the CR propagation from the termination shock (TS) down to the Earth’s orbit using the HelMod Monte Carlo code (Bobik et al. 2012), which solves the 2D Parker equation for CR transport through the heliosphere. The HelMod code applies the stochastic integration to a set of stochastic differential equations (SDEs), which are fully equivalent to Equation (1) (see a discussion in, e.g., Bobik et al. 2012, 2016). In this scheme, quasi-particle objects evolve backward in time from the location of the detector, i.e., from Earth, back to the TS. The modulated spectrum is then obtained by averaging the evaluated LIS fluxes, which takes into account the reconstructed rigidity at the heliospheric boundary (see Section 4.1.2 in Bobik et al. 2016).

The goodness of the model is evaluated using the χ2 minimization (see, e.g., Section 15.1 of Press et al. 1992):

| (4) |

where JHelMod is the differential intensity evaluated using the HelMod code, Jexp is the observed differential intensity, Ri is the average rigidity of the ith rigidity bin of the differential intensity distribution, and σi is the experimental error corresponding to the ith rigidity bin. This quantity is evaluated for rigidities below 20 GV. We minimize χ2 for all selected experiments for both high and low levels of solar activity.

Among the HelMod parameters described before, only two of them are directly involved in the determination of a LIS: ρi and glow. In fact, ρi modifies the absolute scale of modulation intensity up to high rigidities; since this parameter also influences latitudinal gradients, its value is constrained in such a way that the obtained latitudinal gradients are in agreement with those found by Ulysses and presented in Section 5.2. The maximum value of glow refines modulated differential intensity in the low rigidity range (<3 GV), involving mainly low-activity periods.

The procedure of intercalibration between HelMod and GALPROP is set up as follows. In the initial step, starting LIS are coming from a previous study (i.e., Bobik et al. 2012). (i) Minimization of HelMod parameters in Table 4, Equation (4), is done on a large set of proton spectra measured along solar cycles 23–24 (i.e., Shikaze et al. 2007; Aguilar et al. 2002, 2015b; Adriani et al. 2013; Maurin et al. 2014; Abe et al. 2016). (ii) The HelMod-tuned modulation obtained in the previous step is used with the GALPROP MCMC procedure, described in Section 2.1, which scans Galactic propagation parameters, providing a new set of LIS (protons, helium nuclei, and antiprotons). (iii) The new calculated LIS are provided as input for a step one minimization (i), producing new modulation functions.

Table 4.

Parameters of the HelMod Model Tuned in the LIS Scans

| HelMod Parameters | Values | Parameter Range |

|---|---|---|

| ρi | 0.06 | 0.055–0.064 |

| glow at solar minimum | 0.3 | 0.0–0.5 |

Once the loop (i)–(iii) is completed a couple of times, step (iii) is replaced with step (iv) as described below, so that the loop now includes steps (i)–(ii)–(iv). In step (iv), a grid of GALPROP models, obtained from variations of Table 2 parameters within a few percent with respect to the best values from MCMC, is tested. The proton LIS from the model that shows the best overall agreement with AMS-02 data are given as input for the HelMod minimization in step (i) again. The tuning between HelMod and GALPROP ends when the difference between the LIS in two subsequent cycles is below 2%. In Table 4 the third column gives the 68% confidence interval for each of the listed HelMod parameters.

In addition, we have investigated the uncertainty in the HelMod code outputs, taking into account that the final results can be affected by the assumed size of the heliosphere, numerical uncertainties, and the goodness of fit for the HelMod parameters. In the current calculation, we assume a static and spherical heliosphere with TS located at 100 au (Bobik et al. 2012). Note that Voyager 1, 2 observations point to a dynamic TS that is moving inward/outward in the heliosphere (Stone et al. 2005; Richardson & Wang 2011), while numerical models indicate that this TS movement could be as large as ~20 au over a complete solar cycle (see discussion in Manuel et al. 2015, and references therein). In the HelMod framework, this is equivalent to a rescaling of the real size of the heliosphere to a reference size of 100 au. For example, if a location of the TS is changing by 10 au (see, e.g., Washimi et al. 2011), then Earth’s position in the rescaled HelMod heliosphere is moving by 0.1 au. Monte Carlo simulations show that such small variations of the location of Earth do not affect the solutions; thus, for the rest of the paper we assume that the detector is located at 1 au. Even though variations of the real size of the heliosphere may be important for the analysis of CR propagation near the TS, we do not consider them in this work.

The numerical uncertainties of our Monte Carlo approach were evaluated in Bobik et al. (2016), who employed the Crank–Nicholson technique for the SDE integration and found them to be less than 0.5% at low rigidities. The large number of simulated events ensures that the statistical errors are negligible compared to the other modeling uncertainties. Finally, we evaluate the probability distributions of HelMod parameters assuming Δχ2 with respect to the minimizing configuration that is compatible with the 68% confidence interval (see, e.g., Section 15.6 of Press et al. 1992). The total errors corresponding to this confidence interval are quoted in Section 5, while the intervals obtained from the computed errors are reported in the third column of Table 4. Note that the errors increase at lower rigidities.

3.1. HelMod Python Module for GALPROP

The HelMod SDE integration calculations are computationally expensive because minimization of uncertainties requires a simulation of a considerable number of events propagating from Earth to the heliospheric boundary. The modulated spectrum is usually evaluated directly from the numerical integration using the procedure described in Bobik et al. (2016, and references therein) that forces a new simulation run for each LIS to be tested. On the other hand, the Monte Carlo integration allows us to evaluate the normalized probability function G(R0∣R), which gives a probability for a particle observed at Earth with a rigidity R0 having a rigidity R at the heliospheric boundary. The modulated spectrum at specific rigidity R0 is proportional to (see, e.g., Pei et al. 2010)

| (5) |

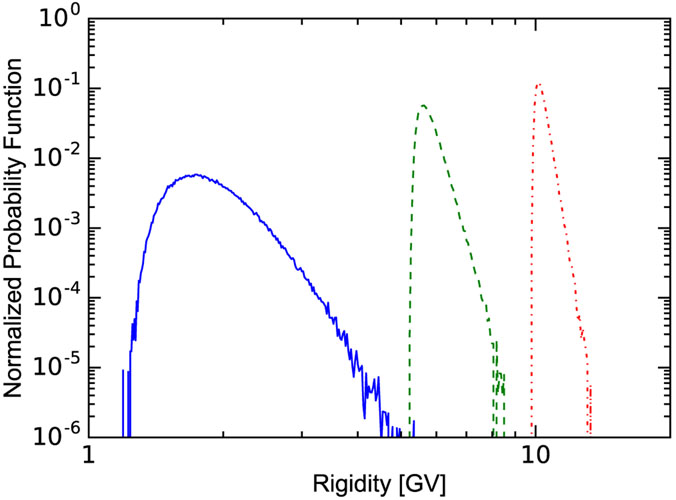

Once G(R0∣R) is evaluated, it is possible to obtain the modulated spectrum directly from JLIS provided by GALPROP. For illustration, in Figure 2 we show the computed normalized probability function for R0 = 1.1, 5.1, and 9.7 GV evaluated for protons during the period 2011–2014, equivalent to the data-taking period of released AMS-02 data (Aguilar et al. 2015b).

Figure 2.

Computed normalized probability function G(R0∣R) for R0 = 1.1, 5.1, and 9.7 GV (left to right) evaluated for AMS-02 proton binning during the period 2011–2014; see the text for details.

To simplify the calculations, we developed a python script that reads the GALPROP output and provides the modulated spectrum for periods of selected experiments. The calculation of propagation in the heliosphere is substituted by the integration of Equation (5) with the normalized probability functions, which are pre-evaluated using the HelMod code as described in the previous section. This method dramatically accelerates the modulation calculations while providing the accuracy of the full-scale simulation.

The normalized probability functions were evaluated for several CR species (p, He, B/C, e−) as described in Section 2.1. Fine tuning of the GALPROP and HelMod model parameters was done using proton simulations and minimization of χ2 for a set of selected experiments running from 1997 to 2015 (Shikaze et al. 2007; Aguilar et al. 2002, 2015b; Adriani et al. 2013; Maurin et al. 2014; Abe et al. 2016).

