Abstract

Purpose of Review

Chronic pain is common in people living with HIV (PLWH). It causes significant disability and poor HIV outcomes. Despite this, little is understood about its etiology and management.

Recent Findings

Recent studies suggest that chronic pain in PLWH is caused by inflammation that persists despite viral load suppression. This coupled with central sensitization and psychosocial factors leads to chronic pain that is difficult to manage. PLWH with chronic pain often feel that their pain is incompletely treated, and yet there are few evidence-based options for the management of chronic pain in PLWH. Recent studies suggest that an approach pairing pharmacotherapy and nonpharmacologic therapy may address the complex nature of chronic in PLWH.

Summary

Chronic pain in PLWH is common yet poorly understood. Further research is needed in order to better understand the etiology of chronic pain and its optimal management.

Keywords: HIV, Chronic pain, Pain, Biopsychosocial, Biopsychosocial model

Introduction

People living with HIV (PLWH) have a high burden of chronic pain. Estimates of the prevalence of chronic pain in PLWH range from 25 to 85% [1–10]; this is higher than estimates of prevalence of chronic pain in the general population [11]. Chronic pain is defined as pain that continues for longer than 3–6 consecutive months, beyond the typical period of normal tissue healing [12]. It may manifest in PLWH in different ways, including but not limited to chronic low back pain, headaches, peripheral neuropathy, and fibromyalgia [13]. Chronic pain severely impacts quality of life in PLWH, and is associated with functional impairment, poor retention in care, poor antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, and virologic failure [14–18]. PLWH list chronic pain as a major health priority [19, 20].

With the development, advancement, and widespread distribution of ART, the focus of care for PLWH shifted from the management of acute illness to the management of chronic manifestations of HIV infection [21]. In this context, there is an increasing recognition of the importance of chronic pain in HIV from clinical and research communities [22, 23]. Despite this, knowledge of the etiology and optimal management of chronic pain in PLWH remains poorly understood [22]. In this article, we review existing literature on the epidemiology, etiology, and management of chronic pain in PLWH.

Epidemiology

Chronic pain in PLWH has traditionally been tied to neurotoxic ART prescribed broadly in the early era of ART [24]. However, despite advancements in ART and improved control of HIV overall, chronic pain has persisted as a prominent health concern for PLWH [25, 26]. Some studies have characterized the epidemiology of general pain [1, 5, 7, 27, 28], but few have examined chronic pain in PLWH. In those studying chronic pain, prevalence varies greatly depending upon the cohort [8, 9, 13, 29, 30]. For example, in one sample of homeless PLWH living in an urban setting, 90% endorsed chronic pain [8]. In contrast, in a cohort of PLWH in care in Lweza, Uganda, only 21.5% of participants reported chronic pain [9]. This large variability is likely due to differences in how chronic pain was measured and clinical differences between cohorts.

Chronic pain in PLWH is more common in older patients and with complex medical, psychiatric, and substance use comorbidities [7, 13, 31]. It is associated with substantially diminished health outcomes, including increased healthcare utilization and greater odds of functional impairment [13, 14]. PLWH with chronic pain are more likely to have poor retention in care and poor ARV adherence and are ultimately more likely to experience virologic failure when compared with their counterparts who do not have chronic pain [7, 17, 18, 32]. Most PLWH with chronic pain experience musculoskeletal pain and neuropathic pain and many have multisite pain, reporting a median of 2–5 sites of pain [8, 13, 33–35].

Types of Chronic Pain in PLWH

Chronic pain in PLWH commonly falls into one of two categories: neuropathic or non-neuropathic [30, 33, 36]. Non-neuropathic pain generally refers to musculoskeletal pain and can also include other etiologies like multi-site pain and headaches [23]. Neuropathic pain was the first chronic pain syndrome associated with HIV, caused by exposure to nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), the earliest of life-saving ART available to PLWH [37]. NRTIs cause neuropathic pain through interference of mitochondrial DNA replication and subsequent mitochondrial depletion [38]. Some also cause mitochondrial toxicity through inhibition of mitochondrial membrane potential [38]. Ultimately, mitochondrial dysfunction causes loss of oxidative respiration of affected tissues, which then causes neurotoxicity [38]. Since the lifespan of PLWH has extended and ART has advanced to safer drugs with lower likelihood of mitochondrial toxicity and neuropathy, non-neuropathic pain has emerged as a cause of morbidity in this population [37].

