Introduction:

Despite high rates of suicide among LGBTQ+ youth, the interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS) has rarely been examined in this population. The current study utilized a longitudinal design to examine whether perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness independently and simultaneously predicted higher levels of suicidal ideation over time in a sample of LGBTQ+ youth who utilized crisis services. We also investigated whether gender identity moderated these associations. Methods: A total of 592 youth (12–24 years old) who had contacted a national crisis hotline for LGBTQ+ youth completed two assessments 1-month apart. Results: Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness independently predicted greater suicidal ideation 1 month later; however, only perceived burdensomeness remained prospectively associated with suicidal ideation when both factors were tested in the same model. Gender identity moderated the associations between IPTS factors and suicidal ideation, such that both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were associated with greater suicidal ideation 1 month later for sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender/genderqueer individuals, but not for sexual minority cisgender young men. Conclusion: The IPTS helps explain increases in suicidal ideation over time among LGBTQ+ youth and therefore can be used to inform suicide prevention and intervention approaches for this population.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, suicide is the second leading cause of death for youth aged 10–24 years (Curtin & Heron, 2019). For lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) youth, the risk for suicide is even more pronounced. Meta-analyses demonstrate that sexual minority youth are two times more likely to report suicidal ideation (Marshal et al., 2011) and over three times more likely to attempt suicide (di Giacomo et al., 2018) than heterosexual youth. Similarly, research on transgender and gender diverse youth has found high rates of suicidal ideation, with 45%–77% reporting a history of suicidal ideation (e.g. Grossman & D’Augelli, 2007; Scanlon et al., 2010). Furthermore, youth who identify as transgender are over five times as likely to report having attempted suicide compared with cisgender youth (di Giacomo et al., 2018), with 45% of transgender youth aged 18–24 years reporting a history of attempted suicide (Herman et al., 2014). These wide disparities in suicidal thoughts and behaviors are often attributed to the unique and chronic stressors that LGBTQ+ people experience (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003), such as victimization, discrimination, and peer and family rejection.

The interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS) is a well-known framework for explaining suicidal behavior in the general population (Joiner, 2005). It is a tripartite model comprising three constructs related to suicide risk, two primarily related to suicidal desire: perceived burdensomeness (i.e., the belief that one is a burden on others; Van Orden et al., 2010) and thwarted belongingness (i.e., a perception of social isolation or disconnection from others; Joiner, 2005). The theory posits that these two risk factors, in combination with acquired capability for suicide (i.e., reduced fear of death and increased pain tolerance), result in suicidal behavior. There is substantial support for perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as risk factors for suicidal ideation, mostly among adults (e.g. Batterham et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2014; Chu et al., 2017; Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden et al., 2010), but also among adolescents (see Stewart et al., 2017 for a review). Still, only a few studies have tested the IPTS using longitudinal data (Barzilay et al., 2019; Batterham et al., 2018; Christensen et al., 2014) and only one of which focused on youth (Barzilay et al., 2019). These studies provide preliminary support for the IPTS in youth.

Despite substantial evidence of disparities in suicidality affecting LGBTQ+ youth and evidence that the explanatory power of the IPTS may differ across groups (Ma et al., 2016), relatively few studies have examined the extent to which the IPTS can explain suicidality among LGBTQ+ youth, particularly those who are at higher risk for suicide (e.g., those who utilized crisis services). Furthermore, the studies that have examined the IPTS among LGBTQ+ individuals have largely relied on cross-sectional data and focused on adults. Several studies have found that sexual minority adults report greater perceived burdensomeness than heterosexual adults (Hill & Pettit, 2012; Pate & Anestis, 2019; Woodward et al., 2014), and that both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are associated with greater suicidal ideation among sexual minority adults (Hill & Pettit, 2012; Pate & Anestis, 2019; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Ploderl et al., 2014; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2020), as well as transgender and gender nonconforming youth and young adults (Grossman et al., 2016). However, some studies have found that only perceived burdensomeness is associated with greater suicidal ideation among sexual minority youth and adults (Baams et al., 2015, 2018; Woodward et al., 2014). Taken together, the existing literature suggests that the IPTS is a promising framework for explaining suicidality among LGBTQ+ individuals. However, given that all of these studies have been cross-sectional and that most of them have focused on adults, it remains unclear if perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are associated with increases in suicidal ideation over time among LGBTQ+ youth. Moreover, as the IPTS was designed to understand the risk for suicide in high-risk and clinical populations (Joiner, 2005), examining perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness among LGBTQ+ youth who have utilized crisis services has the potential to advance our understanding of the relevance of the IPTS to a subgroup of LGBTQ+ youth who are at particularly high risk.

In addition to the need for longitudinal research on the IPTS in samples of LGBTQ+ youth, there is also a need to examine the extent to which the IPTS generalizes to subgroups in this population (e.g., cisgender young men, cisgender young women, and transgender/genderqueer individuals). This is especially true for transgender and gender diverse youth, given that only one study has tested the IPTS in this population (Grossman et al., 2016). In studies of the general population, adolescent young women are more likely to report suicidal ideation (CDC, 2016) and to have suicide plans (Nock et al., 2013) than adolescent young men, but adolescent young men are more likely to die by suicide (CDC, 2017). Further, adolescent young women report greater levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness than adolescent young men (Hill et al., 2017). This gender difference may be attributed to gender differences in interpersonal socialization, which teaches young women to be more attuned to emotions and thoughts (Baron-Cohen & Wheelwright, 2004) as well as social relationships (Eder, 1985), thus leading to greater vulnerability to interpersonal stressors.

