Abstract

Objective:

Pathogenic variants in SCN3A, encoding the voltage-gated sodium channel subunit Nav1.3, cause severe childhood-onset epilepsy and malformation of cortical development. Here, we define the spectrum of clinical, genetic, and neuroimaging features of SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder.

Methods:

Patients were ascertained via an international collaborative network. We compared sodium channels containing wild-type vs. variant Nav1.3 subunits co-expressed with β1 and β2 subunits using whole-cell voltage clamp electrophysiological recordings in a heterologous mammalian system (HEK-293T cells).

Results:

Of 22 patients with pathogenic SCN3A variants, most had treatment-resistant epilepsy beginning in the first year of life (16/21, 76%; median onset, 2 weeks), with severe or profound developmental delay (15/20; 75%). Many, but not all (15/19; 79%), exhibited malformations of cortical development. Pathogenic variants clustered in transmembrane segments 4-6 of domains II-IV. Most pathogenic missense variants tested (10/11; 91%) displayed gain of channel function, with increased persistent current and/or a leftward shift in the voltage dependence of activation, and all variants associated with malformation of cortical development exhibited gain of channel function. One variant (p.Ile1468Arg) exhibited mixed effects, with gain and partial loss of function. Two variants demonstrated loss of channel function.

Interpretation:

Our study defines SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder along a spectrum of severity, but typically including epilepsy and severe or profound developmental delay/intellectual disability. Malformations of cortical development are a characteristic feature of this unusual channelopathy syndrome, present in over 75% of affected individuals. Gain of function at the channel level in developing neurons is likely an important mechanism of disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: SCN3A, Nav1.3, sodium channels, epilepsy, polymicrogyria

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium (Na+) channels are macromolecular complexes that underlie the generation and propagation of the action potential and hence are critical regulators of electrical excitability, including in neurons of the brain.1,2 Na+ channels are also known to contribute to the function of glia.3 Variation in genes encoding Na+ channel pore-forming α and auxiliary β subunits are highly associated with human disease, with the prominent brain-expressed Na+ channel genes SCN1A, 2A, 3A, and 8A, and SCN1B linked to epilepsy.4-11

SCN3A encodes the type III voltage gated Na+ channel α subunit Nav1.3, which is highly expressed in embryonic brain,12,13 with postnatal expression levels being low or undetectable.14,15 Prior studies reported heterozygous variants of uncertain significance in SCN3A in patients with mild nonspecific forms of epilepsy.16-20 A de novo heterozygous pathogenic variant p.Lys247Pro in SCN3A has been described in a child with focal epilepsy and moderate-to-severe global developmental delay, with electrophysiological characterization of heterologously-expressed Na+ channels containing Nav1.3-p.Lys247Pro variant subunits exhibiting loss of channel function with markedly decreased cell surface expression and current density.17

De novo pathogenic variants in SCN3A were recently established as a cause of developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE).11 Two patients in that initial cohort, both with SCN3A-p.Ile875Thr, also exhibited diffuse polymicrogyria (PMG), although other patients with a similar phenotype had a near-normal MRI without malformation of cortical development. A subsequent report described two additional cases of de novo SCN3A-p.Ile875Thr variant in conjunction with DEE and diffuse PMG.21 Genetic investigation in a separate cohort of patients with malformations of cortical development of unknown cause, some of whom did not have seizures/epilepsy, identified pathogenic variants in SCN3A as a cause of PMG and provided strong experimental evidence supporting this association.22 A recent report described two additional patients with neurodevelopmental disorders that included epilepsy and intellectual disability, one of whom also exhibited PMG (while the other had a normal MRI).23 The full phenotypic spectrum of this emerging condition has yet to be fully explored. In particular, the extent of overlap between epilepsy, intellectual disability, and brain malformation – the latter being an unusual feature of a channelopathy – remains unclear.

Here, we provide detailed clinical and genetic data on 22 patients with pathogenic variants in SCN3A and also performed electrophysiological characterization of Na+ channels containing the associated variant Nav1.3 subunits expressed in heterologous systems. We establish that malformations of cortical development are a key clinical feature of SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder, which occurs along a clinical spectrum of disease that includes seizures/epilepsy and malformation of cortical development, typically accompanied by developmental delay/intellectual disability of variable but frequently severe to profound degree.

Subjects and methods

Study participants

Individuals with SCN3A variants were ascertained via an international collaborative network. Patients 6, 14, and 19 were ascertained from the Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study.24 The remaining participants were referred from collaborating researchers and clinicians. The investigators entered SCN3A into GeneMatcher, although no additional cases were added through this resource. Detailed information including medical, developmental, and epilepsy history, and pertinent findings of physical, dysmorphology, and neurological examination, was provided for each participant. Available brain imaging and EEG data were reviewed for all participants. Epilepsy syndromes and seizure types were classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification criteria.25,26 This study was approved by the local institutional review boards of the participating centers. Informed consent for participation was provided by all participants, or parents or legal guardians of minors or of individuals with intellectual disability, where applicable.

Genetic analysis

Exome sequencing (ES) was performed on patient-parent trios for Patients 1-4, 6-11, 14-16, 18-21, as previously described.27-30 Patient 13 underwent ES as a mother-proband duo due to unavailability of paternal DNA sample. Proband-only ES was performed for Patients 12, 22, and 23.31 Patient 17 underwent a diagnostic next generation sequencing (NGS)-based testing panel for brain malformations. Patient 5 underwent targeted Sanger sequencing of SCN3A. All candidate variants identified via ES and NGS panel testing were validated by Sanger sequencing. Parental relationships were confirmed for Patients 12 and 22 by short tandem repeat analysis.

Variant interpretation

All identified SCN3A variants were interpreted according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants.32 SCN3A variants were considered likely pathogenic if at least two of the following criteria were satisfied: (1) confirmed to have occurred de novo in the affected individual with confirmed parental relationships; (2) not observed in a control cohort of 123,136 individuals in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) or genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD; http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org)33 (3) electrophysiology demonstrated an abnormal effect of the variant on the function of Nav1.3-containing Na+ channels.

Cell culture and transfection

Cell culture, transfections, and electrophysiological experiments were performed using HEK-293T cells (CRL-3216; ATCC), a mammalian cell line optimized for ion channel expression, as previously described.11 Cells were grown at 37°C with 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and penicillin (50 U/mL)-streptomycin (50 μg/mL).

Variants were introduced via site-directed mutagenesis into a plasmid encoding the major splice isoform of human SCN3A (isoform 2; Reference Sequence NP_001075145.1). Constructs were propagated in STBL2 cells at 30 °C (Invitrogen). All plasmids were resequenced prior to transfection. Plasmids encoding human Na+ channel auxiliary subunits β1 (hβ1-V5-2A-dsRed) and β2 (pGFP-IRES- hβ2) were co-transfected in vectors containing marker genes facilitating identification of cells expressing all three constructs (Nav1.3, Navβ1, and Navβ2). Transient transfection was performed with 2 μg of total cDNA at a ratio of Nav1.3, β1, and β2 of 10:1:1 using Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen) transfection reagent. Cells were incubated for 48 hours after transfection prior to electrophysiological recording. Transfected cells were dissociated by brief exposure to trypsin/EDTA, re-suspended in supplemented DMEM medium, plated on 15 mm glass coverslips, and allowed to recover for at least 4 hours at 37 °C in 5% CO2 prior to recording.

Voltage-clamp electrophysiology

Electrophysiological experiments were performed as previously described.11 Extracellular solution contained, in mM: NaCl, 145; KCl, 4.0; CaCl2, 1.8; MgCl2, 1.8; glucose, 10; HEPES, 10. pH was adjusted to 7.30 with NaOH and osmolarity was adjusted to 285-295 mOsm/L with 30% sucrose as needed. In a subset of experiments, we used a partial replacement of NaCl with choline chloride (in mM: NaCl, 108.75; choline chloride, 36.25). Intracellular pipette-filling solution contained, in mM: CsF, 110; NaF, 10; CsCl, 20; EGTA, 2.0; HEPES, 10. pH was adjusted to 7.35 with CsOH and osmolarity to 305 mOsm/L with sucrose.

