ABSTRACT

Stomatal development is tightly connected with the overall plant growth, while changes in environmental conditions, like elevated temperature, affect negatively stomatal formation. Stomatal ontogenesis follows a well-defined series of cell developmental transitions in the cotyledon and leaf epidermis that finally lead to the production of mature stomata. YODA signaling cascade regulates stomatal development mainly through the phosphorylation and inactivation of SPEECHLESS (SPCH) transcription factor, while HSP90 chaperones have a central role in the regulation of YODA cascade. Here, we report that acute heat stress affects negatively stomatal differentiation, leads to high phosphorylation levels of MPK3 and MPK6, and alters the expression of SPCH and MUTE transcription factors. Genetic depletion of HSP90 leads to decreased stomatal differentiation rates. Thus, HSP90 chaperones safeguard the completion of distinct stomatal differentiation steps depending on these two transcription factors under normal and heat stress conditions.

KEYWORDS: Stomata, differentiation, heat shock proteins 90, mitogen-activated protein kinases

Stomata are small pores localized in the epidermis of the above-ground organs of plants. Their major function is to facilitate exchange of gases and water between plant and surrounding environment. Stomatal density and distribution in the epidermis is tightly connected with the overall plant growth and productivity. This is one of the main reasons why stomatal development and function attracted quite broad interest of the scientific community. Stomatal development is very sensitive to environmental fluctuations, such as temperature, osmotic stress, and carbon dioxide concentration.1 Considering that global warming influences all the environmental parameters that affect plant development, gaining new insights into the molecular mechanisms governing stomatal formation might provide a useful tool for the production of crops tolerant to adverse climate conditions.

During stomatal development, a dedicated protodermal cell entering stomatal lineage follows a well-characterized series of asymmetric and symmetric cell divisions that ultimately result in the formation of guard cells.2 Early stomatal ontogenesis is controlled by the transcription factor SPEECHLESS (SPCH).3,4 A signaling mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade including YODA (MAPKKK), MKK4/5 (MAPKKs), and MPK3/6 (MAPKs)5-7 is required for SPEECHLESS (SPCH) regulation. HEAT SHOCK PROTEINS 90 (HSP90s) are evolutionary conserved molecular chaperones that regulate numerous biological processes including organismal development and stress responses.8-17 Recently, we reported that the iterative application of acute heat stress conditions modulates the stomata formation via YODA-HSP90 module.16 HSP90s interact with YODA, affect its subcellular polarization, and modulate the phosphorylation of downstream targets, like MPK6 and SPCH, and the transcript levels of MUTE under both normal and heat-stress conditions.16

