ABSTRACT

Recent omics studies have provided invaluable insights into the metabolic potential, adaptation, and evolution of novel archaeal lineages from a variety of extreme environments. We utilized a genome-resolved metagenomic approach to recover eight medium- to high-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) that likely represent a new order (“Candidatus Sysuiplasmatales”) in the class Thermoplasmata from mine tailings and acid mine drainage (AMD) sediments sampled from two copper mines in South China. 16S rRNA gene-based analyses revealed a narrow habitat range for these uncultured archaea limited to AMD and hot spring-related environments. Metabolic reconstruction indicated a facultatively anaerobic heterotrophic lifestyle. This may allow the archaea to adapt to oxygen fluctuations and is thus in marked contrast to the majority of lineages in the domain Archaea, which typically show obligately anaerobic metabolisms. Notably, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could conserve energy through degradation of fatty acids, amino acid metabolism, and oxidation of reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs), suggesting that they may contribute to acid generation in the extreme mine environments. Unlike the closely related orders Methanomassiliicoccales and “Candidatus Gimiplasmatales,” “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” lacks the capacity to perform methanogenesis and carbon fixation. Ancestral state reconstruction indicated that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales,” the closely related orders Methanomassiliicoccales and “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” and the orders SG8-5 and RBG-16-68-12 originated from a facultatively anaerobic ancestor capable of carbon fixation via the bacterial-type H4F Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP). Their metabolic divergence might be attributed to different evolutionary paths.

IMPORTANCE A wide array of archaea populate Earth’s extreme environments; therefore, they may play important roles in mediating biogeochemical processes such as iron and sulfur cycling. However, our knowledge of archaeal biology and evolution is still limited, since the majority of the archaeal diversity is uncultured. For instance, most order-level lineages except Thermoplasmatales, Aciduliprofundales, and Methanomassiliicoccales within Thermoplasmata do not have cultured representatives. Here, we report the discovery and genomic characterization of a novel order, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales,” within Thermoplasmata in extremely acidic mine environments. “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” are inferred to be facultatively anaerobic heterotrophs and likely contribute to acid generation through the oxidation of RISCs. The physiological divergence between “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and closely related Thermoplasmata lineages may be attributed to different evolutionary paths. These results expand our knowledge of archaea in the extreme mine ecosystem.

KEYWORDS: acid mine drainage, ancestral state reconstruction, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales, ” facultatively anaerobic heterotrophic lifestyle, genome-resolved metagenomics

INTRODUCTION

Archaea, representing a distinct domain of life, have been shown to inhabit diverse habitats, including extreme (such as hot springs, hypersaline environments, acid mine drainage [AMD], etc.) and nonextreme environments (such as seawater, soils, and sediments) (1–6), where they may play crucial roles in biogeochemical cycles (7, 8). However, the majority of the archaeal diversity remains uncultured, limiting our understanding of their metabolic capacities and evolutionary history (7–9). New cultivation-independent genomic approaches, especially metagenomics and single-cell genomics, have enabled reconstruction of nearly complete or even closed genomes for uncultured archaea directly from the environment (10). This has led to the discovery of many candidate archaeal phyla and dramatically expanded the archaeal tree of life (7, 8). Subsequent analyses of the metabolic capabilities, origin, and evolutionary history of these uncultured microorganisms on the basis of the retrieved genomes have significantly advanced our understanding of archaeal biology (8).

Thermoplasmata is a globally distributed and ecologically significant class-level archaeal lineage (11). Due to its wide range of lifestyles and specific genomic and cellular features, this unique archaeal group could serve as an excellent model for the study of environmental adaptation and evolutionary processes within the Archaea (12). For instance, all members of the order Thermoplasmatales have extremely acidic pH optima for growth (among the lowest known, with Picrophilus spp. showing the lowest pH value of 0.7), and their cells (except for Picrophilus spp.) are typically pleomorphic as a consequence of the lack of an intact cell wall (13). Thus, characterization of these cell wall-deficient archaea may provide important insights into the acid tolerance mechanisms of microbial life (14). Meanwhile, while the Archaea have been implicated to have evolved and diversified primarily in anoxic habitats, aerobic metabolism has been found in a few archaeal lineages, including some members of the Sulfolobales and Thermoplasmatales (15), which may have coevolved with the acidity of their habitats after the appearance of oxygenic photosynthesis (16). The details of the evolutionary transition from an anaerobic metabolism to the aerobic lifestyle and the process of geological-biological feedbacks associated with aerobic archaeal lineages remain largely unresolved, however. The coexistence of both anaerobic and aerobic members within the Thermoplasmata renders it an interesting target for investigating this issue. However, the number of Thermoplasmata orders characterized thus far is limited, hampering our understanding of the metabolic potential, ecology, and evolutionary history of this important archaeal class.

The extreme AMD environment represents an important model system for the study of microbial community structure, function, and evolution (17, 18). Early environmental surveys based on 16S rRNA sequencing and more recent metagenomics explorations have revealed the existence of novel archaeal lineages (2, 19), including the “alphabet plasmas” in the Thermoplasmatales (20), in AMD ecosystems. Here, we report discovery and genomic characterization of a novel order (“Candidatus Sysuiplasmatales”) in the class Thermoplasmata based on eight metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) retrieved from acidic mine tailings and AMD sediments collected from two mine sites in South China. Reconstruction of metabolic pathways resolved the physiology and revealed potential ecological roles of these uncultured archaea, and ancestral state reconstruction revealed evolutionary paths leading to extant divergent Thermoplasmata lineages, including “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales.”

RESULTS

Metagenomic discovery, phylogeny, and environmental distribution of the novel Thermoplasmata order “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales.”

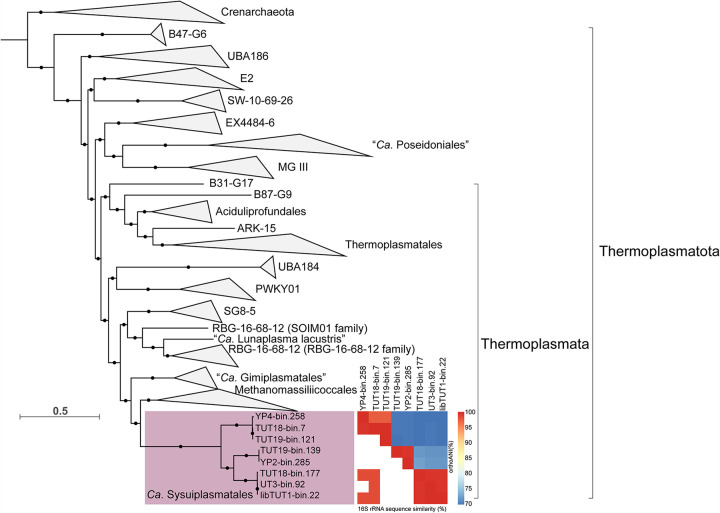

A total of 303 Gbp of quality-controlled metagenomic data was generated from four extremely acidic mine tailings samples and two AMD sediments collected from two copper mines in South China (see Data Set S2 in the supplemental material). Metagenomic assembly and binning recovered eight unique Thermoplasmata genomes (metagenome-assembled genomes [MAGs]). Genome sizes ranged from 1.96 to 2.29 Mbp, with estimated completeness ranging between 86% and 99% and an estimated contamination of 0.8%, suggesting that these MAGs are well curated and high quality (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis based on 122 concatenated archaeal marker genes and 16 concatenated ribosomal proteins revealed that these archaeal MAGs likely represent one distinct lineage in the class Thermoplasmata and grouped phylogenetically closely to Methanomassiliicoccales, “Candidatus Gimiplasmatales,” and the SG8-5 and the RBG-16-68-12 orders (Fig. 1; Fig. S2). Pairwise 16S rRNA gene identity values between the members of the order “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and other members that affiliated with the closely related orders Methanomassiliicoccales, “Candidatus Gimiplasmatales,” SG8-5, and RBG-16-68-12 were lower than 89% (Data Set S3), which indicated that they belong to one novel Thermoplasmata order (21). Furthermore, genome identity values (average amino acid identity and orthologous average nucleotide identity [OrthoANI]) of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” compared with its four closely related orders were as low as values observed among the four closely related orders (Fig. S3). Therefore, we propose one novel order within the class Thermoplasmata. Comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences of the novel order with the NCBI GenBank database retrieved only four 16S rRNA gene sequences from AMD and hot spring-related environments (Fig. S1; Data Set S4) (22–24).

