This paper describes the revision of the thyroid dosimetry system in Ukraine using new, recently available data on (i) revised 131I thyroid activities derived from direct thyroid measurements done in May and June 1986 in 146,425 individuals; (ii) revised estimates of 131I ground deposition density in each Ukrainian settlement; and (iii) estimates of age- and gender-specific thyroid masses for the Ukrainian population. The revised dosimetry system estimates the thyroid doses for the residents of the settlements divided into three levels depending on availability of measurements of 131I thyroid activity among their residents. Thyroid doses due to 131I intake were estimated in this study for different age and gender groups of residents of 30,353 settlements in 24 oblasts of Ukraine, Autonomous Republic Krym, and cities of Kyiv and Sevastopol. Among them, dose estimates for 835 settlements were based on 131I thyroid activities measured in more than ten residents (the first level), for 690 settlements based on such measurements done in neighboring settlements (the second level), and for 28,828 settlements based on a purely empirical relationship between the thyroid doses due to 131I intake and the cumulative 131I ground deposition densities in settlements (the third level). The arithmetic mean of the thyroid doses due to 131I intake among 146,425 measured individuals was 0.23 Gy (median of 0.094 Gy); about 99.8% of them received doses less than 5 Gy. The highest oblast-average population-weighted thyroid doses were estimated for residents of Chernihiv (0.15 Gy for arithmetic mean and 0.060 Gy for geometric mean), Kyiv (0.13 and 0.051 Gy) and Zhytomyr (0.12 and 0.049 Gy) Oblasts followed by Rivne (0.10 and 0.039 Gy) and Cherkasy (0.088 and 0.032 Gy) Oblasts, and Kyiv City (0.076 and 0.031 Gy). The geometric mean of thyroid doses estimated in this study for entire Ukraine essentially did not change in comparison with a previous estimate, 0.020 vs. 0.021 Gy, respectively. The ratio of geometric mean of oblast-specific thyroid doses estimated in the present study to previously calculated doses varied from 0.51 to 3.9. The highest increase in thyroid doses was found in areas remote from the Chornobyl nuclear power plant with a low level of radioactive contamination: by 3.9 times for Zakarpatska Oblast, 3.5 times for Luhansk Oblasts and 2.9 times for Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast. The developed thyroid dosimetry system is being used to revise the thyroid doses due to 131I intake for the individuals of post-Chornobyl radiation epidemiological studies: the Ukrainian-American cohort of individuals exposed during childhood and adolescence, the Ukrainian in utero cohort, and the Chornobyl Tissue Bank.

Introduction

Following the accident at the Chornobyl (Chernobyl) nuclear power plant (NPP) that occurred on 26 April 1986, a large amount of radioactive material was released into the atmosphere, including 1.8×l018 Bq of the most radiologically important radionuclide, Iodine-131 (131I) (UNSCEAR 2011). This resulted in a significant exposure to the thyroid gland among residents of Ukraine, Belarus, and the Russian Federation, countries that were the most affected by the accident (Bouville et al. 2007). Significant efforts had been made to estimate the radiation doses to the thyroid gland due to 131I intake, specifically in Ukraine (e.g., Goulko et al. 1996, 1998; Likhtarev et al. 1993, 1994, 2003, 2006; Likhtarov et al. 2005, 2011, 2013a, 2014).

A recent study (Masiuk et al. 2021) recognized the limitations in the previous 131I thyroid dosimetry system including an improper geometry of direct thyroid measurements done in Ukraine to estimate 131I thyroid activity and unknown true values of calibration coefficients for some measuring devices used at that time. As a result of updated measurement geometry and calibration coefficients for measuring devices, revised values of 131I thyroid activity were obtained for 146,425 individuals measured in Ukraine. These new data on the 131I thyroid activity in residents as well as recently updated 131I ground deposition density in the settlements (Talerko et al. 2020) resulted in the revision of the entire thyroid dosimetry and the creation of an improved ‘Thyroid Dosimetry Ukraine 2020 system’ (named TDU20 here and below) for the entire population of Ukraine. The present paper describes TDU20 and the results of updating thyroid dose estimates due to 131I intake for the Ukrainian population.

Material and Methods

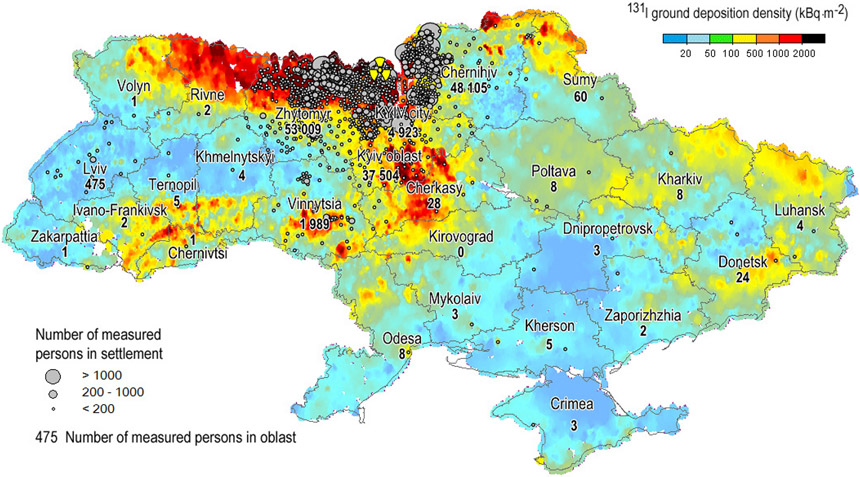

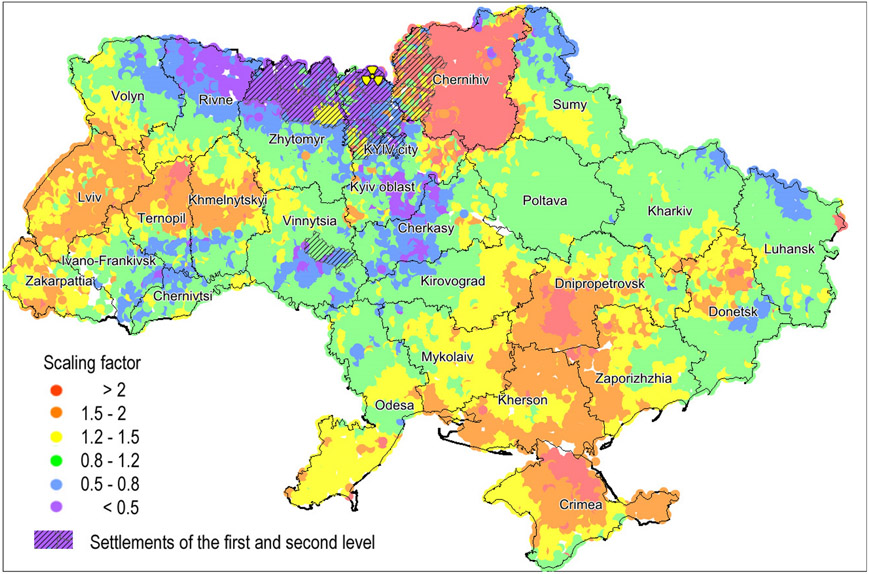

Thyroid dosimetry monitoring was conducted in May and June 1986 in Ukraine mainly in the northern regions (oblasts) which were most radioactively contaminated after the Chornobyl accident. Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the settlements and numbers of direct thyroid measurements done in Ukraine after the Chornobyl accident, as well as the 131I ground deposition density in the Ukrainian settlements (Talerko et al. 2020). Because only 146,425 individuals were measured and since most of the Ukrainian population was not measured for 131I thyroid activity, it was necessary to develop a dedicated system for reconstruction of thyroid doses in Ukraine that allowed estimation of individual doses for the whole population (Likhtarov et al. 2005, 2013a). Specifically, this system should allow to estimate the thyroid doses due to 131I intake for the residents of both, high and low contaminated areas in Ukraine with different degrees of individualization and reliability of doses. The thyroid dosimetry system, which was developed for residents of the Ukrainian settlements, TDU20, includes three levels:

Fig. 1.

Spatial distribution of the settlements and numbers of direct thyroid measurements done in Ukraine after the Chornobyl accident, and cumulative 131I ground deposition density (Talerko et al. 2020).

The first level includes 835 settlements of Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kyiv and Chernihiv Oblasts where measurements of 131I thyroid activity were performed in May and June 1986 among at least 10 residents in each settlement.

The second level includes 690 settlements where thyroid measurements were not performed or the number of measured individuals was less than 10, but such measurements were performed in at least five other settlements in a given raion (which is an administrative sub-region of an oblast).

The third level includes 28,828 settlements located in those raions where thyroid measurements were not performed, or the number of measurements was insufficient. In other words, this level includes settlements that were not included in the first and second level.

