Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the role of axillary ultrasonography (axUS) and ultrasound-guided pre-operative wire localisation of pre-treatment positive clipped node (CN) for prediction of nodal response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in node positive breast carcinoma patients.

Methods and materials:

A prospective study was conducted between June 2018 and August 2020 after Ethics Committee approval. Breast carcinoma patients (cT1-cT4b) with palpable axillary nodes (cN1-cN3) and suitable for NACT were recruited after written informed consent. Single, most suspicious node was biopsied and clipped. Nodal response to NACT was assessed on axUS. Wire localisation of CN was performed prior to axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Diagnostic performances of axUS and CN excision were assessed.

Results:

Of the 69 patients evaluated, 32 patients (mean age, 43.5 ± 11.8 years; females, 31/32 [97%]; pre-menopausal, 18/32 [56.3%]) with metastatic nodes who received NACT were included. Nodal pathological complete response rate was 34.4% (11/32) overall and 70% (7/10) in patients with ≤2 suspicious nodes on pre-NACT axUS. False-negative rates (FNRs) of axUS and CN excision were 4.8% and 28.6% respectively. Combination of post-NACT axUS and CN excision had an FNR of 4.8% overall and 0% in patients with ≤2 suspicious nodes on pre-NACT axUS.

Conclusion:

Combination of AxUS and ultrasound-guided wire localisation of pre-treatment positive CN has high diagnostic accuracy for nodal restaging after NACT in node positive breast cancer patients.

Advances in knowledge:

Addition of axUS assessment to wire localisation of CN reduces its FNR for detecting residual metastasis after NACT.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) is widely used prior to surgery in clinically node positive breast cancer patients. It downstages the tumour and facilitates breast conservation surgery, thereby improving survival.1,2 Axillary nodal staging has become an integral part of breast cancer management and thus, unravelling the techniques for accurate staging is the current focus of research in these patients.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) had been the standard of care for all patients before the introduction of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).3 However, ALND is associated with significant morbidity and complications like lymphoedema and shoulder stiffness.4 Thus, SLNB came into clinical practice and it was found useful for axillary staging in clinically node negative patients.2,5 However, SLNB lacks accuracy in evaluating patients after NACT because of its high false-negative rate (FNR) of 10.1–14.2%.6–8 Chemotherapy induced changes in lymph nodes often impair diffusion of the injected dye resulting in relatively high FNR of SLNB.9–11 Due to apprehensions of high FNR of SLNB, ALND is still widely performed in many centres in developing countries like ours.12 However, a large proportion of patients (31.2–42.4%) develop nodal pathological complete response (pCR) after NACT.6,13,14 Thus, there arises a definite need for accurate nodal restaging techniques following NACT in node positive breast cancer patients.

With the aim of achieving targeted axillary dissection, various minimally invasive techniques of marking pre-treatment positive lymph nodes have come into use.8,9,15–19 Among them, metallic clip placement followed by pre-operative wire localisation is a commonly used and cost-effective technique. However, there is conflicting evidence of its success rate.8,17–19

Axillary ultrasonography (AxUS) is widely used for nodal staging in breast cancer patients.20–22 Additionally, it has the twin advantage of guiding core needle biopsy and subsequent marking of positive lymph nodes, facilitating targeted nodal excision after NACT.8,23 Limited evidence is available on the use of axUS for nodal restaging after NACT.24–28

This study was planned to evaluate the role of post-NACT axUS and ultrasound-guided pre-operative wire localisation of pre-treatment positive clipped node (CN) for assessment of nodal response to NACT in node positive breast carcinoma patients, taking ALND as the gold-standard.

Methods and materials

This prospective diagnostic accuracy study was approved by the Institute’s Ethics Committee and performed between June 2018 and August 2020 after obtaining written informed consent from all patients. The STARD reporting guideline was followed in this study. Being a feasibility study, a convenience sample of 32 patients was studied.