TABLE 1.

Genomic information of the Thermoplasmata novel-order MAGs retrieved from metagenomes

| Parameter | “Ca. Sysuiplasma acidiphilum” |

“Ca. Sysuiplasma semianaerobium” |

“Ca. Sysuiplasma thiosulfatiphilum” |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUT18-bin.7 | TUT19-bin.121 | YP4-bin.258 | TUT19-bin.139 | YP2-bin.285 | UT3-bin.92 | TUT18-bin.177 | libTUT1-bin.22 | |

| Genome size (bp) | 1,972,931 | 1,960,374 | 1,981,594 | 1,991,662 | 2,063,816 | 2,292,200 | 2,181,979 | 2,032,561 |

| No. of scaffolds | 35 | 66 | 73 | 184 | 100 | 55 | 133 | 51 |

| N50 (bp) | 84,739 | 49,042 | 47,186 | 16,058 | 69,006 | 96,805 | 35,432 | 90,623 |

| GC content (%) | 50.93 | 50.95 | 51.05 | 50.13 | 50.09 | 49.59 | 49.8 | 49.84 |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.01 | 99.01 | 97.25 | 86.21 | 95.01 | 99.14 | 99.01 | 93.54 |

| Contamination (%)a | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| No. of predicted genes | 2,000 | 2,012 | 2,037 | 2,083 | 2,082 | 2,349 | 2,267 | 2,017 |

| No. (%) of genes annotated byb: | ||||||||

| KEGG | 974 (48.7) | 967 (48.1) | 979 (48.1) | 968 (46.5) | 1,031 (49.5) | 995 (42.4) | 1,009 (44.5) | 957 (47.4) |

| COG | 1,536 (76.8) | 1,531 (76.1) | 1,575 (77.3) | 1,559 (74.8) | 1,604 (77.0) | 1,608 (68.5) | 1,630 (71.9) | 1,535 (76.1) |

| Pfam | 1,383 (69.15) | 1,375 (68.4) | 1,395 (68.5) | 1,331 (63.9) | 1,434 (68.9) | 1,480 (63.0) | 1,473 (65.0) | 1,400 (69.4) |

| No. of 16S rRNAs | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| No. of tRNAs | 118 | 75 | 128 | 60 | 112 | 126 | 80 | 103 |

| No. of CRISPR locic | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| No. of spacersc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 31 |

| Relative abundance (%) | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.07 | 0.15 |

The completeness and contamination of these new order genomes were estimated by CheckM.

Functional annotation was against different databases via DIAMOND (E value ≤ 10−5).

CRISPR loci of these genomes were annotated using CRT.

FIG 1.

Phylogenomic tree of the novel order based on 122 archaeon-specific conserved marker genes, OrthoANI values, and 16S rRNA gene similarity values. White spaces indicate cases where no 16S rRNA gene was identified or the 16S rRNA gene was too short to be used for 16S rRNA sequence similarity calculation. The tree was constructed based on the concatenated alignment using IQ-TREE with 1,000 ultrafast bootstrapping iterations. The concatenated alignment was generated by GTDB-Tk. Support values greater than 75% are shown with black solid circles. Crenarchaeota was selected as the outgroup.

Description of the taxa.

The eight MAGs recovered represent three species within a single genus from a novel order affiliated with Thermoplasmata. Taking into account the consensus statement regarding nomenclature of uncultivated prokaryotes (25), we propose the following taxonomic names for these eight MAGs.

“Candidatus Sysuiplasmatales” ord. nov. (Sy.su.i.plas.ma.ta′les. N.L. neut. n. Sysuiplasma, a Candidatus prokaryote name; -ales ending to denote an order; N.L. fem. pl. n. Sysuiplasmatales, the “Candidatus Sysuiplasma” order).

“Candidatus Sysuiplasmataceae” fam. nov. (Sy.su.i.plas.ma.ta.ce′ae. N.L. neut. n. Sysuiplasma, a Candidatus prokaryote name; -aceae ending to denote a family; N.L. fem. pl. n. Sysuiplasmataceae, the “Candidatus Sysuiplasma” family).

“Candidatus Sysuiplasma” gen. nov. (Sy.su.i.plas′ma. Gr. neut. n. plasma, anything formed or molded; N.L. neut. n. Sysuiplasma, a form named after SYSU, acronym of Sun Yat-sen University).

“Candidatus Sysuiplasma acidicola” sp. nov. (a.ci.di′co.la. L. masc. n. acidus, sour; L. masc./fem. suff. -cola [from L. masc./fem. n. incola], dweller, inhabitant; N.L. n. acidicola, an inhabitant of an acidic environment). “Ca. Sysuiplasma acidicola” includes YP4-bin.258, TUT18-bin.7, and TUT19-bin.121, and the type material is TUT18-bin.7.

“Candidatus Sysuiplasma superficiale” sp. nov. (su.per.fi.ci.a′le. L. neut. adj. superficiale, belonging to the surface). “Ca. Sysuiplasma superficiale” includes TUT19-bin.139 and YP2-bin.285, and the type material is YP2-bin.285.

“Candidatus Sysuiplasma jiujiangense” sp. nov. (jiu.jiang.en′se. N.L. neut. adj. jiujiangense, pertaining to Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province, China). “Ca. Sysuiplasma jiujiangense” includes TUT18-bin.177, UT3-bin.92, and libTUT1-bin.22, and the type material is UT3-bin.92.

Metabolic potential.

In order to reveal the metabolic potentials of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” (Fig. 2), we used multiple functional database comparisons for annotation (Data Set S5). Comparative analysis was then performed to determine metabolic differences between “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the closely related Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” and the SG8-5 and the RBG-16-68-12 orders (Fig. 3; Data Sets S6 and S8).

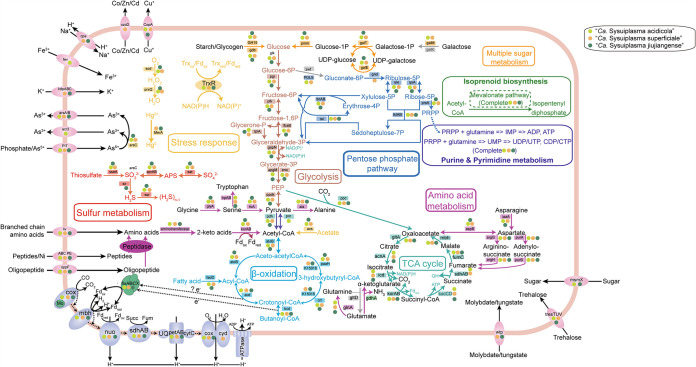

FIG 2.

Metabolic potentials of the novel order. Genes identified in “Ca. Sysuiplasma acidicola,” “Ca. Sysuiplasma superficiale,” and “Ca. Sysuiplasma jiujiangense” are represented by light green, orange, and dark green circles, respectively. The copy numbers of each gene in each genome are listed in Data Set S5.

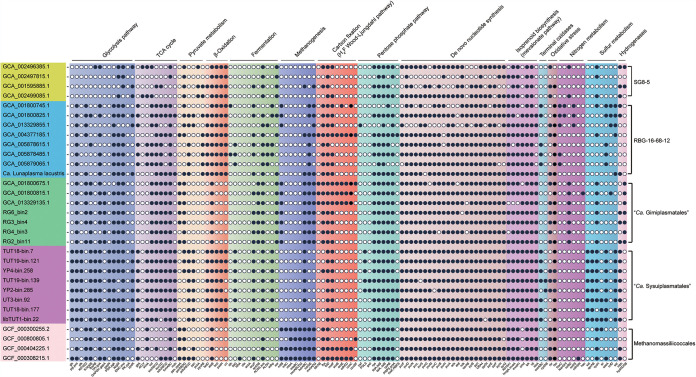

FIG 3.

