Abstract

Background

Atopic eczema (AE), also known as atopic dermatitis, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes significant burden. Phototherapy is sometimes used to treat AE when topical treatments, such as corticosteroids, are insufficient or poorly tolerated.

Objectives

To assess the effects of phototherapy for treating AE.

Search methods

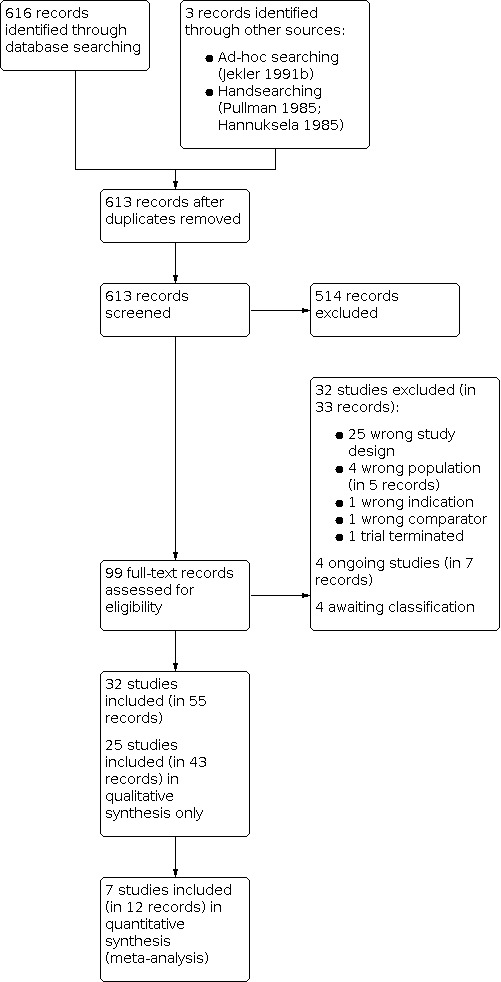

We searched the Cochrane Skin Specialised Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and ClinicalTrials.gov to January 2021.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials in adults or children with any subtype or severity of clinically diagnosed AE. Eligible comparisons were any type of phototherapy versus other forms of phototherapy or any other treatment, including placebo or no treatment.

Data collection and analysis

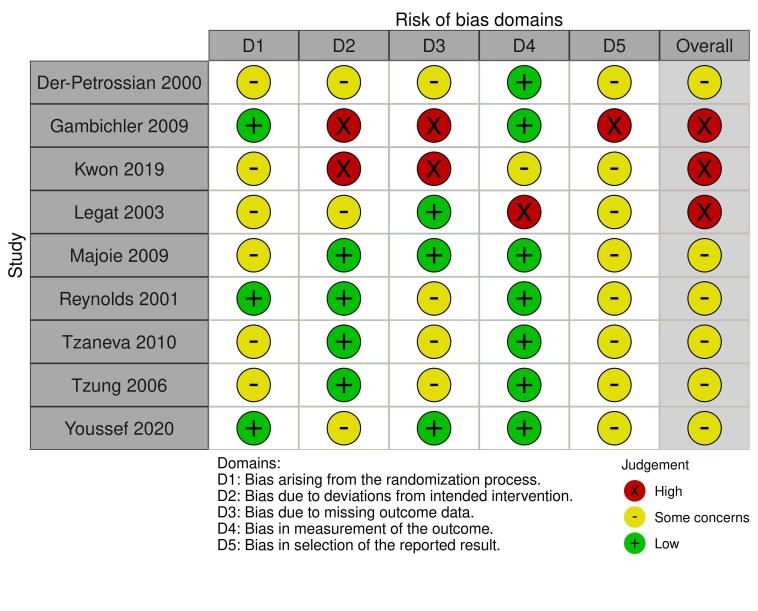

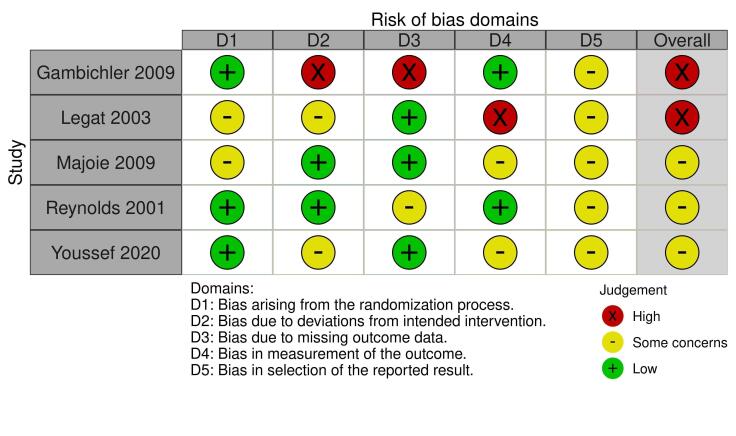

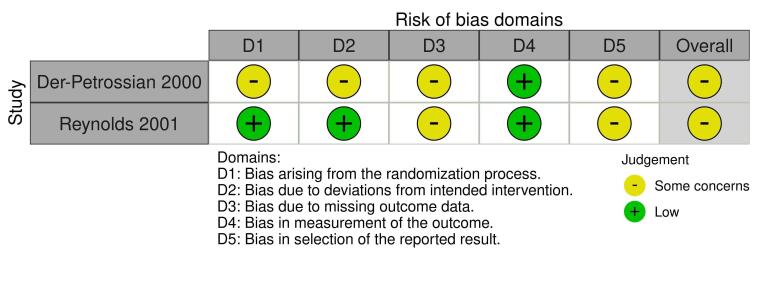

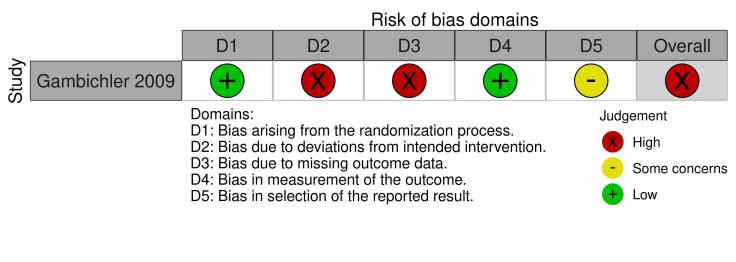

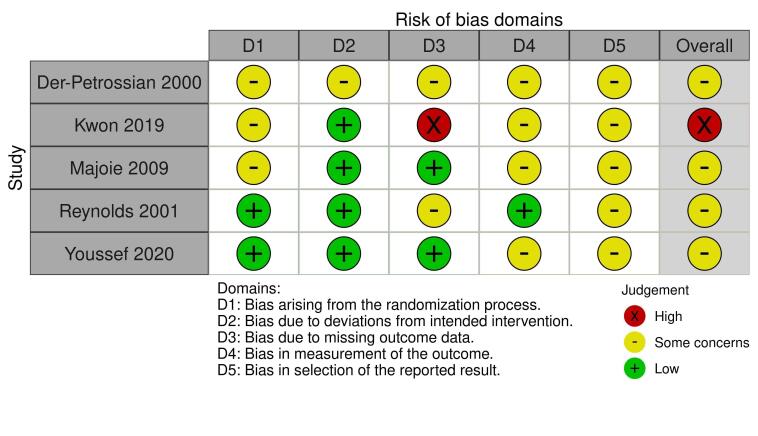

We used standard Cochrane methodology. For key findings, we used RoB 2.0 to assess bias, and GRADE to assess certainty of the evidence. Primary outcomes were physician‐assessed signs and patient‐reported symptoms. Secondary outcomes were Investigator Global Assessment (IGA), health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), safety (measured as withdrawals due to adverse events), and long‐term control.

Main results

We included 32 trials with 1219 randomised participants, aged 5 to 83 years (mean: 28 years), with an equal number of males and females. Participants were recruited mainly from secondary care dermatology clinics, and study duration was, on average, 13 weeks (range: 10 days to one year). We assessed risk of bias for all key outcomes as having some concerns or high risk, due to missing data, inappropriate analysis, or insufficient information to assess selective reporting.

Assessed interventions included: narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB; 13 trials), ultraviolet A1 (UVA1; 6 trials), broadband ultraviolet B (BB‐UVB; 5 trials), ultraviolet AB (UVAB; 2 trials), psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA; 2 trials), ultraviolet A (UVA; 1 trial), unspecified ultraviolet B (UVB; 1 trial), full spectrum light (1 trial), Saalmann selective ultraviolet phototherapy (SUP) cabin (1 trial), saltwater bath plus UVB (balneophototherapy; 1 trial), and excimer laser (1 trial). Comparators included placebo, no treatment, another phototherapy, topical treatment, or alternative doses of the same treatment.

