The concept of neural plasticity accounts for the now well clarified brain ability to react to internal and external stimuli by transforming its structure and function. The translation of whatever experience in specific electrical signals that run through our neural networks induces a number of plastic changes at both functional and structural levels. In the last seventy year, a large amount of evidence demonstrated that plastic changes are the basis of the brain successful responding to the experience during developmental phases, in learning and memory processes throughout life, and even in the case of damage occurrence, in both neuroprotective and therapeutic ways. Indeed, plastic changes allow brain structure to reorganize in the presence of lesion, in order to completely or at least partially recover damaged functions (Gelfo et al., 2016; 2018; Gelfo, 2019).

In this frame, the reserve hypothesis has been postulated, by positing that lifespan complex experiences may provide the brain with an empowered structure able to cope better with the damage. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that individuals with different wealth of experiences show different ranges of symptoms in the case of neuronal injury or degeneration. This indication arose from the observation of patients affected by Alzheimer's disease, and then extended to include a wide spectrum of pathological conditions (Serra et al., 2018; Serra and Gelfo, 2019). The reserve concept has been described by factoring it in three components: the brain reserve regards cerebral structure, at molecular and supramolecular levels, and refers to the concept that individuals equipped with more structured brains are able to better deal with neurological damage; the cognitive reserve regards the cognitive functioning and accounts for the capacity of more efficiently utilizing the residual and vicariant cognitive functions to deal with neurological damage; finally, by merging the two previous ones, the neural reserve regards the ability to efficiently recruit alternative neuronal networks in cognitive performance. Recently, the brain maintenance concept has been inserted in this frame, to account for the modulatory effect of the experience on the brain capacity to maintain its cognitive integrity (Serra and Gelfo, 2019). Several factors work as “reserve-builders”: the cognitive factor involves all mentally demanding activities in which an individual may be engaged (education, job, leisure, etc.); the social factor involves social engagement (family, parentage, friendship, etc.); the physical factor involves lifestyle habits (physical activity, dietary regimen, etc.) (Gelfo et al., 2018; Gelfo, 2019).

Such three factors are modelled in the animal experimental paradigm of Environmental Enrichment (EE) that allows studying the effects of complex stimulations by strictly controlling the manipulated variables. In the EE paradigm, the cognitive factor is mimicked by rearing the animals in complex environments providing multifarious and ever-changing stimuli; the social factor is mimicked by rearing the animals in groups more numerous in comparison to the laboratory standards; the physical factor is mimicked by rearing the animals in cages larger than the standards, equipped with ladders and wheels, and eventually providing them with supplemented diets (Petrosini et al., 2009; Gelfo et al., 2018; Gelfo, 2019). Several studies (carried out both in healthy and pathological animals) demonstrated that the more or less prolonged exposure to an enriched environment is able to improve behavioural and cognitive performance and to potentiate brain structure. Namely, motor behavior, learning and memory processes, and executive functions have been found to be potentiated by EE (Petrosini et al., 2009; Gelfo, 2019). In correlation, EE has been demonstrated to potentiate brain structure, at both molecular and supramolecular levels (Angelucci et al., 2009; Gelfo et al., 2009; 2018).

The cerebellum stands as a structure highly involved in neuroplasticity processes, even throughout adult age. The tuning of successful responses to the ever-changing environmental conditions is mediated by the continuous remodeling of the neural circuitries that connect the cerebellum with the other cerebral areas, on the basis of complex synaptic rearrangements. Moreover, a relevant bulk of studies demonstrated the cerebellar capability to compensate lesion-induced deficits (Gelfo et al., 2011; 2016; Mitoma et al., 2020). At a structural level, cerebellum adaptability is mediated by a number of plastic rearrangements. Among them, great attention has been devoted to the ones involving Purkinje cell dendritic spines that exhibit heavy modifications in density and size, so regulating synaptic strength. Since Purkinje cell dendritic spines are the target of the afferent projections to cerebellar cortex, such rearrangements are consequences of the interactions with the environment and mediate the cerebellum-guided functional adaptations (De Bartolo et al., 2015; Gelfo et al., 2016; Mitoma et al., 2020).

On such a basis, the cerebellum appears one of the most suitable structures to study the effects of the exposure to EE and the development of a reserve that could be named cerebellar reserve.

