Abstract

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) features extremely high rates of morbidity and mortality, with no specific and effective therapy. And local inflammation caused by the over-activated immune cells seriously damages the recovery of neurological function after ICH. Fortunately, immune intervention to microglia has provided new methods and ideas for ICH treatment. Microglia, as the resident immune cells in the brain, play vital roles in both tissue damage and repair processes after ICH. The perihematomal activated microglia not only arouse acute inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and cytotoxicity to cause neuron death, but also show another phenotype that inhibit inflammation, clear hematoma and promote tissue regeneration. The proportion of microglia phenotypes determines the progression of brain tissue damage or repair after ICH. Therefore, microglia may be a promising and imperative therapeutic target for ICH. In this review, we discuss the dual functions of microglia in the brain after an ICH from immunological perspective, elaborate on the activation mechanism of perihematomal microglia, and summarize related therapeutic drugs researches.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, microglia, neuroinflammation, neuroprotective, stroke

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) has become one of the most common and lethal diseases in the last decades (Zhou M. et al., 2019). It affects more than 2 million patients worldwide every year, with the majority in developing countries (Cordonnier et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2019). ICH represents 10–25% of all strokes but leads to more than 50% of the deaths (Lan et al., 2017b; Cordonnier et al., 2018). 43–51% of patients with ICH die within 30 days, and only 12–39% of survivors keep living independently which imposes an enormous burden upon healthcare systems (Zhou et al., 2014; An et al., 2017). Neither internal medical managements, including hemostasis and intensive blood pressure-reduction, nor surgery methods as hematoma evacuation, has been testified efficacious by clinical randomized controlled trials (Mayer et al., 2008; Mendelow et al., 2013; Hemphill et al., 2015; Baharoglu et al., 2016; Morotti et al., 2017; Cordonnier et al., 2018). However, inspiringly, immune intervention promises a specific therapy strategy when neurologists shift attention to ICH secondary injury. Lately, fingolimod has been demonstrated signally improved neurological functional recovery in patients with ICH by means of regulating immunocytes number and activity (Fu et al., 2014; Li Y.-J. et al., 2015).

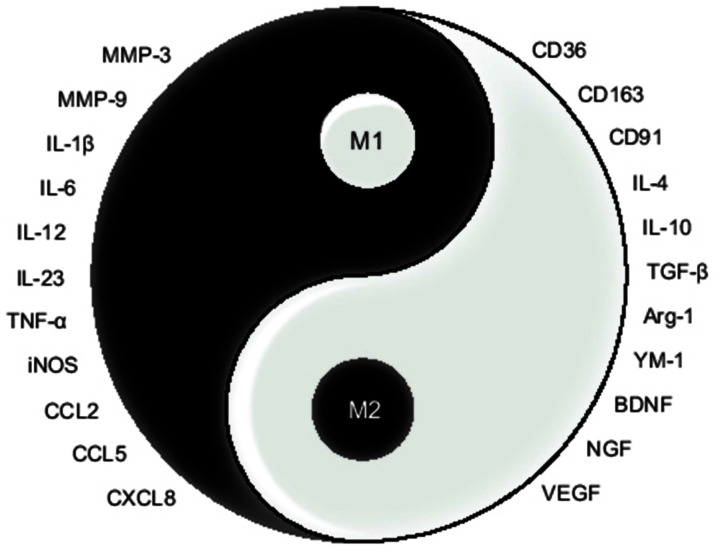

Microglia, as the resident immunocyte accounting for 5–10% of all human brain cells (Ma et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2021), take the lead in both tissue damage and repair processes after ICH. The perihematomal activated microglia not only arouse acute inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and cytotoxicity to damage neurovascular unit (M1 phenotype), but also transform the phenotype to inhibit inflammation, clear hematoma, and promote tissue regeneration (M2 phenotype). M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes play opposite functions, but they are actually complementary, interconnected, and can be transformed into each other, work coordinately and even interdependently (Hu et al., 2015; Orihuela et al., 2016), just like yin and yang in ancient Chinese philosophy. Their balance directly determines which way the pathophysiology goes towards, brain tissue repair or excessive damage. Thus, microglia may be a promising and imperative therapeutic target for ICH.

In this review, we describe the dualistic roles of microglia in ICH from an immunological perspective, expound on the detailed mechanism of perihematomal microglial activation and polarization, and summarize the related therapeutic researches.

Microglia

German neuropathologist Franz Nissl firstly discovered microglia with platinum stain in 1899 and called it “Staebchenzellen”. Then, Spanish neurohistologist Del Rio-Hortega coined the term “microglia” in 1919 and described in detail its superior ability of rapid proliferation, migration, and phagocytosis, which laid the groundwork for follow-up studies (Ginhoux and Prinz, 2015; ElAli and Rivest, 2016; Smolders et al., 2019).

After a century of exploration, microglia are customarily regarded as the macrophage in the brain due to the similarity in morphology, functions, and biomarkers (Nayak et al., 2014; Ginhoux and Prinz, 2015). Microglia can be identified with classical macrophage markers, such as ionized calcium binding adapter molecule1 (Iba1), surface glycoprotein F4/80, integrin CD11b, and the epitope of keratan sulfate 5D4 (Nayak et al., 2014; Dudvarski Stankovic et al., 2016; Lan et al., 2017b). However, microglia have been demonstrated to possess different embryological origin and transcriptional profile from that of macrophage, which suggest the functions of microglia and microphage are not identical. Microglia are recognized as Tmem119-positive and CD45-low, while macrophages are Tmem119-negetive and CD45-high (Li Q. et al., 2018).

Activated microglia have been found to differentiate into two broad subtypes with distinct cellular makers and biological functions (Sica and Mantovani, 2012; Zhao H. et al., 2015; Dudvarski Stankovic et al., 2016; Lan et al., 2017b; Ma et al., 2017; Li Q. et al., 2018; Tschoe et al., 2020). According to the M1/M2 dichotomy proposed by Mills in 2000, activated microglia are categorized into pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype (classical activation) and anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype (alternative activation). The process that resting microglia differentiate into M1/M2 phenotype is referred to as polarization. Recently, M2 microglia are alternatively divided into M2a/M2b/M2c subtypes. Classical inflammatory factors such as IL-1β, IL-6, and Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were used as the main markers of M1 microglia, while M2a microglia markers are represented by anti-inflammatory factors IL-4, IL-10, scavenger receptor CD36, and mannose receptor CD206, M2b microglia express major histocompatibility complex II (MCH-II), CD86, IL-10, and M2c microglia express phagocytic receptor CD163, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Different markers of microglia phenotypes show different roles that they play after ICH. The particular information on microglia subtypes is summarized in Table 1 (Lan et al., 2017b; Ma et al., 2017; Tschoe et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Particular information on microglia subtypes.

| Phenotype | Polarization agents | Makers | Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | LPS, IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17 | IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23 | pro-inflammation |

| TNF-α | pro-inflammation | ||

| iNOS | oxidative damage | ||

| MHC-II | antigen presentation | ||

| CCL2, CCL5, CCL20 | chemokine | ||

| CXCL10 | chemokine | ||

| MMP2, MMP9 | matrix decomposition | ||

| CD16, CD32 | phagocytosis, chemotaxis | ||

| M2 | |||

| M2a | IL-4, IL-13 | IL-4, IL-10 | anti-inflammation |

| TGF-β | anti-inflammation | ||

| CD36 | phagocytosis | ||

| CD206 | phagocytosis | ||

| CCL22 | chemokine | ||

| Arg-1 | tissue regeneration | ||

| Ym-1 | stabilizing extracellular matrix | ||

| Fizz1 | tissue regeneration | ||

| M2b | TLRs agonist, IL-1R ligands, Fc receptors | MCH-II | pro-inflammation |

| CD86 | pro-inflammation | ||

| IL-1RA | anti-inflammation | ||

| IL-10 | anti-inflammation | ||

| M2c | IL-10, TGF-β, glucocorticoid | CD163 | phagocytosis |

| IGF-1 | tissue regeneration | ||

| NGF | tissue regeneration | ||

| BDNF | tissue regeneration | ||

| NT3, NT4/5 | tissue regeneration | ||

| Arg-1 | tissue regeneration | ||

| YM-1 | stabilize extracellular matrix | ||

| Fizz1 | tissue regeneration |

LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IFN-γ, interferon γ; TNF-α-II, tumor necrosis factor α; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MHC-II, major histocompatibility complex II; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; Arg-1, arginine 1; Ym-1, chitinase 3-like 3; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; NGF, nerve growth factor; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; NT3, neurotrophin 3; NT4/5, neurotrophin 4/5; FIZZ1, resistin-like-α.

