Abstract

Background:

Periodontitis not only causes injury to the periodontium, but also damages other tissues such as: articulate, renal, cardiac and hepatic. The objective of this study was to investigate periodontitis induced alterations in liver function and structure using an experimental model.

Methods:

Twenty female rats (Rattus norvegicus) were allocated into two groups: control and periodontitis. Gingival bleeding index and oxidative stress parameters and specific circulating biomarkers were measured. Immunohistochemistry was carried out using alkaline phosphatase (AlkP) staining of the liver. Hepatic tissues, cytokines and lipid contents were measured. Histopathological evaluation of the liver was carried out using light and electron microscopy.

Results:

Liver histopathological and immunohistochemistry assessment showed increase in steatosis score, and presence of binucleate hepatocytes and positive cells for AlkP in periodontitis vs. control group. Ultrastructural evaluation showed significant increase in size and number of lipid droplets (LD), distance between the cisterns of rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), mitochondria size, foamy cytoplasm and glycogen accumulation in the liver of the periodontitis group compared with the control group. In addition, plasma levels of AlkP, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides and total cholesterol were also changed.

Conclusion:

Experimental periodontitis caused immunohistochemistry, histopathological, ultrastructural, oxidative and biochemical changes in the liver of rats.

Keywords: periodontal diseases, liver, oral medicine, cytokines, inflammation

SUMMARY SENTENCE:

A relationship between periodontitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has been suggested, but not yet established. Our findings are of great significance for dentists and periodontists, since this is a two-way relationship and abnormal liver function may be associated with periodontitis despite normal liver function tests.

Introduction

Periodontitis is an infectious and inflammatory disease, affecting 30–45% of the adults and is an important problem in the world associated to the oral diseases.1,2 Tissue damage caused by periodontitis results from imbalances in the host response caused by bacteria, periodontal pathogens and other end-metabolites that stimulate the over-production of inflammatory mediators. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) released by defense cells in response to bacteria, periodontal pathogens, end-metabolites and lipopolysaccharides (LPS) contribute to periodontal damage.3–5

Periodontitis not only causes injury to the periodontal tissues but also damages other tissues such as: articulate,6 renal,7 cardiac8 and hepatic.9–12

The non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized by fatty liver accumulation in more than 5% of the hepatocytes in the absence of excessive ethanol ingestion.13 NAFLD is estimated to affect 30% of the general population around the world.14 Abnormalities in the metabolism of carbohydrates and lipids are hallmarks of NAFLD.15 Oxidative stress is one of the key elements associated to the pathophysiological mechanism of inflammatory conditions that happen in NAFLD.16 Furthermore, cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) can accelerate the accumulation of fat in the liver, augmenting the inflammatory process and promoting the evolution to fibrosis or liver cirrhosis.16,17

In addition, gut microbiota have been implicated as an emerging cause of NAFLD.18,19 In this regard, some studies have demonstrated that bacteria associated with periodontitis such as Porphyromonas gingivalis10 and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans20 may influence the development/progression of NAFLD. These and other bacteria associated with periodontitis present LPS in their cell wall, which can be catalyzed by alkaline phosphatase (AlkP), a superfamily of metalloenzymes, removing the lipid A phosphates of LPS.21 This catalytic process reduces the affinity for Toll-like receptor 4.22 In addition, AlkP can regulate the uptake of lipoproteins and act as a marker for liver diseases.23,24

Several tools for the clinical diagnosis of NAFLD have been developed, including biomarkers and imaging techniques, but the gold standard for diagnosis is still histopathological assessment.25 Besides fatty liver accumulation into the hepatocyte, hepatocytes of the fatty liver may present one or more nuclei, a feature that can be associated with cell division. It has been shown that oxidative stress may cause cytokinesis failure, leading to incomplete cell division upon and binucleation.26 In addition, oxidative stress is associated with ultrastructural changes in the hepatocytes of liver diseases.27,28

We have demonstrated previously that the ligature-induced periodontitis caused microvesicular steatosis and this process can be reverted after the removal of the ligature from the teeth.11 Another study from our research team demonstrated that the pericytes were associated with changes in the hepatic tissues.12 Although this association between periodontitis and NAFLD has been proposed,9–12,29,30 several points still remain unclear.

No study has evaluated immunohistochemistry to cells positive for alkaline phosphatase (AlkP), cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and the evaluation for histopathological (binucleate hepatocytes) and ultrastructural components in liver. Additionally, we assessed liver oxidative stress, lipid levels, and blood biomarkers. In order to clarify these points, the model of periodontitis induced with ligature was used in this study.

Material and Methods

Animals

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Piauí (384/17). Twenty female Wistar rats (222.4 ±4.8g) were kept in an air-conditioned room at 23–25°C, relative humidity of 50–70%, and 12h dark/light cycle. The rats had free access to food and water and were maintained for one week for acclimation before the experiment.

Experimental Design

Rats were randomly divided into two groups (10 animals per group, female): control (no ligature) and periodontitis (rats with ligature). Experimental periodontitis was performed with intramuscular solution of 2% xylazine hydrochloride (15 mg/Kg)# and ketamine (40 mg/Kg)**. A nylon ligature 3–0,†† was inserted around the first lower molar of each animals bilaterally.12,31 After 20 days,11,12 rats were euthanized and blood was collected for biochemical tests. Following, the liver and body weights were measured in total (g) to calculate liver index (%, liver weight × 100/total body weight).

Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) and assay for Myeloperoxidase (MPO)

The score was evaluated according to Liu et al.14 in score 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 for the 1st lower molars bilaterally. For MPO, the assay was performed following that described by Chaves et al.32

Mobility (M) of 1st lower molars assessment and Probing Pocket Depth (PPD)

The mobility of the first mandibular molars was measured with a periodontal probe in the labiolingual direction and scored as: 0, physiological mobility; 1, slight mobility; 2, moderate mobility; 3, severe mobility.33 Values of PPD were evaluated with round-ended probe, tip 0.4 mm in diameter.14

Alveolar Bone Loss (ABL)

The assessment of ABL followed Vasconcelos et al.12 and images captured were evaluated with an image analysis system.‡‡

Histopathological evaluation of the liver

The livers of the rats were collected from the left lobe and routinely processed according to Vasconcelos et al.12