The HelMod python module can be downloaded from a dedicated website14 or used online. It reads the GALPROP output format (FITS) and provides a modulated spectrum for a specified period of time. While the heliospheric propagation is fixed by using the provided functions G(R0∣R), the LIS spectrum can be specified by a user. The output rigidity binning is chosen to be compatible with CR experiments in the specified period; alternatively, the AMS-02 rigidity binning is chosen as the standard for results not directly associated with observational data.

4. Interstellar Propagation

The results of the calculations show that simultaneous inclusion of diffusion, convection, and reacceleration is required to reproduce AMS-02 measurements, while plain diffusion scenarios are excluded (Strong et al. 2007). Because the spectra of p, He, and heavier nuclei are well reproduced in the standard interstellar propagation model, they can be used to put constraints on heliospheric propagation. On the other hand, having the heliospheric modulation constrained reduces the uncertainties associated with the interstellar propagation (Tables 1 and 2) and provides up to an order of magnitude improvement in the accuracy compared to other analyses (Maurin et al. 2001, 2002; Dorman 2006; Stanev 2010; Cirelli et al. 2011; Trotta et al. 2011; Coste et al. 2012; Tomassetti & Donato 2012; Masi 2013). For example, estimates of the index of the rigidity dependence of the diffusion coefficient δ in the literature span from δ = 0.33–0.5 for Kolmogorov and Kraichnan spectra of interstellar turbulence to δ = 0.6–0.9 for plain diffusion models. In our analysis, the errors associated with the determination of the major propagation parameters are reduced to ~5%–10%. For primaries, the overall uncertainties in their spectra are so small that they are not reported in Section 5.3; some degeneracies, which affect secondary predictions, still persist and could partially account for small discrepancies with AMS-02 antiproton data.

The combined diffusion–convection–reacceleration (DCR) model has a uniform spatial diffusion coefficient (D0x = D0z) with a single power-law index (δ1 = δ2) over the entire rigidity range. The index δ of the rigidity dependence of the diffusion coefficient is derived from the slope of the secondary-to-primary ratio (e.g., B/C). A fit to the AMS-02 measurements of the B/C ratio (Aguilar et al. 2016b) yields 0.395, which is very close to the value δ = 0.397 ± 0.007 found from the fit to the PAMELA data (Adriani et al. 2014) and quite close to the Kolmogorov index of 1/3.

The acceleration and diffusion processes depend on the particle rigidity, and until recently the injection rigidity spectra were assumed to be the same for all nuclei. Discrepancies in the proton and He spectra were noticed in CREAM (Ahn et al. 2010; Yoon et al. 2011) and PAMELA data (Adriani et al. 2011), with the AMS-02 data (Aguilar et al. 2015a, 2015b) providing ultimate evidence for the difference Δγ ≈ 0.07–0.08 in the spectral indices of CR protons and He. The origin of this difference is debated in the literature, but there is no consensus yet (Vladimirov et al. 2012). Fitting these data requires the injection indices to be different for different nuclei species and hints that further fine-tuning may be necessary for heavier nuclei Z ⩾ 6. In turn, this may affect the calculation of the B/C ratio and the propagation parameters; other effects, such as production of secondary He, N, C etc., from spallation of heavier nuclei, are automatically taken into account in GALPROP. As an example, in our propagation runs, the primary helium accounts for 94% of the total around 1 GeV/nucleon and 98% at 100 GeV/nucleon, whereas the primary carbon accounts for 74% of the total around 1 GeV/nucleon and 87% at 100 GeV/nucleon. Therefore, precise measurements of heavier nuclei by AMS-02 will impose tighter constraints on CR production and propagation.

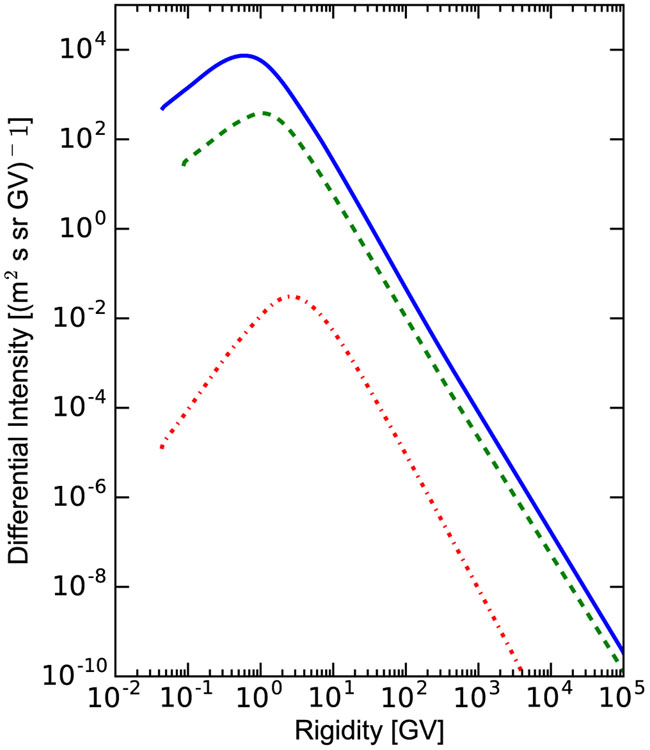

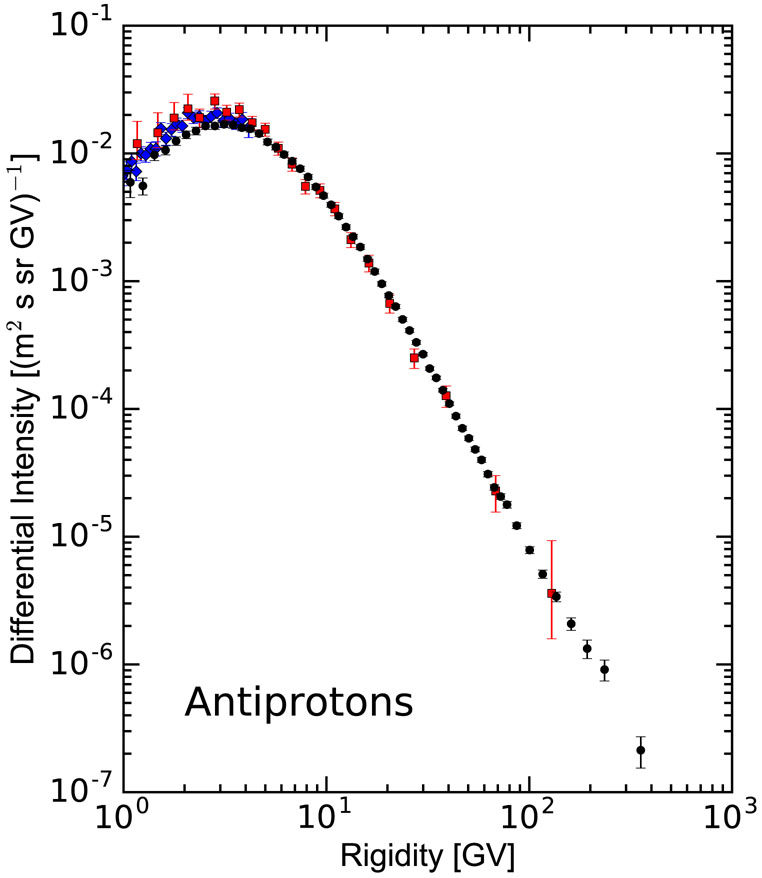

The p, He, and LIS derived with the described MCMC procedure and HelMod-GALPROP intercalibration (using all nuclei up to Z = 28) are shown in Figure 3 as functions of rigidity and tabulated in the Appendix, in Tables 6-8. A comparison with the data is discussed in detail in Sections 5 and 5.1. In addition to the tabulated data, we provide analytical fits to the derived LIS. The fit to the antiproton LIS provides an accuracy of 2%–3% for 3 GV < R < 1000 GV and 10% for 1.5 GV < R < 3 GV,

| (6) |

while the average accuracy of AMS-02 data is about 10%–20%. The expressions for proton and helium LIS are given in Section 5.1.

