Highlights

-

•

Conventional and unusual sources of starch can be modified by ultrasound processing.

-

•

Enthalpy value of both ultrasounds treated corn and cassava decreased.

-

•

XRD result revealed that increase in ultrasound time could slightly change the evaluation pattern.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Starch molecules, Structural properties, Corn & cassava

Abstract

In this study, the starch molecules were modified with ultrasonication at two different time intervals by using starch molecules from corn and cassava. This research aimed to examine the effect of the high power ultrasound of 40 kHz voltage and frequency with short time duration on structural and physical properties of corn and cassava starch. Morphology of ultrasonically treated starch granules was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), FTIR, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) and compared with untreated samples. After the ultrasound treatment groove and notch appeared on the surface of the starch granules. The results showed that gelatinization temperature did not change with ultrasound treatments, but enthalpy value decreased from 13.15 ± 0.25 J/g to 11.5 ± 0.29 J/g and 12.65 ± 0.32 J/g to 10.32 ± 0.26 J/g for sonicated corn and cassava starches, respectively. The XRD results revealed a slight decreased in the crystallinity degree (CD) of sonicated corn (25.3,25.1) and cassava starch (21.0,21.4) as compared to native corn (25.6%) and cassava starch (22.2%). This study suggests that non-thermal processing techniques have the potential to modify the starch from different sources and their applications due to starch’s versatility, low cost, and comfort of use after processing with altered physicochemical properties.

1. Introduction

Starch is a complex polysaccharide that abundantly exists in numerous plants, tubers, and roots. However, starch is a mixture of two polymer chains such as amylose (alpha 1–4 linkages) and amylopectin (both alpha 1–4 linkages and alpha 1–6 linkages). Starch consists of 10 to 30% of amylose and 70–90% of amylopectin which varies from variety to variety. Currently, the modified starches are used in many food industries to improve their technological values. Because of the native form, starch is unsuitable for many industrial applications. So, that the various chemical and physical methods have been applied to modify the native starch and such modification endorse the disorganization of molecules, degradation of the polymer, rearrangement of molecules, crosslinking of polymers and chemical groups [1], [2]. Additionally, these modifications help to improve diverse issues such as solubility, retrogradation and syneresis, shear stress resistance, and thermal disintegration.

But it is still a matter of concern to use safe and environmentally friendly technologies to modify the native starch. Chemical modifications of starch include the insertion of new functional groups such as carboxyl, acetyl, hydroxypropyl, amine, amide, or any other to the starch polymer which can leave toxic residues in the products and is considered as the non-environmentally friendly procedure [3]. Further, different physical methods such as extrusion, hydrothermal treatment, microwave, and radiation have been used to modify the starch [4], [5]. Although, these thermal technologies have many drawbacks such as it causes higher degradation of starch, resulting products were characterized by a higher degree of oxidation (high content of-CHO and –COOH groups) and spectrum of possibilities of application [6].

Ultrasonication is a novel processing technology that can cause the physical depolymerization of starch. The effects of sonication treatment cause acoustic cavitation which is the formation and collapsing of bubbles in liquid irradiated by heat and pressure just in a short time [7], [8], [9], [10]. During sonication treatment, ultrasound energy is transferred through a cavitation process which refers to the formation of the cavities with gas or vapor as the pressure decreases and rapid collapse of microbubbles occurs due to immense pressure [11], [12], [13], [14]. Ultrasonication is useful in modifying the physicochemical and functional properties of starch which has many advantages in terms of higher selectivity and quality, less chemical usage, and short processing duration [3], [15].

This study aimed to analyze the effect of high-power ultrasound treatment on the physical, chemical, and functional properties of cassava and corn starch with short time durations. Further, to investigate the impact of ultrasonication on starch molecules originated from different sources could show discontinuous morphology after processing at identical parameters. As a result, this study aims to provide novel functionalities of ultrasound processed flour in the preparation of tailor-made corn and cassava starch foods.

