Abstract

Introduction

Diagnostic Radiography plays a major role in the diagnosis and management of patients with Covid-19. This has seen an increase in the demand for imaging services, putting pressure on the workforce. Diagnostic radiographers, as with many other healthcare professions, have been on the frontline, dealing with an unprecedented situation. This research aimed to explore the experience of diagnostic radiographers working clinically during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Methods

Influenced by interpretative phenomenology, this study explored the experiences of diagnostic radiographers using virtual focus group interviews as a method of data collection.

Results

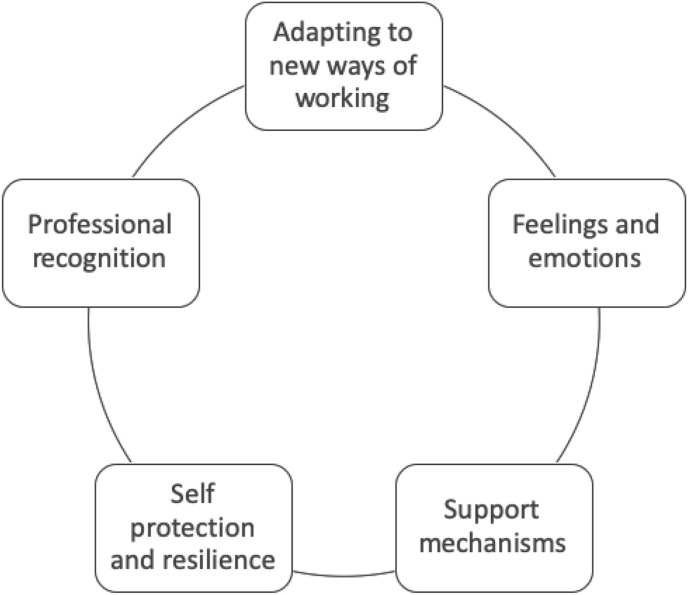

Data were analysed independently by four researchers and five themes emerged from the data. Adapting to new ways of working, feelings and emotions, support mechanisms, self-protection and resilience, and professional recognition.

Conclusion

The adaptability of radiographers came across strongly in this study. Anxieties attributed to the provision of personal protective equipment (PPE), fear of contracting the virus and spreading it to family members were evident. The resilience of radiographers working throughout this pandemic came across strongly throughout this study. A significant factor for coping has been peer support from colleagues within the workplace. The study highlighted the lack of understanding of the role of the radiographer and how the profession is perceived by other health care professionals.

Implications for practice

This study highlights the importance of interprofessional working and that further work is required in the promotion of the profession.

Keywords: Covid-19, Interprofessional working, Professional identity, Radiography

Introduction

In December 2019 the World Health Organisation was notified regarding cases of pneumonia with unknown aetiology in Wuhan City.1 A rapid global spread of the disease lead to the declaration of a pandemic known as Covid-19. On 13th March 2020, the World Health Organisation declared that Europe was at the centre of a pandemic and as of 14th October 2021, there have been 238,521,855 cases worldwide (of which 8,231,441 cases were in the United Kingdom (UK) and 4,863,818 deaths (of which 137,944 were in the UK).1 Due to the continuous discovery and resurgence of new variants, the pandemic continues to challenge even the most well-established healthcare systems.1

From the onset, it was quickly established that chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest have played a significant role in the diagnosis and management of patients presenting with Covid-19.2, 3, 4 This has resulted in the demand for imaging services being increased, as the National Health Service (NHS) has faced increasing pressure to respond to the pandemic and the needs of the UK population.5 Diagnostic radiographers across the UK have been on the frontline, dealing with an unprecedented situation in which there have been large volumes of very unwell patients who have needed repeated imaging to effectively manage their complex needs in an attempt to aid recovery.