Figure 3.

Local interstellar spectra of CR protons (blue solid line), helium (green dashed line), and antiprotons (red dot-dashed line) as derived from the MCMC procedure (see text).

Table 6.

Proton LIS

| Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.333e−02 | 2.971e+02 | 2.814e−01 | 4.265e+03 | 2.473e+00 | 1.180e+03 | 7.145e+01 | 1.226e−01 | 2.914e+03 | 4.554e−06 |

| 4.482e−02 | 3.772e+02 | 2.913e−01 | 4.411e+03 | 2.600e+00 | 1.054e+03 | 7.639e+01 | 1.014e−01 | 3.118e+03 | 3.799e−06 |

| 4.636e−02 | 4.101e+02 | 3.016e−01 | 4.557e+03 | 2.736e+00 | 9.393e+02 | 8.167e+01 | 8.382e−02 | 3.336e+03 | 3.169e−06 |

| 4.796e−02 | 4.325e+02 | 3.123e−01 | 4.703e+03 | 2.880e+00 | 8.337e+02 | 8.732e+01 | 6.927e−02 | 3.570e+03 | 2.643e−06 |

| 4.961e−02 | 4.531e+02 | 3.233e−01 | 4.849e+03 | 3.033e+00 | 7.377e+02 | 9.337e+01 | 5.725e−02 | 3.820e+03 | 2.204e−06 |

| 5.132e−02 | 4.738e+02 | 3.348e−01 | 4.992e+03 | 3.197e+00 | 6.509e+02 | 9.984e+01 | 4.731e−02 | 4.087e+03 | 1.839e−06 |

| 5.308e−02 | 4.953e+02 | 3.466e−01 | 5.134e+03 | 3.371e+00 | 5.726e+02 | 1.067e+02 | 3.909e−02 | 4.373e+03 | 1.534e−06 |

| 5.491e−02 | 5.178e+02 | 3.590e−01 | 5.273e+03 | 3.557e+00 | 5.024e+02 | 1.141e+02 | 3.230e−02 | 4.679e+03 | 1.279e−06 |

| 5.680e−02 | 5.414e+02 | 3.718e−01 | 5.408e+03 | 3.755e+00 | 4.396e+02 | 1.221e+02 | 2.669e−02 | 5.007e+03 | 1.067e−06 |

| 5.876e−02 | 5.660e+02 | 3.851e−01 | 5.539e+03 | 3.966e+00 | 3.838e+02 | 1.305e+02 | 2.205e−02 | 5.357e+03 | 8.901e−07 |

| 6.078e−02 | 5.919e+02 | 3.988e−01 | 5.665e+03 | 4.192e+00 | 3.342e+02 | 1.396e+02 | 1.821e−02 | 5.732e+03 | 7.424e−07 |

| 6.288e−02 | 6.190e+02 | 4.132e−01 | 5.785e+03 | 4.432e+00 | 2.904e+02 | 1.493e+02 | 1.505e−02 | 6.133e+03 | 6.192e−07 |

| 6.504e−02 | 6.474e+02 | 4.280e−01 | 5.899e+03 | 4.689e+00 | 2.518e+02 | 1.597e+02 | 1.243e−02 | 6.562e+03 | 5.164e−07 |

| 6.729e−02 | 6.772e+02 | 4.435e−01 | 6.006e+03 | 4.963e+00 | 2.178e+02 | 1.708e+02 | 1.027e−02 | 7.022e+03 | 4.307e−07 |

| 6.960e−02 | 7.085e+02 | 4.596e−01 | 6.104e+03 | 5.256e+00 | 1.880e+02 | 1.827e+02 | 8.483e−03 | 7.513e+03 | 3.592e−07 |

| 7.200e−02 | 7.412e+02 | 4.763e−01 | 6.194e+03 | 5.569e+00 | 1.620e+02 | 1.955e+02 | 7.007e−03 | 8.039e+03 | 2.996e−07 |

| 7.448e−02 | 7.756e+02 | 4.937e−01 | 6.274e+03 | 5.903e+00 | 1.392e+02 | 2.091e+02 | 5.787e−03 | 8.602e+03 | 2.499e−07 |

| 7.705e−02 | 8.117e+02 | 5.117e−01 | 6.343e+03 | 6.260e+00 | 1.194e+02 | 2.237e+02 | 4.780e−03 | 9.204e+03 | 2.084e−07 |

| 7.971e−02 | 8.495e+02 | 5.306e−01 | 6.402e+03 | 6.641e+00 | 1.022e+02 | 2.392e+02 | 3.948e−03 | 9.848e+03 | 1.738e−07 |

| 8.246e−02 | 8.893e+02 | 5.501e−01 | 6.449e+03 | 7.049e+00 | 8.735e+01 | 2.559e+02 | 3.261e−03 | 1.053e+04 | 1.449e−07 |

| 8.530e−02 | 9.309e+02 | 5.705e−01 | 6.483e+03 | 7.484e+00 | 7.444e+01 | 2.738e+02 | 2.694e−03 | 1.127e+04 | 1.209e−07 |

| 8.824e−02 | 9.747e+02 | 5.918e−01 | 6.504e+03 | 7.950e+00 | 6.331e+01 | 2.929e+02 | 2.226e−03 | 1.206e+04 | 1.008e−07 |

| 9.128e−02 | 1.020e+03 | 6.139e−01 | 6.512e+03 | 8.448e+00 | 5.372e+01 | 3.133e+02 | 1.840e−03 | 1.290e+04 | 8.410e−08 |

| 9.443e−02 | 1.068e+03 | 6.370e−01 | 6.505e+03 | 8.981e+00 | 4.548e+01 | 3.352e+02 | 1.523e−03 | 1.381e+04 | 7.014e−08 |

| 9.769e−02 | 1.119e+03 | 6.611e−01 | 6.484e+03 | 9.550e+00 | 3.842e+01 | 3.586e+02 | 1.262e−03 | 1.477e+04 | 5.850e−08 |

| 1.010e−01 | 1.172e+03 | 6.863e−01 | 6.447e+03 | 1.015e+01 | 3.239e+01 | 3.836e+02 | 1.049e−03 | 1.581e+04 | 4.878e−08 |

| 1.045e−01 | 1.227e+03 | 7.126e−01 | 6.395e+03 | 1.081e+01 | 2.725e+01 | 4.104e+02 | 8.731e−04 | 1.692e+04 | 4.068e−08 |

| 1.081e−01 | 1.286e+03 | 7.400e−01 | 6.328e+03 | 1.150e+01 | 2.288e+01 | 4.391e+02 | 7.275e−04 | 1.810e+04 | 3.393e−08 |

| 1.118e−01 | 1.347e+03 | 7.687e−01 | 6.244e+03 | 1.225e+01 | 1.918e+01 | 4.698e+02 | 6.067e−04 | 1.937e+04 | 2.829e−08 |

| 1.157e−01 | 1.411e+03 | 7.987e−01 | 6.145e+03 | 1.304e+01 | 1.605e+01 | 5.026e+02 | 5.061e−04 | 2.072e+04 | 2.360e−08 |

| 1.197e−01 | 1.477e+03 | 8.301e−01 | 6.030e+03 | 1.390e+01 | 1.341e+01 | 5.377e+02 | 4.223e−04 | 2.218e+04 | 1.968e−08 |

| 1.238e−01 | 1.548e+03 | 8.629e−01 | 5.900e+03 | 1.481e+01 | 1.119e+01 | 5.753e+02 | 3.523e−04 | 2.373e+04 | 1.641e−08 |

| 1.281e−01 | 1.621e+03 | 8.974e−01 | 5.755e+03 | 1.578e+01 | 9.325e+00 | 6.155e+02 | 2.940e−04 | 2.539e+04 | 1.368e−08 |

