Abstract

Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum (HMSN/ACC) is a rare autosomal recessive condition characterised by early-onset severe progressive neuropathy, variable degrees of ACC and cognitive impairment. Mutations in SLC12A6 (solute carrier family 12, member 6) encoding the K+–Cl- transporter KCC3 have been identified as the genetic cause of HMSN/ACC. We describe fraternal twins with compound heterozygous mutations in SLC12A6 and much milder phenotype than usually described. Neither of our patients requires assistance to walk. The female twin is still running and has a normal intellect. Charcot-Marie-Tooth Examination Score 2 was 8/28 in the brother and 5/28 in the sister. Neurophysiology demonstrated a length-dependent sensorimotor neuropathy. MRI brain showed normal corpus callosum. Genetic analysis revealed compound heterozygous mutations in SLC12A6, including a whole gene deletion. These cases expand the clinical and genetic phenotype of this rare condition and highlight the importance of careful clinical phenotyping.

Keywords: clinical neurophysiology, neuro genetics, peripheral nerve disease

Background

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease or hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy (HMSN) is the most frequent inherited neuromuscular disorder.1 SLC12A6 (solute carrier family 12, member 6) encodes the K+–Cl-transporter KCC3 and pathogenic variants in this gene are associated with HMSN with variable degrees of agenesis of the corpus callosum in most cases (HMSN/ACC).2 This is an autosomal recessive condition with onset in infancy, characterised by severe progressive sensorimotor neuropathy and cognitive impairment. The K+/Cl−cotransporter family are crucial in ion homeostasis, cell volume regulation and modulation of the cellular responses to GABA during neuronal development. HMSN/ACC was first described in Quebec2 with fewer reports among populations outside French-Canada.

Case presentation

27-year old fraternal twins had normal developmental milestones and walked by 15 months. There is no history of consanguinity.

The male twin, patient 1, started to trip at 5 years. He played sports in primary school but was always last in races. He has been unable to run since his teens and has worn orthotics since 21, having foot surgery at 26. He had difficulty holding a pen, writing, closing buttons and opening jars but no sensory symptoms. He required special educational needs assistance throughout school and a scribe for final exams due to his difficulty with handwriting; however, he remained in mainstream school and subsequently completed third-level education in an institute of technology. On examination, he had marked bilateral foot drop and walked with a broad base and waddle. He was unable to stand on his heels. He had a high arched palate and a convergent strabismus. He had scoliosis with winging of the left scapula and wasting from mid-forearms and knees distally with pes cavus and hammer toes bilaterally. He had length-dependent weakness predominantly affecting the intrinsic hand muscles, ankle dorsiflexion and eversion. He was areflexic throughout. Pinprick sensation was normal. Vibration was reduced to costal margin bilaterally. Joint position sense and temperature were normal. CMT examination score 2 (CMTES2) was 8/28 which is in the mild–moderate range.3

The female twin, patient 2, is less severely affected. She had difficulty in fitting shoes in the first decade and always had difficulty opening jars. She had foot surgery in the teens. She has worn orthotics since 20 years. She did not require any additional help in school and finished university. On examination, she had bilateral foot drop. She had a high arched palate and pes cavus bilaterally. She had mild weakness in the intrinsic hand muscles to MRC grade 4 and mild weakness of ankle dorsiflexion. She was areflexic throughout. Plantars were flexor. Pin and joint position sensation were normal. Vibration was reduced to costal margin bilaterally. CMTES2 score was 5/28 indicating mild severity.

Investigations

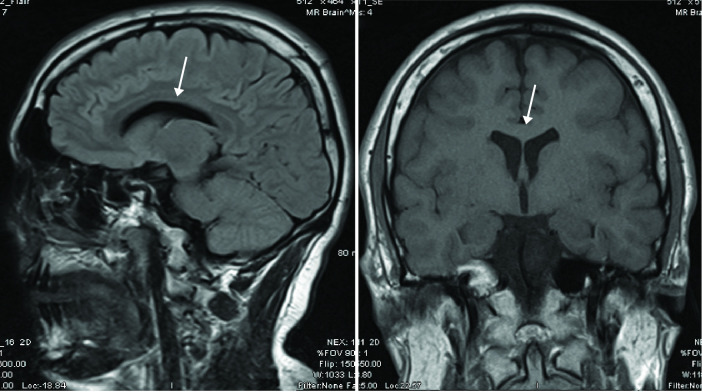

MRI brain showed normal corpus callosum without significant atrophy (figure 1). Neurophysiology demonstrated a length-dependent, sensorimotor axonal neuropathy with some evidence of dispersion and conduction block (table 1).

