Abstract

Introduction

The clinical effect of pharmacotherapy on prostate morphometric parameters is largely unknown. The sole exception is 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARI) that reduce prostate volume and prostate-specific antigen (PSA). This review assesses the effect of pharmacotherapy on prostate parameters effect on prostate parameters, namely total prostate volume (TPV), transitional zone volume (TZV), PSA and prostate perfusion.

Material and methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting on morphometric parameters’ changes after pharmacotherapy, as primary or secondary outcomes. The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. RCTs’ quality was assessed by the Cochrane tool and the criteria of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The effect magnitude was expressed as standard mean difference (SMD). The study protocol was published on PROSPERO (CRD42020170172).

Results

Sixty-seven RCTs were included in the review and 18 in the meta-analysis. The changes after alpha-blockers are comparable to placebo. Long-term studies reporting significant changes from baseline, result from physiologic growth. Finasteride and dutasteride demonstrated large effect sizes in TPV reduction ([SMD]: -1.15 (95% CI: -1.26 to -1.04, p <0.001, and [SMD]:-0.66 (95% CI: -0.83 to -0.49, p <0.001, respectively), and similar PSA reductions. Dutasteride’s effect appears earlier (1st vs 3rd month), the changes reach a maximum at month 12 and are sustained thereafter. Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors have no effect on morphometric parameters. Phytotherapy’s effect on TPV is non-significant [SMD]: 0.12 (95% CI: -0.03 to 0.27, p = 0.13). Atorvastatin reduces TPV as compared to placebo (-11.7% vs +2.5%, p <0.01). Co-administration of testosterone with dutasteride spares the prostate from the androgenic stimulation as both TPV and PSA are reduced significantly.

Conclusions

The 5-ARIs show large effect size in reducing TPV and PSA. Tamsulosin improves perfusion but no other effect is evident. PDE-5 inhibitors and phytotherapy do not affect morphometric parameters. Atorvastatin reduces TPV and PSA as opposed to testosterone supplementation.

Keywords: prostate volume changes, prostate perfusion, lower urinary tract pharmacotherapy, morphometric parameters

INTRODUCTION

Benign prostatic obstruction (BPO) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men older than 50 years [1]. Benign prostatic enlargement (BPE) is defined as prostatic enlargement due to histologic benign prostatic hyperplasia [2]. BPO involves the static component or the physical mass of the prostate and the dynamic component or smooth muscle tone of the prostate stroma and the bladder neck [1, 2]. It is reasonable to assume a potential relation between prostate size, degree of obstruction and LUTS severity, but population-based studies failed to demonstrate a direct link [3]. Prostate morphometric parameters are prognostic indicators of BPE progression. Data analysis from the placebo arm of Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial showed that men with baseline total prostate volume (TPV) 31 ml and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) of 1.6 ng/dl or greater are at significantly higher risk of BPE progression, defined as a 4-point or more increase in AUA-SS, acute urinary retention, urinary incontinence, renal insufficiency or recurrent urinary tract infections [4]. Baseline flow rate, post-void residual and age were the additional predictors. TPV and PSA are among the baseline factors which could predict conservative treatment failure and/or the need for combination therapy [5]. Baseline PSA is higher in men with larger prostates and is associated with higher annual volume increase (2.2%) compared to smaller prostates (1.7%) [6]. However, a multivariate analysis of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging in 242 men without prostate cancer, reported no correlation between PSA or PSA changes and annual prostate growth rate during 4.2 years of follow-up [6]. The median rate of TPV and PSA change per year was 0.6 ml and 0.03 ng/ml respectively.

Existing data supports the hypothesis that ischemia of the lower urinary tract may cause BPE and LUTS. Azadzoi et al. were first to document bladder dysfunction and increased prostate contractility in an animal model of pelvic atherosclerosis [7]. The underlying mechanism of ischemic injury involves oxidative stress, free radical injury to smooth muscle cells, epithelium, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and nerve fibers, impairment of the nitric oxide (NO/cGMP) pathway, activation of degenerative processes and deposition of collagen [7]. Chronic ischemia induces prostate stromal fibrosis, decreases cGMP and increases prostate tissue sensitivity to contractile stimuli [7].

The clinical effect of pharmacotherapy on prostate morphometric parameters is largely unknown. The sole exception is 5α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARI) which reduce TPV, transitional zone volume (TZV) and PSA. There is preclinical evidence that all medications influence prostate volume or perfusion. Experiments have shown the anti-apoptotic effect of sympathomimetics, and the potent apoptotic effect on human prostate cancer cell cultures of quinazoline-based α-blockers [8].

Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors influence prostate cell proliferation via upregulation of NO/cGMP and Rho-kinase activity [9, 10]. Evidence supports that finasteride reduces prostate blood flow via downregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [11]. Tamsulosin antagonizes vesical arteries adrenoceptors, thus improving LUT perfusion [12]. PDE5 inhibitors improve perfusion via the reduction of endothelin-1 levels and regulation of vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation [10].

This review aims to investigate the effect of both urological and non-urological medication on prostate morphometric parameters, namely TPV, TZV, PSA and prostate perfusion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Literature search

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [13]. The Embase, MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central (Cochrane Health Technology Assessment, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Economics Evaluations Database) and Google Scholar were searched with no restriction on publication date. Additional sources for articles were the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles.

Study selection

We included randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) of adult men with LUTS due to BPE, who received pharmacotherapy, and reported post-intervention changes of prostate parameters as primary or secondary outcome. The included studies had 10 participants minimum, were written in English language and used ultrasound or MRI to assess morphometric parameters. There was no restriction in study duration. In the event of open extension of double-blind studies, only data from the double-blind period were included. If data were not reported separately, studies were excluded.

Two reviewers (AG and DC) screened the titles and abstracts of identified records, and the full text of potentially eligible records was evaluated using a standardized form. Disagreement was resolved by discussion. If there was no agreement, a third independent party acted as an arbitrator (VS).

Data extraction

Data from eligible studies were extracted in duplicate. Discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. The variables assessed included the year of publication, number of randomized subjects, number of subjects who completed the follow up, baseline values and post treatment changes in morphometric parameters presented as mean (±standard deviation) and percentage changes from baseline.

Risk of bias and study quality assessment

Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed using the revised version of Cochrane Collaboration’s RoB Assessment tool [14]. Two reviewers (AG and DC) independently assessed RoB in each study, while a third reviewer (VS) acted as an arbitrator. The RoB was considered high if the confounder had not been considered by the individual study. The RoB tables were developed in Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan-Informatics and Knowledge Management Department, Cochrane, London, UK).

To ensure reliability and validity of measures and reported measurements, each included RCT had an overall rating based on the criteria developed by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The ratings were ‘Low-risk’, ‘Moderate-risk’ or ‘High-risk’ [15, 16]. The RCTs should have been characterized as low risk in measurement bias (points 3d & 3e) based on the criteria developed by AHRQ.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the post-intervention changes in TPV. The secondary outcomes were the changes in TZV, PSA and prostate perfusion as defined by the trialist. Owing to the expected heterogeneity, a narrative synthesis of all included studies was planned [17]. Data are presented as post-treatment absolute mean changes (±SD) and percentage changes.

Statistical heterogeneity was tested using chi-square test. A value of p <0.10 or I2 >50% was used to define heterogeneity. A list of potential confounders was developed a priori: use of LUTS-related medications, follow-up duration, LUTS not related to BPE, previous catheter use, previous LUT surgery and history of LUT malignancy.

A meta-analysis was considered for each endpoint if two or more RCTs had similar study design, dosing scheme and follow-up duration. Meta-analysis was conducted using RevMan. The effect magnitude was expressed as standard mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for continuous outcomes. The treatment effect size was considered small for SMD values of 0–0.2, moderate for SMD range 0.2–0.8 and large if SMD was >0.8.

RESULTS

Evidence acquisition: Study selection

Sixty-seven RCTs were eligible for inclusion (Figure 1). Eighteen were eligible for quantitative synthesis. The search was updated in October 2020.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.

Study characteristics

We identified 28 placebo-controlled RCTs and 39 non-placebo RCTs. Since the included RCTs had 2 or more study arms, we studied 36 active medications versus placebo comparisons and 48 active medications versus active medication comparisons. Phytotherapy’s effect on morphometric parameters was assessed in 18 comparisons, α-blockers’ effect in 18 comparisons, 5-ARI’s effect in 23 comparisons, PDE5’s effect in 6 comparisons, combination treatments in 10 comparisons, while 9 comparisons assessed the effect of non-urological medications. Among them, only 10 trials were powered to assess changes in morphometric parameters, while 57 reported a morphometric parameter change as secondary outcome. The characteristics of included RCTs are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of included trials

| Study, [reference] | Comparator 1, Daily dosage | Comparator 2, Daily dosage | Comparator 3, Daily dosage | Comparator 4, Daily dosage | No. subjects randomized | Duration of Follow up | Reported parameters | Primary or Secondary endpoints | Study rating based on AHRQ criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lepor 1996, [18] | Terazosin, 10 mg OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Terazosin 10 mg OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | 1230 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| McConnell 2003, [19] | Doxazosin, 4 or 8 mg OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Doxazosin, 4 or 8 mg OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | 3047 | 4.5 years | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Yokoyama 2012, [20] | Tadalafil. 2.5 mg OD | Tadalafil 5 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD | Placebo | 612 | 3 months | PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Roehrborn 2006, [21] | Alfuzosin, 10 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 1522 | 24 months | PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Roehrborn 2006, [22] | Alfuzosin, 10 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 528 | 3 months | TPV, TZV | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Turkeri 2001, [23] | Doxazosin, 4 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 29 | 4 weeks | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Debruyne 2002, [24] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 704 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Primary | Low Risk |

| Sengupta 2011, [25] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr), OD | n/a | n/a | 46 | 3 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Latil 2015, [26] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Hexanic Extract Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 203 | 3 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Pande 2014, [27] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Silodosin, 8 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 61 | 3 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Karami 2016, [28] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Tadalafil, 20 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 119 | 3 months | PSA | Primary | High Risk |

| Griwan 2014, [99] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Naftopidil, 75 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 60 | 3 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| HIzli 2007, [29] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 40 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Odysanya 2017, [30] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD | n/a | 60 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Morgia 2014, [31] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) |

n/a | 150 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Roehrborn 2010, [32] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | n/a | 3221 | 4 years | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Debruyne 1998, [33] | Alfuzosin SR, OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Alfuzosin SR, OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD |

n/a | 707 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Sakalis 2018, [34] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Solifenacin, 5 or 10 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 69 | 6 months | TPV, TZV, PSA, Perfusion parameters | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Andersen 1995, [35] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 707 | 24 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Nickel 1996, [36] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 613 | 24 months | TPV, PSA | Primary | Low Risk |

| McConnell 1998, [37] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 312 | 48 months | TPV | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Marberger 1998, [38] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 2902 | 24 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Kirby 1992, [39] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Finasteride, 10 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | 66 | 3 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Finasteride group 1993, [40] | Finasteride, 1 mg OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | 750 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Tammela 1995, [41] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 36 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Pannek 1998, [42] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 34 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Marks 1997, [43] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 41 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Gormley 1992, [44] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 597 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Roehrborn 2002, [45] | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 4325 | 24 months | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Na 2012, [46] | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 253 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Tsukamoto 2009, [47] | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 378 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Andriole 2010, [48] | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 8231 | 48 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Nickel 2011, [49] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 1630 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Carraro 1996, [50] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 1098 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Kuo 1998, [51] | Dibenyline, 10 mg BD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 125 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Jeong 2009, [52] | a blocker OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD |

a blocker OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 120 | 24 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Pinggera 2014, [53] | Tadalafil, 5 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 97 | 8 weeks | Perfusion parameters | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Morgia 2018, [54] | Serenoa repens plus Selenium, OD | Tadalafil, 5 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 427 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Kosilov 2019, [55] | Tadalafil, 5 mg OD | Tadalafil, 5 mg OD plus Solifenacin, 10 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 214 | 12 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Oztrurk 2011, [56] | Alfuzosin XL OD | Alfuzosin XL OD plus Sildenafil, 50 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 100 | 3 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Joo 2012, [57] | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 216 | 12 months | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Choi 2016, [58] | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 118 | 12 months | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Mohanty 2006, [59] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Finasteride, 5 mg OD |

Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 106 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Yamanishi 2017, [60] | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD plus imidafenacin, 0.2 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 163 | 24 weeks | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Ryu 2014, [61] | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg OD plus Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 120 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Argirovic 2013, [62] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD |

n/a | 184 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Beiraghdar 2017, [63] | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 86 | 2 weeks | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Berges 1995, [64] | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 163 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Safarinejad 2005, [65] | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 620 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Bent 2006, [66] | Serenoa repens, 160 mg BD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 225 | 12 months | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Marks 2000, [67] | Serenoa repens | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 44 | 24 weeks | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Ye 2019, [68] | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 325 | 24 weeks | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Zhang 2008, [69] | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr) | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 49 | 4 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Shi 2008, [70] | Serenoa repens | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 94 | 12 weeks | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Guzman 2019, [71] | Phytotherapy (Non-Sr), OD | Terazosin, 5 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 100 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Braeckman 1997, [72] | Serenoa repens, 320 mg OD | Serenoa repens, 160 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 84 | 12 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Allott 2019, [73] | Statin users | Non- Statin users | n/a | n/a | 4106 | 48 months | TPV | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Mills 2007, [74] | Atorvastatin, 80 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 350 | 26 weeks | TPV, TZV, PSA | Secondary | Low Risk |

| Zhang 2015, [75] | Atorvastatin, 20 mg OD | Placebo | n/a | n/a | 81 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Safwat 2018, [76] | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD | Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg OD plus Cholecalciferol 600IU OD |

n/a | n/a | 389 | 24 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Ghadian 2017, [77] | Ω3 300 mg plus Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride 5 mg | Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride 5 mg | n/a | n/a | 100 | 6 months | TPV | Secondary | High Risk |

| Di Silverio 2005, [78] | Finasteride, 5 mg OD | Finasteride, 5 mg OD plus Rofecoxib, 25 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 46 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Goodarzt 2011, [79] | Terazosin, 2 mg OD | Terazosin, 2 mg OD plus Celecoxib, 200 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 160 | 12 weeks | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Jhang 2013, [80] | Doxazosin, 4 mg OD | Doxazosin, 4 mg OD plus Celecoxib, 200 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 122 | 3 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | High Risk |

| Page 2011, [81] | Testosterone 1% 7.5 mg OD plus placebo | Testosterone 1% 7.5 mg OD plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD |

n/a | n/a | 53 | 6 months | TPV, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

| Kacker 2014, [82] | Testosterone plus placebo | Testosterone plus Dutasteride, 0.5 mg OD | n/a | n/a | 23 | 12 months | TPV, PSA | Primary | Moderate Risk |

| Chung 2011, [83] | a blocker OD plus 5ARI | a blocker OD plus 5ARI plus Tolterodine |

n/a | n/a | 137 | 12 months | TPV, TZI, PSA | Secondary | Moderate Risk |

AHRQ – Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; BD – Twice Daily; n/a – not applicable; Non-Sr – other than Serenoa repens; OD – once daily; PSA – prostate-specific antigen; Sr – Serenoa repens; TPV – total prostate volume; TZI – transitional zone index; TZV – transitional zone volume

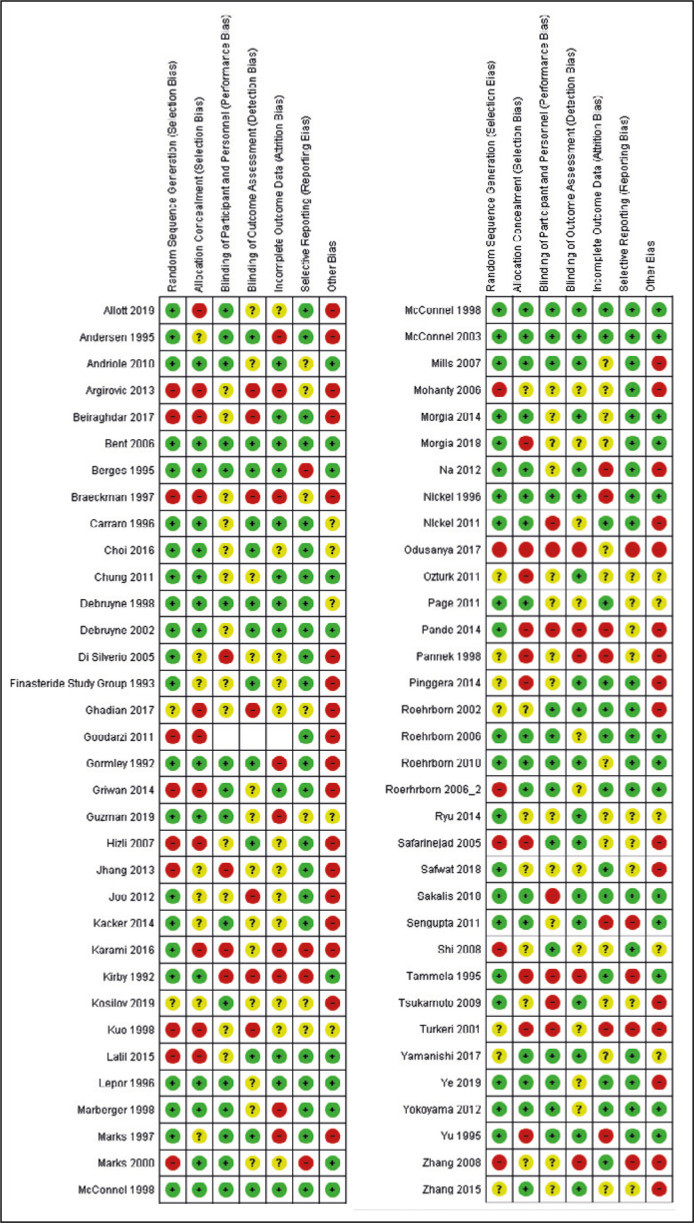

Assessment of study quality

The summary of RoB assessment is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Based on AHRQ criteria, 16 RCTs were graded as low-risk, 31 as moderate-risk and 20 as high-risk (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The risk of bias summary.

Figure 3.

The risk of bias graph.

Table 2.

Detailed rating for included trials based on criteria developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The ratings were ‘Low-risk’, ‘Moderate-risk’ or ‘High-risk’

| Study | Individual Quality Assessment Criteria Ratings | Overall Rating | COI Absent? | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1b | 1c | 2a | 2b | 3a | 3b | 3c | 3d | 3e | 4 | 5 | |||

| Lepor 1996, [18] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| McConnell 2003, [19] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Yokoyama 2012, [20] | LR | UR | LR | UR | LR | HR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Roerhborn 2006, [21] | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Roerhborn 2006, [22] | HR | HR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Turkeri 2001, [23] | UR | UR | HR | HR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | HR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Debruyne 2002, [24] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Sengupta 2011, [25] | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | HR | HR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Latil 2015, [26] | HR | HR | LR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Pande 2014, [27] | LR | HR | LR | LR | HR | HR | UR | LR | LR | LR | HR | UR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Karami 2016, [28] | LR | HR | HR | UR | HR | UR | HR | HR | LR | LR | HR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Hizli 2007, [29] | HR | HR | HR | UR | LR | HR | HR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Odusanya 2017, [30] | HR | HR | LR | HR | UR | HR | HR | HR | LR | LR | UR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Morgia 2014, [31] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Roehrborn 2010, [32] | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Debruyne 1998, [33] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Sakalis 2018, [34] | LR | LR | LR | HR | HR | LR | LR | HR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | Yes |

| Andersen 1995, [35] | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | HR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Nickel 1996, [36] | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | HR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| McConnel 1998, [37] | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Marberger 1998, [38] | LR | UR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | HR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Kirby 1992, [39] | LR | UR | UR | HR | HR | HR | HR | UR | LR | LR | LR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Finasteride group 1993, [40] | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | HR | HR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Tammela 1995, [41] | LR | HR | UR | HR | HR | UR | HR | HR | LR | LR | LR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Pannek 1998, [42] | UR | HR | HR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | HR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Marks 1997, [43] | LR | UR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | HR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Gormley 1992, [44] | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | HR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Roehrborn 2002, [45] | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Na 2012, [46] | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Tsukamoto 2009, [47] | LR | UR | UR | HR | HR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Andriole 2010, [48] | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Nickel 2011, [49] | LR | LR | UR | HR | UR | UR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Carraro 1996, [50] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Kuo 1998, [51] | HR | UR | UR | HR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Jeong 2009, [52] | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Moderate risk | Unclear |

| Jeong 2009, [52] | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Moderate risk | Unclear |

| Pinggera 2014, [53] | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Morgia 2018, [54] | LR | HR | LR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Kosilov 2019, [55] | UR | UR | HR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Ozturk 2011, [56] | UR | HR | LR | UR | UR | LR | HR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Joo 2012, [57] | LR | UR | UR | UR | HR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High risk | Unclear |

| Choi 2016, [58] | LR | LR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Low Risk | Yes |

| Mohanty 2006, [59] | HR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Yamanishi 2017, [60] | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Ryu 2014, [61] | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Argirovic 2013, [62] | HG | HG | HR | UR | UR | HR | UR | HR | LR | LR | HR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Beiraghdar, 2017 [63] | HR | HR | LR | LR | UR | HR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate risk | Yes |

| Berges, 1995 [64] | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate risk | No |

| Safarinejad, 2005 [65] | HR | HR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Yes |

| Bent, 1995 [66] | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Low Risk | Unclear |

| Marks, 2000 [67] | LR | LR | HR | LR | LR | LR | UR | HR | LR | LR | UR | HR | Moderate risk | Unclear |

| Ye, 2019 [68] | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Zhang 2008, [69] | HR | UR | LR | UR | UR | LR | HR | HR | LR | LR | LR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Shi, 2008, [70] | LR | LR | HR | LR | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate risk | Unclear |

| Guzman 2019, [71] | LR | LR | LR | LR | HR | LR | UR | HR | LR | LR | HR | UR | Moderate Risk | No |

| Braeckman 1997, [72] | HR | HR | HR | UC | UC | HR | UC | HR | LR | LR | HR | HR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Allott 2019, [73] | LR | HR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | UR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Mills 2007, [74] | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Low Risk | No |

| Zhang 2015, [75] | UR | LR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | LR | Moderate Risk | Yes |

| Safwat 2018, [76] | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | HR | LR | LR | UR | UR | Moderate Risk | Yes |

| Ghadian 2017, [77] | UR | HR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Di Silverio 2005, [78] | LR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | HR | UR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Goodarzt 2011, [79] | HR | HR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Jhang 2013, [80] | HR | UR | UR | UR | UR | HR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | High Risk | Unclear |

| Page 2011, [81] | LR | LR | UR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | LR | UR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Kacker 2014, [82] | LR | UR | LR | UR | UR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | UR | UR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Chung 2011, [83] | LR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | LR | HR | LR | LR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

| Griwan 2014, [99] | LR | HR | UR | LR | UR | UR | UR | LR | UR | UR | LR | LR | Moderate Risk | Unclear |