There was much uncertainty around the nature and spread of the virus leading to concern about the impact on the health service. A multinational study exploring physical symptoms among healthcare workers during the Covid-19 outbreak found that headaches were the most commonly reported, suggesting this is associated with personal protective equipment (PPE).6 Migraines were also reported, possibly related to increased adverse psychological experiences which healthcare workers may need support for.6 There were also reports of lethargy and fatigue. A UK-based study exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the pandemic using interviews as a method of data collection found a lack of preparedness for the pandemic with no clear strategic policy.7 Participants expressed a severe shortage of PPE, feelings of anxiety and fear, challenges of enforcing social distancing, and social shielding responsibility for family members.7 Hospital personnel may be stressed by the challenges of prolonged response to the pandemic.8 This emphasises the importance of self-care, ensuring workers have adequate rest and can attend to personal needs such as the care of a family member.8 It was also suggested that health workers dealing with the situation may experience moral injury or mental health problems.9 Moral injury can occur when exposed to trauma that a person feels unprepared for, stressing the need for preparing and supporting staff for encountering moral dilemmas they may face during the pandemic. They also raise the issue of after-care once the crisis is over, and the need for supervision.9 The Society of Radiographers10 recognise the need to support the well-being, emotional and mental health of radiographers, recognising that with the increased demands on imaging services staff may experience significant stress and anxiety. Despite these challenges, an editorial in the Lancet identified that health care workers have shown an incredible commitment and have demonstrated compassion in these challenging and dangerous conditions.11 This research aimed to explore the experience of diagnostic radiographers working clinically during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Method

The overarching approach to this research was influenced by interpretative phenomenology. It explored individual's lived experience and how they made sense of that experience.12 The ideographic nature of the research meant that it involved a small number of participants focussing on each case in detail, aiming to gain understanding from that experience.12 It is thought that by probing deeply into participant's accounts, general themes that are common to others can be illuminated or affirmed.13 In keeping with this qualitative methodology, focus group interviews using a semi-structured interview schedule (Table 1 ) were used as the primary source of data collection.14

Table 1.

Focus group interview questions.

|

Please will you describe your experiences of working as a radiographer at the start of the pandemic? How does this differ today? Please describe how the pandemic impacted on your working conditions. Please describe anything that supports or helps you whilst working as a radiographer during the pandemic What recommendations do you have for a newly qualified radiographer just starting out in this environment? What suggestions have you for training or education to prepare students for working in the current clinical environment? |

Data were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and each researcher closely examined the data to identify patterns of meaning that came up repeatedly. The important factors considered when undertaking the analysis included double hermeneutics, reflexivity, immersion in the data, and the balance of emic and etic positions which was required as the researchers are all diagnostic radiographers. This was achieved through repeatedly reading the transcripts and becoming familiar with the content, followed by discussion between the researchers. The interpretive process is grounded in the participant's account of the experience in their own words.15 Stages of analysis included an initial review to look for patterns, or themes. These emerging common issues were then discussed to interpret the data and explore meaning.16 This reflective process aimed to reduce the influence of the researcher and maximise the validity of the findings. To establish the credibility of this study, different strategies were utilised, including member checking for respondent validation, peer-review between the researchers, reflexivity, a thoughtful self-awareness and by utilising the participants' accounts in the write-up.17 Purposive sampling was utilised. Diagnostic radiographers were recruited via an invitation on social media. A poster containing information about the study and who to contact was shared via the professional networking platforms of Twitter and Linkedin. Anyone who responded to the advert who met the criteria of working as diagnostic radiographers throughout the pandemic irrespective of their speciality was invited to a focus group interview. An information letter and consent form were sent for their consideration. Four focus group interviews across a period of two months were held using a virtual platform with between two and five participants. There was no coercion and participants were provided with an information sheet electronically to inform their decision on whether to participate. Written consent was obtained via email before the data collection. Ethical approval for the study was granted from the researcher's universities of Derby, Suffolk, and Salford. Quotes have been anonymised and limited demographical information has been provided to preserve the anonymity of the participants (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

The composition of the focus groups.

| Participant Identification | Focus group | Area | Focus group Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| DR1 | FG1 | South England | R1 and R2 |

| DR2 | FG1 | South England | R1 and R2 |

| DR3 | FG1 | Scotland | R1 and R2 |

| DR4 | FG2 | North England | R3 and R4 |

| DR5 | FG2 | South England | R3 and R4 |

| DR6 | FG2 | North England | R3 and R4 |

| DR7 | FG2 | South England | R3 and R4 |

| DR8 | FG2 | East England | R3 and R4 |

| DR9 | FG3 | East England | R1 and R4 |

| DR10 | FG3 | South England | R1 and R4 |

| DR11 | FG3 | South England | R1 and R4 |

| DR12 | FG4 | South England | R2 and R4 |

| DR13 | FG4 | South England | R2 and R4 |

Results

The focus group interviews were conducted throughout March and April 2021 and as such participants were able to reflect on their experiences from both the first wave (March–May 2020) and the second wave (Dec 2020–Feb 2021) of the Covid-19 pandemic. Participants included in this paper were working as diagnostic radiographers in the UK. Five themes emerged from the data. These can be seen in Fig. 1 .

