Abstract

We applied infrequent-restriction-site PCR (IRS-PCR) to the investigation of an outbreak caused by 23 isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit from November 1996 to May 1997 and a pseudoepidemic caused by 16 isolates of Serratia marcescens in a delivery room from May to September 1996. In the epidemiologic investigation of the outbreak caused by A. baumannii, environmental sampling and screening of all health care workers revealed the same species from the Y piece of a mechanical ventilator and the hands of two health care personnel. IRS-PCR showed that all outbreak-related strains were genotypically identical and that three strains from surveillance cultures were also identical to the outbreak-related strains. In a pseudoepidemic caused by S. marcescens, IRS-PCR identified two different genotypes, and among them one genotype was predominant (15 of 16 [93.8%] isolates). Extensive surveillance failed to find any source of S. marcescens. Validation of the result of IRS-PCR by comparison with that of field inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE) showed that they were completely concordant. These results suggest that IRS-PCR is comparable to FIGE for molecular epidemiologic studies. In addition, IRS-PCR was less laborious and less time-consuming than FIGE. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the application of IRS-PCR to A. baumannii and S. marcescens.

Recently, a new typing method called infrequent-restriction-site PCR (IRS-PCR) has been proposed by Mazurek et al. (8). The main strategy of this method is the selective amplification of DNA sequences located between a frequently occurring restriction site and an infrequently occurring restriction site by using adaptors and primers based on these two enzymes. It has a discriminatory power comparable to that of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). It is less tedious and less laborious than PFGE. Although IRS-PCR has not yet been applied to many species of organisms (10), we think that it can be a potentially universal tool for molecular epidemiologic analysis of outbreak.

In this study, we applied this IRS-PCR technique to the investigation of an outbreak caused by Acinetobacter baumannii and a pseudoepidemic caused by Serratia marcescens for the purpose of assessing its usefulness in molecular epidemiology. We also performed field inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE), a type of PFGE, and compared the genotypes obtained by FIGE with those obtained by IRS-PCR.

(Part of this study was presented at the 38th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 24 to 27 September 1998, San Diego, Calif.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A cluster of isolation of S. marcescens.

From May to September 1996, we found that 16 clinical isolates of S. marcescens had been recovered on the obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN) ward. In order to determine whether the event was a true outbreak, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who yielded S. marcescens during that time, including those outside the OB/GYN ward. Concurrently, we also performed extensive surveillance by obtaining samples from the OB/GYN ward for culture. Samples were obtained from inanimate sources and the hands of health care personnel. The species identification of S. marcescens was confirmed by the API 20E profile (bioMéurieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Another eight strains of S. marcescens isolated outside the OB/GYN ward during the same period were included as epidemiologically unrelated controls in this study.

Outbreak of A. baumannii.

In February 1997, we recognized a cluster of isolations of A. baumannii in the intensive care unit (ICU). Since that time, we retrospectively investigated any additional isolation of A. baumannii in the ICU and found that the isolation of A. baumannii in the ICU began on November 1996. We performed surveillance cultures three times (March 1997, April 1997, and July 1997). We obtained samples from environmental sources (e.g., Y pieces of a mechanical ventilator, fluid in the humidifier jar, water in a vaporizer, floor, tap water supply system, soap, and disinfectant solution) and the hands of health care personnel in the ICU. The medical records of patients in the ICU from November 1996 to March 1997 were retrospectively reviewed, and a prospective survey of any further isolation of A. baumannii was also done. Further clinical isolates of A. baumannii were recovered until May 1997. The species identification of A. baumannii was confirmed by the API 20NE profile (bioMéurieux). Two epidemiologically unrelated strains were included as controls in this study.

IRS-PCR.