Recording electrodes were fashioned from thin-walled borosilicate glass (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) using a two-stage upright puller (PC-10, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan), fire-polished using a microforge (MF-830; Narishige), and wrapped in parafilm. The resistance of pipettes when placed in extracellular solution was 2.4 ± 0.7 MΩ (mean ± s.d.; n = 396). Cells that were positive for both RFP (β1 expression) and GFP (β2 expression) and exhibited fast transient inward current consistent with a voltage-gated Na+ current were selected for subsequent analysis.

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1° C) using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Recordings were initiated after 10 minutes of equilibration, after which recorded currents were found to be stable. Voltage errors were reduced via partial series resistance compensation (50-80%) and rejection of recordings in which absolute peak currents were larger than 10 nA. Voltage clamp pulses were generated using Clampex 10.7, acquired at 10 kHz, and filtered at 5 kHz.

The voltage dependence of channel activation was determined using a protocol that consisted of a series of 20 millisecond steps from a holding potential of −120 mV to potentials ranging from −80 mV to a maximum of 40 mV, in 5 mV increments, with a 10 second inter-sweep interval. Current was converted to current density (pA/pF) by normalizing to cell capacitance. Conductance measures were derived using G = I / (V - ENa) where G is conductance, I is current, V is voltage, and ENa the calculated equilibrium potential for sodium (+68.0 mV). Conductance was normalized to maximum conductance, which was fit with a Boltzmann function to determine the voltage at half-maximal channel activation (V1/2 of activation) and slope factor k.

Slowly inactivating/“persistent” current was measured as the average value of the current response in the last 10 ms of a 200 ms test pulse to −10 mV. In a subset of dedicated experiments, persistent current was isolated by subtracting traces recorded after subsequent addition of either 500 nM TTX or 1 μM ICA-121431 (Tocris Bioscience).34

The effect of holding potential on channel inactivation (prepulse voltage dependence) and was determined using a 100 millisecond prepulse to various potentials from a holding potential of −120 mV, followed by a 20 millisecond test pulse to −10 mV. Normalized conductance was plotted against voltage and fit with a Boltzmann function to determine the voltage at half-maximal inactivation (V1/2 of inactivation) and slope factor k.

Kinetics of recovery from channel inactivation was determined using a brief (1-second) prepulse to −10 mV from a holding potential of −120 mV, followed by a variable time delay to a 10 ms test pulse to a potential of −10 mV. Data was fit with a double exponential function to determine the first (τ1) and second (τ2) time constants of recovery, and their relative weights.

Statistical analysis

Data for standard electrophysiological parameters was obtained from at least n = 20 cells per group, with only 1 cell recorded from each coverslip, from at least n = 3 separate transfections for each experiment. Data were analyzed using Clampfit or using custom scripts written in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA), and statistics were generated using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA), GraphPad Prism (Graphpad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA) and Sigma Plot 11 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) and statistical significance was established using the p value calculated via one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, as appropriate, with the p value reported exactly.

Experiments and analysis were performed blind to genotype via use of tubes labeled with a blind code.

Results

Genetic analysis

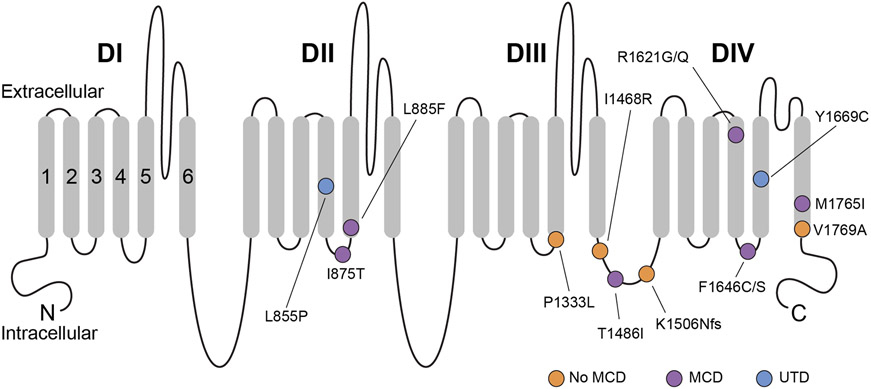

Molecular genetic testing identified 15 unique variants in SCN3A (NM_006922.3) in 23 cases (Table 1). Eighteen patients are newly reported here; five patients had been previously described.11,23 Twenty-two of 23 cases were classified as having likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants; the remaining variant was classified as a variant of uncertain significance (Table 1). De novo status of the variants and parentage were confirmed for 17/22 individuals with likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants. Two individuals (Patients 15 and 16) were part of a small autosomal dominant family. Three recurrent variants, c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr (n = 6), c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys (n = 3), and c.5306T>C; p.Val1769Ala (n = 2), accounted for 50% of patients (11/22). All of the likely pathogenic or pathogenic missense variants occurred at amino acid residues that were highly conserved among paralogous human Na+ channel genes and across phylogeny and were preferentially clustered in transmembrane segments S4-S6 of domains II-IV (Fig 1). All likely pathogenic or pathogenic variants were predicted to be damaging by in silico prediction models and were absent from gnomAD (Supplementary Table 1), with the exception of p.Arg1621Gln, which was apparently mosaic in one individual in gnomAD, being observed in approximately 20% of alleles with a read depth of >100X. The p.Arg1621Gln variant is absent from the subset of 114,704 individuals in gnomAD designated for neurological case/control studies (i.e., “non-neuro” subset determined to not have a neurological condition), which suggests that the individual in the larger gnomAD dataset who is mosaic for the p.Arg1621Gln variant may have an underlying neurological condition. The p.Arg1621Gln has been previously classified in ClinVar as likely pathogenic and was identified in an unrelated individual not reported here.

Table 1.

Features of patients with pathogenic/likely pathogenic SCN3A variants

| Patient | Age (sex) | Variant (NM_006922.3) | Seizure types (onset of first seizure) |

EEG | Brain MRI | Neurological exam |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17w fetus (F) | c.25647T>C; p.Leu855Pro de novo | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 27 | 13y (M) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr de novo | T w/autonomic features (2w), Myo | Multifocal | Bilateral PMG | Central hypotonia, spastic quadriplegia; profound ID: NV, NW |

| 37 | 3y (F) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr de novo | T (2w) | Multifocal | Bilateral PMG | Central hypotonia, spastic quadriplegia; severe DD |

| 4 | 2y (F) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr de novo | FA (2w), T (2w) | Multifocal | Cortical thickening; diffuse PMG | Central hypotonia; severe DD |

| 5 | 16y (F) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr unknown inheritance | FA (1w), T, FMyo, GTCS | GSSW, GPSW | Bilateral PMG | Spastic quadriplegia; severe ID |

| 6 | 12y (M) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr de novo | Unknown (1w) | NA | Bilateral PMG | Spasticity; profound ID |

| 7 | 1.5y (M) | c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr de novo | FIAS (8m) | Multifocal | Bilateral PMG | Central hypotonia; profound DD |

| 8 | 1.2y (F) | c.2653C>T; p.Leu885Phe de novo | HC (2d), T, C, SE | Burst suppression; hyps | Frontal pachygyria; Hypoplastic CC | Spastic quadriplegia, axial hypotonia; profound DD |

| 97 | <4y‡ (M) | c.3998C>T; p.Pro1333Leu de novo | T (1d), FM, HC, GTCS | Hyps; multifocal | Hypoplastic CC | Hypotonia; profound DD |

| 10 | 10m‡ (F) | c.4403T>G; p.Ile1468Arg de novo | ES (6m), T, FT | Modified hyps; multifocal | Normal | Profound axial hypotonia; profound DD |

| 11 | 6y (M) | c.4457C>T; p.Thr1486Ile de novo | FA (1w) | GSSW | Bilateral PMG | Pseudobulbar palsy; Severe ID |