As described above, in healthy animals the exposure to EE provokes improved behavioural and cognitive performances (Petrosini et al., 2009; Gelfo, 2019). By specifically investigating the cerebellar correlates of such functional advance (De Bartolo et al., 2015), it has been demonstrated that the long-term exposure (from weaning to adulthood) to multidimensional EE induces a significant increase of Purkinje cell dendritic spine density (number of spines per micrometer of dendritic length) and size (spine area, length, and head diameter). This synaptic rearrangement is found both in vermian region, primary involved in balance and locomotion, and in hemispherical regions, mainly recruited in complex motor tuning and cognitive processes. Such synaptogenesis is related to a potentiation of the cerebellar circuitries. Moreover, the spine widening indicates the reinforcement of post-synaptic area that supports the strengthening of functional response. Such Purkinje cell morphological rearrangement is accompanied by a significant increase in cerebellar brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression that triggers and supports any synaptic change (Angelucci et al., 2009).

Interestingly, the cerebellum appears as a powerfully reactive structure also in the case of damage occurrence. When submitted to a unilateral cerebellar ablation (hemicerebellectomy), the animals deprived of a half of the vermis and one entire hemisphere exhibit a large spectrum of typical postural and locomotor asymmetries, as well as deficits in complex motor behaviours and spatial learning and memory performances. However, after about three weeks, lesioned animals show an almost complete compensation of postural and locomotor symptoms, even though they never completely succeed in recovering complex motor behaviours and maintain deficits in spatial performance (Gelfo et al., 2016). In association to this functional framework, plastic rearrangements have been found in the spared hemivermis and hemisphere. Specifically, Purkinje cell spine size augments in both regions, although in a partially different manner. Namely, even if spine density decreases in the hemivermis and increases in the hemisphere, both patterns may be interpreted as aimed at maintaining an effective synaptic transmission in a homeostatic arrangement linked to the different connectivity of the two cerebellar regions. A diminished input to the hemivermis is indeed associated with the degeneration of those parallel fibers whose soma is ablated by the lesion. Conversely, an augmented input to the hemisphere is due to the wide functional rewiring from the other cortical and subcortical regions. Thus, both these homeostatic reactions appear to support the almost complete compensation of deficits shown by lesioned animals (Gelfo et al., 2016).

But what happens if the hemicerebellectomy is executed in previously enriched animals? At a functional level, pre-enriched animals exhibit postural and locomotor recovery at least one week before the standard-lesioned peers. Moreover, they succeed also in restoring complex motor behaviours and spatial learning and memory performance (Gelfo et al., 2016). At a morphological level, in pre-enriched animals Purkinje cells maintain the potentiated arrangement induced by the EE (see above) without showing most plastic rearrangements induced by the lesion (see above). This pattern supports the hypothesis that a morphological rearrangement aimed to homeostasis may be not needed in a brain previously strengthened by complex stimulations (Gelfo et al., 2016). Interestingly, a similar pattern has been found in relation to the BDNF expression in the spared hemicerebellum: the enhanced neurotrophin expression induced by the EE is maintained, without further rearrangement as consequence of the lesion. However, it is noteworthy to emphasize that BDNF expression in neocortex is not augmented in standard-lesioned animals, but is significantly augmented in the enriched ones. This enhanced BDNF expression is maintained in pre-enriched lesioned animals (Gelfo et al., 2011). In addition, the exposure to EE significantly enhances dendritic spine density in neocortex (Gelfo et al., 2009) and completely prevents the morphological shrinkage of fast-spiking striatal interneurons, which hemicerebellectomy induces in standard reared animals due to the interconnections between cerebellum and basal ganglia (Cutuli et al., 2011).