2. Materials and methods

The corn starch was acquired from Hengrui Starch Company (Luohe, China) with a moisture content of 13.5 ± 0.1% and cassava starch with 17% amylose from Huanglong Food Industry Co., Ltd. China; ii) and were stored at room temperature.

2.1. Ultrasound treatment

The ultrasonic treatment of cassava and corn starch granules was performed by the ultrasonic cleaner (Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co., LTD.). In brief, 20% of cassava and corn starch granules were mixed in distilled water in a beaker. The treatment was performed for 10 and 20 min with 40 kHz and 99% frequency at 26 ± 2 °C. This suitable treatment time was chosen based on previous studies [16]. After the treatment, the solutions were dried using a hot air oven at 40 °C for overnight and stored for further analysis. The name of the sample was given as cassava (CA) zero minutes (CA 0) for untreated starch, (CA 10) and (CA 20) for treated. Similarly, the corn starch (CR 0) for untreated and (CR 10) and (CR 20) minutes for treated starch granules. This suitable parameters was selected based on a previous studies [16].

2.2. X-ray diffraction (XRD)

X-ray diffraction was achieved by D8 ADVANCE X ray diffractometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). In brief, the experiment was performed at 40 kV and current 30 mA, with Cu‐ Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). The was recorded with angular range was from 10° − 50° for 2θ with a scanning rate of 0.02/min. the relative crystallinity of ultrasound-treated starch molecules was calculated by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where Ac, Aa represents the crystalline is and amorphous area respectively on the X-ray diffractograms.

2.3. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The functional groups of ultrasonic-based modified starch molecules were measured by Bruker Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optics, Germany). In brief, the starch granules were blended with KBr to abolish sprinkling properties in bulky crystals. Further, to remove the moisture completely, the ultrasound modified starch was dried in a muffle oven at 50 °C for 24 h. Furthermore, the samples were obtained after grinding with a ratio of 5:100 mg (KBr: Starch). The spectrums of samples were recorded at 4 cm−1 and 32 scans with a wavelength of 400 to 4000 cm−1.

2.4. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal properties of starch samples were studied by DSC (NETZSCH DSC 214 Polyma DSC21400A-0318-L, Germany). In brief, the 5 mg ultrasound treated cassava and corn starch were placed in the aluminum pans and the samples were mixed with 20 µl of Milli Q water. Further, the sample specimens were sealed and left for 6 h, and analysis was done at the temperature of 5100 °C at the rate of 10 °C/min. Characteristic temperatures of transitions were defined as To (onset), Tp (peak of gelatinization), Tc (conclusion), and enthalpy of gelatinization (ΔH) was recorded.

2.5. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The structure of ultrasound-treated cassava and corn starch molecules was analyzed by SEM (Phenom Worid BV, Phenom Pro, MVE064606-60020-S). The starch granules were fixed on an aluminum specimen holder with conductive adhesive and coated with gold for transmission of electron aggregate on SEM (Quorum, Q 150R S, plus) probe at measured and sputter current 20 mA respectively. Further, the surface morphology of starch granules was analyzed at 15 kV and 5000 mag.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All test was done in multiplicities form and the data were shown as mean values ± standard deviation. Statistical measurement was performed by (ANOVA) using SPSS software (22.0 version, IBM).