Obviously, the most reliable thyroid doses were estimated for residents of settlements included in the first TDU20 level that were covered by thyroid dosimetry monitoring. Table 1 gives the distribution of the number of settlements and individuals with thyroid measurements included in the first and second TDU20 level by oblast of residence at the time of the accident (ATA). It should be noted that the present paper uses the administrative-territorial structure of Ukraine as of 1 January 1987 according to (Kirnenko and Standyuk 1987).

Table 1.

Distribution of settlements and number of measured individuals included in the first and second levels of the dosimetry system TDU20 in Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kyiv and Chernihiv Oblasts in Ukraine.

| Raion | Number of settlements included

in TDU20 |

Number of

measured individuals, first level of TDU20 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First level | Second level | Total | ||

| Vinnytsia Oblast | ||||

| – Gaisyn | 4 | 60 | 64 | 634 |

| – Nemyriv | 9 | 84 | 93 | 910 |

| – Other raions | 1 | – | 1 | 380 |

| Zhytomir Oblast | ||||

| – Korosten | 57 | 55 | 112 | 4,180 |

| – Luhyny | 6 | 43 | 49 | 239 |

| – Malyn | 2 | 104 | 106 | 130 |

| – Narodychi | 72 | 12 | 84 | 20,005 |

| – Ovruch | 125 | 32 | 157 | 22,175 |

| – Olevsk | 14 | 47 | 61 | 908 |

| – Zhytomir City | 1 | – | 1 | 281 |

| – Korosten town | 1 | – | 1 | 4,491 |

| – Novograd-Volynsky town | 1 | – | 1 | 254 |

| – Other raions | 3 | – | 3 | 176 |

| Kyiv Oblast | ||||

| – Borodianka | 30 | 17 | 47 | 5,189 |

| – Vyshhorod | 42 | 17 | 59 | 6,919 |

| – Ivankiv | 51 | 22 | 73 | 3,997 |

| – Kyievo-Sviatoshyn | 4 | 47 | 51 | 77 |

| – Makariv | 43 | 25 | 68 | 4,293 |

| – Poliske | 48 | 13 | 61 | 4,379 |

| – Chornobyl | 44 | 19 | 63 | 5,162 |

| – Irpin town | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2,558 |

| – Prypiat town | 2 | – | 2 | 4,666 |

| – Other raions | 2 | – | 2 | 40 |

| Chernihiv Oblast | ||||

| – Kozelets | 94 | 17 | 111 | 13,734 |

| – Ripky | 84 | 36 | 120 | 11,783 |

| – Chernihiv | 89 | 39 | 128 | 13,984 |

| – Chernihiv City | 1 | – | 1 | 8,522 |

| – Other raions | – | – | – | – |

| Kyiv City | 1 | – | 1 | 4,923 |

| Total | 835 | 690 | 1,525 | 144,989 |

Calculation of individual thyroid doses

Thyroid doses resulted from the intake of 131I with inhaled air and/or foodstuffs, mainly milk, milk products and leafy vegetables contaminated with 131I. Ecological and biokinetic models were used to evaluate the transport of 131I from deposition on the ground surface via grass and dairy animals (cow and goat) into milk, and then into the human body and into the thyroid gland.

The individual instrumental thyroid dose, (Gy), for the k-th individual with direct thyroid measurement was calculated using Eq. 1:

| (1) |

where is the individual ecological thyroid dose calculated using an ecological model (Gy), and is the individual scaling factor that adjusts the ecological dose using the measured 131I thyroid activity (unitless).

The ecological thyroid dose was calculated using ecological and biokinetic models (Eq. 2) (Likhtarov et al. 2014):

| (2) |

where ku = 1.384 · 10−2 is a unit conversion factor (Bq kBq−1 g kg−1 J MeV−1 s d−1); is the energy absorbed in the thyroid gland per 131I disintegration (MeV); Mk is the age- and gender-specific thyroid mass for the k-th individual (g); (t) describes the variation of the 131I thyroid activity for the k-th individual as a function of time calculated using an ecological model (kBq); t is the time after the Chornobyl accident (d); T=66 (d) is a limit of integration that corresponds to 30 June 1986.

The individual scaling factor was calculated as:

| (3) |

where is the activity of 131I measured in the thyroid of the k-th individual (kBq); (tmes) is the activity of 131I in the thyroid at the time of measurement, t = tmes, calculated using an ecological model (kBq).

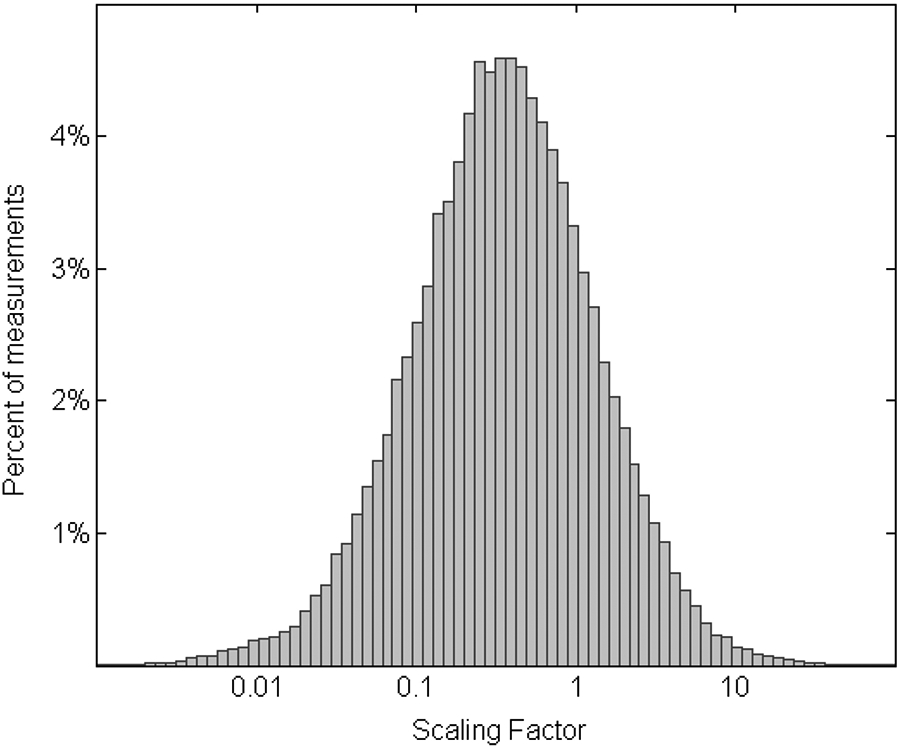

Figure 2 shows the distribution of scaling factors (logarithmic values) related to the thyroid doses calculated for 146,425 individuals in Ukraine with measured thyroid doses. Most of these individuals, 144,989 out of 146,425, were included in the first TDU20 level (Table 1). The remaining 1,436 measured individuals resided in the settlements of the second level of TDU20 where less than ten persons were measured.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of individual scaling factors, , related to the thyroid doses due to 131I intake calculated in this study for the 146,425 individuals with direct thyroid measurements (logarithmic scale of x-axis).

First TDU20 level

For the purpose of this study, the so-called ‘ecological’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland was introduced and defined from Eq. (2) as:

| (4) |

where is the ‘ecological’ energy (mJ) absorbed in the thyroid gland of the k-th individual of age a and gender s who resided in settlement j for the entire period of exposure to 131I, which was calculated using the ecological model.

By analogy with Eq. (4), the so-called ‘instrumental’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, , was defined as:

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

Because the 131I thyroid activity and, consequently, the total energy absorbed in the thyroid gland due to 131I decay is determined, in general, by age and gender-specific parameters such as breathing rate, diet, and mass of the thyroid gland, it was assumed that is similar among persons of the same age and gender who lived in the same settlement in similar radioecological conditions, at least some time after the accident. Therefore, the assessment of the function describing the age- and gender-specific energy absorbed in the thyroid gland was the main effort in the development of the thyroid dosimetry system for the residents of Ukraine (Likhtarov et al. 2005, 2013a). For an individual of age a and gender s living in the j-th settlement, where a sufficient number of direct thyroid measurements were done, the relative individual energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, fka,s,j, was calculated as:

| (7) |

where is the average energy absorbed in the thyroid gland of all measured persons of age a and gender s living in the j-th settlement (mJ); is the ‘reference’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland (mJ) that was defined as:

| (8) |

where Nj is the number of the residents of the j-th settlement belonging to the ‘reference’ group.

To calculate the reference energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, the population group of age aref=12, 13, 14 years was used as a ‘reference’ because it was the largest group of people with measured 131I thyroid activity (Table 2). This age group is referred to here and below as the ‘reference’ group, aref. Individual estimates of fka,s,j-values were aggregated within urban and rural types of settlements to obtain a single value of the relative energy absorbed in the thyroid gland for age and gender population subgroups, fU,a,s, in the following way:

| (9) |

where NU,a,s is the number of measured individuals of age a and gender s living in settlements of type U (urban or rural).

Table 2.