Steatosis score was categorized, according to the percentage of fatty hepatocytes distributed in the liver, as: 1, 0<25%; 2, 26<50%; 3, 51<75%; and 4, >76%. Inflammation and necrosis score were graded as: one focus per field, 1 and two or more focus per field, 2.31,34 Regarding the number of binucleate hepatocytes, we counted an area of 45,000 μm2 of hepatic tissue with light microscopy.§§ For the assessment of mast cell density (DMCS), the total number of positive cells on toluidine blue stained was counted according to Franceschini et al.35

Immunohistochemistry for alkaline phosphatase (AlkP)

Hepatic tissues were stained for AlkP and the intensity was measured for an area of 45,000 μm2. After routine histological preparation, paraffin was removed and endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 5% H2O2 in water. After blocking non-specific reactivity with bovine serum albumin (3%) in phosphate-buffered saline, goat polyclonal primary antibody (1% bovine serum albumin/ phosphate-buffered saline): anti-rat AlkP‖‖ 20 μg/ ml was applied to the sections, overnight at 4 °C. After that, the sections were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody,¶¶ followed by streptavidin–peroxidase complex¶¶ for 40 min at 37.5 °C. Diaminobenzidine solution (3,3 diaminobenzidine) was used for brown staining in the sections and hematoxylin was used for counterstaining.

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) assessment of hepatocytes

Liver pieces with 1 mm3 of medial and lateral lobes were processed according to López-Navarro et al.36 Sections were viewed and photographed using a transmission electron microscope## at 80 kV. Digital images were captured using a digital camera system.*** In order to evaluate Lipid Droplets (LD), we counted and measured images from the livers of both groups on the 6,000x magnification of each photomicrograph containing at least one hepatocyte nucleus, according to Watanabe et al.37 In addition, the distance between the cisterna of rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and the size of mitochondria were measured on the 15,000x magnification. The foamy cytoplasm was performed using a 100-point mesh in an area of 1,170 μm2 on the 8,000x magnification. The glycogen accumulation was scored in: 0, physiological storage; 1, slightly accumulated storage; 2, moderately accumulated storage; and 3, severely accumulated storage. All ultrastructures examined were based on Ghadially.38 All images were analyzed using an image analysis system.‡‡

Quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For the evaluation of NO3/NO2 concentration, the liver homogenate was incubated in a microplate with nitrate reductase for 12 hours to convert nitrate (NO3) into nitrite (NO2). Nitric oxide production was determined by measuring nitrite concentrations in an ELISA plate reader at 540 nm.39

Regarding the cytokine measurements for IL-1β and TNF-α, samples of hepatic tissue were collected and homogenized in sterile saline. Subsequently, the IL-1β and TNF-α levels were performed using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The homogenates were centrifuged at 0.8g at 4°C for 11min, and supernatants were stored at −70°C until further analysis.

For blood biomarkers, levels of AlkP, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma glutamyltranspeptidase (GGT), glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides were measured. For the liver evaluation, concentration of total cholesterol and triglycerides were measured according to Folch Less and Sloane Stanley,40 and both tests for blood and liver used commercial ELISA kits.†††

Glutathione (GSH), malondialdehyde (MDA) and glucose levels

In order to investigate the systemic effect of periodontitis on hepatic oxidative stress, we used GSH levels, which were measured according to Sedlak et al.41

The MDA levels were used as an indicator of lipid peroxidation. The MDA concentration for the liver was measured according to Mihara et al.42

In order to evaluate the random glucose levels in the blood, we used a glucometer,‡‡‡ previously to the euthanasia of the animals.

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean or mode (±S.E.M. and/or minimum-maximum). Kolmogorov-smirnov test was used to check the distribution of the data. Differences between the groups were examined with the Mann-Whitney U test, for data with non-normal distribution and with the unpaired T-test for normally distributed data. * p < 0.05.

