Abstract

Background:

Screening for eating disorders via reliable instruments is of high importance for clinical and preventive purposes. Examining the psychometric properties of tools in societies with differing dynamics can help with their external validity. This research specifically aimed at standardization and validation of the eating attitude test (EAT-16) in Iran.

Methods:

The Persian version of the EAT-16 was produced through forward translation, reconciliation, and back translation. The current research design was descriptive cross-sectional (factor analysis). A total of 302 nonclinical students were selected through the convenience sampling method and completed a set of questionnaires. The questionnaires included, the EAT-16, eating beliefs questionnaire-18 (EBQ-18), difficulties in emotion regulation scale-16 (DERS-16), weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire-short form, self-esteem scale, and self-compassion scale short-form. The construct validity of the EAT-16 was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis and divergent and convergent validity. Internal consistency and test–retest reliability (2 weeks’ interval) were used to evaluate the reliability. Data analysis was conducted using LISREL (version 8.8) and SSPS (version 22) software.

Results:

EAT-16 and subscales were found to be valid and reliable, with good internal consistency and good, test–retest reliability in a non-clinical sample. In terms of convergent validity, EAT-16 and subscales showed a positive correlation with the selfreport measures of EBQ-18 and DERS-16. EAT-16 and subscales showed a negative correlation with self-compassion, self-esteem and eating self-efficacy., Therefore, it demonstrated divergent validity with these constructs. The results of this study support the EAT-16 four-factor model.

Conclusions:

The EAT-16 showed good validity and reliability and could be useful in assessing eating disorders in Iranian populations. The EAT-16 is an efficient instrument that is suitable for screening purposes in the nonclinical samples.

Keywords: Eating, factor analysis, psychological tests, psychometrics

Introduction

Eating disorders are serious disorders characterized by perturbation in eating, eating-related behaviors, and disturbance of body weight experience and body shape. They have significant comorbidities with mental and physical disorders.[1] They are associated with an increased risk of mortality,[2] suicide,[3] and impose significant financial burdens on the health system.[4] The prevalence of lifespan of 0.5–1% is reported for anorexia nervosa, 1–3% for bulimia nervosa, and 2–2.5% for binge eating disorder.[5] The term “disordered eating” describes several signs related to body and weight (such as a persistent dieting, weight concerns).[6] Disordered eating is common in the general population. The prevalence of disordered eating in Germany is in the range of 3.9[7] –31.6[8] depending on the screening tool and the common sample. Concerns about weight, diet, and negative body image increase the risk factors for eating disorders.[9] People at the high-risk eating disorders are more prone to comorbid psychiatric disorders including anxiety, depression, and insomnia.[6] They also reported lower quality of life.[10] On the contrary to common assumptions, longitudinal studies have recently shown that disordered eating behaviors become more stable or even increase from childhood to adulthood.[11,12]

Early detection of the people at risk increases the rate of recovery and shortens the time between onset and treatment of the disorders by reducing current impairments.[13] Researchers always need a precise screening tool for eating disorders. This requirement is based on various physical and psychological complications associated with eating disorders.[14] Careful evaluation is important because early screening for eating disorder can accelerate treatment. Some researchers have found that early detection of eating disorder can increase the rate of successful recovery.[15] Therefore, for eating disorders, we need to have a validated screening and measurement tool. There are two internationally known short screening tools for disordered eating namely. The SCOFF (Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food) questionnaire[16] and The Weight Concerns Scale (WCS).[17]

