Abstract

Objective:

Species-specific pseudogenization of the CMAH gene during human evolution eliminated common mammalian sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) biosynthesis from its precursor, N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac). With metabolic non-human Neu5Gc incorporation into endothelia from red meat, the major dietary source, anti-Neu5Gc-antibodies appeared. Human-like Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice on a high-fat diet (HFD) supplemented with a Neu5Gc-enriched mucin, to mimic human red meat consumption, suffered increased atherosclerosis if human-like anti-Neu5Gc-antibodies were elicited.

Approach and Results:

We now ask if interventional Neu5Ac feeding attenuates metabolically incorporated Neu5Gc-mediated inflammatory acceleration of atherogenesis in this Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− model system. Switching to a Neu5Gc-free HFD or adding a 5-fold excess of Collocalia mucoid-derived Neu5Ac in HFD protects against accelerated atherosclerosis. Switching completely from a Neu5Gc-rich to a Neu5Ac-rich diet further reduces severity. Remarkably, feeding Neu5Ac-enriched HFD alone has a substantial intrinsic protective effect against atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice even in the absence of dietary Neu5Gc, but only in the human-like Cmah-null background.

Conclusion:

Interventional Neu5Ac feeding can mitigate or prevent the red-meat/Neu5Gc-mediated increased risk for atherosclerosis, and has an intrinsic protective effect, even in the absence of Neu5Gc feeding. These findings suggest that similar interventions should be tried in humans, and that Neu5Ac-enriched diets alone should also be investigated further.

Keywords: Human Evolution, Species Conservation, Edible Bird’s nest, Sialic acid, Atherosclerosis, N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc), Cytidine monophosphate (CMP)-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH)

INTRODUCTION

Sialic acids (Sias) are a family of nine-carbon-backbone monosaccharides prominently displayed on glycans attached to most cell surface and secreted molecules of all vertebrate cells1–5. In keeping with their location, prominence, and extensive structural diversity, Sias mediate or modulate a wide variety of biological processes in health and disease5–10. The most common Sia in mammals is N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), which is often converted into the next most common type, N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc). Independent inactivation events of the CMAH gene encoding the CMAH enzyme that mediates conversion of Neu5Ac to Neu5Gc (by addition of a single oxygen atom) have occurred in certain vertebrate taxa, including humans and birds11–13. However, metabolic incorporation of diet-derived Neu5Gc occurs in humans who consume red meat (the richest common source of dietary Neu5Gc), resulting in endogenous cell surface display of small amounts of Neu5Gc-glycans in endothelia and some epithelia. These incorporated Neu5Gc-glycans then act as “xeno-autoantigens” that can interact with circulating anti-Neu5Gc-glycan “xeno-autoantibodies”, generating a novel diet-mediated inflammatory process called “xenosialitis”14–18.

Our prior work in human-like Neu5Gc-deficient Cmah-null mice showed that this inflammatory “xenosialitis” process accelerates progression of carcinomas19 and of atherosclerosis20, likely contributing towards the human-specific association of these diseases with consumption of red meat (particularly processed red meats, that may perhaps have more bioavailable Neu5Gc)21,22. Independent of this extrinsic mechanism, we also found that the human-like Neu5Gc-deficient Cmah-null mice already had an intrinsic propensity to develop severe aortic atherosclerotic plaques, via multiple mechanisms, including an augmented immune reactivity20. We suggested that these factors contribute to the unusual propensity of humans to develop severe atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease23–25, which now accounts for one-third of deaths worldwide.

Collocalia mucoid has long been known to biochemists as a rich source of Neu5Ac (~9% w/w)26 and is the primary component of Edible bird’s nest (EBN), a popular but very expensive Chinese health food, often referred to as the “Caviar of the East”27. The nests are highly enriched in salivary mucins of the White-nest (Aerodramus fuciphogus) or Black-nest Swiftlet (Aerodramus maximus)27,28. The very high content of Neu5Ac is not surprising, as salivary mucins are very rich in sialic acids (indeed, “sialic acid” is derived from the word saliva) 29. In the present study, we consider the possibility that some of the claimed health benefits of EBN may be related to its rich content of mucin-associated Neu5Ac (the rest of the composition of EBN consists of common neutral monosaccharides and amino acids)30. We tested and confirmed that dietary intervention with EBN can attenuate both the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that drive accelerated atherosclerosis development associated with the human-like Neu5Gc-deficiency in Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice. The study also addresses potential implications for the preservation of the Chinese swiftlet species, which are under ecological pressure due to the increased commercial activity with the harvesting of their nests31–33.

RESULTS

Switching to a Neu5Gc-free diet attenuates atherogenesis-induced by dietary Neu5Gc-glycoproteins and anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice.

