Abstract

Background:

Influenza is a significant threat to public health worldwide. Despite the widespread availability of effective and generally safe vaccines, the acceptance and coverage of influenza vaccines are significantly lower than recommended. Sociodemographic variables are known to be potential predictors of differential influenza vaccine uptake and outcomes.

Objectives:

This review aims to (1) identify how sociodemographic characteristics such as age, sex, gender, and race may influence seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance and coverage; and (2) evaluate the role of these sociodemographic characteristics in differential adverse reactions among vaccinated individuals.

Methods:

PubMed was used as the database to search for published literature in three thematic areas related to the seasonal influenza vaccine - vaccine acceptance, adverse reactions, and vaccine coverage.

Results:

A total of 3,249 articles published between 2010 and 2020 were screened and reviewed, of which 39 studies were included in this literature review. By the three thematic areas, 17 studies assessed vaccine acceptance, 8 studies focused on adverse reactions, and 14 examined coverage of the seasonal influenza vaccine. There were also two studies that focused on more than one of the areas of interest.

Conclusion:

Each of the four sociodemographic predictors – age, sex, race, and gender – were found to significantly influence vaccine acceptance, receipt and outcomes in this review.

Keywords: Influenza, Vaccine hesitancy, Vaccine coverage, Sex differences, Racial differences, Safety

1. Background

Influenza, commonly known as ‘flu’, is a contagious respiratory illness with symptoms such as fever, sore throat, cough, headaches, runny nose, body aches, muscle pains, and fatigue[1]. It is spread through airborne transmission of droplets when a person sneezes, coughs, or talks[1]. Transmission may also occur through contact with contaminated objects and surfaces[1]. Although generally self-limiting, influenza can lead to severe respiratory illness and even death. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates about 1 billion cases of seasonal influenza occur each year of which approximately 3–5 million are severe cases resulting in up to 650,000 deaths[2].

Influenza A and B viruses are responsible for the vast majority of cases during seasonal outbreaks[3]. As a result of mutations that allow for escape from preexisting population immunity, the composition of influenza vaccines must be updated frequently[4]. Two major types of influenza vaccine used worldwide are the inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) and the live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV)[5]. IIV is administered intramuscularly while the LAIV is administered as a nasal spray. Common side effects of the intramuscular IIV include fever, malaise, erythema at the injection site, and myalgia, while the intranasal LAIV may cause nasal congestion, sore throat, and fever[6].

IIV has two types: the trivalent influenza vaccine and the quadrivalent influenza vaccine. Trivalent vaccines include two Influenza A strains (H1N1 and H3N2) and one Influenza B strain, while the quadrivalent vaccine formulation includes an additional Influenza B strain along with the above three strains[6]. The strains included in the vaccines each year depend on the surveillance of circulating strains[7].

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends annual vaccination for all people aged 6 months and older in the United States[8]. The WHO meanwhile limits their recommendation of seasonal influenza vaccination to pregnant women, elderly individuals (>65 years of age), children between 6 months and 5 years of age, healthcare workers, and individuals with chronic medical conditions[2]. Despite such recommendations, seasonal influenza vaccine coverage remains low worldwide.

The influenza vaccine is unique in that it is constantly updated and needs to be taken annually[4]. Hence coverage may be influenced not only by the availability of vaccines but also by past experiences and adverse reactions of previous years[9,10]. In addition, barriers to uptake, including vaccine hesitancy may affect coverage[9].

Individuals are known to behave differently according to age and gender[11,12]. Racial and ethnic differences also affect health behaviors[13]. However, research surrounding influenza vaccine coverage tends to exclude such sociodemographic variables. In this review, we focus on the role and intersection of age, sex, gender, and race/ethnicity on seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance, adverse events, and coverage.

While sex and gender are often used interchangeably, they are two distinct concepts. ‘Sex’ is a construct that defines males and females by biological and physiological characteristics such as the organization of chromosomes, circulating sex steroid hormone concentrations, and reproductive organs[14,15]. This differs from gender, which refers to socially constructed characteristics such as norms, roles, relationships, and behaviors that a given society considers appropriate for women, men, and people with non-binary identities[14,15]. In this paper female/male is used to refer to sex, and woman/man refers to gender.

Given the current climate surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, which is also a contagious respiratory illness, the findings of this review may apply to the COVID vaccines as well. Vaccine acceptance and coverage, and the sociodemographic factors responsible for their differential values, would be of equal importance as public health indicators in limiting the transmission of this novel coronavirus as is the case with the seasonal influenza virus.

2. Methods

We conducted a literature search using the PubMed database. Searches were completed using mesh headings such as ‘Influenza, human’, ‘Influenza vaccines’, and subheadings such as ‘Adverse effects’. Further, we used keywords for the four factors – age, sex, race, and gender to produce search results specific to each of them as described in Table 1. Some of the keywords used included ‘Sex’, ‘Sex difference’, ‘Sex-specific’, ‘Gender’, ‘Gender bias’, ‘Gender discrimination’, ‘Gender inequality’, ‘Gender gap’, ‘Race’, ‘Racial factor’, ‘Ethnicity’, ‘Racial bias’, ‘Age’, ‘Age factor’, ‘Age group’.

Table 1.

Overview of articles

| Vaccine Acceptance | Adverse Reactions | Vaccine Coverage | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 241 | 153 | 267 | 661 |

