Abstract

Alhagi sparsifolia Shap. (Kokyantak) is a ethnic medicine used in the Uyghur traditional medicine system for the treatment of colds, rheumatic pains, diarrhea, stomach pains, headaches, and toothaches, in addition to being an important local source of nectar and high-quality forage grass, and playing a crucial role in improving the ecological environment. Currently, approximately 178 chemical constituents have been identified from A. sparsifolia, including flavonoids, alkaloids, phenolic acids, and 19 polysaccharides. Pharmacological studies have already confirmed that A. sparsifolia has antioxidant, anti-tumor, anti-neuroinflammatory effects, hepatoprotective effects, renoprotective effects and immune regulation. Toxicological tests and quality control studies reveal the safety and nontoxicity of A. sparsifolia. Therefore, this paper systematically summarizes the traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control and toxicology of A. sparsifolia, in order to provide a beneficial reference of its further research.

Keywords: alhagi sparsifolia shap, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control, toxicology

Introduction

The Uyghur system of medicine shares its source with ancient Greek-Arab medicine, one of the three traditional medicines in the world and dating back to more than 2,500 years in Xinjiang, China. The Uyghur system has been widely used in a clinical setting and is based on unique clinical theories. It continues to play an important and non-negligible role in preventing and curing diseases and maintaining public health. Uyghur medicine originated in the Western Regions during the ancient Neolithic period in Hotan (known as Yutian in ancient times) (Maituoheti et al., 2017). Ancient Uyghur physicians believed in Shamanism. They engaged in divination and demon removal and also used prayer and medicine to cure diseases, which formed the prototype of Uyghur medicine. Around the 5th century BC, the ancient ancestors of Uyghurs had advanced surgical techniques and methods of bone grafting (State Administration of Traditional Chinese Herbal Editorial Board, 2005). With the opening of the Silk Road and the deepening of cultural exchanges between China and the West, the Uyghurs absorbed the essence of traditional Chinese, Arabic, Persian, and Indian medicine to establish the Uyghur system of medicine, which had unique characteristics (Wang, 1994; Liu et al., 2016; Zhang, 2018). The humoral theory is the core of the theory of Uyghur medicine, which is gradually formed on the basis of the four major material theories and temperament theory (Kalbinur and Zhang, 2021). Uyghur medical humoral theory believes that hilits (humors) are produced on the basis of four major substances, namely, fire, air, water, and soil, and the four mijazs (temperamental qualities) namely, dry, hot, wet, and cold (Guan and Zhu, 1995; Aili, 1998a; Aili, 1998b). Different humors have different mijazs (Hamulati, 2003; Liu J. B. et al., 2014). The four mijazs, Sapra (bilious humor), kan (blood humor), belhem (mucus humor), sawda (black bile humor) coordinate with each other, maintaining a state of relative dynamic equilibrium to achieve normal physiological function and good health. Uyghur drugs are the “life code” for Uyghurs for longevity (Wang and Jiahan, 2011). Based on the natural temperament of people, Uyghur medicine classifies medicines from plant, animal, and mineral origins into eight medicinal properties, namely, wet, hot, dry, cold, wet-hot, wet-cold, dry-hot, and dry-cold; and nine medicinal tastes, namely, pungent, sweet, bitter, light, hot, sour, salty, astringent, strong, and oily. A combination pattern of medicinal properties-medicinal flavors-organ properties was established and the laws of dispensing Uyghur medicine prescriptions were elaborated (He, 2016). Uyghur medicine is trusted and affirmed by patients because it utilizes unique botanical drugs and formulas and is associated with a rapid onset of action and efficacy.

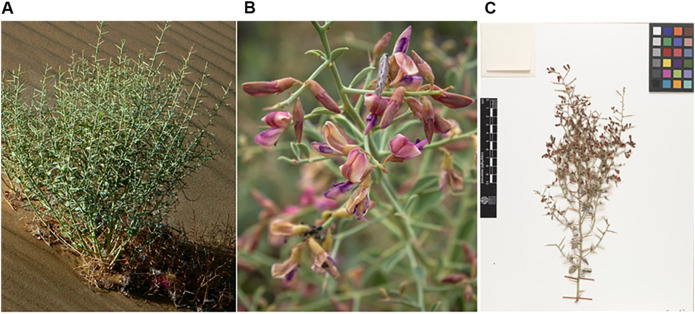

A. sparsifolia (syn. A. kirghizorum var. sparsifolia Shap. and A. maurorum subsp. sparsifolium (Shap.) Yakovlev) (Figure 1), belonging to the Fabaceae family is one such plant that is widely used in China (Inaturalist, 2021; Plant Photo Bank of China, 2021; Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 2021; The Plant List, 2021). It is a typical species in arid and semi-arid desert regions and an important source of nectar and high-quality forage grass in the Tarim and Turpan basins (Sun, 1989; Ma, 1993). A. sparsifolia is mainly used in traditional Uyghur medicine to alleviate physical fatigue and treat colds, rheumatic pains, diarrhea, stomach pain, headaches, and toothaches and is called Kokyantak in the Uyghur language (Li et al., 1996). It is currently included in the Standard of Uyghur Medicinal Materials in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region (Xinjiang Medical Products Administration, 2010). The sugary secretion from its stem and leaves constitutes an important ethnomedicine called Tarangabin, which is effective in the treatment of abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dysentery. It has been included in the “Pharmaceutical Standards of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China” (Uyghur Medicines) (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 1998).

FIGURE 1.

The figure shows the habitat (A), flowers (B) and plant specimen (C) of A. sparsifolia ((A): http://ppbc.iplant.cn/tu/5783326, (B): https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/43301374, (C): http://data.rbge.org.uk/herb/E00364493).

To date, 178 chemical constituents, including flavonoids, alkaloids, and phenolic acids, and 19 polysaccharide fragments have been identified from A. sparsifolia. Modern pharmacological studies reveal that the isolated components and crude extracts exhibit varied pharmacological activities including antioxidant, antitumor, anti-neuroinflammatory, hepatoprotective, and renoprotective effects. However, sufficient links between these pharmacological activities and the traditional uses of A. sparsifolia have not yet been established. Moreover, the bioactivities of only a few monomers have been studied. Besides, although its long-term efficacy has been demonstrated in its use as ethnic medicine, comprehensive reviews with respect to its safety and quality control are lacking. Therefore, in this review, we have summarized and analyzed, for the first time, existing studies (from 1985 to 2021) on the botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control, and toxicology of A. sparsifolia. Our review indicates that the research prospect for A. sparsifolia is very broad and worthy of further investigation.

Material and Methods

The available information on A. sparsifolia was collected from scientific databases and cover from 1985 up to 2021. Information on A. sparsifolia was obtained from published materials, including monographs on medicinal plants, ancient and modern recorded classics, pharmacopoeias, Standard of Uyghur Medicinal Materials in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous region of China and electronic databases, such as Web of Science, Science Direct, Springer, Scifinder, X-MOL, PubMed, CNKI, Wanfang DATA, Google Scholar, Baidu Scholar, Flora of China (FOR). The search terms used for this review included “Alhagi sparsifolia Shap.“, “A. kirghizorum var. sparsifolia Shap.,” and “A. maurorum subsp. sparsifolium (Shap.) Yakovlev” all of which are accepted names and synonyms, “Saccharum alhagi,” “botanical characterization,” “flavonoid compounds,” “ethnomedicinal uses,” “quality standard,” “pharmacology,” and “toxicology.” Language restrictions were not applied during the search.

Botanical Description, Geographic Distribution, and Taxonomy

Botanical Description

A. sparsifolia is a deciduous shrub unique to the arid desert region of Xinjiang and is one of the “three treasures” of the Gobi Desert in preventing land desertification, resisting wind and sand erosion, and improving saline soil (Liu, 1985; Zhang et al., 2002; Arndt et al., 2004; Thomas et al., 2008; Jiang, 2017). There are seven species of the Alhagi genus worldwide, of which three are distributed in China and one is A. sparsifolia in the Flora of China (Zhang et al., 2008; Jin et al., 2014). In regions of high temperatures and low precipitation, the injured stems and leaves of A. sparsifolia secrete Tarangabin (Li et al., 1996; Wang, 2003; Mikeremu et al., 2016).

A. sparsifolia is a semi-shrub approximately 25–40 cm tall with an upright, glabrous stem having thin stripes. The leaves are alternate and ovate, obovate, or rounded ovoid, measuring approximately 8–15 mm long and 5–10 mm wide. The apex is round with short, hard tips, and the base is cuneate, entire, and glabrous with a short petiole. The flower is racemose, axillary, and 8–10 mm long. The rachis transforms into hard, sharp thorns that are 2–3 times as long as the leaves. The thorns of annual branches have 3–6 (or 3–8) flowers, but the older ones do not. The bract is subulate and up to 1 mm long, whereas the pedicel is 1–3-mm long. The calyx is campanulate, 4–5-mm long, and pubescent. The calyx teeth are triangular or subulate-triangular and one-third to one-fourth the length of the calyx tube. The corolla is reddish purple with a standard oblong-ovate shape and is 8–9-mm long, with an obtuse or truncated apex. The base is cuneate with a short petiole, the wing is oblong and three-quarters the length of the standard, and the carina is about the same length as the standard. The ovary and legume are linear and almost glabrous (Flora of China Editorial Committee, 1998). The harvest time of the various medicinal parts of A. sparsifolia differ. Flowers and leaves are collected in early summer (april to early May), Tarangabin is collected during midsummer (June to August), the seeds are collected in autumn (July to September), and the whole grass or aboveground parts are picked during the growing period of the year (Wang, 2003).

Geographic Distribution

A. sparsifolia is distributed in Central and East Asia, mainly in China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan (GBIF, 2021; Nishanbaev et al., 2016) (Figure 2). The official website, Flora of China, states that A. sparsifolia plants are mainly found in Inner Mongolia, Gansu and Qinghai provinces, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China (Flora of China Editorial Committee, 1998). The latest MaxEnt model simulations predict that the suitable habitats of A. sparsifolia will decrease due to the climate change scenarios of RCP 2.6 and 8.5 on the whole, indicating that the abundance of this species will show a downward trend in the future (Yang et al., 2017).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of A. sparsifolia in different countries and regions (https://www.gbif.org/species/2945088).

Taxonomy

A. sparsifolia belongs to the Fabaceae family, which consists of over 24,505 species belonging to 946 genera, including Glycine, Glycyrrhiza, Desmanthus, Lupinus, Medicago, Ormosia, and Styphnolobium. Among them, the genus Alhagi includes eight species, namely, A. graecorum Boiss., A. canescens (Regel) B. Keller & Shap., A. kirghisorum Schrenk, A. maurorum Medik., A. nepalensis (D.Don) Shap., A. pseudalhagi (M. Bieb.) Desv. ex B. Keller & Shap., A. sparsifolia Shap., A. sparsifolium (Shap.) Shap. (http://www.worldfloraonline.org/taxon/wfo-0000198672/).