Results

GBI, mobility of 1st molar, MDA and MPO levels

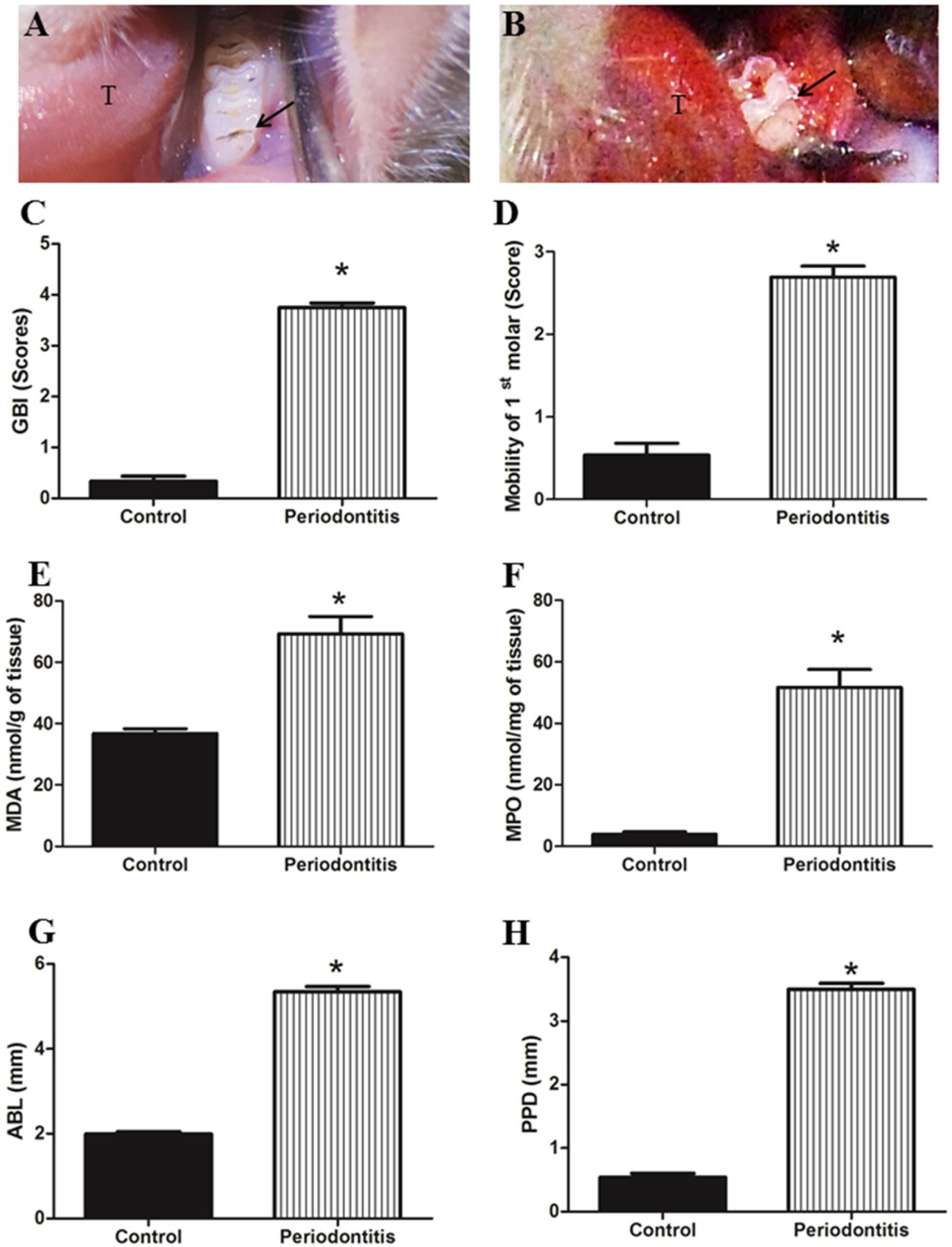

The animals with experimental periodontitis (periodontitis group) presented altered color, severe edema and bleeding of gingival papilla compared to the control group (Figure 1 A and 1 B, control and periodontitis groups respectively). GBI (Figure 1 C), mobility of 1st molar (Figure 1 D), MDA (Figure 1 E) and MPO levels (Figure 1 F) were significantly higher in the animals with experimental periodontitis than in the animals without experimental periodontitis, as seen in figure 1.

Figure 1.

A) represents clinical aspect from control group, tongue is represented in T and the first molar by arrow. B) Clinical aspect of the periodontitis group, presenting gingival papilla with alteration in color, severe edema and bleeding after slight probe. C) Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) scores. D) Mobility (M) of the 1st molar. E) MDA level. F) Myeloperoxidase (MPO) levels. G) Sum of alveolar bone loss (ABL). H) Probing Pocket Depth (PPD). GBI scores, M, MDA and GSH levels, ABL and PPD presented significantly higher values in periodontitis group than control group. * p < 0.05.

Evaluation of ABL and PPD

The periodontitis group presented significantly increased values for ABL (Figure 1 G) and PPD (Figure 1 H).

GBI, M, MDA, MPO, sum of ABL and PPD values showed robust evidence of the presence of periodontitis, supporting subsequent systemic assessments.

Body, liver weights, blood and liver biomarkers

The body and liver weights did not present difference (p>0.05) between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Weight parameters, blood and liver biomarkers.

| Groups | Control | Periodontitis |

|---|---|---|

| Weight parameters | ||

| Body (g) | 218.4 ± 5.0 | 226.5 ± 4.6 |

| Liver | ||

| Relative (%) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

| Absolute (g) | 7.1 ± 0.3 | 7.0 ± 0.4 |

| Blood biomarkers | ||

| AlkP (U/dL) | 46.1 ± 6.9 | 67.9 ± 5.7* |

| AST (U/dL) | 67.2 ± 2.3 | 87.6 ± 6.1 |

| ALT (U/dL) | 28.5 ± 2.5 | 34.9 ± 1.7 |

| GGT (U/dL) | 10.1 ± 2.5 | 15.4 ± 3.8 |

| Glucose# (mg/dL) | 268.1 ± 14.5 | 259.6 ± 18.6 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 62.4 ± 2.2 | 80.3 ± 4.9* |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 77.4 ± 3.0 | 38.2 ± 1.4* |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 58.1 ± 3.8 | 84.7 ± 3.6* |

| Liver biomarkers | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 1.0* |

| Triglycerides | 97.2 ± 5.0 | 134.3 ± 11.8* |

| IL-1β (pg/mg) | 307.5 ± 7.6 | 302.7 ± 13.1 |

| TNF-α (pg/mg) | 239.4 ± 4.1 | 247.4 ± 3.7 |

| NO3/NO2 (mM) | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.0* |

| MDA (mmol/g of the tissue) | 84.0 ± 3.7 | 122.0 ± 9.7* |

| GSH (μmol/g of the tissue) | 461.7 ± 37.9 | 150.0 ± 45.3* |

| MPO (mmol/g of the tissue) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

p < 0.05 comparing to periodontitis versus control groups (unpaired T-test).

Results were expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

Random Blood Glucose.

Biomarkers, AlkP, HDL, triglycerides and total cholesterol were significantly changed in the periodontitis group in comparison with the control group (Table 1). Plasma GGT, AST, ALT and glucose presented higher levels in the periodontitis group than in the control group (p>0.05). In addition, hepatic and plasma levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides were significantly higher in the periodontitis group compared to the control group (Table 1).

NO3/NO2, MDA, GSH and MPO content in liver

In the hepatic tissue, NO3/NO2, MDA and MPO concentrations were shown to be significantly increased in the periodontitis group, compared with the control group (Table 1). Hepatic oxidative stress, assayed by GSH levels, was significantly decreased in the periodontitis vs. control group (Table 1).

Cytokine measurements for IL-1β and TNF-α

As shown in the table 1, IL-1β and TNF-α levels in the liver were not significantly different between the groups.

