ABSTRACT

Plant epidermal cuticles are composed of hydrophobic lipids that provide a barrier to non-stomatal water loss, and arose in land plants as an adaptation to the dry terrestrial environment. The expanding maize adult leaf displays a dynamic, proximodistal gradient of cuticle development, from the leaf base to the tip. Recently, our gene co-expression network analyses together with reverse genetic analyses suggested a previously undescribed function for PHYTOCHROME-mediated light signaling during cuticular wax deposition. The present work extends these findings by identifying a role for a specific LIPID TRANSFER PROTEIN (LTP) in cuticle development, and validating it via transgenic experiments in Arabidopsis. Given that LTPs and cuticles both evolved in land plants and are absent from aquatic green algae, we propose that during plant evolution, LTPs arose as one of the innovations of land plants that enabled development of the cuticle.

KEYWORDS: Maize, PHYTOCHROME, LIPD TRANSFER PROTEIN, cuticle, leaf, epidermis

Results and discussion

Cuticles form a hydrophobic lipid layer enclosing the aboveground parts of land plants, reducing water loss from the epidermis.1-5 Biochemically, cuticles are composed of wax and cutin. Waxes are nonpolar long-chain molecules, including alkanes, alkenes, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and wax esters, whereas cutins comprise polymerized matrices of hydroxy fatty acids, connected by ester bonds.6-8

Previously unknown functions for PHYTOCHROME-mediated light signaling during cuticle development were recently described in maize leaves.9 Specifically, Qiao and colleagues observed significant changes in the fatty acid and hydrocarbon composition of cuticular waxes extracted from phyb1 phyb2 double mutants.9 However, PHYTOCHROMES had not been hypothesized to functionally alter cuticle biosynthesis or lipid transport. In this study, we used transcriptomics to compare the gene expression patterns in phyb1 phyb2 double mutants and their wild-type siblings.

RNAseq was performed on light/dark-treated leaves from wild-type and phyb1 phyb2 mutant maize plants. In this experiment, plants were dissected to fully expose the partially-expanded maize leaf eight, the first adult leaf on the plant. The basal 2–8 cm of these leaves, which were previously light-shielded within in the leaf whorl, were sampled for RNAseq analyses after three different treatment regimens:1 immediately after dissection, and following six hour-long exposure to either2 light or3 dark conditions.

Three criteria were used to enhance the identification of transcripts that respond to PHYB-mediated light signaling. These included: 1) genes differentially-expressed in wild-type plants when compared to mutants, immediately after dissection and after 6 hour light exposure; 2) genes differentially-expressed upon light exposure in wild-type plants, but not differentially-expressed in phyb1 phyb2 double mutants; and 3) genes that showed significant interaction between the genotype and light/dark treatment in a two-way ANOVA. Only three genes remained following this strict filtering regimen (GRMZM2G107499, GRMZM5G835629, GRMZM2G040689). GRMZM2G107499 is predicted to encode a gene product that is homologous to the Arabidopsis LNK1 protein, 10 which functions to integrate light signaling and the circadian clock.11 GRMZM5G835629 is predicted to encode a protein kinase-homolog, whereas GRMZM2G040689 is homologous to an Arabidopsis BIFUNCTIONAL INHIBITOR/LTP gene.10 Only the putative maize LTP gene, GRMZM2G040689, was epidermally expressed. No functional analyses have been performed previously on the putative Arabidopsis ortholog (AT2G10940; Gramene http://www.gramene.org) of this predicted maize LTP gene. To investigate the potential function of this predicted maize LTP during cuticle biogenesis, we first over-expressed GRMZM2G040689, tagged with the fluorescent marker GFP, in Arabidopsis under the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus (CaMV) 35 S constitutive promoter (eleven total transgenic events were recovered). Driven by a ubiquitous promoter, fluorescence microscopy of all eleven transgenic events revealed that the LTP~GFP fusion protein accumulates in the plasma membrane/cell wall of epidermal cells (Figure 1), which is the site of cuticle component biosynthesis and translocation.

