Abstract

Here is a case of a Pulmonary AVM in a female presenting with sudden onset of dizziness and vomiting most likely secondary to a paradoxical emboli causing an ischemic stroke of the cerebellum.

Keywords: Cerebellar infarction, Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, Cerebellar ischemic infarct, PAVM, Complex pulmonary AVM complication

Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations are vascular abnormalities in which the high resistant intervening capillaries fail to develop between the high pressure arterial system and venous system within a vascular pedicle. While a majority are congenital structural anomalies, under the right circumstances, they can be acquired although very rare. Normally, this vascular interface will redistribute blow flow through multiple high resistant vessels to govern and slow the arterial flow as it drains into the low pressure venous circulation. In the case of pulmonary AVMs, 1 or more segmental branches of the pulmonary artery (s) will form a direct fistulous connection to the low resistant venules, circumventing the normal capillary bed. This aberrant connection forms a communicating defect or right to left shunt to the venous tributaries, where emboli can bypass the capillary filtering similar to a congenital atrial septal defect in the heart. Complications can range from AVM rupture with life-threatening hemorrhage/exsanguination into the hemithorax to systemic thromboembolic events. Here we present findings of a Pulmonary AVM in a 63-year-old female complaining of sudden onset dizziness and vomiting most likely secondary to a paradoxical emboli causing an ischemic stroke of the cerebellum. She has no significant past medical history of DVTS, cardiac arrhythmias, or peripheral vascular disease.

Case presentation

A 63-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension and type II diabetes mellitus presented to the emergency department after a mechanical fall shortly after her onset of symptoms where she was complaining of dizziness and loss of balance. She had no loss of consciousness or head trauma. She reported intermittent dizziness over the next 24 hours that worsened with ambulation, sudden head movements, and certain positioning. Other symptoms included nausea, vertigo, non-bilious, non-bloody vomiting, and weakness in the right upper extremity. She denied fever, chills, abdominal pain, or similar episodes. She had no history of congenital disorders, previous surgeries, or a family history of stroke.

On presentation, the patient was afebrile with a pulse of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 161/79 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. On examination, she was alert and oriented with fluent speech. Cranial Nerves II-XII are intact. Right upper extremity pronator drift, right-sided dysmetria, and gait instability were noted. NIH stroke scale was 5. (0 = No stroke symptoms; 1-4 = Minor stroke; 5-15 = Moderate stroke; 16-20 = Moderate to severe stroke; 21-42 = Severe stroke).

EKG showed a normal sinus rhythm, left ventricular hypertrophy, and possible left atrial enlargement. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed LVEF: 75% with normal systolic function. Mild tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonic regurgitation were noted. There were no structural abnormalities.