Data Synthesis: α1-blockers

Six trials randomized men (n = 4525) to α-blocker versus placebo (Table 1) [18–23]. The MTOPS randomized men to receive doxazosin, finasteride, combination or placebo and reported +24% (+10.1 ml) change in TPV of patients receiving doxazosin at 4 years, similar to placebo (+24% or +8.8 ml) [19]. The Veteran Affairs Cooperative Study (VA-COOP Study) reported similar changes in terazosin and placebo arms at 12 months (+2.0% or +0.5 ml vs +2.3% or +0.5 ml) [18]. The ALFUS trial reported non-significant changes from baseline at 3 months in men who received alfuzosin or placebo in both TPV (-2% or 0.25 ml vs +3% or +0.46 ml) and TZV (-2% vs -5% or -0.8 ml vs -0.39 ml) [22]. Five RCTs reported on post treatment PSA changes, which were similar to placebo [18–21, 23]. There was no information on prostate perfusion parameters.

Ten RCTs randomized men (n = 5479) to an α-blocker versus an active comparator with a follow-up to 24 weeks [24–33]. All studies reported non-significant TPV changes from baseline (-3.4% to +9.5% or -1.4 ml to +6.32 ml). CombAT randomized men to receive tamsulosin, dutasteride or combination and followed them up for 4.5 years [32]. Men in the tamsulosin arm increased TPV by +4.6% (+2.57 ml) and TZV by +18.2% (+5.5 ml). A single trial compared tamsulosin to silodosin and reported a reduction of TPV after 6 months, which was greater in the silodosin arm (-2.8% vs -8.6% or -1.0 ml vs -3.6 ml, p = 0.594) [27]. TPV changes after 3-months of Naftopidil treatment were negligible and comparable to tamsulosin [99]. A trial with high RoB reported +9.5% (+6.32 ml) increase in TPV after 6 months tamsulosin monotherapy, which was neither significantly different from baseline (p = 0.17) nor from the comparator [30]. The Alfin study reported no significant change in TPV (-1% or -0.2 ml) or PSA value (+3.3% or +0.1 ng/dl) after 6 months of alfuzosin treatment [33]. PSA was reported unchanged in four tamsulosin studies (-5.0% to +7.4%) [24, 28, 29, 31]. Tamsulosin monotherapy enhanced prostate perfusion (+146%) as opposed to tamsulosin and solifenacin combination treatment (-41%) in a male overactive bladder (OAB) cohort [34].

5-ARIs

Sixteen trials randomized men (n = 21109) to 5-ARI versus placebo (Table 1) [18, 19, 35–48]. Twelve finasteride trials reported significant changes in TPV as compared to baseline and to placebo [18, 19, 35–44]. The quantitative synthesis revealed a large effect size in favor of finasteride [SMD]: -1.15 (95%CI: -1.26 to -1.04, p <0.001) (Figure 2). The effect on TPV varies between studies with different follow-ups. Trials with 3-6 months’ follow-up report changes between -4.8% and -26.1%, while trials with follow-up of 12 months or longer report higher TPV changes (-15.3% to -22.4% or -8.1 ml to -10.53 ml). The finasteride study group randomized men to finasteride 1 mg versus finasteride 5 mg versus placebo, and reported similar TPV changes at 12 months (-23.6% vs -22.4% vs -5%), but the later was superior in improvement of clinical parameters such as maximum flow rate and relevant questionnaires scores [40].

Four dutasteride trials reported significant changes in TPV both from baseline or as compared to placebo [45-48]. The quantitative analysis revealed a large size effect [SMD]: -0.66 (95%CI: -0.83 to -0.49, p <0.001) (Figure 4). The effect on TPV appears homogenous among studies with different follow-up and ranges between -17.5% and- 27.0% (-7.2 ml to -13.6 ml). Dutasteride also significantly reduces TZV (-20.1% or -7.1 ml, p <0.001), an effect which is evident from the first month of treatment.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of 5-ARI effect on prostate morphometric parameters in placebo-controlled trials. A) Forrest plot of the effect of finasteride versus placebo on total prostate volume (TPV). B) Forrest plot of the effect of dutasteride versus placebo on total prostate volume (TPV). C) Forrest plot of the effect of finasteride versus placebo on prostate-specific antigen (PSA). D) Forrest plot of the effect of finasteride on total prostate volume in placebo-controlled trials with 6 months follow-up.

CI – confidence interval; SD – standard deviation

Nine finasteride RCTs report significant changes in PSA as compared to baseline or to placebo [18, 19, 35, 36, 39, 40, 42, 43, 44]. The quantitative analysis revealed a moderate size effect in favor of finasteride ([SMD]:-0.63, 95%CI:-0.76 to 0.51), p <0.001) (Figure 4). Trials with 12 months follow-up or more report a PSA change of -46.0% to -52%. Three dutasteride RCTs, report significant reduction in PSA (-42.2% to -52.4%), compared to both baseline (p <0.05) and placebo (p <0.05) [45, 46, 47].

Five RCTs randomized men (n = 3615) to finasteride versus an active comparator. All studies report significant TPV changes from baseline (-10.5% to -24.3% or -4.3 ml to -7.5 ml) and significant difference from the active comparator [30, 33, 49, 50, 51]. The dutasteride arm of CombAT reported -28.0% (-15.3 ml) and -26.5% (-8.03 ml) reduction of TPV and TZV, respectively [32]. The EPICS study randomized men to finasteride or dutasteride for 12 months and found significant change from baseline in both arms (-26.7% vs -26.3% or -13.99 ml vs -14.2 ml) without intergroup difference (p = 0.65) [49]. Another trial reported similar changes after 12 months’ treatment with finasteride or dutasteride (-24.5% vs -26.1% or -9.76 ml vs -10.2 ml) but a significant increase of TPV (+11.2% vs 8.66%) 12 months after discontinuation of 5-ARI therapy [52]. PSA changes were different from baseline (-47.7% vs 49.5%, p <0.01), without difference between groups (p = 0.776). The ALFIN study reported a -50% change (-1.7 ±1.9, p <0.05) in PSA from baseline [33]. There was no information on prostate perfusion parameters.

PDE-5 inhibitors

Yokoyama et al., randomized 612 men to receive tadalafil 2.5 mg, tadalafil 5 mg, tamsulosin 0.2 mg or placebo for 3 months (Table 3) [20]. Authors reported non-significant changes in PSA from baseline in either tadalafil group (-7% vs -2%) that were similar to placebo. Pinggera et al., reported that tadalafil does not affect prostate perfusion as evaluated by 3 basic perfusion parameters [53]. There was no information on TPV and TZV changes.

Table 3.

Baseline and outcome measures of included studies

| Study Description | Results | Outcome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active medication | Placebo | ||||||||||

| Author (yr), [ref] (RoB overall rating) | Comparison | Main inclusion criteria | Study duration | Randomized patients (N) in each arm | Baseline mean (mls), ±SD | Total No. of patients (N) Analysed | Mean change from baseline, ±SD) (p value) (% mean change ±SD, p value) | Baseline mean (mls), ±SD | Total No. of patients (N) Analysed | Mean change from baseline, ±SD) (p value) (% mean change ±SD, p value) | |

| Beiraghdar 2017, [63] Moderate Risk |

Viola odorata, Echiumamoneum and Physalis Alkekengi vs Placebo | Men 40–75 yo, with LUTS due to BPH, Prostate volume >30 ml, IPSS ≥13 | 2 weeks | 57 vs 29 | TPV: 37.25 ±2.2 | 57 | TPV: not given absolute values (-16.92% ±0.89) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 42.67 ±4.3 | 29 | TPV: not given absolute values (+2.91% ±0.81) NS |

Significant reduction in TPV in phytotherapy vs placebo (p <0.001) |

| Berges 1995, [64] Moderate Risk |

β-sitosterol vs Placebo | Men <75 yo, Qmax <15 ml/s and residual volume 20–150 ml | 6 months | 83 vs 80 | TPV: 44.6 ±19.4 | 83 | TPV: -3.1 ±8.8 (-6.95%) NS |

TPV: 48.0 ±27.9 | 80 | TPV: -0.3 ±9.0 (-0.6%) NS |

Non-significant change in TPV compared to baseline or between groups |

| Safarinejad 2005, [65] High Risk |

Urtica Diopa vs Placebo | Men 55–72 yo, with LUTS due to BPH | 6 months | 305 vs 315 | TPV: 40.1 ±6.8 PSA: 2.4 ±1.4 |

287 | TPV: -3.8 ±5.94 (-9.47%) (p <0.01) PSA: -0.2 ±1.31 (-8.34%) NS |

TPV: 40.8 ±6.2 PSA: 1.8 ±1.4 |

271 | TPV:-0.2 ±5.73 (-0.5%) NS PSA: +0.01 ±1.0 (+1.0%) NS |

Significant reduction in TPV in phytotherapy group from baseline (p <0.01) |

| Bent 2006, [66] Low Risk |

Saw Palmetto vs Placebo | Men >49 yo, with moderate to severe LUTS due to BPH, Qmax 8–15 ml/s, PVR <250 | 52 weeks | 112 vs 113 | TPV: 34.7 ±13.9 TZV: 13.2 ±10.4 PSA: 1.8 ±1.4 |