Distribution of number of measured individuals and mean scaling factor by age at the time of the accident (ATA) and gender among 146,425 individuals measured for 131I thyroid activity in Ukraine.

| Age ATA (y) |

Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N measured |

Scaling factor |

N measured |

Scaling factor |

N measured |

Scaling factor |

|

| 0 | 709 | 1.7 | 559 | 1.8 | 1,268 | 1.8 |

| 1 | 2,360 | 1.1 | 1,761 | 1.3 | 4,121 | 1.2 |

| 2 | 2,622 | 1.2 | 1,994 | 1.2 | 4,616 | 1.2 |

| 3 | 2,847 | 1.0 | 2,276 | 1.1 | 5,123 | 1.1 |

| 4 | 2,667 | 1.1 | 2,061 | 1.1 | 4,728 | 1.1 |

| 5 | 2,702 | 0.98 | 1,936 | 1.06 | 4,638 | 1.0 |

| 6 | 2,992 | 0.90 | 2,210 | 1.13 | 5,202 | 1.0 |

| 7 | 3,148 | 0.90 | 2,428 | 0.99 | 5,576 | 0.94 |

| 8 | 4,255 | 0.80 | 3,428 | 0.80 | 7,683 | 0.80 |

| 9 | 4,594 | 0.72 | 3,582 | 0.77 | 8,176 | 0.74 |

| 10 | 4,987 | 0.63 | 3,838 | 0.86 | 8,825 | 0.73 |

| 11 | 5,080 | 0.65 | 4,159 | 0.85 | 9,239 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 5,071 | 0.77 | 4,307 | 0.97 | 9,378 | 0.86 |

| 13 | 5,485 | 0.86 | 4,207 | 0.95 | 9,692 | 0.90 |

| 14 | 5,625 | 0.91 | 4,231 | 1.1 | 9,856 | 0.98 |

| 15 | 3,813 | 0.95 | 3,043 | 0.95 | 6,856 | 0.95 |

| 16 | 2,131 | 0.86 | 1,795 | 0.90 | 3,926 | 0.88 |

| 17 | 1,575 | 0.74 | 1,314 | 0.88 | 2,889 | 0.80 |

| ≥18 | 15,050 | 0.63 | 19,583 | 0.58 | 34,633 | 0.60 |

| All ages | 77,713 | 0.82 | 68,712 | 0.86 | 146,425 | 0.84 |

Table 3 provides the parameters of the distribution of the relative energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, fU,a,s, obtained in this study for 38 age and gender groups of the rural and urban populations of Ukraine.

Table 3.

Parameters of the distribution of the relative energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, fU,a,s, for 38 age and gender groups of the rural and urban population of Ukraine. AM – arithmetic mean; SD – standard deviation; GM – geometric mean; GSD – geometric standard deviation.

| Age | Urban |

Rural |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM | SD | GM | GSD | AM | SD | GM | GSD | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | |

| < 1 | 0.89 | 2.0 | 0.35 | 3.8 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 3.1 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 0.45 | 3.5 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 3.1 | ||||||||

| 2 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 0.48 | 3.3 | 0.62 | 0.86 | 0.36 | 2.9 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.88 | 1.3 | 0.50 | 2.9 | 0.60 | 1.09 | 0.35 | 2.9 | ||||||||

| 4 | 0.98 | 1.4 | 0.57 | 2.9 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.40 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| 5 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.62 | 2.7 | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 0.98 | 1.1 | 0.63 | 2.7 | 0.67 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 2.6 | ||||||||

| 7 | 0.97 | 1.2 | 0.62 | 2.6 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.47 | 2.5 | ||||||||

| 8 | 0.90 | 1.3 | 0.59 | 2.6 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.51 | 2.4 | ||||||||

| 9 | 0.85 | 1.0 | 0.60 | 2.4 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.55 | 2.4 | ||||||||

| 10 | 0.77 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 1.3 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 0.53 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 11 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.57 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| 12 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.63 | 0.60 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.65 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| 13 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 0.95 | 1.1 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| 14 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| 15 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| 16 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.83 | 0.73 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| 17 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 2.4 | 2.3 |

| ≥18 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0.97 | 0.88 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

The reference energy, , can be estimated from the results of the measurements performed in the j-th settlement among individuals of all ages using the parameters of the function fU,a,s, that, in general, did not require the availability of direct thyroid measurements done among individuals of reference age:

| (10) |

where Nj is the number of individuals in the j-th settlement.

The average energy absorbed in the thyroid gland can be determined using the fU,a,s -values estimated for individuals included in the age and gender groups “a, s” living in the j-th settlement from the first level of the dosimetry system, , as:

| (11) |

The average thyroid dose for age and gender group “a, s” for the j-th settlement of the first level of dosimetry system was calculated as:

| (12) |

where Ma,s is the mass of the thyroid gland for an individual of age and gender group “a, s” (g) given by Likhtarov et al. (2013b).

The approached described above was used to estimate the thyroid doses for residents of the settlements in Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Kyiv, and Chernihiv Oblasts, where at least ten individuals were measured for 131I thyroid activity in May and June 1986 (Table 1).

Second and third TDU20 levels

The number of individuals with measurements of the 131I thyroid activity in settlements of the second and third TDU20 level was not enough to apply the dose reconstruction method described in the previous section. Therefore, a specific dose reconstruction model was proposed for the residents of these settlements: the energy absorbed in the thyroid gland of the members of the age and gender group “a, s” resided in the j-th settlement was calculated as the product of the average energy absorbed in the thyroid gland of the ‘reference’ age group in this settlement, aref, the scaling factor, and the relative energy fU,a,s as:

| (13) |

| (14) |

where is the average ‘ecological’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland of the reference age group in the j-th settlement of the age group, aref (mJ); and are the average scaling factors for the j-th settlement belonging to the second or third TDU20 level, respectively (unitless).

The value of was defined as the ‘ecological’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland averaged over the reference age group in this settlement, aref = 12,13,14 and genders, s = 1, 2, as:

| (15) |

where is the ‘ecological’ energy absorbed in the thyroid gland of members of the reference age and gender groups “a, s” resided in the j-th settlement, calculated using the ecological model (see Eq. (4)) (mJ). The average values of the consumption of milk, milk products and leafy vegetables for the age and gender groups were derived from data obtained during the personal interviews of the Ukrainian-American cohort members (Likhtarov et al. 2014).

The raion-specific scaling factor for the settlements of the second group, , was calculated by averaging the estimated scaling factors for the settlements of the first TDU20 level in this raion:

| (16) |

| (17) |

where is the scaling factor for the j-th settlement of first TDU20 level in the R-th raion; NR is the number of settlements of first TDU20 level in the raion; was calculated using Eq. (10) only for those settlement where at least five measurements of 131I thyroid activity was done in May and June 1986.

The -values for settlements belonging to the second TDU20 level were calculated only for those raions where measurements of the 131I thyroid activity were done in at least five settlements, i.e., NR ≥ 5. Table 4 provides the parameters of the distribution of raion-specific scaling factors for settlements belonging to the second TDU20 level of the thyroid dose reconstruction system. Table 1 shows the distribution by raions of the number of settlements included in the second TDU20 level.

Table 4.

Parameters of the distribution of raion-specific scaling factors for the settlements belonging to the second TDU20 level, .

| Raion | Scaling factor |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Arithmetic mean | Geometric mean | GSD R | |

| Vinnytsia Oblast | |||

| – Gaisyn | 0.57 | 0.36 | 2.6 |

| – Nemyriv | 0.85 | 0.41 | 3.4 |

| Zhytomyr Oblast | |||

| – Korosten | 0.37 | 0.20 | 3.0 |

| – Luhyny | 0.42 | 0.25 | 2.8 |

| – Malyn | 1.2 | 0.62 | 3.2 |

| – Narodychi | 0.51 | 0.26 | 3.1 |

| – Ovruch | 0.41 | 0.24 | 2.8 |

| – Olevsk | 0.28 | 0.16 | 2.8 |

| Kyiv Oblast | |||

| – Borodianka | 0.46 | 0.27 | 2.8 |

| – Vyshhorod | 0.55 | 0.37 | 2.5 |

| – Ivankiv | 0.47 | 0.27 | 2.9 |

| – Kyievo-Sviatoshyn | 0.61 | 0.39 | 2.6 |

| – Makariv | 1.2 | 0.77 | 2.6 |

| – Poliske | 0.94 | 0.36 | 4.0 |

| – Poliske a | 1.3 | 0.24 | 6.3 |

| – Chornobyl | 0.45 | 0.21 | 3.4 |

| – Chornobyl a | 0.43 | 0.10 | 5.6 |

| Chernihiv Oblast | |||

| – Kozelets | 1.4 | 0.96 | 2.4 |

| – Ripky | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.9 |

| – Chernihiv | 3.7 | 1.8 | 3.3 |

Evacuated settlements.

Because the distribution of scaling factor-values was close to lognormal (Fig. 2), the logarithms of the scaling factor-values were assumed to be normally distributed. The logarithm of the scaling factor, , for the settlements belonging to the third TDU20 level was approximated by a linear function of the logarithm of cumulative 131I ground deposition densities, σ1–131, given in (kBq·m−2):

| (18) |

where a and b are fit parameters estimated using the least squares method (unitless).