Traditional Uses

A. sparsifolia was first found to be reported in “Bei shi” (AD 659) as Yang ci, whereas its medicinal value was first recorded in Tang Dynasty’s medical book, “Ben Cao Shi Yi” (AD 741) as Cao mi. In Ming Dynasty’s medical book, Compendium of Materia Medica (AD 1590), A. sparsifolia is listed as a “top grade” drug. It is a sweet, sour, and nontoxic drug usually used to treat abdominal pain, diarrhea, and dysentery. A. sparsifolia can be considered as “multiple medicinal parts in one plant,” i.e., different medicinal parts of the same plant have different pharmacological effects owing to differences in the chemical constituents and accumulation of the main components. Apart from being used routinely to treat colds and pains in various parts of the body, its leaves alleviate swelling and pain in joints; its flowers clear heat and detoxify the body; the whole plant alleviates colds and fevers, damp fever, and enteritis; and its seeds alleviate febrile dysentery and toothache (Yuan et al., 2012). Additionally, the therapeutic effects of Tarangabin depend on the route of administration. It is administered orally to treat hemorrhoids, as nasal drops to treat intractable headaches, and as eye drops to treat keratitis (Quan and Xu, 2009). As a traditional Uyghur medicine, A. sparsifolia is widely used in Uyghur medical practice in compound prescriptions with other botanical drugs. The prescription name, main composition, formulation, traditional and clinical uses, and prescription sources of A. sparsifolia are described in Table 1 (Chinese Medical Encyclopedia Committee, 2005).

TABLE 1.

The traditional use of A. sparsifolia compound prescription in China.

| Prescription name | Main composition | Extracts, formulations, usage, dosage | Traditional and clinical uses | Prescription sources |

| Maitibuhe Heiyari Xianbaier Tang | Tarangabin (45 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (45 g)/Cassia fistula L., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (25 pcs)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (25 pcs)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Semen Althaeae Roseae (10 g)/Alcea rosea L., Herba Violae Tianshanicae (10 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Herba Chamomillae (6 g)/Chamaemelum nobile (L.) All | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/100–200 ml each time | Treatment of conjunctival ophthalmia, ocular rim infection, eye pain, constipation | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

| Maitibuhe Aifeitimeng Tang | Tarangabin (120 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Cortex Terminaliae Citrinae (45 g)/Terminalia citrina (Gaertn.) Roxb., Cortex Terminaliae Billericae (45 g)/Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb., Herba Dracocephali Moldavicae (45 g)/Dracocephalum moldavica L., Fructus Terminaliae chebulae (15 g)/Terminalia chebula Retz., Fructus Phyllanthi (15 g)/Phyllanthus emblica L., Flos Lavandulae (15 g)/Lavandula angustifolia Mill., Radix Valerianae (15 g)/Valeriana officinalis L., Herba Anchusae (30 g)/Anchusa azurea Mill., Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (30 g))/Cassia fistula L., Semen Cuscutae (90 g)/Cuscuta chinensis Lam., Fos Nelumbinis (12 g)/Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Semen Amygdalae (120 g)/Prunus amygdalus Batsch, Fructus Mume (120 g)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Fructus Caryophylli (6 g)/Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L.M.Perry, Cortex Cinnamomi (6 g)/Cinnamomum tamala (Buch.-Ham.) T.Nees & Eberm., Herba Fumariae (3 g)/Fumaria officinalis L., Rhizoma Polypodiodis (12 g)/Polypodiode snipponica (Mett.) Ching, Nipponicae (12 g)/Dioscorea nipponica Makino, Usnea (9 g)/Usnea diffracta Vain., Semen Alpiniae Katsumadai (9 g)/Alpinia katsumadai Hayata | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/124 ml each time | Treatment of insomnia, pain and retentionofurine | Hui Yao Fang (AD 1619) |

| Maizhuni Binaifeixie Migao | Tarangabin (150 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Folium Sennae (150 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Turpeth (16 g)/Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso, Herba Anchusae (16 g)/Anchusa azurea Mill., Flos Rosae Rugosae (16 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (3 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Fos Nelumbinis (3 g)/Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Fructus Vitis Viniferae (3 g)/Vitis vinifera L | Refined Honey/Honey Paste/oral administratio/qd/10 g each time | Treatment of febrile headache, eye pain, ear pain, conjunctival congestion, dizziness and constipation | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

| Maitibuhe Ainaluo Tang | Tarangabin (50 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Mume (100 g)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Semen Cichorii (10 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (10 g)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Flos Rosae Rugosae (13 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (16 g)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (16 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Folium Sennae (20 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (31 g)/Tamarindus indica L., Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (50 g))/Cassia fistula L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/30–50 g each time | Treatment of headache, migraine, hematogenous dizziness, heartburn and thirst, typhoid fever, hepatomegaly | Bai Se Gong Dian (AD 1200) |

| Nukuyi Ailile Jinpaoye I | Tarangabin (50 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (10 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Semen Cichorii (10 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Cortex Terminaliae citrinae (31 g)/Terminalia citrina (Gaertn.) Roxb | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid-tid/30–60 ml each time | Treatment of febrile headache | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

| Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (31 g))/Cassia fistula L., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (31 g)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (56 g)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (60 g)/Tamarindus indica L., Fructus Mume (100 g)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc | ||||

| Nukuyi Ailile Jinpaoye Ⅱ | Tarangabin (150 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Cortex Terminaliae citrinae (30 g)/Terminalia citrina (Gaertn.) Roxb., Fructus Mume (30 pcs)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (30 pcs)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (30 pcs)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (60 pcs)/Tamarindus indica L., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (9 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Semen Cichorii(9 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (30 g))/Cassia fistula L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/100 ml each time | Treatment of febrile headache, migraine, fever and thirst | A Ri Fu Yan Fang (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Nukuyi Pawake Jinpaoye | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Mume (30 pcs)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (30 pcs)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (30 pcs)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (30 g)/Tamarindus indica L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/50–100 ml each time | Treatment of fever, meningitis, migraine | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

| Mengziji Saiweida Chengshuji | Tarangabin (70 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Herba Anchusae (25 g)/Anchusa azurea Mill., Rhizoma Polypodiodis (25 g)/Polypodiode snipponica (Mett.) Ching, Nipponicae (25 g)/Dioscorea nipponica Makino, Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (25 g)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Flos Lavandulae (25 g)/Lavandula angustifolia Mill., Cortex Terminaliae chebulae (16 g)/Terminalia chebula Retz., Herba Hyssopi (16 g)/Hyssopus officinalis L., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (16 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim | Aqueous/Decoction oral administratio/bid-tid/50 ml each time | Treatment of meningitis | Bai Di Yi Yao Shu (AD 1368) |

| Maizhuni Binaifeixie Migao I | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (30 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Semen Amygdalae (30 g)/Prunus amygdalus Batsch, Mastix (15 g)/Pistacia lentiscus L., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (15 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Turpeth (60 g)/Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso, Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (60 g))/Cassia fistula L | Aqueous & Sugar/Honey Paste/oral administratio/bid/5 g each time (adults); bid/3 g each time (children) | Treatment of cough, intestinal obstruction, phlegm, gastritis | A Ri Fu Yan Fang (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Aibi Taipi Xiaowan | Tarangabin (3 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Papaveris Pericarpium (3 g)/Papaver somniferum L., Rmmi Rabicum (3 g)/Senegalia senegal (L.) Britton, Gummi Tragacanthae (3 g)/Astragalus gummifer Labill., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (3 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Semen Lagenariae Sicerariae (3 g)/Lagenaria siceraria (Molina) Standl., Semen Amygdalae (3 g)/Prunus amygdalus Batsch, Semen Cucumeris (3 g)/Cucumis satiuus L | Pill/oral administratio/bid/1 pcs each time | Treatment of habitual typhoid fever, tuberculosis, back pain, cough and phlegm | Bai Di Yi Yao Shu (AD 1368) |

| Pill | ||||

| Xieribiti Ounabi Tangjiang | Tarangabin (300 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Mume (60 g)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (30 g)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (100 g)/Tamarindus indica L., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (60 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Turpeth (60 g)/Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso, Resina Scammoniae (3 g)/Convovulus scammonia L., Stigma Croci (1 g)/Crocus sativus L | Aqueous/Syrup/oral administratio/tid/50 ml each time | Treatment of hyperthermic typhoid fever arising from the excessive influence of hot body humor such as bilious or blood | A Ri Fu Yan Fang (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Xieribiti Kushuxi Tangjiang | Tarangabin (100 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Semen Cichorii (15 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Herba Moslae (15 g)/Mosla chinensis Maxim., Semen Cuscutae (20 g)/Cuscuta chinensis Lam., Radix Foeniculi (35 g)/Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (50 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Radix Cichorii (30 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Semen Cuscutae (30 g)/Cuscuta chinensis Lam., Semen Cucumeris (30 g)/Cucumis satiuus L | Aqueous & Sugar/Syrup/oral administratio/tid/100 ml each time | Treatment of respiratory system diseases and heart, liver and gastrointestinal diseases, fever and cough, complicated typhoid fever, febrile heart and liver deficiency, unfavorable urination and poor bowel movement | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

| Maitibuhe Aifeisanting Tang | Tarangabin (30 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Herba Absinthii (15 g)/artemisia absinthium L., Flos Rosae Rugosae (20 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Fructus Tamarindi Indicae (60 g)/Tamarindus indica L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/tid/100 ml each time | Treatment digestive disorders, such as spleen and stomach diseases, hyperthermic typhoid fever, fever and headache, indigestion | Zhu Yi Dian (AD 1040–1,050) |

| Maizhuni Binaifeixie Migao Ⅱ | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (30 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Semen Amygdalae (30 g)/Prunus amygdalus Batsch, Mastix (15 g)/Pistacia lentiscus L., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (15 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Turpeth (60 g)/Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso, Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (60 g)/Cassia fistula L | Aqueous & Sugar/Honey Paste/oral administratio/tid/5 g each time(adults); qd/1 g each time(children) | Treatment of intestinal and respiratory disorders, such as intestinal constipation and obstruction, abnormal bilious and mucinous increase, cough and phlegm | A Ri Fu Yan Fang (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Maitibuhe Mengziji Chengshuji Ⅲ | Tarangabin (30 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (15 g)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Solani Nigri (10 g)/Solanum nigrum L., Semen Rutae (6 g)/Ruta graveolens L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/tid × 3 d | Treatment of increased abnormal body humor in upper extremity joints, upper extremity soreness | Bai Se Gong Dian (AD 1200) |