IRS-PCR was performed as described previously by Mazurek et al. (8), with some modification. In brief, the HhaI adaptor (AH), which consists of a 22-base oligonucleotide (AH1; 5′-AGA ACT GAC CTC GAC TCG CAC G-3′) with a 7-base oligonucleotide (AH2; 5′-TGC GAG T-3′), was annealed to bases 14 through 20 from the 5′ end leaving a CG-3′ overhang. AH1 and AH2 were mixed in equal molar amounts (10 pmol/μl each). They were annealed as the mixture cooled from 80 to 4°C over 1 h. The mixture was briefly centrifuged and was stored at −20°C until use. The XbaI adaptor (AX), which consisted of a phosphorylated 18-base oligonucleotide (AX1; 5′-PO4-CTA GTA CTG GCA GAC TCT-3′) with a 7-base oligonucleotide (AX2; 5′-GCC AGT A-3′) was annealed to bases 5 through 11 from the 5′ end leaving a 5′-CTAG overhang. AX1 was phosphorylated by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) for 1 h at 37°C. AX1 and AX2 were mixed and were annealed under the same condition used for AH. Chromosomal DNAs of clinical isolates of S. marcescens and A. baumannii were isolated by using a QIAamp tissue kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). The isolated DNAs were digested with HhaI and XbaI for 1 h at 37°C. They were then ligated to AH and AX by using the Rapid DNA ligation kit (Boehringer Mannheim) and were digested again with the same restriction enzymes in order to cleave any restriction sites reformed by ligation. In the amplification procedure, AH1 and PX (5′-AGA GTC TGC CAG TAC TAG A-3′) were used as primers. PX is complementary to AX and has one base left on the 3′ end of the native DNA following XbaI digestion. Amplification was performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer, Branchburg, N.J.) with an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min and then 30 cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C, and extension at 72°C for 1.5 min. The PCR products were separated on a polyacrylamide gel (6.5% T [total monomer concentration], 2.7% C [cross-linker concentration]) in 0.5 × TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer at a constant voltage of 100 for 3 h. Then, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and was photographed with UV illumination.

FIGE.

FIGE was conducted as described previously (2). XbaI and SpeI (3) were used as restriction enzymes for A. baumannii and S. marcescens, respectively. The settings for FIGE were as follows: initial runing time, 10 min; switch interval, 1 to 25 s; forward to reverse ratio, 3:1; temperature of running solution, 14°C; and total running time, 18 h. Interpretation of the results of FIGE was based on the guidelines proposed by Tenover et al. (12).

RESULTS

Clinical relevance of patients yielding S. marcescens and the results of molecular typing.

As Table 1 shows, 15 of 16 strains (94%) were isolated from women with full-term or preterm labor; one strain (strain 9583) was from a patient with uterine myoma. Among these patients there was no significant evidence of infectious disease directly related to S. marcescens except in one patient with chorioamnionitis (strain 9870), which was probably acquired prior to hospitalization. Most strains were isolated from cervical mucus, while one strain (strain 9685) was isolated from blood. However, the patient did not show any manifestation of sepsis, suggesting that it was pseudobacteremia.

TABLE 1.

Clinical isolates of S. marcescens and results of IRS-PCR and FIGE

| Strain group and no. | Specimen | Underlying condition | Outcome | Type by IRS-PCR | Type by FIGE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical strains (n = 16) | |||||

| 9563 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9561 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9565 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9570 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9583 | Cervical mucus | Uterine myoma | Cured and discharged | I | A |

| 9685 | Blood | Preterm labor | Cured and discharged | I | A |

| 9662 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9683 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9717 | Cervical mucus | Placenta previa | Cured and discharged | I | A |

| 9760 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9803 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9823 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9833 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9858 | Cervical mucus | Normal labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9857 | Cervical mucus | Preterm labor | Discharged | I | A |

| 9870 | Cervical mucus | Chorioamnionitis | Termination of labor and discharged | II | B |

| Epidemiologically unrelated strains (n = 8) | |||||

| 9623 | Pus from wound | Chronic osteomyelitis | Cured and discharged | III | C |

| 9636 | Pus from wound | Chronic osteomyelitis | Cured and discharged | IV | D |

| 9634 | Blood | Liver cirrhosis | Died due to sepsis | V | E |

| 9635 | Pus from wound | Surgical wound infection | Cured and discharged | VI | F |

