ABSTRACT

Objectives

To investigate the proportion of patients that present with isolated extremity pain who have a spinal source of symptoms and evaluate the response to spinal intervention.

Methods

Participants (n = 369) presenting with isolated extremity pain and who believed that their pain was not originating from their spine, were assessed using a Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy differentiation process. Numerical Pain Rating Scale, Upper Extremity/Lower Extremity Functional Index and the Orebro Questionnaire were collected at the initial visit and at discharge. Global Rating of Change outcomes were collected at discharge. Clinicians provided MDT ‘treatment as usual’. A chi-square test examined the overall significance of the comparison within each region. Effect sizes between spinal and extremity source groups were calculated for the outcome scores at discharge

Results

Overall, 43.5% of participants had a spinal source of symptoms. Effect sizes indicated that the spinal source group had improved outcomes at discharge for all outcomes compared to the extremity source group.

Discussion

Over 40% of patients with isolated extremity pain, who believed that their pain was not originating from the spine, responded to spinal intervention and thus were classified as having a spinal source of symptoms. These patients did significantly better than those whose extremity pain did not have a spinal source and were managed with local extremity interventions. The results suggest the spine is a common source of extremity pain and adequate screening is warranted to ensure the patients ´ source of symptoms is addressed.

KEYWORDS: Differentiation, extremity pain, mechanical diagnosis and therapy, McKenzie Method, repeated movements, musculoskeletal, directional preference, spinal source

Introduction

When a patient presents to a clinician with an apparent musculoskeletal problem, the clinician will aim to direct intervention at the body part they perceive to be the source of the patient’s problem. Hence, a basic requisite for the successful local management of extremity problems is that the symptoms are emanating from the extremity itself [1,2]. Clinicians interpret the patient’s history and examination to differentiate between a spinal source of symptoms and an extremity source. Even though this differentiation process is pivotal in guiding management, it is fraught with challenges [3–5]. If pain of spinal origin is interpreted incorrectly as a local extremity problem, it can initiate a cascade of poor decision making and inappropriate management [6–9].

The challenges of differentiating between the spinal and extremity source of pain are compounded by the high prevalence of incidental extremity imaging findings in the asymptomatic population [10–15]. This may be further clouded by the poor psychometric properties of many extremity orthopedic tests [16–20] and their propensity to be falsely positive in the presence of a spinal disorder [21]. Perhaps most critically, there is no documented process that has been adequately tested and sufficiently demonstrated to differentiate a spinal versus an extremity source of symptoms [9]. Indeed, many studies for extremity problems either make no mention of excluding the spine [22–26] or the process appears cursory and based on assumptions rather than evidence [9]. In some studies, observing spinal range of motion would appear to be the most extensive form of screening [27]. There is a ready acceptance that if there is pain elicited from extremity movement [28] or if there is reduced range of extremity motion [4] then the problem must reside either solely in the extremity or accompanying a separate spinal problem.

Isolated extremity pain of spinal origin has been acknowledged and described in the literature [6,7,29,30] though more frequently at more proximal locations, such as the shoulder, with a reported prevalence between 10% and 27% [30–32], and the hip with isolated cases reported [33,34]. Other joints such as the ankle and the wrist have no data on their spinal prevalence. Therefore, the literature is currently lacking in its comprehensiveness of reported prevalence data from different extremity joints to guide clinicians and researchers as to their expectations in excluding the spine when patients present with extremity symptoms.

Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (MDT) is a system of musculoskeletal assessment and classification that is commonly practiced throughout the world [35]. It has acceptable reliability in trained clinicians for classifying low back pain [36], and conflicting levels of reliability for classifying patients with neck and extremity pain [36,37]. MDT is a system that encompasses classifications which are characterized as producing only local pain or capable of producing referred pain and it has been used by clinicians in the differentiation of spinal and extremity symptoms [7,29]. The most common MDT classification which is capable of referring pain from the spine to the extremity is the Derangement classification [7,32]. Patients whose pain is due to a Derangement can experience rapid changes in their symptoms in response to different movements and loading strategies [32,35]. Most critically there is one direction of movement, known as ‘directional preference’, that patients can repeatedly move in and which will provide a lasting symptomatic and functional improvement [7,32,35]. The MDT spinal vs extremity differentiation process is based predominantly upon the symptomatic and mechanical response to repeated end-range movements rather than on imaging or solely pain location. The process for differentiation is centered around a ‘baseline-test-recheck baseline’ sequence where extremity baselines, including pain, range of motion or functional tasks are initially assessed. For example, active shoulder abduction. This is then followed by testing sets of spinal repeated movements e.g. repeated cervical retraction, and then rechecking significant baselines for change. Has the repeated cervical retraction exercise altered the active shoulder abduction in terms of pain intensity or range of movement? This process can be repeated with various spinal directions or loading strategies until the change in the extremity baselines is significant and conclusive or until it is confirmed that no change has occurred. It is hypothesized, that by avoiding some of the pitfalls of the current differentiation process, by not basing decisions upon imaging, or using tests with poor psychometric properties, clinicians may gain a more accurate gauge of which symptoms are coming from the spine and which are not.