On the whole, the evidence summarized here supports the idea that being an extremely plastic structure the cerebellum implements adaptive reactions to any kind of experience, both in consequence of detrimental events – such as a lesion – and beneficial events – such as enriching environmental stimulations. Cerebellar structures carry out a number of rearrangements to successfully cope with the events, in order to maintain, reacquire, or promote the equilibrium status of neural circuitries. Anyway, the enriching experiences appear to be able to create a reserve that supports high-level functional performances in healthy subjects and an enhanced functional recovery in case of brain damage. Such cerebellar reserve works in synergy with the rearranged structure of the entire brain. It is noteworthy that the reported findings obtained in rodents with focal cerebellar lesions exposed to multidimensional environmental enrichment are in line with recent evidence obtained in different models. Namely, these studies demonstrated that the cerebellar reserve may be developed also following the exposure to unidimensional environmental stimulations, such as a prolonged motor training. Interestingly, such investigations showed that the cerebellum when potentiated by a reserve copes better also with a diffuse cerebellar injury, as observed in transgenic rodent models of ataxia. In fact, preventive motor training was reported to attenuate ataxic symptoms and promote Purkinje cell survival (Fucà et al., 2017; Chuang et al., 2019).

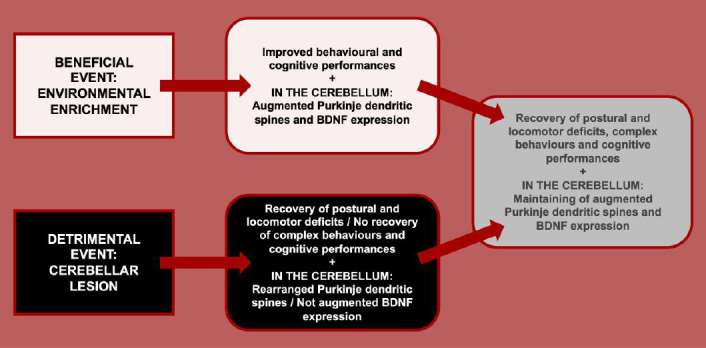

The frame described in the present manuscript (Figure 1) is developed on findings mainly obtained in animal studies. It is important to add that also human studies emphasize the cerebellar capacity to compensate the deficits caused by neural injury or degeneration. In fact, cerebellar patients partially compensate damage in case of acute focal lesions – provoked by trauma or stroke – or diffuse neuronal degeneration - due to metabolic, immune-mediated or neurodegenerative ataxias. The compensation may be mediated by the intact cerebellar regions outside the lesioned one, as well as by extracerebellar regions. It occurs in a period named “restorable stage”, associated with the reversal capacity of the intact cerebellar and extra-cerebellar networks, and precedes the exceeding of a neural degeneration threshold (“non-restorable stage”) (Mitoma et al., 2020). Anyway, as described above, numerous cognitive, social, and physical factors, acting as “reserve-builders” are able to modulate the brain capacity to cope with the damage. Nevertheless, studies specifically aimed to analyze the eventual potentiating action of environmental stimulations on cerebellar compensation capacity in humans are still lacking. Starting from the insight provided by Alzheimer's disease patients, in the last decades the effects of complex environmental stimulations have been studied in a large range of pathologies (neurodegenerative diseases, traumatic injuries, genetic disorders, etc.). Therefore, it is very surprising that similar studies have not been carried out in relation to the cerebellar pathologies, despite the well-known neuroplastic ability of the human cerebellum and the specific suggestions provided by the animal studies. Thus, it could be worthwhile to investigate in the cerebellar patients how previous life experiences may influence the efficacy level of the individual compensation capacity. Moreover, it could be worthwhile to investigate the eventual correlation between foregoing experiences and duration of the period in which treatments may be effective in restoring deficits (restorable stage of the pathology). Such investigations may be really relevant to schedule fine-tuned clinical interventions focused on potentiating individual cerebellar reserve capacities. Similar conclusions have been drawn up by a very recent review on the efficacy of non-invasive cerebellar stimulation (Billeri and Naro, 2021). According to the authors, the successful outcome of such methodology in the treatment of cerebellar dysfunctions of different origin depends on the residual functional reserve of the cerebellum, in total agreement with the perspective we are here proposing.

Figure 1.

The panel summarizes the main evidence on cerebellar reserve.

In the upper side, the effects of a beneficial factor – such as environmental enrichment – in animals’ performance and cerebellar structure and biology are enumerated. In the lower side, the effects of a detrimental factor – such as a cerebellar lesion – in animals’ performance and cerebellar structure and biology are enumerated. Finally, in the right side, the effects of the combination of previous exposure to environmental enrichment and successive cerebellar lesion in animals’ performance and cerebellar structure and biology are enumerated. BDNF: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

In conclusion, it appears of primary interest that future studies translate the here summarized evidence on cerebellar reserve from animals to human patients, in order to optimize the managing of cerebellar pathologies.