The Weight Concerns Scale (WCS) is quite complex to determine score due to different response statistics.[18] The The SCOFF(Sick, Control, One, Fat, Food) questionnaire has acceptable sensitivity and specificity but its reliability and positive predictive value are low.[8] Eating attitude test -26 (EAT-26) has good psychometric properties in terms of reliability, virility, sensitivity, and acceptable specificity.[19] However, it is long and complex when used for public health survey and increases the cost of them.[20] The use of EAT-16 in student samples is of considerable value due to the high prevalence of eating disorders in this population.[21] Most of the studies on the relationship between eating attitude and vulnerability to psychological problems has been conducted in societies with individualistic and diverse cultures, where understanding about eating can be different from other societies. Investigating psychometric properties of this scale in communities with different cultures can contribute to its external validity.[22] The psychometric properties have been reviewed and validated in studies.[23,24] Given that general health management focuses on the integration of treatment and prevention to reduce the incidence and prevalence of diseases, the first step in health management of a community is having an effective tool to accurately identify people at high risk of eating disorder.[25] Current study was done in order to determine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of EAT-16. Its importance is due to many reasons some of which include: preventing the prevalence and consequences of eating disorders, the lack of a reliable, and valid scale for assessing eating disorders in Iranian population, and its importance in clinical research and treatment.,

Methods

Sample

The current research design was descriptive cross-sectional (factor analysis). In this research, we included the undergraduate students, studying in the 2018–2019 academic year at the University Of Tehran (UT). The suggested sample size for the confirmatory factor analysis is approximately 200.[26] Hence, we recruited 340 nonclinical students by means of convenience sampling. We excluded 38 students due to their incomplete questionnaires. Inclusion criteria: Being a student and consenting to research. Exclusion criteria: Severe medical illness and substance abuse. The anonymous participants had to be fluent in Persian language and accept to fill out the self-report measures. They were assured that they could leave the research at any time. All individuals were required to complete a demographic questionnaire and a set of self-report questionnaires. This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC 1396.9421521003).

Measures

Eating Attitude Test-16

EAT-16 is one of the shortened versions of the EAT-26. The EAT-16 use simple statements for assessing eating thoughts and behaviors. The 16-item EAT contains the following four factors: dieting, self-perception of body shape, food preoccupation, and awareness of food contents. Respondents ranked their agreement based on a six-point Likert scale from “Never” (1) to “Always” (6).[23] This scoring scheme was employed in other research in nonclinical samples.[23,24] EAT-16 has the advantage of having good psychometric properties.[23,24]

The comparability between EAT-16 and the original EAT-16 have been approved by precise translation and back-translation methods. Four PhD candidates in clinical psychology were selected to translate the EAT-16 to Persian independently. Afterward, the Persian EAT-16 was back-translated by an individual bilingual in Persian and English to validate the translation., Moreover, the back-translated version was reviewed by another bilingual person. Furthermore, two bilingual clinical psychologists compared the final version of Persian EAT-16 to the original version.

Self-compassion scale short-form

This scale includes 12 items. Participants are required to state their agreement according to a five-point Likert scale from 1 (nearly never) to 5 (nearly always). This scale evaluates three bipolar components in six subscales: self-compassion versus self-judgment, mindfulness versus over-identification, and common humanity versus isolation. The correlation of the short-form self-compassion scale (SCS) with its long form was 0.97, and test–retest reliability value was reported as 0.92.[27] In Iran, the results support the three-factor structure of self-compassion in a nonclinical sample, with Cronbach's alpha of 0.78.[28]

Self-esteem scale

The Rosenberg self-esteem scale (SES) is a ten-item questionnaire that measures the global self-worth by evaluating both negative and positive feelings toward the self. Factor analysis stated a single common factor. Participants rated their agreement according to a four-point scale, from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” The scoring of this scale is employed directly and reversely. The Rosenberg SES indicated good psychometric properties.[29,30]

Weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire- short form

This questionnaire was used to measure an individual's perceived ability to weight control by the following criteria: Refraining to eat when confronted with negative emotions, availability of food, social pressure in this regard, physical discomfort, and/or positive activities. Weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire- short form (WEL-SF) is an eight-item self-report scale. Items are graded from 0 (not confident) to 10 (very confident). Therefore, the total score lies within the [0, 80] interval. Higher score indicates higher self-efficacy to control eating behaviors. WEL-SF has good psychometric properties for assessing eating self-efficacy.[31] The Iranian version of WEL-SF had good psychometric properties.[32]