The primary objective of this study was to establish the proportion of patients with extremity pain that responded to spinal intervention and thus are hypothesized to have a spinal source for their symptoms, using the MDT differentiation process. The secondary objective was to examine if these ‘spinal source’ extremity problems managed with MDT spinal intervention respond more or less favorably compared to extremity problems where the spine is not deemed to be the source.

Methods

Study design

This study was a prospective cohort study including two clinical sites in Canada (both occupational health physiotherapy for hospital employees), one in New Zealand (outpatient orthopedic and sports clinic) and one in the United States of America (outpatient orthopedic and sports clinic). This study was carried out from January 2017 to April 2018. Ethics approval was obtained from Western University Health Science Research Ethics Board, London, Canada, from the New Zealand Ethics Committee and from Pacific University Oregon Institutional Review Board.

Study participants

Consecutive participants with pain in the extremities, presenting to physiotherapy practice between January 8th, 2017, and January 23rd, 2018, at all four clinical sites, were verbally informed of the nature of the study. Patients who expressed an interest in participating were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included upper or lower extremity pain that neither the patient nor referring physician (if referred) interpreted as having a spinal source. The patient had to be older than 15 years of age, be able to attend physiotherapy 2–3 times per week, be able to participate in exercise-based therapy and be able to understand English. Patients were excluded if the presenting pain was linked to inflammatory conditions (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) or if they presented with evidence of recent trauma (e.g. swelling or bruising). Patients were also excluded if neurological conditions were affecting motor function of the limbs or if they were attending physiotherapy for post-surgical rehabilitation. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate were given a letter of information. All patients provided written informed consent.

Sample size

Preliminary prevalence estimates found 10% to 40% of patients with extremity pain to be of spinal source [7,30,31]. To be conservative, 40% was selected since it provided the largest study sample. Considering a prevalence of 40%, 95% confidence intervals, and precision of 5%, the estimated sample size was calculated to be 369 participants [38].

Evaluation/intervention

Physiotherapists at all four clinical sites were trained in MDT (mean age: 45 years; mean years of clinical experience: 21). Two had Diplomas in MDT and were Instructors with the McKenzie Institute, one had his Diploma and one was Credentialed in MDT. Study participants were assessed using the MDT system and treated as the clinicians would normally treat. Demographic information was obtained as part of the history taking process using the MDT assessment forms. Height and weight were taken and other variables such as pain location, nature of the pain, duration of the pain, presence of current spinal pain etc. were all obtained during the patient’s history. A key feature of the physical examination involved establishing consistent baselines. These may include baseline pain, painful or limited extremity movements or functional activities that reproduce the symptoms. For example, squatting or stepping up may be appropriate baselines for a person presenting with knee pain. Once baselines were established for study participants, the clinician screened the spine using end-range repeated movements and loading strategies. For example, performing repeated lumbar spine extension in standing or repeated lumbar flexion in lying. Symptomatic response to movements and re-checking baselines was performed throughout the physical examination process. If the spinal movements had an effect on the symptoms or the baselines, the spine was assessed in further detail. Once the effect was deemed clear and repeatable, a provisional MDT classification was established. This provisional classification established either a spinal or extremity source of symptoms and the participants were allocated respectively into a spinal source group or an extremity source group. The spinal source group were guided to self-treat their symptoms by performing repeated or sustained end range directional preference exercises. For example, for the cervical spine, if it was found that the movement of cervical lateral flexion to the right changed the pain and functional baselines for the right shoulder, then this would be the directional preference exercise that the patient would perform regularly as a home exercise. Patients would be educated to monitor their own symptomatic response to ensure that the exercise had the desired effect.

If the pain was deemed of an extremity source further testing was performed to establish the MDT extremity classification. The intervention was based upon this classification. For example, if the classification was deemed to be an elbow Contractile Dysfunction in the direction of wrist extension, then repeated resisted wrist extension would be given as the appropriate loading strategy for patient home exercises. Follow-up visits either confirmed or rejected the initial MDT classification and treatment was either continued or altered based on the reassessment findings. The source of the pain was considered to be spinal if the patient’s primary extremity complaint for seeking care was resolved with spinal treatment only. The number of treatment sessions was recorded.

