Abstract

Cobas Amplicor CMV Monitor (CMM) and Quantiplex CMV bDNA 2.0 (CMV bDNA 2.0), two new standardized and quantitative assays for the detection of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in plasma and peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs), respectively, were compared to the CMV viremia assay, pp65 antigenemia assay, and the Amplicor CMV test (P-AMP). The CMV loads were measured in 384 samples from 58 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1-infected, CMV-seropositive subjects, including 13 with symptomatic CMV disease. The assays were highly concordant (agreement, 0.88 to 0.97) except when the CMV load was low. Quantitative results for plasma and PBLs were significantly correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.92). For PBLs, positive results were obtained 125 days before symptomatic CMV disease by CMV bDNA 2.0 and 124 days by pp65 antigenemia assay, whereas they were obtained 46 days before symptomatic CMV disease by CMM and P-AMP. At the time of CMV disease diagnosis, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of CMV bDNA 2.0 were 92.3, 97.8, 92.3, and 97.8%, respectively, whereas they were 92.3, 93.3, 80, and 97.8%, respectively, for the pp65 antigenemia assay; 84.6, 100, 100, and 95.7%, respectively, for CMM; and 76.9, 100, 100, and 93.8%, respectively, for P-AMP. Considering the entire follow-up, the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of CMV bDNA 2.0 were 92.3, 73.3, 52.1, and 97.1%, respectively, whereas they were 100, 55.5, 39.4, and 100%, respectively, for the pp65 antigenemia assay; 92.3, 86.7, 66.7, and 97.5%, respectively, for CMM; and 84.6, 91.1, 73.3, and 95.3%, respectively, for P-AMP. Detection of CMV in plasma is technically easy and, despite its later positivity (i.e., later than in PBLs), can provide enough information sufficiently early so that HIV-infected patients can be effectively treated. In addition, these standardized quantitative assays accurately monitor the efficacy of anti-CMV treatment.

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in severely immunodepressed patients, particularly those with end-stage AIDS (12), even though the incidence of CMV disease has decreased since human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitors were introduced. The diagnosis of CMV diseases, including retinitis, pneumonia, gastrointestinal disorders, and encephalitis, is still based on the clinical, histological, and virological criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (9). Risk factors that result in the development of CMV disease in AIDS patients include low CD4+ T-cell counts (i.e., <100 cells/μl) and CMV viremia (13, 24). Indeed, CMV probably spreads during a subclinical stage called CMV infection that precedes CMV disease by various lengths of time.

A few drugs (ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir) have been demonstrated to have efficacy against CMV disease, even though relapses are common. Anti-CMV prophylaxis has been attempted, but the toxicity associated with the available drugs remains a major problem. Efforts have focused on defining patients at risk for disease prior to the onset of the symptoms and giving them so-called preemptive or early antiviral treatment (15, 26).

Thus, quantitation of the systemic CMV load during the subclinical stage might provide a sensitive and specific method for prediction of the development of CMV disease. The procedures used for the detection of CMV viremia include virus isolation, viral antigen staining, and nucleic acid detection by PCR or hybridization.

Qualitative PCR detection of CMV DNA in peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) is considered the most sensitive method (31, 36). However, it suffers from a lack of specificity for the diagnosis of CMV disease in some groups of immunocompromised subjects (16, 36). More recently, different strategies have been applied to increase the specificity and positive predictive value of diagnostic procedures. Some of them are PCR-based detection assays, such as quantitative PCR (3, 35), which use plasma or serum as the source of cell-free viral DNA (21, 28, 29), and some detect late CMV transcripts in whole blood by reverse transcriptase PCR (16, 19). At present, it is not yet clear which PCR procedure (qualitative or quantitative) and which blood fraction (PBLs or plasma) are optimal for use in the diagnosis of CMV disease. Compared to PCR, the advantage of hybridization, as shown for HIV-1 detection with branched DNA (bDNA) technology (20), is that the test is not subject to contamination or inhibition.

In this study, we sought to determine the clinical utility of three assays for the monitoring of HIV-1-infected, CMV-seropositive subjects with low CD4+ T-cell counts for the diagnosis of CMV disease: the Roche qualitative plasma Amplicor CMV assay (P-AMP; Roche, Bâle, Switzerland), the Roche quantitative plasma Cobas Amplicor CMV Monitor assay (CMM), and the Chiron quantitative PBL assay, quantiplex bDNA CMV 2.0 (bDNA CMV 2.0; Chiron Corporation, Emeryville, Calif.).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and samples.

HIV-1-infected, CMV-seropositive subjects were enrolled in this study between November 1995 and September 1997 if their CD4+ T-cell count at that time was <100/μl. The stage of HIV-1 infection was determined for each subject according to the 1993 CDC classification system (8).

The patients were monitored (by physical examination and by CD4+ T-cell count and blood CMV load determinations) at 2- or 3-month intervals until death or completion of the study (2 years). Some patients with newly diagnosed CMV disease were also included. CMV disease was defined on the basis of typical ophthalmological findings or the presence of characteristic intranuclear inclusions in bronchial or digestive tract tissues or in bronchoalveolar lavage cells. The same experienced physician conducted the prospective ophthalmological follow-up. Other diseases indicative of AIDS were diagnosed according to CDC criteria (9).

All patients received co-trimoxazole. The use of anti-Mycobacterium avium complex prophylaxis was left to the discretion of the treating physician. No patient received anti-CMV prophylaxis. Blood samples were serially drawn into tubes containing heparin for shell vial (SV) culture and pp65 antigen (Ag) assay (Argène Biosoft, Varilhes, France) and into tubes containing EDTA for the qualitative P-AMP (Roche), the quantitative CMM (Roche), and the quantiplex bDNA CMV 2.0 (Chiron Corporation) assays. Blood was collected every 2 or 3 months from subjects with asymptomatic CMV infection and was collected before the beginning of anti-CMV therapy from patients with symptomatic CMV disease: posttherapy blood samples were available for most of the latter patients.

CMV viremia.

To determine CMV viremia (SV assay), PBLs were isolated from a 7-ml heparinized sample; 0.2 ml of cell suspension (containing at least 5 × 105 PBLs) was deposited onto duplicate human fibroblast (MRC-5) monolayers, and the monolayers were centrifuged at 2,000 × g at room temperature for 45 min. CMV was identified by immunohistochemical labeling after 48 h of culture (anti-human CMV antibody E13 [Argène Biosoft], peroxidase-coupled rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G; Nordic Immunology, Tilburg, The Netherlands]). This test was considered positive when at least one viral inclusion was observed.

pp65 Ag assay.

PBL Cytospin slides (2 × 105 PBLs per spot) prepared from 7-ml heparinized blood samples were subjected to immunofluorescence staining with monoclonal antibodies directed against human CMV lower matrix phosphoprotein pp65, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (human CMV antigenemia immunofluorescence kit; Argène Biosoft). Results are expressed as the number of CMV antigen-positive cells per 200,000 PBLs, and the test was considered positive when at least one fluorescent cell was observed; up to 200 fluorescent cells were counted.

