Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to validate a Spanish version of the Prolapse and Incontinence Knowledge Questionnaire (PIKQ).

Methods:

Validation and reliability testing of the Spanish version of the PIKQ was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, a translation-back translation method by six bilingual researchers was utilized to generate a final Spanish translation. In the second phase, bilingual women were randomized to complete the Spanish or English version first, followed by the alternate language. Agreement between individual items from English and Spanish versions was assessed by percent agreement and kappa statistics. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) compared overall PIKQ scores and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and urinary incontinence (UI) subscores. To establish test-retest reliability, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients. In order to have a precision of 10% for 90% agreement, so that the lower 95% confidence interval would not be <80% agreement, 50 bilingual subjects were required.

Results:

Fifty-seven bilingual women were randomized and completed both versions of the PIKQ. Individual items showed 74–97% percent agreement, good to excellent agreement (kappa 0.6–0.89) for 9 items and moderate agreement (kappa 0.4–0.59) for 14 items between English and Spanish PIKQ versions. ICCs of the overall score and POP and UI subscores showed excellent agreement (ICC 0.81–0.91). Pearson’s correlation coefficients between initial and repeat Spanish scores were high: overall (r=0.87) and for POP (r=0.81) and UI subscores (r=0.77).

Conclusions:

A valid and reliable Spanish version of the PIKQ has been developed to assess patient knowledge about UI and POP.

Keywords: Pelvic floor disorder, Pelvic organ prolapse, Prolapse and Incontinence Knowledge Questionnaire (PIKQ), Spanish translation, Urinary Incontinence

Introduction

Women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDs) face great physical, financial and psychosocial burdens. Although one in four women in the U.S. suffer from at least one PFD,1 less than 50% seek medical attention.2 Factors that influence care-seeking include embarrassment,3 impact on quality of life4 and older age.5 Nonetheless, lack of knowledge regarding PFDs is the most commonly reported reason for not seeking treatment.6

Latinos will comprise about 30% of the U.S. population by the year 2060.7 PFD prevalence rates in Hispanic women range from 20–24%.1 Hispanic women have higher rates of urinary incontinence (UI),8 higher risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse (POP)9and are 4–5 times more likely to report prolapse symptoms than other minority groups.10 Poor health literacy and understanding of female anatomy may lead to inadequate PFD knowledge in Hispanic women.11 Latina women are also less willing to discuss PFD symptoms with family.12 These factors, combined with medical interpreter shortages, language difficulties,13 and concerns of immigration status,14 collectively influence care-seeking. Additional barriers include limited physician and interpreter knowledge and vocabulary when explaining PFDs in Spanish,15,16 and clinician time constraints restricting counseling and assessment of patient understanding.17 Nevertheless, Latina women are willing to undergo further evaluation and treatment for their PFDs, especially if the information is provided in Spanish.18

The Prolapse and Incontinence Knowledge Questionnaire (PIKQ) is a validated instrument developed to identify patient knowledge regarding POP and UI.19 The PIKQ has identified racial disparities in women’s PFD knowledge.20 However, there is no validated Spanish version of the PIKQ. The creation of a Spanish PIKQ has the potential of exposing knowledge gaps among Spanish-only and Spanish-preferred speaking women. Educating this growing population in a culturally appropriate manner about these conditions and treatment options would have significant societal impact. The objective of this study was to develop a valid and reliable Spanish version of the PIKQ.

Materials and Methods

Johns Hopkins University institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. The PIKQ is a 24-item condition-specific questionnaire that consists of 2 knowledge subscales: questions concerning POP (score range 0–12) and UI (score range 0–12).19 Each item is given a score of 1 if answered correctly and 0 if answered incorrectly. Women were given a score of 0 if they answered “I don’t know” or “No lo sé” presuming a lack of knowledge.

Validation and reliability testing of the Spanish version of the questionnaire was conducted in two phases. In the first phase, a translation-back translation method was utilized to generate a final Spanish translation of the PIKQ reflective of the original version’s meaning and content. Three bilingual medical researchers independently developed three Spanish translated versions of the PIKQ. Three additional bilingual medical researchers then independently back translated these three Spanish versions into English. Bilingual medical researchers were of diverse Hispanic backgrounds. The three newly created English versions were then each independently compared to the original English PIKQ by seven separate medical investigators to ensure comparability of language and similarity of interpretation. The “comparability of language” refers to the formal similarity of words, phrases and sentences.21 The “similarity of interpretability” refers to the degree to which two items produce the same response even if the wording is different.21 Each question in each English back-translated version was compared to each question in the original English PIKQ on the “comparability of language” and “similarity of interpretability” criteria using a 7-point anchored Likert scale, with 1 being extremely comparable or extremely similar, and 7 being not at all comparable or not at all similar.21 The final Spanish version of the PIKQ was the version that corresponded to the overall best rated (lowest score) back-translated English version out of the three (Appendix A). The final Spanish version was assessed for readability using the Crawford readability formula,22 Fernández Huerta readability score23 and Inflesz readability scale.24