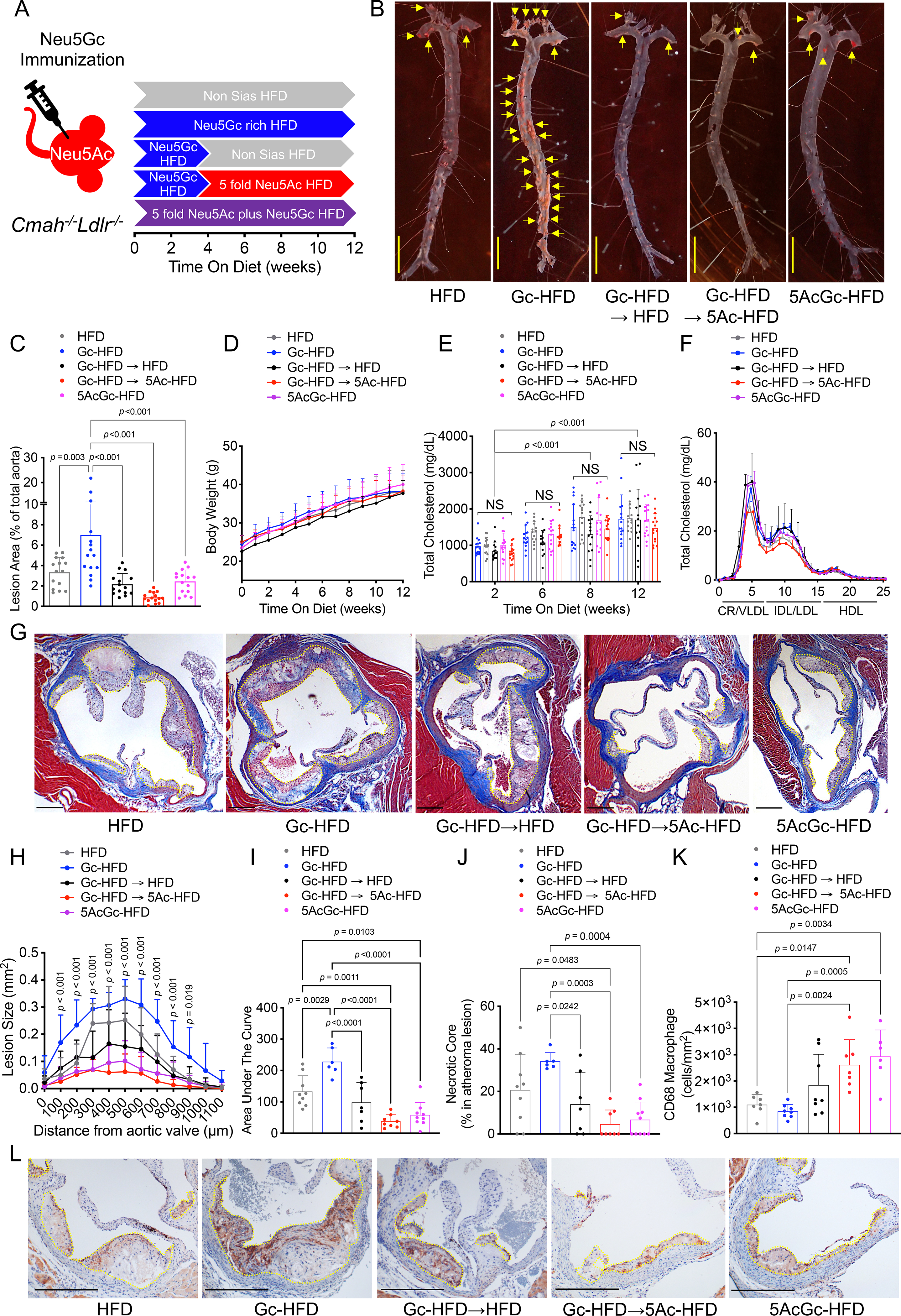

In a previous study, we showed that aortic atherosclerosis induced by the high fat diet (HFD) feeding of Ldlr-deficient mice is aggravated by introducing a human-like Cmah-null state via multiple intrinsic mechanisms20. This human-like atherosclerosis-prone state was further aggravated by feeding a diet containing the non-human sialic acid Neu5Gc (which is enriched in red meat and metabolically incorporated into human endothelium in vivo)20, but only if anti-Neu5Gc antibodies were also induced in the same mice––further mimicking the situation of humans who consume processed red meat. To determine if this “xenosialitis” phenomenon could be attenuated, we changed the diet of the Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice 4 weeks after induction of human-like Neu5Gc antibodies and feeding a Neu5Gc-rich diet, to a Neu5Gc-free diet, identical to the non-sialic acid soy-based high fat diet (HFD), for a further period of 8 weeks (Gc-HFD→HFD) (Figure 1A). This intervention, analogous to stopping red meat intake in humans, significantly reduced atherosclerotic plaques compared to a continuous Neu5Gc-HFD feeding (Figure 1B and C). These differences in sizes of the atherosclerotic plaques were independent of body weight changes (Figure 1D) or plasma cholesterol concentrations (Figure 1E), and despite elevation of atherogenic serum levels of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (Figure 1F and S1). Reduction in atherosclerosis plaque size was confirmed by histological analysis using Masson’s trichrome histochemical stain (Figure 1G and Supplemental Fig. S2). Importantly, atherosclerotic plaque sizes calculated from serial images taken starting at the aortic valve, were significantly smaller, and the size of the necrotic core was reduced, after the diet switch from a Neu5Gc-HFD to non-Sia HFD (Figure 1H, I and J).

Figure 1. Impact of modulating Neu5Gc and Neu5Ac dietary content in a human-like xenosialitis atherosclerosis mouse model.

(A) Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− mice were immunized with Neu5Gc antigen (Gc Immunization) to induce human-like anti-Neu5Gc antibodies, then fed with; non-Sias HFD (HFD) for 12 weeks; or Neu5Gc-rich HFD (Gc-HFD) for 12 weeks; or Gc-HFD for 4 weeks followed by switching to a non-Sias HFD for 8 weeks (Gc-HFD→HFD); or Gc-HFD for 4 weeks then switching to 5 fold Neu5Ac-HFD for 8 weeks (Gc-HFD→5Ac-HFD); or a premix of 5 fold Neu5Ac over Neu5Gc for 12 weeks (5AcGc-HFD), (n = 14–16, each). (B) En face analysis of atherosclerotic plaques (yellow arrows), and (C) quantification of lipid-rich Sudan IV-positive plaques in aorta. (D) Body weight change for 12 weeks in each group. (E) Plasma total cholesterol (n = 14–16) and (F) FPLC analysis of lipoproteins after 12 weeks of each HFD feeding (3 pooled plasma from n = 4–6 each), chylomicron remnant, CR; very-low-density lipoprotein, VLDL; Intermediate-density lipoprotein, IDL; low-density lipoprotein, LDL; high-density lipoprotein, HDL. (G) Atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic sinus were evaluated with Masson’s trichrome (plaques indicated with yellow dotted line and necrotic cores indicated with red dotted lines). (H) quantification of atherosclerotic plaque size (yellow dots) in the aortic sinus and (I) area under the curve, (J) necrotic core size (red dots), and (K) CD68 infiltration density were calculated in the plaque (yellow dots) (n = 6–8, each). (L) Atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic sinus were evaluated with anti-CD68 immunostain. Shown are male data, black bars = 300 μm, mean (SD), One-Way ANOVA, Two-Way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher LSD post hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

Changing from a Neu5Gc-rich diet to Neu5Ac-enriched diet, caused a maximum reduction of xenosialitis-mediated atherosclerotic plaques.