Figure 1.

MRI brain of patient 1. MRI brain with intact corpus callosum.

Table 1.

Nerve conduction studies of fraternal twins with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy due to compound heterozygous mutations in SLC12A6

| Motor | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | ||||

| Lat (ms) | Amp (mV) | CV (m/s) | Lat (ms) | Amp (mV) | CV (m/s) | |

| Median-right | ||||||

| Wrist-abductor pollicis brevis | 5.55 (≤4.0) | 1.93 (≥5.0) | 2.96 | 4.6 | ||

| Elbow-wrist | 11.3 | 1.64 | 43 (≥50) | 7.59 | 4.0 | 47.5 |

| Ulnar-right | ||||||

| Wrist-abductor digiti minimi | 2.32 (≤3.5) | 6.0 (≥7.0) | 2.83 | 5.6 | ||

| Below elbow-wrist | 7.12 | 4.9 | 51 (≥50) | 6.97 | 3.9 | 50.7 |

| Peroneal-left | ||||||

| Ankle-extensor digitorum brevis | 19.9 (≤6.0) | (≥2.5) | (≥40) | 4.46 | 1.84 | |

| Below knee-ankle | 12.7 | 0.53 | 37.5 | |||

| Tibial-left | ||||||

| Ankle-abductor halluces | 4.29 (≤6.0) | 3.7 (≥4.0) | 3.57 | 6.4 | ||

| Knee-ankle | 15.9 | 1.14 | 34.7 (≥40) | 12.4 | 2.3 | 43.9 |

| Sensory | Lat (ms) | Amp (µV) | CV (m/s) | Lat (ms) | Amp (µV) | CV (m/s) |

| Median-right (orthodromic) | ||||||

| Digit III-wrist | 2.75 (≤3.5) | 12.6 (≥7) | 51.3 (≥50) | 2.18 | 16 | 54.1 |

| Radial-right (antidromic) | ||||||

| Radial forearm-snuffbox | Not performed | 1.19 (≤2.9) | 43.2 (≥16) | 64.7 (≥50) | ||

| Sural-left (antidromic) | ||||||

| Midcalf-ankle | 2.29 (≤4.4) | 1.99 (≥6.0) | 42.8 (≥40) | 2.12 | 3.3 | 46.2 |

Amp, amplitude; CV, conduction velocity; Lat, latency; ms, milliseconds; m/s, metres per second; mV, millivolt; µV, microvolt.

Analysis of 56 genes associated with inherited peripheral neuropathy using a next-generation sequencing (NGS) targeted panel assay revealed compound heterozygous variants in SLC12A6 (NCBI RefSeq NM_133647.1): c.1592–2A>G, p.? in intron 11, not recorded in dbSNP, Exome Variant Server, or the Genome Aggregation Database and a heterozygous deletion of the entire coding region. Microarray comparative genomic hybridisation using the 8×60K ISCA v2.0 array (Oxford Gene Technology) with reference GRCh37/hg19 showed a 1.8 Mb deletion of the long arm of chromosome 15, at bands q13.3-q14. The karyotype is arr 15q13.3q14(32,899,499-34,695,199)x1. 16 protein-coding genes including SLC12A6 mapped to the minimum deleted segment; ARHGAP11A, AVEN, CHRM5, EMC4, EMC7, FMN1, SMN1, GOLGA8A, GREM1, KATNBL1, LPCAT4, NOP10, NUTM1, RYR3, SCG5 and SLC12A6. Parental segregation was confirmed; their mother is heterozygous for the deletion and their father is heterozygous for the c.1592–2G>A variant.

Outcome and follow-up

Overall, both twins reported no change in their weakness and at 12-month follow-up assessment, both had very similar neurological examination. The female twin can still run and her brother remains independent.

