SUMMARY

Cryptosporidiosis is one of the most important causes of moderate to severe diarrhea and diarrhea-related mortality in children under 2 years of age in low- and middle-income countries. In recent decades, genotyping and subtyping tools have been used in epidemiological studies of human cryptosporidiosis. Results of these studies suggest that higher genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. is present in humans in these countries at both species and subtype levels and that anthroponotic transmission plays a major role in human cryptosporidiosis. Cryptosporidium hominis is the most common Cryptosporidium species in humans in almost all the low- and middle-income countries examined, with five subtype families (namely, Ia, Ib, Id, Ie, and If) being commonly found in most regions. In addition, most Cryptosporidium parvum infections in these areas are caused by the anthroponotic IIc subtype family rather than the zoonotic IIa subtype family. There is geographic segregation in Cryptosporidium hominis subtypes, as revealed by multilocus subtyping. Concurrent and sequential infections with different Cryptosporidium species and subtypes are common, as immunity against reinfection and cross protection against different Cryptosporidium species are partial. Differences in clinical presentations have been observed among Cryptosporidium species and C. hominis subtypes. These observations suggest that WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene)-based interventions should be implemented to prevent and control human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries.

KEYWORDS: Cryptosporidium, molecular epidemiology, anthroponotic transmission, WASH, low- and middle-income countries

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidiosis is a major cause for diarrhea in young children in low- and middle-income countries. It has been recognized as one of the most important causes for moderate to severe diarrhea as well as diarrhea-related mortality in children less than 2 years in multiple recent studies (1–4). In South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, Cryptosporidium infections contribute annually to nearly 2.9 to 4.7 million diarrheal cases in children under 2 years (5, 6). It is estimated that cryptosporidiosis-associated diarrhea caused over 48,000 deaths as well as 4.2 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in children less than 5 years in 2016 (7). Globally, although the mortality related to diarrhea in children under 5 years had declined by 60% from 2000 to 2016, diarrhea-associated morbidity showed a lower reduction of only 13% (8). The prevalence of pathogens unresponsive to conventional antibiotic treatments, such as Cryptosporidium spp. and rotavirus, might be responsible for the slow reduction in global diarrhea-associated morbidity.

Cryptosporidiosis is also an important cause of childhood malnutrition. Even when cryptosporidiosis is not associated with diarrhea, it can still cause severe malnutrition (9, 10). Lower weight, weight-for-age Z scores, height-for-age Z scores, and/or body mass index-for-age Z scores are found in children infected with Cryptosporidium spp. than in uninfected children (7, 10–15). Children having multiple episodes of cryptosporidiosis experience more severe stunting (10, 16). Therefore, cryptosporidiosis is an important cause of growth retardation. It has been suggested that Cryptosporidium spp. impair intestinal-epithelial barrier integrity through the induction of inflammatory responses in the small intestine and affect nutrient absorption through the destruction of intestinal epithelial cells (17–20). On the other hand, stunting at birth is associated with the occurrence of cryptosporidiosis (19, 21, 22).

Molecular epidemiological tools have been used extensively in characterizing Cryptosporidium spp. at species/genotype and subtype levels (23). While more molecular epidemiological studies of cryptosporidiosis have been conducted in developed countries, increasing numbers of studies are from low- and middle-income countries, leading to improved understanding of the epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis (6, 10, 24–38). In particular, these studies have led to the identification of anthropogenic factors involved in the acquisition of Cryptosporidium spp. in children and HIV-positive patients.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL FEATURES OF CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Due to higher endemicity, lower hygiene levels, and less-intensive animal farming, the epidemiological features of human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries differ greatly from those in industrialized nations (Table 1). They include less-frequent occurrence of outbreaks, occurrence of infections at early age, more common association with HIV/AIDS, occurrence of multiple episodes of infections, and concurrence of other pathogens (39–41).

TABLE 1.

Differences in epidemiological features of human cryptosporidiosis between low- and middle-income countries and industrialized nations (23, 39, 103, 227)

| Feature | Characteristic in: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Industrialized nations | Low- and middle-income countries | |

| Endemicity | Low | High |

| Occurrence of outbreaks | High | Low |

| Susceptible population | All ages and immune statuses | Children and HIV-positive people |

| Infection in children | Late (>2 yrs) | Early (<2 yrs) |

| Major clinical symptoms | Diarrhea | Diarrhea and retarded growth |

| Asymptomatic infection | Low occurrence | High occurrence |

| Peak prevalence | Late summer and early autumn | Rainy season or cool months in the tropics |

| Major risk factors | International traveling, contact with animals or humans, swimming | Poor hygiene, overcrowding, diarrhea case in household |

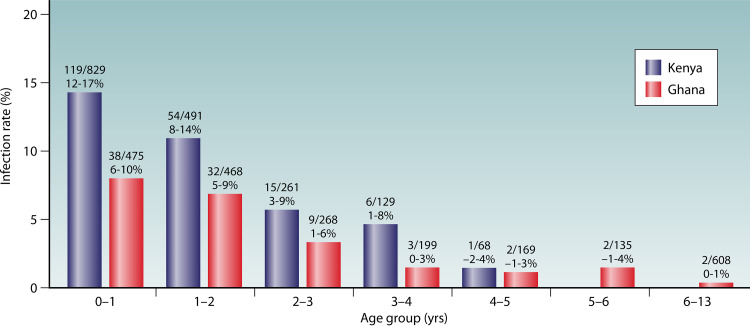

In low- and middle-income countries, cryptosporidiosis is mostly an infectious disease of young children. Pediatric cryptosporidiosis is mostly reported in children less than 2 years old (Fig. 1); recent birth cohort studies indicated as many as 77% of Bangladeshi children and 92.4% of Indian children experienced Cryptosporidium infection before the age of 2 years (9, 42). Data from the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) conducted in several low-income countries also indicated that Cryptosporidium spp. are among the most important diarrhea-related pathogens in children under 2 years (2, 30, 31, 43). In one GEMS in children with moderate to severe diarrhea under 5 years in rural western Kenya, 88.7% of cryptosporidiosis cases occurred in children under 2 years (30). Another GEMS in Gambian children with moderate to severe diarrhea under 5 years found that 91.8% of diarrhea cases caused by Cryptosporidium spp. occurred in young children of 6 to 24 months (31). Similar results have also been found in MAL-ED (Etiology, Risk Factors and Interactions of Enteric Infections and Malnutrition and the Consequences for Child Health and Development Project) studies (4, 13). In one MAL-ED study conducted in eight countries of Africa, Asia, and South America, nearly 65% of children under 2 years experienced Cryptosporidium infection and 54% had Cryptosporidium-associated diarrhea (13). In contrast, pediatric cryptosporidiosis in children from industrialized nations occurs later (age over 2 years) than in low- and middle-income countries (under 2 years), which is likely the result of delayed exposures to contamination under better hygiene (44).

FIG 1.

Age pattern of pediatric cryptosporidiosis in Kenya and Ghana (30, 128). Numbers above the bars denote the number of Cryptosporidium-positive cases/total number of children studied in each age group (the first line) and the 95% confidence intervals of the infection rates (the second line).

Cryptosporidiosis is also common in immunocompromised persons in low- and middle-income countries, especially HIV-positive patients (45–49). The prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected persons ranges from 5.6% to 25.7% in Africa, 3.7% to 45.0% in Asia, 5.6% to 41.6% in South America, and 2.6% to 15.1% in Europe (47). Higher infection rates and more severe clinical outcomes are seen in HIV-positive persons with CD4+ cell counts lower than 200 cells/μl (48). Many recent studies have reported the occurrence of cryptosporidiosis in hemodialysis patients as well as renal transplant patients in low- and middle-income countries (50–59). In contrast, human cryptosporidiosis occurs in persons of various ages and immune statuses in industrialized nations, probably as a reflection of reduced immunity. In industrialized nations, improved hygiene and better drinking source water and wastewater treatment have probably led to reduced exposure to Cryptosporidium oocysts, resulting in reduced immunity (60, 61).

Cryptosporidiosis in children is often associated with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, low-grade fever, headache, and fatigue (60, 62). The diarrhea can be watery and voluminous but usually resolves within 1 to 2 weeks without treatment. However, the median duration of postdiarrheal shedding was about 39.5 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 30.6 to 49 days) in one study (63). The occurrence of diarrhea or other symptoms, however, was detected in only approximately one-third of Cryptosporidium-infected children in community-based studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries (42). While multiple reasons, such as prior exposure to Cryptosporidium infection and receiving colostrum, might be involved, results of a recent study in Bangladesh suggest that host genetics could play a potential role. A genetic variant within protein kinase C alpha (PRKCA) was associated with a higher risk of symptomatic cryptosporidiosis during the first year of life (64). Even subclinical cryptosporidiosis has significant adverse effects on children, as they may experience retarded growth (7, 10, 15, 65). Unlike in low- and middle-income countries, both children and adults with cryptosporidiosis in developed countries often have diarrhea (39, 60).