Spatiotemporal Pattern of Microglial Activation After ICH

As the immune monitor in the brain, microglia become activated immediately after ICH, make morphological changes from a highly ramified phenotype to a rod, spherical, and finally an amoeba shape with contracting, thickening, and largening (more than 7.5 μm in diameter; Walker et al., 2014; Yang S. S. et al., 2016; Shtaya et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2020).

Spatially, microglia usually show different activation levels, morphologies (ameboid, branched, or intermediate), and directivities in different distances from the hematoma (Wang G. et al., 2013; Yang S. S. et al., 2016). Amoeba microglia mainly appear in close proximity to the hematoma, and partial microglia are found activated away from the hematoma, such as the ipsilateral cerebral cortex, corpus callosum, and hippocampus.

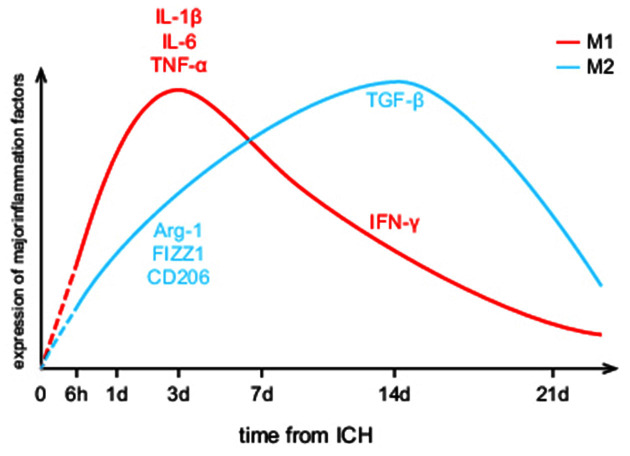

In the time course, microglia activation begins within 1–4 h, peaks in 1–3 days, declines at day 7, and returns to physiological level in 3–4 weeks after ICH (Zhou et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2019). As shown in Figure 1, both M1 and M2 phenotypes of microglia are presented in the perihematomal area throughout the course of the disease, while the M1/M2 proportion is continually changing. It stays in an M1-dominated state for a week after ICH and deflects to an M2 preponderance within 1–2 weeks (Wan et al., 2016). In animal models, M1 makers including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, including inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) increase dramatically within 3 days after ICH, while interferon-γ (IFN-γ) mostly increase in the later phase. The levels of M2 makers like Arginase-1 (Arg-1), resistin-like-α (Fizz1), CD206 go up gradually within 1 week and decline in 7–14 days except for transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which remains relatively high at days 14 (Zhao H. et al., 2015; Dang et al., 2017; Lan et al., 2017b; Taylor et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Dynamic changes of M1/M2 microglial activation levels after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). It provides a visual expression that M1/M2 microglia take on different activation characteristics. The red curve represents M1 microglia while the blue curve represents M2 microglia. Yet, the referenced researches about microglial spatiotemporal features are all animal experiments, leaving the human brain as an unknown area.

Notably, despite the time point is different, almost all microglial markers increase, which makes it difficult to faultlessly describe the dynamic phenotypic changes. With regard to this fact, it is better to evaluate microglial activation with as many makers as possible at present.

Functions of Activated Microglia After ICH

After ICH, blood swarms into the brain parenchyma causing an expanding hematoma which leads to immediate neurological impairment and microglial activation. Respectively, M1 microglia are commonly considered as the deleterious phenotype, and M2 microglia as the beneficial one (Xi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014), as shown in Figure 2. Microglia possess phenotypic and functional plasticity. Promoting M1-M2 phenotypic transformation has become the mainstream strategy of microglial intervention in ICH treatment.

Figure 2.

Sketch map for the opposite function of M1/M2 microglia. In this Tai Chi-diagram, the half-filled-out symbols with left half black represent M1 microglia, with the expression of MMPs, pro-inflammatory cytokine, and chemokine. And the right half white represents M2 microglia, with the expression of phagocytic receptors, anti-inflammatory cytokine, and growth factors.

M1 Microglia

M1 microglia secrete a large number of inflammatory factors, proteases, chemokines, prostaglandins, and other toxic substances. Since multiple damage-inducing factors overlap, brain cells die in various forms such as apoptosis, necrosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, which leads to the irreversible destruction of brain structure (Xi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014).

In brain parenchyma, M1 microglia are the major source of inflammatory mediators, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and TNF-α (Jiang et al., 2020). Although inflammation is essential for innate immunity, it is the chief culprit to the sustained neurological deterioration in a sterile environment (Zhu et al., 2019). While inflammatory cytokines diffuse, functional neurons and neuroglia quickly die under the stress condition (Shen et al., 2017). The diffused inflammatory cytokines also promote polarization of surrounding microglia towards the M1 phenotype, cause the inflammatory region to expand, which forms a vicious circle. In patients with ICH, the levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in plasma and brain tissues are significantly increased within 1–3 days, and the increasing degree is related to 90-days poor prognosis (Jiang et al., 2020). During pathological processes, oxidative stress and inflammation mutually reinforcing, which is no exception in ICH (Hu et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2021). M1 microglia express large amounts of peroxidases, iNOS, and reduced form of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which produce excessive free radicals and damage surrounding cells by attacking cellular membranes and DNA (Yang et al., 2013; Duan et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2016; Xiong et al., 2016). Moreover, M1 microglia contribute to the activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), including MMP2 and MMP9, which markedly destruct the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and cause severe vasogenic brain edema by degrading extracellular matrix constituents and attacking endothelial claudin-family tight junction proteins (Montaner et al., 2019). In ICH patients, increased MMP2/9 levels were independently associated with perihematomal edema volume (Li et al., 2013). In addition, M1 microglia also release chemokines including CXCL8, CCL2, and CCL5, which diffuse into peripheral blood through the ruptured blood vessel and attract peripheral leukocytes such as neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes into brain parenchyma through disrupted BBB (Trettel et al., 2020). It was reported that chemokines concentrations in plasma were proportional to the infiltration degree of peripheral immunocytes in ICH patients (Guo et al., 2020). The infiltrated immunocytes not only express and secrete inflammatory factors and aggravate inflammatory response but also release toxic substances after their apoptosis (Lambertsen et al., 2019). In ICH patients, CCL2 concentrations in plasma within 24 h were associated with poor functional outcomes at day 7 after ICH (Hammond et al., 2014). Also, inhibiting CCL2 in animal models reduced brain edema and improved neural function (Yan et al., 2020).

Noticeably, there is an evident cooperativity effect on tissue damage induced by inflammatory cytokines, protease MMPs, and chemokines. Inflammatory cytokines not only attack vascular endothelial cells and tight junction proteins but also induce endothelial cells to secrete intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), which promotes the adhesion and infiltration of peripheral leukocytes (Aslam et al., 2012). The direct damage on neurons induced by MMPs exacerbates inflammatory response, disrupts BBB to facilitate peripheral leukocytes infiltration (Kim et al., 2005). The infiltrated peripheral leukocytes secrete inflammatory factors and MMPs, which aggravates inflammatory response and BBB destruction in turn (Tschoe et al., 2020).

Although the treatments aiming at inflammatory cytokines are currently limited in animal experiments, TNF-α antibody has shown huge therapeutic potential by significantly reducing the number of perihematomal activated microglia and improving neurological outcomes in mouse stroke models (Mayne et al., 2001; Lei B. et al., 2013; Chen A.-Q. et al., 2019). Inhibition of TNF-α not only reduces the microglial activation/macrophage recruitment via decreasing cleaved caspase-3 level (Mayne et al., 2001; Lei B. et al., 2013; Chen A.-Q. et al., 2019) but also reduces the activation of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) on endothelium therefore reducing endothelium necroptosis and ameliorating disruption of BBB (Mayne et al., 2001; Lei B. et al., 2013; Chen A.-Q. et al., 2019). Predictably, inhibition of specific inflammatory factors is becoming the central theme of ICH therapeutic researches.

M2 Microglia

M2 microglia primarily express anti-s and facilitate tissue regeneration (Lan et al., 2017b). Thereby, the injured brain acquires comprehensive and effective recovery. Due to the large amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokines and antioxidants, the inflammatory response and oxidative become diminished tardily (Zhu et al., 2019). More importantly, the anti-inflammatory factors promote surrounding microglia and other immune cells to transform into anti-inflammatory phenotype. It’s found that patients with higher TGF-β levels in plasma had a better prognosis at 90 days after ICH (Jiang et al., 2020).