The location of pain was divided into eight regions: hip, thigh/leg, knee, ankle/foot, shoulder, arm/forearm, elbow, and wrist/hand.

Outcomes measures

Self-report outcome measures were the 11-point Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), Upper Extremity Functional Index (UEFI) for those with upper extremity symptoms or Lower Extremity Function Scale (LEFS) for those with lower extremity symptoms. The NPRS is an 11-point scale from zero, indicating no pain, to 10 indicating the worst pain possible. NPRS test-retest reliability has been demonstrated to be acceptable [39]. The UEFI and LEFS measure physical function and have both demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability and internal consistency [40,41]. The Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire (short form) (OMPSQ) was used as a screen for delayed recovery due to psychosocial influences and it has been shown to have moderate predictive ability [42]. The short form has similar accuracy to the longer version [43]. Global Rating of Change scale (GRC) is a measure of a patient’s self-perceived change and has been shown to have high face validity [44] and good test-retest reliability [45]. Study Participants completed these measures during the initial visit and at discharge. Global rating of change was completed only at discharge.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for group descriptors and study variables for the entire sample and for the extremity source and spinal source groups separately. Independent t-tests compared the spinal and extremity source groups on group descriptors (age, height, weight, body mass index, current spinal pain). To address the primary objective, a contingency table compared the proportion of the classification (extremity vs. spinal source) within the eight regions. A chi-square test examined the overall significance of the contingency table and comparison within each region were made after adjusting for multiple comparisons [46]. To address the secondary objective, effect sizes (d) between spinal and extremity source groups were calculated for the outcome scores at discharge; adjustments for initial visit scores and number of treatment sessions were made using an analysis of covariance [47]. Effect size calculations for GRC were only adjusted for number of treatment sessions since initial visit scores did not exist. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (d = 0.20), medium (d = 0.50), and large (d = 0.80) and positive values indicated that the spinal source group has better outcomes. Analyzes were completed with SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp). Effect sizes were calculated in Microsoft Excel.

Results

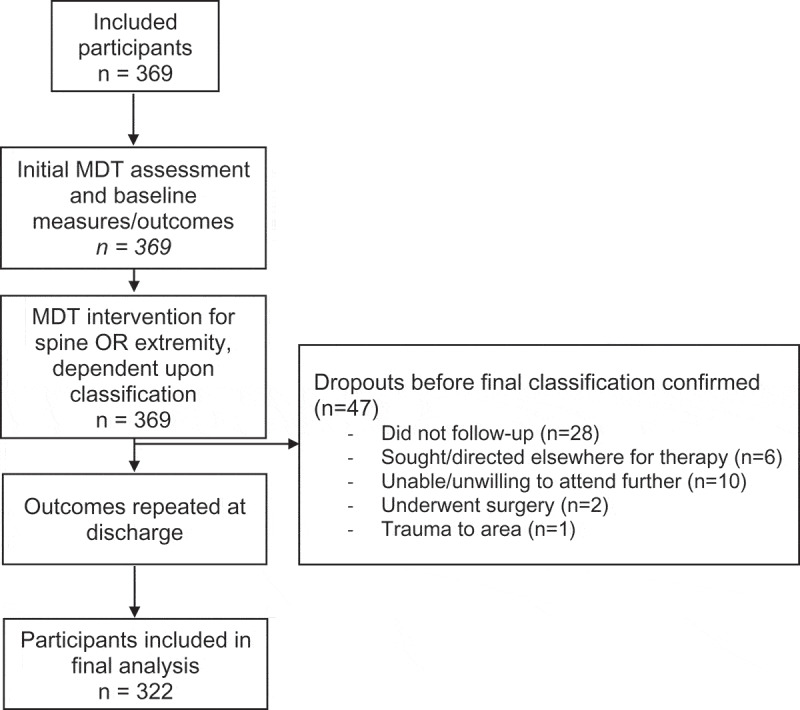

Initially, 369 potential participants were recruited. Forty-seven participants did not complete the study and were not included in the final analysis (Figure 1), leaving 322 participants in the final sample. All participants completed the NPRS, OMPSQ, and GRC. Participants with upper extremity pain completed the UEFI (n = 147) while participants with lower extremity pain completed the LEFS (n = 175). There were no significant differences in group descriptors between extremity and spinal source groups (Table 1). For the 322 participants, 140 (43.5%) were classified as having a spinal source of pain. There was a significant (χ2 = 38.295, p < 0.001) association between the classification and pain region. Adjusted comparisons within each region revealed a higher proportion of spinal classification in the arm/forearm (p = 0.027) and hip (p = 0.007) regions and a lower proportion of spinal classification in the knee (p = 0.002) (Table 2). There were no other statistically significant differences in classification within each region after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Design and flow of participants during study.