| Sex | 567 | 500 | 842 | 1909 |

| Race | 189 | 78 | 232 | 499 |

| Gender | 69 | 33 | 78 | 180 |

| Total | 1066 | 764 | 1419 | 3249 |

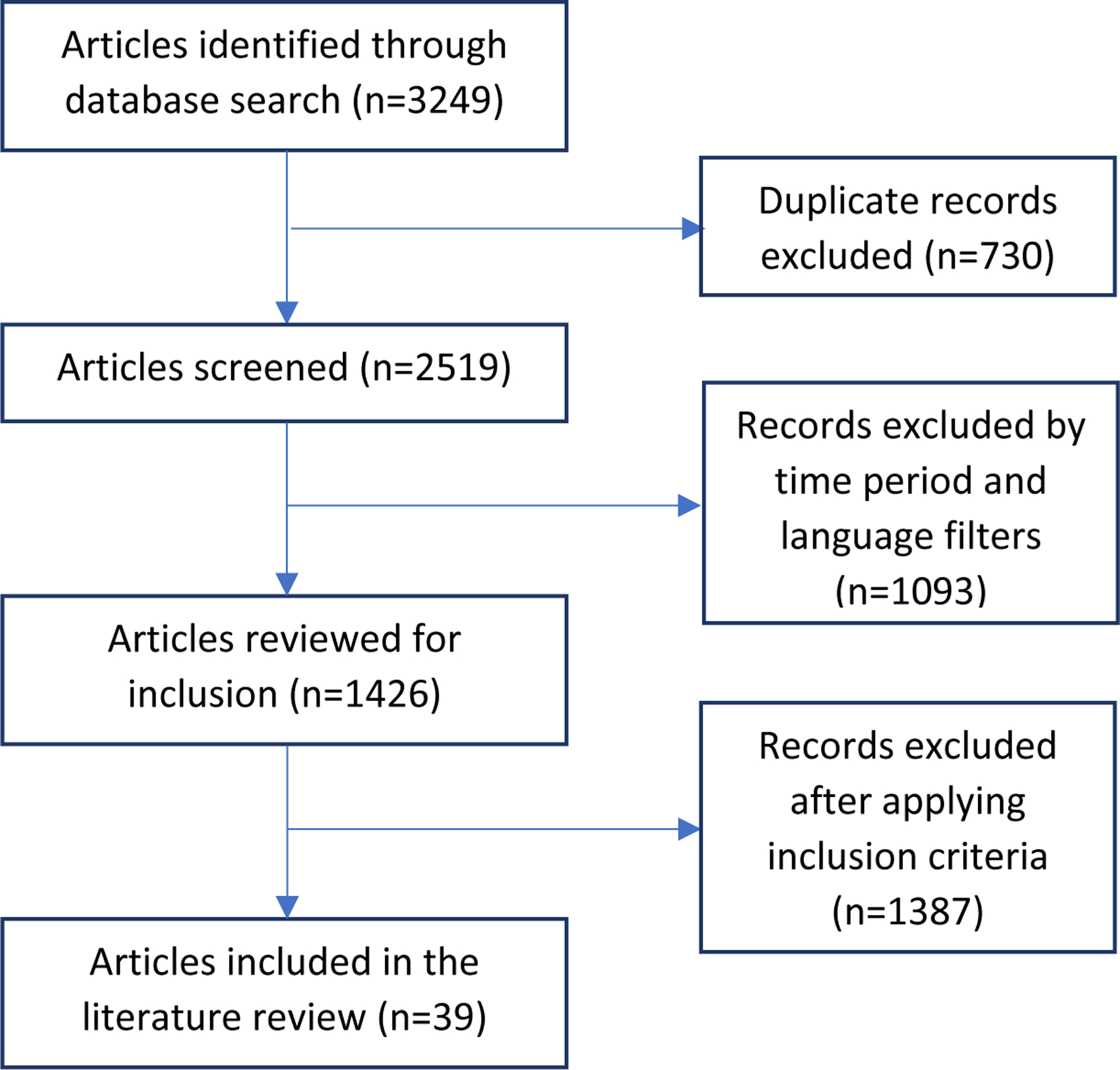

The 3,249 articles obtained from the database search were then reviewed for inclusion as per the criteria outlined in Table 2. The process of article selection through searching, screening, and reviewing is summarized in Figure 1. A total of 39 articles (Table 3) were included in this review after the exclusion of duplicates and those that did not fit pre-defined inclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Selection criteria

| 1. Time period | 2010 onwards |

| 2. Language | English |

| 3. Subject area | Seasonal Influenza Vaccine |

| 4. Themes | Vaccine acceptance, vaccine coverage and adverse events |

| 5. Focus | How sex, race, gender or age affects the above themes |

| 6. Study type | Peer-reviewed primary and secondary research |

| 7. Methods | Qualitative and/or quantitative and/or mixed methods or literature or systematic reviews |

Figure 1.

Schematic Illustration of literature search and study selection

Table 3.

Articles included in the literature review

| Title | Author(s) | Year | Journal | Aim/Objective | Sample | Location | Factor of Interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding and Increasing Influenza Vaccination Acceptance: Insights from a 2016 National Survey of U.S. Adults. | Nowak GJ et. al | 2018 | Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018 Apr 10;15(4). | To assess and identify characteristics, experiences, and beliefs associated with influenza vaccination using a nationally representative survey of 1005 U.S. adults 19 years old and older. | 1005 adults 19 years old and older. | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Attitudes and perceptions among the pediatric health care providers toward influenza vaccination in Qatar: A cross-sectional study | Alhammadi A et. al | 2015 | Vaccine. 2015 Jul 31;33(32):3821–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.082. | To estimate the percentage of vaccinated health care providers at pediatrics department and know their perception and attitudes toward influenza vaccinations using a cross-sectional survey. | 230 pediatrics healthcare professionals | Qatar | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Seasonal influenza: Knowledge, attitude and vaccine uptake among adults with chronic conditions in Italy | Bertoldo G et. al | 2019 | PLoS One. 2019 May 1;14(5):e0215978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215978. | Cross-sectional study aimed at evaluating the knowledge and attitudes concerning influenza vaccination in Southern Italy, and investigating the potential determinants of vaccine uptake. | 700 adults with chronic diseases attending four public specialty clinics. | Italy | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Influenza Vaccination Coverage and Factors Affecting Adherence to Influenza Vaccination Among Patients With Diabetes in Taiwan | Yu MC et. al | 2014 | Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(4):1028–35. doi: 10.4161/hv.27816. | To investigate influenza vaccination coverage and the factors influencing acceptance of influenza vaccination among patients with diabetes in Taiwan using the Health Belief Model (HBM). | 691 diabetes patients aged 40 and above | Taiwan | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Breaking Down the Monolith: Understanding Flu Vaccine Uptake Among African Americans | Quinn SC et. al | 2018 | SSM - Popul Heal. 2018;4:25–36. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.11.003 | Utilizing a nationally-representative 2015 survey of US Black adults to explore differences by gender, age, income, and education across vaccine-related measures and racial factors within the Black population. | 806 Black adults | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Opinion About Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Among the General Population 3 Years After the A(H1N1)pdm2009 Influenza Pandemic | Boiron K et. al | 2015 | Vaccine. 2015 Nov 27;33(48):6849–54. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.067. | To assess the opinions of the French general population about seasonal influenza vaccination three years after the A(H1N1)pdm 09 pandemic and identify factors associated with a neutral or negative opinion about this vaccination using a web-based participative study. | 5374 participants of a web-based study | France | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Motors of influenza vaccination uptake and vaccination advocacy in healthcare workers: A comparative study in six European countries | Kassianos G et. al | 2018 | Vaccine. 2018 Oct 22;36(44):6546–6552. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.031. | To explore the drivers of healthcare workers’ vaccine acceptance and advocacy through a voluntary survey questionnaire in six European countries. | 2476 participant s from Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Kosovo, Poland, Romania, and the United Kingdom | Europe | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Seasonal influenza vaccination among homebound elderly receiving home-based primary care in New York City. | Banach DB et. al | 2012 | J Community Health. 2012 Feb;37(1):10–4. | A cross-sectional analysis of seasonal influenza vaccination coverage and factors associated with vaccine refusal within an urban home-based primary care program. | 689 adults aged 65 and above | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Vaccine Hesitancy in the French Population in 2016, and Its Association With Vaccine Uptake and Perceived Vaccine Risk-Benefit Balance | Rey D et. al | 2018 | Euro Surveill. 2018 Apr;23(17):17–00816. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.17.17-00816. | To estimate the prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of vaccine hesitancy in sub-groups of the French population and to investigate the association of vaccine hesitancy with both vaccine uptake and perceived risk–benefit balance (RBB) for four vaccines using a cross-sectional survey.. | 3938 parents and 2418 elderly people aged 65–75 years | France | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Frequency and Predictors of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Reasons for Refusal Among Patients at a Large Tertiary Referral Hospital | Masnick M, Leekha S | 2015 | Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015 Jul;36(7):841–3. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.56. | To assess frequency and predictors of vaccination acceptance as well as reasons for refusal using data from electronic medical records in an inpatient population over 5 influenza seasons. | 28,371 patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Factors Influencing Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Uptake Among Health Care Workers in an Adult Tertiary Care Hospital in Singapore: A Cross-Sectional Survey | Kyaw WM et. al | 2019 | Am J Infect Control. 2019 Feb;47(2):133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.08.011. | A single-center, cross-sectional survey using a standardized anonymous, self-administered questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes, and uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination. | 3873 healthcare workers | Singapore | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Intention to Receive Influenza Vaccination Prior to the Summer Influenza Season in Adults of Hong Kong, 2015 | Yang L, Cowling BJ, Liao Q | 2015 | Vaccine. 2015 Nov 27;33(48):6525–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.012. | To investigate the intention of Hong Kong adults to get the pre-summer influenza vaccines using a telephone survey. | 539 survey respondants aged 18 and above | Hong Kong | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Missed Opportunity: Why Parents Refuse Influenza Vaccination for Their Hospitalized Children | Cameron MA et. al | 2016 | Hosp Pediatr. 2016 Sep;6(9):507–12. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0219. | To examine reasons for refusal among pediatric patients admitted during influenza season at two suburban network community hospitals. | 325 pediatric patients admitted to two network community hospitals | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Impact of Race on Immunization Status in Long-Term Care Facilities | Barrett SC et. al | 2019 | J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019 Feb;6(1):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s40615-018-0510-1. | To examine the relationship between resident race and immunization status in long-term care facilities. | 2570 resident records of individuals aged 65 and above at 35 long-term care facilities. | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Exploring Racial Influences on Flu Vaccine Attitudes and Behavior: Results of a National Survey of White and African American Adults | Quinn SC et. al | 2017 | Vaccine. 2017 Feb 22;35(8):1167–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.046. | To examine the extent to which racial factors including racial consciousness, fairness, and discrimination may affect vaccine attitudes and behaviors. | 1643 survey respondents aged 18 and above | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Differences in Adult Influenza Vaccine-Seeking Behavior: The Roles of Race and Attitudes | Groom HC et. al | 2014 | J Public Health Manag Pract. Mar-Apr 2014;20(2):246–50. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318298bd88. | To determine whether there are differences between blacks and whites in influenza vaccine-seeking behavior among adults 65 years and older using data from a random digit dialling telephone survey. | 3138 adults aged 65 and above | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Influenza vaccination acceptance among diverse pregnant women and its impact on infant immunization | Frew PM et. al | 2013 | Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Dec;9(12):2591–602. doi: 10.4161/hv.26993. | To examine pregnant women’s likelihood of vaccinating their infants against seasonal influenza via a randomized message framing study. | 261 pregnant women | USA | Vaccine Acceptance |