Discussion

These twins with compound heterozygous variants in SLC12A6 have a considerably milder phenotype than previously described with recessive disease. Typically, patients have significant difficulties ambulating, either never walking or becoming wheelchair users in childhood4 and marked mental retardation. Most die by their early 30 s.5 Recessive SLC12A6-associated peripheral neuropathy has been reported in 113 individuals to date, the vast majority from Quebec (table 2). More recently, heterozygous de novo SLC12A6 variants were documented as causing early-onset progressive CMT with or without spasticity in four individuals. Neither of our patients requires assistance to walk or has dysmorphic facies. Both achieved third level education and remain fully ambulant. Both have a high arched palate and a sensorimotor neuropathy in keeping with SLC12A6-associated phenotype but neither has ACC.

Table 2.

Summary of cases described with SLC12A6-associated phenotype

| Reference | n=Individuals (n=Families) |

SLC12A6 variants | LD | NP | Dysmorphic Features |

ACC | Other features |

| 2 | 85 (unknown) | Hom c.2436delG; c.2436delG / Hom c.3031C>T; Hom c.2023C>T; c.1584_1585delCTinsG |

NA | NA | NA | NA | ?macrocephaly, stenosis Aq Sylvius? |

| 8 | 2 (1) | c.1616G>A/ c.1118+1G>A | + | +in 1 | |||

| 9 | 1 | Hom for whole region of 15q13-q15 | + | + | + | + | Seizure |

| 10 | 3 (3) | c.(1478_1485)/(2032dup) Hom c.901del; Hom c.619C>T |

+ | + | + | + | White matter lesions on MRI |

| 11 | 1 | Hom c.571_572dup |

+ | + | + | + | Facial diplegia, eye movement abnormalities, cerebellar ataxia |

| 12 | 1 | Hom. c.3031C>T | + | + | + | + | Seizures |

| 13 | 10 (6) | Hom c.3031C>T; Hom c.2994_3003del | + | + | + | Seizures, gaze palsy | |

| 14 | 3 (2) | Hom c.3402C>T; Hom c.619C>T |

+ | + | + | Seizures | |

| 15 | 3 (1) | Hom c.1073+1G>A | + | + | + | + | |

| 16 | 2 (1) | c.2097dup /(?) | + | + | + | ||

| 17 | 1 | Hom c.2604delT | + | + | + | + | |

| 18 | 1 | Hom c.1943+1G>T | + | + | ─ | ─ | |

| 6 | 1 | Het c.2971A>G | ─ | + | ─ | ─ | |

| 7 | 3 (3) | Het c.620G>A Het c.2036A>G |

─ | + | ─ | ─ | Spasticity in 1 |

ACC, agenesis of the corpus callosum; het, heterozygous; hom, homozygous; LD, learning difficulty; NA, not available; NP, neuropathy.

In contrast to our twins with a much milder phenotype than usually described in recessive SLC12A6-associated peripheral neuropathy, normal cognitive development with normal MRI brain has been reported only in four unrelated individuals with heterozygous de novo dominant variants in the SCL12A6 gene.6 7

The SLC12A6 NM_133647.1:c.1592–2A>G, p.? has not been described previously and is classified as likely pathogenic as per the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines. The guanine nucleotide is highly conserved and this substitution is predicted to affect splicing; potentially causing exon skipping and resulting in premature truncation of the mRNA product leading to nonsense-mediated decay. In addition, no protein would be produced from an allele carrying the whole gene deletion. It is therefore possible that c.1592–2A>G along with deletion of the entire coding region in trans could result in absence of SLC12A6 protein.

These cases expand the clinical and genetic spectrum of SLC12A6-associated phenotype and highlight the importance of careful clinical phenotyping. With widespread availability of NGS, it is increasingly common to find potentially causative variants in unexpected genes. SLC12A6 would not have been considered as a candidate gene for testing in these twins given their atypical presentation; however, NGS technology overcomes the limitations of pre-existing genotype–phenotype associations. The case also highlights the benefit of a co-ordinated NGS and microarray approach in order to provide an accurate diagnosis. With the advancement of genetic technology, further expansion of clinical phenotypes is anticipated.

Learning points.

SLC12A6-associated phenotype ranges from severe progressive sensorimotor neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum and cognitive impairment to pure neuropathy.

It is increasingly common to find potentially causative variants in unexpected genes with widespread availability of next-generation sequencing.