Table 1.

Group descriptors for the entire sample and both groups.

| Variable | Entire Sample (n = 322) | Extremity Source Group (n = 182) | Spinal Source Group (n = 140) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 47 (12) | 47 (13) | 47 (12) | 0.88 |

| Females, number (%) | 233 (72%) | 128 (70%) | 105 (75%) | - |

| Height (m), mean (SD)* | 1.70 (0.10) | 1.70 (0.10) | 1.69 (0.10) | 0.20 |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD)* | 76.13 (16.76) | 76.90 (16.92) | 75.11 (16.56) | 0.36 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)* | 26.42 (5.24) | 26.49 (5.31) | 26.33 (5.17) | 0.80 |

| Current spinal pain, number (%) | 46 (14%) | 19 (10%) | 27 (19%) | - |

Note: *There was missing weight and body mass index for 20 participants, and missing height values for 13 participants.

Table 2.

Contingency table of the proportions of spinal or extremity source of symptoms in each region.

| Regions | Extremity Source Frequency (%)* | Spinal Source Frequency (%)* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip | 9 (29.0%) | 22 (71.0%) | 31 |

| Thigh/leg | 5 (27.8%) | 13 (72.2%) | 18 |

| Knee | 58 (74.4%) | 20 (25.6%) | 78 |

| Ankle/foot | 34 (70.8%) | 14 (29.2%) | 48 |

| Shoulder | 44 (52.4%) | 40 (47.6%) | 84 |

| Arm/forearm | 2 (16.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 12 |

| Elbow | 14 (56.0%) | 11 (44.0%) | 25 |

| Wrist/hand | 16 (61.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | 26 |

| Total | 182 (56.5%) | 140 (43.5%) | 322 (100%) |

Note: *Percentages represent the percentage of spinal or extremity source within each region.

Descriptive statistics for the outcomes, number of treatment sessions, and effect sizes are provided in Table 3. Effect sizes indicated that the spinal source group had improved outcomes at discharge for all outcomes compared to the extremity source group after adjusting for initial visit scores and number of treatment sessions. This represented small effects for the OMPSQ, medium effects for the NPRS, UEFI and LEFS, and large effect for the GRC.

Table 3.

Means (standard deviation) for the outcome measures (unadjusted), number of treatment sessions and effect sizes of the discharge outcome scores.

| Variable (n) | Time | Extremity Source Group | Spinal Source Group | Effect Size* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPRS (n = 322) | Initial | 5.3 (1.8) | 5.1 (1.9) | 0.63 |

| Discharge | 2.2 (2.2) | 0.9 (1.1) | ||

| OMPSQ (n = 322) | Initial | 43.9 (12.5) | 43.4 (13.5) | 0.38 |

| Discharge | 26.0 (16.8) | 20.3 (10.7) | ||

| UEFI (n = 147) | Initial | 54.6 (14.4) | 53.8 (14.0) | 0.64 |

| Discharge | 66.7 (16.4) | 73.0 (9.4) | ||

| LEFS (n = 175) | Initial | 49.6 (13.8) | 50.0 (14.4) | 0.58 |

| Discharge | 65.5 (15.6) | 72.8 (6.8) | ||

| GRC (n = 322) | Discharge | 2.9 (1.9) | 4.0 (0.9) | 0.86 |

| Number of Treatment Session | - | 6.4 (2.9) | 5.5 (2.7) | - |

Note: *Positive effect sizes indicated that the outcomes at discharge favored the spinal source group.

n = sample size. NPRS = Numerical Pain Rating Score. OMPSQ = Orebro musculoskeletal pain questionnaire. UEFI = Upper extremity functional index.

LEFS = Lower extremity functional scale. GRC = Global rating of change

Discussion

This study is the first to comprehensively document the proportion of patients presenting with isolated extremity pain, who believed that their pain was not emanating from the spine, responded to spinal intervention and were hypothesized to have a spinal source of symptoms. The overall proportion for all extremity symptom locations with a spinal source in these 322 participants was 43.5% (Table 2).