| Maitibuhe Surenjiang Tang Ⅱ | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Folium Sennae (20 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Flos Rosae Rugosae (12 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Cortex Terminaliae citrinae (12 g)/Terminalia citrina (Gaertn.) Roxb., Bulbus Colchici (6 g)/Colchicum autumnale L., Radix Foeniculi (6 g)/Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Herba Foeniculi (6 g)/Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Fructus Apii (6 g)/Apium graveolens L., Herba Centaurii (6 g)/Centaurium erythraea Rafn, Fructus Anethi (6 g)/Anethum graveolens L., Herba Anchusae (10 g)/Anchusa azurea Mill., Herba Melissae Axillaris (10 g)/Melissa axillaris (Benth.) Bakh.f | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/tid/50–100 ml each time | Treatment of joint pain, urinary discomfort, poor bowel movement, arthritis and swelling | A Ri Fu Yan Fang (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Xieribiti Mengziji Maxire Tangjiang | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Flos Violae Tianshanicae (16 g)/Viola thianschanica Maxim., Flos Nelumbinis (16 g)/Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Flos Rosae Rugosae (16 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Semen Cichorii (9 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Radix Cichorii (18 g)/Cichorium intybus L., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (7 pcs)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill | Aqueous/Syrup/oral administratio/bid/50 ml each time | Treatment of skin diseases such as febrile dermatitis, various inflammations and swellings inside and outside the body, and dry stools | Bao jian Yao Yuan (AD 1556–1,662) |

| Mengziji Bairese Chengshuji Ⅲ | Tarangabin (100 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Anethi (15 g)/Anethum graveolens L., Fructus Apii (15 g)/Apium graveolens L., Semen Nigellae (15 g)/Nigella glandulifera Freyn & Sint., Folium Sennae (15 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Radix Foeniculi (30 g)/Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Rhizoma Zingiberis (30 g)/Zingiber officinale Roscoe, Flos Lavandulae (30 g)/Lavandula angustifolia Mill., Fructus Caricae (25 g)/Ficus carica L., Radix Apii (25 g)/Apium graveolens L., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (25 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Radix et Rhizoma Nardostachyos (10 g)/Nardostachys jatamansi (D.Don) DC., Fructus Vitis Viniferae (150 g)/Vitis vinifera L | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/tid/150 ml each time | Treatment of skin hypopigmentation diseases, such as vitiligo | Bai Di Yi Yao Shu (AD 1368) |

| Musili Bairese Qingchuji | Tarangabin (150 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Cortex Terminaliae citrinae (20 g)/Terminalia citrina (Gaertn.) Roxb., Fructus Terminaliae chebulae (20 g)/Terminalia chebula Retz., Cortex Terminaliae billericae (20 g)/Terminalia bellirica (Gaertn.) Roxb., Fructus Phyllanthi (20 g)/Phyllanthus emblica L., Herba Anchusae (15 g)/Anchusa azurea Mill., Herba Melissae Axillaris (15 g)/Melissa axillaris (Benth.) Bakh.f., Radix Foeniculi (15 g)/Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Fructus Anethi (15 g)/Anethum graveolens L., Radix et Rhizoma Glycyrrhizae (15 g)/Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC., Fructus Solani Nigri (15 g)/Solanum nigrum L., Semen Cuscutae (30 g)/Cuscuta chinensis Lam., Folium Sennae (30 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Radix Plumbinis (30 g)/Plumbago zeylanica L., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (30 g)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Cordiae Dichotomae (10 g)/Cordia dichotoma G.Forst., Turpeth (10 g)/Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso | Aqueous/Decoction/oral administratio/bid/150 ml each time | Treatment of abnormal increased body humor, irregular bowel movements, bloating and edema, vitiligo | Bai Di Yi Yao Shu (AD 1368) |

| Xieribiti Ounabi Murekaibi Tangjiang | Tarangabin (60 g)/Alhagi sparsifolia Shap., Fructus Ziziphi Jujubae (10 pcs)/Ziziphus jujuba Mill., Fructus Vitis Viniferae (10 pcs)/Vitis vinifera L., Fructus Mume(10 pcs)/Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc., Flos Nelumbinis (10 g)/Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn., Semen Althaeae Roseae (10 g)/Alcea rosea L., Fructus Solani Nigri (10 g)/Solanum nigrum L., Folium Isatidis (10 g)/Isatis tinctoria L., Herba Fumariae (15 g)/Fumaria officinalis L., Folium Sennae (15 g)/Senna alexandrina Mill., Semen Cucumeris (15 g)/Cucumis satiuus L., Semen melo (15 g)/Cucumis melo L., Semen Amygdalae (15 g)/Prunus amygdalus Batsch, Lignum Santali Albi (6 g)/Santalum album L., Herba Swertiae (6 g)/Swertia diluta (Turcz.) Benth. & Hook.f., Flos Rosae Rugosae (6 g)/Rosa rugosa Thunb., Fructus Cassiae Fistulae (30 g)/Cassia fistula L | Aqueous/Syrup/oral administratio/bid/60 ml each time | Treatment of gynecological diseases such as cervicitis, uterine sores, vulvar itching, uterine pain | Yi Xue Zhi Mu Di (AD 1737) |

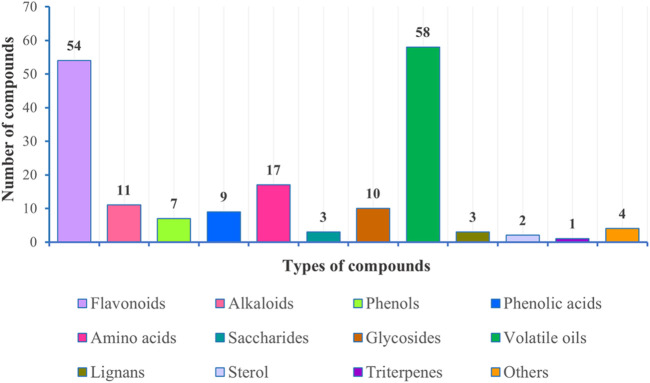

Phytochemistry

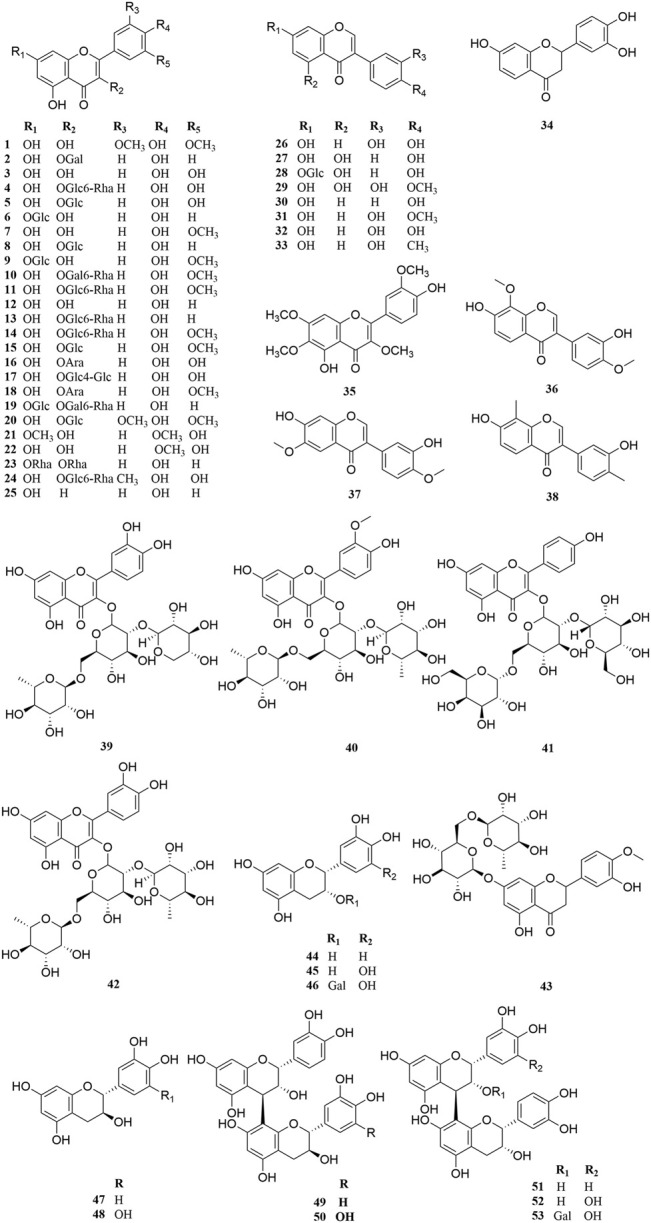

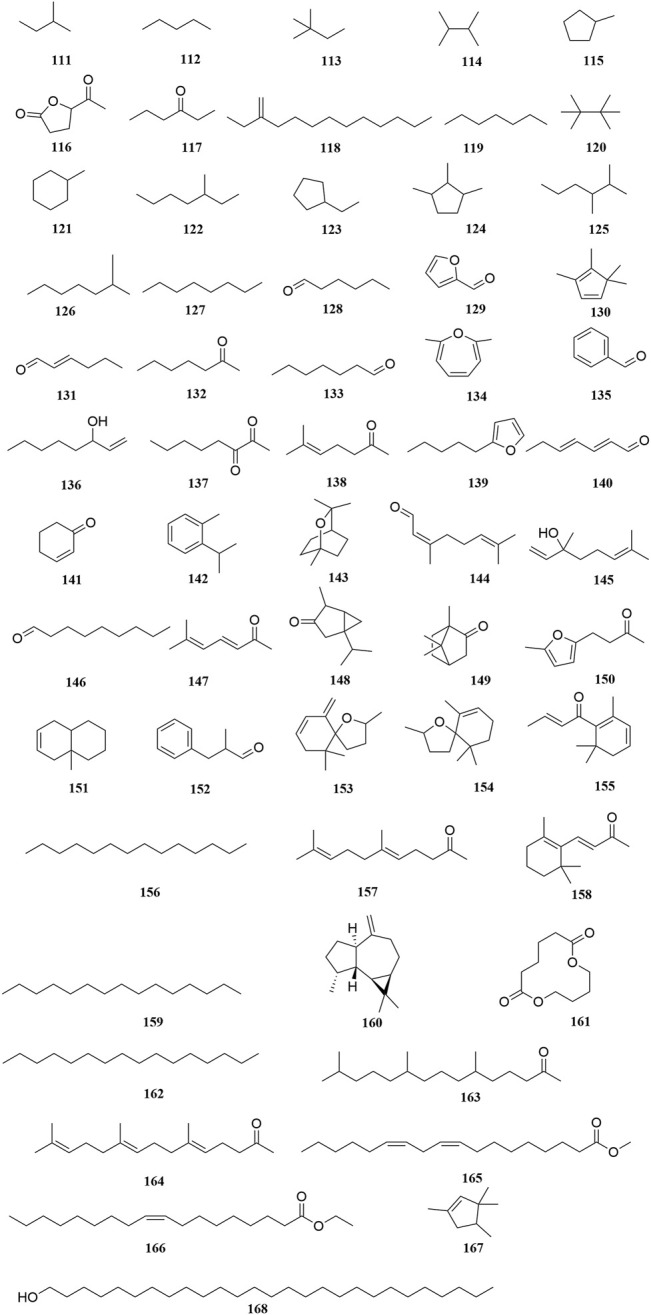

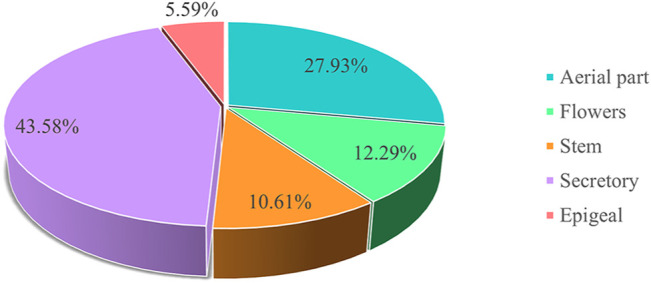

Investigation of chemical constituents from A. sparsifolia began in 1997. To date, approximately 178 chemical constituents have been identified, including flavonoids, alkaloids and phenolic acids, and 19 polysaccharides. Among them, flavonoids and polysaccharides are the predominant and characteristic constituents. The chemical constituents that have been identified are listed in Table 2 and their corresponding structures in Figures 3–8.