Study population

Consecutive breast cancer patients (cT1-cT4b) with clinically palpable nodes (cN1-cN3) suitable for NACT were included. Patients with distant metastasis were excluded from the study. Data pertaining to clinical and demographic profile of the patients along with the primary tumour subtypes were collected. Clinical staging was done according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system.29

Imaging technique

AxUS and all ultrasound-guided interventions were performed on Aixplorer ultrasound system (SuperSonic Imagine, Aix-en-Provence, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France) using a 4–15 MHz linear array transducer by any one of the three investigators, each of them having at least 12 years’ experience in diagnostic and interventional radiology. Patient lying supine with ipsilateral arm positioned above the head, nodes at levels I, II and III, that are located lateral, posterior and medial to the pectoralis minor muscle respectively, were evaluated. Further, internal mammary and supraclavicular nodes were also evaluated. The lymph node features considered suspicious for metastasis were—diffuse or focal cortical thickening >3 mm, effacement of fatty hilum, non-hilar blood flow and round shape.30 The number of suspicious nodes were counted in all patients. The cortical thickness of each suspicious nodes was measured in the longitudinal plane at the site of maximum thickness. Patients with no suspicious nodes on axUS were excluded.

Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy and clip placement

Under aseptic conditions and ultrasound guidance, the suspicious node with the maximum cortical thickness was biopsied in each patient using 18G Monopty core biopsy instrument (Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, Arizona, USA). In the same sitting, a metallic clip (UltraClip, Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, Arizona, USA) was placed in the centre of the hypoechoic cortex of the biopsied node to facilitate its identification on post-NACT axUS and on pathological examination after ALND. Subsequently, patients with nodal metastasis were included in the study.

NACT regimen

All patients received 6–8 cycles of various combinations of cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin, carboplatin, docetaxel and traztuzumab based on the receptor status of the mass at three weeks intervals. Interim axUS was performed after 3–4 cycles of NACT to document the morphological changes in the CN to facilitate its identification after NACT. However, the interim axUS was not used to assess the treatment response in these patients.

Post-NACT evaluation

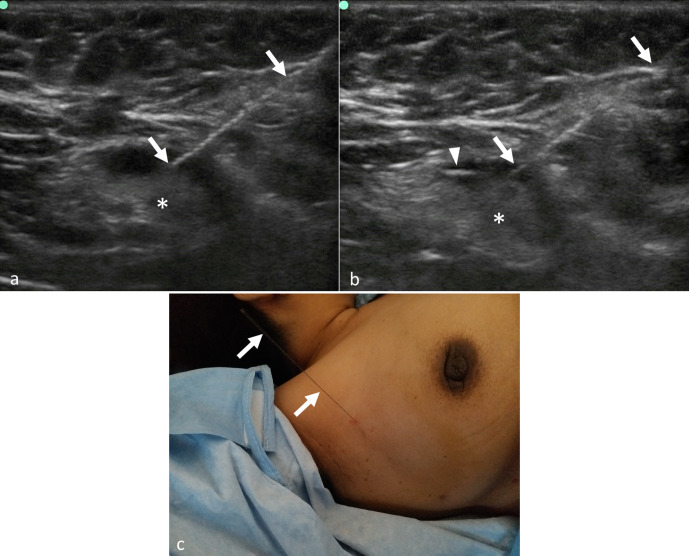

After completion of NACT, axUS of all axillary nodes, including the CN, was performed. On the day of ALND, under aseptic conditions, Dualok breast localisation wire (Bard Biopsy Systems, Tempe, Arizona, USA) was deployed percutaneously in the CN, irrespective of the nodal response to NACT, to facilitate its surgical excision (Figure 1). In patients in whom the wire could not be inserted, CN removal was aided by intraoperative ultrasound guidance. On ALND, all axillary nodes, including the wire localized node, were removed and sent for histopathological examination. The pathologists were blinded to post-NACT axUS findings.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound-guided pre-operative wire localisation of clipped lymph node after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (a, b) Ultrasonography images show placement of localisation wire (arrows in a & b) in the clipped node (asterisks in a & b) prior to surgery. The clip (arrowhead in b) is well visualized within the cortex of the node in image (b). (c) Post-procedure clinical photograph showing the localisation wire in the right axilla.