P-AMP.

P-AMP is a qualitative PCR test for the detection of CMV DNA in plasma and was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, 50 μl of plasma was mixed with 500 μl of extraction reagent, and the mixture was incubated at 100°C for 30 min; 50 μl of the mixture was transferred into a PCR tube containing all the components necessary for PCR amplification plus an internal control. Amplification was performed in a Cetus 2400 apparatus (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). After amplification, the nucleotide sequences were detected by an enzyme immunoassay technique. The absorbances at 450 nm (A450s) were measured. Specimens with absorbance values of ≥0.35 were considered positive, and those with absorbance values of <0.35 and an internal control optical density (OD) of ≥0.35 were considered negative for CMV. The limit of detection of this qualitative assay is 1,000 copies of CMV DNA/ml.

CMM.

CMM is a quantitative PCR test for CMV DNA in plasma and PBLs with a quantitation standard (QS) that contains primer-binding sites identical to those of the CMV target (365 bp within UL 54) and a unique probe-binding region that allows the QS amplicon to be distinguished from the CMV amplicon. The QS was incorporated into each specimen at a known copy number and was retained through the specimen preparation, PCR amplification, hybridization, and detection steps along with the CMV target. CMV DNA levels in the test samples were determined by comparing the absorbance of the specimen to the absorbance obtained with the QS. The following equation was used to calculate the CMV load of the specimen, in number of copies of CMV DNA per milliliter: (total CMV OD/total QS OD) × input QS copies per PCR × 40.

Briefly, CMV DNA was extracted from 200 μl of plasma with 600 μl of CMV Monitor Lysis Reagent containing a known number of QS DNA molecules. The DNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in 400 μl of CMV Monitor Specimen Diluent. An aliquot (50 μl) of the processed sample was added to 50 μl of the CMM Master Mix for PCR amplification. Amplification and detection were automatically performed by the Cobas Amplicor System. Results are expressed as A660 and as numbers of copies per milliliter. One CMM low-positive control, one CMM high-positive control, and one CMM negative control were processed with each batch of samples. For a run to be valid, individual samples must yield CMV and QS OD values between 0.2 and 2.0 by determination of the A660. The result for any specimen with a QS OD that did not meet the criteria described above was considered invalid. The limit of detection of this quantitative assay is 400 copies of CMV DNA/ml.

bDNA CMV 2.0.

The bDNA CMV 2.0 uses the bDNA technology to quantitate PBL CMV DNA load on dry pellets of 106 PBLs. Seven milliliters of EDTA-anticoagulated blood was incubated for 20 min at 37°C. The buffy coat fraction was harvested and resuspended in 10 ml of phosphate-buffered saline and washed. Residual contaminating erythrocytes were lysed osmotically by exposing the pellet to sterile distilled water for 20 s before the pellet was resuspended in 10×-concentrated phosphate-buffered saline to restore tonicity. The washed leukocytes were finally counted and were adjusted to aliquots of 106 PBLs per dry pellet, which were stored at −80°C if they were not immediately processed. This assay is based on the hybridization of 43 different and specific oligonucleotide probes complementary to the glycoprotein B (gB) gene (major envelope glycoprotein) of the CMV genome. A bDNA molecule provides multiple binding sites for an enzyme-labeled probe, and a quantitative chemiluminescent signal directly proportional to the sample target input is generated. The current version has improved sensitivity over an earlier one (bDNA CMV 1.0): the background signal from nonspecific hybridization of amplifiers has been reduced by incorporating nonnatural nucleotides into the generic sequences of the assay components and by adding an amplification step designed to increase the number of bDNA molecules bound. All specimens were tested in duplicate, and CMV DNA was quantitated from a standard curve of CMV DNA run in parallel for each assay. The lower limit of detection of this quantitative assay is 900 copies of CMV DNA/106 PBLs.

Quantitation of HIV-1 RNA in plasma.

HIV-1 was first concentrated from 1 ml of EDTA-anticoagulated plasma in duplicate by centrifugation at 23,500 × g for 1 h. The HIV-1 RNA in plasma was quantified by the Quantiplex HIV-1 RNA 2.0 assay (bDNA) (Chiron Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Flow cytometry.

All CD4+ lymphocyte counts were done in the same laboratory. Cells were immunophenotyped by a four-color protocol (CD45, CD3, CD4, and CD8 [Tetrachrome; Coulter Company, Hialeah, Fla.]) before analysis with an Epics XL4 flow cytometer (Coulter) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analyses.

The CD4+ T-cell counts and HIV loads of patients with or without CMV disease are expressed in the Results as medians (25th to 75th percentiles) and were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. The levels of concordance among the SV, pp65 Ag, P-AMP, CMM, and bDNA CMV 2.0 assays were assessed with the kappa coefficient of concordance.

First, the ability of the assays to identify HIV-1-infected patients with CMV disease was assessed by using the blood samples obtained at the time of CMV disease diagnosis for clinically symptomatic CMV-infected patients and the last blood sample from CMV disease-free patients. When CMV disease was clinically documented at the time of inclusion in the study, the blood sample that was analyzed was recovered 24 h before the initiation of anti-CMV therapy. Predictive values of CMV load assays for diagnosis of CMV disease were calculated by using the prevalence based on the 2-year cumulative incidence of CMV disease development in the study population. For the entire follow-up of the patients, the performance of each assay was estimated by defining a positive result as at least one positive measure prior to the diagnosis of CMV disease or until the last follow-up assessment for patients without CMV disease and a negative result as negative results by all measures during the entire follow-up.

RESULTS

Patients. (i) At inclusion.

Fifty-eight HIV-1-positive, CMV-seropositive patients (51 males and 7 females; median age, 38 years [25th to 75th percentiles, 33 to 47]) were enrolled in this study. The CDC classifications of HIV-1 infection status were as follows: CDC A, 36 patients; CDC B, 11 patients; CDC C, 11 patients. No patient had a prior history of CMV disease.

Fifty-four patients were asymptomatic for CMV disease and were prospectively monitored for CMV viremia and CMV DNA load (median [25th to 75th percentiles] CD4+ count = 19 [5 to 35] cells/μl; median [25th to 75th percentiles] HIV-1 load, 92,900 [16,000 to 172,000] copies/ml). Four patients had CMV disease at inclusion: three had CMV retinitis and one had CMV digestive disease (median [25th to 75th percentiles] CD4+ count, 8 [4 to 48] cells/μl; median [25th to 75th percentiles] HIV-1 load, 526,000 [247,000 to 758,000] copies/ml).

All the patients received a combination of two reverse transcriptase nucleoside inhibitors (RTNIs).

(ii) During follow-up.

During follow-up an HIV-1 protease inhibitor (PI) was added to the RTNIs for 44 of the 58 patients as a function of the HIV-1 load in plasma and the CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.

Forty-five patients did not develop CMV disease during the 2 years of monitoring. For the last blood sample from these CMV disease-free patients, their median CD4+ T-cell count was relatively high (90 cells/μl [25th to 75th percentiles, 24 to 135 cells/μl]), and their median plasma HIV-1 RNA was relatively low (1,400 copies/ml [25th to 75th percentiles, 500 to 49,000 copies/ml]).