Occurrence of key proteins of interest in the MAGs of the novel order, Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” RBG-16-68-12, and SG8-5. The MAGs were grouped according to their phylogenetic relationships, and the gene names were grouped by functional categories. The copy numbers of each gene in each genome are provided in Data Set S6. The genes composed of multiple subunits are marked as present if half or more than half of the subunits were identified.

Carbon metabolism.

For all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales,” genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) were found (Fig. 2; Data Set S5). Among these CAZymes, genes encoding starch degradation and glycogen debranching enzymes were prevalent (Data Set S5). The generated glucose could be further oxidized via Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, suggesting that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could conserve energy by glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Moreover, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” coded for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (ppc), suggesting that phosphoenolpyruvate might be a central intermediate connecting glycolysis with the TCA cycle. Furthermore, “Ca. Sysuiplasma acidicola” had the genetic potential for conversion of pyruvate to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) through pyruvate dehydrogenase (pdh) and pyruvate ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase (por) under oxic and anoxic conditions, respectively. Notably, all “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” MAGs could perform acetate assimilation through AMP-forming acetyl-CoA synthetase (acs), and the generated acetyl-CoA could be used for the biosynthesis of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids and energy metabolism (11, 26). This further suggests a heterotrophic lifestyle for “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” through acetate assimilation, which is similar to the closely related members of the Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” and the SG8-5 and RBG-16-68-12 orders (11) (Fig. 3; Data Set S6).

Surprisingly, unlike closely related members of the Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales” and the order RBG-16-68-12, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” members do not harbor the bacterial-type carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase (CODH/ACS) complexes, which are key enzymes for anaerobic carbon fixation via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway (WLP) (27), suggesting that these new archaea may not have the capability for carbon fixation via WLP. Furthermore, the eight MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” coded for l-lactate dehydrogenase complex protein LldG but lacked LldE and LldF, suggesting a deficiency in lactate fermentation (28). In addition, fatty acid β-oxidization potential was present in all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales”; thus, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” was inferred to conserve energy via degradation of fatty acids.

Sulfur metabolism.

Thiosulfate (S2O32−) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which are generated during leaching of metal sulfides (29), represent two kinds of reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) in acidic mining environments. Metabolic reconstruction suggested that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could conserve energy through oxidation of RISCs (Fig. 2). For example, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could utilize adenylylsulfate reductase (arpAB) and sulfate adenylyltransferase (sat) to produce sulfate through oxidation of sulfite, which might be generated through transformation of thiosulfate via thiosulfate/3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (sseA) (30). Furthermore, “Candidatus Sysuiplasma jiujiangense” coded for sulfite reductase (ferredoxin), which could reduce sulfite to hydrogen sulfide. The hydrogen sulfide generated might be oxidized to polysulfide via sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (sqr), which functions under anaerobic conditions in most cases (31).

Oxidative phosphorylation.

Complete pathways for oxidative phosphorylation (including NADH-quinone oxidoreductase, succinate dehydrogenase, the cytochrome bc1 complex, aa3-type/bd-type cytochrome c oxidase, and V/A-type ATPase) were identified in “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” (Fig. 2; Data Set S5). All MAGs harbored the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase, which is a low-affinity O2 terminal oxidase working under oxic conditions, whereas only “Ca. Sysuiplasma superficiale” harbored bd-type cytochrome c oxidase, which is a high-affinity O2 terminal oxidase that could work under oxygen-limiting conditions (32). This suggested that “Ca. Sysuiplasma superficiale” could be more versatile and thrive in microaerobic and aerobic environments, and “Ca. Sysuiplasma acidicola” and “Ca. Sysuiplasma jiujiangense” could thrive in aerobic environments. Additionally, all MAGs of this novel order harbored genes encoding the aerobic molybdenum-dependent CO dehydrogenase (coxLMS) for CO oxidization (33), further suggesting the proposed aerobic or microaerobic lifestyle for “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales.” In combination with the above-mentioned sqr, por, and pdh genes and the below-mentioned trx, sod, and prxQ genes, these results collectively suggested a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle for “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales.” Furthermore, among Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” and the SG8-5 and RBG-16-68-12 orders, some members affiliated with the RBG-16-68-12 order harbored the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase (Fig. 3), suggesting the capacity for aerobic respiration, which was consistent with previous findings (34).

Cell membrane biosynthesis.

Isoprenoids are necessary for all living organisms and involved in several vital functions, such as compartmentalization and protection (35). As found in other archaea, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” possessed a complete mevalonate (MVA) pathway for biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), which are precursors for isoprenoid biosynthesis (35, 36), thus indicating that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could synthesize isoprenoids de novo. Additionally, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” harbored mevalonate 5-kinase and mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylase of the classical archaeal MVA pathway and did not harbor mevalonate 3-phosphate 5-kinase and mevalonate 3,5-bisphosphate decarboxylase of the novel MVA pathway (37), which has been found to be employed by some extreme acidophiles (such as members of Thermoplasmatales) to efficiently produce isoprenoids (37). Sequence alignment of mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylase of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” against classical MVA pathway decarboxylases showed retention of the invariant Asp-Lys-Arg catalytic triad required for decarboxylation (Fig. S4) and retention of one of the two ATP binding residues in the mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylases of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales,” suggesting a dual function (decarboxylase and kinase) of mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylases of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales.” As mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylase loses the kinase function at low pH, we propose that mevalonate 5-phosphate decarboxylases of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” may produce isoprenoids in the near-neutral cytoplasmic environments which could be maintained by the acid tolerance mechanisms, including the potassium-transporting ATPase system (kdpABC) and proton buffer molecules (Data Set S5).

Amino acid biosynthesis and metabolism.

“Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” harbored biosynthetic pathways for some amino acids, such as alanine and aspartate (Fig. 2; Data Set S5). These organisms could also obtain amino acids via oligopeptide and amino acid transporters and diverse peptidases. Then, amino acids might be oxidized to acetyl-CoA via aminotransferases and 2-oxoglutarate/2-oxoacid ferredoxin oxidoreductase (kor) (34) (Fig. 2), and the reduced ferredoxin could be regenerated concomitantly. It was reported that marine benthic group D (MBG-D) single amplified genomes (SAGs) could utilize amino acid metabolism to conserve energy (38). Thus, we proposed that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could also conduct energy conservation through amino acid metabolism, similar to the predicted metabolism for “Ca. Lunaplasma lacustris,” which belongs to the closely related order RBG-16-68-12 (34).

Nucleotide biosynthesis.

Although “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” did not harbor complete pentose phosphate pathways, all MAGs possessed the complete metabolisms for the nonoxidative pentose phosphate pathway (Fig. 2), which could be used to generate phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) (2, 11). PRPP is a common precursor of de novo nucleotide biosynthesis (11). In combination with the presence of complete de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” (Fig. 2; Data Set S5), these results showed that “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” had the genetic potential for nucleotide de novo biosynthesis (11, 39), which might help these organisms adapt to the acidic habitat, given that free nucleotides might be easily degradable in acidic environments (2).

Electron transfer.

An electron-transferring flavoprotein complex (fixABCX) and butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (bcd) were present in all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales”; thus, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” might utilize FixABCX to transfer electrons released from acyl-CoA to ferredoxin, given that this cytoplasmic electron-bifurcating complex was reported to couple the regeneration of reduced ferredoxin and oxidization of butyryl-CoA to crotonyl-CoA in Clostridium kluyveri (40). Moreover, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” harbored the membrane-bound respiratory complex NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (Nuo) and hydrogenase (mbh), which could reoxidize reduced ferredoxin to create a transmembrane proton motive force. Then ATP could be generated via the V/A-type ATPase. The absence of the NuoEFG subunits encoding the NADH-binding module further confirmed the potential use of reduced ferredoxin as an electron donor (41, 42). Furthermore, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” coded for heterodisulfide reductases (hdrABC2) (Fig. 3), which are ancient enzymes belonging to the prokaryotic common ancestor (43). This ancient enzyme complex might be involved in the oxidation of inorganic sulfur compounds, the reduction of ferric iron and sulfate, and electron transfer (44, 45), not just methanogenic and methanotrophic pathways (46, 47).

