Abstract

Group parenting programs based on cognitive-behavioral and social learning principles are effective in improving child behavior problems and positive parenting. However, most programs target non-Hispanic, White, English-speaking families and are largely inaccessible to a growing Hispanic and non-White population in the US. We sought to examine the extent to which researchers have culturally adapted group parenting programs by conducting a systematic review of the literature. We identified 41 articles on 23 distinct culturally adapted programs. Most cultural adaptations focused on language translation and staffing, with less focus on modification of concepts and methods, and on optimizing the fit between the target cultural group and the program goals. Only one of the adapted programs engaged a framework to systematically record and publish the adaptation process. Fewer than half of the culturally adapted programs were rigorously evaluated. Additional investment in cultural adaptation and subsequent evaluation of parenting programs is critical to meet the needs of all US families.

Keywords: Hispanic, Latino, Latinx, parent, interventions, child, behavior, cultural adaptation, racial group, ethnic groups, social learning, problem behavior

Parenting programs have been developed as short-term interventions to improve parent-child relationships and child behavior (Furlong et al., 2013). Grounded in attachment and social learning theories (Bandura, 1977), ample research provides evidence of the effectiveness of parenting programs in reducing challenging behavior (Barlow, Parsons, & Stewart-Brown, 2005; Furlong et al., 2013) and improving educational (Hallam, Rogers, & Shaw, 2006) and mental health outcomes (Barlow et al., 2005) in children, as well as reducing parent stress (Reyno & McGrath, 2006). Parenting programs are especially important given that early behavioral problems, which impact at least 1 in 5 children under age 5 in the US, are associated with impairments in multiple domains, including family, academic, and social functioning, which often continue into adulthood (Sayal, Washbrook, & Propper, 2015).

One common delivery method for parenting programs is the group-based format, in which multiple parents with similarly aged children attend the intervention together. In addition to increasing reach and reducing cost by delivering the intervention to multiple parents at one time, the group format promotes social cohesion and normalizes help-seeking behavior related to parenting. Though there is variation with regard to duration, format, terminology, and target population, manualized group parenting programs share a focus on replacing harsh, inconsistent discipline and overly permissive discipline with structured, positive behavior management skills and strategies. Another commonality among such programs is that most have been developed for and evaluated in non-Hispanic (NH), White, English-speaking families. However, 25% of children (0–18) in the US have at least one foreign born parent, 23% speak a language other than English at home, and nearly 45% are Hispanic, NH Black, or NH Asian (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2019; Child Trends, 2019). This leaves a large portion of the population underserved; indeed, racial/ethnic minorities and non-English speaking families are least likely to enroll in, and most likely to drop out from such programs (Reyno & McGrath, 2006).

This failure to be inclusive of families from a variety of racial/ethnic backgrounds in parenting programs is unfortunate because children in these unserved populations experience life circumstances and structural barriers to care that place them at greater risk of behavior problems and unmet needs. High rates of socioeconomic disadvantage, inadequate social infrastructure, neighborhood exposure to violence, repetitive experiences of discrimination, and chronic exposure to racism among minority children can have significant adverse effects on children’s mental health, including depression, behavior problems, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002). Hispanic youth and NH Black youth experience a significant number of mental health problem, and in many cases, more problems than White children (Haack, Kapke, & Gerdes, 2016). For Native American adolescents, prevalence of mental problems appears to be higher than for comparable non-Native adolescents, with rates of substance use disorders as high as 27% and disruptive behavior disorders as high as 32% (Gone & Trimble, 2012). No large studies documenting rates of psychiatric disorders in Asian American and Pacific Islander youth have been conducted, though small studies suggest few differences between these youth and White youth (Edman et al., 1998).

Because diverse population groups are more likely to participate in programs that resonate with their cultural norms, values, and experiences, it stands to reason that adapting manualized parenting programs for racial/ethnic minorities may improve program engagement and attendance among these underserved groups (Barrera, Castro, & Steiker, 2011). They may also benefit more from programs that incorporate methods of learning, understanding, and developing skills that are familiar. Attending to culture in parenting interventions specifically may be particularly salient as cultural differences in rules, beliefs, preferences, codes of communication, and standards of behavioral competence have implications for parenting practices (Bornstein, 2012; Kotchick & Forehand, 2002). Additionally, parents and their children may have different cultural reference points, experience different levels of acculturation, and have different language preferences. Thus, cultural adaptations of parenting programs must navigate these complex issues.

Cultural adaptation is the process of applying modifications intended to increase the fit of the intervention to the target population, while protecting scientific integrity (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004). Adaptation (as opposed to de novo development) is supported by the assumptions that (1) behaviors targeted by interventions are exhibited across cultures (e.g. child behavior problems), and (2) how groups understand these behaviors and are willing to engage in treatment may differ across cultures. Multiple meta-analyses have examined the effectiveness of culturally adapted mental health interventions, with most reporting moderate effect sizes (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011; Hall, et al., 2016; Hernandez Robles, et al., 2018; Rathod, et al., 2018; Soto, et al., 2018; Van Mourik, et al., 2017). Because many studies to date have low statistical power or methodological limitations such as failure to isolate the unique impact of adaptations, continued research is needed to further clarify the contribution of cultural adaptation to address the well documented racial/ethnic disparities in mental health.