| 12 | 4y (F) | c.4518delA; p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 de novo | ES (2m), T | Hyps; multifocal | Hypoplastic CC; bilateral frontal atrophy | Hypotonia; profound DD |

| 13 | 15y (M) | c.4861C>G; p.Arg1621Gly not maternally inherited | T (4m), T w/autonomic features, FIAS | Bilateral SW | Bilateral PMG | Pseudobulbar palsy; severe ID |

| 14 | 29y (M) | c.4862G>A; p.Arg1621Gln de novo | FS (5y), Single GTCS | Normal | Bilateral PMG (Head CT) | Severe ID |

| 15 | 4y (M) | c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys Maternally inherited (mother is Patient 16) | No seizures | Not done | Bilateral PMG | Pseudobulbar palsy; right hemiparesis; moderate DD |

| 16 | 37y (F) | c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys Maternally inherited | GTCS (5y) | NA | Bilateral PMG | Pseudobulbar palsy; brisk reflexes; mild ID |

| 17 | 14y (F) | c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys unknown inheritance | No seizures | Normal | Bilateral PMG | Oromotor dysfunction; normal strength and tone; mild ID |

| 18 | 36y (F) | c.4937T>C; p.Phe1646Ser de novo | Unknown (8d), FIAS, GTCS | Bitemporal epileptiform discharges | Bilateral PMG | Dysarthria, facial paresis, brisk reflexes; mild ID |

| 19 | 6y (M) | c.5006A>G; p.Tyr1669Cys de novo | No seizures | Not done | Not done | Mild DD; autism spectrum disorder |

| 2035 | 4y (M) | c.5295G>A; p.Met1765Ile de novo | T (1w), FM, ES | NA | Bilateral PMG | Generalized hypotonia; profound DD |

| 217 | NA (F) | c.5306T>C; p.Val1769Ala de novo | Onset <12m | Multifocal | NA | DD |

| 22 | 2y (F) | c.5306T>C; p.Val1769Ala de novo | T (4d), ES, FA | Hyps; GSW | Normal | Hypotonia with head lag; severe DD, autism |

Deceased, age at death; C, clonic seizures; CC, corpus callosum; d, days; DD: developmental delay; ES, epileptic spasms; FA, focal autonomic seizures; FIAS, focal impaired awareness seizures; FM, focal motor seizures; FMyo, focal myoclonic seizures; FS, febrile seizures; FT, focal tonic seizures; GPSW, generalized polyspike-wave discharges; GSSW, generalized slow spike-wave discharges; GSW, generalized spike-wave discharges; GTCS, generalized tonic-clonic seizures; hyps; hypsarrhythmia; HC, hemiclonic seizures; ID, intellectual disability; m, months; Myo, myoclonic seizures; NA: not available; PMG, polymicrogyria; SE, status epilepticus; SW, spike-and-slow wave complexes; T, generalized tonic seizures; w, weeks; y, years. Further clinical details are provided in Supplementary Tables 1-3

Figure 1. Schematic of the Nav1.3 protein.

Shown are all amino acid residues corresponding to disease-associated pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in SCN3A. Nav1.3 is formed by four repeated domains (DI-IV), each composed of six transmembrane segments (S1-6), with S1-4 of each domain mediating voltage sensing and S5-6 forming the ion conducting pore. Variants associated with malformation of cortical development are indicated with a purple circle, while variants identified in patients without malformation of cortical development are indicated with an orange circle. A blue circle denotes variants identified in patients where neuroimaging data was unavailable. Note that pathogenic variants appear to be preferentially clustered in S4-6 of DII-IV, with many variants at/near the intracellular S4-5 linker of DII-IV. MCD, malformation of cortical development. UTD, unable to determine (due to absence of available neuroimaging data).

Clinical characteristics

Of the 22 individuals with pathogenic or likely pathogenic SCN3A variants, 18 (82%) had epilepsy, with a median age of seizure onset of 2 weeks (range, 1 day to 5 years). One case was a 17-week gestation fetus with fetal akinesia sequence, for which clinical information is detailed separately below. Of the other 21 patients, most (16/21; 76%) had developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE), characterized by pharmaco-resistant seizures beginning in the first year of life, severe-to-profound developmental delay, and central hypotonia. Seizures began in the neonatal period in 11/18 patients (61%) for whom such data were available. The majority of patients developed pharmacoresistant epilepsy with multiple seizure types (Table 1). Tonic seizures were the most common presenting seizure type (7/16; 44%) followed by focal autonomic seizures (3/16; 19%). Four patients developed epileptic spasms. Two individuals had mild epilepsy beginning in later childhood characterized by infrequent generalized tonic-clonic seizures and not requiring treatment with anti-seizure medications. Four individuals had no seizures identified as of last follow up (at ages 4-14 years).

Information regarding developmental outcomes was available for 20 patients. Fifteen of 20 (75%) had severe to profound intellectual disability. Mild to moderate developmental delay/intellectual disability was observed in the other 5/20 (25%) individuals. Neurological examination revealed axial hypotonia in 10/20 (50%) individuals for whom this information was available, pseudobulbar palsy in 4/20 (20%), and peripheral spasticity in 6/20 (30%). Four affected individuals were noted to have hyperkinetic/dyskinetic movement disorders, characterized by dystonia, chorea, athetosis, and/or non-epileptic myoclonus.

Ictal and non-ictal autonomic dysfunction was a notable feature, identified in 9/20 (45%) patients. Autonomic changes included episodes of skin flushing involving one or both sides of the body (n = 8), intermittent excessive sweating (n = 4), anisocoria with sluggish pupillary response to light (n = 2), and episodes of bradycardia and oxygen desaturation (n = 3). These events were considered as autonomic seizures if they were the predominant clinical feature at onset of confirmed electrographic seizures.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed malformations of cortical development in 15/19 (79%) patients; brain imaging data were not available for the remaining three patients. Available brain MRI images showed dysgyria consistent with bilateral diffuse or perisylvian polymicrogyria in 14/19 (74%) patients (Fig 2). MRI of the brain of Patient 8 showed bifrontal cortical thickening and gyral simplification along with hypoplasia of the corpus callosum; dysgyria in Patient 8 was considered to be bifrontal pachygyria. Cortical thickening was seen in Patients 4 and 5 which was considered to represent diffuse PMG by the referring radiologists, versus dysgyria with PMG-like features. Findings consistent with partial lissencephaly was also mentioned in the formal radiology reports provided by referring providers for at least two patients (Patient 4, as well as Patient 14 for whom MRI images were not available for review). It should be noted that dysgyria can be difficult to evaluate via CT scan or on MRI scans performed in very young patients, and the entities of pachygyria versus polymicrogyria cannot be distinguished using radiology alone in some cases. Hypoplasia of the corpus callosum without cortical malformation was noted in two patients (2/19; 11%). Brain imaging was normal in two patients. Microcephaly was observed in 8/20 (40%) individuals for whom these data were available, including in patients who did (Patients 2, 4-6, 8, 11, and 16) and did not (Patient 22) have brain malformation. At least four of the 16 (25%) of the patients with DEE did not have malformations of cortical development (MRI was not available for review for Patient 21).

Figure 2. Magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brain of patients with SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder.

(A) MRI of the brain for Patient 4, showing (i) axial T2 and (ii) T2 FLAIR, illustrating cortical thickening and PMG-like features consistent with diffuse malformation of cortical development. (B) Patient 5, with (i) axial T2 and (ii) T1 sequences showing cortical thickening with diffuse PMG-like abnormalities, prominently in the bilateral frontal, perisylvian, and parietal regions. (C) Patient 8, showing (i) axial T2 and (ii) T2 FLAIR sequences demonstrating bifrontal cortical thickening and gyral simplification along with hypoplasia of the corpus callosum. (D) Patient 10, with (i) axial T2 and (ii) axial T2 FLAIR at age 2 months showing normal results. (E) MRI of the brain in Patient 12 at age 3 years including (i) axial T2 and (ii) T1 showing atrophy, predominantly of the bilateral frontal and temporal lobes, along with hypoplasia of the corpus callosum.