Environmental adaptation.

As “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” members inhabit acidic mine environments, they must deal with extreme environmental stresses, including acid stress, heavy metal toxicity, and oxidative stress (Fig. 2; Data Set S5). For acid stress, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” encoded the complete potassium-transporting ATPase system (kdpABC), which could help these organisms prevent inward deflection of protons partially by generating an inside-positive membrane potential (48). Meanwhile, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could produce proton buffer molecules such as arginine and use Na+/H+ antiporters to excrete excess H+ to maintain the cytoplasmic pH near neutral (48–50). For heavy metals toxicity, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” harbored a P-type Cu+ transporter (CopA), and YP2-bin.285 encoded the cobalt-zinc-cadmium efflux system protein, suggesting that efflux of metal ions may be an important strategy to deal with heavy metal stresses. Another strategy employed may be to reduce metal or metalloid ions to reduce toxicity and then export them. Taking arsenic resistance as an example, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could reduce As5+ to As3+ and export it by means of the arsABC operon (11, 48). Additionally, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could reduce Hg2+ to less toxic Hg0 via mercuric reductase (merA) and then export it (48). For oxidative stress, all MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” encoded thioredoxin reductase (trxR), peroxiredoxins (prxQ), and superoxide dismutase (sod), which are employed widely by AMD microorganisms to deal with oxidative stress (51). Notably, three MAGs of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” harbored rubrerythrin (rbr) and rubredoxin (rbo), which make up the oxidative stress protection system used to deal with oxidative stress in anaerobes (52, 53), suggesting that these organisms are facultative anaerobes and exposed to severe oxidative stress. These strategies have been used by other acidophiles to prevent these environmental stresses (48).

Evolutionary history of Thermoplasmata.

To infer evolutionary histories of Thermoplasmata, the Dollo parsimony method in COUNT was implemented to identify the gene gain and loss events by mapping the gene orthologous groups to the phylogenomic tree of 122 concatenated archaeal marker genes. As the focus of this study was to resolve the ecological roles of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the closely related orders Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” SG8-5, and RBG-16-68-12 and reveal the evolutionary paths leading to their different ecological strategies, we focused on tracking the evolutionary history of metabolic pathways among these five orders. The common ancestor of these five orders was inferred to encode 3,052 orthologous genes (Fig. 4; Data Set S7), including several terminal oxidases (the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase and the bd-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit I), pyruvate dehydrogenase (pdh) and pyruvate ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase (por), sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (sqr), rubrerythrin (rbr), and rubredoxin (rbo), suggesting a facultatively anaerobic lifestyle for this ancestral organism (Data Set S7). Moreover, the key bacterial-type H4F WLP genes encoding the CODH/ACS complexes were gained at the branch leading to this common ancestor, indicating that this ancestral organism may be capable of carbon fixation via WLP (11, 54).

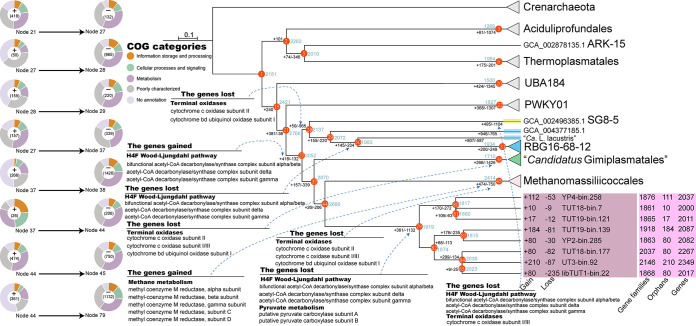

FIG 4.

Ancestral genome content reconstruction of Thermoplasmata, including the novel order. The numbers of gene gain and loss events are marked on the nodes and tips of the phylogenomic tree. The COG category information of the gained and lost genes for the key nodes is shown using pie charts. Some key gene gain and lost events are also marked. The complete topology of the phylogenomic tree and ancestral state reconstruction results are shown in Fig. S5. A list of gained and lost genes for the nodes and tips is presented in Data Set S7.

From this common ancestor, a large number of loss events and a flux of gene family content of considerably smaller magnitude occurred at the branches leading to node 28 and node 37, respectively (Fig. 4). For node 28, some important genes were lost, including those encoding the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit II and the bd-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, potentially shaping the distribution of aerobic metabolism in the SG8-5 and the RBG-16-68-12 orders. Moreover, the genes encoding the key CODH/ACS complexes for the bacterial-type H4F WLP were lost at the branch leading to node 30, which is the last common ancestor (LACA) of the RBG-16-68-12 organisms except for GCA_004377185.1 (Fig. 4), and the bacterial-type H4F WLP has been discovered in GCA_004377185.1 and some members of Methanomassiliicoccales and “Ca. Gimiplasmatales” (11). The rooted phylogenetic tree of CODH/ACS complexes showed that the sequences of Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales” and the RBG-16-68-12 order formed a robust monophyletic clade within the bacterial lineages, suggesting that these genes may have been horizontally transferred from bacteria (Fig. S6). Additionally, the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit II was gained along the branch leading to node 33 (Fig. S5). From node 37, likewise, a large number of loss events and rare gene gain and loss events occurred at the two branches leading to node 38 and node 44, respectively. For node 38, some important genes, such as those encoding the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase and the bd-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, were lost, suggesting an anaerobic lifestyle for “Ca. Gimiplasmatales.”

In combination with retention of the CODH/ACS complexes in node 38 (Data Set S7), these results suggested the capacity of carbon fixation via WLP for “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” which was reported by Hu et al. (11) and Zinke et al. (34). Afterward, two large events of gene flux occurred along the two branches leading to node 45 and node 79, and the extent of gene gain was considerably smaller than that of gene loss, which might shape genome contents of extant organisms of these two orders. Taking the last common ancestor of Methanomassiliicoccales (node 45) as an example, some genes encoding the key methyl-coenzyme M reductase complex associated with methane metabolism were gained; meanwhile, some important genes, such as those encoding the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase and the bd-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit I, were lost (Data Set S7). For node 79, some important genes, such as those encoding the CODH/ACS complexes and pyruvate carboxylase, were lost, while some other important genes, such as those encoding aerobic terminal oxidases (the aa3-type cytochrome c oxidase and the bd-type cytochrome c oxidase subunit I), were retained (Data Set S7), which might contribute greatly to metabolic differentiation between “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and other orders. The finding was consistent with the capacity of aerobic respiration and absence of capacity of carbon fixation via WLP for “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” (Fig. 3). Furthermore, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could not connect glycolysis to the TCA cycle by catalyzing carboxylation of pyruvate to oxalacetic acid by pyruvate carboxylase, which might be easily explained by the above-mentioned gene loss events. Finally, according to the evolutionary path for the genome content of Thermoplasmata, genome contents of most orders might have been shaped by genome streamlining.

DISCUSSION

We propose the novel order “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” within the class Thermoplasmata based on robust phylogenomic analyses and comparative analysis of the values of their genome identity with the orders Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” SG8-5, and RBG-16-68-12. Unlike Thermoplasmatales, another order in Thermoplasmata whose members have been frequently detected in acid mine environments and exhibit a global distribution (55), “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” is distributed in only a limited number of AMD and hot spring-related environments (Fig. S1; Data Set S4). All the recovered 16S rRNA sequences of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” from NCBI GenBank belong to the genus identified in the current study. Although more “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” clades might remain to be discovered, efforts may be hampered by their low abundance in nature. It is well accepted that PCR-based 16S rRNA gene surveys often overlook rare taxa in natural microbial communities. Our discovery of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” indicates that, while decades of molecular surveys have significantly expanded our knowledge of microbial diversity in AMD environments, novel microbial lineages still remain undiscovered. Technical advances such as environmental genomics hold promise for the exploration of this microbial dark matter.