Despite these well-established gender differences in suicidality and IPTS factors, only three studies have examined the role of gender in the IPTS framework. First, one cross-sectional study found that thwarted belongingness was a stronger predictor of suicidal ideation for men than women, but the association between perceived burdensomeness and suicidal ideation did not differ between the groups (Van Orden et al., 2010). In contrast, another study found that IPTS effects were stronger for women than that for men, possibly due to women having a close-knit circle of interpersonal relationships, thus leading to a greater impact of interpersonal challenges (Batterham et al., 2018). Finally, using data from a sample of adolescents on a psychiatric inpatient unit, Hill et al. (2017) found that thwarted belongingness was only associated with greater suicidal ideation at low levels of perceived burdensomeness for young women and at high levels of perceived burdensomeness for young men.

These studies provide preliminary support for gender differences in aspects of the IPTS, but notably, it remains unclear to what extent these gender differences extend to LGBTQ+ individuals, especially transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Transgender and gender-diverse individuals experience high levels of victimization and report low levels of social support (e.g., Hatchel et al., 2019), which may increase their susceptibility to the negative effects of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Furthermore, these interpersonal risk factors may carry special significance for transgender and gender diverse individuals (Salentine et al., 2020), given the importance of community belongingness to transgender individuals’ well-being (Barr et al., 2016). Recent work has also demonstrated that interpersonal hopelessness (i.e., hopelessness regarding perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) is associated with suicidal ideation and that it may exacerbate the effects of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on suicidal ideation as well (Tucker et al., 2018). Given the pervasiveness of societal stigma against transgender people, perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may be particularly strong predictors of suicidal ideation for them because they may be particularly likely to perceive these experiences as being unlikely to change over time.

Finally, given the development of interventions to address perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Short et al., 2019), examining the IPTS among LGBTQ+ youth who have utilized crisis services has the potential to inform efforts to reduce suicidality in this population. Specifically, if perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are associated with increases in suicidal ideation over time in this population, then it would suggest that targeting these risk factors in interventions could reduce suicidality.

To address these gaps in our understanding of suicidality among high-risk LGBTQ+ youth, the goal of the current study was to examine components of the IPTS using longitudinal data (two assessments, 1 month apart) from a sample of LGBTQ+ youth who had contacted a national suicide prevention hotline for LGBTQ+ youth. The current study specifically focused on perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness because of their relevance to suicidal ideation, which is a robust risk factor for suicide (Nock et al., 2008). First, we examined whether baseline levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness independently and simultaneously predicted suicidal ideation at the follow-up assessment, controlling for suicidal ideation at the baseline assessment. We hypothesized that higher levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness would independently and simultaneously predict increases in suicidal ideation over time. Second, as an exploratory aim, we examined whether gender identity moderated these associations.

METHODS

Participants

The present study included 592 youth (ages 12–24) who were recruited following their contact with a national suicide prevention crisis service designed to serve young people from the LGBTQ+ community. Recruitment for the study occurred over an 18-month period from September 2015 to April 2017. Participants’ mean age was 17.6 (SD = 3.1) years. Most participants were white (75%), and the most commonly endorsed gender and sexual orientation identities were cisgender young women (35%) and gay (24%), respectively. A complete profile of the participants’ demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of sample demographics (N = 592)

| Variable | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Gender identity | ||

| Female | 35.1% | 208 |

| Male | 25.3% | 150 |

| Trans female/woman | 3.0% | 18 |

| Trans male/man | 12.3% | 73 |

| Genderqueer | 8.8% | 52 |

| Questioning | 5.9% | 35 |

| Do not know | 2.0% | 12 |

| Other gender identity | 7.1% | 42 |

| Declined to answer | 0.3% | 2 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 24.0% | 142 |

| Lesbian | 15.2% | 90 |

| Bisexual | 17.1% | 101 |

| Queer | 7.9% | 47 |

| Pansexual | 17.1% | 101 |

| Asexual | 5.6% | 33 |

| Questioning | 8.1% | 48 |

| Straight | 0.2% | 1 |

| Other sexual orientation | 1.2% | 3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 75.3% | 446 |

| Black or African American | 10.0% | 59 |

| Latino/Hispanic | 13.0% | 77 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7.4% | 44 |

| Native American/American Indian/Alaskan Native | 3.4% | 20 |

| Other | 3.2% | 19 |

Procedures

Following contact with the crisis service (i.e., phone, text, or online chat), youth who were not at imminent suicide risk (i.e., those who did not report a suicide plan with intent to act on it within 48 h) and who did not require a child abuse report were transferred to an automated survey that asked if they would be willing to be contacted for a follow-up survey focused on the needs of LGBTQ+ young people. Youth who were interested in the study provided their demographic and contact information. Of those referred to the automated survey, 3403 individuals agreed to be contacted by the research team; after screening individuals for eligibility (i.e., aged 12–24 years, non-duplicate contact) and valid contact information, 2008 of them were referred for data collection. A research team member then established contact with prospective participants to confirm their identity and eligibility and to obtain informed assent/consent. A standard script was used to determine identity without revealing the study purpose. That is, after asking for the person by name, they were informed that we were reaching out because they had “recently contacted a provider and agreed to be added to a contact list.” They were then asked to tell us the name of the provider. Those who could remember the provider’s name moved to the consent step. Those who could not remember the provider’s name were thanked for their time and the contact was terminated.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) waived parental consent to enhance protection for participants whose safety may be compromised if outed to parents or guardians. After consent was obtained, participants were reassessed for suicide risk using a screener that mirrored the crisis support program, and participants not at imminent risk were sent a link to the baseline survey. Those at imminent risk were transferred back to the crisis support provider for intervention and recontacted at another time to assess for study participation appropriateness. Participants were then recontacted 30 days later to complete a follow-up survey replicating the process described before. All participants received a $15 gift card for completing the baseline survey and a $10 gift card for completing the follow-up survey.