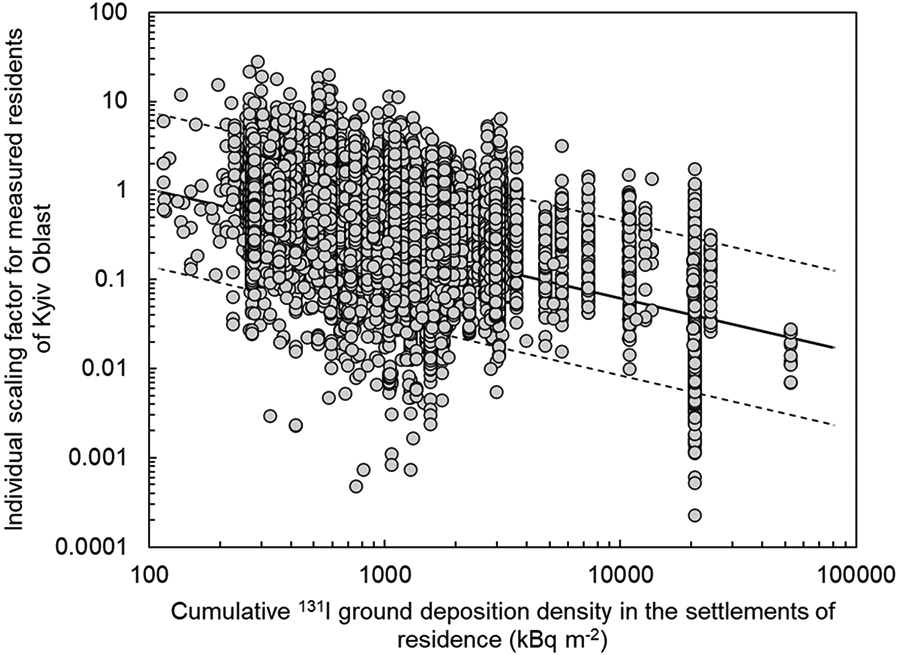

Figure 3 shows, as example, the correlation between the individual scaling factors for residents of Kyiv Oblast and the cumulative 131I ground deposition density in the settlements of their residence. In Fig. 3, the solid line represents the regression described by Eq. (18); Pearson correlation coefficient was rp=−0.54 (p<0.001) for logarithmic values.

Fig. 3.

Correlation between individual scaling factors, , for measured residents of Kyiv Oblast, and cumulative 131I ground deposition density in the settlements of their residence, . Solid line represents the regression described by Eq. (18); dashed lines represent 95% prediction bands.

Having in mind the lognormal distribution of the scaling factor values, their expected values were estimated using the following formula:

| (19) |

where is the scaling factor for the j-th settlement belonging to the third TDU20 level (unitless); GSDσ is the geometric standard deviation (GSD) of the scaling factor distribution; is the cumulative 131I ground deposition density in the j-th settlement (kBq·m−2);

Table 5 provides the parameters a, b and GSDσ for calculation of -values for the settlements in different oblasts in Ukraine included in the third TDU20 level. By analogy with Eq. (12), the thyroid dose for individuals from age and gender groups “a, s” who resided in the j-th settlement belong to the second, , and third,, levels was calculated using Eqs. (20) and (21), respectively:

| (20) |

| (21) |

Table 5.

Parameters a, b and GSDσ for calculation of the -values (see Eq. (19)) for the settlements included in the third TDU20 level, and correlation coefficient, rp, between the individual scaling factor and the cumulative 131I ground deposition density in the settlement of residence.

| Oblast | a | b | GSD σ | r p a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhytomyr and Vinnytsia | 0.70 | −0.29 | 3.0 | −0.23 |

| Kyiv | 2.85 | −0.61 | 2.7 | −0.54 |

| Chernihiv | 3.28 | −0.59 | 2.8 | −0.31 |

| Others regions of Ukraine | 1.18 | −0.36 | 2.9 | −0.30 |

Pearson correlation coefficient for logarithmic values, p<0.001 for all rp.

Errors in dose estimates

Since all factors on the right-hand side of Eqs. (12), (20) and (21) were positive and their distributions were right-asymmetric, it was assumed that the quantities of , , , , Ma,s and fU,a,s, have a distribution close to lognormal. Therefore, the distribution of thyroid doses was also expected to be close to lognormal and, consequently, the GSD was used to characterize dose errors. The logarithm of Eq. (12) is:

| (22) |

and the GSD of thyroid doses was defined by the following equation:

| (23) |

where , is the thyroid dose among individuals of the age and gender group “a, s” who resided in the j-th settlement of the first TDU20 level (Gy); is the geometric standard deviation for the thyroid dose of individuals of the age and gender group “a, s” who resided in the j-th settlement; GSDE is the geometric standard deviation of the reference energy absorbed in the thyroid gland, (unitless); GSDf is the geometric standard deviation of the fU,a,s function (Table 3) (unitless); GSDM is the geometric standard deviation of the thyroid mass, Ma,s, given by Table 8 in (Likhtarov et al. 2013b) (unitless).

By analogy with Eq. (23), the GSD of thyroid doses for residents of the settlements from the second and third TDU20 levels were calculated as:

| (24) |

| (25) |

where GSDR and GSDσ are the geometric standard deviations of the scaling factors and (Tables 4 and 5), respectively.

Results

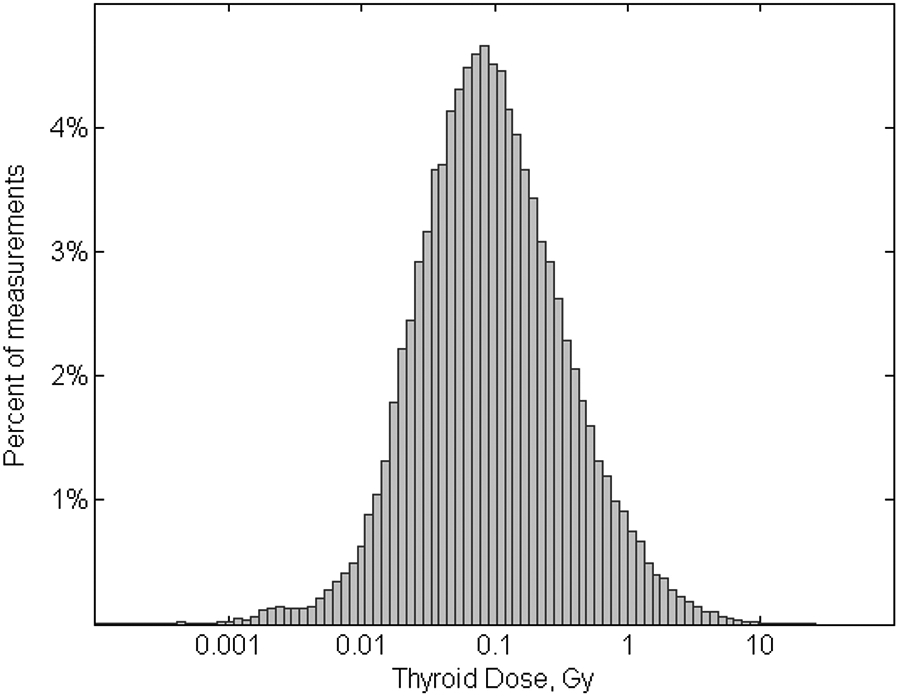

Table 6 gives the distribution of individual instrumental thyroid doses due to 131I intake, , among 146,425 individuals measured in Ukraine for the 131I thyroid activity. For the vast majority (about 99.8%) of individuals, the thyroid doses were less than 5 Gy. The arithmetic mean of instrumental thyroid doses for 146,425 measured individuals was 0.23 Gy (median of 0.094 Gy). Thyroid dose estimates varied in a wide range from 0.02 mGy up to 26 Gy while the 5%–95% dose interval was 0.013–0.86 Gy. Figure 4 shows the distribution of the individual instrumental thyroid doses for 146,425 individuals with measured 131I thyroid activity. The figure demonstrates that the distribution was close to lognormal with a GSD of 3.6. There was a deviation from the lognormal shape in the low-dose range (<0.01 Gy), which was associated with the censoring of the measured 13I thyroid activity below the minimal detectable activity of thyroid detectors (Masiuk et al. 2021).

Table 6.

Distribution of individual instrumental thyroid doses due to 131I intake, , among 146,425 individuals measured for 131I thyroid activity in Ukraine.

| Dose interval, Gy | Number of individuals |

% | Average thyroid dose, Gy |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.02 | 14,179 | 9.7 | 0.012 |

| 0.02 – 0.05 | 31,257 | 21.4 | 0.034 |

| 0.05 – 0.1 | 32,918 | 22.5 | 0.072 |

| (0.1 – 0.2 | 29,342 | 20.0 | 0.14 |

| 0.2 – 0.5 | 24,170 | 16.5 | 0.31 |

| 0.5 – 1.0 | 8,703 | 5.9 | 0.69 |

| 1.0 – 5.0 | 5,582 | 3.8 | 1.8 |

| >5.0 | 274 | 0.2 | 8.3 |

| All doses | 146,425 | 100.0 | 0.23 |

Fig. 4.