Reference standard

Prior to NACT, ultrasound-guided biopsy was used as the reference standard for identifying metastatic nodes. After NACT, pathological examination of ALND specimen was used as the reference standard for identifying residual metastasis.

Definitions

Nodal pCR was defined as absence of residual metastasis in all nodes on histological examination of the ALND specimen. Patients with ≤2 suspicious nodes on pre-NACT axUS were found to have a higher nodal pCR rate than the rest of the patients. Therefore, the patients were classified based on the number of suspicious nodes on pre-NACT axUS as low nodal burden group (≤2 nodes) and high nodal burden group (>2 nodes) for further subgroup analysis.

Nodal response on axUS was termed complete response (CR) when no suspicious features were seen in the CN as well as the non-clipped nodes. When the number of suspicious nodes remained the same or reduced as compared to the pre-treatment number, it was termed residual disease on axUS.

Similarly, no suspicious nodes on axUS along with no metastasis on pathological examination of CN was defined as CR for combination of axUS and clipped nodes excision biopsy. Patients with suspicious nodes on axUS or CN metastasis were classified as having residual disease.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata, v. 14.2 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA). Quantitative variables were described as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the qualitative variables. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and positive and negative likelihood ratios of axUS for predicting residual metastasis were estimated by plotting response on axUS in a two-by-two contingency table using pathological response on histopathological examination of the ALND specimen as the gold-standard. FNRs of CN excision and axUS for detection of residual metastasis were compared. All statistical tests were two-sided and statistical significance was taken as p value < 0.05.

Results

Study population and baseline evaluation

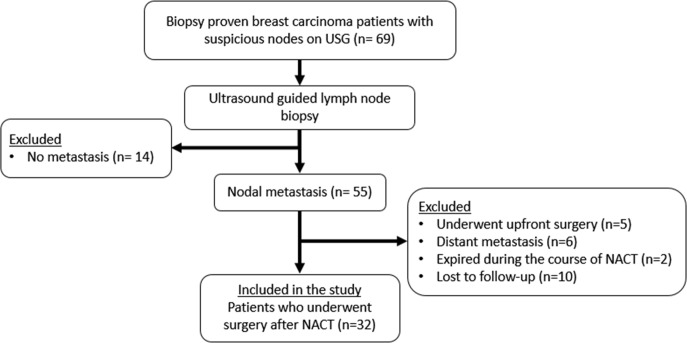

Sixty nine breast carcinoma patients with clinically palpable nodes were evaluated by axUS. Core needle biopsy followed by metallic clip placement was done on one node per patient in all. In one patient, a second clip had to be placed due to non-visualisation of the initially placed clip within the cortex. No other complications were experienced.

Nodal metastasis was confirmed on biopsy in 55 patients, among whom 32 patients eligible for NACT and subsequent ALND were included in the study (Figure 2). Their mean age was 43.5 ± 11.8 years, 31/32 (97%) were females and 18/32 (56.3%) were pre-menopausal. The most common histological subtype was invasive carcinoma, no special type (29/32, 90.6%) while the most common molecular subtype was Her2neu positive type (13/32, 40.6%). The clinical, demographic profile and axUS findings are depicted in Table 1. These 32 patients had a total of 207 suspicious axillary nodes. Ten patients (31.3%) had ≤2 while 22 (68.8%) had >2 suspicious nodes.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the recruitment process. NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Profile of the study population (n = 32)

| Variable | Number of patients (%)/Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (Mean ± SD, years) | 43.5 ± 11.8 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 31 (96.9%) |

| Male | 1 (3.1%) |

| Menstrual status | |

| Pre-menopausal | 18 (56.3%) |

| Post-menopausal | 13 (40.6%) |

| Not applicable (male) | 1 (3.1%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Breast lump | 32 (100%) |