TABLE 2.

Chemical components isolated and structurally identified from A. sparsifolia (MF = Molecular Formula).

| No | Chemical constituents | MF | Extracts | Parts | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | |||||

| 1 | butin | C15H12O5 | EtOAc | Aerial part | Ma et al. (2018a) |

| 2 | kaempferol-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C21H20O11 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 3 | isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 4 | isorhamnetin-3-O-β-rutinoside | C28H32O16 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 5 | kaempferol | C15H10O6 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 6 | isoquercitrin | C21H20O12 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 7 | syringetin | C17H14O8 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 8 | kaempferol-3-O-β-d-galactopyranoside | C21H20O11 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 9 | kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C21H20O11 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 10 | isorhamnetin-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C22H22O12 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 11 | isorhamnetin-3-O-robinobioside | C28H32O16 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 12 | quercetin | C15H10O7 | EtOA | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 13 | quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | C27H30O16 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 14 | kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside | C27H30O15 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 15 | quercetin-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C21H20O12 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 16 | isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside | C22H22O12 | BuOH | Aerial part | Su et al. (2008) |

| 17 | guaijaverin | C20H18O11 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 18 | quercetin-3-O-maltoside | C27H30O16 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 19 | isorhamnetin-3-O-arabinoside | C21H20O12 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 20 | kaempferol-3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl(1→6)-β-d-glucopyranosyl-7-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C33H40O19 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 21 | syringetin-3-O-β-D-glucoside | C23H24O13 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 22 | ombuin | C17H14O7 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 23 | tamarixetin | C16H12O7 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 24 | kaempferitrin | C27H30O14 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 25 | 3′-O-methylquercetin-3-O-α-rutinoside | C28H32O16 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 26 | apigenin | C15H10O5 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 27 | 3′,4′,7-trihydroxyisoflavone | C15H10O5 | BuOH | Aerial part | Liu et al. (2019a) |

| 28 | genistein | C15H10O5 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 29 | genistin | C21H20O10 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 30 | pratensein | C16H12O6 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 31 | formonoetin | C16H12O4 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 32 | 3′,7-dihydroxyl-4′-methoxylisoflavone | C16H12O5 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 33 | 3′,4′,7-trihydroxylisoflavone | C15H10O5 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 34 | 3′,7-dihydroxy-4′-methylisoflavone | C16H12O4 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 35 | chrysoplenol B | C19H18O8 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 36 | 3′,7-dihydroxyl-4′,8-dimethoxylisoflavone | C17H14O6 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 37 | 3′,7-dihydroxyl-4′,6-dimethoxylisoflavone | C17H14O6 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 38 | 3′,7-dihydroxy-4′,8-dimethylisoflavone | C17H14O4 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 39 | quercetin-3-O-(2-β-d-xylopyranosyl)-β-d-rutinoside | C32H38O20 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 40 | typhaneoside | C34H42O20 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 41 | kaempferol-3-O-β-d-glucosyl-(1→2)-O-[α-l-rhamnosyl(1→6)]-β-d-galactoside | C33H40O21 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 42 | quercetin-3-O-(2″,6″-di-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl)-β-d-glucopyranoside | C33H40O20 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 43 | hesperidin | C28H34O15 | EtOH | Secretory | Guo et al. (2020) |

| 44 | (-)-epicatechin | C15H14O6 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 45 | (-)-epigallocatechin | C15H14O7 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 46 | (-)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate | C22H18O11 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 47 | (+)-catechin | C15H14O6 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 48 | (+)-gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 49 | (-)-epigauocatechin-3-O-ganate-(4β-8)-(-)-epicateehin | C30H26O12 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 50 | (-)-epicatechin-(4β-8)-(+)-gallocatechin | C30H26O13 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 51 | proanthocyanidin B-2 | C30H26O12 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 52 | proanthoeyanidin B-1 | C30H26O13 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 53 | (-)-epigallocateehin-(4β-8)-(-)-epicatechin | C37H30O17 | EtOH | Epigeal | Malik et al. (1997) |

| 102 | Alkaloids | ||||

| 54 | alhagifoline A | C14H15NO3 | BuOH | Aerial part | Zou et al. (2012) |

| 55 | aurantiamide acetate | C27H28N2O4 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 56 | aurantiamide | C27H28N2O4 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 57 | pyrrolezanthine | C14H15NO3 | BuOH | Aerial part | Zou et al. (2012) |

| 58 | pyrrolezanthine-6-methyl ether | C15H17NO3 | BuOH | Aerial part | Zou et al. (2012) |

| 59 | betaine | C5H11NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 60 | 1-butyl-1H-pyrrole | C8H13N | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng, (2010) |

| 61 | 1-pentyl-1H-pyrrole | C9H15N | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng, (2010) |

| 62 | 1-isoamylpyrrole | C9H15N | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng, (2010) |

| 63 | 5-isocyanato-1-(isocyanatomethyl)-1,3,3-trimethyl-cyclohexane | C12H18N2O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng, (2010) |

| 64 | ethyl ester | C31H29NO3 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng, (2010) |

| 102 | Phenols, carboxylic acids, phenolic acids and amino acids | ||||

| 65 | 3-methoxy-4-vinylphenol | C9H10O2 | EtOAc | Aerial part | Ma et al. (2018b) |

| 66 | 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O3 | BuOH | Aerial part | Ma et al. (2018b) |

| 67 | ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 68 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 69 | p-hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 70 | vanillin | C8H8O3 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 71 | epoxyconiferyl alcohol | C10H10O4 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 72 | isovanillic acid | C8H8O4 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 73 | gentisic acid | C7H6O4 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 74 | gallic acid | C7H6O5 | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 75 | dipropylphthalate | C14H18O4 | EtOAc | Secretory | Cheng et al. (2014) |

| 76 | benzoic acid | C7H6O2 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 77 | methoxyphenyl acetic acid | C9H10O3 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 78 | 4′-hydroxylacetophenone | C8H8O2 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 79 | 3-hydroxyl-4-methoxybenzyl alcohol | C8H10O3 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 80 | 4-hydroylphenoyl | C7H6O3 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 81 | aspartic acid | C4H7NO4 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 82 | l-threonine | C4H9NO3 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 83 | β-hydroxyalanine | C3H7NO3 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 84 | glutamic acid | C5H9NO4 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 85 | glycine | C2H5NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 86 | alanine | C3H7NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 87 | cystine | C6H12N2O3S2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 88 | valine | C5H11NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 89 | dl-methionine | C5H11NO2S | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 90 | l-isoleucine | C6H13NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 91 | leucine | C6H13NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 92 | tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 93 | phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 94 | histidine | C6H9N3O2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 95 | proline | C5H9NO2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 96 | lysine | C6H14N2O2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 97 | arginine | C6H14N4O2 | Et2O | Aerial part | Liu G. C. et al. (2014) |

| 102 | Saccharides and glycosides | ||||

| 98 | (+)-tortoside A | C29H38O12 | EtOAc | Aerial part | Ma et al. (2018b) |

| 99 | (-)-tortoside A | C29H38O12 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 100 | (3S,5R,6R,7E,9S)-megastigman-7-ene-3,5,6,9-tetrol-3-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C19H34O9 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 101 | (3S,5R,6R,7E,9S)-megastigman-7-ene-3,5,6,9-tetrol-9-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C19H34O9 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 102 | (1R)-4-[(3R)-3-hydroxybutyl]-3,5,5-trimethylcyclohex-3-enyl-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C20H36O6 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 103 | (1R)-3-[(4R)-4-hydroxybutyl]-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-methy-propyl-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C19H34O7 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 104 | pinoresinol-4-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C28H36O11 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 105 | syringaresionl-4-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C30H40O13 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 106 | 2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)ethanol-O-β-d-glucopyranoside | C14H20O7 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 107 | 4,6-dihydroxy-2-O-β-d-glucopyranosyl acetophenone | C15H20O9 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 108 | methyl-α-d-fructofuranoside | C7H14O6 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 109 | D-Glu-1α→2β-D-Fru | C12H22O11 | BuOH | Secretory | Cheng et al. (2014) |

| 110 | D-Glu-1β→6-D-Glu-1α→2β-D-Fru | C18H32O16 | BuOH | Secretory | Cheng et al. (2014) |