Cryptosporidium infections in low- and middle-income countries result mainly from poor hygiene and sanitation (66). Cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies have identified multiple risk factors in human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries (Table 2). Among them, poor hygiene is the most common risk factor, followed by contact with animals, overcrowding, poor drinking water, young age, and household diarrhea. However, different studies have identified different risk factors. For example, a recent molecular epidemiological study of cryptosporidiosis in four sub-Saharan African nations has identified contact with Cryptosporidium-positive household members (risk ratio [RR] = 3.6; 95% CI, 1.7 to 7.5) or neighboring children (RR = 2.9; 95% CI, 1.6 to 5.1) rather than having positive animals (RR = 1.2; 95% CI, 0.8 to 1.9) as the risk factors (33). Contact with animals, especially calves, was a common risk factor for human cryptosporidiosis in many but not all studies (33, 66–69). It is interesting to find that animal contact was protective for Cryptosporidium infection in children in Mozambique (70). One study in Cameroon found that breastfeeding (odds ratio [OR] = 0.18; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.90) was protective for Cryptosporidium infection in children within 6 months (71). In an investigation of a cryptosporidiosis outbreak in Botswana, hospitalization and mortality in children were associated primarily with nonbreastfeeding (72). However, prolonged breast feeding (>2 years) (OR = 2.18; 95% CI, 1.02 to 7.32) was a risk factor for pediatric cryptosporidiosis in Malaysia (73). In Zambia, male gender (OR = 2.5; 95% CI, 1.13 to 5.70), divorce (OR = 14.8; 95% CI, 1.58 to 138.4), and sharing water sources among neighbors (OR = 5.7; 95% CI, 1.15 to 27.9) were major risk factors for Cryptosporidium infection in HIV-positive persons (38). Although divergent risk factors for human cryptosporidiosis have been identified in different studies, poor hygiene was the major one in low- and middle-income countries, while swimming, contact with diarrheal persons/animals, and international travelling were the major ones in industrialized nations (39, 66, 74, 75).

TABLE 2.

Recent studies on the risk factors for human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries

| Location | Type of study | Sample size | Study population | Major risk factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | |||||

| China | Case-control | 1,366 | Patients with and without HIV | Contact with animals | 115 |

| Cross-sectional | 1,635 | Children and adults | Overcrowding, contact with animals, infection with hepatitis B virus | 228 | |

| Cross-sectional | 321 | Children | Poor hygiene, poor drinking water | 229 | |

| Cross-sectional | 1,637 | Children with and without diarrhea | Poor hygiene | 230 | |

| Indonesia | Case-control | 4,368 | Patients with and without diarrhea | Contact with animals, overcrowding, rainfall | 231 |

| Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 276 | Children | Low birth wt, overcrowding, breastfeeding | 73 |

| Cross-sectional | 135 | Children | Old age, poor hygiene | 232 | |

| Philippines | Cross-sectional | 137 | Children and adults | Location, poor drinking water, open defecation | 233 |

| Cambodia | Cross-sectional | 498 | Children | Malnutrition, chronic medical diagnoses, contact with animals | 130 |

| Bangladesh | Case-control | 272 | Children with and without diarrhea | Young age, nonbreastfeeding, stunting | 234 |

| Cohort | 392 | Children | Malnutrition | 9 | |

| Cohort | 203 | Children | Overcrowding | 13 | |

| India | Case-control | 580 | Children with and without diarrhea | Overcrowding, stunting | 235 |

| Pakistan | Cross-sectional | 425 | Children with diarrhea | Poor hygiene, diarrhea, environmental factors | 95 |

| Iran | Cross-sectional | 171 | Children with and without diarrhea | Low birth wt, less breastfeeding, male gender | 236 |

| Case-control | 480 | Healthy persons and hemodialysis patients | Poor hygiene, diarrhea, education level, young age | 51 | |

| Lebanon | Cross-sectional | 249 | Children | Young age, digestive symptoms, diarrhea, fever | 237 |

| Cross-sectional | 412 | Patients and children | Having meals outside home, diarrhea | 238 | |

| Africa | |||||

| Ethiopia | Cross-sectional | 520 | HIV/AIDS patients | Contact with animals | 67 |

| Cross-sectional | 393 | Children with and without diarrhea | Young age | 157 | |

| Libya | Case-control | 505 | Children with and without diarrhea | Contact with animals, foreign workers from Africa, poor hygiene, poor drinking water | 239 |

| Egypt | Case-control | 100 | Children with and without diarrhea | Poor hygiene, contact with animals, diarrhea | 139 |

| Kenya | Case-control | 1,778 | Children with and without diarrhea | Young age | 30 |

| Uganda | Cross-sectional | 108 | Children and adults | Poor drinking water | 240 |

| Malawi | Case-control | 96 | Children with and without diarrhea | Contact with animals, poor hygiene, diarrhea | 241 |

| Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 692 | Children with and without diarrhea | Young age, stunting | 242 |

| Cross-sectional | 180 | Children | Young age, diarrhea | 243 | |

| South Africa | Case-control | 180 | Adults with or without HIV or diarrhea | Poor hygiene, contact with animals, poor socioeconomic state | 140 |

| Mozambique | Cross-sectional | 985 | Children with diarrhea | Nampula Province, underweight | 70 |

| Zambia | Cross-sectional | 222 | Children with diarrhea | Rainfall, breastfeeding | 244 |

| Cross-sectional | 326 | HIV/AIDS patients | Sex, marital status, sharing water sources among neighbors | 38 | |

| Angola | Cross-sectional | 351 | Children | Young age | 150 |

| Gambia | Case-control | 4,907 | Children with and without diarrhea | Poor drinking water, contact with animals, overcrowding | 31 |

| Ghana | Cross-sectional | 50 | Children and adults with HIV | Poor drinking water | 245 |

| Guinea-Bissau | Case-control | 250 | Children with and without diarrhea | Contact with animals, poor hygiene, male gender | 246 |

| Cameroon | Cross-sectional | 112 | Children | Nonbreastfeeding, poor drinking water | 71 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Cross-sectional | 1363 | Children | Contact with humans | 33 |

| Americas | |||||

| Cuba | Case-control | 215 | Children with and without diarrhea | Poor hygiene, contact with animals | 247 |

| Guatemala | Cohort | 130 | Children with and without diarrhea | Lack of toilet, contact with animals | 248 |

| Cross-sectional | 100 | Children with gastroenteritis | Poor hygiene, female gender | 249 | |

| Mexico | Cross-sectional | 403 | Children with diarrhea | Malnutrition, nonbreastfeeding | 250 |

| Cross-sectional | 173 | Children without diarrhea | Poor drinking water, contact with animals | 11 | |

| Cross-sectional | 132 | Children without diarrhea | Poor drinking water, overcrowding, poor hygiene, diarrhea | 251 | |

| Venezuela | Cross-sectional | 515 | Children and adults | Poor hygiene, overcrowding, young age | 252 |

| Brazil | Cohort | 189 | Children with and without diarrhea | Low birth wt, overcrowding | 253 |

| Cross-sectional | 445 | Children with diarrhea | Young age, poor hygiene, diarrhea, rainfall, male gender | 254 | |

| Peru | Cohort | 368 | Children with and without diarrhea | Lack of toilet, warm season | 255 |

Although cryptosporidiosis is highly endemic in low- and middle-income countries, it rarely causes outbreaks there, probably due to the high level of population immunity (66). A few outbreaks of human cryptosporidiosis, however, have been reported in Mexico, Brazil, Botswana, Jordan, and China, imposing additional burdens on the stretched public health system (72, 76–78). In contrast, human cryptosporidiosis in industrialized nations is best known for foodborne, waterborne, and animal contact-associated outbreaks (79, 80).

UNIQUE DISTRIBUTION OF CRYPTOSPORIDIUM SPECIES IN HUMANS IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Although humans and other vertebrates are common hosts of Cryptosporidium spp., most species have host specificity (81). Currently, over 40 Cryptosporidium species have been recognized in mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish (82). There are also many Cryptosporidium genotypes of unknown species status. Due to the existence of host specificity, only one to four Cryptosporidium species/genotypes are frequently found in one host species. For example, dogs are mostly infected with C. canis, cats with C. felis, rabbits with C. cuniculus, humans with C. hominis and C. parvum, sheep and goats with C. parvum, C. ubiquitum, and C. xiaoi, and cattle with C. parvum, C. bovis, C. ryanae, and C. andersoni (82). Among the known Cryptosporidium species, C. parvum is one of the few species with a wide host range and also the most important zoonotic species in humans (82).

Over 20 Cryptosporidium species and genotypes have been reported in humans, many with fewer than a handful of cases (81). Among them, C. parvum and C. hominis are two major species, being responsible for over 90% of human cryptosporidiosis cases in most areas. Other less commonly detected species include C. meleagridis, C. canis, C. felis, C. ubiquitum, C. cuniculus, C. viatorum, Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I, and C. muris in the order of numbers of reported cases. The remaining ones have each been occasionally detected in several cases (82).