At the same time, M2 microglia engulf the hematoma and cells debris, remove harmful substances and provide space for tissue regeneration. With the increase of the number of M2 microglia, the volume of the hematoma is eliminated promptly in 7–21 days after ICH. B-scavenger receptor CD36, one of the M2 microglial makers, is the main executive of microglial phagocytosis activity, which is obviously induced to upregulate by IL-10 (Fang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021). In the mouse ICH model, CD36 knockout significantly inhibits hematoma absorption, and leads to the aggravation of neurological disorders (Fang et al., 2014). Instead, adoptive transferring CD36-positive microglia to CD36 knockout mice showed a significant improvement of neurological function after ICH (Yang et al., 2015). In fact, M2 microglia express CD163 and CD91 to absorb hemoglobin and heme, respectively (Dang et al., 2017; Garton et al., 2017). It should be noted that CD163 levels expressed by microglia may not be the only limiting factor in hematoma clearance. As a protective mechanism against severe hemolysis, the Haptoglobin (Hp) secreted by oligodendrocytes can capture free hemoglobin (Hb) to form a stable Hp-Hb complex, which is then englobed through CD163, thus reducing the toxicity of Hb. Similarly, hemopexin (Hx), secreted by neurons, binds with heme and is devoured via CD91 (Ma et al., 2016).

Particularly, M2 microglia are the drivers of brain tissue regeneration and remodeling. M2 microglia express various growth factors and trophic factors, such as insulin-like growth factors-1 (IGF-1), Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neurotrophin 3 (NT-3), NT-4/5, which could promote neurogenesis and neural circuit reframing (Xi et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2017). IGF-1 promotes the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of the neuro precursor cells in the subventricular zone, and facilitates the regenerated neurons’ functional integration into a new neural circuit (Thored et al., 2009). In a mouse ICH model, IGF-1 antibody promotes microglial M1 polarization, leading to more residual behavioral defects (Sun et al., 2020). BDNF and GDNF stimulate axon regeneration, which takes part in new neural connections (Madinier et al., 2009). The neurotrophic factors, including NT3 and NT4/5, are not only beneficial to the survival of residual neurons but also essential for the improvement and stability of the newborn neuron (Ma et al., 2017). During the remodeling of brain tissue, M2 microglia secrete clotting substance chitinase 3-like 3 (Ym-1) to prevent the degradation of extracellular matrix components (Girard et al., 2013). M2 marker Arg-1 not only converts arginine into polyamine which contributes to extracellular matrix subsidence but also competes with iNOS for reaction substrates to inhibit the excessive oxidative stress (Munder, 2009).

In general, M2 microglia resist inflammation and engulf hematomas to create a calm and stable microenvironment, which contributes to the neuro-angiogenesis and matrix deposition, and allows brain tissue to regain structure and function. Nevertheless, because of M1 microglia domination, only a third of new neurons survive inflammation in the acute phase. Therefore, promoting a beneficial microglial phenotypic transformation is a promising way in ICH treatment.

Polarization Mechanism of Microglia After ICH

In order to regulate microglial polarization accurately and effectively, it is necessary to understand the mechanism of microglial polarization, including the source of extracellular stimuli and intracellular signaling pathways, which has been briefly summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Signaling pathways of microglia polarization.

| Microglia phenotype | Intracellular signal molecule | Extracellular agents | Effect molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | TLRs-NF-κB | Hb, hemin | NLRP3; IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α |

| fibrinogen | |||

| HMGB1, nucleic acids, heat shock protein | |||

| Prxs | |||

| MAPK-NF-κB | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | ||

| thrombin | |||

| glucocorticoid | |||

| STAT1 | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | ||

| M2 | PPAR/Nrf2 | Peroxisome | Arg-1, IL-4, CD36, HO-1 |

| STAT4/6 | IL-4, IL-10 | Ym-1, Fizz1 |

Extracellular Agents

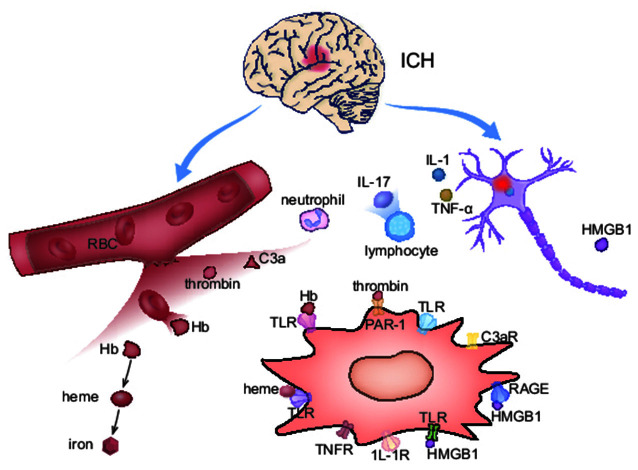

After ICH, blood carrying red blood cells (RBCs) and plasma proteins including thrombin and fibrinogen infiltrate into the brain parenchyma, and trigger the initiation of early cellular and molecular pathological processes. Hematoma not only contains the agents that directly activate microglia but also promote microglial M1-polarization indirectly through tissue damage. Figure 3 provides an overview of M1-polarization.

Figure 3.

The activation mechanism of M1 microglia after ICH. In ICH acute phase, M1 microglia are activated on account of the blood composition and neuron primary damage. Meanwhile, microglia up-express corresponding receptors for activation.

Because of energy exhaustion and cytotoxicity, RBCs in the hematoma begin to lyse within 1 day and continue for weeks after ICH (Righy et al., 2016). The damaged RBCs release Hb, peroxiredoxins (Prxs), and Carbonic Anhydrase-1 (CA-1), which induce microglia differentiating into M1-phenotype (Guo et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016; Bian et al., 2020). Hb and the decomposed product hemin can directly promote microglial M1-polarization through Toll-like receptors (TLRs; Lin et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2014). Therefore, clearing hematoma is of importance in reducing brain damage. Since no reliable clinical benefits are provided from surgical hematoma removal at present, promoting hematoma devouring by microglia is of great significance.

During the formation of hematoma, thrombin and complements are produced in the brain, which are also important factors for M1-polarization. Thrombin, a serine protease that promotes blood clotting, is detected in the brain within 1 h after ICH (Zhu et al., 2019). Thrombin directly activates M1 microglia by binding to the proteinase-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1; Wan et al., 2016). In mouse models, delayed administration of thrombin inhibitor hirudin in 7–28 days after ICH significantly reduced the number of pro-inflammatory microglia (Li et al., 2019). However, thrombin regulation is difficult to apply to clinical therapy because of its two-sided effects. Though the inhibition of thrombin shows a beneficial effect in inflammation reduction, a suitable thrombin concentration is necessary for helping stop hemorrhage and protect neurons. Complements, anaphylatoxins, are activated within 24 h through various proximal cascaded pathways (Ducruet et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2017). Complement composition C3a activates microglia cells by binding to the specific receptor C3aR. Membrane attack complex (MAC), the end product of complement cascade, attacks cell membrane, and leads to erythrocyte lysis and neuronal death, which indirectly exacerbates microglial M1-polarization. In animal models, complement inhibitor N-acetyl heparin inhibits microglia activation and ameliorates neurological deficits (Wang M. et al., 2019).

Besides, brain tissue primary damage also contributes to microglial polarization (Zhang et al., 2017). Neurons and astroglia around the hematoma express inflammatory factors such as IL-15 and IL-17, playing a vital role in M1 polarization (Yu et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2018, 2020). Likewise, damaged neurons and glia release damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including high mobility group protein-1 (HMGB1), heat shock proteins, and extracellular matrix fragments (Mracsko and Veltkamp, 2014; Bobinger et al., 2018). HMGB1 is a non-chromosome-related protein widely expressed in the nucleus of all eukaryotic cells (Mu et al., 2018). Under physiological conditions, HMGB1 helps stabilize chromosomes and regulate the transcription of many survival-based genes, but once it is dissociated from the nucleus and released outside the cell, HMGB1 becomes a powerful inflammatory mediator that promotes microglial M1 polarization by binding to TLRs on microglia (Ohnishi et al., 2011; Wang D. et al., 2017). In rodent ICH models, glycyrrhizin attenuates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced injury in a concentration-dependent manner via inhibiting HMGB1 (Ohnishi et al., 2011; Mu et al., 2018). HMGB1 inhibitor Ethyl-pyruvate significantly reduced microglia activation and inflammatory factors levels via inhibiting nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) DNA binding activity (Su et al., 2013).