3. Result and discussion

3.1. Impact of ultrasonication on functional groups of molecules by FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectra of starches presented bands associated with stretching, flexion, and deformation corresponding to the main functional groups’ characteristics of the polymer starch (Fig. 1). For treated samples with ultrasound technique for 10 and 20 min, FTIR spectra have revealed that positions of the characteristic absorption peaks have changed after ultrasound treatment, and minor reduction was noticed in their intensities. Similar findings were reported by [16] during the ultrasound treatment of cassava starch granules. As shown in the figure the broadband appeared at around 3400 cm−1 resembles the –OH of amylose and amylopectin [17] and ultrasound treatment reduced the intensity of this band, implying that the starch microstructure's capacity to hold bound water was disturbed. These results were consistent with the previously reported study of [18]. The peak observed at around 2900 cm−1 which is corresponded to the vibration of the C–H bond. The absorbance peak at around 1644 cm−1 corresponds to scissoring vibration O–H bonds. FTIR spectra of the starch caused structural changes on a molecular level [16]. In previously reported studies, conformational changes in polymers have been observed in the spectra associated with the band at the range of 900–1300 cm−1 [19], [20]. Moreover, the peak located at 1163 cm−1 was assigned to the vibration of the C-O bonds, while the peak at 1080 cm−1 was attributed to the ordered structure of the starch. The band in the spectra of both cassava and corn starches at around 928 and 764 cm−1 were associated with the skeletal model of α (1 → 4) glycosidic linkage and the skeletal modes of the C–C stretch [17], [21].

Fig. 1.

FT-IR spectra of native and ultrasound treated corn and cassava starch sonicated for 10 and 20 min (A) CR: Corn Starch (B) Cassava Starch.

The IR spectra were used to determine the absorbance at the three wavenumbers, and the ratio of absorbance 1022/995 cm1 was calculated and given in Table 1. The ratio of absorbance 1022/995 cm1 increased in both sonicated cassava and corn starch samples, demonstrating a greater percentage of amorphous to organized structural zones in the starch granules.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of sonicated corn and cassava starches.

| 1Samples | 2To | Tp | Tc | ΔH | IR ratio of 1022/995 cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR-0 | 71.58 ± 0.21a | 77.01 ± 0.15a | 87.9 ± 0.10a | 13.15 ± 0.25a | 0.16c |

| CR-10 | 71.5 ± 0.14a | 76.66 ± 0.22b | 85.13 ± 0.25c | 8.13 ± 0.22e | 0.17c |

| CR-20 | 71.98 ± 0.26a | 77.72 ± 0.18a | 87.99 ± 0.15a | 11.5 ± 0.29c | 0.17c |

| CA-0 | 66.8 ± 0.17b | 74.31 ± 0.21c | 86.77 ± 0.26b | 12.65 ± 0.32b | 0.25b |

| CA-10 | 66.15 ± 0.13b | 73.50 ± 0.15d | 85.6 ± 0.17c | 8.86 ± 0.14e | 0.45a |

| CA-20 | 66.35 ± 0.22b | 74.12 ± 0.17c | 84.55 ± 0.25d | 10.32 ± 0.26d | 0.25b |

CR-0, Untreated Corn starch; CR-10, Corn starch sonicated for 10 min; CR-20, Corn starch sonicated for 20 min; CA-0, Untreated Cassava Starch; CA-10, Corn starch sonicated for 10 min; CR-20, Corn starch sonicated for 20 min.

To, onset temperature; Tp, peak temperature; Tc, conclusion temperature; ΔH, enthalpy change.

3.2. Effect of ultrasonic on thermal properties

The thermal properties of native and sonicated corn and cassava starches are shown in Table 1. Native corn starch had higher To (71.58 °C), Tp (77.01 °C), and Tc (87.9 °C), while native cassava starch had lower To (66.8 °C), Tp (74.31 °C) and Tc (86.77 °C). It may be due to the higher degree of crystallinity of corn starch as compared to cassava starch and provides more thermal stability of granules against gelatinization. The higher gelatinization temperature of corn starch was due to a higher degree of crystallinity. The chain length distribution of amylopectin also showed an impact on crystallinity [22], [23]. Sonication treatment had barely affected the gelatinization temperature of both corn and cassava starch as compared to their native counterparts. These results agreed with previously reported studies of [16], [24], who stated a slight change in gelatinization temperatures of starch granules. In DSC tests, sonicated corn and cassava starch samples had a lower enthalpy of gelatinization than the control samples, which was statistically significant. Table 1 showed that the enthalpy value of both corn and cassava starch was lower than that of their native starches after 10 mins of sonication, which showed that treatment causes a structural disparity in the crystalline area of the granules led by the hydration of the amorphous regions [16], [24], [25]. Moreover, another study described that cracks and pores on the surface of the starch made it easier for water to penetrate the granules and disrupted the crystalline regions of the starch [26], [27]. As compared to the amorphous region, the crystalline region of starch is less affected by ultrasound [28], [29]. Enthalpy values results indicate that the organization of the starch constituents plays a vital role in the gelatinization process of starches modified by ultrasound treatment. However, the enthalpy value of both corn and cassava starch increased after treatment for 20 min. This was due to more energy required to break intermolecular bonds in starch molecules [29].