In the second phase of the study, women recruited from the general population who met inclusion criteria were randomized to complete either the final Spanish version or the original English version of the PIKQ first, followed by the alternate language version. All women provided verbal informed consent. Inclusion criteria included: women age 18 years and older, self-reported fluency in reading and speaking both English and Spanish. Women were excluded if they had previously completed the PIKQ. Participants provided personal information regarding age, country/place of origin, primary language spoken (>50% of the time), and highest level of education. In order to have a precision of 10% for 90% agreement, so that the lower 95% confidence interval would not be less than 80% agreement, at least 50 bilingual subjects were required. 90% agreement was chosen in order to create a useful instrument with a stringent level of agreement between English and Spanish versions of the questionnaire.

Randomization was assigned by a random number table in blocks of 2, 4, 6 and 8 via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) at enrollment.25 Study data were collected and managed using REDCap tools. To establish test-retest reliability, women were asked to repeat the Spanish PIKQ which was re-administered 1–2 weeks later. Participants were given the choice of completing questionnaires via two survey modes: telephone or emailed links.

Descriptive statistics were used to report participant characteristics. Agreement between individual question items from the PIKQ English and Spanish versions was assessed by percent agreement and kappa statistics. While percent agreement is the simplest measure of interrater agreement and can be used with any type of measurement scale, we also calculated Kappa agreement, which takes into account agreement by chance.26 Kappa scores reflect agreement as: ≤0.2 poor, 0.21–0.4 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.8 good/substantial, ≥0.81 excellent/near perfect.26,27 Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated to compare the overall PIKQ score and POP and UI subscores between English and Spanish versions. ICCs reflect agreement as: 0.41–0.6 moderate, 0.61–0.8 good and ≥0.81 excellent.28 Paired t-tests were used to evaluate differences in scores for the overall PIKQ and POP and UI subscales between English and Spanish versions. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to evaluate internal consistency of the Spanish PIKQ; internal consistency was deemed acceptable with Cronbach’s alpha of ≥0.6.29 Criterion validity was established by two-sample t-tests examining total score differences by education level.19 To determine test-retest reliability, Pearson’s correlation coefficients and ICCs were calculated for initial and repeat Spanish scores. Two-sample t-tests were utilized to evaluate differences in mean scores between the two survey modes. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata/SE 15.1 (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In the first phase of the study, compared with the original English PIKQ, individual question items in the overall best rated back-translated English version had “comparability of language” scores ranging from 1.14–2.86 indicating excellent comparability. “Similarity of interpretability” scores ranged from 1.14–3 indicating moderate to excellent interpretability. According to the Crawford readability formula,22 Fernández Huerta readability score23 and Inflesz readability scale,24 the corresponding Spanish version was written at a fifth-grade level and described as “easy” or “quite easy” to read.