112 | TPV: +3.76 ±10.4 (+10.8%) (NP) TZV: +3.26 ±10.9 (+25.3%) (NP) PSA: -0.005 ±0.74 (-0.3%) (NP) |

TPV: 33.9 ±15.2 TZV: 12.5 ±11.0 PSA: 1.6 ±1.4 |

113 | TPV: +4.98 ±10.2 (+14.7%) (NP) TZV: +2.01 ±10.7 (+15.1%) (NP) PSA: +0.15 ±0.74 (+8.8%) (NP) |

Non-significant changes in prostate size and PSA between groups |

| Marks 2000, [67] Moderate Risk |

Saw Palmetto vs Placebo | Men 45–80 yo, with IPSS >9, PSA <15 ng/dl, Prostate volume >30 ml | 24 weeks | 21 vs 23 | TPV: 58.5 ±6.5 TZV: 32.2 ±6.3 PSA: 2.67 ±0.4 |

21 | TPV: +3.42 ±6.9 (+5.8%) (NS) TZV: -0.92 ±6.3 (-2.9%) (NS) PSA: +0.13 ±0.46 (+4.9%) (NS) |

TPV: 55.5 ±5.6 TZV: 27.4 ±4.6 PSA: 4.06 ±0.7 |

23 | TPV: +0.22 ±5.7 (+0.5%) (NS) TZV: +0.42 ±4.7 (+1.5%) (NS) PSA: -0.17 ±0.79 (-4.2%) (NS) |

Non-significant changes in prostate size and PSA between groups. Saw palmetto - epithelial contraction in the transition zone (p <0.01) |

| Ye 2019, [68] Low Risk |

Saw Palmetto vs Placebo | Men 50–70 yo, with LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≤19, Stable sexual life, 2 week BPH medication withdrawal | 24 weeks | 159 vs 166 | TPV: 34.3 ±18.3 PSA: 2.41 ±4.6 |

150 | TPV: +0.77 ±9.4 (+2.25%) (NS) PSA: -0.24 ±1.36 (-9.96%) (NS) |

TPV: 34.4 ±22.1 PSA: 1.99 ±2.5 |

154 | TPV:+0.31 ±11.4 (+0.9%) (NS) PSA: -0.01 ±2.3 (-1.0%) (NS) |

Non significant change in TPV (p = 0.74) and in PSA (p = 0.289) compared to baseline. No difference between groups |

| Zhang 2008, [69] High Risk |

Flaxseed LIgnan Extractvs Placebo | Men 55–80 yo, IPSS ≥7, Prostate volume ≥30 ml, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, normal kidney function | 4 months | 25 vs 24 | TPV: 46.7 ±3.7 | 25 | TPV: -5.39 ±4.5 (-11.5%) (p<0.01) |

TPV: 41.01 ±2.4 | 24 | TPV: -6.6 ±6.1 (-16.1%) (p<0.01) |

Significant reduction in TPV from baseline). Non-significant difference between groups |

| Shi 2008, [70] Moderate Risk |

Saw Palmetto vs Placebo | Men 49–75 yo, treatment naïve, LUTS due to BOH, clinical BPH on DRE, PSA ≤4 ng/dl | 12 weeks | 46 vs 48 | TPV: 47.72 ±8.1 PSA: 1.84 ±0.88 |

46 | TPV: -2.08 ±6.12 (-4.4%) NS PSA: -0.05 ±0.78 (-2.7%) (NS) |

TPV: 48.38 ±7.4 PSA: 1.9 5 ±1.03 |

46 | TPV: -2.48 ±6.4 (-5.1%) NS PSA: -0.26 ±0.65 (-13.8%) (NS) |

Non significant difference between groups in TPV (p = 0.826) and PSA (p = 0.305). |

| Andersen 1995, [35] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Men age ≤80yo, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, LUTS (2 moderate symptoms), enlarged prostate on DRE, PSA ≤10 ng/dl, PVR ≤150 mls | 24 months | 354 vs 353 | TPV: 40.6 mls PSA: NR |

197 | TPV: -19.2 ±23.27 (-17.9%) (p <0.01) PSA: -52% (p <0.001) |

TPV: 41.7 mls PSA: NR |

197 | TPV: +11.5 ±23.8 (+11.5%) (p <0.05) PSA: +6% (NS) |

Significant difference between groups in TPV (p <0.01) and PSA (p <0.001) |

| Nickel 1996, [36] PROSPECT Study Low Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Men age ≤80 yo, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, LUTS (2 moderate symptoms), enlarged prostate on DRE, PSA ≤10 ng/dl, PV R ≤150 mls | 24 months | 310 vs 303 | TPV: 44.1 ±23.5 PSA: not reported |

246 | TPV: -8.63 ±9.04 (-21.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: -50% (p <0.01) |

TPV: 45.8 ±22.4 PSA: not reported |

226 | TPV: +3.84 ±11.4 (+8.4%) NS PSA: +13.3% (p <0.01) |

Siignificant difference between groups (P <0.01) in both TPV and PSA |

| McConnel 1998, [37] Low Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men, Qmax <15 ml/s, BPH on DRE, PSA <10 ng/dl | 48 months | 157 vs 155 *TVP measurement only in 10% of study population |

TPV: 54.1 ±26 | 130 | TPV: -9.72 ± n/a (-18.0%) (p <0.01) |

TPV: 55 ±26 | 119 | TPV: +5.5 ±n/a (+14.0%) (p <0.05) |

Difference between groups, 32% P <0.001) |

| Marberger 1998, [38] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Men 50–75 yo, BPH, Qmax 5-15 ml/s, VV >150 ml, LUTS (2 at least symptoms), enlarged prostate on DRE, PSA <10 ng/dl, PVR <150 ml | 24 months | 1450 vs 1452 | TPV: 38.7 ±20.1 | 890 | TPV: -8.1 ±25.6 (-15.3%) (p <0.01) |

TPV: 39.2 ±20.2 | 906 | TPV: +1.5 ±19.9 (+8.9%) (p <0.05) |

Significant reduction in TPV (p <0.01) from 12th months. Statistical significant difference between groups (p <0.001) |

| Kirby 1992, [39] High Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Finasteride 10 mg vs Placebo | Men 48–87 yo, BPH, Urodynamically proven obstruction | 3 months | 29 vs 16 vs 21 | TPV: 49.7 ±NR PSA: 4.1 ±NR |

25 | TPV: -2.5 ±27.0 (-4.8%) NS PSA: -1.1 ± n/a (-20.5%) (p <0.05) At 12 months TPV -14.1% and PSA -28% |

TPV: 54.3 ±NR PSA: 5.0 ±NR |

10 | TPV: -1.8 ± 14.4 (-4.22%) NS PSA: -1.0 ±n/a (-6.2%) NS |

Statistical significant reduction of PSA (p <0.05) in finasteride arm. No dose related effect at 3 months 10 mg: TPV -3.7&, PSA NS |

| Finasteride group 1993, [40] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 1 mg vs Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Men 40–80 yo, Qmax <15 ml/s, TPV >30 ml, clinical BPO, No infection or neurogenic bladder |

12 months | 249 vs 246 vs 255 | TPV: 47.0 ±20.8 PSA: 5.8 ±6.7 |

246 | TPV: -10.53 ±n/a (-22.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: -2.67 ±n/a (-46.0%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 46.3 ±23.4 PSA: 5.7 ±7.2 |

TPV: -2.31 ±n/a (-5.0%) NS PSA: -0.11 ±n/a (-2.0%) NS |

Significant reduction of TPV and PSA from 3rd month. No change in placebo arm. The effect of 1 mg were similar of 5 mg (TPV -23.6%, PSA -43%). Statistical significant difference between groups (p <0.001). There was great difference on clinical improvement with 5 mg |

|

| Tammela 1995, [41] High Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Ambulatory men, with LUTS due to BPO. Qmax <15 ml/s, Negative history for Prostate cancer | 6 months | 18 vs 18 | TPV: 56.0 ±25.0 | 18 | TPV: -15.0 ±22.6 (-26.1%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 47.0 ±17.0 | 18 | TPV: -2.0 ±18.0 (-4.3%) NS |

Statistical significant reduction of TPV (p <0.05) as compared to placebo |

| Pannek 1998, [42] High Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve Men 45–78 yo, IPSS ≥9, PSA <10 ng/dl | 6 months | 24 vs 10 | TPV: 36.7 ±17.0 PSA: 3.02 ±2.9 |

24 | TPV: -7.1 ±15.2 (-21.4%) (p <0.01) PSA: -1.53 ±2.52 (-50.7%) (p = 0.005) |

TPV: 37.2 ±11.4 PSA: 3.74 ±3.3 |

10 | TPV: -1.0 ±11.9 (-2.7%) NS PSA: -1.03 ±2.96 (-27.3%) (p <0.05) |

Statistical significant reduction of PSA from baseline but no difference between groups |

| Marks 1997, [43] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve Men 45–78 yo, IPSS ≥9, PSA <10 ng/dl | 6 months | 26 vs 15 | TPV: 37.0 ±17.0 PSA: 2.7 ±2.5 |

26 | TPV: -8.0 ±15.1 (-21.0%) (p <0.01) PSA: -1.3 ±2.16 (-49.0%) (p <0.01) | TPV: 37.0 ±10.0 PSA: 3.3 ±3.1 |

13 | TPV: -0.4 ±10.0 (-3.0%) NS PSA: -0.2 ±2.0 (-1.0%) NS |

Statistical significant reduction of TPV and PSA in finasteride arm (p <0.01) as compared to placebo. 6% reduction of transitional zone epithelium (p <0.01) |

| Lepor 1996, [18] Prostate Hyperplasia Study Group Low Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥8, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, PVR <300 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 306 vs 310 vs 309 vs 305 | TPV: 36.2 ± 1.0 PSA: 2.2 ±1.8 |

252 | TPV: -6.1 ±NR (-18.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.9 ±NR (-29.0%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 38.4 ±1.3 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

264 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (+2.3%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±NR (-4.0%) NS |

Statistical significant reduction of TPV and PSA in finasteride arm (p <0.001) from baseline. Statistical significant difference between groups (p <0.001) |

| Gormley 1992, [44] Finasteride study group Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men 40–83 yo, enlarged prostate on DRE, Qmax <15 ml/s, PSA <40 ng/dl, No other cause of LUTS | 12 months | 297 vs 300 | TPV: 58.6 ±30.5 PSA: 3.6 ±4.2 |

257 | TPV: -11.1 ±27.6 (-19.0%) (p <0.01) PSA: n/a (-50%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 61.0 ±36.5 PSA: 4.1 ±4.8 |

263 | TPV: -1.2 ±38.0 (-3.0%) NS PSA: non-significant changes |

Statistical significant reduction of TPV and PSA in finasteride as compared to placebo (p <0.001). Drop of PSA from month 3 and then stable |

| McConnell 2003, [19] MTOPS research group Low Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men 50 yo and older, AUASI 8–35, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, No other cause of LUTS | 4.5 years | 756 vs 768 vs 786 vs 737 | TPV: 36.9 ±20.6 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

551 | TPV: -12.0 ±26.6 (-19.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: NR (-50%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 35.2 ±18.8 PSA: 2.3 ±2.0 |