Results for key comparisons are summarised (for scales, lower scores are better):

NB‐UVB versus placebo/no treatment

There may be a larger reduction in physician‐assessed signs with NB‐UVB compared to placebo after 12 weeks of treatment (mean difference (MD) ‐9.4, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐3.62 to ‐15.18; 1 trial, 41 participants; scale: 0 to 90). Two trials reported little difference between NB‐UVB and no treatment (37 participants, four to six weeks of treatment); another reported improved signs with NB‐UVB versus no treatment (11 participants, nine weeks of treatment).

NB‐UVB may increase the number of people reporting reduced itch after 12 weeks of treatment compared to placebo (risk ratio (RR) 1.72, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.69; 1 trial, 40 participants). Another trial reported very little difference in itch severity with NB‐UVB (25 participants, four weeks of treatment).

The number of participants with moderate to greater global improvement may be higher with NB‐UVB than placebo after 12 weeks of treatment (RR 2.81, 95% CI 1.10 to 7.17; 1 trial, 41 participants).

NB‐UVB may not affect rates of withdrawal due to adverse events. No withdrawals were reported in one trial of NB‐UVB versus placebo (18 participants, nine weeks of treatment). In two trials of NB‐UVB versus no treatment, each reported one withdrawal per group (71 participants, 8 to 12 weeks of treatment).

We judged that all reported outcomes were supported with low‐certainty evidence, due to risk of bias and imprecision. No trials reported HRQoL.

NB‐UVB versus UVA1

We judged the evidence for NB‐UVB compared to UVA1 to be very low certainty for all outcomes, due to risk of bias and imprecision. There was no evidence of a difference in physician‐assessed signs after six weeks (MD ‐2.00, 95% CI ‐8.41 to 4.41; 1 trial, 46 participants; scale: 0 to 108), or patient‐reported itch after six weeks (MD 0.3, 95% CI ‐1.07 to 1.67; 1 trial, 46 participants; scale: 0 to 10). Two split‐body trials (20 participants, 40 sides) also measured these outcomes, using different scales at seven to eight weeks; they reported lower scores with NB‐UVB. One trial reported HRQoL at six weeks (MD 2.9, 95% CI ‐9.57 to 15.37; 1 trial, 46 participants; scale: 30 to 150). One split‐body trial reported no withdrawals due to adverse events over 12 weeks (13 participants). No trials reported IGA.

NB‐UVB versus PUVA

We judged the evidence for NB‐UVB compared to PUVA (8‐methoxypsoralen in bath plus UVA) to be very low certainty for all reported outcomes, due to risk of bias and imprecision. There was no evidence of a difference in physician‐assessed signs after six weeks (64.1% reduction with NB‐UVB versus 65.7% reduction with PUVA; 1 trial, 10 participants, 20 sides). There was no evidence of a difference in marked improvement or complete remission after six weeks (odds ratio (OR) 1.00, 95% CI 0.13 to 7.89; 1 trial, 9/10 participants with both treatments). One split‐body trial reported no withdrawals due to adverse events in 10 participants over six weeks. The trials did not report patient‐reported symptoms or HRQoL.

UVA1 versus PUVA

There was very low‐certainty evidence, due to serious risk of bias and imprecision, that PUVA (oral 5‐methoxypsoralen plus UVA) reduced physician‐assessed signs more than UVA1 after three weeks (MD 11.3, 95% CI ‐0.21 to 22.81; 1 trial, 40 participants; scale: 0 to 103). The trial did not report patient‐reported symptoms, IGA, HRQoL, or withdrawals due to adverse events.

There were no eligible trials for the key comparisons of UVA1 or PUVA compared with no treatment.

Adverse events

Reported adverse events included low rates of phototoxic reaction, severe irritation, UV burn, bacterial superinfection, disease exacerbation, and eczema herpeticum.

Authors' conclusions

Compared to placebo or no treatment, NB‐UVB may improve physician‐rated signs, patient‐reported symptoms, and IGA after 12 weeks, without a difference in withdrawal due to adverse events. Evidence for UVA1 compared to NB‐UVB or PUVA, and NB‐UVB compared to PUVA was very low certainty. More information is needed on the safety and effectiveness of all aspects of phototherapy for treating AE.

Keywords: Adult; Child; Female; Humans; Male; Dermatitis, Atopic; Dermatitis, Atopic/drug therapy; Eczema; Phototherapy; Quality of Life; Ultraviolet Therapy

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of light therapy for treating atopic eczema (also known as eczema or atopic dermatitis)?

Key messages

Narrowband (NB) ultraviolet B (UVB), compared to placebo (a sham treatment), may improve eczema severity (including itch) and may not affect the number of people leaving a study because of unwanted effects.

We were unable to confidently draw conclusions for other phototherapy (light therapy) treatments.

Future research needs to assess longer term effectiveness and safety of NB‐UVB and other forms of phototherapy for eczema.

What is eczema?

Eczema is a condition that results in dry, itchy patches of inflamed skin. Eczema typically starts in childhood, but can improve with age. Eczema is caused by a combination of genetics and environmental factors, which lead to skin barrier dysfunction. Eczema can negatively impact quality of life, and the societal cost is significant.

How is eczema treated?

Eczema treatments are often creams or ointments that reduce itch and redness, applied directly to the skin. If these are unsuccessful, systemic medicines that affect the whole body, or phototherapy are options. Phototherapy can be UVB, ultraviolet A (UVA), or photochemotherapy (PUVA), where phototherapy is given alongside substances that increase sensitivity to UV light.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out whether phototherapy was better than no treatment or other types of treatment for treating eczema, and whether it caused unwanted effects.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated phototherapy compared with no treatment, placebo, other forms of phototherapy, or another type of eczema treatment. Studies could include people of all ages, who had eczema diagnosed by a healthcare professional.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies, and rated our confidence in the evidence.

What did we find?

We found 32 studies, involving 1219 people with eczema (average age: 28 years), who were recruited from dermatology clinics. Most studies assessed people with skin type II to III (which is classed as white to medium skin colour), and moderate to severe eczema, with which they had lived for many years. Studies included similar numbers of males and females.

The studies were conducted in Europe, Asia, and Egypt (setting was not reported by seven studies), and lasted, on average, for 13 weeks. Almost half of the studies reported their source of funding; two were linked to commercial sponsors.

Our included studies mostly assessed NB‐UVB, followed by UVA1, then broadband ultraviolet B; fewer studies investigated other types of phototherapy. The studies compared these treatments to placebo, or no treatment, another type of phototherapy, different doses of the same sort of phototherapy, or other eczema treatments applied to the skin or taken by tablet.

None of the studies investigated excimer lamp (a source of UV radiation) or heliotherapy (the use of natural sunlight), that were other light therapies in which we were interested.

What are the main results of our review?

When compared to placebo, NB‐UVB may:

‐ improve signs of eczema assessed by a healthcare professional (1 study, 41 people);

‐ increase the number of people reporting less severe itching (1 study, 41 people);

‐ increase the number of people reporting moderate or greater improvement of eczema, measured by the Investigator Global Assessment scale (IGA), a 5‐point scale that measures improvement in eczema symptoms (1 study, 40 people); and

‐ have no effect on the rate of people withdrawing from treatment due to unwanted effects (3 studies, 89 people).

None of the studies assessing NB‐UVB against placebo measured health‐related quality of life.

We do not know if NB‐UVB (compared with UVA1 or PUVA) or UVA1 (compared with PUVA) has an effect on the following:

‐ signs of eczema assessed by a healthcare professional;

‐ patient‐reported eczema symptoms;

‐ IGA;

‐ health‐related quality of life; and

‐ withdrawals due to unwanted effects.

This is because either we are not confident in the evidence, or they were not reported.

We did not identify any studies that investigated UVA1 or PUVA compared with no treatment.

Some studies reported that phototherapy caused some unwanted effects, including skin reactions or irritation, UV burn, worsening of eczema, and skin infections. However, these did not occur in most people.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Our confidence in the evidence is limited, mainly because only a few studies could be included in each comparison, and the studies generally involved only small numbers of people.

How up to date is this evidence?

