Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The prevalence of water pipe smoking is increasing among young people, but there are limited data on its use among adolescents in Iran. The aim of this study is to investigate the prevalence of WP smoking and associated risk factors among female adolescents in Western Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This cross-sectional study was conducted in schools. It included 1302 middle school (48.1%) and high school (51.9%) female students (grades 7–12) recruited through stage random sampling and conducted in 2019 in the western city of Kermanshah, Iran. The data collection tool was a researcher-made questionnaire. Logistic regression analyses and descriptive statistics were executed using SPSS version 22.

RESULTS:

The mean (standard deviation) ages of the students and the ages when the participants started WP smoking were 15.22 ± 1.85 and 13.64 (1.64), respectively. Nearly 32.2% had a single experience of WP smoking during their lifetime and 20.4% were current consumers of WP. Most of the subjects smoked WPs at their friends’ home (45.8%) and with their friends (47.4%). The significantly important factors that affect WP smoking in these age groups are the father's and mother's occupation, family size, living with others, father's education, having a friend who smokes WPs, friends’ encouragement to smoke WP, and being in a family that smoke WPs.

CONCLUSIONS:

Considering the increasing popularity of WP among adolescent females and its increasing prevalence, the results showed that Water pipe smoking with friends played a key role in WP smoking among female adolescents. There is a need to design interventional studies to increase people's skills and to design and implement programs to prevent water pipe.

Keywords: Adolescents, female, student, water pipe smoking

Introduction

The increasing usage of water pipes (WPs) reveals a worrying scenario.[1] Approximately 4.9 million middle and high school students were current tobacco users in 2018.[2] The prevalence of WP smoking ranges from 6% to 34% in adolescents in the Middle East and 5%–17% among American adolescents.[3,4] In Iran, the prevalence of current WP smoking and ever WP smoking was 26.3% and 36.4%, respectively.[5]

The lower age of water pipe smoking and the popularity of water pipe in adolescence, especially in females, have become major concerns.[7] The results of the latest national survey of risk factors of non-communicable disease showed that more than half of female tobacco users are hookah consumers.[8]

Results of a national survey showed that the prevalence of daily WP smoking using WPs in Iran was on an average 3.5 times a day (2.8 in males and 4.5 in females). Furthermore, more than 50% of Iranian females smoke tobacco and smoke it with WPs.[9]

In Middle East countries, people have not acquired negative attitudes toward WP, and it is much more acceptable in the society than other types of tobacco.[9,10]

Although WP smoking is considered a means of entertainment by Iranian females, it is also used as a way to have fun with friends. Moreover, WP smoking is always a pretext to get-together with old friends and family members, as well as a method for creation of intimate social networks.[11]

It is known that tobacco smoking among females has nearly as many risks as that of males, but compared to males, they are more susceptible to some types of lung cancers.[12]

Besides, complications such as changes in menstrual function, lower bone density, and estrogen deficiency disorders are the adverse effects of WP smoking in females that require more dedicated attention.[13] The results of studies in Middle Eastern societies show that it was particularly more acceptable for females to smoke WPs compared to cigarettes. The majority perceive WP smoking as less addictive than cigarette smoking.[14] In another study in San Diego County, it was discovered that students believed that WP smoking is less harmful than cigarette smoking because there is little or no nicotine, there are fewer chemicals, and water filters the smoke.[15]

The presence of charcoal and certain toxins that are produced by the WP in higher levels compared with cigarettes is also another risk factor, and it is worth highlighting that, in a single WP session, the amount of smoke inhaled can reach up to 150 times that of a single cigarette.[16]

Given the fact that WP smoking is the most common form of tobacco use among female students and the importance of identifying the factors influencing its pattern of use among females, there is a need to conduct studies focusing on WP smoking in females. The results of such studies can help in the improvement of preventive strategies to curb smoking using WPs in females. The purpose of this study is to investigate the prevalence of WP smoking and its associated risk factors among female adolescents in Western Iran.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

A total of 1302 participants were recruited for the study. They participated through stage random sampling from 12 schools in three districts of the city of Kermanshah from grades 7–12 from each school.

