Abstract

The hyperaccumulation trait allows some plant species to allocate remarkable amounts of trace metal elements (TME) to their foliage without suffering from toxicity. Utilizing hyperaccumulating plants to remediate TME contaminated sites could provide a sustainable alternative to industrial approaches. A major hurdle that currently hampers this approach is the complexity of the plant-soil relationship. To better anticipate the outcome of future phytoremediation efforts, we evaluated the potential for soil metal-bioavailability to predict TME accumulation in two non-metallicolous and two metallicolous populations of the Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator Arabidopsis halleri. We also examined the relationship between a population’s habitat and its phytoextraction efficiency. Total Zn and Cd concentrations were quantified in soil and plant material, and bioavailable fractions in soil were quantified via Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT). We found that shoot TME accumulation varied independent from both total and bioavailable soil TME concentrations in metallicolous individuals. In fact, hyperaccumulation patterns appear more plant- and less soil-driven: one non-metallicolous population proved to be as efficient in accumulating Zn on non-polluted soil as the metallicolous populations in their highly contaminated environment. Our findings demonstrate that in-situ information on plant phytoextraction efficiency is indispensable to optimize site-specific phytoremediation measures. If successful, hyperaccumulating plant biomass may provide valuable source material for application in the emerging field of green chemistry.

Keywords: Arabidopsis halleri, DGT, hyperaccumulation, phytoextraction efficiency, pseudometallophyte, trace metal elements

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Soil contamination with trace metal elements (TME) acutely threatens the flora and fauna of ecosystems (Khan et al. 2015). Owing to TMEs’ high inherent toxicity even at low concentrations, metalliferous (M) habitats exert a strong selection pressure on plants (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2018; Honjo & Kudoh, 2019; van der Ent et al., 2013). As a result, plants have developed a multitude of mechanisms to tolerate and adapt to excess TME, including reduced TME uptake, increased vacuolar sequestration, advanced repair strategies and/or diverse metal-detoxification processes when colonizing M habitats (Thapa et al., 2012). In contrast, a limited number of species, called hyperaccumulators, are able to accumulate extraordinary amounts of TMEs in shoots without showing any phytotoxicity effects (van der Ent et al., 2013). Physiologically, hyperaccumulation is characterized by increases in TME uptake by roots, translocation to and storage in shoots. In turn, this trait further enhances TME tolerance, making hyperaccumulators hypertolerant to elevated internal concentrations of specific TMEs (Hanikenne & Nouet, 2011).

Hyperaccumulators and their astounding capacity to accumulate TMEs in shoots have practical value for phytoremediation, phytomining and/or biofortification efforts at contaminated sites (Chaney et al., 2007; van der Ent et al., 2015). Phytoremediation provides a low-cost and “green” alternative to industrial approaches, which are currently limited by technical and economical constraints (Mahar et al., 2016). Phytoextraction is the most promising phytoremediation strategy in which TME-(hyper)accumulating plants take up contaminants through their roots, translocate to and accumulate them in the aerial parts (Ali et al., 2013). However, its efficient implementation is currently hampered by several limitations. Firstly, hyperaccumulators are typically small and their biomass production is low compared to crop plants (Hanikenne & Nouet, 2011). Hence, the absolute amount of removed TMEs is often limited by the species’ inherent biology. In addition, whereas many aspects of the hyperaccumulation trait have been extensively reviewed (Honjo & Kudoh, 2019; Lin & Aarts, 2012; Maestri et al., 2010; Rascio & Navari-Izzo, 2011; van der Ent et al., 2013; Verbruggen et al., 2009), the rationale behind this phenomenon remains unclear (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2018). The predictability of TME removal by plants is further complicated by the considerable inter- and intra-specific variation in the hyperaccumulation trait (Gonneau et al., 2014; Stein et al., 2017) and the site-specific effect of the environment (Dietrich et al., 2019; Frérot et al., 2018). The future success of phytoextraction approaches will thus strongly depend on research that strives to refine our understanding of the complex processes underlying the hyperaccumulation trait under real field conditions.

At M sites, soil represents a major environmental resource for plant growth (Frérot et al., 2018), and plant-soil interactions are importantly shaped by soil metal concentration and potential metal toxicity (Soriano-Disla et al., 2018). Finding a method that quickly and reliably assesses soil TME contamination and bioavailability for plants is thus of the utmost importance to ensure the success of future phytoextraction approaches. Diffusive Gradients in Thin-films (DGT) has the potential to become this method. It is used to assess diffusive element supply in aqueous environments by acting as an infinite sink. In natural soils, it estimates elemental supply from the soil solution, as well as resupply from the solid phase (Degryse et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2001). In contrast to soil chemical extractions, DGT accounts for the kinetics of continuous (re-)release from the solid phase (Nolan et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2001). Estimates of bioavailable fractions of TMEs in soils using the DGT method have shown potential to predict plant TME concentrations across a wide range of soils (e.g. Nolan et al. 2005; Tandy et al. 2011), but have rarely been tested in hyperaccumulators. In this context, plants that colonize both non-metalliferous (NM) and M sites, so-called pseudometallophytes, are ideally suited to explore hyperaccumulation and plant-soil feedbacks in habitats with highly contrasting soil TME concentrations (Dechamps et al., 2007).

In this study, we investigated the pseudometallophyte species Arabidopsis halleri (L.) O’Kane and Al-Shehbaz. This perennial, self-incompatible, and outcrossing plant colonizes sites across a large and varied environmental gradient (Honjo & Kudoh, 2019). Due to its species-wide tolerance to high TME concentrations in the soil, paired with its ability to hyperaccumulate zinc (Zn) and cadmium (Cd), A. halleri is an attractive model species to study TME-related traits in plants. Here, we used plant and soil material from two NM and two M locations in Southern Poland to i) assess Zn and Cd hyperaccumulation in metallicolous and non-metallicolous plants, ii) evaluate, if the DGT method is a good predictor of Zn and Cd shoot concentrations in A. halleri, and iii) evaluate the phytoextraction potential of A. halleri populations under natural field conditions. Our findings have broad implications for future advances in phytoremediation that extend beyond the investigated species and sites. Importantly, we highlight that the TME accumulation in plant biomass can be greatly enhanced by selecting specific populations and genotypes with maximal phytoextraction efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study site and sampling

Our sampling included four locations of A. halleri in southern Poland (Figure 1): two M locations at low altitude in the Olkusz region (M_PL22 and M_PL27), one sub-alpine NM location at the northern foothills of the Tatra Mts (NM_PL35), and one NM location at low altitude in Niepołomice Forest (NM_PL14; Figure 1). The distance between sites ranged from 10 to 100 km. The M sites differed regarding their history of industrial activity and source of TME contamination. We investigated the vicinity of the Zn smelter of the Bolesław Mine and the metallurgical plant near Olkusz (M_PL22), and the area of a former open-pit mine in Galman (M_PL27). In M_PL27, mining was intensively developed in the 19th century and continued until 1912, whereas Zn-Pb ore mining in M_PL22 started already in the 13th century and ceased in the 1990s.