| 9645 | Sputum | Hydrocephalus pneumonia | Cured and discharged | VII | G |

| 9654 | Sputum | Cerebral infarction | Cured and discharged | VIII | H |

| 9736 | Sputum | Pneumonia | Cured and discharged | IX | I |

| 9845 | Gastric juice | Healthy baby | Discharged | X | J |

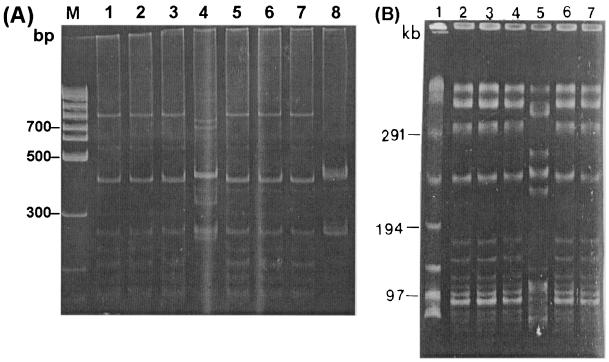

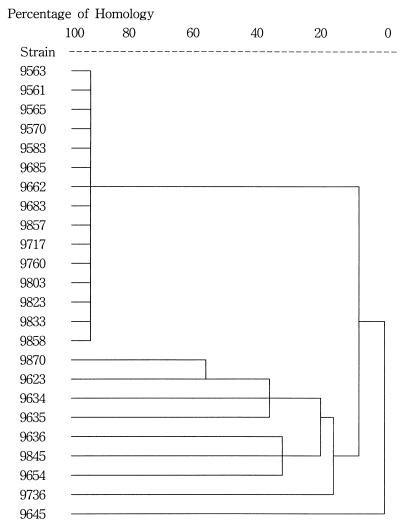

IRS-PCR yielded one predominant genotype among 15 of 16 (93.7%) isolates from the OB/GYN ward, while 1 strain (strain 9870) from a patient with chorioamnionitis showed a distinct pattern (Fig. 1A). The genotypes detected by FIGE were completely concordant with those detected by IRS-PCR (Fig. 1B and Table 1). It took about 4 days to complete FIGE, whereas IRS-PCR was finished within a day. All the strains outside the OB/GYN ward were of different genotypes compared with the predominant genotype in the ward (Fig. 2), and thus, we thought that the cluster of S. marcescens strains from a single clone was localized to one ward. However, as no patient had an infection with any clinical relevance to the true infectious disease, we concluded that it was a pseudoepidemic or nothing but a colonization rather than a true outbreak.

FIG. 1.

(A) Representative results of IRS-PCR for S. marcescens. Lane 1, molecular weight marker; lanes 2 to 7, strains from the OB/GYN ward (lane 2, strain 9803; lane 3, strain 9823; lane 4, strain 9685; lane 5, strain 9870; lane 6, strain 9857; lane 7, strain 9858). (B) Representative result of FIGE with SpeI for S. marcescens. Lane 1, molecular size marker, lanes 2 to 7, strains from the OB/GYN ward (the strains in each lane are as described for panel A.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram by cluster analysis of the band patterns produced by IRS-PCR of S. marcescens. Fifteen of 16 isolates in the OB/GYN ward (strains 9563 to 9858) had a single pattern. One strain from the OB/GYN ward (strain 9870) and those from the other wards (strains 9623 to 9645) had distinct patterns.

Outbreak of A. baumannii infection and results of molecular typing and surveillance study.

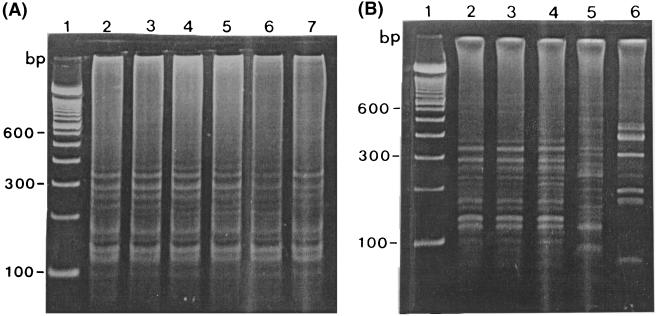

As indicated in Table 2, more than a half of the A. baumannii strains (52%; 12 of 23) were isolated from sputum. Five strains were recovered from pus, and two were recovered from blood. On the basis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definition of nosocomial infection, four strains (strains 4, 8, 18, and 20) were considered to be the cause of insignificant infections (6). Among 19 patients with significant infections, 13 patients died. Pneumonia and sepsis were the main causes of death in nine patients, while four patients died of noninfectious causes. Surveillance cultures revealed three strains of the same species from the Y piece of a mechanical ventilator, the hands of a doctor, and the hands of a nurse. IRS-PCR showed that all outbreak-related strains were genotypically identical (Fig. 3A) and that the strains from the surveillance cultures were also identical to the outbreak-related strain, while two epidemiologically unrelated strains showed different banding patterns (Fig. 3B).