| Rapid Safety Assessment of a Seasonal Intradermal Trivalent Influenza Vaccine | Demeulemeester M et. al | 2017 | Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017 Apr 3;13(4):889–894. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1253644. | To detect clinically significant increases in allergic events, or in the frequency and/or severity of expected vaccine reactions, and to describe the serious adverse events within 7 d after intradermal influenza vaccination in adults aged 18 y and older enrolled at 6 centers in Belgium (Phase IV study). | 210 participants aged 18 and above | Belgium | Adverse reactions |

| Active surveillance for safety monitoring of seasonal influenza vaccines in Italy, 2015/2016 season. | Spila Alegiani S, Alfonsi V, Appelgren EC, et al. | 2018 | BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1401. Published 2018 Dec 22. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6260-5 | To assess the safety of flu vaccines among population groups for which the seasonal vaccine is recommended in Italy in the 2015–2016 season using a web-based self-administered questionnaire. | 3213 individuals registered on the web-based platform. | Italy | Adverse reactions |

| Immunogenicit y and safety assessment of a trivalent, inactivated split influenza vaccine in Korean children: Double-blind, randomized, active-controlled multicenter phase III clinical trial. | Han SB, Rhim JW, Shin HJ, et al. | 2015 | Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(5):1094–1102. doi:10.1080/21645515.2015.1017693 | To evaluate the immunogenicity and safety of an egg-based, trivalent, inactivated split influenza vaccine in Korean children (Phase III clinical trial). | 405 children between 6 months to 18 years of age | Korea | Adverse reactions |

| Web-based intensive monitoring of adverse events following influenza vaccination in general practice. | van Balveren-Slingerland et. al | 2015 | Vaccine. 2015 May 5;33(19):2283–2288. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.014. | To evaluate the feasibility and contribution of the LIM system(a non-interventional prospective observational cohort study that follows users of certain drugs during a period of time, collecting information through web-based questionnaires) to provide insight into the pattern, time course, risk factors and impact of adverse effects after influenza vaccination. | 1367 patients who responded to the questionnaire | Netherlands | Adverse reactions |

| Active surveillance of 2017 seasonal influenza vaccine safety: an observational cohort study of individuals aged 6 months and older in Australia. | Pillsbury AJ, Glover C, Jacoby P, et al. | 2018 | BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e023263. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023263 | To actively solicit adverse events experienced in the days following immunisation with quadrivalent inactivated influenza vaccine using Australia’s near real-time, participant-based vaccine safety surveillance system, AusVaxSafety. | 73,892 survey respondents | Australia | Adverse reactions |

| A retrospective survey of the safety of trivalent influenza vaccine among adults working in healthcare settings in south metropolitan Perth, Western Australia, in 2010 | Suzanne McEvoy | 2012 | Vaccine. 2012 Apr 5;30(17):2801–4. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.001. | To examine side effects following vaccination and subsequent significant respiratory illnesses during the influenza season using an electronic survey questionnaire.. | 2245 survey respondents | Australia | Adverse reactions |

| Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent intradermal influenza vaccine in adults. | Gorse et. al | 2015 | Vaccine. 2015 Feb 25;33(9):1151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.025. | To examine whether adding a second B-lineage strain affects immunogenicity and safety (Phase III trial). | 3360 participants aged 18 and above | USA | Adverse reactions |

| Tolerability of 2 Doses of Pandemic Influenza Vaccine (Focetria®) and of a Prior Dose of Seasonal 2009–2010 Influenza Vaccination in the Netherlands | van der Maas et. al | 2016 | Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016 Apr 2;12(4):1027–32. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1120394. | To assess tolerability of seasonal influenza vaccination and 2 doses of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) vaccine, adjuvanted with MF-59, administered 2 and 5 weeks after seasonal 2009–2010 vaccination among adults using questionnaires. | 1962 participants receiving seasonal influenza vaccine | Netherlands | Adverse reactions |

| Association between seasonal influenza vaccination with pre- and postnatal outcomes | Getahun et. al | 2019 | Public Health. 2018 May;158:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.01.030 | To examine the extent to which influenza vaccine safety is affected by timing of vaccination, maternal race/ethnicity and the type of vaccine and its effects on other outcomes using a large retrospective cohort. | 247,036 pregnant women | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Workplace availability, risk group and perceived barriers predictive of 2016–17 influenza vaccine uptake in the United States: A cross-sectional study | Luz PM, Johnson RE, Brown HE | 2017 | Vaccine. 2017 Oct 13;35(43):5890–5896. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.078 | To explore socio-demographic, economic, and psychological factors that explain vaccine uptake using a cross-sectional study. | 1007 survey respondents aged 18 and above | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Determinants of non-vaccination against seasonal influenza. | Roy M et. al | 2018 | Health Reports, Vol. 29, no. 10, pp. 12–22 | To identify the determinants of, and the reasons for, non-vaccination using a cross-sectional study. | 108,700 survey respondents | Canada | Vaccine Coverage |

| Why are older adults and individuals with underlying chronic diseases in Germany not vaccinated against flu? A population-based study. | Bodeker B et. al | 2015 | BMC Public Health. 2015 Jul 7;15:618. | To estimate influenza vaccination uptake for the 2012/13 and 2013/14 seasons, assess knowledge and attitudes about influenza vaccination, and identify factors associated with vaccination uptake in two risk groups using a cross-sectional survey. | 1519 survey respondents aged 18 and above | Germany | Vaccine Coverage |

| Low vaccination coverage for seasonal influenza and pneumococcal disease among adults at-risk and health care workers in Ireland, 2013: The key role of GPs in recommending vaccination. | Giese C et. Al | 2016 | Vaccine. 2016 Jul 12;34(32):3657–62. | To estimate size and vaccination coverage of at-risk groups, and identify predictive factors for influenza vaccination using a telephone survey. | 1770 Irish residents ≥18 years of age | Ireland | Vaccine Coverage |

| Coverage and predictors of vaccination against 2012/13 seasonal influenza in Madrid, Spain: analysis of population-based computerized immunization registries and clinical records. | Jimenez-Garcia R et. al | 2014 | Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(2): 449–55. | To determine 2012–13 seasonal influenza vaccination coverage and to analyse a possible trend in vaccine uptake in post pandemic season using clinical records. | 6,284,128 individuals with computerized primary care records | Spain | Vaccine Coverage |

| The Impact of Influenza Vaccinations on the Adverse Effects and Hospitalization Rate in the Elderly: A National Based Study in an Asian Country | Tsung-yu Ho et. Al | 2012 | PLoS One. 2012; 7(11): e50337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050337 | Retrospective cohort study to examine the risk of adverse effects of special interest in persons vaccinated against seasonal influenza compared with unvaccinated persons aged 65 and above using the National Health Insurance database. | 93,049 adults aged 65 and above | Taiwan | Vaccine Coverage |