Prediction of metabolic capabilities revealed possible ecological roles of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the remarkable differences in the lifestyle and metabolic potentials between “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the closely related clades within Thermoplasmata. The genetic determinants suggest a facultative anaerobic heterotrophic lifestyle capable of sustaining organisms in the acidic environment. This is important because shifts between oxic and anoxic conditions usually occur in mine tailings (56) and surface sediments (57). Among the four orders that are phylogenetically closely related to “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales,” only the order RBG-16-68-12 harbors the capacity of aerobic respiration. In the domain Archaea, aerobic metabolism has been found in a limited number of lineages, including the deep-sea Thaumarchaeota, microaerophiles within the Micrarchaeota and Parvarchaeota, the haloarchaea in evaporite deposits and brine lakes, specific members of Thermoplasmatales and Thermoproteales, and aerobic and facultatively anaerobic organisms within Sulfolobales (15, 58). Thus, the discovery of aerobic capacity in “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the order RBG-16-68-12 (34) extends the phylogenetic range of this “unusual” feature in Archaea.

Notably, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” has the genetic potential for utilization and degradation of complex carbon sources, including starch and glycogen. Such capacities have also been found in uncultured archaea affiliated with Micrarchaeota and Parvarchaeota populating acid mine environments (2). These findings are reasonable, as the sampled habitats are open environments where inputs of external carbon sources are highly possible. Moreover, “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” could conserve energy through degradation of fatty acids, amino acid metabolism, and oxidation of RISCs. While the oxidation of RISCs represents an important strategy to conserve energy in AMD and associated environments, the release of protons from such oxidative reactions could significantly accelerate the acidification processes in situ (20). As rare taxa have been implicated to execute key ecological functions in AMD systems (49, 59), the less abundant “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” might also act as transcriptionally active taxa and thus contribute to AMD generation via sulfur oxidation.

Moreover, all recovered “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” genomes do not encode proteins conferring the capability for carbon fixation via the WLP, although some members of Methanomassiliicoccales, “Ca. Gimiplasmatales,” and RBG-16-68-12 have been found to possess the bacterial-type H4F WLP and thus may be capable of energy conservation through inorganic carbon assimilation via the bacterial-type H4F WLP. Additionally, the absence of methanogenesis capacity in the “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” genomes provides further evidence that Methanomassiliicoccales are the only known anaerobic methanogens in class Thermoplasmata (34), which may be explained by the acquisition of genes encoding the key methyl-coenzyme M reductase complex along the branch leading to the LACA of Methanomassiliicoccales.

Finally, we revealed the evolutionary paths leading to the physiological divergence among “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and the four closely related orders within Thermoplasmata. The LACA of these five orders might have acquired bacterial-type CODH/ACS complex genes through the ancient interdomain horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event, strengthening the viewpoint that gene acquisitions from bacteria provided the key innovations in the evolution of Archaea (60). Subsequently, several key loss events of terminal oxidase and CODH/ACS complex genes shaped the distribution of aerobic metabolism and WLP in these five orders, respectively, further supporting the importance of genome streamlining processes in shaping genome contents in Archaea (61).

Concluding remarks.

Our analyses have revealed the environmental distribution and potential ecological roles of “Ca. Sysuiplasmatales” and provided important insights into the evolution of this novel order and its evolutionary relationships with other closely related orders within class Thermoplasmata. Future cultivation attempts are needed to confirm our metagenomics-based inference of metabolic capacities. Such efforts could be challenging, as members of the Thermoplasmata are often difficult to isolate. Meanwhile, in situ activity measurements, particularly when combined with multiomics analyses, could also provide additional support to functions predicted by gene information. Ultimately, the continuing discovery, genomic characterization, and subsequent functional validation of novel acidophilic prokaryotic lineages will further our knowledge of the microbial diversity and ecology in the model AMD system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling, DNA extraction, and sequencing.

Tailing and sediment samples (0 to 10 cm depth) were collected from the Chengmenshan Copper Mine (29°41′ N, 115°49′ E; samples libTUT1, TUT18, TUT19, and UT3) and Yongping Copper Mine (28°15′ N, 117°50′ E; samples YP2 and YP4), China, respectively. Samples were collected into sterile 50-ml centrifuge tubes and kept on dry ice for transportation to the laboratory. Physicochemical characteristics were determined as described previously (62, 63). All tailing and sediment samples were characterized with low pH (2.6 to 3.1) and high levels of sulfate (18 to 111 g kg−1), total iron (4.3 to 36.1 g kg−1), and heavy metals (Pb, Zn, Cu, and Cd) (Data Set S1), which are typical of AMD environments (64, 65). Community genomic DNA of the sediment and tailing samples was extracted using the FastDNA spin kit (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the method described by Tan et al. (66), respectively. Quality-checked DNA was sent to the Guangdong Magigene Company for construction of standard 300-bp fragment libraries, which were subsequently sequenced using a 150-bp paired‐end sequencing strategy on an Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform.

Metagenomic analysis.

Raw metagenomic reads were preprocessed through in-house Perl scripts and Sickle with the parameters -q 30 -l 50 (67). Then, the high-quality metagenomic reads for each sample were assembled individually using SPAdes (version 3.11.0) with the parameters -k 21, 33, 55, 77, 99 –meta or -k 21, 33, 55, 77, 99,127 –meta to obtain the scaffolds, which were binned based on sequence composition and scaffold coverage using MetaBAT (version 2.12.1) (68), MaxBin (version 2.2.2) (69), and Concoct (version 0.4.0) (70) with default parameters. The consensus binning software DASTool (version 1.1.2) (71) was utilized to combine the resulting bins to obtain the preliminary genome bins. The phylogenomic analysis based on the concatenated alignment of 122 archaeon-specific conserved marker genes generated by GTDB-Tk (72) was performed using IQtree (version 1.6.10) (73) to determine the phylogenetic placement of these genome bins, and eight of them which formed a distinct clade within Thermoplasmata and grouped phylogenetically closely to the orders Methanomassiliicoccales, “Candidatus Gimiplasmatales,” SG8-5, and RBG-16-68-12 were selected. They were reassembled based on the mapped reads using BBMap (74) as previously reported (48) and were manually curated to remove contaminations. Their genome completeness, contamination, and strain heterogeneity were assessed using CheckM (version 1.1.3) (75). These eight curated genomes were retained for further analyses.

The relative abundance of each MAG was determined by calculating the relative abundance of its rpS3 protein as previously reported (76). For each sample, all rpS3 proteins were identified by AMPHORA2 and clustered by USEARCH with 99% identity (77). Then, we selected the representative scaffold in protein cluster of each rpS3 as the read mapping target for abundance calculation, which was performed by BBMap with the parameters minid = 0.97, local = t. The relative abundance of each bin was determined as the coverage of the corresponding rpS3 divided by the total coverage of all rpS3 in the community.

Functional annotation and metabolic reconstruction of MAGs.

The open reading frames (ORFs) in scaffolds from each MAG were determined using Prodigal (version 2.6.3) with the -p single option, and the generated ORFs were annotated through comparisons with the KEGG, EggNOG, NCBI-nr, and Pfam databases using DIAMOND with E values of ≤1e−5 (78). The repertoires of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) were investigated through the dbCAN2 meta server (79). rRNA genes and tRNA genes were predicted using Barrnap (https://github.com/Victorian-Bioinformatics-Consortium/barrnap) and the tRNAscan-SE 2.0 web server, respectively (80). In addition, the assignment of functional domains to all proteins was conducted through the EBI InterProScan server (81). Metabolic pathways were constructed for the eight novel order-level MAGs based on these gene annotation results.