Initially, a list of schools in the three districts of Kermanshah was prepared. In total, 12 schools were then selected by random sampling (two middle schools and two high schools). At the school level, random sampling was also selected based on the number of students and the proportion of the total sample size.

Study participants and sampling

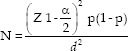

To estimate the sample size using the following formula, considering prevalence equal to 34.4%, and considering the acceptable error in the difference between estimating the prevalence of WP smoking with the actual prevalence, 0.3 was considered and by applying a double cluster sampling coefficient, the sample size was estimated to be 1302 people.

Data collection tool and technique

The data collection tool was a researcher-made questionnaire that was designed by a comprehensive review of research, literature, and the results of qualitative studies. The questionnaire consisted of the following two parts:

Demographic factors: Age, grade, father's and mother's occupation, father's and mother's education, living conditions, and family size

WP smoking-related behaviors: Never having been a former or current WP smoker, age when starting WP smoking, having fathers and mothers who smoke WPs (Yes/No), having brothers and sisters who smoke WPs (Yes/No), having friends who smoke WPs (Yes/No), and having friends who encourage WP smoking (Yes/No).

According to the answers to the above questions, which include Yes and No, scoring was done quantitatively and if the answer was Yes, one score was given and if the answer was No, it was given zero score.

The formal and content validity of the questionnaire was assessed using the opinion of 15 health education and promotion specialists. The content validity ratio and content validity index for each question were extracted and the questions were reviewed and corrected by considering the values of the Lawshe table.[17] Also, for the reliability of the questionnaire, in a preliminary study, the questionnaire was given to thirty students who had characteristics similar to that of the main study samples. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was then calculated.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from 16-year-old students and older students. Written informed consent was also obtained from parents of students under the age of 16. The names of the participants were not recorded in the questionnaire and other information was kept confidential and was used only in this study. The Ethical Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (reference number: IR.UMSHA.REC.1397.696).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (ver. 22 (Chicago, IL, USA). A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered. Statistical tests included descriptive statistics and logistic regression analyses.

Results

In this study, the students’ ages ranged from 12 to 18 years with a mean of 15.22 ± 1.85. The first place to start WP smoking was reported at a friend's home. More details of demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study participants (n=1302)

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 12 | 107 (8.2) |

| 13 | 179 (13.7) | |

| 14 | 191 (14.7) | |

| 15 | 229 (17.6) | |

| 16 | 219 (16.8) | |

| 17 | 198 (15.2) | |

| 18 | 179 (13.7) | |

| Grade | 7th | 191 (14.7) |

| 8th | 234 (18) | |

| 9th | 223 (17.1) | |

| 10th | 209 (16.1) | |

| 11th | 218 (16.7) | |

| 12th | 227 (18.4) | |

| Father’s education | Illiteracy | 65 (5.00) |

| Under diploma | 285 (21.9) | |

| Diploma | 649 (49.8) | |

| College | 303 (23.3) | |

| Mother’s education | Illiteracy | 75 (5.8) |

| Under diploma | 485 (37.3) | |

| Diploma | 608 (46.7) | |

| College | 134 (10.3) | |

| Father’s occupation | Unemployed | 215 (16.5) |

| Self-employed | 691 (53.1) | |

| Employee | 396 (30.4) | |

| Mother’s occupation | Homemaker | 1201 (92.2) |

| Employed | 101 (7.8) | |

| Living (with) | Both parents | 1202 (92.3) |

| Others | 100 (7.7) |

According to WP smoking behaviors, 883 (67.8%) were never WP smokers, 419 (32.2%) were former WP smokers, and 265 (20.4%) were current WP smokers. The mean (standard deviation) age at WP smoking initiation was 13.65 ± 1.65 years [Table 2].

Table 2.