These cases highlight the advantage of co-ordinated next-generation sequencing and microarray approach to provide an accurate diagnosis.

Careful clinical phenotyping is crucial.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Michael D Alexander for providing the neurophysiology data; Thalia Antoniadi, Lisa Burvill-Holmes and Joanne Davies for their assistance in interpreting genetic results and Dr Michael Hennessy for patient referral and review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the manuscript as submitted. PB-M contributed to data acquisition, drafting and revising the article; PMN contributed to conception and design, data acquisition, drafting and revising the article; SB-J contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and critically revising the article; SMM contributed to conception and design, data analysis, interpretation and critically revising the article. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

References

- 1.Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth's disease. Clin Genet 1974;6:98–118. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard HC, Mount DB, Rochefort D, et al. The K-Cl cotransporter KCC3 is mutant in a severe peripheral neuropathy associated with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Nat Genet 2002;32:384–92. 10.1038/ng1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy SM, Herrmann DN, McDermott MP, et al. Reliability of the CMT neuropathy score (second version) in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2011;16:191–8. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00350.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yiu EM, Ryan MM. Genetic axonal neuropathies and neuronopathies of pre-natal and infantile onset. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012;17:285–300. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dupré N, Howard HC, Mathieu J, et al. Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum. Ann Neurol 2003;54:9–18. 10.1002/ana.77777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahle KT, Flores B, Bharucha-Goebel D, et al. Peripheral motor neuropathy is associated with defective kinase regulation of the KCC3 cotransporter. Sci Signal 2016;9:ra77. 10.1126/scisignal.aae0546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park J, Flores BR, Scherer K, et al. De novo variants in SLC12A6 cause sporadic early-onset progressive sensorimotor neuropathy. J Med Genet 2020;57:283–8. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Hehr U, von Kalle T, et al. Andermann syndrome can be a phenocopy of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy--report of a discordant sibship with a compound heterozygous mutation of the KCC3 gene. Neuropediatrics 2009;40:129–33. 10.1055/s-0029-1234084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demir E, Irobi J, Erdem S, et al. Andermann syndrome in a Turkish patient. J Child Neurol 2003;18:76–9. 10.1177/08830738030180011901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uyanik G, Elcioglu N, Penzien J, et al. Novel truncating and missense mutations of the KCC3 gene associated with Andermann syndrome. Neurology 2006;66:1044–8. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000204181.31175.8b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lourenço CM, Dupré N, Rivière J-B, et al. Expanding the differential diagnosis of inherited neuropathies with non-uniform conduction: Andermann syndrome. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2012;17:123–7. 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2012.00374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degerliyurt A, Akgumus G, Caglar C, et al. A new patient with Andermann syndrome: an underdiagnosed clinical genetics entity? Genet Couns 2013;24:283–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salin-Cantegrel A, Rivière J-B, Dupré N, et al. Distal truncation of KCC3 in non-French Canadian HMSN/ACC families. Neurology 2007;69:1350–5. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000291779.35643.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salin-Cantegrel A, Rivière J-B, Shekarabi M, et al. Transit defect of potassium-chloride co-transporter 3 is a major pathogenic mechanism in hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum. J Biol Chem 2011;286:28456–65. 10.1074/jbc.M111.226894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akçakaya NH, Yapıcı Z, Tunca Ceren İskender, et al. A new splice-site mutation in SLC12A6 causing Andermann syndrome with motor neuronopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018;89:1123–5. 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rius R, González-Del Angel A, Velázquez-Aragón JA, et al. Identification of a novel SLC12A6 pathogenic variant associated with hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy with agenesis of the corpus callosum (HMSN/ACC) in a non-French-Canadian family. Neurol India 2018;66:1162–5. 10.4103/0028-3886.236987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacheva I, Todorov T, Halil Z, et al. First case of Roma ethnic origin with Andermann syndrome: a novel frameshift mutation in exon 20 of SLC12A6 gene. Am J Med Genet A 2019;179:1020–4. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al Shibli N, Al-Maawali A, Elmanzalawy A, et al. A novel splice-site variant in SLC12A6 causes andermann syndrome without agenesis of the corpus callosum. J Pediatr Genet 2020;9:293–5. 10.1055/s-0039-1700975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]