519 | TPV: +8.8 ±36.0 (+24.0%) (p <0.001) PSA: NR (+15%) (p <0.001) |

4 years results. Statistical significant reduction of TPV and PSA in finasteride |

| Roehrborn 2002, [45] pooled analyses 3 different trials Low Risk |

Dutasteride 0.5 mg vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥12, Qmax <15 ml/s, PSA 1.5–10 ng/dl, Prostate volume ≥30 mls | 24 months | 2167 vs 2158 | TPV: 54.9 ±23.9 TZV: 26.8 ±17.1 PSA: 4.0 ±2.1 |

1510 | TPV: -14.6 ±13.5 (-25.7%) (p <0.001) TZV: -7.1 ±9.7 (-20.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: -2.2 ±2.0 (-52.4%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 54.0 ±21.9 TZV: 26.8 ±17.4 PSA: 4.0 ±2.1 |

1441 | TPV: +0.8 ±14.3 (+2.0%) p = 0.04 TZV: +1.8 ±11.2 (+5.9%) (p <0.01) PSA: +0.5 ±2.1 (+15.8%) (p <0.001) |

Significant difference between groups (p <0.001) TPV and TZV decreased significantly from month 1 and continuing through 24 months |

| Na 2012, [46] Moderate Risk |

Dutasteride 0.5 mg vs Placebo | Men ≥50 yo, clinical BPH, TPV ≥30 ml, AUASI ≥12, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, VV ≥125 ml | 6 months | 126 vs 127 | TPV: 48.2 ±27.7 PSA: 3.33 ±1.9 |

113 | TPV: -7.2 ±11.1 (-17.1%) (p <0.05) PSA: -1.44 ±NR (-43.3%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 42.3 ±16.5 PSA: 3.14 ±1.9 |

116 | TPV: -1.6 ±12.8 (-3.7%) PSA: -0.12 ±NR (-4.0%) |

Significant improvements in PSA and TPV in dutasteride group |

| Tsukamoto 2009, [47] Moderate Risk |

Dutasteride 0.5 mg vs Placebo | Men ≥50 yo, clinical BPH, TPV ≥30 ml, IPSS ≥8 m qmax <15 ml/s, VV ≥150 mls, PSA <4 ng/dl | 6 months | 193 vs 185 | TPV: 50.2 ±19.8 PSA: 3.5 ±n/a |

184 | TPV: -13.6 ±12.8 (-27.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: -42.2% (p <0.05) |

TPV: 49.4 ±17.2 PSA: 3.5 ±n/a |

181 | TPV: -4.94 ±8.7 (-10.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: +12.0 % |

Significant improvements in PSA and TPV in dutasteride group |

| Andriole 2010, [48] REDUCE Study group Moderate Risk |

Dutasteride 0.5 mg vs Placebo | Men 50–75 yo, PSA 2.5-10 ng/dl, and had TRUSg prostate biopsy 6 months before enrollemnt | 48 months | 4105 vs 4126 | TPV: 45.7 ±18.2 | 3299 | TPV: -6.7 ±18.3 (-17.5%) (p = NR) |

TPV: 45.7 ±18.8 | 3407 | TPV: +3.9 ±18.5 (+19.7%) (p = NR) |

Significant change between groups in TPV (P <0.001) |

| Yokoyama 2012, [20] Low Risk |

Tadalafil 5 mg vs Placebo | Asian men ≥45 yo, BPH-LUTS, Total IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–12 ml/s, volume >20 ml, PS | 3 months | 155 vs 154 | PSA: 1.71 ±1.14 | 153 | PSA: +0.13 ±0.59 (p = 0.083) (+7%) | PSA: 1.74 ±1.35 | 152 | PSA: -0.03 ±0.55 (-1%) | Non-significant changefrom baseline. No difference between groups |

| Roerhborn 2006 [21] ALTESS Study group Low Risk |

Alfuzosin vs Placebo | Men ≥55 yo, history of LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 5–12 ml/s, VV ≥150 ml, PVR <350 mls, Prostate volume ≥30 mls, PSA 1.4–10 ng/dl | 24 months | 759 vs 763 | PSA: 3.4 ±2.0 | 754 | PSA: -0.1 ±N/a (-0.6%) NS | PSA: 3.6 ±2.1 | 761 | PSA: +0.2 ±N/a (-3.6%) NS | No significant changes from baseline or between group (p >0.05) |

| Roerhborn 2006 [22] ALFUS Trial Moderate Risk |

Alfuzosin vs Placebo | Men ≥55 yo, history of LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 5–12 ml/s, VV ≥150 ml, PVR <350 mls, Prostate volume ≥30 mls, PSA 1.4–10 ng/dl | 3 months | 353 vs 175 | TPV: 39.3 ±17.9 TZV: 18.0 ±11.7 |

307 | TPV: -0.25 ±8.3 (-2%) NS TZV: -0.8 ±6.8 (-2%) NS |

TPV: 36.0 ±18.3 TZV: 16.3 ±12.7 |

157 | TPV: +0.46 ±8.5 (+3%) NS TZV: -0.39 ±8.2 (-5%) NS |

None of thedifferences between placebo and alfuzosin was statistically significant |

| McConnell 2003, [19] MTOPS research group Low Risk |

Doxazosin vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men 50 yo and older, AUASI 8–35, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, No other cause of LUTS | 4.5 years | 756 vs 768 vs 786 vs 737 | TPV: 36.9 ±21.6 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

582 | TPV: +10.1 ±36 (+24.0%) (p <0.001) PSA: NR (+13%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 35.2 ±18.8 PSA: 2.3 ±2.0 |

519 | TPV: +8.8 ±36.0 (+24.0%) (p <0.01) PSA: NR (+15%) (p <0.00) |

4 years results. Non-significant differences between doxazosin and placebo groups |

| Turkeri 2001 [23] High Risk |

Doxazosin 4 mg vs Placebo | Men with LUTS due to BPH | 4 weeks | 15 vs 14 | TPV: 53.7 ±22.8 PSA: 3.6 ±0.6 |

15 | TPV: -3.3 ±n/a (-6.2%) (p = NR) PSA: -0.47 ±N/a (-13.9%) (p = NR) |

TPV: 56.7 ±17.6 PSA: 3.5 ±0.7 |

14 | TPV: -5.7 ±n/a (-10.4%) (p = NR) PSA: +0.4 ±N/a (+10%) (p = NR) |

Non-significant differences between groups PSA, but small sample size |

| Lepor 1996, [18] Prostate Hyperplasia Study Group Low Risk |

Terazosin vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥8, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, PVR <300 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 306 vs 310 vs 309 vs 305 | TPV: 37.5 ±1.1 PSA: 2.2 ±1.9 |

275 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (+2.0%) NS PSA: -0.4 ±NR (-20.0%) NS |

TPV: 38.4 ±1.3 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

264 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (+2.3%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±NR (-4.0%) NS |

No statistical significant difference between groups in TPV and PSA |

| Yokoyama 2012, [20] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs Placebo | Asian men ≥45 yo, >6 months history of BPH-LUTS, Total IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–12 ml/s, Prostate volume >20 ml, PSA <4 or else negative biopsy | 3 months | 152 vs 154 | PSA: 1.75 ±1.60 | 150 | PSA: -0.06 ±0.61 (-4%) NS | PSA: 1.74 ±1.35 | 152 | PSA: -0.03 ±0.55 (-1%) NS | Non significant changes between groups |

| Lepor 1996, [18] Prostate Hyperplasia Study Group Low Risk |

Terazosin plus Finasteride combination vs Placebo | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥8, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, PVR <300 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 309 vs 305 | TPV: 37.2 ±1.1 PSA: 2.3 ±2.0 |

277 | TPV: -7.0 ±NR (-18.8%) (p <0.001) PSA: +0.9 ±NR (+39.1%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 38.4 ±1.3 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

264 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (+2.3%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±NR (-4.0%) NS |

Statistical significant difference between groups in TPV and PSA. Max TPV and PSA reduction at 26th week, as in finasteride group |

| McConnell 2003, [19] MTOPS research group Low Risk |

Doxazosin plus finasteride vs Placebo |

Treatment naïve men 50 yo and older, AUASI 8–35, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, No other cause of LUTS | 4.5 years | 786 vs 737 | TPV: 36.4 ±19.2 PSA: 2.3 ±1.9 |

574 | TPV: -12.1 ±30 (-19.0%) (p <0.001) PSA: NR (-50%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 35.2 ±18.8 PSA: 2.3 ±2.0 |

519 | TPV: +8.8 ±36.0 (+24.0%) (p <0.01) PSA: NR (+15%) (p <0.01) |

4 years results. Significant differences between combination and placebo groups in TPV and PSA (p <0.001) |

| Joo 2012, [57] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and Dutasteride |

Treatment naïve men ≥40 yo, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, VV ≥150 ml, PVR <200 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 108 vs 108 | TPV: 36.63 ±13.2 TZV: 14.94 ±7.16 PSA: 1.7 ±1.23 |

95 | TPV: +0.38 ±2.1 (+1.0%) NS TZV: +0.24±0.66 (+1.6%) NS PSA: -0.06 ±0.22 (-3.5%) NS |

TPV: 37.26 ±13.2 TZV: 15.36 ±7.56 PSA: 1.77 ±1.4 |

98 | TPV: -10.04 ±6.14 (-26.9%) (p <0.05) TZV: -3.03 ±2.32 (-19.7%) (p <0.05) PSA: -0.73 ±0.68 (-41.2%) (p <0.05) |

Statistical significant change from baseline (<0.05) in combination group. Integroup comparison p <0.05 inTPV, TZV and PSA |

| Choi 2016, [58] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and Dutasteride |

Treatment naïve men ≥40 yo, Prostate volume >30 ml, IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, VV ≥150 ml, PVR <200 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 59 vs 59 | TPV: 40.34 ±1.4 TZV: 16.0 ±1.26 PSA: 1.35 ±0.12 |

55 | TPV: 0.0 ±NR (0%) NS TZV: 0.0 ±NR (0%) NS PSA: +0.17 ±NR (+12.6%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 41.05 ±2.7 TZV: 16.95 ±2.33 PSA: 1.31 ±0.15 |

46 | TPV: -8.0 ±NR (-19.5%), p <0.001 TZV: -3.0 ±NR (-17.7%), p <0.001 PSA: -0.24 ±NR (-18.3%), p <0.001 |

Statistical significant differences between groups in TPV (p = 0028) and TZV (p <0.001). PSA didn’t differ (p = 0.108) |

| Ryu 2014, [61] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.2 mg and Serenoa repens 320 mg |

Treatment naïve men 50–70 yo, IPSS >10, Qmax 5–15, VV >150 ml, Prostate volume ≥25 ml, PSA <4 ng/dl | 12 months | 60 vs 60 | TPV: 30.2 ±0.67 PSA: 1.1 ±0.16 |

53 | TPV: +0.1 ±0.15 (+1.0%) NS PSA: +0.2 ±0.12 (+18.0%) (p = NR) |

TPV: 30.1 ±0.93 PSA: 1.2 ±0.11 |

50 | TPV: -0.7 ±0.27 (-2.0%) NS PSA: +0.2 ±0.12 (+8.0%) (p = NR) |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume (p = 0.096) or PSA (p = 0.521) |

| Debruyne 2002, [24] PERMAL Study Group Low Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Serenoa repens 320 mg |