Of the 2008 youth who were referred for data collection, 33% of them (n = 657) completed the baseline survey (see Blinded for Review for further details); after 65 observations were removed from the dataset (i.e., duplicate records or missing information on variables of interest), a total of 592 participants were included in the present analyses. All study procedures were approved by the IRB at the principal investigator’s home institution.

Measures

Suicidal ideation severity

Severity of suicidal ideation since the last time the participant contacted the hotline (at baseline) or within the past month (at follow-up) was assessed with five items that were adapted for self-report from the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2011). The questions inquire about five types of suicidal ideation (passive ideation, active ideation, method, intent, and plan) that are assessed in the order of their severity. Scores were assigned based on the most severe type of suicidal ideation that was endorsed (0 = none; 1 = passive ideation; 2 = active ideation; 3 = method; 4 = intent; and 5 = intent with plan). Thus, the score can range from 0 (i.e., no suicidal ideation = lowest risk) to 5 (i.e., suicidal intent with plan = highest risk).

Perceived burdensomeness

Perceived burdensomeness was assessed with the 5-item sub-scale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-10 (Hill et al., 2015; Van Orden et al., 2012). Respondents rated five statements on a scale from “not at all true for me” (1) to “very true for me” (7). An example item read, “These days, the people in my life would be better off if I were gone.” Thus, the sum score ranged from 5 to 35, with higher scores corresponding to higher perceived burdensomeness. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was 0.95 in this study.

Thwarted belongingness

Thwarted belongingness was assessed with the 5-item sub-scale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-10 (Hill et al., 2015; Van Orden et al., 2012). Respondents rated 10 statements on a scale from “not at all true for me” (1) to “very true for me” (7). An example item read, “These days, I feel disconnected from other people.” Thus, the sum score ranged from 5 to 35, with higher scores corresponding to higher thwarted belongingness. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was 0.77 in this study.

Demographics

Self-report questions were used to obtain information about age, sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. All response options provided for sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity questions are shown in Table 1. For the current analyses, gender was recoded into cisgender young men, cisgender young women, and transgender/genderqueer youth; notably, all youth who endorsed a gender minority status (i.e., transfemale, transmale, genderqueer, questioning, or other identity) were classified as “transgender/genderqueer” based on the relatively low number of youth in constituent groups.

Analytic strategy

First, using SPSS Statistics 23, we examined potential demographic differences (age, gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity) in our variables of interest (perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, suicidal ideation at baseline, and suicidal ideation at follow-up). To do so, we used Pearson correlations (for age) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post hoc Tukey tests (for gender, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity). Next, using Mplus 8 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012), we examined perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness at baseline as predictors of suicidal ideation at follow-up, controlling for suicidal ideation at baseline. We examined them as independent predictors in separate models (Models 1a and 1b) and as simultaneous predictors in the same model (Model 2). Nearly one-third of participants in the analytic sample (n = 187; 31.6%) were missing data on suicidal ideation at follow-up because they did not complete the follow-up survey. We used full information maximum likelihood to address missingness (Enders, 2010). Then, we tested gender as a moderator of the associations between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness at baseline and suicidal ideation at follow-up, controlling for suicidal ideation at baseline. For the moderation analyses, gender was dummy-coded with cisgender young men as the reference group, continuous variables were standardized, and interaction terms were constructed in Mplus. Separate moderation analyses were conducted for perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Models 3a and 3b). Then, the moderation analyses were repeated while controlling for the other IPTS factor (Models 4a and 4b). For example, the model testing gender as a moderator of the association between perceived burdensomeness at baseline and suicidal ideation at follow-up controlled for thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation at baseline.

RESULTS

Preliminary results

Means and standard deviations for all variables of interest are presented in Table 2 (for the full analytic sample and as a function of gender). Perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with thwarted belongingness (r = 0.47, p = 0.001). Gender was significantly associated with perceived burdensomeness (F(2, 579) = 17.23, p < 0.001), thwarted belongingness (F(2, 579) = 3.67, p = 0.03), suicidal ideation at baseline (F(2, 589) = 3.90, p = 0.02), and suicidal ideation at follow-up (F(2, 385) = 4.99, p = 0.01). Post hoc Tukey tests revealed that transgender/genderqueer youth reported significantly greater perceived burdensomeness than cisgender young women (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.42) and cisgender young men (p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.57), although cisgender young women did not differ significantly compared with cisgender young men (p = 0.42). Transgender/genderqueer youth also reported significantly greater thwarted belongingness than cisgender young men (p = 0.03, Cohen’s d = 0.29). At baseline, transgender/genderqueer youth reported significantly greater suicidal ideation than cisgender young men (p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.29). At follow-up, transgender/genderqueer youth reported significantly greater suicidal ideation than cisgender young women (p = 0.04, Cohen’s d = 0.28) and cisgender young men (p = 0.02, Cohen’s d = 0.37). Age was significantly associated with thwarted belongingness (r = 0.12, p = 0.003), but it was not significantly associated with any other variables of interest (all p’s > 0.15). Neither race/ethnicity nor sexual orientation was significantly associated with any of the variables of interest (all p’s > 0.07).