Neuropathic Pain

Neuropathic pain in PLWH is usually described as dysesthetic pain that is located in a stocking-and-glove distribution on distal extremities, and typically affects the feet more than the hands. It is associated with a painful response to light touch [39]. Neuropathic pain can be a complication of HIV infection, of other viral infections, such as postherpetic neuralgia following varicella zoster infection, and from other conditions such as diabetes mellitus, alcohol use disorder, and multiple myeloma.

The exact etiology of HIV-associated neuropathy is incompletely understood. In earlier years of the HIV pandemic, neuropathic pain was associated with the use of neurotoxic dideoxynucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. In modern HIV care, we phased out this class of ART and replaced them with less toxic ART. It was also associated with opportunistic infections experienced by PLWH with end-stage disease [23]. Since then, with ART more widely available, fewer PLWH experience opportunistic infections as they did in earlier years of the AIDS epidemic [40]. Despite this, estimates of the prevalence of HIV-associated neuropathic pain range from 13 to 50% [41–43]. In a recent multi-national study following PLWH and people without HIV over 192 weeks, peripheral neuropathy was more common in PLWH than in HIV-uninfected individuals at baseline. As PLWH achieved HIV viral load suppression with ART, incidence of neuropathic pain decreased, suggesting that viremia is related to neuropathic pain [44]. These findings are preceded by studies in other cohorts of PLWH that found that severity of neuropathic pain was associated with HIV viremia [45–47].

There are reports of neuropathic pain persisting despite viral load suppression [24, 48]. Some hypothesize that chronic pain despite HIV viral load suppression is due to central sensitization in which the brain receives a strong signal of pain when there is no peripheral tissue injury present [12]. Some findings suggest that peripheral neurons experience inflammation indirectly through HIV-infected monocyte-macrophage lineage cells that excrete inflammatory cytokines [24, 49–51]. Inflammation persists in many, even with viral load suppression [52, 53]. This is a picture seen in other chronic pain illnesses such as fibromyalgia. Further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between HIV viremia, inflammation, other mediators, and neuropathic pain.

Non-neuropathic Pain

Non-neuropathic pain in PLWH can present in many different ways, including chronic low back pain, osteoarthritis, and multi-site pain [13, 54, 55]. In some cohorts, musculoskeletal pain is more common than neuropathic pain [13]. Non-neuropathic pain in PLWH is poorly studied. Musculoskeletal pain is common in multiple different cohorts of PLWH [13, 55, 56]. The etiologies of non-neuropathic pain in PLWH are disparate. Some are specific to HIV, such as avascular necrosis and osteoporosis with subsequent fracture [57], while others are less specific to HIV such as lumbosacral pain [13] and fibromyalgia [55]. In cohorts of patients with multi-site and non-neuropathic pain, elevated inflammatory cytokines were associated with increasing age and with worsening measures of chronic pain [52, 53]. Multi-site pain is associated with long duration of exposure to HIV, immuno-suppression, and exposure to many different ART [58]. Some hypothesize that much like neuropathic pain, non-neuropathic chronic pain in PLWH is secondary to inflammation secondary to HIV-infection despite viral load suppression.