In the later phase of ICH, an anti-inflammatory pathway, enlisting native microglia, occurs alongside neuroinflammation (Shtaya et al., 2021). Anti-inflammatory factors such as IL-4, IL-33, IL-10, TGF-β increase distinctly around the hematoma, which are mostly released by macrophages, mature lymphocytes, and mast cells (Taylor et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Chen Z. et al., 2019). The immune microenvironment changes shift microglial polarization from M1 to M2. Intraventricular injection of IL-4 in mice increases the proportion of M2 microglia and accelerates the recovery of neurological function after ICH (Yang J. et al., 2016). Some other molecular targets have also been recently identified up-regulated on microglia during M2-polarization after ICH, including Dopamine D1 receptor (DRD1), Cannabinoid receptor-2 (CB2R), Melanocortin receptor 4 (MC4R), and especially sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR; Xu et al., 2013; Li L. et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015).

Intracellular Signal Transduction

To recognize extracellular agents and transduce extracellular signals, microglia express various membrane receptors, nuclear receptors, and executive proteins to play roles in morphological and functional changes such as secretion, phagocytosis, and movement. Understanding microglial signal transduction is beneficial to the exploration of clinical targets. Here, we briefly introduce several important receptors and signaling molecules.

TLRs-NF-κB

TLR is a type I transmembrane protein that plays an important role in the innate immune and inflammatory response (Alvarado and Lathia, 2016). So far, 10 functional TLRs have been found in humans, and microglia mainly express TLR4, TLR2, and heterodimer TLR2/4 (Fang et al., 2013; Hayward and Lee, 2014; Wang et al., 2014). Hb, hemin, fibrinogen, HMGB1, heat shock protein, Prxs, and nucleic acids generated during ICH are all TLRs ligands (Lin et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2021). After binding to these ligands, TLRs signaling is activated. TLR4 simultaneously activates two parallel downstream pathways of myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) and TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β (TRIF) while TLR2 recruits only MyD88. Both of them lead to the activation of transcription factor NF-κB (Sansing et al., 2011; Wang Y.-C. et al., 2013; Fei et al., 2019). NF-κB is a crucial signal for microglial M1-polarization and inflammatory factors expression. During the process, inhibitors of NF-κB kinase (IKK) are activated firstly, which cause the phosphorylation and degradation of NF-κB inhibitor (Iκb; Fei et al., 2019). After that, NF-κB dimer is released and enters the nucleus to regulate transcription for M1-polarization. Of note, NF- κB can be detected in the peripheral circulation, which is a biomarker to determine the severity of brain damage.

MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a member of the serine/threonine kinase family, which includes P38, Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways (Sun and Nan, 2016). MAPK not only enters the nucleus to regulate the transcription processes but also increases the activity of NF-κB in the cytoplasm (Wei et al., 2019). After ICH, MAPK is activated by inflammatory factors, thrombin, and glucocorticoid, MAPK signaling plays a critical role in microglia survival and M1-polarization.

NLRP3

Inflammasome NLR Family, Pyrin domain containing protein 3 (NLRP3) is a kind of intracellular multi-molecular protein complex that is involved in inflammation (Walsh et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2019). NLRP3 activates lyase caspase-1, an enzyme that trims microglia secreted pre-IL-1β and pre-IL-18 into mature IL-1β and IL-18 (Ren et al., 2018), which makes NLRP3 a promising target of inflammatory regulation. In the mouse ICH model, intraventricular injection of NLRP3 siRNA immediately reduced inflammatory response and brain damage.

PPAR-γ and Nrf2

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR-γ) and Nuclear erythroid 2 related factor 2 (Nrf2) are important signals of M2-polarization (Zhao X.-R. et al., 2015). Nrf2 is a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) protein that enters the nucleus to regulate transcription. PPAR-γ is a highly-expressed nuclear hormone receptor in microglia. PPAR-γ and Nrf2 actually work together with overlapping functions. They enhance the expression of Arg-1, IL-4, and CD36, which enables microglia in phagocytosis and tissue repair (Xia et al., 2015; Wang J. et al., 2018). Except for that, PPAR-γ and Nrf2 jointly regulate the expression of hundreds of antioxidant genes including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1; Culman et al., 2007; Shang et al., 2013).

STATs

As a common transcription signal for cytokines, signal transducer and activator of transcriptions (STATs) family exert their effect on both M1 and M2 polarization (Tschoe et al., 2020). Microglia express a large number of cytokine receptors, such as IL-1R, TNFR, IL-4R, which activate the downstream Janus kinase (JAK)-STATs signal. Among STATs, STAT1 promotes M1 polarization and inflammatory factors expression (Bai et al., 2020). STAT4/6 promotes M2 polarization and the expression of Ym-1 and Fizz1 (Righy et al., 2016). Intriguingly, STAT3 was demonstrated to be involved in both M1/M2 polarization (Hu et al., 2015).

M1-M2 Phenotypic Transformation

It is observed that single microglia express both M1/M2 phenotypic markers (Ransohoff, 2016; Tschoe et al., 2020). Neither M1 nor M2 should be considered as a microglial final differentiation form. The ability of microglia to switch between M1/M2 phenotypes is always a fascinating topic. However, the mechanism for this phenotypic transformation is really elusive. M1 and M2 microglia not only perform distinct cellular functions but also have incompatible polarization processes. For example, in vitro, PPAR-γ significantly inhibits the activation of NF-κB and STAT1/3 (Fang et al., 2014). In like manner, inflammatory cytokines and TLRs inhibit microglia in CD36 expression (Zhou et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2015).

Recently, the relationship between microglia phenotype and metabolic status has attracted much attention. Microglia in different phenotypes show different oxidative metabolism (Eun Jung et al., 2020). Compared to M1 microglia, M2 microglia have significantly lower oxygen consumption (Orihuela et al., 2016). Therefore, it has been speculated that intracellular stress environment and energy crisis promote M2 polarization by influencing mitochondrial metabolism. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) released by M1 microglia has been found to activate Nrf2, which contributes to microglial M2 polarization (Duan et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2016; Qu et al., 2016). In addition, Adenosine 5‘-monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK), as a key molecule regulating bioenergy metabolism, is activated under cellular energy crisis and oxidative stress (Saikia and Joseph, 2021). Evidence indicates that AMPK contributes to Nrf2 activation as well (Zhao et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). In other words, the initiative activation of M2 microglia may be a type of self-protection when M1 phenotype creates an immoderate oxidative stress (Barakat and Redzic, 2015). More in-depth research in the mechanism of microglial phenotypic transformation may provide insights into innovative therapeutic strategies for ICH.

Preclinical Researches Targeting Microglia

In view of the serious inflammatory brain injury, whole microglia population deletion by knocking out microglial survival signal receptor colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) achieved an early therapeutic effect in rodent experiments (Li et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2019). Of course, increasing the M2/M1 phenotypic proportion of microglia usually brings more satisfactory results (Wang J. et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2020), and it has become the most frequently studied therapeutic method. Relying on the aforementioned targets, experimental therapeutic studies on the precise regulation on microglia phenotype are developing rapidly, and relevant drugs are summarized in Table 3 (Hu et al., 2011; Ohnishi et al., 2013, 2019; Yang et al., 2014a,b, 2018; Iniaghe et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2015a,b, 2018; Flores et al., 2016; Shi et al., 2016; Sukumari-Ramesh and Alleyne, 2016; Zhang et al., 2016; Anan et al., 2017; Chen-Roetling and Regan, 2017; Lan et al., 2017a; Wang J. et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2017; Chen C. et al., 2018; Chen S. et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2018; Han et al., 2018; Li X. et al., 2018; Qiao et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018b; Liang et al., 2019; Song and Zhang, 2019; Xi et al., 2019; Zhou F. et al., 2019; Cheng et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2020).

Table 3.