The evidence is up to date to January 2021.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ NB‐UVB compared to placebo for atopic eczema.

| NB‐UVB compared to placebo for atopic eczema | ||||||

| Patient or population:atopic eczema Setting:outpatient or not stated (Egypt; Korea; Taiwan; UK) Intervention:NB‐UVB Comparison:placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with NB‐UVB | |||||

| Physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs assessed with: mean reduction in total disease activity score: lower score is better Scale from: 0 to 90 follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs was ‐0.4 | MD 9.4 lower (15.18 lower to 3.62 lower) | ‐ | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | This result is from Reynolds 2001. Three other studies reported this outcome but did not report any dispersion data. In Kwon 2019, EASI score was 2.1 (n=6) with NB‐UVB versus 3.6 (n=5) with no treatment (after 9 weeks). In Tzung 2005 (split‐body study, 6 weeks, n=12), the side treated with NB‐UVB had a mean reduction of 56% in EASI versus 54% with no treatment. In Youssef 2020 (n=25), SCORAD reduced by 50.8% with NB‐UVB versus 48.6% with no treatment (4 weeks of treatment). |

| Patient‐reported changes in symptoms assessed with: number of participants reporting a reduction in itch on VAS follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 526 per 1000 | 905 per 1000 (579 to 1000) | RR 1.72 (1.10 to 2.69) | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,c | This result is from Reynolds 2001 (19 of 21 participants with NB‐UVB versus 10 of 19 with placebo). One other study reported this outcome but did not report any dispersion data. Youssef 2020 reported a ‐55.7% change in VAS itch after 4 weeks of treatment with NB‐UVB (n=13), compared to a ‐53.6% change in VAS itch in patients with no treatment (n=12). |

| Investigator Global Assessment (short‐term) assessed with: number of participants with moderate or greater improvement follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | 211 per 1000 | 592 per 1000 (232 to 1000) | RR 2.81 (1.10 to 7.17) | 41 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,d | This result is from Reynolds 2001 (13 of 22 participants with NB‐UVB versus 4 of 19 with placebo). Long‐term data (measured at 6 months, 3 months post‐treatment) showed a similar result (RR 1.89, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.89, n=35). |

| Health‐related quality of life ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the studies measured this outcome | ||

| Safety: withdrawals due to adverse events (short‐term) assessed with: number of participants follow‐up: range 8 weeks to 12 weeks | See comments box for narrative description. | 89 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,e | In Reynolds 2001, one patient in each group withdrew because of burning (measured up to week 12, n=41). In Youssef 2020, two patients withdrew because of adverse events: one patient in the NB‐UVB group (phototoxic reaction) and one patient in the glycerol 85% group (severe irritation) (measured up to week 8, n=30). Kwon 2019 reported no withdrawals in both groups (measured up to week 9, n=18). | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425206404975446768. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level due to risk of bias. Overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' in Reynolds 2001 due to concerns with missing outcome data (13% of participants withdrew but numbers were similar in both groups) and selection of the reported results (no protocol available). Kwon 2019 was considered high risk overall (deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data). In Tzung 2005, overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' (concerns in all domains apart from measurement of outcome). In Youssef 2020, overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' (deviations from intended interventions and selection of reported result). b Downgraded one level due to imprecision ‐ small sample sizes. c Downgraded one level due to risk of bias. Overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' in Reynolds 2001 due to concerns with missing outcome data (13% of participants withdrew but numbers were similar in both groups) and selection of the reported results (no protocol available). There were 'some concerns' with Youssef 2020 due to deviations from intended interventions, measurement of the outcome and selection of reported result. d Downgraded one level due to risk of bias. Overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' in Reynolds 2001 due to concerns with missing outcome data (13% of participants withdrew but numbers were similar in both groups) and selection of the reported results (no protocol available). e Downgraded one level due to risk of bias. Overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' in Reynolds 2001 due to concerns with missing outcome data (13% of participants withdrew but numbers were similar in both groups) and selection of the reported results (no protocol available). Kwon 2019 was considered 'some concerns' overall (deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data). In Tzung 2005, overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' (concerns in all domains). In Youssef 2020, overall risk of bias was 'some concerns' (Measurement of outcome and selection of reported result).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ NB‐UVB compared to UVA1 for atopic eczema.

| NB‐UVB compared to UVA1 for atopic eczema | ||||||

| Patient or population:atopic eczema Setting:not stated (Germany; the Netherlands) Intervention:NB‐UVB Comparison:UVA1 | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with UVA1 | Risk with NB‐UVB | |||||

| Physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs (short‐term) assessed with: SASSAD: lower score is better Scale from: 0 to 108 follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | The mean physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs (short‐term) was 22 | MD 2 lower (8.41 lower to 4.41 higher) | ‐ | 46 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | This result is from Gambichler 2009. Two split‐body studies could not be included due to insufficient data. Legat 2003 (n=7) reported median Costa (scale 0‐123) score of 40 (range 26 to 89) and 58 (27 to 89) and median Leicester score (maximum 162) of 23 (12 to 56) and 52 (14 to 69) after 7 weeks with NB‐UVB and UVA1, respectively. Majoie 2009 reported mean Leicester sign score (scale 0‐108) of 9.2 and 11.6 in 26 body‐halves (13 participants) treated with NB‐UVB and UVA1, respectively (8 weeks). |

| Patient‐reported changes in symptoms assessed with: VAS for itch Scale from: 0 to 10 follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | The mean patient‐reported changes in symptoms was 4.2 | MD 0.3 higher (1.07 lower to 1.67 higher) | ‐ | 46 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c | This result is from Gambichler 2009. Two split‐body studies could not be included due to insufficient data. After 7 weeks of treatment, seven participants in Legat 2003 reported a median VAS itch (scale 0‐10) of 2 (0.1 to 8.5) for their body‐half that was treated with NB‐UVB, compared to 3.9 (0.2 to 8.4) for the UVA1 treated body‐half. At week 8, Majoie 2009 showed a mean itch VAS of 2.9 and 3.6 for NB‐UVB and UVA1 in 13 participants, respectively. |

| Investigator Global Assessment ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Health‐related quality of life assessed with: German Skindex‐29: lower score is better Scale from: 30 to 150 follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | The mean health‐related quality of life was 69.8 | MD 2.9 higher (9.57 lower to 15.37 higher) | ‐ | 46 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,d | This result is from Gambichler 2009. |

| Safety: withdrawal due to adverse events assessed with: number of participants follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | See comments box for narrative description (right). | 13 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe,f | Majoie 2009 was the only study that reported the number of withdrawals due to adverse events. There were no withdrawals due to adverse events in this split‐body trial (13 participants, 26 sides). | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425498097763422661. | ||||||

a Downgraded by two levels due to very serious risk of bias. High risk of bias overall as there was high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (did not follow intention to treat analysis, excluded participants due to inefficiency), missing outcome data (45% missing) and selection of reported results (retrospective clinical trial register entry which specified SCORAD been used instead). Legat 2003 was also rated high risk of bias overall (measurement of the outcome). Majoie 2009 had some concerns (randomisation process, selection of the reported result). b Downgraded by one level due to serious imprecision ‐ small sample sizes. c Downgraded by two levels due to very serious risk of bias. High risk of bias overall as there was high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (did not follow intention to treat analysis, excluded participants due to inefficiency) and missing outcome data (45% missing). Legat 2003 was also rated high risk of bias overall (measurement of the outcome). Majoie 2009 had some concerns (randomisation process, measurement of the outcome, selection of the reported result). d Downgraded by two levels due to very serious risk of bias. High risk of bias overall as there was high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (did not follow intention to treat analysis, excluded participants due to inefficiency) and missing outcome data (40% missing). e Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias. Majoie 2009 had some concerns (randomisation process, selection of the reported result). f Downgraded by two levels due to very serious imprecision ‐ single study with very small sample size.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table ‐ NB‐UVB compared to PUVA for atopic eczema.