Maximum reduction in atherosclerosis development due to Neu5Gc-mediated xenosialitis was obtained by switching Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice, 4-weeks after induction of human-like Neu5Gc antibodies and after feeding a Neu5Gc-rich to a HFD with EBN-derived Neu5Ac (5-fold excess) for another 8 weeks (Gc-HFD→5Ac-HFD) (Figure 1A–J). The atherosclerotic plaques in the group (Gc-HFD→5Ac-HFD) were significantly smaller and predominantly rich in CD68+ macrophages (Fig. 1K–L). This suggests development of only early fatty streaks and a lack of more intermediate and advanced lesions even when compared to HFD-fed mice. This observation is in stark contrast to the Neu5Gc xenosialitis group (Gc-HFD) where plaques developed substantial necrotic cores, as previously reported20 (Figure 1J–L). This striking protective effect and significant shift to an earlier atherosclerotic plaque morphology is further supported by the almost complete lack of necrotic cores. This observation in the Gc-HFD→5Ac-HFD treatment arm was associated with a reduction in the serum LDL-cholesterol levels and hepatic triglyceride accumulation (Fig. 1F and Supplemental Fig. S3). Hence, these findings imply that negative cardiovascular effects of Neu5Gc found predominantly in red meat might be counteracted by consuming Neu5Ac-enriched food groups (such as poultry).

Mixing Five-fold excess of Neu5Ac-rich in a Neu5Gc-rich HFD reduces xenosialitis-mediated aggravation of atherosclerosis.

We have previously shown in cultured cells that Neu5Ac can metabolically compete for Neu5Gc incorporation34. We now asked if the same type of competition would act in this mouse model of atherosclerosis (Figure 1A). This question was addressed by using the Ldlr−/−Cmah−/− mice, after the induction of human-like Neu5Gc antibodies, and feeding the animals a Neu5Gc-rich HFD but mixed with a 5-fold excess of EBN-derived Neu5Ac, for a period of 12 weeks (5AcGc-HFD). We observed a significant decrease in the size of the atherosclerotic plaques in the 5AcGc-HFD fed group, compared to the Neu5Gc-HFD fed group or non-Sias HFD (Figure 1B–C and 1G–I). This anti-atherogenic effect was observed despite inducing elevated circulating triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (Figure S1B). Notably, this intervention was also associated with a significant reduction in necrotic core formation and the plaques were macrophage-rich, compared to the plaque sizes in animals which did not receive Neu5Gc in their diets although on a HFD) (Figure 1J–L). These findings suggest that incorporation of Neu5Ac-rich glycoproteins into processed red meat products (or reduced Neu5Gc absorption in general) could result in suppression of Neu5Gc-induced atherogenic events.