| Reasons for and against receiving influenza vaccination in a working age population in Japan: a national cross-sectional study. | Iwasa T, Wada K | 2013 | BMC Public Health. 2013 Jul 12;13:647. | To determine influenza vaccination coverage in Japan and reasons for receiving the vaccine or not using a web-survey. | 3129 survey respondents aged 20 and above | Japan | Vaccine Coverage |

| Perceptions matter: beliefs about influenza vaccine and vaccination behavior among elderly white, black and Hispanic Americans. | Wooten KG et. al | 2012 | Vaccine. 2012 Nov 6;30(48):6927–34. | To identify associations between vaccination behavior and personal beliefs about influenza vaccine by race or ethnicity and education levels among the U.S. elderly population using a telephone survey. | 3875 adults ≥65 years of age | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Influenza vaccination for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Implications for pharmacists. | Arabyat RM, Raisch DW, Bakhireva L | 2018 | Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018 Feb;14(2):162–169. | To determine the recent influenza vaccination coverage among patients with COPD, identify factors that were associated with immunization, and interpret the results based upon Andersen’s healthcare utilization model. | 36,433 individuals aged 25 years and older with COPD | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Influenza Vaccination among Adults with Chronic Medical Conditions Vary by Age in the United States | Lu D et. al | 2017 | PLoS One. 2017 Jan 12;12(1):e0169679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169679. | To study if racial and ethnic disparities in relation to influenza vaccination are present in adults suffering from at least one chronic condition and if such inequalities differ between age groups. | 15,499 adults living with at least one chronic health condition | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among women with live-born infants: PRAMS surveillance during the 2009–2010 influenza season. | Ahluwalia IB et. al | 2014 | Public Health Rep. 2014 Sep-Oct;129(5):408–16. | To examine disparities in vaccination coverage among women who delivered a live-born infant during the 2009–2010 influenza season, using Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) data. | 27,153 pregnant women in 29 states and New York City in the USA | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women. | Henninger ML et. al | 2015 | J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015 May;24(5):394–402. | Observational study following a cohort of pregnant women during the 2010–2011 influenza season to determine factors associated with vaccination. | 1105 pregnant women who completed the survey | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

| Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women--United States, 2014–15 Influenza Season. | Ding et. al | 2015 | MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015 Sep 18;64(36):1000–5. doi: 10.3201/mmwr.mm6436a2 | Utilizing an internet panel survey to provide end-of-season estimates of influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women; to assess respondent-reported provider recommendation for and offer of influenza vaccination; and to obtain updated information on pregnant women’s knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to influenza vaccination. | 1702 pregnant women who completed the survey | USA | Vaccine Coverage |

3. Results

3.1. Vaccine Acceptance

Vaccine acceptance is the likelihood of an individual accepting a vaccine when there is an opportunity to be vaccinated. A complementary concept related to acceptance is that of vaccine hesitancy. WHO describes vaccine hesitancy as a complex model where “hesitant individuals may accept all vaccines but remain concerned about vaccines, may refuse or delay some vaccines but accept others or may refuse all vaccines”[16].

Various factors may influence an individual’s decision to accept a particular vaccine or not; and this decision may change from one stage in life to another or even from one season to the next. Whether a country recommends the seasonal influenza vaccine or not, and who these recommendations are directed towards, might affect acceptance, and possibly coverage in that region. However, in this section, we look specifically at how sociodemographic factors influence an individual’s decision relating to the acceptance of the seasonal influenza vaccine.

3.1.1. Age

Using data from a nationally representative survey of 1005 U.S. Adults, Nowak et al. reported that 14.2% of respondents in the 19–30 year age group stated that they would ‘definitely get the vaccine’ in the 2016–17 season as opposed to 21%, 33.7%, and 40.2% respectively in the 31–49, 50–64, and 65+ age groups[17].

In 2013, in a study among 230 pediatric healthcare providers (HCP) divided into <40 and >40 age groups in Qatar, Alhammadi et al. evaluated willingness to get vaccinated against influenza. They observed a statistically significant difference between the groups with 67% of respondents willing to take the vaccine in the older age group as opposed to 41% in the younger age group[18]. Similar results were reported by Bertoldo et al. among 700 adults with chronic diseases at four clinics in Italy. Individuals in the 18–49 and the 50–64 year groups were about 70% less likely to accept the influenza vaccine than their older (≥ 65 years) counterparts[19].

A study conducted using the health belief model (a theoretical model that predicts individual health behaviors and decision-making related to issues of health[20]) among 691 diabetic patients in Taiwan found that individuals ≥ 65 years of age were more than seven times as likely to accept the seasonal influenza vaccine as compared to those 40–64 years of age[21]. Quinn et al. examined flu vaccine hesitancy in 806 non-Hispanic, African American adults in the United States and found the highest hesitancy rate in the 18–29 year age group, with a gradual decrease in hesitancy by age up to the 60+ age group[22].

A study of 5374 individuals in France sought opinions regarding seasonal influenza vaccination in 2012 – they observed that young adults aged 18–35 years were about 30% less likely to have positive vaccine opinions than 35–50 year old individuals and about 70% less likely than adults ≥ 65 years[23]. Similarly, a study of 2476 healthcare workers from six European countries found older individuals to be more likely to view the influenza vaccine positively[24].

Banach et al. examined seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance among 689 elderly persons >65 years of age in New York City. Age was not significantly associated with the outcome of vaccine acceptance in this older adult population[25]. Similarly, in France, Rey et al. observed no differences in vaccine hesitancy between the 65–69 and 70–75 year age groups among 2418 survey takers in their study[26].

3.1.2. Gender

A study evaluating influenza vaccine acceptance among 689 homebound elderly adults receiving home-based primary care in New York City found that women >65 years of age were twice as likely to refuse vaccination as compared to men in the same age group[25]. Similar results were reported in a study focused on 806 non-Hispanic, African American adults, in which women were more likely to be vaccine-hesitant than men[22]. Masnick and Leekha also reported women as having lower odds (OR=0.85) for vaccine acceptance in 28,371 patients hospitalized at a tertiary referral hospital in the US across five influenza seasons from 2008–13[27].

In Qatar, among questionnaires distributed to 230 healthcare providers in a tertiary teaching hospital, no significant difference was observed by gender in willingness to accept the seasonal influenza vaccine[18]. Similarly, Kyaw et al. found no significant difference by gender among 3873 healthcare workers (HCW) with regards to influenza vaccine acceptance in a cross-sectional survey study at a hospital in Singapore in 2016[28].

Yu et al. reported results from a questionnaire-based study on 691 diabetics in Taiwan in 2012. They observed men to be significantly less likely (OR=0.58) to accept influenza vaccination[21]. Conversely, in a study of pre-summer vaccination intentions among 539 survey respondants aged 18 and above in Hong Kong in 2015, men were found to be twice as likely as women to have vaccination intentions[29].

Using data from a national cross-sectional telephone survey ‘Health Barometer’ in France in 2016, Rey et al. observed three groups – parents of children aged 1–15 years, parents of girls aged 11–15 years, and 65–75-year-olds[26]. Women were found to have 20–60% higher rates of vaccine hesitancy as compared to men; with the highest difference (OR=1.6) observed amongst parents of 11–15-year-old girls[26]. A study of 325 admitted children aged 6 months to 18 years at two network community hospitals in the US found parents of girl children to be more likely to decline the influenza vaccine, although this was not significant upon multivariable analysis[30].

3.1.3. Race and Ethnicity

A study looking at residents in 35 long-term care facilities in the United States over two consecutive influenza seasons from 2010–2012 found that Black residents were more likely to refuse vaccination across both seasons, with significantly higher levels of vaccine refusal as opposed to White residents in the 2011–12 influenza season[31]. Similarly, a study using data from 1643 respondents of an online, nationally representative survey in the US found African Americans were significantly more likely to be vaccine-hesitant in general and specifically flu vaccine-hesitant compared to White respondents[32].