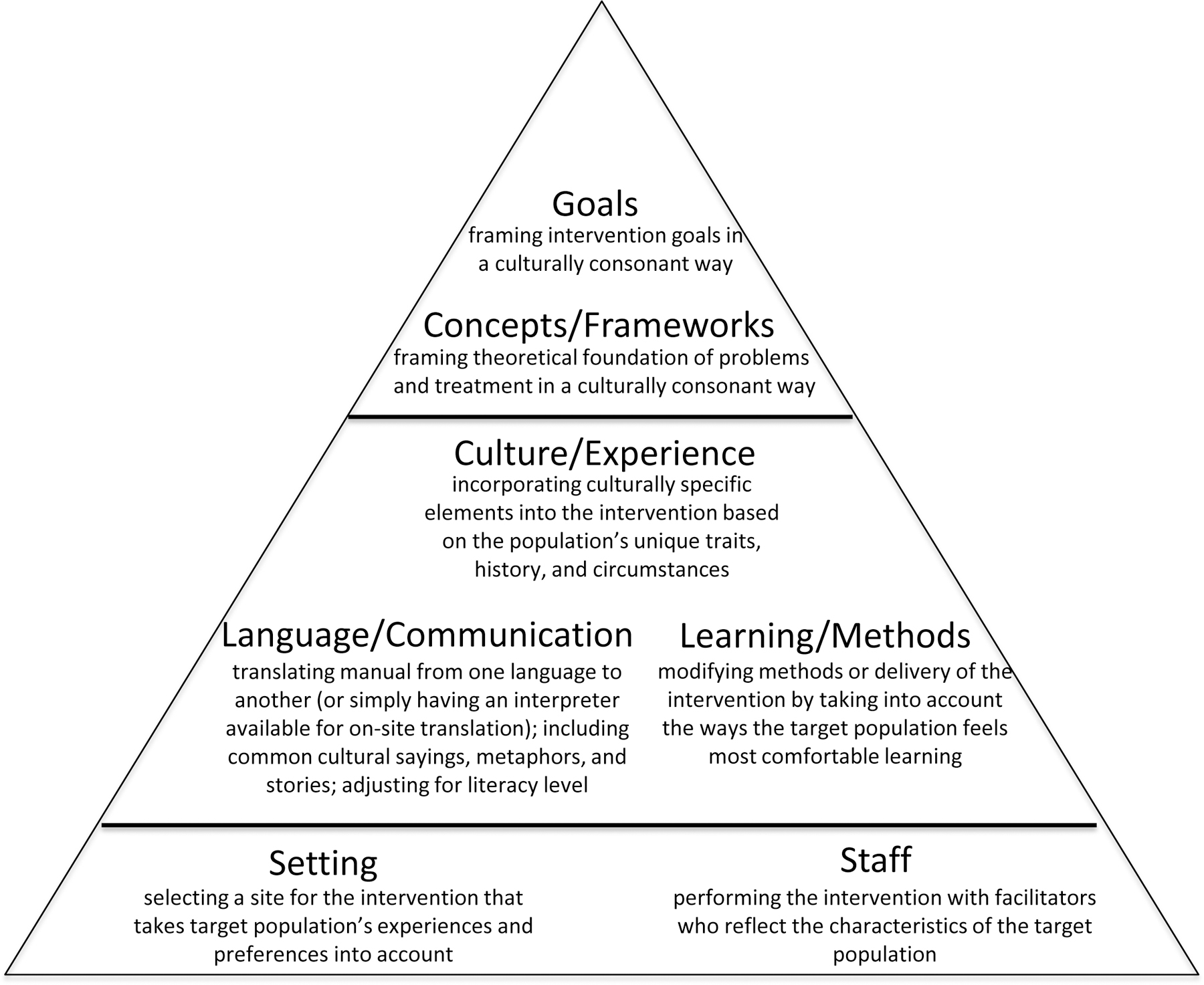

By contrast, this review seeks to assess the quality of the adaptation process rather than the effectiveness of culturally adapted interventions themselves. There is variation in the literature in terms of adaptation quality and the frameworks used to guide adaptation. Some models inform what to adapt in the delivery and content of the intervention, while other frameworks focus on when and how to adapt, and who to include in the process. Generally, these models recommend including stakeholders, using formative research methods, rigorously documenting changes, and evaluating the adapted intervention (Bernal & Adames, 2017; Bernal & Domenech Rodríguez, 2012; Domenech Rodriquez & Wieling, 2005; Resnicow, et al., 2000). To guide our review of culturally adapted interventions, we rely on a modification of Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido’s (1995) framework, as well as Falicov’s (2009) description of the levels of cultural adaptations (Figure 1). Drawing on research on ecological validity and cultural sensitivity in treatment and interventions (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; Falicov & Karrer, 1984), our framework provides a hierarchy for cultural adaptation. At the bottom of the hierarchy, we place the most visible adaptations of programs: language, setting, and staff. At the top of the hierarchy, we place adaptations requiring more fundamental shifts to ensure the cultural consonance of interventions. These adaptations require a shift from an etic (outside the culture) to an emic (within the culture) perspective, as well as a shift from a cultural deficit model towards an integrative model of cultural strengths and developmental competencies (Coll et al., 1996).

Figure 1.

Hierarchy of cultural adaptations

Finally, in our review of the literature of culturally adapted group parenting interventions, we consider implementation and evaluation variables discussed by Baumann, Cabassa, & Stirman (2017). When an intervention is adapted for a new population, it is important to attend to fidelity of the original intervention, to carefully describe and document the nature of the adaptations, and to evaluate the impact of the adapted intervention on the desired outcome(s) (Baumann et al., 2017). Although critical to the cultural adaptation process, understanding the results of evaluations on desired outcomes was not the focus of this review.

METHOD

Study Selection

We examined manualized group parenting interventions initially created for and studied in one population, then culturally adapted for a distinct new population. Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Meta-Analysis guidelines (Moher et al., 2015), the research team worked closely with a reference librarian to develop a literature search strategy using the following electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (Table S1). Initial searches were conducted in December 2018 and repeated in April 2019 to capture any newly published or recently added articles. Key words or phrases in the search strategy included a combination of the terms “parenting program,” “parent training,” “culturally adapted,” “culturally sensitive,” “manualized,” and “parent child relationship.” Searches were limited to peer-reviewed articles published in English from January 1, 2000 to April 1, 2019. Two co-authors reviewed abstracts of each article to determine if the article met inclusion/exclusion criteria. If there was uncertainty about whether the article should be included, a third co-author reviewed the abstract. The references of all included articles were reviewed and the corresponding authors of all included articles were contacted to identify any other publications related to program adaptation. These publications were subsequently retrieved and reviewed based on our inclusion/exclusion criteria. Overall, we identified 381 articles from our search (Figure 2). Of these, 41 articles describing 23 distinct program adaptations met our criteria for inclusion. Because this was a literature review which did not involve human subjects, Institutional Review Board oversight was not indicated.

Figure 2.

Literature search algorithm

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included if they pertained to group-based, manualized programs that provided training and education to parents of children ages 0–18 years with or without behavioral problems. To be included, articles had to focus on cultural adaptations in which concrete changes were made to an original program in an effort to offer a distinct, culturally sensitive version of the program to a different population. Programs developed de novo for specific cultural populations were not included in this review.

Review Criteria

Each included article was initially reviewed in-depth by at least one member of the research team and coded based on established review criteria (Table 1). Then, the article was discussed by the research team and the coding was accepted or revised based on a review by a second member of the research team and consensus of the team. We first identified general characteristics of the adapted parenting program including the population targeted and the delivery methods or structure. We next reviewed each article to assess the cultural adaptation process utilized. We considered the sources of cultural knowledge utilized to inform the adaptation as well as the specific types of adaptations made. Last, we reviewed the strategies utilized to monitor the adaptation process, and to evaluate each culturally adapted program.