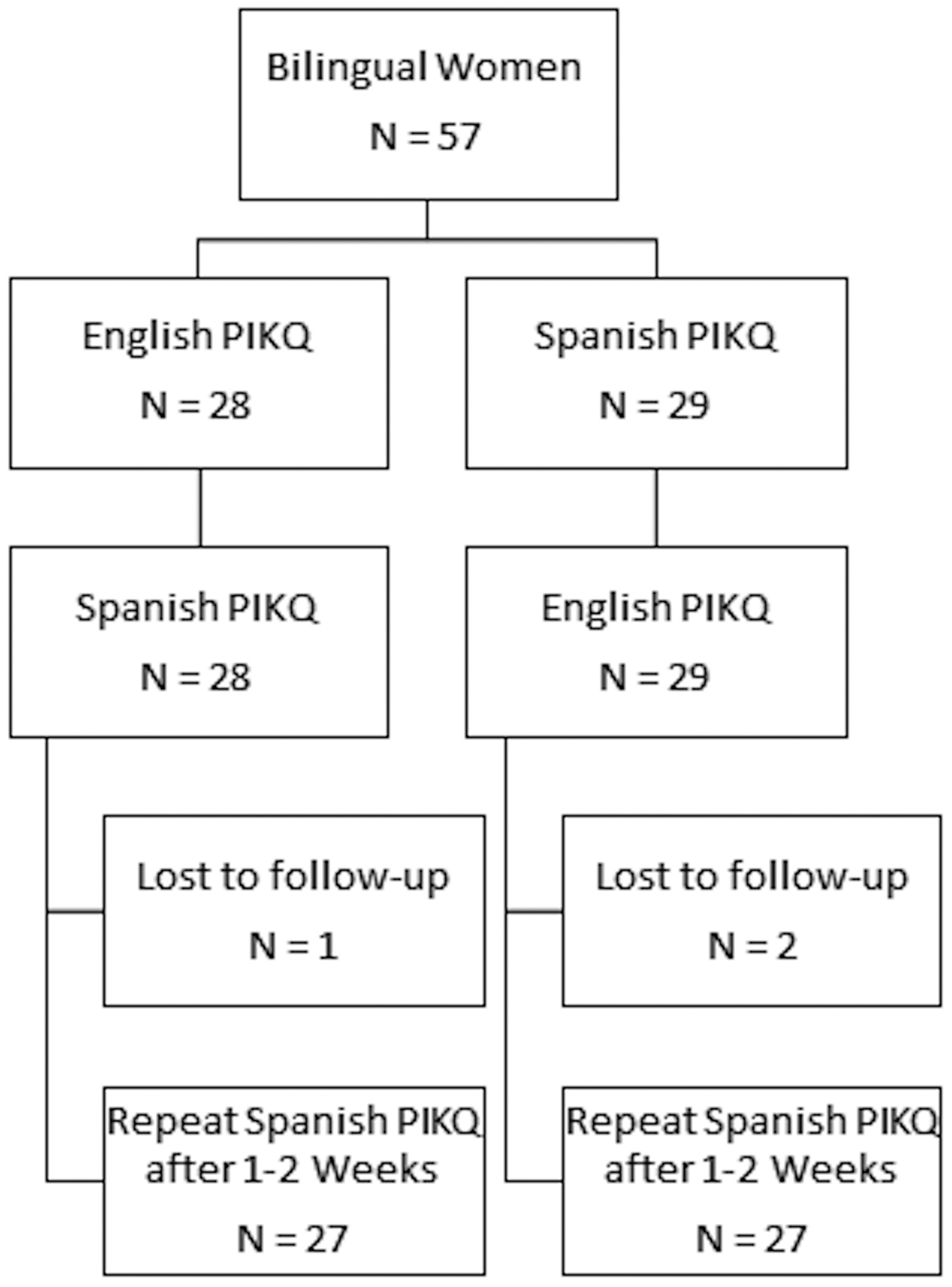

In the second phase of the study, 57 bilingual women were consented, randomized and completed all items from the final Spanish and English versions of the PIKQ (Figure 1). The mean age was 32 years (SD 9). Women were representative of diverse Hispanic backgrounds including 10 Latin American countries, the U.S. and Spain. 42% considered both Spanish and English their primary language and 54% had some college-level education (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Randomization of Bilingual Study Participants

PIKQ: Prolapse and Incontinence Knowledge Questionnaire

Table 1.

Study Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Participants, n (%) (N=57) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 32 (9) |

| Place/Country of Origin | |

| Dominican Republic | 14 (25) |

| United States | 12 (21) |

| El Salvador | 7 (12) |

| Mexico | 6 (10) |

| Peru | 3 (5) |

| Honduras | 3 (5) |

| Venezuela | 3 (5) |

| Guatemala | 2 (4) |

| Spain | 2 (4) |

| Colombia | 2 (4) |

| Puerto Rico | 1 (2) |

| Ecuador | 1 (2) |

| Nicaragua | 1 (2) |

| Primary Language | |

| English | 14 (25) |

| Spanish | 19 (33) |

| Both | 24 (42) |

| Education Level | |

| High School | 7 (12) |

| College | 31 (54) |

| Graduate School | 19 (33) |

The answers to each of the 24 individual question items from the PIKQ showed 74–97% percent agreement between the original English and final Spanish versions. Answers to the English and Spanish versions of 12 of the individual question items demonstrated good to excellent agreement with kappas 0.60–0.93, while the answers to 11 of the remaining 12 question items showed moderate agreement with kappas 0.41–0.57. In these 11 questions, although the kappas only demonstrated a moderate level of agreement, as most participants responded with the same answers to these questions (≥74%), the high concentration of the same responses and the corresponding lack of variation in responses affects the calculated kappa estimates. One remaining item, which showed 97% percent agreement, but no agreement with kappa (−0.02) was a question on the POP subscale which described the diagnosis of POP by a doctor examining the patient. For this question, 55 of 57 participants responded with the same answer on the English PIKQ and the same equivalent answer on the Spanish PIKQ (“agree”, “estoy de acuerdo”, respectively), which resulted in a negative value on the kappa estimate.