| Mastalgia | 6 (18.8%) |

| Nipple retraction | 3 (9.4%) |

| Nipple discharge | 1 (3.1%) |

| Duration of symptoms (Mean ± SD, months) | 6.5 ± 11.1 |

| Family history of breast cancer | 1 (3.1%) |

| Location of breast lump (quadrant) | |

| Upper outer | 18 (56.3%) |

| Upper inner | 3 (9.4%) |

| Lower outer | 5 (15.6%) |

| Lower inner | 4 (12.5%) |

| Central | 2 (6.3%) |

| T stagea | |

| cT2 | 11 (34.4%) |

| cT3 | 10 (31.3%) |

| cT4b | 11 (34.4%) |

| N stagea | |

| cN1 | 20 (62.5%) |

| cN2 | 11 (34.4%) |

| cN3 | 1 (3.1%) |

| Histological subtypea | |

| Invasive carcinoma, no special type | 29 (90.6%) |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 2 (6.3%) |

| Inflammatory carcinoma | 1 (1.3%) |

| Molecular subtypea | |

| Luminal | 9 (28.1%) |

| Her2neu positive | 13 (40.6%) |

| Triple negative | 10 (31.3%) |

| Suspicious nodes on axillary ultrasonography | |

| Level I/II/III | 32 (100%) / 12 (37.5%) / 5 (15.6%) |

| Internal mammary/Supraclavicular | 1 (3.1%) / 5 (15.6%) |

SD, standard deviation

based on American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, eighth edition (29)

Evaluation after NACT:

Clinical assessment: the clinical stage was reassessed after NACT, the distribution of which was- ycT0, 10/32 (31.3%); ycT1, 6/32 (18.8%); ycT2, 7/32 (21.9%); ycT3, 2/32 (6.3%); ycT4b, 7/32 (21.9%). 17 patients (53.1%) had no palpable nodes (ycN0), while 12/32 (37.5%) had ycN1 and 3/32 (9.4%) had ycN2 stage.

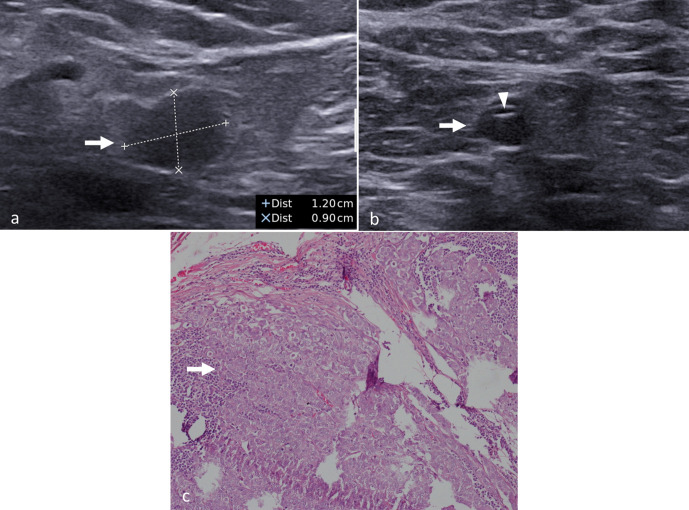

Assessment with AxUS: AxUS was repeated at a mean interval of 24.4 ± 30.1 days after the completion of NACT. In these 32 patients, the total number of nodes reduced from 207 to 69 with NACT. Nine (28.1%) patients developed nodal CR while 23 (71.9%) had residual disease on axUS (Figures 3 and 4).