Factors associated with hookah smoking

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| WP smoking | Never | 883 (67.8) |

| Former | 419 (33.2) | |

| Current | 265 (20.4) | |

| WP smoking by father | Yes | 414 (31.8) |

| No | 888 (68.2) | |

| WP smoking by mother | Yes | 180 (13.8.) |

| No | 1122 (862) | |

| WP smoking by sibling | Yes | 356 (27.3) |

| No | 946 (72.7) | |

| WP smoking by friends | Yes | 856 (65.8) |

| No | 445 (34.2) | |

| The first place where WP smoking started (former) | Home | 122 (29.2) |

| Friends’ home | 192 (45.8) | |

| Park | 39 (9.4) | |

| Café | 61 (14.6) | |

| How to get to know WP for the first time (former) | Only self | 25 (5.7) |

| Friend | 199 (47.4) | |

| Family | 149 (35) | |

| Relatives | 46 (10.7) |

WP=Water pipe

The findings of Table 3 show that the level of fathers’ education was significantly related to WP smoking in such a way that, the likelihood of an increase in WP smoking in students whose parents were illiterate/below the level of diploma/diploma was 1.95, 1.81, and 1.37 times, respectively, more likely than those whose father had an academic education (P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis - The relationship between demographic variables and water pipe smoking

| Characteristics | Never WP smoking (n=883) (%) | Former WP smoking (n=419) (%) | AOR (95% CI) | P | Past-month WP smoking (n=265), n (%) | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | |||||||

| 12-13 | 200 (15.3) | 86 (6.6) | 0.94 (0.069-1028) | 0.7 | 53 (20) | 1.05 (0.73-1.5) | 0.7 |

| 14-15 | 273 (20.9) | 147 (11.2) | 1.18 (0.91-1.5) | 0.2 | 106 (40) | 1.5 (1.15-2.1) | 0.04** |

| 16-18b | 410 (31.5) | 186 (14.3) | 1 | - | 106 (40) | 1 | - |

| High school grade | |||||||

| 7th | 137 (10.6) | 54 (4.1) | 0.69 (0.46-1.04) | 0.08 | 31 (11.7) | 0.74 (0.45-1.2) | 0.24 |

| 8th | 168 (12.1) | 66 (5.1) | 0.88 (0.69-1.28) | 0.5 | 48 (18.1) | 0.98 (0.62-1.5) | 0.95 |

| 9th | 126 (9.7) | 97 (7.45) | 0.75 (0.51-1.1) | 0.1 | 68 (25.6) | 1.68 (1.09-2.5) | 0.01* |

| 10th | 164 (12.6) | 45 (3.4) | 0.56 (0.31-0.84) | 0.006*** | 33 (12.4) | 0.71 (0.43-1.17) | 0.945 |

| 11th | 154 (12.4) | 64 (5) | 0.55 (0.35-0.87) | 0.004*** | 38 (14.3) | 0.82 (0.5-1.31) | 0.673 |

| 12thb | 134 (10.5) | 93 (7.1) | 1 | - | 47 (17.8) | 1 | - |

| Father’s education | |||||||

| Illiteracy | 39 (2.1) | 26 (2.00) | 1.95 (3.4 - 1.1) | 0.01* | 16 (6.4) | 1.37 (0.73-2.50) | 0.3 |

| Under diploma | 176 (13.6) | 109 (8.5 | 1.81 (1.27-2.50) | 0.001*** | 72 (27.1) | 1.40 (0.96-2.1) | 0.07 |

| Diploma | 442 (34.0) | 207 (15.9) | 1.37 (1.01-1.84) | 0.04* | 119 (45) | 0.71 (0.66-1.33) | 0.73 |

| Collegeb | 226 (17.4) | 77 (6.0) | 1 | - | 58 (21.9) | 1 | - |

| Mother’s education | |||||||

| Illiteracy | 55 (4.2) | 20 (1.5) | 0.78 (0.4-1.4) | 0.4 | 12 (4.5) | 0.60 (0.29-1.26) | 0.1 |