Difficulties in emotion regulation scale-16

The difficulties in emotion regulation scale-16 (DERS-16) consists of 16 items. It aims to briefly measure the global difficulties in emotion regulation. Respondents ranked their agreement according to a five-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), indicating how much each statement is true. The DERS-16 has been shown to have a good internal consistency (α = 0.92–.94), test–retest reliability (ρI = 0.85), convergent, and discriminant validity. 16–80 is the range for the total score, with greater scores indicating greater levels of emotion dysregulation.[33] The Persian version of DERS-16 had excellent psychometric properties.[34]

The eating beliefs questionnaire

The eating beliefs questionnaire-18 (EBQ-18) questionnaire contains 18 items. It assesses three aspects of negative, positive, and permissive beliefs about eating and urges to eat when is there is a lack of hunger. Participants ranked their agreement according to a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). EBQ-18 showed psychometric properties. Moreover, this questionnaire is used in both clinical and nonclinical samples.[35]

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics v. 22.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, Chicago, USA, 2013). Internal consistency, convergent validity, divergent validity, and testretest reliability of the Persian version of the EAT-16 was analyzed. Internal consistency was estimated using Cronbach's alpha. An alpha value between. 70 and. 95 indicates high internal consistency.[36] Test–retest reliability was assessed with Pearson correlations and intraclass correlations coefficient (ICC). An ICC ≥0.70 indicates acceptable reproducibility of a measure.[36] Divergent validity and convergent validity were assessed with Pearson correlations. All reported significance values were two-tailed. In all tests, P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The construct validity of the eating attitude scale was evaluated using structural equation modeling. The four-factor structure of the eating attitude scale, as suggested in the original version, was tested with LISREL software (version 8.8). The model parameters were estimated using maximum likelihood. Confirmatory factor analysis indicators are more accurate when the sample is larger than 250.[37] The evaluation of a model is based on a number of fit indices, which are briefly discussed here. The normal Chi-square should be less than three for an acceptable model.[38] The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be <0.08 for acceptable fit, with 0.05 or lower indicating a very good fitting model.[37] The comparative fit index (CFI) ranges from 0 to 1 with the values of 0.90 or greater indicant of good fitting models.[26,37]

Normed fit index (NFI) ≥0.90 indicant of good fitting models.[26] Nonnormed fit index (NNFI) or Tucker-Lewis Index ≥0.90 indicative of good fitting models.[26] The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) ranges from 0 to 1 and the values of 0.08 or less are desired.[26,37] Incremental fit index (IFI) ≥ 0.90 indicant of good fitting models.[18] The goodness of fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), which adjust for the number of parameters, were estimated, ranging from 0 to 1 with the values of 0.90 or greater indicant a good fitting model.[37]

Results

Description of the sample

The present research was conducted on a total of 302 university students, including 169 (56%) male and 133 (44%) female participants with the age range of 19–46. The mean and standard deviation of age scores respectively is 23.83 and 4.57. Demographical features include marital status: 216 single individual (71.52%), 86 married individual (28.47%). Educational status: 188 B.Sc. individual (62.25%), 96 MA individual (31.88%), 18 Ph.D. individual (5.96%).

The mean and standard deviation of EAT-16 and the subscales are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of EAT-16 and the subscale in female and male

| Gender | n | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT-16 | Female | 133 | 40.61 | 14.28 |

| Male | 169 | 40.82 | 14.13 | |

| Self-perception | Female | 133 | 8.61 | 4.08 |

| Male | 169 | 8.71 | 3.50 | |

| Dieting | Female | 133 | 12.23 | 5.32 |

| Male | 169 | 12.32 | 5.21 | |

| Food preoccupation | Female | 133 | 10.21 | 4.76 |

| Male | 169 | 10.46 | 4.91 | |

| Food contents | Female | 133 | 9.55 | 4.32 |

| Male | 169 | 9.32 | 3.72 |

EAT-16=Eating attitude test-16; SD=standard deviation

Internal consistency

Cronbach's alphas were calculated with the total sample (n = 302) [Table 2]. EAT-16 subscales were found to have a good internal consistency. Thus, it meets the Terwee criteria for adequacy for internal consistency.[36]

Table 2.

Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients) for the EAT-16 score and 4 subscales

| Number of items | Cronbach’s alpha | |

|---|---|---|

| EAT-16 total | 16 | 0.88 |

| Self-perception | 3 | 0.68 |

| Dieting | 5 | 0.78 |

| Food preoccupation | 4 | 0.81 |

| Food contents | 4 | 0.76 |

EAT-16=Eating attitude test-16

Test–retest reliability

Test–retest reliability was calculated for the EAT-16 total and the four subscales while using a sample of 31 university participants who completed the EAT-16 a second time after an interval of 2 weeks. Results showed good test–retest reliability across the EAT-16 and all four subscales with significant Pearson correlation and ICC between Time 1 and Time 2 scores, [Table 3].

Table 3.

Means (standard deviations) and test-retest reliability the EAT-16 score and four subscales

| Time 1 | Time 2 | ICC | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAT-16 total | 72.74 (12.05) | 66.03 (13.18) | 0.90 | <0.01 |

| Self-perception | 12.87 (3.12) | 11.80 (3.05) | 0.87 | <0.01 |

| Dieting | 23.22 (4.20) | 21.77 (4.38) | 0.88 | <0.01 |

| Food preoccupation | 18.83 (3.98) | 15.67 (4.22) | 0.83 | <0.01 |

| Food contents | 17.80 (4.16) | 16.77 (3.49) | 0.87 | <0.01 |

EAT-16=Eating attitude test-16; ICC=Intraclass correlation coefficient

Convergent and divergent validity of the EAT-16

The convergent validity of the EAT-16 was investigated by examining the relationship between EAT-16 subscales with scores on self-report measures of EBQ-18 and DERS-16. The results demonstrated the expected relationship between the EAT-16 subscales and EBQ-18 and DERS-16. Positive correlations were found between the EAT-16 subscales with these two scales (P < 01). To evaluate the divergent validity of EAT-16 subscales, we examined the association between the EAT-16 subscales and three theoretically less related constructs, including self-compassion, self-esteem, and self-efficacy. As expected, we found negative correlations between EAT-16 subscales and these three scales (P < 0.01) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Convergent and divergent validity of the EAT-16

| Scale | EAT-16 | Self-perception | Dieting | Food preoccupation | Food contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBQ-18 | 0.58** | 0.39** | 0.52** | 0.76** | 0.09 |

| DERS-16 | 0.62** | 0.54** | 0.57** | 0.51** | 0.30** |

| Self-compassion | −0.46** | −0.37** | −0.45** | −0.56** | −0.31** |

| Self-esteem | −0.42** | −0.34** | −0.43** | −0.46** | −0.03 |

| WEL-SF | −0.47** | −0.36** | −0.42** | −0.59** | −0.08 |

**Correlation is significant at 0.01 level. EAT-16=Eating attitudes test-16; DERS-16=Difficulties in emotion regulation scale-16; EBQ-18=Eating beliefs questionnaire-18; Self-compassion scale (SCS) short-form; Self-esteem scale; WEL-SF=Weight efficacy and lifestyle questionnaire: short-form

Confirmatory factor analysis

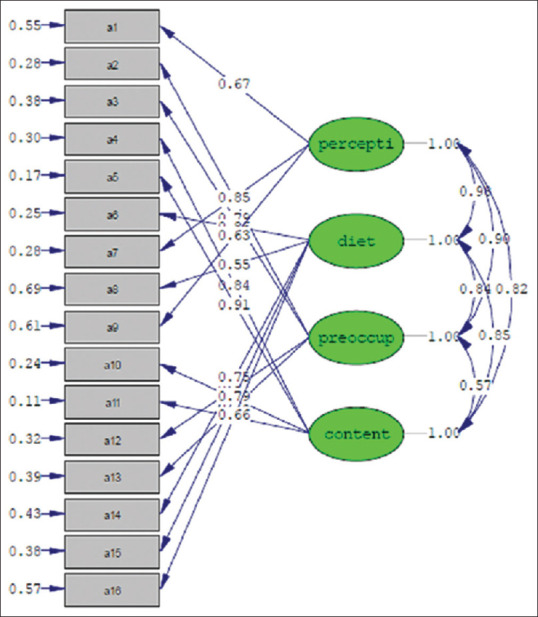

To assess the construct validity of EAT-16 and determine the fit of the factor and subscales structure obtained by McLaughlin et al.[23,39] Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. Based on the results of EAT-16, the four-factor model was tested [Table 5]. As it can be observed, the four-factor model fitted the data well. The results indicated a reasonable fit. The results of the fit indices for this model are summarized in Figure 1.