Table 1:

Review criteria

| Criteria | Description | |

|---|---|---|

|

Parenting Program Characteristics

| ||

| Target Population | Provides description of the population the program is intended to affect | |

| Child ages | Ages of the children the program is intended to affect | |

| Delivery Method | States the number of sessions and type of format (e.g. parent group, child group, home visit) used | |

|

Cultural Adaptation Processed Applied | ||

| Source of cultural knowledge | Literature | Consulted peer-reviewed publications or other relevant written sources |

| Experts | Consulted experts in the cultural group and cultural adaptations | |

| Previous participants | Consulted participants in original program who closely match the target population | |

| Future recipients | Consulted target population members who have not yet completed the program | |

| Implementation evaluation | Conducted multiple pilot groups with iterative changes to the program | |

|

| ||

| Cultural Adaptations | Goals | Reframed goals to ensure cultural congruence |

| Concepts or Frameworks | Framed theoretical foundations of the problems and treatments to ensure cultural congruence | |

| Delivery Methods | Modified the delivery methods to account for the learning preferences and needs of the target population | |

| Culture or Experience | Incorporated the target population’s unique cultural experiences, traits, history, and circumstances into the intervention | |

| Setting | Selected sites based on target population’s experiences and preferences | |

| Staff | Hired facilitators who reflect the language and culture of the target population | |

| Language or Communication | Translated manuals and modified the language used (i.e. words, metaphors, stories) and communication methods (e.g., written, oral, pictorial) | |

|

Strategies used to Implement and Evaluate Programs | ||

| Systematization | Documented all changes made to the program in an organized and systematic way for publication | |

| Fidelity | Core | Retained key components/essential ingredients of the original program |

| Dose | Retained original length/duration of the original program | |

| Direct methods | Trained observers code for core components (in-person, audio, video) | |

| Indirect methods | Self-report checklists completed by implementers or program participants | |

|

| ||

| Evaluation Methods | Piloted | Conducted a pilot study with the nascent adapted program |

| Satisfaction | Measured parent satisfaction with the adapted program among participants | |

| Pre-/post-test | Measured and compared outcomes in the same participants before and after program completion to evaluate change | |

| RCT | Randomized participants into treatment and control groups to compare effectiveness before and after intervention | |

|

| ||

| Biases Addressed | Selection | Avoided selection bias by ensuring the final study population was representative of the target population. |

| Measurement | Avoided measurement bias by using culturally validated instruments with adequate psychometric data in the target population | |

| Confounding | Controlled for confounders through study design or data analysis | |

RESULTS

Adapted Group Parenting Program Characteristics

Among the 41 articles that met inclusion criteria, we identified 23 distinct cultural adaptations of parenting interventions (Table 2). Only one of these programs served children younger than 3 years; fourteen served children ages 3–12; six served adolescents ages 13–18; two adaptations did not discuss the target age of the child. The populations targeted by these adapted programs included Hispanic (11), east Asian (4), African American (2), Somalian and Pakistani (1), South African (1), indigenous Polynesia (Māori) (1), American Indian (1), rural Appalachian (1), and Muslim (1) families.

Table 2.

Adapted parenting program characteristics

| Author (Year) | Adapted program name | Original program name | Number Sessions | Program Format | Child ages | Targeted population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baumann (2014) | CAPAS-Mexico | Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación (CAPAS) | N/A | PG | 6–12y | Mexican parents of children with borderline or clinical-level externalizing behaviors |

| Beasley (2017) | Legacy for Children | Legacy for Children | ~100 | PG, PCG, IP | 0–5y | Spanish speaking low-income mothers |

| Bjørknes (2011, 2012a, 2012b, 2015) | Parent Management Training-Oregon Model (PMTO) | Parent Management Training-Oregon Model | 18 | PG | 3–9y | Mothers from Somalia and Pakistan living in Norway |

| Bogart (2013) | Let’s Talk! | Talking Parents, Healthy Teens | 5 | PG | 11–15y | Parents of South African adolescents |

| Brody (2004) | Strong African American Families (SAAF) | Strengthening Families Program - Revised | 7 | PG,PCG, CG | 11y | African American parents in rural US south |

| Coard (2004, 2007) | Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies (BPSS) | Parenting the Strong-Willed Child | 12 | PG | 5–6y | Low-income African American parents in urban communities |

| Dumas (2010, 2011), López (2018) | Criando a Nuestros Niños Hacia el Éxito (CANNE) | Parenting Our Children to Excellence (PACE) | 8 | PG | 3–7y | Low-income Latino families |

| Keown (2018) | Te Whānau Pou Toru (The Three Pillars of Positive Parenting) | Positive Parenting Program (Triple P) | 2 | PG | 3–7y | Māori parents in New Zealand of young children with behavior concerns |

| Kulis (2015, 2016) | Parenting in 2 Worlds (P2W) | Familias: Preparando la Nueva Generación (FPNG) | 10 | PG | 10–17y | Urban American Indian parents |

| Lau (2010, 2011), Ho (2012) | Incredible Years | Incredible Years | 14 | PG | 5–12y | Chinese-speaking immigrant parents with parental discipline or child behavior concerns |

| Marek (2006) | Strengthening Families Program | Strengthening Families Program | 14 | PG,PCG, CG, HV | 6–10y | Rural Appalachian families |

| Martinez (2005) | Nuestras Familias: Andando Entre Culturas; “Our Families: Moving Between Cultures” | Oregon Social Learning Center Basic Parent Management Training | 12 | PG | 11–13y | Spanish-speaking Latino families |

| Domenech Rodríguez (2011), Parra-Cardona (2009, 2012, 2016, 2017a) | Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación (CAPAS) | Parent Management Training Oregon Model - GenerationPMTO | 12 | PG | 4–12y | Spanish-speaking Latino parents living in US |

| Parra-Cardona (2015) | CAPAS-Monterrey | CAPAS | 14 | PG | 4–12y | Mexican parents living in Monterrey referred due to concern for child maltreatment |

| Parra-Cardona (2008, 2012, 2016, 2017a, 2017b) | CAPAS - Enhanced | CAPAS | 12 | PG | 4–12y | Spanish-speaking Latino parents living in US |