TABLE 2.

Means and standard deviations for variables of interest

| Analytic sample | Cisgender young men | Cisgender young women | Transgender/genderqueer youth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived burdensomeness | 14.61 (9.23) | 11.91 (8.40) | 13.20 (8.71) | 16.99 (9.46) |

| Thwarted belongingness | 21.09 (7.01) | 19.92 (7.04) | 20.80 (7.31) | 21.89 (6.69) |

| Suicidal ideation (baseline) | 2.23 (2.08) | 1.86 (2.12) | 1.87 (1.96) | 2.46 (2.03) |

| Suicidal ideation (follow-up) | 2.09 (2.01) | 1.70 (1.97) | 1.87 (1.96) | 2.43 (2.02) |

Note:: The possible range of values was 5–35 for perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and 0–5 for suicidal ideation.

IPTS factors as predictors of suicidal ideation

Results are presented in Table 3. In Model 1a, perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation at follow-up, controlling for suicidal ideation at baseline. Similarly, in Model 1b, thwarted belongingness was also significantly associated with suicidal ideation at follow-up, controlling for suicidal ideation at baseline. In Model 2, when both IPTS factors were included in the same model, perceived burdensomeness remained significant, but thwarted belongingness became nonsignificant.

TABLE 3.

Regression analyses for IPTS factors, gender, and their interactions predicting suicidal ideation at follow-up

| Suicidal ideation at follow-up | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| PB | TB | PB & TB | PB | TB | PB | TB | |

| Baseline suicidal ideation | .46 (.05)*** | .50 (.04)*** | .46 (.05)*** | .47 (.05)*** | .50 (.05)*** | .47 (.05)*** | .47 (.05)*** |

| Perceived burdensomeness | .20 (.05)*** | - | .16 (.06)** | −0.09 (.11) | - | −.11 (.11) | .14 (.06)* |

| Thwarted belongingness | - | .15 (.04)*** | .07 (.05) | - | −.10 (.09) | .06 (.05) | −.14 (.09) |

| Cisgender young man (reference) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cisgender young woman | - | - | - | .12 (.12) | .07 (.11) | .12 (.12) | .06 (.12) |

| Transgender/genderqueer | - | - | - | .22 (.11)* | .21 (.11)* | .22 (.11)* | .16 (.11) |

| Cisgender young woman × PB | - | - | - | .34 (.13)** | .32 (.13)* | ||

| Transgender/genderqueer × PB | - | - | - | .33 (.12)** | .33 (.13)* | ||

| Cisgender young woman × TB | - | - | - | .23 (.11)* | .21 (.11) | ||

| Transgender/genderqueer × TB | - | - | - | .34 (.10)** | .32 (.11)** | ||

Note: Standardized regression coefficients are shown with SE in parentheses. In Model 1, PB and TB were tested as separate predictors of SI at follow-up, controlling for SI at baseline; in Model 2, PB and TB were tested as simultaneous predictors of SI at follow-up, controlling for SI at baseline; in Model 3, gender was tested as a moderator of the associations between PB/TB (in separate models) and SI at follow-up, controlling for SI at baseline; in Model 4, gender was tested as a moderator of the associations between PB/TB and SI at follow-up, controlling for SI at baseline and the other IPTS factor; gender was dummy-coded and the IPTS factors were mean-centered to compute the interaction terms.

Abbreviations: PB, perceived burdensomeness; SI, suicidal ideation; TB, thwarted belongingness.