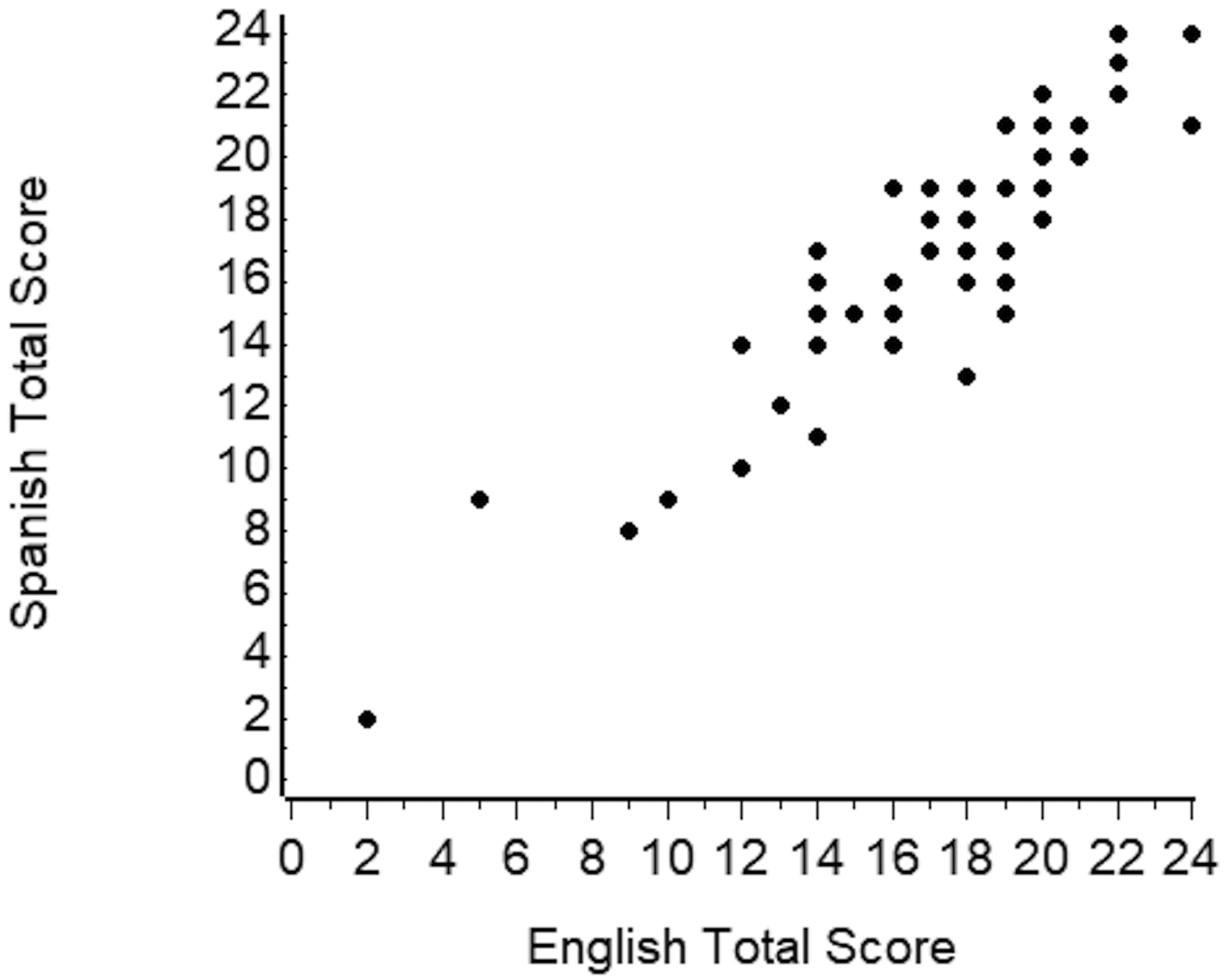

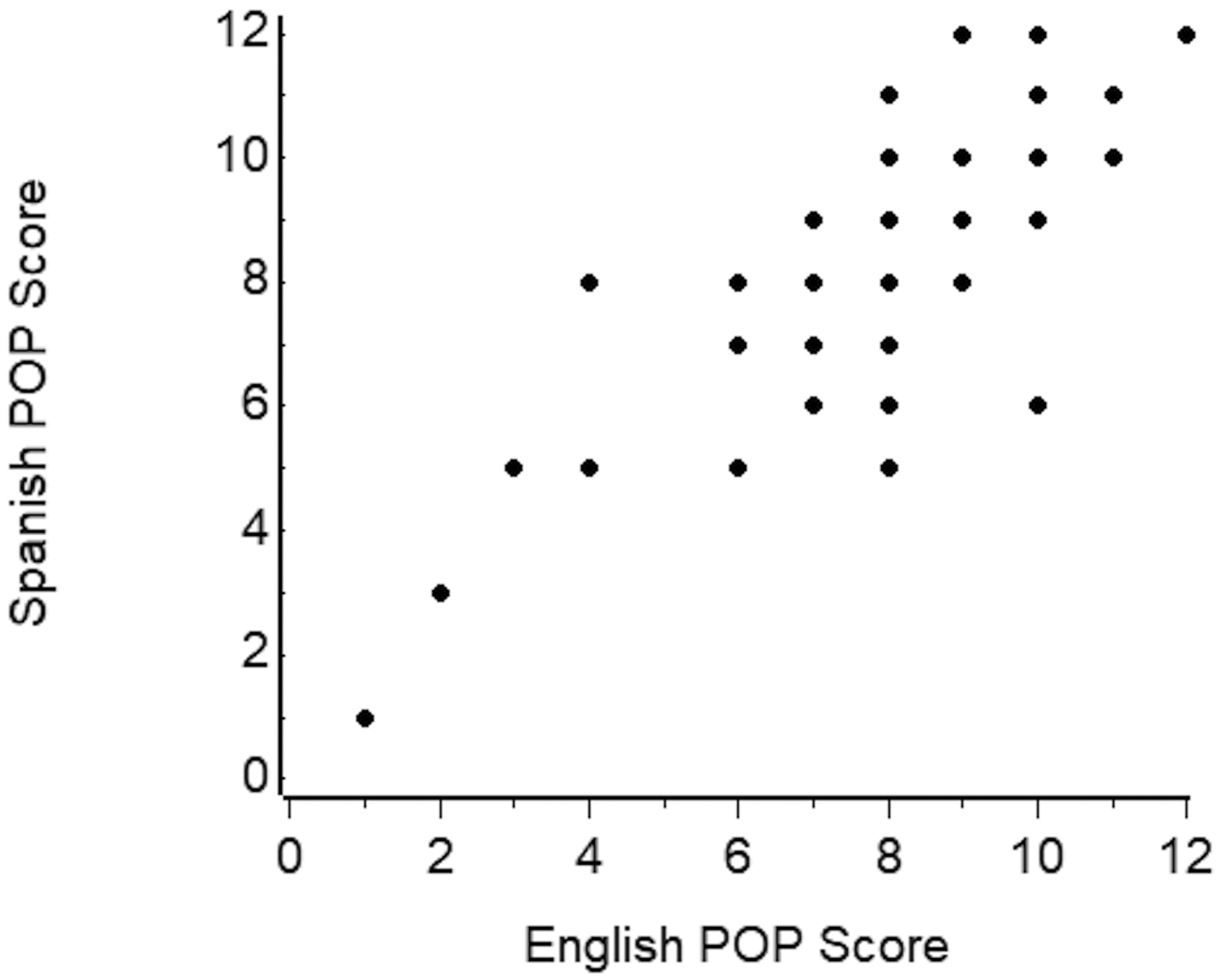

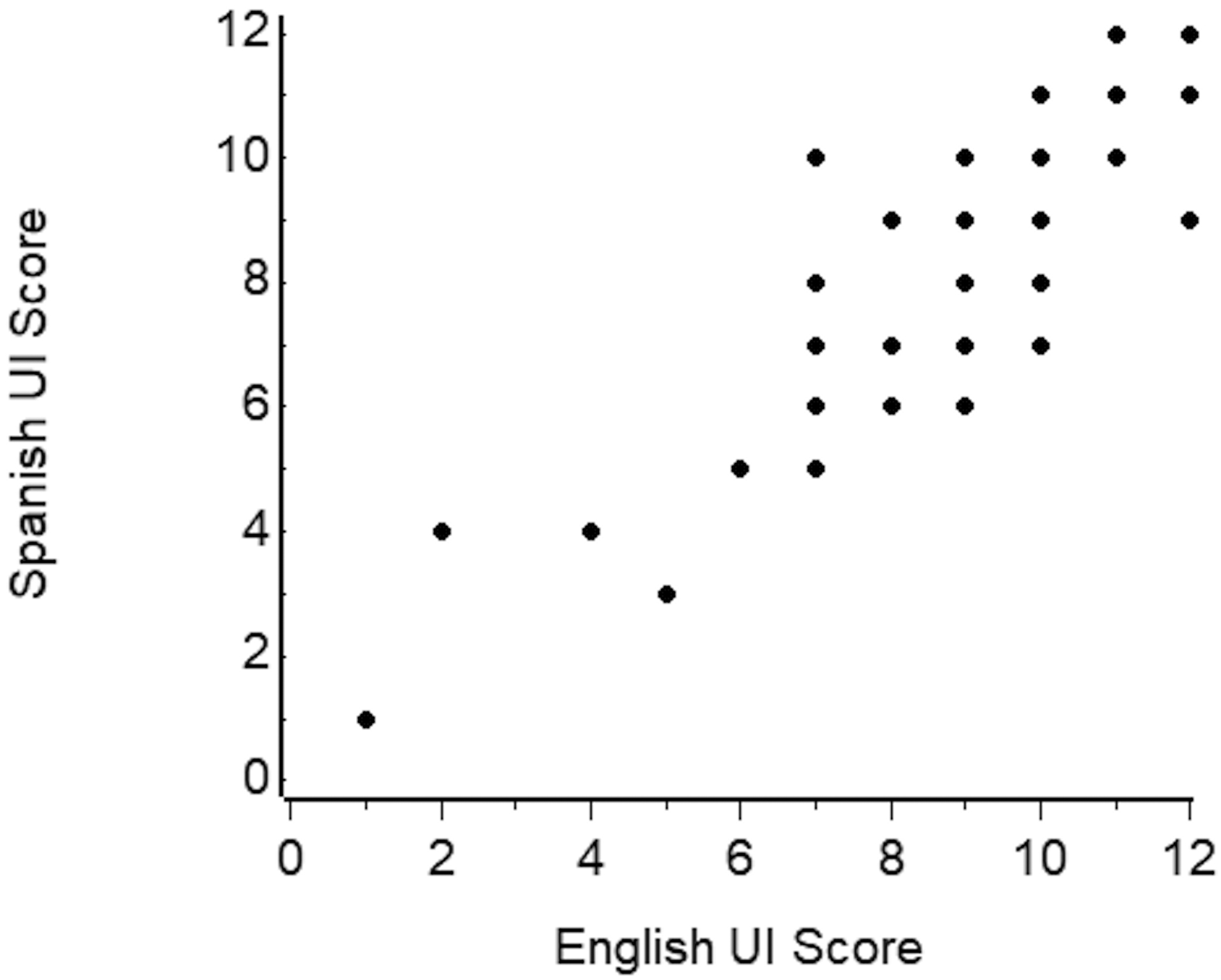

ICCs for the overall PIKQ score and POP and UI subscores between the original English and the final Spanish PIKQ showed excellent agreement (0.81–0.91) (Figure 2). Participants had similar total and POP subscale scores on the English and Spanish versions of the PIKQ (mean total score 17.3 (SD 4.4) versus 17.4 (SD 4.3), p=0.66); mean POP subscale score (8.4 (SD 2.3) versus 8.1 (SD 2.3), p=0.11). For the PIKQ UI subscale, participants scored higher on the English version than the Spanish version (mean 9.3 (SD 2.4) versus mean 8.9 (SD 2.6), p=0.02). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient demonstrated acceptable internal reliability for the overall