Table 5.

Goodness of fit indices for four-factor model of EAT-16

| Fit indices | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | IFI | FI | SRMR | NNFI | NFI | GFI | RFI | AGFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | 440.99 | 97 | 4/54 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.78 |

AGFI=Adjusted goodness of fit index, CFI=Comparative fit index, EAT-16=Eating attitude test-16; GFI=Goodness of fit index, IFI=Incremental fit index, NFI=Normed fit index, NNFI=Nonormed fit index, RFI=RMSE=Root mean square error of approximation, SRMR=Standardized root mean square residual

Figure 1.

Construct validity of Persian version of eating attitude test-16

Discussion

Eating disorders are serious disorders with high psychiatric and physiologic comorbidities which often appear with complicated and chronic periods. Preventing these types of disorders and identifying prone individuals are crucial for general health practice.[18] The EAT-16 is a potentially useful short screening tool in this regard. The present study aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of EAT-16 in a nonclinical population of students. The results showed that four factors: self-perception of body shape, dieting, food preoccupation, and awareness of food contents had an acceptable fit. These obtained results are also consistent with the examination of the factor structure EAT-16 with a nonclinical sample.[23,39] The normal Chi-square should be less than 3 for an appropriate model,[38] But in our study, χ2/df was greater than 3 (4.54), indicating a poor fit of the data to the original model. Because this test is very sensitive to sample size and could overestimate the lack of model fit accompanied by increasing sample size and a fixed number of degree of freedom, the χ2 value increases. This mark to the problem that plausible models might be rejected.[40] Assessment of multiple aspects of model fit using fit statistics not biased by the high sample size. We concluded that the literature-based four-factor model had an acceptable fit to our data in the CFA based on robust-variance versions of CFI, NNFI, SRMR, and RMSEA, not Chi-square tests. Test–retest reliability over 2 weeks with a sample of 31 university students yielded significant ICC for the EAT-16 and subscales. The EBQ-18 and DERS-16 were used to evaluate convergent validities of the EAT-16. According to the results, it was revealed that EAT-16 and subscales had a positive correlation with EBQ-18. These results are in consistent with other studies+.[35,41] EAT-16 and subscales had a positive correlation with DERS-16. These results are in consistent with other study.[42,43] To explaining the result, individual with eating disorders may have some personal vulnerability such as emotional- sensitive reactivity and experience of invalid response, which cause them to apply dysfunctional emotional strategy like rumination and thought suppression in response to negative affect. The results showed that EAT-16 and subscales had a negative correlation with self-compassion,[44,45] self-esteem,[46,47] and eating self-efficacy.[48,49,50] To explaining the result, self-efficacy is a significant factor which enables the individual to managing emotions and stressful situation successfully. it also helps to feel more effective and having more positive self-evaluation. Self-compassion can be seen as an emotional strategy in which negative feelings are viewed consciously and creates a sense of shared human experience in the individual. People with high self-compassion are less likely to judge themselves negatively, and they are mindful about negative experiences. However, eating disorders patients who do not consciously deal with painful events blame themselves and consider themselves the only ones who suffer the most from the problems.[51] The results of the CFA supported the application of the four-factor structure in a nonclinical population of students.

The main benefit of the research is its contribution to screening in nonclinical college samples. It is significant to note that this research has some limitations. First, all scales contained in this study were self-report questionnaires. Therefore, correlations may have been inflated by common method variance. Second, eating attitudes were measured by self-report and not verified by an assessment from a mental health professional. Third, the study sample was restricted to subjects with certain demographic characteristics: They were all university students and were often single, young, well-educated, and male. This may lead to a problem of generalizing the results to the general population. The sample is not diverse adequate to be merely relied on as a normative reference in clinical decision making. In the present research, a short time and a small sample size were used for test–retest reliability. Thus, the psychometric properties of the EAT-16 should be assessed in other communities and related sample groups. Subsequent research will be used for longer periods of time and greater sample sizes for test-retest reliability. Future research is required to affirm its validity across different populations.