Gender as a moderator

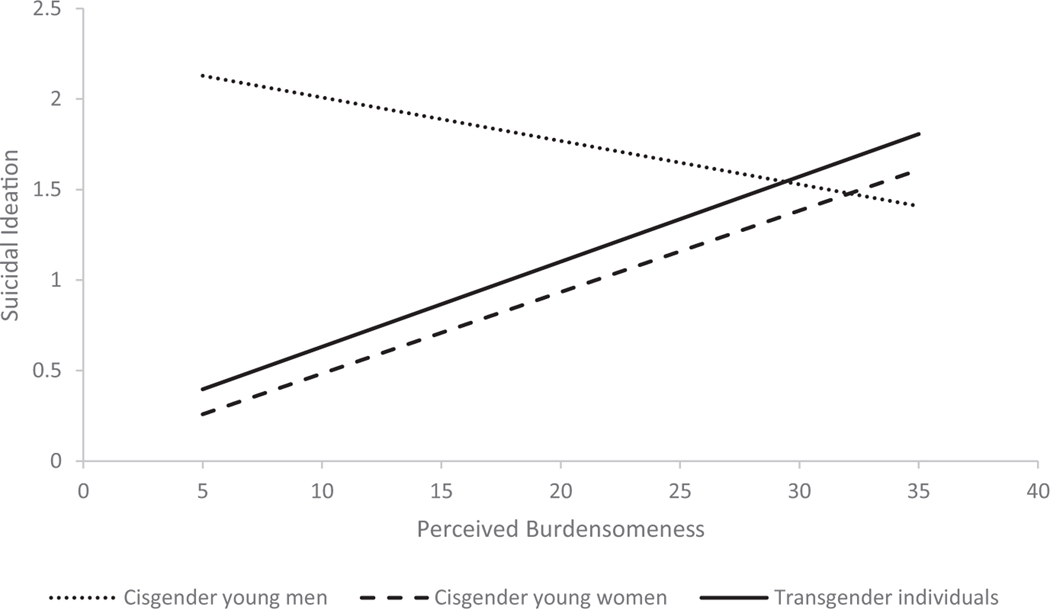

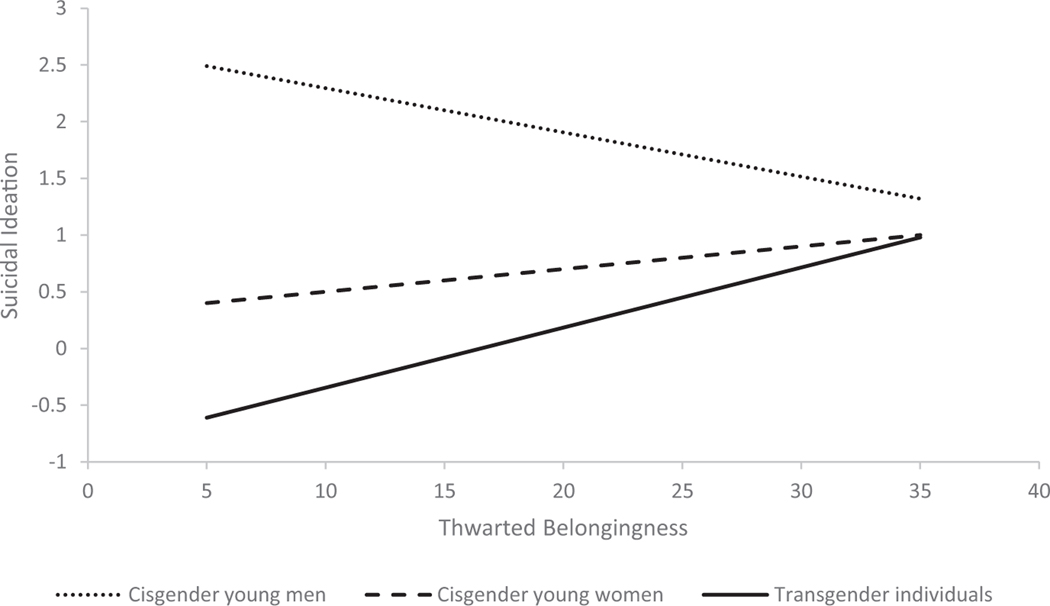

In Model 3a (Figure 1), there were significant interactions between perceived burdensomeness and identifying as a cisgender young woman, as well as identifying as transgender/genderqueer. Simple slope analyses revealed that perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation at the follow-up for cisgender young women (β = 0.25, SE = 0.08, p = 0.001) and for transgender/genderqueer individuals (β = 0.25, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001), but not for cisgender young men (β = −0.09, SE = 0.11, p = 0.43). Similarly, in Model 3b (Figure 2), there were significant interactions between thwarted belongingness and identifying as a cisgender young woman as well as identifying as transgender/genderqueer. Simple slope analyses revealed that thwarted belongingness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation at follow-up for cisgender young women (β = 0.13, SE = 0.06, p = 0.03) and for transgender/genderqueer youth (β = .24, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001), but not for cisgender young men (β = −0.10, SE = 0.09, p = 0.28).

FIGURE 1.

Graph depicting gender as a moderator of the association between perceived burdensomeness at baseline and suicidal ideation at 1-month follow-up, controlling for baseline suicidal ideation

FIGURE 2.

Graph depicting gender as a moderator of the association between thwarted belongingness at baseline and suicidal ideation at 1-month follow-up, controlling for baseline suicidal ideation

In Models 4a and 4b, the moderation analyses were repeated while controlling for other IPTS factors. Controlling for thwarted belongingness, there were still significant interactions between perceived burdensomeness and identifying as a cisgender girl as well as identifying transgender/genderqueer. Again, perceived burdensomeness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation at follow-up f or cisgender girls (β = 0.21, SE = 0.09, p = 0.02) and for transgender/genderqueer youth (β = 0.21, SE = 0.07, p = 0.004), but not for cisgender boys (β = −0.11, SE = 0.11, p = 0.32). Controlling for perceived burdensomeness, there was still a significant interaction between thwarted belongingness and identifying as transgender/genderqueer. Again, thwarted belongingness was significantly associated with suicidal ideation at follow-up for transgender/genderqueer youth (β = 0.18, SE = 0.06, p = 0.003), but not for cisgender boys (β = −0.14, SE = 0.09, p = 0.12). The interaction between thwarted belongingness and identifying as a cisgender girl became nonsignificant when controlling for perceived burdensomeness, and the simple slope for cisgender girls became nonsignificant as well (β = 0.07, SE = 0.06, p = 0.27).