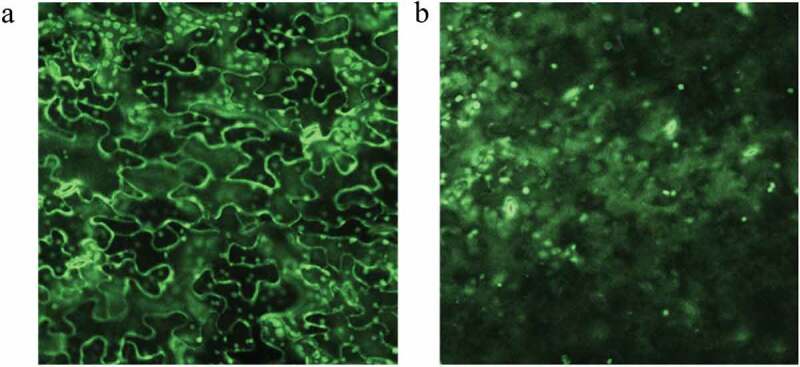

Figure 1.

Overexpression of the maize LTP gene GRMZM2G040689 in Arabidopsis (a) Confocal imaging reveals the accumulation of the ZmLTP~GFP fusion protein in the epidermal cell plasma membrane/cell wall, which is not identified in non-transgenic wild-type plants (b). The bright green signal observed in the cellular interior in both (A) and (B) is chloroplast autofluorescence.

Moreover, gas chromatography–mass spectometry (GC-MS) analyses of cuticle lipids extracted from the leaf surfaces of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing the heterologous ZmLTP~GFP construct show alterations in the abundance of several cuticular wax components as compared to wild type controls (Figure 2). Total levels of primary alcohols and alkanes were higher in 35 S:LTP~GFP plants (Figure 2a), which included analyses of four separate transgenic events. Specifically, C27, C31 and C33 alkanes (Figure 2b), C26 and C28 primary alcohols (Figure 2c), and C41 and C46 wax esters (Figure 2d) were all significantly more abundant in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing this maize LTP gene.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of the maize LTP gene GRMZM2G040689 alters the cuticle composition of Arabidopsis leaves. GC-MS analyses of (a) total waxes, (b) alkanes, (c) primary alcohols, and (d) wax esters in Arabidopsis leaves. Values are means from four independent transformants ± SE. Asterisks indicate significant differences with wild type between samples in unpaired t tests. PA, primary fatty alcohol; FFA, free fatty acid; ALK, alkanes; AL, aldehyde; WE, wax ester; ALIC, alicyclics. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Taken together, these data suggest that the maize LTP gene GRMZM2G040689 affects cuticle composition in Arabidopsis leaves. We note that the changes in cuticle development after overexpression of this maize LTP in Arabidopsis leaves do not negatively correlate with the changes observed in maize phyb1 phyb2 mutant cuticles, 9 which under-express GRMZM2G040689 as compared to wild type leaves. However, we also recognize that the Arabidopsis leaf is a heterologous system, with a very different cuticle composition than maize leaves.