Familial polymicrogyria and inherited SCN3A variant

Patients 15 and 16 are part of a small family with autosomal dominant polymicrogyria. Trio-based whole exome sequencing identified the SCN3A c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys variant in both affected mother (Patient 16) and son (Patient 15). Both individuals had global developmental delays in childhood with ongoing mild intellectual disability, dysarthric speech, and pseudobulbar symptoms. Brain MRI in both patients revealed bilateral perisylvian polymicrogyria. Patient 15 did not have seizures at last follow up at age 4 years; Patient 16 (the mother of Patient 15) had onset of nocturnal generalized tonic-clonic seizures at age 5 years but was seizure free and off all anti-seizure medication at age 37 years. Parental testing of Patient 16 revealed that the SCN3A variant was inherited from her own mother (i.e., the maternal grandmother of Patient 15); the grandmother had normal intellectual functioning and was not reported to have any neurological issues, although neuroimaging had not been obtained. The SCN3A c.4937T>G; p.Phe1646Cys variant was present in 97/195 next generation sequencing reads in analysis performed on a sample of peripheral blood leukocytes obtained from the mother of Patient 16, indicating that the mother of Patient 16 is heterozygous with no suggestion of mosaicism in DNA.

17-week gestation fetus with de novo SCN3A variant

A de novo SCN3A c.2564T>C; p.(Leu855Pro) variant was identified in a 17-week gestation female fetus with fetal akinesia sequence. At 16 weeks gestation, cystic hygroma colli and retrognathia were noted on ultrasound examination, and the pregnancy was terminated at 17 weeks 3 days with identification of severe arthrogryposis multiplex. Fetal autopsy confirmed fetal akinesia sequence with flexion of the elbows, shoulders with pterygium, hands and fingers, knees, ankles, and hips. Dysmorphic features were noted, including small, low-set and posteriorly rotated ears, flat columella, and anteverted nares, with small mouth, thin lips, microglossia, and posterior cleft palate. Fetal MRI was not performed, but neuropathological examination of the brain revealed a smooth agyric brain, considered normal for gestational age, with dilated ventricles with germinolytic cysts along the fourth ventricle and calcifications in the corticospinal bundles. Lamination of the neocortex in the frontal and perisylvian regions was normal. Pulmonary and thymus hypoplasia as well as intestinal malrotation were noted. Additional genetic testing performed in this case included a normal chromosomal microarray, negative DMPK sequencing, and negative neuromuscular NGS panel. Both parents were found to have normal standard karyotypes and two copies of SMN1.

Variant of uncertain significance

One individual in our cohort had an SCN3A variant of uncertain significance (VUS; Supplementary Table 1). The p.Val1280Ile variant identified in Patient 23 was inherited from the patient’s mother who has a history of epilepsy. This variant is observed in three heterozygous individuals in gnomAD and was therefore considered to be a VUS.

Electrophysiological characterization of channels containing variant Nav1.3 subunits

To further investigate the mechanisms whereby pathogenic variants in SCN3A might lead to epilepsy and/or brain malformation, we generated disease-associated Nav1.3 variants and expressed these variants in a heterologous mammalian cell line for characterization via whole-cell voltage clamp recording. We recorded wild-type or variant Nav1.3 co-expressed with wild-type β1 and β2 in HEK-293T cells, including twelve different pathogenic variants and one variant of uncertain significance. All recordings and post-hoc data analysis were performed blind to genotype. We identified profound abnormalities in Na+ currents in all of the tested pathogenic variants as compared to wild-type control (see below). Properties of the variant of uncertain significance, Nav1.3-p.Val1280Ile, were identical to wild-type.

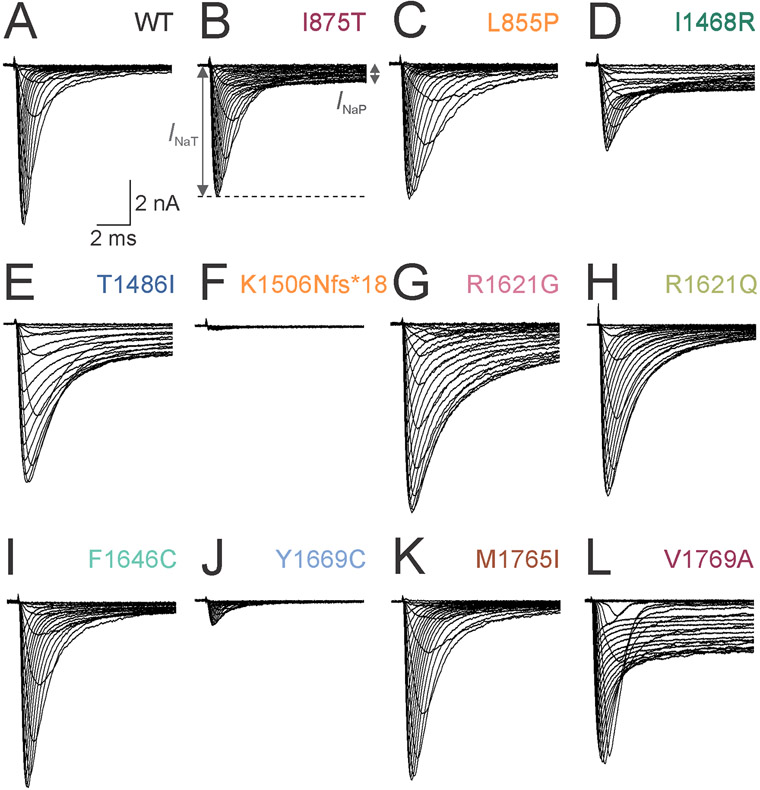

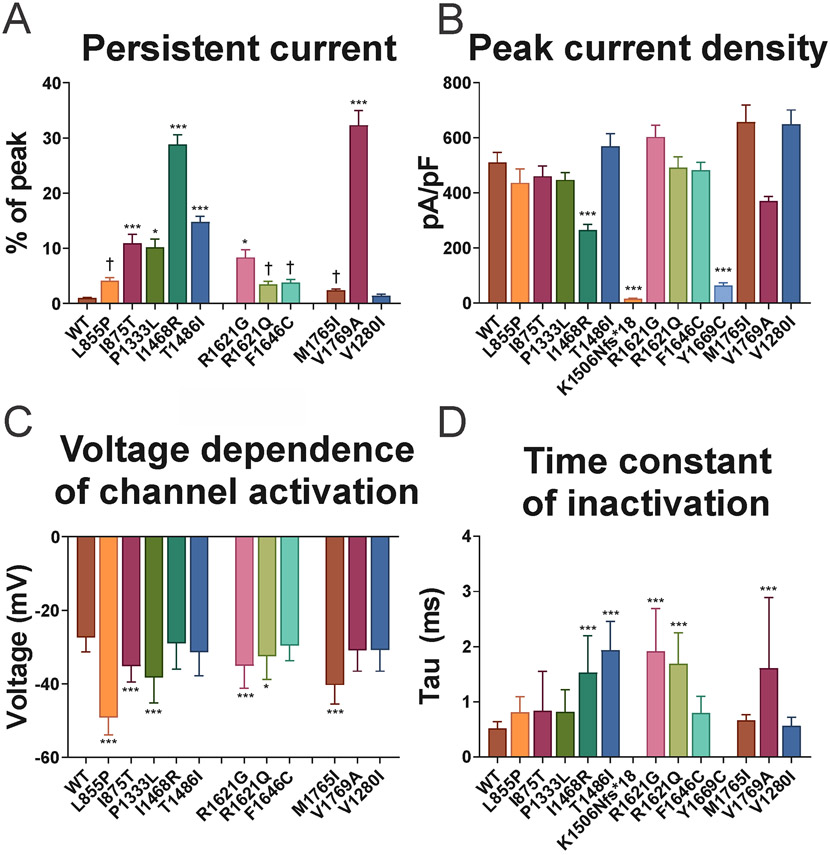

Peak current density was 511 ± 35 pA/pF in Na+ channels containing wild-type Nav1.3 (n = 42; Table 2; Fig 3 and 4). We found significant decreases in current density for three variants, Nav1.3-p.Ile1468Arg (265 ± 20 pA/pF; mean ± standard deviation; n = 25; p < 0.0001 vs. wild-type via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons), Nav1.3-p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 (15 ± 2 pA/pF; n =24; p < 0.0001), and Nav1.3-Tyr1669Cys (64 ± 11 pA/pF; n = 20; p < 0.0001). The peak current density associated with the remaining variants was not significantly different from wild-type or from one another. None of the individuals with brain malformation harbored variants that formed Na+ channels that exhibited decreased current density.