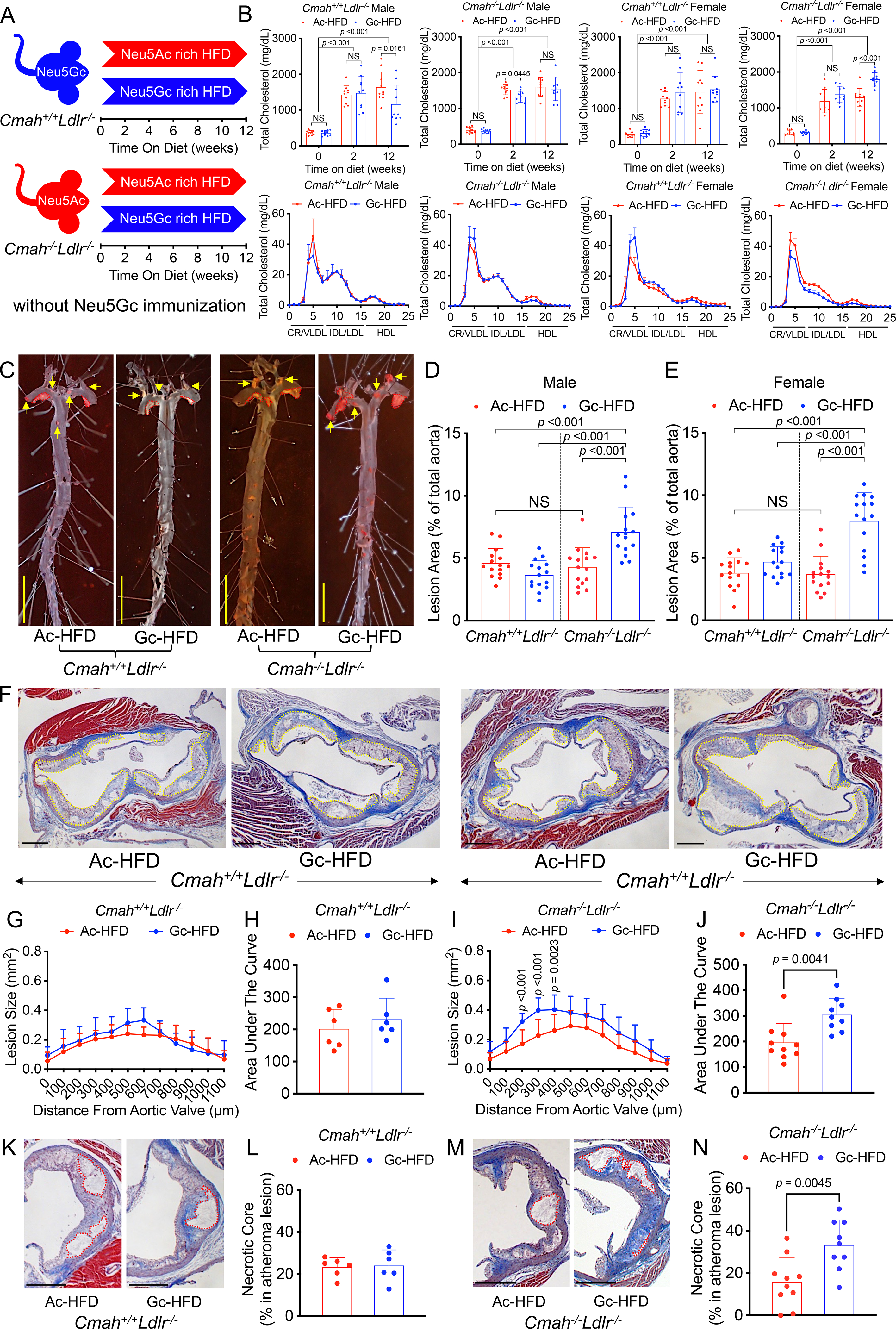

Feeding EBN with HFD has a strong protective effect against development of atherosclerotic plaques in Ldlr−/− mice but only in the human-like Cmah-null background.

We previously reported that mice with the human-like Cmah-null background have an intrinsically increased propensity to developing aortic atherosclerotic plaques when fed a HFD in an Ldlr-deficient20. While re-analyzing some of this data as well as contemporaneous unpublished mouse cohorts, we noted that the propensity to develop atherosclerosis and unstable atheromas is suppressed by feeding of Neu5Ac-rich EBN alone (Figure 2A–N). This effect was not seen in the Ldlr-deficient Cmah wild-type mice (Figure 2A–E). These findings indicate that consumption of Neu5Ac-rich EBN can have a major protective effect independent of its impact on red meat and Neu5Gc. Importantly, Neu5Gc-rich HFD itself (without Neu5Gc antibodies) did not change atheromatous plaques when we compare the data with the mice on non-Sia HFD20, although some body weight change occurred (Supplemental Fig. S4). The Neu5Ac-protective effect was not associated with a reduction in CVD risk factors including plasma lipoproteins, such as chylomicron (CR) and very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) or hepatic lipidosis (Figure 2B, Supplemental Fig. S5 and S6). The Neu5Ac-protective effect did associate with suppression of cytokine expression in macrophages (Supplemental Fig. S7). However, no difference in macrophage foam cell conversion was observed with Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc feeding in human THP-1-derived macrophages (Supplement Fig.8). Changes in the microbiome induced by adding Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc to the diet are also potential contributing factors.30

Figure 2. Atheroprotective effect of Neu5Ac alone occurs only in human-like Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− Mice.

(A) Neu5Ac-rich EBN (Ac) or Neu5Gc-rich PSM (Gc) were added to a soy-based non-Sias HFD (Ac-HFD or Gc-HFD), feeding Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− and Cmah+/+Ldlr−/− mice during 6 to 18 weeks, without any prior immunization. (B) Plasma total cholesterol (n = 14–16) and FPLC analysis of lipoproteins after 12 weeks of each HFD feeding (3 pooled serum from male and female, n = 4–6) as Figure. 1. (C) En face analysis of atherosclerosis (red dots and yellow arrow show in female atheroma lesions, yellow bar = 500 μm), and quantification of Sudan IV-positive area I shown in male (D), and female (E) (n = 14–16). (F) Cmah+/+Ldlr−/− and Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− female were analyzed 12 weeks after Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc added HFD feeding for atherosclerotic plaque development in the aortic root (n = 6 each). (G-J) Quantification of total atherosclerotic plaque size (white dotted lines) in the aortic sinus with Masson’s trichrome stain; area under the curve data shown. (K-N) Necrotic core (red dotted lines) size analysis. Shown are black bars = 300 μm, mean (SD), Unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t test, Mann Whitney test, One-Way ANOVA, Two-Way ANOVA with uncorrected Fisher LSD post hoc test or Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

DISCUSSION

This work brings together several seemingly disparate fields: Edible Bird’s nest as a traditional Chinese “health food”, also known as Collocalia mucoid, long recognized by sialic acid researchers as a rich source of the human dominant sialic Neu5Ac; a novel mechanism for the risk of increased atherosclerosis associated with red meat consumption, and potential interventions using Collocalia mucoid, the primary component of Sia-rich EBN). There are some prior studies indicating that EBN could ameliorate HFD induced hyperlipidemia and hypercoagulation35 and insulin resistance36,37, but these studies were done in rats (which, unlike our mouse model did not have the human-like Cmah deficiency). The mechanisms involved are unclear, and it was suggested that EBN might reduce oxidative stress via upregulation of hepatic antioxidant genes and contribute to the downregulation of inflammatory cytokine genes such as CCL2 or IL-635. We did also observe a reduction in cytokine expression in isolated peritoneal macrophage from EBN-fed mice, suggesting attenuated systemic inflammation (Supplemental Fig. S7). Further studies, however, need to determine to what extend this anti-inflammatory effect is a direct or indirect result of the EBN feeding. There have also been reports that feeding very high levels of free Neu5Ac by gavage can attenuate HFD-induced hyperlipidemia and associated hypercoagulation38 and insulin resistance39, again in a rat model. Free Neu5Ac administration to HFD fed ApoE−/− mice also decreased aortic atherosclerotic plaque formation by 18.9%, and decreased the lipid deposition in liver hepatocytes by 26.7%. Also noted were a 62.6% reduction of triglyceride by improving lipoprotein lipase activity, 17.5% reduction of the plasma total cholesterol by up-regulating reverse cholesterol transport (RCT)-related protein expression such as ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABC) G1 and ABCG5 in liver or small intestine, and reducing oxidative stress by increasing antioxidant enzymes activity and protein expression of paraoxonase 140.