3.3. Effect of ultrasonic treatment crystalline structures of starch particles

The crystallinity of granule starch was measured by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The X-ray diffraction of native and samples sonicated at different times are presented in Fig. 2. Native cassava and corn starch exhibited typical A-type crystalline pattern approximately = 15°, 17°, 18°, and 23°, which was like previously reported studies [30], [31]. The sonication at different time intervals slightly changed the evaluation pattern as compared to the control samples, indicating that the crystalline structure almost remained the same with the treatment. Similar trends were reported in previous studies [16], [32], [33]. Only a slight reduction was observed in the peak intensities of treated and untreated samples. The results of XRD are consistent with results obtained by DSC and FTIR spectra (Table 1 and Fig. 1). According to a previous study, the amorphous region of starch was more prone to get destroyed as compared to the crystalline region during the ultrasonication treatment [27], [25]. The degree of crystallinity of (CD) of native and sonicated corn and cassava starches are shown in the Table inset in Fig. 2A & 2B. The relative crystallinity of native corn starch was (25.6%), which was higher than that of native cassava starch (22.2%). After sonication, both corn and cassava starches showed a decrease in relative crystallinity. The instability of the layered structure of starch may be responsible for the reduction in relative crystallinity of ultrasound-treated samples.

Fig. 2.

X-ray Diffraction pattern of native and ultrasound treated cassava and corn starch sonicated for 10 and 20 min (A) CR: Corn Starch (B) Cassava Starch.