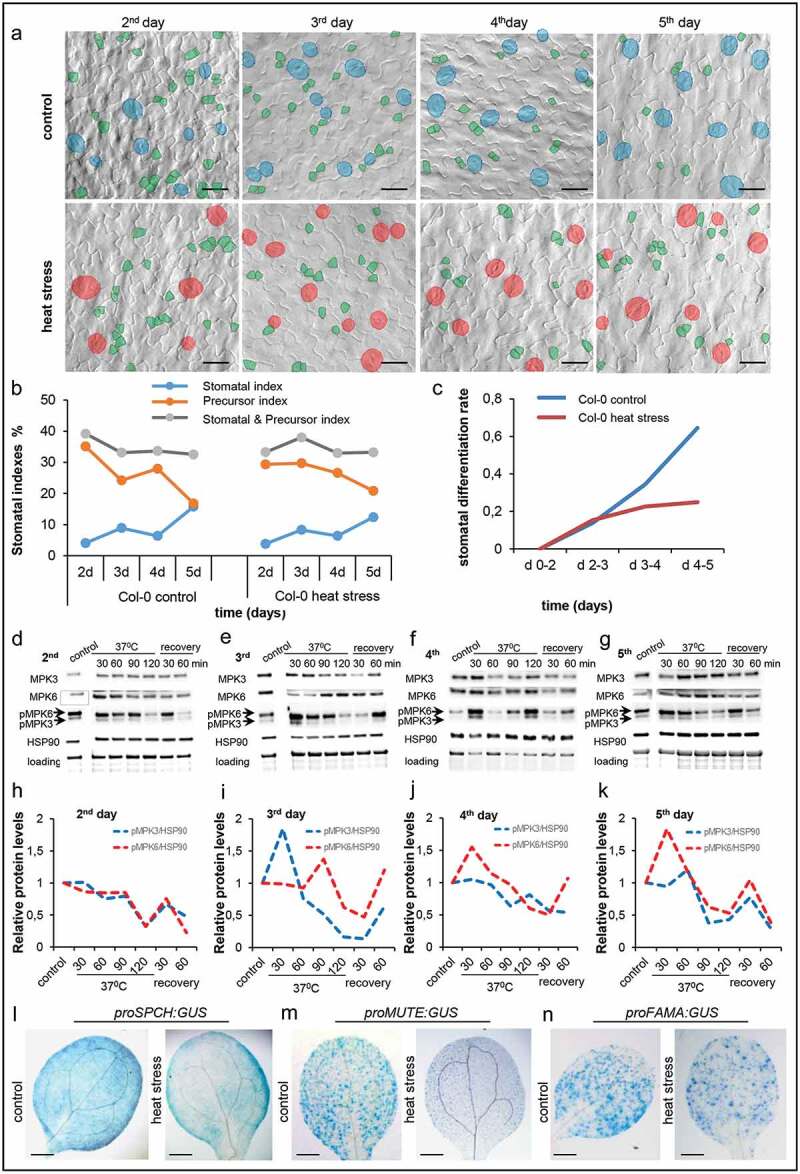

Since iterative cycles of heat stress starting at the 2nd day of development decreases stomatal density,16 we followed stomatal formation in the wild-type (Col-0) plants up to the 5th day of cotyledon development and we measured stomatal and precursor (meristemoids and guard mother cells) indexes under normal and heat stress conditions (Figure 1a,b). Whereas there was a similar gradual increase of the stomatal index both in control and heat stress conditions up to the 3rd day, we observed lower stomatal indexes in treated seedlings on the 5th day (Figure 1b). In control conditions, the precursor indexes were negatively correlated to the stomatal indexes (Figure 1b), while under stress conditions the precursor indexes were almost stable up to the 4th day and there was a small change on the 5th day (Figure 1b). Then, we calculated the relative stomatal differentiation rate in Col-0 under normal growth conditions and after heat stress treatment (by dividing the difference to the stomatal number at two successive time-points with the number of precursors in the first time-point). Our analysis revealed deceleration of stomatal differentiation after acute heat stress application (Figure 1c), correlating with lower stomatal formation. YODA-HSP90 module has been implicated in the activation of MPK6 through phosphorylation and inactivation of SPCH, the master transcription factor controlling stomatal development under acute heat stress.16,17 In this context, we performed time-course analysis of the protein levels of HSP90, MPK3,PK6, and their phosphorylated forms (pMPK3 and pMPK6) on the 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th day in heat stress treated seedlings (Figure 1d-g). Quantification of the relative MPK3 and MPK6 phosphorylation levels (MPK protein levels x pMPK protein levels) normalized to the HSP90 protein levels revealed a gradual activation of MPK3 and MPK6 during the course of heat stress treatment in the successive days of stress application (Figure 1h-k), suggesting subsequent inactivation of SPCH. Notably, MPK3 and MPK6 activation through phosphorylation was different in the time period between the 3rd and 5th day of the treatment (Figure 1e-k). On the 3rd day, the pMPK3 level was higher in comparison top MPK6, while on the 4th day, we observed a shift, since pMPK6 level was higher thanp MPK3 (figure 1f,j). The activation of MPK6 was further enhanced on the 5th day, while the phosphorylation of MPK3 was not affected by heat stress treatment on the same day (Figure 1g,k). These findings suggest partially overlapping, but also diverse roles of MPK3 and MPK6 in stomatal development.

Figure 1.