Figure 1.

Map of sampling sites in Poland. Non-metalliferous sites are abbreviated “NM” (white circle), metalliferous sites “M” (grey circle).

Existing vegetation was mechanically removed from a small plot (4 x 4 m) at each site in the fall, and ten A. halleri individuals from the local populations were replanted into the plot in the following spring. Plant growth was monitored throughout the growing season. In the fall, plants were harvested together with surrounding soil. Soil was sampled within the root zone of the harvested plants to a depth of 10 cm using a cylinder of 7 cm diameter. Due to mortality events and/or small plant biomass that did not allow for chemical analyses, the final sample size for individual sites was n=7 (M_PL22), n=9 (NM_PL14), and n=10 (NM_PL35 and M_PL27).

2.2. Plant and soil parameters

Upon harvest, plants were divided into shoots and roots, and washed twice in deionized water. Root samples were additionally cleaned in an ultrasonic bath using Milli-Q water (2 min, 30 mHz) and dried at 80°C. Subsequently, shoot (DWshoot) and root (DWroot) dry weight was quantified. Total Zn and Cd concentrations (cT,Zn, cT,Cd) were extracted by digestion of ~0.3 g of shoot and ~0.2 g of root tissue samples in a 6 ml HNO3:HClO4 mixture (4:1 v/v). After overnight soaking of the samples in the acid mixture at room temperature (Zheljazkov & Nielsen, 1996), they were boiled on a hot plate (FOSS Tecator Digestor Auto) at 282 – 284°C for 1.5 – 2h. The samples were entirely digested and the obtained solution did not need filtering. The elements were quantified with flame (Zn in all samples and Cd in samples from M locations) or graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS; Varian AA280FS, AA280Z, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA), with the latter applied to determine Cd at low concentration levels (i.e., in samples from NM locations). The instrumental parameters were adjusted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Table S1). Blank samples were included in the extraction and analysis procedures. The results were ascertained using certified Standard Reference Material 1570a – Spinach Leaves (National Institute of Standards & Technology). The recovery values ranged between 94% and 99%, with RDS ± 0.5%.

Soil pH was measured in a 1:5 (w:v) suspension of soil in deionized water (ISO 10390). Soil texture was determined through a combination of sieving and sedimentation (ISO 11277) and maximum water holding capacity (WHC) was measured according to Öhlinger, 1996. For the analyses of pseudo-total (hereafter total) Zn and Cd concentrations, 0.5 g of dried and ground soil was mineralized in 10 ml HClO4 (Kabala and Karczewska, 2017; Stefanowicz et al. 2020), using a hotplate (FOSS Tecator Digestor Auto). Extracted elements were analyzed with flame furnace AAS (Varian AA280FS, AA280Z, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The instrumental parameters were as described above and in the Supplementary Table S1. The results were ascertained using the certified reference material CRM048-050 (RTC). The recovery values ranged between 95% and 101%, with RDS ± 0.5%.

The bioavailable fractions of Zn and Cd were assessed using DGT soil samplers (DGT Research Ltd, Lancaster, UK) with 0.91 mm diffusive layer thickness (diffusive gel plus filter) and a chelex-100 (Sigma Aldrich, USA) binding layer. The optimal deployment time for the samplers in analysed soils was determined in an initial trial and corresponded to 288 h (i.e. 12 days) and 144 h (i.e. 6 days) for NM and M soils, respectively. 50 g of soil was weighed and placed in 100 ml containers. Milli-Q water was carefully added until the soil reached 100% WHC. Samples were left to equilibrate for 24 h before deployment of the DGT. The exposure window of the DGT was smeared with moist soil just before deployment to ensure good soil contact. Subsequently, the sampler was firmly pushed onto the surface of the soil. At retrieval, the devices were removed from the soil, any adhering soil rinsed with Milli-Q water, and the DGT devices were opened. The binding gel was removed with plastic tweezers and eluted in 1 ml of 1M HNO3. After a minimum of 24 h elution, 0.8 ml of the eluent was sampled, diluted six times and acidified before analysis with flame or graphite furnace AAS (Varian AA280FS, AA280Z, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). Two blanks per DGT batch were provided as a control.

The mass of an element (Me) accumulated in the binding gel was calculated using the following equation 1:

| (1) |

where C is the metal concentration in the elution solution measured by AAS (μg 1−1), Vacid is the volume of acid used for elution (1), Vgel is the volume of the binding gel (l), and fe is the elution factor (0.8 for Zn and Cd, Zhang et al., 1998). From Me, the time averaged element concentration at the interface of the DGT and the soil (cDGT, μg 1−1) was calculated by equation 2:

| (2) |

where Δg is the total thickness of the diffusive gel layer and filter membrane (cm), D is the diffusion coefficient of the particular element in the diffusive gel (cm2 s−1), A is the surface area of the DGT sampling window (cm2), and t is the deployment time (s) (Zhang et al. 2004). As the diffusion coefficient is temperature dependent, air temperature in the laboratory was monitored and averaged over the entire analysis time and the diffusion coefficients were adjusted accordingly.

2.3. Data analyses

Due to the small sample size and non-normal distributions for most parameters, nonparametric tests were applied. Firstly, the differences in the mean value of soil parameters between NM and M site types were tested via the Wilcoxon signed-ranked test. Next, to assess the association between total and bioavailable soil TME concentrations, we calculated Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and used linear regression models, each with the associated P-values. The latter analyses were performed for all samples, for NM and M soil types, and separately for each of the four locations (NM_PL14, NM_PL35, M_PL22, M_PL27). The differences in the chemical and physical soil parameters between the four locations were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Coefficients of variation (CV) were calculated as a measure of heterogeneity at the soil type and location levels.