| 1.326e−01 | 1.698e+03 | 9.335e−01 | 5.595e+03 | 1.682e+01 | 7.762e+00 | 6.585e+02 | 2.453e−04 | 2.717e+04 | 1.141e−08 |

| 1.372e−01 | 1.778e+03 | 9.713e−01 | 5.422e+03 | 1.794e+01 | 6.455e+00 | 7.046e+02 | 2.047e−04 | 2.907e+04 | 9.519e−09 |

| 1.419e−01 | 1.861e+03 | 1.011e+00 | 5.237e+03 | 1.913e+01 | 5.364e+00 | 7.538e+02 | 1.708e−04 | 3.110e+04 | 7.938e−09 |

| 1.468e−01 | 1.948e+03 | 1.052e+00 | 5.039e+03 | 2.041e+01 | 4.454e+00 | 8.065e+02 | 1.425e−04 | 3.328e+04 | 6.619e−09 |

| 1.519e−01 | 2.039e+03 | 1.096e+00 | 4.830e+03 | 2.178e+01 | 3.696e+00 | 8.629e+02 | 1.189e−04 | 3.561e+04 | 5.520e−09 |

| 1.572e−01 | 2.134e+03 | 1.142e+00 | 4.612e+03 | 2.324e+01 | 3.065e+00 | 9.233e+02 | 9.921e−05 | 3.810e+04 | 4.603e−09 |

| 1.626e−01 | 2.232e+03 | 1.191e+00 | 4.385e+03 | 2.480e+01 | 2.541e+00 | 9.878e+02 | 8.277e−05 | 4.077e+04 | 3.838e−09 |

| 1.682e−01 | 2.334e+03 | 1.242e+00 | 4.153e+03 | 2.648e+01 | 2.105e+00 | 1.056e+03 | 6.905e−05 | 4.363e+04 | 3.201e−09 |

| 1.741e−01 | 2.440e+03 | 1.296e+00 | 3.917e+03 | 2.827e+01 | 1.744e+00 | 1.130e+03 | 5.761e−05 | 4.668e+04 | 2.669e−09 |

| 1.801e−01 | 2.550e+03 | 1.353e+00 | 3.681e+03 | 3.018e+01 | 1.444e+00 | 1.209e+03 | 4.806e−05 | 4.995e+04 | 2.226e−09 |

| 1.864e−01 | 2.663e+03 | 1.413e+00 | 3.447e+03 | 3.223e+01 | 1.196e+00 | 1.294e+03 | 4.010e−05 | 5.344e+04 | 1.856e−09 |

| 1.929e−01 | 2.780e+03 | 1.476e+00 | 3.216e+03 | 3.442e+01 | 9.902e−01 | 1.385e+03 | 3.345e−05 | 5.719e+04 | 1.547e−09 |

| 1.996e−01 | 2.901e+03 | 1.543e+00 | 2.989e+03 | 3.677e+01 | 8.195e−01 | 1.482e+03 | 2.791e−05 | 6.119e+04 | 1.290e−09 |

| 2.065e−01 | 3.025e+03 | 1.613e+00 | 2.769e+03 | 3.928e+01 | 6.781e−01 | 1.585e+03 | 2.328e−05 | 6.547e+04 | 1.076e−09 |

| 2.137e−01 | 3.152e+03 | 1.688e+00 | 2.556e+03 | 4.197e+01 | 5.610e−01 | 1.696e+03 | 1.942e−05 | 7.006e+04 | 8.974e−10 |

| 2.212e−01 | 3.283e+03 | 1.767e+00 | 2.351e+03 | 4.484e+01 | 4.641e−01 | 1.815e+03 | 1.620e−05 | 7.496e+04 | 7.482e−10 |

| 2.289e−01 | 3.416e+03 | 1.851e+00 | 2.154e+03 | 4.792e+01 | 3.839e−01 | 1.942e+03 | 1.351e−05 | 8.021e+04 | 6.239e−10 |

| 2.369e−01 | 3.553e+03 | 1.940e+00 | 1.966e+03 | 5.121e+01 | 3.175e−01 | 2.078e+03 | 1.127e−05 | 8.582e+04 | 5.202e−10 |

| 2.452e−01 | 3.691e+03 | 2.034e+00 | 1.789e+03 | 5.473e+01 | 2.625e−01 | 2.223e+03 | 9.406e−06 | 9.183e+04 | 4.337e−10 |

| 2.538e−01 | 3.832e+03 | 2.134e+00 | 1.621e+03 | 5.849e+01 | 2.171e−01 | 2.379e+03 | 7.846e−06 | 9.826e+04 | 3.609e−10 |

| 2.627e−01 | 3.975e+03 | 2.240e+00 | 1.463e+03 | 6.252e+01 | 1.795e−01 | 2.545e+03 | 6.545e−06 | 1.051e+05 | 2.844e−10 |

| 2.719e−01 | 4.120e+03 | 2.353e+00 | 1.316e+03 | 6.683e+01 | 1.484e−01 | 2.723e+03 | 5.460e−06 | … | … |

Note.

Differential Intensity units: (m2 s sr GV)−1.

Table 8.

Antiproton LIS

| Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

Rigidity GV |

Differential Intensitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.333e−02 | 1.214e−05 | 2.814e−01 | 9.882e−04 | 2.473e+00 | 3.158e−02 | 7.145e+01 | 2.277e−05 | 2.914e+03 | 2.664e−10 |

| 4.482e−02 | 1.571e−05 | 2.913e−01 | 1.066e−03 | 2.600e+00 | 3.169e−02 | 7.639e+01 | 1.867e−05 | 3.118e+03 | 2.148e−10 |

| 4.636e−02 | 1.750e−05 | 3.016e−01 | 1.149e−03 | 2.736e+00 | 3.161e−02 | 8.167e+01 | 1.529e−05 | 3.336e+03 | 1.732e−10 |

| 4.796e−02 | 1.894e−05 | 3.123e−01 | 1.239e−03 | 2.880e+00 | 3.133e−02 | 8.732e+01 | 1.253e−05 | 3.570e+03 | 1.394e−10 |

| 4.961e−02 | 2.037e−05 | 3.233e−01 | 1.335e−03 | 3.033e+00 | 3.086e−02 | 9.337e+01 | 1.025e−05 | 3.820e+03 | 1.122e−10 |

| 5.132e−02 | 2.189e−05 | 3.348e−01 | 1.439e−03 | 3.197e+00 | 3.019e−02 | 9.984e+01 | 8.395e−06 | 4.087e+03 | 9.020e−11 |

| 5.308e−02 | 2.351e−05 | 3.466e−01 | 1.549e−03 | 3.371e+00 | 2.935e−02 | 1.067e+02 | 6.868e−06 | 4.373e+03 | 7.242e−11 |

| 5.491e−02 | 2.526e−05 | 3.590e−01 | 1.667e−03 | 3.557e+00 | 2.833e−02 | 1.141e+02 | 5.616e−06 | 4.679e+03 | 5.808e−11 |

| 5.680e−02 | 2.715e−05 | 3.718e−01 | 1.794e−03 | 3.755e+00 | 2.717e−02 | 1.221e+02 | 4.591e−06 | 5.007e+03 | 4.652e−11 |

| 5.876e−02 | 2.918e−05 | 3.851e−01 | 1.929e−03 | 3.966e+00 | 2.589e−02 | 1.305e+02 | 3.752e−06 | 5.357e+03 | 3.720e−11 |

| 6.078e−02 | 3.136e−05 | 3.988e−01 | 2.073e−03 | 4.192e+00 | 2.450e−02 | 1.396e+02 | 3.065e−06 | 5.732e+03 | 2.970e−11 |

| 6.288e−02 | 3.372e−05 | 4.132e−01 | 2.227e−03 | 4.432e+00 | 2.302e−02 | 1.493e+02 | 2.503e−06 | 6.133e+03 | 2.367e−11 |

| 6.504e−02 | 3.627e−05 | 4.280e−01 | 2.392e−03 | 4.689e+00 | 2.150e−02 | 1.597e+02 | 2.044e−06 | 6.562e+03 | 1.883e−11 |