Heat stress alters the differentiation rate of stomata in wild-type plants. (a) Col-0 abaxial cotyledon epidermis images of heat stress treated and untreated plants at the indicated days. Stomata and precursors are artificially colored for better visualization. (b) Quantification of stomatal index, precursor index and stomatal and precursor index in heat stress treated and untreated Col-0 plants. (c) Stomatal differentiation rates in Col-0 seedlings growing in control conditions or after heat stress treatment. The presented values are the mean ±SE of ten cotyledons at the indicated time-points (d 2–d 5). The stomatal differentiation rate is the difference between the numbers of stomata at two consecutive time-points, relative to the number of precursors at the first time-point in a defined area. (d-g) Western blot analysis of MPK3, MPK6, pMPK3, pMPK6and HSP90 at the indicated days of heat stress treatment. (h-k) Time-course analysis of relative protein levels in the indicated days of heat stress treatment. The presented values are the mean ±SE of three technical repetitions at the indicated time-points (2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th day). (j-l) Expression pattern of proSPCH:GUS (l), proMUTE:GUS (m) and proFAMA:GUS (n) in 5 day-old cotyledons under normal and heat stress conditions. Scale bars: 20 μm (a), 500 μm (l-n).

Stomatal differentiation depends on the sequential function of three master transcription factors, SPCH, MUTE, and FAMA,3 which are expressed transiently in a respective developmental window and define specific stages of stomatal differentiation. Therefore, we tested the effect of acute heat stress on the transcriptional activation of SPCH, MUTE, and FAMA in 5 day-old cotyledons by using transgenic lines carrying proSPCH:GUS, proMUTE:GUS and proFAMA:GUS constructs. Our analysis showed that heat stress decreased the expression of SPCH and MUTE corroborating previous findings,16 while no significant change was observed in the FAMA expression (Figure 1l-n).

