Abstract

Laboratory identification of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) is a key step in controlling its spread. Our survey showed that most VA laboratories follow VA guidelines for initial CRE identification, while 55.0% use PCR to confirm carbapenemase production. Most respondents were knowledgeable about CRE guidelines; barriers included staffing, training, and financial resources.

Introduction

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are difficult to treat multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) associated with high morbidity and mortality.1 Laboratory identification of CRE and distinguishing if CRE produce a carbapenemase (CP-CRE) are critical to controlling spread because they help facilitate timely implementation of infection control (IC) measures. Laboratory practices regarding CRE have evolved, with newer molecular techniques being more accurate for identifying CP-CRE compared to phenotypic tests; however, cost and limited availability of timely molecular testing limit widespread implementation.

Recently, the VA disseminated the VHA 2017 Guideline for Control of Carbapenemase Producing-Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE).2 This guideline updates a prior 2015 guideline and addresses changes in the collection of surveillance specimens, specific microorganisms to be assessed, and definitions of resistance. The 2017 VA guideline also includes algorithms to standardize CRE screening, identification, and reporting. Although the VA 2017 guideline is similar to guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)3, key differences exist, most notably the CDC’s inclusion of ertapenem in the antibiotic susceptibility criteria for the CRE definition.4 Few data exist on current laboratory practices for CRE/CP-CRE identification and reporting. This study describes findings from a national survey on laboratory practices regarding CRE in VA facilities after dissemination of the 2017 guideline.

Methods

A cross-sectional electronic survey was disseminated June 26, 2017-November 2, 2017 to laboratory and/or microbiology supervisors at 152 VA medical centers (VAMCs). Subsequent e-mail reminders were targeted to 129 VAMCs that provide inpatient acute care to Veterans. Surveys were completed by lab personnel who were knowledgeable about implementation of CRE guidelines at their facility. Respondents were encouraged to consult colleagues if needed.

The survey was developed by study team members using guidance from prior survey studies on CRE5 and with input from the VA Multidrug Resistant Organism Program Office. It was administered using VA’s Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software.6 The survey focused on laboratory CRE identification, reporting, screening, and guideline implementation, and was pilot tested with five facilities to ensure clarity and reliability. Survey responses were summarized with descriptive statistics. VAMCs are classified into complexity levels determined partly by patient characteristics (Levels 1a-c, 2, and 3). We defined high complexity facilities as Levels 1a-c and low complexity facilities as Levels 2 and 3. Dichotomous comparisons of survey responses by facility complexity and location were assessed using Fisher’s exact test. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)7 was used to code responses to open-ended questions regarding barriers and facilitators to guideline implementation.

Results

The overall survey response rate was 93.0% (120/129 sites). Paralleling VA acute care facilities in general, respondents were mostly urban (80.0%) and high complexity (64.9%). Most respondents reported that the incidence of new cases of CRE/CP-CRE was <1/month at their facility (57.5%), while 34.2% reported they have never seen a CRE/CP-CRE case. Only 1.7% described their facility as located in a region with high CRE/CP-CRE prevalence. Almost all facilities reported using VA guidelines (91.6%); some also use CDC (20.0%) and state/local resources (27.5%) for additional guidance.

Over three quarters (79.2%) of facilities reported using imipenem, meropenem and/or doripenem MIC ≥4 mcg/mL as the first step to identify CRE from clinical cultures, as recommended in the VA guideline. Eight (6.7%) facilities reported using other carbapenem MIC cutoffs and/or including ertapenem. 91 facilities (75.8%) routinely perform additional testing to confirm that a CRE isolate produces a carbapenemase, of which 66 (72.5%) use PCR for confirmation. About half of sites that perform confirmatory testing do so on-site (47.3%), while the other half send isolates to a reference laboratory. Most facilities (72.0%) provide a report of presumptive CRE to either IC and/or the treating providers; nearly all (97.4%) respondents contact IC when CP-CRE are confirmed. Over a third (35.5%) of facilities reported 25-48 hour turnaround time for final confirmation of CP-CRE from a clinical culture, with 31% reporting >72 hours.