The differences in plant parameters between the non-metallicolous and the metallicolous ecotypes (growing on NM or M soil type, respectively) and populations from individual locations (NM_PL14, NM_PL35, M_PL22, M_PL27) were tested in the same manner. Additionally, population-specific translocation (TF, shoot:root ratio) and bioaccumulation (BAF, shoot:soil ratio) factors were calculated to gain insight into the plants’ phytoremediation potential. BAF calculations were based on both, total (BAF_cT) and bioavailable (BAF_cDGT) soil TME fractions. The relationships between plant shoot elemental concentrations and either total or bioavailable soil TME concentrations were assessed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and the linear regression models. Lastly, we examined the Zn phytoextraction efficiencies for each population by comparing the amount of shoot DW necessary to accumulate 1 kg of Zn per population at its site. The differences in Zn phytoextraction efficiencies between populations were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. All analyses were performed using R 3.4.3 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Soil characteristics

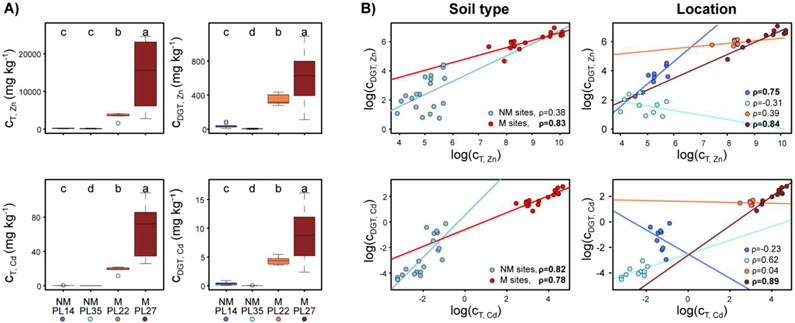

Non-metalliferous and M sites differed significantly in all examined soil physical and chemical parameters (Table S2). The most pronounced differences were observed in the total (cT) and bioavailable (cDGT) fractions of Zn and Cd. These parameters were between 23-fold (for cDGT,Zn) and 266-fold (for cT,Cd) higher in M soil than NM soil. On average, total and bioavailable soil Zn concentrations exceeded Cd concentrations in both soil types (Table S2). For the remaining parameters, differences between soil types were less pronounced and ranged between 0.2-fold (for the clay fraction) and 2.2-fold increases (for the sand fraction) from NM to M soil. Zinc and Cd concentrations (total and bioavailable) increased in the following order among sites: NM_PL35 < NM_PL14 < M_PL22 < M_PL27 (Figure 2). Differences between means were larger between M_PL22 and M_PL27 than between NM_PL14 and NM_PL35, and M sites exhibited a significantly larger range of values for both the total and bioavailable Zn and Cd fractions (Table S3).

Figure 2.

Total (cT) and bioavailable (cDGT) fractions of Zn and Cd in soil (A), together with relationships between log-transformed fractions at non-metalliferous (NM, blue) and metalliferous (M, red) sites (B). The box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data, the median is indicated by the horizontal line. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.05. ρ: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient; significant relationships are in bold.

The relationship between bioavailable and total fractions of Zn and Cd was positive and very strong (Spearman coefficient ρ > 0.8) for both elements in the M soil type and for Cd in the NM soil type (Figure 2). Whereas further correlation analyses on each of the M and NM locations separately revealed similarly strong patterns for locations M_PL27 (for Zn and Cd) and NM_PL14 (for Zn), no significant relationship was observed for the NM_PL35 or M_PL22 sites. Moreover, for Zn at NM_PL35 and for Cd at NM_PL14, the relationship between the bioavailable and the total fraction tended to be negative.

3.2. Variation in plant biomass and Zn & Cd concentrations in shoots and roots

Whereas plant shoot and root biomass did not vary at the ecotype level (Table S4), significant differences in shoot DW were observed among populations (Table S5). The highest values were found in NM_PL14 and M_PL27 populations, intermediate in NM_PL35, and the lowest biomass in the M_PL22 population. Populations did not differ regarding root biomass.

Zinc and Cd concentrations in shoots and roots differed between ecotypes, with significantly higher values in M plants compared to NM plants (Table S4). Both elements were predominately accumulated in the shoots, except in the NM_PL35 population, which exhibited matching elemental concentrations in both shoots and roots (Figure 3). Similarly, shoot and root Cd concentrations did not significantly differ for the M_PL22 population. Zinc shoot concentration in both M populations was above the hyperaccumulation threshold (3000 mg kg−1; van der Ent et al., 2013). Interestingly, in NM_PL14, plants’ Znshoot concentration did not differ from the two metallicolous populations, despite 10-100 times lower total Zn soil concentration at the NM_PL14 site (Figure 3). The NM_PL35 population was the only one that contained plants that did not meet the hyperaccumulation criteria. Specifically, 90% of plants from NM_PL35 accumulated Zn in shoots below 3000 mg kg−1 and only 50% of plants had ZnTF ≥ 1. Overall, mean Znshoot and Znroot concentrations in the studied populations decreased in the following order: M_PL27 > M_PL22 > NM_PL14 > NM_PL35. Regarding Cd concentration in shoots, all NM plants and several individuals in both M populations – 14% of M_PL22 plants and 20% of M_PL27 plants – did not reach the hyperaccumulation threshold for this element (100 mg kg−1; van der Ent et al. 2013). The CdTF ≥ 1 criterion was met by 60% of M_PL22 and NM_PL35 plants, 90% of M_PL27 plants, and 100% of NM_PL14 plants. Overall, CdTF was lower than ZnTF in all four populations (Table S5).

Figure 3.

Concentrations of Zn and Cd in shoots and roots (A), and translocation factors (TF) in non-metallicolous (NM, blue) and metallicolous (M, red) Arabidopsis halleri (B). The box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data, the median is indicated by the horizontal line. Dotted lines indicate the threshold for hyperaccumulation. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences at P ≤ 0.05.

3.3. Relationship between Zn and Cd soil concentrations and their accumulation in plant shoots

Overall, the Spearman correlation analyses between Zn accumulation in plant shoots and Zn concentration in the soil revealed stronger and more significant results for comparisons with bioavailable compared to total fractions of this element in the soil (Table 1). Regarding the bioavailable fraction of Zn, the analysis of the entire dataset yielded a weak (Spearman coefficient ρ = 0.35) but significant correlation. At the ecotype and location levels, strong and significant relationships (∣ρ∣ > 0.5) were found for analyses covering all NM samples and for location NM_PL35 (both positive), as well as for location M_PL27 (negative). For the total soil Zn, Spearman correlation coefficients were weak (∣ρ∣ < 0.4) and not significant, except at the M_PL27 location (ρ = −0.68). Cadmium accumulation in A. halleri shoots was positively correlated with both, total and bioavailable fractions of Cd in soil, but only for the analyses covering the entire dataset, all NM samples, and the M_PL27 location. A strongly negative relationship (ρ = −0.59) was found for bioavailable Cd at the M_PL22 location, yet this result was not significant. Correlation analysis on the M group revealed no significant relationship.