However, none of the above studies were done in a human-like CMAH-null background. Also, the in vivo kinetics of orally administered free sialic acids (rapid excretion in the urine)41–43 is markedly different from that of the glycosidically-bound Neu5Ac in EBN, and thus any mechanism of action is likely different. Additionally, feeding such high levels of free Neu5Ac could potentially cause dysbiosis involving micro-organisms found in the gut lumen which utilize Neu5Ac for their metabolism and growth44. What remains notable is our observation that intervention with EBN Neu5Ac after a short-term Neu5Gc regime almost completely attenuates atherosclerosis formation. This effect is especially remarkable as Ldlr-deficient mice on a high fat and high cholesterol diet for 12 weeks almost always robustly develop advanced atherosclerotic lesions. The observation underscores the therapeutic potential of dietary Neu5Ac development in treatment and possibly also regression of atherosclerosis in at risk CVD patients.

Recent work has highlighted that inhibition of the sialidase, neuraminidase 1 (Neu1), is associated with reduced atherogenesis in mice45. Potentially one can envision that elevated circulating Neu5Ac levels due to feeding can attenuate sialidase activity and hence reduce atherogenesis in our model. Such inhibition would also prevent the formation of atherogenic desialylated LDL46. However, free Neu5Ac is primarily found in the β-anomeric form and sialidases act on the α-anomer bound to glycans. Thus, increased free Neu5Ac in our studies should not inhibit Neu1 activity. In addition, Neu5Ac glycoproteins levels are very abundant in the serum (~2 mM) compared to the small amounts of dietary Neu5Ac glycoproteins from typical human diets (0.8–4 μmol Neu5Ac per gram diet). Moreover, Neu1 has no substrate preference between α2–3-linked and α2–6-linked Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc; the main linkages found on N-glycosylated proteins47. RNAseq analysis of Cmah−/− macrophage also did not report any differential Neu1 expression; even in the context of co-incubating macrophages with 2 mM Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc suggesting no preferential regulation or inhibition of NEU1 by either Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc48. Nevertheless, future studies will have to assess the importance of Neu1 activity in the observed Neu5Ac anti-atherogenic effect in humanized CMAH-deficient mice.

Weight for weight, EBN may now be among the most expensive animal products consumed by humans. This traditional Chinese “health food” has been claimed to have many medical benefits, and is recommended as a tonic for elderly people, pregnant women and growing children. However, none of these claims have been corroborated by controlled and blinded clinical studies. It is also necessary to validate the quality of the product, because analysis of EBN showed some possible allergens, such as mites, and microorganisms, contaminated especially in raw EBN49,50. Meanwhile, in addition to the increasing encroachment of humans on the birds’ habitat, pollution is now eroding some of the caves where they live and build their nests. Rising prices are also leading the “harvesters” of nests to become more aggressive, sometimes snatching nests as soon as they are built, or grabbing nests that have eggs in them31,51. With increasing demand there are also now reinforced concrete nesting houses established in urban areas near the sea, since the birds have a propensity to flock in such places.

If the claimed health benefits of EBN are indeed primarily due to the high content of Neu5Ac52, there are other far less expensive alternatives generated as byproducts of the poultry and dairy industry53–55 that should serve as suitable substitutes for EBN in general. Thus, one can suggest production of an “imitation EBN”, which could have much of the claimed health benefits of EBN without the high cost, nor the negative affect on the ecologically pressured bird species. These or other less expensive Neu5Ac-rich EBN substitutes may perhaps even help to protect these species from endangerment.

Finally, while doing these studies we noticed also that the simultaneous addition of a 5-fold excess of glycoprotein-bound Neu5Ac substantially blunted the xenosialitis effect of Neu5Gc. This is likely because the two molecules derived from the same meal are simultaneously entering cells at the same time and are in competition. This finding suggests that foods containing a substantial amount of Neu5Ac in great excess over Neu5Gc may not be associated with disease risk. This ratio may perhaps explain why most milk products are not associated with cancer risk. Of course, given the variation in expression of CMAH even within species and between tissue types, each food source must be directly assayed for this ratio.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement.

The use of mice in this project was approved by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) (Evaluation of the role of Glycans in Normal Physiology, Malignancies and Immune Responses, Protocol S01227). All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Program (ACP) and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), UCSD.

Mice and Cell Culture.

Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− mice were generated by crossing Cmah−/− mice56 and Ldlr−/− mice57 in a congenic C57BL/6N background and maintained in the University of California, San Diego vivarium according to Institutional Review Board guidelines. All animals were fully backcrossed and maintained on a 12-hour light cycle and fed ad libitum with water and standard rodent diet. Recommendations for atherosclerosis studies per the AHA statement were followed58, expect for HF diet composition to allow us to evaluate the impact of dietary sialic acid sources on atherogenesis. Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− and Cmah+/+Ldlr−/−mice were also maintained on a control soy-based (Sia-free) diet after weaning at 3 weeks. At 6 or 9 weeks of age male and female mice were placed on a Sia-free soy-based HFD with 20% anhydrous milkfat and 0.2% cholesterol; a Neu5Ac-rich soy-based HFD (containing 0.25 mg of Neu5Ac per gram of diet; made by adding edible bird’s nest (EBN) (Golden Nest, Inc) and a Neu5Gc-rich soy-based HFD (containing 0.25 mg of Neu5Gc per gram of diet; made by adding purified porcine submaxillary mucin (PSM) as described previously20. Five-fold Neu5Ac (1.25 mg of Neu5Ac per gram of diet) HFD and a premix of 5-fold Neu5Ac (1.25 mg of Neu5Ac per gram of diet) and regular amount of Neu5Gc (0.25 mg of Neu5Gc per gram of diet) HFD were also added to HFD course (Supplemental, Table. S1). The amount of Neu5Gc in PSM and Neu5Ac in EBN was determined by HPLC with Neu5Ac (Nacalai, USA) and Neu5Gc (Inalco, USA) standards and all diets were subsequently formulated and composed (Dyets, Inc. USA). A table detailing the contents of the various diets is also provided in the supplementary information. Peritoneal macrophages were collected by peritoneal lavage after 12 weeks HFD feeding without any stimulants20.