For the joint/area specific data, there are some previously documented proportions to compare to; rates for the shoulder have been reported at 10% [31], 17% [30] and 29% [32]. The 47.6% in this study for the shoulder is thus the highest reported to date. The discrepancies in proportions from the existing studies is greater in those not incorporating an MDT approach [30,31] and this may reflect the different process employed to differentiate. The Heidar Abady study [32] reported using repeated movements in a baseline-test-recheck baseline method, consistent with the current methodology and had the closest proportion. For the elbow and the wrist/hand which showed 44% and 38.5% respectively, there are no existing studies to compare data with. We assume that these percentages would be considered high, with the logical expectation that the more distal the symptoms in the extremities, the lower the spinal source rate. In fact, this study shows such a trend, but it is gradual, with the proportion of spinal source in the elbow only slightly lower than in the shoulder, and the wrist/hand less than 10% lower. However, the proportion with pain locations between joints, arm/forearm shows the spinal source to be considerably higher at 83.3%. This may be reflective of the nature of referred somatic pain, which is more commonly reported as over a wider area rather than being specific to a joint [48]. Overall for the upper extremity, 48.3% of the participants were considered to have a spinal source which would appear to verify the need for this type of systematic approach in the initial examination and over the subsequent reassessment sessions.

The overall proportion of lower extremity pain to have a spinal source in this study was 39.4%, with 71% at the hip, 25.6% at the knee and 29.2% at the ankle/foot. The only joint where there is comparative data is at the knee with one retrospective study finding 45% of osteoarthritic knees had a spinal source of symptoms [7]. The proportion found in our study is comparatively low. One possible explanation may be that, in the Hashimoto study [7], over 50% of the participants with knee pain had concurrent back pain compared to 14% in this study (Table 1). Additionally, in the Hashimoto study they were not asked, or excluded, if they felt their back pain was the source of their knee pain [7]. The authors believe that compared to what would be generally expected, the proportion would still be considered high. The proportion of spinal source at the hip is the highest for any of the extremity joints. This is perhaps not surprising due to the close proximity and the well documented overlap in referral areas from the lumbar spine [3,25,49]. As with the upper extremity, the highest proportion of spinal source is between joints (thigh/leg) at 72.2%.

In regard to outcomes for the spinal source groups compared to the extremity source group, it is interesting that all of the discharge outcomes; pain, function and psychosocial factors favored the participants with a spinal source. The likely explanation lies with the classification: all but one of the spinal MDT classifications were ‘Derangements’. This MDT classification has a documented rapid response and good prognosis [32,50]. The extremity classifications were a mix of MDT classifications, including but not exclusively Derangements. This group of patients has typically shown different prognoses and response timelines [32]. These results should serve to encourage clinicians to fully explore the possibility of a spinal source of extremity pain knowing that this could result in superior outcomes.

Although the study extremity presentations do not conform to the criteria for radiculopathy [51], radicular pain may still be a possibility and has been proposed as a mechanism for at least some of the more proximal pain locations such as hip [52], shoulder [53,54] and knee pain [52]. However, with the documented low prevalence of radicular pain [48,52] and the proportions of patients in this study found to have a spinal source, this would appear to be an unlikely mechanism for the majority of patients. Hence, the most logical explanation of the nature of the presentations would be the somatic referral of symptoms from the spine [53,55]. The explanation as to how many of these spinal problems appear to mimic an extremity problem is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is understandable as to how it may confuse the patient, referring physician and potentially, the treating clinician. However, it is apparent that the practice of formulating a diagnosis solely, or predominantly, on pain location clearly warrants greater scrutiny.

One limitation of the study is due to the design. It cannot be concluded that these participants with extremity pain who were treated solely with spinal intervention would have had any different outcomes if they were managed solely with extremity interventions. Although, some credibility to the claim that the spine is the source of the problem would be the within-session changes in extremity baselines and the superior discharge outcomes compared to those treated as extremity problems. This study was not randomized, thus it cannot be assumed that the outcomes of either group were not due to other factors, such as natural history, regression to the mean or general influences in the therapeutic encounter rather than MDT specifically. Though, as stated above, the fact that the spinal group had better outcomes would tend to make this less likely. Another limitation is that the results may not be applicable to patients in other clinical settings or for clinicians without similar training, hence generalizability may be limited. One further limitation is that there were 47 participants who were recruited into the study but excluded from the analysis as they dropped out of the study prior to the final classification being confirmed (see Figure 1 for reasons for dropout). Thus, they could not be allocated to either group.

Many RCTs on extremity presentations do not document any criteria to exclude the spine as a potential source of symptoms or rely solely on symptom location [9,23,26,56–58]. The assumption must therefore be that the location of symptoms reflects the source of the symptoms. The results of this study would call into question this assumption, with the implication that many extremity RCTs have inadvertently included participants with a spinal source of symptoms. This would contaminate study populations, compromise the outcomes and result in suboptimal clinical practice [9]. It appears that these outcomes may be avoided with sufficient spinal screening when extremity baselines are established and retested following repeated spinal end range movements.