| 111 | Volatile oils | ||||

| 112 | isopentane | C5H12 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 113 | pentane | C5H12 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 114 | 2,2-dimethylbutane | C6H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 115 | 2,3-dimethylbutane | C6H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 116 | methylcyclopentane | C6H12 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 117 | 5-acetyldihydro-2(3H)-furanone | C6H8O3 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 118 | 3-hexanone | C6H12 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 119 | 2-ethyl-1-dodecene | C14H28 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 120 | heptane | C7H16 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 121 | hexamethylethane | C8H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 122 | methylcyclohexane | C7H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 123 | 3-methylheptane | C8H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 124 | ethylcyclopentane | C7H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 125 | 1,2,3-trimethyl-cyclopentane | C8H16 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 126 | 2,3-dimethylhexane | C8H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 127 | 2-methylheptane | C8H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 128 | octane | C8H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 129 | hexanal | C6H12O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 130 | furfural | C5H4O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 131 | 1,2,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3-cyclopentadiene | C9H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 132 | (E)-2-hexenal | C6H10O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 133 | butylacetone | C7H14O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 134 | heptanal | C7H14O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 135 | 2,7-dimethyloxepine | C8H10O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 136 | benzaldehyde | C7H6O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 137 | 3-hydroxy-1-octene | C8H16O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 138 | 2,3-octanedione | C8H14O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 139 | 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | C8H14O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 140 | 2-pentylfuran | C9H14O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 141 | 2,4-heptadienal | C7H10O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 142 | 2-cyclohexen-1-one | C6H8O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 143 | o-cymene | C10H14 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 144 | eucalyptol | C10H18O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 145 | 3,7-dimethyl-(Z)-2,6-octadienal | C10H16O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 146 | linalool | C10H18O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 147 | nonanal | C9H18O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 148 | 6-methyl-3,5-heptadien-2-one | C8H12O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 149 | thujone | C10H16O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 150 | camphor | C10H16O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 151 | 4-(5-methyl-2-furyl)-2-butanone | C9H12O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 152 | 4a-methyl-1,2,3,4,4a,5,8,8a-octahydronaphthalene | C11H18 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 153 | 2-methyl-3-phenylpropanal | C10H12O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 154 | vitispirane | C13H20O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 155 | theaspirane | C13H22O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 156 | β-damascenone | C13H18O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 157 | tetradecane | C14H30 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 158 | (E)-geranylacetone | C13H22O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 159 | (E)-β-ionone | C13H20O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 160 | pentadecane | C15H32 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 161 | aromadendrene vi | C15H24 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 162 | 1,6-dioxacyclododecane-7,12-dione | C10H16O4 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 163 | hexadecane | C16H34 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 164 | 6,10,14-trimethyl-2-pentadecanone | C18H36O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 165 | farnesylacetone | C18H30O | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 166 | methyl linoleate | C19H34O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 167 | ethyl oleate | C20H38O2 | Aqueous | Secretory | Cheng (2010) |

| 168 | 1,3,3,4-tetramethylcyclopentene | C9H16 | BuOH | Aerial part | Ma et al. (2018b) |

| 169 | heptacosan-1-ol | C27H56O | EtOAc | Flowers | Guo et al. (2016) |

| 170 | Other constituents | ||||

| 171 | pinoresinol | C20H22O6 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 172 | syringaresinol | C22H26O8 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 173 | bombasinol A | C21H24O6 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 174 | blumenol A | C13H20O3 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 175 | abscisic acid | C15H20O4 | EtOH | Aerial part | Zhou et al. (2017) |

| 176 | niacin | C6H5NO2 | BuOH | Stem | Ouyang et al. (2018) |

| 177 | dibutyl phthalate | C16H22O4 | BuOH | Flowers | Muratova et al. (2019) |

| 178 | stigmasterol | C29H48O | PET | Aerial part | Su et al. (2008) |

| 179 | β-sitosterol | C29H50O | PET | Aerial part | Su et al. (2008) |

| 180 | 12-ene-ursulanol | C30H50O | EtOAc | Secretory | Cheng et al. (2014) |

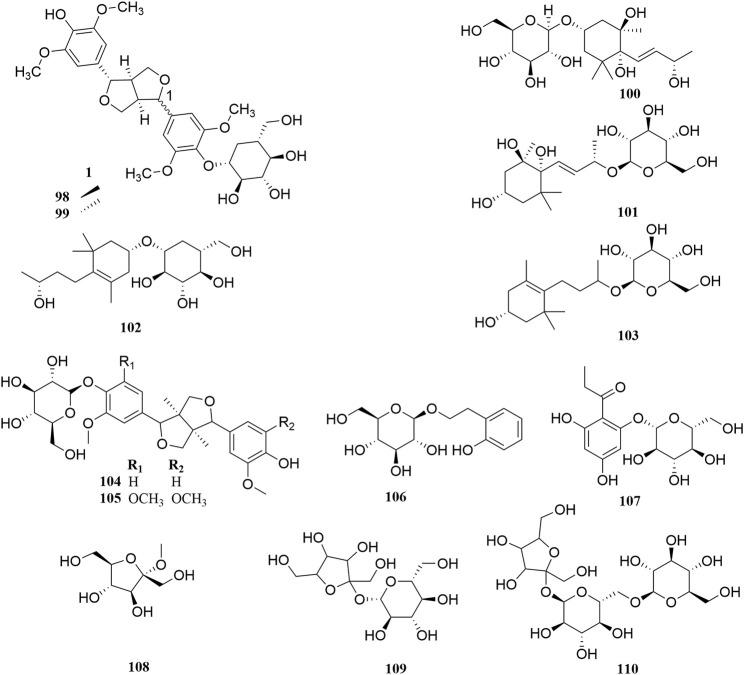

FIGURE 3.

Chemical structures of flavonoids (1–53).

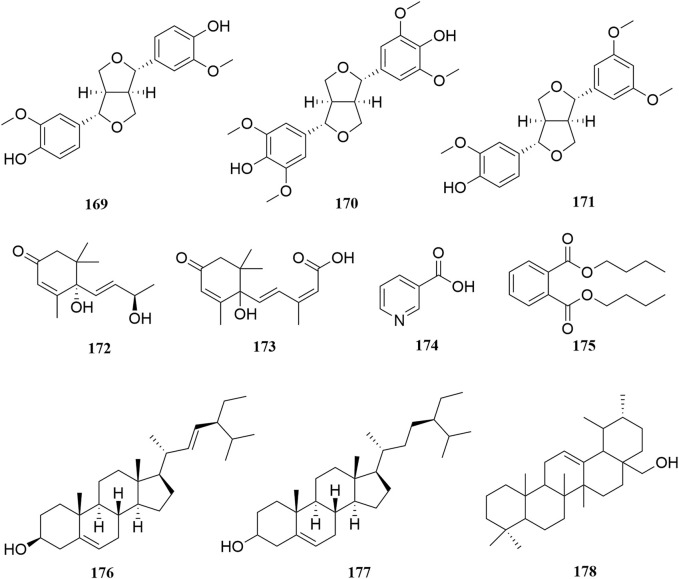

FIGURE 8.

Chemical structures of other constituents (169–178).

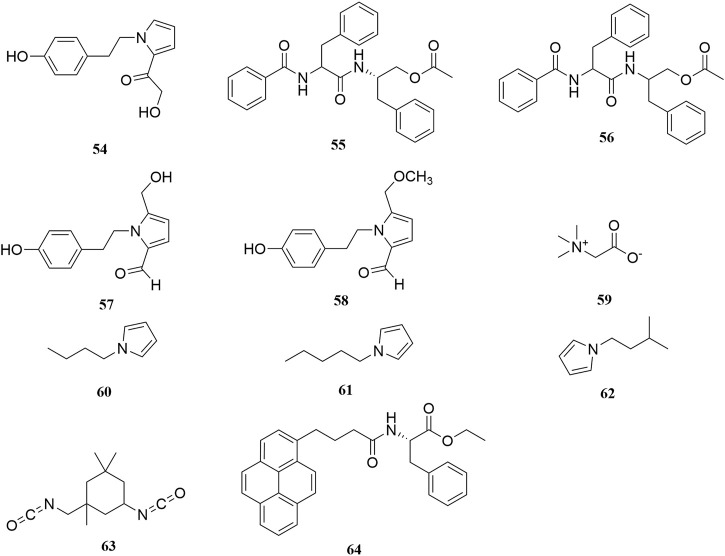

FIGURE 4.

Chemical structures of alkaloids (54–64).

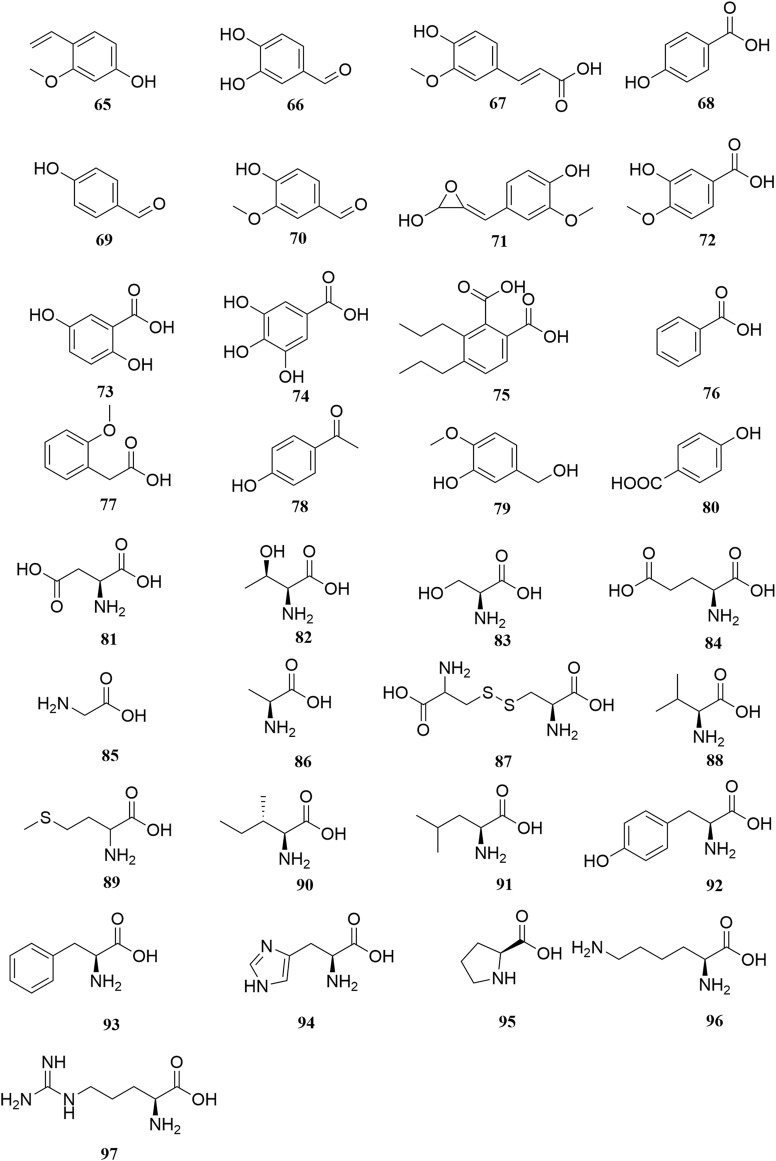

FIGURE 5.

Chemical structures of phenols, phenolic acids and amino acids (65–97).

FIGURE 6.

Chemical structures of saccharides and glycosides (98–110).

FIGURE 7.

Chemical structures of volatile oils (111–168).