| 6.729e−02 | 3.902e−05 | 4.435e−01 | 2.568e−03 | 4.963e+00 | 1.994e−02 | 1.708e+02 | 1.668e−06 | 7.022e+03 | 1.495e−11 |

| 6.960e−02 | 4.199e−05 | 4.596e−01 | 2.755e−03 | 5.256e+00 | 1.838e−02 | 1.827e+02 | 1.361e−06 | 7.513e+03 | 1.184e−11 |

| 7.200e−02 | 4.519e−05 | 4.763e−01 | 2.955e−03 | 5.569e+00 | 1.683e−02 | 1.955e+02 | 1.110e−06 | 8.039e+03 | 9.354e−12 |

| 7.448e−02 | 4.865e−05 | 4.937e−01 | 3.169e−03 | 5.903e+00 | 1.531e−02 | 2.091e+02 | 9.053e−07 | 8.602e+03 | 7.368e−12 |

| 7.705e−02 | 5.239e−05 | 5.117e−01 | 3.397e−03 | 6.260e+00 | 1.384e−02 | 2.237e+02 | 7.380e−07 | 9.204e+03 | 5.785e−12 |

| 7.971e−02 | 5.643e−05 | 5.306e−01 | 3.640e−03 | 6.641e+00 | 1.245e−02 | 2.392e+02 | 6.015e−07 | 9.848e+03 | 4.527e−12 |

| 8.246e−02 | 6.080e−05 | 5.501e−01 | 3.900e−03 | 7.049e+00 | 1.112e−02 | 2.559e+02 | 4.900e−07 | 1.053e+04 | 3.529e−12 |

| 8.530e−02 | 6.552e− 05 | 5.705e−01 | 4.178e−03 | 7.484e+00 | 9.892e−03 | 2.738e+02 | 3.992e−07 | 1.127e+04 | 2.740e−12 |

| 8.824e−02 | 7.064e−05 | 5.918e−01 | 4.475e−03 | 7.950e+00 | 8.746e−03 | 2.929e+02 | 3.250e−07 | 1.206e+04 | 2.117e−12 |

| 9.128e−02 | 7.617e−05 | 6.139e−01 | 4.793e−03 | 8.448e+00 | 7.693e−03 | 3.133e+02 | 2.646e−07 | 1.290e+04 | 1.628e−12 |

| 9.443e−02 | 8.215e−05 | 6.370e−01 | 5.133e−03 | 8.981e+00 | 6.734e−03 | 3.352e+02 | 2.154e−07 | 1.381e+04 | 1.245e−12 |

| 9.769e−02 | 8.863e−05 | 6.611e−01 | 5.498e−03 | 9.550e+00 | 5.867e−03 | 3.586e+02 | 1.753e−07 | 1.477e+04 | 9.463e−13 |

| 1.010e−01 | 9.564e−05 | 6.863e−01 | 5.890e−03 | 1.015e+01 | 5.089e−03 | 3.836e+02 | 1.426e−07 | 1.581e+04 | 7.143e−13 |

| 1.045e−01 | 1.032e−04 | 7.126e−01 | 6.310e−03 | 1.081e+01 | 4.396e−03 | 4.104e+02 | 1.160e−07 | 1.692e+04 | 5.352e−13 |

| 1.081e−01 | 1.114e−04 | 7.400e−01 | 6.762e−03 | 1.150e+01 | 3.783e−03 | 4.391e+02 | 9.438e−08 | 1.810e+04 | 3.977e−13 |

| 1.118e−01 | 1.203e−04 | 7.687e−01 | 7.248e−03 | 1.225e+01 | 3.242e−03 | 4.698e+02 | 7.675e−08 | 1.937e+04 | 2.928e−13 |

| 1.157e−01 | 1.300e−04 | 7.987e−01 | 7.771e−03 | 1.304e+01 | 2.770e−03 | 5.026e+02 | 6.240e−08 | 2.072e+04 | 2.134e−13 |

| 1.197e−01 | 1.404e−04 | 8.301e−01 | 8.334e−03 | 1.390e+01 | 2.358e−03 | 5.377e+02 | 5.072e−08 | 2.218e+04 | 1.538e−13 |

| 1.238e−01 | 1.518e−04 | 8.629e−01 | 8.941e−03 | 1.481e+01 | 2.002e−03 | 5.753e+02 | 4.122e−08 | 2.373e+04 | 1.094e−13 |

| 1.281e−01 | 1.640e−04 | 8.974e−01 | 9.593e−03 | 1.578e+01 | 1.694e−03 | 6.155e+02 | 3.350e−08 | 2.539e+04 | 7.681e−14 |

| 1.326e−01 | 1.773e−04 | 9.335e−01 | 1.029e−02 | 1.682e+01 | 1.430e−03 | 6.585e+02 | 2.722e−08 | 2.717e+04 | 5.305e−14 |

| 1.372e−01 | 1.918e−04 | 9.713e−01 | 1.104e−02 | 1.794e+01 | 1.204e−03 | 7.046e+02 | 2.211e−08 | 2.907e+04 | 3.600e−14 |

| 1.419e−01 | 2.074e−04 | 1.011e+00 | 1.185e−02 | 1.913e+01 | 1.012e−03 | 7.538e+02 | 1.796e−08 | 3.110e+04 | 2.395e−14 |

| 1.468e−01 | 2.243e−04 | 1.052e+00 | 1.272e−02 | 2.041e+01 | 8.489e−04 | 8.065e+02 | 1.458e−08 | 3.328e+04 | 1.558e−14 |

| 1.519e−01 | 2.426e−04 | 1.096e+00 | 1.364e−02 | 2.178e+01 | 7.103e−04 | 8.629e+02 | 1.184e−08 | 3.561e+04 | 9.879e−15 |

| 1.572e−01 | 2.624e−04 | 1.142e+00 | 1.462e−02 | 2.324e+01 | 5.932e−04 | 9.233e+02 | 9.614e−09 | 3.810e+04 | 6.082e−15 |

| 1.626e−01 | 2.839e−04 | 1.191e+00 | 1.565e−02 | 2.480e+01 | 4.945e−04 | 9.878e+02 | 7.803e−09 | 4.077e+04 | 3.620e−15 |

| 1.682e−01 | 3.072e−04 | 1.242e+00 | 1.674e−02 | 2.648e+01 | 4.115e−04 | 1.056e+03 | 6.332e−09 | 4.363e+04 | 2.072e−15 |

| 1.741e−01 | 3.323e−04 | 1.296e+00 | 1.787e−02 | 2.827e+01 | 3.419e−04 | 1.130e+03 | 5.137e−09 | 4.668e+04 | 1.132e−15 |

| 1.801e−01 | 3.595e−04 | 1.353e+00 | 1.905e−02 | 3.018e+01 | 2.837e−04 | 1.209e+03 | 4.167e−09 | 4.995e+04 | 5.867e−16 |

| 1.864e−01 | 3.890e−04 | 1.413e+00 | 2.026e−02 | 3.223e+01 | 2.350e−04 | 1.294e+03 | 3.379e−09 | 5.344e+04 | 2.847e−16 |

| 1.929e−01 | 4.208e−04 | 1.476e+00 | 2.149e−02 | 3.442e+01 | 1.944e−04 | 1.385e+03 | 2.740e−09 | 5.719e+04 | 1.277e−16 |

| 1.996e−01 | 4.552e−04 | 1.543e+00 | 2.273e−02 | 3.677e+01 | 1.607e−04 | 1.482e+03 | 2.221e−09 | 6.119e+04 | 5.200e−17 |

| 2.065e−01 | 4.923e−04 | 1.613e+00 | 2.396e−02 | 3.928e+01 | 1.326e−04 | 1.585e+03 | 1.799e−09 | 6.547e+04 | 1.871e−17 |

| 2.137e−01 | 5.324e−04 | 1.688e+00 | 2.517e−02 | 4.197e+01 | 1.094e−04 | 1.696e+03 | 1.457e−09 | 7.006e+04 | 5.734e−18 |