| Parra-Cardona (2019) | CAPAS - Youth | CAPAS | 9 | PG | 12–14y | Latino families with adolescent exhibiting mild-moderate behavior challenges |

| Scourfield (2015) | Family Links Islamic Values | Family Links Nurturing Program | 9 | PG | N/A | Muslim parents in the UK |

| Stein (2018) | Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP) | Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP) | 10 | PG | 5–7y | Latina mothers exposed to domestic violence |

| Tamm (2005), Lakes (2009) | CUIDAR (CHOH/UCI Initiative for the Development of Attention Readiness) | Community Parent Education (COPE) | 10 | PG | 3–5y | Spanish-speaking Latino parents |

| Thompson (2017) | New Forest Parenting Program (NFPP)-Hong Kong | New Forest Parenting Program | 8 | PG | N/A | Parents of children with ADHD in Hong Kong |

| Shimabukuro (2017), Thompson (2017) | New Forest Parenting Program-Japan | New Forest Parenting Program | 11 | PG | 6–13y | Parents of children with ADHD in Japan |

| Tsang (2013, 2014, 2016) | Challenging Years | Challenging Years | 4 | PG | 11–14y | Parents with parent-child conflict in Hong Kong |

| Valdez (2013a, 2013b) | Fortalezas Familiares; “Family Strengths” | Keeping Families Strong | 12 | PG, PCG, CG | 9–18y | Immigrant Latina mothers with depression |

Abbreviations: Years (y), Parent Group (PG), Parent-Child Group (PCG), Child Group (CG), Individual Parent (IP), Home Visit (HV)

Most programs included 7–14 sessions. Sessions were described as interactive and incorporated a variety of teaching methods, such as group discussions, demonstrations, role-play, homework activities, and traditional didactic methods. Some programs specifically included socialization time for parents, usually during a meal provided as part of the program. Most programs focused on adult-only sessions, though some reported integrated parent-child sessions, and still others held separate sessions for children and adults in addition to joint sessions.

Cultural Adaptation Processes Applied

Source of Cultural Knowledge.

The most common source of cultural knowledge for adaptations was consultation with cultural experts (Table 3). Of the 23 programs, 22 reported relying on individuals deemed to have expertise in the particular cultural group the program was being adapted to serve. For example, Dumas, et al. (2010) sent six professional consultants the original manualized curriculum and asked for written feedback to identify problematic issues and suggest modifications.

Table 3.

Cultural adaptation components

| Author (Year) | Program Name | Sources of cultural knowledge | Cultural Adaptations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals | Concepts/ Framework | Delivery Methods | Culture/ Experience | Language | Setting | Staff | |||

| Baumann (2014) | CAPAS-Mexico | L,E,F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Beasley (2017) | Legacy for Children | E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bjørknes (2011, 2012a, 2012b, 2015) | PMTO | E,F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Bogart (2013) | Let’s Talk! | L,E,I | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Brody (2004) | SAAF | L,E,F | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Coard (2004, 2007) | BPSS | L,E,F,I | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Dumas (2010, 2011), López (2018) | CANNE | L,E,I | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Keown (2018) | Te Whānau Pou Toru | E,F | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Kulis (2015, 2016) | P2W | L,E,F,I | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lau (2010, 2011), Ho (2012) | Incredible Years | L,E | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Marek (2006) | SFP | L,P,I | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Martinez (2005) | Nuestras Familias | L,E,F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Domenech Rodríguez (2011) Parra-Cardona (2009, 2012,2016, 2017a) | CAPAS | L,E,F,I | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Parra-Cardona (2015) | CAPAS-Monterrey | L,E,F,I | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Parra-Cardona (2008, 2012, 2016, 2017a, 2017b) | CAPAS - Enhanced | L,E,P,F,I | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Parra-Cardona (2019) | CAPAS - Youth | L,E,I | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scourfield (2015) | Family Links Islamic Values | L,E | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Stein (2018) | MEP | L,E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tamm (2005) Lakes (2009) | CUIDAR | L,E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thompson (2017) | NFPP-Hong Kong | L,E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Shimabukuro (2017), Thompson (2017) | NFPP-Japan | L,E,I | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Tsang (2013, 2014, 2016) | Challenging Years | L,E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Valdez (2013a, 2013b) | Fortalezas Familiares | L,E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total Count (n=23) | -- | 2 | 7 | 8 | 20 | 20 | 6 | 20 | |

Abbreviations: Literature (L), Experts (E), Previous Participants (P), Future Recipients (F), Implementation (I), No (0), Yes (1)

In addition to relying on experts, 20 programs referenced reviewing published literature regarding specific cultural aspects of parenting during the development of the adapted program. For example, the Strong African American Families program adapted the Strengthening Families Program to account for empirical evidence indicating that involved-vigilant parenting protects African American youths from dangerous surroundings (Brody et al., 2004).

Among the 23 adaptations, 2 included previous parent participants and 10 included future participants in their program development; 10 adapted their programs by implementing multiple pilot programs and incorporating iterative feedback. The Parenting in 2 Worlds adaptation was rigorous in this regard and relied on both parent input and iterative pilot testing (Kulis, Ayers, & Baker, 2015; Kulis et al., 2016). During the first phase of their adaptation, future recipients received a minimally modified version of the program that focused on modifying the language of the program (e.g., examples and terminology used) to make it more appropriate for urban American Indian parents. They then collected quantitative and qualitative data regarding the cultural fit of each curriculum lesson’s content, activities, and learning approach. This feedback was subsequently used in making additional modifications for the next pilot of the program.

Cultural Adaptations.

Starting from the top of our adaptation hierarchy (Table 3), only two related programs – Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación (CAPAS) (Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, & Schwartz, 2011) and CAPAS-Enhanced (Parra-Cardona, et al., 2017b) – explicitly discussed culturally adapting the program goals. The original program, Parent Management Training, focuses on strengthening parent-child relationships. The CAPAS adaptation reframed this goal in a culturally relevant manner by emphasizing that encouragement leads to increased displays of respeto and that participating in problem solving helps support a child to valerse por si mismo. CAPAS-Enhanced built on this framework in presenting the program goals through the lens of familismo, a Hispanic cultural value regarding the importance of familial loyalty, respect, and cooperation.