Other Factors That Contribute to Chronic Pain in PLWH

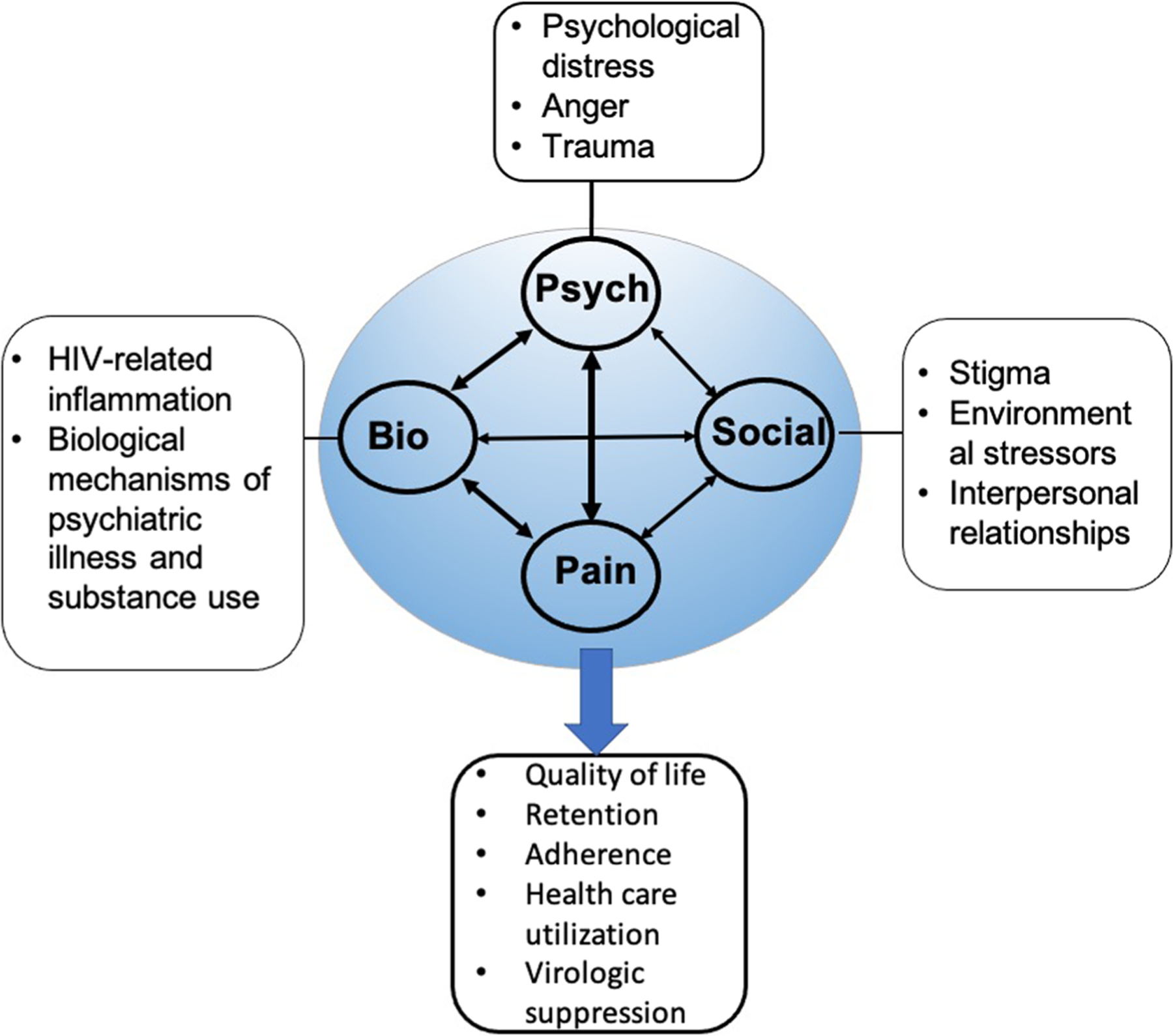

The Biopsychosocial (BPS) framework of chronic pain in PLWH is a conceptual framework to understand how chronic pain is related to a combination of factors, such as HIV viremia, inflammation, psychiatric diagnoses, substance use, stigma, and health behaviors (Fig. 1) [59]. One reason for why chronic pain is so poorly understood in PLWH is because its etiology is likely secondary to multiple factors that converge to cause chronic pain, and subsequently poor clinical outcomes, which in turn compound symptoms of chronic pain further. Some criticize this framework as being difficult to measure the weighted contribution of each construct; however, there is growing evidence of the bidirectional relationship between biopsychosocial factors and chronic pain in HIV [31, 60]. For example, increasing chronic pain severity is associated with worsening insomnia and depressive symptoms in PLWH [18, 31, 60]. This pattern is also seen with chronic pain severity and anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, opioid use disorder, and risky alcohol use in PLWH [60, 61]. Additionally, depression and anxiety are related to inflammation, much like pain is related to increased inflammation in PLWH [62].

Fig. 1.

Adapted Biopsychosocial framework for chronic pain in HIV (Merlin, Pain Practice 2013)

Chronic pain, both neuropathic and non-neuropathic, in PLWH is also associated with poor adherence to ART and missed HIV clinic visits [7, 60, 63]. When considering the etiology of chronic pain and its clinical implications in PLWH, it is important to take into consideration the reciprocal relationship of chronic pain and biopsychosocial factors.