Preclinical researches on microglial regulation for ICH therapy.

| Drugs | Targets | Species/Models | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginkgolide B | TLR4 | rats/autologous blood | reduce inflammatory cytokine, lessen neuronal cell apoptosis. |

| Ligustilide | TLR4 | mice/autologous blood | reduce inflammatory cytokine, induced neurological deficits. |

| Magnolol | TLR4 | rats/collagenase | reduce the brain water content, attenuated neurological deficits. |

| Pinocembrin | NF-κB | mice/collagenase | reduce lesion volume and neurologic deficits. |

| Sparstolonin B | NF-κB | mice/autologous blood | reduce inflammatory cytokine and brain edema. |

| Curcumin | NF-κB | mice/autologous blood | inhibit inflammation and neurological impairment. |

| Protocatechuic acid | NF-κB | mice/collagenase | inhibit oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. |

| Annexin A1 | MAPK | mice/collagenase | attenuate brain edema, improved short-term neurological function. |

| Sesamin | MAPK | rats/collagenase | suppress microglial activation, prevent neuron loss. |

| Fisetin | NF-κB | mice/collagenase | reduce inflammatory cytokine, brain edema and cell apoptosis. |

| Theaflavin | NF-κB | rats/collagenase | alleviate the behavioral defects, inhibit the neuron loss and apoptosis. |

| fimasartan | NLRP3 | rats/collagenase | attenuate brain edema and improve neurological functions. |

| dexmedetomidine | NLRP3 | mice/autologous blood | reduce inflammatory cytokine, improve neurological function. |

| AC-YVAD-CMK | NLRP3 | mice and rats/collagenase | reduce brain edema and improve neurological function. |

| MCC950 | NLRP3 | mice/autologous blood and collagenase | attenuate neuro-deficits and perihematomal brain edema. |

| Dimethyl fumarate | Nrf2 | mice and rats/collagenase and autologous blood | improve neurological deficits. |

| Nicotinamide mononucleotide | Nrf2 | mice/collagenase | suppress neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. |

| Shogaol | Nrf2 | mice/collagenase | suppress oxidative stress and improve neurological function. |

| sulforaphane | Nrf2 | mice and rats/ autologous blood | improve hematoma clearance. |

| Tert-butylhydroquinone | Nrf2 | mice/collagenase | suppress oxidative stress and improve neurological function. |

| Isoliquiritigenin | Nrf2 | rats/collagenase | alleviate neurological deficits. |

| Andrographolide | rats/autologous blood | alleviate neurobehavioral disorders and brain edema. | |

| monascin | Nrf2 | rats/collagenase | improve neurological deficits. |

| Sinomenine | Nrf2 | mice/autologous blood | improve neurological deficits. |

Clinical Researches Targeting Microglia

Translational research in medication development has never been effortless. Although many preclinical researches have got positive results in ICH treatment, large clinical trials on microglia intervention are second to none. Conservatively, the therapeutic effect of minocycline, deferoxamine, fingolimod, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), and statins are relatively promising. Related clinical researches have been briefly summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Clinical researches on microglial regulation for ICH therapy.

| Drugs | Continent | No. of patients | Outcomes | Efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| minocycline | North America | 10 | NIHSS, mRS, mortality | NO | Chang et al. (2017) |

| North America | 8 | mRS | NO | Fouda et al. (2017) | |

| deferoxamine mesylate | Asian | 47 | hematoma volume, edema | YES | Yu et al. (2017) |

| fingolimod | Asian | 23 | hematoma volume, NIHSS | YES | Fu et al. (2014) |

| Asian | 11 | edema | YES | Li et al. (2015) | |

| statins | Europe | 29 | NIHSS, mortality | YES | Tapia-Pérez et al. (2013) |

| North America | 38 | hematoma volume; edema | YES | Witsch et al. (2019) |

NIHSS, National Institute of Health stroke scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

Minocycline is an ordinary broad-spectrum antibiotic. It could pass through the blood-brain barrier freely and has a neuronal protection effect (Yang et al., 2019). With pleiotropic properties, minocycline scavenges free radical and promotes M1-M2 phenotypic transformation of microglia in piglet and rodent ICH models (Möller et al., 2016; Dai et al., 2019; Wang G. et al., 2019). When applied in ICH clinical trials, minocycline has not been demonstrated to produce favorable outcomes on 3-month functional independence and behavior score, but significantly depresses the levels of circulating inflammatory components (Fouda et al., 2017; Malhotra et al., 2018). It may be due to the fact that oral administration does not produce sufficient potency concentrations in brain parenchyma.

Deferoxamine is a classical iron-chelating agent. Except for reducing oxidative damage, it effectively reinforces the function of M2 microglia (Hu et al., 2019). RBC CD47 is a signal that stops itself from being swallowed by microglia (Song et al., 2021; Ye et al., 2021). Deferoxamine inhibited CD47 expression on RBCs and accelerated hematoma absorption conspicuously in pig models (Cao et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2019). In patients with spontaneous ICH, consecutive administration of deferoxamine mesylate for 5 days significantly reduces hematoma volume and brain edema progression (Yu et al., 2017).

Fingolimod is an S1PR agonist previously used for multiple sclerosis, which can directly activate M2 microglia. In ICH preclinical experiments, fingolimod has been demonstrated to inhibit brain edema and reduce the numbers of apoptotic cells (Rolland et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2016). When applied to clinical trials, 3 days consecutive oral administration of fingolimod shows beneficial effects on decreasing the numbers of lymphocytes and NK cells in circulation, controlling perihematomal brain edema (PHE), and ameliorating neurological deficits (Fu et al., 2014; Li Y.-J. et al., 2015).

TZDs, including pioglitazone and rosiglitazone, have a function in activating M2 microglia as PPAR-γ agonist (Song et al., 2018). In the rodent model, intraperitoneal injection of rosiglitazone increases the expression of CD36 on microglia, promotes hematoma clearance, and inhibits inflammatory factors expression (Chang C.-F. et al., 2017; Mu et al., 2017). TZDs have long been designed for clinical trials (Gonzales et al., 2013), but have not yet shown significant results.

Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) are widely prescribed medications for the management of hypercholesterolemia. The potential of Statins for ICH treatment has been revealed recently (Chen Q. et al., 2019). Mechanistically, Statins regulate microglial phenotype by inhibiting inflammatory signals and enhancing PPAR-γ activity (Wang et al., 2018a; Bagheri et al., 2020). Although stains have been doubted for the safety of ICH treatment, they are ultimately deemed applicable in promoting neurological rehabilitation (Ribe et al., 2019). It has been demonstrated that statins improve the neurological function of ICH patients and reduce the mortality at 6 months (Tapia-Pérez et al., 2013; Witsch et al., 2019).

Perspective

The Balance of Yin and Yang

Though how to regulate microglia to promote brain recovery remains worth pondering in some sense, there are latent misgivings that excessive inhibition of M1 microglia and promotion of M2 microglia may turn into adverse effects in ICH treatment, where we should keep watchful eyes.

On the one hand, the immunoreactive materials secreted from M1 microglia appear to have delayed beneficial effects on brain repair. Solid evidence indicates that MMPs are necessary for angiogenesis, myelin remodeling, and axonal regeneration in ICH later stage (Lei et al., 2015; Fields, 2019). As well, infiltrating neutrophils and monocytes have been found conducive to hematoma clearance and inflammation regression (Lambertsen et al., 2019). Besides, the over-suppressed inflammatory status may increase brain infection risk since the systemic immunity also decreases after ICH (Saand et al., 2019).

On the other hand, the early organizational disruption may build the basis of neogenesis. M1 microglia destroy dying and defunct neurons in pieces, which lends a convenience for M2 phagocytosis (Hu et al., 2015). In addition, the deconstruction of dense tissue matrix made by M1 microglia provides space for the migration of neural precursors and synaptic remodeling (Lei C. et al., 2013). Also, M1 microglia impair BBB integrity, which is in favor of the hematoma clearance by free diffusion, especially when microglial phagocytic receptors are of inefficiencies in the ICH early phase (Righy et al., 2016, 2018).

As for M2 microglia, superfluous and prolonged existing growth factors will predictably cause abnormal tissue repair. Overexpression of Arg1 has been found to cause tissue scarring and brain dysfunction (Hesse et al., 2001), and excessive polyamines extraordinarily promote inflammatory response (Dudvarski Stankovic et al., 2016). Resting microglia plays a special role in tissue repair and remodeling (Cherry et al., 2014), and M2-M0 may be a necessary functional transformation after ICH.

In summary, it is really improper to consider that M1 and M2 microglial phenotypes are thoroughly opposite. Instead, their interaction, cooperation, and even codependency are waiting to be explored in the future. A balance of M1 and M2 microglial, rather than extremely choosing M2 over M1, ought to be achieved for ICH individualized treatment, just like the balance of yin and yang.

Targeting Strategy

Although drugs with the pleiotropic ability of immune regulation may bring more benefits, not a few medical experiments failed just because of uncontrolled side effects. It is a neglected consensus that many microglial receptors and signaling molecules are meanwhile expressed or activated in other brain cells, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, and neurons. It is unwise to judge the holistic functions of concerned targets in the brain by taking only microglia into account. For example, CD163 helps microglia engulf and break down hemoglobin, whereas, inhibition of CD163 in the ICH acute phase unexpectedly reduces brain damage, possibly because inhibition of CD163 expressed on neurons decreases the Hb neurotoxicity induced neuronal death (Righy et al., 2018).

Hence, we need a kind of drug that has a high targeting specificity to microglia. Preferably, it’s expected to have sufficient liposoluble ability to pass through BBB and concentrate on microglia. Furthermore, it’s recommended to conjunctive use advanced medical technology such as intranasal administration, nanomaterials, and genetic technologies to achieve better intervention results for ICH treatment.