PHYTOCHROMES are found in all green plants including algae,12,13 although cuticles and LTPs are an evolutionary innovation of land plants.2,4,14-18 Although light signaling-associated changes in lipid biosynthesis are present in the green algae ancestors of land plants,19,20 these light-induced lipids are not utilized to form a cuticle in algae. The evolutionary innovation of the cuticle coincided with the appearance of LTP proteins and other components of the cuticle biosynthesis machinery, which are absent from algae and present in all land plants. Light activates the expression of genes involved in biosynthesis of plant cuticles.21-24 Our recent analyses in bryophyte mosses and angiosperm grasses suggested that cuticle development in land plants is regulated by PHYTOCHROME-mediated light signaling, 9 whereas this current study suggests that PHYTOCHROME signaling activates expression of a specific maize LTP. We propose that light-induced, PHY-mediated activation of LTP expression may have arisen as a critical step enabling cuticle development during the evolution of land plants.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation #1444507.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Kerstiens G. Water transport in plant cuticles: an update. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(11):1–3. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bateman RM, Crane PR, DiMichele WA, Kenrick PR, Rowe NP, Speck T, Stein WE.. Early evolution of land plants: phylogeny, physiology, and ecology of the primary terrestrial radiation. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1998;29(1):263–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jetter R, Riederer M.. Localization of the transpiration barrier in the epi- and intracuticular waxes of eight plant species: water transport resistances are associated with fatty acyl rather than alicyclic components. Plant Physiol. 2016;170(2):921–934. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenrick P, Crane PR. The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature. 1997;389(6646):33. doi: 10.1038/37918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raven JA, Edwards D. Physiological evolution of lower embryophytes: adaptations to the terrestrial environment. In Hemsley AR, Poole I, Editors. The Evolution of Plant Physiology. Linnean Society Symposium Series, Elsevier Academic Press; 2004. p.17–41. (Elsevier). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolattukudy PE. Polyesters in higher plants. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2001;71:1–49. doi: 10.1007/3-540-40021-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nawrath C. The biopolymers cutin and suberin. Arabidopsis Book. 2002;1:e0021. doi: 10.1199/tab.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yeats TH, Rose JK. The formation and function of plant cuticles. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(1):5–20. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.222737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiao P, Bourgault R, Mohammadi M, Matschi S, Philippe G, Smith LG, Gore MA, Molina I, Scanlon MJ. Transcriptomic network analyses shed light on the regulation of cuticle development in maize leaves. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(22):12464–12471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004945117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Portwood J, Woodhouse MR, Cannon EK, Gardiner JM, Harper LC, Schaeffer ML, Walsh JR, Sen TZ, Cho KT, Schott DA, et al. MaizeGDB 2018: the maize multi-genome genetics and genomics database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;47:1146–1154. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rugnone ML, Faigon Soverna A, Sanchez SE, Schlaen RG, Hernando CE, Seymour DK, Mancini E, Chernomoretz A, Weigel D, Más P, et al. LNK genes integrate light and clock signaling networks at the core of the Arabidopsis oscillator. PNAS. 2013;110(29):12120–12125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302170110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duanmu D, Bachy C, Sudek S, Wong C-H, Jimenez V, Rockwell NC, Martin SS, Ngan CY, Reistetter EN, van Baren MJ, et al. Marine algae and land plants share conserved phytochrome signaling systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(44):15827–15832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416751111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li FW, Melkonian M, Rothfels CJ, Villarreal JC, Stevenson DW, Graham SW, Wong GKS, Pryer KM, Mathews S. Phytochrome diversity in green plants and the origin of canonical plant phytochromes. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7852. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salminen TA, Eklund DM, Joly V, Blomqvist K, Matton DP, Edqvist J. Deciphering the evolution and development of the cuticle by studying lipid transfer proteins in mosses and liverworts. Plants (Basel). 2018;7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salminen TA, Blomqvist K, Edqvist J. Lipid transfer proteins: classification, nomenclature, structure, and function. Planta. 2016;244(5):971–997. doi: 10.1007/s00425-016-2585-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Finkina EI, Melnikova DN, Bogdanov IV, Ovchinnikova TV. Lipid transfer proteins as components of the plant innate immune system: structure, functions, and applications. Acta Naturae. 2016;8(2):47–61. doi: 10.32607/20758251-2016-8-2-47-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edstam MM, Viitanen L, Salminen TA, Edqvist J. Evolutionary history of the non-specific lipid transfer proteins. Mol Plant. 2011;4(6):947–964. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssr019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edqvist J, Blomqvist K, Nieuwland J, Salminen TA. Plant lipid transfer proteins: are we finally closing in on the roles of these enigmatic proteins? J Lipid Res. 2018;59(8):1374–1382. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R083139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorigue D, Légeret B, Cuiné S, Blangy S, Moulin S, Billon E, Richaud P, Brugière S, Couté Y, Nurizzo D, et al. An algal photoenzyme converts fatty acids to hydrocarbons. Science. 2017;357(6354):903–907. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sorigue D, Légeret B, Cuiné S, Morales P, Mirabella B, Guédeney G, Li-Beisson Y, Jetter R, Peltier G, Beisson F, et al. Microalgae synthesize hydrocarbons from long-chain fatty acids via a light-dependent pathway. Plant Physiol. 2016;171(4):2393–2405. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhee Y, Hlousek-Radojcic A, Ponsamuel J, Liu D, Post-Beittenmiller D. Epicuticular wax accumulation and fatty acid elongation activities are induced during leaf development of leeks. Plant Physiol. 1998;116(3):901–911. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joubès J, Raffaele S, Bourdenx B, Garcia C, Laroche-Traineau J, Moreau P, Domergue F, Lessire R. The VLCFA elongase gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana: phylogenetic analysis, 3D modelling and expression profiling. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;67:547–566. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooker TS, Millar AA, Kunst L. Significance of the expression of the CER6 condensing enzyme for cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1568–1580. doi: 10.1104/pp.003707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh MC, Go YS. DEWAX-mediated transcriptional repression of cuticular wax biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal Behav. 2014;9:e29463. doi: 10.4161/psb.29463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]