Spanish PIKQ (0.80) and for the UI (0.72) and POP subscales (0.64). As compared to women with high school-level education, women with college-level education or greater scored higher on the overall Spanish PIKQ (mean 17.8 (SD 3.9) versus 13.4 (SD 5.9), p=0.01), UI subscale (mean 9.2 (SD 2.4) vs. 6.4 (SD 2.9), p=0.007), and POP subscale (mean 8.6 (SD 2.1) versus 7.0 (SD 3.1), p=0.08). There were no significant score differences between telephone–administered (n=27) and emailed (n=30) questionnaires for both English and Spanish PIKQ versions (mean English score (17.1 (SD 4.0) versus 17.6 (SD 4.6), p=0.63; mean Spanish score (17.4 (SD 3.8) versus 17.1 (SD 4.9), p=0.77).

Figure 2.

Scatterplots of the Spanish versus English PIKQa scores:

2A) Overall scores, Intraclass correlation coefficient r=0.91, p<0.001

2B) POPb subscale scores, Intraclass correlation coefficient r=0.81, p<0.001

2C) UIc subscale scores, Intraclass correlation coefficient r=0.88, p<0.001

aPIKQ: Prolapse and Incontinence Knowledge Questionnaire

bPOP: Pelvic Organ Prolapse

cUI: Urinary Incontinence

Fifty-four women completed the Spanish PIKQ again 1–2 weeks after completing it the first time (Figure 1). For test-retest reliability of the Spanish PIKQ, Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the initial and repeat Spanish PIKQ scores were high for the total score (r=0.87) and for POP (r=0.81) and UI (r=0.77) subscores. ICCs between the initial and repeat Spanish PIKQ scores were high for the total score (0.84) and for POP (0.80) and UI (0.73) subscores indicating good to excellent agreement.