Author Contributions

RB and ZF wrote and revised the manuscript. MY helped with the literature search and correction of the manuscript. BH and QH provided the conception and design of the review, and directed the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFC1312200 to BH), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant: 81820108010 to BH), and Major Refractory Diseases Pilot Project of Clinical Collaboration with Chinese and Western Medicine (SATCM-20180339 to BH).

References

- Alvarado A. G., Lathia J. D. (2016). Taking a toll on self-renewal: TLR-mediated innate immune signaling in stem cells. Trends Neurosci. 39, 463–471. 10.1016/j.tins.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S. J., Kim T. J., Yoon B.-W. (2017). Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: an update. J. Stroke 19, 3–10. 10.5853/jos.2016.00864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anan J., Hijioka M., Kurauchi Y., Hisatsune A., Seki T., Katsuki H. (2017). Cortical hemorrhage-associated neurological deficits and tissue damage in mice are ameliorated by therapeutic treatment with nicotine. J. Neurosci. Res. 95, 1838–1849. 10.1002/jnr.24016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam M., Ahmad N., Srivastava R., Hemmer B. (2012). TNF-α induced NFκB signaling and p65 (RelA) overexpression repress Cldn5 promoter in mouse brain endothelial cells. Cytokine 57, 269–275. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri H., Ghasemi F., Barreto G. E., Sathyapalan T., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. (2020). The effects of statins on microglial cells to protect against neurodegenerative disorders: a mechanistic review. Biofactors 46, 309–325. 10.1002/biof.1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharoglu M. I., Cordonnier C., Al-Shahi Salman R., de Gans K., Koopman M. M., Brand A., et al. (2016). Platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 387, 2605–2613. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30392-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Q., Xue M., Yong V. W. (2020). Microglia and macrophage phenotypes in intracerebral haemorrhage injury: therapeutic opportunities. Brain 143, 1297–1314. 10.1093/brain/awz393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat R., Redzic Z. (2015). Differential cytokine expression by brain microglia/macrophages in primary culture after oxygen glucose deprivation and their protective effects on astrocytes during anoxia. Fluids Barriers CNS 12:6. 10.1186/s12987-015-0002-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian L., Zhang J., Wang M., Keep R. F., Xi G., Hua Y. (2020). Intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury in rats: the role of extracellular peroxiredoxin 2. Transl. Stroke Res. 11, 288–295. 10.1007/s12975-019-00714-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobinger T., Burkardt P., Huttner B. H., Manaenko A. (2018). Programmed cell death after intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 16, 1267–1281. 10.2174/1570159X15666170602112851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S., Zheng M., Hua Y., Chen G., Keep R. F., Xi G. (2016). Hematoma changes during clot resolution after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 47, 1626–1631. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J. J., Kim-Tenser M., Emanuel B. A., Jones G. M., Chapple K., Alikhani A., et al. (2017). Minocycline and matrix metalloproteinase inhibition in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: a pilot study. Eur. J. Neurol. 24, 1384–1391. 10.1111/ene.13403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.-F., Wan J., Li Q., Renfroe S. C., Heller N. M., Wang J. (2017). Alternative activation-skewed microglia/macrophages promote hematoma resolution in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiol. Dis. 103, 54–69. 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A.-Q., Fang Z., Chen X.-L., Yang S., Zhou Y.-F., Mao L., et al. (2019). Microglia-derived TNF-α mediates endothelial necroptosis aggravating blood brain-barrier disruption after ischemic stroke. Cell Death Dis. 10:487. 10.1038/s41419-019-1716-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Xu N., Dai X., Zhao C., Wu X., Shankar S., et al. (2019). Interleukin-33 reduces neuronal damage and white matter injury via selective microglia M2 polarization after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 150, 127–135. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Yao L., Cui J., Liu B. (2018). Fisetin protects against intracerebral hemorrhage-induced neuroinflammation in aged mice. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 45, 154–161. 10.1159/000488117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Zhang J., Feng H., Chen Z. (2019). An update on statins: pleiotropic effect performed in intracerebral hemorrhage. Atherosclerosis 284, 264–265. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Zhao L., Sherchan P., Ding Y., Yu J., Nowrangi D., et al. (2018). Activation of melanocortin receptor 4 with RO27–3225 attenuates neuroinflammation through AMPK/JNK/p38 MAPK pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 15:106. 10.1186/s12974-018-1140-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., Chen B., Xie W., Chen Z., Yang G., Cai Y., et al. (2020). Ghrelin attenuates secondary brain injury following intracerebral hemorrhage by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and promoting Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol 79:106180. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Roetling J., Regan R. F. (2017). Targeting the Nrf2-heme oxygenase-1 axis after intracerebral hemorrhage. Curr. Pharm. Des. 23, 2226–2237. 10.2174/1381612822666161027150616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry J. D., Olschowka J. A., O’Banion M. K. (2014). Are “resting” microglia more “m2”? Front. Immunol. 5:594. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier C., Demchuk A., Ziai W., Anderson C. S. (2018). Intracerebral haemorrhage: current approaches to acute management. Lancet 392, 1257–1268. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31878-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culman J., Zhao Y., Gohlke P., Herdegen T. (2007). PPAR-γ: therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28, 244–249. 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S., Hua Y., Keep R. F., Novakovic N., Fei Z., Xi G. (2019). Minocycline attenuates brain injury and iron overload after intracerebral hemorrhage in aged female rats. Neurobiol. Dis. 126, 76–84. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang G., Yang Y., Wu G., Hua Y., Keep R. F., Xi G. (2017). Early erythrolysis in the hematoma after experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 8, 174–182. 10.1007/s12975-016-0505-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Flores J., Klebe D., Li P., McBride D. W., Tang J., et al. (2020). Annexin A1 attenuates neuroinflammation through FPR2/p38/COX-2 pathway after intracerebral hemorrhage in male mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 98, 168–178. 10.1002/jnr.24478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X., Wen Z., Shen H., Shen M., Chen G. (2016). Intracerebral hemorrhage, oxidative stress, and antioxidant therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016:1203285. 10.1155/2016/1203285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducruet A. F., Zacharia B. E., Hickman Z. L., Grobelny B. T., Yeh M. L., Sosunov S. A., et al. (2009). The complement cascade as a therapeutic target in intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp. Neurol. 219, 398–403. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudvarski Stankovic N., Teodorczyk M., Ploen R., Zipp F., Schmidt M. H. H. (2016). Microglia-blood vessel interactions: a double-edged sword in brain pathologies. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 347–363. 10.1007/s00401-015-1524-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ElAli A., Rivest S. (2016). Microglia ontology and signaling. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 4:72. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun Jung J., Sun G., Bautista Garrido J., Obertas L., Mobley A. S., Ting S. M., et al. (2020). The mitochondria-derived peptide humanin improves recovery from intracerebral hemorrhage: implication of mitochondria transfer and microglia phenotype change. J. Neurosci. 40, 2154–2165. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2212-19.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Chen J., Lin S., Wang P., Wang Y., Xiong X., et al. (2014). CD36-mediated hematoma absorption following intracerebral hemorrhage: negative regulation by TLR4 signaling. J. Immunol. 192, 5984–5992. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H., Wang P.-F., Zhou Y., Wang Y.-C., Yang Q.-W. (2013). Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in intracerebral hemorrhage-induced inflammation and injury. J. Neuroinflammation 10:27. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei X., He Y., Chen J., Man W., Chen C., Sun K., et al. (2019). The role of Toll-like receptor 4 in apoptosis of brain tissue after induction of intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation 16:234. 10.1186/s12974-019-1634-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields G. B. (2019). Mechanisms of action of novel drugs targeting angiogenesis-promoting matrix metalloproteinases. Front. Immunol. 10:1278. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores J. J., Klebe D., Rolland W. B., Lekic T., Krafft P. R., Zhang J. H. (2016). PPARγ-induced upregulation of CD36 enhances hematoma resolution and attenuates long-term neurological deficits after germinal matrix hemorrhage in neonatal rats. Neurobiol. Dis. 87, 124–133. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.12.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouda A. Y., Newsome A. S., Spellicy S., Waller J. L., Zhi W., Hess D. C., et al. (2017). Minocycline in acute cerebral hemorrhage: an early phase randomized trial. Stroke 48, 2885–2887. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Hao J., Zhang N., Ren L., Sun N., Li Y. J., et al. (2014). Fingolimod for the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage: a 2-arm proof-of-concept study. JAMA Neurol. 71, 1092–1101. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu G., Wang H., Cai Y., Zhao H., Fu W. (2018). Theaflavin alleviates inflammatory response and brain injury induced by cerebral hemorrhage via inhibiting the nuclear transcription factor κ β-related pathway in rats. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 12, 1609–1619. 