| 2.212e−01 | 5.757e−04 | 1.767e+00 | 2.634e−02 | 4.484e+01 | 9.017e−05 | 1.815e+03 | 1.180e−09 | 7.496e+04 | 1.413e−18 |

| 2.289e−01 | 6.224e− 04 | 1.851e+00 | 2.744e−02 | 4.792e+01 | 7.423e−05 | 1.942e+03 | 9.558e−10 | 8.021e+04 | 2.553e−19 |

| 2.369e−01 | 6.727e−04 | 1.940e+00 | 2.846e−02 | 5.121e+01 | 6.106e−05 | 2.078e+03 | 7.734e−10 | 8.582e+04 | 2.846e−20 |

| 2.452e−01 | 7.269e−04 | 2.034e+00 | 2.937e−02 | 5.473e+01 | 5.019e−05 | 2.223e+03 | 6.256e−10 | 9.183e+04 | 1.351e−21 |

| 2.538e−01 | 7.852e−04 | 2.134e+00 | 3.016e−02 | 5.849e+01 | 4.123e−05 | 2.379e+03 | 5.057e−10 | 9.826e+04 | 1.102e−23 |

| 2.627e−01 | 8.481e−04 | 2.240e+00 | 3.080e−02 | 6.252e+01 | 3.385e−05 | 2.545e+03 | 4.087e−10 | 1.051e+05 | 4.036e−26 |

| 2.719e−01 | 9.156e−04 | 2.353e+00 | 3.128e−02 | 6.683e+01 | 2.777e−05 | 2.723e+03 | 3.300e−10 | … | … |

Note.

Differential intensity units: (m2 s sr GV)−1.

The MCMC procedure prefers a medium-size halo of 4 kpc, also favored by past studies (Strong & Moskalenko 2001), contrary to very large or extremely small halos proposed by lepton emission models (Strong et al. 2000; Gebauer & de Boer 2009) and by synchrotron emission studies (Orlando & Strong 2013). The electron LIS is the subject of the follow-up paper dedicated to leptons and nuclei Z > 2, although the final DCR model presented in this paper is already in a good agreement with AMS-02 electron data. It is worth pointing out that electrons may also have a component of the same origin as the excess positrons in CRs (Accardo et al. 2014; Aguilar et al. 2014). It may be less pronounced than in the case of positrons, due to the much larger flux of electrons from conventional sources, but still deserves a more careful study.

As pointed out in Jóhannesson et al. (2016), there could be a significant difference between the propagation parameters derived from the light isotopes (p, , He) and nuclei (boron to silicon). Our study does not show any evident discrepancies between the light isotopes (p, , He) and the B/C ratio (nuclei). This may be explained by the differences in the setups outlined in Section 2.1 and, in particular, by a more realistic description of heliospheric propagation used in the present analysis.

5. Proton, Helium, and Antiproton LIS

As described in the previous sections, our approach combines two state-of-the-art codes, GALPROP for interstellar propagation and HelMod for heliospheric propagation, within a single framework for the first time. AMS-02 data, which are guiding the refinement of the propagation scheme, are a vital ingredient of this approach. The converse is also true: the refined propagation scheme is beneficial for interpretation of the AMS-02 data. Combination of AMS-02 high-precision data (e.g., ~1% errors for the proton spectrum) with the data taken by earlier missions (AMS-01, BESS, PAMELA) at different epochs allows the framework to be extended to account for different polarities of the solar magnetic field and for periods of high and low solar activity in cycles 23 and 24 (see Section 5.3), while at the same time providing an accurate description of the Voyager 1 spectra taken beyond the TS.

5.1. Proton and Helium LIS outside the Modulated Energy Region

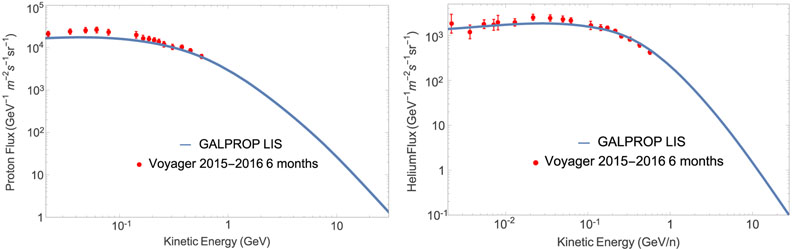

The direct measurements of proton and He LIS are now available at both low and high energies. High-energy CR fluxes above 100 GV are not affected by the heliospheric modulation, and their measurements provide a direct probe of the LIS. At low energies measurements of CR fluxes are provided by Voyager 1 that crossed the TS in the second half of 2012 (Stone et al. 2013; Cummings et al. 2016). To avoid a possible influence of turbulence that may still be present beyond the TS, we take the latest Voyager 1 2015–2016 data averaged over monthly intervals.16

The averages of 6 months of Voyager 1 data for protons and He are shown in Figure 4. The error associated with each data point is chosen conservatively to be equal to the variation of the monthly average, but not smaller than 15% of the flux value. The combined model provides a good description of proton and He LIS at low energies. The agreement with He is particularly good, while protons are slightly underestimated in the energy range between 30 and 100 MeV. Even though GALPROP has a good description of the relevant physics processes down to keV energies, we did not tune to the data below ~200 MeV/nucleon (available from ACE/CRIS). We also emphasize that Voyager 1 data were not included in the MCMC scan, and a remarkable agreement between the model predictions and the LIS data provides strong support for our approach. The low-energy LIS by Voyager 1 that are reproduced by GALPROP are linked to the modulated AMS-02 data using the HelMod code.

Figure 4.

DCR best-fit proton LIS (left) and He LIS (right), shown with blue curves, compared with Voyager 1 2015–2016 monthly averaged data.

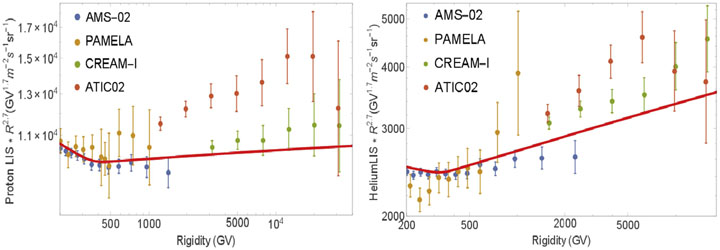

At high energies, where CR fluxes are not affected by the heliospheric modulation, we use AMS-02 data up to ~2 TV and extend the rigidity range to 20–30 TV using data taken by CREAM-I and ATIC-02 (Figure 5). In this energy range the data are scarce and there is an obvious systematic discrepancy between CREAM-I and ATIC-02. Extrapolations of proton and He spectra by AMS-02, even if not perfect, seem to prefer CREAM-I data, which we use hereafter. It is clear from the figures that using AMS-02 data alone would lead to steeper values for the injection indices γ3 at high energies. The relatively smaller error bars of CREAM-I versus AMS-02 data at high energies drive the fit to result in flatter index values. The derived γ3 values for protons and He (Table 2) reflect the results of the fit to combined AMS-02 and CREAM-I data.

Figure 5.

Best-fit proton LIS (left) and He LIS (right) compared with high-energy data by AMS-02, CREAM-I, ATIC-02, and PAMELA.