| NB‐UVB compared to PUVA for atopic eczema | ||||||

| Patient or population:atopic eczema Setting:not stated Intervention:NB‐UVB Comparison:PUVA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PUVA | Risk with NB‐UVB | |||||

| Physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs assessed with: percentage reduction in modified SCORAD follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | See comments box for narrative description. | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | Data was only presented on a graph and it wasn't clear if standard deviations were shown. At week 6, a 64.10% percentage reduction in SCORAD was seen in the NB‐UVB treated body‐half, compared to a similar percentage reduction of 65.7% in the body‐half treated with PUVA. This is a split‐body study where the number of participants in the study was 10 ‐ but there were 20 'sides' analysed. | ||

| Patient‐reported changes in symptoms ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Investigator Global Assessment assessed with: number of participants with marked improvement or complete remission follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | 900 per 1000 | 900 per 1000 (539 to 986) | OR 1.00 (0.13 to 7.89) | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,c | This is a split‐body study where the number of participants in the study was 10 ‐ but there were 20 'sides' analysed (which has been adjusted for in the analysis). |

| Health‐related quality of life ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Safety: withdrawal due to adverse events assessed with: number of participants follow‐up: mean 6 weeks | See comments box for narrative description (right). | 20 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,d | There were no severe adverse events and no withdrawals due to adverse events in this split‐body study (10 participants, 20 sides). | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425498309567386282. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias. Some concerns in all domains apart from measurement of the outcome which was considered low risk of bias. b Downgraded two levels due to very serious imprecision (small sample size; n=10 participants, 20 sides). c Downgraded two levels due to very serious imprecision. Small sample size (n=10 participants, 20 sides) and a wide 95% CI. d Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias. Some concerns in all domains.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings table ‐ UVA1 compared to PUVA for atopic eczema.

| UVA1 compared to PUVA for atopic eczema | ||||||

| Patient or population:atopic eczema Setting:outpatient (Austria) Intervention:UVA1 Comparison:PUVA | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with PUVA | Risk with UVA1 | |||||

| Physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs assessed with: SCORAD: lower score is better Scale from: 0 to 103 follow‐up: mean 3 weeks | The mean physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs was 28.8 | MD 11.3 higher (0.21 lower to 22.81 higher) | ‐ | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | |

| Patient‐reported changes in symptoms ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Investigator Global Assessment ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Health‐related quality of life ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| Safety: withdrawals due to adverse events ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425498095256539586. | ||||||

a Downgraded one level due to serious risk of bias. Some concerns overall in randomisation, missing outcome data, and selection of the reported result. b Downgraded by two levels due to very serious imprecision ‐ small sample size and wide 95% CI.

Background

Description of the condition

Atopic eczema, also known as atopic dermatitis, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that causes a significant burden to people with the condition and society. Atopic eczema can have a relapsing‐remitting or a continuous disease course. The clinical presentation is characterised by xerosis (dry skin), pruritus, and flaky, excoriated "eczematous" lesions (Weidinger 2016). Atopic eczema is diagnosed clinically by its signs and symptoms, and its distribution, which varies in different age groups (Spergel 2003). Diagnosis is based on the presence of other atopic diseases, like asthma. In research settings, the most commonly used diagnostic criteria are the Hanifin and Rajka criteria (Hanifin 1980), and the UK Working Party Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis (Williams 1994).

The prevalence of atopic eczema is reported to be up to 20% in children, and between 7% and 10% in adults, and may be increasing (De Lusignan 2020; Flohr 2014). Often, atopic eczema manifests at infancy, but it can start at any age. A cross‐sectional survey of 1760 children with atopic eczema found that 84% suffered from mild disease; 14% from moderate, and 2% from severe atopic eczema (Emerson 1998). Typically, the condition improves during childhood, with more than 50% of childhood atopic eczema resolving by adolescence (Williams 2005). However, some aspects of skin barrier and immune dysfunction may persist into adulthood (Abuabara 2018).

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) uses consistent measurement tools to study the prevalence of atopic eczema in children 6 to 7 years old, and 13 to 14 years old. One study within this research programme, examining time trends in the prevalence of atopic eczema, found a decreased prevalence of atopic eczema in developed countries, especially in Northwest Europe, between 2001 and 2003, compared to results from an earlier study that was conducted between 1994 and 1995. On the other hand, they found an increased prevalence, particularly for the younger age group, in many formerly low‐prevalence, low‐income countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia (Odhiambo 2009; Williams 2008). This variation in reported prevalence over time, and between different regions, suggests that disease prevalence is influenced by environmental factors. A large epidemiological study, using a UK primary care research database of 3.85 million children and adults, showed that the incidence of atopic eczema was higher in people with Black and Asian ethnicity than in white ethnic groups (De Lusignan 2020). A greater incidence of atopic eczema was seen in children younger than two years old with higher socioeconomic status, but for all other age groups, higher socioeconomic status was associated with a lower incidence of the condition. Both incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema are higher in urban areas (De Lusignan 2020; Schram 2010). It seems that environmental factors play a role during early life, as a relatively higher atopic eczema prevalence is seen in children from immigrants who moved from a low‐prevalence country to a country with higher prevalence (Martin 2013). The strongest determinant of atopic eczema is a positive family history (i.e. genetics (Apfelbacher 2011)).

The pathophysiology of atopic eczema is complex, and includes multiple interactions between genetic, immune, and external factors (Stefanovic 2020). It involves defects in epidermal structure and barrier dysfunction, alterations in cell‐mediated immune responses and immunoglobulin E‐mediated hypersensitivity (Weidinger 2016). An underlying genetic predisposition is identified with the discovery of mutations in the gene coding for the skin barrier protein, filaggrin (Palmer 2006). However, filaggrin mutations do not occur in all people with atopic eczema, so other genes and environmental factors seem to play an important role in its pathophysiology. The exposome is the total amount of external factors that an individual is exposed to throughout their lifetime (Stefanovic 2020). Exposomal influences play an important role in atopic eczema pathogenesis, and can be categorised into nonspecific exposures (e.g. human and natural factors), specific exposures (environmental factors, e.g. diet, allergens, humidity, ultraviolet radiation, pollution, and water hardness), and internal exposures (e.g. microbiota of the skin and gut, and host cell interaction (Stefanovic 2020)).

Atopic eczema causes a significant burden to both the person with the condition and their families, and it has been found that an increase in the condition's severity can result in lower quality of life, anxiety, and depression (Maksimović 2012). In addition, atopic eczema has important effects on society due to high medical costs, psychosocial effects, and co‐morbidities (Mancini 2008). The Global Burden of Disease Study, providing annually updated numbers on disease‐related morbidity and mortality worldwide, showed that atopic eczema disease burden, as measured by disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs), ranks fifteenth among all nonfatal diseases, and has the highest disease burden of all skin diseases (Laughter 2020). The worldwide DALY rate was 123.31 per 100,000 (95% uncertainty interval 66.79 to 205.17) in 2017 (Laughter 2020). The outcomes of the Cochrane Skin Prioritisation Exercise 2020 showed that the total number of DALYs for atopic eczema in 2017 was 9,003,374 (Cochrane Skin 2020a).

The main physician‐assessed outcome measures are the EASI (Eczema Area and Severity Index) score (Ricci 2009); the SCORAD (severity SCORing of Atopic Dermatitis) Index, which also includes a self‐assessment component, the Subjective SCORAD (Kunz 1997); the SASSAD (Six Area Six Sign Atopic Dermatitis Severity) score (Charman 2002); and Costa's Simple Scoring System (Costa (Costa 1989)). Subjective tools used for self‐assessment are the POEM (Patient‐Oriented Eczema Measure) Scale (Charman 2004); the PO‐SCORAD (Patient‐Oriented SCORAD (Stalder 2011)); and the SA‐EASI (Self‐Administered Eczema Area and Severity Index) Rating Scale (Housman 2002). The Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative reached consensus that the EASI score should be the core instrument used for clinician‐reported signs; POEM and NRS‐11 (Numeric Rating Scale, 11‐point scale for peak itch over past 24 hours) should be used for self‐reported symptoms; RECAP (Recap of Atopic Eczema (Howells 2020)) or ADCT (Atopic Dermatitis Control Test (Simpson 2019)) should be used for long‐term control; and the DLQI (Dermatology Life Quality Index (Finlay 1994)), should be used for quality of life assessment (Schmitt 2014; Spuls 2017).

The severity of atopic eczema is variable, with symptoms ranging from mild disease with localised redness and localised involvement, to moderate to severe disease characterised by more generalised involvement of the whole body, with widespread redness, oozing, crusting, and secondarily infected lesions. Assessment of clinical severity is based on both objective clinical signs and subjective symptoms, such as itch and loss of sleep (Schmitt 2014). The EASI score corresponds to disease severity as follows: 0 = clear; 0.1 to 1.0 = almost clear; 1.1 to 7.0 = mild; 7.1 to 21.0 = moderate; 21.1 to 50.0 = severe; 50.1 to 72.0 = very severe (Barbarot 2016).