Discussion

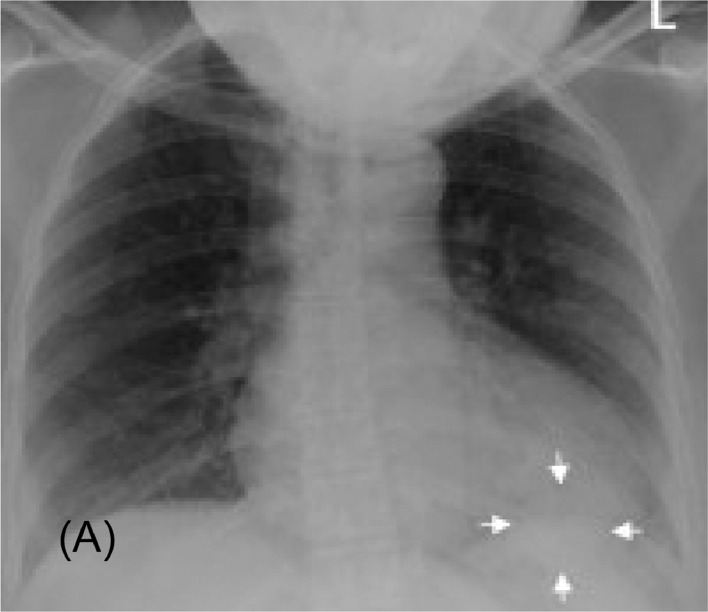

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM) is an anomaly that can be hereditary or acquired. It is characterized by a nodule with at least 2 feeding arteries and a draining vein, often found in the lower lobes. There is a higher predominance in women, with symptom onset occurring usually in the fourth or sixth decade of life. The AP chest radiograph in Figure 1 of our patient shows a well demarcated, round nodular density or mass within the retrocardiac space which is often mistaken for other differential diagnoses such as a neoplastic lung mass. Corresponding Computed Tomography (CT) findings show a double fed arteriovenous malformation adjacent to the posterior cardiac border, superior to the left hemidiaphragm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Image (A). A portable chest radiograph shows a lobulated, homogenous left lower lung zone mass (arrows).

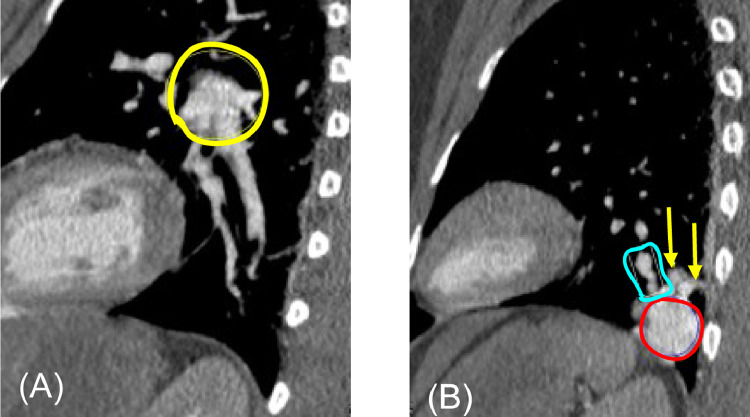

Fig. 2.

Axial contrast-enhanced chest CT. Image (A) shows 2 descending pulmonary arteries (yellow arrows) with a maximum diameter of 5 mm, arising from the left pulmonary artery (not shown). The more caudal axial image, image (B), shows 1 ascending vein (white arrow) that drains into the left pulmonary vein (not shown). Running parallel to the ascending vein are the 2 descending arteries (yellow arrows) that are larger than adjacent and contralateral normal sized pulmonary arteries. Slightly more caudal axial CT images (C and D) demonstrate a nidus of descending arteries (yellow circle in C), which feeds an enhancing oval mass in the left lower lobe (red circle in D) (color version of figure is available online).