Nine patients developed CMV disease during follow-up: seven of them had a retinitis, one had gastrointestinal disease, and one had pneumonia. In contrast to their CMV disease-free counterparts, their median CD4+ T-cell count was low (15 cells/μl [25th to 75th percentiles, 1 to 39 cells/μl]), and the median number of plasma HIV-1 RNA copies per milliliter at the time of CMV disease diagnosis was quite high (154,700 copies/ml [25th to 75th percentiles, 64,000 to 800,000 copies/ml]). CD4+ T-cell counts (P < 1 × 10−3) and plasma HIV-1 RNA loads (P < 2 × 10−3) differed significantly between patients who did or did not develop CMV disease.

Among the 13 patients with CMV disease (at inclusion or during follow-up), 10 started triple therapy with a PI during the follow-up period. All patients received anti-CMV treatment (foscarnet or ganciclovir) at the time of diagnosis of CMV disease.

Concordance among the different tests.

The 384 blood samples tested by all CMV assays were obtained from the 58 HIV-1- and CMV-seropositive subjects, including 13 patients with a diagnosis of CMV disease. Use of the 1+ cell positivity threshold as the pp65 Ag assay threshold may be associated with false-positive results; indeed, most users of this assay use a threshold of 3+ to 5+ cells. So, we compared 1+ and 5+ cell cutoffs for this assay. The observed total concordance (number of concordant results divided by the number of concordant results plus number of discordant results) among the qualitative results of the CMV assays and CMM or bDNA CMV 2.0 are reported in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Concordance among results of CMV assays and CMM or bDNA CMV 2.0 for 384 samples

| CMV assay (positivity threshold) | No. of samples with the following CMV assay results/quantitative test result concordancea

|

Total concordanceb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +/+ | −/− | +/− | −/+ | ||

| CMM | |||||

| SV assay | 22 | 326 | 3 | 33 | 0.91 |

| pp65 Ag assay (1+ cell) | 52 | 284 | 45 | 3 | 0.88 |

| pp65 Ag assay (5+ cells) | 48 | 321 | 8 | 7 | 0.96 |

| P-AMP (1,000 cc/ml) | 49 | 323 | 6 | 6 | 0.97 |

| bDNA CMV 2.0 (900 c/106 PBLs) | 52 | 311 | 18 | 3 | 0.95 |

| bDNA CMV 2.0 | |||||

| SV assay | 24 | 313 | 1 | 46 | 0.88 |

| pp65 Ag assay (1+ cell) | 66 | 283 | 31 | 4 | 0.91 |

| pp65 Ag assay (5+ cells) | 54 | 312 | 2 | 16 | 0.95 |

| P-AMP (1,000 c/ml) | 51 | 310 | 4 | 19 | 0.94 |

| CMM (400 c/ml) | 52 | 311 | 3 | 18 | 0.95 |

+, positive results; −, negative results.

Number of samples with concordant results/(number of samples with concordant results + number of samples with discordant results).

c, copies.

For most samples with discordant results (positive result by one assay but a negative result by another assay), the CMV DNA load detected by the assay with a positive result was low (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

CMV DNA loads of samples that generated discordant results between CMV assays

| CMV assay with a negative result (positivity threshold) | CMV DNA load (median [25th to 75th percentile; no. of samples])

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMM (103 ca/ml) | bDNA CMV 2.0 (103 c/106 PBLs) | pp65 Ag assay (no. of positive cells/2 × 105 PBLs)

|

||

| 1+ cell | 5+ cells | |||

| pp65 Ag assay (1+ cell) | 1.5 (0.7–7.7; 3) | 1.5 (1.2–1.9; 4) | ||

| pp65 Ag assay (5+ cells) | 1.5 (0.7–2.7; 7) | 2.2 (1.5–3.1; 16) | 2 (1–4; 41) | |

| P-AMP (1000 c/ml) | 2.1 (0.7–3.6; 6) | 2.8 (1.6–9.9; 19) | 3 (2–5; 47) | 24 (9–34; 9) |

| CMM (400 c/ml) | 2.6 (2.2–5.6; 18) | 3 (2–5; 45) | 13 (9–30; 8) | |

| bDNA CMV 2.0 (900 c/106 PBLs) | 2.8 (1.6–3.6; 3) | 2 (1–3; 31) | 12 (6–7; 2) | |

c, copies.

CMM and pp65 Ag assay.

By use of the 1+ cell positivity threshold for the pp65 Ag assay, the results for 88% of the samples were highly concordant; 74% were negative and 14% were positive. The positive-negative and negative-positive discordance rates were 12 and 1%, respectively (Table 1).

By use of the 5+ cell positivity threshold for the pp65 Ag assay, the results were even more highly concordant (96%); 84% of the samples were negative and 13% were positive. The positive-negative and negative-positive discordance rates were both 2% (Table 1).

Some weakly positive pp65 Ag assay and negative CMM results were obtained for patients who previously and/or subsequently presented with a positive CMM result in the course of a CMV infection (see Table 4); for these patients, the pp65 Ag assay-positive and CMM-negative results might not be considered real discrepancies.

TABLE 4.

Longitudinal analysis of the 13 subjects who developed CMV diseasea

| Patient (CMV disease) | Day of CMV disease | Treatment

|

No. of CD4+ cells/μl | CMV assay result

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CMV | PI | SV assay | P-AMP | pp65 Ag assay (no. of positive cells/2 × 105 cells) | CMM (c/ml) | bDNA (c/106 PBLs) | |||

| 1 (R) | −95 | − | + | 3 | − | + | 172 | 5,870 | 38,200 |

| 0 | G | + | 33 | − | − | 2 | 1,270 | <900 | |

| +165 | G | + | 64 | + | − | 5 | <400 | 2,410 | |

| 2 (R) | −114 | − | − | 56 | − | − | 2 | <400 | <900 |

| −63 | − | − | 34 | + | + | >200 | 17,200 | 350,500 | |

| −50 | − | − | 22 | + | + | >200 | 146,000 | 981,900 | |

| −48 | − | − | ND | − | + | >200 | 93,200 | 270,000 | |

| −42 | − | − | 16 | + | + | 181 | 81,100 | 1,408,000 | |

| 0 | F | − | 39 | + | + | >200 | 40,800 | 102,000 | |

| +20 | F | − | 7 | − | + | 17 | 21,900 | 555,120 | |

| +37 | F | − | 72 | + | + | >200 | 49,400 | 412,812 | |

| 3 (R) | 0 | F | − | 10 | + | + | 20 | 1,530 | 4,400 |

| +4 | F | − | 27 | + | + | 24 | 830 | 9,050 | |

| +12 | F | − | 14 | + | + | 0 | 7,670 | 2,140 | |

| 4 (R) | −270 | − | − | 21 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 |

| −120 | − | + | 21 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| −60 | − | + | 45 | − | − | 2 | <400 | <900 | |

| 0 | F | + | 80 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| 5 (R) | 0 | F | + | 43 | − | − | 48 | 9,070 | 121,000 |