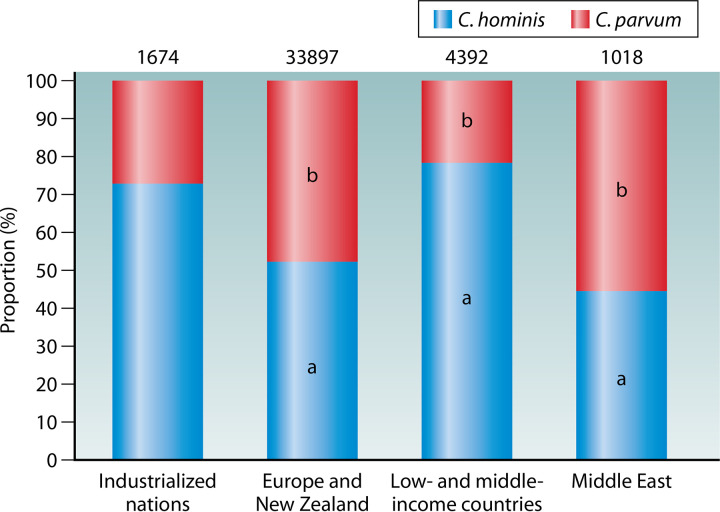

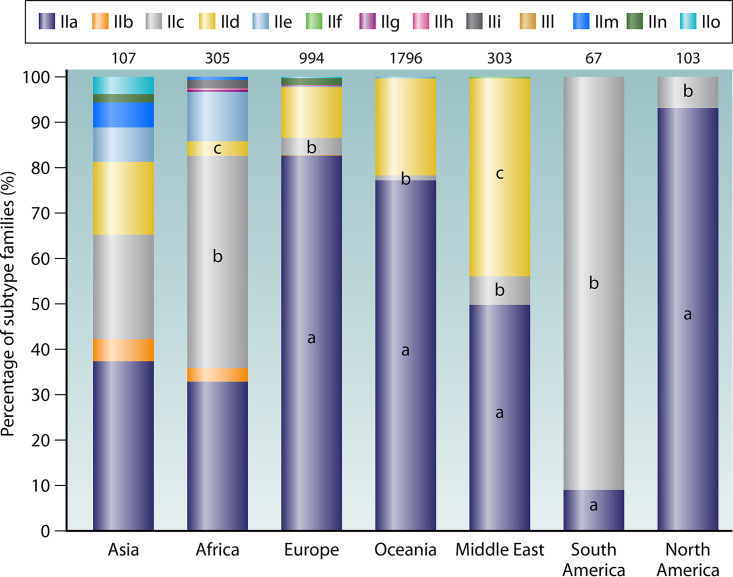

The distribution of Cryptosporidium species in humans is different between industrialized and low- and middle-income countries (Fig. 2). Molecular epidemiological studies of human cryptosporidiosis have recognized C. hominis as the dominant species in both children and HIV-positive patients in low- and middle-income countries (39). In contrast, C. hominis and C. parvum infections appear to be equally common in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent persons in European and Middle East countries as well as New Zealand (39, 75, 80, 83, 84). In some industrialized nations, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan, although most human cryptosporidiosis cases are caused by C. hominis, there is a high occurrence of C. parvum in rural areas (85–88). These results suggest that zoonotic infection is less common in low- and middle-income countries than in industrialized nations.

FIG 2.

Proportion (%) of Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis in different areas and socioeconomic conditions. Numbers above bars denote sample size (n). In the bars, “a” indicates a significant difference in proportion of C. hominis between industrialized nations and the group under comparison (P < 0.05 by chi-square test), while “b” indicates a significant difference in proportion of C. parvum between industrialized nations and the group under comparison (P < 0.05).

The distribution of other human-pathogenic Cryptosporidium species is also different between low- and middle-income countries and industrialized nations. Most human infections with C. meleagridis, C. felis, C. canis, C. viatorum, and C. muris have been reported in studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries or in persons who have traveled to these areas (10, 39, 67, 89, 90). In contrast, most human infections with C. ubiquitum, C. cuniculus, and chipmunk genotype I are from industrialized nations. In particular, C. ubiquitum and chipmunk genotype I contribute to substantial numbers of human Cryptosporidium infections in rural states in the United States, while C. cuniculus infections are reported mainly in the United Kingdom and New Zealand (83, 86, 91–94).

CHARACTERISTICS OF C. HOMINIS INFECTION IN HUMANS IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Molecular epidemiological studies of Cryptosporidium infections in children have shown a dominance of C. hominis in low- and middle-income countries, accounting for an average of over 65% of Cryptosporidium cases. In some studies, the lack of C. hominis was possibly caused by the use of genotyping tools targeting individual species (95) or a small number of Cryptosporidium-positive specimens (96, 97). The dominance of C. hominis could be due to the importance of environmental contamination and direct person-to-person transmission in cryptosporidiosis epidemiology. This was supported by the observation of a high rate of secondary infection and infection with the same subtype within families in a case-control study of Cryptosporidium transmission in Bangladeshi households (25). Cryptosporidium hominis is also a major species in HIV-positive patients in low- and middle-income countries. There is frequently a good agreement in the distribution of Cryptosporidium species between children and HIV-positive patients in the same country.

In low- and middle-income countries, the results of molecular characterizations of C. hominis isolates have highlighted the complexity of cryptosporidiosis epidemiology. Molecular analyses of C. hominis have revealed much higher numbers of subtype families in humans in low- and middle-income countries than in industrialized nations (98). Based on sequence analysis of the 60-kDa glycoprotein (gp60) gene, C. hominis is divided into five major subtype families with very divergent sequences, including Ia, Ib, Id, Ie, and If. Each C. hominis subtype family has many subtypes that differ from each other mostly in the number of trinucleotide repeats at the 5′ end of the gene sequence. All five subtype families are common in children and HIV-positive persons in most low- and middle-income countries examined. The complexity of transmission is further supported by the occurrence of multiple subtypes within the Ia, Ib, and Id subtype families in most areas of endemicity (25, 26, 29, 33, 62, 99–102). In comparison, much lower genetic diversity of C. hominis is seen in humans in industrialized nations. In European countries, subtype family Ib contributes to over 90% of C. hominis infections (80). The high heterogeneity of C. hominis in low- and middle-income countries is considered an indication of the high intensity of cryptosporidiosis transmission in areas of endemicity (103).

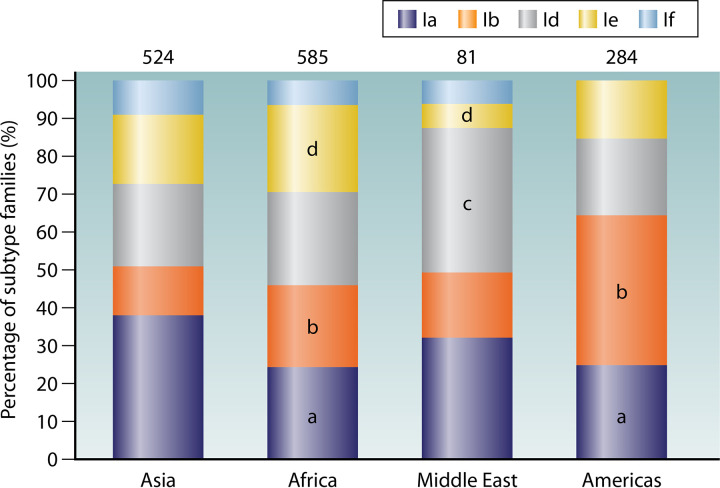

The distribution of common C. hominis subtype families varies among geographic areas (Fig. 3). In Asia, Ia is a major subtype family for C. hominis in humans, followed by Id, Ie, Ib, and If, in that order (25, 29); in Africa, the frequencies of Ia, Ib, Id, and Ie are about the same and significantly higher than that of If (33, 102, 104); in the Middle East, Id is most common, followed by Ia and Ib, with only limited occurrence of Ie and If (99, 100); in the Americas, Ib is the most common subtype family of C. hominis, followed by Ia, Id, and Ie, with the absence of If (24, 105). These differences in distribution of C. hominis subtype families possibly reflect variations in the transmission of C. hominis in humans among areas.

FIG 3.

Distribution of common Cryptosporidium hominis subtype families among low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. Numbers above bars denote sample size (n). In the bars, “a,” “b,” “c,” and “d” indicate a significant difference in distribution of Ia, Ib, Id, and Ie between Asia and the group under comparison (P < 0.05 by chi-square test), respectively.

Geographical segregation is seen in the distribution of subtypes within some of the common subtype families. For instance, two major subtypes are seen within the subtype family Ib: IbA9G3 and IbA10G2. The former is common in Jordan, Tanzania, Uganda, Kenya, Bangladesh, and India, while the latter is common in Peru, Jamaica, Colombia, Argentina, and Brazil as well as South Africa. Other subtypes, such as IbA13G3, IbA10G1, IbA11G2, and IbA12G3, were reported only in limited regions. This geographic segregation in C. hominis subtypes has been confirmed by multilocus sequence type (MLST) analysis of specimens from several countries (106).

CHARACTERISTICS OF C. PARVUM INFECTION IN HUMANS IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

Cryptosporidium parvum contributes to ∼20% of cases of human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries. As with C. hominis, there are multiple subtype families within C. parvum at the gp60 locus. Some of the C. parvum subtype families are host adapted, which is useful in tracking the sources of C. parvum infections in humans. For example, the IIa subtype family is commonly found in dairy calves, the IId subtype family is found mostly in lambs and goat kids, while the IIc subtype family is almost exclusively a human pathogen (82). Although there are more subtype families in C. parvum than in C. hominis, only 1 or 2 subtype families are responsible for most human C. parvum infections in one particular area.