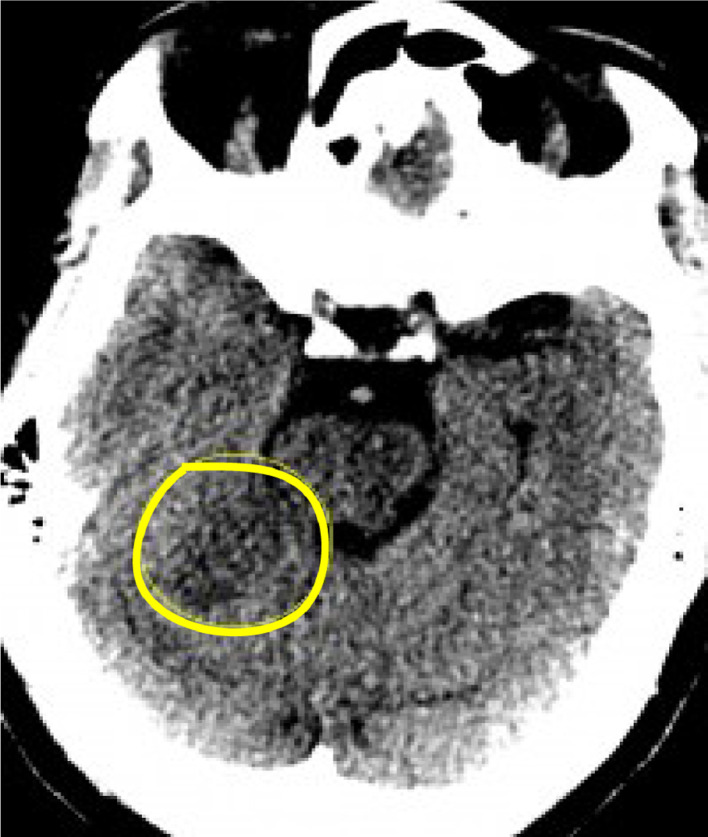

In Figure 5, the non-enhancing CT shows an area of low attenuation in the right, anteromedial cerebellar hemisphere. This infratentorial hypodense lesion likely represents a subacute infarction within the superior cerebellar vascular territory. Diffusion weighted imaging demonstrates increased signal intensity in the cerebellar parenchyma, which was confirmed as fluid restriction with ADC mapping. Findings consistent with ischemic insult/infarction. The patient was outside the window for the use of thrombolytic agents or vascular intervention for clot retrieval because of limited accessibility. Percutaneous management with thrombolytics also had significant risk of hemorrhagic conversion and not having clinical benefit to mitigating the extent of injury or reversing tissue damage (>4 hours since the onset of symptoms). She was started on therapeutic anticoagulation and began intensive inpatient rehab to reduce functional deficits.

Fig. 5.

Axial MRI Diffusion-Weighted-Image (DWI) through the brain shows high signal (yellow circle in image (A) within the right superior cerebellum which was confirmed by ADC mapping (green circle in B) compatible with restricted diffusion secondary to an infarct (color version of figure is available online).

PAVM is a rare entity that occurs when there is an abnormal connection between the low-pressure venous system and high-pressure arterial system without an intervening capillary network. PAVM can be either acquired or congenital, simple or complex. The congenital form is thought to occur because of a defect in capillary formation leading to an intrapulmonary right-to-left shunt. Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome or Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) is highly associated with congenital PAVMs, and up to 40%-60% of patients with a PAVM have this condition. HHT is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by angiodysplastic abnormalities such as mucocutaneous telangiectasia and arteriovenous malformations (AVM) that are commonly found in the brain, lung, and liver. HHT should be suspected in patients with recurrent epistaxis at a young age, particularly if accompanied by brain and lung AVM findings.

The acquired form of PAVMs can occur in patients with a history of previous surgery, congenital heart conditions, chronic liver disease, tuberculosis, or actinomycosis. The majority of PAVMs are simple (80-90%), characterized by having 1 feeding artery and 1 draining vein. Whereas complex PAVMs only make up about 10% and contain 2 or more feeding arteries or 2 or more draining veins. Imaging typically shows unilateral vascular malformations with high predilection of forming in the lung bases. Plain chest radiography will show a well-defined, round or oval nodule or mass that is often hyperdense as in Figure 1. However, Computed Tomography Angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis and allows visualization of the feeding artery, nidus, and draining vein [1,2]. Characteristic findings of a complex lesion were demonstrated in Figures 3 and 4. Patients suffering from PAVM are often asymptomatic. When symptomatic, common findings include digital clubbing, cyanosis due to shunting, and hemoptysis, which occurs in about 7% of patients [1]. Other complications include brain abscesses, hypoxemia [3], and paradoxical embolism leading to an acute ischemic stroke [1]. A secondary ischemic vascular injury was seen in our patient that was picked up on non-contrast head CT Figure 4 likely a subacute infarction that was confirmed with diffusion weighted imaging and ADC mapping Figure 5 (A) and (B).

Fig. 3.

Coronal contrast-enhanced CT images through the chest show 2 descending feeding pulmonary arteries Images A and B (yellow arrows) arising from the left interlobar pulmonary artery (yellow circle), and at least 1 draining vein better seen on Image B (purple arrows) associated with an avidly enhancing oval mass in the posterior left lower lobe (red circle) (color version of figure is available online).

Fig. 4.