Table 2.

Biophysical properties of wild-type and variant Nav1.3 channels.

| Peak current density |

Voltage dependence of channel activation |

Voltage dependence of inactivation |

Persistent current |

Inactivation tau |

n | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pA/pF | V 1/2 | k | V 1/2 | k | % of peak | ms | ||

| Wild-type | 511 ± 35 | −27.4 ± 0.8 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | −66.2 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 42 |

| L855P | 436 ± 51 | −49.1 ± 1.0*** | 5.7 ± 0.3 | −71.9 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.6† | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 21 |

| I875T | 460 ± 38 | −35.1 ± 0.9*** | 4.9 ± 0.3 | −63.9 ± 1.6 | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 10.9 ± 1.6*** | 0.83 ± 0.14 | 25 |

| P1333L | 447 ± 27 | −38.3 ± 2.0*** | 4.9 ± 0.5 | −66.0 ± 8.2 | 10.6 ± 1.4 | 10.2 ± 1.5* | 0.82 ± 0.12 | 15 |

| I1468R | 265 ± 20*** | −29.0 ± 1.4 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | −41.2 ± 1.8*** | 16.0 ± 0.9 | 28.8 ± 1.8*** | 1.53 ± 0.13*** | 25 |

| T1486I | 569 ± 47 | −31.2 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | −56.5 ± 2.2*** | 7.8 ± 0.5 | 14.8 ± 1.0*** | 1.93 ± 0.09*** | 36 |

| K1506Nfs*18 | 15 ± 2*** | 24 | ||||||

| R1621G | 603 ± 43 | −35.0 ± 1.0*** | 3.9 ± 0.2 | −66.2 ± 2.2 | 11.4 ± 0.4 | 8.3 ± 1.4* | 1.92 ± 0.13*** | 37 |

| R1621Q | 491 ± 41 | −32.5 ± 1.2* | 4.6 ± 0.2 | −64.9 ± 1.3 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.6† | 1.69 ± 0.10*** | 31 |

| F1646C | 482 ± 29 | −29.6 ± 0.7 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | −54.6 ± 0.9*** | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 3.8 ± 0.5† | 0.80 ± 0.05 | 39 |

| Y1669C | 64 ± 11*** | 20 | ||||||

| M1765I | 657 ± 62 | −40.3± 1.0*** | 4.2 ± 0.3 | −71.7 ± 1.3 | 8.3 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.3† | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 24 |

| V1769A | 363 ± 18 | −30.1 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | −51.4 ± 3.4*** | 16.6 ± 1.8 | 32.3 ± 2.6*** | 1.39 ± 0.11*** | 27 |

| V1280I | 649 ± 53 | −31.6 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | −70.5 ± 0.9 | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 25 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001; via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni test

p < 0.0001 via unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test; not significant via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc correction

Figure 3. Voltage clamp recordings of ionic currents from Na+ channels containing wild-type versus variant Nav1.3 subunits.

(A) Representative set of single leak-subtracted Na+ currents recorded from HEK-293T cells co-transfected with wild-type (WT) Nav1.3 subunits along with β1 and β2 in response to ascending currents steps from a holding potential of −120 mV to from −80 to +40 mV in 5 mV steps. Note the fast, transient inward current with minimal slowly-inactivating (“persistent”) component. (B) Na+ current mediated by Nav1.3-Ile875Thr (I875T) subunit-containing Na+ channels. INaT, transient current component; INaP, persistent component. (C) Nav1-3-p.Leu855Pro (L855P). (D) Nav1.3-p.Ile1468Arg (I1468R). Note lower INaT, impaired fast inactivation and prominent INaP relative to wild-type. (E) Nav1.3-p.Thr1486Ile (T1486I). (F) Nav1.3-p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 (K1506Nfs*18). Note absent INaT. (G) Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gly (R1621G). (H) Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gln (R1621Q). (I) Nav1.3-p.Phe1646Cys (F1646C). (J) Nav1.3-p.Tyr1669Cys (Y1669C). (K) Nav1.3-p.Met1765Ile (M1765I). (L) Nav1.3-p.Val1769Ala (V1769A). Scale bars in (A) apply to (A-L).

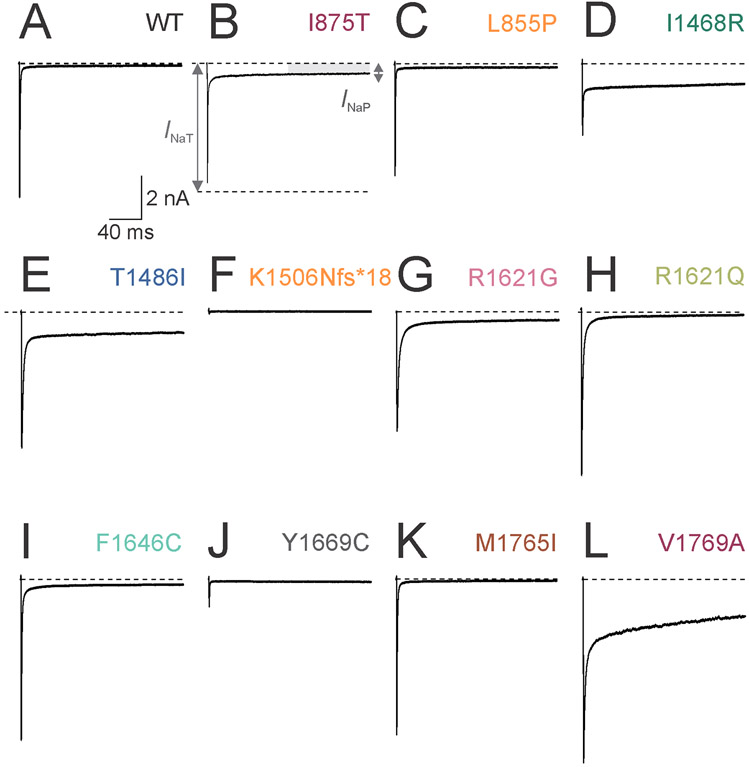

Figure 4. Increased slowly-inactivating current in Na+ channels formed by disease-associated variant Nav1.3 subunits.

(A) Representative single leak-subtracted Na+ currents recorded from channels containing wild-type (WT) Nav1.3 subunits along with β1 and β2 in response to a voltage step from −120 to −10 mV. Note the fast, transient inward current with minimal slowly-inactivating (“persistent”) component. (B) Na+ current mediated by Nav1.3-p.Ile875Thr (I875T) subunit containing Na+ channels. INaT (dashed line), transient current component; INaP (gray bar), persistent component.

(C) Nav-1.3.p.Leu855Pro (L855P). (D) Nav1.3-p.Ile1468Arg (I1468R). (E) Nav1.3-p.Thr1486Ile (T1486I). (F) Nav1.3-p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 (K1506Nfs*18). (G) Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gly (R1621G). (H) Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gln (R1621Q). (I) Nav1.3-p.Phe1646Cys (F1646C). (J) Nav1.3-p.Tyr1669Cys (Y1669C). (K) Nav1.3-p.Met1765Ile (M1765I). Scale bars in (L) apply to (A-L). Dashed lines indicate zero current level for clarity.

