To the Editor,

Cardiac involvement has been widely described during the acute phase of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. However, many patients report persistent symptoms after recovery, a condition known as persistent or long-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) syndrome. In some series, chest pain has been described in ∼20% of patients with long-COVID-19 syndrome,1 but the mechanisms for these symptoms have not been adequately explored. Some of these patients have angina-like chest pain. Adenosine stress perfusion cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is a useful noninvasive diagnostic tool for assessing myocardial perfusion and distinguishing epicardial from microvascular impairment according to perfusion patterns.2 CMR could play a role in the evaluation of this syndrome.3

We are currently performing a prospective observational study of patients with angina-like persistent chest pain after COVID-19 infection evaluated in a multidisciplinary referral long-COVID-19 outpatient clinic unit. After a first evaluation, thoracic computed tomography (CT) is performed to rule out pulmonary thromboembolism. Then, patients are referred to the cardiologist in the long COVID-19 unit and adenosine stress perfusion CMR and a coronary cardiac CT are performed if symptoms suggest angina and there are no clinical contraindications.

This study (ANGI-Covid) is being performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the local ethics committee of Hospital Universitari Germans Trias I Pujol (Badalona, Barcelona, Spain). All participants provided written informed consent.

Of a total cohort of 186 patients initially evaluated in the long COVID-19 unit, 51 (27%) had persistent chest pain. After the initial clinical evaluation, if the patients had chest pain on exertion and alternative diagnoses were ruled out, they were referred to the cardio COVID-19 unit.

Due to clinical relevance, we show the results of the first 10 consecutive patients who underwent adenosine stress perfusion CMR. These patients were mainly middle-aged (44.6 ± 8.0 years) women (80%) with a mild to moderate form of COVID-19 disease and without previous cardiovascular conditions or chest pain before COVID-19 infection (table 1 ). The median time from acute infection to symptoms was 23 [IQR 3-45] days and the mean time from infection to stress perfusion CMR was 8.2 [IQR 3.2-11.4] months. Stress perfusion CMR showed normal biventricular volume and function in all patients. No myocardial edema was detected, with normal myocardial T1 and T2 mapping values. No pericardial effusion was noted in any of the patients. Two patients showed myocarditis-like late gadolinium enhancement. There were no findings of an ischemic pattern or pericardial enhancement. First-pass stress perfusion CMR showed a significant circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect in 5 patients (50%), highly suggestive of microvascular dysfunction (figure 1 ). In all patients, epicardial artery disease was ruled out by coronary CT angiography.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics and stress perfusion CMR findings

| COVID-19 severity* |

Age/sex | Past medical Hx | Recent Hx/COVID-19 infection/ Chest pain |

Interval to CMR (mo) |

Stress perfusion CMR findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | 43 F | Exsmoker | Mild COVID-19 (fever, myalgias, anosmia). On day 4, onset of daily chest pain, worsening on exertion, highly suggestive of angina persisting at the 1-mo visit | 2.5 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - No LGE - Significant circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect from base to apex - Reproducible clinical angina during stress |

| 58 F | DLP, HTN, smoker | Mild COVID-19 (cough, flu-like). 7 days after a positive PCR, onset of chest pain suggestive of angina (on exertion) |

3.1 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - No LGE - Significant circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect from base to apex - Reproducible clinical angina during stress |

|

| 43 F | Exsmoker | Mild COVID-19 (fever, flu-like) Cyclic long COVID-19 symptoms including chest pain |

3.2 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - LGE: localized intramiocardial inferoseptal enhancement (myocarditis-Like) - Circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect from mid to apex - Reproducible clinical chest pain during stress |

|

| 42 F | None | Mild COVID-19 (flu-like) 1-mo later, cyclic persistent chest pain worsening on exertion |

11.4 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - No LGE - Circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect from base to apex - Reproducible clinical chest pain during stress |

|

| 46 F | HTN, DLP | Mild COVID-19 (flu-like) Neurocognitive long COVID-19 and sporadic episodic chest pain |

11.4 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - No LGE - Localized lateral subendocardial perfusion defect - No symptoms during stress |

|

| 27 F | None | Mild COVID-19 infection. Persistent symptoms including sinus tachycardia and persistent chest pain on exertion starting 5 d after infection |

11.8 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - LGE: No enhancement - No inducible perfusion defects - No symptoms during stress |

|

| Moderate | 41 F | None | COVID-19 pneumonia (hospital admission, no ICU) Pericarditis-like chest pain not improving with NSAIDs or corticoids. Ongoing symptoms worsening on exertion |

4.7 | Normal volumes and function. No pericardial effusion. - No edema - No LGE - Significant circumferential subendocardial perfusion defect from base to apex - Reproducible clinical chest pain during stress |

| 53 M | Exsmoker | COVID-19 pneumonia (admitted to hospital without ICU) Chest pain 2 mo after COVID-19 infection with PTE on CT 4 mo after COVID-19, persistent chest pain without PTE on CT |

10.9 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - LGE: Basal inferior and lateral subepicardial enhancement (myocarditis-like) - No inducible perfusion defects - No symptoms during stress |

|

| 40 M | HTN, DLP, obesity, atrial fibrillation | COVID-19 pneumonia (admitted to hospital without ICU) 2 mo later, oppressive chest pain on exertion suggestive of angina |

11.2 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - LGE: No enhancement - No inducible perfusion defects - No symptoms during stress |

|

| 52 F | None | COVID-19 pneumonia (admitted to hospital without ICU) Long COVID-19 symptoms including persistent ongoing chest pain |

12.2 | - Normal volumes and function - No edema - LGE: No enhancement - No inducible perfusion defects - No symptoms during stress |

CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; CT, computed tomography; DLP, dyslipemia; F, female; HTN, hypertension Hx, history; ICU, intensive care unit; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; M, male; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism.