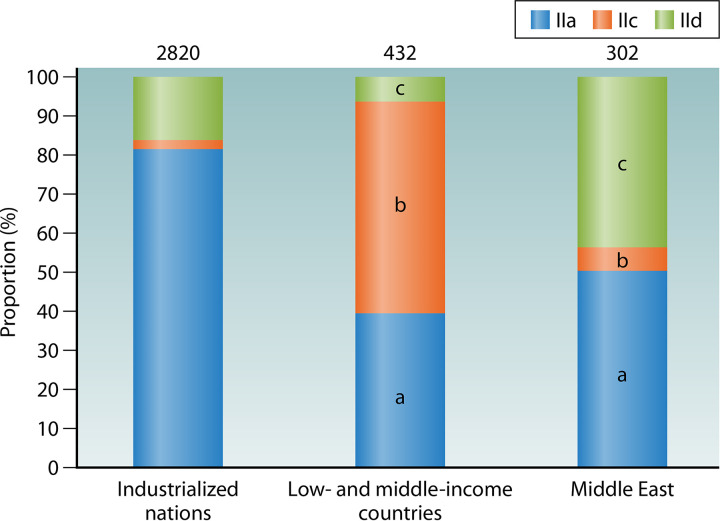

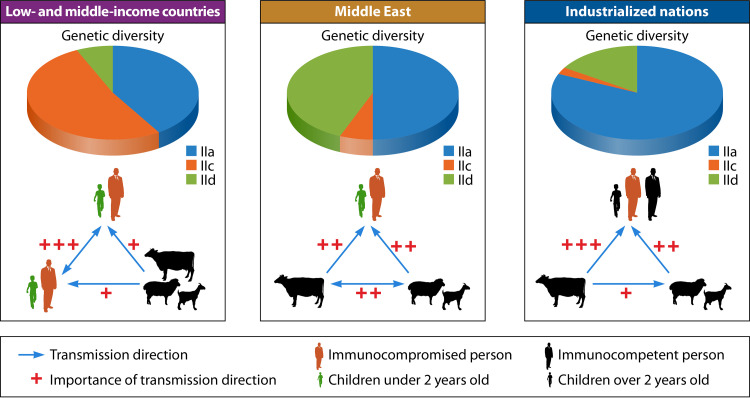

The distribution of common C. parvum subtype families varies greatly among different geographic regions and socioeconomic conditions (Fig. 4). In low- and middle-income countries, IIc contributes to over half the disease burden due to C. parvum, followed by IIa, while the contribution of IId is limited. The IIa subtypes identified in humans in low- and middle-income countries, however, were mostly from the few studies conducted in Malaysia and Ethiopia (67, 107, 108), except for a recent one in China (28), where IIa subtypes are rare in animals (109–113). In Middle East countries, some of which are highly industrialized, the disease burdens of IId and IIa are significantly higher than that of IIc. In contrast, IIa is responsible for over 80% of C. parvum infections in industrialized countries, whereas IId subtypes are seen mostly in New Zealand and Europe, and IIc infections are associated with travel to low- and middle-income countries (75, 80, 83, 98). The difference in distribution of C. parvum subtype families among geographic regions and socioeconomic conditions is probably a reflection of differences in infection sources and transmission routes.

FIG 4.

Proportion (%) of common Cryptosporidium parvum subtype families in different areas and socioeconomic conditions. Numbers above bars denote sample size (n). In the bars, “a,” “b,” and “c” indicate a significant difference in proportion of IIa, IIc, and IId between industrialized nations and the group under comparison (P < 0.05 by chi-square test), respectively.

The subtype diversity of C. parvum in humans is much higher in low- and middle-income countries than in industrialized nations (Table 3; Fig. 5). As presented in Table 3, analysis of the subtype diversity using the Simpson and Shannon-Wiener indexes showed the highest subtype diversity of C. parvum in Asia, followed by Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Oceania, South America, and North America. In Africa, as many as nine subtype families are recognized, including IIa to IIe, IIg, IIh, IIi, and IIm. Among them, IIc is the most common subtype family. This is followed by the IIe subtype family, which appears to be another anthroponotic subtype family of C. parvum. The occurrence of the remaining subtype families is sporadic. The IIa subtype family, however, appears to be common in AIDS patients in Ethiopia, together with some occurrence of the IId subtype family (67).

TABLE 3.

Subtype diversity of Cryptosporidium parvum in humans in divergent geographic regions

| Location | No. of cases of indicated subtype of C. parvuma |

Simpson index | Shannon-Wiener index | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIa | IIb | IIc | IId | IIe | IIf | IIg | IIh | IIi | IIl | IIm | IIn | IIo | |||

| Asia | 40 | 5 | 25 | 17 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 0.7678 | 1.6957 |

| Africa | 93 | 8 | 132 | 9 | 31 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.6578 | 1.3215 |

| Europe | 822 | 1 | 38 | 111 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 0.3019 | 0.6390 |

| Oceania | 1,387 | 0 | 20 | 384 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.3578 | 0.5973 |

| Middle East | 151 | 0 | 19 | 132 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5579 | 0.9016 |

| South America | 6 | 0 | 61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1631 | 0.3015 |

| North America | 96 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1267 | 0.2483 |

Numbers represent cases of each subtype family in corresponding regions.

FIG 5.

Distribution of Cryptosporidium parvum subtype families in humans in Asia, Africa, Europe, Oceania, the Middle East, South America, and North America. Numbers above bars denote sample size (n). In the bars, “a,” “b,” and “c” indicate a significant difference in distribution of IIa, IIc, and IId between Asia and the group under comparison (P < 0.05 by chi-square test), respectively.

In Asia, up to eight subtype families have been reported, namely, IIa to IIe, IIm, IIn, and IIo. Among them, the IIa and IIc subtype families are the most common. They are followed by the IId and IIe subtype families. The common occurrence of the IIa subtype family, however, is mostly attributable to two reports in Malaysia and China (28, 108). The Chinese report was contradictory to other reports, which mostly reported the IId subtype family in the country (27, 114, 115). In fact, IIa subtypes are absent from dairy calves in China, which are exclusively infected with IId subtypes (109). Other C. parvum subtype families such as IIe, IIm, and IIo have been only occasionally reported in humans in Asia (6, 26, 32, 116, 117).

In the Middle East, the genetic diversity of C. parvum in humans is much lower. Although four subtype families are recognized, two of them have very low frequency. Among them, IId contributes to over half of the C. parvum infections. The importance of IId in human infections in Middle East countries may be related to the importance of small ruminants, which are commonly infected with C. parvum IId subtypes (118). This is followed by IIa, which accounts for almost all the remaining C. parvum infections there. In contrast, IIc and IIf subtype families were reported in only a few cases in the area (99, 100, 119–121).

In South America, only IIc and IIa have been reported in humans. Although IIc is more common than IIa there, there is an increasing occurrence of IIa in humans in recent years, especially in Colombia and Mexico, which geographically is located in North America (24, 122). The occurrence of IIa subtypes there reflects their common occurrence in dairy calves (123). The IIc subtype family, however, remains the dominant C. parvum in humans in urban areas in South America (105, 122, 124, 125).

The dominance of the IIc subtype family in humans in low- and middle-income countries suggests that anthroponotic transmission plays a major role in cryptosporidiosis in this area (Fig. 6). This is especially the case in African and Asian countries and urban areas in South America, where the anthroponotic IIc subtype family is especially common in low-income countries with poor sanitation and in HIV-positive persons (126). In many Asian and African countries, the occurrence of IIc subtypes in humans is in concurrence with IIe, another anthroponotic C. parvum subtype family (26, 32, 33, 67, 104, 127–130). In addition to them, several other subtype families were also found (127, 128, 131). In contrast, the common occurrence of IIa and IId subtypes in Middle East countries suggests that zoonotic transmission of C. parvum might play a significant role in cryptosporidiosis there. This is in agreement with the common occurrence of IIa and IId subtypes in calves, lambs, and goat kids in these countries (132–138). Indeed, animal contact has been identified as a risk factor for pediatric cryptosporidiosis in Egypt (139). Zoonotic transmission appears to be important in some countries elsewhere, such as Ethiopia in Africa and Malaysia in Asia, where in addition to IIa and IId, anthroponotic transmission of IIc occurs simultaneously (67, 108). In the Ethiopian study, calf contact was identified as a risk factor for infection with the IIa subtype family (67). This is one of the rare occasions in low- and middle-income countries where zoonotic transmission of C. parvum has been explicitly implicated in playing a significant role in cryptosporidiosis epidemiology. These findings indicate that although anthroponotic transmission contributes to the majority of C. parvum infections in humans in low- and middle-income countries, zoonotic transmission is increasingly recognized in some countries where the disease is endemic. This is probably related to the increased direct or indirect contact with farm animals as part of the property relief efforts that have been under way for some years (68, 140, 141).

FIG 6.

Differences in transmission of major subtype families of Cryptosporidium parvum in humans between low- and middle-income countries and industrialized nations. The blue arrows indicate major directions of transmission, and the red plus symbols indicate their importance in cryptosporidiosis epidemiology. The relative distribution of the major subtype families is indicated in the pie chart.