TABLE 2.

Clinical isolates of A. baumannii

| Strain | Specimen | Underlying diseases | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sputum | Pneumonia | Improved |

| 2 | Blood | Cholangiocarcinoma and sepsis | Died due to sepsis |

| 3 | Blood | Pneumonia and sepsis | Died due to sepsis |

| 4a | Sputum | Chronic bronchitis | Died (not due to infection) |

| 5 | Sputum | Chronic renal failure and pneumonia | Died (due to pneumonia) |

| 6 | Sputum | Subdural hematoma and pneumonia | Died (due to pneumonia) |

| 7 | Pus from wound | Colon cancer and surgical wound infection | Improved |

| 8a | Pus from drain | Hepatocellular carcinoma, liver abscess | Improved |

| 9 | Urine | Urinary tract infection | Died due to sepsis |

| 10 | Sputum | Pneumonia | Improved |

| 11 | Sputum | Aortic aneurysm and pneumonia | Died (not due to infection) |

| 12 | Urine | Urinary tract infection | Improved |

| 13 | Sputum | Status asthmaticus and pneumonia | Died (not due to infection) |

| 14 | Catheter tip | Systemic lupus erythematosus and central venous site infection | Died due to sepsis |

| 15 | Pus from wound | Klatskin tumor | Died (not due to infection) |

| 16 | Sputum | Cerebral infarction and pneumonia | Died (related to pneumonia) |

| 17 | Pus from wound | Cervical spine fracture and surgical wound infection | Improved |

| 18a | Sputum | Cerebral infarction | Died (not due to infection) |

| 19 | Pus from wound | Ovarian cancer | Died (not due to infection) |

| 20a | Wound | Hepatocellular carcinoma | Improved |

| 21 | Sputum | Arterial occlusion and pneumonia | Improved |

| 22 | Sputum | Cerebral infarction and pneumonia | Died (due to pneumonia) |

| 23 | Sputum | Subarachnoid hemorrhage and pneumonia | Died (due to pneumonia) |

Insignificant infection.

FIG. 3.

Representative results of IRS-PCR for A. baumannii. (A) Lane 1, molecular size marker; lanes 2 to 7, clinical strains from the ICU. (B) Comparison with strains from the surveillance study and epidemiologically unrelated strains. Lane 1, molecular size marker; lane 2, a strain from the outbreak; lane 3, a strain from a hand of a member of the medical staff; lane 4, a strain from the Y piece of a mechanical ventilator; lanes 5 and 6, epidemiologically unrelated clinical strains.

DISCUSSION

In order to trace the nidus of the outbreak, many typing methods were used in the epidemiologic investigation. Typing methods based on phenotypic characteristics (e.g., antibiogram analysis, serotyping, or phage typing) had been used, but these methods were not sufficiently discriminatory. Nowadays, genotyping techniques based on DNA analysis are reliable for epidemiologic investigations. Various methods have been devised for the analysis of strains from outbreaks such as ribotyping, PFGE, and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) assay (1, 4–7, 9, 11, 14). Among these, PFGE has, until now, been the best tool for the analysis of most organisms in terms of discriminatory power and typeability. However, PFGE is too tedious and laborious. Typing methods that are based on nucleic acid amplification and that have been reported so far can be applicable to many organisms and can be done within a day, but they require information about the target DNA sequence for primers or they use arbitrary primers, and their results are easily affected by various experimental conditions (13). According to Mazurek et al. (8), IRS-PCR can be applied to a wide array of organisms by using identical enzymes, adapters, primers, and PCR conditions. The primers used in this technique are not arbitrary, and knowledge of a target sequence is not required. By using frequently and infrequently cutting enzymes, it produces a few bands for interpretation. It is less time-consuming and less laborious than PFGE or ribotyping. Hence, we think that it can be a more efficient alternative than any other typing methods ever developed.