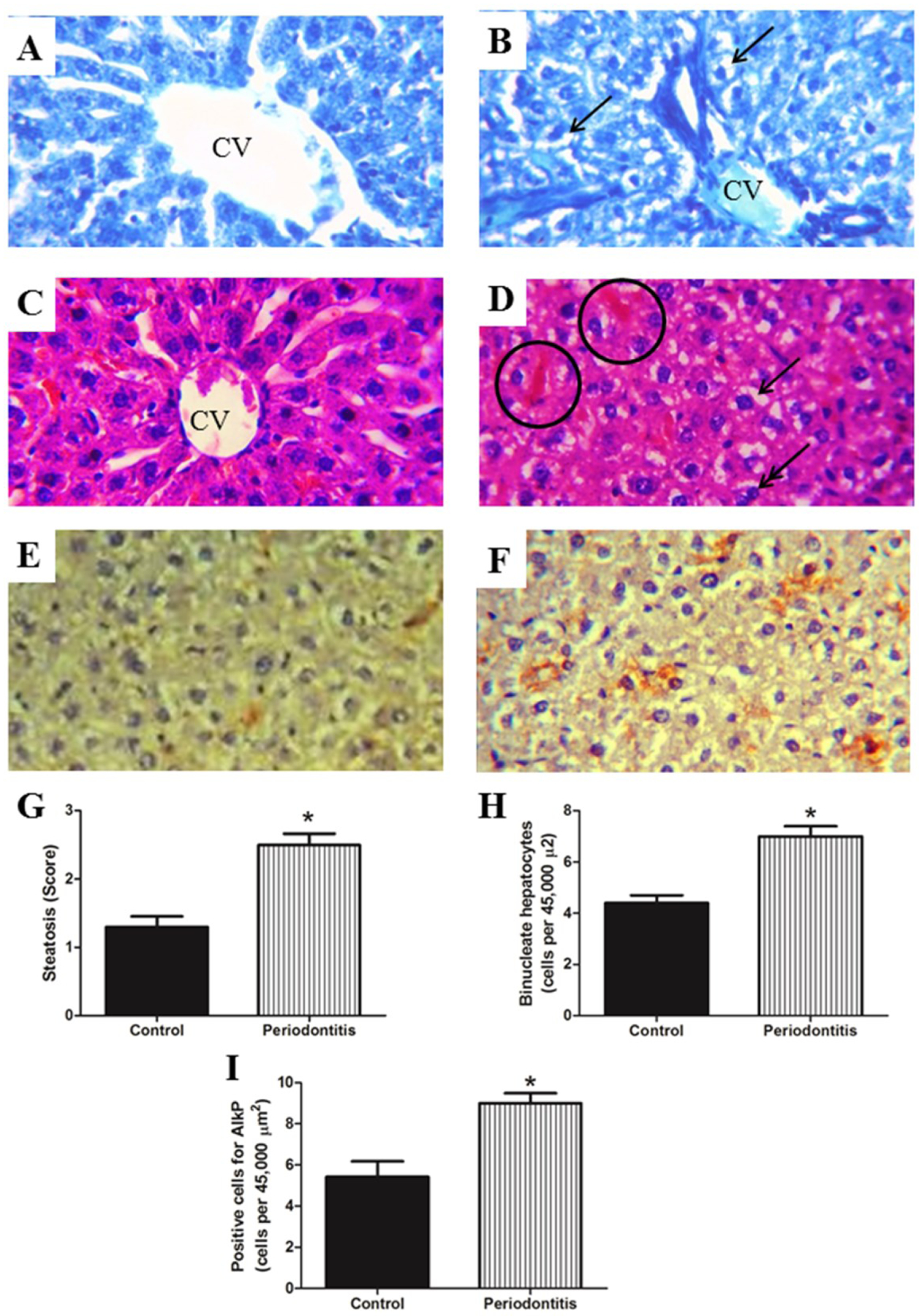

Histopathological and Immunohistochemistry hepatic tissue assessment with light microscopy

Control group presented normal histological structure for the hepatic tissue evaluation. (Figure 2 A and C). On the other hand, liver tissues from the periodontitis group demonstrated marked histopathological changes, such as: hepatocytes with microvesicular steatosis, loss of cordon organization near the central vein and congestion in sinusoid blood vessels (Figure 2 B and D). AlkP positive cells were significantly increased in the periodontitis group compared to the control group (Figure 2 E, F and I). In addition, the periodontitis group had higher liver steatosis score (Figure 2 G) and binucleated hepatocytes (Figure 2 H), compared to control group. There were no significant differences in inflammation degree, necrosis and DMCS count between the groups (Inflammation, 1 (1–2) for control group, 1 (1–2) for periodontitis group; necrosis, 1 (1–1) for control group, 1 (1–1) for periodontitis group; DMCS count, 1.7 ±0.5 for control group, 1.8 ±0.5 for periodontitis group; p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Liver in A) and C) demonstrating hepatocytes with normal organization surrounding the central vein (CV). Fatty liver (arrows) is illustrated in B) and D) for the periodontitis group, congestion in sinusoid blood vessels (circle) and binucleate hepatocytes (double arrow) are also observed. The periodontitis group presented higher values for G) steatosis score, H) number of binucleate hepatocytes and I) positive cell for AlkP compared with control group. E) illustrate positive cells for AlkP in the control group and F) in the periodontitis group. A and B) toluidine blue, C and D) hematoxylin and eosin, E and F) immunohistochemistry for AlkP, all photomicrographs are at 600x original magnification. * p < 0.05.