| +3 | F | + | 17 | − | + | 66 | 9,950 | 50,000 | |

| +6 | F | + | 27 | − | − | 4 | 2,750 | <900 | |

| +13 | F | + | 85 | − | + | 0 | 1,550 | <900 | |

| 6 (D) | 0 | F | − | 1 | − | + | 12 | 52,400 | 108,000 |

| +11 | F | − | 1 | − | + | 4 | 5,930 | 36,400 | |

| +18 | F | − | 2 | − | + | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| 7 (R) | 0 | F | − | 6 | + | + | >200 | 289,000 | 1767,000 |

| +4 | F | − | ND | − | + | >200 | 123,000 | 559,370 | |

| +8 | F | − | 2 | − | + | >200 | 253,000 | 580,000 | |

| +15 | F | − | 3 | − | + | 33 | 45,400 | 8,280 | |

| +30 | F | − | 11 | − | + | 21 | 5,330 | 2,870 | |

| +80 | F | + | 11 | + | + | >200 | 44,600 | 1,767,000 | |

| +140 | F | + | 54 | + | + | 37 | 2,300 | 5,930 | |

| +230 | F | + | 80 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| 8 (R) | −381 | − | − | 16 | − | − | 8 | <400 | 2,191 |

| −321 | − | − | 13 | − | + | 9 | <400 | 5,597 | |

| −171 | − | + | 16 | + | − | 34 | <400 | 2,822 | |

| −81 | − | + | 34 | − | − | 25 | <400 | 9,902 | |

| 0 | F | + | 36 | − | + | >200 | 2,250 | 110,300 | |

| +60 | F | + | 18 | − | + | 0 | 4,800 | ND | |

| 9 (R) | −135 | − | − | 22 | − | − | 4 | <400 | 1,570 |

| −75 | − | − | 12 | − | − | 1 | <400 | 550 | |

| −45 | − | − | 25 | − | + | 30 | 4,410 | 19,950 | |

| −15 | − | − | 17 | − | + | 0 | 28,400 | 85,080 | |

| 0 | F | + | 12 | + | + | >200 | 30,600 | ND | |

| +3 | F | + | 6 | − | + | >200 | 8,165 | 733,870 | |

| +6 | F | + | 8 | − | + | 58 | 4,710 | 25,770 | |

| +10 | F | + | 10 | − | + | 4 | 14,300 | ND | |

| +27 | F | + | 20 | − | + | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +57 | F | + | 46 | − | + | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +92 | F | + | 62 | + | − | 0 | <400 | ND | |

| +152 | F | + | 58 | − | + | 1 | <400 | <900 | |

| +202 | F | + | ND | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +212 | F | + | 43 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +220 | F | + | 67 | − | − | 0 | <400 | 1,300 | |

| +270 | F | + | 60 | − | + | >200 | 16,900 | 60,960 | |

| 10 (Pn) | −244 | − | − | 8 | − | + | 21 | 1,097 | 7,570 |

| −125 | − | − | 3 | + | + | 57 | 14,500 | 49,140 | |

| −95 | − | + | 4 | + | + | 150 | 28,900 | 337,300 | |

| −70 | − | + | 4 | + | + | >200 | 74,700 | ND | |

| −10 | − | + | 6 | − | + | 162 | 49,500 | 669,750 | |

| 0 | F | + | ND | + | + | >200 | 65,300 | 911,000 | |

| +5 | F | + | 3 | − | + | 3 | 7,800 | ND | |

| +9 | F | + | ND | − | + | 0 | 13,600 | ND | |

| +40 | F | + | 9 | + | + | 157 | 24,800 | 31,450 | |

| +44 | F | + | ND | − | − | 0 | 898 | ND | |

| 11 (R) | −265 | F | − | 6 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 |

| −185 | F | + | 8 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| −130 | F | + | 5 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| −100 | F | + | 5 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| −50 | F | + | 2 | − | − | 2 | <400 | <900 | |

| 0 | F | + | 2 | − | + | 15 | 7,440 | 5,600 | |

| +15 | F | + | 4 | − | − | 6 | 3,560 | <900 | |

| +62 | F | + | 3 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +92 | F | + | 7 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| 12 (D) | −130 | − | − | 23 | − | + | 35 | 875 | 17,290 |

| −110 | − | − | 22 | − | + | 31 | 1,140 | 49,620 | |

| −60 | − | − | 29 | − | − | 5 | <400 | 2,760 | |

| 0 | F | + | 17 | − | − | 155 | <400 | 16,280 | |

| +7 | F | + | 25 | + | + | 95 | 1,720 | 107,010 | |

| +10 | F | + | 31 | − | − | 17 | <400 | <900 | |

| +17 | F | + | 84 | − | + | 0 | 663 | 1,690 | |

| +47 | F | + | 38 | − | − | 24 | 678 | 4,780 | |

| +122 | F | + | 111 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| +182 | F | + | 196 | − | − | 0 | <400 | <900 | |

| 13 (R) | −15 | − | − | 1 | + | + | >200 | 107,000 | 1,414,000 |

| 0 | F | − | 4 | − | + | >200 | 75,100 | 219,930 | |

| +4 | F | − | 5 | + | + | >200 | 88,300 | 928,500 | |

| +8 | F | − | 4 | + | + | >200 | 20,000 | 203,370 | |

| +14 | F | − | 3 | − | + | >200 | 44,500 | 134,500 | |

| +28 | F | + | 1 | + | + | >200 | 84,900 | 1,414,000 | |

| +43 | F | + | 3 | − | + | >200 | 65,900 | 199,600 | |

| 13 | +45 | F | + | 3 | + | + | >200 | 76,000 | 1,290,210 |

| +63 | F | + | 1 | − | + | >200 | 95,700 | 632,750 | |

Abbreviations: R, CMV retinitis; D, CMV digestive disease; Pn, CMV pneumonia; G, ganciclovir; F, foscarnet; ND, not done; c, copies.

The quantitative results of the pp65 Ag assay and CMM (on the basis of one sample per patient) were significantly correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.87).

bDNA CMV 2.0 and pp65 Ag assay.

By use of the 1+ cell threshold for the pp65 Ag assay, the results for 91% of the samples were highly concordant; 74% were negative and 17% were positive. The positive-negative and negative-positive discordance rates were 8 and 1%, respectively (Table 1).

By use of the 5+ cell threshold for the pp65 Ag assay, the results for 95% of the samples were highly concordant; 81% were negative and 14% were positive. The positive-negative and negative-positive discordance rates were 0.5 and 4%, respectively (Table 1).

The quantitative results of the pp65 Ag assay and bDNA CMV 2.0 (on the basis of one sample per patient) were significantly correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.94).

Excellent agreement was found among the results of the CMM test or bDNA CMV 2.0 and those of conventional assays (CMV viremia and pp65 Ag assays). The agreement between the results of CMM and bDNA CMV 2.0 and those of the pp65 Ag assay increased when a diagnostic threshold of 5+ cells rather than 1+ cell per 2 × 105 PBLs was applied.