Ultrasound-guided wire localisation of the clipped node: wire localisation of the CN was attempted in 27 patients on day of surgery while five patients directly underwent ALND. The procedure could be successfully performed in 26/27 patients (technical success rate, 96.3%), while it failed in 1 patient as the CN could not be visualised on axUS on the day of ALND. In this patient, the CN was visible, with clip within its echogenic fatty hilum, on the post-NACT axUS performed two weeks earlier and it had a normal morphology with short axis dimension of 2 mm. In another case, the wire got dislodged, after successful placement within the CN, while positioning the patient in the operating room. No other procedure-related complications were encountered. The CNs were identified using intraoperative ultrasonography in three patients, including the two in whom wire localisation failed or the wire got dislodged. Removal of the CN was confirmed on gross dissection of the ALND specimen in all patients, including the four in whom wire localisation or intraoperative ultrasonography was not performed.

Figure 3.

Complete pathologic nodal response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (a) Baseline ultrasonography image of a 61-year-old lady with cT3N1 breast cancer showing the metastatic axillary node (arrow) with diffuse cortical thickening and abnormal round shape. (b) The same node (arrow), after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, shows normal morphology with metallic clip within (arrowhead) suggesting complete response. No other suspicious nodes were seen on ultrasonography. (c) Photomicrograph of the lymph node (haematoxylin and eosin stain) shows absence of metastatic tumour cells in the excised lymph node.

Figure 4.

Partial nodal response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. (a) Baseline ultrasonography image of a 45-year-old lady with T3N1 breast cancer showing metastatic axillary node (arrow) with cortical thickening, loss of fatty hilum and round shape. (b) After completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the same findings are persisting in the same node (arrow) suggesting residual metastasis. The clip (arrowhead) is also seen within. (c) Photomicrograph (haematoxylin and eosin stain) of the lymph node shows residual metastatic cells within (arrow) confirming the findings of ultrasonography.

Axillary lymph node dissection

All patients underwent ALND at a mean interval of 25.5 ± 23.9 days after the post-NACT axUS assessment. On histological examination of the ALND specimen, residual disease was present in 21/32 (65.6%) patients, while 11/32 (34.4%) patients achieved nodal pCR. Nodal pCR rate was higher in patients with low nodal burden compared to those with high nodal burden (7/10, 70% vs 4/22, 18.2%; p = 0.01). There was no significant difference in the nodal pCR rate among different molecular subtypes—luminal, 2/9 (22.2%); Her2neu positive, 5/13 (38.5%); triple negative, 4/10 (40%) (p = 0.72).

Diagnostic performance of AxUS and CN excision biopsy

i) Assessment with axUS: AxUS accurately predicted the nodal status in 28/32 (87.5%) patients. Diagnostic performance of axUS was ascertained from a two-by-two contingency table (Table 2). The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and positive and negative likelihood ratios of axUS for detecting residual metastasis were 95.2% (95% CI, 76.2–99.9%), 72.7% (95% CI, 39–94%), 87% (95% CI, 71.7–94.6%), 88.9% (95% CI, 53.3–98.3%), 3.5 (95% CI, 1.3–9.2) and 0.1 (95% CI, 0.01–0.5) respectively.

Table 2.

Correlation of clipped node evaluation and axillary ultrasonography with histological examination of ALND specimen

| AxUS nodal response | ALND specimen | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastasis present | No metastasis | |||

| Clipped node | Non-clipped nodes only | |||

| In all patients (n = 32) | ||||

| Residual disease (n = 23) | 15 (65.2%) | 5 (21.7%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Clipped node | Non-clipped nodes only | |||

| 17 (73.9%) | 6 (26.1%) | |||

| Complete response (n = 9) | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (88.9%) | |

| In patients with low nodal burden on pre-NACT axUS (n = 10) | ||||

| Residual disease (n = 4) | 1 (25%) | 2 (50%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Clipped node | Non-clipped nodes only | |||

| 2 (50%) | 2 (50%) | |||

| Complete response (n = 6) | 0 | 0 | 6 (100%) | |

ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; AxUS, axillary ultrasonography; NACT, neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

One false-negative result was seen among the 21 patients with residual disease on histological examination, in which case there was CR on axUS and no metastasis in the CN but micrometastasis in one of the non-clipped nodes on histological examination. This resulted in an FNR of 4.8% for axUS. Among the 11 patients with nodal pCR, three false-positive cases were encountered, in which there was residual disease on axUS but reactive hyperplasia with no metastasis on histological examination.