Seven of the adaptations discussed reframing concepts or frameworks of the intervention (Table 3). Specifically, they reframed the conceptualization of the problem (e.g., child behavioral problems, maladaptive parenting, negative parent-child relationships) and the targeted treatments (e.g., parent-child play, labeled praise, shared decision making, limit-setting) in a culturally congruent manner. For example, in the Family Links Islamic Values adaptation, Scourfield & Nasiruddin (2015) included texts from Qur’an and Hadith that provided justification for the messages of each program session. In one session, the importance of modeling behavior was supported by the story of the Prophet Muhammad’s grandchildren who taught the correct form of washing oneself by demonstration rather than attempting to teach through criticism.

Eight programs discussed changes to the delivery methods of the original program in order to address cultural differences (Table 3). These types of changes included re-organizing sessions into weekly 2-hour lunchtime sessions over 5 weeks rather than weekly 1-hour lunchtime sessions over 8 weeks (Bogart et al., 2013), adapting workshop lessons to introduce and approach topics holistically and experientially rather than presenting material as a set of elements or steps to be assembled into a whole (Kulis et al., 2016), and replacing the use of puppets, which require the children to be comfortable taking risks and performing in front of peers, with role plays modeled by facilitators (Marek, Brock, & Sullivan, 2006).

Adaptations regarding culture and experience, language and communication, or staff were carried out most often, whereas few adaptations explicitly stated selecting a setting for the adapted intervention based on the population’s cultural experience (Table 3). Adaptations to reflect the culture and experiences of the targeted population included substituting culturally relevant songs, books, and examples for those in the original program curriculum (Beasley et al., 2017); welcoming participants through use of karakia (prayer) and mihi whakatusa (welcome) at the beginning of each session of the adapted program (Keown et al., 2018); and expanding discussions of how to promote academic achievement in the presence of overt and subtle instances of racism, prejudice, and discrimination (Coard et al., 2007). Adaptations to address language and/or communication included translation of manuals and program materials into new languages, adjustments to reduce reading levels and include pictures reflecting the target community (Beasley et al., 2017), and changes in the use of pronouns, metaphors, and expressions (Coard et al., 2007). Staffing adaptations were related to language and communication, as programs sought to recruit individuals who were fluent or native speakers in target languages and had substantial knowledge of or experience with the target population. One program (Bjørknes & Manger, 2012) relied on in-person translators rather than having fluent or native speakers deliver the adapted program. Some adaptations, such as Thompson et al.’s (2017), also discussed the challenges of training and supervising staff remotely when programs were adapted for populations at great geographic distance.

Strategies Used to Implement and Evaluate Adaptations

Systemization and fidelity.

Only Dumas et al. (2010) discussed a systematic method to record all cultural adaptations made to a program (Table 4). Each change was recorded and coded to quantify the extent to which the new program corresponded to the original. However, including Dumas et al. (2010), none of the adapted programs published a full record of their modifications. In contrast, all the adapted programs reviewed discussed the fidelity of their adaptations and indicated that the adaptations did not alter core components of the original program. About half of the programs retained the original program dose, three programs increased the dose, and six programs reduced the dose. Dosage increases were justified because of the additional time required to explain/teach core program components or because of addition of new culturally relevant material. Dosage decreases were justified by stating that although dose was reduced, core components were retained. Four programs reported using both direct and indirect methods to assess and monitor fidelity, 8 programs relied on direct methods only, 3 programs relied on indirect methods only, and 8 did not report the methodology used.

Table 4.

Strategies used to implement and evaluate adaptations

| Author (Year) | Program Name | Systematic | Fidelity | Methods | Biases Addressed | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core | Dose | Direct | Indirect | P | PP | RCT | PS | S | M | C | |||

| Baumann (2014) | CAPAS-Mexico | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Beasley (2017) | Legacy for Children | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bjørknes (2011, 2012a, 2012b, 2015) | PMTO | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bogart (2013) | Let’s Talk! | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Brody (2004) | SAAF | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Coard (2004, 2007) | BPSS | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Dumas (2010, 2011), López (2018) | CANNE | 1 | 1 | = | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Keown (2018) | Te Whānau Pou Toru | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Kulis (2015, 2016) | P2W | 0 | 1 | + | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Lau (2010, 2011), Ho (2012) | Incredible Years | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Marek (2006) | SFP | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Martinez (2005) | Nuestras Familias | 0 | 1 | − | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Domenech Rodríguez (2011) Parra-Cardona (2009, 2012, 2016, 2017a) | CAPAS | 0 | 1 | − | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parra-Cardona (2015) | CAPAS-Monterrey | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Parra-Cardona (2008, 2012, 2016, 2017a, 2017b) | CAPAS - Enhanced | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Parra-Cardona (2019) | CAPAS - Youth | 0 | 1 | − | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scourfield (2015) | Family Links Islamic Values | 0 | 1 | − | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Stein (2018) | MEP | 0 | 1 | = | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tamm (2005), Lakes (2009) | CUIDAR | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Thompson (2017) | NFPP-Hong Kong | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shimabukuro (2017), Thompson (2017) | NFPP-Japan | 0 | 1 | + | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Tsang (2013, 2014, 2016) | Challenging Years | 0 | 1 | = | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Valdez (2013a, 2013b) | Fortalezas Familiares | 0 | 1 | + | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total Count (n=23) | 1 | 23 | -- | 12 | 7 | 15 | 8 | 11 | 17 | 17 | 13 | 11 | |

Abbreviations: Yes (1), No (0); Piloted (P), Pre- and Post-Tested (PP), Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT), Patient Satisfaction (PS). Types of Biases: Selection (S), Measurement (M), Confounding (C). See Table 1 for additional descriptions of each category.

Evaluation methods and addressing bias.

The methods used to evaluate programs included piloting in the target population (15), collecting data on parent satisfaction (17), pre-/post-test designs (8), and Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) (11). The majority of programs also documented at least one effort to address potential biases: 11 addressed confounders, 13 measurement bias, and 17 selection bias in their study designs. This included detailed and rigorous procedures to ensure the cultural consonance of instruments used to measure outcomes. Qualitative and cognitive interviewing techniques with the target population were used to adapt, add, and drop survey items (Bogart et al., 2013); focus groups were conducted to develop and refine study procedures and instruments; native speakers were asked to review the final surveys for cultural relevance and acceptability; and cross-language comparisons in which bilingual speakers completed the study instruments in both languages were utilized to determine the appropriateness of the measures (Bogart et al., 2013; Dumas et al., 2010; Brody et al., 2004).