In the desert country Botswana, one major outbreak of diarrhea in 2006 after heavy rains and floods had led to hundreds of deaths and thousands of infections in children less than 5 years old. It was mainly caused by cryptosporidiosis. Based on the results of molecular epidemiological investigations, C. parvum and C. hominis were found in 30 cases examined, with almost equal distribution (72). A total of five subtype families of C. hominis were found. In contrast, only two IIc subtypes (IIcA5G3a and IIcA5G3b) were found among the C. parvum-positive samples (L. Xiao, unpublished data). These data indicate that the source of contamination during the outbreak was probably of human origin. Poor sewage treatment or lack of sewage treatment might have contributed to the occurrence of the outbreak (72).

CHARACTERISTICS OF OTHER CRYPTOSPORIDIUM SPECIES IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

In addition to C. hominis and C. parvum, other species, including C. meleagridis, C. canis, C. felis, C. viatorum, and C. muris, are significant causes of human cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries (10, 24, 26, 32, 67, 103). In industrialized nations, infections with these species are frequently associated with foreign travel, as autochthonous infections with them are rare (83, 89, 142, 143). Several other species associated with zoonotic cryptosporidiosis in industrialized nations, such as C. ubiquitum, C. cuniculus, and Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I, are rarely detected in humans in low- and middle-income countries.

Cryptosporidium meleagridis is traditionally considered an avian species but has been found in children and HIV-positive patients in many low- and middle-income countries. In some recent studies conducted in Nigeria, Mozambique, Tunisia, Madagascar, Ghana, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Colombia, C. meleagridis was a prevalent species and contributed to 9% to 92% of the 22 to 94 cryptosporidiosis cases examined in each study (10, 25, 26, 33, 99, 129, 144). In one recent study of molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis in two areas in Bangladesh, over 100 C. meleagridis infections were identified. Cryptosporidium meleagridis was found in 13% of Cryptosporidium infections in the urban area and 90% of Cryptosporidium infections in the rural area (10). Cryptosporidium meleagridis was also found at a high frequency (20 of 92 Cryptosporidium-positive cases) in HIV-positive patients in one study in Bangkok, Thailand (26). In one small-scale study in China, only C. meleagridis was found in children with diarrhea (96).

A gp60-based subtyping tool is available for the genetic characterization of C. meleagridis (145). Eight subtype families (IIIa to IIIh) and over 30 subtypes have been reported in humans (23, 145). In one study of C. meleagridis infections in HIV-positive patients in Bangkok, Thailand, nine subtypes were identified (26). Some human infections with C. meleagridis are possibly caused by zoonotic transmission, judged by the occurrence of IIIbA26G1R1b and IIIbA22G1R1c in both diarrheic children and farmed chickens in Hubei, China (96, 146). The results of one MLST analysis of C. meleagridis from children, AIDS patients, and birds in Peru did not find obvious host segregation in subtypes, suggesting that zoonotic transmission of C. meleagridis between humans and birds is possible (147). Seven of the 55 human C. meleagridis cases in the study, however, had coinfection with C. hominis, indicating that at least some of the C. meleagridis infections in humans were of anthroponotic origin.

The MLST characterization of C. meleagridis identified two major groups (group 1 and group 2) of C. meleagridis subtypes (147). They correspond to types 1 and 2 at the small-subunit (SSU) rRNA locus and IIIb and IIIc subtype families at the gp60 locus. As they also have different nucleotide sequences at the MSC6-5 and RPGR loci, they probably represent two segregated C. meleagridis populations (147). Thus far, the biological significance of the two C. meleagridis populations is not clear. In the Peruvian study, group 1 was found in both chickens and humans, and 2 of the 14 multilocus subtypes of C. meleagridis in the group were found in both AIDS patients and birds, suggesting that indeed zoonotic transmission might be involved. In contrast, group 2 was found only in humans. Nevertheless, the number of avian isolates characterized was small. Population genetic analysis of the MLST data suggests a clonal population of C. meleagridis in the study community (147).

Cryptosporidium canis is the only Cryptosporidium species found in dogs in most molecular epidemiological studies of cryptosporidiosis in companion animals (148). It has been commonly reported in humans in low- and middle-income countries. For most studies, only a few cases were positive for C. canis, but unusually high infection rates (>10% of cryptosporidiosis cases) were reported in children in Cambodia and Angola as well as HIV-positive patients in Thailand and Venezuela (26, 130, 149, 150). In Venezuela, all the C. canis-positive patients kept dogs during the survey, indicating a possible occurrence of zoonotic transmission, although no survey of dogs was done (149). Although zoonotic transmission between humans and dogs has been identified using a genotyping tool (151), the transmission from pet dogs to humans is considered a low risk (20). Currently, no subtyping tools are available for C. canis, which has seriously impeded our understanding of the transmission of C. canis between humans and dogs. In a multilocus characterization of C. canis specimens from 12 HIV-infected persons from Lima, Peru, three were coinfected with C. hominis, indicating that some of the C. canis infections in humans were probably of anthroponotic origins (152).

Similar to C. canis in canine animals, C. felis is the dominant Cryptosporidium species in cats and other felines (148). It is commonly reported in humans in low- and middle-income countries. Possible transmission of C. felis between cats and humans has been reported (153). In Peru, some of the C. felis-infected AIDS patients were coinfected with C. hominis and C. meleagridis, suggesting that not all C. felis infections in humans are the result of zoonotic transmission (152). Recently, a subtyping tool based on sequence analysis of the gp60 gene has been developed for C. felis. It was used in the confirmation of two cases of zoonotic transmission of C. felis in Sweden (154). Thus far, it has been used in the characterization of human specimens from China, India, Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, Jamaica, and Peru, suggesting potential host adaption as well as geographic isolation in C. felis (155).

Cryptosporidium viatorum was first reported in travelers back to Britain from India (89) and has been reported in humans in India, China, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Colombia (32, 34, 67, 104, 125, 156–158). In particular, a high prevalence of C. viatorum (>10% of cryptosporidiosis cases) was recognized in children and HIV-positive persons in Ethiopia and Colombia (67, 125, 157). A subtyping tool based on sequence analysis of the gp60 gene is available for C. viatorum (159). Thus, far, four subtype families have been identified, including XVa, XVb, XVc, and XVd, but only XVa subtypes have been identified in humans (159). Most XVa subtypes have only three copies of the TCA repeat in the trinucleotide repeat region of the gp60 gene. As there are minor sequence differences downstream from it, eight subtypes (namely, XVaA3a to XVaA3h) are recognized among them (23, 34, 159). Recently, these four C. viatorum subtype families, namely, XVa (XVaA6, XVaA3g, and XVaA3h), XVb (XVbA2G1), XVc (XVcA2G1a and XVcA2G1b), and XVd (XVdA3), have been reported in wild rats in Australia and China (160–162). Previously, C. viatorum was thought to be an anthroponotic species (163). As subtypes XVaA3g and XVaA3h have been found in both humans and wild rats, C. viatorum infections are probably of the rat origin (34, 143, 161). This is also supported by the occurrence of another rat intestinal Cryptosporidium species, C. occultus, in humans in low- and middle-income countries (34, 164). These two species are rarely detected in humans in industrialized nations, probably a reflection of better hygiene there.

Cryptosporidium muris is another Cryptosporidium species in rats and some other rodents but has been found in humans in a few studies in Kenya, Nigeria, Thailand, India, Saudi Arabia, Colombia, and Peru (24, 42, 144, 165–171). In agreement with this, macaque monkeys in China are commonly infected with C. muris (172). Unlike other human-pathogenic Cryptosporidium spp., C. muris is a gastric pathogen with a much longer patent period (173). A Cryptosporidium species related to it, C. andersoni, has also been found in some human cases (24). Two studies reported a high prevalence of C. andersoni in immunocompetent children and adults in China (174, 175). A multilocus subtyping tool is available for characterizing the transmission of C. muris and C. andersoni (176).

Except for the five species mentioned above, other human-pathogenic species such as C. ubiquitum, C. cuniculus, and Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I are seldom reported in low- and middle-income countries (39). Cryptosporidium ubiquitum is commonly found in the United States. Subtyping analysis of C. ubiquitum isolates from humans, animals, and water based on sequence analysis of the gp60 gene indicated that C. ubiquitum-infected lambs and contaminated drinking water were likely the sources for human infections (93). Cryptosporidium cuniculus was first reported in rabbits in the United States but is a common human pathogen in the United Kingdom and New Zealand, leading to one large outbreak of human cryptosporidiosis in the United Kingdom (177, 178). Cryptosporidium chipmunk genotype I was first found in rodents in the United States (179). Subtype analysis revealed that isolates from humans and wild animals shared high genetic identity at the gp60 locus, supporting the occurrence of zoonotic transmission in humans (92).