Banach et al. observed 689 homebound African American elderly (>65 years) individuals receiving primary care at home; and found them to be more than twice as likely to refuse the seasonal influenza vaccine as their non-African American counterparts[25]. Similarly, Groom et. al reported Black individuals aged 65 and above as less likely to seek the seasonal vaccine as opposed to their White counterparts from a national sample of 3138 older adults[33].

In a 2016 National Survey of 1005 U.S. Adults, 18.2% of Hispanic adults said they would ‘definitely get the flu vaccine that season’ as opposed to 27.6% non-Hispanic White and 31.1% non-Hispanic Black adults[17]. Conversely, 37% Hispanic, 24.8% non-Hispanic White and 24.4% non-Hispanic Black adults said they would ‘definitely not get the seasonal flu vaccine’. With regards to having declined flu vaccinations in the past, non-Hispanic Whites and Hispanics were more likely to have declined a flu vaccine[17].

Frew et al. reported results of 261 pregnant women from racial and ethnic minorities in Atlanta, Georgia[34]. Race was not found to be a significant factor in the intention of minority pregnant women to immunize their infant after 6 months of age[34]. Among 325 children <18 years admitted in two community hospitals in the United States, Cameron et al. reported that parents of children of African American and other races were more likely to accept the seasonal influenza vaccine than their White counterparts, although this difference was only significant for those whose race was described as ‘Other’[30].

3.1.4. Summary

Vaccine acceptance was found to increase with increasing age, was higher among men; and by race, was highest among white individuals. Thus, elderly white men >65 years of age were found to have highest rates of seasonal influenza vaccine acceptance. Some of the reasons for such results are explored in the discussion section below.

3.2. Adverse Reactions

Adverse effects of the flu vaccine are generally mild and may resolve without medical help[35]. Some common injection site reactions include soreness, pain, redness, and inflammation whereas systemic reactions like fever, headache, nausea, and myalgia may also occur[35]. We looked at published literature to evaluate differential experiences of adverse events by sociodemographic characteristics following receipt of the seasonal influenza vaccine.

3.2.1. Age

In a 2014 study of 210 participants, Demeulemeester et al. found 78% of participants in the 18–59 year age group reported an injection site reaction as opposed to 54% in the ≥ 60-year group[36]. The most commonly reported reactions were pain, erythema, and pruritis. Systemic reactions (headache, myalgia etc.) were also more likely to occur in the younger age group (60%) when compared to older adult participants (32%)[36]. Unsolicited adverse events were found to be infrequent and mild to moderate in both age groups.

Alegiani et al. evaluated self-reported adverse events from 3213 individuals who received the seasonal influenza vaccine in Italy in 2015/16[37]. After adjusting for other factors, the highest rate of adverse events was observed in the <14-year age group (OR=3.80) followed by the 15–25-year group (OR=3.26). Both these groups were found to be more than three times as likely to report side effects as compared to the reference group, individuals ≥ 80 years of age[37]. Reported adverse events were also higher in the 26–65 year group (OR=2.45) and the 66–79 year group (OR=1.51) when compared to individuals aged 80 and above[37].

In a study of a trivalent IIV among 405 children in Korea, adverse events were found to occur in 66.2% of children age <3 years, 73.8% in the 3–9 years age group, and 67.1% of the children >9 years of age[38]. Tenderness was the most common local adverse reaction and malaise the most common general reaction[38]. In the Netherlands, a web-based evaluation of post-vaccination side effects among 1367 patients found persons younger than 60 years of age to be almost three times as likely as older (>60 years) individuals to experience side effects[39].

Pillsbury et. al conducted a safety monitoring study among 73,892 participants in Australia in 2017 using a near real-time safety surveillance system. Children aged 6 months to 4 years (8.4%) were found to be most likely to suffer adverse events and persons greater than 65 years of age (6.0%) were the least likely[40]. The percentage of individuals that reported adverse events in the 5–14, 15–39, and 40–64 year age groups were 6.7%, 6.2%, and 7.1% respectively[40].

3.2.2. Sex/gender

An active surveillance study among 3213 individuals in Italy in the 2015–16 season found females to be more likely (OR = 1.51) than males to experience adverse events from the seasonal influenza vaccine [37]. This was consistent with findings reported in a retrospective safety study conducted among 2245 hospital sector employees in Western Australia where females were 1.64 times as likely to report side effects as males[41]. Soreness, swelling, and redness were the most common local side effects while flu-like illness, headache, and sore throat, were the most reported systemic events[41].

Van Balveren-Slingerland et al. reported females to be more than twice as likely to experience adverse effects as males in their web-based monitoring study of 1367 patients in the Netherlands[39]. Common side effects included injection site inflammation, headache, and myalgia[39]. During the 2012–2013 influenza season, Gorse et al. reported a generally higher percentage of study subjects reporting adverse effects among females as compared to males[42]. Similarly, a questionnaire-based study among 1962 respondents in the Netherlands, found the frequency of reported local, as well as systemic adverse events, statistically significantly higher in females as compared to males[43].

3.2.3. Race and ethnicity

Getahun et al. analyzed records for 247,036 pregnant females from the Kaiser Permanente system between 2008 and 2016. They observed no significant differences in pre and post-natal adverse events from seasonal influenza vaccine across all races/ethnicities[44].

3.2.4. Summary

Adverse events were found to be more frequently reported in young adults as opposed to elderly individuals across studies. Reporting was also found to be consistently higher among females for all age groups in this review. Literature surrounding adverse reactions by race was scant; hence, conclusions could not be drawn in this regard.

3.3. Vaccine Coverage

Vaccine coverage refers to the percentage of people in a given population who have received a specific vaccine[45]. Public health surveillance and monitoring activities use coverage as an indicator of the extent to which areas and communities may be protected from certain vaccine-preventable diseases such as influenza[45]. This section reports on seasonal influenza vaccine coverage rates by age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity. However, not all studies disaggregated their data by these socio-demographic factors, and few used intersectional data (i.e., gender and race combined). When intersectional data was available, we present it below.

3.3.1. Age

Nowak GJ et al. used a nationally representative survey of 1005 US adults to describe influenza vaccine coverage rates in 2016[17]. By age, 20.5% of adults in the 19–30 year age group received the vaccine compared to 33.7% in the 31–49 year age group, 51.5% in the 50–64 year group, and 66.7% in adults ≥65 years of age[17]. In a survey of 1007 participants, also conducted in the United States, reported vaccine coverage was 31% in the 18–64 year age group, and 52.4% for individuals above 65 years of age[46].

Roy M et al. looked at data from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) for the 2013/14 influenza season[47]. A total of 108,700 adults were analyzed by two age groups:18–64 years and ≥65 years. Vaccination coverage was found to be significantly lower in 18–64 year-olds compared to those over 65 years of age[47]. A closer examination of the 18–64 year group by dividing into three subgroups revealed vaccine coverage increased with age[47].

A study of 1519 survey respondents in Germany reported seasonal influenza vaccine coverage to increase with age and peak among the 70–79 year age group for the 2012/13 and 2013/14 seasons[48]. In Ireland, Giese et al. contacted 1770 individuals aged 18 years and older through a national telephone survey in 2013. They found that vaccine coverage was 60% among those above 65 years of age as opposed to 28% in the 18–64 year age group[49].

Jimenez-Garcia et al. looked at data from 6,284,128 individuals with computerized primary care records for the 2012–13 seasonal influenza campaign in Spain. They found increasing age to be associated with greater coverage, however, there were also gender differences as described below[50]. Similarly, in Taiwan, a retrospective cohort study of 93,049 individuals found that age and gender were significantly associated to coverage; with older men having greater seasonal influenza vaccine coverage in the 2008/09 season[51].