Previous recordings of Na+ channels composed of Nav1.3 variants associated with epileptic encephalopathy and/or PMG showed prominent gain of channel function with an increase in the slowly-inactivating current component (“persistent” current; INaP) and/or a left/hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation. Consistent with previous results, we found that Na+ channels containing wild-type Nav1.3 exhibited low levels of INaP (1.0 ± 0.1%; Table 2; Fig 3 and 4). Ten out of 11 (91%) pathogenic missense variants exhibited increased INaP vs. wild-type, ranging from 2.3 ± 0.3% (Nav1.3-p.Met1765Ile) to 32.3 ± 2.6% (Nav1.3-p.Val1769Ala).

Recordings also demonstrated a leftward/hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation for many of the variants (Nav1.3-p.Leu855Pro, Nav1.3-p.Ile875Thr, Nav1.3-p.Pro1333Lys, Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gly, Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Glu, and Nav1.3-p.Met1765Ile) relative to wild-type (V1/2 of −27.4 ± 0.8; n = 29; Table 2; Fig 5). Interestingly, a large leftward shift was seen for Na+ channels formed by Nav1.3-p.Met1765Ile variant subunits (V1/2 of −40.3 ± 1.0; n = 24; p < 0.0001 vs. wild-type via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons), despite the fact that there was only a small increase in INaP relative to wild-type for this variant (2.3 ± 0.3%; n = 24; p > 0.05 via one-way ANOVA; p < 0.0001 vs. wild-type via unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test).

Figure 5. Biophysical properties of Na+ channels containing wild-type and variant Nav1.3 subunits.

(A) Slowly-inactivating (“persistent”) Na+ current quantified as a percentage of peak transient current during a voltage step from −120 to −10 mV. (B) Peak inward transient Na+ current recorded with current steps from −120 to +40 mV in 5 mV increments. (C) Voltage dependence of channel activation defined as the V1/2 of the Boltzman fit to the relationship of normalized conductance and voltage. (D) Time constant (τ) of fast inactivation, calculated for a voltage step from −120 to −10 mV. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; via one-way ANOVA with post-hoc correction for multiple comparisons with Bonferroni test. † p < 0.05 via one-way ANOVA without post-hoc correction.

Finally, multiple disease-associated variants exhibited prolongation of the time constant of fast inactivation (Table 2; Fig 5).

These data show that Na+ channels containing Nav1.3 subunits corresponding to pathogenic variants in SCN3A largely exhibit gain of channel function, with an increase in the slowly inactivating (“persistent”) current component, a leftward/hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation, and/or a prolongation in the time constant of fast channel inactivation.

Discussion

We report clinical and genetic data on a cohort of patients found to have pathogenic variants in SCN3A encoding the type III voltage-gated Na+ channel α subunit and include a detailed characterization of the biophysical properties of Na+ channels composed of the corresponding variant Nav1.3 subunits.

SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder: A phenotypic spectrum

SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder falls along a phenotypic spectrum atypical of other epilepsy-associated channelopathies and includes developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE) with, or less often without, malformation of cortical development, mild focal epilepsy with malformation of cortical development, and isolated cortical malformation without epilepsy. Some degree of cognitive impairment is seen in all affected individuals, but is usually severe to profound. Notable features of SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder that may distinguish it from other genetic DEEs include neonatal onset treatment-resistant epilepsy, malformation of cortical development, and autonomic disturbances. Malformations of cortical development have been found in patients with epilepsy and de novo pathogenic variants in other ion channel genes, including SCN1A, SCN2A, GRIN1, and GRIN2B.35-38 However, while brain malformation in association with other channelopathies appears to be an atypical or relatively uncommon finding, malformations of cortical development are a characteristic feature of SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder, seen in over 75% of affected individuals.

SCN3A as a disease gene

The disease-gene relationship between DEE/MCD and pathogenic variants in SCN3A is supported by multiple convergent lines of evidence. Pathogenic variants were either observed to be de novo or inherited from an affected parent. Identified variants occurred at residues that are highly conserved between paralogous Na+ channel genes and across phylogeny, were not observed in any heterozygous individuals in databases of normal human genetic variation including gnomAD, and were predicted to be pathogenic by in silico algorithms. In addition, electrophysiological studies of Na+ channels composed of variant Nav1.3 subunits in heterologous systems demonstrated biophysical abnormalities relative to both wild-type and inherited variants of uncertain significance identified in individuals with milder forms of epilepsy without brain malformations. Evidence that pathogenic variants in SCN3A can cause malformations of cortical development include the fact that SCN3A is known to be expressed at high levels in the developing human brain13 including in radial glial and intermediate progenitor cells and in developing neurons of the cortical plate.22,39 Such variants assort with the presence of brain malformation in familial cases in this and prior reports.11,21,22 Additionally, overexpression of variant SCN3A in developing ferret neocortex also produces focal cerebral cortical malformation.22

Genotype-phenotype correlations

All reported patients with the recurrent c.2624T>C; p.Ile875Thr variant (with now eight cases reported in the literature) have a seemingly homogeneous phenotype, consisting of diffuse cortical malformations, neonatal onset intractable epilepsy presenting with generalized tonic seizures, significant central hypotonia with appendicular spasticity, and severe to profound neurocognitive impairment.11,21,40 Na+ channels containing Nav1.3-p.Ile875Thr variant subunits exhibit profound abnormalities with a gain of channel function including a leftward/hyperpolarized shift in the voltage dependence of channel activation and increased persistent current.

Na+ channels containing variant Nav1.3 subunits corresponding to patients with either DEE and/or PMG exhibited various types of biophysical abnormalities. Most disease-associated variants exhibited normal current density, which suggests normal trafficking to the cell surface in these cases. While we found that variants in patients with DEE formed Na+ channels that largely exhibited gain of channel function (Patients 2-7, 9-11, 13, 20-22), we did observe one patient with DEE (Patient 12) with a variant that formed channels exhibiting loss of channel function and another patient with DEE (Patient 10) with a variant that formed channels with a mixed gain/loss of channel function. For the Nav1.3-p.Ile1468Arg variant identified in Patient 10, the relative contribution of the gain (slowing of fast inactivation, increased persistent current) versus loss (decreased current density) to the pathogenicity of this variant is unclear.

We found that the Na+ currents recorded from channels formed by variant Nav1.3 subunits corresponding to patients with PMG uniformly exhibited gain of channel function, although in a subset of patients – Patient 13 (Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gly), Patient 14 (Nav1.3-p.Arg1621Gln), and Patients 15-17 (Nav1.3-p.Phe1646Cys) – this was quite modest. None of the PMG-associated variants had an effect on Na+ current density.

Of the 16 patients with variants resulting in gain of channel function, 13 (81%) had cortical malformations, 12 (75%) had DEE, and 9 (56%) had both cortical malformation and DEE. Why pathogenic variants in SCN3A exhibiting gain of function at the ion channel level are associated with malformation of cortical development in many (but not all) cases remains unclear. It may be that the subset of patients without malformation of cortical development (Fig 2, Fig 6) have more subtle migrational defects that are not visible on MRI yet might be apparent at the histological level.