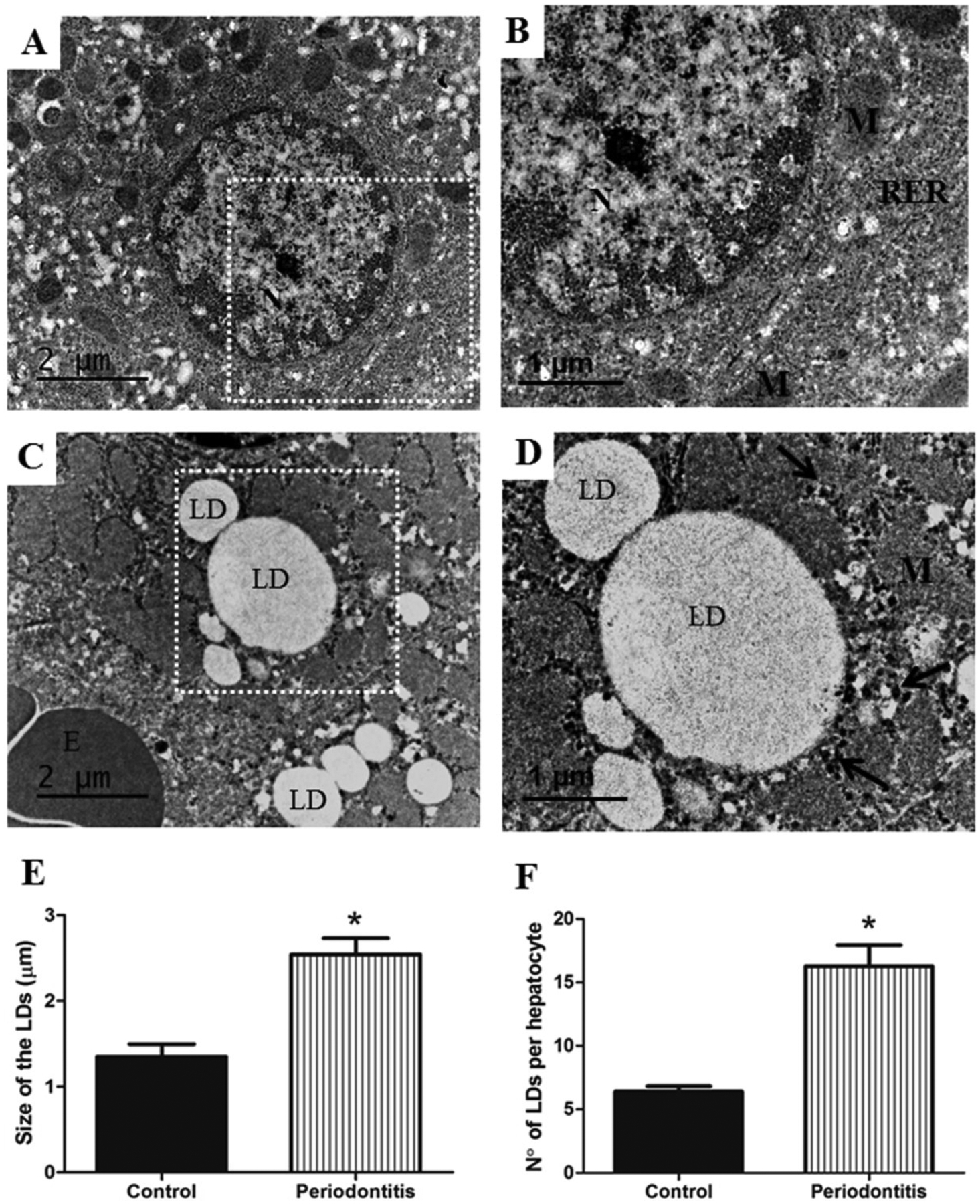

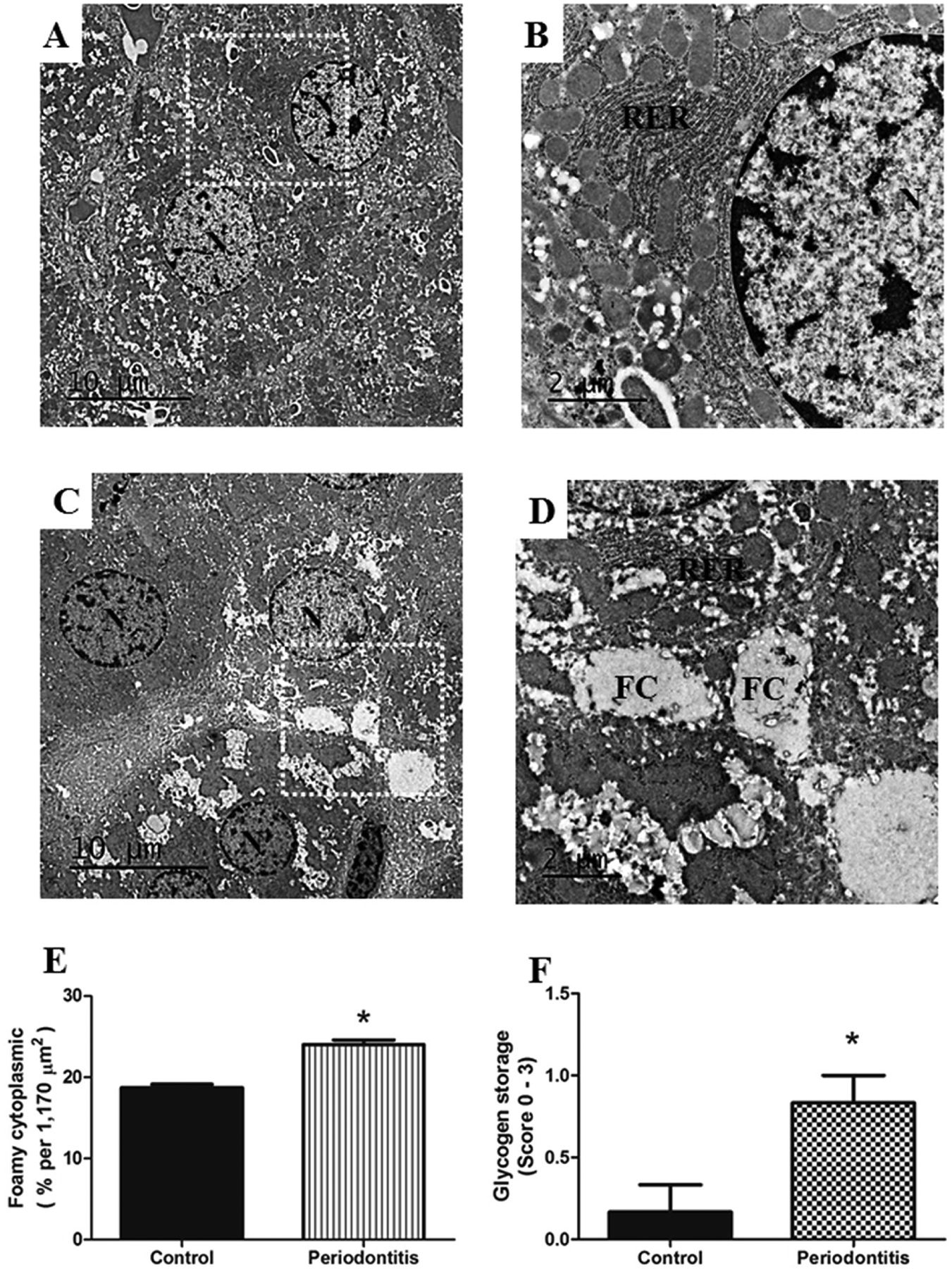

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) assessment of hepatocytes

The periodontitis group caused a significant increase in size and number of the LDs per hepatocytes, compared to the control group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A) Hepatocyte with normal ultrastructures from control group, white rectangle shows B) area at higher magnification, demonstrating normal aspect of mitochondria (M), rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and nucleus (N). On the other hand, C) the periodontitis group shows hepatocyte with increase in size and number of lipid droplets (LD), D) area at higher magnification, representing detail from LD and glycogen accumulation (arrows). Higher values for E) size and F) number of LD were observed in the periodontitis group rather than in the control group. E, erythrocyte; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus. Images A) and C) of TEM are at ×10,000 original magnification, and B) and D), at ×15,000 original magnification. * p < 0.05.