3.3.2. Sex/gender

A survey of 1007 participants conducted in the United States reported women as being about 20% more likely to receive the influenza vaccine compared to men, although this was not statistically significant upon multivariable regression analysis[46]. Roy M et al. used data of 108,700 adults from the CCHS for the 2013/14 influenza season; while there was no significant difference by sex/gender in the above 65 age group, younger women were more likely to be vaccinated than younger men[47].

Bodeker et. al reported women were significantly more likely than men to receive the vaccine in 2013/14 in Germany, but there was no difference in coverage by gender in the previous season[48]. In Japan, an internet-based survey with 3129 respondents found that vaccination was higher among women as opposed to men for every age group (except 40–49 years) during the 2011 influenza season, although this difference was not statistically significant[52]. Similarly, in Ireland, Giese et al. found no significant differences by sex/gender in seasonal influenza vaccination coverage of 1770 survey respondents in 2013[49].

Jimenez-Garcia et al. looked at data from 6,284,128 individuals for the 2012–13 seasonal influenza campaign in Spain. They found that women had lower vaccine receipt in the ≥60 age group, but higher coverage in the 15–59 year age group – indicating that young men and older women were least likely to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine[50].

3.3.3. Race and ethnicity

A nationally representative survey of 1005 adults for the 2015–16 season in the US found coverage among Hispanic adults (20.8%) was lower compared to Non-Hispanic White adults (45.4%) and Non-Hispanic Black adults (50.9%)[17]. In a telephone survey, conducted among 3875 adults ≥65 years of age in the United States, vaccine coverage was found to be higher among White (Ref.) than Black (OR=0.39) or Hispanic (OR=0.38) populations after adjusting for all other demographic variables[53].

Using data from the 2012 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) - a system of telephone surveys collecting information regarding the use of preventive services, health-related risk behaviors, and chronic health conditions[54], Arabyat et al. identified 36,433 respondents >25 years of age with Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). They found that both Black (OR=0.72) and Hispanic (OR=0.78) adults were significantly less likely to be vaccinated than their White peers in this sample[55].

Lu et al. used the 2011–12 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to study racial differences in vaccine coverage among 15,499 US adults who had a chronic health condition. They observed lower seasonal influenza vaccine receipt in Black (48.54%) and Hispanic (48.65%) individuals as compared to White (59.93%) adults[56]. When broken down by age, vaccine receipt was lower among racial minorities in the 50–64 years and > 65 years age groups; there was, however, no difference observed between White and minority populations in the 18–49 year age group[56].

Ahluwalia et al. looked at seasonal influenza coverage among 27,153 pregnant women in 29 states and New York City in the USA in 2009–2010[57]. Overall vaccine coverage was 30.2% in Non-Hispanic Black women as compared to 50.5% in Non-Hispanic White women. There was no significant difference between the reference group (non-Hispanic White women) and other groups (Hispanics, non-Hispanic others)[57]. In the following (2010–11) season, 1105 participants were enrolled in a prospective cohort study of pregnant women at Kaiser Permanente North West and Kaiser Permanente Northern California[58]; Black women were again significantly less likely (OR=0.37) to have received the seasonal influenza vaccine compared to White women[58].

Ding et al. also observed seasonal influenza coverage to be lower among Black pregnant women in the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 seasons compared to White and Hispanic pregnant women[59]. Similar results were reported among 247,036 pregnant women by Getahun et al. using vaccination records from Kaiser Permanente (2008–2016)[44], in which younger women and Black women were least likely to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine[44].

3.3.4. Summary

Age was found to be directly related to vaccine coverage; with coverage rates increasing by age in every study. Similarly, White persons and women were found to be more likely to receive the seasonal influenza vaccine by race and gender respectively. These disparities in influenza vaccine coverage are further discussed in the following section.

4. Discussion

Although most countries are far from achieving their targets for seasonal influenza vaccine coverage, the results of this review indicate that certain groups and sub-populations are differentially impacted in terms of vaccine acceptance, adverse reactions, and vaccine coverage.

By age, multiple studies reported greater vaccine acceptance and coverage among older adults[17–19,21–24,46–51]. This is partly explained by the fact that older adults are more likely to visit a physician due to chronic illness or have a routine medical exam in any given year[17]. Another potential reason is that young individuals often do not consider themselves to be at risk of contracting influenza[47], whereas elderly individuals are more likely to have suffered from a severe bout of flu in the past, leading to a belief that they would benefit from getting vaccinated[17,22]. In addition, older adults were more likely to be informed and aware of the recommendation to receive the seasonal vaccine each year - suggesting that young people are either not being reached by influenza recommendations or that they ignore such information[17].

Immunization policies too play a role in age-related disparities in coverage and acceptance. For instance, in Taiwan, free influenza vaccination is provided for individuals aged 65 years and older, which is one of the main reasons for higher coverage and acceptance in this age group in the region[21]. Further, older individuals are often part of a high-risk group for whom vaccines are ‘highly recommended’ – which in turn results in greater acceptance and coverage in this group[46]. This highlights the need for interventions aimed at target groups. For example, vaccination opportunities outside of hospitals and physician visits such as at places of employment and universities are strategies that may be used to target young adults. With regards to adverse events, younger individuals were found to have a higher frequency of reported events[36,37,39,40], with the most likely explanation being pre-existing antibodies in older adults[39], although lack of reporting by older adults due to unfamiliarity with survey instruments has also been reported in previous studies[37].

Gender was found to be a significant predictor of influenza vaccine acceptance with men more likely to accept the vaccine than women[22,25–27,29]. A study among children in France postulated that mothers were more vaccine-hesitant than fathers as they were involved to a greater extent in the medical follow-up of their children[26]. However, despite lower acceptance among women, our findings show that vaccine coverage may be higher in women than men[46,48,52]. Roy et al. stated that this might be as a result of women using preventive healthcare services and visiting physicians more frequently than men[47].

A combination of results surrounding age and gender shows that young women are least likely to accept the seasonal influenza vaccine whereas young men have the lowest coverage. Such intersectionality of sociodemographic data enables us to understand priority groups for public health interventions to reduce barriers to vaccination.

With regards to race and ethnicity, Black and Hispanic adults were found to have lower influenza vaccine acceptance and coverage across studies[17,25,31–33,44,53,55–59]. The United States provides an interesting case study in which to explore potential racial differences, due to the disparities in vaccination rates between Black and White adults. Despite the availability of free and low-cost influenza vaccines in the United States and recommendation from the CDC that adults receive the influenza vaccine each year[60], it is estimated that only 32% of Black adults compared to 40% of White adults received the vaccine in the 2017–2018 flu season[61]. According to CDC data, these disparities have remained consistent since the 2010–2011 season when data disaggregated by race were first reported. As per available evidence, reasons for this disparity include differences in barriers to healthcare access, missed opportunities for vaccination, attitudes and beliefs, perceived risks, experiences of racism within the healthcare system, and socio-economic status[22,32,62–64]. These disparities are concerning as mortality rates due to influenza among Black adults are higher compared to White adults, likely due to higher prevalence of chronic conditions in marginalized communities which increases susceptibility to infection and severe disease[62,63].

In addition, disparities in influenza vaccination coverage between pregnant women and the general population and between pregnant women of different racial/ethnic groups exist. This is of concern as Black pregnant women have persistently higher rates of hospitalizations, morbidity, and mortality due to influenza[65]. Despite this, there is a lack of evidence exploring influenza vaccine acceptance and uptake among pregnant Black women.

Studies that explore influenza vaccine behavior among Black and White adults rarely disaggregate their data by sex/gender[22,32,60,62,63], while studies that explore sex or gender differences in influenza vaccine behavior rarely disaggregate their data by other social stratifiers, including race[26,66,67]. Thus, little is known about how sex/gender and race intersect to affect an individual’s attitudes toward and uptake of influenza vaccines. Due to the differences reported in the above studies between Black and White adults and between women and men in general, vaccine acceptance and access among Black women is likely different than that of Black men or their White counterparts.