CMM and bDNA CMV 2.0.

The limits of detection for CMM and bDNA CMV 2.0 were 400 copies/ml of plasma and 900 copies/106 PBLs, respectively. The results of bDNA CMV 2.0 and CMM were highly concordant (95%); 81% of the samples were negative and 14% were positive, with positive-negative and negative-positive discordance rates of 5 and 1%, respectively (Table 1).

The quantitative results of these tests (on the basis of one sample per patient) were significantly correlated (Spearman ρ = 0.92).

CMM and P-AMP.

By use of the quantitative CMM (limit of detection, 400 copies/ml) and the qualitative P-AMP (limit of detection, 1,000 copies/ml), the concordance rate was 97% with plasma specimens; 84% of the specimens were negative and 13% were positive. The positive-negative and negative-positive discordances were 3% (Table 1). For all the six CMM-positive but P-AMP-negative specimens, the CMV loads were often low (patients 1, 5, 10, 11, 12; see Table 4) and P-AMP-positive results were observed before and/or after the P-AMP-negative discordant results were observed.

In summary, it should be noted that comparable concordance rates were observed between assays that assess the CMV load in the cellular compartment (pp65 Ag assay versus bDNA CMV 2.0) and between those that assess the CMV load in PBLs versus plasma (bDNA or pp65 Ag assay versus P-AMP or CMM). Most cases of discordance between CMV assay results were observed at the time that active CMV replication could be measured or during CMV clearance under anti-CMV therapy.

Usefulness of assays for diagnosis of CMV disease and longitudinal analysis of CMV load. (i) Diagnostic value for CMV disease.

The sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative predictive values of conventional and molecular assays were calculated on the basis of the data obtained for the 58 subjects (Table 3). The ability of the assays to identify CMV disease in HIV-infected patients was assessed by using the last blood sample from CMV disease-free patients and the blood sample drawn at the time of clinical CMV disease diagnosis. When CMV disease was documented at the time of inclusion in the study, the blood sample that was analyzed was drawn 24 h before the initiation of anti-CMV therapy. The prevalence of CMV disease during the study period was 22.4% (13 of 58 patients). The highest specificity and positive predictive value were obtained by the SV assay, the pp65 Ag assay with the 5+ cell threshold, P-AMP, and CMM, whereas the highest sensitivity and negative predictive value were obtained by the pp65 Ag assay (1+ and 5+ cell thresholds) and bDNA CMV 2.0 (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference among performance of the assays.

TABLE 3.

Diagnostic values of conventional and molecular assays for CMV diseasea

| CMV assay (positivity threshold) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SV assay | 38.5 | 100 | 100 | 84.9 |

| pp65 Ag assay (1+ cell) | 92.3 | 93.3 | 80 | 97.8 |

| pp65 Ag assay (5+ cells) | 92.3 | 100 | 100 | 97.8 |

| bDNA CMV 2.0 (900 c/106 PBLs) | 92.3 | 97.8 | 92.3 | 97.8 |

| P-AMP CMV (1,000 c/ml) | 76.9 | 100 | 100 | 93.8 |

| CMM (400 c/ml) | 84.6 | 100 | 100 | 95.7 |

Data are for 58 HIV-positive and CMV-positive patients, including 13 patients with CMV disease. Abbreviations: PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; c, copies.

(ii) Longitudinal analysis.

Fifty-eight patients were monitored for 2 years. They were divided into four groups according to their CMV parameter patterns.

Group 1 included 25 patients with repeated negative results by all assays; none of them had developed CMV disease during this study. For their last blood samples, their median (25th to 75th percentile) CD4+ T-cell counts and number of HIV RNA copies were 113 (36 to 144)/μl and 8,700 (500 to 48,800)/ml, respectively.

Group 2 included 10 patients who had only one low-positive assay result during follow-up. The median (25th to 75th percentile) CD4+ T-cell counts and number of HIV RNA copies were 105 (92 to 121)/μl and 26,900 (800 to 102,600)/ml, respectively. Antiretroviral triple therapy with a PI was prescribed for all of patients. Patient 4 (Table 4) was the only one among them who developed CMV disease (retinitis), and this was detected 60 days after the finding of a positive pp65 Ag assay result (pp65 Ag assay with 2+ cells/2 × 105 PBLs; CD4+ T-cell count, 45/μl).

Group 3 included 11 patients who had positive results by at least two tests but who did not develop CMV disease; all of them received a PI and 5 also took foscarnet for Kaposi’s sarcoma (median CD4+ T-cell count, 62/μl [25th to 75th percentiles, 24 to 184 cells/μl]; median number of HIV RNA copies, 600/ml [25th to 75th percentiles, 500 to 2,450 copies/ml]).

Group 4 included 12 patients (Table 4, except patient 4) who had strongly positive results by most tests. All these patients developed CMV disease (median CD4+ T-cell count, 65/μl [25th to 75th percentiles, 3.5 to 29.5 cells/μl]); median HIV RNA copies, 164,240/ml [25th to 75th percentiles, 47,700 to 716,900 copies/ml]).

Sequential blood samples from these 13 subjects were analyzed before they developed CMV disease or from the first day of CMV disease (Table 4). CMV load was evaluated longitudinally.

The delay between the first positive sample by each assay and CMV disease diagnosis is presented in Table 5. Taking into account the measures of the entire follow-up for the 58 patients, the performances of each assay were calculated for patients with at least one positive result prior to the diagnosis of CMV disease or until the last follow-up for patients without CMV disease versus patients with no positive results. The highest specificity and positive predictive value were obtained by assays with plasma, i.e., P-AMP and CMM, whereas the highest sensitivity and NPV were obtained by quantitative tests with PBLs, i.e., the pp65 Ag assay and bDNA CMV 2.0 (Table 5). There were no statistically significant differences among the performances of the assays. At the time of CMV disease diagnosis, the median (25th to 75th percentile) CMV DNA loads measured by the pp65 Ag assay, CMM, and bDNA CMV 2.0 were 172 (20 to >200) positive cells/2 × 105 PBLs, 9,070 (1,530 to 52,400) copies/ml, and 108,500 (16,280 to 219,930) copies/1 × 106 PBL, respectively. CMV load showed a statistically significant but weak rank correlation with the CD4+ count (Spearman ρ = −0.63 and P <1 × 10−4 by the pp65 Ag assay with 5+ cells, ρ = −0.53 and P < 7 × 10−4 by CMM, and ρ = −0.56 and P < 3 × 10−4 by bDNA CMV 2.0) and with HIV RNA load (Spearman ρ = 0.52 and P = 2 × 104 by the pp65 Ag assay with 5+ cells, ρ = 0.37 and P = 0.01 by CMM, and ρ = 0.44 and P = 0.002 by bDNA CMV 2.0).

TABLE 5.