Phylogenomic and phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA genes was conducted using sequences from all novel-order genomes and other archaeal genomes, as well as novel-order-related sequences from NCBI GenBank. Sequences were aligned using the SINA alignment algorithm on the SILVA web interface, and then the alignment was filtered to remove columns with more than 95% gaps using TrimAL v1.4 (82). The maximum-likelihood tree was constructed using IQtree (version 1.6.10) with the parameters GTR+F+R4 -alrt 1000 -bb 1000 (73). Phylogenomic analysis was performed with 16 ribosomal proteins (83) and 122 archaeon-specific conserved marker genes identified by GTDB-Tk (72), respectively. The MAGs with fewer than 8 of the 16 ribosomal proteins were removed. The 16 ribosomal proteins were aligned individually using MUSCLE (version 3.8.31) with default parameters (84) and subsequently filtered using TrimAL v1.4 with the parameters -gt 0.95 -cons 50 (82). Then, the filtered alignments were concatenated in order, and the phylogenomic tree was inferred based on the concatenated alignment using IQtree (version 1.6.10) with the parameters LG+R10 -alrt 1000 -bb 1000 (73). Meanwhile, the concatenated alignment of 122 archaeon-specific conserved marker genes was generated using GTDB-Tk, and the phylogenomic tree was constructed based on the concatenated alignment using IQtree (version 1.6.10) with the parameters LG+F+R10 -alrt 1000 -bb 1000. For phylogenetic analysis of CODH/ACS complex genes, reference data sets were derived from the work of Adam et al. (27) and Hu et al. (11). Combined with the AcsE-CdhDE genes detected in this study, sequences were aligned and trimmed using MUSCLE and TrimAL with the parameters described above. The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQtree (version 1.6.10) with the parameters LG+F+R8 -alrt 1000 -bb 1000. The phylogenetic tree was rooted according to reference 63. All trees were uploaded to iTOL for visualization and formatting (85).

Comparative genomics.

Representative genomes of Thermoplasmata in the GTDB database were downloaded (86). The values of average amino acid identity and OrthoANI among the genomes of this novel order and the closely related orders Methanomassiliicoccales, “Candidatus Gimiplasmatales,” SG8-5, and RBG-16-68-12 were calculated by CompareM (https://github.com/dparks1134/CompareM) and OrthoANIu (87), respectively. For COUNT analysis, only genomes from Thermoplasmata with >85% completeness were taken into consideration, and 78 draft genomes from GTDB and eight novel-order MAGs were kept for further analyses. An all-against-all genome BLAST search was employed to generate the reciprocal best BLAST hits (rBBHs) based on the threshold E value <1e−10 and a local amino acid identity of ≥25%. Then, these protein pairs were globally aligned using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm in EMBOSS v6.5.7 based on a threshold of ≥25% global amino acid identity (60), and the Markov clustering (MCL) algorithm (−I [inflation value], 1.4) was employed to yield protein clusters based on rBBHs (88), thereby generating 33,527 gene families with 21,577 orphans. The genome tree (based on 122 archaeon-specific conserved marker genes) for COUNT was constructed as described above, and evolutionary histories of these archaeal lineages were inferred using COUNT v9.1106 with Dollo parsimony (89).

Data availability.

All sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject number PRJNA719487. In particular, the raw metagenomic sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SRR14316976, SRR14318494, SRR14320033, and SRR14318403, and the eight described MAGs have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JAGVSJ000000000, JAHBML000000000, JAHDZZ000000000, JAHEAA000000000, JAHEAB000000000, JAHEAC000000000, JAHEAD000000000, and JAHEAE000000000.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31570500, 31870111, and 40930212).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Li-Nan Huang, Email: eseshln@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Robert M. Kelly, North Carolina State University

