Abstract

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis refers to central nervous system infection by dematiaceous mould or by dark walled fungi which contain the dark pigment melanin in their cell wall which adds to the virulence of fungus. These dematiaceous fungi can cause a variety of central nervous infections including invasive sinusitis, brain abscess, meningitis, myelitis and arachnoiditis. Cladophialophora bantiana among these dematiaceous fungi is the most common cause of brain abscess in immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals and is known to occur worldwide though is predominantly reported from subtropical regions especially the Asian subcontinent. It is difficult to differentiate these abscesses radiologically from high-grade gliomas, primary central nervous system lymphoma or other infections including toxoplasmosis, nocardiosis, tuberculosis and listeriosis. We describe a 19-year-old male patient with a cerebral abscess caused by C. bantiana where the diagnosis could be suspected by typical MR spectroscopic findings and by identifying the fungus from a lymph node biopsy.

Keywords: infection (neurology), tropical medicine (infectious disease), radiology

Background

Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis refers to central nervous system infection by dermatiaceous mould or by dark walled fungi which contain the dark pigment melanin in their cell wall and this adds to the virulence of the fungus. Melanised moulds comprise more than 70 genera and 150 species causing human infections.1 The genus Cladophialophora includes neurotropic fungi Cladophialophora bantiana and C. modesta which predominantly cause brain infections. C. bantiana is reported worldwide though with a general preference for warm climates with high humidity as found in Asia and is the most common cause of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis presenting as cerebral abscess. C. bantiana cerebral abscesses occur predominantly in younger (average age 35 years) males (70%) and significantly 50% of them are immunocompetent.2 Vulnerable immunocompromised individuals include post organ transplantation, primary immunodeficiency of unknown origin, diabetes, neutropenic patients and patients on long-term immune suppressants.

C. bantiana is a soil saprophyte and inhabits living and dead plant material. Exposure to soil or dead or living plant material as in farming or gardening may result in paranasal or pulmonary infections through inhalation. It may also enter the subcutaneous tissue by traumatic inoculation. Involvement of the brain occurs due to direct invasive spread from the paranasal sinuses or through a haematogenous spread from the primary site.3 Most patients with C. bantiana cerebral abscess have isolated brain lesions with no identifiable systemic infection sites. Cerebral abscess caused by C. bantiana carry a high mortality of up to 70%.4 Combined management by radical neurosurgical resection along with aggressive (single or combined) antifungal medical therapy is the most successful therapeutic strategy reported to date. Early recognition and institution of appropriate therapeutic measures are of extreme importance in reducing the mortality from this devastating illness.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old boy presented with a 1-week history of progressively worsening severe holocranial headache accompanied with repeated episodes of severe projectile vomiting. No history of any fever, visual disturbances nor any focal neurological deficit was reported. No history of COVID-19 infection was reported. History was significant for a 6-month febrile episode having occurred 3 years prior. Evaluation at that time had revealed evidence of cervical, mediastinal, hilar and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Excision biopsy of cervical lymph node had revealed an infective pathology with smears and cultures revealing infection with pigmented fungus C. bantiana and patient had responded to a 3-month course of oral voriconazole with resolution of fever and resolution of the lymphadenopathy with appearance of calcification in some of the lymph nodes.

At the time of current presentation, patient was conscious though lethargic, was afebrile with no evidence of papilloedema. No focal neurological deficit was observed and meningeal signs were not elicitable. General physical examination revealed a palpably enlarged right supraclavicular lymph node with multiple subcentimetre, non-tender, non-matted bilateral superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes. MRI brain revealed a partially rounded, ill-defined marginated lesion in the right basal ganglia region with extension to the right frontal and temporal lobes suggestive of a high-grade glioma (figure 1). In view of history of fungal lymphadenitis, an alternate possibility of C. bantiana fungal cerebral abscess was considered and MR brain spectroscopy was performed. MR spectroscopy revealed mildly elevated choline peaks with reduced NAA peak (mildly elevated CHO: NAA ratio) with elevated lipid lactate peak suggestive of infective process with primary possibility of a fungal abscess(figure 2). PET-CT of the entire body revealed mildly FDG avid multiple enhancing bilateral cervical and bilateral supraclavicular node (figures 3 and 4). Excision biopsy of right supraclavicular lymph node was suggestive of fungal lymphadenitis with necrotising granulomatous inflammatory response suggestive of infection by pigmented (dematiaceous) fungus (figure 5D). Blood investigations revealed immunodeficient state with T lymphocyte deficiency. Surgical excision of the presumed fungal abscess was planned and liposomal amphotericin B along with oral posaconazole was started. Family and patient refused for surgical excision and hence medical management with liposomal amphotericin B and posaconazole combination therapy was attempted. Patient showed significant improvement with resolution of headache and vomiting and continued to have an intact neurological status. MRI brain was repeated after 2 weeks of medical therapy revealed moderate increase in the lesion as well as the oedema. Apart from radiological worsening, patient also developed clinical remergence of moderately severe intermittent headache with early morning vomitings. Right frontal craniotomy and excision of the lesion was subsequently performed and the peroperative clinical impression was of an abscess with extensive black pigment (figure 5A).