Additional file: Open peer review reports 1 (84.1KB, pdf) and 2 (82KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open peer reviewers: Valentina Cerrato, University of Turin, Italy; Antonino Naro, IRCCS Centro Neurolesi Bonino Pulejo, Italy.

P-Reviewers: Cerrato V, Naro A; C-Editors: Zhao M, Liu WJ, Qiu Y; T-Editor: Jia Y

References

- 1.Angelucci F, De Bartolo P, Gelfo F, Foti F, Cutuli D, Bossù P, Caltagirone C, Petrosini L. Increased concentrations of nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the rat cerebellum after exposure to environmental enrichment. Cerebellum. 2009;8:499–506. doi: 10.1007/s12311-009-0129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billeri L, Naro A. A narrative review on non-invasive stimulation of the cerebellum in neurological diseases. Neurol Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05187-1. oi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuang CS, Chang JC, Soong BW, Chuang SF, Lin TT, Cheng WL, Orr HT, Liu CS. Treadmill training increases the motor activity and neuron survival of the cerebellum in a mouse model of spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019;35:679–685. doi: 10.1002/kjm2.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutuli D, Rossi S, Burello L, Laricchiuta D, De Chiara V, Foti F, De Bartolo P, Musella A, Gelfo F, Centonze D, Petrosini L. Before or after does it matter? Different protocols of environmental enrichment differently influence motor, synaptic and structural deficits of cerebellar origin. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Bartolo P, Florenzano F, Burello L, Gelfo F, Petrosini L. Activity-dependent structural plasticity of Purkinje cell spines in cerebellar vermis and hemisphere. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220:2895–2904. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0833-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fucà E, Guglielmotto M, Boda E, Rossi F, Leto K, Buffo A. Preventive motor training but not progenitor grafting ameliorates cerebellar ataxia and deregulated autophagy in tambaleante mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;102:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelfo F. Does experience enhance cognitive flexibility? An overview of the evidence provided by the environmental enrichment studies. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:150. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gelfo F, De Bartolo P, Giovine A, Petrosini L, Leggio MG. Layer and regional effects of environmental enrichment on the pyramidal neuron morphology of the rat. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2009;91:353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfo F, Cutuli D, Foti F, Laricchiuta D, De Bartolo P, Caltagirone C, Petrosini L, Angelucci F. Enriched environment improves motor function and increases neurotrophins in hemicerebellar lesioned rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011;25:243–252. doi: 10.1177/1545968310380926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gelfo F, Florenzano F, Foti F, Burello L, Petrosini L, De Bartolo P. Lesion-induced and activity-dependent structural plasticity of Purkinje cell dendritic spines in cerebellar vermis and hemisphere. Brain Struct Funct. 2016;221:3405–3426. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1109-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelfo F, Mandolesi L, Serra L, Sorrentino G, Caltagirone C. The neuroprotective effects of experience on cognitive functions: evidence from animal studies on the neurobiological bases of brain reserve. Neuroscience. 2018;370:218–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitoma H, Buffo A, Gelfo F, Guell X, Fucà E, Kakei S, Lee J, Manto M, Petrosini L, Shaikh AG, Schmahmann JD. Consensus Paper. Cerebellar reserve: from cerebellar physiology to cerebellar disorders. Cerebellum. 2020;19:131–153. doi: 10.1007/s12311-019-01091-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrosini L, De Bartolo P, Foti F, Gelfo F, Cutuli D, Leggio MG, Mandolesi L. On whether the environmental enrichment may provide cognitive and brain reserves. Brain Res Rev. 2009;61:221–239. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serra L, Gelfo F, Petrosini L, Di Domenico C, Bozzali M, Caltagirone C. Rethinking the reserve with a translational approach: novel ideas on the construct and the interventions. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;65:1065–1078. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serra L, Gelfo F. What good is the reserve? A translational perspective for the managing of cognitive decline. Neural Regen Res. 2019;14:1219–1220. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.251328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.