Flavonoids

The Fabaceae family is rich in flavonoids, which have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antitumor activity (Wang S. et al., 2019). Flavonoids have been the focus of attention in the field of drug research and development owing to their multiple biological activities and complex mechanisms (Qi and Dong, 2020). So far, over 53 flavonoids (1–53) have been reported in A. sparsifolia, including 30 flavones, 11 isoflavones, five catechins, five proanthocyanidins, and two flavanones (Guo et al., 2016; Ouyang et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2020). There are 26 flavonoid glycosides containing glucose (5–6, 8–9, 15, 20, 28), galactose (2, 46, 53), arabinose (16, 19), rhamnose (23), robinobiose (10, 19), rutinose (4, 11, 13–14, 24), sophorose (17), neohesperidose (43), and trisaccharides (39–41) (Malik et al., 1997; Su et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2017). The parent structures of the flavonoids in A. sparsifolia are flavones, isoflavones, and catechins, all of which have phenolic hydroxyl substituents. Butin (1), the main active monomer in A. sparsifolia, can significantly inhibit the proliferation and migration of human cervical cancer Hela cells, human colon cancer HT-29 cells, human liver cancer HepG2 cells, human gastric cancer BGC823 cells, and human oral epidermoid carcinoma kB cells in vitro and was found to have synergistic anti-tumor effects in combination with 5-fluorouracil (Ma et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2018). Isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside (2), isorhamnetin (3), and isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (4) are the most abundant flavonoids and are often considered important indicators for the quality control of this plant (Xu et al., 2012; Sanawar et al., 2014). Moreover, differences in the total flavonoid content of different parts of the plant have also been reported, with the fruit and aerial parts having the highest content of total flavonoids, suggesting that different medicinal parts can be selected based on clinical use to maximize the utility of this plant (Chen et al., 2014).

Alkaloids

Alkaloids are important chemical compounds and a good research area for drug discovery. Numerous alkaloids screened from medicinal plants are known to exert antiproliferative and anticancer effects in several cancers both in vitro and in vivo (Mondal et al., 2019). To date, seven alkaloids have been isolated from this plant, including two organic amines (59, 63), six pyrrolidines (54, 57–58, 60–62), and three acylamides (55–56, 64) (Cheng, 2010; Zou et al., 2012; Liu G. C. et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2017). Alhagifoline A (54) was the first novel compound isolated from the dried aerial parts of this plant; however, pharmacological studies related to its activity are lacking.

Phenols, Phenolic Acids, and Amino Acids

Thirty-three organic acids including phenols (65–66, 69–71, 78–79), phenolic acids (67–68, 72–77, 80), and amino acids (81–97) have been identified from A. sparsifolia (Liu G. C. et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2018b; Muratova et al., 2019). The substituents of these compounds include hydroxyl, carboxyl, methoxy, amino, and carbonyl groups. Seventeen amino acids have been isolated from the alkaline essential oils of this plant and were reported as the main components of drought resistance in this desert plant (Liu G. C. et al., 2014). The compounds 3-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (65) and 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (66) have been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation in the concentration range of 25–87 μM. Moreover, owing to their selectivity, these compounds may be used in the development of antitumor drugs in the future (Ma et al., 2018).

Saccharides and Glycosides

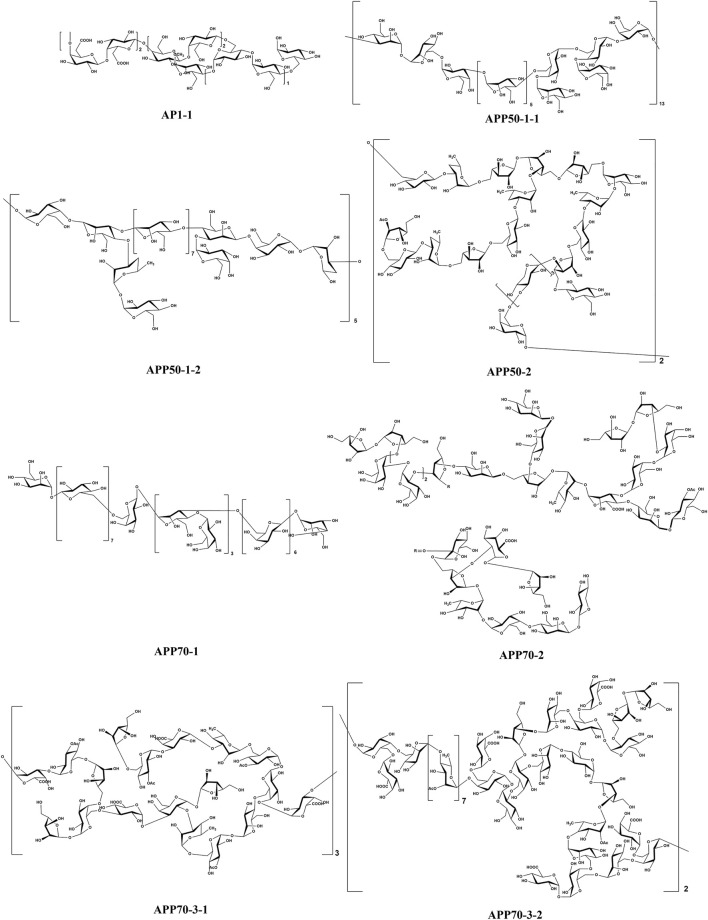

The stems of A. sparsifolia are rich in polysaccharides; thus, the isolation and purification of polysaccharides have been the emphasis of research with respect to the chemical constituents of this plant. The 19 isolated polysaccharides (AP1-1, AP1-2, AP1-3, AP1-4, AP1-5, AP2-1, AP2-2, AP2-3, AP2-4, AP2-5, SAP-1, SAP-1, SAP-3, APP50-1-1, APP50-1-2, APP50-2, APP70-1, APP70-2, APP70-3-1, APP70-3-2) contain different amounts of Rha, Ara, Xyl, Man, Glc, Gal, GlcA, and GalA (Chang et al., 2016; Jian et al., 2012; Jian et al., 2014; Li, 2020; Ma et al., 2018; Zheng, 2016; m). The possible chemical structures of seven of these polysaccharides (AP1-1, APP50-1-1, APP50-1-2, APP50-2, APP70-1, APP70-2, APP70-3-1, APP70-3-2) are summarized in Figure 9. The crude polysaccharide extract of A. sparsifolia and its monomeric components have significant antioxidant activity and can effectively scavenge free radicals in vivo. The higher the molecular weight, the stronger is the scavenging effect (Zhao et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2018). A study has reported the potential hypoglycemic effect of the crude polysaccharide of A. sparsifolia and that different doses can prevent the increase in fasting blood glucose levels in diabetic mice. The hypoglycemic mechanism may not be related to oxidative stress capacity (Zhao, 2016). In addition, two oligosaccharides (103–104) and 11 oxygen-containing glycosides (97–107) have been identified from A. sparsifolia, including alcoholic glycosides (99–102, 105, 107) and phenolic glycosides (97–98, 103–104, 106).

FIGURE 9.

Chemical structures of polysaccharides.

Volatile Oils

To date, 58 volatile oils (111–168) from the secretions of A. sparsifolia have been separated and characterized using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Cheng, 2010; Guo et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2018b). The isolated compounds are mainly composed of small-molecular lipophilic compounds including monoterpenes (142–145, 148–149), a sesquiterpene (160), aliphatic hydrocarbons (111–114, 118–120, 122, 125–127, 156, 159, 162), alicyclic hydrocarbons (115, 121, 123–124, 130, 151, 167), ketones (117, 128–129, 131–133, 135, 137–138, 140–141, 144, 146–147, 150, 152, 155, 157–158, 163–164), alcohols (136, 168), ethers (134, 139, 153–154), and esters (116, 161, 165–166). The structural skeleton of the components consists of five-membered, six-membered, oxygen-containing, and other irregular ring structures. The discovery of several essential oils from A. sparsifolia has significantly enriched its chemical database.

Other Constituents

A few lignans (169–171), sterols (176–177), triterpenes (178), and other compounds with irregular chemical structures (172–175) have been isolated from A. sparsifolia. There is no common structural skeleton among these components. Compounds (169–173) were reported to have dose-dependent anti-neuroinflammatory effects.

Pharmacology

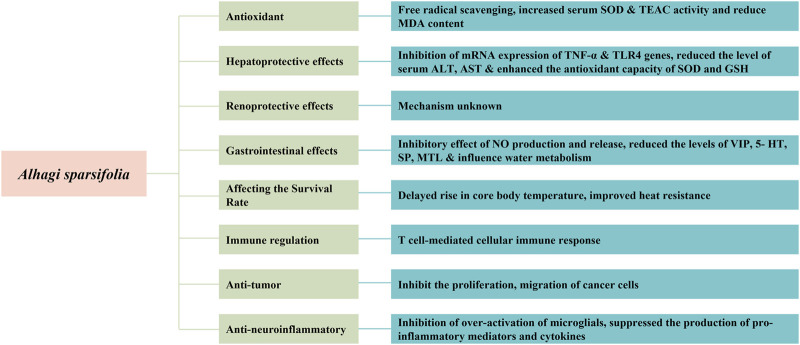

Pharmacological studies have indicated that A. sparsifolia has several pharmacological effects, including antioxidant, hepatoprotective, and renoprotective effects. Moreover, it affects the survival rate of rats in a dry and hot environment and plays a role in immune regulation and has antitumor and anti-neuroinflammatory effects. The pharmacological effects of A. sparsifolia and its monomers are summarized in Table 3 and their possible potential pharmacological mechanisms are summarized in Figure 10.

TABLE 3.

Modern Pharmacological studies of A. sparsifolia.

| Effect | Model | Part of plant/Extracts or compound | Positive control | Formulation/dosage | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antioxidant | SOD, MDA, TEAC | Stem-branch/Curde polysaccharide | Lentinan (630 mg/kg) showed similar in vivo antioxidant activity to the extract | in vivo: 50, 100, 200 mg/kg | Increasing SOD TEAC leveals, decreasing MDA levels | Liu et al. (2021) |

| Hepatoprotective effects | APAP-induced acute liver injury mice | Secretory/Aqueous | Silibinin (300 mg/kg) significantly inhibits ALT, AST activity and alleviates liver lesions caused by APAP | in vivo: 150, 300, 600 mg/kg | Inhibiting the release of ALT and AST caused by APAP overdose and alleviating APAP-induced liver injury and hepatocyte necrosis | Aili et al. (2017) |

| Alcoholic-induced acute liver injury mice | Secretory/Aqueous | Silibinin has a protective effect in mice with alcoholic liver disease | in vivo: 150, 300, 600 mg/kg | promoting alcohol metabolism, reducing the expression levels of TNF-α and TLR4 mRNA, promoting liver tissue repair and hepatocyte regeneration | Kuerbanjiang et al. (2017) | |

| Renoprotective effects | Gentamicin-induced subacute renal injury mice | Secretory/Aqueous | — | in vivo: 350 mg/kg | significant protective effect on renal injury caused by 125 and 80 mg/kg GM, but not on renal injury caused by 100 mg/kg GM | Mikeremu et al. (2013) |

| HgCl2- induced subacute renal injury in mice | Secretory/Aqueous | — | in vivo: 150, 300, 750 mg/kg | Best renal protection at 150 mg/ml | Wumaierjiang et al. (2014) | |