Figure 1.

MRI brain. (A) T1W. (B) T2W. (C) FLAIR. (D) DWI. (E) SWI. (F) Postgadolinium scans in axial planes shows a mixed intensity mass lesion in right basal ganglia and periventricular white matter with perilesional oedema extending into frontotemporal cortex. There are areas of blooming seen within the lesion (arrow) in SW images representing areas of haemorrhage (angioinvasive). Intense peripheral irregular enhancement seen in (F) postgadolinium scans. Areas of restricted diffusion seen within the lesion.

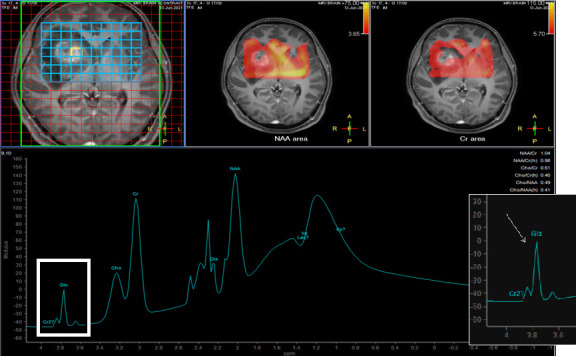

Figure 2.

Spectroscopy through the lesion with mixed intensity mass lesion in right basal ganglia and periventricular white matter reveals no significant raise in choline peak. There are characteristic peak between 3.6 and 3.8 ppm representing ‘trehalose’ peak (arrow) specific for fungal infection.

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph (A) reveals thickening or right paratracheal stripe. CT scan reveals supraclavicular lymph nodes (arrows in (B)).

Figure 4.

PET scans reveals enlarged supraclavicular (arrows in 1A) and subcarinal and infrahilar lymph nodes (2B) with increased uptake in corresponding lymph nodes in 1A and 2B.

Figure 5.

Specimen obtained as brain biopsy revealed Cladophialophora bantiana. (A) macroscopic. (B) Microscopic examination. (C) Morphology in culture growth. (D) H&E stain (40×) showing several intact and disintegrated slender fungal hyphae with yellowish brown discolouration within the areas of necrosis and also seen ingested by histiocytic giant cells. These hyphae showed septations, acute-angled branching and constrictions near septations, imparting a beaded appearance (white arrow). (E) Grocott stain (40×): highlighted fungal hyphae (arrow); (F) PAS stain (40×): highlighted fungal hyphae (arrow).

Postoperatively, patient developed subtle left hemiparesis though headache and vomiting settled and serial further MRI examinations (figure 6) revealed progressive improvement of the residual right frontotemporal-basal ganglionic abscess.

Figure 6.

Postoperative MRI brain scans. (A) T1W. (B) T2W. (C) Post gadolinium scans in axial planes shows postoperative changes with postoperative defect and areas of haemorrhage.

Investigations

MRI brain revealed a partially rounded, ill-defined marginated lesion in the right basal ganglia region with extension to the right frontal and temporal lobes with the lesion displaying hypointense signal on T1 with peripheral hyperintensity and hyperintense signal on T2/FLAIR with peripheral hypointensity with diffusion restriction in the periphery of the lesion with few foci of blooming on SWI images with post contrast thick and irregular peripheral nodular enhancement with significant perilesional oedema extending into right basal ganglia and in right insular cortex and temporal region causing effacement of adjacent sulci and partial effacement of right lateral ventricle, suggestive of a possibility of a high-grade glioma (figure 1).

MR spectroscopy revealed mildly elevated choline peaks with reduced NAA peak (mildly elevated CHO: NAA ratio) with elevated lipid lactate peak in multivoxel assessment of the lesion. The signal characteristics of the lesion along with the spectroscopic findings were in favour of an infective process with primary possibility of a fungal abscess (figure 2).