This review is the first to look at three different aspects of the seasonal influenza vaccine: acceptance, adverse events and coverage by multiple socio-demographic characteristics – age, sex, gender and race across various geographical contexts. To our knowledge there hasn’t been a comprehensive review as wide-ranging with regards to socio-demographic variables and the seasonal influenza vaccine. Hence, we believe, the disparities this review brings to light, will help create awareness around the associations of sociodemographic characteristics and vaccines, which we hope can aid the development of more effective strategies to reach high-risk individuals and target groups.

4.1. Limitations

The findings of this review should be considered in light of some limitations. Due to resource constraints, only articles available on the PubMed database and published in the English language were included. We accept this might limit the availability of information and generalizability of findings; and acknowledge the need for further research to gain a holistic understanding of sociodemographic characteristic-related differences for the influenza vaccine.

Considering the continually evolving nature of the influenza virus, the seasonal vaccine, surrounding policies, and associated recommendations, we chose to only include literature published in the decade prior to this review. We believe a period of 10 years is ideal for putting forth comments from scientific literature related to our objectives. As the last known influenza pandemic (H1N1 ‘swine flu’ pandemic of 2009) occurred before this 10-year period, we also chose to exclude studies focusing on pandemic vaccines.

We acknowledge that variables such as education, employment, socio-economic status, neighborhood of residence, and others might influence some of the results reported in this review and such variables need to be included to address the gaps of this review for future research.

4.2. Conclusion

Age, sex, gender, and race are prominent sociodemographic characteristics pertaining to vaccines. The 39 studies evaluated in this review had higher rates of vaccine acceptance and coverage in older adults and elderly individuals. However, while acceptance was more likely in older men, coverage was higher among older women. By race, African American individuals had consistently lower vaccine acceptance as well as coverage. Adverse events were found to be most frequently reported by females and younger individuals. This review emphasizes how sociodemographic variables may affect levels of vaccine acceptance and adverse events, which, in turn, sheds light on disparities in seasonal influenza vaccine coverage.

Highlights.

Seasonal influenza vaccine coverage is highest in women, white and older individuals.

Influenza vaccine acceptance increases with age, is higher in white persons by race and men by gender.

Adverse events are most common in young females.

Elderly white men were found to have the best scores across the three parameters, while young women belonging to racial minorities performed the worst.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH/ORWH/NIA Specialized Center of Research Excellence in Sex Differences U54AG062333.

All authors attest they meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World Health Organization

- IIV

Inactivated influenza vaccine

- LAIV

Live attenuated influenza vaccine

- HCP

Healthcare provider

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- HCW

Healthcare worker

- CCHS

Canadian Community Health Survey

- BRFSS

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Key Facts About Influenza (Flu) | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/keyfacts.htm (accessed June 10, 2020).

- [2].Influenza (Seasonal) n.d. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed June 16, 2020).

- [3].Types of Influenza Viruses | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm (accessed June 16, 2020).

- [4].How the Flu Virus Can Change: “Drift” and “Shift” | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/change.htm (accessed August 28, 2020).

- [5].WHO/Europe | Types of seasonal influenza vaccine n.d. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/vaccination/types-of-seasonal-influenza-vaccine (accessed July 22, 2020).

- [6].Different Types of Flu Vaccines | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/different-flu-vaccines.htm (accessed July 11, 2020).

- [7].Seasonal Flu Shot | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/flushot.htm (accessed August 1, 2020).

- [8].Who Should and Who Should NOT get a Flu Vaccine | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/whoshouldvax.htm (accessed August 13, 2020).

- [9].WHO/Europe | Influenza vaccination coverage and effectiveness n.d. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/vaccination/influenza-vaccination-coverage-and-effectiveness (accessed August 12, 2020).

- [10].Flu Vaccination Coverage, United States, 2018–19 Influenza Season | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm (accessed August 24, 2020).

- [11].Shi L. Sociodemographic characteristics and individual health behaviors. South Med J 1998;91:933–41. 10.1097/00007611-199810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Uitenbroek DG, Kerekovska A, Festchieva N. Health lifestyle behaviour and socio-demographic characteristics. A study of Varna, Glasgow and Edinburgh. Soc Sci Med 1996;43:367–77. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00399-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dubowitz T, Heron M, Basurto-Davila R, Bird CE, Lurie N, Escarce JJ. Racial/ethnic differences in US health behaviors: a decomposition analysis. Am J Health Behav 2011;35:290–304. 10.5993/ajhb.35.3.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].WHO | Glossary of terms and tools n.d. https://www.who.int/gender-equity-rights/knowledge/glossary/en/ (accessed September 11, 2020).

- [15].Morgan R, Klein SL. The intersection of sex and gender in the treatment of influenza HHS Public Access 2019;35:35–41. 10.1016/j.coviro.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].What Influences Vaccine Acceptance: A Model of Determinants of Vaccine Hesitancy.; 2013. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2013/april/1_Model_analyze_driversofvaccineConfidence_22_March.pdf Accessed May 12, 2020.

- [17].Nowak GJ, Cacciatore MA, Len-Ríos ME. Understanding and Increasing Influenza Vaccination Acceptance: Insights from a 2016 National Survey of U.S. Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. 10.3390/ijerph15040711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Alhammadi A, Khalifa M, Abdulrahman H, Almuslemani E, Alhothi A, Janahi M. Attitudes and perceptions among the pediatric health care providers toward influenza vaccination in Qatar: A cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2015;33:3821–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bertoldo G, Pesce A, Pepe A, Pelullo CP, Di Giuseppe G. Seasonal influenza: Knowledge, attitude and vaccine uptake among adults with chronic conditions in Italy. PLoS One 2019;14. 10.1371/journal.pone.0215978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Orbell S, Schneider H, Esbitt S, Gonzalez JS, Gonzalez JS, Shreck E, et al. Health Beliefs/Health Belief Model. Encycl. Behav. Med, Springer; New York; 2013, p. 907–8. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_1227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yu MC, Chou YL, Lee PL, Yang YC, Chen KT. Influenza vaccination coverage and factors affecting adherence to influenza vaccination among patients with diabetes in Taiwan. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2014;10:1028–35. 10.4161/hv.27816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Quinn SC, Jamison A, An J, Freimuth VS, Hancock GR, Musa D. Breaking down the monolith: Understanding flu vaccine uptake among African Americans. SSM - Popul Heal 2018;4:25–36. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Boiron K, Sarazin M, Debin M, Raude J, Rossignol L, Guerrisi C, et al. Opinion about seasonal influenza vaccination among the general population 3 years after the A(H1N1)pdm2009 influenza pandemic. Vaccine 2015;33:6849–54. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kassianos G, Kuchar E, Nitsch-Osuch A, Kyncl J, Galev A, Humolli I, et al. Motors of influenza vaccination uptake and vaccination advocacy in healthcare workers: A comparative study in six European countries. Vaccine 2018;36:6546–52. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Banach DB, Ornstein K, Factor SH, Soriano TA. Seasonal influenza vaccination among homebound elderly receiving home-based primary care in New York City. J Community Health 2012. 10.1007/s10900-011-9409-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rey D, Fressard L, Cortaredona S, Bocquier A, Gautier A, Peretti-Watel P, et al. Vaccine hesitancy in the French population in 2016, and its association with vaccine uptake and perceived vaccine risk–benefit balance. Eurosurveillance 2018;23. 10.2807/1560-7917.es.2018.23.17.17-00816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Masnick M, Leekha S. Frequency and Predictors of Seasonal Influenza Vaccination and Reasons for Refusal among Patients at a Large Tertiary Referral Hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015;36:841–3. 10.1017/ice.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kyaw WM, Chow A, Hein AA, Lee LT, Leo YS, Ho HJ. Factors influencing seasonal influenza vaccination uptake among health care workers in an adult tertiary care hospital in Singapore: A cross-sectional survey. Am J Infect Control 2019;47:133–8. 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yang L, Cowling BJ, Liao Q. Intention to receive influenza vaccination prior to the summer influenza season in adults of Hong Kong, 2015. Vaccine 2015;33:6525–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cameron MA, Bigos D, Festa C, Topol H, Rhee KE. Missed Opportunity: Why Parents Refuse Influenza Vaccination for Their Hospitalized Children. Hosp Pediatr 2016;6:507–12. 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Barrett SC, Schmaltz S, Kupka N, Rasinski KA. Impact of Race on Immunization Status in Long-Term Care Facilities. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities 2019;6:153–9. 10.1007/s40615-018-0510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Quinn SC, Jamison A, Freimuth VS, An J, Hancock GR, Musa D. Exploring racial influences on flu vaccine attitudes and behavior: Results of a national survey of White and African American adults. Vaccine 2017;35:1167–74. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Groom HC, Zhang F, Fisher AK, Wortley PM. Differences in Adult Influenza Vaccine-Seeking Behavior. J Public Heal Manag Pract 2014;20:246–50. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e318298bd88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Frew PM, Zhang S, Saint-Victor DS, Schade AC, Benedict S, Banan M, et al. Influenza vaccination acceptance among diverse pregnant women and its impact on infant immunization. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2013;9:2591–602. 10.4161/hv.26993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Flu Vaccine Safety Information | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/prevent/general.htm (accessed May 8, 2020).