Amongst the 10 patients with low nodal burden, post-NACT axUS correctly diagnosed all six patients who showed pCR, resulting in an FNR of 0% (Table 2).

ii) CN excision biopsy: Table 2 shows the results of CN excision biopsy after ultrasound-guided localisation. Among the 21 patients with residual nodal metastasis after ALND, no metastasis was present in the CN in six patients, yielding an FNR of 28.6% for CN excision biopsy.

iii) Combination of axUS and CN excision biopsy: among the 21 patients with residual metastasis, only one patient had CR on post-NACT axUS with no metastasis in the CN, yielding an FNR of 4.8% for the combination of post-NACT axUS and CN excision biopsy. Because there was only one false-negative result, the factors affecting the FNR could not be evaluated. No false-negative result was seen for the combination of axUS and CN excision biopsy (FNR, 0%) in the 10 patients with low nodal burden (Table 2).

Discussion

In this pilot study performed for the first time at our centre, we achieved a high success rate of 96.3% for wire localisation of the CN in breast cancer patients after NACT. Performing axUS in between NACT cycles and monitoring serial changes in the nodes gave us better confidence for visualising the CN on the day of ALND, although a formal analysis using objective criteria was not performed in this regard. The procedure failed in one patient due to non-visualisation of the CN on the day of ALND. This could happen when the node shrinks in size or shows similar echogenicity as the adjoining fat after NACT.28 Success rates of 70.8–93% have been reported for various techniques of marking axillary nodes.16,18,19 Apart from wire dislodgement in one patient, we faced no other complications.

Nodal pCR after NACT was seen in 11/32 (34.4%) patients in our study and this subset of patients could have been offered a less invasive surgery. It was noteworthy that the low nodal burden group showed a higher pCR rate of 70% (7/10 patients). However, due to the small number of patients, a meaningful conclusion could not be drawn in this regard.

AxUS after NACT is not a common practice so far and the limited number of studies available on it show a wide variation in its diagnostic accuracy due to factors like retrospective study design, variable timing of axUS response assessment and variable study populations.24–27 In our study, post-NACT axUS had high sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of 95.2%, 72.7%, 87% and 88.9% respectively for detecting residual nodal metastasis. False-negative result for axUS was noted in one patient in whom micro-metastasis was seen in a non-clipped node on histological examination, which was missed on axUS. Additionally, three patients had discordant results where the nodes showed persistent suspicious features, suggesting residual metastasis on axUS, while histological examination revealed reactive hyperplasia. The ultrasound features of reactive hyperplasia can overlap with that of metastasis.30 Therefore, it is prudent to include pathological examination of CN in addition to axUS to avoid a misdiagnosis. In low nodal burden patients who are potential candidates for conservation of axilla due to their high pCR rate, axUS fared better with an FNR of 0%. However, further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate these findings.

Studies on targeted CN excision biopsy demonstrate a low FNR of 0–8.3%.17–19 We encountered a high FNR of 28.6% for CN excision biopsy. We attribute this to the differences in the study populations. All our patients had proven metastatic nodes and among them, many patients had a locally advanced disease- 37.5% had cN2 or cN3 disease at baseline. In contrast, prior studies included mostly patients with low nodal burden (cN1 disease) or node negative disease at baseline.17–19 Therefore, it would not be appropriate to have a direct comparison of the results with that of previous studies.

On combining CN excision and post-NACT axUS, we noted a higher diagnostic accuracy. The overall FNR was 4.8% while it was 0% in low nodal burden patients. Majority of the prior studies had reported the results of CN excision biopsy only.8,17–19 The study by Kim et al was the only one which demonstrated the outcome of combined use of post-NACT axUS and CN. They tattooed the most suspicious node on axUS after NACT even when it was not concordant with the CN and reported an FNR of 20% for the combined technique as opposed to 33% for CN excision.16 In our study, although all nodes were evaluated on axUS after NACT, wire localisation was performed on the clipped node only, irrespective of its morphology and presence of other suspicious nodes on axUS.