Table 1.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) of associations between Zn or Cd concentrations in Arabidopsis halleri shoots and in soil. Significant relationships are in bold. NM: non-metallicolous A. halleri populations; M: metallicolous A. halleri populations.

| Location | Zn in soil | Location | Cd in soil | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Bioavailable | Total | Bioavailable | |||||||

| Znshoot | All | 0.30 | 0.35 | Cdshoot | All | 0.71 | 0.75 | |||

| NM | 0.36 | 0.77 | NM | 0.59 | 0.56 | |||||

| NM_PL14 | 0.38 | 0.45 | NM_PL14 | −0.13 | 0.15 | |||||

| NM_PL35 | −0.35 | 0.64 | NM_PL35 | 0.48 | −0.03 | |||||

| M | −0.17 | −0.37 | M | 0.28 | 0.32 | |||||

| M_PL22 | 0.39 | 0.25 | M_PL22 | −0.09 | −0.59 | |||||

| M_PL27 | −0.68 | −0.77 | M_PL27 | 0.79 | 0.76 | |||||

Regarding Zn and Cd translocation from roots to shoots, the smallest values were found at the NM_PL35 location, where the bioavailable fractions of these elements were also lowest (Figure 3b). At the NM_PL14 location, TF of Zn and Cd were slightly higher (~2). Whereas CdTF increased with higher fractions of bioavailable Cd at the NM_PL14 site, ZnTF was independent of soil Zn bioavailability. The same independence was observed for both Zn and Cd at the M_PL27 site. Interestingly, when cDGT,Zn and cDGT,Cd exceeded 800 μg 1−1 and 10 μg 1−1, respectively, the values of the respective translocation factors appeared to decrease. Translocation of Zn and Cd in A. halleri might thus be limited above a certain soil contamination level. However, such potential threshold-type behavior will need to be confirmed in future studies with more repetitions. At the M_PL22 location, Zn and Cd translocation factors did not depend on the bioavailable fractions of Zn and Cd in soil.

Zinc and Cd bioaccumulation factors decreased non-linearly with increasing bioavailable TME concentrations in soil (Figure 4) and differed significantly between the two ecotypes, reaching higher values in the NM ecotype (Table S4). Hence, NM plants were more efficient in hyperaccumulating both elements per unit of the bioavailable or total concentration of given element at their respective locations.

Figure 4.

Relationships between concentrations of Zn and Cd in Arabidopsis halleri shoots and bioavailable fractions in soil at non-metalliferous (NM, blue) and metalliferous (M, red) sites. ρ: Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient; significant relationships are in bold.

3.4. Zn hyperaccumulation efficiency

Since the total amount of Zn removed from the soil by A. halleri plants was considerably higher than the Cd removal at all four sites, this section will focus on the efficiency of Zn hyperaccumulation. The average amount of Zn accumulated by a single, average size plant at each site increased in the following order: NM_PL35 (1.9 ± 1.1 mg Zn) < M_PL22 (3.2 ± 2.8 mg Zn) < NM_PL14 (12.3 ± 10.2 mg Zn) < M_PL27 (12.7 ± 18.9 mg Zn). Accordingly, an average NM_PL14 or M_PL27 plant accumulated 7-times and 4-times more Zn than an average NM_PL35 and M_PL22 plant, respectively. The similarity between the amount of Zn accumulated by an average NM_PL14 plant and an average M_PL27 plant was surprising, given the 2 orders of magnitude difference in soil Zn concentration between the two sites. Interestingly, the highest amount of Zn accumulated by a single plant at the NM_PL14 and M_PL27 sites was 32.7 mg and 61.5 mg, respectively, even though the biomass ratio for these specific plants was 2:1. In general, accumulation by M_PL27 plants tended to increase with increasing biomass. This was not the case for NM_PL14 individuals, for which phytoextraction efficiency did not depend on absolute biomass production. Accordingly, to obtain one kilogram of Zn from M_PL27, NM_PL14, M_PL22 and NM_PL35 locations, a total biomass of ~70, 100, 100, and 400 kg DW of A. halleri shoots, respectively, is required. This corresponds to ~ 79,000, 81,000, 320,000, and 530,000 A. halleri individuals, respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship between Zn and Cd concentrations in shoots and their bioavailable fractions in soil

In order to be taken up by the plant, elements have to be in soil solution or potentially exchangeable from the solid phase (Soriano-Disla et al., 2018). Bioavailable fractions of TME in the soil are thus expected to be good indicators of shoot TME concentrations. This assumption was supported by our study when jointly considering all samples and at the NM ecotype level, but not for samples from the M ecotype. The overall relation (for all samples) between the bioavailable fractions of Zn and Cd in the soil and concentrations of these elements in A. halleri shoots appeared to be strong for Zn and moderate for Cd. Importantly, the bioavailable fraction exhibited a stronger and more significant association with shoot elemental concentrations than total soil TME concentrations. Successful predictions of TME concentrations in plant shoots based on the relationship with DGT-derived estimates of bioavailable fractions of TME in soils have been frequently made for both Zn (Cornu & Denaix, 2006; Huynh et al., 2010; Muhammad et al., 2012; Nolan et al., 2005; Sonmez et al., 2009; Sonmez & Pierzynski, 2005; Sun et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2004) and Cd (Song et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2008). However, these studies focused on non-hyperaccumulating plants (e.g. lettuce, maize, rice, willow) and comparable investigations on hyperaccumulators are largely lacking. The few exceptions are studies on the Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola from metal-contaminated soils. Cadmium and Zn hyperaccumulation levels in S. plumbizincicola were not related to the bioavailable fraction of Cd (Wu et al., 2018) or Zn in contaminated soils (Li et al. 2014). This is in line with our results for A. halleri at metal-contaminated sites, where the concentrations of Zn and Cd in plants shoots and the bioavailable fractions of these elements in the soil were not related. Contrary, at NM sites, both metals in shoots correlated strongly with the corresponding bioavailable fractions in soil, and this link was particularly strong for Zn. Overall, these results show that the complexity of the plant-soil relationship at metal contaminated sites hampers accurate predictions of plant shoot concentrations based on metal bioavailability estimated using the DGT method. Moreover, our study suggests that the relationship between metal bioavailabity in soil and its uptake by hyperaccumulator plants should rather be estimated at the site level, instead of generating broader models across sites with extreme TME concentrations. This is epitomized by relationships with opposite signs that we obtained from the two M sites, which results in an overall weak and non-significant correlation at the M ecotype level (Figure 4; Table 1). We thus recommend any exploratory study to assess such relationships locally, i.e., before implementing plant-based remediation schemes.