Assay performances by consideration of entire follow-up of the 58 patientsa

| CMV assay (positivity threshold) | Day of first positive sample before CMV disease diagnosis (25th to 75th percentile) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pp65 Ag assay (1+ cell) | 124 (68–225) | 100 | 55.5 | 39.4 | 100 |

| pp65 Ag assay (5+ cells) | 74 (29–147) | 92.3 | 75.6 | 52.2 | 97.1 |

| P-AMP CMV (1,000 c/ml) | 46 (15–133) | 84.6 | 91.1 | 73.3 | 95.3 |

| CMM (400 c/ml) | 46 (15–102) | 92.3 | 86.7 | 66.7 | 97.5 |

| bDNA CMV 2.0 (900 c/106 PBLs) | 125 (34–190) | 92.3 | 73.3 | 52.2 | 97.1 |

Abbreviations: PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; c, copies. The performances for each assay were estimated after defining a positive result as at least one positive measure prior to the diagnosis of CMV disease or until the last follow-up for patients without CMV disease and a negative result when all measures remained negative during the entire follow-up.

The CMV load increased before CMV disease diagnosis and declined after anti-CMV treatment initiation (Table 4). The 13 patients who developed CMV disease received curative anti-CMV treatment with ganciclovir or foscarnet. Among them, the 11 who were clinically cured had decreased CMV loads, as assessed by the three quantitative assays (CMM, bDNA CMV 2.0, and the pp65 Ag assay with 5+ cells), whereas the 2 nonresponders (patients 2 and 13; Table 4) failed to improve under anti-CMV treatment and their CMV loads remained high by these three assays. Monitoring of the CMV load in cured patients was useful for prediction of relapse of CMV disease, as shown by the data obtained for patients 7 and 9.

(iii) Selection of a threshold.

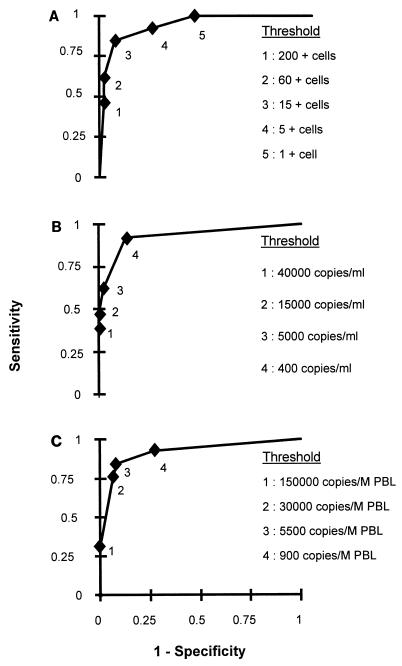

To identify subjects with a higher risk of development of symptomatic infection, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of CMV disease diagnosis by use of threshold value corresponding approximately to the first CMV load tercile, the median, and the second CMV load tercile. The optimal threshold, which allowed us to obtain the best compromise in sensitivity and specificity, was sought by using a receiver operating characteristic curve. This analysis showed that levels of 15 positive cells/105 PBLs (Fig. 1A), 400 copies/ml (Fig. 1B), and 5,500 copies/106 PBLs (Fig. 1C) by the pp65 Ag assay, CMM, and bDNA CMV 2.0, respectively, were the best thresholds. When 15 positive cells/105 PBLs was used as the threshold for the pp65 Ag assay, 11 (84.6%) of the 13 symptomatic subjects would have been identified, along with 3 of the 45 asymptomatic subjects. When 400 copies/ml, which is the limit of detection defined by the manufacturer, was used as the threshold for CMM, 12 (92.3%) of the 13 symptomatic subjects would have been identified, along with 6 of the 45 asymptomatic subjects. When 5,500 copies/106 PBLs was used as the threshold for bDNA CMV, 11 (84.6%) of the 13 symptomatic subjects would have been identified, along with 4 of the 45 asymptomatic subjects.

FIG. 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for CMV disease diagnosis by examining possible thresholds for pp65 Ag assay (A), CMM (B), and bDNA CMV 2.0 (C).

DISCUSSION

Human CMV infection represents a major infectious complication in immunocompromised patients. Methods have been developed to detect and/or quantitate the virus or its components in blood, for example, blood culture, pp65 Ag, PBL, and plasma DNAemia and mRNAemia assays. The availability of more sensitive tests means that it is possible to have positive laboratory assay results far before the onset of clinical symptoms. Identification of this asymptomatic stage is important because initiation of preemptive therapy at this time might prove beneficial. In addition, some investigators have found CMV DNA levels in plasma or PBLs to be reliable markers of replication in disseminated human CMV infections (4, 14, 32, 35). However, earlier protocols were poorly standardized, and only now are test results becoming comparable because of commercially available assays. In our study, we compared two conventional assays (the CMV viremia and pp65 Ag assays) and new molecular CMV assays with both PBLs (bDNA CMV 2.0 [Chiron]) and plasma specimens (P-AMP and CMM [Roche]).

The practical significance of the SV assay has been limited by its relatively low sensitivity and the rapid loss of integrity of stored specimens.

Direct detection of pp65 Ag in blood provides a more rapid means of diagnosis of CMV infection (23), is a more sensitive method, and can detect latent or active CMV infection. It also requires immediate specimen processing, PBL preparation, and time-consuming scanning of slides with a fluorescence microscope.

Direct detection of CMV DNA in plasma by PCR is also a sensitive method for identification of CMV infection and systemic CMV disease (7, 29). CMM and P-AMP are plasma PCR-based assays and are more rapid and technically easier for large-scale screening, and they can be performed for patients with low blood cell counts.

Direct detection of CMV DNA in PBLs by the bDNA CMV 2.0 assay requires PBL preparation and is easy to perform, and the absence of amplification makes the assay less susceptible to contamination or inhibition than PCR testing.

Whether PBLs, plasma, or whole blood is the best specimen for CMV DNA detection in blood has not yet been definitively determined.

The assays evaluated in the present study recognize different virus components (CMV DNA or CMV phosphoprotein [pp65]) and virus in different blood compartments (plasma or cells). The CMM assay quantitates the plasma CMV DNA content produced and released by active replication in infected cells, whereas bDNA CMV 2.0 measures CMV DNA in PBLs, either latent or productive PBLs. The plasma DNA level may reflect the DNA from multiple pools, including those of endothelial cells (17, 25), the reticuloendothelial system, and circulating PBLs (2, 14). During CMV reactivation, CMV DNA is first detected in PBLs, and this is followed by detection of CMV pp65 Ag. The inability to detect CMV DNA in plasma during this early period is likely due to an extremely low viral load, rapid phagocytosis, and/or the sensitivities of the assays used. During the different stages of progressive infection (2, 33), both phagocytosis and active replication seem to take place in PBLs, which could explain the observed temporal patterns of virus obtained in different blood compartments.

In our study, the quantitative results obtained with plasma (CMM) and PBLs (bDNA CMV 2.0) were highly significantly correlated (ρ = 0.92). A positive correlation has already been reported during acute visceral CMV disease (7, 29). Similarly, Zipeto et al. (37), Gerna et al. (14), and Boivin et al. (3, 4) have shown that the presence of CMV DNA in the plasma of HIV-positive patients usually reflected the presence of higher levels of CMV DNA in the corresponding PBLs. We observed few discordant results, and in most cases, when the results of two assays did not agree, the positive one was weakly positive while the other one was negative. Comparing a homemade PCR with PBLs and P-AMP with plasma, Boivin et al. (5) also found that discordant results were associated with low viral loads. In addition, when we observed discordant results, the negative assay has often been positive previously and/or became positive later during the course of the CMV infection. Finally, when all the results were taken into consideration, the results of the assays were closely correlated.