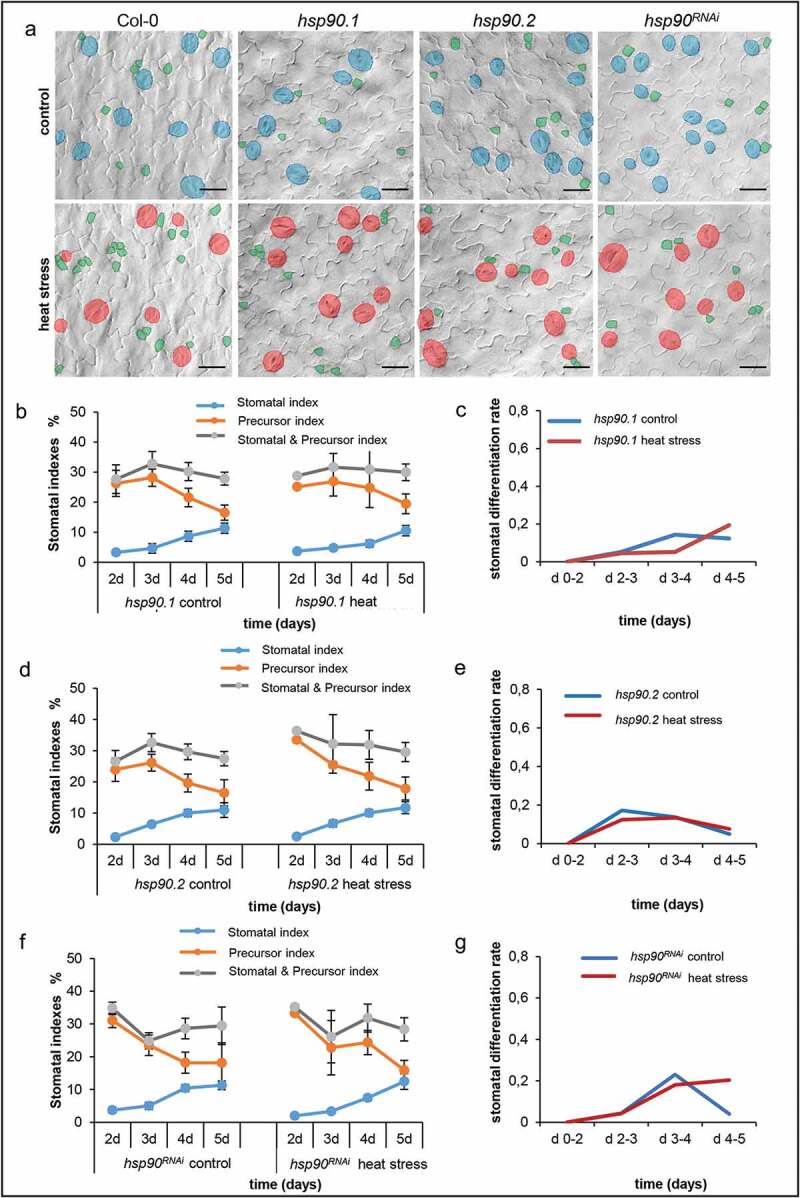

Next, we analyzed the stomatal and precursor formation and indexes along with stomatal differentiation rates in hsp90.1, hsp90.2 and hsp90RNAi mutants under normal growth conditions and upon acute heat stress treatment (Figure 2). All hsp90 mutants displayed lower stomatal differentiation rates compared to wild type under control growth conditions, as the differentiation rate in hsp90 mutants was around 0.2 in all the tested days, while in wild type exceeded 0.2 after the 2nd day reaching the value of 0.65 on the 5th day (Figures 2a,c,e,g, and 1c). Heat stress treatment did not affect the stomatal differentiation rate in hsp90.1 and hsp90.2 knockout mutants (Figure 2c,e), while it accelerated stomatal differentiation after the 3rd day in hsp90RNAi genetic background (Figure 2g). These findings corroborate reported data showing reduced sensitivity of hsp90 mutants concerning stomatal development under acute heat stress conditions due to the impaired activation of YODA signaling cascade, which impacts MPK3 and MPK6 phosphorylation.16 The impaired activation of MPK3 and MPK6 ultimately leads to deregulated phosphorylation and inactivation of downstream targets, like SPCH.16,17 It was previously shown that heat stress had no significant impact on the expression of MUTE in hsp90 mutants, which can be also related to the insensitivity of hsp90 mutants to elevated temperatures regarding stomata formation.16

Figure 2.

Genetic depletion of HSP90 affects the differentiation rate of stomata under normal and heat stress conditions. (a) Representative images of 5 day-old cotyledons from heat stress treated and untreated plants of Col-0 and indicated hsp90 mutants. Stomata and precursors are artificially colored for better visualization. (b) Quantification of stomatal index, precursor index and stomatal and precursor index in heat stress treated and non-treated hsp90.1 seedlings. (c) Stomatal differentiation rates in hsp90.1 seedlings growing in control conditions or after heat stress treatment. (d) Quantification of stomatal index, precursor index and stomatal and precursor index in heat stress treated and non-treated hsp90.2 seedlings. (e) Stomatal differentiation rates in hsp90.2 seedlings growing in control conditions or after heat stress treatment. (f) Quantification of stomatal index, precursor index and stomatal and precursor index in heat stress treated and non-treated hsp90RNAi seedlings. (g) Stomatal differentiation rates in hsp90RNAi seedlings growing in control conditions or after heat stress treatment. The presented values are the mean ±SE of ten cotyledons at the indicated time-points (d 2–d 5). The stomatal differentiation rate is the difference between the numbers of stomata at two consecutive time-points, relative to the number of precursors at the first time-point in a defined area. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Taken together, our study shows that heat stress decelerates the stomatal differentiation rate resulting in decreased formation of mature stomata in wild-type plants. This developmental response is closely related to the gradual phosphorylation and activation of MPK3 and MPK6, which is mediated by HSP90 molecular chaperones. Heat stress has an impact on the phosphorylation and inactivation of SPCH,16 the transcription factor driving the entry, spacing, and amplifying asymmetric divisions regulating cell fate and patterning.18 Our results showed that heat stress also affects the expression of MUTE, the positive regulator of stomatal differentiation, which stabilizes the transition to the differentiation program by orchestrating the transcriptional network controlling the symmetric divisions, which result in stomata composed by paired guard cells.19 Genetic depletion of HSP90s negatively regulates stomatal differentiation under normal growth conditions, which is not altered under elevated temperatures, suggesting that the progression of stomatal cell lineage requires functional HSP90s.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Keiko Torii for kindly providing proSPCH:GUS, proMUTE:GUS and proFAMA:GUS expressing lines.