PET-CT of the entire body revealed peripherally FDG avid (SUV max. 11.98) rounded lesion with significant perilesional oedema in right frontal and basal ganglionic region measuring approximately 2.0×1.5 cms in size.). Mildly FDG avid (SUV Max: 3.80) multiple enhancing bilateral cervical and left posterior cervical nodes, mildly FDG avid (SUV Max: 5.79) enlarged bilateral supraclavicular nodes with a large right supraclavicular node measuring 2.2×1.3 cms in size and non-FDG avid enlarged mediastinal nodes with calcifications in prevascular, right paratracheal, AP window and right hilar regions, largest prevascular node measuring 2.5×1.6 cms in size were observed. FDG avid (SUV max. 7.68) enlarged subcarinal node, measuring 3.0×2.1 cms in size and faintly FDG avid (SUV max. 3.86) enlarged peripancreatic node measuring 2.5×1.8 cms in size with old residual hilar, mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes were seen (figures 3 and 4).

Excision biopsy (figure 5) of right supraclavicular lymph node revealed complete effacement of normal lymph node architecture by multiple well defined epithelioid cell granulomas showing both Langhan’s type and foreign body type histiocytic giant cells, interspersed with a background infiltrate of lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells and histiocytes. The lymph node was traversed by multiple thick hyalinised fibrous bands. Many of the granulomas showed large central areas of suppurative necrosis. Several intact and disintegrated slender fungal hyphae with yellowish brown discolouration were noted within the areas of necrosis and also seen ingested by histiocytic giant cells. These hyphae showed septations, acute angled branching and constrictions near septations, imparting a beaded appearance. These fungi were highlighted on PAS and Grocott’s stains. Ziehl Neelsen stain did not reveal any acid fast bacilli and no evidence of any neoplastic lesion was seen.

Serum galactomannan was negative, HIV 1 and 2 was negative, serum immunodeficiency panel type 1 revealed reduced %CD3/total T lymphocytes (46.39) with reduced absolute CD 3 count of 308 along with reduced %CD 4 Helper/Inducer cells(26.90) and reduced Absolute CD 4 count (179/μL). Absolute CD 8 count was also reduced (117/μL). Absolute CD19 count was normal (252/μL). Absolute CD16/CD56 (NK cell) count was also within normal limits (95/μL). Evaluation for myeloperoxidase enzyme deficiency could not be conducted. Repeat T cell count after completion of medical therapy has been planned.

Differential diagnosis

On the basis of MRI brain, a possibility of a intracranial space occupying lesion with perilesional oedema in right basal ganglia which is T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense suggestive of high-grade glioma, primary CNS lymphoma or cerebral metastasis was considered. The differential diagnosis in immunocompromised hosts additionally includes other opportunistic infections including toxoplasmosis, listeriosis or nocardiosis, fungal and tubercular. On MR spectroscopy, mildly elevated choline peaks with reduced NAA peak (mildly elevated CHO: NAA ratio) with elevated lipid lactate peak suggestive of infective process like with primary possibility of a fungal abscess. Fungal aetiology of C. bantiana was confirmed on biopsy.

Treatment

Patient was initially managed for 2 weeks with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B along with oral posaconazole with clinical and radiological worsening. A craniotomy and radical excision of the abscess was performed subsequently; this was followed by a 4-week course of combined intravenous liposomal amphotericin B with oral voriconazole and then oral voriconazole alone.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient initially had both clinical as well as radiological improvement with resolution of headache, vomiting and left hemiparesis. This was followed subsequently by reemergence of clinical symptoms and radiological enlargement of the lesion and oedema leading to craniotomy and radical excision. Postoperatively patient was managed with a 6-week course of combined intravenous liposomal amphotericin B along with oral voriconazole. Patient required intensification of treatment with continuation of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B and replacement of voriconazole with oral posaconazol and flucytocine followed by a repeat craniotomy and excision of relapsed right hemispheric fungal abscess at a teaching hospital.

Discussion

C. bantiana is a highly neurotropic fungus and is the most common cause of cerebral phaeohyphomycosis. Exposure to soil or dead or living plant material as in farming or gardening may result in paranasal or pulmonary infection by inhalation or subcutaneous tissue infection by traumatic inoculation. Spread to the brain may occur due to invasive spread from the paranasal sinuses or by haematogenous spread from a pulmonary or systemic focus. The first case of brain abscess caused by C. bantiana was reported in 1952 in an immunocompetent American patient.5 Less than 150 patients with culture proven cerebral abscesses caused by C. bantiana have been described since then mostly as case reports or small case series. One of the large series of 10 cases over 27 years was reported from South India.6 One hundred and twenty-four patients with culture proven C. bantiana abscess were described in one review article from North India which included 103 cases published in literature from 1952 till 2014 and another 21 cases from the centre.7 Clinically, patients with C. bantiana brain abscess present with insidious onset and progressively worsening headaches followed by slow evolving neurological signs. Fever is not usually present. The abscess maybe single or multiple. Most patients with C. bantiana cerebral abscess have isolated brain lesions with no identifiable systemic infection sites. Radiologically, C. bantiana abscesses cannot be differentiated with certainty from primary neoplastic lesion like glioblastoma, primary CNS lymphoma or cerebral metastasis. The differential diagnosis in immunocompromised hosts additionally includes other opportunistic infections including toxoplasmosis, listeriosis or nocardiosis. Cerebral biopsy with histological studies and exhaustive microbiological cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi are considered the gold diagnostic standard. The mortality of cerebral C. bantiana abscess is extremely high and may reach 70% despite radical surgical resection accompanied with pharmacological treatment (single or combination antifungal drugs).