DISCUSSION

Manualized skill-based group parenting programs positively impact multiple parent and child outcomes (Barlow, et al., 2005; Furlong et al., 2013; Reyno & McGrath, 2006), yet have mostly been developed for and evaluated among a NH White, English-speaking population. A large share of children in the US are Hispanic or non-White and/or have parents who speak a language other than English at home. Effective group-based parenting programs must be available and accessible for these populations. We identified 23 culturally adapted group-based parenting programs. Our review of these adaptations underscores that lower-order aspects of cultural adaptation focusing on language, translation, and staffing are more common than higher-order adaptations focusing on goals, concepts, and methods.

Scholars have suggested that more fully or deeply adapted interventions will be more effective than those that are relatively less adapted. Few studies have tested this theory as evaluations of adapted interventions most often include a control group rather than utilizing comparative effectiveness designs that enable the parsing out of the differential effects of specific adaptations. One meta-analysis of cultural adaptations to mental health treatments conducted by Soto et al. (2018) provides equivocal evidence: one lower-order adaptation (language) and one higher-order adaptation (goals) were the two adaptations most predictive of positive outcomes among the adaptations included in the meta-analysis. This may reflect limited details on specific adaptations included in publications, which we discuss later. While our review neither supports nor refutes the effectiveness of cultural adaptation for group parenting programs, we have identified two specific reasons why evaluating the relative effectiveness of cultural adaptation is challenging based on the current literature. First, cultural adaptations are not well articulated in many of the papers we reviewed. Second, few of the adaptations have been subject to rigorous or comparative evaluations.

To the first point, many articles report on their sources of knowledge and evaluation methods; however, only one of those included in this review reported systematically documenting each adaptation with regard to what was changed, how it was changed, and why it was changed. This failure of scholars to report what, how, and why they are adapting has been previously described (Baumann et al., 2015) and is problematic because adaptation processes that are not documented, cannot be replicated, cannot be evaluated, and thus are poorly understood (Stirman et al., 2013; Chambers & Norton, 2016). Another important reason to systematically document and publish cultural adaptations is that some adapted interventions are not completely de novo, but rather expand upon on a prior adaptation (e.g., CAPAS and CAPAS-Enhanced), suggesting that adaptations are not necessarily finalized after an initial adjustment. This underscores the importance of publishing the cultural adaptation of interventions so that one group may build upon, rather than reinvent, the work of another group. Of note, the absence of reporting may not be attributed to the scholars themselves, but may in fact be related to the failure of the research community to make space for such reporting; the thorough and rigorous documentation required to accomplish this reporting is unlikely to fit into the constraints imposed by most academic peer reviewed journals.

Many concerns about adaptation are related to whether changes preserve fidelity (Chambers & Norton, 2016). Though all adaptations in this review reported retaining core components, when examining other elements of fidelity (i.e. dose) as well as how fidelity was actually monitored (direct vs. indirect vs. not reported), it is difficult to know whether fidelity and adherence to core components was in fact achieved. For instance, six of the programs reported a dose reduction. Only half of the programs reported using direct methods, the gold standard for measuring fidelity. Importantly, even in the setting of maintaining dose and accurately monitoring fidelity through direct and indirect methods, it is impossible know whether fidelity is truly maintained during the adaptation process itself without carefully documenting what was adapted, how it was adapted, and why. Carefully documenting and publishing adaptations will serve to reduce uncertainty regarding the adaptation process, increase the external validity of the adapted intervention, and ultimately maximize the potential to evaluate fidelity and the impact of the adapted intervention on desired outcomes.

Equally important to systematically documenting and reporting the adaptation process is evaluating the culturally adapted parenting program. Our review indicates that more sophisticated evaluation methods are required to achieve this goal. Fewer than half of the culturally adapted group parenting programs we reviewed were evaluated with an RCT. Yet, there is general consensus that, in addition to pilot testing, cultural adaptations should be formally evaluated with effectiveness trials (Chambers, Glasgow, & Stange, 2013). Though the purpose of our review was not to examine the effectivness of adapted programs, this is critical and should be undertaken. In our review, among cultural adaptations of group parenting program that were evaluated, the most common trial design was an RCT, which compares the adapted program to usual care. However, other appropriate designs of effectiveness trials have been proposed to test adaptations of interventions. These include the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART), the Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Usability and User Centered Design (UCD) (Baumann et al., 2017). Such designs may be particularly attractive for evaluating cultural adaptations of group parenting programs that are inherently complex and multicomponent. These more sophisticated evaluation designs may also facilitate our understanding of what types of adaptations or which components of the adaptation yield the desired outcomes. Nevertheless, as discussed above, such effectiveness trials are only possible if adaptation components are first distinctly characterized and documented.

Despite the contributions of our study to the literature, our review has limitations. First, it is possible that our search was incomplete given the wide variety of terminology used in the positive parenting intervention literature. To broaden our inclusion, we reviewed the references of all included studies and relevant meta-analyses to identify any additional publications related to cultural adaptation. We also contacted the authors of included adaptations to ensure we had reviewed all relevant articles. Even so, the imperfect assignment of titles, key words, and abstract terminology poses an inherent challenge for database searches and thus our review is unlikely to be comprehensive. Furthermore, cultural adaptation of parenting interventions very likely occurs in usual care without intent for publication or dissemination; such adaptations would not be captured by this review. Finally, it is possible that many of the adaptations we reviewed did include the specific components we attempted to abstract (e.g., framing problems in a culturally constant way or systematically documenting all changes), but did not publish them. Yet, such unpublished data fails to contribute to the general knowledge on cultural adaptation of parenting programs.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that additional scholarship documenting the process and evaluation of culturally adapted parenting programs is needed. When cultural adaptations are undertaken, clearly specifying what, why, and how adaptations were made and rigorously evaluating the adaptations will facilitate external validity of the adapted group parenting programs, its outcomes, and the adaptation process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Eddy Fernandez and Sofia Ocegueda for assistance with the literature search and article retrieval/review.

Funding:

This research was supported by the Carolina Population Center and its National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Grant Award Number P2C HD50924 (Perreira), the Integrating Special Populations/ North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute through Grant Award Number ILITR002489 (Perreira), the NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), through Grant KL2TR001109 (Schilling), and NIH/NCATS through Grant Award Number UL1TR001111 (Perreira and Schilling). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the funders.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

Studies included in the systematic review are marked with an asterisk.