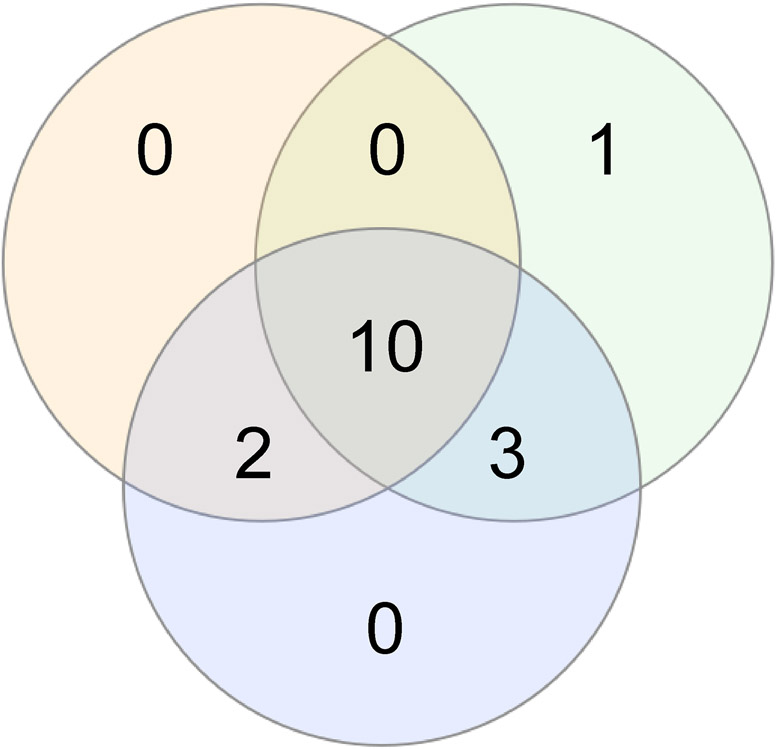

Figure 6. Overlap between epilepsy, malformation of cerebral cortical development, and electrophysiological gain of function at the ion channel level.

Shown is a schematic illustrating the overlap between key features of SCN3A neurodevelopmental disorders in all patients for whom neuroimaging results, detailed clinical information, and electrophysiological data was available (n = 17), including presence of seizure(s)/epilepsy (green), malformation of cerebral cortical development (orange), and electrophysiological data in heterologous expression systems indicating gain of ion channel function for a given disease-associated Nav1.3 variant relative to wild-type (blue). Electrophysiological data was not obtained for the variants identified in Patient 8 (Nav1.3-p.Leu885Phe) or 17 (Nav1.3-p.Phe1646Ser) and hence these patients were not included in the Figure. Note that all patients with MCD harbored variants exhibiting GOF (13/13; 100%). Many patients for whom complete data was available shared all three features (11/17; 65%), 9 of 11 (82%) of whom had DEE. However, three patients with DEE and pathogenic GOF variants in SCN3A for whom neuroimaging was available did not have MCD. GOF, gain of channel function; MCD, malformation of cortical development; DEE, developmental and epileptic encephalopathy.

Insights into mechanisms of slow inactivation of Na+ channels

We find that all of the 13 identified pathogenic missense variants are located in S4–6 of domains II-IV of Nav1.3 (Fig 1). Such clustering of pathogenic variants is striking, as this is not clearly the case for other epilepsy-associated ion channelopathies that feature gain-of-function variants, such as SCN2A and SCN8A encephalopathy.5,6,41 Many of the variants (8/13; 62%) are located in S4 or in or close to the S4-S5 linker of domains II-IV, in close proximity to the positively charged arginine residues of the S4 helix domain of the Na+ channel voltage sensor. The abnormalities in gating and fast and slow inactivation observed here are consistent with data indicating that opening of the channel pore occurs via translation of voltage-dependence shifts from the S4-S5 linker to the S4 segment,42 with motion of S4-S5 in turn coupled to the neighboring S5 and S6 segments.43

Loss-of-function variants

The role of loss of function variants in SCN3A as a cause of disease remains less clear. The clinical presentations of the two patients in our cohort with variants exhibiting loss of function properties in the experimental system employed here were vastly different, with one patient (Patient 12) presenting at 2 months with DEE and profound neurodevelopmental disability (albeit without malformation of cortical development) and the other (Patient 19) exhibiting mild intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorder with no history of seizures or epilepsy. Both de novo variants identified in these patients (Nav1.3-p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 in Patient 12; Nav1.3-p.Tyr1669Cys in Patient 19) were classified as likely pathogenic and formed Na+ channels that demonstrated markedly reduced current density relative to wild-type subunits.

Heterologous expression of the Nav1.3-p.Lys1506Asnfs*18 variant identified in Patient 12 was found to produce Na+ channels with no inward current, suggesting loss of channel function. However, the affected amino acid residue is localized to the distal end of exon 26 and it is possible that there could be escape from nonsense-mediated decay to allow production of an abnormal, truncated protein in vivo that might act via another (potentially gain of function) mechanism. This possibility remains hypothetical.

The Scn3a null mouse has a mild or no neurological phenotype and does not have spontaneous seizures.17,44 However, a previous report described a patient with focal epilepsy and moderate to severe intellectual disability was found to harbor a de novo missense variant (Nav1.3-p.Lys247Pro) that exhibited in loss of function due to impaired trafficking to the cell surface.17 Although several variants that result in premature termination codons (including frameshift, nonsense, and splice site variants) are reported in gnomAD in purportedly normal individuals with no history of neurodevelopmental disorder, SCN3A is depleted of loss of function variants oveall in gnomAD (pLI = 1), suggesting that loss-of-function is not tolerated in unaffected individuals.

Hence, the overall conclusion that SCN3A haploinsufficiency may be tolerated in unaffected individuals is difficult to rationalize with the profound phenotype observed in Patient 12. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanism by which SCN3A loss of function might lead to neurodevelopmental disorder.

Towards targeted therapy

Data in a heterologous expression system demonstrate that certain pathological features of Na+ channels containing epilepsy-associated Nav1.3 variants could be partially normalized by pharmacological agents that preferentially block persistent Na+ current. However, other biophysical properties, such as the voltage dependence of channel gating and the kinetics of fast inactivation, are not affected by such agents, a result similar to what has been shown previously for SCN8A epilepsy.45 Of the 15 patients with pathogenic variants in SCN3A included in the present study for whom detailed information regarding anti-seizure drug therapy was available, at least six were trialed on one or more agents with a prominent mechanism of action of Na+ channel blockade. Yet, such therapy was ineffective in all patients. It is possible that earlier initiation of therapy, use of higher or very high doses, and/or use of novel experimental agents with greater selectivity for Nav1.3-containing Na+ channels and/or persistent over transient Na+ current might be more efficacious. However, for the majority of patients, it is difficult to disentangle whether the cause of epilepsy might be the Na+ channel abnormality itself, the brain malformation, or both, and anti-seizure medications cannot reverse malformation of cortical development.

Limitations

All experiments were performed using transient transfection of wild-type or variant Nav1.3 α subunits along with β1 and β2 subunits, which leads to variable and unknown relative expression between cells that can strongly influence the biophysical properties of Na+ channels, including surface expression, channel gating, and INaP.10,46,47

We used a cDNA encoding isoform 2, which is considered to be the major splice variant. No major differences have been identified in the biophysical properties of Na+ channels containing Nav1.3 subunits encoded by the various SCN3A isoforms,48 although we did investigate the effect of the identified pathogenic variants on the function of these other isoforms.

Finally, while we ascertained patients from many institutions across multiple continents via a network of collaborators and consortia, our cohort may remain biased towards and over represent patients with more severe neurodevelopmental syndromes and with epilepsy as a prominent component of the clinical presentation. More severe cases may be more likely to present to medical attention and be referred for genetic testing, whereas more mildly affected individuals, including those that may be asymptomatic, may never present to medical attention.