Management of Chronic Pain in PLWH

Chronic pain in PLWH has historically been undertreated and remains so [23, 56]. This is especially true in women, people with a history of substance use disorder, and those with low socioeconomic status [35, 64–66]. Both pain and HIV are heavily stigmatized conditions, and many PLWH with chronic pain feel a lack of validation of symptoms and dismissal by family members and healthcare providers [67]. Patients may even experience internalized stigma, which can lead to patients feeling devalued and inferior to their counterparts without chronic pain [66].

When approaching management of chronic pain in PLWH, it is important to take into account the BPS framework (Fig. 1) and understand that many different factors may be involved in the experience of pain. Management of chronic pain in PLWH can include both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatments.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Pharmacologic treatments for the management of chronic pain in PLWH are poorly studied. Few if any studies focus on PLWH and the ones that do have small sample sizes or were inconclusive [23]. In this setting, for many years, chronic neuropathic pain and nonneuropathic pain were treated with chronic opioid therapy, with higher proportions of PLWH than people without HIV prescribed opioids in several cohorts [68]. Over the past decade, there has been a paradigm shift in the use of opioids for chronic pain in all populations, including PLWH [69]. Due to the growing recognition of the risk of opioid use disorder and risk of opioid overdose, recommendations strongly advise against the use of opioids for the management of chronic pain and emphasize the use on nonopioid therapy [23, 69].

The remaining pharmacologic management of chronic pain relies on the use of medications with little evidence. Neuropathic pain is managed with anticonvulsants like gabapentin and antidepressants like serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) [23]. There is some evidence that capsaicin cream co-administered with lidocaine cream is effective for neuropathic pain in HIV [70].

Medical cannabis is a promising potential pharmacotherapeutic for the management of chronic pain in HIV. In studies of PLWH living in the USA and Canada, up to one-third of patients use cannabis—both medical and recreational [71–75]. In both qualitative and quantitative studies, PLWH describe using cannabis for the management of pain, alone and in conjunction with other pharmacotherapies [71, 76, 77]. Studies testing medical cannabis for pain in PLWH focus on neuropathic pain [78, 79] and found that medical cannabis reduces pain more than placebo. In other populations, multiple systematic reviews found that medical cannabis is an effective analgesic [80, 81]. Despite this, there remains significant gaps in our understanding of most appropriate use of medical cannabis, including dosing and frequency. As medical cannabis becomes increasingly available to patients through legislative action [82], there is increasing pressure to understand how to use medical cannabis safely and effectively in PLWH.

Non-pharmacologic Treatment

Non-pharmacologic treatments are important to be used in conjunction with pharmacologic treatment in PLWH with chronic pain [23]. It is particularly useful to address psychosocial aspects of chronic pain. One example is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that can be useful to help identify behaviors that could be making pain worse (e.g., exercise avoidance) and develop coping strategies for anxiety related to pain [83]. Few studies examine CBT in PLWH, and those that did were not specifically tailored to the population [23, 84, 85]. Further research is needed to identify and test patient-centric nonpharmacological interventions in PLWH for the management of chronic pain.

Conclusions

Chronic pain is a major health complication in PLWH. Despite this, the etiology and management of chronic pain is incompletely understood. This paper provided a summary of the epidemiology, etiologies, and management of chronic pain in PLWH. With an aging population of PLWH [86], chronic symptoms and illnesses will continue to be the predominant health concern of PLWH. Given the many health consequences of chronic pain in PLWH, including poor HIV outcomes and engagement in care, it is essential that research in the etiology of chronic pain in PLWH is prioritized. With an improved understanding of the etiologies of chronic pain in PLWH, therapeutics can be targeted to maximize their efficacy and safety.

Future research should ensure that there is adequate representation of traditionally under-represented populations in research on chronic pain in PLWH including women and minorities and ensure that the BPS framework is considered to accurately capture the complexity of chronic pain in PLWH. A Global Task Force on Chronic Pain in PLWH recently published a scientific agenda to identify gaps in knowledge on chronic pain with the aim of advancing research in this field that can be implemented clinically [22]. Efforts such as these with adequate stakeholder engagement provide hope that future studies will fill gaps in our knowledge of chronic pain in PLWH and how to manage it.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Complications of HIV and Antiretroviral Therapy