- Annie E Casey Foundation. (2019). Kids Count Data Center: Children who speak a language other than English at home in the United States. Retrieved from datacenter.kidscount.org

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow J, Parsons J, & Stewart-Brown S (2005). Preventing emotional and behavioural problems: The effectiveness of parenting programmes with children less than 3 years of age. Child: Care, Health and Development, 31(1), 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG, & Steiker LKH (2011). A critical analysis of approaches to the development of preventive interventions for subcultural groups. American journal of community psychology, 48(3–4), 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ, & Stirman SW (2017). Adaptation in dissemination and implementation science. In Brownson RC, Colditz GA, & Proctor EK (Eds.), Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health: Translating Science to Practice (pp. 286–300).

- *Baumann AA, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Amador NG, Forgatch MS, & Parra Cardona (2014). Parent management training-Oregon model (PMTO™) in Mexico City: Integrating cultural adaptation activities in an implementation model. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(1), 32–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Powell BJ, Kohl PL, Tabak RG, Penalba V, Proctor EK, .. Cabassa LJ (2015). Cultural adaptation and implementation of evidence-based parent training: A systematic review and critique of guiding evidence. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Beasley LO, Silovsky JF, Espeleta HC, Robinson LR, Hartwig SA, Morris A, & Esparza I (2017). A qualitative study of cultural congruency of Legacy for Children™ for Spanish-speaking mothers. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, & Wampold BE (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, & Bellido C (1995). Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(1), 67–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2012). Cultural adaptation in context: Psychotherapy as a historical account of adaptations. In Bernal G & Domenech Rodríguez MM (Eds.), Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations (pp. 3–22). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, & Adames C (2017). Cultural adaptations: Conceptual, ethical, contextual, and methodological issues for working with ethnocultural and majority-world populations. Prevention Science, 18(6), 681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bjørknes R, Jakobsen R, & Nærde A (2011). Recruiting ethnic minority groups to evidence based parent training. Who will come and how? Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- *Bjørknes R, Kjøbli J, Manger T, & Jakobsen R (2012a). Parent training among ethnic minorities: Parenting practices as mediators of change in child conduct problems. Family Relations, 61, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- *Bjørknes R, & Manger T (2012b). Can parent training alter parent practice and reduce conduct problems in ethnic minority children? A randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 14, 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bjørknes R, Marit Larsen, Gwanzura-Ottemöller F, Kjøbli J (2015). Exploring mental distress among immigrant mothers participating in parent training. Children and Youth Services Review, 51, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- *Bogart LM, Skinner D, Thurston IB, Toefy Y, Klein DJ, Hu CH, & Schuster MA (2013). Let’s talk!, A South African worksite-based HIV prevention parenting program. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(5), 602–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting, 12(2–3), 212–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, … Luo Z (2004). The strong African American families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development, 75(3), 900–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, & Martinez CR (2004). The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science, 5(1), 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, & Stange KC (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science, 8(1), 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, & Norton WE (2016). The adaptome: Advancing the science of intervention adaptation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(4), S124–S131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. 2019. Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Child Population. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/racial-and-ethnic-composition-of-the-child-population

- *Coard SI, Foy-Watson S, Zimmer C, & Wallace A (2007). Considering culturally relevant parenting practices in intervention development and adaptation: A randomized controlled trial of the Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies (BPSS) Program. The CounselingPsychologist, 35(6), 797–820. [Google Scholar]

- *Coard SI, Wallace SA, Stevenson HC, & Brotman LM (2004). Towards culturally relevant preventive interventions: The consideration of racial socialization in parent training with African American families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(3), 277–293. [Google Scholar]

- Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, & McAdoo HP (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, & Schwartz AL (2011). Cultural adaptation of an evidence based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 170–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Rodríguez M, & Wieling E (2005). Developing culturally appropriate, evidence-based treatments for interventions with ethnic minority populations. In Voices of Color: First-Person Accounts of Ethnic Minority Therapists (pp. 313–334). SAGE Publications, Inc [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Arriaga X, Begle AM, & Longoria Z (2010). “When will your program be available in Spanish?” Adapting an early parenting intervention for Latino families. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(2), 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Dumas JE, Arriaga XB, Moreland Begle A, & Longoria ZN (2011). Child and parental outcomes of a group parenting intervention for Latino families: A pilot study of the CANNE program. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(1), 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman J, Andrade NN, Glipa J, Foster J, Danko G, Yates A, … Waldron J (1998). Depressive symptoms among Filipino American adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4(1), 45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ (2009). Commentary: On the wisdom and challenges of culturally attuned treatments for Latinos. Family Process, 48, 292–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ, & Karrer BM (1984). Therapeutic strategies for Mexican-American families. International Journal of Family Therapy, 6(1), 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, Hutchings J, Smith SM, & Donnelly M (2013). Cochrane Review: Behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years (Review). Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(2), 318–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual review of clinical psychology, 8, 131–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haack LM, Kapke TL, & Gerdes AC (2016). Rates, Associations, and Predictors of Psychopathology in a Convenience Sample of School-Aged Latino Youth: Identifying Areas for Mental Health Outreach. Journal of child and family studies, 25(7), 2315–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GCN, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, Marti CN, & Stice E (2016). A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 993–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallam S, Rogers L, & Shaw J (2006). Improving children’s behaviour and attendance through the use of parenting programmes: An examination of practice in five case study local authorities. British Journal of Special Education, 33(3), 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez Robles E, Maynard BR, Salas-Wright CP, & Todic J (2018). Culturally adapted substance use interventions for Latino adolescents: A systematic review and meta analysis. Research on social work practice, 28(7), 789–801. [Google Scholar]