CONCURRENT INFECTIONS WITH MIXED CRYPTOSPORIDIUM SPECIES, MULTIPLE EPISODES OF INFECTIONS, AND SECONDARY TRANSMISSION

One consequence of the high prevalence and diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. in humans in low- and middle-income countries is the concurrence of mixed Cryptosporidium species. Most of the mixed infections are caused by C. hominis and C. parvum (Table 4). The clinical significance of coinfections with multiple Cryptosporidium species is not clear. In one study in India, while the distribution of Cryptosporidium species was similar between symptomatic and asymptomatic children, a much higher occurrence (8.7% of the cryptosporidiosis cases compared with 0.6%) of mixed infections with C. hominis and C. parvum was seen in symptomatic children (42). This indicates that coinfection with two or more Cryptosporidium spp. might have deleterious effects on children.

TABLE 4.

Concurrent infections with mixed Cryptosporidium species in low- and middle-income countries in recent studiesa

| Location | Study population | No. of isolates | Mixed infections (n) | Genotyping technique(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | |||||

| India | Children | 50 | C. hominis and C. meleagridis (2) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 256 |

| Immunocompromised children | 53 | C. hominis and C. meleagridis (5), C. hominis and C. parvum (2) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP, gp60-based PCR and sequencing | 117 | |

| Immunocompromised patients | 71 | C. hominis and C. parvum (2) | Species-specific DHFR-based PCR and qPCR | 50 | |

| Children | 473 | C. hominis and C. parvum (14), C. andersoni and C. muris (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 42 | |

| Bangladesh | Children | 268 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1), C. hominis and C. meleagridis (13), C. parvum and C. meleagridis (1) | SSU rRNA-based pan-Cryptosporidium qPCR | 10 |

| Cambodia | Children patients | 38 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based qPCR and multiplex qPCR | 130 |

| Qatar | Adults | 38 | C. hominis and C. parvum (4), C. parvum and C. meleagridis (3) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 180 |

| Saudi Arabia | Children | 35 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based and COWP-based PCR-RFLP | 166 |

| Africa | |||||

| Tunisia | HIV+ patients | 42 | C. hominis and C. meleagridis (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 99 |

| Egypt | Diarrheal patients | 18 | C. hominis and C. parvum (3) | COWP-based PCR-RFLP | 257 |

| Children | 14 | C. hominis and C. parvum (3) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 139 | |

| Ethiopia | HIV+ patients | 140 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 67 |

| Mozambique | HIV+ patients | 9 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 129 |

| Gambia | Children | 280 | C. hominis and C. parvum (5) | TaqMan array card-based qPCR | 31 |

| Nigeria | Children | 77 | C. hominis and C. parvum (4) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 258 |

| Children | 44 | C. hominis and C. parvum (4) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 242 | |

| HIV+ patients | 4 | C. hominis and C. meleagridis (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 259 | |

| Kenya | Diarrheal children | 151 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 260 |

| Malawi | Diarrheal children | 43 | C. hominis and C. parvum (5) | SSU rRNA-based and COWP-based PCR-RFLP | 261 |

| Uganda | Diarrheal children | 444 | C. hominis and C. parvum (18) | COWP-based PCR-RFLP | 262 |

| Americas | |||||

| Brazil | HIV+ patients | 26 | C. hominis and C. parvum (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 105 |

| Argentina | HIV+ patients | 15 | C. hominis and C. parvum (2) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 105 |

| Peru | Children | 156 | C. hominis and C. parvum (2), C. canis and C. meleagridis (1) | SSU rRNA-based PCR-RFLP | 124 |

| Children and HIV+ patients | 55 | C. hominis and C. meleagridis (7) | SSU rRNA-based PCR and MLST | 147 |

HIV+, HIV positive; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase; COWP, Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein gene.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of PCR products is widely used in the detection of mixed Cryptosporidium species. Using this approach, the concurrence of C. hominis in 14 of 95 C. parvum-infected children and of C. andersoni in one C. muris-infected child was identified in a recent study in India (42). Another study in Egypt identified coinfection of C. parvum in 3 of 10 C. hominis-infected children (139). Coinfections of C. parvum and C. hominis were also identified in HIV-positive patients in Argentina, Brazil, and Mozambique (105, 129). Concurrence of C. hominis and C. meleagridis was identified in children and migrant workers in Tunisia and Qatar (99, 180). Coinfections of C. hominis and C. canis/C. felis were also identified in HIV-infected patients in Peru (151).

The occurrence of mixed Cryptosporidium species may be more common than believed, as shown in some studies in which multiple molecular tools were used in the identification and characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. With the application of species-specific quantitative PCR (qPCR) in a study conducted in Bangladesh, coinfection with C. parvum or C. hominis was identified in 1 and 13 of 100 C. meleagridis-infected children, respectively. Coinfection with C. hominis was further identified in one of five C. parvum-infected children (10). The use of a similar approach identified the concurrence of C. parvum in 5 of 124 C. hominis-infected children in Gambia (31). Coinfection with C. hominis was identified in 7 of 55 C. meleagridis-positive children and AIDS patents in Peru (147). Thus, accurate identification of coinfections with multiple Cryptosporidium species can improve our understanding of the transmission of zoonotic Cryptosporidium species in humans.

Children in low- and middle-income countries can experience multiple episodes of cryptosporidiosis, possibly reflecting short-lived or incomplete protection against Cryptosporidium infection after the primary infection (39, 181). In a longitudinal birth cohort study conducted in Bangladesh, 118 of 302 Cryptosporidium-positive children had two to four episodes of infections before reaching the age of 2 years, with no significant decreases in parasite burden during repeated infections (9). In another 3-year birth cohort study in India, 81% (322/397) of children with cryptosporidiosis experienced multiple episodes of infections, with no reduction in the severity of diarrhea during repeated infections (42). Unexpectedly, there was no species-specific protection against reinfections (16, 42, 124). Protective immunity, however, could exert effects at the subtype level, as multiple episodes of C. hominis infection in children were more likely to be caused by different subtype families in a longitudinal birth cohort study conducted in Peru (124). Similar findings were obtained in another birth cohort study in Bangladesh; although four children experienced repeated infections with C. hominis, subtyping analysis revealed that they were caused by heterogeneous subtypes (29).

As one of the risk factors involved in the acquisition of cryptosporidiosis is contact with Cryptosporidium-positive patients, secondary transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in households is expected (33, 182). One case-control study of Cryptosporidium-infected children and their family members in Bangladesh demonstrated that the secondary infection rates were 35.8% (19/53) in urban case families and 7.8% (5/64) in rural case families. This was confirmed by results of subtype analysis of the C. hominis and C. parvum involved (25). The differences in rates of secondary transmission between the urban and rural study sites were attributed to differences in the dominant Cryptosporidium species (C. hominis versus C. meleagridis) and transmission routes (anthroponotic versus zoonotic) in the two communities. Cryptosporidium meleagridis appears to be less infectious than C. hominis (25). In a multicountry study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, identical gp60 subtypes of C. parvum or C. hominis were detected among two or more contacts in 36% of the 108 initial Cryptosporidium-positive cases followed, indicating a common occurrence of secondary transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. (33). Among them, the C. hominis subtype IeA11G3T3 was involved in a cluster that lasted over 32 days with 13 infected subjects in two neighboring households, while the C. hominis subtype IfA14G1 was detected in a cluster that lasted over 18 days with 11 infected subjects in two neighboring households.

CRYPTOSPORIDIUM GENETICS AND VIRULENCE

The clinical implications of different Cryptosporidium species and subtypes in humans are not yet clear. Studies of genotyping analyses indicated that C. hominis and C. parvum likely behaved differently in humans, with the former causing more severe clinical manifestations (183). Earlier studies in urban slums in Peru and Brazil found that children infected with C. hominis had higher oocyst shedding intensity and longer duration than those infected with C. parvum and other species (124, 184, 185). Similar results were also obtained in immunocompromised patients in India (50). Children infected with C. hominis showed significantly more severe diarrhea than those infected with other species in South India (186). In one pediatric study in Kuwait, C. hominis infections showed more severe fever and diarrhea than C. parvum infections (121). In a study conducted in Ethiopia, AIDS patients with C. hominis infections had both diarrhea and vomiting, while those with C. parvum infections had only diarrhea (67). Similarly, in immunocompromised patients in India, nausea and vomiting were more frequently found in C. hominis infections than in C. parvum infections (50). Cryptosporidium hominis also appears to be more virulent than C. meleagridis. In a study conducted in two communities in Bangladesh, diarrhea was present in approximately 30% of C. hominis infections but nearly absent in C. meleagridis infections (10).

Due to the differences in pathogenicity, C. hominis infection is expected to have more deleterious nutritional effects on infected children than C. parvum infection. In Brazil, in children under 3 months, the height-for-age Z scores (HAZ) showed significant declines with infection of C. hominis or C. parvum, but in children of 3 to 6 months following infections, only C. hominis-infected children showed continuous decline in HAZ scores, especially for asymptomatic infections (185). Similar results have also been found in children in India, where most infections were caused by C. hominis, and children with sequential infections had significantly lower HAZ scores and long-term effects on growth (16). In Sonora, Mexico, malnutrition was significantly associated with Cryptosporidium infection, especially for C. hominis (122). In one recent birth cohort study conducted in two areas in Bangladesh, however, although the dominant Cryptosporidium species were different between urban (C. hominis) and rural (C. meleagridis) areas, they had similar effects on HAZ scores and child growth (10).