Radical surgical excision for C. bantiana cerebral abscess is recommended by guidelines,8 and has been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity compared with other procedures like aspiration or partial excision. Follow-up imaging with MRI is important in the management to observe for response after surgery and to document a response to systemic antifungal therapy. Recommendations for treatment regimes and the duration of the antifungal therapy is lacking on account of availability of only a limited number of cases. The duration of therapy is based on the clinical severity, underlying predisposing condition in the host, and the response to treatment. Reducing immunosuppression therapy in patients on immunosuppressant medication is advisable. The most commonly used regime is intravenous amphotericin alone or accompanied with another antifungal agent.9 Fluconazole is not effective against C. bantiana. Flucytosine, itraconazole and the newer second generation triazole agents voriconazole and posaconazole are the drugs which may be combined with amphotericin B. Voriconazole has better blood brain barrier penetration than posaconazole. The most common adverse effect reported with voriconazole is transient visual disturbances and liver toxicity. Posaconazole which is also active, both in vitro and in vivo against C. bantiana, may be considered as an option in patients with pre-existing liver disease. Newer antifungals echinocandins, including caspofungin, micafungin and anidulafungin, are less effective against the dematiaceous fungi and have lesser brain penetration.

Patient’s perspective.

This disease came to me slowly and I was not aware regarding severity of disease. I was fortunate to have a correct diagnosis and treatment of my illness. Now, I and am thankful to the treating doctor.

Learning points.

To our knowledge, no other case presenting with Cladophialophora bantiana lymphadenitis with a subsequent/simultaneous intracranial abscess has been reported. This suggests that identification of any peripheral localisation of infection in subcutaneous tissues, sinuses, lymph nodes or the lung may be helpful in diagnosis.

Search for these peripheral sites should be conducted meticulously in patients with suspected C. bantiana infection.

MR spectroscopy can be helpful in suspecting and differentiating a fungal abscess from neoplastic lesions.

Our case highlights the fact that radical excision of the lesion along with combined medical therapy with amphotericin B and another antifungal drug remains the treatment of choice of this devastating illness as initial attempted medical therapy alone in our patient for 2 weeks failed to produce a favourable response.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Seema Singhal (Senior consultant Pathology, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi) had been a great help in reporting histopathology slides. Dr. Raman Sardhana (Senior Consultant Microbiology, Indraprastha Apollo Hospital, New Delhi) helped in microbiological sampling and reporting.

Footnotes

Contributors: VS drafted the case report. SP did research work. NG reported MRI and PET scans. HR and reported microbiology sections.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

References

- 1.Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23:884–928. 10.1128/CMR.00019-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarcioglu AS, Guarro J, De Hoog S, et al. An updated comprehensive systematic review of cladophialophora bantiana and analysis of epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of cerebral cases. Med Mycol 2017;55:579–60. 10.1093/mmy/myw124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jayakeerthi SR, Dias M, Nagarathna S, et al. Brain abscess due to cladophialophora bantiana. Indian J Med Microbiol 2004;22:193–5. 10.1016/S0255-0857(21)02837-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revankar SG, Sutton DA, Rinaldi MG. Primary central nervous system phaeohyphomycosis: a review of 101 cases. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:206–16. 10.1086/380635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binford CH, Thompson RK, Gorham ME. Mycotic brain abscess due to cladosporium trichoides, a new species; report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol 1952;22:535–42. 10.1093/ajcp/22.6.535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg N, Devi IB, Vajramani GV, et al. Central nervous system cladosporiosis: an account of ten culture-proven cases. Neurol India 2007;55:282–8. 10.4103/0028-3886.35690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakrabarti A, Kaur H, Rudramurthy SM, et al. Brain abscess due to cladophialophora bantiana: a review of 124 cases. Med Mycol 2016;54:111–9. 10.1093/mmy/myv091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chowdhary A, Meis JF, Guarro J, et al. Escmid and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of systemic phaeohyphomycosis: diseases caused by black fungi. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20 Suppl 3:47–75. 10.1111/1469-0691.12515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group International prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017;4:ofx 200. 10.1093/ofid/ofx200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]