Several factors could contribute to the lack of a relationship between the bioavailable TME fraction and TME shoot concentrations at M sites. Firstly, it could be due to methodological limitations (Wang et al., 2019). The bioavailable fraction is believed to most accurately predict TME shoot concentrations under conditions where root uptake is limited by diffusive transport of elements to the root surface (Degryse et al., 2009). Although this is rather unlikely under TME contaminated conditions, a slightly alkaline pH and very low clay content at M locations in our study could indeed be limiting factors. Secondly, TME uptake is differently controlled by different plants and can be enhanced by increasing the root exchange surface (Haines, 2002; Rees et al., 2016). While the lack of differences in root biomass in our study suggested that the populations did not vary in terms of total root surface, the weight of the excavated roots might not be a good predictor of root development and proliferation in species with delicate roots like A. halleri. Indeed, a recent study based on non-invasive measurements of root system length and architecture identified two different root development strategies in A. halleri: dampened root development in M and strong root proliferation in NM soils (Dietrich et al. 2019). As these strategies indicate a cost of tolerance and TME foraging, respectively, they likely control soil metal bioavailability in various ways.

For instance, TME bioavailability can be modified by root exudates (Chardot-Jacques et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2018; Puschenreiter et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2018) and/or the soil microbiome (Hou et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2019; Muehe et al., 2015). Plant-growth promoting bacteria can increase TME solubility (Sessitsch et al., 2013) and thus significantly affect not only TME hyperaccumulation levels in plants, but also TME tolerance. Further research is needed to explore the effects of plant-soil-microbial interactions on soil metal bioavailability and plant accumulation levels in A. halleri.

4.2. Population-specific patterns in TME accumulation and root to shoot translocation

We observed an extremely broad range of metal concentrations in A. halleri shoots, not only among NM and M ecotypes, but also between and within populations. All populations reached exceptionally high concentrations of Zn that greatly exceeded the typical nutritional amounts considered to be sufficient for normal plant growth and development (Brooks, 1998). This confirms the Zn hyperaccumulation phenomenon in A. halleri plants on both M and NM soils. Natural variation, the ability to achieve very high Zn concentration in above-ground tissues, and its constitutive origin are well documented in European populations of A. halleri (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2018; Bert et al., 2000, 2002; Corso et al., 2018; Schvartzman et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2017). In contrast, only 39% of plants accumulated Cd at concentrations that were above the threshold for Cd hyperaccumulation (i.e. >100 mg kg−1). Moreover, Cd hyperaccumulating plants were found mainly within the M ecotype. These results are congruent with the findings of previous studies on A. halleri and underline the population-specific character of this trait (Bert et al., 2002; Stein et al., 2017, Corso et al., 2018).

Plant exposure to elevated TME concentrations in soil often alters fundamental physiological processes, negatively affecting plant growth and resulting in distinct biomass production between populations from M and NM locations (Audet & Charest, 2008; Dechamps et al., 2007). Surprisingly, we found that A. halleri growing on the most contaminated M_PL27 site had on average a 7 times larger biomass compared to the population from the less contaminated M_PL22 location. Also, hyperaccumulation of either Zn or Cd were not linked to shoot biomass production, suggesting natural variation in internal TME tolerance between the populations. Further, Zn and Cd hyperaccumulation patterns did not reflect differences in soil TME concentrations. Particularly interesting was the negative relationship between Zn concentration in A. halleri shoots and Zn in soil at the M_PL27 site, where both concentrations –in plant tissues and in the soil – were exceptionally high. Furthermore, when Zn in soil exceeded a certain level, its bioaccumulation and translocation factors were considerably lower. This suggests that, despite the high internal demand for Zn in this species, plants growing at metalliferous sites carefully regulate its uptake, distribution and concentration in their tissues. Such well-controlled and plant-mediated accumulation and allocation of Zn, preventing excessive levels in plants tissues, was recently reported in a study investigating nutrient homeostasis in A. halleri seeds (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2020).

Whereas Cd hyperaccumulation did not differ between the two M sites, we observed markedly lower Cd root to shoot translocation at the less contaminated M_PL22 location than at the M_PL27 location, despite high Cd concentrations in the roots of M_PL22 plants. This supports recent work performed on two M A halleri populations – I16 from Italy and PL22 from Poland – which indicated that in M_PL22 Cd accumulation in shoots is mostly determined by root processes (Corso et al., 2018). Against the backdrop of decreased biomass production at the less polluted M_PL22 site in our study, this hints at different Cd accumulation strategies and varying costs of TME tolerance at M sites, especially because faster Cd translocation typically conveys Cd tolerance. Soil TME contamination may thus not be the deciding factor for differing levels of plant TME hyperaccumulation at M sites. Harsh environmental conditions at such highly diverse metal-polluted sites may result in varying grades of selection pressure and require specific local adaptation. Indeed, recent wholegenome re-sequencing of M_PL27, M_PL22, NM_PL14 and NM_PL35 population pools showed that local adaptation to high TME concentration in soil plays an important role in diversifying both ecotypes in southern Poland (Sailer et al., 2018). The importance of ongoing microevolutionary changes within populations at M sites in southern Poland was also shown for the pseudometallophytes Biscutella laevigata (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2014) and Viola tricolor (Słomka et al., 2011).

4.3. Extraordinary efficiency in Zn uptake at the lowland non-metallicolous site

Interestingly, hyperaccumulation of Zn by NM_PL14 plants did not differ from Zn hyperaccumulation in metallicolous populations, despite the significantly lower soil Zn concentrations. In fact, NM_PL14 exhibited a remarkable capacity to extract Zn from soil at a non-metalliferous site, not only in comparison with the NM_PL35 population, but also with other NM A. halleri populations at the European scale (Frérot et al., 2018; Stein et al., 2017). Possible explanations for the NM_PL14 plants’ extraordinarily efficient Zn uptake might be found in their evolutionary history. Although metal-related traits are commonly associated with edaphic origin, phylogeographic units may supersede this relationship (Gonneau et al., 2017). The populations investigated in our study belong to one – the Western Carpathian – phylogeographic unit (Šrámková et al., 2019; Wasowicz et al., 2016), suggesting that the intriguing variation in Zn accumulation between Polish A. halleri populations might be linked more to recent local adaptation processes than to the species’ migration history. Indeed, the NM_PL14 population might represent a recent colonization event from an M site, and its extreme Zn hyperaccumulation capacities may be associated with positive selective pressure towards higher Zn uptake capacities at NM sites (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2018). Our findings are further in line with a recent study on metal allocation to and within A. halleri seeds, where unexpectedly high Zn concentrations were reported in the seeds from the uncontaminated NM_PL14 location (Babst-Kostecka et al., 2020). The contrasting strategies of metal allocation to A. halleri vegetative and reproductive tissues at lowland non-metalliferous locations vs. metalliferous sites are worth exploring further to resolve quantitative variability and extraordinary efficiency in TME uptake by lowland NM accessions of A. halleri.