Treatment naïve men 50–85 yo, IPSS >10, Qmax 5–15, VV >150 ml, Prostate volume ≥25 ml, PSA< 4 ng/dl or negative biopsy if PSA ≥4 ng/dl | 12 months | 354 vs 350 | TPV: 48.0 ±19.0 PSA: 2.7 ±2.2 |

TPV N: 270 PSA N: 268 |

TPV: +0.2 ±12.8 (+1.0%) NS (p = 0.75) PSA: +0.2 ±1.6 (+7.4%) NS (p = 0.09) |

TPV: 48.2 ±18.0 PSA: 2.5 ±1.9 |

TPV N: 269 PSA N: 266 |

TPV: -0.9 ±13.4 (-2.0%) NS (p = 0.75) PSA: +0.2 ±1.4 (+10.0%) NS (p = 0.09) |

No significant changes between groups in TPV (p = 0.27) or PSA (p = 0.5) |

| Sengupta 2011, [25] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs phytotherapy (MurrayaKoenigii and tribulusterrestris) |

Treatment naïve men >50 yo, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS, IPSS >7, enlarged prostate | 12 weeks | 23 vs 23 | TPV: 41.3 ±26.8 | 21 | TPV: -1.4 ±23.1 (-3.4%) NS (p = 0.099) |

TPV: 33.5 ±24.1 | 23 | TPV: -1.9 ±13.9 (-5.6%) (p = 0.04 from baseline) |

Significant difference TPV between groups (p = 0.037) |

| Latil 2015, [26] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs hexamic extract Serenoa repens 320 mg |

Treatment naïve men 45–85 yo, BPH related LUTS >12 months, IPSS ≥12, prostate volume 30 ml, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, VV 150-500 ml, PSA ≤4 or negative biopsy | 12 weeks | 101 vs 102 | TPV: 46. 3 ±13.8 | 86 | TPV: -0.53 ±10.5 (-1.0%) NS |

TPV: 48.8 ±20.8 | 83 | TPV: -0.99 ±10.9 (-2.0%) NS |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume NS |

| Pande 2014, [27] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Silodosin 8 mg |

Treatment naïve men >50 yo, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS >7, low PSA | 12 weeks | 29 vs 32 | TPV: 35.6 ±9.6 | 27 | TPV: -1.0 ±13.5 (-2.8%) NS (p = 0.677) |

TPV: 42.0 ±20 | 26 | TPV: -3.6 ±19.6 (-8.6%) NS (p = 0.594) |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume (p = 0.996) |

| Sakalis 2018, [34] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.4 mg and Solifenacin | Treatment naïve men >50 yo, storage LUTS due to BPH, IPSS >7, Q3 IPSS ≥, Qmax ≥10, PSA <4 or negative biopsy | 6 months | 34 vs 35 | TPV: 48.9 ±13.6 TZV: 24.4 ±10.2 PSA: 1.36 ±1.0 |

31 | TPV: +3.88 ±14.6 (+9.2%) (p <0.001) TZV: +3.74 ±10.7 (+17.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: +0.26 ±1.0 (+19.1%) (p <0.051) |

TPV: 52.6 ±13.0 TZV: 28.4 ±21.4 PSA: 1.9 ±1.6 |

32 | TPV: -5.49 ±16.1 (-9.5%) (p <0.001) TZV: -2.48 ±21.1 (-12.5%) (p <0.001) PSA: +0.2 ±1.5 (+10.5%) (p <0.549) |

Significant changes in TPV and TZV in both groups from baselines and in intergroup comparison (p <0.001). Non-significant PSA changes |

| Safwat 2018, [76] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Tamsulosin plus Cholecalciferol 600IU/day | Men with AUA-SI score >7 | 24 months | 193 vs 196 | TPV: 55.4 ±13.1 PSA: 0.26 ±0.09 |

TPV: +3.3 ±3.5 (+5.9%) NS PSA: +0.01 ±0.0009 (+3.8%) NS |

TPV: 60.2 ±10.8 PSA: 0.19 ±0.05 |

TPV: +4.9 ±2.2 (+8.1%) NS PSA: +0.032 ±0.0022 (+16.8%) NS |

Non significant changes in TPV (p = 0.098) between groups. Significant difference between groups in PSA (p = 0.044) |

||

| Griwan 2014, [99] Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Naftopidil 75 mg | Men >45 yo, symptomatic BPH, Frequency >8, Nocturia >2, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, IPSS >13 | 3 months | 30 vs 30 | TPV: 57.73 ±7.33 | 30 | TPV: -0.04 ±7.37 (-1.0%) NS (p = 0.15) |

TPV: 56.81 ±6.45 | 30 | TPV: +0.01 ±6.52 (-1.0%) NS (p = 0.18) |

No significant changes between groups TPV or from baseline |

| Nickel 2011, [49] EPICS Study Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Dutasteride 0.5 mg | Men ≥50 yo, with clinical BPH, AUASI score ≥12, Vol Prostate ≥30 ml, Qmax <15 mls/s, VV ≥125 ml, PVR <250 ml | 12 months | 817 vs 813 | TPV: 52.4 ±19.4 PSA: 4.3 ±2.2 |

735 | TPV: -13.99 ±n/a (-26.7%) (p <0.05) PSA: -2.05 ±n/a (+47.7%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 54.2 ±21.9 PSA: 4.3 ±2.3 |

719 | TPV: -14.2 ±n/a (-26.3%) (p <0.05) PSA: -2.12 ±n/a (+49.5%) (p <0.05) |

Non-significant changes between groups (p = 0.776) Greater reductions in men with prostates >40 grs |

| Jeong 2009, [52] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg plus a-blocker versus Dutasteride 0.5 mg plus a-blocker | Men ≥50 yo, with moderate to severe LUTS (determined by IPSS), without previous 5ARI treatment but on a blocker, with prostate volume ≥25 ml | 12 months Plus 12 months of 5ARI discontinuation |

60 vs 60 | TPV: 39.78 ±9.3 PSA: 1.83 ±1.19 |

37 | TPV: -9.76 ±8.24 (-24.51%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.89 ±0.49 (-48.9%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 39.22 ±12.3 PSA: 1.85 ±1.31 |

40 | TPV: -10.25 ±9.98 (-26.11%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.94 ±0.79 (-50.9%) (p <0.001) |

Non significant difference between arms inTPV change (p = 0.568) and PSA changes (p = 0.352). Significant increase of TPV (+11.2% and +8.66%) and PSA (+46.2% and +43.1%) at 12 months after 5ARI discontinuation |

| Carraro 1996, [50] Low Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Serenoa repens 320 mg | Clinical BPH, IPSS >6, Qmax 4-5 mls/s, Prostate volume >25 mls, PSA according to predefined prostate volume limits | 6 months | 545 vs 553 | TPV: 44.0 ±20.6 PSA: 3.23 ±3.34 |

484 | TPV: -7.3 ±19.12 (-18.0%) (p <0.001) PSA: -1.23 ±2.9 (-41.0%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 43.0 ±19.6 PSA: 3.26 ±3.41 |

467 | TPV: -1.5 ±20.0 (-7.0%) (p = NR) PSA: -0.04 ±3.7 (-3.0%)(p = NR) |

Both treatments reduced prostate size, but the reduction was significantly greater in finasteride arm (p <0.001) |

| Di Silverio 2005, [78] Moderate Risk |

Finasteride 5 mg vs Finasteride 5 mg and Rofecoxib 25 mg | Men 50–80 yo, IPSS >12, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, VV >150 mls, Prostate volume >40 mls and PSA <10 ng/dl | 6 months | 23 vs 23 | TPV: 51.65 ±9.1 PSA: 2.68 ±1.18 |

23 | TPV: -8.83 ±8.35 (-20.2%) PSA: -0.98 ±1.1 (-36.4%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 49.65 ±9.5 PSA: 2.62 ±1.16 |

23 | TPV: -8.79 ±8.93 (-20.1%) (p = NR) PSA: -0.93 ±1.02 (-35.4%) (p <0.001) |

Significant changes from baseline in both groups (p <0.001) but insignificant changes between groups |

| Guzman 2019, [71] Moderate Risk |

Phytotherapy (Roystonearegia lipid exctract D-004) 320 mg vs Terazosin 5 mg | Men ≥50 yo, Clinical BPH on DRE and, IPSS 7–19, without prior LUT surgery, PSA <5 ng/dl | 6 months | 50 vs 50 | TPV: 31.4 ±23.2 | 50 | TPV: -3.4 ±21.8 (-10.8%) (p <0.01) |

TPV: 29.7 ±19.4 | 50 | TPV: -1.4 ±18.7 (-4.7%) (p <0.01) |

Statistical significant reduction in TPV both groups. Non-significant difference between groups |

| Morgia 2018, [54] SPRITE Study Moderate Risk |

Phytotherapy (Serenoa repens + selenium + lycopene) vs Tadalafil 5 mg | Men 50–80 yo, negative DRE for PCa, PSA <4 ng/dl, IPSS ≥12, Qmax ≤15 ml/s, PVR <100 ml | 6 months | 291 vs 136 Randomization 2:1 |

TPV: 45.0 ±13.1 PSA: 1.8 ±1.0 median value |

276 | TPV: -2.0 ±n/a (-4.5%) (NS) PSA: -0.1 ±1.65 (-5.5%) (NS) |

TPV: 45.0 ±13.0 PSA: 1.9 ±1.1 median value |

128 | TPV: 0.0 ±n/a (0.0%) (NS) PSA: -0.06 ±1.1 (-3.1%)(NS) |

Non-significant changes from baseline or between groups in TPV and PSA |

| Ozturk 2011, [56] High Risk |

Alfuzosin XL vs AlfuzosinXL + Sildenafil 50 mg | Men >45 yo, with moderate to severe LUTS and ED, IPSS ≥12, QoL ≥3 | 3 months | 50 vs 50 | TPV: 47.6 ±30.0 PSA: 1.83 ±1.6 |

50 | TPV: +0.7 ±29.3 (+1.5%) (NS) PSA: -0.04 ±1.5 (-2.2%) (NS) |

TPV: 44.8 ±22.2 PSA: 1.4 ±1.4 |

50 | TPV: -1.6 ±22.6 (-3.6%) (NS) PSA: -0.12 ±1.3 (-8.6%) (NS) |

No significant differences from baseline or between group comparison in TPV and PSA |

| Mohanty 2006, [59] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride vs Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Dutasteride |

Men 40–80 yo, with BPH | 6 months | 53 vs 53 | TPV: 45.4 ±22.5 PSA: 2.3 ±2.2 |

50 | TPV: -8.9 ±20.0 (-19.6%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.2 ±2.1 (-8.7%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 41.1 ±15.1 PSA: 2.0 ±2.2 |