Distribution of individual instrumental thyroid doses due to 131I intake calculated in the present study for 146,425 individuals with measured 131I thyroid activity (logarithmic scale of x-axis).

Table 7 gives the distribution of the arithmetic mean of raion-specific population-weighted thyroid doses due to 131I intake for different age groups of the population of raions, cities and towns included in the first and second TDU20 levels. Evacuated towns such as Prypiat, Chornobyl, and Poliske, were not included in the table. On average the highest thyroid doses were estimated in residents of Narodychi raion in Zhytomyr Oblast (0.83 Gy) and of Poliske raion in Kyiv Oblast (0.68 Gy). Thyroid dose estimates differed significantly within oblast due to heterogeneity of radioactive fallout in the most contaminated Zhytomyr, Kyiv and Chernihiv Oblasts as well as other oblasts in Ukraine (Fig. 1).

Table 7.

Distribution of the arithmetic mean of the thyroid doses a due to 131I intake for different age groups of residents of Ukrainian raions, cities, and towns, of the first and second TDU20 levels.

| Raion |

131

I deposition densityb (kBq m–2) |

Thyroid dose a due to

131I intake (Gy) for age group of |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 y | 1–2 y | 3–7 y | 8–12 y | 13–17 y | ≥ 18 y | All ages |

||

| Vinnytsia Oblast | ||||||||

| – Gaisyn | 68 | 0.10 | 0.082 | 0.044 | 0.028 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.040 |

| – Nemyriv | 98 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.098 | 0.063 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.091 |

| Zhytomir Oblast | ||||||||

| – Korosten | 1,090 | 0.56 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| – Luhyny | 1,563 | 0.94 | 0.81 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

| – Malyn | 654 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.38 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.36 |

| – Narodychi | 2,135 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.83 |

| – Ovruch | 1,733 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.33 |

| – Olevsk | 1,460 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.19 |

| – Zhytomir City | 128 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.047 |

| – Korosten town | 1,200 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| – Novograd-Volynsky town | 268 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.035 | 0.064 |

| Kyiv Oblast | ||||||||

| – Borodianka | 486 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.155 | 0.11 | 0.088 | 0.080 | 0.15 |

| – Vyshhorod | 720 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.093 | 0.18 |

| – Ivankiv | 1,085 | 0.36 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.097 | 0.17 |

| – Kyievo-Sviatoshyn | 517 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.061 | 0.050 | 0.052 | 0.096 |

| – Makariv | 357 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.105 | 0.20 |

| – Poliske | 3,249 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.352 | 0.68 |

| – Irpin town | 608 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.093 | 0.058 | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.085 |

| Chernihiv Oblast | ||||||||

| – Kozelets | 322 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.082 | 0.071 | 0.14 |

| – Ripky | 807 | 0.53 | 0.47 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.24 |

| – Chernihiv | 973 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| – Chernihiv City | 1,334 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.079 | 0.064 | 0.084 | 0.14 |

Raion-averaged population-weighted dose.

Raion-averaged population-weighted 131I deposition density.

Table 8 presents the oblast-averaged thyroid doses due to 131I intake for different age groups of the population. The thyroid doses varied with age: the average doses for age groups < 1 year and 1–2 years were 3.5–5.2 times higher than doses for adults since (i) the thyroid mass in children up to 2 years old is 7–10 times less than that of adults (Likhtarov et al. 2013b), and (ii) consumption of cow’s milk by young children was practically the same as by adults (Likhtarev et al. 2006). For children aged 3–7 years, the thyroid doses were about twice higher than for adults, while the thyroid doses for children aged 8–12 and adolescents aged 13–17 years were almost the same as for adults. The highest average population-weighted thyroid doses due to 131I were estimated for residents of Chernihiv (0.15 Gy), Kyiv (0.13 Gy) and Zhytomyr (0.12 Gy) Oblasts followed by Rivne (0.10 Gy) and Cherkasy (0.088 Gy) Oblasts, and Kyiv City (0.076 Gy). The average 131I thyroid dose for the entire Ukrainian population was 0.054 Gy.

Table 8.

Distribution of the arithmetic mean of the thyroid doses a due to 131I intake for different age groups of population by oblast in Ukraine.

| Oblast |

131I deposition density b (kBq m−2) |

Thyroid dose a due to

131I intake (Gy) for age group of |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 y | 1–2 y | 3–7 y | 8–12 y | 13–17 y | ≥ 18y | All ages | ||

| Vinnytsia | 76 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.061 | 0.038 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.055 |

| Volyn | 123 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.058 | 0.036 | 0.030 | 0.029 | 0.053 |

| Luhanskc | 27 | 0.12 | 0.092 | 0.047 | 0.026 | 0.021 | 0.024 | 0.043 |

| Dnipropetrovsk | 33 | 0.077 | 0.059 | 0.030 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.015 | 0.027 |

| Donetsk | 101 | 0.12 | 0.091 | 0.045 | 0.026 | 0.020 | 0.023 | 0.041 |

| Zhytomyr | 490 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.085 | 0.068 | 0.066 | 0.12 |

| Zakarpattia | 57 | 0.085 | 0.069 | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.019 | 0.019 | 0.034 |

| Zaporizhzhia | 38 | 0.079 | 0.061 | 0.031 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.028 |

| Ivano-Frankivsk | 30 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.064 | 0.041 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.059 |

| Kyiv | 407 | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.084 | 0.069 | 0.068 | 0.13 |

| Kirovohrad | 157 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.055 | 0.033 | 0.026 | 0.029 | 0.050 |

| AR Krym | 53 | 0.074 | 0.058 | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.028 |

| Lviv | 59 | 0.079 | 0.063 | 0.032 | 0.018 | 0.015 | 0.017 | 0.029 |

| Mykolaiv | 34 | 0.10 | 0.080 | 0.041 | 0.024 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.038 |

| Odesa | 42 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.053 | 0.030 | 0.024 | 0.028 | 0.048 |

| Poltava | 111 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.054 | 0.032 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.048 |

| Rivne | 394 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.072 | 0.058 | 0.057 | 0.10 |

| Sumy | 124 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.058 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.030 | 0.053 |

| Ternopil | 15 | 0.098 | 0.080 | 0.043 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.021 | 0.039 |

| Kharkiv | 98 | 0.13 | 0.10 | 0.054 | 0.030 | 0.024 | 0.027 | 0.047 |

| Kherson | 43 | 0.093 | 0.073 | 0.038 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.035 |

| Khmelnytskyi | 99 | 0.11 | 0.086 | 0.045 | 0.028 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.041 |

| Cherkasy | 403 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.096 | 0.057 | 0.046 | 0.049 | 0.088 |

| Chernivtsi | 68 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.082 | 0.050 | 0.040 | 0.043 | 0.074 |

| Chernihiv | 703 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.098 | 0.078 | 0.082 | 0.15 |

| Kyiv City | 285 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.084 | 0.042 | 0.033 | 0.044 | 0.076 |

| Sevastopol City | 223 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.027 | 0.035 | 0.060 |

| Entire Ukraine | 138 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.060 | 0.035 | 0.028 | 0.030 | 0.054 |

Oblast-averaged population-weighted dose.

Raion-averaged population-weighted 131I deposition density.

Former Voroshilovgrad Oblast.