A spectrum of disease features

In conclusion, we present a comprehensive description of 22 patients with pathogenic variants in the voltage-gated Na+ channel gene SCN3A along with an electrophysiological characterization of Na+ channels formed by variant Nav1.3 subunits. We establish malformation of cortical development as a key feature and suggest the term SCN3A-related neurodevelopmental disorder to describe what is generally a severe syndrome that includes the as-yet unexplained overlap of epilepsy and/or malformation of cortical development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Xiaohong Zhang for expert technical assistance. We thank Lori L. Isom for the gift of a β-1 cDNA clone and Alfred L. George for the gift of a β-2 cDNA clone. The DDD study presents independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (grant number HICF-1009-003), a parallel funding partnership between the Wellcome Trust, the Department of Health, and the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (grant number WT098051). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Wellcome Trust or the Department of Health. This work was supported by NIH NINDS K08 NS097633, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists, and a March of Dimes Basil O’Connor Research Award to EMG; and AMED under the grant numbers JP19ek0109280, JP19dm0107090, JP19ek0109301, JP19ek0109348, JP18kk020501, and JSPS KAKENHI under the grant numbers JP17K10080 to SM. KS, AJ, EP, BBZ, DTP, AEF are members of the European Network on Brain Malformations Neuro-MIG COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Action 16118. DTP and AEF were supported by the Newlife Foundation for Disabled Children (Grant Reference: 11-12/04), Wales Epilepsy Research Network, and Wales Gene Park.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron 2000;26(1):13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J. Physiol 2012;590(11):2577–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pappalardo LW, Black JA, Waxman SG. Sodium channels in astroglia and microglia. Glia 2016;64(10):1628–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claes L, Del-Favero J, Ceulemans B, et al. De novo mutations in the sodium-channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2001;68(6):1327–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolff M, Johannesen KM, Hedrich UBS, et al. Genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity suggest therapeutic implications in SCN2A-related disorders Brain 2017;140(5):1316–1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen J, Carvill GL, Gardella E, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of SCN8A encephalopathy. Neurology 2015;84(5):480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugawara T, Mazaki-Miyazaki E, Ito M, et al. Nav1.1 mutations cause febrile seizures associated with afebrile partial seizures. Neurology 2001;57(4):703–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veeramah KR, O’Brien JE, Meisler MH, et al. De Novo Pathogenic SCN8A Mutation Identified by Whole-Genome Sequencing of a Family Quartet Affected by Infantile Epileptic Encephalopathy and SUDEP. Am. J. Hum. Genet 2012;90(3):502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wallace RH, Wang DW, Singh R, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat. Genet 1998;19(4):366–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Malley HA, Isom LL. Sodium Channel β Subunits: Emerging Targets in Channelopathies. Annu. Rev. Physiol 2015;77(1):481–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaman T, Helbig I, Božović IB, et al. Mutations in SCN3A cause early infantile epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol 2018;83(4):703–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheah CS, Westenbroek RE, Roden WH, et al. Correlations in timing of sodium channel expression, epilepsy, and sudden death in Dravet syndrome. Channels 2013;7(6):468–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitaker WR, Clare JJ, Powell AJ, et al. Distribution of voltage-gated sodium channel alpha-subunit and beta-subunit mRNAs in human hippocampal formation, cortex, and cerebellum. J. Comp. Neurol 2000;422(1):123–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckh S, Noda M, Lübbert H, Numa S. Differential regulation of three sodium channel messenger RNAs in the rat central nervous system during development. EMBO J. 1989;8(12):3611–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felts PA, Yokoyama S, Dib-Hajj S, et al. Sodium channel alpha-subunit mRNAs I, II, III, NaG, Na6 and hNE (PN1): different expression patterns in developing rat nervous system. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res 1997;45(1):71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holland KD, Kearney JA, Glauser TA, et al. Mutation of sodium channel SCN3A in a patient with cryptogenic pediatric partial epilepsy. 2008;433:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamar T, Vanoye CG, Calhoun J, et al. SCN3A deficiency associated with increased seizure susceptibility Neurobiol. Dis 2017;102:38–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Du X, Bin R, et al. Genetic Variants Identified from Epilepsy of Unknown Etiology in Chinese Children by Targeted Exome Sequencing. Sci. Rep 2017;7:40319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Estacion M, Gasser A, Dib-hajj SD, Waxman SG. A sodium channel mutation linked to epilepsy increases ramp and persistent current of Nav1 . 3 and induces hyperexcitability in hippocampal neurons. Exp. Neurol 2010;224(2):362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanoye CG, Gurnett CA, Holland KD, et al. Neurobiology of Disease Novel SCN3A variants associated with focal epilepsy in children. Neurobiol. Dis 2014;62:313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyatake S, Kato M, Sawaishi Y, et al. Recurrent SCN3A p.Ile875Thr variant in patients with polymicrogyria. Ann. Neurol 2018;84(1):159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith RS, Kenny CJ, Ganesh V, et al. Sodium Channel SCN3A (NaV1.3) Regulation of Human Cerebral Cortical Folding and Oral Motor Development. Neuron 2018;99(5):905–913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inuzuka LM, Macedo-Souza LI, Della-Ripa B, et al. Neurodevelopmental disorder associated with de novo SCN3A pathogenic variants: two new cases and review of the literature. Brain Dev. 2020;42(2):211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study. Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature 2017;542(7642):433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farwell KD, Shahmirzadi L, El-Khechen D, et al. Enhanced utility of family-centered diagnostic exome sequencing with inheritance model-based analysis: results from 500 unselected families with undiagnosed genetic conditions. Genet. Med 2015;17(7):578–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retterer K, Juusola J, Cho MT, et al. Clinical application of whole-exome sequencing across clinical indications. Genet. Med 2016;18(7):696–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson KM, Nesbitt A, Cao K, et al. Novel findings with reassessment of exome data: implications for validation testing and interpretation of genomic data. Genet. Med 2018;20(3):329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrovski S, Aggarwal V, Giordano JL, et al. Whole-exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):758–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoi H, Mizuguchi T, Ceroni JR, et al. Comprehensive genetic analysis of 57 families with clinically suspected Cornelia de Lange syndrome. J. Hum. Genet 2019;64(10):967–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med 2015;17(5):405–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536(7616):285–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCormack K, Santos S, Chapman ML, et al. Voltage sensor interaction site for selective small molecule inhibitors of voltage-gated sodium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013;110(29):E2724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Platzer K, Yuan H, Schütz H, et al. GRIN2B encephalopathy: novel findings on phenotype, variant clustering, functional consequences and treatment aspects. J. Med. Genet 2017;54(7):460–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlachou V, Larsen L, Pavlidou E, et al. SCN2A mutation in an infant with Ohtahara syndrome and neuroimaging findings: expanding the phenotype of neuronal migration disorders. J. Genet 2019;98(2). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fry AE, Fawcett KA, Zelnik N, et al. De novo mutations in GRIN1 cause extensive bilateral polymicrogyria. Brain 2018;141(3):698–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barba C, Parrini E, Coras R, et al. Co-occurring malformations of cortical development and SCN1A gene mutations. Epilepsia 2014;55(7):1009–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollen AA, Nowakowski TJ, Chen J, et al. Molecular identity of human outer radial glia during cortical development. Cell 2015;163(1):55–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldberg EM, Helbig I. Reply to “Recurrent SCN3A p.Ile875Thr variant in patients with polymicrogyria”. Ann. Neurol 2018;84(1):161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wagnon JL, Meisler MH. Recurrent and Non-Recurrent Mutations of SCN8A in Epileptic Encephalopathy Front. Neurol. 2015;6:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long SB, Campbell EB, Mackinnon R. Voltage Sensor of Kv1.2: Structural Basis of Electromechanical Coupling. Science. 2005;309(5736):903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen H, Zhou Q, Pan X, et al. Structure of a eukaryotic voltage-gated sodium channel at near-atomic resolution. Science. 2017;355(6328):eaal4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nassar MA, Baker MD, Levato A, et al. Nerve Injury Induces Robust Allodynia and Ectopic Discharges in Na v 1.3 Null Mutant Mice. Mol. Pain 2006;2:1744-8069-2–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaman T, Abou Tayoun A, Goldberg EM. A single-center SCN8A-related epilepsy cohort: clinical, genetic, and physiologic characterization. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol 2019;6(8):1445–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aman TK, Grieco-Calub TM, Chen C, et al. Regulation of persistent Na current by interactions between beta subunits of voltage-gated Na channels. J. Neurosci 2009;29(7):2027–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu Y, Curtis R, Lawson D, et al. Differential modulation of sodium channel gating and persistent sodium currents by the beta1, beta2, and beta3 subunits. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 2001;18(5):570–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thimmapaya R, Neelands T, Niforatos W, et al. Distribution and functional characterization of human Na v 1.3 splice variants. Eur. J. Neurosci 2005;22(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.