50 | TPV: -6.0 ±14.0 (-14.6%) (p <0.01) PSA: -0.5 ±1.3 (-25.0%) (p <0.001) |

Significant differences from baseline but no difference in intergroup comparison in TPV and PSA |

| Ghadian 2017, [77] High Risk |

Ω3 300 m g plus Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride 5 mg versus Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride 5 mg |

Men 50–70 yo, with LUTS due to BPH, prostate volume >40 ml, IPSS 8–19 | 6 months | 50 vs 50 | TPV: 62.1 ±5.2 | 50 | TPV: -17.1 ±6.0 (-27.5%), (p <0.001) |

TPV: 61.4 ±5.6 | 50 | TPV: -9.62 ±5.7 (-15.6%), (p <0.001) |

Significant differences from baseline but no difference in intergroup comparison in TPV (p <0.001) |

| Page 2011, [81] Moderate Risk |

Testosterone gel 1% 7.5 gr plus placebo versus Testosterone gel 1% 7.5 gr plus dutasteride 0.5 mg | Men ≥50 yo, at least one symptom of androgen deficiency syndrome, Total testosterone <280 nng/dl, Prostate >30 ml, PSA 1.5–10 ng/dl, PVR <200 ml | 6 months | 27 vs 26 | TPV: 54.2 ±38.1 PSA: 2.9 ±2.9 |

27 | TPV: +4.1 ±38.4 (+7.6%) (p <0.05) PSA: +0.3 ±2.9 (10.7%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 44.4 ±19.8 PSA: 2.1 ±1.3 |

26 | TPV: -5.8 ±19.1 (-13.1%) (p <0.05) PSA: -0.7 ±1.3 (33.3%) (p <0.05) |

Significant differences from baseline both TPV and PSA in testosterone plus dutasteride group. Significant difference in intergroup comparison in TPV and PSA (p <0.05) |

| Kacker 2014, [82] Moderate Risk |

Testosterone plus placebo vs testosterone plus dutasteride |

Men 40–85 yo, who already receive testosterone therapy, ±LUTS | 12 months | 11 vs 12 | TPV: 57.4 ±29.3 PSA: 2.58 ±1.2 |

11 | TPV: +3.4 ±14.6 (+5.9%) (NS p = 0.530) PSA: +0.21 ±1.1 (+8.2%) (NS p = 0.458) |

TPV: 45.0 ±25.4 PSA: 1.98 ±0.8 |

11 | TPV: -6.65±11.0 (-14.7%) (p = 0.018) PSA: -0.46 ±0.81 (42.6%)(p = 0.04) |

No significant difference between dutasteride and placebo groups in TPV (p = 0.085) and PSA (p = 0.113) |

| Yamanishi 2017, [60] DIrecT Study Moderate Risk |

Tamsulosin plus dutasteride versus Tamsulosin plus Dutasteride plus imidafenacin | Men 40–89 yo, OAB symptoms (OABS S ≥3), prostate volume ≥30 ml | 24 weeks | 81 vs 82 | TPV: 43.7 ±15.2 PSA: 4.1 ±4.2 |

72 (TPV) 68 (PSA) |

TPV: -9.48 ±n/a (-21.7%) (p <0.05) PSA: -1.88 ±n/a (-47.2%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 44.6 ±18.7 PSA: 3.3 ±2.7 |

69 (TPV) 64 (PSA) |

TPV: -10.07 ±n/a (-22.6%) (p <0.05) PSA: -1.28 ±n/a (-38.8%) (p <0.01) |

Significant changes in TPV and PSA from baseline in both groups. Non significant difference between groups in TPV (p = 0.78), PSA (p = 0.113) |

| Goodarzt 2011, [79] High Risk |

Terazosin 2 mg vs Terazosin 2 mg plus Celecoxib 200 mg | Men ≥50 yo, LUTS due to BPH, AUA Symptom scale 7–25, benign DRE | 12 weeks | 80 vs 80 | TPV: 43.4 ±18.9 PSA: 3.54 ±3.6 |

80 | TPV: -0.4 ±4.8 (-1.0%) (NS p = 0.454) PSA: -0.37 2.9 (-10.5%) (NS p = 0.238) |

TPV: 44.0 ±19.3 PSA: 3.36 ±2.4 |

80 | TPV: -5.7 ±7.0 (-12.9%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.59 ±2.1 (-17.6%) (p = 0.013) |

Significant changes in Celecoxib group from baseline inTPV and PSA. Significant difference between groups in TPV (p < 0.001) only |

| Jhang 2013, [80] High Risk |

Doxazosin 4 mg vs Doxazosin 4 mg plus Celecoxib 200 mg | Men ≥40 yo, LUTS due to BPH, PSA ≥4 ng/dl, IPSS ≥8, Benign DRE | 3 months | 58 vs 64 | TPV: 67.0 ±34.0 PSA: 16.2 ±16.8 |

37 | TPV: +3.7 ±34.8 (+5.5%) NS PSA: -0.2 ±22.4 (-2.0%) NS |

TPV: 68.3 ±33.5 PSA: 10.7 ±16.8 |

45 | TPV: -1.0 ±33.0 (-2.0%) NS PSA: -1.82 ±6.1 (-17.0% p < 0.05) |

Significant changes in Celecoxib group from baseline in PSA. 22 patients diagnosed with PCa. Non significant difference between group in TPV (p = 0.122), PSA (p = 0.545) |

| Karami 2016, [28] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Tadalafil 20 mg | Men ≥45 yo, IPS S≥12, LUTS due to BPH and ED, PVR <200 ml | 3 months | 59 vs 60 | PSA: 2.3 ±1.9 | 59 | PSA: 0.0 ±0.3 (0%) NS |

PSA: 2.5 ±1.8 | 60 | PSA: 0.0 ± 0.1 (0%) NS |

No significant changes from baseline or between groups in PSA |

| Hizli 2007, [29] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Serenoa repens 320 mg | Men 43–73yo, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥10, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, PVR ≤150 ml, Prostate volume ≥25 ml, PSA ≤4 ng/ml | 6 months | 20 vs 20 | TPV: 28.6 ±11.6 PSA: 2.1 ±0.9 |

20 | TPV: -1.0 ±2.2 (-3.5%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±0.2 (-5.0%) NS |

TPV: 35.2 ±10.3 PSA: 1.9 ±0.9 |

20 | TPV: -0.7 ±2.6 (-2.0%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±0.3 (-1.0%) NS |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume (p = 0.61) or PSA (p = 0.07). |

| Hizli 2007, [29] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Serenoa repens 320 mg |

Men 43–73 yo, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥10, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, PVR ≤150 ml, Prostate volume ≥25 ml, PSA ≤4 ng/ml | 6 months | 20 vs 20 | TPV: 28.6 ±11.6 PSA: 2.1 ±0.9 |

20 | TPV: -1.0 ±2.2 (-3.5%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±0.2 (-5.0%) NS |

TPV: 31.2 ±4.2 PSA: 1.7 ±0.7 |

20 | TPV: -0.8± 2.0 (-2.5%) NS PSA: -0.2 ±0.3 (-1.0%) N |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume (p = 0.55) or PSA (p = 0.07) |

| Lepor 1996, [18] Prostate Hyperplasia Study Group |

Terazosin vs Finasteride 5 mg | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥ 8, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, PVR <300 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 305 vs 310 | TPV: 37.5 ± 1.1 PSA: 2.2 ±1.9 |

277 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (-13.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.4 ±NR (-18.2%) (p <0.01) |

TPV: 36.2 ±1.0 PSA: 2.2 ±1.8 |

264 | TPV: -6.1 ± NR (-16.8%) PSA: +0.9 ±NR (+40.1%) (p <0.01) |

Statistical significant difference between groups in TPV and PSA. Significant difference from baseline in finasteride group |

| Lepor 1996, [18] Prostate Hyperplasia Study Group Low Risk |

Terazosin vs Finasteride 5 mg plus Terazosin | Treatment naïve men, AUASI score ≥8, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, PVR <300 ml, Clinical BPH, no other obvious cause of LUTS | 12 months | 305 vs 309 | TPV: 37.5 ± 1.1 PSA: 2.2 ±1.9 |

277 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (-13.4%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.4 ±NR (-18.2%) (p <0.01) |

TPV: 38.4 ±1.3 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

264 | TPV: +0.5 ±NR (+2.3%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±NR (-4.0%) NS |

Statistical significant difference between groups in TPV and PSA. Significant difference from baseline in finasteride group |

| Odusanya 2017, [30] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg versus Finasteride 5 mg | Men with LUTS due to BPH and enlarged prostate on DRE | 6 months | 30 vs 30 | TPV: 66.2 ±NR | 21 | TPV: +6.32 ±NR (+9.5%) (p = 0.17) | TPV: 66.57 ±NR | 20 | TPV: -6.8 ±NR (-10.2%), (p = 0.49) |

Non-significant change from baseline, no significant difference between groups |

| Odusanya 2017, [30] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg versus Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Finasteride 5 mg | Men with LUTS due to BPH and enlarged prostate on DRE | 6 months | 30 vs 30 | TPV: 66.2 ±n/a | 21 | TPV: +6.32 ±n/a (+9.5%) (p = 0.17) |

TPV: 55.43 n/a | 24 | TPV: -8.19 n/a (-11.8%), (p = 0.13) |

Non significant change from baseline. Significant difference between groups (p = 0.006) |

| Morgia 2014, [31] PROCOMB Trial Low Risk |

Tamsulosin vs Phytotherapy | Men 55–80 yo, benign DRE, PSA ≤4 ng/ml, IPSS ≥12, prostate volume ≤60 ml, PVR <150 ml | 12 months | 79 vs 71 | TPV: 45.0 ±n/a PSA: 2.1 ±n/a |

78 | TPV: -1.0 ±NR (-2.2%) NS PSA: -0.09 ±NR (-4.3%) NS |

TPV: 43.0 ±NR PSA: 1.94 ±NR |

67 | TPV: -1.5 ±NR (-3.5%) NS PSA: -0.0 ±NR (0%) NS |

No significant changes between groups in TPV and PSA. No significant changes form baseline |

| Morgia 2014, [31] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin vs Tamsulosin plus Phytotherapy | Men 55–80 yo, benign DRE, PSA ≤4 ng/ml, IPSS≥12, prostate volume ≤60 ml, PVR <150 ml | 12 months | 79 vs 75 | TPV: 45.0 ±n/a PSA: 2.1 ±n/a |

78 | TPV: -1.0 ±NR (-2.2%) NS PSA: -0.09 ±NR (-4.3%) NS |

TPV: 45.0 ±NR PSA: 2.11 ±NR |

74 | TPV: -2.5 ±NR (-5.5%) NS PSA: -0.16 ±NR (7.6%) NS |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume and PSA. No significant changes form baseline |

| McConnell 2003, [19] MTOPS Low Risk |

Doxazosin vs Finasteride 5 mg | Treatment naïve men 50 yo and older, AUASI 8–35, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, No other cause of LUTS | 4.5 years | 756 vs 768 | TPV: 36.9 ±21.6 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

N = TPV 582 N = PSA 655 |

TPV: +29.0 ±36 (+24.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: NR (+13%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 36.9 ±20.6 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