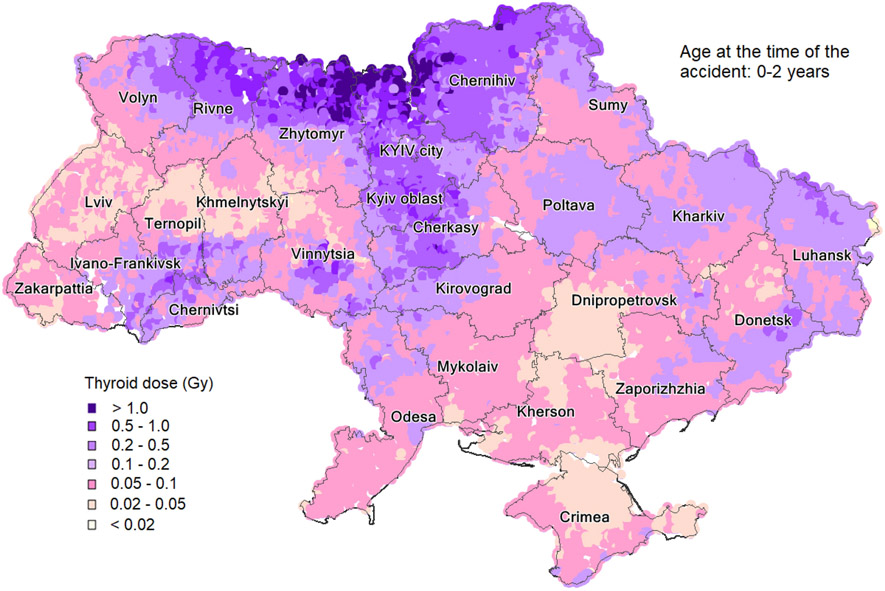

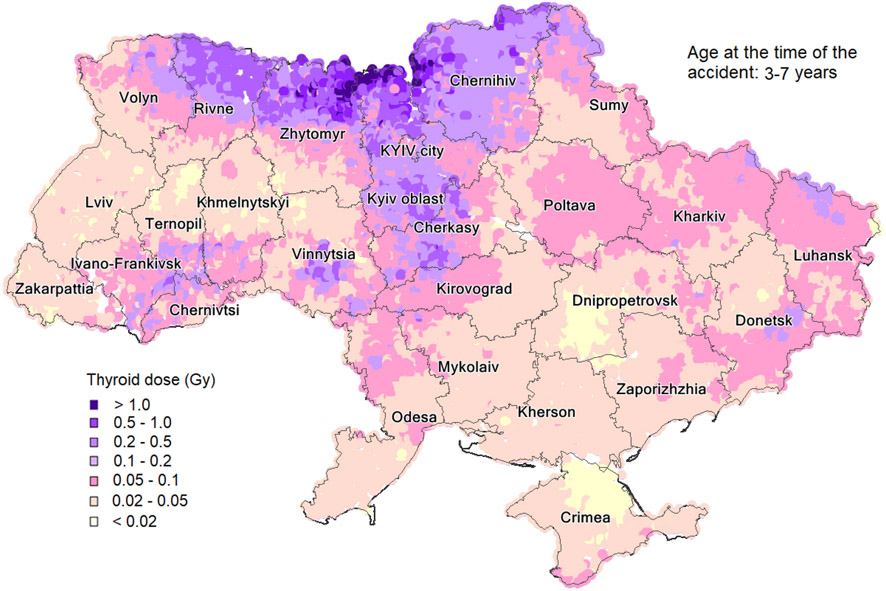

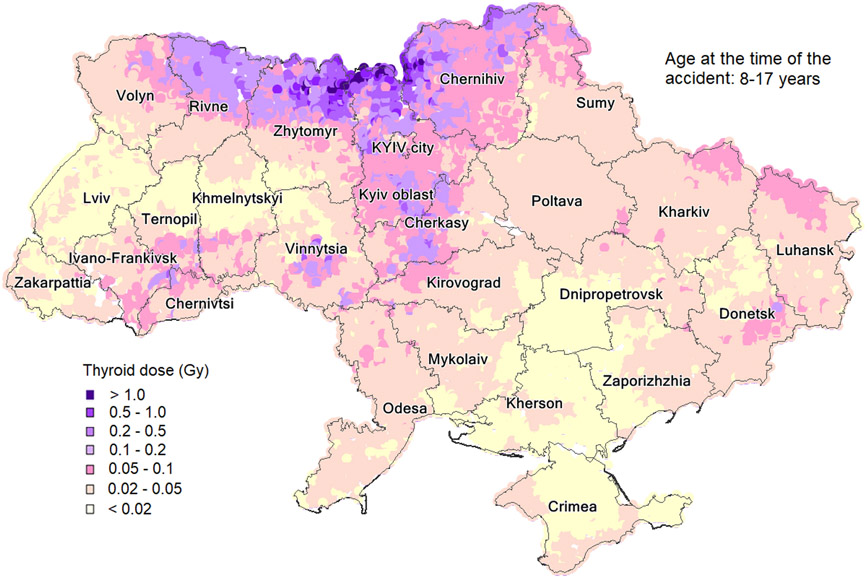

Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8 show the geographical pattern of the thyroid doses due to 131I intake over the Ukrainian territory for individuals aged 0–2, 3–7, 8–17 years and adults, respectively. In general, the pattern of the thyroid doses followed the pattern of 131I ground deposition density (Fig. 1). The highest thyroid doses were received by residents of settlements located at a distance up to 100 km from the Chornobyl NPP. Individual thyroid doses for the most exposed age group (0–2 years) were up to 26 Gy. For most residents of Chernigov, Zhytomyr, Kyiv, Rivne and Cherkasy Oblasts aged 0–2 years, the group-average thyroid doses ranged between 0.1 and 0.5 Gy. Lower thyroid doses, between 0.02 and 0.1 Gy, were estimated for children 0–2 of years who resided ATA in Zakarpatska, Lviv, and Kherson Oblasts, and the Autonomous Republic (AR) Krym as well in most of the settlements in Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia, Khmelnytskyi, Mykolaiv, Odesa, and Ternopol Oblasts.

Fig. 5.

Geographical pattern of thyroid doses due to 131I intake over territory of Ukraine for individuals aged 0–2 years.

Fig. 6.

Geographical pattern of thyroid doses due to 131I intake over territory of Ukraine for individuals aged 3–7 years.

Fig. 7.

Geographical pattern of thyroid doses due to 131I intake over territory of Ukraine for individuals aged 8–17 years.

Fig. 8.

Geographical pattern of thyroid doses due to 131I intake over territory of Ukraine for adults.

Discussion

The thyroid dosimetry system previously developed by Likhtarov et al. (2005) was revised in the present study using available data on (i) revised 131I thyroid activities derived from the direct thyroid measurements done in May and June 1986 on 146,425 individuals (Masiuk et al. 2021); (ii) revised estimates of 131I ground deposition in each Ukrainian settlement (Talerko et al. 2020); and (iii) age- and gender-specific thyroid masses for the Ukrainian population (Likhtarov et al. 2013b). As a result of this in-depth revision, an updated thyroid dosimetry system in Ukraine, called here as TDU20, was created. The thyroid doses were estimated in this study for residents of all 30,353 settlements in 24 oblasts of Ukraine, AR Krym, and the cities of Kyiv and Sevastopol. For each settlement, regardless of the TDU20 level, 38 age- and gender-specific thyroid dose distributions were calculated for each year of age from 0 to 17 years and for adults both, male and female. As a result, the database for the entire Ukraine contains 1,153,414 thyroid dose distributions.

Comparison with previous dose estimates

Table 9 compares the thyroid doses from 131I intake estimated for the Ukrainian population in the present study with those previously estimated by Likhtarov et al. (2005). The table shows the arithmetic and geometric means of the doses estimated in the present study, while previous estimates by Likhtarov et al. (2005) used the geometric means of dose distributions. The ratio of geometric mean of oblast-specific thyroid doses estimated in the present study to previously calculated doses varied from 0.51 to 3.9. The geometric mean of thyroid doses estimated in this study for entire Ukraine essentially did not change in comparison with the previous estimate, 0.020 vs. 0.021 Gy, respectively. The greatest increase in thyroid doses was found for low-dose areas remote from the Chornobyl NPP: 3.9 times for Zakarpatska Oblast, 3.5 times for Luhansk Oblasts, and 2.9 times for Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

Table 9.

Comparison of oblast-averaged thyroid doses from 131I intake estimated in this study with doses previously estimated by Likhtarov et al. (2005).

| Oblast | Thyroid dose due to

131I intake (Gy) |

Ratio of quantities obtained

(used) in this study to previously estimated (used) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | Previously estimated (GM)c |

Thyroid doses (ratio of GM) |

131I

ground deposition density (Talerko etal. 2020) |

131I

thyroid activity d (Masiuk etal. 2021) |

||

| AMa | GMb | |||||

| Vinnytsia | 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.014 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.3 |

| Volyn | 0.053 | 0.020 | 0.035 | 0.57 | 0.96 | – |

| Luhansk e | 0.043 | 0.015 | 0.0043 | 3.5 | 4.5 | – |

| Dnipropetrovsk | 0.027 | 0.0093 | 0.0055 | 1.7 | 1.6 | – |

| Donetsk | 0.041 | 0.014 | 0.0091 | 1.5 | 0.90 | – |

| Zhytomyr | 0.12 | 0.049 | 0.087 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.53 |

| Zakarpatska | 0.034 | 0.013 | 0.0033 | 3.9 | 0.95 | – |

| Zaporizhzhia | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.011 | 0.91 | 1.1 | – |

| Ivano-Frankivsk | 0.059 | 0.022 | 0.0075 | 2.9 | 5.6 | – |

| Kyiv | 0.13 | 0.051 | 0.081 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 1.2 |

| Kirovohrad | 0.050 | 0.018 | 0.035 | 0.51 | 0.82 | – |

| AR Krym | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.71 | 0.99 | – |

| Lviv | 0.029 | 0.010 | 0.0060 | 1.7 | 0.97 | 1.2 |

| Mykolaiv | 0.038 | 0.014 | 0.0085 | 1.6 | 2.7 | – |

| Odesa | 0.048 | 0.017 | 0.0060 | 2.8 | 4.1 | – |

| Poltava | 0.048 | 0.017 | 0.021 | 0.81 | 0.99 | – |

| Rivne | 0.10 | 0.039 | 0.071 | 0.55 | 0.99 | – |

| Sumy | 0.053 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.68 | 1.0 | – |

| Ternopil | 0.039 | 0.015 | 0.0073 | 2.1 | 6.4 | – |

| Kharkiv | 0.047 | 0.017 | 0.0094 | 1.8 | 0.99 | – |

| Kherson | 0.035 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.86 | 1.0 | – |

| Khmelnytskyi | 0.041 | 0.015 | 0.016 | 0.94 | 0.96 | – |

| Cherkasy | 0.088 | 0.032 | 0.055 | 0.58 | 0.87 | – |

| Chernivtsi | 0.074 | 0.027 | 0.015 | 1.8 | 4.2 | – |

| Chernihiv | 0.15 | 0.060 | 0.058 | 1.0 | 0.97 | 1.3 |

| Kyiv City | 0.076 | 0.031 | 0.032 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.1 |

| Sevastopol City | 0.060 | 0.020 | 0.020 | 1.0 | 1.0 | – |

| Entire Ukraine | 0.054 | 0.020 | 0.021 | 0.95 | 1.7 | 0.72 |

Oblast-specific arithmetic mean.