| Under diploma | 326 (25) | 159 (12.2) | 1.03 (0.68-1.55) | 0.83 | 97 (12.7) | 0.79 (0.51-1.25) | 0.32 |

| Diploma | 411 (31.5) | 197 (15.2) | 1.01 (0.68-1.54) | 0.94 | 124 (46.8) | 0.81 (0.52-1.27) | 0.37 |

| Collegeb | 91 (7.0) | 43 (3.3) | 1 | - | 32 (12.1) | 1 | - |

| Father’s occupation | |||||||

| Unemployed | 489 (37.5) | 288 (22.12) | 3.23 (4.3 - 2.3) | 0.001*** | 184 (69.5) | 2.62 (1.7-3.6) | <0.001*** |

| Self-employed | 114 (8.8) | 80 (6.3) | 3.85 (2.52-5.81) | 0.001*** | 46 (17.4) | 1.48 (1.63-4.21) | <0.001*** |

| Employeeb | 280 (21.5) | 51 (4.00) | 1 | - | 35 (13.1) | 1 | - |

| Mother’s occupation | |||||||

| Homemakerb | 819 (33.8) | 382 (33.7) | 1 | - | 234 (24.4) | 1 | - |

| Employed | 64 (3.4) | 37 (2.7) | 1.23 (0.81-1.81) | 0.31 | 31 (1.9) | 1.83 (1.17-2.86) | 0.008** |

| Family size | |||||||

| 2-4 | 71 (5.5) | 68 (5.3) | 2.67 (1.4-4.6) | 0.001** | 46 (17.3) | 1.88 (1.00-3.5) | 0.06 |

| 5-7 | 753 (57.9) | 328 (25.2) | 1.1 (67-1.64) | 0.6 | 200 (75.5) | 0.87 (47-1.3) | 0.4 |

| 8-10b | 59 (4.6) | 23 (1.8) | 1 | 18 (6.8) | 1 | ||

| Living (with) | |||||||

| Others | 58 (4.1) | 42 (3.1) | 1.58 (1.04-2.40) | 0.03* | 30 (1.6) | 1.76 (1.12-2.76) | 0.014* |

| Both parentsb | 825 (63.2) | 377 (29.6) | 1 | 235 (24.7) | 1 | - |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, bReference. CI=Confidence interval, AOR=Adjusted odds ratio, WP=Water pipe

Furthermore, the likelihood of an increase in WP smoking in students whose fathers were self-employed (adjusted odds ratios [AORs] =3.85; 95% [confidence interval] [CI] [2.52–5.87]) and unemployed (AORs = 3.23; 95% CI [2.3, 4.3]) was 3.85 and 3.23 times, respectively, more likely than those whose fathers were employees.

Table 4 shows that having friends who smoke using WPs (AORs = 4.96.55; 95% CI [3.86, 6.38]), having WP-smoking fathers (AORs = 4.12; 95% CI [3.02, 5.2]), having WP-smoking mothers (AORs = 4.49; 95% CI [3.23, 6.45]), and having WP-smoking brothers and sisters (AORs = 4.81; 95% CI [3.07, 5.21]) were significant variables in relation to former and current WP smoking.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis - Water pipe smoking and behavioral risk factors

| Characteristics | Never WP smoking (n=813), n (%) | Former WP smoking (n=409), n (%) | AOR (95% CI) | P | Current WP smoking (n=265), n (%) | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP user friends | |||||||

| Nob | 685 (52.4) | 172 (13.2) | 1.00 | - | 107 (40.3) | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | 198 (15.2) | 247 (19) | 4.96 (3.86-6.38) | <0.001*** | 158 (59.7) | 3.85 (2.19-5.1) | <0.001*** |

| WP user mother | |||||||

| Nob | 816 (86.2) | 306 (30.8) | 1.00 | - | 181 (18.4) | 1.00) | - |

| Yes | 67 (5.1) | 113 (5.6) | 4.49 (3.23-6.25) | <0.001*** | 84 (7.9) | 4.56 (3.26-6.34) | <0.001*** |