Figure 1.

The experiences of the diagnostic radiographers emerging from the data.

Adapting to new ways of working

Participants described how departments had adopted new ways of working to help manage workload during the pandemic. In most cases in the first wave, clinics and elective cases were postponed and the radiographer's workload was predominantly Covid-19 related. However, during the second wave, there was an expectation for elective cases to continue and participants described increasing volumes of elective workload alongside rising Covid-19 cases.

“During the first pandemic … our department went into shutdown. So, we had no GPs come in, we had CT, our CT lists were down to, you know, ten patients a day maximum, … we had no mammo clinics running or anything so it felt like the department was at a standstill.” DR1

“During the second pandemic it felt like there was ten times more pressure than the first because we were now having to make up time, and we still are, for all those lost appointments, those emergency CTs, those mammograms.” DR1

“We really did get hit hard with the Covid patients this time round. So, to be able to keep some sort of service running has been miraculous.” DR9

Many departments implemented measures to support staff in managing the workload. Participants described adaptations to staff rosters to incorporate rest periods, extending staff working days, increasing the number of staff working night shifts, and where possible having increased numbers of staff undertaking mobile radiography.

“We were given about two weeks' notice that we're going from eight-hour days to 12-h days.” DR5

“We were lone working on nightshifts … they straight away said no, we don't think that's safe for you guys, we should have two people on again, so let's just start that. Create a whole new rota for the pandemic and make sure everyone's safe.” DR1

Participants whose roles included advanced practice reporting described a shift in their workload with a reduction in musculo-skeletal (MSK) workload and an increase in chest radiography reporting. Many described returning to work clinically or undertaking other roles to support departments.

“In terms of my Advanced Practice role, the A&E films dwindled … normally we'd be doing … maybe 60 or 80 from the previous night … and that just nosedived when we went into the first lockdown to maybe 20 patients.” DR14

“I didn't report for three months at all ….so all the skill kind of had to go on the back burner while I supported the rest of the team to image potentially really sick patients. My role completely switched. That was the biggest thing to deal with, the thing I love doing is reporting.” DR5

Feelings and emotions

During the first wave, many participants described a rollercoaster of emotions including feeling nervous, scared, and anxious. In the early stages of the pandemic, some of this anxiety was attributed to a fear of contracting the virus or passing it on to family members and loved ones.

“To me when we first started it felt like Ebola or something and it felt like oh my, if my PPE splits, I'm going to get Covid type thing, and it felt very scary.” DR4

“I've been in this job for 12 years now and I have to admit the first time I've ever felt anxious about going into work because I didn't know what I was walking into. I didn't have a clue.” DR7

“Quite anxious about what happens if you get Covid … just like really horrible feelings and being quite scared because you thought ‘what if my family get it’ and they come in.” DR13

The provision of PPE varied between participants with some reporting adequate supplies and others reporting a lack of PPE, particularly during the first wave.

“We were very, very, lucky, we've never once had a shortage of PPE or masks or anything in my hospital, so in that respect, it's been brilliant.” DR1

“By mid-April, we were running out of FFP3 masks. We were told to very carefully use them. And I was ‘is that very carefully or is it you know what are you telling me to do? Are you telling me not to wear them?’” DR7

“But it was, well radiographers can't really use – you're not supposed to use gowns in ITU because they're on their last box.” DR14

During the first wave, participants described protocols and processes changing by the day and in some cases by the hour which attributed to the anxiety felt by many. The rapidly changing information was particularly focused on the use of PPE.