| Gastrointestinal effects | Atropine inhibition and bethanechol chloride promote small bowel motility | Secretory/Aqueous | — | in vivo: 750, 1,500, 3,000 mg/kg | Gastrointestinal motility is stimulated and inhibited by excited gastrointestinal motility | Mikeremu et al. (2017) |

| Diarrheal irritable bowel syndrome rats | Aerial part/ethanol | TrimebutineMaleate (60 mg/kg) improves diarrhoeal irritable bowel syndrome | in vivo: 200, 400 mg/kg | The fecal moisture content, the AWR score and the level of 5- HT, SP, MTL in the high and low dose groups were significantly decreased, and the number of fecal grains increased significantly | Liu et al. (2019b) | |

| Diarrheal irritable bowel syndrome rats | Aerial part/ethanol | TrimebutineMaleate (60 mg/kg) improves diarrhoeal irritable bowel syndrome | in vivo: 200, 400 mg/kg | At the concentration of 400 mg/kg, the extract significantly reduced wall electrical activity and increased NO levels | Ma et al. (2018c) | |

| Affecting the survival rate | dry and hot environment rat | Aerial part/ethanol | — | in vivo: 100, 330, 1,000 mg/kg | Delaying the rise in core body temperature to improve heat tolerance in dry heat tolerance in rats in a dry heat environment | Dong et al. (2019) |

| Immune regulation | RAW264.7 cells in mice | Secretory/Aqueous | Lipopolysaccharide (1,000 μg/ml) promote macrophage proliferation but are less active than extract (100, 200 μg/ml) | in vitro: 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 μg/ml | Promoting macrophage proliferation and having a positive regulatory effect on immune activity | Han et al. (2017) |

| CY and DNCB induced delayed type hypersensitivity of immunosuppression mice | Aerial part/BuOH | — | in vivo: 100, 200, 400 mg/kg | Enhancing the swollen degree of auricle, resisting the atrophy of spleen and thymus and increasing the index of immune organs | Ma et al. (2017) | |

| Anti-tumor | BGC-82, Eca-10, HT-29 and HepG2 cancer cells | Aerial part/ethanol | The IC50 values of Cisplatin for BGC-823, Eca-109, HT-29 and HepG2 cells were 0.019, 0.204, 0.0858, 0.0392 | in vitro: 10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.156, 0.039 mg/ml | The IC50 values of BGC-823, Eca-109, HT-29 and HepG2 cells were 1.62, 1.32, 1.55 and 1.45 mg/ml respectively | Ma et al. (2015) |

| CT26 colon cancer mice | Inhibition rate of 98% in CT26 colon cancer mice by cyclophosphamide (50 mg/kg) | in vivo: 100, 200, 1,000 mg/kg | The inhibition rate was 24.8% in the high dose group, 0.06% in the medium dose group and -0.05% in the low dose group in vivo | |||

| Hela, Ht-29, HepG2, BGC823 and KB tumour cells | Aerial part/EtOAc, BuOH, Compound 11, 65, 66, 98 and 167 | — | in vitro: 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 μg/ml | inhibiting the proliferation and migration of Hela, Ht-29, HepG2, BGC823 and KB tumour cells in a dose-dependent manner | Ma et al. (2018b) | |

| Anti-neuroinflammatory | LPS-induced N9 cells | Aerial part/ethanol | The IC50 values of minocycline for LPS-induced N9 cells was 19.89 | in vitro:/ | Compound 3, 4, 32, 37, 170, 171, 54, and 167 showed much stronger anti-neuroinflammatory effects than minocycline | Zhou et al. (2017) |

FIGURE 10.

Possible mechanisms for pharmacological activit.

Antioxidant

A. sparsifolia supposedly exhibit the mostpotent antioxidant activities determined by TEAC assays. Phytochemical studies have shown that A. sparsifolia is rich in polysaccharide components, which are closely associated with antioxidant effect (Ma et al., 2018). This indicates that the polysaccharides from A. sparsifolia may be a rich source of natural antioxidants that may help prevent and treat diseases related to oxidative stress. Liu et al. (2021) found that the aqueous extract of A. sparsifolia stem and branch (ASSBP) demonstrated dose-dependent moderate antioxidant activity when assayed against TEAC, with serum TEAC levels of mice in the low dose group (50 mg/kg) and medium dose group (100 mg/kg) comparable to the positive control group of Lentinan (630 mg/kg) and slightly higher levels in the high dose group (200 mg/kg). The results showed that ASSBP had certain antioxidant ability and enhanced immune activity in both normal and d-galactose-induced aging mice, increased spleen and thymus indices in normal mice, increased serum SOD activity and decreased MDA content in normal mice. It is suggested that its anti-aging effect may be exerted through anti-lipid peroxidation, increasing SOD activity and decreasing MDA content.

Hepatoprotective Effects

In a study, the aqueous extracts of Tarangabin at the doses of 150, 300, 600 mg/kg had significant hepatoprotective effects at different concentrations in mice with liver injury induced by N-acetyl-para-aminophenol (APAP). It showed a significant decrease in the level of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The results of content determination showed that the polysaccharide content of the extract was as high as 69.2%, thus it is supposed that the polysaccharides have a controlling effect on APAP-induced liver injury (Aili et al., 2017). The hepatoprotective mechanism of Tarangabin has been partly attributed to the reduction of oxidative stress and inhibition of the expression of cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) (Aili et al., 2018). In alcoholic liver disease (ALD), Tarangabin regulates the expression levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) mRNA by acting on the lipopolysaccharide-TLR (LPS-TLR) signaling pathway, thereby improving the severity of ALD. Moreover, this plant is known to bring about the effects of reducing the gene expression of TLR4, inhibiting the release of TNF-α, preventing further signal transmission, reducing the efficiency of endotoxin signal transduction, and decreasing the production of inflammatory factors, thereby preventing hepatocyte damage. Tarangabin promotes liver tissue repair and hepatocyte regeneration and protects from liver injury (Kuerbanjiang et al., 2017; Wang X. L. et al., 2019).

In addition, A. sparsifolia significantly alleviated alcohol-induced liver injury by reducing serum ALT and AST, inhibiting MDA and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and increasing SOD and glutathione (GSH) level in the liver (p < 0.05). Additionally, treatment with A. sparsifolia was found to significantly reduce the expression of TNF-α and TLR4 mRNA in the brain of mice, thus accelerating alcohol metabolism and reducing oxidative stress by downregulating CYP2E1 expression (p < 0.05), which has a protective role in ALD (Kuerbanjiang et al.. 2018).

Renoprotective Effects

Tarangabin supposedly protected against high-dose gentamicin (GM)-induced acute kidney injury in mice. Although the efficacy is attributed to the organic components and Zn, Fe, Cu, Co, Ni, Mn, and K content of Tarangabin, the specific mechanism of action needs to be further elucidated (Mikeremu et al., 2013). Wumaierjiang et al. (2014) found that Tarangabin had a certain protective effect in acute renal failure caused by mercuric chloride, and the best effect was achieved when the concentration of Tarangabin was 15% (Ma et al., 2018).

Gastrointestinal Effects

A. sparsifolia and Tarangabin have a dual regulatory effect on the small intestinal motility in mice. The aqueous extract of A. sparsifolia and Tarangabin could inhibit intestinal propulsion induced by the M-choline receptor blocker, atropine sulfate, and alleviate hyperactivity of small intestinal propulsion induced by the M-choline receptor stimulant, carbamyl-B-methylcholine chloride, in a dose-dependent manner. The dual regulation effect of A. sparsifolia and Tarangabin may be attributed to the high taurine content in the plant. It has been reported that taurine has a dual regulatory effect on intracellular Ca2+. A certain dose of taurine can enhance intestinal smooth muscle contraction, but the effects of different concentrations of taurine on smooth muscle are different. Low and medium doses of taurine enhance smooth muscle contraction, whereas high doses of taurine have the opposite effect (Mikeremu et al., 2017).

In a particular study, male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were subjected to restraint stress and fed a high-lactose diet to establish a diarrhea-predominant model of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D), which was further used to evaluate the regulatory effect of A. sparsifolia extract in IBS-D. The extract was found to significantly reduce the fecal water content and abdominal wall myoelectric activity, and significantly increase the volume threshold of abdominal contractile reflex and serum nitric oxide (NO) levels. Additionally, A. sparsifolia extract was found to improve visceral hypersensitivity and decrease the myoelectric activity of the abdominal wall in IBS rats, which may be related to the decrease in the secretion and release of NO (Wei et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2018c).

In a recent study, Liu et al. (2019b) have shown that in IBS-D rats, A. sparsifolia extract can decrease the abnormally elevated levels of the gastrointestinal hormones, 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), substance P (SP), and motilin (MTL); regulate water metabolism to inhibit gastrointestinal motility and delay gastric emptying; and improve abdominal distension, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, which may be the mechanism of this botanical drug in the treatment of this condition. However, the tension of the intestinal smooth muscle and related intestinal electrolyte levels were not observed in this study, and the vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) levels following the administration of a high dose of A. sparsifolia extract was not higher than that observed after administration of a low dose of the extract. The antagonism between various components in the extract or the effect of some components in the extract as autoinducers may be the likely causes of this abnormal phenomenon.

Affecting the Survival Rate of Rats in a Dry, Hot Environment

The incidence of summer heat strokes and heat radiation in dry and hot desert environments is increasing every year. Dong et al. (2019) found that the desert plant, A. sparsifolia, can improve the heat tolerance of rats in a dry and hot environment by delaying the increase in core body temperature, thereby improving their survival rate in dry and arid conditions.

Immune Regulation

Results from in vitro cellular assays suggested that SAP-1, SAP-2, and AP1-1 promoted the proliferation and cellular immunity of splenic lymphocytes and RAW264.7 macrophages. These components could promote the secretion of cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, and NF-κB. The mechanism of action was via the MyD88-dependent pathway, which activated the immune response of TLR4 receptors (Han et al., 2017). Results from in vivo experiments in mice indicated that the polysaccharide extract could enhance carbon particle scavenging ability, increase serum hemolysin levels in immunosuppressed mice, and also increase serum IL-2 and IL-6 levels in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed mice (Zhao, 2016; Zhao et al., 2016; Qu, 2019). In addition, A. sparsifolia extract was found to significantly increase the number of white blood cells and lymphocytes in peripheral blood, reduce the atrophy of immune organs, improve the ability of lymphocyte transformation in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression, and enhance delayed hypersensitivity in mice (Ma et al., 2017).