In addition to the plots and the tabulated data, we provide analytical functional dependence of the derived LIS (Figure 3) as a function of rigidity. To provide the required accuracy (1%–2% deviations), especially in the AMS-02 range, the fit was split into two rigidity intervals, roughly below and above 1 GV. The search of the analytic solutions—as already mentioned in Section 2.1—was guided by an advanced MCMC fitting procedure such as Eureqa.17 The combined LIS formula is

| (7) |

where ai, b, c, di, ei, fi, g are the numerical coefficients summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Parameters of the Analytical Fits to the Proton and He LIS

| LIS | a 0 | a 1 | a 2 | a 3 | a 4 | a 5 | b | c | d 1 | d 2 | e 1 | e 2 | f 1 | f 2 | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | 94.1 | −831 | 0 | 16700 | −10200 | 0 | 10800 | 8590 | −4230000 | 3190 | 274000 | 17.4 | −39400 | 0.464 | 0 |

| He | 1.14 | 0 | −118 | 578 | 0 | −87 | 3120 | −5530 | 3370 | 1.29 | 134000 | 88.5 | −1170000 | 861 | 0.03 |

The accuracy of the low-energy expression in Equation (7) is 2% in the range 0.2 GV < R < 1 GV for the proton LIS. The high-energy part reproduces the numerical proton LIS calculated with GALPROP with an accuracy of ~9% for 0.45 GV < R < 1 GV (i.e., Ekin > 0.11 GeV), where the constraints from Voyager 1 are wider than 10%, and of 2% for R > 1 GV. The discrepancies with respect to AMS-02 data at higher energies expressed in standard deviations are virtually zero, with 0.5σ around 1–2 GV at most. In the case of helium, the low-energy expression in Equation (7) is valid in the range of 0.15 GV < R < 2 GV, i.e., approximately between 3 and 450 MeV/nucleon. At higher rigidities 1.5 GV < R < 2 × 104 GV (i.e., >0.3 GeV/nucleon), it reproduces the He LIS calculated with GALPROP with an accuracy of 2%.

The derived expressions are virtually identical, to <1%–2%, to numerical solutions in an over 5 order of magnitude energy interval, including the spectral flattening at high energies, and are based on Voyager 1, AMS-02, and CREAM-I data.

5.2. Outside the Ecliptic Plane

A reliable model for heliospheric modulation requires a proper modeling of CR distribution in the whole heliospheric volume, including space outside the ecliptic plane and at large distances from the Sun.

Since the 1990s and until 2009, the Ulysses spacecraft (see, e.g., Sanderson et al. 1995; Balogh et al. 2001; Marsden 2001) explored the heliosphere outside the ecliptic plane up to ±80° in solar latitude and at distances ~1–5 au from the Sun. In particular, observations of particle flux were performed using the Cosmic Ray and Solar Particle Investigation Kiel Electron Telescope (COSPIN/KET) and High Energy Telescope (COSPIN/HET). Measurements of particle fluxes with the IMP-8 (before 2006) and PAMELA (after 2006) satellites as a baseline close to Earth allow the unique derivations of spatial gradients in the inner heliosphere outside the ecliptic plane.

Ulysses observations pointed to a positive latitudinal gradient in the proton intensity (see Figure 5 in Heber et al. 1996; Figure 2 in Simpson 1996). These observations of the proton flux taken during the latitudinal fast scan from 1994 September to 1995 August have shown (a) a nearly symmetric latitudinal gradient with the minimum near ecliptic plane, (b) a southward shift of the minimum, and (c) the intensity in the north polar region at 80° exceeding the south pole intensity. Simpson (1996) estimated a latitudinal gradient at ~0.3% per degree for protons with kinetic energy >0.1 GeV, while Heber et al. (1996) extended the analysis to higher energies estimating a gradient to be ~0.22% per degree for protons with kinetic energy >2 GeV. The minimum in the charged particle intensity separating the two heliospheric hemispheres occurs at ~10° south of the heliographic equator (Simpson 1996). An independent analysis that takes into account the latitudinal motion of Earth and IMP-8 confirms a significant (~8° ± 2°) southward offset of the intensity minimum for Ekin > 100 MeV protons (Simpson 1996), while Heber et al. (1996) estimated a southward offset of ≈7° independent of particle energy <2 GeV in their analysis. Finally, Simpson (1996) estimated that the intensity in the north polar region at 80° exceeds the south pole intensity by ~6% for protons of Ekin > 100 MeV. However, the same study of electrons (Ferrando et al. 1996) shows that the electron intensity does not show any sign of latitudinal dependence, at least up to 2.5 GV.

Almost 11 years later, a new latitudinal fast scan during the opposite magnetic field polarity was used to study the radial and latitudinal gradients of CR protons during the unusual solar minimum between solar cycles 23 and 24. The derived radial gradients of 2.8% ± 0.2% per au for 1.9 GV protons (De Simone et al. 2011; Gieseler & Heber 2016) were similar to those found in previous studies (McKibben 1975; Cummings et al. 1987; Heber et al. 1996). The measured latitudinal gradient was found to be slightly negative, −0.06% ± 0.01% per degree for 1.9 GV protons (see Table A.1 in Gieseler & Heber 2016).

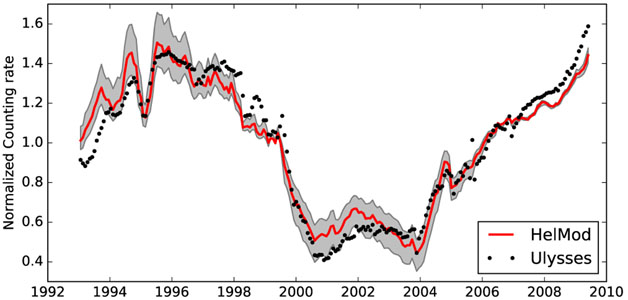

In Bobik et al. (2013a, 2013b) we have shown that a combination of a polar modification in the description of the HMF with a diffusion tensor that is independent of the solar latitude (see Section 3) is able to reproduce the measured latitudinal gradients during the low solar activity periods. In Figure 6 we compare the Ulysses counting rate normalized to the average value with the normalized proton flux at approximately the same rigidity. Data for Ulysses were taken from the Ulysses Final Archive.18 We analyzed the data for the KET coincidence channel K12 (proton energies of 0.25–2.2 GeV/nucleon) using the Carrington rotation average. HelMod results were provided for protons of 2.2 GeV for each Carrington rotation at the same distance and solar latitude as the Ulysses spacecraft. The error band was evaluated using the procedure described in Section 3.

Figure 6.

Ulysses counting rate normalized to the average value for the KET coincidence channel K12 (proton in energy range 0.25–2.2 GeV/nucleon) as a function of time in units of Carrington rotation. Each point was averaged over a Carrington rotation. The solid line is the HelMod result provided for protons at 2.2 GeV for each Carrington rotation at the same distance and solar latitude as the Ulysses spacecraft.

In Figure 6 one can see that the Ulysses data are qualitatively reproduced by the present model. Both experimental data and simulations are normalized to their corresponding mean values to allow a relative comparison along the solar cycle. The model reproduces the general features of latitudinal gradients observed during the fast scans of 1994–1995 and 2007. Moreover, the agreement is still acceptable along the whole orbit, which extends as far as ~3 au.

We note that the aim of Figure 6 is only to show the qualitative agreement found between the HelMod spectrum and observation data; in fact, HelMod calculations were performed for a monoenergetic bin, while KET observations are integrated over a large energy interval (see, e.g., the discussion in De Simone et al. 2011). A more quantitative comparison with Ulysses data needs to combine simulations for several energy bins and to weight them with the Ulysses response function.

The proposed model properly accounts for latitudinal and radial gradients in the inner heliosphere. The amplitude of model uncertainties is mainly related to the ratio between the perpendicular and parallel diffusion coefficient (ρi). A larger value of ρi leads to a more isotropic propagation and thus to a smaller latitudinal gradient. Therefore, Ulysses data allow the value of ρi to be reasonably constrained (Bobik et al. 2013a). During the period of negative solar magnetic field polarity, this effect vanishes for positively charged particles, due to the effective isotropization of particle trajectories by the global drift effects.