Oblast-specific geometric mean.

Oblast-specific geometric mean according to Likhtarov et al. (2005).

Among measured individuals only.

Former Voroshilovgrad Oblast.

Reliability of thyroid dose estimates

The individual scaling factor, , which was defined as the ratio of the ‘measured’ 131I activity in the thyroid to the ‘ecological’ 131I activity at the time of measurement (see Eq. (3)), integrates all steps of the thyroid dose estimation: results of direct thyroid measurement, modeling, and individual behavior and dietary data, if available. The scaling factor is an indicator of the agreement between the dose estimated using the model and that derived from a direct thyroid measurement. The arithmetic mean of the scaling factor for 146,425 measured individuals was 0.84 (median of 0.35). Figure 2 shows the distribution of the scaling factors (logarithmic values) related to the thyroid doses due to 131I intake calculated for 146,425 individuals with direct thyroid measurements. The distribution of -values was close to log-normal with a median equal to 0.35 and a GSD of 3.8 while the 5%–95% dose interval was 0.037–3.0.

Since Eq. (1) defines the individual scaling factor as the ratio of instrumental and ecological thyroid doses , the ecological thyroid dose was, on average, higher than the instrumental dose. Figure 9 shows the dependence of the individual scaling factor values, , for 146,425 measured individuals obtained from the instrumental thyroid doses due to 131I intake; rp=0.48 (p<0.001) for logarithmic values, and rp=0.34 (p<0.001) for linear values. For individuals with thyroid doses less than 0.01 Gy, the scaling factor did not exceed 1.0 in most cases, while for individuals with doses greater than 5.0 Gy, the scaling factor was usually greater than 1.0. The best agreement between the ecological and instrumental thyroid doses ( ≈ 1.0) was for individuals with doses in the range from 0.01 to 1.0 Gy. The variability of the -values was observed due to the fact that the ecological dose was calculated by the ecological model that is based on average parameters of iodine trophic transfer, while the instrumental dose took into account individual behavior, which, in general, determined the measured 131I thyroid activity.

Fig. 9.

Dependence of individual scaling factor values, , for 146,425 measured individuals, on instrumental thyroid doses due to 131I intake.

Table 2 gives the distribution of the mean scaling factor by age ATA and gender among 146,425 individuals measured for 131I thyroid activity in Ukraine. There was an inverse correlation between scaling factor and age, rp=−0.70 (p<0.001) for boys, rp=−0.67 (p=0.0026) for girls, and rp=−0.68 (p=0.0018) for boys and girls combined. The highest scaling factor values for infants aged under one year were associated with specifics of their diet, i.e., the dose reconstruction model considered for them consumption of 0.8 L d−1 of breast milk; however, these infants could have consumed other foodstuffs that were not included in the model.

Figure 10 shows the geographical pattern of the scaling factor values estimated for all Ukrainian settlements. It should be noted that the most reliable dose estimates were obtained for 835 settlements from the first TDU20 level, since these estimates were based on direct thyroid measurements of their residents. The thyroid dose estimates for the residents of 690 settlements from the second TDU20 level were based on measurements done in neighboring settlements located in the same area, and, therefore, these doses can be considered as moderate reliable. The thyroid dose estimates for the residents of 28,828 settlements of the third TDU20 level were the least reliable. Note that all of the 146,425 direct measurements were performed in settlements within 300 km of the Chornobyl NPP (about two thousand direct thyroid measurements were done in residents of settlements in Vinnitsa Oblast, which are the most distant and located around 300 km from the Chornobyl NPP). In contrast, thyroid dose estimates for the residents of the settlements located at distances of more than 300 km from the Chornobyl NPP were characterized by a low reliability.

Fig. 10.

Geographical pattern of scaling factor values estimated for all Ukrainian settlements.

Contribution of short-lived 132Te+132I and 133I to the thyroid dose

In addition to 131I with a radioactive half-life of 8.02 d, a number of short-lived radioiodine and radiotellurium isotopes were also released into the environment after the Chornobyl accident. The most important contributors to the thyroid exposure were 132Te (half-life: 3.2 d), 132I (half-life: 2.3 h), and 133I (half-life: 20.8 h). Wide-scale direct thyroid measurements of 131I thyroid activity in the thyroid gland began in Ukraine in the second half of May. Therefore, radiation from short-lived radionuclides was not recorded during these measurements because by that time these radionuclides had almost completely decayed. Their contribution to the total thyroid dose was assessed by the methodology described in (Likhtarev et al. 2014) using the initial isotope ratio at the time of the accident (Likhtarev et al. 2002; Mück et al. 2002) and the dynamics of 131I deposition on the ground surface (Talerko et al. 2020).

Table 10 gives the distribution of the mean contribution of short-lived radioisotopes (132Te+132I and 133I) to the total thyroid dose by raion. The results are given for those raions in the northern oblasts in Ukraine where at least 500 direct thyroid measurements were done in May-June 1986. The most significant contribution of short-lived radionuclides (19–26 % depending on age) was estimated for the residents of Prypiat with 131I intake via inhalation of contaminated air. This is consistent with the results of in vivo measurements of evacuated Prypiat residents done in Saint Petersburg (formerly called Leningrad). According to these in vivo measurements, the mean contribution of 133I, 132I, and 132Te to total thyroid doses was 30% in residents evacuated from Prypiat who did not take potassium iodide to block radioiodine uptake by the thyroid gland during the first 1.5 d after the accident (Balonov et al. 2003).

Table 10.

Distribution of the arithmetic mean contribution of short-lived radioisotopes (132Te+132I and 133I) to the total thyroid dose by raion.

| Raion | Contribution (%) for all ages from |

Contribution (%) of 132Te+ 132I and

133I for the total thyroid dose for the following age groups |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 132Te+132I | 133I | Total | 0–2 y | 3–7 y | 8–17 y | ≥18 y | |

| Vinnytsia Oblast | |||||||

| – Gaisyn | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.95 | 1.0 | – |

| – Nemyriv | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 0.54 | 0.91 | 1.0 | – |

| Zhytomir Oblast | |||||||

| – Korosten | 1.9 | 4.0 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 5.0 |

| – Narodychi | 1.5 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 5.0 |

| – Ovruch | 1.8 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 5.0 |

| – Olevsk | 1.9 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.6 | 5.1 |

| – Korosten town | 4.2 | 5.0 | 9.3 | – | 9.7 | 9.3 | 6.5 |

| Kyiv Oblast | |||||||

| – Borodianka | 1.3 | 0.16 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.92 |

| – Vyshhorod | 1.6 | 0.20 | 1.8 | – | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| – Ivankiv | 1.4 | 0.70 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.3 |

| – Makariv | 1.3 | 0.11 | 1.4 | – | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.81 |

| – Poliske | 2.3 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 6.9 | 5.4 |

| – Chornobyl | 3.0 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 3.7 |

| – Irpin town | 1.5 | 0.16 | 1.6 | – | 1.4 | 1.7 | – |

| – Prypiat town | 12 | 12 | 24 | 22 | 26 | 24 | 19 |

| Chernihiv Oblast | |||||||

| – Kozelets | 1.2 | 0.24 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 0.97 |

| – Ripky | 1.4 | 0.99 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 1.9 |

| – Chernihiv | 1.5 | 0.73 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| – Chernihiv City | 1.9 | 0.70 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 1.5 |

| Kyiv City | 2.2 | 0.21 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.97 |

| Total | 2.0 | 2.3 | 4.4 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

The largest contribution of 133I, 132I, and 132Te to the total thyroid dose was estimated for the residents of raions closest to the Chornobyl NPP where the deposition of radionuclides occurred on the first day of the accident. A contribution of short-lived radionuclides to total thyroid dose of around 4–10% depending on age was estimated for the residents of Poliske and Chornobyl raions in Kyiv Oblast, and for Korosten, Narodychi, Ovruch, and Olevsk raions, and Korosten-town in Zhytomyr Oblast. The contribution of 133I, 132I, and 132Te to total thyroid dose for the residents of other areas did not exceed 3%.