| WP user father | |||||||

| Nob | 692 (53.1) | 196 (15) | 1.00 | - | 121 (4507) | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | 191 (14.7) | 223 (17.12) | 4.12 (3.2-5.2) | <0.001*** | 144 (54.3) | 3.38 (2.55-4.46) | <0.001*** |

| WP user brother and sister | |||||||

| No | 734 (56.4) | 212 (16.3) | 1.00 | - | 120 (45.3) | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | 149 (11.5) | 207 (15.8) | 4.81 (3.71-6.23) | <0.001*** | 145 (54.7) | 4.73 (3.55-6.29) | <0.001*** |

| Suggest to use from friends | |||||||

| Nob | 791 (60.7) | 227 (17.5) | 1.00 | - | 138 (52) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 92 (7.06) | 192 (14.8) | 7.27 (5.41-9.70) | <0.001*** | 127 (48) | 5.81 (3.84-6.92) | <0.001*** |

| Insist from friends | |||||||

| Nob | 833 (64) | 311 (23.9) | 1.0 | - | 184 (69.5) | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | 50 (3.85) | 108 (8.3) | 5.75 (4.03-8.23) | <0.001*** | 81 (30.5) | 5.4 (3.86-7.78) | <0.001*** |

*P<0.05, **P< 0.01, ***P< 0.001 WP=Water pipe, CI=Confidence interval, AOR=Adjusted odds ratio, b: Reference

Discussion

The present study intended to determine the factors linked with the increase in WP smoking among female adolescents in Kermanshah. The findings of the study showed that 32.2% of females had at least once participated in WP smoking during their lifetime and 20.4% had smoked WPs in the past month.

Estimates of the prevalence of our study were similar to those of the study by Momtazi et al. and Maziak et al.[8,18] For example, Momtazi et al.[18] reported the prevalence of WP smoking in Iranian females (34.4%) and Maziak et al.[8] reported the prevalence of WP smoking among Iranian females to be 23% at the present time.

A study in Iran showed that the prevalence of WP smoking was 17.3%.[19] Moreover, in Zahedan, in the southeast of Iran, the incidence of WP smoking was reported as 21% among high school students.[20] However, the prevalence of WP smoking in the present study is higher than that of other studies,[19,20] which may be due to differences in sample size, easy access to WP, and demographic and geographical differences in the target population.

In the present study, the mean age of the initiation of WP smoking was 13/64 years old, while a study in China[21] also reported tobacco smoking after the age of 12. The results of the study were similar to that of study by Abedini et al. and Barati et al.[22,23] The setting of these studies was similar to the setting of the present study in schools and among high school students, which may be a reason for the similarity of the results of these studies with those of the present study.

The findings also showed that the probability of increasing WP smoking was in the age group of 14–15 years. Smith et al study showed that the prevalence of hookah smoking, especially water pipe in adolescents under age 18 is high.[15]

The presence of waterpipe in cafes and restaurants and access to it for people under the age of 18 years have made the cafe an attractive and motivating place and a cheap way for young people to spend time This may be due to the focus on marketing strategies and the lack of waterpipe law in public places.[13,24]

In this study, the results indicate that having a friend who smokes WPs increases the probability of WP smoking, similar to the results of a study.[13,25,26]

Studies have shown that the rate of smoking was 10 folds’ higher among students with friends who smoke or those with classmates who smoke compared to those who did not have such friends or classmates.[25] The findings showed that the influence and encouragement of peers to smoke WPs increased the probability of smoking WPs seven times more among students, which is similar to the result of the study by Marzban et al.[27] It seems that lack of sufficient people skills, such as the ability to say “no” to the suggestion of friends, is one of the main reasons for the tendency to smoke WPs. Almost 47% of students reported that their behavior of smoking WPs started with their friends. Also, studies by Alzyoud et al. and Mohammad-Poorasl et al. showed that friends had an important impact on WP smoking.[28,29]

In this study, having a parent and brother or sister who smoke WPs increases the probability of an increase in WP smoking among students, which is similar to the results of studies.[11,30] One of the reasons for the similarity of the results of these studies with those of the present study is the cultural acceptance of WP smoking in some societies such as Iran. In Iran, WP smoking is known as a normal behavior and WP is considered a tool for recreation and entertainment.