REFERENCES

- 1.Hatzenpichler R, Lebedeva EV, Spieck E, Stoecker K, Richter A, Daims H, Wagner M. 2008. A moderately thermophilic ammonia-oxidizing crenarchaeote from a hot spring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:2134–2139. 10.1073/pnas.0708857105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen LX, Mendez-Garcia C, Dombrowski N, Servin-Garciduenas LE, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Fang BZ, Luo ZH, Tan S, Zhi XY, Hua ZS, Martinez-Romero E, Woyke T, Huang LN, Sanchez J, Pelaez AI, Ferrer M, Baker BJ, Shu WS. 2018. Metabolic versatility of small archaea Micrarchaeota and Parvarchaeota. ISME J 12:756–775. 10.1038/s41396-017-0002-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narasingarao P, Podell S, Ugalde JA, Brochier-Armanet C, Emerson JB, Brocks JJ, Heidelberg KB, Banfield JF, Allen EE. 2012. De novo metagenomic assembly reveals abundant novel major lineage of Archaea in hypersaline microbial communities. ISME J 6:81–93. 10.1038/ismej.2011.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karner M, DeLong EF, Karl DM. 2001. Archaeal dominance in the mesopelagic zone of the Pacific Ocean. Nature 409:507–509. 10.1038/35054051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seitz KW, Lazar CS, Hinrichs KU, Teske AP, Baker BJ. 2016. Genomic reconstruction of a novel, deeply branched sediment archaeal phylum with pathways for acetogenesis and sulfur reduction. ISME J 10:1696–1705. 10.1038/ismej.2015.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen XP, Zhu YG, Xia Y, Shen JP, He JZ. 2008. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea: important players in paddy rhizosphere soil? Environ Microbiol 10:1978–1987. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spang A, Caceres EF, Ettema TJG. 2017. Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. Science 357:eaaf3883. 10.1126/science.aaf3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker BJ, De Anda V, Seitz KW, Dombrowski N, Santoro AE, Lloyd KG. 2020. Diversity, ecology and evolution of Archaea. Nat Microbiol 5:887–900. 10.1038/s41564-020-0715-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis WH, Tahon G, Geesink P, Sousa DZ, Ettema TJG. 2021. Innovations to culturing the uncultured microbial majority. Nat Rev Microbiol 19:225–240. 10.1038/s41579-020-00458-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castelle CJ, Banfield JF. 2018. Major new microbial groups expand diversity and alter our understanding of the tree of life. Cell 172:1181–1197. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu W, Pan J, Wang B, Guo J, Li M, Xu M. 2021. Metagenomic insights into the metabolism and evolution of a new Thermoplasmata order (Candidatus Gimiplasmatales). Environ Microbiol 23:3695–3709. 10.1111/1462-2920.15349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam PS, Borrel G, Brochier-Armanet C, Gribaldo S. 2017. The growing tree of Archaea: new perspectives on their diversity, evolution and ecology. ISME J 11:2407–2425. 10.1038/ismej.2017.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golyshina OV, Lunsdorf H, Kublanov IV, Goldenstein NI, Hinrichs KU, Golyshin PN. 2016. The novel extremely acidophilic, cell-wall-deficient archaeon Cuniculiplasma divulgatum gen. nov., sp. nov. represents a new family, Cuniculiplasmataceae fam. nov., of the order Thermoplasmatales. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:332–340. 10.1099/ijsem.0.000725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golyshina OV, Timmis KN. 2005. Ferroplasma and relatives, recently discovered cell wall-lacking archaea making a living in extremely acid, heavy metal-rich environments. Environ Microbiol 7:1277–1288. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teske A. 2018. Aerobic Archaea in iron-rich springs. Nat Microbiol 3:646–647. 10.1038/s41564-018-0168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colman DR, Poudel S, Hamilton TL, Havig JR, Selensky MJ, Shock EL, Boyd ES. 2018. Geobiological feedbacks and the evolution of thermoacidophiles. ISME J 12:225–236. 10.1038/ismej.2017.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denef VJ, Mueller RS, Banfield JF. 2010. AMD biofilms: using model communities to study microbial evolution and ecological complexity in nature. ISME J 4:599–610. 10.1038/ismej.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang LN, Kuang JL, Shu WS. 2016. Microbial ecology and evolution in the acid mine drainage model system. Trends Microbiol 24:581–593. 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker BJ, Tyson GW, Webb RI, Flanagan J, Hugenholtz P, Allen EE, Banfield JF. 2006. Lineages of acidophilic Archaea revealed by community genomic analysis. Science 314:1933–1935. 10.1126/science.1132690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker BJ, Banfield JF. 2003. Microbial communities in acid mine drainage. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 44:139–152. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konstantinidis KT, Rossello-Mora R, Amann R. 2017. Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J 11:2399–2406. 10.1038/ismej.2017.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Li Y, Sun Q. 2014. Archaeal and bacterial communities in acid mine drainage from metal-rich abandoned tailing ponds, Tongling, China. Trans Nonferrous Metal Soc China 24:3332–3342. 10.1016/S1003-6326(14)63474-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siering PL, Wolfe GV, Wilson MS, Yip AN, Carey CM, Wardman CD, Shapiro RS, Stedman KM, Kyle J, Yuan T, Van Nostrand JD, He Z, Zhou J. 2013. Microbial biogeochemistry of Boiling Springs Lake: a physically dynamic, oligotrophic, low-pH geothermal ecosystem. Geobiology 11:356–376. 10.1111/gbi.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato S, Itoh T, Yamagishi A. 2011. Archaeal diversity in a terrestrial acidic spring field revealed by a novel PCR primer targeting archaeal 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett 319:34–43. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray AE, Freudenstein J, Gribaldo S, Hatzenpichler R, Hugenholtz P, Kämpfer P, Konstantinidis KT, Lane CE, Papke RT, Parks DH, Rossello-Mora R, Stott MB, Sutcliffe IC, Thrash JC, Venter SN, Whitman WB, Acinas SG, Amann RI, Anantharaman K, Armengaud J, Baker BJ, Barco RA, Bode HB, Boyd ES, Brady CL, Carini P, Chain PSG, Colman DR, DeAngelis KM, de Los Rios MA, Estrada-de Los Santos P, Dunlap CA, Eisen JA, Emerson D, Ettema TJG, Eveillard D, Girguis PR, Hentschel U, Hollibaugh JT, Hug LA, Inskeep WP, Ivanova EP, Klenk H-P, Li W-J, Lloyd KG, Löffler FE, Makhalanyane TP, Moser DP, Nunoura T, Palmer M, et al. 2020. Roadmap for naming uncultivated Archaea and Bacteria. Nat Microbiol 5:987–994. 10.1038/s41564-020-0733-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rivière L, Moreau P, Allmann S, Hahn M, Biran M, Plazolles N, Franconi J-M, Boshart M, Bringaud F. 2009. Acetate produced in the mitochondrion is the essential precursor for lipid biosynthesis in procyclic trypanosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:12694–12699. 10.1073/pnas.0903355106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adam PS, Borrel G, Gribaldo S. 2018. Evolutionary history of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase/acetyl-CoA synthase, one of the oldest enzymatic complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:E1166–E1173. 10.1073/pnas.1716667115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinchuk GE, Rodionov DA, Yang C, Li X, Osterman AL, Dervyn E, Geydebrekht OV, Reed SB, Romine MF, Collart FR, Scott JH, Fredrickson JK, Beliaev AS. 2009. Genomic reconstruction of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 metabolism reveals a previously uncharacterized machinery for lactate utilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:2874–2879. 10.1073/pnas.0806798106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schippers A, Sand W. 1999. Bacterial leaching of metal sulfides proceeds by two indirect mechanisms via thiosulfate or via polysulfides and sulfur. Appl Environ Microbiol 65:319–321. 10.1128/AEM.65.1.319-321.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spallarossa A, Forlani F, Carpen A, Armirotti A, Pagani S, Bolognesi M, Bordo D. 2004. The “rhodanese” fold and catalytic mechanism of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferases: crystal structure of SseA from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 335:583–593. 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.10.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marcia M, Ermler U, Peng G, Michel H. 2009. The structure of Aquifex aeolicus sulfide quinone oxidoreductase, a basis to understand sulfide detoxification and respiration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:9625–9630. 10.1073/pnas.0904165106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bueno E, Mesa S, Bedmar EJ, Richardson DJ, Delgado MJ. 2012. Bacterial adaptation of respiration from oxic to microoxic and anoxic conditions: redox control. Antioxid Redox Signal 16:819–852. 10.1089/ars.2011.4051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hille R, Dingwall S, Wilcoxen J. 2015. The aerobic CO dehydrogenase from Oligotropha carboxidovorans. J Biol Inorg Chem 20:243–251. 10.1007/s00775-014-1188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zinke LA, Evans PN, Santos‐Medellín C, Schroeder AL, Parks DH, Varner RK, Rich VI, Tyson GW, Emerson JB. 2021. Evidence for non‐methanogenic metabolisms in globally distributed archaeal clades basal to the Methanomassiliicoccales. Environ Microbiol 23:340–357. 10.1111/1462-2920.15316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumi R, Atomi H, Driessen AJM, van der Oost J. 2011. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in Archaea—biochemical and evolutionary implications. Res Microbiol 162:39–52. 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clomburg JM, Qian M, Tan ZG, Cheong S, Gonzalez R. 2019. The isoprenoid alcohol pathway, a synthetic route for isoprenoid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 116:12810–12815. 10.1073/pnas.1821004116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinokur JM, Cummins MC, Korman TP, Bowie JU. 2016. An adaptation to life in acid through a novel mevalonate pathway. Sci Rep 6:39737–39711. 10.1038/srep39737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lloyd KG, Schreiber L, Petersen DG, Kjeldsen KU, Lever MA, Steen AD, Stepanauskas R, Richter M, Kleindienst S, Lenk S, Schramm A, Jørgensen BB. 2013. Predominant archaea in marine sediments degrade detrital proteins. Nature 496:215–218. 10.1038/nature12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Hug LA, Brown CT, Wilkins MJ, Frischkorn KR, Tringe SG, Singh A, Markillie LM, Taylor RC, Williams KH, Banfield JF. 2015. Genomic expansion of domain Archaea highlights roles for organisms from new phyla in anaerobic carbon cycling. Curr Biol 25:690–701. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang S, Huang H, Moll J, Thauer RK. 2010. NADP+ reduction with reduced ferredoxin and NADP+ reduction with NADH are coupled via an electron-bifurcating enzyme complex in Clostridium kluyveri. J Bacteriol 192:5115–5123. 10.1128/JB.00612-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castelle CJ, Hug LA, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Williams KH, Wu D, Tringe SG, Singer SW, Eisen JA, Banfield JF. 2013. Extraordinary phylogenetic diversity and metabolic versatility in aquifer sediment. Nat Commun 4:2120–2110. 10.1038/ncomms3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battchikova N, Eisenhut M, Aro EM. 2011. Cyanobacterial NDH-1 complexes: novel insights and remaining puzzles. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807:935–944. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan Z, Wang M, Ferry JG. 2017. A ferredoxin- and F420H2-dependent, electron-bifurcating, heterodisulfide reductase with homologs in the domains Bacteria and Archaea. mBio 8:e02285-16. 10.1128/mBio.02285-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osorio H, Mangold S, Denis Y, Nancucheo I, Esparza M, Johnson DB, Bonnefoy V, Dopson M, Holmes DS. 2013. Anaerobic sulfur metabolism coupled to dissimilatory iron reduction in the extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2172–2181. 10.1128/AEM.03057-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christel S, Fridlund J, Buetti-Dinh A, Buck M, Watkin EL, Dopson M. 2016. RNA transcript sequencing reveals inorganic sulfur compound oxidation pathways in the acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans. FEMS Microbiol Lett 363:fnw057. 10.1093/femsle/fnw057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Evans PN, Boyd JA, Leu AO, Woodcroft BJ, Parks DH, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2019. An evolving view of methane metabolism in the Archaea. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:219–232. 10.1038/s41579-018-0136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borrel G, Adam PS, McKay LJ, Chen L-X, Sierra-García IN, Sieber CMK, Letourneur Q, Ghozlane A, Andersen GL, Li W-J, Hallam SJ, Muyzer G, de Oliveira VM, Inskeep WP, Banfield JF, Gribaldo S. 2019. Wide diversity of methane and short-chain alkane metabolisms in uncultured archaea. Nat Microbiol 4:603–613. 10.1038/s41564-019-0363-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan S, Liu J, Fang Y, Hedlund BP, Lian ZH, Huang LY, Li JT, Huang LN, Li WJ, Jiang HC, Dong HL, Shu WS. 2019. Insights into ecological role of a new deltaproteobacterial order Candidatus Acidulodesulfobacterales by metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. ISME J 13:2044–2057. 10.1038/s41396-019-0415-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hua ZS, Han YJ, Chen LX, Liu J, Hu M, Li SJ, Kuang JL, Chain PS, Huang LN, Shu WS. 2015. Ecological roles of dominant and rare prokaryotes in acid mine drainage revealed by metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. ISME J 9:1280–1294. 10.1038/ismej.2014.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen LX, Hu M, Huang LN, Hua ZS, Kuang JL, Li SJ, Shu WS. 2015. Comparative metagenomic and metatranscriptomic analyses of microbial communities in acid mine drainage. ISME J 9:1579–1592. 10.1038/ismej.2014.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ferrer A, Orellana O, Levicán G. 2016. Oxidative stress and metal tolerance in extreme acidophiles, p 63–76. In Johnson DB, Quatrini R (ed), Acidophiles: life in extremely acidic environments. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, UK. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lumppio HL, Shenvi NV, Summers AO, Voordouw G, Kurtz DM, Jr.. 2001. Rubrerythrin and rubredoxin oxidoreductase in Desulfovibrio vulgaris: a novel oxidative stress protection system. J Bacteriol 183:101–108. 10.1128/JB.183.1.101-108.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weinberg MV, Jenney FE, Jr, Cui X, Adams MW. 2004. Rubrerythrin from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus is a rubredoxin-dependent, iron-containing peroxidase. J Bacteriol 186:7888–7895. 10.1128/JB.186.23.7888-7895.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berg IA. 2011. Ecological aspects of the distribution of different autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1925–1936. 10.1128/AEM.02473-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Golyshina OV. 2011. Environmental, biogeographic, and biochemical patterns of archaea of the family Ferroplasmaceae. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5071–5078. 10.1128/AEM.00726-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fortin D, Praharaj T. 2005. Role of microbial activity in Fe and S cycling in sub-oxic to anoxic sulfide-rich mine tailings. J Nucl Radiochem Sci 6:39–42. 10.14494/jnrs2000.6.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brune A, Frenzel P, Cypionka H. 2000. Life at the oxic–anoxic interface microbial activities and adaptations. FEMS Microbiol Rev 24:691–710. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lewis AM, Recalde A, Brasen C, Counts JA, Nussbaum P, Bost J, Schocke L, Shen L, Willard DJ, Quax TEF, Peeters E, Siebers B, Albers SV, Kelly RM. 2021. The biology of thermoacidophilic archaea from the order Sulfolobales. FEMS Microbiol Rev 45:fuaa063. 10.1093/femsre/fuaa063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tyson GW, Lo I, Baker BJ, Allen EE, Hugenholtz P, Banfield JF. 2005. Genome-directed isolation of the key nitrogen fixer Leptospirillum ferrodiazotrophum sp. nov. from an acidophilic microbial community. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:6319–6324. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6319-6324.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson-Sathi S, Sousa FL, Roettger M, Lozada-Chavez N, Thiergart T, Janssen A, Bryant D, Landan G, Schonheit P, Siebers B, McInerney JO, Martin WF. 2015. Origins of major archaeal clades correspond to gene acquisitions from bacteria. Nature 517:77–80. 10.1038/nature13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Csuros M, Miklos I. 2009. Streamlining and large ancestral genomes in Archaea inferred with a phylogenetic birth-and-death model. Mol Biol Evol 26:2087–2095. 10.1093/molbev/msp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang TT, Liu J, Chen WC, Chen X, Shu HY, Jia P, Liao B, Shu WS, Li JT. 2017. Changes in microbial community composition following phytostabilization of an extremely acidic Cu mine tailings. Soil Biol Biochem 114:52–58. 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gao SM, Schippers A, Chen N, Yuan Y, Zhang MM, Li Q, Liao B, Shu WS, Huang LN. 2020. Depth-related variability in viral communities in highly stratified sulfidic mine tailings. Microbiome 8:89–13. 10.1186/s40168-020-00848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johnson DB, Hallberg KB. 2003. The microbiology of acidic mine waters. Res Microbiol 154:466–473. 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuang JL, Huang LN, Chen LX, Hua ZS, Li SJ, Hu M, Li JT, Shu WS. 2013. Contemporary environmental variation determines microbial diversity patterns in acid mine drainage. ISME J 7:1038–1050. 10.1038/ismej.2012.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tan GL, Shu WS, Hallberg KB, Li F, Lan CY, Zhou WH, Huang LN. 2008. Culturable and molecular phylogenetic diversity of microorganisms in an open-dumped, extremely acidic Pb/Zn mine tailings. Extremophiles 12:657–664. 10.1007/s00792-008-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Joshi NA, Fass JN. 2011. Sickle: a sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files. https://githubcom/najoshi/sickle.