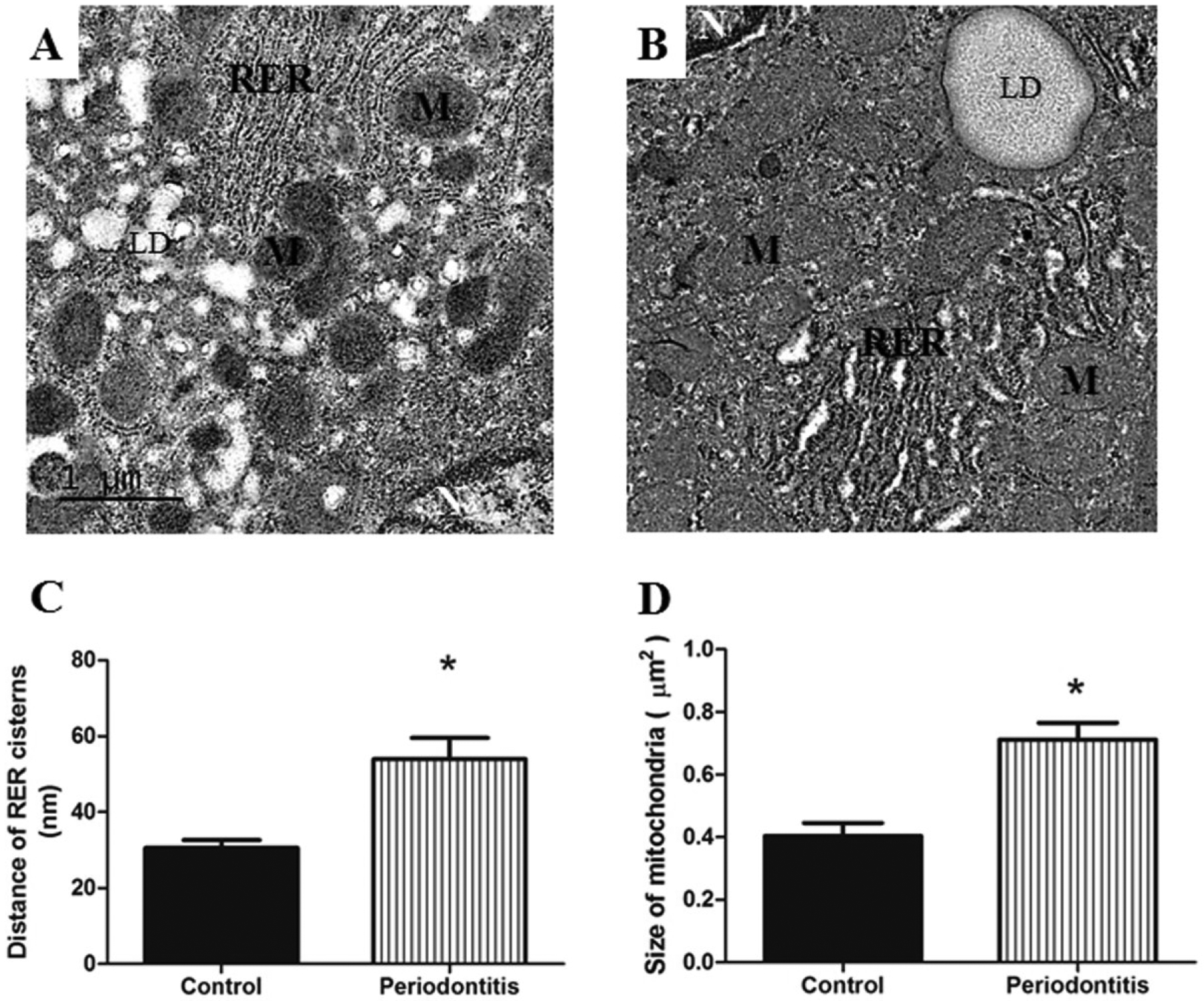

As for the assessment of the RER, figure 4 A represents normal RER in the control group. Changed RER is shown in the figure 4 B, illustrating the dilation of cistern of the RER for the periodontitis group, 75.8% higher (Figure 4 C).

Figure 4.

A) Hepatocytes with normal mitochondria (M) and RER are observed in the control group. B) illustrates hepatocyte with dilatation of RER and mitochondria larger in the periodontitis group, when compared with control group; in addition, the mitochondria of periodontitis group were presented as less electron-dense with less distinct cristae. Periodontitis group presented C) dilation of cistern of the RER and D) larger mitochondria in comparison with the control group. LD, lipid droplets; N, nucleus; RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum. Images of TEM are at ×15,000 original magnification. * p < 0.05.

The mitochondria showed normal structures for the control group (Figure 4 A). In contrast, mitochondria appear significantly larger in the periodontitis group (Figure 4 D). In addition, the mitochondria of the periodontitis group were presented as less electron-dense with less distinct cristae (Figure 4 B).

In relation to the ultrastructural evaluation of smooth endoplasmic reticulum (SER) into hepatocyte, normal SER from the control group was observed (Figure 5 A and B). On the other hand, in the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte from the periodontitis group, there was the appearance of abundant foamy cytoplasm (Figure 5 C and D). Foamy cytoplasm stem from the proliferation of SER (Figure 5 D and E) and glycogen accumulation (Figure 3 D), and a significant difference was observed between the groups (Figure 5 E for foamy cytoplasm and figure 5 F for glycogen).

Figure 5.

A) Two normal hepatocytes are observed in the center of the image of the control group, B) white rectangle shows the area at higher magnification, demonstrating normal RER, rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), N, nucleus. C) shows hepatocytes with abundant foamy cytoplasm (FC) from the periodontitis group. D) presents the area from the white rectangle with higher magnification, demonstrating details of FC in the hepatocyte from rats with periodontitis. Periodontitis caused increase in the E) FC and F) in the glycogen storage into hepatocytes compared with hepatocytes from the control group. N, nucleus. Images A) and C) of TEM are at ×2,500 original magnification, and B) and D), at ×8,000 original magnification. * p < 0.05.

Discussion

Our study was designed to provide a better understanding for the association between periodontitis and liver abnormalities. Herein, we showed with robust data relevant changes in the liver of animals with ligature-induced periodontitis. This is the first study in the literature, showing the development of significant alterations in the histopathology of the liver, including increase in number of binucleate and AlkP positive hepatocytes in experimental periodontitis compared to control group. In addition, our results demonstrated significant increase in size and number of LDs, distance between the cisterns of RER, mitochondria size, foamy cytoplasm and glycogen accumulation as well as for NO3/NO2 levels in the liver of periodontitis group vs. control group. Besides, serum AlkP levels were significantly higher in the periodontitis group.

Our research team has previously demonstrated microvesicular steatosis in rats with periodontitis,11,12 but the increase in the number of binucleate hepatocytes in animals with periodontitis had not been previously reported in the literature by then. Nonetheless, binucleate hepatocytes stand out as an attempt by damaged hepatocytes to regenerate.43 A strategy of our study was to use female rats to obtain higher number of binucleate hepatocytes per gram of liver caused by sexual dimorphism.44 This approach possibly increased the success of our investigation. Testing the reproducibility of our data using male rats might be interesting.