Discussion

We developed a Spanish version of the PIKQ with each question item demonstrating moderate to excellent “comparability of language” and “similarity of interpretability” compared to the original English PIKQ. Additionally, there was high percent agreement between responses on the final Spanish and original English versions. When adjusting for chance agreement using Kappa statistics, the agreement for answers to most questions remained high or moderately high with the exception of one question on the diagnosis of POP. Kappa is not a good estimate of agreement when the prevalence of responses is rare.30 In this case when only 2 of 57 participants had a different response to the Spanish and English versions than the remaining participants, this led to a negative Kappa estimate. There was excellent agreement between the PIKQ total, UI subscale, and POP subscale scores on the Spanish and English versions. The Spanish PIKQ demonstrated internal consistency and women with higher levels of education had higher scores. Additionally, the test-retest reliability of the Spanish PIKQ was high.

Our validation methodology parallels that used in other validation studies31 and our results generally parallel other studies validating Spanish versions of PFD questionnaires.32 In addition to assessing severity and impact of prolapse and incontinence symptoms, we can achieve a better understanding of healthcare barriers and knowledge gaps in Spanish-speaking women. Previous studies utilizing the PIKQ have focused on Caucasian women or had few Hispanic participants.20,33,34 Despite the limited representation, studies have found that women of color have significant deficits in knowledge regarding disease progression and treatments compared to Caucasian women.33,35 Considering Hispanic women are at higher risk for developing PFDs from factors such as increased parity and BMI,8 a validated Spanish PIKQ will help identify Spanish-speaking women with poor PFD knowledge and promote inclusion in pelvic floor research. This will allow tailoring of culturally appropriate educational efforts, thus facilitating understanding and subsequent treatment.

A limitation of our study is the use of bilingual women when the intended population would be Spanish-only or Spanish-preferred speaking women. These women may not interpret the questionnaire in the same manner as our study participants. Because each participant served as her own control, recall bias may contribute to a falsely higher level of agreement between English and Spanish responses. However, we attempted to minimize this bias by randomizing women to complete either the Spanish or English version of the PIKQ first. Additionally, we could not study construct validity as we did not have a gold standard for determination of PFD knowledge. We did not objectively evaluate for any existing PFDs or history of urogynecologic care in our participants and the average age was 32 years, younger than the typical patient presenting with PFDs. We acknowledge that this may have an impact on baseline knowledge of these conditions, however this should not impact the validation process as we are focusing on level of agreement between English and Spanish responses. Our study was conducted at one institution and may not reflect the diversity of Hispanic women across the U.S.; however, participants identified at least 10 different Latin American countries as their place of origin. Most participants had some college-level education, considered both English and Spanish as their primary language and were born in the Dominican Republic or the United States. We acknowledge that there are differences in subcultures based on education level, geography and place of origin and our Spanish version is not validated in all settings in which Spanish is spoken.

Standard protocols for the translation of questionnaires into different languages do not exist. The method of translation-back translation and the utilization of bilingual women for validation are accepted ways of validating translated versions of questionnaires.21,31 Our rigorous process of utilizing multiple bilingual translators and a scoring system to quantify the comparability of language and similarity of interpretability in the multiple back-translated versions ensures that our newly synthesized Spanish questionnaire resembles the original PIKQ in form and meaning. Our Spanish version, like the original PIKQ, was administered via different modes: telephone and emailed links. Comparing the two survey modes, our analysis did not find any significant differences, thus mode does not appear to affect survey responses.19

Insufficient knowledge regarding treatment serves as a major barrier to care-seeking for women with PFDs.36 Interventions that enhance knowledge about pelvic floor health have proven effective in promoting symptomatic change and improving quality of life.37 However, interventions focused on Spanish-speaking women are lacking. Through a rigorous translation-back translation method, we developed a valid and reliable Spanish version of the PIKQ to assess knowledge of PFDs in Spanish-speaking women. Additionally, we determined that the Spanish PIKQ performed similarly to the original English version in bilingual women. The Spanish PIKQ can be utilized by healthcare providers to better understand the knowledge gaps among Hispanic women and develop culturally sensitive educational strategies to increase understanding of PFDs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dr. Carlos Muñiz, Richard De Los Santos Abreu, Rosa Cerna, Sophia Diaz and Anna Young for their technical assistance, data collection, data interpretation and manuscript readability as it pertains to this project.