“Every day it was ‘Oh you need to wear this PPE’, we were in full masks for a bit and then they changed it and we're like ‘well why are changing it?’ and then they're like ‘you only need to have them on in this area’ but that changed all the time. At one point we had theatre hats, that lasted about 10 minutes and then somebody came round and went ‘no you don't need those anymore’.” DR7

Changes of messaging regarding PPE, what the new protocols were …. . were coming out twice a day at some point.” DR6

“One minute you did one thing, sent out an email, told people what was happening, an hour later we were doing something different.” DR8

Following the second wave, participants reported feeling exhausted, fed up and described it feeling tedious. However, many described it as feeling more confident about when and where to utilise PPE and they acknowledged that supplies of PPE had improved.

“People are tired and fed up of how long it's been going on for.” DR13

“It's just felt like we know what we're doing this time, we know what we're dealing with. We know what PPE we should be wearing and when and we know how infectious it is and what's dangerous and what's safe.” DR8

During the second wave, many participants described their shock at the volume of patients affected, the age range of patients, and also the speed at which patients succumbed to the virus.

“I found that a little bit hard, thinking that, oh God, I X-rayed her or I CT'd her a while ago and now she's dead. I was more conscious of that in the second one than in the first one.” DR3

“Because of the way Covid works, people decline so quickly, when you start seeing that it really does affect you because it makes it very real. And especially when someone's fifty, sixty, still got everything ahead of them it really hits home.” DR1

“Especially during the second one I would say it became more prevalent, we were seeing younger and younger people which was much harder.” DR1

Support mechanisms

Participants were asked about support mechanisms that they had utilised during the pandemic. Many acknowledged the wider Trust initiatives implemented to support staff including regular updates, well-being applications, links to counselling, support, and mental health first aiders. Participants were aware of such initiatives but uptake appeared to be low due to shift patterns or logistical reasons preventing individuals from engaging.

“Trained first aiders, mental health first aiders. Twice weekly coronavirus updates from the Trust … quite a lot of initiatives recently with exercise and Teams meetings that you can join for Pilates classes.” DR12

“Obviously, most of us are busy working and can't take half an hour just to chat about how we feel really … it's hard for them to support us really in a way that suits everybody, but they have tried.” DR13

Many participants felt that departmental management support was lacking with managers working from home and not being present within the department. No participants reported any form of debrief taking place at any time over the duration of the pandemic.

“I can't say our management have been very present or terribly supportive to be honest …. .Most of them have worked from home … it wasn't I'm working from home and here's my phone number, it was I'm working from home, and you email me.” DR12

“They always put on the end of emails our door is always open, feel free to contact us if you have any issues or any concerns. But there's been no formal debrief or mention of any kind of meetings or one on one support in that respect.” DR1

The most significant response reported from participants was that support came from within the team itself. Particularly in the first wave of the pandemic, many spoke of high morale, team spirit, and colleagues looking after one another.

“There was very much a big team spirit. We were helping each other.” DR10

“It was the best camaraderie I've had in years because it was like going to war. It was ‘right come on guys here we go, come on we'll sort it out’ and I absolutely loved that, I really did.” DR5

“For us the staff morale was incredible. everyone really, really pulled together just because we didn't know what to expect. And it was very, very supportive environment trying to look after each other.” DR13

All participants described WhatsApp groups being established to communicate important information particularly regarding PPE. In addition to this, many acknowledged the role of WhatsApp for social interaction, light-hearted exchanges, and support.18

“We setup a WhatsApp group … as a means of urgent communication, PPE changes and that sort of thing but also we put jokes and other things in there.” DR5

“People put fun things on there as well … a bit of banter on there ….it felt like you were keeping in touch without being bombarded with the seriousness of emails, it felt more light hearted.” DR13

“I think the team spirit in our working group has prevailed. We've got the various WhatsApp groups and we're quite sociable.” DR11

Self-protection and resilience

In the early days of the pandemic particularly when PPE guidance was conflicting, many participants described making autonomous decisions around the use of PPE, often these decisions were contrary to departmental or Trust guidance. Participants felt this was necessary to protect themselves and others.