References

- 1.Merlin JS, Cen L, Praestgaard A, Turner M, Obando A, Alpert C, et al. Pain and physical and psychological symptoms in ambulatory HIV patients in the current treatment era. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(3):638–45. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newshan G, Bennett J, Holman S. Pain and other symptoms in ambulatory HIV patients in the age of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2002;13(4):78–83. 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harding R, Lampe FC, Norwood S, Date HL, Clucas C, Fisher M, et al. Symptoms are highly prevalent among HIV outpatients and associated with poor adherence and unprotected sexual intercourse. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(7):520–4. 10.1136/sti.2009.038505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverberg MJ, Jacobson LP, French AL, Witt MD, Gange SJ. Age and racial/ethnic differences in the prevalence of reported symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons on antiretroviral therapy. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;38(2):197–207. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervia LD, McGowan JP, Weseley AJ. Clinical and demographic variables related to pain in HIV-infected individuals treated with effective, combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). Pain Med. 2010;11(4):498–503. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee KA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, Coggins T, Davis H, Pullinger CR, et al. Symptom experience in HIV-infected adults: a function of demographic and clinical characteristics. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2009;38(6):882–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Raper JL, Zinski A, Norton WE, Willig JH, et al. Pain, mood, and substance abuse in HIV: implications for clinic visit utilization, antiretroviral therapy adherence, and virologic failure. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(2):164–70. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182662215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miaskowski C, Penko JM, Guzman D, Mattson JE, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Occurrence and characteristics of chronic pain in a community-based cohort of indigent adults living with HIV infection. J Pain. 2011;12(9):1004–16. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mwesiga EK, Kaddumukasa M, Mugenyi L, Nakasujja N. Classification and description of chronic pain among HIV positive patients in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19(2):1978–87. 10.4314/ahs.v19i2.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azagew AW, Woreta HK, Tilahun AD, Anlay DZ. High prevalence of pain among adult HIV-infected patients at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2461–9. 10.2147/jpr.S141189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1230–9. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merlin JS. Chronic pain in patients with HIV infection: what clinicians need to know. Top Antivir Med. 2015;23(3):120–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiao JM, So E, Jebakumar J, George MC, Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J. Chronic pain disorders in HIV primary care: clinical characteristics and association with healthcare utilization. Pain. 2016;157(4):931–7. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Chamot E, Overton ET, Willig JH, Ritchie C, et al. Pain is independently associated with impaired physical function in HIV-infected patients. Pain Med. 2013;14(12):1985–93. 10.1111/pme.12255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Passik SD, Thaler H, Portenoy RK. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. II: Impact of pain on psychological functioning and quality of life. Pain. 1996;68(2–3):323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breitbart W, McDonald MV, Rosenfeld B, Passik SD, Hewitt D, Thaler H, et al. Pain in ambulatory AIDS patients. I: Pain characteristics and medical correlates. Pain. 1996;68(2–3):315–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Levi-Minzi MA, Cicero TJ, Tsuyuki K, O’Grady CL. Pain treatment and antiretroviral medication adherence among vulnerable HIV-positive patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(4):186–92. 10.1089/apc.2014.0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merlin JS, Long D, Becker WC, Cachay ER, Christopoulos KA, Claborn K, et al. Brief report: the association of chronic pain and long-term opioid therapy with HIV treatment outcomes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79(1):77–82. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredericksen RJ, Fitzsimmons E, Gibbons LE, Loo S, Dougherty S, Avendano-Soto S, et al. How do treatment priorities differ between patients in HIV care and their providers? A mixed-methods study. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(4):1170–80. 10.1007/s10461-019-02746-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bristowe K, Clift P, James R, Josh J, Platt M, Whetham J, et al. Towards person-centred care for people living with HIV: what core outcomes matter, and how might we assess them? A cross-national multi-centre qualitative study with key stakeholders. HIV Med. 2019;20(8):542–54. 10.1111/hiv.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liddy C, Shoemaker ES, Crowe L, Boucher LM, Rourke SB, Rosenes R, et al. How the delivery of HIV care in Canada aligns with the Chronic Care Model: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0220516. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merlin JS, Hamm M, de Abril CF, Baker V, Brown DA, Cherry CL, et al. SPECIAL ISSUE HIV and CHRONIC PAIN (The Global Task Force for Chronic Pain in People with HIV (PWH): developing a research agenda in an emerging field). AIDS Care. 2021:1–9. 