Foam cell formation.

Human macrophage-like THP-1 cells were cultivated in RPMI 1640 (GIBCO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Omega Scientific, USA), 10 mM HEPES buffer (GIBCO, USA), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (GIBCO, USA), 0.25% D-(+)-Glucose (Sigma, USA), and 0.05 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (MP, USA), plated in 24-well flat-bottom tissue culture plate at a cell density of 300.000 cells/cm2 and differentiated into macrophages using 50 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 72 hours. Cells were then washed and cultured with growth media added with 50 mg/ml aggregated LDL-cholesterol (Milipore, USA) and incubated for 24 hours with or without 2 mM free Neu5Ac or Neu5Gc feeding.

Neu5Gc Immunization.

Chimpanzee or human Red blood cell (RBC) membrane ghosts were prepared as described previously17. Six weeks old Cmah−/−Ldlr−/− male mice were immunized with pooled RBC membrane chimp ghosts, mixed with an equal volume of Freund’s adjuvant per week via intraperitoneal injection for 3 weeks (using complete adjuvant for week 1st, then incomplete adjuvant for the 2nd and 3rd weeks).

Serum Lipoprotein and Lipid Analysis.

Blood samples were obtained by mandibular plexus bleeding and cardiac puncture from mice fasted for 5 hrs. Serum lipoproteins in 100 μL pooled samples were separated by size exclusion chromatography using a polyethylene filter column (Sigma-Aldrich). Liver samples are homogenized in 250 mM sucrose buffer and the protein levels were measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cholesterol and triglyceride levels in separated lipoprotein fraction were measured by enzymatic kits (Sekisui, San Diego, CA, USA) as well as total cholesterol and triglyceride levels in serum and liver samples.

Quantification of Aortic Atherosclerosis.

Using stereomicroscopy dissection, the heart and ascending aorta of each animal was dissected, all the way down to the iliac bifurcation. The aortas were then opened along the long axis, pinned flat and stained for lipids using Sudan IV stain. Serial 10 μm cryo-sections of the aortic sinus were stained with Masson’s trichrome to measure area under the curve as well as mean lesion sizes of each of the atherosclerosis plaques, and also to assess the area comprising the necrotic core20 Each parameter was calculated using Image J, in a blinded manner, by K.K. and C.D.

Quantification of Inflammatory Cytokine Gene Expression.

Cells were collected after completion feeding regimen and mRNA was collected using a purification kit and converted into cDNA (Qiagen, Inc.). Expression of each cytokine gene (Supplemental, Table. S2) was measured using Cyber Green systems (Qiagen, Inc.).

HPLC quantification of sialic acid content by DMB.

The ethanol fraction from the macrophage LDL uptake assay was incubated at −80 °C for >3h, then lyophilized with a Labconco FreeZone Plus 4.5L Cascade Benchtop Freeze Dry System (cat # 7386030). Samples were acid-hydrolyzed with glacial acetic acid (2M final in total volume 200μL) for 3h at 80 °C to remove terminal sialic acids. Samples were spin-filtered (Millipore Sigma Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Unit; cat # UFC5010BK) to remove cellular debris. Free sialic acids were then derivatized with DMB as described previously59. Sialic acids were quantified with HPLC-fluorometry on a Phenomenex C-18 column using isocratic elution in 85% water, 7% methanol, and 8% acetonitrile.

Immunohistochemistry.

All aorta tissue samples were fixed and processed for paraffin sections and were stained with routine Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E), Masson’s trichrome, or serial cross sections of the aortic sinus were used for immunohistochemistry using the macrophage marker anti-CD68 (Abcam) with nuclei being counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Stained samples were photographed using the Keyence BZ −9000 and the digital photomicrographs were analyzed using Image J software.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 9, GraphPad Software). Data are presented as mean (SD) or standard error of the mean as indicated. Data have been analyzed for normality and equal variance using GraphPad software. When met this was a justification for using parametric analysis including Student’s t-test, One-Way ANOVA (>2 groups with one variable) and Two-Way ANOVA (more than one variable) with appropriate post hoc analyses as indicated in the figure legends. When these parameters were not met, we employed the equivalent non-parametric test and post hoc analyses including the Mann Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis test with uncorrected Dunn’s multiple comparisons. P-values are indicated by asterisk, where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, and NS = not significant.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Human-specific loss of sialic acid N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) production and associated anti-Neu5Gc-glycan antibody generation, interact against metabolically incorporated Neu5Gc-bearing glycans (enriched in red meat), inducing inflammatory “xenosialitis” and enhanced atherogenesis.

Interventional feeding with the Neu5Gc precursor N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) prevents the xenosialitis-mediated increase in atherogenesis.

Feeding Neu5Ac-rich mucins in a humanized atherosclerosis model has a strong intrinsic atheroprotective effects independent of xenosialitis

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH Grant R01GM32373 (to A.V.), an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 17POST33671176 (to K.K.), a JSPS KAKENHI Grant JP 19KK0216 (to K.K.), an NIH NHLBI grant F30 HL152666-01 (to J.K.C.), a Carlsberg Foundation Fellowship CF19-0702 (to K.V.G) and a Foundation Leducq grant 16CVD01 (to P.L.S.M.G.).

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no direct competing interests.

Contributor Information

Kunio Kawanishi, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Experimental Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba, Ibaraki, Japan.