Description of the intervention

For people with moderate to severe atopic eczema, for whom topical treatments, including corticosteroids and emollients, are insufficient, systemic immunomodulating medication, phototherapy, or photochemotherapy are therapeutic options. Photochemotherapy is a subtype of phototherapy, which is defined as the use of phototherapy combined with adjuvant ultraviolet light‐activated drug photosensitisers. Several types of phototherapy are beneficial for disease control in people with atopic eczema. These include: broadband ultraviolet B (BB‐UVB; wavelength 280 nm to 315 nm); narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB; wavelength 311 nm to 313 nm); ultraviolet A (UVA; wavelength 315 nm to 400 nm); ultraviolet A1 (UVA1; wavelength 340 nm to 400 nm); cold‐light UVA1 (containing a cooling system eliminating wavelengths greater than 530 nm, decreasing the heat load); ultraviolet AB (UVAB; wavelength 280 nm to 400 nm); full‐spectrum light (wavelength 320 nm to 500 nm, including UVA, visible, and infrared light); saltwater bath plus UVB (balneophototherapy); coal tar plus UVB (Goeckerman therapy); and excimer laser and excimer lamp (generating radiation in the ultraviolet B range (Garritsen 2014)). Photochemotherapy includes treatment with psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) and khellin plus UV. Phototherapy is usually administered in institutional settings, but for certain types of phototherapy, home phototherapy is also available.

Ultraviolet B (UVB)

UVB phototherapy can be administered using different wavelengths of emission. BB‐UVB lamps deliver ultraviolet radiation in the range of 280 nm to 315 nm, while NB‐UVB lamps deliver radiation of a much narrower spectrum, between 311 nm and 313 nm. UVB absorption occurs mainly through chromophores in the epidermis and superficial dermis (Weichenthal 2005). In order to increase the effectiveness of UVB therapy, and thereby, reduce UV exposure and risks, UVB treatment is often combined with topical agents (Mahrle 1987).

For psoriasis, it was shown that wavelengths around 311 nm were more effective than broad‐spectrum UVB, which led to the development of NB‐UVB lamps, which emit selective UVB spectra in the range of 311 nm to 313 nm (Fischer 1976; Parrish 1981). While the equivalent action spectra studies are not available for atopic eczema, NB‐UVB is now the most established and widely used form of phototherapy for the treatment of a wide range of other skin diseases, including atopic eczema (Herzinger 2016; Honig 1994; Van Weelden 1988; Vermeulen 2020). NB‐UVB devices contain fluorescent lamps emitting UVB in the 311 nm to 313 nm range (Van Weelden 1988). Although much less widely available in current times, devices used for BB‐UVB emit wavelengths in both the UVB range (280 nm to 315 nm, approximately two‐thirds of the output) and the UVA range (320 nm to 400 nm, approximately one‐third of the output (Jaleel 2019)).

The starting dose of UVB phototherapy is established by determining the person’s minimal erythema dose (MED), and basing treatment on that (e.g. 70% MED as first dose), or it is based on the person’s Fitzpatrick skin phototype (a system that classifies skin type by its reaction to exposure to sunlight). After treatment initiation, doses are gradually increased to 2000 mJ/cm2 to 5000 mJ/cm2, or to the maximum tolerated dose (Ibbotson 2004). Dose increments usually vary between 5% and 40% of the last dose used, most often in 10% to 20% increments. Treatment frequency varies from two to five times per week. Each treatment lasts from seconds at the onset of treatment, to minutes, depending on the type of device used. Guidelines on the dosimetry of NB‐UVB have mainly been published for psoriasis, but the same dosing protocols are often used for atopic eczema (Beani 2010; Ibbotson 2004; Menter 2010; Sidbury 2014; Spuls 2004). UVB phototherapy can also be administered in the person's home, described as home phototherapy.

BB‐UVB is sometimes combined with topical crude coal tar, in a regimen called Goeckerman therapy. This therapy was first reported by Goeckerman in 1925 for the treatment of psoriasis, but can also be used for the treatment of severe atopic eczema (Dennis 2013).

Balneotherapy (saltwater immersion) can also be combined with UVB (balneophototherapy). The addition of UVB phototherapy to balneotherapy may enhance the anti‐inflammatory effect of thermal spring water. UVB can be administered simultaneously, or after saltwater immersion (Huang 2018).

Ultraviolet A (UVA)

The different types of UVA phototherapies can be sub‐categorised into conventional UVA (315 nm to 400 nm) and UVA1 (340 nm to 400 nm). Conventional UVA requires longer exposure times for effective doses. However, as UVA1 equipment is relatively expensive to buy and maintain, conventional UVA lamps can still be used as a less costly alternative to UVA1, as 90% of their emission is in the UVA1 range (Darsow 2010; Legat 2003; Zandi 2012).

UVA1 lamps that eliminate ultraviolet A2 (UVA2; 320 nm to 340 nm) wavelengths from their emission spectrum have enabled higher doses to be delivered, while minimising risk of adverse effects, notably erythema. In practice, metal halide sources are required to achieve such high doses, as fluorescent sources at much lower irradiance are unable to achieve this. UVA1 can be administrated at a high dose (HD; 80 J/cm2 to 130 J/cm2), medium dose (MD; 40 J/cm2 to 80 J/cm2), or low dose (LD; less than 40 J/cm2), with sessions lasting from 10 minutes to one hour (Darsow 2010; Legat 2003). Dosimetry has not yet been standardised internationally, but based on reports of the approximate dose needed to produce minimum erythema and treatment durations, it can be assumed that low, medium, and high doses are approximately equivalent between centres; although quoted dosages are unlikely to be precisely equivalent (Dawe 2003). Efficacy of high dose UVA1 has been reported in acute flares of severe atopic eczema, although the specific phenotype of atopic eczema that responds most effectively has not been evaluated, and is a matter for further study (Krutmann 1998).

For people receiving high dose UVA1, UVA1 cold light lamps that filter infrared radiation with a cooling ventilation machine, enable treatment to be delivered more comfortably, without the high levels of heat produced during high dose UVA1 exposure (Von Kobyletzki 1999b).

UVAB radiation includes wavelengths of both UVA and ultraviolet B (UVB), given either simultaneously by a single device (such as Metec Helarium©), or in subsequent emissions. Its use for atopic eczema was initiated by Jekler and Larkö, but it is rarely used today, as it has largely been replaced with other UV‐based phototherapies (Grundmann 2012; Jekler 1990).

Full spectrum light (FSL) is an alternative modality of phototherapy, generating the full spectrum of light with a continuous wavelength ranging from 320 nm to 5000 nm, usually in combination with emollients (Byun 2011).

Photochemotherapy

Photochemotherapy uses ultraviolet light‐activated drug photosensitisers combined with phototherapy. It typically uses a systemic drug photosensitiser combined with phototherapy. In photochemotherapy, the anti‐inflammatory, anti‐proliferative, and immunosuppressive effects only occur in the skin on irradiation, when the drug absorbs ultraviolet light. The most common form of photochemotherapy is psoralen‐UVA (PUVA); during which the administration of UVA is combined with psoralen as the photosensitiser. Psoralen can be administered orally or topically, either by immersing in a bath, or applying it as soaks, creams, or gels. The main psoralens used for oral PUVA are 8‐methoxypsoralen (8‐MOP) and 5‐methoxypsoralen (5‐MOP). 8‐MOP is most commonly used for bath PUVA, although this is not useful in atopic eczema if the face requires treatment. Usually, the dose and treatment schedule of PUVA is based on the minimum phototoxic dose (MPD) to ensure adequate drug bioavailability, or on people's sensitivity to sunlight, corresponding to the Fitzpatrick sun‐reactive skin phototype (Sachdeva 2009; Sidbury 2014). The treatment schedule of PUVA is usually twice weekly for atopic eczema; the UVA radiation dose is gradually increased during the course of treatment by increments, often in the order of 20% to 40%. The total number of PUVA treatments per course will depend on disease response and tolerance. Cumulative treatment numbers will depend on individual factors.

Another form of photochemotherapy is khellin, combined with UV (natural sunlight or UVA). Khellin is a photosensitiser that can be administered topically or orally.

Excimer lamp and excimer laser

Excimer is a complex of excited gases, which upon decomposition, give off excess energy in the form of UV radiation. The excimer exists both as a lamp and a laser. The lamp is a polychromatic (wavelengths 306 nm to 310 nm), non‐targeted (incoherent) light used to treat a range of body surface areas. On the other hand, the laser is a monochromatic (308 nm), targeted (coherent), intermittent (pulsing) light (Brenninkmeijer 2010; Park 2012).