In this study, we applied IRS-PCR to investigate clinical isolates of A. baumannii and S. marcescens. In the case of a pseudoepidemic caused by S. marcescens, the result of IRS-PCR showed one predominant genotype among 15 of 16 isolates. The banding patterns of IRS-PCR were completely concordant with those of FIGE, which suggested that IRS-PCR was as discriminatory as FIGE. It took, on average, 4 days to perform FIGE, while IRS-PCR was completed within a day. Although the surveillance study in the OB/GYN ward identified no organism and the cluster of isolation turned out to be not a true outbreak but a colonization or a pseudoepidemic, we thought that the organism originated from the ward and could be a potential pathogen in the near future. Therefore, we sterilized the ward and exchanged all instruments and equipment for new ones. Since then, S. marcescens has not been isolated.

In the outbreak caused by A. baumannii, IRS-PCR demonstrated that the genotypes of all outbreak-related strains were identical, which suggested that the outbreak originated from a single clone. As three strains isolated during the surveillance study also had genotypic patterns identical to those of the outbreak-related strains, we could determine that strains from either the Y piece of a mechanical ventilator or health care personnel hands were the primary source of the outbreak. On the basis of this investigation, we immediately exchanged all the facilities including ventilator equipment for new ones. We prohibited the doctor and the nurse who yielded genotypically identical A. baumannii from working in the ICU until conversion to a negative result on follow-up culture. Once a patient in the ICU was found to be infected with A. baumannii, we strictly isolated the patient. We also designated an exclusive nurse for each patient with A. baumannii infection in order to prevent person-to-person spread.

In conclusion, IRS-PCR can be a good alternative tool for molecular epidemiologic investigations because of its rapidity and discriminatory power, which are comparable to those of PFGE. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the application of IRS-PCR to clinical isolates of A. baumannii and S. marcescens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso R, Aucken H M, Perez-Diaz J C, Cookson B D, Baquero F, Pitt T L. Comparison of serotype, biotype and bacteriocin type with rDNA RFLP patterns for the type identification of Serratia marcescens. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:99–107. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birren B, Lai E. Switch interval and resolution in pulsed field gels. In: Birren B, Lai E, editors. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis: a practical guide. 1st ed. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bollman R, Halle E, Sokolowka-Kohler W, Gravel E L, Buchholz P, Klare I, Tschape H, Witte W. Nosocomial infections due to Serratia marcescens. Clinical findings, antibiotic susceptibility patterns and fine typing. Infection. 1989;17:294–300. doi: 10.1007/BF01650711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chetoui H, Delhalle E, Osterrieth P, Rousseaux D. Ribotyping for use in studying molecular epidemiology of Serratia marcescens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2637–2642. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2637-2642.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Debast S B, Melchers W J, Voss A, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A, Meis J F. Epidemiological survey of an outbreak of multiresistant Serratia marcescens by PCR-fingerprinting. Infection. 1995;23:267–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01716283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamer J S, Jarvis W R, Emori T G, Horan T C, Hughes J. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16:128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu P Y, Lau Y J, Hu B S, Shir J M, Cheung M H, Shi Z Y, Tsai W S. Use of PCR to study epidemiology of Serratia marcescens isolates in nosocomial infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1935–1938. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1935-1938.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazurek G H, Reddy V, Marston B J, Haas W H, Crawford J T. DNA fingerprinting by infrequent-restriction-site amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2386–2390. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2386-2390.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miranda G, Kelly C, Solorzano F, Leanos B, Coria R, Patterson J E. Use of pulsed field gel electrophoresis typing to study an outbreak of infection due to Serratia marcescens in a neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3138–3141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3138-3141.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riffard S, Presti F L, Vandenesch F, Forey F, Reyrolle M, Etienne J. Comparative analysis of infrequent-restriction-site PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for epidemiological typing of Legionella pneumophilla serogroup 1 strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:161–167. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.161-167.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi Z, Liu P Y, Lau Y J, Lin Y H, Hu B S. Use of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to investigate an outbreak of Serratia marcescens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:325–327. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.325-327.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tyler K D, Wang G, Tyler S D, Johnson W M. Factors affecting reliability and reproducibility of amplification-based DNA fingerprinting of representative bacterial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:339–346. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.2.339-346.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Belkum A, van Leeuwen W, Kluytmans J, Verbrugh H. Molecular nosocomial epidemiology: high speed typing of microbial pathogens by arbitrary primed polymerase chain reaction assays. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:658–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]