The other important implication is that if these spinal problems causing extremity symptoms are identified, then many can be managed by a self-management, exercise-based regime that enables the patient to treat the current episode and have the means to manage future episodes.

A thorough examination and reassessment to achieve this high proportion, as was carried out in this study, consumes more time and resources in the initial phases of management. However, with superior outcomes at discharge, along with the potential costly consequences of missing a spinal source, this initial investment could prove to be justified. The results would now need to be replicated and the outcomes substantiated in a randomized trial.

Conclusion

The study reports a high proportion of extremity presentations where the symptoms were found to be of a spinal source and responded to spinal intervention. This would indicate that current spinal screening for extremity problems is not optimized and that a symptomatically driven ‘baseline-test-recheck baseline’ process has significant potential for exposing an unrealized source of extremity symptoms.

Biographies

Richard Rosedale graduated from Guy’s Hospital School of Physiotherapy (London, UK) in 1992. After emigrating to Canada, he completed his Diploma in Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (Dip. MDT) in 1997. Richard has worked in orthopedics and in Occupational Health since 1993. Richard has been active in research since 2007 and has authored or coauthored over a dozen papers, primarily exploring the clinical utility of MDT. He has been the Institute’s Reference Coordinator since 2015. Since 2003 Richard has been a member of the McKenzie Institute teaching faculty. He has served on the Scientific Committees of numerous McKenzie Institute Conferences and is a Diploma examiner. In 2005 Richard was appointed onto the Institute’s International Education Council. In 2018 Richard was appointed as the International Director of Education and the Institute’s Diploma Coordinator.

Ravi Rastogi completed his Bachelor of Science in Physical Therapy from Western University in 1998. Ravi’s interest in research led him to return to Western University where he completed his Master of Science in Physical Therapy in 2006. Since graduating, Ravi has always worked in the orthopedic field, both in the private and public sector. Ravi credentialed in the McKenzie method of Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy in 2011. Ravi is currently practicing as in an Advanced Practice role as the lead of a Musculoskeletal Rapid Access Program for low back pain in Southwestern Ontario.

Josh Kidd has been practicing since 2007 of which time his professional career has been focused in orthopedics. He completed his board certification in orthopedics in 2010, this was followed by a Diploma in MDT in 2011, a Masters in Orthopedic Manual Therapy in 2015, and was awarded Fellowship status through the American Academy of Orthopedic and Manual Physical Therapy in 2016. He is continually involved in clinical research and has been published in multiple peer reviewed journals. In addition to presenting a various national and international conferences.

He is faculty for the McKenzie Institute and the clinical coordinator for the McKenzie Institute USA Orthopedic Residency Program and mentor for the McKenzie Institute USA Orthopedic Manual Physical Fellowship Program.

Greg Lynch graduated from the Otago School of Physiotherapy in 1991. He completed the Diploma in Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy (Dip MDT) in 1994 and the Diploma in Manipulative Therapy (Dip MT) in 1996. Greg was recognized as an Advanced Practitioner with the NZ College of Physiotherapy (MNZCP). He has been in private practice since 1992 and is a Co-Director and senior physiotherapist of Inform Physiotherapy Limited and was a founding Director of Wellington Sports Medicine. He has been an accredited provider with ‘High Performance Sport New Zealand’ since 2000. He is currently president of the Wellington branch of Sports Medicine New Zealand. Greg has been a Faculty member for the McKenzie Institute International since 2004. He has lectured in a number of countries around the world as well as presenting at numerous conferences. Greg has been a member of the MII Education Council since 2017 and appointed to the Board of Trustees of the McKenzie Institute in 2018.

Georg Supp has been a fulltime physical therapist since 1992. Since 1997 he has run the rehabilitation center PULZ in Freiburg in Germany. He received the Diploma in Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy from The McKenzie Institute International in 1999. The focus of his intensive clinical work is on chronic back and neck patients and extremity problems, especially sports injuries. He’s treating mainly runners of different levels. Georg has published book chapters, articles, comments and letters in several peer-reviewed journals. He has been the editor Germany’s first journal on sports physical therapy SPORTPHYSIO from 2013 – 2017. He is an international instructor of the McKenzie Institute International and vice president of the German McKenzie branch. Georg is the secretary of the International MDT Research Foundation (IMDTRF) and founder of IMDTRF Germany. He’s also a member of the Education Council of the McKenzie Institute International. Currently Georg is conducting research on patient-therapist communication and return to activity for spinal patients.