Most families do not allow Iranian women to Cigarette smoke, but When family members usually WP smoking for fun, Encourages Iranian women to smoke.

Research showed that the occupations and education of parents play a significant role in the increase of WP smoking, in such a way that, the probability of WP smoking in students whose fathers are unemployed and self-employed is more than that in students whose fathers are employees, which is similar to the result of a study.[31] Studies have also shown that there is a positive relationship between higher education and increased quality of life.[32]

Students whose mothers are employees were 1.83 times more likely to smoke than those whose mothers are homemakers, which is similar to the results of a study.[31,33]

The findings showed that father's level of education has a significant relationship with WP smoking to a larger extent that females whose fathers have a lower level of education are more likely to smoke WPs.[31,34] Being unemployed, lack of education, and low income are the important factors leading people to smoke tobacco.

In general, the findings showed that if family members smoke WP, it will increase the likelihood of smoking hookah, which is consistent with the results of other studies.[35] Bandura theory of social learning emphasizes interpersonal factors in explaining substance abuse. This theory holds that adolescents derive their beliefs about high-risk behaviors from role models, especially close friends and parents.[26,36]

Some women are still embarrassed about smoking WP in the presence of others, but their friends and family seem to be trying to help women relieve their shame. In Baheiraei et al.'s study,[37] male friends were identified as a strong factor in WP consumption. It is common among today's youth to meet their friends in traditional restaurants and boys order WP for women.

The findings showed that the probability of an increase in WP smoking in females who lived with one of their parents or someone other than a parent is more than that of students who live with their parents, which is similar to the results of the study.[33]

The findings show that there is a significant relationship between the number of family members and hookah smoking. This finding differed from the results of a study by Graham et al.[38] Graham et al.'s study showed that with each increase in family members, the tendency to smoke increases 1.63 times.

Graham et al.[38] examined the factors affecting smoking in women aged 16–49 years. Differences in the type of tobacco product and the target group could be the reason for the differences between the results of this study and that of the present study.

We can suppose that a reduction in the number of family members has increased the students’ desire to find and have friends outside of their homes, but it must not be neglected that their friends also have a significant impact on WP smoking.

Limitation and recommendation

One of the strengths of the present study was the study of the pattern of WP smoking in adolescent females and the identification of behavioral and demographic determinants related to it in the target population; also, due to the change in the pattern of smoking from homosexual to bisexual and the high prevalence of smoking in females, no study was found in Iran that only targeted adolescent females (12–18 years old) regarding WP smoking and in most studies, more attention has been paid to target groups such as adolescent boys and students. Therefore, this study was conducted for the first time among adolescent females regarding WP smoking in Kermanshah. One of the limitations of the present study was that this study was performed among school-going adolescents. It is obvious that conducting a study among females who have dropped out of school can be a more accurate estimate of the behavior of WP smoking among Iranian adolescents, therefore attention to the above points is suggested in future studies.

Conclusions

The prevalence rate of WP smoking is notable among female students in Kermanshah. Our results showed that friends’ behavior of WP smoking played a key role in WP smoking among female adolescents. There is a need to design interventional studies to increase people's skills and teach the art of saying “no” and standing one's ground when facing peers who encourage others to smoke and furthermore, increase students', friends', and parents’ knowledge about the harms of WP smoking.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences in Iran, and the funder did not play a role in research design, data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing (reference number: 9711026633).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the students who participated in this study and also the Kermanshah Department of Education.