Conclusions

The Persian version of EAT-16 showed good and reliable validity to measure eating disorders in a nonclinical population of students as well as the study supplements the literature on the cross-cultural validity of this measure. Therefore, providing more support for the generalizability of the relation of eating attitudes and some previously studied psychopathologies. The results of this paper add to the existing literature on the relevance of the eating disorders that were measured by this questionnaire. The EAT-16 promising results as a measure used in eating research and clinical practice. It is recommended to use the EAT-16 in other studies. The EAT-16 is a valid screening measure in nonclinical samples.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study is entirely self-funded by the author, there is no external funding.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate those students at Tehran University, who participated in this study. The authors wish them all the best in their future career in their beloved country.

References

- 1.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:714–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keshaviah A, Edkins K, Hastings ER, Krishna M, Franko DL, Herzog DB, et al. Re-examining premature mortality in anorexia nervosa: A meta-analysis redux. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1773–84. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith AR, Velkoff EA, Ribeiro JD, Franklin J. Are eating disorders and related symptoms risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors? A meta-analysis. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49:221–39. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erskine HE, Whiteford HA, Pike KM. The global burden of eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29:346–53. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aspen V, Weisman H, Vannucci A, Nafiz N, Gredysa D, Kass AE, et al. Psychiatric co-morbidity in women presenting across the continuum of disordered eating. Eat Behav. 2014;15:686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilbert A, De Zwaan M, Braehler E. How frequent are eating disturbances in the population? Norms of the eating disorder examination-questionnaire. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29125. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger U, Wick K, Hölling H, Schlack R, Bormann B, Brix C, et al. Screening of disordered eating in 12-Year-old girls and boys: Psychometric analysis of the German versions of SCOFF and EAT-26. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2011;61:311–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:587–97. doi: 10.1037/a0016481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanftner JL. Quality of life in relation to psychosocial risk variables for eating disorders in women and men. Eat Behav. 2011;12:136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Dempfle A, Konrad K, Klasen F, Ravens-Sieberer U BELLA Study Group. Eating disorder symptoms do not just disappear: The implications of adolescent eating-disordered behaviour for body weight and mental health in young adulthood. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24:675–84. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0610-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loth KA, MacLehose R, Bucchianeri M, Crow S, Neumark-Sztainer D. Predictors of dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:705–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richter F, Strauss B, Braehler E, Altmann U, Berger U. Psychometric properties of a short version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-8) in a German representative sample. Eat Behav. 2016;21:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cumella EJ. Obsessive-compulsive disorder with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:982. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoemaker C. Does early intervention improve the prognosis in anorexia nervosa? A systematic review of the treatment-outcome literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199701)21:1<1::aid-eat1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319:1467–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Killen JD, Hayward C, Wilson DM, Taylor CB, Hammer LD, Litt I, et al. Factors associated with eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of 6th and 7th grade girls. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;15:357–67. doi: 10.1002/eat.2260150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richter F, Strauss B, Braehler E, Altmann U, Berger U. Psychometric properties of a short version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-8) in a German representative sample. Eat Behav. 2016;21:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garfinkel PE, Newman A. The eating attitudes test: twenty-five years later. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2001;6:1–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03339747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berger U, Hentrich I, Wick K, Bormann B, Brix C, Sowa M, et al. Psychometric quality of the” Eating Attitudes Test” (German version EAT-26D) for measuring disordered eating in pre-adolescents and proposal for a 13-item short version. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2012;62:223–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1308994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB, Daniels S, Crawford PB, et al. Eating disorders in white and black women. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1326–31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadian Y, Mahaki B, Lavasani FF, Dehghani M, Vahid MA. The psychometric properties of the Persian version of interpersonal sensitivity measure. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:10. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.199093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin E. The EAT-16: Validation of a Shortened Form of the Eating Attitudes Test. 2014. Available from: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/psy_etds/94 .