The limitation of our study was its small sample size due to which the factors affecting the FNR of CN evaluation and axUS could not be assessed. Patients with low nodal burden at diagnosis were very few, and thus the findings in this subgroup needs further validation.

Conclusion

To conclude, the combination of post-NACT axUS and ultrasound-guided wire localisation of the clipped pre-treatment positive node has high diagnostic accuracy for nodal restaging after NACT in node positive breast cancer patients. Prospective studies with larger sample sizes are required to validate these results particularly in patients with low nodal burden. Also, further studies evaluating the nodal recurrence rates and survival rates in patients undergoing limited axillary dissection are essential to ascertain its long-term outcome.

Contributor Information

Vishnu Prasad Pulappadi, Email: vishnuprasad26@gmail.com.

Shashi Paul, Email: shashi.aiims@gmail.com.

Smriti Hari, Email: drsmritihari@gmail.com.

Ekta Dhamija, Email: drektadhamija.aiims@gmail.com.

Smita Manchanda, Email: smitamanchanda@gmail.com.

Kamal Kataria, Email: drkamalkataria@gmail.com.

Sandeep Mathur, Email: mathuraiims@gmail.com.

Kalaivani Mani, Email: manikalaivani@gmail.com.

Ajay Gogia, Email: ajaygogia@gmail.com.

SVS Deo, Email: svsdeo@yahoo.co.in.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hennessy BT, Hortobagyi GN, Rouzier R, Kuerer H, Sneige N, Buzdar AU, et al. Outcome after pathologic complete eradication of cytologically proven breast cancer axillary node metastases following primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 9304–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nice.org.uk. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and management NICE guideline [NG101]. Available from: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng101 [Accessed 18 July 2018]. [PubMed]