“If I went to ICU I would put scrubs on. We were told we didn't have to, that we shouldn't be doing because it's a waste of scrubs. But I always did because then I could leave there and then go to neonatal … wearing the same uniform. That just felt wrong, you know, really wrong. But we were told that's what we should be doing ….that was our managers saying that. But I just thought well I'm going to do what I think is right.” DR13

“We became masters of our own defence against covid ….So many different avenues of information, which one do you believe … basically the one that provided you with the most protection was the one we decided to follow ourselves.” DR3

The resilience of the radiology workforce was apparent through all of the focus group interviews. Participants recognised when they were beginning to feel uneasy and many took their own action to address how they were feeling.

“I stopped sleeping, I wasn't concentrating. I felt like really low at home and distant and I didn't want to play with my children or talk to my family or anything …. I uninstalled the news Apps on my phone, I stopped reading the news. I downloaded an App and started listening to meditation music, I tried to start reading books …..I've been trying to go to bed earlier and starting eating better.” DR8

“I've taken up reading novels, you know, just books, just because it's somewhere else to go.” DR10

Many participants recognised the need to build resilience and recommended this to undergraduate students and newly qualified staff entering the workforce.

“It's about resilience and being able to adapt for what's required of us at the time.” DR13

“I personally have faith that we can adapt and we've coped exceptionally well. And we've proven that we have still been able to carry on and provide a good service through such a challenging time.” DR9

Professional recognition

Many participants described professional challenges during the pandemic, particularly around the role of the radiographer and how it is perceived by fellow professionals. Initially, diagnostic radiographers were not considered as frontline workers particularly concerning the provision and use of PPE.

“Across the hospital it didn't seem to be we were acknowledged as frontline workers initially.” DR12

“We kept getting told, ‘oh well you don't need that, you are not going to be, you know within two metres of the patient’. But you know, you scan intubated patients, X-ray intubated patients, you go to theatre. DR2

“Oh, you're going in for five minutes, you don't need to bother putting FFP3 mask on. You're fine with a surgical mask. And you know sort of like downplaying, just because we're not in there for a huge amount of time in intensive care or CCU, that we don't need the same protection.” DR13

Participants described friction between radiology and other professions particularly around processes of managing Covid-19 within the department e.g. ventilating scan rooms and many felt this friction was due to other professions not fully understanding radiography processes.

“We're being obstructive, but we weren't it was just not understanding what we do.” DR2

“It wasn't within our own department, and it wasn't our own management and it just took a long time for people to understand why we were doing what we were doing.” DR7

Many attributed the lack of professional recognition to the insular nature of radiology.

“We're insular and behind closed doors, and people don't really know what goes on in our department.” DR13

“We may have been forgotten but we were present throughout the whole pandemic … yeah no one knows what we're doing here, no one has a clue, even the doctors and nurses don't seem to think we're part of the team. And it's a horrible feeling.” DR1

Discussion

The adaptability of radiographers came across strongly in this study as recognised by others.19The management of departments suspending services and reducing non- Covid-19 workload during the first wave is evident as in previous studies.20, 21, 22 There is little published research on the impact of the second wave. However, the reported increase of Covid-19 patients is supported by data released by the Office of National Statistics UK23 who reported an 81% increase in hospitalisations from the first wave (18,974) to the second wave (34,336). In response to this increased workload, the introduction of new ways of working in departments such as adjusting staffing levels out of hours appears to have been adopted by many departments.22 , 24 Changes in workplace organisation such as segregation of departments to minimise cross-infection are also noted as common practice.24

Anxieties attributed to the provision of PPE, fear of contracting the virus, and spreading it to family members was a common concern for healthcare workers during this pandemic.7 , 25, 26, 27 Reports of PPE provision varied across organisations with some participants reporting a lack of PPE, particularly in the first wave of the pandemic. Fluctuating guidance around the use of PPE is supported by other UK-based research.20 , 28 Anxiety around PPE subsided as confidence in its supply and use grew. However, other emotions such as shock and exhaustion increased during the second wave. The emotional toll of witnessing the impact of the disease on patients is highlighted in the work of Bennet et al.28 through the personal stories of 54 healthcare workers. Those stories also elicited a response of shock and upset at the effect of the virus and the age range of patients who were affected.

As found elsewhere, the resilience of radiographers working throughout this pandemic is evident.27 A significant factor for coping has been peer support from colleagues within the workplace. Reports of improved teamwork and camaraderie are evident in other bodies of work.28 , 29 The use of WhatsApp for peer support along with dissemination of information has also been adopted by radiographers in other studies.29 This study highlighted that radiographers had not been offered any form of debriefing by management teams over the duration of the pandemic, and this was also reported by Foley et al.22 who examined the experience of radiographers in Ireland. The role of psychological debriefing is debated with some advocating its use30 , 31 while others support the use of alternative interventions.32 Examining the value of debriefing for radiographers would be worthy of further research.

The study has highlighted the lack of understanding of the role of the radiographer and how the profession is perceived by other health care professionals.27 Although vital to modern health care, diagnostic radiographers enter a profession that is poorly understood by both the public and other health care professionals.33 , 34 Evans' vision identifies the key role radiographers have in service delivery.35 However, this does not appear to be understood by the wider health care workers and the promotion of radiography as a profession needs to continue. Lack of professional recognition leads to misunderstanding and conflict. The fight for professional recognition is hampered by feelings of subordination and the ‘just the radiographer’ syndrome which incites low self-esteem, inferiority complex, and apathy.36 , 37 There also appears to be a self-blame culture in diagnostic radiography where, out of concern for their reputation, radiographers take the blame for errors or poor service, such as keeping patients waiting.38 Professional recognition is hampered by many factors including hierarchy, culture, and lack of professional dialogue.39 Nursing literature recognises the need for a good working relationship between health professionals involved in mobile radiography which played a major role during the pandemic.40 This highlights the importance of interprofessional education and working as a professional identity is influenced by respect from patients and colleagues.41

Conclusion

This study explored the experiences of diagnostic radiographers through the Covid-19 pandemic. During this time chest radiographs and CT scans of the chest played a significant role in the diagnosis and management of patients. Through four focus group interviews, it was revealed that diagnostic radiographers needed to adapt quickly to constantly changing new ways of working including changes to shift patterns and organisation of the workload. The pandemic elicited a rollercoaster of strong emotions which changed throughout the first two waves. There was anxiety and conflict over the accessibility and use of PPE and shock at the sheer volume and condition of patients. Support was largely sought from peers facilitated in part by technology. Trust initiatives were appreciated but not often accessed. There appeared to be a lack of targeted support, particularly in the form of debriefing. The radiographers taking part in the study demonstrated their resilience and self-protection, becoming ‘masters of their own defence’. The long-recognised issue of a lack of professional recognition and understanding of the role of the radiographer came across strongly in this study and further work is required in the promotion of the profession.

Limitations

The purpose of this study was to explore experiences in depth and how the participant's perceived their experiences. The findings are thus intrinsically linked to this particular context and limit the transferability of the findings. However, the experiences discussed might resonate across the profession.

Conflicts of interest statement

None.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in part by the College of Radiographers Industrial Partnerships Scheme.

References

- 1.Organization WHO Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. 2021. https://www.who.int/ Available from:

- 2.Shao J.M., Ayuso S.A., Deerenberg E.B., Elhage S.A., Augenstein V., Heniford B.T. A systematic review of CT chest in COVID-19 diagnosis and its potential application in a surgical setting. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(9):993–1001. doi: 10.1111/codi.15252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwee T.C., Kwee R.M. Chest CT in COVID-19: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2020;40(7):1848–1865. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleverley J., Piper J., Jones M.M. The role of chest radiography in confirming covid-19 pneumonia. BMJ. 2020:370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association BM Pressure points in the NHS. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/pressures/pressure-points-in-the-nhs Available from:

- 6.Chew N.W., Lee G.K., Tan B.Y., Jing M., Goh Y., Ngiam N.J., et al. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nyashanu M., Pfende F., Ekpenyong M. Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK. J Interprof Care. 2020;34(5):655–661. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. Jama. 2020;323(15):1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg N., Docherty M., Gnanapragasam S., Wessely S. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radiographers So Wellbeing, emotional and mental heath support and resources. 2020. https://covid19.sor.org/wellbeing,-emotional-and-mental-health/support-and-resources/ Available from:

- 11.Lancet T. COVID-19: learning from experience. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30686-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J.A., Shinebourne P. American Psychological Association; 2012. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. Sage publications; 2017. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams P.C.S. Medical imaging and radiotherapy research: skills and strategy. Springer; 2020. Qualitative methods and analysis. [internet] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eatough V., Smith J.A. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. Sage Handb Qual Res Psychol. 2008;179:194. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liamputtong P. Oxford University Press Melbourne; 2010. Research methods in health: foundations for evidence-based practice. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Green J., Thorogood N. Sage; 2018. Qualitative methods for health research. [Google Scholar]

- 18.WhatsApp Simple secure relaible messaging. 2021. https://www.whatsapp.com/?lang=en Available from:

- 19.Akudjedu T.N., Mishio N.A., Elshami W., Culp M.P., Lawal O., Botwe B.O., et al. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical radiography practice: a systematic literature review and recommendations for future services planning. Radiography. 2021;27(4):1219–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akudjedu T.N., Lawal O., Sharma M., Elliott J., Stewart S., Gilleece T., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiography practice: findings from a UK radiography workforce survey. BJR| Open. 2020;2:20200023. doi: 10.1259/bjro.20200023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elshami W., Akudjedu T.N., Abuzaid M., David L.R., Tekin H.O., Cavli B., et al. The radiology workforce's response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Middle East, North Africa and India. Radiography. 2021;27(2):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foley S.J., O'Loughlin A., Creedon J. Early experiences of radiographers in Ireland during the COVID-19 crisis. Insights into Imaging. 2020;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00910-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics OfN Coronavirus (Covid-19) Latest data and analysis of coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK and its effect on the and society. 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases Available from:

- 24.Eastgate P., Neep M.J., Steffens T., Westerink A. COVID-19 Pandemic–considerations and challenges for the management of medical imaging departments in Queensland. J Med Radiat Sci. 2020;67(4):345–351. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruiz C., Llopis D., Roman A., Alfayate E., Herrera-Peco I. Spanish radiographers' concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic. Radiography. 2021;27(2):414–418. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan A., Sharma P. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on radiology: emotional wellbeing versus psychological burnout. Indian J Radiol Imag. 2021;31(Suppl 1):S11. doi: 10.4103/ijri.IJRI_579_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis S., Mulla F. Diagnostic radiographers' experience of COVID-19, gauteng South Africa. Radiography. 2021;27(2):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett P., Noble S., Johnston S., Jones D., Hunter R. COVID-19 confessions: a qualitative exploration of healthcare workers experiences of working with COVID-19. BMJ open. 2020;10(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang H.L., Chen R.C., Teo I., Chaudhry I., Heng A.L., Zhuang K.D., et al. A survey of anxiety and burnout in the radiology workforce of a tertiary hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncology. 2021;65(2):139–145. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.13152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walton M., Murray E., Christian M.D. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J: Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9(3):241–247. doi: 10.1177/2048872620922795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan S., Siddique R., Li H., Ali A., Shereen M.A., Bashir N., et al. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on psychological health. J Global Health. 2020;10(1) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.010331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Overmeire R. The myth of psychological debriefings during the corona pandemic. J Global Health. 2020;10(2) doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cowling C. A global overview of the changing roles of radiographers. Radiography. 2008;14:e28–e32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowling C. Global review of radiography. Radiography. 2013;19(2):90–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evans R. A new vision for radiography that must succeed. Imaging Ther Practice. 2020:1. November. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis S., Heard R., Robinson J., White K., Poulos A. The ethical commitment of Australian radiographers: does medical dominance create an influence? Radiography. 2008;14(2):90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yielder J., Davis M. Where radiographers fear to tread: resistance and apathy in radiography practice. Radiography. 2009;15(4):345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strudwick R.M., Mackay S.J., Hicks S. It's good to share. Imaging Ther Practice. 2013:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cowling C., Lawson C. Assessing the impact of country culture on the socio-cultural practice of radiography. Radiography. 2020;26(4):e223–e228. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bwanga O. What nurses need to know about mobile radiography. Br J Nurs. 2020;29(18):1064–1067. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2020.29.18.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harvey-Lloyd J., Stew G., Morris J. Under pressure. Synergy: Imaging Ther Pract. 2012:9–14. [Google Scholar]