WHO severity definitions (COVID-19 Clinical management: living guidance, 25 January 2021).

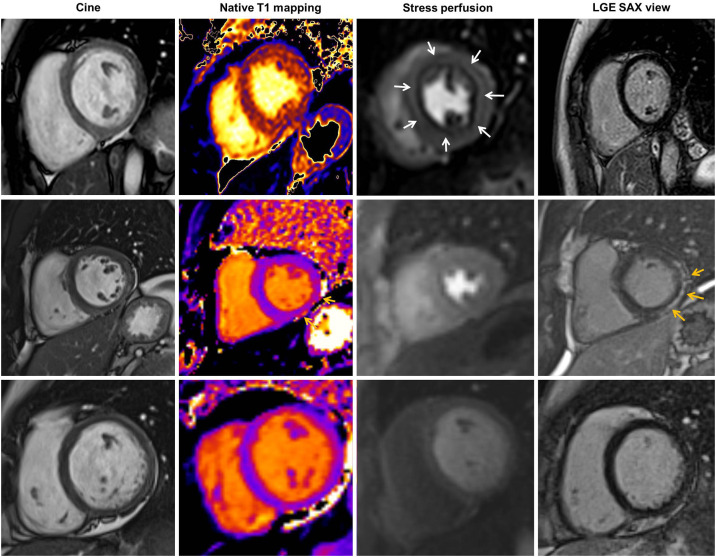

Figure 1.

Adenosine stress perfusion CMR findings in persistent chest pain in long COVID-19 syndrome: summary of CMR findings detected in adenosine stress perfusion CMR. First row: patient with normal LV volumes and function, normal T1 mapping, significant circumferential endocardial inducible perfusion defect in stress perfusion (white arrows) without late gadolinium enhancement. Second row: patient with normal LV volumes and function, normal T1 mapping, no inducible perfusion defect but myocarditis-like late gadolinium enhancement (yellow arrows). Third row: patient with normal CMR findings. CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance; LGE, late gadolinium enhancement; SAX, short axis view; LV, left ventricle.

Recent studies have reported a high incidence of cardiac lesions detected by CMR in patients who recovered from severe forms of COVID-19 infection and had a high incidence of previous cardiovascular disease or risk factors.4 However, long COVID-19 syndrome affects predominantly middle-aged women without cardiovascular risk factors and previous mild forms of COVID-19 disease.1, 4 In our study, 27% of our patient evaluated in a long COVID-19 unit had chest pain, some of them suggestive of angina after careful evaluation and after exclusion of other conditions. The pathological mechanism underlying this condition is still unknown. One explanation could be microvascular dysfunction. Half of our initial patients showed a microvascular dysfunction pattern on adenosine stress perfusion CMR. The mechanisms of microvascular disease in COVID-19 include endothelial injury via angiotensin converting-enzyme 2, with endothelial dysfunction and microvascular inflammation and thrombosis.5, 6

These first consecutive cases in this observational study strongly suggest that coronary microvascular ischemia is the underlying mechanism of angina-like persistent chest pain in patients who have recovered from COVID-19. As noted, the patients reported here are part of a broader study (ANGI-Covid) in which special CMR sequences for noninvasive quantification of myocardial perfusion and coronary flow reserve are also being studied and evaluated in these patients. Future work will have to elucidate the incidence and prevalence and compare these data with controls. However, at this point, we believe the results provided are of clinical importance.

Therapeutic strategies aiming to prevent or treat endothelial dysfunction in this scenario should be tested.

FUNDING

A. Bayés-Genís was supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness-MICINN (SAF2017-84324-C2-1-R; PID2019-110137RB-I00), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI17/01487, PIC18/00014, ICI19/00039, PI18/00256, PI18/01227, ICI20/00135), Red de Terapia Celular-TerCel (RD16/00111/0006), CIBER Cardiovascular (CB16/11/00403) projects as a part of the Plan Nacional de I+D+I, and it was cofunded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER), AGAUR (2017-SGR-483, 2019PROD00122), Fundació Bancària ’La Caixa (HR17-00627, CI20-00230), Sociedad Española de Cardiología, Societat Catalana de Cardiologia, and Institut Català de Salut (ICS). L. Mateu was supported by the crowdfunding campaign YoMeCorono (www.yomecorono.com)

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have made substantial contribution to the design of the work, acquisition and analysis of the results and have reviewed and approved the manuscript. N. Vallejo Camazón, L. Mateu, M.J. Martínez Membrive, and C. Llibre clinically evaluated and included patients in the study and analysis. A. Teis analyzed and performed stress perfusion CMR. L. Mateu, and A. Bayés-Genís made essential contribution in reviewing and drafting the manuscript and contributed equally to this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

.

References

- 1.Sudre C.H., Murray B., Varsavsky T., et al. Attributes and predictors of long COVID. Nat Med. 2021;4:626–631. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vancheri F., Longo G., Vancheri S., Henein M. Clinical Medicine Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2880. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vallejo N., Teis A., Mateu L., Bayés-Genís A. Persistent chest pain after recovery of COVID-19: microvascular disease-related angina? Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytab105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedrich M.G., Jr. LTC. What we (don’ t) know about myocardial injury after COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2021 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P., et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rozado J., Ayesta A., Morís C., Avanzas P. Physiopathology of cardiovascular disease in patients with COVID-19, Ischemia, thrombosis and heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol Supl. 2020;20(E):2–8. [Google Scholar]