Regarding measures of steatosis (p<0.05), the mean values for inflammation and necrosis scores were higher for rats with periodontitis than for rats without periodontitis, (p>0.05), which is consistent with previous studies11,12, again confirmed here by our research team. We did not find macrovesicular steatosis or hepatic fibrosis in the livers. MPO data together with the cytokines levels for IL-1β and TNF-α demonstrated no significant increase between the groups, indicating that the process of steatosis caused by periodontitis was light in comparison with steatohepatitis, in which the inflammatory process is evident, with significant elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines.17,45

We have previously demonstrated that the microvesicular steatosis is associated with higher levels of GSH and MDA caused by periodontitis.11,12 In this study, for the first time, in NO3/NO2 levels, we demonstrated that this marker was higher in the periodontitis group than in the control group. These elevated levels brought together several findings from our study. A study showed that hepatocytes do not complete cell division upon oxidative stress, leading to cytokinesis failure and binucleation,26 as observed in our study. We believe that an eventual increase in binucleate hepatocytes points out to compensatory proliferation associated with liver injury caused by periodontitis.

This study is the first in the literature to describe ultrastructural changes in the liver associated with periodontitis. It was possible to observe the main characteristic of steatosis, which is the fatty accumulation in the hepatocytes. The increase in oxidative and NO3/NO2 levels caused the surplus release of lipid peroxidation products,46 as also demonstrated by our data with elevated MDA hepatic levels in rats with ligatures. In addition, the data of total cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood as well as in the liver (Table 1) supported this finding. In order to evaluate the ultrastructure of LDs in hepatocytes, we used TEM, which enabled us to count the number and size of LDs. The periodontitis group presented LD size 92.3% larger than the control groups (Figure 3); this finding is similar to the other study that evaluated fatty accumulation in liver of rats treated with ethanol.47 Another alteration observed by us is that the number of LDs was also higher (53.1%) in the periodontitis group (Figure 3). LDs occupy the cytoplasmic space of hepatocytes, diminishing cellular functions.48 LDs are not just inclusions, but dynamic organelles that perform several biological activities and are in balance with blood lipids,15 according to our results for increased levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides both in blood and in the hepatic tissue.

We demonstrated previously11 that the blood lipid profile of rats with periodontitis was similar to these data (Table 1). An emerging hypothesis is linked with the lipid metabolism and bacteria involved with periodontitis increasing the risk of the development/progression of NAFLD.10,20 Further studies could elucidate the association between the ligature-induced periodontitis and the mechanisms of the development of NAFLD. In addition, the ligature-induced periodontitis model used currently is the way of simulating the periodontitis-related bacteria in humans and their systemic effects.

In relation to the ultrastructural evaluation, we also observed that the mitochondria of hepatocytes from the periodontitis group were larger than those from the control group. Besides that, the mitochondria from rats with periodontitis were appeared as less electron-dense and less distinct cristae (Figure 4), indicative of degraded membrane constituents, as shown in rats with alloxan-induced diabetes.28 Mitochondria play a key role in ATP production and the increase in oxidative stress is associated with the fall in ATP production, causing mitochondrial damage.49 These findings are consistent with increased GSH, MDA and NO3/NO2 levels, as well as with ultrastructural alteration observed in the size of mitochondria.

We speculate that the high levels of AlkP in the rat liver is associated with LPS from bacteria involved in periodontitis,10,20 because AlkP mediates host-bacterial interactions through their capacity to dephosphorylate lipid A of the bacterial cell wall lipopolysaccharide.50 In addition, AlkP activity is also related to lipid metabolism.23 Our data regarding the AlkP are supported by previous findings and brought an association with the induced periodontitis still not reported in the literature.

The experimental periodontitis caused changes in the LDs, mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, both smooth and rough observed by TEM. The hepatocytes from rats with periodontitis showed significant dilation in the RER in comparison with rats without periodontitis, as observed in the figure 4. Similarly, SER also presented significant changes (Figure 5) that are associated with possible damages caused by imbalance of oxidative stress associated with periodontitis. The SER from rats with periodontitis demonstrated foamy cytoplasm (Figure 5 C, D and E), resulted from the proliferation and glycogen accumulation (Figure 3 D and 5 F). These novel findings of the ultrastructural changes in rat hepatocytes are similar to those found in human with NAFLD,27 although these findings must be viewed with caution, because in the periodontitis model with ligature the inflammation is rapid in onset and severe.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrate here major changes in the liver structure and function of animals with periodontitis induced by ligature. This is the first study in the literature demonstrating a significant increase in the number of binucleate and AlkP positive hepatocytes, increase in size, number of LDs, the distance between the cisterns of RER, mitochondria size, foamy cytoplasm and glycogen accumulation in the liver of rats with periodontitis.

Acknowledgements

Study supported by the Federal University of Piaui (UFPI - Edital PIBIC 2015/2016, Edital PIBIC 2016/2017), FRPS and LSP by CAPES and DFPV by CNPq (455104/2014-0).

Footnotes

Rompum-Bayer®, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Francotar-Virbac®, Roseira, SP, Brazil.

Shalon®, Goiania, GO, Brazil.

ImageJ v.1.48 Software.

NOVA®, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil.

Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA.

LSAB2 system, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark.

JEM 1400, JEOL, Japan.