For the diagnosis of CMV disease, the assays performed with PBLs (the pp65 Ag assay and bDNA CMV 2.0) were the most sensitive, followed by PCRs with plasma (P-AMP and CMM). Specificity and positive predictive value were high for all tests (>93 to >80%, respectively). These results are in agreement with those of other studies (1, 6, 22, 30). However, two cases of CMV retinitis occurred when the CMV load was low (patient 1) or not detectable (patient 4). Indeed, several studies have shown that 5 to 44% of patients with CMV disease do not test positive for viremia at the time of diagnosis (1, 10, 18, 28, 34), suggesting that the systemic CMV load is not the only factor that influences the development of CMV retinitis (27).

The 13 patients with CMV disease were treated, and CMV load measurement was useful for the evaluation of treatment efficacy. In most cases, kinetic profiles of the CMV loads paralleled the clinical outcome, and relapse of CMV disease was again predicted when the CMV load increased. For some patients who benefited from RTNI triple therapy with a PI, a role of the increased CD4+ T-cell counts concomitant with specific anti-CMV therapy to help clear the CMV load cannot be excluded (patients 1, 4, 5, 7, and 12).

One of the major objectives of the study was to verify the hypothesis that quantitative molecular assays could be used to predict the development of CMV disease. In fact, since the introduction of RTNI triple therapy with a PI, the incidence of CMV disease has dramatically decreased, which explains the low number of CMV events observed. Nevertheless, because nine patients developed CMV disease during follow-up, it was possible to describe CMV load kinetics during the period preceding the onset of CMV disease. The progression from biological detection to disease was evaluated differently, depending on the assay. CMV was first detected in PBLs by bDNA CMV 2.0 (125 days prior to clinical disease) and the pp65 Ag assay (124 days with a 1+ cell threshold). In a previous study, Francisci et al. (11) found the pp65 Ag assay to be positive for all patients 4 months before overt CMV disease. The CMV DNA in plasma became positive later: 46 days prior to disease for both the qualitative (P-AMP) and quantitative (CMM) assays. Boivin et al. (5) also found that P-AMP gave positive results at least 48 days before the development of symptomatic CMV disease in a longitudinal analysis of HIV-infected patients. To predict CMV disease in our population, plasma PCR-based assays presented the highest specificity and positive predictive value, whereas the best sensitivities were obtained with PBL assays. Boeckh et al. (2) demonstrated for marrow transplant recipients that PBL PCR was the most sensitive test, followed by the pp65 Ag assay and plasma PCR. These advance warnings are highly pertinent for clinicians who might be able to initiate early therapy before the appearance of symptoms of CMV disease. The use of PBLs may be more appropriate when the CMV DNA load is low (during antiviral therapy) or when preemptive therapy is considered in a setting in which there is rapid progression from first detection to CMV disease, such as after allogeneic marrow transplantation. In contrast, quantitation of CMV in plasma provides enough information sufficiently early for HIV-infected individuals, in whom the progression from first detection of CMV DNA to disease can last several weeks or months.

Our data support the hypothesis that standardized assays, like P-AMP, CMM, and bDNA CMV 2.0, could be used to define a high-risk population for which trials of prophylactic or preemptive therapy for CMV could be designed. Nonetheless, several points must be emphasized. CMV assays were occasionally positive (groups 2 and 3) for patients who did not develop CMV disease. These subjects received an RTNI modified by introduction of a PI, which led to increased CD4+ T-cell counts and decreased CMV loads without anti-CMV therapy. Moreover, we must consider that several patients in group 3 received foscarnet for Kaposi’s sarcoma. These events make us wonder whether these subjects would have developed CMV disease in the absence of these therapies. They also demonstrate that CD4+ T-cell counts must be considered when choosing a therapeutic strategy in patients with coinfected HIV and CMV. However, the CD4+ T-cell count at which testing should be initiated and the optimal frequency of testing remains to be determined. Even if high-risk patients can be identified, it is still unknown whether preemptive strategies would be effective and, if so, what threshold value of which assay should be chosen to initiate therapy. Thus, it will be necessary to determine quantitative thresholds for the different assays to predict the appearance of the CMV disease.

In our analysis, thresholds of 15 positive cells/105 PBLs for the pp65 Ag assay, 400 copies/ml for CMM, and 5,500 copies/106 PBLs for bDNA CMV 2.0 allowed us to obtain the best compromise in sensitivity and specificity to identify subjects with a higher risk of development of CMV disease. This could be used prospectively for patient management. An alternative approach would be to repeat the PCR at weekly intervals for patients whose values are still below the threshold, with the initiation of treatment when the threshold is exceeded. These threshold values identified in the present population coinfected with HIV and CMV require validation in other studies.

Since the incidence of CMV disease has decreased with the use of highly active combination antiretroviral therapies, the identification of patients who might or might not benefit from preemptive therapy is essential. A positive assay could lead to different therapeutic strategies like preemptive anti-CMV therapy or modification of the anti-HIV therapy, depending on the CMV load, the CD4+ T-cell count, and the plasma HIV-1 load.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients who gave their consent and who participated in this study, Chiron Corporation and Roche Diagnostics for supplying the kits, M. H. Shrive and D. Jacquemart for excellent technical assistance, D. Theophile for helpful discussions, and J. Jacobson for editing our English text.