Sagittal contrast-enhanced CT. Image (A) shows 2 descending feeding arteries arising from the left interlobar pulmonary artery (yellow circle). An additional sagittal imaging (B) shows 2 arteries (yellow arrows) feeding an avidly enhancing mass in the posterior left lower lobe (red circle). Note the draining vein, extending superiorly from the enhancing mass (teal rectangle).

(A) Axial non-enhanced CT image at the level of the midbrain shows a subtle hypoattenuating focus (yellow circle) in the anterior aspect of the cerebellum (color version of figure is available online).

High risk PAVM are defined as having a feeding artery >3 mm in diameter and require treatment to prevent complications. For simple PAVM, the diameter of the feeding artery is typically measured 1-2 mm proximal to the aneurysmal pouch [2]. Although these guidelines were introduced in the early 1990s, recent literature and reports have shown that feeding arteries less than 3 mm should be treated as well as long as they can be safely reached as complications may occur independent of the feeding artery size. Also, symptomatic PAVM irrespective of size should be treated.

Transthoracic contrast echocardiography utilizes injected microbubbles and is often used to screen for PAVM due to its high sensitivity (98.6%) in suggesting the diagnosis. These microbubbles are normally absorbed by the pulmonary capillaries, but in patients with PAVM, microbubbles are seen in the left heart chambers, thus confirming an abnormal connection. Nuclear medicine lung perfusion scintigraphy performed for other reasons may also suggest abnormal shunting by showing radiotracer activity in an extrapulmonary location such as the brain [4].

Pulmonary artery aneurysm is a vascular dilation of all 3 layers of the wall, usually occurring at bifurcations of branch pulmonary arteries with an absence of a draining vein but can often be mistaken for PAVMS. Pseudoaneurysms contain less than 3 layers and are typically found in segmental or subsegmental arteries that can also be mimickers may share similar non-specific/ambiguous morphology on chest radiography with findings that may include a pulmonary nodular opacity or hilar enlargement. CT findings will show pulmonary arterial dilatation. This patient's CT findings of feeding arteries arising from the left interlobar pulmonary artery, a draining vein, and lack of vascular dilation imply another diagnosis.

Treatment of these vascular anomalies typically consists of embolotherapy which utilizes endovascular coils, balloons, or vascular plugs [6]. Follow-up imaging with contrast-enhanced CT of the chest is performed 6 months after the procedure. Chest CT should be done every 3-5 years or more frequently depending on symptoms to look for recanalization or recurrence [2]. Affected patients should be screened for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia [5]. Prognosis depends on several factors, including the time of diagnosis, size of AVM, treatment, and follow-up compliance.

Patient consent

Verbal consent was obtained from the patient prior to discharge but was not able to be reached for follow-up interview for written consent. Patient anonymity was upheld. No personal information was shared in this write up.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Stowell J, Gilman MD, Walker CM. Thoracic imaging: the requisites. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2019. Congenital thoracic malformations; pp. 193–209.https://www-clinicalkey-com.eresources.mssm.edu/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B978032344886400008X?scrollTo=%23hl0000477 Accessed May 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25999989, Accessed May 21,2020.

- 3.Anticoli S, Pezzella FR, Siniscalchi A, Gallelli L, Bravi MC. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation as a cause of embolic stroke: case report and review of the literature. Interv Neurol. 2015;3(1):27–30. doi: 10.1159/000368969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saboo SS, Chamarthy M, Bhalla S, Harold Park, Patrick Sutphin, Fernando Kay. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: diagnosis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2018;8(3):325–337. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2018.06.01. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6039795/, Accessed 25 May 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moradi F, Morris TA, Hoh CK. Perfusion scintigraphy in diagnosis and management of thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Radiographics. 2019;39(1):169–185. doi: 10.1148/rg.2019180074. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30620694, Accessed 5 March 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saboo S.S., Chamarthy M., Bhalla S., Park H., Sutphin P., Kay F. PAVM embolization: an update. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(4):837–845. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5230. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20858807, Accessed 21 May 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]