Anti-Tumor

The inhibitory effects of ethanol extracts from aerial part of A. sparsifolia on human gastric cancer (BGC-823), human esophageal cancer (Eca-109), human colon cancer (HT-29) and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells were investigated in vitro by MTT assay with IC50 of 1.62, 1.32, 1.55 and 1.45 mg/ml, respectively. To further clarify its in vivo antitumor efficacy, a CT26 mouse model of colon cancer was established. The in vivo tumor-inhibition activity was investigated by comparing the tumor-proliferation rate, growth curve, and tumor-inhibition rate in each group of mice. The results showed that only the high dose (1,000 mg/kg, intragastric × 14 qd) led to significant in vivo antitumor activity with a tumor-inhibition rate of 24.8%. Compared with that in the negative control group, serum IL-2 levels of mice that received a high dose of the extract increased significantly. Thus, the antitumor mechanism may be related to the increase in IL-2 (Ma et al., 2015).

Two active monomers, butin (1) and 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (66), extracted from the n-butanol extract of A. sparsifolia, inhibit the proliferation and migration of human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells and exert a strong inhibitory effect in vitro with synergistic antitumor effects with 5-FU. However, the related targets and signaling pathways of its antitumor effects are still unclear (Liu et al., 2019a). Using Hela cells as the target cells, the proliferation inhibition ability of each different polar extracts on tumor cells was detected by MTT assay, and butanol and ethyl acetate extracts among them were clearly shown to have certain inhibition effect on the proliferation of tumor cells. Further studies proved that butin (1), (+)-tortoside A (98), 3-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (65), 3,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde (66), and 1,3,3,4-tetramethyl-cyclopentene (167) were the active monomers exerting antitumor effects. They also showed good inhibitory effects on HT-29, HepG2, BGC823, and KB tumor cells, exhibiting potential as antitumor agents (Ma et al., 2018b).

Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects

Microglia cells are considered to be key innate immune cells in the central nervous system (CNS) and an important contributor to neuroinflammation. However, microglia cells are particularly sensitive to changes in their microenvironment and readily become activated in response to infection or injury. Under activated conditions, they secrete and release a mass of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and free radical mediators such as nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Accumulation of the pro-inflammatory and neurotoxic factors might aggravate the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. The LPS-stimulated N9 cells were used to evaluate the anti-neuroinflammatory activity of 33 compounds isolated and identified from the ethanol extracts from aerial part of A. sparsifolia. Among the examined constituents, compounds 1, 3, 4, 15, 32, 36, 37, 42, 54, 65, 79, 99, 167, 169, 170, 171, 172, and 173 could considerably inhibit NO production in LPS-induced N9 microglial cells in a dose-independent manner without evident cytotoxicity at the tested concentrations. The effect of 33 compounds on the anti-neuritis activity of N9 cells by MTT assay revealed that flavonoids and lignans exhibited anti-inflammatory effects, whereas their glycosides were not as effective (compound 3 vs 40 [IC50 17.87 vs > 100], 170 vs 105 [IC50 2.68 vs > 100]). In addition, isorhamnetin (3) (IC50 17.87 μM), quercetin (4) (IC50 10.22 μM), 3′,7-dihydroxyl-4′-methoxylisoflavone (32) (IC50 17.43 μM), 3′,7-dihydroxyl-4′,6-dimethoxyl isoflavone (37) (IC50 11.21 μM), syringaresinol (170) (IC50 2.68 μM), bombasinol A (171) (IC50 7.61 μM), aurantiamide (54) (IC50 14.91 μM), and 1,3,3,4-tetramethylcyclopentene (167) (IC50 2.63 μM) showed much stronger anti-neuroinflammatory effects without obvious cytotoxicity at their effective concentration compared with the positive control, minocycline (IC50 19.89 μM). The mechanism of action may be related to the inhibition of excessive activation of microglia and thus the inhibition of the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines (Zhou et al., 2017).

Other Activities

In addition to the above pharmacological effects, the isolated compounds and crude extract of A. sparsifolia showed antibacterial, antidiabetic, and growth-promoting effects. The aqueous extract exhibited good antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and had a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 62.5 mg/ml (Lei et al., 2004). A gavage of the polysaccharide (at a dose of 200 mg/kg) administered to male mice with hyperglycemia significantly suppressed fasting blood glucose levels (Zheng, 2016). Moreover, the polysaccharides were found to exert growth-promoting and hemoglobin-increasing effects in mice (Hairula et al., 2014).

Quality Control

Although Uyghur medicines have shown unique efficacy in the treatment of several diseases and gained increasing attention and recognition, there is still a big gap in the industrialization, standardization, and the mode of standardization of Uyghur medicines. First, there is the problem of poor basic research. According to statistics, there are still about 250 Uyghur drugs without defined standards among the 500 commonly used drugs. Some of the drugs for which standards are available have unclear identification of origin, phenomena of synonym or homonym, translation errors, and unverified Latin names. Secondly, the level of quality standards of plant species used in Uyghur medicine species is low, the number of standardized species is small, and the identification specificity is not strong; thus, effective quality control of Uyghur medicine poses a challenge. Thirdly, the scientific clinical research evaluation system including the clinical efficacy evaluation index and research methods of Uyghur medicine has not been established, and evaluation of the clinical efficacy of Uyghur medicine lacks a standardized, objective, and recognized index. There is a lack of in-depth research and exploration of the rationality of the composition of ethnic medicines, the scientific nature of the process, and the active components of drugs. Therefore, it is crucial to establish complete quality standards and suitable extraction methods for the quality control of A. sparsifolia.

Studies on the Quality Standards of A. sparsifolia

A. sparsifolia, as a common ethnic medicine in Uyghur medicine, has a long history of use. Presently, A. sparsifolia is not included in Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (ChP). With continuous improvements in modern separation and identification methods, some investigators have used various methods to evaluate the chemical compounds and control the quality of A. sparsifolia. For example, Hu (2010) determined the moisture, total ash, leachate, and total flavonoid content of A. sparsifolia in Tuokexun County, Xinjiang, by referring to the identification items and standardized methods in the ChP. The specificity of isorhamnetin (3), isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside (17), and isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside (12) in A. sparsifolia was determined using TLC, whereas the levels of the main chemical component, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, were determined using HPLC and found to be 0.1355%, on average. In the same year, Sanawar et al. (2012) conducted a similar study on 12 A. sparsifolia samples collected from the Turpan region of Xinjiang. In addition, they focused on describing the plant traits and determining isorhamnetin content using HPLC. The average isorhamnetin content was determined to be 0.14%. To improve the credibility and accuracy of the quality standard, the XinJiang Institute of Chinese Traditional Medica and Ethical Materia Medica conducted a more comprehensive quality standard study on samples collected from five different regions in Xinjiang by random sampling. The findings revealed that the impurities did not exceed 0.5%, moisture content did not exceed 10%, and total ash content did not exceed 12%. Moreover, unique TLC and HPLC methods for rutin were established (Xu et al., 2012). In addition, Chen et al. (2014) determined the levels of total polysaccharides and rutin in eight samples of A. sparsifolia using ultraviolet spectrophotometry (UVS) and compared its levels in different parts of the plant. The results showed that the total polysaccharide and rutin content in the fruit and aerial parts were relatively high. In another study, HPLC and similarity evaluations were used to establish the chromatographic fingerprints of 10 A. sparsifolia samples collected from different townships in Tuokexun County, Xinjiang (Sanawar et al., 2013), which revealed 11 common peaks in the fingerprints of A. sparsifolia obtained from 10 habitats. However, there were differences in the peak heights of the common peaks in A. sparsifolia obtained from different habitats, indicating differences in the levels of the primary components of botanical drugs obtained from different sources due to local climate and harvesting time. Guo et al. (2020) were the first to use UPLC-Q-TOF-MS for the qualitative analysis of flavonoids from Tarangabin. Using a web-based database and masslynx 4.1 workstation, 40 compounds were analyzed and identified, of which 22 were reported for the first time. Their study provides a scientific basis for the establishment of a compound database and quality standards. Establishment of quality standards for A. sparsifolia will accelerate its entry into the ChP and provide theoretical support and serve as a reference standard for its use in a clinical setting.

Extraction and Separation Methods

Flavonoids are the main components and active compounds in A. sparsifolia; thus, optimizing their extraction is essential for quality control and ensuring efficacy. Su et al. (2009) found that the extract (1 g: 20 ml) of A. sparsifolia collected from Tuokexun County purified with 40% ethanol (1.5 h × 3 times) could extract 1.70% of the total flavonoid based on orthogonal experiments. At a temperature of 90°C, its extracts (1 g: 20 ml) were purified with 40% ethanol (1 h × 3 times), and the extraction ratio of total flavonoids was 1.33% when A. sparsifolia samples from Urumqi, Xinjiang, were used (Shi et al., 2014). Guo et al. investigated the enrichment ability of AB-8, DM301, and D-101 macroporous resins for total flavonoids in prickly sugars, and finally selected AB-8 resin for the enrichment and purification of total flavonoids from prickly sugars. The ideal extraction process was obtained based on Box-Behnken response-surface optimization, wherein ethanol concentration was 67%, the material:liquid ratio was 1:25, extraction time was 75 min, and extraction temperature was 75°C. The average total flavonoid yield extracted from Tarangabin collected from Hotan, Xinjiang was 0.3889% (Guo et al., 2020).

Toxicology

It is well known that drugs have dual effects, namely therapeutic effects and adverse reactions. In recent years, Uyghur medicines have been widely used and the incidence of adverse reactions has increased accordingly, thereby raising serious questions regarding their safety in a clinical setting. Toxicity studies on Uyghur drugs will help provide a reference for drugs in the treatment of diseases and ensuring the safe use of drugs. Chronic toxicity studies of different doses (3.0, 1.0, 0.3 g/kg) of the total flavonoid extract from the aerial parts of A. sparsifolia in mice show that the routine hematological and biochemical indices after 13 weeks of gavage were not different compared with the control group. Furthermore, no significant differences were found between the control and drug-treated groups, and the isolated organs did not exhibit any pathological changes following drug treatment, indicating that A. sparsifolia extracts to be safe over a wide dose range. Similar results were obtained for the total alkaloid extracts from the aerial parts of A. sparsifolia (Ma et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2014). Nevertheless, these findings constitute insufficient evidence to prove the nontoxicity and safety of A. sparsifolia. Acute toxicity experiments should be conducted to assess the safety and reliability of this drug when administered at regular doses.

Future Outlooks

In this review, we have provided a critical analysis of the botany, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, quality control, and toxicology of A. sparsifolia, which is widely used in the traditional Uyghur system of medicine for the treatment of colds, rheumatic pains, diarrhea, stomach aches, headaches, and toothaches. Modern pharmacological studies have shown the plant components to exert antioxidant, antineuritic, antitumor, immunomodulatory, hepatoprotective, and renoprotective effects. With an improvement in extraction techniques and advancement in pharmacological research, some success has been achieved in determining the chemical composition and pharmacological effects of this plant. However, further studies are warranted for a more thorough understanding. Therefore, we have highlighted and summarized a few topics, which should be investigated further.