Conclusions

This paper describes the revision of the thyroid dosimetry system in Ukraine and the revised estimates of age- and gender-group specific thyroid doses due to 131I intake for the residents of 30,353 Ukrainian settlements. All settlements were divided in the dosimetry system into three levels depending on availability of direct instrumental measurements of 131I thyroid activity done among their residents. Among them, the most reliable thyroid dose estimates were obtained for the residents of 835 settlements where the direct thyroid measurements were conducted in more than ten residents. Less reliable doses were estimated for the residents of 690 settlements based on 131I thyroid measurements done in neighboring settlements. The least reliable thyroid doses, which were based on a purely empirical relationship between the thyroid doses due to 131I intake and the cumulative 131I ground deposition densities in the settlements, were estimated for the residents of 28,828 settlements typically located at distances of more than 300 km from the Chornobyl NPP. The arithmetic mean of thyroid doses due to 131I intake in entire Ukrainian population was 0.054 Gy, the median was 0.020 Gy, while the maximal individual thyroid dose was 26 Gy. A contribution of short-lived 133I, 132I, and 132Te to the total thyroid dose of around 1–10 % was estimated for the non-evacuated residents of raions closest to the Chornobyl NPP. The revised thyroid dosimetry system TDU20 is being used to revise the previous thyroid dose estimates for the individuals of the Ukrainian-American cohort (Likhtarov et al. 2014), the Ukrainian in utero cohort (Likhtarov et al. 2011), and Ukrainian individuals enrolled in the Chornobyl Tissue Bank (Likhtarov et al. 2013a).

Acknowledgement

This paper is dedicated to the memory of the late Ilya Likhtarov, who was creator of the 131I thyroid dosimetry system for the Ukrainian population the Chornobyl accident. We would like gratefully to acknowledge the contributions of Lionella Kovgan, André Bouville, and Paul Voilleque at different stages of the development of the thyroid dosimetry system.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, state registrations #0111U000757 and #0114U002845, for A. Kukush by the National Research Fund of Ukraine grant #2020.02/0026, and by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NCI, NIH) within the framework of the Ukrainian-American Study of Thyroid Cancer and Other Diseases Following the Chernobyl Accident (Protocol #OH95–C–NO20) through contract HHSN261201600298P between the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Science and Technology Center in Ukraine (STCU).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This AM is a PDF file of the manuscript accepted for publication after peer review, when applicable, but does not reflect post-acceptance improvements, or any corrections. Use of this AM is subject to the publisher's embargo period and AM terms of use. Under no circumstances may this AM be shared or distributed under a Creative Commons or other form of open access license, nor may it be reformatted or enhanced, whether by the Author or third parties. See here for Springer Nature's terms of use for AM versions of subscription articles: https://www.springernature.com/gp/open-research/policies/accepted-manuscript-terms

Conflict of interest The authors declare that this work was carried out in the absence of any personal, professional or financial relationships that could potentially be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Sergii Masiuk, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Mykola Chepurny, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Valentyna Buderatska, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Olga Ivanova, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Zulfira Boiko, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Natalia Zhadan, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Galyna Fedosenko, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Andriy Bilonyk, State Institution “National Research Center for Radiation Medicine of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine”, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Alexander Kukush, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Tatiana Lev, Institute for Safety Problems of Nuclear Power Plants, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Mykola Talerko, Institute for Safety Problems of Nuclear Power Plants, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv, Ukraine.

Vladimir Drozdovitch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, DHHS 9609 Medical Center Drive, Room 7E548 MSC 9778, Bethesda, MD 20892-9778, USA.

References

- Balonov M, Kaidanovsky G, Zvonova I, Kovtun A, Bouville A, Luckyanov N, Voilleque P (2003) Contributions of short-lived radioiodines to thyroid doses received by evacuees from the Chernobyl area estimated using early in vivo activity measurements. Radiat Prot Dosim 105:593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouville A, Likhtarev I, Kovgan L, Minenko V, Shinkarev S, Drozdovitch V (2007) Radiation dosimetry for highly contaminated Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian populations, and for less contaminated populations in Europe. Health Phys 93:487–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulko GM, Chumak VV, Chepurny NI, Henrichs K, Jacob P, Kairo IA, Likhtarev IA, Repin VS, Sobolev BG, Voigt G (1996) Estimation of 131I thyroid doses for the evacuees from Pripjat. Radiat Environ Biophys 35:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulko GM, Chepurny NI, Jacob P, Kairo IA, Likhtarev IA, Pröhl G, Sobolev BG (1998) Thyroid dose and thyroid cancer incidence after the Chernobyl accident: assessments for the Zhytomyr region (Ukraine). Radiat Environ Biophys 36:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirnenko VI, Standyuk VI (1987) Ukrainian SSR: Administrative-territorial system (as of 1 January 1987). Kyiv: Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia, 504 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarev IA, Shandala NK, Gulko GM, Kairo IA, Chepurny NI (1993) Ukrainian thyroid doses after the Chernobyl accident. Health Phys 64:594–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarev IA, Gulko GM, Sobolev BG, Kairo IA, Chepurnoy NI, Pröhl G, Henrichs K (1994) Thyroid dose assessment for the Chernigov region (Ukraine): estimation based on 131I thyroid measurements and extrapolation of the results to districts without monitoring. Radiat Environ Biophys 33:149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarev IA, Kovgan LN, Jacob P, Anspaugh LR (2002) Chornobyl accident: retrospective and prospective estimates of external dose of the population of Ukraine. Health Physics 82: 290–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarev I, Minenko V, Khrouch V, Bouville A (2003) Uncertainties in thyroid dose reconstruction after Chernobyl. Radiat Prot Dosim 105:601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarev I, Bouville A, Kovgan L, Luckyanov N, Voillequé P, Chepurny M (2006) Questionnaire- and measurement-based individual thyroid doses in Ukraine resulting from the Chornobyl nuclear reactor accident. Radiat Res 166:271–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarov I, Kovgan L, Vavilov S, Chepurny M, Bouville A, Luckyanov N, Jacob P, Voilleque P, Voigt G (2005) Post-Chornobyl thyroid cancers in Ukraine. Report 1: Estimation of thyroid doses. Radiat Res 163:125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarov I, Kovgan L, Chepurny M, Ivanova O, Boyko Z, Ratia G, Masiuk S, Gerasymenko V, Drozdovitch V, Berkovski V, Hatch M, Brenner A, Luckyanov N, Voillequé P, Bouville A (2011) Estimation of the thyroid doses for Ukrainian children exposed in utero after the Chernobyl accident. Health Phys 100:583–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarov I, Thomas G, Kovgan L, Masiuk S, Chepurny M, Ivanova O, Gerasymenko V, Tronko M, Bogdanova T, Bouville A (2013a) Reconstruction of individual thyroid doses to the Ukrainian subjects enrolled in the Chernobyl Tissue Bank. Radiat Prot Dosim 156:407–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarov I, Kovgan L, Masiuk S, Chepurny M, Ivanova O, Gerasymenko V, Boyko Z, Voillequé P, Antipkin Y, Lutsenko S, Oleynik V, Kravchenko V, Tronko M (2013b) Estimating thyroid masses for children, infants and fetuses in Ukraine exposed to 131I from the Chornobyl accident. Health Phys 104:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtarov I, Kovgan L, Masiuk S, Talerko M, Chepurny M, Ivanova O, Gerasymenko V, Boyko Z, Voilleque P, Drozdovitch V, Bouville A (2014) Thyroid cancer study among Ukrainian children exposed to radiation after the Chornobyl accident: improved estimates of the thyroid doses to the cohort members. Health Phys 106:370–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiuk S, Chepurny M, Buderatska V, Kukush A, Shklyar S, Ivanova O, Boiko Z, Zhadan N, Fedosenko G, Bilonyk A, Lev T, Talerko M, Kutsen S, Minenko V, Viarenich K, Drozdovitch V (2021) Thyroid doses in Ukraine due to 131I intake after the Chornobyl accident. Report I: Revision of direct measurements of radioactivity in the thyroid. Radiat Environ Biophys 2021 60:267–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mück K, Pröhl G, Likhtarev IA, Kovgan L, Meckbach R, Golikov V (2002) A consistent radionuclide vector after the Chernobyl accident. Health Phys 82:156–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talerko N (2005) Reconstruction of 131I radioactive contamination in Ukraine caused by the Chernobyl accident using atmospheric transport modelling. J Environ Radioact 84:343–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talerko MM, Lev TD, Drozdovitch VV, Masiuk SV (2020) Reconstruction of radioactive contamination of the territory of Ukraine by Iodine-131 in the initial period of the Chornobyl accident using the results from numerical WRF model. Probl Radiac Med Radiobiol 25:285–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) (2011) Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, UNSCEAR 2008 Report. Annex D: Health effects due to radiation from the Chernobyl accident. Sales No. E.11.IX.3. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]