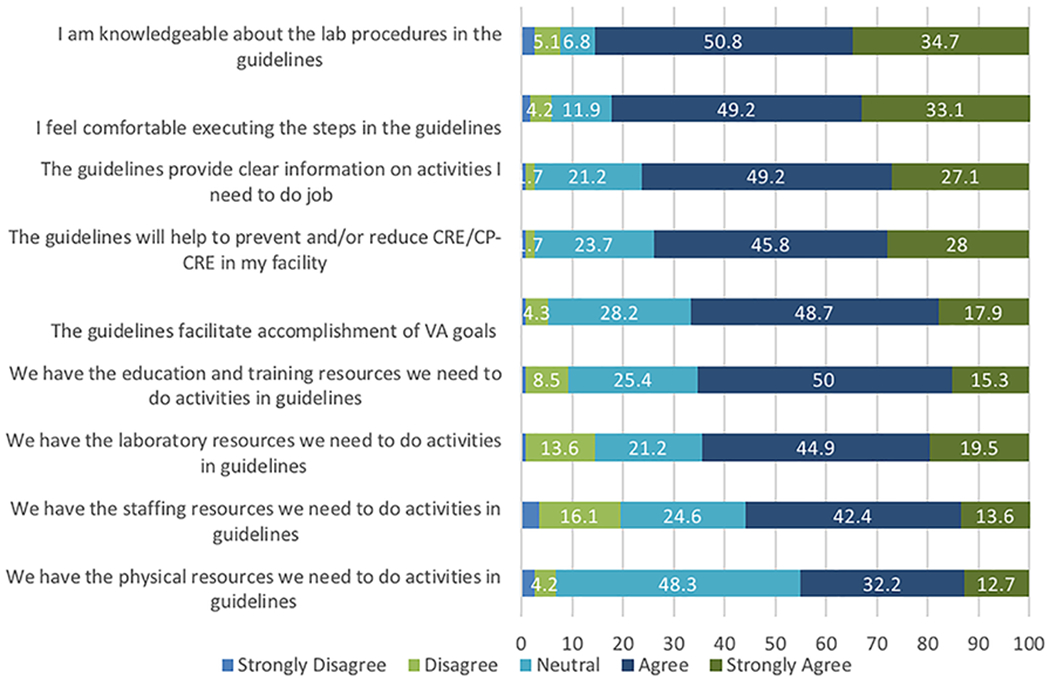

Most (79.8%) respondents reported being involved in guideline implementation, being knowledgeable about the lab procedures in the guidelines, and being comfortable executing the guidelines (Figure 1). Many respondents agreed or strongly agreed they had the resources needed to follow the guidelines. However, only 55.9% agreed or strongly agreed they had adequate staffing resources and only 44.9% agreed or strongly agreed they had adequate physical resources. Common implementation barriers reported using CFIR constructs were availability of resources (29%; e.g., limited staffing), access to knowledge and information (12%; e.g., adequate training), and costs (12%; e.g., laboratory supplies).

Figure 1.

Percent of survey respondents expressing varying levels of agreement with statements about the VA 2017 CRE guidelines. The different levels of agreement are indicated by shades of gray.

Differences in survey responses were observed by facility complexity and location (Table 1). High complexity facilities were more likely to report having had any CRE cases, to report presumptive CRE to IC, to confirm carbapenemases, and to use PCR specifically for carbapenemase confirmation. Both high complexity and urban facilities were more likely to be knowledgeable about the guidelines and laboratory procedures, to feel comfortable executing the guidelines, and to feel they had adequate local resources for guideline implementation.

Table 1.

Survey responses

| Survey response | Facility complexity | Facility location | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of responsesa | High (n=78) | Low (n=42) | p-value | Rural (n=24) | Urban (n=96) | p-value | |

| Laboratory practices | |||||||

| No CRE cases seen at facility | 120 | 16 (20.5%) | 25 (59.5%) | <0.01 | 19 (79.2%) | 83 (86.5%) | 0.35 |

| Use carbapenem MIC to initially identify CRE | 120 | 65 (83.3%) | 30 (71.4%) | 0.16 | 17 (70.8%) | 78 (81.3%) | 0.27 |

| Provide preliminary report of CRE to IC | 118 | 61 (78.2%) | 24 (60.0%) | 0.05 | 13 (56.5%) | 72 (75.8%) | 0.07 |

| Confirm carbapenemase production | 118 | 65 (83.3%) | 26 (65%) | 0.03 | 15 (65.2%) | 76 (80.0%) | 0.17 |

| If yes, confirm with PCR | 91 | 43 (82.7%) | 9 (17.3%) | 0.01 | 6 (11.5%) | 46 (88.5%) | 0.16 |

| Implementationb | |||||||

| Lab involved in guidelines implementation | 119 | 65 (83.3%) | 30 (73.2%) | 0.23 | 14 (58.3%) | 81 (85.3%) | 0.01 |

| Generally knowledgeable about guidelines | 119 | 71 (91.0%) | 28 (68.3%) | <0.01 | 16 (66.7%) | 83 (87.4%) | 0.03 |

| Knowledgeable about laboratory procedures | 118 | 71 (91.0%) | 30 (83.3%) | 0.01 | 16 (69.6%) | 85 (89.5%) | 0.02 |