4.4. Future applications in sustainable phytoremediation technologies and beyond

In this study, we identified three A. halleri populations characterized by extremely high TME concentrations in shoots (NM_PL14, M_PL22 and M_PL27). These plants are not only ideally suited for future phytoremediation efforts, but could also constitute promising material in the emerging industrial applications of green chemistry. This way, TME-rich plant biomass could substitute some of the mined metals, and thus contribute to the reduction of traditional mining activities and their associated negative impact on the environment (Deyris & Grison, 2018). Several plant-derived metal-based ecocatalysts have already proven to be effective in a number of chemical reactions (Clavé et al., 2016; Iwanejko et al., 2018). Our study suggests that some A. halleri plants might be better suited for subsequent ecocatalysis than others. In particular, population M_PL27 offers the advantage of producing high biomass while maintaining high phytoextraction efficiencies. Not only does this increase the quality of the plant biomass for use in green chemistry, but it might also simplify harvesting. Hence, a screening for genotypes that produce high biomass could further increase the efficiency of their application. Highly productive individuals in terms of both biomass production and phytoextraction efficiency will reduce the amount of individuals required to aquire a target mass of Zn, thus minimizing cultivation efforts.

Overall, substantial differences at the ecotype and the population levels exist, indicating that both ecotypic differentiation and local site conditions may play an important role in shaping TME-hyperaccumulation traits. Common garden or transplant experiments will provide further insight in the effect of ecotype vs. local site conditions on the evolution of different TME accumulation strategies. Such studies, combined with our novel and broadly relevant findings, will strengthen the scientific basis and successful application of metal hyperaccumulating plants in phytoremediation and green chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

Zinc and Cd bioaccumulation factors (BAF) in non-metallicolous (NM, blue) and metallicolous (M, red) Arabidopsis halleri. The box represents the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data, the median is indicated by the horizontal line. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences at P≤0.05. Dotted lines represent the hyperaccumulation criterion of BAF ≥ 1. cT: total, cDGT: bioavailable fractions of Zn and Cd in soil. Please note the discontinuous scale of the x-axis.

Highlights:

Soil metal concentration is a poor predictor of metal accumulation in plant biomass

Non-metallicolous populations may be extraordinarily efficient metal accumulators

Metal bioaccumulation decreases non-linearly with increasing soil metal content

Depending on the population, 79’000 to 530’000 plants are needed to mine 1 kg of zinc

Plant material has to be optimized for a given site to maximize metal phytoextraction

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the POWROTY/REINTEGRATION programme of the Foundation for Polish Science co-financed by the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund (POIR.04.04.00-00-1D79/16-00), the National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program (SRP) Grant P42ES004940) at The University of Arizona, by the University of Arizona Technology and Research Initiative Fund (TRIF) Center for Environmentally Sustainable Mining, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Grants for Young Scientists and PhD Students 4604/E-37/M/2015, 4604/E-37/M/2016) and the statutory fund of the W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences. We thank G. Szarek-Łukaszewska for helpful input, N. Malinowska, M. Stanek, B. Pawłowska, E. Budziakowska-Kubik and A. Pitek for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali H, Khan E, Sajad MA. 2013. Phytoremediation of heavy metals - Concepts and applications. Chemosphere 91: 869–881. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audet P, Charest C. 2008. Allocation plasticity and plant-metal partitioning: Meta-analytical perspectives in phytoremediation. Environmental Pollution 156: 290–296. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst-Kostecka A, Schat H, Saumitou-Laprade P, Grodzińska K, Bourceaux A, Pauwels M, Frérot H. 2018. Evolutionary dynamics of quantitative variation in an adaptive trait at the regional scale: The case of zinc hyperaccumulation in Arabidopsis halleri. Molecular Ecology 27: 3257–3273. DOI: 10.1111/mec.14800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babst-Kostecka AA, Parisod C, Godé C, Vollenweider P, Pauwels M. 2014. Patterns of genetic divergence among populations of the pseudometallophyte Biscutella laevigata from southern Poland. Plant and Soil 383: 245–256. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-014-2171-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babst-Kostecka A, Przybyłowicz WJ, Seget B, Mesjasz-Przybyłowicz J. 2020. Zinc allocation to and within Arabidopsis halleri seeds: Different strategies of metal homeostasis in accessions under divergent selection pressure. Plant-Environment Interactions 1: 207–220. DOI: 10.1002/pei3.10032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert V, Bonnin I, Saumitou-Laprade P, De Laguérie P, Petit D. 2002. Do Arabidopsis halleri from nonmetallicolous populations accumulate zinc and cadmium more effectively than those from metallicolous populations? New Phytologist 155: 47–57. DOI: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00432.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bert V, Macnair MR, De Laguerie P, Saumitou-Laprade P, Petit D. 2000. Zinc tolerance and accumulation in metallicolous and nonmetallicolous populations of Arabidopsis halleri (Brassicaceae). New Phytologist 146: 225–233. DOI: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RR. 1998. Plants that hyperaccumulate metals: their role in phytoremediation, microbiology, archaeology, mineral exploration, and phytomining. CAB International: Oxford; New York [Google Scholar]

- Chaney RL, Angle JS, Broadhurst CL, Peters CA, Tappero R V., Sparks DL. 2007. Improved understanding of hyperaccumulation yields commercial phytoextraction and phytomining technologies. Journal of Environmental Quality 36: 1429–1433. DOI: 10.2134/jeq2006.0514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chardot-Jacques V, Calvaruso C, Simon B, Turpault MP, Echevarria G, Morel JL. 2013. Chrysotile dissolution in the rhizosphere of the nickel hyperaccumulator Leptoplax emarginata. Environmental Science and Technology 47: 2612–2620. DOI: 10.1021/es301229m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavé G, Garel C, Poullain C, Renard BL, Olszewski TK, Lange B, Shutcha M, Faucon MP, Grison C. 2016. Ullmann reaction through ecocatalysis: Insights from bioresource and synthetic potential. RSC Advances 6: 59550–59564. DOI: 10.1039/c6ra08664k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornu JY, Denaix L. 2006. Prediction of zinc and cadmium phytoavailability within a contaminated agricultural site using DGT. Environmental Chemistry 3: 61–64. DOI: 10.1071/EN05050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corso M, Schvartzman MS, Guzzo F, Souard F, Malkowski E, Hanikenne M, Verbruggen N. 2018. Contrasting cadmium resistance strategies in two metallicolous populations of Arabidopsis halleri. 4: 283–297. DOI: 10.1111/nph.14948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechamps C, Lefèbvre C, Noret N, Meerts P, Dechamps C. 2007. Reaction norms of life history traits in response to zinc in Thlaspi caerulescens from metalliferous and nonmetalliferous sites. New Phytologist 191–198. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01884.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degryse F, Smolders E, Zhang H, Davison W. 2009. Predicting availability of mineral elements to plants with the DGT technique: A review of experimental data and interpretation by modelling. Environmental Chemistry 6: 198–218. DOI: 10.1071/EN09010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deyris PA, Grison C. 2018. Nature, ecology and chemistry: An unusual combination for a new green catalysis, ecocatalysis. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 10: 6–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.cogsc.2018.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich CC, Bilnicki K, Korzeniak U, Briese C, Nagel KA, Babst-Kostecka A. 2019. Does slow and steady win the race? Root growth dynamics of Arabidopsis halleri ecotypes in soils with varying trace metal element contamination. Environmental and Experimental Botany 167: 103862. DOI: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2019.103862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frérot H, Hautekèete NC, Decombeix I, Bouchet MH, Créach A, Saumitou-Laprade P, Piquot Y, Pauwels M. 2018. Habitat heterogeneity in the pseudometallophyte Arabidopsis halleri and its structuring effect on natural variation of zinc and cadmium hyperaccumulation. Plant and Soil 423: 157–174. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-017-3509-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonneau C, Genevois N, Frérot H, Sirguey C, Sterckeman T. 2014. Variation of trace metal accumulation, major nutrient uptake and growth parameters and their correlations in 22 populations of Noccaea caerulescens. Plant and Soil 384: 271–287. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-014-2208-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonneau C, Noret N, Godé C, Frérot H, Sirguey C, Sterckeman T, Pauwels M. 2017. Demographic history of the trace metal hyperaccumulator Noccaea caerulescens (J. Presl and C. Presl) F. K. Mey. in Western Europe. Molecular Ecology 26: 904–922. DOI: 10.1111/mec.13942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines BJ. 2002. Zincophilic root foraging in Thlaspi caerulescens. New Phytologist 155: 363–372. DOI: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2002.00484.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikenne M, Nouet C. 2011. Metal hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance: A model for plant evolutionary genomics. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 14: 252–259. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honjo MN, Kudoh H. 2019. Arabidopsi halleri: A perennial model system for studying population differentiation and local adaptation. AoB Plants. DOI: 10.1093/aobpla/plz076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou D, Wang K, Liu T, Wang H, Lin Z, Qian J, Lu L, Tian S. 2017. Unique Rhizosphere Micro-characteristics Facilitate Phytoextraction of Multiple Metals in Soil by the Hyperaccumulating Plant Sedum alfredii. Environmental Science and Technology 51: 5675–5684. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.6b06531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh TT, Zhang H, Laidlaw WS, Singh B, Baker AJM. 2010. Plant-induced changes in the bioavailability of heavy metals in soil and biosolids assessed by DGT measurements. Journal of Soils and Sediments 10: 1131–1141. DOI: 10.1007/s11368-010-0228-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iwanejko J, Wojaczyńska E, Olszewski TK. 2018. Green chemistry and catalysis in Mannich reaction. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 10: 27–34. DOI: 10.1016/j.cogsc.2018.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabala C and Karczewska A. 2017. Metodyka analiz laboratoryjnych gleb i roślin (eng.: Methods of laboratory analyses of soil and plant samples), Wroclaw 2017, Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, http://www.up.wroc.pl/~kabala [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Khan S, Khan MA, Qamar Z, Waqas M. 2015. The uptake and bioaccumulation of heavy metals by food plants, their effects on plants nutrients, and associated health risk: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22: 13772–13799. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-015-4881-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Wu L, Hu P, Luo Y, Zhang H, Christie P. 2014. Repeated phytoextraction of four metal-contaminated soils using the cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. Environmental Pollution 189: 176–183. DOI: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YF, Aarts MGM. 2012. The molecular mechanism of zinc and cadmium stress response in plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 69: 3187–3206. DOI: 10.1007/s00018-012-1089-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Tao Q, Jupa R, Liu Y, Wu K, Song Y, Li J, Huang Y, Zou L, Liang Y, Li T. 2019. Role of Vertical Transmission of Shoot Endophytes in Root-Associated Microbiome Assembly and Heavy Metal Hyperaccumulation in Sedum alfredii. Environmental Science and Technology 53: 6954–6963. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.9b01093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Yin D, Cheng H, Davison W, Zhang H. 2018. Plant Induced Changes to Rhizosphere Characteristics Affecting Supply of Cd to Noccaea caerulescens and Ni to Thlaspi goesingense. Environmental Science and Technology 52: 5085–5093. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.7b04844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestri E, Marmiroli M, Visioli G, Marmiroli N. 2010. Metal tolerance and hyperaccumulation: Costs and trade-offs between traits and environment. Environmental and Experimental Botany 68: 1–13. DOI: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2009.10.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahar A, Wang P, Ali A, Awasthi MK, Lahori AH, Wang Q, Li R, Zhang Z. 2016. Challenges and opportunities in the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soils: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 126: 111–121. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehe EM, Weigold P, Adaktylou IJ, Planer-Friedrich B, Kraemer U, Kappler A, Behrens S. 2015. Rhizosphere microbial community composition affects cadmium and zinc uptake by the metal-hyperaccumulating plant Arabidopsis halleri. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 81: 2173–2181. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.03359-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad I, Puschenreiter M, Wenzel WW. 2012. Cadmium and Zn availability as affected by pH manipulation and its assessment by soil extraction, DGT and indicator plants. Science of the Total Environment 416: 490–500. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan AL, Zhang H, Mclaughlin MJ. 2005. Prediction of Zinc, Cadmium, Lead, and Copper Availability to Wheat in Contaminated Soils Using Chemical Speciation, Diffusive Gradients in Thin Films, Extraction, and Isotopic Dilution Techniques. Journal of Environmental Quality 34: 496–507. DOI: 10.2134/jeq2005.0496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhlinger R 1996. Maximum water-holding capacity. In: Schinner F, Öhlinger R, Kandeler E and Margesin R (eds) Methods in Soil Biology. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 385–386 [Google Scholar]