Shawn M Robbins is an Associate Professor in the School of Physical and Occupational Therapy at McGill University. He completed his BScPT and PhD at the University of Western Ontario in 2001 and 2010 respectively and did a post-doctoral fellowship at Dalhousie University. Dr. Robbins’ research utilizes biomechanical and clinical measures to assess orthopedic health conditions and the interventions used to treat these conditions in both clinical and laboratory settings. He also evaluates the impact of player characteristics, task demands, and equipment design on ice hockey skills.

Disclosure statement

Richard Rosedale is employed as the International Director of Education and an International Instructor with the McKenzie Institute International. Josh Kidd is an instructor with the McKenzie Institute USA. Greg Lynch is a Director on the Board of Trustees of the McKenzie Institute International and employed as an International Instructor. Georg Supp is a member of the McKenzie Institute's Education Council and employed as an International Instructor.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants

References

- [1].Bokshan SL, DePasse JM, Eltorai AEM, et al. An evidence-based approach to differentiating the cause of shoulder and cervical spine pain. Am J Med. 2016;129(9):913–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sembrano JN, Yson SC, Kanu OC, et al. Neck-shoulder crossover: how often do neck and shoulder pathology masquerade as each other? Am J Orthop. 2013;42(9):E76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Buckland AJ, Miyamoto R, Patel RD, et al. Differentiating hip pathology from lumbar spine pathology: key points of evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25(2):e23–e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Prather H, Cheng A, Steger-May K, et al. Hip and lumbar spine physical examination findings in people presenting with low back pain, with or without lower extremity pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017;47(3):163–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Saito J, Ohtori S, Kishida S, et al. Difficulty of diagnosing the origin of lower leg pain in patients with both lumbar spinal stenosis and hip joint osteoarthritis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(25):2089–2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gunn C, Milbrandt WE.. Tennis elbow and the cervical spine. Can Med Assoc J. 1976;114(9):803–809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hashimoto S, Hirokado M, Takasaki H.. The most common classification in the mechanical diagnosis and therapy for patients with a primary complaint of non-acute knee pain was spinal derangement: a retrospective chart review. J Man Manip Ther. 2019;27(1):33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pheasant S. Cervical contribution to functional shoulder impingement: two case reports. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2016;11(6):980–991. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Walker T, Salt E, Lynch G, et al. Screening of the cervical spine in subacromial shoulder pain: A systematic review. Shoulder Elb. 2018. September 20. DOI: 10.1177/1758573218798023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Gill T, Shanahan E, Allison D, et al. Prevalence of abnormalities on shoulder MRI in symptomatic and asymptomatic older adults. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(8):863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Reilly P, Macleod I, Macfarlane R, et al. Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: A review of cadaveric and radiological studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(2):116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schibany N, Zehetgruber H, Kainberger F, et al. Rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic individuals: a clinical and ultrasonographic screening study. Eur J Radiol. 2004;51(3):263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Silvis ML, Mosher TJ, Smetana BS, et al. High prevalence of pelvic and hip magnetic resonance imaging findings in asymptomatic collegiate and professional hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(4):715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Thompson S, Fung S, Wood D. The prevalence of proximal hamstring pathology on MRI in the asymptomatic population. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25(1):108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hegedus EJ, Goode A, Campbell S, et al. Physical examination tests of the shoulder: a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med. 2008;42:80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hegedus EJ, Wright AA, Cook C. Orthopaedic special tests and diagnostic accuracy studies: house wine served in very cheap containers. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(22):1578–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture–a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Reiman M, Goode A, Hegedus E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests of the hip: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Thomas S, et al. Lack of uniformity in diagnostic labeling of shoulder pain: time for a different approach. Man Ther. 2008;13:478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Heidar Abady A, Rosedale R, Chesworth BM, et al. Consistency of commonly used orthopedic special tests of the shoulder when used with the McKenzie system of mechanical diagnosis and therapy. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;33:11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Falvey C, King E, Kinsella S, et al. Athletic groin pain (part 1): A prospective anatomical diagnosis of 382 patients - Clinical findings, MRI findings and patient-reported outcome measures at baseline. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(7):423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hussein AZ, Ibrahim MI, Hellman MA, et al. Static progressive stretch is effective in treating shoulder adhesive capsulitis: prospective, randomized, controlled study with a two-year follow-up. Eur J Physiother. 2015;17(3):138–147. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Reiman MP, Mather R, Cook CE. Physical examination tests for hip dysfunction and injury. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(1):357–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tijssen M, van Cingel R E., de Visser E, et al. Hip joint pathology: relationship between patient history, physical tests, and arthroscopy findings in clinical practice. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(3):342–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of Tai Chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mitchell C, Adebajo A, Hay E, et al. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. BMJ. 2005;331:1124–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cohen SP, Hooten WM. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ. 2017;358:j3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Menon A, May S. Shoulder pain: differential diagnosis with mechanical diagnosis and therapy extremity assessment - A case report. Man Ther. 2013;18(4):354–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Karel YHJM, GGM S-P, Thoomes-de Graaf M, et al. Physiotherapy for patients with shoulder pain in primary care: a descriptive study of diagnostic- and therapeutic management. Physiother. 2017;103(4):369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cannon DE, Dillingham TR, Miao H, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders in referrals for suspected cervical radiculopathy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1256–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Heidar Abady A, Rosedale R, Chesworth BM, et al. Application of the McKenzie system of mechanical diagnosis and therapy (MDT) in patients with shoulder pain; a prospective longitudinal study. J Man Manip Ther. 2017;25(5):235–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ammendolia C. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis and its imposters: a case studies. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2014;58(3):312–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Greenwood M, Erhard R, Jones D. Differential diagnosis of the hip vs lumbar spine: five case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27(4):308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].May S, Rosedale R. An international survey of the comprehensiveness of the McKenzie classification system and the proportions of classifications and directional preferences in patients with spinal pain. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;39:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Garcia AN, Menezes C, De SFS. Reliability of mechanical diagnosis and therapy system in patients with spinal pain: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;22:1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Takasaki H, Okuyama K, Rosedale R. Inter-examiner classification reliability of mechanical diagnosis and therapy for extremity problems – systematic review. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2017;27:78–84.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Naing L, Winn T, Rusil BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jensen MP, McFarland CA. Increasing the reliability and validity of pain intensity measurement in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1993;55(2):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, et al. The lower extremity functional scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. Phys Ther. 1999;79(4):371–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Stratford PW, Binkley JM, Stratford DM. Development and initial validation of the upper extremity functional index. Physiother Can. 2001;53(4):259–267. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Hockings RL, McAuley JH, Maher CG. A systematic review of the predictive ability of the Orebro Musculoskeletal pain questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(15):494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Örebro Musculoskeletal pain screening questionnaire. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(22):1891–1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fischer D, Stewart AL, Bloch DA, et al. Capturing the patient’s view of change as a clinical out- come measure. JAMA. 1999;282:1157–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Costa LOP, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Clinimetric testing of three self-report outcome measures for low back pain patients in Brazil: Which one is the best? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2459–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Beasley TM, Schumacker RE. Multiple regression approach to analyzing contingency tables: post hoc and planned comparison procedures. J Exp Educ. 1995;64:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Contrasts and correlations in effect-size estimation. Psychol Sci. 2000;11:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Murphy DR, Hurwitz E, Gerrard J, et al. Pain patterns and descriptions in patients with radicular pain: does the pain necessarily follow a specific dermatome? Chiropr Osteopat. 2009;17:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lesher JM, Dreyfuss P, Hager N, et al. Hip joint pain referral patterns: a descriptive study. Pain Med. 2008;9:22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Long A, Donelson RG, Fung T. Does it matter which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29(23):2593–2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Genevay S, Courvoisier DS, Konstantinou K, et al. Clinical classification criteria for neurogenic claudication caused by lumbar spinal stenosis. The N-CLASS Criteria Spine J. 2018;18(6):941–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].DeFroda SF, Daniels AH, Deren ME. Differentiating radiculopathy from lower extremity arthropathy. Am J Med. 2016;129(10):1124.e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].McClatchie L, Laprade J, Martin S, et al. Mobilizations of the asymptomatic cervical spine can reduce signs of shoulder dysfunction in adults. Man Ther. 2009;14(4):369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhang AL, Theologis AA, Tay B, et al. The association between cervical spine pathology and Rotator Cuff dysfunction. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(4):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Oikawa Y, Ohtori S, Koshi T, et al. Lumbar disc degeneration induces persistent groin pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(2):114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Abbott JH, Robertson MC, Chapple C, et al. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(4):525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Allen KD, Arbeeva L, Callahan LF, et al. Physical therapy vs internet-based exercise training for patients with knee osteoarthritis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26(3):383–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].van Linschoten R, van Middelkoop M, M Y B, et al. Supervised exercise therapy versus usual care for patellofemoral pain syndrome: an open label randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b4074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants