Abstract

In this retrospective cohort analysis of Colorado birth certificate records from April to December 2015-2020, we demonstrate that Colorado birthing individuals experienced lower adjusted odds of preterm birth after issuance of coronavirus-19 “stay-at-home” orders. However, this positive birth outcome was experienced only by non-Hispanic white and Hispanic mothers.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus-19; NHB, Non-Hispanic black; NHW, Non-Hispanic white

In March 2020, Colorado Governor Jared Polis issued stay-at-home orders to curb transmission of the coronavirus-19 (COVID-19), limiting the mobility of Colorado residents, including the birthing population.1 The impact of such a statewide mandate on birth outcomes has been investigated in Tennessee, where researchers found that the preterm birth rate during the 2020 stay-at-home order was lower than rates in previous years (10.2% vs 11.3%; P = .003).2 Data on the effect of stay-at-home orders on the health of pregnant women and their newborns at population-based state levels are limited. Moreover, significant racial/ethnic disparities exist in US birth outcomes, and data on the differential impact of COVID-19 restrictions on birth outcomes for diverse racial/ethnic groups are also lacking. To provide a larger evidence base for if and how COVID-19 restrictions affected the birthing population at a population-based state level, we sought to compare preterm birth rates during the periods before and after the issuance of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders and to assess whether changes in preterm birth rates varied across racial/ethnic groups in Colorado.

Methods

Data Source

We analyzed Colorado birth certificate records from April to December in 2015-2020 to account for seasonality in the pre– and post–COVID-19 stay-at-home orders. The pre period was defined as April-December 2015-2019, and the post period was defined as April-December 2020.

Cohort Selection

We excluded records with missing or unreasonable values for birth weight (<300 g), gestational age (<20 or >44 weeks), infant sex, delivery method, insurance type, maternal race/ethnicity, age, highest educational level, or marital status.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was preterm birth, defined as gestational age <37 weeks. Gestational age on birth certificates is typically calculated from clinical estimates by first trimester ultrasound and, when missing, the estimated date of the last menstrual period.

Statistical Analyses

We compared maternal and infant characteristics for all births and preterm births separately for pre– and post–COVID-19 stay-at-home orders using the χ2 test with significance at P < .05. Using logistic regression models, we explored the outcomes of preterm births comparing the 2015-2019 birth cohort and the 2020 birth cohort. All variables significant in the bivariate analysis were considered for model inclusion along with birth year. We compared the difference in mean preterm birth rates between non-Hispanic white (NHW) and each racial/ethnic group using an interaction term between maternal race/ethnicity and pre–/post–COVID-19 in the logistic regression model. We explored the crude difference in preterm birth by maternal race/ethnicity between 2015-2019 and 2020 using the χ2 test and calculated aORs for preterm birth in the post–COVID-19 period with logistic regression models for each race/ethnicity, adjusting for the same covariates as in the overall model. SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 296 934 live births were captured by Colorado birth certificates during the study period. After exclusion of 5569 (1.9%) for missing or unreasonable demographic variables (birth weight [n = 525], gestational age [n = 174], infant sex [n = 8], delivery method [n = 29], insurance [n = 1019], maternal age [n = 130], maternal education [n = 3365], marital status [n = 319]), we analyzed a total population of 291 365 births, including 245 106 births during April-December 2015-2019 and 46 259 births during April-December 2020.

Compared with births in 2015-2019, all births and preterm births had a higher prevalence of mothers aged ≥25 years, Hispanic and non-Hispanic black (NHB) mothers, self-pay status, previous preterm birth, diabetes, hypertension, and birth via cesarean delivery in 2020. Among preterm births, there were significantly more births among nonmarried mothers in 2020 than in 2015-2019 (Table I ).

Table I.

Characteristics of all births and preterm births

| Characteristics | All births |

Preterm births |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2019, n (%)∗ | 2020, n (%)† | P value | 2015-2019, n (%)∗ | 2020, n (%)† | P value | |

| Number | 245 106 | 46 259 | 22 176 | 4 117 | ||

| Age, yr | <.0001 | .0084 | ||||

| <20 | 10 540 (4.3) | 1647 (3.6) | 1024 (4.6) | 161 (3.9) | ||

| 20-24 | 42 365 (17.3) | 7495 (16.2) | 3826 (17.3) | 657 (16.0) | ||

| 25-34 | 144 120 (58.8) | 27 279 (59.0) | 12 146 (54.8) | 2266 (55.0) | ||

| ≥35 | 48 081 (19.6) | 9838 (21.3) | 75 180 (23.4) | 1033 (25.1) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | <.0001 | .0009 | ||||

| NHW | 143 708 (58.6) | 26 329 (56.9) | 12 324 (55.6) | 2172 (52.8) | ||

| NHB | 11 111 (4.5) | 2301 (5.0) | 1253 (5.7) | 290 (7.0) | ||

| Native | 2470 (1.0) | 493 (1.1) | 272 (1.2) | 15 (0.4) | ||

| Hispanic | 67 837 (27.7) | 13 374 (28.9) | 6327 (28.5) | 1224 (29.7) | ||

| Other | 19 980 (8.2) | 3762 (8.1) | 2000 (9.0) | 376 (9.1) | ||

| Education level | <.0001 | .1839 | ||||

| <High school | 27 626 (11.3) | 4727 (10.2) | 2824 (12.7) | 511 (12.4) | ||

| High school/GED | 49 042 (20.0) | 9449 (20.4) | 4732 (21.3) | 931 (22.6) | ||

| Some college/associates degree | 27 089 (29.4) | 12 836 (27.7) | 6903 (31.1) | 1229 (29.9) | ||

| ≥Bachelors degree | 96 349 (39.3) | 19 247 (41.6) | 7717 (34.8) | 1446 (35.1) | ||

| Marital status | .3059 | .0220 | ||||

| Married | 186 612 (76.1) | 35 117 (75.9) | 16 045 (72.4) | 2907 (70.6) | ||

| Other | 54 949 (23.9) | 11 142 (24.1) | 6131 (27.7) | 1210 (29.4) | ||

| Insurance | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||

| Public | 108 652 (44.3) | 19 238 (41.6) | 10 635 (48.0) | 1917 (48.6) | ||

| Other | 129 092 (52.7) | 25 097 (54.3) | 10 819 (48.8) | 1977 (48.0) | ||

| Self-Pay | 7361 (3.0) | 1924 (4.2) | 722 (3.3) | 223 (5.4) | ||

| Previous live birth | <.0001 | .3585 | ||||

| Yes | 142 757 (60.1) | 26 977 (58.3) | 13 790 (62.1) | 2529 (61.4) | ||

| No | 97 849 (39.9) | 19 282 (41.7) | 8386 (37.8) | 1588 (38.6) | ||

| Previous preterm birth | <.0001 | .0001 | ||||

| Yes | 7276 (3.0) | 1582 (3.4) | 1919 (8.7) | 432 (10.5) | ||

| No | 237 830 (97.0) | 44 677 (96.6) | 20 257 (91.3) | 3685 (89.5) | ||

| First trimester prenatal care | .0003 | .8840 | ||||

| Yes | 191 704 (78.2) | 36 530 (79.0) | 16 054 (72.4) | 2985 (72.5) | ||

| No | 53 402 (21.8) | 9729 (21.0) | 6122 (27.6) | 1132 (27.5) | ||

| Any diabetes | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 13 698 (5.6) | 3335 (7.2) | 2158 (9.7) | 490 (11.9) | ||

| No | 231 408 (94.4) | 42 924 (92.8) | 20 018 (90.3) | 3627 (88.1) | ||

| Any hypertension | <.0001 | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 20 542 (8.4) | 5226 (11.3) | 4428 (20.0) | 948 (23.0) | ||

| No | 224 564 (91.6) | 41 033 (88.7) | 17 748 (80.0) | 3169 (77.0) | ||

| Delivery method | <.0001 | .0039 | ||||

| Vaginal | 180 331 (73.6) | 33 627 (72.7) | 11 826 (53.3) | 2095 (50.9) | ||

| Cesarean | 64 775 (26.4) | 12 632 (27.3) | 10 350 (46.7) | 2022 (49.1) | ||

| Preterm | .3095 | |||||

| Yes | 22 176 (9.0) | 4117 (8.9) | ||||

| No | 222 930 (91) | 42 142 (91.1) | ||||

| Birth weight, g | .0016 | .1080 | ||||

| <1500 | 2943 (1.2) | 519 (1.1) | 2912 (13.1) | 514 (12.5) | ||

| 1501-2000 | 4352 (1.8) | 786 (1.7) | 3891 (17.6) | 697 (16.9) | ||

| 2001-2500 | 15 423 (6.3) | 3036 (6.6) | 7306 (33.0) | 1341 (32.6) | ||

| 2501-3000 | 53 330 (21.8) | 10 348 (22.4) | 5897 (26.6) | 1111 (27.0) | ||

| <3000 | 169 278 (69.0) | 31 570 (68.2) | 2170 (9.8) | 454 (11.0) | ||

| Sex | .3282 | .0648 | ||||

| Female | 119 975 (48.9) | 22 661 (49.0) | 10 252 (46.2) | 1839 (44.7) | ||

| Male | 125 131 (51.1) | 23 598 (51.0) | 11 924 (53.8) | 2278 (55.3) | ||

GED, General Educational Development.

Significant P values are in bold type.

Pre–COVID-19 (April-December of 2015-2019).

Post–COVID-19 (April-December of 2020).

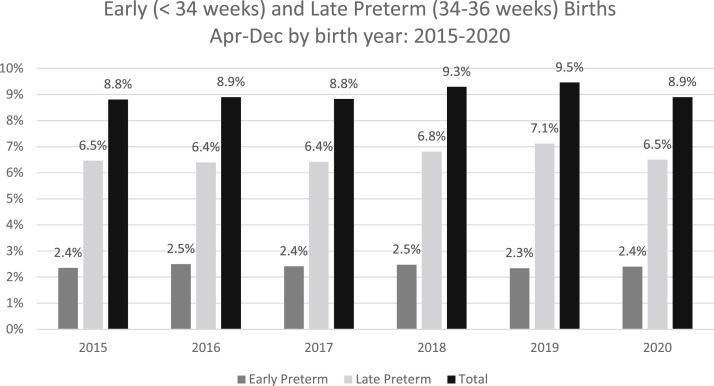

The 2020 overall, early (<34 weeks), and late (34-36 weeks) preterm birth rates were not significantly different than in previous years (8.9% vs 9.05% [P = .3095], 2.40% vs 2.41% [P = .8383], and 6.50% vs 6.63% [P = .2956], respectively) (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). NHB mothers experienced a noticeable, albeit not statistically significant, increase in preterm births from 11.3% to 12.6%. The difference in preterm birth rates between NHW and NHB mothers increased by 30% after issuance of the COVID-19 stay-at-home order, albeit without statistical significance (P = .563).

Figure.

Preterm births by birth year: overall, early, and late preterm births, April-December 2015-2020.

After controlling for covariates, including maternal age, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, insurance, previous preterm birth, first trimester prenatal care, diabetes and hypertension, and birth year, the aOR for preterm birth in 2020 compared with 2015-2019 was 0.923 (95% CI, 0.891-0.957). In stratified analysis, NHW and Hispanic mothers had a lower aOR of preterm birth in 2020 compared with 2015-2019 (0.911 [95% CI, 0.867-0.956] vs 0.910 [95% CI, 0.852-0.956]). Other racial/ethnic groups did not experience any significant change in the aOR of preterm birth in 2020 (Table II).

Table II.

aORs for preterm birth by maternal race/ethnicity in the post–COVID-19 period (reference group: pre–COVID-19 period)

| Maternal race/ethnicity | Total live births, N | Overall, n (%) | 2015-2019, n (%) | 2020, n (%) | P value∗ | aOR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 291 365 | 26 293 (9.0) | 22 176 (9.0) | 4117 (8.9) | .3095 | 0.914 (0.873-0.958) |

| NHW | 170 037 | 14 496 (8.5) | 12 324 (8.6) | 2172 (8.3) | .0814 | 0.884 (0.830-0.941) |

| NHB | 13 142 | 1543 (11.5) | 1253 (11.3) | 290 (12.6) | .0696 | 1.171 (0.969-1.415) |

| Native | 2963 | 327 (11.0) | 272 (11.0) | 55 (11.2) | .9258 | 1.227 (0.798-1.885) |

| Non-native Hispanic | 81 211 | 7551 (9.3) | 6327 (9.3) | 1224 (9.2) | .5249 | 0.913 (0.838-0.995) |

| Other‡ | 23 742 | 2237 (10.0) | 2000 (10.0) | 376 (10.0) | .9771 | 0.928 (0.795-1.083) |

Significant values are in bold type.

Unadjusted χ2 test.

Adjusted for maternal age, education, marital status, insurance, previous preterm birth, first trimester prenatal care, any diabetes (prepregnancy or gestational), any hypertension (prepregnancy or gestational), and birth year.

Includes racial/ethnic categories not listed above and/or individuals who selected more than 1 racial/ethnic category.