Gatan, Pleasanton, CA, United States

Labtest®, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Accu-Chek Active, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, Estupinan-Day S, Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83:661–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 2015; 86:611–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapple IL. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Periodontol 1997; 24:287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White P, Sakellari D, Roberts H, et al. Peripheral blood neutrophil extracellular trap production and degradation in chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 2016; 12:1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira RR, Fermiano D, Feres M, et al. Levels of candidate periodontal pathogens in subgingival biofilm. J Dent Res 2016; 95:711–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin CH, Chen DY, Chao WC, et al. Association between periodontitis and the risk of palindromic rheumatism: A nationwide, population-based, case-control study. PLoS One 2017; 8:e0182284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.França LFC, Vasconcelos ACCG, Silva FRP, et al. Periodontitis changes renal structures by oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. J Clin Periodontol 2017; 6:568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Köse O, Arabacı T, Gedikli S, et al. Biochemical and histopathologic analysis of the effects of periodontitis on left ventricular heart tissues of rats. J Periodontal Res 2017; 52:176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomofuji T, Ekuni D, Yamanaka R, et al. Chronic administration of lipopolysaccharide and proteases induces periodontal inflammation and hepatic steatosis in rats. J Periodontol 2007; 78:1999–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoneda M, Naka S, Nakano K, et al. Involvement of a periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis on the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2012; 12:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho JS, Di Lenardo D, Alves EHP, et al. Steatosis caused by experimental periodontitis is reversible after removal of ligature in rats. J Periodontal Res 2017; 52:883–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasconcelos DFP, Silva FRP, Pinto ME, et al. Decrease in pericytes is associated with ligature-induced periodontitis liver disease in rats. J Periodontol 2017; 88: e49–e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abd El-Kader SM, El-Den Ashmawy EM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the diagnosis and management. World J Hepatol 2015; 7:846–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedogni G, Miglioli L, Masutti F, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Dionysos nutrition and liver study. Hepatology 2005; 42:44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walther TC, Farese RV. The life of lipid droplets. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 6:459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikolasevic I, Milic S, Turk Wensveen T, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - A multisystem disease? World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22:9488–9505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilg H, Diehl AM. Cytokines in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1467–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau E, Carvalho D, Freitas P. Gut microbiota: association with NAFLD and metabolic disturbances. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015:979515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everard A, Matamoros S, Geurts L, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii administration changes gut microbiota and reduces hepatic steatosis, low-grade inflammation, and fat mass in obese and type 2 diabetic db/db mice. MBio 2014. 10; 5:e01011–14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komazaki R, Katagiri S, Takahashi H, et al. Periodontal pathogenic bacteria, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans affect non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by altering gut microbiota and glucose metabolism. Sci Rep 2017; 1:13950. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poelstra K, Bakker WW, Klok PA, et al. A physiologic function for alkaline phosphatase: endotoxin detoxification. Lab Invest 1997; 76:319–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HM, Park BS, Kim JI, et al. Crystal structure of the TLR4-MD-2 complex with bound endotoxin antagonist Eritoran. Cell 2007; 130:906–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lynes M, Narisawa S, Millán JL, Widmaier EP. Interactions between CD36 and global intestinal alkaline phosphatase in mouse small intestine and effects of high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011; 301:R1738–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poupon R Liver alkaline phosphatase: a missing link between choleresis and biliary inflammation. Hepatology 2015; 6:2080–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takahashi Y, Fukusato T. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: overview with emphasis on histology. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 42:5280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tormos-Ana M, Taléns-Visconti R, Jorques M, et al. p38α deficiency and oxidative stress cause cytokinesis failure in hepatocytes. Free Radic Biol Med 2014; 75: S19. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahishali E, Demir K, Ahishali B, et al. Electron microscopic findings in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: is there a difference between hepatosteatosis and steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 5:619–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucchesi AN, Cassettari LL, Spadella CT. Alloxan-induced diabetes causes morphological and ultrastructural changes in rat liver that resemble the natural history of chronic fatty liver disease in humans. J Diabetes Res 2015; 2015:494578. doi: 10.1155/2015/494578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saito T, Shimazaki Y, Koga T, Tsuzuki M, Ohshima A. Relationship between periodontitis and hepatic condition in Japanese women. J Int Acad Periodontol 2006; 8: 89–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akinkugbe AA, Slade GD, Barritt AS, et al. Periodontitis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a population-based cohort investigation in the study of health in Pomerania. J Clin Periodontol 2017; 44:1077–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pessoa LS, Pereira-da Silva FR, Alves EHP, et al. One or two ligatures inducing periodontitis are sufficient to cause fatty liver. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2018; 23 :e269–76. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaves LS, Nicolau LA, Silva RO, et al. Antiinflammatory and antinociceptive effects in mice of a sulfated polysaccharide fraction extracted from the marine red algae Gracilaria caudata. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2013; 35:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Wei W. A comparative study of systemic sub antimicrobial and topical treatment of minocycline in experimental periodontitis of rats. Arch Oral Biol 2006; 51:794–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Younossi ZM, Baranova A, Ziegler K, et al. A genomic and proteomic study of the spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005; 42:665–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franceschini B, Russo C, Dioguardi N, Grizzi F. Increased liver mast cell recruitment in patients with chronic C virus-related hepatites and histologically documented steatosis. J Viral Hepat 2017; 14:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.López-Navarro AT, Bueno JD, Gil A, Sánchez-Pozo A. Morphological changes in hepatocytes of rats deprived of dietary nucleotides. Br J Nutr 1996; 76:579–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watanabe E, Muenzer JT, Hawkins WG, et al. Sepsis induces extensive autophagic vacuolization in hepatocytes: a clinical and laboratory-based study. Lab Invest 2009; 89: 549–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghadially FN. Ultrastructural pathology of the cell and matrix. London: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1988:1–775. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Green LC, Wagner DA, Glogowski J, Skipper PL, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Analysis of nitrate, nitrite, and [15N] nitrate in biological fluids. Anal Biochem 1982; 126:131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folch J, Less M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 1957; 226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal Biochem 1968; 24:192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mihara M, Uchiyama M. Determination of malonaldehyde precursor in tissues by thiobarbituric acid test. Ana Biochem 1978; 86:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elkhateeb A, El Khishin I, Megahed O, Mazen F. Effect of Nigella sativa Linn oil on tramadol-induced hepato- and nephrotoxicity in adult male albino rats. Toxicol Rep 2015; 2:512–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marcos R, Lopes C, Malhão F, et al. Stereological assessment of sexual dimorphism in the rat liver reveals differences in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells but not hepatic stellate cells. J Anat 2016; 228:996–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Handa P, Vemulakonda AL, Maliken BD, et al. Differences in hepatic expression of iron, inflammation and stress-related genes in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Ann Hepatol 2017; 16:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henkel J, Frede K, Schanze N, et al. Stimulation of fat accumulation in hepatocytes by PGE2-dependent repression of hepatic lipolysis, β-oxidation and VLDL-synthesis. Lab Invest 2012; 92:1597–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eid N, Ito Y, Maemura K, Otsuki Y. Elevated autophagic sequestration of mitochondria and lipid droplets in steatotic hepatocytes of chronic ethanol-treated rats: an immunohistochemical and electron microscopic study. J Mol Histol 2013; 44:311–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feldstein AE, Bailey SM. Emerging role of redox dysregulation in alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011; 15:421–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malhi H, Gores GJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of liver injury. Gastroenterology 2011; 6:1641–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lallès JP. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase: multiple biological roles in maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and modulation by diet. Nutr Rev 2010; 68:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]