Source of funding: K.A.C.’s work on the project was funded in part by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, under grant number UL1 TR003098 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The source of funding did not have involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, et al. Prevalence and Trends of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in U.S. Women. Obstet Gynecol 2014;123(1):141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holst K, Wilson PD. The prevalence of female urinary incontinence and reasons for not seeking treatment. N Z Med J. 1988;101(857):756–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hägglund D, Wadensten B. Fear of Humiliation Inhibits Women’s Care-Seeking Behaviour for Long-Term Urinary Incontinence. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007;21(3):305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch LH. Help-seeking Behaviors of Women With Urinary Incontinence: An Integrative Literature Review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2006;51(6): e39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrill M, Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, et al. Seeking Healthcare for Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Population-Based Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(1):86.e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger MB, Patel DA, Miller JM, et al. Racial Differences in Self-Reported Healthcare Seeking and Treatment for Urinary Incontinence in Community-Dwelling Women from the EPI Study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(8): 1442–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colby SL, Ortman JM. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Current Population Reports, P25–1143. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thom DH, Van den Eedan SK, Ragins I, et al. Differences in prevalence of urinary incontinence by race/ethnicity. J Urol. 2006;175(1):259–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A, et al. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitcomb EL, Rortveit G, Brown JS, et al. Racial differences in pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1271–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan AA, Sevilla C, Wieslander CK, et al. Communication barriers among Spanish-speaking women with pelvic floor disorders: lost in translation? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(3):157–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siddiqui NY, Levin PJ, Phadtare A, et al. Perceptions About Female Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(7):863–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willis-Gray MG, Sandoval JS, Maynor J, et al. Barriers to Urinary Incontinence Care Seeking in White, Black, and Latina Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015; 21(2):83–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhodes SD, Mann L, Simán FM, et al. The impact of local immigration enforcement policies on the health of immigrant hispanics/latinos in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wieslander CK, Alas A, Dunivan GC, et al. Misconceptions and Miscommunication among Women with Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(4):597–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunivan GC, Anger JT, Alas A, et al. Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Disease of Silence and Shame. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2014;20(6):322–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sevilla C, Wieslander CK, Alas AN, et al. Communication Between Physicians And Spanish-Speaking Latin American Women With Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Cycle Of Misunderstanding? Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(2):90–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddiqui NY, Ammarell N, Wu JM, et al. Urinary incontinence and health seeking behavior among White, Black, and Latina women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016; 22(5):340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah AD, Massagli MP, Kohil, et al. A reliable, valid instrument to assess patient knowledge about urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(9):1283–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandimika CL, Murk W, Mcpencow AM, et al. Racial Disparities in Knowledge of Pelvic Floor Disorders Among Community-Dwelling Women. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2015;21(5):287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sperber AD, DeVellis RF, Boehlecke B. Cross-cultural translation: Methodology and Translation. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1994;25:501–524. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford AN. A Spanish language Fry type readability procedure: Elementary level. Los Angeles, CA: Bilingual Education Paper Series; 1984;7:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández Huerta J Medidas sencillas de lecturabilidad. Consigna. 1959;214:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrio-Cantalejo IM, Simón-Lorda P, Melguizo M, et al. Validación de la Escala INFLESZ para evaluar la legibilidad de los textos dirigidos a pacientes [Validation of the INFLESZ scale to evaluate readability of texts aimed at the patient]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2008;31(2):135–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streiner DL, Norman J. Health measurement scales. New York, NY: Oxford University Press;1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sim J, Wright C. Research in Health Care: Concepts, Designs and Methods. Cheltenham, UK: Stanley Thornes Ltd;2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omotosho TB, Hardart A, Rogers RG, et al. Validation of Spanish versions of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory and Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire: a multicenter validation randomized study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(6):623–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young AE, Fine PM, McCrery R, et al. Spanish language translation of pelvic floor disorders instruments. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson ERW, Myers EM, De La Cruz JF, et al. Baseline Understanding of Urinary Incontinence and Prolapse in New Urogynecology Patients. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(1):67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mandimika CL, Murk W, McPencow AM, et al. Knowledge of pelvic floor disorders in a population of community-dwelling women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(2):165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen CCG, Cox JT, Yuan C, et al. Knowledge of pelvic floor disorders in women seeking primary care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berger MB, Patel DA, Miller JM, et al. Racial differences in self-reported healthcare seeking and treatment for urinary incontinence in community-dwelling women from the EPI study. Neurourol Urodyn, 2011;30(8):1442–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geoffrion R, Robert M, Ross S, et al. Evaluating patient learning after an educational program for women with incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(10):1243–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.