- 3.Moore MP, Kinne DW. Axillary lymphadenectomy: a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. J Surg Oncol 1997; 66: 2–6. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rebegea L, Firescu D, Dumitru M, Anghel R. The incidence and risk factors for occurrence of arm lymphedema after treatment of breast cancer. Chirurgia 2015; 110: 33–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyman GH, Somerfield MR, Bosserman LD, Perkins CL, Weaver DL, Giuliano AE. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of clinical oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 561–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, Taback B, et al. Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310: 1455–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, Fleige B, Hausschild M, Helms G, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 609–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70166-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caudle AS, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, Mittendorf EA, Black DM, Gilcrease MZ, et al. Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1072–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diego EJ, McAuliffe PF, Soran A, McGuire KP, Johnson RR, Bonaventura M, et al. Axillary staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: a pilot study combining sentinel lymph node biopsy with radioactive seed localization of pre-treatment positive axillary lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 1549–53. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-5052-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown AS, Hunt KK, Shen J, Huo L, Babiera GV, Ross MI, et al. Histologic changes associated with false-negative sentinel lymph nodes after preoperative chemotherapy in patients with confirmed lymph node-positive breast cancer before treatment. Cancer 2010; 116: 2878–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maguire A, Brogi E. Sentinel lymph nodes for breast carcinoma: an update on current practice. Histopathology 2016; 68: 152–67. doi: 10.1111/his.12853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kataria K, Srivastava A, Qaiser D. What is a false negative sentinel node biopsy: definition, reasons and ways to minimize it? Indian J Surg 2016; 78: 396–401. doi: 10.1007/s12262-016-1531-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spring L, Greenup R, Niemierko A, Schapira L, Haddad S, Jimenez R, et al. Pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy and long-term outcomes among young women with breast cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2017; 15: 1216–23. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebollo-Aguirre AC, Gallego-Peinado M, Sánchez-Sánchez R, Pastor-Pons E, García-García J, Chamorro-Santos CE, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer and positive axillary nodes at initial diagnosis. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol 2013; 32: 240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.remnie.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siso C, de Torres J, Esgueva-Colmenarejo A, Espinosa-Bravo M, Rus N, Cordoba O, et al. Intraoperative Ultrasound-Guided Excision of Axillary Clip in Patients with Node-Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy (ILINA Trial): A New Tool to Guide the Excision of the Clipped Node After Neoadjuvant Treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 784–91. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6270-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim WH, Kim HJ, Kim SH, Jung JH, Park HY, Lee J, et al. Ultrasound-Guided dual-localization for axillary nodes before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy with clip and activated charcoal in breast cancer patients: a feasibility study. BMC Cancer 2019; 19: 859. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6095-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dashevsky BZ, Altman A, Abe H, Jaskowiak N, Bao J, Schacht DV, et al. Lymph node wire localization post-chemotherapy: towards improving the false negative sentinel lymph node biopsy rate in breast cancer patients. Clin Imaging 2018; 48: 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim EY, Byon WS, Lee KH, Yun J-S, Park YL, Park CH, et al. Feasibility of preoperative axillary lymph node marking with a clip in breast cancer patients before neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a preliminary study. World J Surg 2018; 42: 582–9. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann S, Reimer T, Gerber B, Stubert J, Stengel B, Stachs A. Wire localization of clip-marked axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients treated with primary systemic therapy. Eur J Surg Oncol 2018; 44: 1307–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahbar H, Partridge SC, Javid SH, Lehman CD. Imaging axillary lymph nodes in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2012; 41: 149–58. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You S, Kang DK, Jung YS, An Y-S, Jeon GS, Kim TH. Evaluation of lymph node status after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: comparison of diagnostic performance of ultrasound, MRI and ¹⁸F-FDG PET/CT. Br J Radiol 2015; 88: 20150143. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkins JJ, Appleton CM, Fisher CS, Gao F, Margenthaler JA. Which imaging modality is superior for prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple negative breast cancer? J Oncol 2013; 2013: 1–7. doi: 10.1155/2013/964863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boughey JC, Ballman KV, Le-Petross HT, McCall LM, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, et al. Identification and resection of clipped node decreases the false-negative rate of sentinel lymph node surgery in patients presenting with node-positive breast cancer (T0-T4, N1-N2) who receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy: results from ACOSOG Z1071 (alliance. Ann Surg 2016; 263: 802–7. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hieken TJ, Boughey JC, Jones KN, Shah SS, Glazebrook KN. Imaging response and residual metastatic axillary lymph node disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2013; 20: 3199–204. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3118-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao H-M, Yu Y, Ge J, Wang X, Cao X-C, B-B Y. Accuracy of axillary ultrasound after different neoadjuvant chemotherapy cycles in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2016; 8: 36696–706. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peppe A, Wilson R, Pope R, Downey K, Rusby J. The use of ultrasound in the clinical re-staging of the axilla after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). Breast 2017; 35: 104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le-Petross HT, McCall LM, Hunt KK, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, et al. Axillary ultrasound identifies residual nodal disease after chemotherapy: results from the American College of surgeons Oncology Group Z1071 trial (alliance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2018; 210: 669–76. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banys-Paluchowski M, Gruber IV, Hartkopf A, Paluchowski P, Krawczyk N, Marx M, et al. Axillary ultrasound for prediction of response to neoadjuvant therapy in the context of surgical strategies to axillary dissection in primary breast cancer: a systematic review of the current literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2020; 301: 341–53. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05428-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hortobagyi GN, Connolly JL, D’Orsi CJ, Edge SB, Mittendorf EA, Rugo HS. Breast. In: Amin M. B, Edge S, Greene F, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer; 2017. pp. 589–636. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijayaraghavan GR, Vedantham S, Kataoka M, DeBenedectis C, Quinlan RM. The relevance of ultrasound imaging of suspicious axillary lymph nodes and fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the Post-ACOSOG Z11 era in early breast cancer. Acad Radiol 2017; 24: 308–15. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]