- *Ho J, Yeh M, McCabe K, & Lau A (2012). Perceptions of the acceptability of parent training among Chinese immigrant parents: Contributions of cultural factors and clinical need. Behavior Therapy, 43(2), 436–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among US Children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry, 159(9):1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Keown LJ, Sanders MR, Franke N, & Shepherd M (2018). Te Whānau Pou Toru: A randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a culturally adapted low-intensity variant of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program for Indigenous Māori families in New Zealand. Prevention Science, 19(7), 954–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, & Forehand R (2002). Putting parenting in perspective: A discussion of the contextual factors that shape parenting practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 11(3), 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- *Kulis S, Ayers SL, & Baker T (2015). Parenting in 2 worlds: Pilot results from a culturally adapted parenting program for urban American Indians. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 36(1), 65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kulis SS, Ayers SL, Harthun ML, & Jager J (2016). Parenting in 2 worlds: Effects of a culturally adapted intervention for urban American Indians on parenting skills and family functioning. Prevention Science, 17(6), 721–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lakes KD, Kettler RJ, Schmidt J, Haynes M, Feeney-Kettler K, Kamptner L, … Tamm L (2009). The CUIDAR early intervention parent training program for preschoolers at risk for behavioral disorders: An innovative practice for reducing disparities in access to service. Journal of Early Intervention, 31(2), 167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lau AS, Fung JJ, Ho LY, Liu LL, & Gudiño OG (2011). Parent training with high risk immigrant Chinese families: A pilot group randomized trial yielding practice-based evidence. Behavior Therapy, 42(3), 413–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Lau AS, Fung JJ, & Yung V (2010). Group parent training with immigrant Chinese families: Enhancing engagement and augmenting skills training. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(8), 880–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *López CM, Davidson TM, & Moreland AD (2018). Reaching Latino families through pediatric primary care: Outcomes of the CANNE parent training program. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 40(1), 26–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Marek LI, Brock D-JP, & Sullivan R (2006). Cultural adaptations to a family life skills program: Implementation in rural Appalachia. Journal of Primary Prevention, 27(2), 113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Martinez CR Jr., & Eddy JM (2005). Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, … Stewart LA (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews, 4(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona J, Holtrop K, Córdova D Jr., Escobar-Chew AR, Horsford S, Tams L, .. Anthony JC (2009). “Queremos aprender”: Latino immigrants’ call to integrate cultural adaptation with best practice knowledge in a parenting intervention. Family Process, 48(2),211–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, Córdova D, Holtrop K, Villarruel FA, & Wieling E (2008). Shared ancestry, evolving stories: Similar and contrasting life experiences described by foreign born and US born Latino parents. Family Process, 47(2), 157–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, Domenech‐Rodriguez M, Forgatch M, Sullivan C, Bybee D, Holtrop K, … Bernal G (2012). Culturally Adapting an Evidence‐Based Parenting Intervention for L atino Immigrants: The Need to Integrate Fidelity and Cultural Relevance. Family Process, 51(1), 56–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, Aguilar Parra E, Wieling E, Domenech Rodríguez MM, & Fitzgerald HE (2015). Closing the gap between two countries: Feasibility of dissemination of an evidence-based parenting intervention in México. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 41(4), 465–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, Bybee D, Sullivan CM, Rodríguez MMD, Dates B, Tams L, & Bernal G (2017a). Examining the impact of differential cultural adaptation with Latina/o immigrants exposed to adapted parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(1), 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, López-Zerón G, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Escobar-Chew AR, Whitehead MR, Sullivan CM, & Bernal G (2016). A balancing act: Integrating evidence-based knowledge and cultural relevance in a program of prevention parenting research with Latino/a immigrants. Family Process, 55(2), 321–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona R, López-Zerón G, Leija SG, Maas MK, Villa M, Zamudio E, … Domenech Rodríguez MM (2019). A culturally adapted intervention for Mexican-origin parents of adolescents: The need to overtly address culture and discrimination in evidence based practice. Family Process, 58(2), 334–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Parra Cardona JR, López-Zerón G, Villa M, Zamudio E, Escobar-Chew AR, & Rodríguez MMD (2017b). Enhancing parenting practices with Latino/a immigrants: Integrating evidence-based knowledge and culture according to the voices of Latino/a parents. Clinical Social Work Journal, 45(1), 88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathod S, Gega L, Degnan A, Pikard J, Khan T, Husain N, … Naeem F (2018). The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: a practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 14, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwait RL, Ahluwalia JS, & Butler J (2000). Cultural sensitivity in substance abuse prevention. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Reyno SM, & McGrath PJ (2006). Predictors of parent training efficacy for child externalizing behavior problems–a meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(1), 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayal K, Washbrook E, & Propper C (2015). Childhood behavior problems and academic outcomes in adolescence: Longitudinal population-based study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(5), 360–368. e362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Scourfield J, & Nasiruddin Q (2015). Religious adaptation of a parenting programme: Process evaluation of the Family Links Islamic Values course for Muslim fathers. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(5), 697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Shimabukuro S, Daley D, Thompson M, Laver-Bradbury C, Nakanishi E, & Tripp G (2017). Supporting Japanese mothers of children with ADHD: Cultural adaptation of the New Forest Parent Training Programme. Japanese Psychological Research, 59(1), 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Soto A, Smith TB, Griner D, Domenech Rodríguez M, & Bernal G (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta‐analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Stein SF, Grogan-Kaylor AC, Galano MM, Clark HM, & Graham-Bermann SA (2018). Contributions to depressed affect in Latina women: Examining the effectiveness of the moms’ empowerment program. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirman SW, Miller CJ, Toder K, & Calloway A (2013). Development of a framework and coding system for modifications and adaptations of evidence-based interventions. Implementation Science, 8(1), 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Tamm L, Swanson JM, Lerner MA, Childress C, Patterson B, Lakes K, … Miller J (2005). Intervention for preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Service before diagnosis. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 5(5–6), 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- *Thompson MJ, Au A, Laver-Bradbury C, Lange AM, Tripp G, Shimabukuro S, … Daley D (2017). Adapting an attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder parent training intervention to different cultural contexts: The experience of implementing the New Forest Parenting Programme in China, Denmark, Hong Kong, Japan, and the United Kingdom. PsyCh Journal, 6(1), 83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Tsang Low Y (2013). Can parenting programme reduce parent-Adolescents conflicts in Hong Kong? Revista de Cercetare şi Intervenţie Socială(42), 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- *Tsang Low Y (2014). Parents’ perception of effective components of a parenting programme for parents of adolescents in Hong Kong. Revista de Cercetare şi Intervenţie Socială(46), 162–181. [Google Scholar]

- *Tsang Low Y (2016). Can Hong Kong Chinese parents and their adolescent children benefit from an adapted UK parenting programme. Journal of Social Work, 16(1), 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- *Valdez CR, Abegglen J, & Hauser CT (2013a). Fortalezas Familiares program: Building sociocultural and family strengths in Latina women with depression and their families. Family Process, 52(3), 378–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Valdez CR, Padilla B, Moore SM, & Magaña S (2013b). Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes of the Fortalezas Familiares intervention for Latino families facing maternal depression. Family Process, 52(3), 394–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mourik K, Crone MR, De Wolff MS, & Reis R (2017). Parent training programs for ethnic minorities: A meta-analysis of adaptations and effect. Prevention Science, 18(1), 95 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.