10.1080/09540121.2021.1902936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruce RD, Merlin J, Lum PJ, Ahmed E, Alexander C, Corbett AH, et al. 2017 HIVMA of IDSA clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic pain in patients living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(10):e1–e37. 10.1093/cid/cix636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aziz-Donnelly A, Harrison TB. Update of HIV-associated sensory neuropathies. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2017;19(10):36. 10.1007/s11940-017-0472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherry CL, Wadley AL, Kamerman PR. Painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy. Pain Manag. 2012;2(6):543–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth K, Affandi JS, McArthur JC, Bowtell-Harris C, Mijch AM, Watson K, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for HIV-associated neuropathy in Melbourne, Australia 1993–2006. HIV Med. 2007;8(6):367–73. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sabin CA, Harding R, Bagkeris E, Nkhoma K, Post FA, Sachikonye M, et al. Pain in people living with HIV and its association with healthcare resource use, well being and functional status. Aids. 2018;32(18):2697–706. 10.1097/qad.0000000000002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aouizerat BE, Miaskowski CA, Gay C, Portillo CJ, Coggins T, Davis H, et al. Risk factors and symptoms associated with pain in HIV-infected adults. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(2):125–33. 10.1016/j.jana.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uebelacker LA, Weisberg RB, Herman DS, Bailey GL, Pinkston-Camp MM, Stein MD. Chronic pain in HIV-infected patients: relationship to depression, substance use, and mental health and pain treatment. Pain Med. 2015;16(10):1870–81. 10.1111/pme.12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson A, Condon KD, Mapas-Dimaya AC, Schrager J, Grossberg R, Gonzalez R, et al. Report of an HIV clinic-based pain management program and utilization of health status and health service by HIV patients. J Opioid Manag. 2012;8(1):17–27. 10.5055/jom.2012.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cody SL, Hobson JM, Gilstrap SR, Gloston GF, Riggs KR, Justin Thomas S, et al. Insomnia severity and depressive symptoms in people living with HIV and chronic pain: associations with opioid use. AIDS Care. 2021:1–10. 10.1080/09540121.2021.1889953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safo SA, Blank AE, Cunningham CO, Quinlivan EB, Lincoln T, Blackstock OJ. Pain is associated with missed clinic visits among HIV-positive women. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1782–90. 10.1007/s10461-016-1475-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry BA, Westfall AO, Molony E, Tucker R, Ritchie C, Saag MS, et al. Characteristics of an ambulatory palliative care clinic for HIV-infected patients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(8):934–7. 10.1089/jpm.2012.0451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namisango E, Harding R, Atuhaire L, Ddungu H, Katabira E, Muwanika FR, et al. Pain among ambulatory HIV/AIDS patients: multicenter study of prevalence, intensity, associated factors, and effect. J Pain. 2012;13(7):704–13. 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker R, Jelsma J, Stein DJ. Pain in amaXhosa women living with HIV/AIDS: a cross-sectional study of ambulant outpatients. BMC Womens Health. 2017;17(1):31. 10.1186/s12905-017-0388-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Önen NF, Barrette EP, Shacham E, Taniguchi T, Donovan M, Overton ET. A review of opioid prescribing practices and associations with repeat opioid prescriptions in a contemporary outpatient HIV clinic. Pain Pract. 2012;12(6):440–8. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madden VJ, Parker R, Goodin BR. Chronic pain in people with HIV: a common comorbidity and threat to quality of life. Pain Manag. 2020;10(4):253–60. 10.2217/pmt-2020-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roda RH, Hoke A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-induced peripheral neuropathy. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2019;145:67–82. 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gierthmühlen J, Baron R. Neuropathic pain. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(5):462–8. 10.1055/s-0036-1584950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brooks JT, Kaplan JE, Holmes KK, Benson C, Pau A, Masur H. HIV-associated opportunistic infections–going, going, but not gone: the continued need for prevention and treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):609–11. 10.1086/596756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lichtenstein KA, Armon C, Baron A, Moorman AC, Wood KC, Holmberg SD. Modification of the incidence of drug-associated symmetrical peripheral neuropathy by host and disease factors in the HIV outpatient study cohort. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(1):148–57. 10.1086/426076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morgello S, Estanislao L, Simpson D, Geraci A, DiRocco A, Gerits P, et al. HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: the Manhattan HIV Brain Bank. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(4):546–51. 10.1001/archneur.61.4.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simpson DM, Kitch D, Evans SR, McArthur JC, Asmuth DM, Cohen B, et al. HIV neuropathy natural history cohort study: assessment measures and risk factors. Neurology. 2006;66(11):1679–87. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000218303.48113.