- 24.Belon KE, Smith JE, Bryan AD, Lash DN, Winn JL, Gianini LM. Measurement invariance of the Eating Attitudes Test-26 in Caucasian and Hispanic women. Eat Behav. 2011;12:317–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin SB. Accelerating progress in eating disorders prevention: A call for policy translation research and training. Eat Disord. 2016;24:6–19. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1034056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 4th ed. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18:250–5. doi: 10.1002/cpp.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanjani S, Foroughi AA, Sadghi K, Bahrainian SA. [Psychometric properties of Iranian version of self-compassionscale (short form)] Pajoohande. 2016;21:282–9. Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent selfimage. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moshki M, Ashtarian H. Perceived health locus of control, self-esteem, and its relations to psychological well-being status in Iranian students. Iran J Public Health. 2010;39:70–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ames GE, Heckman MG, Grothe KB, Clark MM. Eating self-efficacy: Development of a short-form WEL. Eat Behav. 2012;13:375–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmadipour H, Ebadi S. Psychometric properties of the persian version of weight efficacy lifestyle questionnaire-short form. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:71. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_361_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjureberg J, Ljótsson B, Tull MT, Hedman E, Sahlin H, Lundh LG, et al. Development and validation of a brief version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale: The DERS-16. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2016;38:284–96. doi: 10.1007/s10862-015-9514-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahabi M, Hasani J, Bjureberg J. Psychometric properties of the brief Persian version of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale (the DERS-16) Assess Eff Interv. 2018 doi: 1534508418800210. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton A, Mitchison D, Hay P, Donnelly B, Thornton C, Russell J, et al. Beliefs about binge eating: Psychometric properties of the eating beliefs questionnaire (EBQ-18) in eating disorder, obese, and community samples. Nutrients. 2018;10:1306. doi: 10.3390/nu10091306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodnessoffit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:430–45. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ocker LB, Lam ET, Jensen BE, Zhang JJ. Psychometric properties of the eating attitudes test. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2007;11:25–48. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online. 2003;8:23–74. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burton AL, Abbott MJ. The revised short-form of the Eating Beliefs Questionnaire: Measuring positive, negative, and permissive beliefs about binge eating. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:37. doi: 10.1186/s40337-018-0224-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brockmeyer T, Skunde M, Wu M, Bresslein E, Rudofsky G, Herzog W, et al. Difficulties in emotion regulation across the spectrum of eating disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:565–71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, et al. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in bulimia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22:212–6. doi: 10.1002/erv.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fresnics AA, Wang SB, Borders A. The unique associations between self-compassion and eating disorder psychopathology and the mediating role of rumination. Psychiatry Res. 2019;274:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun TD, Park CL, Gorin A. Self-compassion, body image, and disordered eating: A review of the literature. Body Image. 2016;17:117–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Collin P, Karatzias T, Power K, Howard R, Grierson D, Yellowlees A. Multi-dimensional self-esteem and magnitude of change in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2016;237:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linardon J, de la Piedad Garcia X, Brennan L. Predictors, moderators, and mediators of treatment outcome following manualised cognitive-behavioural therapy for eating disorders: A systematic review. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2017;25:3–12. doi: 10.1002/erv.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vall E, Wade TD. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:946–71. doi: 10.1002/eat.22411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glasofer DR, Haaga DA, Hannallah L, Field SE, Kozlosky M, Reynolds J, et al. Self-efficacy beliefs and eating behavior in adolescent girls at-risk for excess weight gain and binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:663–8. doi: 10.1002/eat.22160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keshen A, Helson T, Town J, Warren K. Self-efficacy as a predictor of treatment outcome in an outpatient eating disorder program. Eat Disord. 2017;25:406–19. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2017.1324073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steindl SR, Buchanan K, Goss K, Allan S. Compassion focused therapy for eating disorders: A qualitative review and recommendations for further applications. Clin Psychol. 2017;21:62–73. [Google Scholar]