Discussion

The decline in the odds of preterm birth following COVID-19 stay-at-home orders in our study is similar to findings from a population-based study in Tennessee. After accounting for multiple maternal characteristics, Harvey et al found that the aOR for preterm birth in 2020 compared with 2015- 2019 was 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79-0.93).2 Several studies outside of the US also have also demonstrated lower preterm birth rates following implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures. Investigators analyzed all singleton births during 2016-2020 using the Icelandic Medical Birth Registrar and found that the preterm birth rate decreased during the first lockdown (aOR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49-0.97) and in the months immediately following the lockdown (June-September) (aOR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.49-0.89).3 In contrast, other US and international studies have demonstrated no significant change in preterm birth rates following COVID-19 restrictions. In a geographically diverse US cohort, Son et al found that the frequency of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes, including preterm birth, did not differ between those delivering before and those delivering during the COVID-19 pandemic.4 This study also showed that outcomes did not differ between women classified as positive and those classified as negative for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection during pregnancy. In Ontario, Canada, Shah et al evaluated nearly 2.5 million pregnancies from 2002 to 2020 and found no special cause variation in preterm birth rate or stillbirth rate during the COVID-19 pandemic.5 The reasons for the variation in results across the US and internationally are not yet well understood, and there is a need to analyze the data in a stratified manner, focusing on subpopulations to better identify risk and protective factors. In our study, although NHW and Hispanic mothers had lower preterm birth rates in the post–stay-at-home period, NHB and American Indian/Alaska Native mothers did not experience this decline. Compared with previous US-based studies, the Colorado birthing population is less heterogeneous with a lower proportion of NHB birthing individuals, which may reduce our power to detect a statistically significant pre/post preterm birth rate change. Although the increase in the preterm birth rate for NHB women from 11.3% to 12.6% was not statistically significant in our analyses, a larger NHB cohort possibly would have had greater power to detect a significant change. In Colorado, Hispanic and NHB residents are overrepresented in COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths.6 For Hispanic mothers, despite higher COVID-19 infection rates in their communities, preterm birth rates declined, suggesting that, as demonstrated by Son et al, infection alone does not explain the association between birth outcomes and COVID-19 positivity. We hypothesize that potentially broader family and/or community supports could allow some pregnant individuals to better weather the enormous stress caused by the pandemic and maintain perinatal health. NHB and American Indian/Alaska Native women have the highest maternal and infant mortality rates in the US.7, 8, 9 We hypothesize that the broad array of factors related to health status, healthcare access, social determinants of health, as well as racism likely persisted in the postrestriction period, and thus these groups experienced no decline in their preterm birth rates. The black–white disparity in preterm births increased during our study period, highlighting the urgent need to disaggregate perinatal health data to fully understand the differential impacts of both negative and positive exposures on our birthing population.

There are limitations to this study, namely the focus on births from one state, limiting potential generalizability beyond Colorado. In addition, although the primary exposure of this analysis was defined as the timing of the stay-at-home order, we recognize that much broader social, economic, and health exposures associated with COVID-19 lockdown orders were likely driving the association between stay-at-home orders and preterm birth rates. In addition, our analysis was limited to maternal race/ethnicity as captured by the birth certificates and did not account for country of origin or immigrant status. We also recognize the heterogeneity within each racial/ethnic group and understand that each subgroup may have been impacted by the COVID-19 restrictions in different ways. Despite these limitations, this analysis contributes to the literature on how COVID-19 stay-at-home orders affected birth outcomes at a statewide population level.

Footnotes

No author has any conflicts of interest.

Appendix

References

- 1.Polis J. Governor of the State of Colorado. Executive Order declaring a state of disaster emergency. March 11, 2020. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://www.colorado.gov/governor/sites/default/files/inline-iles/D%202020%20003%20Declaring%20a%20Disaster%20Emergency_1.pdf

- 2.Harvey E.M., McNeer E., McDonald M.F., Shapiro-Mendoza C.K., Dupont W.D., Barfield W., et al. Association of preterm birth rate with COVID-19 statewide stay-at-home orders in Tennessee. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:635–637. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einarsdóttir K., Swift E.M., Zoega H. Changes in obstetric interventions and preterm birth during COVID-19: a nationwide study from Iceland. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scan. 2021;100:1924–1930. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Son M., Gallagher K., Lo J.Y., Lindgren E., Burris H.H., Dysart K., et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy outcomes in a U.S. population. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138:542–551. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah P.S., Ye X.Y., Yang J., Campitelli M.A. Preterm birth and stillbirth rates during the COVID-19 pandemic: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ. 2021;193:E1164–E1172. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.210081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. https://covid19.colorado.gov/data

- 7.Leonard S.A., Main E.K., Scott K.A., Profit J., Carmichael S.L. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity prevalence and trends. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;33:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ely D.M., Driscoll A.K. Infant mortality in the United States, 2018: Data from the period linked birth/infant death file. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020;69:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics. Maternal mortality rates in the United States. 2019. Accessed August 9, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality-2021/E-Stat-Maternal-Mortality-Rates-H.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.