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vecchio AC, Marra CM, Schouten J, Jiang H, Kumwenda J, Supparatpinyo K, et al. Distal sensory peripheral neuropathy in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-positive individuals before and after antiretroviral therapy initiation in diverse resource-limited settings. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(1):158–65. 10.1093/cid/ciz745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simpson DM, Brown S, Tobias JK, Vanhove GF. NGX-4010, a capsaicin 8% dermal patch, for the treatment of painful HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy: results of a 52-week open-label study. Clin J Pain. 2014;30(2):134–42. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318287a32f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Childs EA, Lyles RH, Selnes OA, Chen B, Miller EN, Cohen BA, et al. Plasma viral load and CD4 lymphocytes predict HIV-associated dementia and sensory neuropathy. Neurology. 1999;52(3):607–13. 10.1212/wnl.52.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bacellar H, Muñoz A, Miller EN, Cohen BA, Besley D, Selnes OA, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of HIV-1-related neurologic diseases: Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, 1985–1992. Neurology. 1994;44(10):1892–900. 10.1212/wnl.44.10.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamerman PR, Moss PJ, Weber J, Wallace VCJ, Rice ASC, Huang W. Pathogenesis of HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: evidence from in vivo and in vitro experimental models. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2012;17(1):19–31. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Watt JJ, Wilkinson KA, Wilkinson RJ, Heckmann JM. Plasma cytokine profiles in HIV-1 infected patients developing neuropathic symptoms shortly after commencing antiretroviral therapy: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:71. 10.1186/1471-2334-14-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi Y, Shu J, Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, Tang SJ. Wnt signaling in the pathogenesis of human HIV-associated pain syndromes. J NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2013;8(4):956–64. 10.1007/s11481-013-9474-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi Y, Gelman BB, Lisinicchia JG, Tang SJ. Chronic-pain-associated astrocytic reaction in the spinal cord dorsal horn of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. J Neurosci. 2012;32(32):10833–40. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5628-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slawek DE, Merlin JS, Owens MA, Long DM, Gonzalez CE, White DM, et al. Increasing age is associated with elevated circu- lating interleukin-6 and enhanced temporal summation of mechanical pain in people living with HIV and chronic pain. Pain Rep. 2020;5(6):e859. 10.1097/pr9.0000000000000859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Merlin JS, Westfall AO, Heath SL, Goodin BR, Stewart JC, Sorge RE, et al. Brief report: IL-1β levels are associated with chronic multisite pain in people living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(4):e99–e103. 10.1097/qai.0000000000001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van de Ven NS, Ngalamika O, Martin K, Davies KA, Vera JH. Impact of musculoskeletal symptoms on physical functioning and quality of life among treated people with HIV in high and low resource settings: a case study of the UK and Zambia. PLoS One. 2019;14(5):e0216787. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Demirdal US, Bilir N, Demirdal T. The effect of concomitant fibromyalgia in HIV infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cross-sectional study. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2019;18(1):31. 10.1186/s12941-019-0330-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fink D, Oladele D, Etomi O, Wapmuk A, Musari-Martins T, Agahowa E, et al. Musculoskeletal symptoms and non-prescribed treatments are common in an urban African population of people living with HIV. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(2):285–91. 10.1007/s00296-018-4188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walker-Bone K, Doherty E, Sanyal K, Churchill D. Assessment and management of musculoskeletal disorders among patients living with HIV. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(10):1648–61. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sabin CA, Harding R, Bagkeris E, Geressu A, Nkhoma K, Post FA, et al. The predictors of pain extent in people living with HIV. Aids. 2020;34(14):2071–9. 10.1097/qad.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Merlin JS, Zinski A, Norton WE, Ritchie CS, Saag MS, Mugavero MJ, et al. A conceptual framework for understanding chronic pain in patients with HIV. Pain Pract. 2014;14(3):207–16. 10.1111/papr.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott W, Arkuter C, Kioskli K, Kemp H, McCracken LM, Rice ASC, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with persistent pain in people with HIV: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain. 2018;159(12):2461–76. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeevanjee S, Penko J, Guzman D, Miaskowski C, Bangsberg DR, Kushel MB. Opioid analgesic misuse is associated with incomplete antiretroviral adherence in a cohort of HIV-infected indigent adults in San Francisco. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(7):1352–8. 10.1007/s10461-013-0619-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rivera-Rivera Y, Garcia Y, Toro V, Cappas N, Lopez P, Yamamura Y, et al. Depression correlates with increased plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines and a dysregulated oxidant/antioxidant balance in HIV-1-infected subjects undergoing antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2014;5(6). 