10.2147/DDDT.S164324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Fu X., Zeng H., Zhao J., Zhou G., Zhou H., Zhuang J., et al. (2021). Inhibition of dectin-1 ameliorates neuroinflammation by regulating microglia/macrophage phenotype after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Transl. Stroke Res. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s12975-021-00889-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garton T., Keep R. F., Hua Y., Xi G. (2017). CD163, a hemoglobin/haptoglobin scavenger receptor, after intracerebral hemorrhage: functions in microglia/macrophages versus neurons. Transl. Stroke Res. 8, 612–616. 10.1007/s12975-017-0535-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F., Prinz M. (2015). Origin of microglia: current concepts and past controversies. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a020537. 10.1101/cshperspect.a020537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard S., Brough D., Lopez-Castejon G., Giles J., Rothwell N. J., Allan S. M. (2013). Microglia and macrophages differentially modulate cell death after brain injury caused by oxygen-glucose deprivation in organotypic brain slices. Glia 61, 813–824. 10.1002/glia.22478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales N. R., Shah J., Sangha N., Sosa L., Martinez R., Shen L., et al. (2013). Design of a prospective, dose-escalation study evaluating the Safety of Pioglitazone for Hematoma Resolution in Intracerebral Hemorrhage (SHRINC). Int. J. Stroke 8, 388–396. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00761.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Hua Y., Wang J., Keep R. F., Xi G. (2012). Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase reduces brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Transl. Stroke Res. 3, 130–137. 10.1007/s12975-011-0106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F., Xu D., Lin Y., Wang G., Wang F., Gao Q., et al. (2020). Chemokine CCL2 contributes to BBB disruption via the p38 MAPK signaling pathway following acute intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB J. 34, 1872–1884. 10.1096/fj.201902203RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond M. D., Taylor R. A., Mullen M. T., Ai Y., Aguila H. L., Mack M., et al. (2014). CCR2+ Ly6C(hi) inflammatory monocyte recruitment exacerbates acute disability following intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurosci. 34, 3901–3909. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4070-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Liu D.-L., Zeng Q.-K., Shi M.-Q., Zhao L.-X., He Q., et al. (2018). The neuroprotective effects and probable mechanisms of Ligustilide and its degradative products on intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 63, 43–57. 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward J. H., Lee S. J. (2014). A decade of research on TLR2 discovering its pivotal role in glial activation and neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 23, 138–147. 10.5607/en.2014.23.2.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill J. C., III., Greenberg S. M., Anderson C. S., Becker K., Bendok B. R., Cushman M., et al. (2015). Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 46, 2032–2060. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse M., Modolell M., La Flamme A. C., Schito M., Fuentes J. M., Cheever A. W., et al. (2001). Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J. Immunol. 167, 6533–6544. 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S., Hua Y., Keep R. F., Feng H., Xi G. (2019). Deferoxamine therapy reduces brain hemin accumulation after intracerebral hemorrhage in piglets. Exp. Neurol. 318, 244–250. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.-Y., Huang M., Dong X.-Q., Xu Q.-P., Yu W.-H., Zhang Z.-Y. (2011). Ginkgolide B reduces neuronal cell apoptosis in the hemorrhagic rat brain: possible involvement of Toll-like receptor 4/nuclear factor-κ B pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137, 1462–1468. 10.1016/j.jep.2011.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Leak R. K., Shi Y., Suenaga J., Gao Y., Zheng P., et al. (2015). Microglial and macrophage polarization-new prospects for brain repair. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 11, 56–64. 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X., Tao C., Gan Q., Zheng J., Li H., You C. (2016). Oxidative stress in intracerebral hemorrhage: sources, mechanisms, and therapeutic targets. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016:3215391. 10.1155/2016/3215391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iniaghe L. O., Krafft P. R., Klebe D. W., Omogbai E. K. I., Zhang J. H., Tang J. (2015). Dimethyl fumarate confers neuroprotection by casein kinase 2 phosphorylation of Nrf2 in murine intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurobiol. Dis. 82, 349–358. 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C., Wang Y., Hu Q., Shou J., Zhu L., Tian N., et al. (2020). Immune changes in peripheral blood and hematoma of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB J. 34, 2774–2791. 10.1096/fj.201902478R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., Kim S. S., Cho J. J., Choi D. H., Hwang O., Shin D. H., et al. (2005). Matrix metalloproteinase-3: a novel signaling proteinase from apoptotic neuronal cells that activates microglia. J. Neurosci. 25, 3701–3711. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4346-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertsen K. L., Finsen B., Clausen B. H. (2019). Post-stroke inflammation-target or tool for therapy? Acta Neuropathol. 137, 693–714. 10.1007/s00401-018-1930-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X., Han X., Li Q., Li Q., Gao Y., Cheng T., et al. (2017a). Pinocembrin protects hemorrhagic brain primarily by inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 and reducing M1 phenotype microglia. Brain Behav. Immun. 61, 326–339. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X., Han X., Li Q., Yang Q.-W., Wang J. (2017b). Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13, 420–433. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B., Dawson H. N., Roulhac-Wilson B., Wang H., Laskowitz D. T., James M. L. (2013). Tumor necrosis factor α antagonism improves neurological recovery in murine intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation 10:103. 10.1186/1742-2094-10-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C., Lin S., Zhang C., Tao W., Dong W., Hao Z., et al. (2013). Activation of cerebral recovery by matrix metalloproteinase-9 after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuroscience 230, 86–93. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei C., Wu B., Cao T., Zhang S., Liu M. (2015). Activation of the high-mobility group box 1 protein-receptor for advanced glycation end-products signaling pathway in rats during neurogenesis after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 46, 500–506. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.-J., Chang G.-Q., Liu Y., Gong Y., Yang C., Wood K., et al. (2015). Fingolimod alters inflammatory mediators and vascular permeability in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosci. Bull. 31, 755–762. 10.1007/s12264-015-1532-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Lan X., Han X., Durham F., Wan J., Weiland A., et al. (2021). Microglia-derived interleukin-10 accelerates post-intracerebral hemorrhage hematoma clearance by regulating CD36. Brain Behav. Immun. 94, 437–457. 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Lan X., Han X., Wang J. (2018). Expression of Tmem119/Sall1 and Ccr2/CD69 in FACS-sorted microglia- and monocyte/macrophage-enriched cell populations after intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 12:520. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Li Z., Ren H., Jin W.-N., Wood K., Liu Q., et al. (2017). Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibition eliminates microglia and attenuates brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 37, 2383–2395. 10.1177/0271678X16666551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Liu Y. F., Ma L., Worthmann H., Wang Y. L., Wang Y. J., et al. (2013). Association of molecular markers with perihematomal edema and clinical outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 44, 658–663. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.673590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Tao Y., Tang J., Chen Q., Yang Y., Feng Z., et al. (2015). A cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist prevents thrombin-induced blood-brain barrier damage via the inhibition of microglial activation and matrix metalloproteinase expression in rats. Transl. Stroke Res. 6, 467–477. 10.1007/s12975-015-0425-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Wang T., Zhang D., Li H., Shen H., Ding X., et al. (2018). Andrographolide ameliorates intracerebral hemorrhage induced secondary brain injury by inhibiting neuroinflammation induction. Neuropharmacology 141, 305–315. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhu Z., Gao S., Zhang L., Cheng X., Li S., et al. (2019). Inhibition of fibrin formation reduces neuroinflammation and improves long-term outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Int. Immunopharmacol. 72, 473–478. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H., Sun Y., Gao A., Zhang N., Jia Y., Yang S., et al. (2019). Ac-YVAD-cmk improves neurological function by inhibiting caspase-1-mediated inflammatory response in the intracerebral hemorrhage of rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 75:105771. 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S., Yin Q., Zhong Q., Lv F.-L., Zhou Y., Li J.-Q., et al. (2012). Heme activates TLR4-mediated inflammatory injury via MyD88/TRIF signaling pathway in intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation 9:46. 10.1186/1742-2094-9-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Liu L., Wang X., Jiang R., Bai Q., Wang G. (2021). Microglia: a double-edged sword in intracerebral hemorrhage from basic mechanisms to clinical research. Front. Immunol. 12:675660. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.675660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D.-L., Zhao L.-X., Zhang S., Du J.-R. (2016). Peroxiredoxin 1-mediated activation of TLR4/NF-κB pathway contributes to neuroinflammatory injury in intracerebral hemorrhage. Int. Immunopharmacol. 41, 82–89. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Barfejani A. H., Qin T., Dong Q., Ayata C., Waeber C. (2014). Fingolimod exerts neuroprotective effects in a mouse model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res. 1555, 89–96. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.01.