- Puschenreiter M, Schnepf A, Millán IM, Fitz WJ, Horak O, Klepp J, Schrefl T, Lombi E, Wenzel WW. 2005. Changes of Ni biogeochemistry in the rhizosphere of the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi goesingense. Plant and Soil 271: 205–218. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-004-2387-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rascio N, Navari-Izzo F. 2011. Heavy metal hyperaccumulating plants: How and why do they do it? And what makes them so interesting? Plant Science 180: 169–181. DOI: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees F, Sterckeman T, Morel JL. 2016. Root development of non-accumulating and hyperaccumulating plants in metal-contaminated soils amended with biochar. Chemosphere 142: 48–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sailer C, Babst-Kostecka A, Fischer MC, Zoller S, Widmer A, Vollenweider P, Gugerli F, Rellstab C. 2018. Transmembrane transport and stress response genes play an important role in adaptation of Arabidopsis halleri to metalliferous soils. Scientific Reports 8: 1–13. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-018-33938-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schvartzman MS, Corso M, Fataftah N, Scheepers M, Nouet C, Bosman B, Carnol M, Motte P, Verbruggen N, Hanikenne M. 2018. Adaptation to high zinc depends on distinct mechanisms in metallicolous populations of Arabidopsis halleri. New Phytologist 218: 269–282. DOI: 10.1111/nph.14949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessitsch A, Kuffner M, Kidd P, Vangronsveld J, Wenzel WW, Fallmann K, Puschenreiter M. 2013. The role of plant-associated bacteria in the mobilization and phytoextraction of trace elements in contaminated soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 60: 182–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Słomka A, Sutkowska A, Szczepaniak M, Malec P, Mitka J, Kuta E. 2011. Increased genetic diversity of Viola tricolor L. (Violaceae) in metal-polluted environments. Chemosphere 83: 435–442. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.12.081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N, Wang F, Zhang C, Tang S, Guo J, Ju X, Smith DL. 2013. Fungal Inoculation and Elevated CO2 Mediate Growth of Lolium Mutiforum and Phytolacca Americana, Metal Uptake, and Metal Bioavailability in Metal-Contaminated Soil: Evidence from DGT Measurement. International Journal of Phytoremediation 15: 268–282. DOI: 10.1080/15226514.2012.694500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonmez O, Kaya C, Aydemir S. 2009. Determination of zinc phytoavailability in soil by diffusive gradients in thin films. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 40: 3435–3451. DOI: 10.1080/00103620903326008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sonmez O, Pierzynski GM. 2005. Assessment of zinc phytoavailability by diffusive gradients in thin films. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 24: 934–941. DOI: 10.1897/04-350R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano-Disla JM, Calupiña-Moya RD, Martínez-Martínez S, Zornoza R, Faz Á, Acosta JA. 2018. Evaluation of the performance of chemical extractants to mobilise metals for remediation of contaminated samples. Journal of Geochemical Exploration 193: 22–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.gexplo.2018.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šrámková G, Kolář F, Záveská E, Lučanová M, Španiel S, Kolník M, Marhold K. 2019. Phylogeography and taxonomic reassessment of Arabidopsis halleri – a montane species from Central Europe. Plant Systematics and Evolution 305: 885–898. DOI: 10.1007/s00606-019-01625-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanowicz AM, Kapusta P, Zubek S, Stanek M, Woch MW. 2020. Soil organic matter prevails over heavy metal pollution and vegetation as a factor shaping soil microbial communities at historical Zn–Pb mining sites. Chemosphere 240:124922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein RJ, Höreth S, de Melo JRF, Syllwasschy L, Lee G, Garbin ML, Clemens S, Krämer U. 2017. Relationships between soil and leaf mineral composition are element-specific, environment-dependent and geographically structured in the emerging model Arabidopsis halleri. New Phytologist 213: 1274–1286. DOI: 10.1111/nph.14219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Chen J, Ding S, Yao Y, Chen Y. 2014. Comparison of diffusive gradients in thin film technique with traditional methods for evaluation of zinc bioavailability in soils. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 186: 6553–6564. DOI: 10.1007/s10661-014-3873-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandy S, Mundus S, Yngvesson J, de Bang TC, Lombi E, Schjoerring JK, Husted S. 2011. The use of DGT for prediction of plant available copper, zinc and phosphorus in agricultural soils. Plant and Soil 346: 167–180. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-011-0806-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thapa G, Sadhukhan A, Sahoo L. 2012. Molecular mechanistic model of plant heavy metal tolerance Molecular mechanistic model of plant heavy metal tolerance. Biometals 489–505. DOI: 10.1007/s10534-012-9541-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Wang X, Luo J, Yu H, Zhang H. 2008. Evaluation of holistic approaches to predicting the concentrations of metals in field-cultivated rice. Environmental Science and Technology 42: 7649–7654. DOI: 10.1021/es7027789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ent A, Baker AJM, Reeves RD, Chaney RL, Anderson CWN, Meech JA, Erskine PD, Simonnot MO, Vaughan J, Morel JL, Echevarria G, Fogliani B, Rongliang Q, Mulligan DR. 2015. Agromining: Farming for metals in the future? Environmental Science and Technology 49: 4773–4780. DOI: 10.1021/es506031u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ent A, Baker AJM, Reeves RD, Pollard AJ, Schat H. 2013. Hyperaccumulators of metal and metalloid trace elements: Facts and fiction. Plant and Soil 362: 319–334. DOI: 10.1007/s11104-012-1287-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen N, Hermans C, Schat H. 2009. Molecular mechanisms of metal hyperaccumulation in plants. New Phytologist 181: 759–776. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Zou Y, Luo J, Jones KC, Zhang H. 2019. Investigating Potential Limitations of Current Diffusive Gradients in Thin Films (DGT) Samplers for Measuring Organic Chemicals. Analytical Chemistry 91: 12835–12843. DOI: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasowicz P, Pauwels M, Pasierbinski A, Przedpelska-Wasowicz EM, Babst-Kostecka AA, Saumitou-Laprade P, Rostanski A. 2016. Phylogeography of arabidopsis halleri (Brassicaceae) in mountain regions of Central Europe inferred from cpDNA variation and ecological niche modelling. PeerJ 2016: 1–29. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.1645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Zhou J, Zhou T, Li Z, Jiang J, Zhu D, Hou J, Wang Z, Luo Y, Christie P. 2018. Estimating cadmium availability to the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola in a wide range of soil types using a piecewise function. Science of the Total Environment 637–638: 1342–1350. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Davison W, Knight B, Mcgrath S. 1998. In situ measurements of solution concentrations and fluxes of trace metals in sells using DGT. Environmental Science and Technology 32: 704–710. DOI: 10.1021/es9704388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Lombi E, Smolders E, McGrath S. 2004. Kinetics of Zn release in soils and prediction of Zn concentration in plants using diffusive gradients in thin films. Environmental Science and Technology 38: 3608–3613. DOI: 10.1021/es0352597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhao FJ, Sun B, Davison W, Mcgrath SP. 2001. A new method to measure effective soil solution concentration predicts copper availability to plants. Environmental Science and Technology 35: 2602–2607. DOI: 10.1021/es000268q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheljazkov VD & Nielsen NE 1996. Effect of heavy metals on peppermint and cornmint. Plant and Soil 178, 59–66 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.