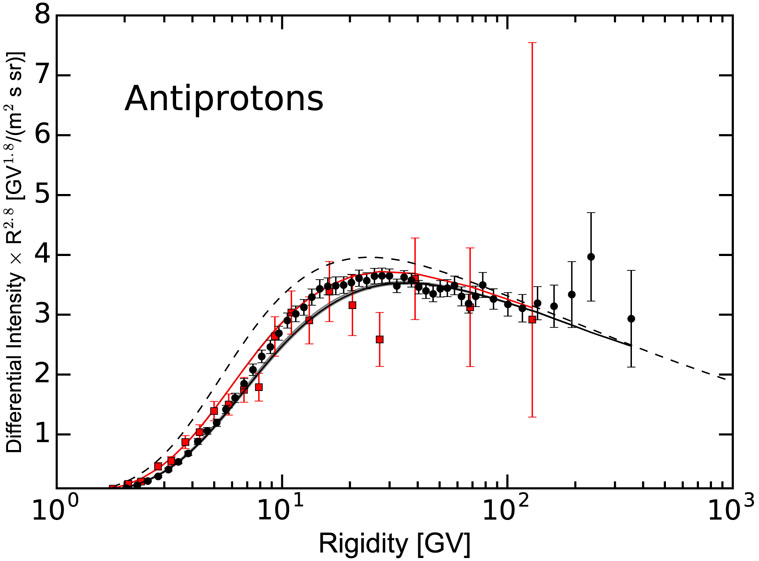

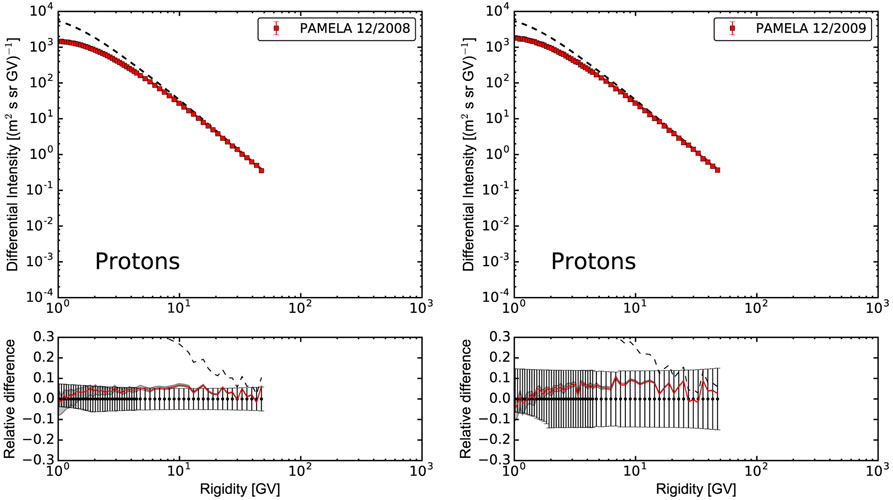

5.3. Data at Earth

This section discusses an application of the HelMod model to proton, helium, and antiproton spectra. A comparison is made with observational data for conditions of low (i.e., 1997–1998, 2006–2010) and high solar activity (i.e., 2000–2002, 2011–2013), and then with the moderate-activity period, thus providing a unique model that is valid for the entire solar cycle. In this section we show only illustrative results; more details can be found in the Appendix.

5.3.1. Low Solar Activity

During the solar minimum period, the HMF forms a regular structure, thus requiring the inclusion of the magnetic drift effects (see, e.g., Jokipii et al. 1977; Jokipii & Kopriva 1979; Potgieter & Moraal 1985; Boella et al. 2001; Strauss et al. 2011; Della Torre et al. 2012; Bobik et al. 2013a, 2013b). A low solar activity period between cycles 23 and 24 was recently studied by the PAMELA instrument (see, e.g., Adriani et al. 2013). Previous missions, such as the AMS-01 mission (1998 June, Aguilar et al. 2002) on the space shuttle and the BESS instrument (Shikaze et al. 2007; Abe et al. 2016), sampled a few short time periods during solar cycle 23. As discussed in the previous section, the solar minimum between cycles 23 and 24 was characterized by a negative HMF polarity (A < 0) that results in a more uniform latitudinal distribution in the inner part of the heliosphere for positively charged CR species. The AMS-01 mission was launched in 1998 June during the solar minimum with the positive HMF polarity (A > 0; Aguilar et al. 2002).

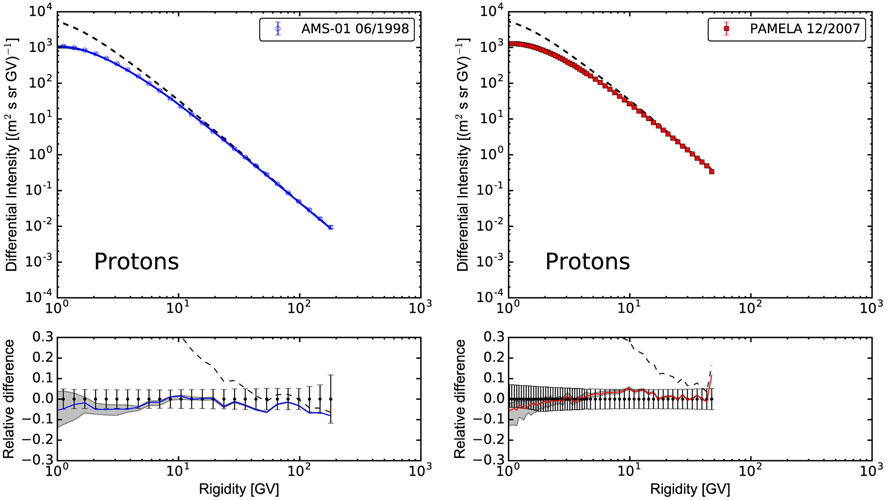

For both solar minima we found that glow = 0.3 in Equation (2) leads to an overall agreement between the simulations and data. In Figure 7 we show a comparison between experimental data and modulated spectrum calculated with HelMod for 1998 June (AMS-01) and 2007 December (PAMELA; also see the Appendix for an additional comparison). The HelMod description of particle propagation takes into account particle type and electrical charge. Note that in Equation (1) the drift term is the only one that is affected by the charge sign, while all other propagation terms are charge-symmetrical and can be expressed as a function of particle rigidity.

Figure 7.

Proton differential intensities for 1998 June (AMS-01; left) and 2007 December (PAMELA; right). Circles represent experimental data, the dashed line is the GALPROP LIS, and the solid line is the computed modulated spectrum. The bottom panel is the relative difference between the numerical solution and experimental data.

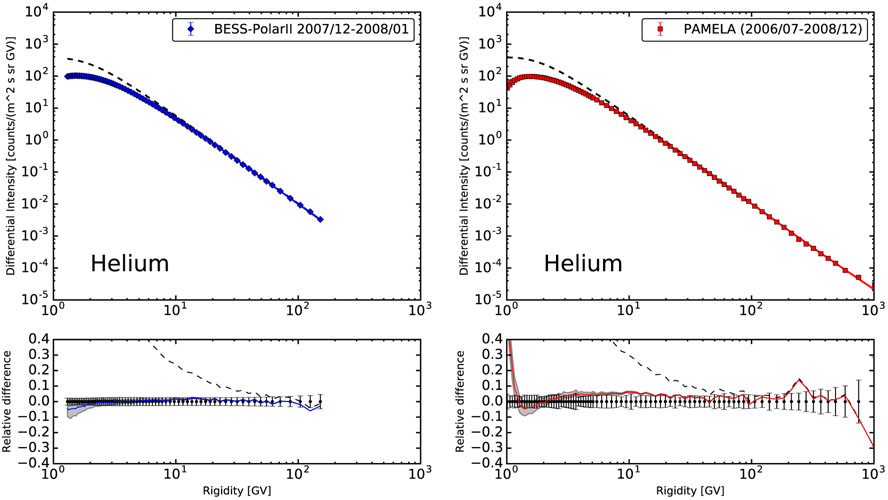

In Figure 8, the differential helium intensity from BESS-Polar II and PAMELA experiments is compared to the LIS modulated with HelMod (also see Appendix). The modulated differential intensity is found to be in good agreement with the experimental data at all rigidities above 1.5–2 GV, although a deviation relative to PAMELA data is observed at low rigidities.

Figure 8.

Helium differential intensity for 2007 December (BESS; left) and averaged for 2006–2009 (PAMELA; right). Circles represent experimental data, the dashed line is the GALPROP LIS, and the solid line is the computed modulated spectrum. The bottom panel is the relative difference between the numerical solution and experimental data.