Even within the same Cryptosporidium species, the clinical manifestations of cryptosporidiosis can differ among subtypes. In Peruvian children infected with C. hominis, IbA10G2 was associated with diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and general malaise, while other subtypes were associated only with diarrhea (124). This indicates that IbA10G2 is likely more virulent than other subtypes in C. hominis. This is partially support by the fact that almost all autochthonous C. hominis infections in Europe are caused by this subtype (187). In India, most cases with subtype Ib had vomiting and/or appetite loss, while all cases with Ia and Id showed chronic diarrhea (32). Differences in the severity of diarrhea have also been found between Ia and Id subtype families of C. hominis (77, 121).

To understand the differences in clinical symptoms and pathogenicity among C. hominis subtype families, population genetics and comparative genomics analyses have been used in the characterization of isolates. In Peru, genetic recombination was identified in the virulent subtype IbA10G2 by using comparative sequence analysis of 53 isolates at 32 genetic loci across chromosome 6. Using linkage disequilibrium and recombination analyses, limited genetic recombination was identified exclusively in the gp60 gene of IbA10G2, a major subtype responsible for the outbreaks of human cryptosporidiosis in industrialized nations. Intensive transmission of the virulent subtype IbA10G2 possibly had led to genetic recombination with other subtypes. In addition, selection for the IbA10G2 type sequence was detected in a 129-kb region around the gp60 gene, which had led to reduced sequence variation within the 129-kb region in the IbA10G2 subtype, reflecting the possible involvement of the gene or other linked genes in pathogenicity (188). This was supported by comparative genomics analysis of IbA10G2 isolates and other C. hominis subtypes in the United States, which revealed the occurrence of genetic recombination in IbA10G2 at the 5′ and 3′ ends of chromosome 6 and in the gp60 region, indicating that genetic recombination likely contributed to the emergence of these hypertransmissible subtypes (189). Comparative genomics analysis of the virulent IbA10G2 and other C. hominis subtypes in Europe has identified a loss-of-function mutation in the gene (cgd6_210) encoding COWP9 in chromosome 6 in all subtypes except IbA10G2. As expected, phylogenetic analysis of IbA10G2 and other C. hominis subtypes based on 743 coding sequences indicated that all the IbA10G2 genomes formed a unique clade in spite of the existence of some heterogeneity among the IbA10G2 isolates (190). Genetic recombination in C. hominis appears to be more common in low- and middle-income countries. A comparative genomics analysis of 32 C. hominis isolates from a longitudinal cohort study of children in a Bangladeshi community identified high rates of genetic recombination in the genomes, with the area around the gp60 gene being one of the seven highly polymorphic regions. Genetic recombination was confirmed by the decay of linkage disequilibrium in the C. hominis genome over <300 bp. Because of the common occurrence of genetic recombination, the relatedness of C. hominis genomes was not segregated by gp60 subtype (29). More Cryptosporidium species and subtypes should be sequenced to better understand the population structure and genetic determinants of virulence and high transmissibility in some Cryptosporidium species and subtypes (85, 191).

IMPLICATIONS FOR WASH (WATER, SANITATION, AND HYGIENE)-BASED INTERVENTION OF CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS IN LOW- AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES

The results of molecular epidemiological studies suggest that anthroponotic transmission plays a major role in the transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in humans in low- and middle-income countries (103). Since cryptosporidiosis in these countries occurs mostly in children under 2 years (2–4), targeted intervention should be implemented to control the occurrence of cryptosporidiosis in this population. This intervention should be implemented regardless of the occurrence of diarrhea and other clinical symptoms, as subclinical cryptosporidiosis can induce malnutrition and growth retardation (10).

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH)-based interventions have been used effectively in the prevention and control of diarrheal diseases (192). WASH is a collection of integrated prevention and control strategies for infectious diseases which aim to improve the provision of water (e.g., safe water source), sanitation (e.g., clean toilets), and hygiene (e.g., frequent handwashing) (193–195). Application of the WASH-based interventions, such as clean drinking water, toilets for sanitation, and handwashing with soaps for hygiene, can reduce the occurrence of diarrhea and thus has been recommended as a measure to interrupt the environmental transmission of enteric pathogens such as Cryptosporidium spp. (48, 196–199). It is estimated that WASH intervention can reduce infections with diarrhea by 15 to 50%, and up to 40% nonemergency cases can be eliminated by handwashing with soaps (200–202). In children less than 5 years in low-income countries, application of WASH interventions has led to a 27 to 56% reduction in diarrhea occurrence (203, 204). Among them, handwashing appears to be the most effective long-term WASH intervention (205). It has been shown to reduce the occurrence of giardiasis in young children in rural Bangladesh (206).

WASH-based interventions may be effective against cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries (81). The risk factors associated with cryptosporidiosis occurrence, including poor hygiene, unclean drinking water, open defecation, overcrowding, and diarrhea in household (66), are key targets of WASH interventions. Therefore, good personal hygiene practices are known to reduce the transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. and other intestinal parasites in children (207). This is further supported by the negative correlation between the occurrence of the C. parvum IIc subtype family in HIV-positive individuals and the percentage of the population with access to improved sanitation (126). The use of a point-of-use drinking water filter was shown recently to reduce the occurrence of Cryptosporidium infection in children in Rwanda (208).

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Data from molecular epidemiological studies of human cryptosporidiosis have significantly improved our understanding of the transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in low- and middle-income countries. We now have a better understanding of the infection sources of Cryptosporidium spp. in children and immunocompromised persons. We also have a better appreciation of the role of endemicity of cryptosporidiosis in the genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp., concurrence of multiple Cryptosporidium species, and multiple episodes of infections. The eminent association between cryptosporidiosis occurrence and poor hygiene has made WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene)-based interventions an economical intervention measure against cryptosporidiosis in low- and middle-income countries.

The number of molecular epidemiological studies of cryptosporidiosis conducted in low- and middle-income countries is small, considering the fact that the disease exerts its highest toll there. Most of the data on the distribution of Cryptosporidium species and C. parvum and C. hominis subtypes in humans in low- and middle-income settings have been generated from only a handful countries in Asia and South America by established research groups. As a result, our understanding of cryptosporidiosis epidemiology may be skewed by the underrepresentation of low-income countries where Cryptosporidium transmission is most intensive and risk factors for infections might be different (66). We have yet to take advantage of the recent large scale of global disease burden and mortality studies through genetic characterizations of Cryptosporidium spp. from these well-designed epidemiological investigations (6, 31). As molecular characterizations of specimens from longitudinal birth cohort studies have provided a wealth of data on the development of species- and subtype-specific immunity, differences in the virulence of Cryptosporidium species and subtypes, and intrafamilial transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. (9, 10, 29, 42, 124), these studies should be expanded to African nations. We also need to assess vigorously the effectiveness of existing WASH-based interventions for the prevention and control of cryptosporidiosis in humans in low- and middle-income countries (192, 209, 210). Improved hygiene education is urgently needed to enable longer lasting and improved WASH behaviors (211–214). As cryptosporidiosis is a major cause of malnutrition, the development and assessment of nutritional interventions are also urgently needed (72, 206).

The application of advanced molecular tools such as comparative genomics analyses could increase significantly the depth of research in molecular epidemiology of human cryptosporidiosis. The development of procedures for whole-genome sequencing of Cryptosporidium spp. in clinical specimens without pathogen isolation and passage in laboratory animals has increased the availability of whole-genome sequence data from major human-pathogenic Cryptosporidium species. Comparative analyses of these data have begun to shed light on the genetic determinants for host adaptation in some common C. parvum subtype families and the high virulence in some C. hominis subtype families. These studies have identified genetic recombination as the driving force for the emergence of host-adapted and virulent subtypes (85, 191, 215). Thus far, the number of comparative genomics studies has only been small in low- and middle-income countries (29).

The recent development of genetic manipulation tools for Cryptosporidium spp. promotes the identification and validation of new drug targets and development of new interventions against cryptosporidiosis (216, 217). Thus far, nitazoxanide remains the only drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating cryptosporidiosis (218). With the application of CRISPR/Cas9 techniques, one Cryptosporidium PI(4)K inhibitor was identified as a candidate drug against cryptosporidiosis (219). Another study applying the CRISPR/Cas9 tool showed that C. parvum salvages purine nucleotides through a single pathway, providing another target for the development of treatments for this pathogen (220). Comprehensive studies combining genetic, biochemical, and chemical techniques indicated that bicyclic azetidines can kill C. parvum in mice by inhibiting the phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase of parasites (221). The identification of these new targets should greatly facilitate the development of new drugs against cryptosporidiosis. The recent development of genetic tagging and conditional protein degradation systems might also facilitate studies on the genetic determinants of virulence in C. hominis and the identification of vaccine candidates in the Cryptosporidium proteome (222, 223).

Understanding the reasons for the dominance of C. parvum in humans and the common occurrence of its zoonotic subtype families IIa and IId in some areas would require the use of the “one health” approach. Thus far, the transmission of C. parvum IIa and IId subtypes in the Middle East and some other Muslim countries is poorly understood. This is largely due to the lack of genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in farm animals, especially ruminants, in these areas. Systematic sampling of both humans and ruminants in the same area, comparative analysis of C. parvum subtypes from humans and animals residing in the same households, and genotyping and subtyping of Cryptosporidium spp. in drinking source water would shed light on the infection sources and transmission routes of C. parvum in these areas. This would require collaboration among public health researchers, veterinarians, and environmental scientists, which has been advocated as a new measure for the prevention and control of zoonotic cryptosporidiosis (224–226).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our collaborators for molecular epidemiological studies of cryptosporidiosis.