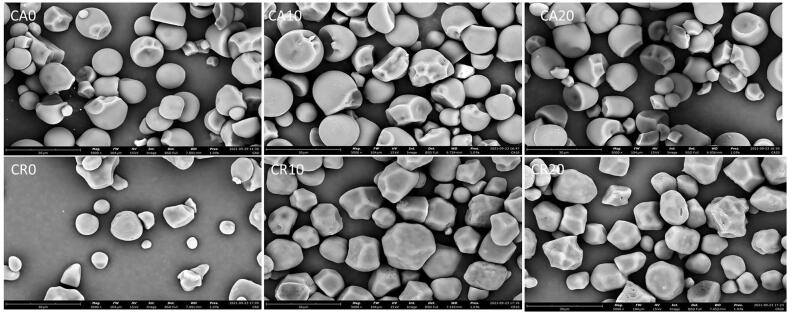

3.4. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of starch particles

Different chemical, enzymatic and physical processes can induce structural modifications in starch, which can be detected through microscopic analysis [34]. The microstructure of untreated and ultrasonically treated starch samples of both corn and cassava was observed by SEM. The surface and shape characteristics of starch samples are shown in Fig. 3. The shape of untreated cassava granules (CA, 0 min) was rounded, oval, or oval-truncated, while for untreated corn granules (CR, 0 min) the surface was slick and compact having a solid ball and polygon morphology. Moreover, for both untreated starch samples, SEM analysis showed a smooth granule surface without having cracks. Generally, the size of starch granules was not affected by the ultrasonic treatment, but roughness on the surface of the granules was noticed which increased with treatment time. Similar findings were described by [35]. The groove and notch appeared on the surfaces of starch granules after treating with ultrasound technique for 10 min and 20 min. The mentioned structural changes can be induced due to the presence of frictional/shear force produced by shock waves and due to the formation of localized hot spots through bubble collapsing and cavitation leading to high pressure gradients in the surrounding area [36], [37], [38]. The formation of frictional or shear force is enough to degrade the polymers demonstrating the depressions and small fissures on the surface of the granules [27], [35], [39]. Moreover, the surface of the ultrasound-treated starch is partially gelatinized due to an increase in temperature during ultrasound treatment [27], [40]. Conversely, no reduction was observed in the size of both native and ultrasound cassava and corn starches. SEM results suggesting that a marked change was observed on the surface of both ultrasounds treated cassava and corn starches, but their granules size remains unaffected.

Fig. 3.

Effect of ultrasound treatments on the structure of corn and cassava starch molecules.

3.5. Conclusion

Ultrasound processing of cassava and corn starch has resulted in structural disorganization followed by significant changes in their physicochemical properties. The degrees of modifications in molecular structure and physical properties persuaded by ultrasound varied between starch types. XRD results showed a slight decrease in the intensity of the crystallization peak. SEM micrographs showed a slight change on the surface of both ultrasounds treated cassava and corn starch. Enthalpy values were reduced after sonication, the maximum reduction in enthalpy value was observed in both cassava and corn starch after 10 mins of sonication as compared to 20 mins of sonication. It was observed that the promising use of ultrasonication to modify the starch molecules is in the fact that starch molecules could be altered by cavitation forces. However, the temperature of the medium slightly increased during treatment but less than the conventional processing methods. The ultrasonication treatment prompted the degradation of native starch which can attribute to the violent shear force confronted with starch molecules in the shear valve. The DSC analysis showed a decrease in the enthalpy of gelatinization. The microstructure revealed that the ultrasound treatment had an obvious effect on the structure and size of starch molecules. Various investigations have been done to analyze the positive and negative impacts of ultrasonic treatment. But still need to optimize the ultrasonic processing parameters such as frequency, power, temperature, time, and others on a specific food item to surly claim their degradation impact. The results showed that ultrasound can be an eco-friendly technique, which allows structural and physical modifications of cassava and corn starch for food applications of different potential.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abdul Rahaman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ankita Kumari: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Xin-An Zeng: Data curation, Funding acquisition. Muhammad Adil Farooq: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rabia Siddique: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ibrahim Khalifa: Resources, Visualization, Data curation, Software. Azhari Siddeeg: Resources, Visualization, Data curation, Software. Maratab Ali: Resources, Visualization, Data curation, Software. Muhammad Faisal Manzoor: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21576099) the S&T projects of Guangdong Province (2017B020207001 and 2015A030312001), as well as the 111 Project (B17018).

Contributor Information

Xin-An Zeng, Email: xazeng@scut.edu.cn.