Safety and adverse events

The various forms of phototherapy available for people with atopic eczema have different risk profiles that must be taken into account by the physician (Goldsmith 2012; Menter 2010; Morison 1998; Stern 1997). Common adverse events for any type of UV‐based phototherapy are erythema, pruritus, and a sense of burning or stinging, although it is important to be aware that erythema from PUVA may not be apparent until 48 hours to 96 hours after exposure. Other less common consequences of phototherapy are induction of polymorphous light eruption, folliculitis, herpes simplex virus reactivation, and photo‐onycholysis (with PUVA). The most common side effect of oral psoralen is nausea. Uncommonly, pain may occur, and seems specific to PUVA rather than other UV‐based phototherapies. It is likely that this is neuropathic in nature, and is important to recognise, as PUVA should be discontinued in that instance. The risk of squamous cell carcinoma is increased if people are exposed to high cumulative numbers of PUVA treatments (more than 150 to 200 (Stern 1998)). While a delayed risk of melanoma was reported, it has not been replicated, nor has a causal role been proven (Stern 1997). A larger Swedish study, including people with atopic eczema, did not show this association (Lindelöf 1991; Lindelöf 1999).

The incidence of adverse events of phototherapy is considered to be low, although the true incidence is unknown. Most publications on the safety and adverse events of phototherapy concern the treatment of people with psoriasis, and it is unclear how the outcomes of these studies relate to outcomes for people with atopic eczema. However, noncompliance rates secondary to side effects are very low in the available studies for atopic eczema (Clayton 2007; Grundmann‐Kollmann 1999; Jekler 1988; Meduri 2007; Tay 1996).

Prescribing practices

A recent survey was conducted by the European TREatment of ATopic eczema (TREAT) Registry Taskforce. Invited via a mailing list of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology and national societies, 238 dermatologists from 30 European countries participated (Vermeulen 2020). The most common first‐line non‐topical therapy for people with moderate to severe atopic eczema was phototherapy, prescribed by 41.5% of survey participants, followed by day‐care therapy (39.3%), and systemic therapy (26.6%). NB‐UVB and PUVA were the most frequently prescribed first‐ and second‐line choices of phototherapy for atopic eczema. Only a small minority of participants prescribed UVA1. The most important reason participants stated for using phototherapy was personal experience with the treatment (58.8%).

There is an absence of published data on phototherapy practice patterns for the treatment of atopic eczema for regions outside Europe. The guidelines of care for the management of atopic eczema by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) state that phototherapy is a second‐line treatment, and that choice of phototherapy modality should be guided by factors, such as availability, cost, skin phototype, skin cancer history, and the use of photosensitising medications (Sidbury 2014). Anecdotally, different types of UVB (NB and BB) may be the most commonly used form of phototherapy for atopic eczema in North America. In general, NB‐UVB is often recommended, taking into account its relative efficacy, low adverse effects profile, and availability (Sidbury 2014). A study on phototherapy utilisation and costs in the USA found that the total invoice of phototherapy services for all diseases increased 5% annually from 2000 to 2015. UVB comprised 77% of phototherapy volume, and 92% of phototherapy was prescribed by dermatologists (Tan 2018).

Previous evidence

A previous systematic review, using GRADE methodology, showed that phototherapy can be a valid therapeutic option for people with atopic eczema (Garritsen 2014). Garritsen and colleagues highlighted that the best evidence on efficacy is available for the use of NB‐UVB and UVA1 (Garritsen 2014). These findings are in line with the recommendations in the Atopic Eczema treatment guideline from the European Dermatology Forum (Wollenberg 2018). The review further showed that there was little information available on the duration of remission, long‐term safety, efficacy in children, and in acute versus chronic atopic eczema. The review authors also identified some shortcomings in the quality of the included studies. They argued that studies should adequately measure the use of concomitant topical corticosteroids, and use validated diagnostic atopic eczema criteria and outcome measurements.

Another systematic review supported the findings of Garritsen 2014 regarding the evidence for the use of NB‐UVB and UVA1 phototherapy in moderate to severe atopic eczema (Pérez‐Ferriols 2015). These review authors found that there was scarce evidence supporting the use of PUVA, and little information on phototherapy for atopic eczema in children. The authors recommended standardisation of radiation methods, and the use of comparable criteria, scales, and minimum length of follow‐up in future studies (Pérez‐Ferriols 2015).

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) on high versus medium UVA1 phototherapy reported that UVA1 phototherapy should be considered among the first approaches in people with severe atopic eczema, and stated that high dose was more effective than medium dose UVA1 for dark skin types (Pacifico 2019).

In an observational multicentre study, researchers observed 207 people with psoriasis, and 144 people with atopic eczema, in eight centres (Väkevä 2019). For the people with atopic eczema, scores from the Patient‐Oriented SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (PO‐SCORAD) index and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) improved significantly during and after treatment (measured at three months or more). Alleviation of pruritus correlated with better quality of life. The study authors indicated that further studies in atopic eczema were necessary to determine the best treatment dose.

How the intervention might work

Several factors are believed to contribute to the effectiveness of phototherapy (Gambichler 2009). First, suppression of the antigen‐presenting function of Langerhans cells is believed to be the mechanism of the immune‐suppressing effect, together with induction of apoptosis of infiltrating T‐cells (Majoie 2009). Second, phototherapy is found to thicken the stratum corneum. This causes the skin to be less susceptible to pathogens and antigens, resulting in smaller eczematous reactions (Jekler 1990). And last, there seems to be suppression of the colonisation of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus and Pityrosporum orbiculare (the yeast form of Malassezia furfur), which is helpful for people with atopic eczema, as their skin often shows superabundance of these organisms. S. aureus secretes toxins that drive atopic eczema (Alexander 2020; Faergemann 1987; Weidinger 2016), while P. orbiculare can trigger the development and persistence of atopic eczema through the generation of autoantigens (Nowicka 2019).

The mechanisms of action of different phototherapeutic options differ, but include anti‐inflammatory, antiproliferative, and immunosuppressive effects, which will be of differing importance in contributing to the effects seen in different diseases. Anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects are of importance in atopic eczema.

UVB exerts its effects mainly at the level of the epidermis and superficial dermis, while UVA‐based phototherapies affect mid‐ and deep‐dermal components, including blood vessels. UVB radiation is absorbed by endogenous chromophores, such as nuclear DNA, initiating a cascade of events. Absorption of UV light by nucleotides leads to the formation of DNA photoproducts and suppresses DNA synthesis. UV light stimulates the synthesis of prostaglandins and cytokines that play important roles in immune suppression. It can reduce the number of Langerhans cells, cutaneous T‐lymphocytes, and mast cells in the dermis. UV radiation can also affect extranuclear molecular targets located in the cytoplasm and cell membrane. The combination of immune suppression, alteration in cytokine expression, and cell cycle arrest contributes to the suppression of disease activity (Bulat 2011).

With PUVA, the conjunction of psoralens with epidermal DNA inhibits DNA replication, and causes cell cycle arrest. Psoralen photosensitisation also causes an alteration in the expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors. Psoralens interact with RNA, proteins, and other cellular components, and indirectly modify proteins and lipids via single oxygen‐mediated reactions, or by generating free radicals. Infiltrating lymphocytes are strongly suppressed by PUVA, with variable effects on different T‐cell subsets (Bulat 2011).

Studies in Asian populations have suggested that both NB‐UVB, and a combination of UVA plus NB‐UVB, are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic eczema (Mok 2014). NB‐UVB, which is usually the preferred modality for treating atopic eczema, requires higher doses in more pigmented skin types (Meduri 2007; Syed 2011a; Syed 2011b).

UVA1 is thought to be faster and more efficacious for treating acute atopic eczema, and is equally effective in skin types I to V, without requiring dose adjustments (Jacobe 2008; Mok 2014). However, it is not clear how atopic eczema disease phenotype (e.g. predominantly flexural versus discoid, or follicular) impacts on the responsiveness to the different types of phototherapy; this area requires further study.