DISCUSSION

Given that LGBTQ+ youth are at increased risk for suicidality compared with their heterosexual and cisgender peers (di Giacomo et al., 2018; Marshal et al., 2011), there is a critical need to identify risk factors for suicidality in this population. Yet, despite substantial support for the interpersonal theory of suicide (IPTS; Joiner, 2005), most of this support comes from cross-sectional studies of heterosexual adults, and many of these studies did not focus on the high-risk or clinical populations for whom the IPTS was intended. As such, the primary goal of the current study was to use longitudinal data to examine the extent to which the IPTS could be used to explain suicidal ideation in a sample of LGBTQ+ youth who were considered high risk because they had utilized crisis services. Furthermore, given evidence of gender differences in the IPTS in cross-sectional studies of heterosexual adolescents (Hill et al., 2017) and adults (Batterham et al., 2018; Van Orden et al., 2010), we also examined potential gender differences in the IPTS among LGBTQ+ youth who utilized crisis services, including transgender individuals.

We found that higher levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness at baseline were both associated with increases in suicidal ideation 1 month later. However, when they were tested in the same model, only perceived burdensomeness was prospectively associated with greater suicidal ideation. This suggests that perceived burdensomeness is a stronger risk factor for suicidal ideation than thwarted belongingness, at least among LGBTQ+ youth who utilized crisis services. These findings are generally consistent with previous cross-sectional studies of LGBTQ+ individuals, with some observing that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were both associated with greater suicidal ideation (Grossman et al., 2016; Pate & Anestis, 2019; Plöderl & Fartacek, 2005; Ploderl et al., 2014; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2020) and others observing that only perceived burdensomeness was associated with greater suicidal ideation (Baams et al., 2015, 2018; Woodward et al., 2014). Because of floor effects in perceived burdensomeness, it is possible that associations that involved perceived burdensomeness were attenuated. Of note, although our use of a longitudinal design represents a major strength of our study, it will be important for future research to use different designs (e.g., experimental designs, ecological momentary assessment, and longitudinal studies with longer time intervals between assessments) to continue to advance our understanding of the temporality of these associations.

By replicating previous cross-sectional findings using longitudinal data, our study provides stronger evidence for the relevance of the IPTS to high-risk LGBTQ+ youth and for the influence of perceived burdensomeness, in particular on suicidal ideation in this population. With that said, our findings are not entirely consistent with the only other longitudinal work testing the IPTS among youth. We are only aware of one previous study that has tested the IPTS in a sample of youth using longitudinal data (Barzilay et al., 2019). They found that thwarted belongingness from parents was associated with a greater likelihood of suicidal ideation 1 year later, but thwarted belongingness from peers and perceived burdensomeness were not significantly associated with changes in suicidal ideation over time. These findings point to the possibility that the influence of thwarted belongingness on suicidal ideation may depend on the relationship context in which thwarted belongingness occurs. Furthermore, although we found that perceived burdensomeness was prospectively associated with greater suicidal ideation 1 month later in our study, Barzilay and colleagues’ findings suggest that this effect may be time-limited. Still, given that the majority of their participants were likely heterosexual (they did not report on their participants’ sexual orientations), there is a continued need for longitudinal research on the IPTS in samples of LGBTQ+ youth.

We also found that gender moderated the associations between the IPTS factors and suicidal ideation, such that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were both prospectively associated with greater suicidal ideation for sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender individuals, but not for sexual minority cisgender young men. We are only aware of three previous studies that have examined gender differences in the associations between IPTS factors and suicidal ideation, all of which were cross-sectional studies of presumably cisgender and heterosexual adolescents (Hill et al., 2017) and adults (Batterham et al., 2018; Van Orden et al., 2010). Furthermore, each of these previous studies found a different pattern of gender differences in the associations between IPTS factors and suicidal ideation. One study found that the association between thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation was stronger for men than women (Van Orden et al., 2010), one study found that the associations between IPTS factors and suicidal ideation were stronger for women than men (Batterham et al., 2018), and one study found that thwarted belongingness was only associated with suicidal ideation at low levels of perceived burdensomeness for adolescent young women and at high levels of perceived burdensomeness for adolescent young men (Hill et al., 2017). Given these inconsistent findings and our unique focus on LGBTQ+ youth (including transgender individuals) who utilized crisis services, it is difficult to compare findings across studies.