References

- 1.Menezes AM, Wehrmeister FC, Horta BL, Szwarcwald CL, Vieira ML, Malta DC. Frequency of the use of hookah among adults and its distribution according to sociodemographic characteristics, urban or rural area and federative units: National Health Survey, 2013. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2015;18(Suppl 2):57–67. doi: 10.1590/1980-5497201500060006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdelwahab S. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2019. Characterizing the Effect of New and Emerging Tobacco Products on Airway Innate Mucosal Defense (Doctoral dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) p. 13858677. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fromme H, Schober W. The waterpipe (shisha) – Indoor air quality, human biomonitoring, and health effects. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59:1593–604. doi: 10.1007/s00103-016-2462-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sureda X, Fernández E, López MJ, Nebot M. Secondhand tobacco smoke exposure in open and semi-open settings: A systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:766–73. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bashirian S, Barati M, Sharma M, Abasi H, Karami M. Water pipe smoking reduction in the male adolescent students: An educational intervention using multi-theory model. J Res Health Sci. 2019;19:e00438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karimi N, Saadat-Gharin S, Tol A, Sadeghi R, Yaseri M, Mohebbi B. A problem-based learning health literacy intervention program on improving health-promoting behaviors among girl students. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:251. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_476_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzammil, Al Asmari DS, Al Rethaiaa AS, Al Mutairi AS, Al Rashidi TH, Al Rasheedi HA, et al. Prevalence and perception of shisha smoking among university students: A cross-sectional study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2019;9:275–81. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_407_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maziak W, Taleb ZB, Bahelah R, Islam F, Jaber R, Auf R, et al. The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tob Control. 2015;24(Suppl 1):i3–12. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meysamie A, Ghaletaki R, Haghazali M, Asgari F, Rashidi A, Khalilzadeh O, et al. Pattern of tobacco use among the Iranian adult population: Results of the national Survey of Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases (SuRFNCD-2007) Tob Control. 2010;19:125–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erdöl C, Ergüder T, Morton J, Palipudi K, Gupta P, Asma S. Waterpipe tobacco smoking in turkey: Policy implications and trends from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey (GATS) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:15559–66. doi: 10.3390/ijerph121215004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sighaldeh SS, Baheiraei A, Dehghan S, Charkazi A. Persistent use of hookah smoking among Iranian women: A qualitative study. Tob Prev Cessat. 2018;4:38. doi: 10.18332/tpc/99507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salameh P, Khayat G, Waked M. Lower prevalence of cigarette and waterpipe smoking, but a higher risk of waterpipe dependence in Lebanese adult women than in men. Women Health. 2012;52:135–50. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2012.656885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bashirian S, Barati M, Karami M, Hamzeh B, Ezati E. Predictors of shisha smoking among adolescent females in Western Iran in 2019: Using the prototype-willingness model. Tob Prev Cessat. 2020;6:50. doi: 10.18332/tpc/125357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akl EA, Jawad M, Lam WY, Co CN, Obeid R, Irani J. Motives, beliefs and attitudes towards waterpipe tobacco smoking: A systematic review. Harm Reduct J. 2013;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith JR, Novotny TE, Edland SD, Hofstetter CR, Lindsay SP, Al-Delaimy WK. Determinants of hookah use among high school students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:565–72. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qasim H, Alarabi AB, Alzoubi KH, Karim ZA, Alshbool FZ, Khasawneh FT. The effects of hookah/waterpipe smoking on general health and the cardiovascular system. Environ Health Prev Med. 2019;24:58. doi: 10.1186/s12199-019-0811-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28:563–75. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Momtazi S, Rawson RA. Substance abuse among Iranian high school students. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:221. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328338630d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karimy M, Niknami S, Heidarnia AR, Hajizadeh E, Shamsi M. Refusal self efficacy, self esteem, smoking refusal skills and water pipe (Hookah) smoking among Iranian male adolescents. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:7283–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.12.7283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakhshani N, Dahmardei M, Shahraki-Sanavi F, Hosseinbor M, Ansari-Moghaddam A. Substance Abuse Among High School Students in Zahedan, Health Scope? 2014;3:e14805. doi: 10.17795/jhealthscope-14805. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Q, Yu B, Chen X, Varma DS, Li J, Zhao J, et al. Patterns of smoking initiation during adolescence and young adulthood in South-West China: Findings of the National Nutrition and Health Survey (2010-2012) BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019424. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abedini S, MorowatiSharifabad M, Chaleshgar Kordasiabi M, Ghanbarnejad A. Predictors of non-hookah smoking among high-school students based on prototype/willingness model. Health Promot Perspect. 2014;4:46–53. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2014.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barati M, Allahverdipour H, Hidarnia A, Niknami S. Predicting tobacco smoking among male adolescents in Hamadan City, west of Iran in 2014: An application of the prototype willingness model. J Res Health Sci. 2015;15:113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anand NP, Vishal K, Anand NU, Sushma K, Nupur N. Hookah use among high school children in an Indian city. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2013;31:180–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.117980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeihooni AK, Khiyali Z, Kashfi SM, Kashfi SH, Zakeri M, Amirkhani M. Knowledge and attitudes of university students towards hookah smoking in Fasa, Iran? Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2018;12:e11676. doi: 10.5812/ijpbs.11676. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bashirian S, Barati M, Karami M, Hamzeh B, Ezati E. Effectiveness of e-learning program in preventing WP smoking in adolescent females in west of Iran by applying prototype-willingness model: A randomized controlled trial. J Res Health Sci. 2020;20:e00497. doi: 10.34172/jrhs.2020.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marzban A, Ayasi M. Prevalence of high risk behaviors in high school students of Qom, 2016. JMJ. 2018;16:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alzyoud S, Weglicki LS, Kheirallah KA, Haddad L, Alhawamdeh KA. Waterpipe smoking among middle and high school Jordanian students: Patterns and predictors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:7068–82. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10127068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadpoorasl A, Ghahramanloo AA, Allahverdipour H, Augner C. Substance abuse in relation to religiosity and familial support in Iranian college students. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;9:41–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bashirian S, Barati M, Abasi H, Sharma M, Karami M. The role of sociodemographic factors associated with waterpipe smoking among male adolescents in western Iran: A cross-sectional study. Tob Induc Dis. 2018;16:29. doi: 10.18332/tid/91601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meysamie AM, Seddigh L. Frequency of tobacco use among students in Tehran city. Tehran Univ Med J TUMS Publ. 2015;73:515–26. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babazadeh T, Taghdisi M, Sherizadeh Y, Mahmoodi H, Ezzati E, Rezakhanimoghaddam H, et al. The survey of health-related quality of life and its effective factors on the intercity bus drivers of the west terminal of Tehran in 2015. Community Health J. 2017;9:19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezaei FN, Mansourian M, Safari O, Jahangiry L. The role of social and familial factors as predicting factors related to hookah and cigarette smoking among adolescents in Jahrom, south of Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2017;5:4929–37. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao T, Sung HY, Mao Z, Hu TW, Max W. Secondhand smoke exposure at home in rural China. In: Economics of Tobacco Control in China: From Policy Research to Practice. Published in Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9900-6. DOI: 10.1007/s10552-012-9900-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joveyni HD, Gohari MR. The survey of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control of college students about hookah smoking cessation. Health System Research. 2012;7:1321–11. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mirzaei Alavijeh M, Jalilian F, Movahed E, Mazloomy S, Zinat Motlagh F, Hatamzadeh N. Predictors of drug abuse among students with application of Prototype/Willingness Model. J Police Med. 2013;2:111–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baheiraei A, Shahbazi Sighaldeh S, Ebadi A, Kelishadi R, Majdzadeh R. Factors that contribute in the first hookah smoking trial by women: A qualitative study from Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:100–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graham H, Der G. Patterns and predictors of tobacco consumption among women. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:611–8. doi: 10.1093/her/14.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]