Why it is important to do this review

A good summary of the evidence of the different types of phototherapy will be useful to detect the gaps of evidence and to determine the future research agenda. The knowledge gap and varying prescribing practices have led to limited reimbursement of phototherapy for atopic eczema by healthcare insurance companies in some countries, making a promising treatment modality unattainable for some people for whom topical corticosteroids are insufficient. The costs of atopic eczema per person are expected to rise in the coming years, when dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL‐4 and IL‐13, and baricitinib, a janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor are approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, and most importantly, because of the arrival of other new systemic treatments, such as new JAK inhibitors. Thus, high‐quality research into therapeutic alternatives, which have longstanding track records for efficacy, safety, and cost‐effectiveness, is very important.

Limitations on the reimbursement of phototherapy and other off‐label treatments in the future, may lead to a shift to new on‐label, and much more expensive systemic treatments that have been proven effective in RCTs. The question is whether this is desirable, as not all new treatments are widely available globally. Therefore, our aim is to investigate the effectiveness and safety of phototherapy in the treatment of atopic eczema. With the results, we aim to strengthen existing and evolving guidelines for atopic eczema, and provide meaningful evidence to support treatment decisions. We will also highlight the gaps in evidence in relation to this topic.

Cochrane Skin undertook an extensive prioritisation exercise in 2020 to identify a core portfolio of the most clinically important questions. The topic of phototherapy for eczema was identified as one of the top three titles (Cochrane Skin 2020b). This review is also directly applicable to, and is being conducted to inform the update of the European and American guidelines on the use of phototherapy for atopic eczema.

Objectives

To assess the effects of phototherapy regimens (e.g. narrowband ultraviolet B (NB‐UVB), broadband ultraviolet B (BB‐UVB), psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA), ultraviolet A1 (UVA1)) for people with atopic eczema.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cross‐over trials, and randomised within‐participant trials.

Types of participants

We included studies conducted in participants with atopic eczema of any phenotype and severity. We included participants of all ages with a clinical diagnosis of atopic eczema. The diagnostic criteria could include the Hanifin and Rajka definition (Hanifin 1980), or the UK modification (Williams 1994), or they could have been diagnosed clinically by a healthcare professional, using the terms 'atopic eczema' or 'atopic dermatitis', for example. Studies in children who were described as having ‘eczema’, as opposed to ‘atopic eczema’, were also eligible.

We assessed the distribution of relevant participant characteristics, including severity of atopic eczema, age, and concomitant medications.

We imposed no restrictions on age, sex, or ethnicity of participants.

We excluded studies that included participants with other types of eczema, such as contact dermatitis, seborrhoeic eczema (seborrhoeic dermatitis), varicose eczema, discoid eczema, irritant dermatitis, and hand eczema.

We only included participants with diagnoses, such as 'Besnier's prurigo' or 'neurodermatitis' if there was additional descriptive evidence of atopic eczema in the flexures. We only included studies in which not all participants had atopic eczema if separate results were reported for the participants with atopic eczema.

Types of interventions

Any kind of phototherapy, including the following.

Broadband ultraviolet B (BB‐UVB; 280 nm to 315 nm)

Narrowband UVB (NB‐UVB; 311 nm to 313 nm; i.e. TL‐01)

UVA (315 nm to 400 nm)

UVA1 (340 nm to 400 nm)

Cold‐light UVA1 (containing a cooling system eliminating wavelengths greater than 530 nm)

UVAB (280 nm to 400 nm)

Full‐spectrum light (320 nm to 5000 nm, including UVA, visible, and infrared light)

Saltwater bath plus UVB (balneophototherapy)

Coal tar plus UVB radiation (Goeckerman therapy)

Psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) with oral 8‐methoxypsoralen (8‐MOP)

Psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) with 5‐methoxypsoralen (5‐MOP)

Oral trimethylpsoralen with UVA (PUVA)

Oral khellin plus UV

Topical khellin plus UV

Heliotherapy

Excimer laser

Excimer lamp

For the comparators, we accepted any other type of treatment regimen, namely: any type of phototherapy; systemic treatment (e.g. prednisolone, cyclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine, biologics); topical treatment (e.g. topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, coal tar); placebo; or no treatment. We included studies in which concomitant medications or co‐interventions were given, as long as the medication regimen was the same in each treatment arm. We included treatment given in any setting, for example clinic‐based or home phototherapy.

In studies where two treatment intervention groups from different categories were compared against a single comparator group, the relevant treatment group and the same comparator group were included in two separate pair‐wise meta‐analyses.

Types of outcome measures

We defined treatment outcomes as short‐term (up to and including 16 weeks after initiating treatment, taking the measurement closest to 12 weeks if outcomes were measured at multiple time points), and long‐term (more than 16 weeks after initiating treatment, taking the longest time point if outcomes were measured at multiple time points). Long‐term control was defined as the closest time point to six months after the end of the course of phototherapy, assessed in the same way as the primary outcome for physician‐assessed and participant‐reported changes in signs and symptoms of atopic eczema. Outcomes of interest in this review were in accordance with the core outcomes (including core outcome instruments) of the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) initiative (Schmitt 2014).

We included studies in this review regardless of whether our primary and secondary outcomes were measured.

Primary outcomes

-

Physician‐assessed changes in clinical signs of atopic eczema

Using the following measurement instruments (in hierarchy, starting with the most preferred instrument): EASI (Ricci 2009), Objective SCORAD (or compound SCORAD if objective SCORAD was not reported (Kunz 1997), Costa (Costa 1989), SASSAD (Charman 2002)

-

Patient‐reported changes in symptoms of atopic eczema, including itch

Using the following multi‐item measurement instruments for atopic eczema symptoms (in hierarchy, starting with the most preferred instrument): POEM (Charman 2004), subjective SCORAD; and the following single‐item measurement instruments for itch (in hierarchy, starting with the most preferred instrument): peak numerical rating scale (NRS (Yosipovitch 2019)), average NRS, visual analogue scale (VAS (Reich 2012)), verbal rating scale (VRS(Phan 2012))

Secondary outcomes

Investigator Global Assessment (IGA)

Health‐related quality of life, measured with the (Skindex‐29 (Chren 1996), Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI (Finlay 1994)), Children's DLQI (CDLQI (Lewis‐Jones 1995))

Safety (adverse events and tolerability (i.e. withdrawals due to adverse events))

Long‐term control, at the closest time point to six months after the end of the course of phototherapy, assessed in the same way as the primary outcome (e.g. EASI or POEM)

Search methods for identification of studies

We aimed to identify all relevant RCTs, regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist (Liz Doney) searched the following databases, using strategies based on the draft strategy for MEDLINE in our published protocol (Musters 2021).

The Cochrane Skin Specialised Register (searched 13 January 2021, using the search strategy in Appendix 1);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2021, Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library (searched 13 January 2021, using the strategy in Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (from 1946 to 13 January 2021), using the strategy in Appendix 3;

Embase Ovid (from 1974 to 13 January 2021), using the strategy in Appendix 4.

Trials registers

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist searched the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 19 January 2021, using the search strategy in Appendix 5). The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch/) was not available at this time, due to technical issues.

Searching other resources

Searching reference lists

We checked the bibliographies of included studies and any relevant systematic reviews for further references to relevant trials.

Searching by contacting relevant individuals or organisations

We contacted experts and organisations in the field to request additional information on relevant trials (Table 5).

1. Correspondence with investigators.

| Study ID | Correspondence | Response |

| Agrawal 2018 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to purbi1@yahoo.com to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Byun 2011 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to entdoctor@cau.ac.kr to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Der‐Petrossian 2000 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to manon.der‐petrossian@akh‐wien.ac.at to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Dittmar 2001 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to dittmar@haut.ukl.uni‐freiburg.de to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| NCT02915146 | Email sent 02 March 2021 to r.s.dawe@dundee.ac.uk to confirm study is ongoing. | Reply received 02 March 2021 |

| Gambichler 2009 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to thilo.gambichler@klinikum‐bochum.de to request raw dataset (original data). | Reply received on 26 May 2021: authors are unable to share the raw data of this trial. |

| Granlund 2001 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to hakan.granlund@hus.fi to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Heinlin 2011 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to sigrid.karrer@klinik.uni‐regensburg.de to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Hoey 2006 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to hoeysusannah@hotmail.com to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Keemss 2016 | Email sent 17 Feb 2021 to vvonfelbert@ukaachen.de to clarify inclusion criteria for this study (whether any participants were included with conditions excluded from this systematic review). | No reply received |

| Kromer 2019 | Emails sent 24 Feb 2021 to timo.buhl@meduni‐goettingen.de to clarify if linked to Keemss 2016. | Reply received 24 Feb 2021 |