| Comfortable executing guidelines | 118 | 67 (87.0%) | 30 (73.2%) | 0.08 | 15 (65.2%) | 82 (86.3%) | 0.03 |

| Adequate national dissemination of guidelines | 118 | 54 (70.1%) | 19 (46.3%) | 0.02 | 10 (43.5%) | 63 (66.3%) | 0.06 |

| Adequate local resources required for implementation | 118 | 54 (70.1%) | 17 (41.5%) | <0.01 | 9 (39.1%) | 62 (65.3%) | 0.03 |

| Education/training | 118 | 56 (72.7%) | 21 (51.2%) | 0.03 | 10 (43.5%) | 67 (70.5%) | 0.03 |

| Staffing | 118 | 47 (61.0%) | 19 (46.3%) | 0.17 | 6 (26.1%) | 60 (63.2%) | <0.01 |

| Physical | 118 | 37 (48.1%) | 16 (39.0%) | 0.43 | 8 (34.8%) | 45 (47.4%) | 0.35 |

| Laboratory | 118 | 55 (71.4%) | 21 (51.2%) | 0.04 | 9 (39.1%) | 67 (70.5%) | <0.01 |

CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; IC, infection control

Number of facilities who answered that particular question out of the 120 total facilities responding to the survey. Percentages are calculating using the number of facilities responding to a particular question.

Responses considered positive for implementation questions were ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’

Discussion

Laboratory diagnosis and reporting of CRE is critical to conducting surveillance, allocating infection prevention resources, and implementing timely infection control (IC). As strategies for identifying CRE and confirming CP-CRE have evolved and improved, national VA CRE guidelines have been updated accordingly. However, few data are available on laboratory practices for CRE identification and reporting. Prior surveys were focused only on adherence to revised CLSI breakpoints for Enterobacteriaceae,8 did not use national data,9 or addressed only IC strategies rather than laboratory practices.10

Our survey found that most VAMCs have encountered CRE and use the 2017 VA guidelines, following recommendations for initial CRE identification using updated carbapenem breakpoints. Most laboratories helped implement the CRE guidelines, reported being knowledgeable and comfortable with the guidelines, and received guideline training and information. Notably, both low complexity and rural facilities described being less knowledgeable and reported inadequate local resources for guideline implementation. Low complexity facilities were also less likely to perform on-site confirmatory testing for carbapenemases and less likely to use PCR for confirmation. This result may reflect low CRE prevalence at these facilities, less knowledge of the guidelines, and/or limited availability of laboratory resources. Overall, lack of onsite PCR testing was one of the most commonly cited barriers to full guideline implementation; only half of facilities confirm CP-CRE using PCR. Some facilities addressed this limitation by sending isolates to other labs; however, this raises issues regarding timeliness of reporting, as evidenced by the fact that over a third of facilities reported final confirmation turnaround time >72 hours.

A limitation of this study is that it was conducted within the VA, and survey respondents and laboratory practices may be different compared to non-VA hospitals. Furthermore, as with most survey studies, recall bias may have affected the accuracy of respondents’ answers. Our high survey response rate (93%) may have minimized the impact of isolated inaccuracies in survey responses due to recall bias in an individual respondent.

In summary, many VA laboratories have experience in identifying CRE, rapidly started following the 2017 VA guidelines, and reported active engagement in guideline implementation. However, many facilities do not confirm carbapenemases using PCR or send isolates to other laboratories for testing, with most respondents citing limited staffing, training, and financial/laboratory resources. These barriers must be addressed to support full and successful guideline implementation and to optimize identification, reporting, and control of CRE.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Michael Lin for guidance with the survey questions. This work was supported by The Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUE 15-269). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government. All authors report no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures relevant to this article.

References:

- 1.Xu L, Sun X, Ma X Systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality of patients infected with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2017;16:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2017 Guideline for Control of Carbapenemase-producing Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CP-CRE). Washington, DC: National Infectious Disease Service MDRO Prevention Office, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facility Guidance for Control of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE): November 2015 Update -- CRE Toolkit. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/cre/CRE-guidance-508.pdf. Accessed Nov 1, 2017.

- 4.Fitzpatrick MA, Suda KJ, Jones MM, et al. Effect of varying federal definitions on prevalence and characteristics associated with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in veterans with spinal cord injury. Am J Infect Control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin MY, Lyles-Banks RD, Lolans K, et al. The importance of long-term acute care hospitals in the regional epidemiology of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1246–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Humphries RM, Hindler JA, Epson E, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae detection practices in California: what are we missing? Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:1061–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thibodeau E, Duncan R, Snydman DR, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a statewide survey of detection in Massachusetts hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:954–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gohil SK, Singh R, Chang J, et al. Emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Orange County, California, and support for early regional strategies to limit spread. Am J Infect Control 2017;45:1177–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]