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y., Reis C., Chen S. (2019). NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathophysiology of hemorrhagic stroke: a review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 17, 582–589. 10.2174/1570159X17666181227170053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B., Day J. P., Phillips H., Slootsky B., Tolosano E., Dore S. (2016). Deletion of the hemopexin or heme oxygenase-2 gene aggravates brain injury following stroma-free hemoglobin-induced intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroinflammation 13:26. 10.1186/s12974-016-0490-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Wang J., Wang Y., Yang G.-Y. (2017). The biphasic function of microglia in ischemic stroke. Prog. Neurobiol. 157, 247–272. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madinier A., Bertrand N., Mossiat C., Prigent-Tessier A., Beley A., Marie C., et al. (2009). Microglial involvement in neuroplastic changes following focal brain ischemia in rats. PLoS One 4:e8101. 10.1371/journal.pone.0008101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra K., Chang J. J., Khunger A., Blacker D., Switzer J. A., Goyal N., et al. (2018). Minocycline for acute stroke treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Neurol. 265, 1871–1879. 10.1007/s00415-018-8935-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer S. A., Brun N. C., Begtrup K., Broderick J., Davis S., Diringer M. N., et al. (2008). Efficacy and safety of recombinant activated factor VII for acute intracerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2127–2137. 10.1056/NEJMoa0707534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne M., Ni W., Yan H. J., Xue M., Johnston J. B., Del Bigio M. R., et al. (2001). Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-α expression is neuroprotective after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 32, 240–248. 10.1161/01.str.32.1.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelow A. D., Gregson B. A., Rowan E. N., Murray G. D., Gholkar A., Mitchell P. M., et al. (2013). Early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar intracerebral haematomas (STICH II): a randomised trial. Lancet 382, 397–408. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60986-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller T., Bard F., Bhattacharya A., Biber K., Campbell B., Dale E., et al. (2016). Critical data-based re-evaluation of minocycline as a putative specific microglia inhibitor. Glia 64, 1788–1794. 10.1002/glia.23007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J., Ramiro L., Simats A., Hernandez-Guillamon M., Delgado P., Bustamante A., et al. (2019). Matrix metalloproteinases and ADAMs in stroke. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 76, 3117–3140. 10.1007/s00018-019-03175-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morotti A., Brouwers H. B., Romero J. M., Jessel M. J., Vashkevich A., Schwab K., et al. (2017). Intensive blood pressure reduction and spot sign in intracerebral hemorrhage: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 74, 950–960. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mracsko E., Veltkamp R. (2014). Neuroinflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:388. 10.3389/fncel.2014.00388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu S.-W., Dang Y., Wang S.-S., Gu J.-J. (2018). The role of high mobility group box 1 protein in acute cerebrovascular diseases. Biomed. Rep. 9, 191–197. 10.3892/br.2018.1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q., Wang L., Hang H., Liu C., Wu G. (2017). Rosiglitazone pretreatment influences thrombin-induced phagocytosis by rat microglia via activating PPARγ and CD36. Neurosci. Lett. 651, 159–164. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munder M. (2009). Arginase: an emerging key player in the mammalian immune system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 158, 638–651. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak D., Roth T. L., McGavern D. B. (2014). Microglia development and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 32, 367–402. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi M., Katsuki H., Fukutomi C., Takahashi M., Motomura M., Fukunaga M., et al. (2011). HMGB1 inhibitor glycyrrhizin attenuates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced injury in rats. Neuropharmacology 61, 975–980. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi M., Monda A., Takemoto R., Matsuoka Y., Kitamura C., Ohashi K., et al. (2013). Sesamin suppresses activation of microglia and p44/42 MAPK pathway, which confers neuroprotection in rat intracerebral hemorrhage. Neuroscience 232, 45–52. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.11.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi M., Ohshita M., Tamaki H., Marutani Y., Nakayama Y., Akagi M., et al. (2019). Shogaol but not gingerol has a neuroprotective effect on hemorrhagic brain injury: contribution of the α, β-unsaturated carbonyl to heme oxygenase-1 expression. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 842, 33–39. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuela R., McPherson C. A., Harry G. J. (2016). Microglial M1/M2 polarization and metabolic states. Br. J. Pharmacol. 173, 649–665. 10.1111/bph.13139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H.-B., Li J., Lv L.-J., Nie B.-J., Lu P., Xue F., et al. (2018). Eupatilin inhibits microglia activation and attenuates brain injury in intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp. Ther. Med. 16, 4005–4009. 10.3892/etm.2018.6699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J., Chen W., Hu R., Feng H. (2016). The injury and therapy of reactive oxygen species in intracerebral hemorrhage looking at mitochondria. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016:2592935. 10.1155/2016/2592935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransohoff R. M. (2016). A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat. Neurosci. 19, 987–991. 10.1038/nn.4338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H., Kong Y., Liu Z., Zang D., Yang X., Wood K., et al. (2018). Selective NLRP3 (pyrin domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome inhibitor reduces brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 49, 184–192. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribe A. R., Vestergaard C. H., Vestergaard M., Fenger-Gron M., Pedersen H. S., Lietzen L. W., et al. (2019). Statins and risk of intracerebral haemorrhage in a stroke-free population: a nationwide danish propensity score matched cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 8, 78–84. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righy C., Bozza M. T., Oliveira M. F., Bozza F. A. (2016). Molecular, cellular and clinical aspects of intracerebral hemorrhage: are the enemies within? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 392–402. 10.2174/1570159x14666151230110058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righy C., Turon R., Freitas G., Japiassu A. M., Faria Neto H. C. C., Bozza M., et al. (2018). Hemoglobin metabolism by-products are associated with an inflammatory response in patients with hemorrhagic stroke. Rev. Bras. Ter. Intensiva. 30, 21–27. 10.5935/0103-507x.20180003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland W. B., Lekic T., Krafft P. R., Hasegawa Y., Altay O., Hartman R., et al. (2013). Fingolimod reduces cerebral lymphocyte infiltration in experimental models of rodent intracerebral hemorrhage. Exp. Neurol. 241, 45–55. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saand A. R., Yu F., Chen J., Chou S. H. (2019). Systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic strokes—a novel neurological sign and therapeutic target? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 39, 959–988. 10.1177/0271678X19841443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikia R., Joseph J. (2021). AMPK: a key regulator of energy stress and calcium-induced autophagy. J. Mol. Med. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s00109-021-02125-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansing L. H., Harris T. H., Welsh F. A., Kasner S. E., Hunter C. A., Kariko K. (2011). Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann. Neurol. 70, 646–656. 10.1002/ana.22528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang H., Yang D., Zhang W., Li T., Ren X., Wang X., et al. (2013). Time course of Keap1-Nrf2 pathway expression after experimental intracerebral haemorrhage: correlation with brain oedema and neurological deficit. Free Radic. Res. 47, 368–375. 10.3109/10715762.2013.778403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H., Liu C., Zhang D., Yao X., Zhang K., Li H., et al. (2017). Role for RIP1 in mediating necroptosis in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage model both in vivo and in vitro. Cell Death Dis. 8:e2641. 10.1038/cddis.2017.58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S. X., Li Y.-J., Shi K., Wood K., Ducruet A. F., Liu Q. (2020). IL (Interleukin)-15 bridges astrocyte-microglia crosstalk and exacerbates brain injury following intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 51, 967–974. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi E., Shi K., Qiu S., Sheth K. N., Lawton M. T., Ducruet A. F. (2019). Chronic inflammation, cognitive impairment and distal brain region alteration following intracerebral hemorrhage. FASEB J. 33, 9616–9626. 10.1096/fj.201900257R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Wang J., Wang J., Huang Z., Yang Z. (2018). IL-17A induces autophagy and promotes microglial neuroinflammation through ATG5 and ATG7 in intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroimmunol. 323, 143–151. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Zheng K., Su Z., Su H., Zhong M., He X., et al. (2016). Sinomenine enhances microglia M2 polarization and attenuates inflammatory injury in intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neuroimmunol. 299, 28–34. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtaya A., Bridges L. R., Esiri M. M., Lam-Wong J., Nicoll J. A. R., Boche D., et al. (2019). Rapid neuroinflammatory changes in human acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 6, 1465–1479. 10.1002/acn3.50842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shtaya A., Bridges L. R., Williams R., Trippier S., Zhang L., Pereira A. C., et al. (2021). Innate immune anti-inflammatory response in human spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A., Mantovani A. (2012). Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 787–795. 10.1172/JCI59643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]