- 68.Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. 2015. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 3:e1165. 10.7717/peerj.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu YW, Simmons BA, Singer SW. 2016. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32:605–607. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alneberg J, Bjarnason BS, de Bruijn I, Schirmer M, Quick J, Ijaz UZ, Lahti L, Loman NJ, Andersson AF, Quince C. 2014. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat Methods 11:1144–1146. 10.1038/nmeth.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sieber CMK, Probst AJ, Sharrar A, Thomas BC, Hess M, Tringe SG, Banfield JF. 2018. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat Microbiol 3:836–843. 10.1038/s41564-018-0171-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. 2020. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 36:1925–1927. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bushnell B. 2014. BBmap: a fast, accurate, splice-aware aligner. Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

- 75.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25:1043–1055. 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Diamond S, Andeer PF, Li Z, Crits-Christoph A, Burstein D, Anantharaman K, Lane KR, Thomas BC, Pan C, Northen TR, Banfield JF. 2019. Mediterranean grassland soil C-N compound turnover is dependent on rainfall and depth, and is mediated by genomically divergent microorganisms. Nat Microbiol 4:1356–1367. 10.1038/s41564-019-0449-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu M, Scott AJ. 2012. Phylogenomic analysis of bacterial and archaeal sequences with AMPHORA2. Bioinformatics 28:1033–1034. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods 12:59–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang H, Yohe T, Huang L, Entwistle S, Wu P, Yang Z, Busk PK, Xu Y, Yin Y. 2018. dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 46:W95–W101. 10.1093/nar/gky418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lowe TM, Chan PP. 2016. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 44:W54–W57. 10.1093/nar/gkw413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, Lopez R. 2005. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res 33:W116–W120. 10.1093/nar/gki442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25:1972–1973. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hug LA, Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, Sharon I, Frischkorn KR, Williams KH, Tringe SG, Banfield JF. 2013. Community genomic analyses constrain the distribution of metabolic traits across the Chloroflexi phylum and indicate roles in sediment carbon cycling. Microbiome 1:22. 10.1186/2049-2618-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Letunic I, Bork P. 2007. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23:127–128. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil PA, Hugenholtz P. 2018. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol 36:996–1004. 10.1038/nbt.4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoon SH, Ha SM, Lim J, Kwon S, Chun J. 2017. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110:1281–1286. 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hua ZS, Qu YN, Zhu Q, Zhou EM, Qi YL, Yin YR, Rao YZ, Tian Y, Li YX, Liu L, Castelle CJ, Hedlund BP, Shu WS, Knight R, Li WJ. 2018. Genomic inference of the metabolism and evolution of the archaeal phylum Aigarchaeota. Nat Commun 9:2832. 10.1038/s41467-018-05284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Csurös M. 2010. Count: evolutionary analysis of phylogenetic profiles with parsimony and likelihood. Bioinformatics 26:1910–1912. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental text, Fig. S1 to S6. Download AEM.01065-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.5 MB (1.5MB, pdf)

Data Sets S1 to S9. Download AEM.01065-21-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 1.1 MB (1.1MB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

All sequencing data generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject number PRJNA719487. In particular, the raw metagenomic sequences have been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive under accession numbers SRR14316976, SRR14318494, SRR14320033, and SRR14318403, and the eight described MAGs have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JAGVSJ000000000, JAHBML000000000, JAHDZZ000000000, JAHEAA000000000, JAHEAB000000000, JAHEAC000000000, JAHEAD000000000, and JAHEAE000000000.