I. Pellegrin and I. Garrigue contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bek B, Boeckh M, Lepenies J, Bieniek B, Arasteh K, Heise W, Deppermann K M, Bornhoft G, Stöffler-Meilicke M, Schuller I, Höffken G. High-level sensitivity of quantitative pp65 cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigenemia assay for diagnosis of CMV disease in AIDS patients and follow-up. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:457–459. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.457-459.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeckh M, Hawkins G, Myerson D, Zaia J, Bowden R A. Plasma polymerase chain reaction for cytomegalovirus DNA after allogeneic marrow transplantation: comparison with polymerase chain reaction using peripheral blood leukocytes, pp65 antigenemia, and viral culture. Transplantation. 1997;64:108–113. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boivin G, Chou S, Quirk M R, Erice A, Jordan M C. Detection of ganciclovir resistance mutations and quantitation of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in leukocytes of patients with fatal disseminated CMV disease. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:523–528. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boivin G, Handfield J, Toma E, Murray G, Lalonde R, Bergeron M G. Comparative evaluation of the cytomegalovirus DNA load in polymorphonuclear leukocytes and plasma of human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:355–360. doi: 10.1086/514190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boivin G, Handfield J, Toma E, Murray G, Lalonde R, Tevere V J, Sun R, Bergeron M G. Evaluation of the AMPLICOR cytomegalovirus test with specimens from human immunodeficiency virus-infected subjects. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2509–2513. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2509-2513.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen E F, Sabin C A, Wilson P, Griffiths P D, Davey C C, Johnson M A, Emery V C. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) viraemia detected by polymerase chain reaction identifies a group of HIV-positive patients at risk of CMV disease. AIDS. 1997;11:889–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brytting M, Xu W, Warren B, Sunqvist V-A. Cytomegalovirus detection in sera from patients with active CMV infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1937–1942. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.8.1937-1941.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control. Classification for human T-lymphotropic virus type III/lymphadenopathy-associated virus. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1987;36:3S–15S. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 1993;41:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dodt K K, Jacobsen P H, Hofmann B, Meyer C, Kolmos H J, Skinhoj P, Norrild B, Mathiesen L. Development of cytomegalovirus (CMV) disease may be predicted in HIV-infected patients by CMV polymerase chain reaction and the antigenemia test. AIDS. 1997;11:F21–F28. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199703110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francisci D, Tosti A, Preziosi R, Baldelli F, Stagni G, Pauluzzi S. Role of antigenemia assay in the early diagnosis and prediction of human cytomegalovirus organ involvement in AIDS patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;14:498–503. doi: 10.1007/BF02113427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallant J E, Moore R D, Richman D D, Keruly J, Chaisson R E. Incidence and natural history of cytomegalovirus disease in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus disease treated with zidovudine. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1223–1227. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gérard L, Leport C, Flandre P, Houhou N, Salmon-Céron D, Pépin J M, Mandet C, Brun-Vézinet F, Vildé J-L. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) viremia and the CD4+ lymphocyte count as predictors of CMV disease in patients infected with immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:836–840. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.5.836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerna G, Furione M, Baldanti F, Sarasini A. Comparative quantitation of human cytomegalovirus DNA in blood leukocytes and plasma of transplant and AIDS patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2709–2717. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2709-2717.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodrich J M, Mori M, Gleaves C A, Du Mond C, Cays M, Ebeling D F, Buhles W C, DeArmond B, Meyers J D. Early treatment with ganciclovir to prevent cytomegalovirus disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplant. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1601–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112053252303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gozlan J, Salord J M, Chouaid C, Duvivier C, Picard O, Meyohas M C, Petit J C. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) late mRNA detection in peripheral blood in AIDS patients: diagnostic value for HCMV disease compared with those of viral culture and HCMV DNA detection. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1943–1945. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1943-1945.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grefte A, van der Giessen M, van Son W, The T H. Circulating cytomegalovirus (CMV)-infected endothelial cells in patients with active CMV infection. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:270–277. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen K K, Ricksten A, Hofmann B, Norrild B, Olofsson S, Mathiesen L. Detection of cytomegalovirus DNA in serum correlates with clinical cytomegalovirus retinitis in AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1271–1274. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.5.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer-Konig U, Serr A, von Lear D, Kirste G, Wolff C, Haller O, Neumann-Haefelin D, Hufert F T. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early and late transcripts in peripheral blood leukocytes: diagnostic value in renal transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:705–709. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachl C, Todd J A, Kern D G, Sheridan P J, Fong M S J, Stempien M, Hoo B, Besemer D, Yeghiazarian T, Irvine B, Kolberg J, Kokka R, Neuwald P, Urdea M S. Rapid and precise quantification of HIV-1 RNA in plasma using branched DNA (bDNA) signal amplification assay. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1995;8:446–454. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199504120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel R, Smith T F, Espy M, Portela D, Wiesner R H, Krom R A F, Paya C V. A prospective comparison of molecular diagnostic techniques for the early detection of cytomegalovirus in liver transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1010–1014. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen L, Zipeto D, Wolitz R A, Dowling A, Efron B, Merigan T C. Risk for retinitis in patients with AIDS can be assessed by quantitation of threshold levels of cytomegalovirus DNA burden in blood. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1146–1155. doi: 10.1086/514106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revello M G, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Gerna G. Human cytomegalovirus infection: diagnosis by antigen and DNA detection. Rev Med Microbiol. 1994;5:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmon D, Lacassin F, Harzic M, Leport C, Perronne C, Bricaire F, Brun-Vézinet F, Vildé J-L. Predictive value of cytomegalovirus viraemia for the occurrence of CMV organ involvement in AIDS. J Med Virol. 1990;32:160–163. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890320306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salzberger B, Myerson D, Boeckh M. Circulating CMV-infected endothelial cells in marrow transplant patients with CMV disease and CMV infection. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:778–781. doi: 10.1086/517300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt G M, Horak D A, Niland J C, Duncan S R, Forman S J, Zaia J A. A randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus pulmonary infection in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1005–1011. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104113241501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shepp D H, Match M E, Ashraf A B, Lipson S M, Millan C, Pergolizzi R. Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B groups associated with retinitis in AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:184–187. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shinkai M, Bozzette S A, Powderly W, Frame P, Spector S A. Utility of urine and leukocyte cultures and plasma DNA polymerase chain reaction for identification of AIDS patients at risk for developing human cytomegalovirus virus disease. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:302–308. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spector S A, Merrill R, Wolf D, Dankner W M. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in plasma of AIDS patients during acute visceral disease by DNA amplification. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2359–2365. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2359-2365.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spector S A, Wong R, Hsia K, Pilcher M, Stempien M J. Plasma cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA load predicts CMV disease and survival in AIDS patients. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:497–502. doi: 10.1172/JCI1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Storch G A, Buller R S, Bailey T C, Ettinger N A, Langlois T, Gaudreault-Keener M, Welby P L. Comparison of PCR and pp65 antigenemia assay with quantitative shell vial culture for detection of cytomegalovirus in blood leukocytes from solid-organ transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:997–1003. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.997-1003.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The T H, van der Ploeg M, van der Berg A P, Vlieger A M, van der Giessen M, van Son W J. Direct detection of cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood leukocytes: a review of the antigenemia assay and polymerase chain reaction. Transplantation. 1992;54:193–198. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199208000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Lear D, Serr A, Meyer-Konig U, Kirste G, Hufert F T, Haller O. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early and late transcripts are expressed in all major leukocyte populations in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:365. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walmsley S, Mazzulli T, Krajden M. Long-term predictive value of a single cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA PCR assay for CMV disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:281–283. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.281-283.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zipeto D, Baldanti F, Zella D, Furione M, Cavicchini A, Milanesi G, Gerna G. Quantification of human cytomegalovirus DNA in peripheral blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes of immunocompromised patients by the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1993;44:45–56. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90006-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zipeto D, Revello M G, Silini E, Parea M, Percivalle E, Zavattoni M, Milanesi G, Gerna G. Development and clinical significance of a diagnostic assay based on polymerase chain reaction for detection of human cytomegalovirus DNA in blood samples from immunocompromised patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:527–530. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.527-530.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zipeto D, Morris S, Hong C, Dowling A, Wolitz R, Merigan T C, Rasmussen L. Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA in plasma reflects quantity of CMV DNA present in leukocytes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2607–2611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2607-2611.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]