Recent studies in this area were supported in part by the Guangdong Major Project of Basic and Applied Basic Research (grant no. 2020B0301030007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31820103014 and U1901208), the 111 Project (grant no. D20008), and the Innovation Team Project of Guangdong University (grant no. 2019KCXTD001).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Biographies

Xin Yang obtained his Ph.D. degree at the College of Veterinary Medicine, Huazhong Agricultural University, in 2018 and received postdoctoral training at the South China Agricultural University between 2018 and 2020. He is currently a lecturer at Northwest A & F University. Dr. Yang’s earlier research interest was mainly in the prevention and control of gastrointestinal nematodes in small ruminants. Since 2018, he has focused primarily on the molecular epidemiology and comparative genomics of Cryptosporidium in humans and animals. Dr. Yang has published over 20 original papers in international journals.

Yaqiong Guo obtained her Ph.D. degree and postdoctoral training at East China University of Science and Technology. She is currently an associate professor at South China Agricultural University. Her research interests are primarily molecular epidemiology and comparative genomics of foodborne and waterborne parasites, such as Cryptosporidium and Cyclospora. Dr. Guo has published over 20 original papers.

Lihua Xiao obtained his M.S. from Northeast Agricultural University in China, his Ph.D. from the University of Maine, and his postdoctoral training from The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine. He worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, first as a guest researcher and then as a senior staff scientist, for 25 years. He is currently a professor at South China Agricultural University. For the last 30 years, Dr. Xiao has focused largely on the taxonomy, molecular epidemiology, diagnosis, genomics, and environmental biology of Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and microsporidia in humans and animals. Dr. Xiao has published over 400 original papers, invited reviews, and book chapters.

Yaoyu Feng obtained her B.S. and M.S. from Nankai University and her Ph.D. from Tianjin University, China. She received postdoctoral training and worked as a research fellow at the National University of Singapore. From 2004 to 2016, she was a professor at Tongji University and East China University of Science and Technology. Dr. Feng is currently a professor at the South China Agricultural University, China. She has been working on the molecular epidemiology, pathogenesis, transmission, and environmental ecology of waterborne and foodborne pathogens, including Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and microsporidia. Dr. Feng has published over 170 original papers, invited reviews, and book chapters.

Contributor Information

Lihua Xiao, Email: lxiao1961@gmail.com.

Yaoyu Feng, Email: yyfeng@scau.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu J, Platts-Mills JA, Juma J, Kabir F, Nkeze J, Okoi C, Operario DJ, Uddin J, Ahmed S, Alonso PL, Antonio M, Becker SM, Blackwelder WC, Breiman RF, Faruque ASG, Fields B, Gratz J, Haque R, Hossain A, Hossain MJ, Jarju S, Qamar F, Iqbal NT, Kwambana B, Mandomando I, McMurry TL, Ochieng C, Ochieng JB, Ochieng M, Onyango C, Panchalingam S, Kalam A, Aziz F, Qureshi S, Ramamurthy T, Roberts JH, Saha D, Sow SO, Stroup SE, Sur D, Tamboura B, Taniuchi M, Tennant SM, Toema D, Wu Y, Zaidi A, Nataro JP, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Houpt ER. 2016. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to identify causes of diarrhoea in children: a reanalysis of the GEMS case-control study. Lancet 388:1291–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31529-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kotloff KL, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y, Farag T, Panchalingham S, Sow SO, Sur D, Zaidi AKM, Faruque ASG, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Hossain A, Das SK, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Mandomando I, Acacio S, Biswas K, Tennant SM, Verweij JJ, Sommerfelt H, Nataro JP, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. 2019. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: a 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Lancet Glob Health 7:e568–e584. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30076-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Abdelalim A, Abdollahpour I, Abdulkader RS, Abebe HT, Abebe M, Abebe Z, Abejie AN, Abera SF, Abil OZ, Abraha HN, Abrham AR, Abu-Raddad LJ, Accrombessi MMK, Acharya D, Adamu AA, Adebayo OM, Adedoyin RA, Adekanmbi V, Adetokunboh OO, Adhena BM, Adib MG, Admasie A, Afshin A, Agarwal G, Agesa KM, Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Ahmadi A, Ahmadi M, Ahmed MB, Ahmed S, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aichour MTE, Akbari ME, Akinyemi RO, Akseer N, Al-Aly Z, Al-Eyadhy A, Al-Raddadi RM, Alahdab F, et al. 2018. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392:1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Platts-Mills JA, Liu J, Rogawski ET, Kabir F, Lertsethtakarn P, Siguas M, Khan SS, Praharaj I, Murei A, Nshama R, Mujaga B, Havt A, Maciel IA, McMurry TL, Operario DJ, Taniuchi M, Gratz J, Stroup SE, Roberts JH, Kalam A, Aziz F, Qureshi S, Islam MO, Sakpaisal P, Silapong S, Yori PP, Rajendiran R, Benny B, McGrath M, McCormick BJJ, Seidman JC, Lang D, Gottlieb M, Guerrant RL, Lima AAM, Leite JP, Samie A, Bessong PO, Page N, Bodhidatta L, Mason C, Shrestha S, Kiwelu I, Mduma ER, Iqbal NT, Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Haque R, Kang G, Kosek MN, MAL-ED Network Investigators. 2018. Use of quantitative molecular diagnostic methods to assess the aetiology, burden, and clinical characteristics of diarrhoea in children in low-resource settings: a reanalysis of the MAL-ED cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 6:e1309–e1318. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Wu Y, Sow SO, Sur D, Breiman RF, Faruque AS, Zaidi AK, Saha D, Alonso PL, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ochieng JB, Omore R, Oundo JO, Hossain A, Das SK, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Adegbola RA, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Akinsola A, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acacio S, Biswas K, O'Reilly CE, Mintz ED, Berkeley LY, Muhsen K, Sommerfelt H, Robins-Browne RM, Levine MM. 2013. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 382:209–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sow SO, Muhsen K, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, Wu Y, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, Sur D, Zaidi AK, Faruque AS, Saha D, Adegbola R, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Bassat Q, Tamboura B, Sanogo D, Onwuchekwa U, Manna B, Ramamurthy T, Kanungo S, Ahmed S, Qureshi S, Quadri F, Hossain A, Das SK, Antonio M, Hossain MJ, Mandomando I, Nhampossa T, Acacio S, Omore R, Oundo JO, Ochieng JB, Mintz ED, O'Reilly CE, Berkeley LY, Livio S, Tennant SM, Sommerfelt H, Nataro JP, Ziv-Baran T, Robins-Browne RM, Mishcherkin V, Zhang J, Liu J, Houpt ER, Kotloff KL, Levine MM. 2016. The burden of Cryptosporidium diarrheal disease among children < 24 months of age in moderate/high mortality regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, utilizing data from the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khalil IA, Troeger C, Rao PC, Blacker BF, Brown A, Brewer TG, Colombara DV, De Hostos EL, Engmann C, Guerrant RL, Haque R, Houpt ER, Kang G, Korpe PS, Kotloff KL, Lima AAM, Petri WA, Jr, Platts-Mills JA, Shoultz DA, Forouzanfar MH, Hay SI, Reiner RC, Jr, Mokdad AH. 2018. Morbidity, mortality, and long-term consequences associated with diarrhoea from Cryptosporidium infection in children younger than 5 years: a meta-analyses study. Lancet Glob Health 6:e758–e768. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30283-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GBD 2016 Diarrhoeal Disease Collaborators. 2018. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of diarrhoea in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 18:1211–1228. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30362-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korpe PS, Haque R, Gilchrist C, Valencia C, Niu F, Lu M, Ma JZ, Petri SE, Reichman D, Kabir M, Duggal P, Petri WA, Jr. 2016. Natural history of cryptosporidiosis in a longitudinal study of slum-dwelling Bangladeshi children: association with severe malnutrition. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10:e0004564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steiner KL, Ahmed S, Gilchrist CA, Burkey C, Cook H, Ma JZ, Korpe PS, Ahmed E, Alam M, Kabir M, Tofail F, Ahmed T, Haque R, Petri WA, Jr, Faruque ASG. 2018. Species of cryptosporidia causing subclinical infection associated with growth faltering in rural and urban Bangladesh: a birth cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 67:1347–1355. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quihui-Cota L, Morales-Figueroa GG, Javalera-Duarte A, Ponce-Martinez JA, Valbuena-Gregorio E, Lopez-Mata MA. 2017. Prevalence and associated risk factors for Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections among children of northwest Mexico: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 17:852. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4822-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quihui-Cota L, Lugo-Flores CM, Ponce-Martínez JA, Morales-Figueroa GG. 2015. Cryptosporidiosis: a neglected infection and its association with nutritional status in schoolchildren in northwestern Mexico. J Infect Dev Ctries 9:878–883. doi: 10.3855/jidc.6751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]