That said, our findings suggest that the IPTS can be used to explain suicidal ideation among LGBTQ+ youth, particularly sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender individuals. In general, women are socialized to place greater importance on interpersonal relationships than men (Rose & Rudolph, 2006), and IPTS factors may be particularly likely to contribute to suicidal ideation for women because they may be more strongly impacted by interpersonal challenges (Batterham et al., 2018). In regard to transgender youth, when they feel like a burden on others or when they feel like they do not belong, they may feel hopeless about these experiences ever changing because of the pervasiveness of societal stigma against transgender people. In turn, this interpersonal hopelessness may exacerbate the effects of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on suicidal ideation (Tucker et al., 2018). Our findings cannot speak to why perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were not associated with suicidal ideation among sexual minority cisgender young men, but it is noteworthy that they reported the lowest levels of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation out of our three gender groups. A previous study also found that adolescent young men reported lower levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness than adolescent young women (Hill et al., 2017), which the authors attributed to differences in how young men and young women are socialized (e.g., young women are socialized to place greater importance on interpersonal relationships than young men; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As such, traditional gender socialization may have influenced sexual minority cisgender young men’s experiences of and reactions to perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. It is also possible that the sexual minority cisgender young men in our sample had experiences that protected them from the negative consequences of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (e.g., they may have had greater social support and/or greater connection to other LGBTQ+ youth). That said, our findings highlight the importance of intervening on perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness among young cisgender women and transgender individuals, as well as on identifying protective factors that buffer these associations in these populations.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of the current study. First, all of our participants had contacted a national suicide prevention hotline for LGBTQ+ youth. Although it is particularly important to examine risk factors related to suicidal ideation in samples of LGBTQ+ youth who utilize crisis services (because of their increased risk to begin with), it also limits the extent to which findings generalize to the broader population of LGBTQ+ youth. It is also important to acknowledge that youth who were at imminent risk for suicide (i.e., those who reported a suicide plan with intent to act on it within 48 h) were not offered the opportunity to participate in the study. As such, while our sample was considered high risk because everyone had utilized crisis services, it did not include those who were at greatest risk. However, given low rates of callers reporting imminent risk at screening (<1%), it is unlikely that this criterion biased our sample. Second, the majority of our participants were White. Although race/ethnicity was not significantly associated with perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, or suicidal ideation in our sample, it will be important to replicate the results of the current study in a more diverse sample of LGBTQ+ youth. Third, we combined all of the gender minority youth into a single group because there were too few participants in each subgroup (e.g., transgender young women, transgender young men, and genderqueer youth) to consider them as separate groups in analyses. Given that we found evidence of gender differences in the associations between the IPTS factors and suicidal ideation, it will important to continue to examine these associations in larger samples of gender minority youth. Fourth, we did not test the full IPTS model, and future work should test all three factors, including acquired capability. Finally, although the use of a prospective design was a major strength of the current study, there was only 1 month in between the two assessments, and it will be important to continue to examine the extent to which perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness influence suicidal ideation over different periods of time among LGBTQ+ youth.

Limitations aside, the current study is the first to demonstrate that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are prospectively associated with greater suicidal ideation among LGBTQ+ youth who utilized crisis services. Our findings suggest that perceived burdensomeness might be more important than thwarted belongingness in understanding suicidal ideation in this population. Furthermore, our findings suggest that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may contribute more strongly to suicidal ideation among sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender individuals than sexual minority cisgender young men. These findings have important implications for suicide prevention and intervention with LGTBQ+ youth. They suggest that clinicians should assess perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and intervene, as necessary, when working with LGBTQ+ youth, especially sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender individuals. Few studies have specifically tested interventions designed to reduce perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. However, Allan et al. (2018) developed a brief intervention that combined strategies from cognitive behavior therapy (CBT; e.g., psychoeducation and behavioral activation) and cognitive bias modification (CBM), with the goals of correcting problematic thinking and behavior, reducing isolation and feelings of burdensomeness, and training participants to generate positive outcomes in response to ambiguous scenarios. They found that the intervention led to reductions in perceived burdensomeness relative to a brief phone check-in (including a suicide risk assessment), which in turn led to a lower incidence of suicidal ideation over time. Although they tested the intervention in a sample of presumably heterosexual adults, their findings suggest that clinicians may be able to draw on strategies from CBT and CBM to target perceived burdensomeness. A separate study used a randomized controlled trial design to examine a computerized intervention aimed at decreasing perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in veterans (Short et al., 2019). The authors found that the intervention, which consisted of psychoeducation and cognitive bias modification, led to decreased IPTS levels, in turn reducing suicidality (Short et al., 2019). Although this intervention has not been examined in LGBTQ+ youth, research suggests that digital interventions hold promise for meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth (Steinke et al., 2017). In addition, clinicians could help LGBTQ+ youth meet others who share their identities in an effort to increase community connectedness and reduce feelings of thwarted belongingness. School-based gender and sexuality alliances (also referred to as gay–straight alliances) and community-based LGBTQ+ organizations may be particularly helpful in facilitating connections to LGBTQ+ peers. In sum, based on the current findings, reducing perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness has the potential to reduce suicidal ideation among high-risk LGBTQ+ youth, especially sexual minority cisgender young women and transgender individuals. Still, additional research is needed to continue to advance our understanding of the extent to which the IPTS can explain suicidality across subgroups of LGBTQ+ youth and to continue to inform suicide prevention and intervention approaches for this diverse population.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank our participants who generously shared their time and experience for the purposes of this research.

Funding information

The collection of data for this study was funded by The Trevor Project through a contract to Jeremy T. Goldbach at the University of Southern California. Brian Feinstein’s time was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K08DA045575; PI: Feinstein). Christina Dyar’s time was also supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01DA046716; PI: Dyar). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Allan NP, Boffa JW, Raines AM, & Schmidt NB (2018). Intervention related reductions in perceived burdensomeness mediates incidence of suicidal thoughts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 282–288. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.02.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Dubas JS, Russell ST, Buikema RL, & van Aken MAG (2018). Minority stress, perceived burdensomeness, and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth. Journal of Adolescence, 66, 9–18. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Grossman AH, & Russell ST (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51, 688–696. 10.1037/a0038994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, & Wheelwright S. (2004). The empathy quotient: An investigation of adults with Asperger Syndrome or high functioning Autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 163–175. 10.1023/B:JADD.0000022607.19833.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr SM, Budge SL, & Adelson JL (2016). Transgender community belongingness as a mediator between strength of transgender identity and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 87–97. 10.1037/cou0000127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay S, Apter A, Snir A, Carli V, Hoven CW, Sarchiapone M, Hadlaczky G, Balazs J, Kereszteny A, Brunner R, Kaess M, Bobes J, Saiz PA, Cosman D, Haring C, Banzer R, McMahon E, Keeley H, Kahn J-P, … Wasserman D. (2019). A longitudinal examination of the interpersonal theory of suicide and effects of school-based suicide pr evention interventions in a multinational study of adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(10), 1104–1111. 10.1111/jcpp.13119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batterham PJ, Walker J, Leach LS, Ma J, Calear AL, & Christensen H. (2018). A longitudinal test of the predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour for passive and active suicidal ideation in a large community-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 97–102. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks VR (1981). Minority stress and lesbian women. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2016). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 65, 1–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Injury prevention & control: Data & statistics (WISQARS). July 24, 2020, Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html

- Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Mackinnon AJ, Donker T, & Soubelet A. (2014). Predictors of the risk factors for suicide identified by the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behaviour. Psychiatry Research, 219(2), 290–297. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Tucker RP, Hagan CR, Rogers ML, Podlogar MC, Chiurliza B, Ringer FB, Michaels MS, Patros C, & Joiner TE (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. 10.1037/bul0000123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SC, & Heron M. (2019). Death rates due to suicide and homicide among persons aged 10–24: United States, 2000–2017. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db352.htm#Suggested_citation [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Giacomo E, Krausz M, Colmegna F, Aspesi F, & Clerici M. (2018). Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(12), 1145–1152. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder D. (1985). The cycle of popularity: Interpersonal relations among female adolescents. Sociology of Education, 58, 154–165. 10.2307/2112416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, & D’Augelli AR (2007). Transgender youth and life-threatening behaviors. Suicide & life-threatening Behavior, 37(5), 527–537. 10.1521/suli.2007.37.5.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, Park JY, & Russell ST (2016). Transgender youth and suicidal behaviors: Applying the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 20(4), 329–349. 10.1080/19359705.2016.1207581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, Valido A, De Pedro KT, Huang Y, & Espelage DL (2019). Minority stress among transgender adolescents: The role of peer victimization, school belonging, and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 10.13140/RG.2.2.27890.40646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman JL, Haas AP, & Rodgers PL (2014). Suicide attempts among transgender and gender non-conforming adults. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xg8061f [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Hatkevich C, Pettit JW, & Sharp C. (2017). Gender and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide: A three-way interaction between perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and gender. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36(10), 799–813. 10.1521/jscp.2017.36.10.799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, & Pettit JW (2012). Suicidal ideation and sexual orientation in college students: The roles of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and perceived rejection due to sexual orientation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(5), 567–579. 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Rey Y, Marin CE, Sharp C, Green KL, & Pettit JW (2015). Evaluating the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire: Comparison of the reliability, factor structure, and predictive validity across five versions. Suicide & life-threatening Behavior, 45(3), 302–314. 10.1111/sltb.12129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr., Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, & Rudd MD (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634–646. 10.1037/a0016500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, & Han J. (2016). A systematic review of the predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 34–45. 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, Thoma BC, Murray PJ, D’Augelli AR, & Brent DA (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 49(2), 115–123. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, & Muthen B. (2012). 1998–2012. Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthen & Muthen. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam E, Kessler RC, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, … Williams D. (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(2), 98–105. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, & Kessler RC (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300–310. 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate AR, & Anestis MD (2019). Comparison of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, capability for suicide, and suicidal ideation among heterosexual and sexual minority individuals in Mississippi. Archives of Suicide Research, 1–17, 10.1080/13811118.2019.1598525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, & Fartacek R. (2005). Suicidality and associated risk factors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual compared to heterosexual Austrian adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 661–670. 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek R, & Kralovec K. (2014). Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1559–1570. 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen SA, & Mann JJ (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of young women and young men. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98. 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salentine CM, Hilt LM, Muehlenkamp JJ, & Ehlinger PP (2020). The link between discrimination and worst point suicidal ideation among sexual and gender minority adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(1), 19–28. 10.1111/sltb.12571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon K, Travers R, Coleman T, Bauer G, & Boyce M. (2010). Ontario’s trans communities and suicide: Transphobia is bad for our health. Trans Pulse E-Bulletin, 1(2). November 12. Retrieved from http://transpulse.ca/documents/E2English.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Short NA, Stentz L, Raines AM, Boffa JW, & Schmidt NB (2019). Intervening on thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness to reduce suicidality among veterans: Subanalyses from a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 50(5), 886–897. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinke J, Root-Bowman M, Estabrook S, Levine DS, & Kantor LM (2017). Meeting the needs of sexual and gender minority youth: Formative research on potential digital health interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 541–548. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SM, Eaddy M, Horton SE, Hughes J, & Kennard B. (2017). The validity of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide in adolescence: A review. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 437–449. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1020542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker RP, Hagan CR, Hill RM, Slish ML, Bagge CL, Joiner TE Jr., & Wingate LR (2018). Empirical extension of the interpersonal theory of suicide: Investigating the role of interpersonal hopelessness. Psychiatry Research, 259, 427–432. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197–215. 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolford-Clevenger C, Frantell KA, Brem MJ, Garner A, Rae Florimbio A, Grigorian H, Shorey RC, & Stuart GL (2020). Suicide ideation among Southern U.S. Sexual minority college students. Death Studies, 44(4), 223–229. 10.1080/07481187.2018.1531088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Wingate L, Gray TW, & Pantalone DW (2014). Evaluating thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as predictors of suicidal ideation in sexual minority adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(3), 234–243. 10.1037/sgd0000046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]