10.4172/2155-9899.1000276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mitchell MM, Nguyen TQ, Maragh-Bass AC, Isenberg SR, Beach MC, Knowlton AR. Patient-provider engagement and chronic pain in drug-using, primarily African American persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(6):1768–74. 10.1007/s10461-016-1592-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tsao JC, Stein JA, Dobalian A. Sex differences in pain and misuse of prescription analgesics among persons with HIV. Pain Med. 2010;11(6):815–24. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00858.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parker R, Stein DJ, Jelsma J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):18719. 10.7448/ias.17.1.18719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodin BR, Owens MA, White DM, Strath LJ, Gonzalez C, Rainey RL, et al. Intersectional health-related stigma in persons living with HIV and chronic pain: implications for depressive symptoms. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup2):66–73. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1468012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95. 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Merlin JS, Tamhane A, Starrels JL, Kertesz S, Saag M, Cropsey K. Factors associated with prescription of opioids and co-prescription of sedating medications in individuals with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(3):687–98. 10.1007/s10461-015-1178-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45. 10.1001/jama.2016.1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown S, Simpson DM, Moyle G, Brew BJ, Schifitto G, Larbalestier N, et al. NGX-4010, a capsaicin 8% patch, for the treatment of painful HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy: integrated analysis of two phase III, randomized, controlled trials. AIDS Res Ther. 2013;10(1):5. 10.1186/1742-6405-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lake S, Walsh Z, Kerr T, Cooper ZD, Buxton J, Wood E, et al. Frequency of cannabis and illicit opioid use among people who use drugs and report chronic pain: a longitudinal analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(11):e1002967. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris GE, Dupuis L, Mugford GJ, Johnston L, Haase D, Page G, et al. Patterns and correlates of cannabis use among individuals with HIV/AIDS in Maritime Canada. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2014;25(1):e1–7. 10.1155/2014/301713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pacek LR, Towe SL, Hobkirk AL, Nash D, Goodwin RD. Frequency of cannabis use and medical cannabis use among persons living with HIV in the United States: findings from a nationally representative sample. AIDS Educ Prev. 2018;30(2):169–81. 10.1521/aeap.2018.30.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Slawson G, Milloy MJ, Balneaves L, Simo A, Guillemi S, Hogg R, et al. High-intensity cannabis use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among people who use illicit drugs in a Canadian setting. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):120–7. 10.1007/s10461-014-0847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lake S, Kerr T, Capler R, Shoveller J, Montaner J, Milloy MJ. High-intensity cannabis use and HIV clinical outcomes among HIV-positive people who use illicit drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;42:63–70. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chayama KL, Valleriani J, Ng C, Haines-Saah R, Capler R, Milloy MJ, et al. The role of cannabis in pain management among people living with HIV who use drugs: a qualitative study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021. 10.1111/dar.13294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sohler NL, Starrels JL, Khalid L, Bachhuber MA, Arnsten JH, Nahvi S, et al. Cannabis use is associated with lower odds of prescription opioid analgesic use among HIV-infected individuals with chronic pain. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(10):1602–7. 10.1080/10826084.2017.1416408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ellis RJ, Toperoff W, Vaida F, van den Brande G, Gonzales J, Gouaux B, et al. Smoked medicinal cannabis for neuropathic pain in HIV: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(3):672–80. 10.1038/npp.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Abrams DI, Jay CA, Shade SB, Vizoso H, Reda H, Press S, et al. Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68(7):515–21. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–73. 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.National Conference of State Legislatures. State Medical Marijuana Laws. 2021. Accessed 4/26/2021.

- 83.Sturgeon JA. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2014;7:115–24. 10.2147/prbm.S44762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trafton JA, Sorrell JT, Holodniy M, Pierson H, Link P, Combs A, et al. Outcomes associated with a cognitive-behavioral chronic pain management program implemented in three public HIV primary care clinics. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012;39(2):158–73. 10.1007/s11414-011-9254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Evans S, Fishman B, Spielman L, Haley A. Randomized trial of cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive psychotherapy for HIV-related peripheral neuropathic pain. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(1):44–50. 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Prevention CfDCa. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas. 2017.