Funding Statement

This work has been supported by Czech Science Foundation GAČR (project No. 17-24500S) and by ERDF project “Plants as a tool for sustainable global development” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000827).

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Hetherington AM, Woodward FI.. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:1–5. PMID:12931178. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zoulias N, Harrison EL, Casson SA, Gray JE.. Molecular control of stomatal development. Biochem J. 2018;475:441–454. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gray JE. Plant development: three steps for stomata. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R213–R215. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pillitteri LJ, Sloan DB, Bogenschutz NL, Torii KU. Termination of asymmetric cell division and differentiation of stomata. Nature. 2007;445:501–505. PMID:17183267. doi: 10.1038/nature05467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang H, Ngwenyama N, Liu Y, Walker JC, Zhang S. Stomatal development and patterning are regulated by environmentally responsive mitogen-activated protein kinases in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:63–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush SM, Krysan PJ. Mutational evidence that the Arabidopsis MAP kinase MPK6 is involved in anther, inflorescence, and embryo development. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:2181–2191. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komis G, Šamajová O, Ovečka M, Šamaj J. Cell and developmental biology of plant mitogen-activated protein kinases. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69:237–265. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taipale M, Jarosz DF, Lindquist S. HSP90 at the hub of protein homeostasis: emerging mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:515–528. PMID:20531426. doi: 10.1038/nrm2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. HSP90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. PMID:12050657. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samakovli D, Thanou A, Valmas C, Hatzopoulos P. HSP90 canalizes developmental perturbation. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:3513–3524. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samakovli D, Margaritopoulou T, Prassinos C, Milioni D, Hatzopoulos P. Brassinosteroid nuclear signaling recruits HSP90 activity. New Phytol. 2014;203:743–757. doi: 10.1111/nph.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samakovli D, Roka L, Plitsi PK, Kaltsa I, Daras G, Milioni D, Hatzopoulos, P. Active BR signaling adjusts the subcellular localization of BES1/HSP90 complex formation. Plant Biol. 2019. doi: 10.1111/plb.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jarosz DF, Taipale M, Lindquist S. Protein homeostasis and the phenotypic manifestation of genetic diversity: principles and mechanisms. Annu Rev Genet. 2010;44:189–216. PMID:21047258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margaritopoulou T, Kryovrysanaki N, Megkoula P, Prassinos C, Samakovli D, Milioni D, Hatzopoulos P. HSP90 canonical content organizes a molecular scaffold mechanism to progress flowering. Plant J. 2016;87:174–187. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tichá T, Samakovli D, Kuchařová A, Vavrdová T, Šamaj J. Multifaceted roles of HEAT SHOCK PROTEIN 90 molecular chaperones in plant development. J Exp Bot. 2020. published online Apr 2020. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samakovli D, Tichá T, Vavrdová T, Ovečka M, Luptovčiak I, Zapletalová V, Kuchařová A, Křenek P, Krasylenko Y, Margaritopoulou T, et al. YODA-HSP90 module regulates phosphorylation-dependent inactivation of SPEECHLESS to control stomatal development under acute heat stress in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2020;13:612–633. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putarjunan A, Torii KU. Heat shocking the jedi master: HSP90’s role in regulating stomatal cell fate. Mol Plant. 2020;13:536–538. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vatèn A, Soyars CL, Tarr PT, Nimchuk ZL, Bergmann DC. Modulation of asymmetric division diversity through cytokinin and SPEECHLESS regulatory interactions in the arabidopsis stomatal lineage. Dev Cell. 2018;47:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han SK, Qi X, Sugihara K, Dang JH, Endo TA, Miller KL, Kim ED, Miura T, Torii KU. MUTE directly orchestrates cell-state switch and the single symmetric division to create stomata. Dev Cell. 2018;45:303–315. 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]