Joanna K Coker, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Kaare V. Grunddal, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Chirag Dhar, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Jason Hsiao, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Karsten Zengler, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Bioengineering, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Center for Microbiome Innovation, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Nissi Varki, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Bioengineering, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Ajit Varki, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla; Center for Academic Research and Training in Anthropogeny, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

Philip L.S.M. Gordts, Glycobiology Research and Training Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla Department of Medicine, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kelm S, Schauer R. Sialic acids in molecular and cellular interactions. Int Rev Cytol. 1997;175:137–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearce OM, Laubli H. Sialic acids in cancer biology and immunity. Glycobiology. 2016;26:111–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schauer R, Kamerling JP. Exploration of the sialic acid world. Adv Carbohydr Chem Biochem. 2018;75:1–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schnaar RL, Gerardy-Schahn R, Hildebrandt H. Sialic acids in the brain: Gangliosides and polysialic acid in nervous system development, stability, disease, and regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2014;94:461–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varki A Glycan-based interactions involving vertebrate sialic-acid-recognizing proteins. Nature. 2007;446:1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis AL, Lewis WG. Host sialoglycans and bacterial sialidases: A mucosal perspective. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14:1174–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varki A Sialic acids in human health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:351–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Gunten S, Bochner BS. Basic and clinical immunology of siglecs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:61–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wasik BR, Barnard KN, Parrish CR. Effects of sialic acid modifications on virus binding and infection. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:991–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou JY, Oswald DM, Oliva KD, Kreisman LSC, Cobb BA. The glycoscience of immunity. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:523–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou HH, Hayakawa T, Diaz S, Krings M, Indriati E, Leakey M, Paabo S, Satta Y, Takahata N, Varki A. Inactivation of cmp-n-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase occurred prior to brain expansion during human evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11736–11741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peri S, Kulkarni A, Feyertag F, Berninsone PM, Alvarez-Ponce D. Phylogenetic distribution of cmp-neu5ac hydroxylase (cmah), the enzyme synthetizing the proinflammatory human xenoantigen neu5gc. Genome Biol Evol. 2018;10:207–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Springer SA, Gagneux P. Glycomics: Revealing the dynamic ecology and evolution of sugar molecules. J Proteomics. 2016;135:90–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amon R, Ben-Arye SL, Engler L, Yu H, Lim N, Berre LL, Harris KM, Ehlers MR, Gitelman SE, Chen X, Soulillou JP, Padler-Karavani V. Glycan microarray reveal induced iggs repertoire shift against a dietary carbohydrate in response to rabbit anti-human thymocyte therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:112236–112244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma F, Deng L, Secrest P, Shi L, Zhao J, Gagneux P. A mouse model for dietary xenosialitis: Antibodies to xenoglycan can reduce fertility. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:18222–18231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salama A, Evanno G, Harb J, Soulillou JP. Potential deleterious role of anti-neu5gc antibodies in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2015;22:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samraj AN, Bertrand KA, Luben R, et al. Polyclonal human antibodies against glycans bearing red meat-derived non-human sialic acid n-glycolylneuraminic acid are stable, reproducible, complex and vary between individuals: Total antibody levels are associated with colorectal cancer risk. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0197464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varki NM, Strobert E, Dick EJ Jr., Benirschke K, Varki A. Biomedical differences between human and nonhuman hominids: Potential roles for uniquely human aspects of sialic acid biology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:365–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samraj AN, Pearce OM, Laubli H, Crittenden AN, Bergfeld AK, Banda K, Gregg CJ, Bingman AE, Secrest P, Diaz SL, Varki NM, Varki A. A red meat-derived glycan promotes inflammation and cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:542–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawanishi K, Dhar C, Do R, Varki N, Gordts P, Varki A. Human species-specific loss of cmp-n-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase enhances atherosclerosis via intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:16036–16045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alisson-Silva F, Kawanishi K, Varki A. Human risk of diseases associated with red meat intake: Analysis of current theories and proposed role for metabolic incorporation of a non-human sialic acid. Mol Aspects Med. 2016;51:16–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhar C, Sasmal A, Varki A. From “serum sickness” to “xenosialitis”: Past, present, and future significance of the non-human sialic acid neu5gc. Front Immunol. 2019;10:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabas I, Garcia-Cardena G, Owens GK. Recent insights into the cellular biology of atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2015;209:13–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: Challenges and opportunities. Science. 2013;339:166–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:104–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kathan RH, Weeks DI. Structure studies of collocalia mucoid. I. Carbohydrate and amino acid composition. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969;134:572–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcone MF. Characterization of the edible bird’s nest the “caviar of the east”. ood Research International (Ottawa, Ont.). 2005;38:1125–1134 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norhayati MKA O; Wan Mohamud WN Preliminary study of the nutritional content of malaysian edible bird’s nest. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. 2010;16:389–396 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varki A, Schnaar RL, Schauer R. Sialic acids and other nonulosonic acids. In: rd, Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Stanley P, Hart GW, Aebi M, Darvill AG, Kinoshita T, Packer NH, Prestegard JH, Schnaar RL, Seeberger PH, eds. Essentials of glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor (NY); 2015:179–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zaramela LS, Martino C, Alisson-Silva F, et al. Gut bacteria responding to dietary change encode sialidases that exhibit preference for red meat-associated carbohydrates. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:2082–2089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koon LC. Features – bird’s nest soup – market demand for this expensive gastronomic delicacy threatens the aptly named edible-nest swiflets with extinction in the east. Wildlife Conservation. 2000;103:30–35 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sodhi NSK BH Conservation meets consumption. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 2000;15 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorburn CC. The edible nest swiftlet industry in southeast asia: Capitalism meets commensalism. Human Ecology 43:179–184 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bardor M, Nguyen DH, Diaz S, Varki A. Mechanism of uptake and incorporation of the non-human sialic acid n-glycolylneuraminic acid into human cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4228–4237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yida Z, Imam MU, Ismail M, Hou Z, Abdullah MA, Ideris A, Ismail N. Edible bird’s nest attenuates high fat diet-induced oxidative stress and inflammation via regulation of hepatic antioxidant and inflammatory genes. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou Z, Imam MU, Ismail M, Ooi DJ, Ideris A, Mahmud R. Nutrigenomic effects of edible bird’s nest on insulin signaling in ovariectomized rats. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:4115–4125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yida Z, Imam MU, Ismail M, Ooi DJ, Sarega N, Azmi NH, Ismail N, Chan KW, Hou Z, Yusuf NB. Edible bird’s nest prevents high fat diet-induced insulin resistance in rats. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:760535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yida Z, Imam MU, Ismail M, Wong W, Abdullah MA, Ideris A, Ismail N. N-acetylneuraminic acid attenuates hypercoagulation on high fat diet-induced hyperlipidemic rats. Food Nutr Res. 2015;59:29046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yida Z, Imam MU, Ismail M, Ismail N, Azmi NH, Wong W, Altine Adamu H, Md Zamri ND, Ideris A, Abdullah MA. N-acetylneuraminic acid supplementation prevents high fat diet-induced insulin resistance in rats through transcriptional and nontranscriptional mechanisms. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:602313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo S, Tian H, Dong R, Yang N, Zhang Y, Yao S, Li Y, Zhou Y, Si Y, Qin S. Exogenous supplement of n-acetylneuraminic acid ameliorates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:183–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nohle U, Beau JM, Schauer R. Uptake, metabolism and excretion of orally and intravenously administered, double-labeled n-glycoloylneuraminic acid and single-labeled 2-deoxy-2,3-dehydro-n-acetylneuraminic acid in mouse and rat. Eur J Biochem. 1982;126:543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nohle U, Schauer R. Metabolism of sialic acids from exogenously administered sialyllactose and mucin in mouse and rat. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1984;365:1457–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tangvoranuntakul P, Gagneux P, Diaz S, Bardor M, Varki N, Varki A, Muchmore E. Human uptake and incorporation of an immunogenic nonhuman dietary sialic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12045–12050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang YL, Chassard C, Hausmann M, von Itzstein M, Hennet T. Sialic acid catabolism drives intestinal inflammation and microbial dysbiosis in mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White EJ, Gyulay G, Lhotak S, Szewczyk MM, Chong T, Fuller MT, Dadoo O, Fox-Robichaud AE, Austin RC, Trigatti BL, Igdoura SA. Sialidase downregulation reduces non-hdl cholesterol, inhibits leukocyte transmigration, and attenuates atherosclerosis in apoe knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:14689–14706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Summerhill VI, Grechko AV, Yet SF, Sobenin IA, Orekhov AN. The atherogenic role of circulating modified lipids in atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davies LR, Pearce OM, Tessier MB, Assar S, Smutova V, Pajunen M, Sumida M, Sato C, Kitajima K, Finne J, Gagneux P, Pshezhetsky A, Woods R, Varki A. Metabolism of vertebrate amino sugars with n-glycolyl groups: Resistance of alpha2–8-linked n-glycolylneuraminic acid to enzymatic cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28917–28931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okerblom JJ, Schwarz F, Olson J, Fletes W, Ali SR, Martin PT, Glass CK, Nizet V, Varki A. Loss of cmah during human evolution primed the monocyte-macrophage lineage toward a more inflammatory and phagocytic state. J Immunol. 2017;198:2366–2373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen JX, Wong SF, Lim PK, Mak JW. Culture and molecular identification of fungal contaminants in edible bird nests. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess. 2015;32:2138–2147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kew PE, Wong SF, Lim PK, Mak JW. Structural analysis of raw and commercial farm edible bird nests. Trop Biomed. 2014;31:63–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee TH, Wani WA, Koay YS, Kavita S, Tan ETT, Shreaz S. Recent advances in the identification and authentication methods of edible bird’s nest. Food Res Int. 2017;100:14–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mahaq O, MA PR, Jaoi Edward M, Mohd Hanafi N, Abdul Aziz S, Abu Hassim H, Mohd Noor MH, Ahmad H. The effects of dietary edible bird nest supplementation on learning and memory functions of multigenerational mice. Brain Behav. 2020:e01817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juneja LR, Koketsu M, Nishimoto K, Kim M, Yamamoto T, Itoh T. Large-scale preparation of sialic acid from chalaza and egg-yolk membrane. Carbohydr Res. 1991;214:179–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakano T, Ozimek L. A sialic acid assay in isolation and purification of bovine k-casein glycomacropeptide: A review. Recent Pat Food Nutr Agric. 2014;6:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang B, Yu B, Karim M, Hu H, Sun Y, McGreevy P, Petocz P, Held S, Brand-Miller J. Dietary sialic acid supplementation improves learning and memory in piglets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:561–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hedlund M, Tangvoranuntakul P, Takematsu H, Long JM, Housley GD, Kozutsumi Y, Suzuki A, Wynshaw-Boris A, Ryan AF, Gallo RL, Varki N, Varki A. N-glycolylneuraminic acid deficiency in mice: Implications for human biology and evolution. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4340–4346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ishibashi S, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, Gerard RD, Hammer RE, Herz J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:883–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen M, Falk E, Fisher EA, Garcia-Cardena G, Lusis AJ, Owens AP 3rd, Rosenfeld ME, Virmani R, American Heart Association Council on Arteriosclerosis T, Vascular B, Council on Basic Cardiovascular S. Recommendation on design, execution, and reporting of animal atherosclerosis studies: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37:e131–e157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Manzi AE, Diaz S, Varki A. High-pressure liquid chromatography of sialic acids on a pellicular resin anion-exchange column with pulsed amperometric detection: A comparison with six other systems. Anal Biochem. 1990;188:20–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.