- [36].Demeulemeester M, Lavis N, Balthazar Y, Lechien P, Heijmans S. Rapid safety assessment of a seasonal intradermal trivalent influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2017;13:889–94. 10.1080/21645515.2016.1253644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Spila Alegiani S, Alfonsi V, Appelgren EC, Ferrara L, Gallo T, Alicino C, et al. Active surveillance for safety monitoring of seasonal influenza vaccines in Italy, 2015/2016 season. BMC Public Health 2018;18. 10.1186/s12889-018-6260-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Han SB, Rhim JW, Shin HJ, Lee SY, Kim HH, Kim JH, et al. Immunogenicity and safety assessment of a trivalent, inactivated split influenza vaccine in Korean children: Double-blind, randomized, active-controlled multicenter phase III clinical trial. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2015;11:1094–102. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1017693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].van Balveren-Slingerland L, Kant A, Härmark L. Web-based intensive monitoring of adverse events following influenza vaccination in general practice. Vaccine 2015;33:2283–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pillsbury AJ, Glover C, Jacoby P, Quinn HE, Fathima P, Cashman P, et al. Active surveillance of 2017 seasonal influenza vaccine safety: An observational cohort study of individuals aged 6 months and older in Australia. BMJ Open 2018;8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].McEvoy SP. A retrospective survey of the safety of trivalent influenza vaccine among adults working in healthcare settings in south metropolitan Perth, Western Australia, in 2010. Vaccine 2012;30:2801–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gorse GJ, Falsey AR, Ozol-Godfrey A, Landolfi V, Tsang PH. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent intradermal influenza vaccine in adults. Vaccine 2015;33:1151–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van der Maas NAT, Godefrooij S, Vermeer-de Bondt PE, de Melker HE, Kemmeren J. Tolerability of 2 doses of pandemic influenza vaccine (Focetria®) and of a prior dose of seasonal 2009–2010 influenza vaccination in the Netherlands. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2016;12:1027–32. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1120394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Getahun D, Fassett MJ, Peltier MR, Takhar HS, Shaw SF, Im TM, et al. Association between seasonal influenza vaccination with pre- and postnatal outcomes. Vaccine 2019;37:1785–91. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].VaxView | Vaccination Coverage | NIS | Home | CDC n.d. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vaxview/index.html (accessed August 12, 2020).

- [46].Luz PM, Johnson RE, Brown HE. Workplace availability, risk group and perceived barriers predictive of 2016–17 influenza vaccine uptake in the United States: A cross-sectional study. Vaccine 2017;35:5890–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Roy M, Sherrard L, Dubé È, Gilbert NL. Determinants of non-vaccination against seasonal influenza. Heal Reports 2018;29:12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bödeker B, Remschmidt C, Schmich P, Wichmann O. Why are older adults and individuals with underlying chronic diseases in Germany not vaccinated against flu? A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2015;15:618. 10.1186/s12889-015-1970-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Giese C, Mereckiene J, Danis K, O’Donnell J, O’Flanagan D, Cotter S. Low vaccination coverage for seasonal influenza and pneumococcal disease among adults at-risk and health care workers in Ireland, 2013: The key role of GPs in recommending vaccination. Vaccine 2016;34:3657–62. 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2016.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Jiménez-García R, Esteban-Vasallo MD, Rodríguez-Rieiro C, Hernandez-Barrera V, Domínguez-Berjón MAF, Garrido PC, et al. Coverage and predictors of vaccination against 2012/13 seasonal influenza in Madrid, Spain Analysis of population-based computerized immunization registries and clinical records. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2014;10:449–55. 10.4161/hv.27152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ho TY, Huang KY, Huang TT, Huang YS, Ho HC, Chou P, et al. The Impact of Influenza Vaccinations on the Adverse Effects and Hospitalization Rate in the Elderly: A National Based Study in an Asian Country. PLoS One 2012;7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Iwasa T, Wada K. Reasons for and against receiving influenza vaccination in a working age population in Japan: A national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:647. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wooten KG, Wortley PM, Singleton JA, Euler GL. Perceptions matter: Beliefs about influenza vaccine and vaccination behavior among elderly white, black and Hispanic Americans. Vaccine 2012. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].CDC - BRFSS. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html Accessed August 28, 2020.

- [55].Arabyat RM, Raisch DW, Bakhireva L. Influenza vaccination for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Implications for pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm 2018;14:162–9. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lu D, Qiao Y, Brown NE, Wang J. Racial and ethnic disparities in influenza vaccination among adults with chronic medical conditions vary by age in the United States. PLoS One 2017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ahluwalia IB, Ding H, Harrison L, D’Angelo D, Singleton JA, Bridges C. Disparities in influenza vaccination coverage among women with live-born infants: PRAMS Surveillance during the 2009–2010 influenza season. Public Health Rep 2014. 10.1177/003335491412900504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Henninger ML, Irving SA, Thompson M, Avalos LA, Ball SW, Shifflett P, et al. Factors associated with seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:394–402. 10.1089/jwh.2014.5105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ding H, Black CL, Ball S, Donahue S, Fink RV., Williams WW, et al. Influenza Vaccination Coverage Among Pregnant Women — United States, 2014–15 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:1000–5. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6436a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Freimuth VS, Jamison A, Hancock G, Musa D, Hilyard K, Quinn SC. The Role of Risk Perception in Flu Vaccine Behavior among African-American and White Adults in the United States. Risk Anal 2017;37:2150–63. 10.1111/risa.12790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Estimates of Influenza Vaccination Coverage among Adults—United States, 2017–18 Flu Season | FluVaxView | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1718estimates.htm Accessed October 6, 2020.

- [62].Redelings MD, Piron J, Smith LV., Chan A, Heinzerling J, Sanchez KM, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about seasonal influenza and H1N1 vaccinations in a low-income, public health clinic population. Vaccine 2012;30:454–8. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Crouse Quinn S, Jamison AM, Freimuth VS, An J, Hancock GR. Determinants of influenza vaccination among high-risk Black and White adults. Vaccine 2017;35:7154–9. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Jamison AM, Quinn SC, Freimuth VS. “You don’t trust a government vaccine”: Narratives of institutional trust and influenza vaccination among African American and white adults. Soc Sci Med 2019;221:87–94. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Frew PM, Saint-Victor DS, Owens LE, Omer SB. Socioecological and message framing factors influencing maternal influenza immunization among minority women. Vaccine 2014;32:1736–44. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Mesch GS, Schwirian KP. Social and political determinants of vaccine hesitancy: Lessons learned from the H1N1 pandemic of 2009–2010. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:1161–5. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Flanagan KL, Fink AL, Plebanski M, Klein SL. Sex and gender differences in the outcomes of vaccination over the life course. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2017;33:577–99. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]