| Krutmann 1992 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to krutmann@uni‐duesseldorf.de to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Krutmann 1998 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to krutmann@uni‐duesseldorf.de to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Legat 2003 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to peter.wolf@uni‐graz.at to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Leone 1998 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to gleone@ifo.it to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Majoie 2009 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to iml.majoie@meandermc.nl to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Maul 2017 | Email sent 02 March 2021 to alexander.navarini@usz.ch to request information on atopic dermatitis patients separately. | No reply received |

| Maul 2017 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to alexander.navarini@usz.ch to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| NCT01402414 | Emails sent 26 January 2021 to s.terras@klinikum‐bochum.de and t.gambichler@klinikum‐bochum.de to clarify if study is eligible for inclusion. | Reply received on 27 Jan 2021 to confirm recruitment was terminated |

| Pacifico 2019 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to alessia.pacifico@gmail.com to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Qayyum 2016 | Email sent 19 April 2021 to drsadiaqayyum@hotmail.com to clarify the type of UVB lamps used in the study. | No reply received |

| Qayyum 2016 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to drsadiaqayyum@hotmail.com to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Reynolds 2001 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to nick.reynolds@ncl.ac.uk to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Tzaneva 2001 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to anislava.tzaneva@meduniwien.ac.at to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Tzaneva 2010 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to anislava.tzaneva@meduniwien.ac.at to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Tzung 2006 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to tytzung@isca.vghks.gov.tw to request raw dataset (original data). | No reply received |

| Youssef 2020 | Email sent 02 March 2021 to randayoussef@kasralainy.edu.eg and ahmedhm@gmail.com to request further information. | No reply received |

| Youssef 2020 | Email sent 26 May 2021 to vanessahafez@kasralainy.edu.eg to request raw dataset (original data). | Reply received on 27 May 2021: authors are happy to share the raw data of this trial; however, we did not receive it after our reply on 27 May 2021 |

Unpublished literature

We sought information about unpublished or incomplete trials by corresponding with investigators or organisations, or both, known to be involved in previous relevant studies (Table 5).

Correspondence with trialists, experts, and organisations

We contacted original authors for clarification and further data if trial reports were unclear (Table 5).

Adverse effects

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of phototherapy interventions used for the treatment of eczema. We only considered adverse effects described in included studies.

Errata and retractions

The Cochrane Skin Information Specialist ran a specific search to identify errata or retractions related to our included studies on 13 July 2021. No relevant retraction statements or errata were retrieved.

Data collection and analysis

We used the software, Covidence, to manage the study selection and Microsoft Excel for the data extraction process (Covidence).

Selection of studies

Two pairs of review authors (SM and AM, and SL and JH) independently screened all identified titles and abstracts using Covidence. We examined the full texts of studies that potentially met the criteria, as well as studies for which abstracts did not provide sufficient information. We resolved disagreements through discussion with a senior review author (PS).

Data extraction and management

Two pairs of review authors (SM and AM, and SL and JH) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. One review author (JH) entered the characteristics of each study into Review Manager Web, and another reviewer (JH) checked these data for accuracy (RevMan Web 2020). For studies that met the inclusion criteria, we extracted relevant information into evidence tables, using an a priori defined proforma, piloting data extraction on a subset of studies before final extraction. We resolved disagreements through discussion with a senior review author (PS).

We extracted data on methodological quality, participants, interventions, and outcomes of interest, according to the Harmonising Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) consensus, from the included studies, using the following data extraction fields.

Author and year of publication

Year and country

Sample size

Study design

Age

Setting (hospital or population‐based)

Type of phototherapy

Length and frequency of treatment

Cumulative doses of UV radiation

Duration of follow‐up

-

Primary outcomes:

Physician‐assessed changes in the clinical signs of atopic eczema

Patient‐reported changes in symptoms of atopic eczema, including itch

-

Secondary outcomes:

Investigator Global Assessment (IGA)

Health‐related quality of life

Safety (adverse events and tolerability (i.e. withdrawals due to adverse events))

Long‐term control, at the closest time point to six months after the end of the course of phototherapy, assessed in the same way as the primary outcome

Translation (yes/no)

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (EA and RB) independently assessed the risk of bias for the effect of assignment to the intervention, using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool (Higgins 2020b; Sterne 2019). We only assessed the outcomes in the summary of findings tables (see Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence section). We resolved disagreements through discussion. The RoB 2 tool addresses the following domains.

Bias arising from the randomisation process

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions

Bias due to missing outcome data

Bias in measurement of the outcome

Bias in selection of the reported result

We answered a number of signalling questions, which led to the tool algorithm assessing each domain as high risk, low risk, or some concerns. The tool algorithm also calculates an overall risk of bias, as high risk, low risk, or some concerns. To undertake these assessments, we used the RoB 2 Excel Tool. The answers to these signalling questions are available on an online repository.

We did not use the cross‐over variant of the RoB 2 tool, because we only included data from the first phase of cross‐over trials.

Measures of treatment effect

We presented continuous outcomes, where possible, on the original scale reported in each individual study, with a mean change from baseline and its associated standard deviation (SD). We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) as a measure of effect for continuous outcomes that used different scales (e.g. EASI and SCORAD). We calculated risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes, and presented either the number needed to treat for one additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), or the number needed to treat for one additional harmful outcome (NNTH), when the results, including their measure of variance, fell on the same side of the line of no effect. We calculated odds ratios (OR) for within‐participant studies, and in meta‐analyses in which we combined parallel and within‐participant studies.

If outcome data were reported as 'physician‐assessments of the time needed until skin improvement', we presented these narratively, highlighting the general trend within the groups at the first time point at which an improvement was seen.

We reported all outcome data with their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs), where possible.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over studies

Unit of analysis issues can arise in studies where participants have been randomised to multiple treatments in multiple periods, or when there has been an inadequate wash‐out period. For cross‐over trials, we used data from the first treatment period, due to concerns with carry‐over effects, unless otherwise stated.

Within‐participant studies

For paired data from studies with no suspicion of contamination across intervention sites, we planned to analyse using the generic inverse‐variance method in Review Manager Web, after accounting for the within‐participant variability (Higgins 2020a). In studies that reported paired data, but did not adjust for the within‐participant variability, we planned to use a McNemar's test with the corresponding P value. However, no such data were available. When paired data were not reported, we performed variance corrections for the within‐participant studies using the Becker‐Balagtas method (Elbourne 2002). We assumed an intra‐class correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.5 in our calculations.

For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated OR for both study designs (number of participants with the event receiving the intervention, multiplied by the number of participants without the event in the control group, divided by the number of participants with the event receiving the control, multiplied by the number of participants without the event in the intervention group (Higgins 2020a)). A continuity correction of 0.5 was used in the case of zero events (Sweeting 2004). We pooled data from within‐participant studies with data from parallel‐group studies in meta‐analyses using the generic inverse‐variance method, inputting the natural log of the OR.

More than two treatment comparisons

We included multi‐arm trials in the review if at least one arm examined a type of phototherapy for atopic eczema, and completed a separate data extraction for each pair‐wise comparison. We included these studies as pair‐wise comparisons. For future updates, to prevent double‐counts of participants if treatment arms from multi‐arm studies are pooled in more than one meta‐analysis, we will partition them according to the number of comparisons carried out, and analyse them following the recommendations in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2020a).

Dealing with missing data

If data were missing from trials that were carried out less than 10 years ago, we attempted to contact the investigators or sponsors of these studies. We re‐analysed data according to the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle whenever possible. For dichotomous outcomes, if study authors had conducted a per‐protocol analysis, and we had concerns about the level of missing data, we attempted to carry out an ITT analysis with imputation, using baseline values for the missing data, after checking the degree of imbalance in the dropouts between the arms, to determine the potential impact of bias (Higgins 2020a). We planned to carry out a per‐protocol analysis instead of an ITT analysis for continuous outcomes.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining the study characteristics, the similarity between the types of participants, interventions, comparisons, and outcomes, as specified in the criteria for included studies. Although a degree of heterogeneity between the studies included in a review is inevitable, we entered them into a meta‐analysis if we could explain the heterogeneity by clinical reasoning, and make a coherent argument for combining the studies. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic. We interpreted the I2 as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

70% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

We acknowledge that I2 depends on magnitude and direction of effects, and the strength of the evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. the P values from the Chi2 test). We explored heterogeneity through subgroup and sensitivity analysis. If we could not explain it through these methods, we downgraded the evidence for inconsistency in the GRADE assessments.

Assessment of reporting biases