N=TPV 519 N=PSA 631 |

TPV: -12.0 ±30.0 (-19.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: n/a (-50%) p <0.001 |

4 years results. Significant differences between groups |

| McConnell 2003, [19] MTOPS Low Risk |

Doxazosin vs Doxazosin plus Finasteride 5 mg | Treatment naïve men 50 yo and older, AUASI 8–35, Qmax 4–15 ml/s, No other cause of LUTS | 4.5 years | 756 vs 786 | TPV: 36.9 ±21.6 PSA: 2.4 ±2.1 |

N = TPV 582 N = PSA 655 |

TPV: +29.0 ±36 (+24.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: NR (+13%) (p <0.05) |

TPV: 36.5 ±19.2 PSA: 2.3 ±1.9 |

N=TPV 574 N=PSA 673 |

TPV: -12.0 ±30.0 (-19.0%) (p <0.05) PSA: NR (-50%) p <0.001 |

4 years results. Significant differences between groupn and from baseline |

| Kuo 1998, [51] High Risk |

Dibenyline vs Finasteride | NP | 6 months | 71 vs 54 | TPV: 27.5 ±16.9 | 53 | TPV: -0.1 ±23.1 (-3.6%) |

TPV: 30.9 ±12.9 | 47 | TPV: -7.5 ± 11.5 (-24.3%), (p <0.05) |

Significant changes in finasteride group |

| Roehrborn 2010, [32] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin vs Dutasteride | Men ≥50 yo, with LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥12, prostate volume ≥30 ml, PSA 1.5–10 ng/dl, Qmax 5–15 ml/s | 4 years | 1611 vs 1623 | TPV: 55.8 ±24.2 TZV: 30.5 ±24.5 |

989 | TPV: +2.57 ±NR (+4.6%) TZV: +5.55 ±NR (+18.2%) |

TPV: 54.6 ±23.0 TZV: 30.3 ±21.0 |

1093 | TPV: -15.29 ±NR (-28%) TZV: -8.03 ±R (-26.5%) |

Significant change from baseline in dutasteride group. Significant difference between groups in TPV (p <0.001) and TZV (p <0.001) |

| Roehrborn 2010, [32] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin vs Tamsulosin plus Dutasteride | Men ≥50 yo, with LUTS due to BPH, IPSS ≥12, prostate volume ≥30 ml, PSA 1.5–10 ng/dl, Qmax 5–15 ml/s | 4 years | 1611 vs 1610 | TPV: 55.8 ±24.2 TZV: 30.5 ±24.5 |

989 | TPV: +2.57 ±NR (+4.6%) TZV: +5.55 ±NR (+18.2%) |

TPV: 54.7 ±23.5 TZV: 27.7 ±20.2 |

1113 | TPV: -14.93 ±NR (-27.3%) TZV: -4.96 ±NR (-17.9%) |

Significant difference between groups in TPV (p <0.001) and TZV (p <0.001) |

| Yokoyama 2012, [20] Low Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.2 mg vs Tadalafil 5 mg | Asian men ≥45 yo, >6 months history of BPH-LUTS, Total IPSS ≥13, Qmax 4–12 ml/s, Prostate volume >20 ml, PSA <4 or else negative biopsy | 3 months | 152 vs 155 | PSA: 1.75 ±1.6 | 143 | PSA: -0.06 ±0.61 (-3.5%) NS |

PSA: 1.71 ±1.14 | 137 | PSA: +0.13 ±0.59 (8.0%) p = 0.083 NS | Non-significant changes from baseline Small tendency in tadalafil arm without significance. Non-significant changes between groups |

| Debruyne 1998, [33] Low Risk |

Alfuzosin SR vs Finasteride 5 mg | Men 50–75 yo, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS >7, Qmax 5–15 ml/s for VV >150 mls | 6 months | 358 vs 344 | TPV: 41.4 ±25.7 PSA: 3.0 ±2.5 |

318 | TPV: -0.2 ±14.3 (+1.0%) NS PSA: +0. 1 ±2.7 (+3.3%) NS |

TPV: 40.9 ±23.5 PSA: 3.4 ±2.5 |

305 | TPV: -4.3 ±15.0 (-10.5%) (p = 0.05) PSA: -1.7 ±1.9 (-50.0%) (p = 0.05) |

Significant changes in finasteride group from baseline and in between group comparison for TPV (p <0.001) and PSA (p <0.001) |

| Debruyne 1998, [33] Low Risk |

Alfuzosin SR vs Alfuzosin SR plus Finasteride 5 mg | Men 50-75 yo, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS >7, Qmax 5–15 ml/s for VV >150 mls | 6 months | 358 vs 349 | TPV: 41.4 ±25.7 PSA: 3.0 ±2.5 |

318 | TPV: -0.2 ±14.3 (+1.0%) NS PSA: +0.1 ±2.7 (+3.3%) NS |

TPV: 41.1 ±22.6 PSA: 3.1 ±2.7 |

295 | TPV: -4.9 ±12.4 (-11.9%) (p <0.01) PSA: -1.4±1.7 (-45.2%) (p <0.01) |

Significant changes in combination group from baseline and in between group comparison for TPV (p <0.001) and PSA (p <0.001) |

| Argirovic 2013, [62] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Serenoa repens 320 mg | Men with LUTS due to BPH, Prostate volume <50 ml, IPSS 7–18, QoL >3, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, PVR <150 ml, PSA 1.5–4 ng/ml | 6 months | 87 vs 97 | TPV: 38.6 ±11.6 PSA: 2.1 ±0.9 |

87 | TPV: -1.0 ±0.6 (-2.6%) PSA: -0.1 ±0. 2 (-4.8%) |

TPV: 35.2 ±10.3 PSA: 1.9 ±0.9 |

97 | TPV: -0.7± 0.1 (-2.0%) PSA: -0.3 ±1.4 (-15.0%) |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume or PSA |

| Argirovic 2013, [62] High Risk |

Tamsulosin 0.4 mg vs Tamsulosin 0.4 mg plus Serenoa repens 320 mg | Men with LUTS due to BPH, Prostate volume <50 ml, IPSS 7–18, QoL >3, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, PVR <150 ml, PSA 1.5–4 ng/ml | 6 months | 87 vs 81 | TPV: 38.6 ±11.6 PSA: 2.1 ±0.9 |

87 | TPV: -1.0 ±0.6 (-2.6%) NS PSA: -0.1 ±0. 2 (-4.8%) |

TPV: 31.2 ±4.2 PSA: 1.97 ±0.7 |

81 | TPV: -0.8 ±0.3 (-2.6%) NS PSA: -0.25 ±0.2 (-14.7%) (NS p = 0.25) |

No significant changes between groups in prostate volume or PSA |

| Braeckman 1997, [72] High Risk |

Serenoa repens 320 OD vs Serenoa repens 160 BD | Men <75 yo, LUTS due to BPH, BPE from DRE and TRUS, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, IPSS 12–24, PVR <100 ml, PSA <10 ng/dl | 12 months | 42 vs 42 | TPV: 46.4 ±44.1 | 33 | TPV: -6.7 ±40.5 (-14.5%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 37.6 ±17.6 | 34 | TPV: -3.63± 23.7 (-9.6%) (p <0.001) |

Significant difference from baseline in both groups, non-significant difference between groups |

| Chung 2011, [83] Moderate Risk |

Tolterodine plus a blocker plus 5ARI vs a blocker plus 5ARI |

Men <70 yo, IPSS >8, IPSS storage Subscore >5, QoL >3, TPV >20 ml, Qmax <15 ml/s, urodynamically confirmed BPH/BOO | 12 months | 50 vs 87 | TPV: 49.2 ±26.3 TZI: 0.46 ±0.13 PSA: 3.44 ±1.55 |

50 | TPV: -9.5 ±22.9 (-19.3%) (p <0.001) TZI: -0.02 ±0.12 (-4.5%) (p <0.039) PSA: -1.44 ±1.61 (-41.8%) (p <0.001) |

TPV: 53.3 ±22.1 TZI: 0.47 ±0.15 PSA: 3.9 ±2.06 |

87 | TPV: -9.1 ± 21.8 (-17.1%) (p <0.001) TZI: -0.04 ±0.13 (-12.8%) (p <0.001) PSA: -0.97 ±3.1 (-24..8%) (p <0.013) |

Significant difference from baseline in both groups, non significant difference between groups in TPV (p = 0.877), TZI (p = 0.671) and PSA (p = 0.434) |

| Kosilov 2019, [55] HighRisk |

Tadalafil 5 mg versus Tadalafil 5 mg plus Solifenacin 10 mg | ED, LUTS due to BPH, IPSS 8–19, TPV <45 ml, PSA <10 ng/dl | 12 weeks | 107 vs 107 | TPV: 37.4 ±4.8 | 107 | TPV: -2.2 ±4.1 (-5.9%) (NS) |

TPV: 42.4 ±6.4 | 107 | TPV: -1.4 ±5.6 (-3.3%) (NS) |

Non significant difference from baseline or between groups |

| Allott 2019, [73] post hoc analysis of REDUCE trial Moderate Risk |

Subgroup analysis statinsusers vs non statinusers |

Men 50–75 yo, PSA 2.5-10 ng/dl, and had TRUSg prostate biopsy 6 months before enrollment | 48 months | 692 vs 3414 | Dutasteride arm Statin users TPV: 45.3 ±18.2 Non-statin users TPV: 45.7 ±22.4 |

NR | Dutasteride arm Statin users TPV: -6.8 ±18.5 (NR%) (p <0.033) Non-statin users TPV: -5.6 ±23.2 (NR%) (p = NR) |

Placebo arm Statin users TPV: 45.2 ±18.8 Non-statin users TPV: 45.7 ±10.7 |

NR | Placebo arm Statin users TPV: +11.4 ±19.2 (-NR%) (p <0.32) Non-statin users TPV: +12.6 ±24.3 (-NR%) (p = NR) |

Statistical significant difference (p = 0.032) in dutasteride group in patients receiving statins over the non-statin users (4.5% smaller prostate). Similan differences between statin and non-statin users in placebo arm (3–3.3%) without statistical significance (p ≥0.18) |

| Mills 2007, [74] Low Risk |

Atorvastatin 80 mg vs Placebo | Men ≥50 yo, IPSS score ≥13, Vol prostate ≥30 ml, Qmax 5–15 ml/s, LDL100–190 mg/dl | 26 weeks | 176 vs 174 | TPV: 48.7 ±19.0 TZV: 21.4 ±15.3 PSA: 2.73 ±2.2 |

160 | TPV: -2.0 ±0.83 (-4.1%) TZV: -0.3 ±0.64 (-12.5%) PSA: -0.1 ±0.08 (-3.6%) |

TPV: 50.7 ±19.0 TZV: 22.4 ±13.6 PSA: 2.81 ±2.3 |

159 | TPV: -2.4 ±0.85 (-4.7%) TZV: -0.3 ±0.66 (-13.4%) PSA: 0 ±0.08 (0%) |