Muhammad Faisal Manzoor, Email: faisaluos26@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Singh J., Kaur L., McCarthy O.J. Factors influencing the physico-chemical, morphological, thermal and rheological properties of some chemically modified starches for food applications-A review. Food Hydrocolloids. 2007;21:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fonseca L.M., Gonçalves J.R., El Halal S.L.M., Pinto V.Z., Dias A.R.G., Jacques A.C., Zavareze E.D.R. Oxidation of potato starch with different sodium hypochlorite concentrations and its effect on biodegradable films. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2015;60:714–720. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amini A.M., Razavi S.M.A., Mortazavi S.A. Morphological, physicochemical, and viscoelastic properties of sonicated corn starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015;122:282–292. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo Z.-G., Fu X., He X.-W., Luo F.-X., Tu Y.-J. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on rheological properties of waxy maize starch paste. Polym. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2008;10 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng J., Li Q., Hu A., Yang L., Lu J., Zhang X., Lin Q. Dual-frequency ultrasound effect on structure and properties of sweet potato starch. Starch/Staerke. 2013;65:621–627. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewicka K., Siemion P., Kurcok P. Chemical modifications of starch: microwave effect. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015;2015 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mallakpour S., L. khodadadzadeh Ultrasonic-assisted fabrication of starch/MWCNT-glucose nanocomposites for drug delivery. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;40:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzoor M.F., Ahmad N., Ahmed Z., Siddique R., Mehmood A., Usman M., Zeng X.A. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge plasma, ultra‐sonication, and thermal processing on the rheological and functional properties of sugarcane juice. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:3823–3832. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manzoor M.F., Ahmed Z., Ahmad N., Aadil R.M., Rahaman A., Roobab U., Rehman A., Siddique R., Zeng X.A., Siddeeg A. Novel processing techniques and spinach juice: quality and safety improvements. J. Food Sci. 2020;85:1018–1026. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.15107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzoor M.F., Zeng X.-A., Rahaman A., Siddeeg A., Aadil R.M., Ahmed Z., Li J., Niu D. Combined impact of pulsed electric field and ultrasound on bioactive compounds and FT-IR analysis of almond extract. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019;56:2355–2364. doi: 10.1007/s13197-019-03627-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H.Y., Han J.A., Kweon D.K., Park J.D., Lim S.T. Effect of ultrasonic treatments on nanoparticle preparation of acid-hydrolyzed waxy maize starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013;93:582–588. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manzoor Muhammad Faisal, Siddique Rabia, Hussain Abid, Ahmad Nazir, Rehman Abdur, Siddeeg Azhari, Alfarga Ammar, Alshammari Ghedeir M., Yahya Mohammed A. Thermosonication effect on bioactive compounds, enzymes activity, particle size, microbial load, and sensory properties of almond (Prunus dulcis) milk. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;78:105705. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manzoor M.F., Xu B., Khan S., Shukat R., Ahmad N., Imran M., Rehman A., Karrar E., Aadil R.M., Korma S.A. Impact of high-intensity thermosonication treatment on spinach juice: Bioactive compounds, rheological, microbial, and enzymatic activities. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021:105740. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faisal Manzoor Muhammad, Ahmed Zahoor, Ahmad Nazir, Karrar Emad, Rehman Abdur, Muhammad Aadil Rana, Al‐Farga Ammar, Waheed Iqbal Muhammad, Rahaman Abdul, Zeng Xin‐An. Probing the combined impact of pulsed electric field and ultra-sonication on the quality of spinach juice. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021;45(5) doi: 10.1111/jfpp.v45.510.1111/jfpp.15475. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satmalawati E.M., Pranoto Y., Marseno D.W., Marsono Y. The physicochemical characteristics of cassava starch modified by ultrasonication. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021;980 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monroy Y., Rivero S., García M.A. Microstructural and techno-functional properties of cassava starch modified by ultrasound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:795–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otálora M.C., Wilches-Torres A., Gómez Castaño J.A. Preparation and physicochemical properties of edible films from gelatin and Andean potato (Solanum tuberosum Group Phureja) starch. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021;56:838–846. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui R., Zhu F. Effect of ultrasound on structural and physicochemical properties of sweetpotato and wheat flours. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;66 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Shujun, Li Caili, Copeland Les, Niu Qing, Wang Shuo. Starch retrogradation: a comprehensive review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2015;14(5):568–585. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan W., Li Q., Wang H., Liu Y., Zhang J., Dong F., Guo Z. Synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial property of novel starch derivatives with 1, 2, 3-triazole. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016;142:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dankar I., Haddarah A., Omar F.E., Pujolà M., Sepulcre F. Characterization of food additive-potato starch complexes by FTIR and X-ray diffraction. Food Chem. 2018;260:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh N., Singh J., Kaur L., Singh Sodhi N., Singh Gill B. Morphological, thermal and rheological properties of starches from different botanical sources. Food Chem. 2003;81:219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh S., Singh N., Isono N., Noda T. Relationship of granule size distribution and amylopectin structure with pasting, thermal, and retrogradation properties in wheat starch. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2010;58:1180–1188. doi: 10.1021/jf902753f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jambrak A.R., Herceg Z., Šubarić D., Babić J., Brnčić M., Brnčić S.R., Bosiljkov T., Čvek D., Tripalo B., Gelo J. Ultrasound effect on physical properties of corn starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;79:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Z., Fu X., He X., Luo F., Gao Q., Yu S. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the physicochemical properties of maize starches differing in amylose content. Starch – Stärke. 2008;60:646–653. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sujka M. Ultrasonic modification of starch–Impact on granules porosity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;37:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang W., Kong X., Zheng Y., Sun W., Chen S., Liu D., Zhang H., Fang H., Tian J., Ye X. Controlled ultrasound treatments modify the morphology and physical properties of rice starch rather than the fine structure. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;59 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zuo Y.Y.J., Hébraud P., Hemar Y., Ashokkumar M. Quantification of high-power ultrasound induced damage on potato starch granules using light microscopy. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2012;19:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu A., Li Y., Zheng J. Dual-frequency ultrasonic effect on the structure and properties of starch with different size. LWT. 2019;106:254–262. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan X., Gu B., Li X., Xie C., Chen L., Zhang B. Effect of growth period on the multi-scale structure and physicochemical properties of cassava starch. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;101:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X., Wang H., Song J., Zhang Y., Zhang H. Understanding the structural characteristics, pasting and rheological behaviours of pregelatinised cassava starch. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018;53:2173–2180. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmona-García R., Bello-Pérez L.A., Aguirre-Cruz A., Aparicio-Saguilán A., Hernández-Torres J., Alvarez-Ramirez J. Effect of ultrasonic treatment on the morphological, physicochemical, functional, and rheological properties of starches with different granule size. Starch – Stärke. 2016;68:972–979. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Falsafi S.R., Maghsoudlou Y., Rostamabadi H., Rostamabadi M.M., Hamedi H., Hosseini S.M.H. Preparation of physically modified oat starch with different sonication treatments. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;89:311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 34.L. Sívoli, E. Pérez, P. Rodríguez, Análisis estructural del almidón nativo de yuca (Manihot esculenta C.) empleando técnicas morfométricas, químicas, térmicas y reológicas Structural analysis of the cassava native starch (Manihot esculenta C.) using morphometric, chemical, thermal and rheological techniques, in, 2012.

- 35.Sujka M., Jamroz J. Ultrasound-treated starch: SEM and TEM imaging, and functional behaviour. Food Hydrocolloids. 2013;31:413–419. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Z., Lin X., Li P., Zhang J., Wang S., Ma H. Effects of low intensity ultrasound on cellulase pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;117:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nie H., Li C., Liu P.-H., Lei C.-Y., Li J.-B. Retrogradation, gel texture properties, intrinsic viscosity and degradation mechanism of potato starch paste under ultrasonic irradiation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;95:590–600. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilet A., Quettier C., Wiatz V., Bricout H., Ferreira M., Rousseau C., Monflier E., Tilloy S. Unconventional media and technologies for starch etherification and esterification. Green Chem. 2018;20:1152–1168. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herceg Z., Batur V., Jambrak A.R., Badanjak M., Brnčić S.R., Lalas V. Modification of rheological, thermophysical, textural and some physical properties of corn starch by tribomechanical treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010;80:1072–1077. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu S., Zhang Y., Ge Y., Zhang Y., Sun T., Jiao Y., Zheng X.Q. Effects of ultrasound processing on the thermal and retrogradation properties of nonwaxy rice starch. J. Food Process Eng. 2013;36:793–802. [Google Scholar]